Abstract

We characterize all additive biderivations on the incidence algebra of a locally finite poset P over a commutative ring with unity . By decomposing P into its connected chains, we prove that any additive biderivation splits uniquely into a sum of inner biderivations and extremal ones determined by chain components. In particular, when every maximal chain of P is infinite, all additive biderivations are inner.

MSC:

16W25; 17C50; 16S90; 16W10; 06A11

1. Introduction

The concept of incidence algebras of partially ordered sets was first introduced by Rota in the 1960s [1] as a tool for solving combinatorial problems. Incidence algebras are fascinating objects that have been the subject of extensive research since their inception. For instance, Pierre and John [2] describe the relationships between the algebraic properties of incidence algebras and the combinatorial features of the partially ordered sets. In [3], Spiegel and O’Donnell provide a detailed analysis of the maximal and prime ideals, derivations and isomorphisms, radicals, and additional ring-theoretic properties of incidence algebras. Further developments on the structure of incidence algebras can be found in [4,5,6,7].

The study of derivations in the context of algebras is a valuable and significant endeavor. Yang provides a detailed account of the structure of nonlinear derivations on incidence algebras in [8], specifically decomposing the nonlinear derivations into three more specific forms. Regarding the decomposition of derivations, two significant findings pertaining to their structure have been established. Notably, Baclawski demonstrated that every derivation of the incidence algebra , when is a field and P is a finite locally poset, can be expressed as the sum of an inner derivation and an additive induced derivation [9]. This result was extended by Spiegel and O’Donnell [3] to cases where is a commutative ring. Additional insights into the structure of other special derivations on incidence algebra can be found in [10,11,12,13].

Building upon the aforementioned studies of derivations on incidence algebras, it is natural to investigate biderivations in this context. Kaygorodov and Khrypchenko delineate the structure of antisymmetric biderivations of finitary incidence algebras , where P is an arbitrary poset and is a commutative ring with unity, in [14]. In [15], Benkovič proves that every biderivation of a triangular algebra is the sum of an inner biderivation and an external biderivation. Later, Ghosseiri demonstrates that every biderivation of upper triangular matrix rings is the sum of an inner biderivation, an external biderivation, and a distinct category of biderivations [16]. Ghosseiri also presents particular instances where every biderivation is inner.

In the literature, many biderivations on different algebras have been shown to decompose into the sum of inner and extremal ones. Motivated by this, we ask whether general biderivations on incidence algebras admit a similar decomposition. Compared with [14], which characterizes antisymmetric biderivations on finitary incidence algebras , our work extends the type of biderivations under consideration from antisymmetric to general ones, while the algebraic framework is more restrictive. Moreover, although most existing studies assume linearity, we find this condition unnecessarily strong. Therefore, in this paper, we focus on additive biderivations of incidence algebras and determine their precise structure. Specifically, let be a commutative ring with unity, and P a locally finite poset such that any maximal chain in P contains at least three elements. The additive biderivation b is the exact sum of several inner biderivations and extremal biderivations. Furthermore, we give that when the number of elements in any maximal chain in P is infinite, b is an inner biderivation.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Incidence Algebra

Throughout this paper, denotes a commutative ring with unity. Recall that a relation ≤ is said to be a partial order on a set S if it satisfies the following conditions:

- Reflexivity: for all ;

- Antisymmetry: if and , then ;

- Transitivity: if and , then .

A partially ordered set (or poset) is a set equipped with a partial order. A poset is locally finite if, for any in S, there are finitely many elements satisfying . Let be a locally finite poset. We use the notation to mean that and . Now, let us recall the definition of incidence algebra.

Definition 1.

The incidence algebra is defined as the set of functions

with multiplication given by

For each pair in P, let denote the element in defined by

For brevity, we will use the notation to denote , where and . Consequently, any element can be expressed as . It is evident that the multiplication in satisfies the following properties:

- If , then ;

- If , then .

This relation allows us to derive the following formula, which will be used extensively in this article. For any and , in P, we have

2.2. Additive Biderivations

A function is a derivation of if, for any , it satisfies

A function is said to be a biderivation of if it is a derivation when fixing any one of its arguments. This means that for every , b satisfies

Moreover, b is an additive biderivation if b also satisfies

The so-called inner biderivation is defined by

where is a fixed element, and denotes the Lie bracket of and . It is known that in prime and semiprime rings, all biderivations are inner (Brešar [17]). However, in certain algebras, such as triangular algebras and upper triangular matrix algebras, non-inner biderivations do occur. To describe the structure of these non-inner parts, Benkovič [15] introduced the notion of extremal biderivations and showed that every biderivation on triangular algebras can be expressed as the sum of an inner biderivation and an extremal one.

More precisely, a biderivation b is called an extremal biderivation if there exists such that

2.3. Decomposition of Posets

Our research reveals a close relationship between the structure of additive biderivations in and that of the poset P. Accordingly, we proceed to decompose P in this section, which will subsequently be employed in constructing the structure of the additive biderivations. In detail, we will consider and decompose the cases where P is connected or not.

First, let us introduce some notation. Consider a relation ∼ on P where indicates that x and y are comparable, i.e., either or . The relation ≁ indicates that x and y are not comparable. A totally ordered set is a poset in which every pair of elements is comparable.

Definition 2.

A chain in a poset P is a subset that is totally ordered with respect to ≤.

Example 1.

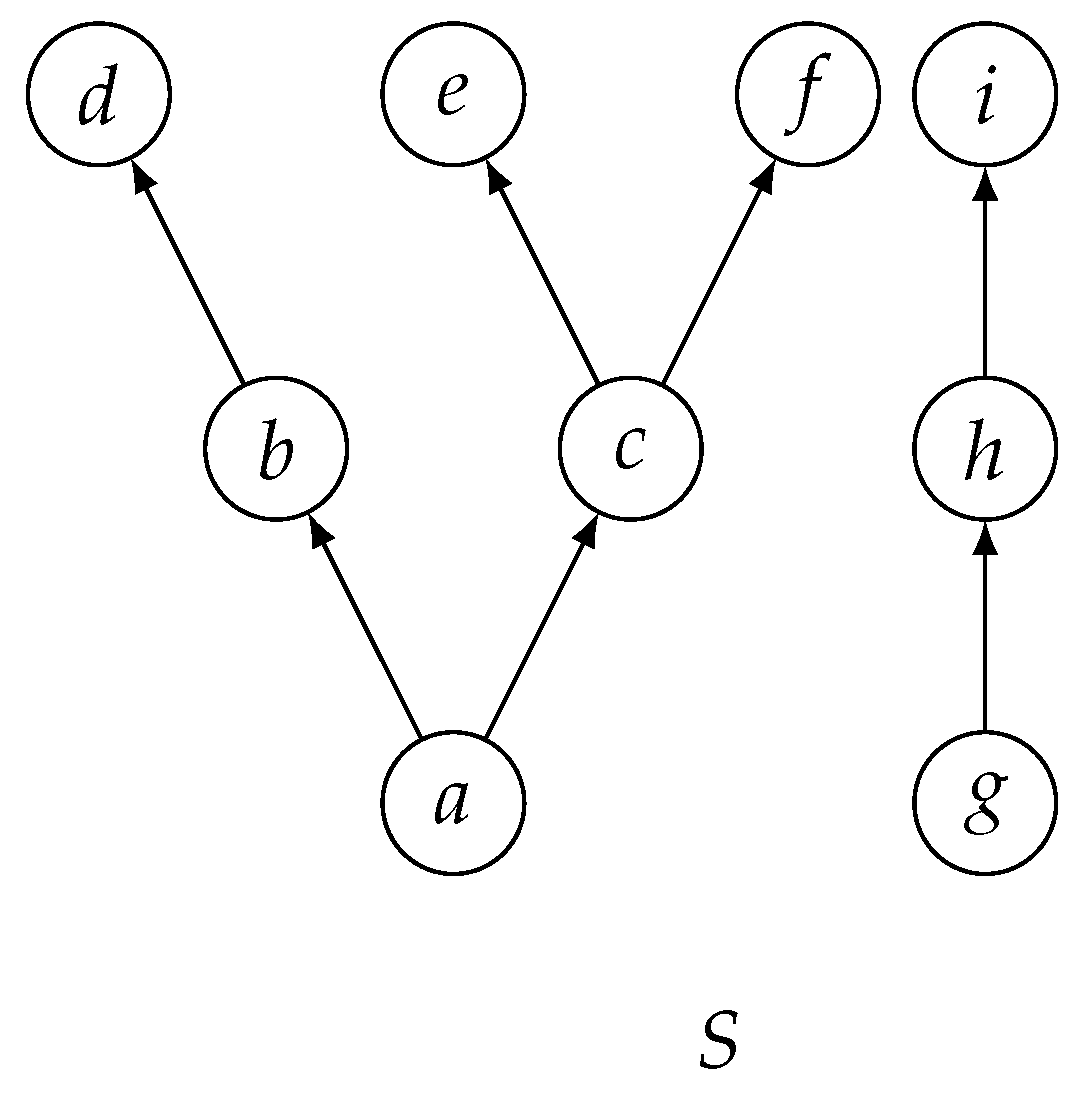

Consider the poset represented by the following Hasse diagram, where denotes for all . In this case, the pair of elements b and e is not comparable, and the subset of S constitutes a chain.

- 1.

- The first decomposition, when P is not connected.

First, let us introduce a relation between any two elements in .

Definition 3.

Two elements are defined as being connected if there exists a sequence such that , , …, , and . A poset P is connected if any pair of elements in it are connected.

It is evident that the relation of being connected is an equivalence relation on P. Thus, we can decompose P into the union of its connected components:

where is an index set and each is a connected poset.

Example 2.

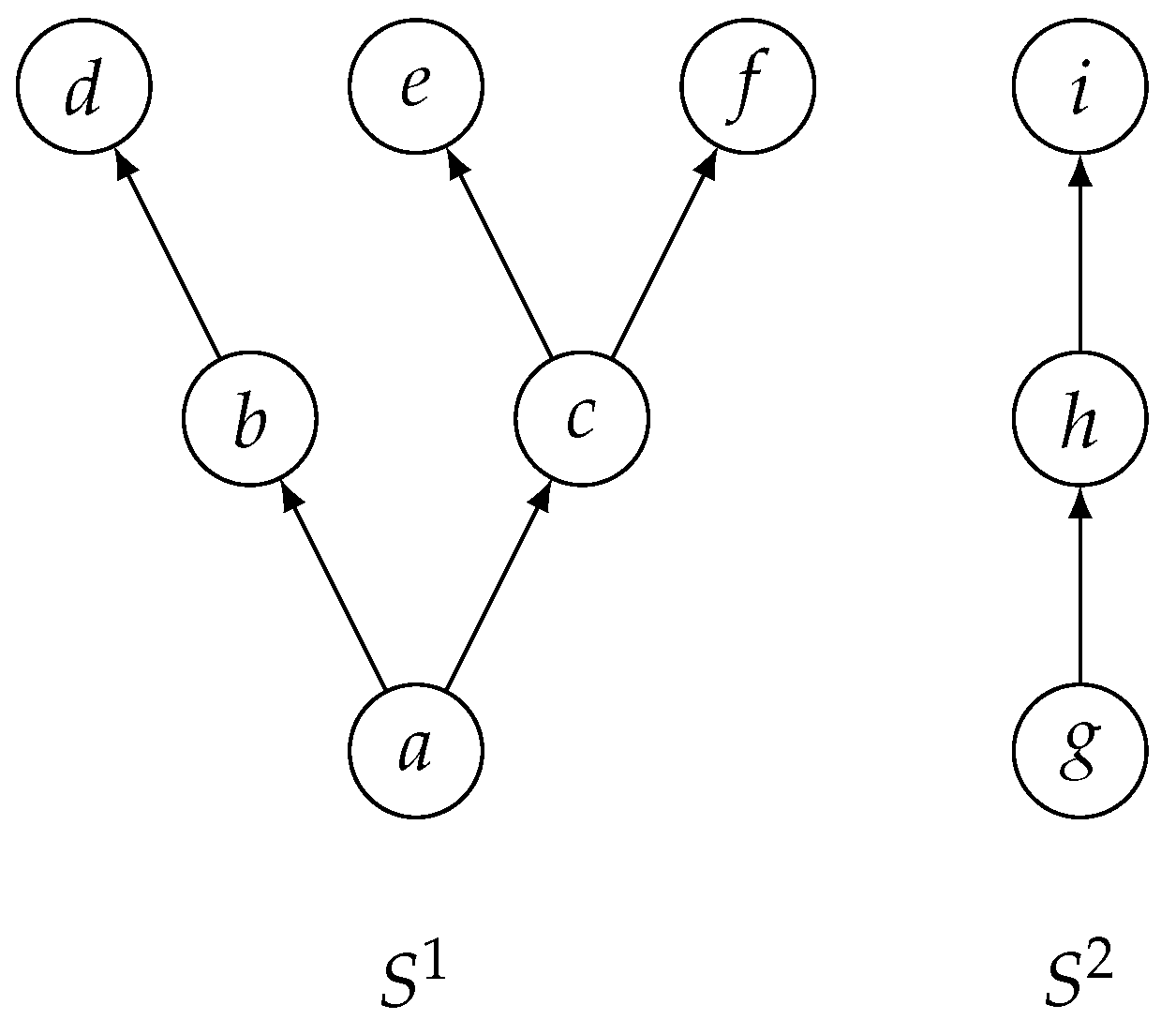

Consider the poset S defined in Example 1. It can be observed that S can be expressed as the union of two disjoint sets: and .

It is evident that for . Therefore, for any , we have

- 2.

- The second decomposition, when P is connected.

Next, we present a second decomposition of P when P is connected. We begin by defining a key term.

Definition 4.

A chain in P is called maximal if adding any element from P to it would result in it no longer being a chain.

In this context, the notation will be used to denote a maximal chain in P that contains .

We proceed to define a set of subsets of P:

Definition 5.

For any pair of elements , we define the relation if there exist elements in P such that . We say and are connected if there exist chains such that , , …, , .

With respect to the connectedness relation on L, we can decompose L into the union of its equivalence classes:

where is an index set corresponding to the decomposition of L.

For each , define a subset of P:

It is evident that . However, it is not necessarily the case that for all in .

Example 3.

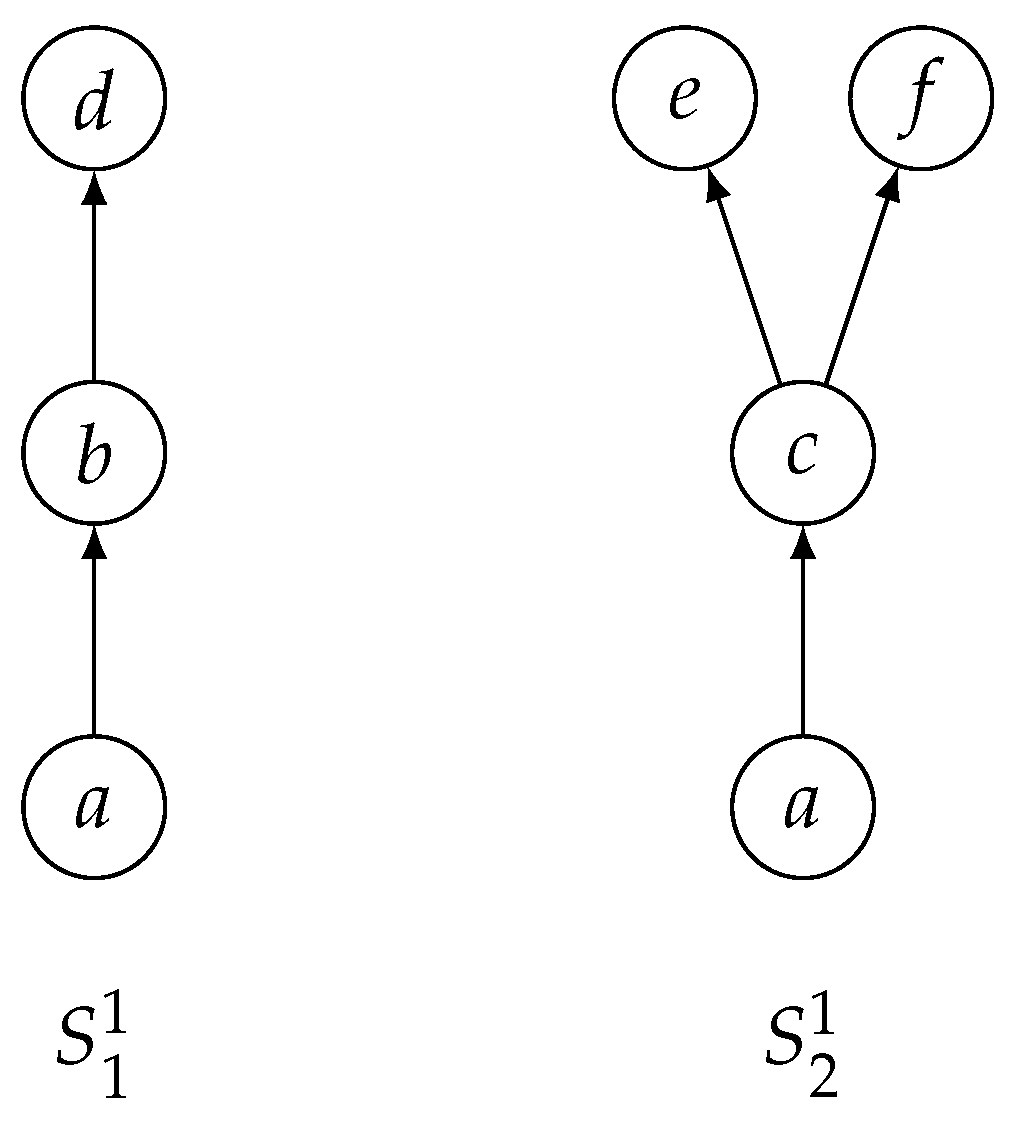

To illustrate this decomposition, consider from Example 2. The set can be expressed as the union of two sets: and .

An element is said to be maximal if there is no element such that , and minimal if there is no element such that .

Lemma 1.

Let in be defined in (10); then there does not exist a pair of elements in P such that . Additionally, any element in is either a minimal or a maximal element of P.

Proof.

We begin by asserting that any element in is isolated, meaning that no other element in can be compared with it. Suppose, for contradiction, that there exists a pair of elements contained in . Then, there exist chains and such that and . It follows that , implying and , which contradicts the assumption that . Therefore, any element in is isolated.

Now, suppose there exists an element that is neither maximal nor minimal. Then there exist elements in P. According to the definition of and and the assumption that any maximal chain of P has at least three elements, there exist elements and that can be compared with x, and there exist maximal chains and such that and . Without loss of generality, suppose . It is evident that , so . Similarly, . This implies that both and are elements of , which contradicts the previous conclusion. Thus, any element in must be either minimal or maximal. □

By the lemma above, for any , where P is connected, we can decompose it as

If and the product is non-zero, then there exist in and in such that . Therefore, we conclude that , implying that and , which contradicts Lemma 1. This leads to the following corollary.

Corollary 1.

For any in , let and , then .

3. Additive Derivations of

In the study of additive biderivations, it is necessary to discuss some properties of additive derivations of , since an additive biderivation becomes an additive derivation when one of its arguments is fixed. Let P be a locally finite poset, let be a commutative ring with unity, and let be the incidence algebra of P over . Suppose d is an additive derivation of .

We will denote to represent for any and . We begin by demonstrating a lemma that shows the structure of the value of .

Lemma 2.

Let and , then

Proof.

Consider a fixed pair and an arbitrary element . Suppose with and . We examine the expression by multiplying on the left by and on the right by :

Since , it follows that unless or . This establishes the desired equality (13). □

The proof of the aforementioned lemma allows us to derive the following corollary.

Corollary 2.

Let , , then unless the elements satisfy one of the following cases: (1) , ; (2) , .

In describing the structure of biderivations, we will try to prove that some of them are equivalent. To do this, we introduce a number of instrumental lemmas as described below.

Lemma 3.

Let and , then

- (1)

- For any , ;

- (2)

- For any , .

Proof.

We will demonstrate part (1), and the proof of part (2) follows analogously. Consider fixed elements and . For any , using Equation (4), we obtain

Therefore, we deduce that . Setting r to be the unity element of yields , thereby establishing part (1). □

Lemma 4.

Let , then .

Proof.

Let be fixed. Observe that

Since the above expression equals zero and is a non-zero element of the incidence algebra, it follows that . □

Lemma 5.

Let , then .

Proof.

Let be fixed. Then,

Since is a non-zero element of the incidence algebra, we deduce that . □

4. Additive Biderivations of

In this section, we will employ the properties of additive derivations derived in Section 3 to prove our main theorem (Theorem 4), which elucidates the structure of additive biderivations on the incidence algebra . Let P be a locally finite poset, and let be a commutative ring with unity. In this section, we will use the notation to denote the value for any and .

We begin by considering a corollary that can be readily extended from Lemma 2.

Corollary 3.

Let , , and , then

The preliminary stage will entail a reduction in the complexity of the structure of b. This will be achieved by establishing a sufficient condition that characterizes the circumstances under which b is equal to zero.

Lemma 6.

Let , ; if at least one pair among is not comparable, then for any .

Proof.

Consider , . Suppose at least one pair among is not comparable. This situation can be divided into four cases: (1) ; (2) ; (3) ; (4) .

- Case 1:

- Suppose . We consider two subcases: and .If , by Corollary 3, we haveAccording to Corollary 2, both and are zero because .If , we obtain thatIn (20), both and are zero by Corollary 2. For the remaining terms in (20), using Lemma 3 on the first argument of each term, we haveNoting that and (if , we obtain , which contradicts ), in (21) is zero by Corollary 2. Therefore, the lemma is proved when .

- Case 2:

- If , then and . From Corollary 3, we haveWe assert that either or , because if , then , which contradicts . For , it is zero by Lemma 2 if . If , by Lemma 2, we getTherefore, the lemma is proved when .

- Cases 3 and 4:

- If or , the proof is similar to Cases 1 and 2.

Thus, the lemma is proved. □

Remark 1.

Intuitively, the lemma asserts that an additive biderivation must vanish on any pair of basis elements that are incomparable. The multiplication rules of incidence basis elements (where for many incomparable configurations), together with the derivation property in each argument, force all such coefficients to be zero. Hence, nontrivial behavior can only occur along comparable pairs (chains), which is the crucial reduction used in the sequel.

According to the decomposition (8), we can suppose that for any ,

where . By applying the decomposition of P, as defined in (7), and the aforementioned lemma, it is straightforward to conclude that if , thereby yielding the following result:

Accordingly, this decomposition permits us to limit our analysis to the case where P is connected, as will be discussed subsequently. We will subsequently present the theorem, in the case where P is connected, which describes the conditions under which certain terms in Equation (18) are equal to zero. Prior to this, we will present an instrumental lemma.

Lemma 7.

Let , then

Proof.

Let be arbitrary. Since b is a biderivation, it satisfies the derivation property in each argument separately. We begin by applying the derivation property to the first argument of , followed by applying it to the second argument. This yields

Conversely, we first apply the derivation property to the second argument and then to the first argument, obtaining

The proof is completed. □

In accordance with the aforementioned lemma, it is possible to select specific values for in order to demonstrate that . For that are comparable with each other and have , the following two subcases can be identified: (1) ; (2) . The following two theorems will address these subcases in greater detail.

Theorem 1.

Let , then

Proof.

We prove the lemma by considering three cases based on the position of x in P: minimal, maximal, and neither.

- Case 1:

- x is a minimal element in P. By Corollary 3, we haveFor any pair where y is not a maximal element, let . By Lemma 7, we know thatThus, when x is a minimal element, reduces to the given form

- Case 2:

- x is a maximal element in P. The procedure is similar to Case 1.

- Case 3:

- x is neither a minimal nor maximal element. In this case, there exist such that . For any , we haveThis implies . Similarly, for any , we can deduce . Hence, when x is neither a minimal nor maximal element, we have .

Combining the three cases, the lemma is proven. □

Remark 2.

The theorem implies that the values of a biderivation on diagonal basis elements can be non-zero only at boundary points of the poset, that is, at minimal or maximal elements. Intuitively, this follows from inserting between other basis elements and applying the commutation identities, which eliminate contributions from interior points: whenever a third comparable element exists, the corresponding terms vanish. Thus, the diagonal component of a biderivation is necessarily supported at the endpoints of the poset, providing the foundation for the extremal components constructed later.

Theorem 2.

Let P be a connected poset such that any maximal chain has at least three elements. For any and that are comparable with each other and have . The additive biderivation b satisfies , except in the case where and one of x and u is the maximal element in P and the other is the minimal element.

Proof.

Let and satisfy the conditions of the theorem. We further divide this case into four subcases:

- Case 1:

- If and , except in the case where and one of x and u is the maximal element in P and the other is the minimal element, then by Corollary 3, we haveWe have by using Lemma 3 in its first argument when . If , it is also correct because by Corollary 3. By the same reasoning in its second argument, we obtain . Without loss of generality, we can assume that . It is evident that y is not minimal or u is not maximal; otherwise, the case is excluded. Thus, by Lemma 4 and Theorem 1, we haveSimilarly, is also equal to 0. Therefore, we have in this case.

- Case 2:

- If and . We consider two subcases: and .

- (a)

- If , we haveSince and , by Lemma 2 and Corollary 2. Therefore, .

- (b)

- If , the proof is similar.

- Case 3:

- If and .The proof is similar to subcase 2.

- Case 4:

- If and , implying . By Corollary 3, we haveFor any pair , the term is equal to by Lemma 3. Let us consider its second argument, whereby because and , it is equal to 0 by Corollary 2. In the same way, for any , we have . Thus,By the assumption on P, there exists an element such that z is comparable with x and y. We consider three cases:

- If , applying Lemma 7, we obtainThe left-hand side is zero, and the right-hand side equals , implying .

- If , the proof is similar to (a).

- If , applying Lemma 5, we haveConsider the second argument of and , respectively Because , we have by Corollary 2. This implies .

Considering all the above cases, the theorem is proved. □

Remark 3.

The theorem shows—after a case-by-case analysis—that most configurations of comparable indices force the corresponding biderivation entries to vanish; only special “endpoint–endpoint” configurations, where one index is minimal and the other maximal, may yield nontrivial terms. The underlying mechanism is the repeated application of the commutation identity (Lemma 7) together with the vanishing on incomparable pairs: whenever an auxiliary comparable element exists, the relevant coefficients are forced to zero. Consequently, the theorem confines all possible non-zero patterns to the finite boundary situations that generate the extremal biderivations.

The objective of the forthcoming project is to provide evidence that certain components of Equation (18) are equal. In particular, it will be demonstrated that when satisfy specified conditions. Prior to this, two lemmas will be proven.

Lemma 8.

Let , then

Proof.

For any , applying Lemma 3 to the left or right argument of separately, we have

Thus, we have . Using a similar process for , we obtain the other equality. □

Lemma 9.

Let , then

- (1)

- ;

- (2)

- .

Proof.

Let . For and , using Lemma 5 for its first argument, we obtain

noting that by Corollary 3. Additionally, we have by Lemma 4. Plugging the results from (43) into this, we find that

which implies . Then . Similarly, we can obtain the other equality. □

Corollary 4.

Let , then .

Proof.

Let . There exists that is comparable with x and y by the assumption that any maximal chain in P has at least three elements. We consider three cases.

If , according to Lemma 8, we have

From Lemma 9, we have

For the remaining two cases and , a similar process yields the same result. □

Theorem 3.

Let , in , where is the index set defined in (10), then

Proof.

Let , , . If is a totally ordered set, it is evident from Lemma 9 that . If is not a totally ordered set, according to the construction of , there exist chains defined in (10) such that , , and for any . Therefore, there exist . Because is a totally ordered set, using Lemma 9, we thus have

This proves (48). □

Remark 4.

The theorem shows that a certain family of coefficients (for instance, ) remains constant along any connected chain component. Intuitively, this follows from propagating local equalities along adjacent links of a chain using Lemmas 8 and 9, so that the local relations, through this chain-wise propagation, ultimately yield a global constancy on the entire component. Consequently, one can associate a single scalar with each chain component, and these scalars serve as the weights for the inner biderivation contributions.

For any , let , and define

A crucial conclusion is that for any pair in , where , the value , as demonstrated by the aforementioned theorem.

Now that the requisite preparations have been completed, we may proceed with the proof of the final theorem.

Theorem 4.

Let be a commutative ring with unity, and let P be a locally finite poset such that any maximal chain in P contains at least three elements. The additive biderivation b of the incidence algebra is the sum of several inner biderivations and extremal biderivations.

Proof.

We proceed by first considering the case where P is connected. The general case will follow by extending this result to each connected component of P.

Case 1: P is connected.

For any , we can decompose them as follows:

Using these decompositions, we expand the biderivation :

- I.

- Evaluating :

Consider

From Lemma 6 and Theorem 2, we have

By Corollary 3 and Lemma 4, the part of each term in (54) can be expressed as

By Theorems 1 and 4, the other part of each term in (54) can be expressed as

- II.

- Evaluating ,we have

Consider elements and , where each pair in is comparable. A maximal chain, denoted by , exists in P that contains . There exist and , where are defined in (10), such that and . It is obvious that , then l would belong to both and . Thus, we get , which contradicts Lemma 1.

Hence, the existing pair of elements among is not comparable, and by Lemma 6, it follows that

Therefore,

- III.

- Evaluating ,we have

From Lemmas 2 and 6, the part in above equation is non-zero only when any pair in is compared and , which implies either or . Thus, the sum simplifies to

- IV.

- Evaluating :

First, consider :

From Lemma 2, unless or . Therefore,

Similarly, for , we obtain

Combining these results, we have

Combining All Components:

Consider the aforementioned points; we thus deduce the following result:

Case 2: P is not connected.

When P is disconnected, we utilize the decomposition (7):

where each is a connected component of P. Further, each connected component can be decomposed as

using decomposition (11).

For any , write

where , as per decomposition (8).

Since each is connected, applying the result from Case 1, we obtain

Therefore, combining all components, we conclude that

as desired. It is evident that b is the sum of several inner biderivations and extremal biderivations. □

Remark 5.

The decomposition in the main theorem can be understood in three intuitive steps. First, Lemma 6 reduces the problem to comparable pairs, so the analysis localizes to connected chain components of the poset. Second, on each chain component, the constancy result (Theorem 3) produces scalar weights that result in the inner biderivation terms. Third, Theorems 1 and 2 show that only finite maximal chains produce additional terms that cannot be absorbed into inner parts; these survive as , i.e., the extremal biderivations. Thus, the "inner + extremal" decomposition reflects a structural constraint imposed by the chain decomposition of the poset.

It is evident that if there are no where x is the minimal element and y is the maximal element, . Consequently, the next corollary holds.

Corollary 5.

Let P be a poset that has at least three elements, and let be a commutative ring with unity. In the incidence algebra of P over , if the number of elements in any maximal chain in P is infinite, every additive biderivation is the sum of several inner biderivations.

Example 4.

We conclude by describing the structure of an arbitrary additive biderivation b on , where is the poset introduced in Example 3. Recall that

For any , the biderivation takes the form

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, Z.G.; Writing—review and editing, C.Z.; Supervision, C.Z.; Project administration, C.Z.; Funding acquisition, C.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The National Natural Science Foundation of China grant number 12101111.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rota, G.-C. On the foundations of combinatorial theory: I. theory of Möbius functions. In Classic Papers in Combinatorics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1964; pp. 332–360. [Google Scholar]

- Haiman, M.; Schmitt, W. Incidence algebra antipodes and Lagrange inversion in one and several variables. J. Comb. Theory Ser. A 1989, 50, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Spiegel, E.; O’Donnell, C. Incidence Algebras; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1997; Volume 206. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, R.P. Structure of incidence algebras and their automorphism groups. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 1970, 76, 1236–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pierre, L.; John, S. Structure of incidence algebras of graphs. Commun. Algebra 1981, 9, 1479–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibils, C. Cohomology of incidence algebras and simplicial complexes. J. Pure Appl. Algebra 1989, 56, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, W.R. Incidence Hopf algebras. J. Pure Appl. Algebra 1994, 96, 299–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z. Jordan derivations of incidence algebras. Rocky Mt. J. Math. 2015, 45, 1357–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Baclawski, K. Automorphisms and derivations of incidence algebras. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 1972, 36, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yang, Y. Nonlinear derivations of incidence algebras. Acta Math. Hung. 2020, 162, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornaroli, É.Z.; Khrypchenko, M. Skew derivations of incidence algebras. Collect. Math. 2025, 76, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Nonlinear Lie derivations of incidence algebras. Oper. Matrices 2021, 15, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Khrypchenko, M. Lie derivations of incidence algebras. Linear Algebra Its Appl. 2017, 513, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kaygorodov, I.; Khrypchenko, M. Poisson structures on finitary incidence algebras. J. Algebra 2021, 578, 402–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkovič, D. Biderivations of triangular algebras. Linear Algebra Its Appl. 2009, 431, 1587–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosseiri, N.M. On biderivations of upper triangular matrix rings. Linear Algebra Its Appl. 2013, 438, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brešar, M. Commuting maps: A survey. Taiwan J. Math. 2004, 8, 361–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).