Abstract

Purpose—Through the study, we discovered the key factors for decision makers involved in public crisis governance with respect to deciding whether to cooperate or not, and to understanding how they relate to governance performance. Methodology—This study extends the classic NK model, constructs an agent-based model to simulate the decision-making process of collaborative public crisis governance, and analyzes the effects of individual trust level, the level of cooperative relationship between individuals, and the standard deviation of the individual trust level on governance performance. Findings—This study found that when the complexity of a public crisis event is high, a high level of trust in the participants and a slightly lower level of inter-individual partnership would be appropriate in order to improve the responsiveness of governance decisions. If a small number of high-quality governance decisions are pursued, and there are high levels of trust and standard deviations of trust levels of the participating governance agents, as well as a strong level of partnership between individuals, it will result in more in-depth, comprehensive and high-quality governance decisions. Value—Although this study has slight shortcomings concerning the homogeneity of the choice of participating governance agents and the sensitivity of the simulation experiment, it has some theoretical contributions regarding decision making for collaborative public crisis governance.

Keywords:

willingness to collaborate; collaborative governance performance; public crises; NK Model; agent-based model MSC:

90B05

1. Introduction

So-called “public crisis management” is a government’s activities aimed at reducing and avoiding serious harm caused by crises during the occurrence and progression of public emergencies, and their efforts to make the necessary decisions and conduct follow-up management of crises according to the public crisis-governance plan [1]. However, with the rapid development of the global economy, countries around the world have entered an era of risk with frequent outbreaks of public crises. Faced with the increasing prominence of the destructive, dynamic, random, and non-linear nature of public crisis events, a single government decision can no longer meet the needs of public crisis governance. In response to complex and volatile public crisis events, the United Nations Global Crisis Response Team, in collaboration with relevant agencies, has discussed the collaboration of multiple agents in disaster response and efforts to reduce the impact of disasters, as well as the reporting and sharing of information in support of national, regional, and global disaster-response efforts [2]. They have also suggested that a social governance community should be established in the face of public crises to ensure that all groups in a society can participate in governance activities. From this perspective, the public crisis-governance model should be shifted from the traditional model of single government management to one in which the government, enterprises, social groups, and citizens participate together. This is a collaborative model of public crisis governance that integrates online and offline elements, thus effectively enhancing the effectiveness of public crisis governance [3].

In fact, the essence of collaborative public crisis governance is an innovative solution mechanism that mobilizes multiple social agents to form a governance group to respond to public emergencies [4]. Waugh [5] has suggested that the efficiency of the decisions of the participating governance agents determines the overall performance of crisis governance. According to TPB theory, an individual’s decision-making behavior is not 100% voluntary, but is limited by the perception of self-behavioral control, that is, the individual’s willingness to act [6]. This shows that individual behavioral intentions can determine individual decisions and can be maximized to obtain optimal decisions. However, in the process of collaborative public crisis governance, the willingness of participating parties to act collaboratively often changes due to relational, perceptual, efficacy, social, and interactive factors, thus affecting the performance of collaborative public crisis governance. In a study, Steven [7] states that individuals with a preference for synergistic behaviors contribute to an improvement in overall management performance. As psychological research becomes more sophisticated, more and more studies are proving this point [8,9]. For this reason, some studies have introduced the behavioral assumption of synergistic willingness [10]. However, the impact of individual willingness to collaborate on the performance of collaborative public crisis management is still underappreciated in theoretical studies.

This study’s focus on the collaborative willingness of participants in public crisis governance stems from observations of the behavior of groups involved in the governance of public health emergencies in the aftermath of COVID-19. Individuals participate in public crisis governance mostly from their own will, and their trust and partnership with other individuals are the main factors that govern the actions of participating subjects [11]. However, due to the different social divisions of individuals, each participant has a very different education and perception of change, which often directly affects the individual’s own sense of trust and perception of partnership. This determines the differences in individual willingness to collaborate, which seriously affects the quality of public crisis-governance decisions and is an important concern for timely and effective public crisis governance.

For the study of public crisis performance, traditional assessment models assume that the relationship between variables is linear. However, in complex crisis situations, where causal relationships are often nonlinear and of individual intention, too-simple linear models cannot accurately capture this complexity. This paper introduces the individual collaborative willingness into the process of collaborative governance of public crises, and considers the participating subjects to be intelligent entities with autonomous decision-making ability. Through the three aspects of perceiving the environment, reacting, and interacting with other agents or the environment, this paper explores the influence of individual collaborative willingness on the performance of collaborative governance of public crises, with a view to providing theoretical reference for the participation of multi-agents in collaborative governance of public crises. Kyle et al. [12] defined individual limited rationality as an individual’s partial attention to the problem space in their study of the impact of individual limited rationality on crowdsourcing performance based on the NK model, which provides a modeling idea for this paper to study individual willingness to collaborate. The parameters in the NK model include the number of genes N, the number of interactions K, and the number of alleles A. Mooweon et al. [13] addressed the response to team restructuring and collective problems based on the NK model, which provides ideas for conducting quantitative research on collaborative governance of public crises. Based on the findings of scholars, this research defines individual willingness to collaborate as individuals’ partial attention to the problem space and considers three dimensions of willingness to collaborate: the level of individual trust, the level of partnership between individuals, and the standard deviation of the level of individual trust. By introducing individual willingness to collaborate and extending the classical NK model, an agent-based model of the collaborative governance process in public crises is constructed. The effects of individual trust level, the level of partnership between individuals, and the standard deviation of individual trust level on the performance of collaborative public crisis governance are also explored.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Collaborative Public Crisis Governance

In recent years, countries around the world have been repeatedly threatened by public emergencies that have caused serious damage to economies and societies. In order to respond to the complexity of public crisis events, governments at all levels need to adopt new tools and methods to improve the speed and accuracy of public crisis-management decisions. In recent years, collaborative governance has become one of the governance approaches in the field of public administration to respond effectively to emergencies. Since the concept of collaborative public crisis management was proposed, many scholars have conducted a series of studies on collaborative public crisis management based on the practice of emergency management, and a large amount of research results have been formed. Logar et al. [14] summarized the research results of collaborative public crisis management in the past decade and found that the current understanding of the academic community is not uniform, but generally agreed that collaborative public crisis management has four basic characteristics. Firstly, there is a synergy of multiple agents in the process of public crisis management. Secondly, the occurrence of a public crisis event is usually a complex task that is difficult for a single governance entity to tackle alone. Thirdly, participating governance agents can choose to accomplish their governance tasks through collaboration or independently. Finally, collaborative public crisis management is a collaborative, multifaceted, shared-governance task-solving mechanism. Based on the basic features of collaborative public crisis management, this research focuses on how the subjects involved in the collaborative public crisis-management decision-making process can make quick decisions through self-learning, self-adaptation, and self-organization in a complex and changing environment, and can continuously optimize their own decisions so as to promote the optimal decision-making of the collaborative group.

2.2. NK Model

For public crisis events, the adoption of a collaborative governance approach to address governance issues includes aspects of ex ante prevention, ex post control and ex post treatment [15]. A governance task will often have multiple decision options, and although it is difficult to judge the merits of governance decision options initially, it can be determined that potential decision options for a governance task have many dimensions, and that the synergy of these dimensions affects the performance of the overall governance decision. At the same time, all potential decision options form a problem space, and the essence of a governance decision is the process of searching for a satisfactory decision option in the problem space by the participating governance agents [16]. Based on existing research findings, we find that the NK model is well suited to explore the problem of self-learning, self-organization, and self-adaptation of individuals in adaptive landscapes to adjust their own decision-making options in order to drive optimal group decisions, and to effectively characterize the decision-making process.

The NK model was originally applied to the problem of biological evolution in biology [17]. When analyzing at the genotype level, Kauffman [18] proposed the NK model, a new approach to biological evolutionary fitness that can be simplified. By optimizing Wright’s concept of adaptive landscape, Kauffman constructs a topology for mapping gene attributes to their adaptive production, analyzes the correspondence between the number of genes a species contains (N) and the number of interactions affecting genes (K), and ultimately concludes that the NK model is a better global overall optimal adaptive result obtained with the help of a continuous search for local optima. Following this, Levinthal [17] synthesized the NK model with simulation tools and introduced it into organizational management research. He pointed out that the correlated effects of different attributes of the organization can make the fitness landscape rugged, where N denotes the number of decisions contained in the organization, with two choices for each decision, then the fitness landscape contains possible combinations of decisions, and the parameter K denotes the ruggedness of the fitness landscape, that is, the complexity of the task. The application of the NK model to the fields of self-organization, adaptive behavior and organizational behavioral performance has validated the applicability of the NK model in management, while advancing the development of adaptive landscape theory in organizational behavior and strategic management. Theoretically, organizational management problems can all be assumed to be an efficient combination of multiple interdependent decision factors, and the complex adaptability of organizational management problems can be clearly characterized through the NK model [19].

Today, NK models have been widely used in social science research areas such as organizational management systematization [20], supply chain management [21], innovative product development [22], industrial green innovation [23], and problem solving [7]. In subsequent studies, scholars have explored how individual decision-making behavior affects collective problem solving through the NK model. For example, Lazer [19] studied the impact of different network topologies on collective problem solutions based on the NK model. Vuculescu [24] combines the NK model with a multi-subject simulation model to address the decision-making behavior of individuals in organizations faced with complex problems. The above research results provide a reference idea for this research to carry out quantitative research on collaborative public crisis management, which is an important theoretical basis for the modelling of this paper.

2.3. Willingness to Collaborate

Willingness to collaborate is the key for individuals to decide whether to start cooperation or not. Most scholars believe that the stronger the individual’s willingness to collaborate, the more it helps to trigger collaborative innovation behavior and the more effective the group collaborative behavior [25]. Dan et al. [26] explored how manufacturers’ willingness to cooperate in the supply chain not only accelerates the cooperation process, but the positive spillover effect can also benefit manufacturers by enabling them to gain more profits. One of the main motivations for the collaborative governance model as an efficient way of governance in public administration is the willingness to share information, which can significantly contribute to the effectiveness of collaborative action [27]. Willingness to collaborate can lead to positive behavior by individuals through actively seeking cooperation. Groups with a strong willingness to collaborate generally have a greater awareness of the need to proactively seek external cooperation and resources. For public crisis management, collaborative willingness can effectively mobilize the participation of multiple social agents and effectively coordinate social capital to improve governance performance [28]. Some scholars classify the willingness to collaborate as an internal factor, which is a manifestation of individual subjectivity, mainly in the form of relational, perceptual, and efficacy factors [29]. However, some scholars have pointed out that willingness to collaborate is influenced by external factors. In the case of public crisis management, interactional and social factors have a positive impact on individual willingness to collaborate [30]. Compared to research on other aspects of collaborative governance, there is less scholarly research on the willingness to collaborate.

With regard to the factors influencing willingness to collaborate, scholars in psychology have identified sustained and effective collaborative innovation as one of the key drivers of participants’ strong willingness to collaborate [31]. However, lasting collaborative innovation requires the full trust of individuals in the outside world and the support of good partnerships between individuals. Since the level of trust of individuals in the outside world is closely linked to the ability of individuals to form good partnerships with each other, we need to focus on the problem space of the level of trust of individuals. On those dimensions that are important or easily observable, direct or indirect experience is used to draw causal links and patterns between individual trustworthiness and inter-individual partnerships. This paper draws on the research method of the mental model [32] to construct a “trust representation” rule model suitable for this study, using the sparsity of individual trust-representation dimensions to interpret the degree of partnership between individuals. Individuals’ willingness to collaborate, then, is mainly reflected in their subjective representations of trust, which form their mental model of the problem of collaborative governance of public crises.

Although previous studies have mentioned that the external environment can cause changes in individual trust representations, few scholars have investigated how trust representations affect the evolutionary process of individual self-learning and self-adaptation, and how the level of trust at the individual level affects the synergistic performance at the group level. Brown [33] considered individual willingness to cooperate in building distributed teams and suggested that individual trust is a core element of virtual collaboration formation. The changing external environment also affects the level of individual trust and thus the performance of distributed teamwork. Kyle et al. [12] proposed the Interpersonal Communication Model framework (ICM) to explore the impact of the external environment on individuals’ propensity to trust, perceived trustworthiness, willingness to communicate, and ultimately on their willingness to cooperate and sustainability of cooperation. From this, we can see that these scholars have only focused on the influence of individual willingness to collaborate on individual self-adaptation, but have not considered the influence of individual willingness to collaborate on group collaborative behavior.

To fill the gap, this study draws on Mooweon et al.’s definition of collaborative willingness, which is the willingness of members within an organization to collaborate with each other subjectively in order to accomplish the organization’s goals. Three dimensions of willingness to collaborate are represented using trust representations: the level of individual trust, the degree of inter-individual partnership, and the standard deviation of the level of individual limited rationality. The level of individual trust reflects a comprehensive assessment of an individual’s reliability, honesty, and competence in a given context. The degree of inter-individual partnership reflects the depth and efficiency with which multiple subjects collaborate with each other under a common goal or task. It is a measure of the level of trust, communication, resource sharing, and coordination between individuals. The standard deviation of an individual’s limited level of rationality reflects the degree of variation in individual trust levels. A series of simulation experiments are also used to explore the effects of individual trust levels, the degree of partnership between individuals, and the standard deviation of individual trust levels on the performance of collaborative public crisis management, thereby filling the gaps in existing research. Table 1 lists some selected research works.

Table 1.

A brief summary of most relevant works.

3. The Models

3.1. Basic Model

This study draws on the findings of Kauffman [21] to construct an agent-based model that simulates the decision-making process of collaborative public crisis management based on the NK model, which provides a reference for quantitative research on collaborative public crisis management. The basic model is as follows.

3.1.1. The Problem Space of Public Crisis-Governance Tasks

When the public crisis-governance task includes decisions, we use -dimensional binary numbers to represent the decision choices. The choice of each decision can be 0 or 1. Then the problem space of the public crisis-governance task is of size , if when , the problem space is . Also, because in the governance decision process each decision does not exist independently, there are interactions between decisions, so let be the interactions between decisions, and . means that there is no influence between decisions, and means that each decision is influenced by other decisions, which also indicates that when is larger decisions are more likely to be influenced by other decisions. Therefore, the value of K also indicates the complexity of the task of public emergency management.

3.1.2. Decision-Making Program for Individual Governance Tasks

When a public emergency occurs, it is assumed that there are individuals involved in the process of public emergency governance, each with their own decision-making options for governance tasks. As the individual decision options correspond to the governance task of an unexpected public event, an -dimensional binary array is also used to represent the decision options for the individual governance task.

3.1.3. Adaptive Adaptation of Individual Governance Decision-Making Options

As this study is concerned with maintaining collaboration and cooperation with other individuals in the process of completing decisions on governance tasks, individuals rely on their own adaptive behavior to continually adjust their decision-making options for governance tasks. By changing the decision in any one of the N dimensions of the decision solution [22], the quality of the decision solution is compared and analyzed to see whether it has improved, and if so, it is adopted; otherwise, it is not.

3.1.4. Evaluation of Decision-Making Options for Public Crisis Management

The evaluation of public crisis-governance decision-making options includes both the evaluation of decision-making options for individual governance tasks and the evaluation of public crisis-governance performance. In general, the assessment of a decision option for an individual governance task can be represented by the performance of that decision in the task-adaptation landscape. Assume that a decision in a public crisis-management decision scenario takes the value , and use a randomly generated value from a continuous uniform distribution of to denote the contribution of that decision as . The contribution of each decision in a public crisis-governance decision scenario to task governance performance is influenced not only by its own taking, but also by the decisions of other participating governance agents with which it cooperates [17,22]. Denoting the decisions by the vector , the contribution of any decision to the performance of the governance decision programme is calculated as shown below.

However, the overall performance of a public crisis governance decision program is represented by the average size of the contribution of the decisions of the collaborative governance agents, which is calculated as:

Regarding the performance of collaborative public crisis governance, scholars’ studies have shown that it can be measured by the number of subjects involved in governance, the quality of emergency decisions, the timeliness and openness of information management, the adequacy of constraints and monitoring mechanisms, and the reciprocity of rights and responsibilities [39,40,41]. However, Waugh argues that the adequacy of constraints and monitoring mechanisms, as well as the reciprocity of rights and responsibilities, are highly subjective and difficult to use as a valid measure of public crisis governance performance. Thus, the number of agents involved in governance and the quality of emergency decisions are better ways to measure the performance of public crisis governance [12]. McGuire further elaborates on Waugh’s view that the average quality of emergency decisions of multiple actors involved in governance should be used to measure crisis-governance performance. He emphasizes that improvements in the quality of decisions made by each of the subjects involved in governance will affect the overall performance of collaborative public crisis governance [42]. Therefore, this research follows McGuire’s findings and uses the average quality of emergency decisions of the participating agents to represent collaborative public crisis-governance performance.

3.2. Extended Model

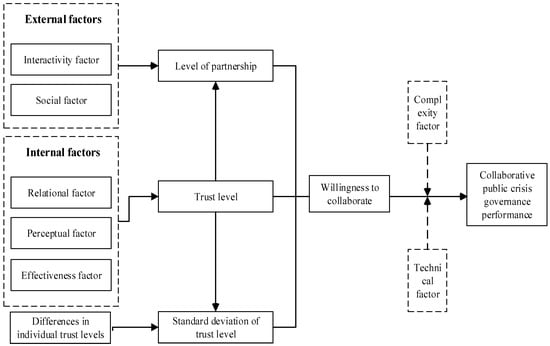

Regarding the participation of multiple agents in public crisis governance, some scholars have pointed out that the willingness to collaborate has an impact on public crisis governance performance, but the results vary considerably. For example, Dan [26] and Lette [43] argue that willingness to collaborate and governance performance have a mutually reinforcing effect. An increased level of willingness to collaborate contributes to improved governance performance, while the degree of governance performance also influences the change in collaborators’ willingness to collaborate. In contrast, Jarmai [44] argues that the willingness to collaborate is not conducive to team innovation and only contributes to overall team performance in a competitive relationship. In this study, we refer to the research results of Kyle et al. [12], characterize individual willingness to collaborate by introducing individual trust level, inter-individual partnership degree, and standard deviation of individual trust level, and modify and extend the basic NK model with three covariates, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

An extended NK model for collaborative public crisis governance.

3.2.1. Level of Individual Trust

In this paper, the level of individual trust (LIT) is expressed using the trust-representation dimension scale [45,46]. When the dimension of the adaptive landscape is , the dimension of the trust representation is then and the problem space of the trust representation should be . There are decision configurations in the trust-representation problem space for each decision configuration with its corresponding adaptation landscape. This can be understood as the property that each point in the problem space of the trust representation corresponds to points in the fitness landscape. Thus, assuming that the fitness value of each point in the trust-representation problem space is less than or equal to the average fitness value of points in the fitness landscape corresponding to this point, then:

Then, the individual chooses the point with the highest fitness in the problem space of trust representations as their own trust representation, thus completing the “climbing” process in the fitness landscape over and over again. It is worth noting that although the trust-representation fitness value is an unbiased estimate of the fitness value of the true landscape, the participating governance subjects cannot use the trust representation to predict the fitness value of a specific point in the fitness landscape. That is, the trust representations of the participating governance subjects do not fully reflect the true problem space.

3.2.2. Level of Inter-Individual Partnership

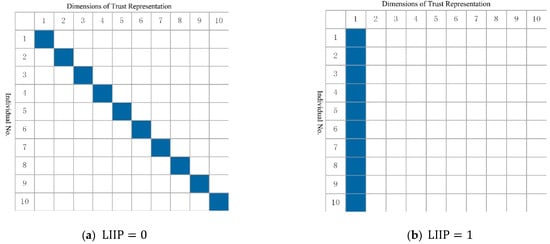

Psychology focuses on the relationship between inter-individual partnerships and individual levels of trust. According to Denrell [47], partnerships between individuals require that “all individuals in the group have the same level of trust”. As this study focuses on the influence of individual trust levels on the problem space, the level of inter-individual partnership is understood to mean that some individuals within the group have the same level of trust. This paper then defines the degree of inter-individual partnership as the extent to which individuals build a centralized rather than a random distribution of the dimensions of trust representation. Thus, often the higher the level of partnership between individuals, the more compact the dimensions of individual trust representations, meaning that trust representations are built by concentrating on a few dimensions. Conversely, the lower the level of partnership between individuals, the looser the dimensions of individual trust representations, meaning that the trust representations built by individuals fall on multiple dimensions. This results in a very small number of individuals building a trust representation in a given dimension. To better reflect the connotation of the level of inter-individual partnership (), this paper expresses as the ratio of the dimensions in the problem space of the governance task that are not characterized by any individual building trust to those that are potentially likely not to be characterized by any individual building trust. This is shown by Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Rules for building trust representations for individuals at different LIIPs when , , and .

As can be seen in Figure 2, when and , the trust-representation rules corresponding to the two cases of low level of partnership between individuals () and high level of partnership between individuals () are different for a governing group consisting of () individuals. Where the blue area indicates that the corresponding individual builds a trust representation on that dimension. When , each individual builds a trust representation on 1 () dimension, without considering individual differences in trust levels. If all individuals build trust representations on the same dimension, then the dimensions of the problem space that potentially may not be built by any individual are:

where int is a function for rounding.

In Figure 2a, there are individuals building trust representations in each dimension and the dimension of the problem space that is not built by any individual is , meaning that . In Figure 2b, all individuals build trust representations in the same dimension and the dimension of the problem space that is not built by any individual is , so .

From this, the rule algorithm can be defined as:

At this point, the larger the , the greater the likelihood that the trust representation will be concentrated in the front dimension of the problem space when is certain.

3.2.3. Standard Deviation of Individual Trust Level

To further consider the case where there is variation in the trust level of individuals in the governance group, this paper assumes that the trust level of individual conforms to a normal distribution, and therefore the trust level of individuals is assigned a random value that conforms to a normal distribution; that is, , and ; the mean of the normal distribution is , which reflects the average trust level of all individuals; the standard deviation is , which reflects the variability of the trust level of individuals [34,48]. Specific explanations are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameter explanation.

4. Simulation Results and Discussion

In this research, software was used for the agent-based model-simulation experiments [49]. The experimental parameters are shown in Table 3, where and were set by default according to Rivkin [50] and Oyama [12], while a sensitivity analysis was conducted for both and , respectively, to ensure the rigor of the simulation results and they were found to be consistent with the findings for . According to Miller et al. [51,52,53], a group size of can reflect large-scale group characteristics. The initial values of the other variables are set to , , and respectively. To avoid randomness, each experiment was run 100 times with different random number seeds for 150 cycles each, and the average result of the last cycle of the 100 experiments was used as the basis for analysis, along with the effect of each experimental parameter on the results according to a power-variance theory perspective [19].

Table 3.

Experimental parameters.

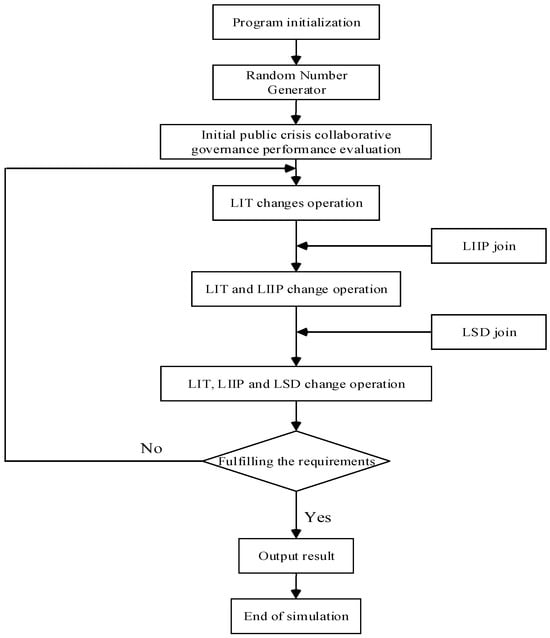

The experimental process of this paper is as follows:

First, we focus on the impact of individual trust levels on the performance of collaborative public crisis management.

Second, the level of inter-individual partnership is introduced to focus on the impact of the level of inter-individual partnership on the performance of collaborative public crisis management under different levels of individual trust.

Finally, the standard deviation of individual trust level was incorporated into the experimental process to investigate the impact of the interaction terms in individual trust level, level of inter-firm partnership, and standard deviation of individual trust level on the performance of collaborative public crisis governance. The process is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Extended NK model agent-based model-simulation flow chart.

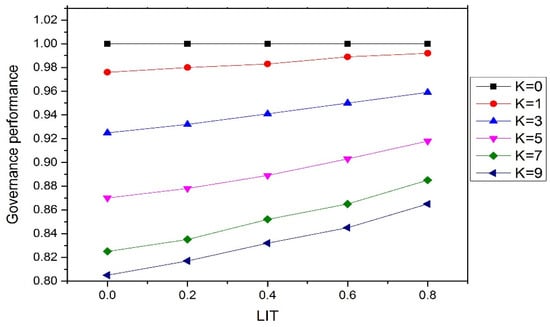

4.1. Impact of Individual Trust Levels

Figure 4 depicts the impact of individual trust levels on collaborative public crisis-governance performance at different levels of public crisis-governance task complexity. As the figure shows, on the one hand, task complexity has a negative impact on collaborative public crisis-governance performance, which means that the higher the task complexity, the lower the collaborative public crisis-governance performance. On the other hand, the level of individual trust has a positive impact on the performance of collaborative public crisis governance. Except for the case of task complexity , the performance of collaborative public crisis governance gradually increases as the level of individual trust increases when the complexity takes other values. The impact of individual trust levels on collaborative public crisis-governance performance is particularly significant when task complexity takes on higher values.

Figure 4.

The relationship between individual trust levels and collaborative public crisis-governance performance in situations of varying task complexity.

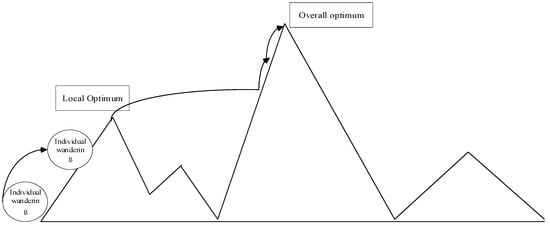

This suggests that when the interaction between public crisis-governance task decision items is greater and the adaptive landscape of the problem space is more rugged, it is more difficult for individuals to search for governance task decision options in the adaptive landscape and they are more likely to fall into the local optimum trap (as shown in Figure 5). Higher levels of personal trust can provide individuals with a better starting point for their search as they navigate through the rugged adaptive landscape, avoiding prematurely falling into a local optimum, which can effectively improve overall governance performance.

Figure 5.

Individual adaptive wandering and local optimum traps.

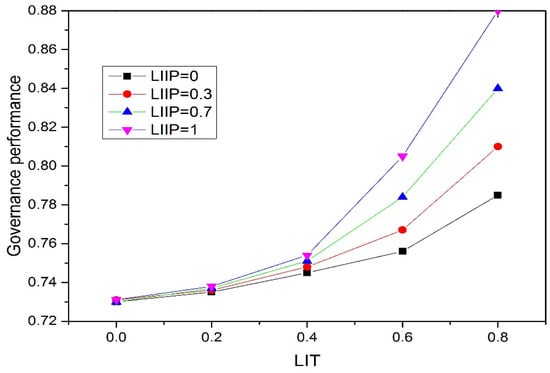

4.2. Impact of the Level of Inter-Individual Partnerships

Figure 6 depicts the impact of the level of inter-individual partnership on collaborative public crisis-governance performance at different levels of trust. As can be seen from the figure, when the level of individual trust is low (), the level of inter-individual partnership has little effect on the performance of collaborative public crisis governance. The reason for this is that lower levels of individual trust have less of an impact on public crisis governance, so that the level of inter-individual partnership in the corresponding condition has an even smaller or a negligible impact on collaborative public crisis-governance performance. However, the higher the level of individual trust (), the greater the level of partnership between individuals, the higher the public crisis governance performance. Therefore, we can see that the level of inter-individual partnership has a positive impact on public crisis-governance performance, but is dependent on the level of individual trust.

Figure 6.

The relationship between the level of individual trust, the level of inter-individual partnership, and the performance of collaborative public crisis governance.

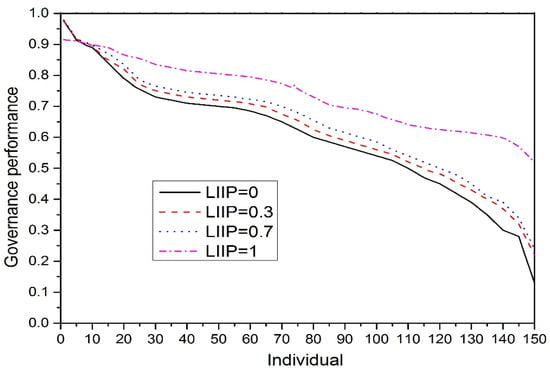

In general, individuals building trust representations in different dimensions can increase the diversity of decision options for governance tasks, thus contributing to the long-term improvement of collaborative public crisis-governance performance. However, an interesting finding of this research is that at the initial state, the diversity of decision-making options of the participating governance agents is lower, which means the higher the level of inter-individual partnership, the higher the collaborative public crisis-governance performance. To better explain this, this paper analyzes the distribution pattern of the final performance of the 150 participants’ governance decisions at different levels of inter-individual partnership when the level of individual trust is high (), as shown in Figure 7. It can be seen that when the degree of partnership between individuals is low (), there are a few very high performing governance decision options. When the degree of inter-individual partnership is very high (), although no very high performing governance decision options emerge; the vast majority of governance decision options outperform those with a low degree of partnership.

Figure 7.

Distribution of the performance of the 150 participating governance agents’ decision-making options under different levels of inter-individual partnership.

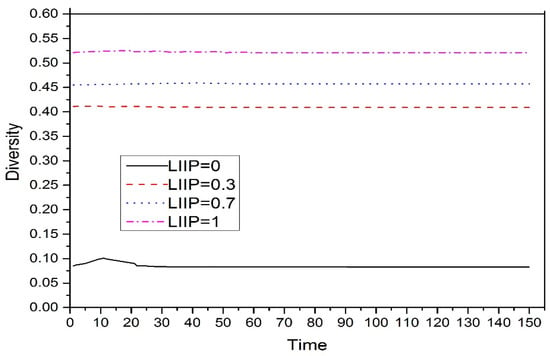

With a high level of inter-individual partnership, why do most participating governance agents have relatively high performance in their decision-making options? To further understand the underlying reasons, this research assumes a high level of individual trust () and observes the evolution of the diversity of decision-making options of the participating governance agents under different levels of inter-individual partnership, as shown in Figure 8. As can be seen from the figure, when the level of inter-individual partnership is higher, the diversity of decision-making options of participating governance agents is lower, meaning that increasing the level of inter-individual partnership reduces the diversity of decision-making options for collaborative public crisis governance, verifying the negative effect of the level of inter-individual partnership on the level of diversity of governance decision-making options. When the level of partnership between individuals is very high (), although the initial level of diversity in the group is low, individuals adjust their decision options by “climbing” and “jumping” local optimality traps in the problem space. The level of diversity of decision options in the group shows a process of increasing and then decreasing, and we can understand this phenomenon as a process of self-learning and self-adaptation of the collaborative governance group driven by the individuals. This is the reason why the performance of public crisis governance is improved, as individuals continue to explore and find better solutions, while they navigate the problem space to reach the overall optimum. This is what has been referred to in the literature as “Transient Diversity” [54]. Conversely, when the level of partnership between individuals is low (), although the initial group decision is more diverse, with the process of individual wandering in the problem space it is very easy to fall into the local optimal trap, then it is also difficult to reach consensus between individuals in the group, which is not “Transient Diversity”, so the performance of public crisis governance does not improve greatly.

Figure 8.

The evolutionary process of the diversity of decision-making options for subjects involved in governance with different levels of inter-individual partnership.

When the complexity of a public crisis event is high, it is easy for the participating governance agents to fall into the trap of local optimality in the problem space during the search for the optimal decision solution. When individuals start their search from widely different positions, the potential for falling into different local optimality traps increases, resulting in a relatively high and low variation in the diversity of decision options in the governance process, without “Transient Diversity”. The result is poor consistency in decision-making options for collaborative governance groups. However, when individuals are searching from similar starting positions, the potential for individuals to fall into different local optima is reduced, and the participating governance agents experience “Transient Diversity”. Then, the diversity of decision options will be lower than the initial state, which means that it will be easier to reach a consensus among the participating governance agents to obtain a deeper governance decision option, and therefore the final public crisis-governance performance will be improved accordingly.

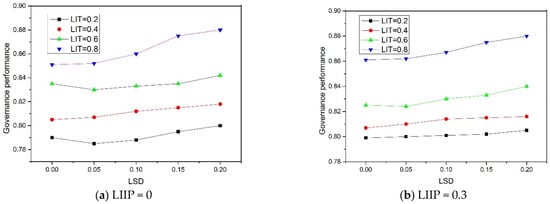

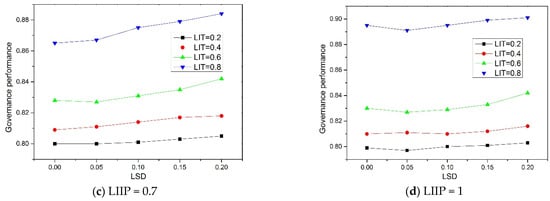

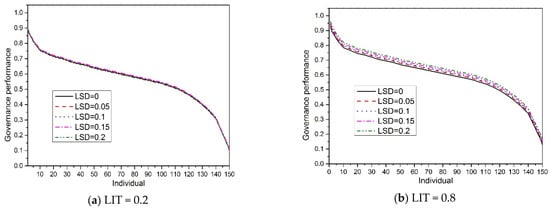

4.3. The Effect of the Standard Deviation of the Level of Personal Trust

In the above study, differences in the standard deviation of individual trust levels (LSD) were not considered. This section further analyzes the impact on the performance of collaborative public crisis governance when the standard deviation of individual trust level (LSD) is not zero.

According to the regression results in Table 4, it is clear that the level of individual trust has a significant effect on the performance of collaborative public crisis governance, and the interaction term between the level of individual trust and the level of partnership between individuals has a significant effect on the performance of collaborative public crisis governance, which supports the validity of the above analysis. However, the effect of the standard deviation of individual trust levels on the performance of collaborative public crisis governance was not significant, nor was the interaction term between the standard deviation of individual trust levels and the level of partnership between individuals on the performance of collaborative public crisis governance. The interaction terms of individual trust level, level of partnership between individuals, and standard deviation of individual trust level also had no significant effect on the performance of collaborative public crisis governance. However, the interaction term between individual trust level and the standard deviation of individual trust level has a significant effect on the performance of collaborative public crisis governance at the 0.05 level. In summary, compared to LIT and LIIP, LSD only explains a small difference in the performance of collaborative public crisis governance, and it is a minor factor.

Table 4.

Sig. values for LIT, LIIP, LSD regression analysis.

As the effect of on public crisis-governance performance is significant at the 0.05 level, we further analyze the mechanism of their interaction. Figure 8 shows the impact of LSD and LIT on public crisis-governance performance when the LIIP takes on different values. The differences in the performance of collaborative public crisis governance in Figure 9a–d is significant when the LIIP takes different values and the level of individual trust is large (). However, when individual trust levels were low (), there was no significant difference in the performance of collaborative public crisis governance. This can be interpreted as the impact of the LSD and LIT interaction terms on the performance of collaborative public crisis governance being dependent on LIT. To further illustrate the reason for this, when we look at the distribution of the final performance of the 150 participating governance agents when ,, and , respectively, the distribution of the final performance of the decision options for the 150 participating governance agents when the LSD is taken to be different is shown in Figure 10. It can be seen that when , the standard deviation of individual trust levels is increased, which means that some individuals with significantly different trust levels are introduced, but these individuals still have generally low trust levels and therefore have a very small impact on public crisis governance performance. When , increasing the standard deviation of individual trust levels is equivalent to introducing individuals with greater variability in trust levels, thus increasing the process of individuals experiencing “Transient Diversity” and ultimately improving public crisis-governance performance to a certain extent. Therefore, whether LSD has an impact on public crisis-governance performance relies on LIT.

Figure 9.

The effect of different conditions on the performance of decision-making options of governance agents under different standard deviations of trust levels.

Figure 10.

Distribution of the performance of the 150 participating governance agents’ decision-making options under different standard deviations of trust levels.

4.4. Discussion

This study extends the classical NK model by introducing individual willingness to collaborate and constructs an agent-based model that simulates the decision-making process of collaborative public crisis governance, and investigates the effects of individual trust levels, the level of partnership between individuals and the standard deviation of individual trust levels on the performance of collaborative public crisis governance. The simulation results found the following: (1) The complexity of public crisis events has a negative impact on the performance of collaborative public crisis governance. However, when the complexity of the task is high and the trust level of individuals is high, the performance of collaborative public crisis governance gradually increases, which indicates that individuals with high trust level can overcome the governance obstacles caused by the complexity of the task and thus achieve higher collaborative public crisis-governance performance. (2) The level of individual trust and the level of partnership between individuals have a positive impact on the performance of collaborative public crisis governance, and can contribute to the improvement of collaborative public crisis-governance performance. The standard deviation of inter-individual partnership level and individual trust level also have a positive influence on the performance of collaborative public crisis governance, but both depend on the level of individual trust. This suggests that the key factor in collaborative public crisis-governance performance is the level of individual trust. (3) The standard deviation of individual trust levels explains only a small part of the variation in collaborative public crisis-governance performance compared to individual trust levels and inter-individual partnership, and is a minor influence. In other words, the effect of individual differences on the performance of collaborative public crisis governance is secondary to the above two factors, and is not a decisive factor.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Research Contribution

The findings of this paper have some reference value for collaborative public crisis governance. When faced with a public crisis event, decision-makers need not be overly concerned that the complexity of the event will make it difficult for governance agents to make effective decisions that affect overall governance performance. Instead, the focus should be on how to increase the level of trust of subjects involved in public crisis governance, including trustworthiness, responsibility, achievement, risk perception, self-efficacy, and participation efficacy. Through them, we can increase the proportion of the parsimonious problem space that individuals can search as a percentage of the overall problem space, which can promote the overall optimal performance of collaborative public crisis governance. A low level of partnership between the agents involved in governance increases the diversity of public crisis governance options. Conversely, a high level of partnership between the agents involved in governance can increase the completeness of public crisis-governance solutions. This allows for the selection of appropriate governance decisions for different public crisis events.

5.2. Research Limitations

There are also some limitations and shortcomings in this paper. In order to eliminate the effect of differences in the social attributes of the subjects involved in public crisis governance on the simulation results, it was set up so that the subjects of public crisis governance were homogeneous and their social attributes had negligible influence on their decisions, so that it was not possible to prove whether this had an effect on the simulation results. In addition, the computational complexity of the NK model prevents the dimensionality of N from being too large. In this paper, sensitivity analysis is carried out for N of 8, 12, and 16 and the default setting of N = 16 is used for simulation experiments.

Author Contributions

Methodology, S.-n.S.; Software, S.-n.S.; Validation, Y.W.; Investigation, J.-j.H.; Resources, Y.-s.Z.; Data curation, R.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was supported by grants from Philosophy and Social Science Fund of Shenyang (Grant No. SY20230216Y).

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely appreciate the anonymous referees and editors for their time and patience devoted to the review of this paper as well as their constructive comments and helpful suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| Parameters | Acronyms | ||

| the number of genes | level of individual trust | ||

| the number of interactions | level of inter-individual partnership | ||

| a decision takes the value | a random value that conforms to a normal distribution | ||

| contribution of a decision | standard deviation | ||

| k decision-making | |||

| number of individuals in the partnership | |||

References

- Lee, S.; Yeo, J.; Na, C. Learning from the Past: Distributed Cognition and Crisis Management Capabilities for Tackling COVID-19. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2020, 50, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbass, K.; Begum, H.; Alam, A.S.A.F.; Awang, A.H.; Abdelsalam, M.K.; Egdair, I.M.M.; Wahid, R. Fresh Insight through a Keynesian Theory Approach to Investigate the Economic Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Pakistan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, W.; Aggerholm, H.K.; Frandsen, F. Entering new territory: A study of internal crisis management and crisis communication in organizations. Public Relat. Rev. 2012, 38, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therrien, M.C.; Beauregard, S.; Valiquette-L’Heureux, A. Iterative Factors Favoring Collaboration for Interorganizational Resilience: The Case of the Greater Montreal Transportation Infrastructure. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2015, 6, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waugh, W.L., Jr.; Streib, G. Collaboration and leadership for effective emergency management. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, S.S.; Ngo, H. The role of trust and contractual safeguards on cooperation in non-equity alliances. J. Manag. 2004, 30, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pablo González del Campo, J.D.S.; Pardo, I.P.G.; Perlines, F.H. Influence factors of trust building in cooperation agreements. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 710–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagosh, J.; Bush, P.L.; Salsberg, J.; Macaulay, A.C.; Greenhalgh, T.; Wong, G.; Cargo, M.; Green, L.W.; Herbert, C.P.; Pluye, P. A realist evaluation of community-based participatory research: Partnership synergy, trust building and related ripple effects. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrelja, R.; Rye, T.; Mullen, C. Partnerships between operators and public transport authorities. Working practices in relational contracting and collaborative partnerships. Transp. Res. Part A 2018, 116, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juana, C.S.; Filippos, E.; Salvador, S. Beliefs about others’ intentions determine whether cooperation is the faster choice. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7509. [Google Scholar]

- Oyama, K.; Learmonth, G.; Chao, R. Applying complexity science to new product development: Modeling considerations, extensions, and implications. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2015, 35, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, M.; Kim, T. Great Vessels Take a Long Time to Mature: Early Success Traps and Competences in Exploitation and Exploration. Organ. Sci. 2015, 26, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logar, S.; Alessandro, R. Diplomatic Collaborative Solutions to Assure the Adoption of the European Single Market Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 662170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson, E.; Granberg, M. Implementation through collaborative crisis management and contingency planning: The case of dam failure in Sweden. J. Risk Res. 2021, 24, 1335–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. The architecture of complexity. Proc. Am. Philos. Soc. 1962, 106, 467–482. [Google Scholar]

- Levinthal, D.A.; March, J.C. A model of adaptive organizational search. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1981, 2, 307–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, S.A. The Origins of Order: Self-Organization and Selection in Evolution; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lazer, D.; Friedman, A. The network structure of exploration and exploitation. Adm. Sci. Q. 2007, 52, 667–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billinger, S.; Stieglitz, N.S.; Chumacher, T.R. Search on rugged landscapes: An experimental study. Organ. Sci. 2013, 25, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, S.A. At Home in Universe: The Search for Laws of Self-Organization and Complexity; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; p. 405. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, J.R.; Lin, Z.; Carroll, G.R.; Carley, K.M. Simulation modeling in organizational and management research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 1229–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antolín-López, R.; Céspedes-Lorente, J.; García-de-Frutos, N.; Martínez-del-Río, J.; Pérez-Valls, M. Fostering product innovation: Differences between new ventures and established firms. Technovation 2015, 41–42, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuculescu, O.; Bergenholtz, C. How to solve problems with crowds: A computer-based simulation model. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2014, 23, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, A.; Geerdink, T.; Sprenkeling, M. Accelerated innovation in crises: The role of collaboration in the development of alternative ventilators during the COVID-19 pandemic. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dan, B.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Guan, Z.; Zhang, S. Should an online manufacturer partner with a competing or noncompeting retailer for physical showrooms? Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2021, 28, 2691–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafton, J.; Abernethy, M.A.; Lillis, A.M. Organisational design choices in response to public sector reforms: A case study of mandated hospital networks. Manag. Account. Res. 2011, 22, 242–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermicelli, S.; Cricelli, L.; Grimaldi, M. How can crowdsourcing help tackle the COVID-19 pandemic? An explorative overview of innovative collaborative practices. R D Manag. 2021, 51, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C. Stakeholder involvement in strategic adaptation planning: Trans-disciplinarity and co-production at stake? Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 75, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritala, P.; Poole, M.S.; Rodgers, T.L. What’s in it for me? Creating and appropriating value in innovation-related coopetition. Technovation 2009, 29, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, S.; Santos, M.F. Accountability Mechanisms in Public Services: Activating New Dynamics in a Prison System. Int. Public Manag. J. 2018, 21, 795–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thagard, P. Mind: Introduction to Cognitive Science; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, H.G.; Poole, M.S.; Rodgers, T.L. Interpersonal traits, complementarity, and trust in virtual collaboration. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2004, 20, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, C.A.M.; Burton, N.S.; Wilmer, J.B.; Blokland, G.A.M.; Germine, L.; Palermo, R.; Rhodes, G. Individual Differences in Trust Evaluations Are Shaped Mostly by Environments, Not Genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 10218–10224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, C.F.; Nohrstedt, D.; Baird, J.; Hermansson, H.; Rubin, O.; Baekkeskov, E. Collaborative crisis management: A plausibility probe of core assumptions. Policy Soc. 2020, 39, 510–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Wei, Y. Research on Collaborative Governance of Public Crisis Events Based on Big Data Information Processing Technology. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Conference on Management Science and Engineering Management (ICMSEM 2023), Nanchang, China, 2–4 June 2023; Volume 259, pp. 78–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, S.J. The Collaborative Governance Between Public and Private Companies to Address Climate Issues to Foster Environmental Performance: Do Environmental Innovation Resistance and Environmental Law Matter? Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 936290. [Google Scholar]

- Bentzen, T.O. Co-creation: A New Pathway for Solving Dysfunctionalities in Governance Systems? Adm. Soc. 2022, 54, 1148–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Liu, H.; He, L.; Lu, T.; Li, B. More collaboration, less seriousness: Investigating new strategies for promoting youth engagement in government-generated videos during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 126, 107019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, B.; Steelman, T.; Velez, A.; Albrecht, K. Co-management during crisis: Insights from jurisdictionally complex wildfires. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2022, 31, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.; Liu, Z.; Stephens, V.; White, G.R. Innovation in crisis: The role of ‘exaptive relations’ for medical device development in response to COVID-19. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 182, 121863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, M.; Silvia, C. The Effect of Problem Severity, Managerial and Organizational Capacity, and Agency Structure on Intergovernmental Collaboration: Evidence from Local Emergency Management. Public Adm. Rev. 2010, 70, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lette, M.; Boorsma, M.; Lemmens, L.; Stoop, A.; Nijpels, G.; Baan, C.; de Bruin, S. Unknown makes unloved-A case study on improving integrated health and social care in the Netherlands using a participatory approach. Health Soc. Care Community 2020, 28, 670–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarmai, K.; Vogel-Poschl, H. Meaningful collaboration for responsible innovation. J. Responsible Innov. 2020, 7, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, J.B. A New Scale for the Measurement of Interpersonal Trust. J. Personal. 1967, 35, 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rempel, J.K.; Holmes, J.G.; Zanna, M.P. Trust in Close Relationships. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 49, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denrell, J.; March, J.G. Adaptation as information restriction: The hot strove effect. Organ. Sci. 2001, 12, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Laibson, D.I.; Scheinkman, J.A.; Soutter, C.L. Measuring Trust. Q. J. Econ. 2000, 115, 811–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.H. Genetic algorithms. Sci. Am. 1992, 267, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivkin, J.W.; Siggelkow, N. Patterned interactions in complex systems: Implications for exploration. Manag. Sci. 2007, 53, 1068–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.D.; Zhao, M.; Calantone, R.L. Adding interpersonal learning and tacit knowledge to March’s exploration-exploitation model. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Rhee, M. Exploration and exploitation: Internal variety and environmental dynamism. Strateg. Organ. 2009, 7, 11–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, G.C.; Alavi, M. Information technology and organizational learning: An investigation of exploration and exploitation processes. Organ. Sci. 2007, 18, 796–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollman, K.J.S. The epistemic benefit of transient diversity. Erkenntnis 2010, 72, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).