Abstract

The problem of finding the metric dimension of circulant graphs with t generators (and their inverses) has been extensively studied. The problem is solved for , and some exact values and bounds are known also for . We solve all the open cases for .

MSC:

05C35; 05C12

1. Introduction

The metric dimension is an invariant that has wide applications, for example, in pharmaceutical chemistry [1], Sonar and coast guard Loran [2], and robot navigation [3]. Applications of the metric dimension to the problem of pattern recognition and image processing can be found in [4]. The concept of metric dimension was introduced by Slater [2] in 1975.

For a graph G with set of vertices , the distance between two vertices is the number of edges in a shortest path between u and v. The vertices u and v are resolved by a vertex w if . For an ordered set , the representation of distances of v with respect to W is the ordered z-tuple

The set is a resolving set of G if all the vertices of G have distinct representations (if every pair of vertices of G is resolved by a vertex of W). The number of vertices in a smallest resolving set is the metric dimension .

Circulant graphs have been extensively studied because they are particularly symmetric, and it is easy to set up such networks and check their properties. For and , the circulant graph has vertices , and edges , , where , and the subscripts are taken modulo n. The integers are the generators of .

Let us suppose that since is a complete graph for . We present the known results on for small t (and ). By [5,6], we have

By [5,7],

For , by [8],

and .

The metric dimension of was studied also in [9], the graphs were investigated in [10], in [11], in [12], where n is even in [13], in [14], and in [15].

In [16], it was shown that for , and by [17], for each there exists an n such that the bound is sharp. However, this bound does not hold for . Therefore, we are very interested in the case , and we solve all the open cases for .

Let us denote by . Since , we have . From Theorem 2.5 given in [18], we have for . This result was extended by Chau and Gosselin [19], who proved in their Theorem 2.7 that also for . By Theorem 2.13 from [19], for , where . By Lemma 8 and Theorem 10 given in [16], for . Thus, by [16,18,19], for where ,

From Table 3 presented in [19], we have .

By Grigorious et al. [20] (see Proposition 1.2 in [19]), we have

By Theorem 2.9 presented in [19], for . Thus, by [16,19,20], for where ,

In this paper, we study for .

2. Results

First, we prove an upper bound on for .

Theorem 1.

Let where . Then, .

Proof.

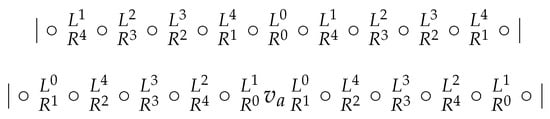

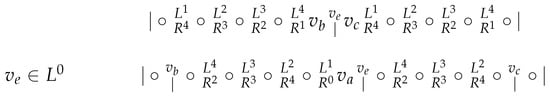

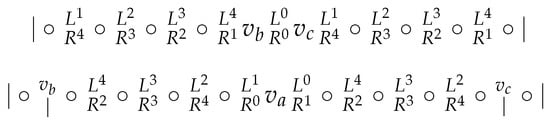

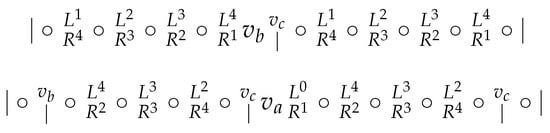

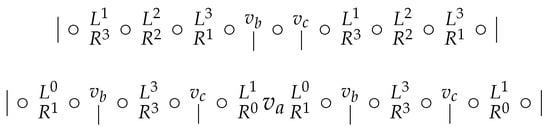

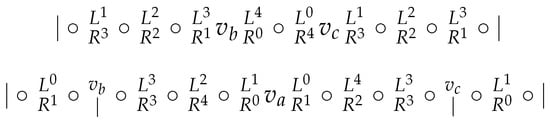

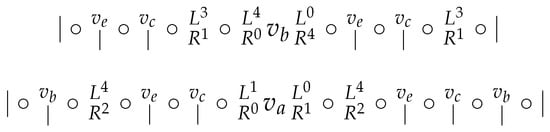

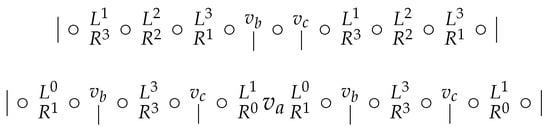

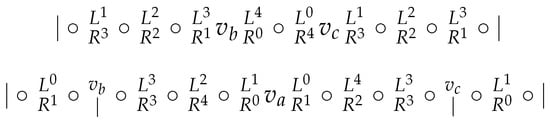

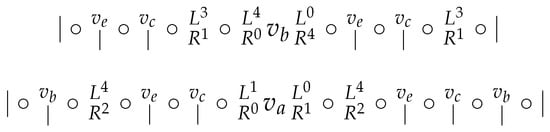

We show that is a resolving set of . Representations of distances of all the vertices in with respect to W are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Representations of vertices in with respect to W.

Since any two vertices have different representations, . ☐

Let be a vertex from a resolving set W. Then, resolves and , but it does not resolve any pair from . Analogously, resolves and , but it does not resolve any pair from . If and are resolved by and , then we say that creates a border between and . Observe that borders caused by split the vertices of into sequences of non-resolved vertices (by ). The only exception is itself since it does not create borders between and and between and (recall that we require in the definition of borders). The reason is that does not distinguish and . Of course, does not distinguish also from though in the sequence there are two borders caused by . But our aim is to construct a lower bound, so we need a necessary condition, not a sufficient.

So take all vertices of W and create all borders caused by these vertices. Then, these borders split around the cycle into many small sequences, which we call states. And the necessary condition for W to be a resolving set is that every state contains at most one vertex which is not in W. We use this condition in the proofs of the next theorems.

We need to distinguish the distance in from the distance in a subgraph () of . Therefore, by the index distance, we call the distance between the vertices of in . For example, and (the indices are always taken modulo n) have distance 1 in , but their index distance is 5.

We start with a lower bound on for .

Theorem 2.

Let , where . Then, .

Proof.

By way of contradiction, suppose that contains a subset W containing 7 vertices which are resolving. Observe that has diameter d and for every vertex , the vertices at distance d from are the 10 consecutive vertices (consecutive by index distance) , where .

Let . Since W must distinguish from , we have or or there is a vertex at index distance from for some . But since both and have index distance from , we conclude that W must contain a vertex at index distance from .

So for every , there is such that the index distance between and is a multiple of 5. Obviously, such a role as that which plays for is played also by for . And since , there must be a vertex in W, say , such that two vertices from W, say and , have an index distance that is a multiple of 5 from .

Not only this, but let and . Then, L, R, is a partition of . If both and are in R (or if they are both in L), then all mutual index distances between pairs of vertices of are multiples of 5. Hence, by symmetry, we may assume that , , and we may also assume that .

Now, we split L and R, each into five sets according to the index distance from (). Let . By (by ), we denote vertices of L (of R) whose index distance from is congruent to . (Observe that the index distance cannot be greater than .) Hence, and .

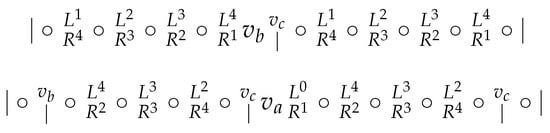

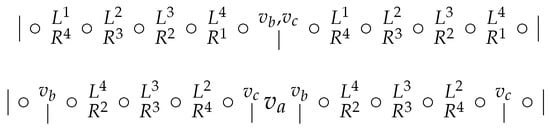

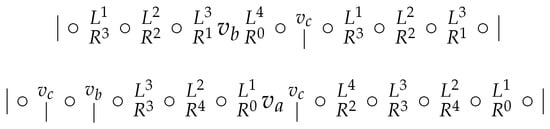

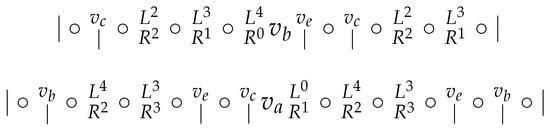

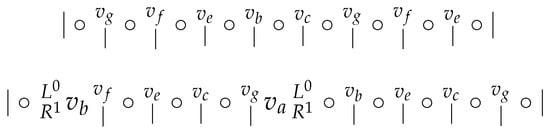

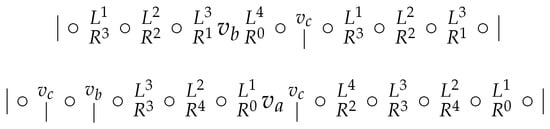

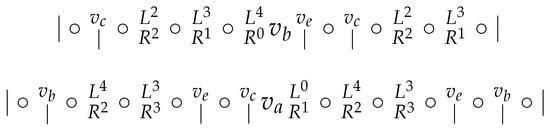

As mentioned above, for every , to distinguish from , there must be a vertex in W which is at index distance from . For instance, if , then to distinguish from , W contains a vertex, say , such that either (if is in L), or (when and the shortest index distance path contains ), or (when and the shortest index distance path does not contain ). In Table 2, we have all 10 cases according to being in , , …, . In each case, the vertex is from the union of the three sets.

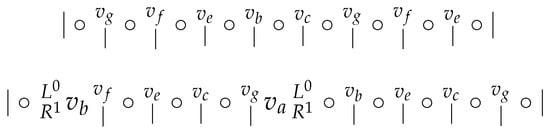

Table 2.

The 10 cases according to being in , , …, .

Let . Suppose that we have borders caused by vertices of W and the borders caused by the remaining i vertices of W are not considered yet. Moreover, suppose that there is a sequence of vertices, say , such that none of the already considered vertices is in and the already considered vertices do not create borders between any consecutive pair from . Then, cannot be among the remaining vertices of W. The reason is that each of the remaining i vertices of W causes, at most, one border in the sequence and if it is in , , then it causes no border in the sequence since every member of the sequence is at distance d from all the vertices from .

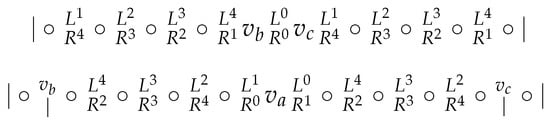

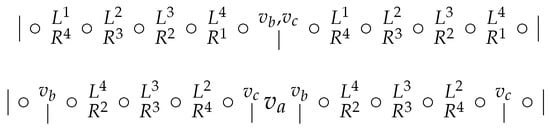

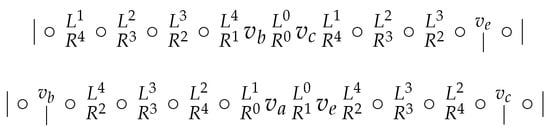

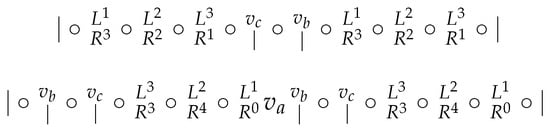

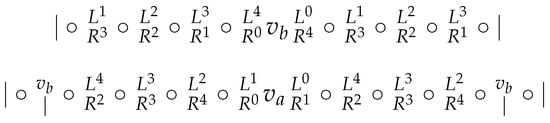

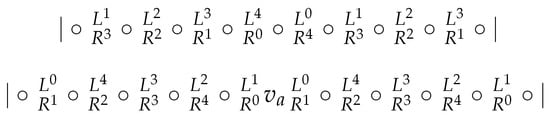

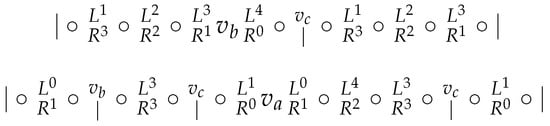

Denote 11 vertices which are at distance at most 1 from by , and denote 10 vertices which are at distance d from by . Then, both and form sequences of consecutive vertices. We consider the situation in and . In Figure 1, we describe and as they occur in the cycle (the other vertices are not depicted). Circles represent vertices of , and those whose position is already known, such as , are depicted instead of circles. Vertical lines are borders caused by , and in the space between vertices, we indicate which vertices may form the border. In fact, such vertices cause borders if and only if they are not in or , and therefore, situations when W contains vertices of or should be considered separately.

Figure 1.

Initial distribution.

Regarding the position of and in , by symmetry, we distinguish three main cases.

Case 1. .

See Figure 2, where we specify also the borders in caused by and .

Figure 2.

Case 1.

The vertices and must be distinguished, so there must be a border on the left-hand side of (or ) or on the right-hand side of (or ). By symmetry, we may assume that this border is on the right-hand side of . So for the next vertex , we have either , or but , or . We consider these subcases separately.

Subcase 1.1. .

So, . Now, the positions of four vertices of W are determined, see Figure 3. It remains to be determined the positions of the last three vertices, say, , and .

Figure 3.

Subcase 1.1.

At the moment, there is a sequence of four consecutive vertices in without a border, namely, , so since it remains to be determined the three vertices of W. Also, there is a sequence of four consecutive vertices in without a border, namely , so . Thus, there is a border between and , and also a border between and . This yields four possibilities.

(a) and . Since must be distinguished from , we have or . In any case, by Table 2, W does not contain a vertex at index distance from .

(b) and . By Table 2, since W must contain a vertex at index distance from . At the same time, since W must contain a vertex at index distance from , a contradiction.

(c) and . Since must be distinguished from and , we have . On the other hand, must be distinguished from and so , a contradiction.

(d) and . Since must be distinguished from , we have . However, by Table 2, W does not contain a vertex at index distance from .

Subcase 1.2. but (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Subcase 1.2.

At the moment, there are sequences of four consecutive vertices without a border in (), in (), and in (). Therefore, , and . Hence, there is a border between and and also a border between and . Analogously as in Subcase 1.1, we consider four possibilities.

(a) and . Since must be distinguished from and , we have . In any case, by Table 2, W does not contain a vertex at index distance from .

(b) and . This case can be solved analogously as in Subcase 1.1.

(c) and . Since must be distinguished from and , we have . On the other hand, must be distinguished from and , and so . Consequently, , and by Table 2, W does not contain a vertex at index distance from .

(d) and . This case can be solved analogously as in Subcase 1.1.

Subcase 1.3. .

This situation is presented in Figure 5. Here, if , or . In any case, .

Figure 5.

Subcase 1.3.

In this subcase, we have four consecutive vertices without a border in all , , and , and so and . Hence, there is a border between and , and also a border between and . This gives the same possibilities as in the previous two subcases, and they can be solved analogously as in Subcase 1.2.

Case 2. but (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Case 2.

The positions of three vertices of W are determined, and it remains to be determined the last four vertices. But at the moment, there is a sequence of five consecutive vertices without a border in , namely , and so . Thus, we distinguish eight possibilities.

(a) , and . By Table 2, since W must contain a vertex at index distance from . At the same time, since W must contain a vertex at index distance from , a contradiction.

(b) , and . By Table 2, since W must contain a vertex at index distance from . At the same time, since W must contain a vertex at index distance from , a contradiction.

(c) , and . Since must be distinguished from , we have or or . Summing up, . At the same time, since W must contain a vertex at index distance from , a contradiction.

(d) , and . By Table 2, since W must contain a vertex at index distance from . At the same time, since W must contain a vertex at index distance from , a contradiction.

(e) , and . To distinguish from , we have or or . But the case was already considered in Case 1. Hence, . At the same time, W must contain a vertex at index distance from , and so . To distinguish from , W must contain a vertex in or or . Consequently, . However, then, does not create the border between and . Since W does not contain a vertex in and , the vertices and are not resolved, a contradiction.

(f) , and . First, suppose that . To distinguish from , we have or or . Hence, . At the same time, since W must contain a vertex at index distance from , a contradiction. So . But then, does not create a border between and since , . But then, W does not contain a vertex at index distance from , a contradiction.

(g) , and . To distinguish from , we must have or or . Summing up, . At the same time since W must contain a vertex at index distance from , a contradiction.

(h) , and . By Table 2, since W must contain a vertex at index distance from . At the same time since W must contain a vertex at index distance from , a contradiction.

Case 3. (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Case 3.

Analogously as in Case 2, at the moment there are sequences of five consecutive vertices without a border in and , and so and . Thus, we distinguish eight possibilities analogously as in Case 2. And we can use the proofs from Case 2 since in Case 3, we have more restrictions (so it is even easier to obtain a contradiction). ☐

Finally, we present a lower bound on for .

Theorem 3.

Let , where . Then, .

Proof.

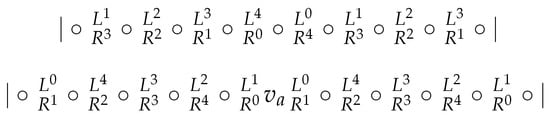

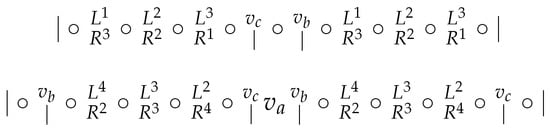

We proceed analogously as in the proof of Theorem 2. Let . Observe that the index distance is at most in . Obviously, has diameter d and for every vertex . There are nine consecutive vertices at distance d from , namely, .

By way of contradiction, suppose that contains a subset W of six vertices, which is resolving. Let . Denote and . Hence, . Analogously as in the proof of Theorem 2, we split L and R each into five sets according to the index distance from . Let . By (by ), we denote vertices of L (of R) whose index distance from is congruent to . (Recall that the index distance does not exceed .) To simplify the notation, we assume that .

Let . Suppose that we have borders caused by vertices of W and the borders caused by the remaining i vertices of W are not considered yet. Moreover, suppose that there is a sequence of vertices, say such that none of the already considered vertices is in and the already considered vertices do not form borders between any consecutive pair from . Then, cannot be among the remaining vertices of W. The reason is that each of the remaining i vertices of W causes at most one border in the sequence and if it is in , then it causes no border in the sequence since every member of the sequence is at distance d from all the vertices from .

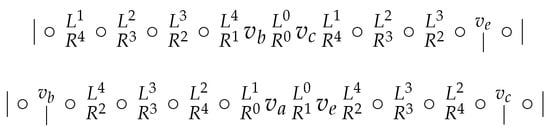

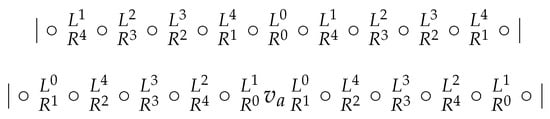

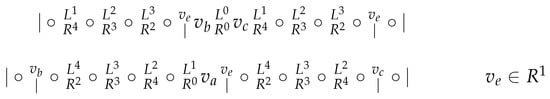

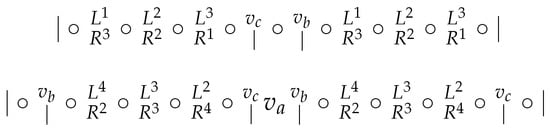

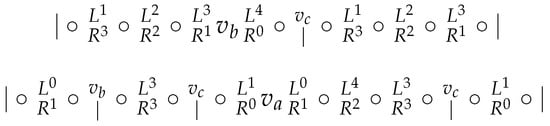

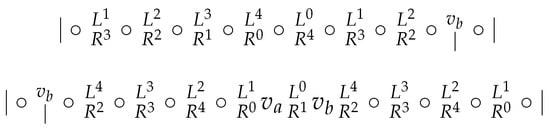

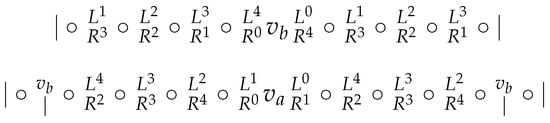

Denote 11 vertices which are at distance at most 1 from by , and denote 9 vertices which are at distance d from by . Then, both and form sequences of vertices, where neighboring vertices have index distance 1. We consider mainly the situation in and . In Figure 8, we describe and analogously as in the proof of Theorem 2. Circles represent vertices of , and those whose position is already known, such as , are depicted instead of circles. Vertical borders are borders caused by , and in the space between vertices, we indicate which vertices may form the border. Again, such vertices cause borders if and only if they are not in or , and therefore situations when W contains vertices of or should be considered separately.

Figure 8.

Initial distribution.

Before we start with cases, we exclude the possibility that two consecutive vertices are in W. So by way of contradiction, suppose that , see Figure 9.

Figure 9.

.

This yields a sequence of six consecutive vertices without a border caused by or . However, any vertex from creates at most one border in this sequence, and so W cannot distinguish all the vertices in this sequence, a contradiction.

To distinguish the three vertices , we need two vertices of W, say, and . In the following cases, we distinguish their position with respect to .

Case 1. . (By symmetry, we consider three subcases.)

Subcase 1.1. and (see Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Subcase 1.1.

At the moment, there is a sequence of four vertices without a border in , namely, . Thus, are not among the vertices of , and so . Analogously, , form a sequence of 4 consecutive vertices without a border in , and so .

Observe that even if . Hence, to distinguish from , we need . By now, this subcase is symmetric, so we may assume that . Recall that as mentioned above, . Now, we consider four possibilities with respect to .

(a) . Recall that . Since must be distinguished from , we have , and since must be distinguished from , we have . However, also must be distinguished from , and so W must contain a vertex in , that is a vertex in , a contradiction.

(b) and . In this case . To distinguish from we have , and to distinguish from we have . However, to distinguish from we conclude that , and to distinguish from , we conclude that .

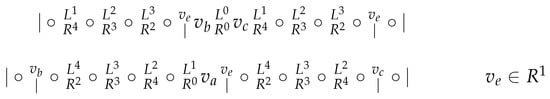

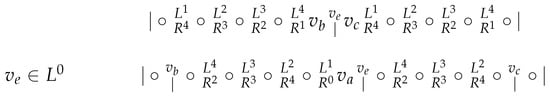

So we have , , , and . This choice works well in , see Figure 11. So denote , , , , and , , and analogously construct , , , , and where .

Figure 11.

Subcase 1.1.

Consider . We have , , , and . Observe that W does not contain a vertex in . Thus, the unique vertex must distinguish three consecutive vertices in (see Figure 8), a contradiction.

(c) and . In this case, . To distinguish from , we have , and to distinguish from , we have . However, to distinguish from we conclude that , and to distinguish from , we need a vertex of W in or (different from ) or , a contradiction.

(d) , that is and . To distinguish from , we have , and to distinguish from , we have . However, to distinguish from , the set W must contain a vertex of or or (different from ). Thus, or . And to distinguish from , the set W must contain a vertex in or or , and so . Now, if , then is not distinguished from , so we conclude that . This yields a situation which was already solved in case (b) above.

Subcase 1.2. and (see Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Subcase 1.2.

In each , , and , there are four consecutive vertices which are not resolved by , even if or . Since the sequence yields , and the sequence yields , we have .

Hence, to distinguish from , we have ; to distinguish from , we have ; and to distinguish from , we have . But also, must be distinguished from , and so . And since must be distinguished from , W must contain a vertex in , a contradiction.

Subcase 1.3. and , see Figure 13 (the case and is analogous, by symmetry).

Figure 13.

Subcase 1.3.

Recall that . So at the moment, the vertices are not distinguished, and so . That is, . Analogously are not distinguished since , and so .

Hence, to distinguish from , we have ; to distinguish from , we have ; and to distinguish from , we have . On the other hand, also must be distinguished from , and so . Since must be distinguished from , we have . And since must be distinguished from , we have .

So we have , , , and . Observe that if , then . Hence, relabeling a with x, we remain in Case 1, and in four out of these five possible relabelings, not all remaining vertices of W are in and also they are not all in . So, each of the four relabelings reduces this case to one of the previous ones.

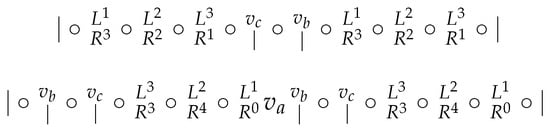

Case 2. and (see Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Case 2.

First, we focus on . To distinguish from we have . Recall that consecutive vertices cannot be in W. So, to distinguish from we have , which covers also the case . And to distinguish from , we have , which covers also the case . But we need to distinguish also from , for which we need a vertex of . Consequently, . But to distinguish from we need a vertex in other than , a contradiction.

Case 3. and .

Thus, . We distinguish two subcases.

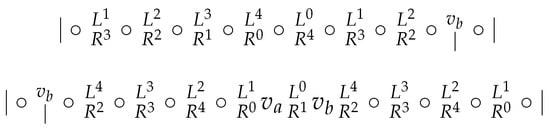

Subcase 3.1. (see Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Subcase 3.1.

At the moment, we have a sequence of 5 consecutive vertices without a border. The vertices in this sequence should be distinguished by three remaining vertices of W, which is impossible.

Subcase 3.2. , but (see Figure 16).

Figure 16.

Subcase 3.2.

At the moment, there is a sequence of four vertices without a border , , and so . To distinguish from , we have , and to distinguish from , we have . Finally, to distinguish from , we have which covers also the case (recall that since W does not contain consecutive vertices).

Now, we consider . To distinguish from , W must contain a vertex of , which covers also (recall that the case was already considered in Case 2), and so . To distinguish from , W must contain a vertex of (since ), and so .

Now, if , then . So considering and instead of and reduces the problem to Case 1 (recall that ). Hence, .

So , , and . But to distinguish from , W must contain a vertex in other than , a contradiction.

Thus, it remains to consider the last case, namely, when . But since all the other cases were solved already, we may assume that and .

Case 4. , and (see Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Case 4.

Obviously, two vertices from are in L, and two are in R. We assume that and . To distinguish from , W must contain a vertex in , which covers also the case . So we distinguish 2 subcases.

Subcase 4.1. .

Then, ; see Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Subcase 4.1.

To distinguish from , W must contain a vertex in , and so either and , or and . Since in the later case and are not distinguished, we conclude that and .

Now, consider and . We have , , and either and or and . However, both cases were already excluded in the previous paragraph.

Subcase 4.2. .

Then, ; see Figure 19.

Figure 19.

Subcase 4.2.

To distinguish from , W must contain a vertex in , and so either and , or and . Since in the former case and are not distinguished, we conclude that and .

Now consider and . We have , , and either and , or and . However, both cases were already excluded, which completes the proof. ☐

3. Conclusions

From our Theorem 1, we have for where . By (1), we have , and thus,

By Theorems 2.18 and 2.19 from [19], for . By Theorem 2.17 given in [19], for . We improved the lower bound in our Theorem 2 by proving that for . Thus,

From our Theorem 3, we obtain for . By [21], for the same values of n, we have , and thus

Note that from Table 3 given in [19], we have and .

Thus, the problem of finding the metric dimension of is now completely solved for and any n. We suggest continuing to try to solve the problem completely for .

Problem 1.

Find the metric dimension of for and any n.

Author Contributions

Methodology, M.K.; Software, R.Š.; Investigation, M.K. and T.V.; Writing—original draft, M.K.; Writing—review & editing, R.Š. and T.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

M. Knor acknowledges partial support by Slovak research grants VEGA 1/0567/22, VEGA 1/0069/23, APVV 19-0308 and APVV 22-0005. M. Knor and R. Škrekovski acknowledge partial support of the Slovenian research agency ARRS program P1-0383 and ARRS project J1-3002. The work of T. Vetrík is based on the research supported by DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Mathematical and Statistical Sciences (CoE-MaSS), South Africa. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the CoE-MaSS.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to find the results are included in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chartrand, G.; Eroh, L.; Johnson, M.A.; Oellermann, O.R. Resolvability in graphs and the metric dimension of a graph. Discrete Appl. Math. 2000, 105, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, P.J. Leaves of trees. Congr. Numer. 1975, 14, 549–559. [Google Scholar]

- Khuller, S.; Raghavachari, B.; Rosenfeld, A. Landmarks in graphs. Discrete Appl. Math. 1996, 70, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melter, R.A.; Tomescu, I. Metric bases in digital geometry. Comput. Vision Graphics Image Process. 1984, 25, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchert, A.; Gosselin, S. The metric dimension of circulant graphs and Cayley hypergraphs. Util. Math. 2018, 106, 125–147. [Google Scholar]

- Javaid, I.; Rahim, M.T.; Ali, K. Families of regular graphs with constant metric dimension. Util. Math. 2008, 75, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Imran, M.; Baig, A.Q.; Bokhary, S.A.; Javaid, I. On the metric dimension of circulant graphs. Appl. Math. Lett. 2012, 25, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorious, C.; Kalinowski, T.; Ryan, J.; Stephen, S. The metric dimension of the circulant graph C(n,±{1,2,3,4}). Australas. J. Combin. 2017, 69, 417–441. [Google Scholar]

- Vetrík, T. On the metric dimension of circulant graphs with 4 generators. Contrib. Discrete Math. 2017, 12, 104–114. [Google Scholar]

- Javaid, I.; Azhar, M.N.; Salman, M. Metric dimension and determining number of Cayley graphs. World Appl. Sci. J. 2012, 18, 1800–1812. [Google Scholar]

- Du Toit, L.; Vetrík, T. On the metric dimension of circulant graphs with 2 generators. Kragujevac J. Math. 2019, 43, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Azhar, M.N.; Javaid, I. Metric basis in circulant networks. Ars Combin. 2018, 136, 277–286. [Google Scholar]

- Salman, M.; Javaid, I.; Chaudhry, M.A. Resolvability in circulant graphs. Acta Math. Sin. (Engl. Ser.) 2012, 28, 1851–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Bokhary, S.A.U.H. On resolvability in double-step circulant graphs. U.P.B. Sci. Bull. Series A 2014, 76, 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Imran, M.; Baig, A.Q.; Rashid, S.; Semaničová-Feňovčíková, A. On the metric dimension and diameter of circulant graphs with three jumps. Discrete Math. Algorithms Appl. 2018, 10, 1850008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knor, M.; Škrekovski, R.; Vetrík, T. Sharp lower bounds on the metric dimension of circulant graphs. Commun. Comb. Optim. 2023, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetrík, T.; Imran, M.; Knor, M.; Škrekovski, R. The metric dimension of the circulant graph with 2t generators can be less than t. J King Saud Univ. Sci. 2023, 35, 102834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetrík, T. The metric dimension of circulant graphs. Canad. Math. Bull. 2017, 60, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, K.; Gosselin, S. The metric dimension of circulant graphs and their Cartesian products. Opuscula Math. 2017, 37, 509–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorious, C.; Manuel, P.; Miller, M.; Rajan, B.; Stephen, S. On the metric dimension of circulant and Harary graphs. Appl. Math. Comput. 2014, 248, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Z. On the metric dimension of circulant graphs. Canad. Math. Bull. 2023, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).