Abstract

In recent years, community detection has received increasing interest. In network analysis, community detection refers to the identification of tightly connected subsets of nodes, which are called “communities” or “groups”, in the network. Non-negative matrix factorization models are often used to solve the problem. Orthogonal non-negative matrix tri-factorization (ONMTF) exhibits significant potential as an approach for community detection within multiplex networks. This paper explores the application of ONMTF in multiplex networks, aiming to detect both shared and exclusive communities simultaneously. The model decomposes each layer within the multiplex network into two low-rank matrices. One matrix corresponds to shared communities across all layers, and the other to unique communities within each layer. Additionally, graph regularization and the diversity of private communities are taken into account in the algorithm. The Hilbert Schmidt Independence Criterion (HSIC) is used to constrain the independence of private communities. The results prove that ONMTF effectively addresses community detection in multiplex networks. It also offers strong interpretability and feature extraction capabilities. Therefore, it is an advanced method for community detection in multiplex networks.

MSC:

68R10

1. Introduction

There are many real systems, including social networks, collaboration networks, citation networks, and protein–protein networks, that represent complex networks. These networks express the connections between the same sets of nodes in different types of interactions through different layers. However, most traditional measures merely consider single-layer networks. But they do not consider the diversity of connections between entities. Thus, multiplex networks have been proposed recently to represent various modes of interaction. A multiplex network is a unique form of multilayer network in which every layer contains a distinct topology but the same types of nodes [1]. The most critical challenge of this network is effectively identifying and dividing the structure in the network, also called community detection.

The goal of community detection is to discover the clustering or partition of nodes in the network’s groups of nodes. There is a lot of connectivity between nodes. However, they have a shaky connection to other communities’ nodes. While there is a large body of work on community detection, most of it focuses on single-layer networks. Because they typically cannot handle multiple layers of the network simultaneously, traditional community detection methods often face challenges when dealing with multiplex networks. Three basic types of community discovery methods are now available for multiplex networks. The first approach directly simplifies the multiplex network into a single graph. After employing a flattening algorithm to merge the layers of a multilayer network into a single graph, traditional community detection algorithms are utilized for detection [2,3]. Nevertheless, the approach can only effectively identify the common communities across each layer of the network. It might also generate some spurious communities due to the flattening process, ultimately impacting the results of community detection. In the second approach, each layer is analyzed layer by layer using standard single-layer network community detection algorithms, with the results eventually combined. The application is referred to as Principal Modularity Maximization (PMM) and Spectral Clustering on Multilayer graphs (SC-ML) [4]. The third approach involves directly operating on the multiplex network model. Based on this category of methods, several algorithms have been proposed, including Locally Adaptive Random Transitions (LART) [5], Infomap [6], and multilayer community quality measure optimization-based techniques [7,8,9].

The existing community detection methods based on multiplex networks typically select a partition suitable for all layers [10]. However, no method simultaneously considers the shared communities across different layers and the unique communities existing in each layer. Therefore, for real-world complex networks, existing community detection algorithms often exhibit poor performance. The reason behind this is that, in real social networks, different layers often represent distinct interaction patterns, and each layer’s network is heterogeneous. For instance, in real social networks, students of a class might interact on different social platforms like WeChat, QQ, and Facebook. Each layer of the network corresponds to a specific social platform. On different platforms, each student may connect with different individuals. Hence, for a class of students, there may be common communities across each social platform. In the meantime, each layer possesses distinct communities. Based on the above, the goal is to address the challenge of simultaneously identifying both common and private communities within multiplex networks. Specific constraints are introduced for detected shared and unique communities, aiming to enhance the algorithm’s performance.

Non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) is a widely utilized technique in data mining and machine learning, exhibiting particularly unique advantages when dealing with high-dimensional data. In recent years, NMF has been successfully applied in various domains, including image processing, text mining, and bioinformatics. In the field of network science, particularly in community detection within multiplex networks, NMF has shown tremendous potential. In fact, NMF has been widely employed in community identification for single-layer networks, multiplex networks, multilayer networks, and dynamic networks because of its high interpretability and effect [11,12,13]. In a previous paper, an orthogonal non-negative matrix tri-factorization [14] model was proposed to detect each layer of the network separately. The proposed model decomposes each layer of the multiplex network into two low-rank matrices. The first component relates to the communities that are shared by all levels. Additionally, the second relates to the exclusive groups that are found inside each stratum. Compared to standard non-negative matrix factorization, orthogonal non-negative matrix tri-factorization decomposes the matrix into three independent parts, thereby offering stronger interpretability. Additionally, it can better extract features from the data, accurately capturing structural information. It considers additional orthogonal constraints, avoiding the overfitting issues commonly found in NMF and ensuring a more stable decomposition. It demonstrates better performance and applicability in multiplex networks compared to traditional non-negative matrix factorization.

Based on the above findings, this study introduces graph regularization [15] and Hilbert–Schmidt Independence Criterion (HSIC) [16] terms into the orthogonal non-negative matrix tri-factorization model. We calculate common communities separately for each layer and then synthesize the final common communities by incorporating weights. The contributions of the paper are as follows:

- An orthogonal non-negative matrix tri-factorization model is applied to multiplex networks. It enables the simultaneous detection of common and private communities within the network. The model has enhanced interpretability and feature extraction capabilities.

- For the detected private communities, a graph regularization [15,17] constraint is added. Graph regularization utilizes the topological structure of networks to better capture relationships and connection patterns between nodes. It constrains the formation of community structures. And it aligns more with the actual community partitioning rules in real networks. Finally, it enhances the accuracy and robustness of community detection.

- The Hilbert–Schmidt Independence Criterion (HSIC) [16] term is introduced. Because the private communities in each layer are independent of each other with minimal correlation, an HSIC term is added to the detected private communities [18]. The HSIC effectively imposes independence constraints on the private communities in each layer.

- Weight constraints are applied to the identified shared communities in each layer [19]. Ultimately, the shared communities across all layers are summed, enhancing the accuracy of the detected common communities.

The remaining sections of this paper are structured as follows. The second section describes related work. Section 3 introduces some notations and definitions. The proposed algorithm is introduced in Section 4. Section 5 describes the updating process of the algorithm. In Section 6, various datasets and comparison models are introduced in detail. Then, the experimental results are analyzed. In Section 7, conclusions and further research are covered.

2. Related Works

2.1. Existing Methods

The method proposed in this paper directly operates on multiplex network models. This category of algorithms includes various types: methods based on random walks, statistical generative network models, label propagation, objective function optimization, and non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) methods.

The community detection method based on random walkers is a commonly used network analysis technique. It involves simulating the behavior of random walkers in the network to discover community structures. The basic idea is to start from a node in the network, randomly select a neighboring node to move to, and repeat this process until certain conditions are met. By simulating the behavior of random walkers multiple times, the degree of association between nodes can be obtained, finally identifying community structures. The authors of [5] proposed LART, a method based on a random walk on a multiplex network. The community detection method based on random walkers has advantages such as simple implementation, suitability for large-scale networks, and the ability to detect overlapping communities. However, it needs various parameters. The selection of parameters in the algorithm may affect the final community detection results. When processing large-scale networks, it requires a considerable amount of computational resources and time.

Statistical methods such as the weighted stochastic block model (WSBM) detect shared and unique communities in heterogeneous weighted networks. While this approach tackles the problem of network heterogeneity across layers, it overlooks communities that might be shared by specific subsets or different combinations of layers. By considering the weights of edges in the network, the weighted stochastic block model can capture more nuanced relationships between nodes compared to traditional binary network models. However, for large networks with a high number of nodes and edges, the weighted stochastic block model can be computationally intensive.

The Label Propagation Algorithm (LPA) is based on the idea of label propagation. The basic principle of the LPA is to propagate initial labels (or communities) in the network until the nodes in the network reach a stable state. Firstly, each node is initially assigned a unique label (or community). Then, labels propagate in the network, with each node adopting the most common label among its current neighboring nodes. When the labels of all nodes no longer change, the algorithm reaches a stable state. Finally, nodes with the same label are considered to belong to the same community. In general, the LPA is suitable for community detection in large-scale networks. But it may not accurately identify overlapping communities or communities with clear hierarchical structures in some cases.

In community detection for multilayer networks, methods based on optimizing objective functions are commonly used to identify communities that span across different layers of the network. These methods aim to find the partition of nodes into communities that maximizes/minimizes a specific objective function, which captures the quality of the community structure. One popular approach for community detection in multilayer networks is to extend traditional modularity optimization to multilayer settings. Another method for optimizing objective functions in multilayer community detection is to use a variation of the stochastic block model (SBM). The SBM is a generative model that assumes nodes belong to different blocks (communities). And it can define the probability of edges between nodes based on their block assignments. In the multilayer setting, the SBM is extended to model interactions within and between layers. It succeeds in detecting communities that exist across layers.

The majority of the above-mentioned methods only consider the shared communities across all or most layers. They all overlook the possibility of shared communities existing in subsets of different layers. They also do not detect the unique communities. In methods based on NMF, the number of communities is also provided through prior information.

2.2. Multiplex Networks

A multiplex network is a special multilayer network in which each layer has the same nodes, but its network topology is different. Like single-layer networks, a finite graph sequence can also be used to depict multiplex networks, where l represents the number of layers, L}, [20]. The collection of layer l nodes is denoted by , and is the adjacency matrix for layer l, where characterizes the relationship between and . In this paper, binary and undirected weighted adjacency matrices are employed. For both the weighted adjacency matrix and the binary adjacency matrix, . We have if and otherwise in each layer of the network.

2.3. Hilbert–Schmidt Independence Criterion (HSIC)

To determine the degree of independence between two random variables, statisticians employ the Hilbert–Schmidt Independence Criterion (HSIC). It is based on kernel methods in Hilbert–Schmidt space and was introduced by Gretton et al. [21]. The primary application domains of the HSIC include machine learning, statistical, and kernel methods. The HSIC quantifies the correlation between two variables by comparing their representations in the feature space. Each of the detected private communities is independent of the others, meaning their topological structures are entirely different from each other. Hence, the algorithm proposes the following version of the HSIC as a measure of independence between two private communities:

where and represent the detected private communities in the l-th and m-th layers, respectively. And , and is the n-dimensional identity matrix, where n is the dimension of the matrix. The larger the value of the HSIC, the stronger the correlation between X and Y; conversely, a smaller HSIC indicates a weaker correlation. The HSIC equals zero only when X and Y are independent. For the kernels and , the inner product function is chosen, i.e., , . Substituting it and the expression for and into Equation (1), the following formulation is obtained:

2.4. Community Detection with NMF in Multiplex Networks

Non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) [22] is an extensively employed algorithm in community detection. The model has been widely applied in many fields [23]. A non-negative matrix can be broken down using NMF into the product of two or more other non-negative matrices, thereby capturing the latent structures within the data. In the context of community detection, NMF has been successfully utilized to uncover potential modular structures and is particularly well suited for representing the non-negative characteristics inherent in the data. Given a non-negative matrix , NMF attempts to find two non-negative matrices, and , such that and . and are found by solving the following optimization problem:

The community feature matrix (X) and community indicator matrix (U) are both community detection techniques based on NMF. The algorithm adds the orthogonality constraint to both factor matrices, and , resulting in better performance. Each row in or has only one non-zero element due to the requirements of orthogonality and non-negativity, which suggests that each node is only a member of one community. The decomposed matrix is an adjacency matrix. Typically, the number of communities is expressed as k [24,25].

The algorithm research on community detection in single-layer networks has been improved, and various non-negative matrix decomposition algorithms based on single-layer networks have been widely applied and achieved good performance [26]. However, in the research of multilayer networks, the non-negative matrix factorization algorithm has not been widely applied. The main reason is that the traditional non-negative matrix factorization algorithm cannot detect the relationship between communities in a multilayer network. It only applies to the single-layer network. For community detection in two-layer and more-than-two-layer networks, there are two basic models: one is a multilayer network, and the other is a multiplex network [27]. In the multilayer network, there are interlayer connections between the network nodes of the adjacent layers. In the multiplex network, each layer has the same type of entity, and there are no node connections between adjacent layers.

For multilayer networks, an existing model is Community Detection in Fully Connected Multilayer Networks Through Joint Non-negative Matrix Factorization [28,29]. The approach views a multilayer network as a hybrid of a bipartite graph network and a multiplex network. In the network, there are intralayer edges of a multiplex network and interlayer edges of a bipartite graph network, so an intralayer adjacency matrix and an interlayer adjacency matrix are introduced in this method. And considering the connectivity between intralayer communities and interlayer communities, its objective function is as follows:

where the coefficient matrices are and . The first one corresponds to intralayer adjacency matrices. The second one represents interlayer adjacency matrices. The low-rank embedding is denoted by .

Ref. [30] proposed an orthogonal non-negative matrix tri-factorization approach for community discovery in multiplex networks. The algorithm decomposes the adjacency matrix of each layer into two terms, each of which is an orthogonal non-negative matrix tri-factorization. The first item represents the common community of all levels, and the second item represents the private community of each level. The algorithm is as follows:

assuming that . The community membership matrices are and . One represents a common community, and the other corresponds to a private community. and are symmetric matrices. This method performs community detection on a multiplex network with L layers, where the number of private communities in each layer is denoted by . And the number of common communities is indicated by .

Multilayer network connection is taken into account in the model presented in [29]. However, the approach is limited to networks with two layers. When the number of layers in the network increases, the adjacency matrix between the adjacent layers also increases. This will lead to the model becoming more and more complex. For a multiplex network, the model in [30] only divides the community in a multiplex network into common communities and private communities. However, it does not perform a separate study of the separate common and private communities.

3. Notations

Some notations are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Notations and definitions.

4. The Proposed Method

ONMTF breaks down the adjacency matrix of each layer into the sum of the low-rank representations of exclusive communities and shared communities. Then, considering that the common communities of all layers are the same, the shared communities obtained in each layer are summed by weight. The private communities are independent of each other, and the independence between any two private communities is constrained by the HSIC. Finally, graph regularization is added for each layer’s private community.

For a given multiplex network [20] with l layers, the adjacency matrix for each layer is . One way to formulate the resultant objective function is as follows:

where and , are the community membership matrices. One represents a shared community, and the other corresponds to an exclusive community. and are symmetric matrices. The second term is used to sum the weights of the common communities of all the obtained layers, where is the weight factor. The predefined private matrices are not related to each other, and the third part uses the HSIC to impose correlation constraints on the private matrices of each layer. denotes the regularization constant, and is the Laplacian matrix. For each layer, , where is a diagonal matrix that is defined by , and is a weight matrix. The Laplacian matrix depends on the definition of . Should nodes i and j be linked, = 1. Otherwise, = 0. We have . For each layer, due to the differences in the adjacent matrix, we have .

5. Optimization

To resolve the updating rules for , , , , and , Lagrange multipliers and are introduced. The Lagrangian function is minimized:

To update , is found as follows:

= 0 and are applied. We acquire

Finally, the updated rule for is obtained:

For every , we also derive the update rules for , , and :

The updated of each layer is fused with the corresponding weights, and finally, the common community member matrix is obtained:

Since NMF algorithms are initialized with random matrices and different runs may return different results, we repeat the algorithm 100 times. As shown in Algorithm 1, for each random initialization of , , and , they all follow the update rules described in the corresponding formula. Finally, we choose the maximum performance value of different running results for calculation. According to the NMI value, the difference of community detection effect is judged.

| Algorithm 1 MX-ONMTF based on graph regularization and diversity. |

|

6. Experiments

6.1. Datasets

Real-World Multiplex Network:

Lazega Law Firm Multiplex Social Network [31]: The Lazega Law Firm is a complex social network consisting of 71 nodes. It has three layers. Each layer represents different types of relationships within the firm. Additionally, the dataset includes various attributes for each node. There is no ground-truth community in this network, but the detected community structure and node attributes of each type can be used to calculate the NMI and analyze the performance of the community detection by this metric. The calculation method of NMI comes from [8]. For each attribute, the nodes are divided into different communities based on specific attributes.

3sources: The 3sources dataset comprises data from three distinct network layers (BBC, Reuters, and The Guardian) that represent different types of relationships or interactions among entities. It provides valuable insights for studying complex networks [32].

BBCSport: The BBCSport dataset is a collection of data that encompass various sports articles published by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). It includes articles covering a wide range of sports, such as football, cricket, rugby, and tennis [32].

Wikipedia: The Wikipedia dataset is a comprehensive collection of data extracted from the Wikipedia website. The Wikipedia website is a vast online encyclopedia covering a wide range of topics in multiple languages. It includes articles, images, metadata, and other types of content contributed by users from around the world. The dataset provides valuable resources for various research tasks, including natural language processing (NLP), information retrieval, knowledge extraction, and data mining [33].

Table 2 shows the basic information of the three datasets. For each dataset, N is the number of nodes, k is the number of layers, and c is the number of communities. The last line represents the size of each community.

Table 2.

The information of real-word datasets.

Benchmark Multiplex Networks:

The generated multiplex networks based on the model in [34] are used. It suggests creating multilayer networks with community structures in two steps. First, it is necessary to manually define the parameters in the multilayer network, including the number of layers, the number of nodes, and an interlayer dependency tensor. The interlayer dependency tensor outlines the interlayer dependency structure. Then, there will be a partition of the multilayer network. Next, according to a degree-corrected block model, edges are generated within each layer. They are generated by constraints on the distribution of expected degrees and the community mixing parameter . The modularity of the network is governed by the mixing parameter . When , all edges are contained in communities. Therefore, the closer is to 1, the denser the distribution of nodes in the community, and the closer is to 0, the higher the independence of edges. For multiplex networks, the interlayer dependency tensors of all layers are uniform. Their range of values is from 0 to 1. When , the partitions of all layers are independent. indicates identical cross-layer partitions.

6.2. Experimental Settings

6.2.1. Comparison Algorithm Models

In this study, five comparison models were used for community detection in multiplex networks. The methods include Generalized Louvain (GL), Co-Regularized Spectral Clustering (CoReg), Multi-view clustering via Adaptively Weighted Procrustes (AWP), and Multi-view Consensus Graph Clustering (MCGC).

MX-ONMTF [30] operates by simultaneously factorizing multiple layers of the network data into three non-negative matrices. A shared basis matrix captures common structural patterns across layers. Two layer-specific coefficient matrices reflect the participation of nodes in each layer’s communities. By enforcing orthogonality constraints on the shared basis matrix, MX-ONMTF effectively disentangles the intertwined community structures present in multiplex networks.

Generalized Louvain (GL) [35] is an algorithm designed for community detection in complex networks. The core idea of GL is to iteratively optimize a quality function that measures the modularity of the network partitioning. GL efficiently identifies communities that exhibit strong internal connections. And it allows nodes to belong to multiple communities simultaneously. Overall, GL offers a flexible and effective approach for detecting communities in a wide range of network structures.

Co-Regularized Spectral Clustering (CoReg) [36] is a clustering algorithm designed to handle data with multiple views or modalities. Co-Regularized Spectral Clustering jointly clusters data from multiple views while leveraging the shared information across views.

Multi-view clustering via Adaptively Weighted Procrustes (AWP) [37] is an innovative clustering algorithm. AWP tackles the challenge of integrating information from diverse views by employing an Adaptively Weighted Procrustes analysis.

Multi-view Consensus Graph Clustering (MCGC) [38] is an algorithm designed to cluster data that come from multiple sources or views. Differing from traditional clustering methods, MCGC combines information from different views by constructing a consensus graph that captures the common structure across views.

Notably, all of these algorithms, except for GL and MX-ONMTF, require the user to specify the number of communities to look for a priori. It is usually denoted by k. This is a potential drawback in practice, as we usually do not have information about the community structure of the graph and would have to make some (possibly unjustified) assumptions about the number of clusters.

In experiments, the co-regularization parameter in CoReg [36] is set to 0.01. In AWP [37], the number of neighbors used in graph construction is fixed to 20. For MCGC [38], there is one parameter in the objective function. We fix for all the datasets. For MX-ONMTF [30], there are no parameters in the algorithm. The community can be detected directly.

6.2.2. Evaluation Metrics

The performance of community discovery techniques is analyzed in this study using Normalized Mutual Information (NMI). Let the ground-truth community label set be represented by . The one that a detector predicts is shown by . Ultimately, the NMI is ascertained:

where n represents the number of nodes, and K is the number of communities. is the number of nodes that are assigned to community j by a detector, but actually belongs to community i. is the node count in the ground-truth community i. is the number of nodes. It is allocated to community j by a detector. The larger the NMI value, the better the performance of the community detector [24].

6.3. Analysis

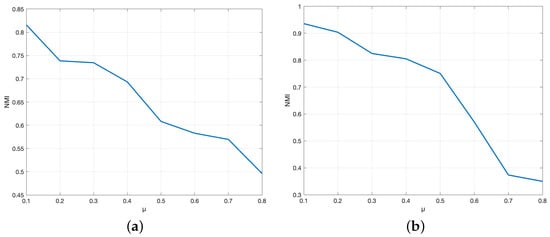

The proposed algorithm is first used to perform community detection on the generated multiplex reference network. Each layer of the resulting multiplex network has common communities. The proposed model is first used to detect two-layer generative networks. The interlayer dependence tensor p is fixed to 1. In cases where nodes = 64 and nodes = 128, respectively, the value of the mixed parameter µ increases from 0.1 to 0.8. The NMI values corresponding to different µ values are shown in Figure 1. When the mixing parameter µ is closer to 0, the NMI value is closer to 1. The results show that the algorithm has good performance for community detection under certain conditions. As the µ value increases, the corresponding NMI in both cases decreases.

Figure 1.

When nodes = 64 and nodes = 128, respectively, (a,b) depict the NMI corresponding to different µ values with p = 1 and L = 2.

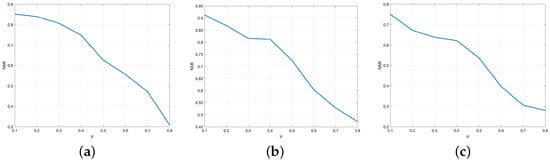

Figure 2 shows the variation trend of the corresponding NMI value with µ in the cases of three-layer, four-layer, and five-layer generation networks. In all three cases, the NMI values decrease significantly with the increase in µ value. This shows that the effect of the mixing parameter µ on the experimental results is independent of the number of layers in the generated network. The smaller the mixing parameter, the more obvious the community division in the generating network. Therefore, the model can detect the generated network with small mixing parameters better.

Figure 2.

The graphs in (a–c) depict the NMI corresponding to different µ values in three-layer, four-layer, and five-layer networks, with p = 1, nodes = 128.

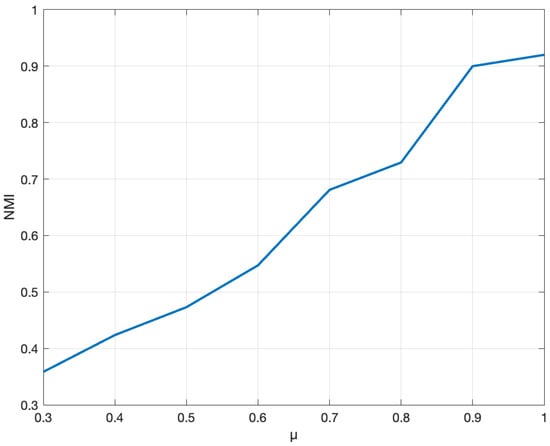

In order to investigate the impact of the interlayer dependency tensor on the detection outcomes, the number of produced network layers is kept at two. Then, the mixing parameter µ is set to 0.1, and the number of nodes is set to 64. The interlayer dependence tensor gradually increases from 0.3 to 1. The variation trend of the NMI value can be clearly seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

When µ = 0.1 and nodes = 64, NMI corresponds to different p values in 2-layer network.

In Figure 3, when the interlayer dependence tensor p is closer to 1, the corresponding NMI value becomes larger and larger. This shows that the interlayer dependency tensor controls the similarity of the common communities in different layers. The greater the interlayer dependence tensor, the higher the degree of community integration between different layers. In this case, the algorithm is more accurate in detecting the shared communities and exclusive communities in the multiplex network.

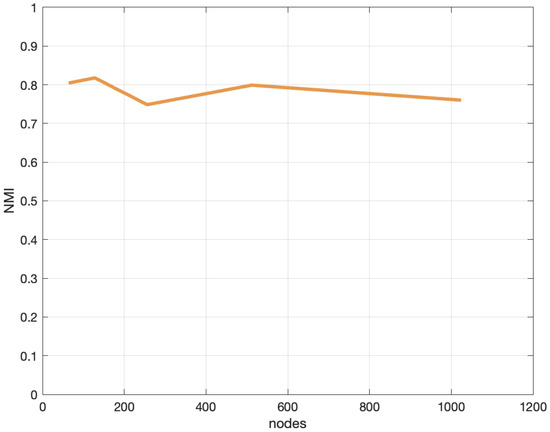

In Figure 4, the interlayer dependency tensor is fixed at 1. The mixing parameter µ of the generated network is set to 0.3. In the case of a three-layer network, the number of nodes is gradually increased. When the number of nodes in the generated network increases, the corresponding NMI value remains basically unchanged. The experimental results show that the number of nodes in the generated network has little effect on the detection performance of the model. Therefore, the proposed algorithm shows excellent performance in both small- and large-scale networks. For the Lazega Law Firm Multiplex Social Network, the partitions detected by the proposed algorithm have a good effect on each property. The proposed algorithm performs better than most algorithms in the detection of this network.

Figure 4.

When p = 1 and µ = 0.3, NMI corresponds to different values of nodes in 3-layer network.

In Table 3, the proposed algorithm outperforms other algorithms on both the Status and Wikipedia datasets. Under both the Gender and Law School datasets, the proposed algorithm performs second only to MX-ONMTF. On several other datasets, the proposed algorithm is unable to outperform the comparison algorithms. The GL model performs well on the 3sources and BBCSport datasets, while the CoReg model performs best on Seniority and Age. The experimental results show that no model performs optimally on several datasets at the same time. The AWP and MCGC models do not outperform other models on any of the datasets.

Table 3.

NMI values for datasets based on six models.

7. Conclusions

This study presents a multiplex network community discovery technique based on ONMTF. The suggested technique can identify shared and unique communities spread across many network tiers. An independence constraint and a graph regularity constraint are added to the original model. The results show that for synthetic networks and real-world networks, the algorithm can detect shared communities and exclusive communities with different layer community structures and performs well on some datasets. This is especially important for further exploring real networks with heterogeneity in cross-layer relationships.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y., S.Y. and B.P.; Methodology, Y.Y., S.Y. and C.L.; Software, Y.Y. and S.Y.; Validation, C.L. and M.-F.L.; Formal analysis, Y.Y., B.P. and C.L.; Investigation, Y.Y., S.Y. and B.P.; Resources, S.Y., B.P. and M.-F.L.; Writing—original draft, Y.Y., S.Y. and B.P.; Writing—review & editing, B.P., C.L. and M.-F.L.; Supervision, C.L. and M.-F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data from the experimental results are available from the first author. The author’s email address is y15572188780@163.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kivela, M.; Arenas, A.; Barthelemy, M.; Gleeson, J.P.; Moreno, Y.; Porter, M.A. Multilayer networks. J. Complex Netw. 2014, 2, 203–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlingerio, M.; Coscia, M.; Giannotti, F. Finding and characterizing communities in multidimensional networks. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining ASONAM 2011, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 25–27 July 2011; IEEE Computer Society: Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 490–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.Y.; Hero, A.O. Multilayer Spectral Graph Clustering via Convex Layer Aggregation: Theory and Algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:stat.ML/1708.02620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Frossard, P.; Vandergheynst, P.; Nefedov, N. Clustering on Multi-Layer Graphs via Subspace Analysis on Grassmann Manifolds. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2014, 62, 905–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuncheva, Z.; Montana, G. Community detection in multiplex networks using Locally Adaptive Random walks. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM 2015), Paris, France, 25–28 August 2015; pp. 1308–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Domenico, M.; Lancichinetti, A.; Arenas, A.; Rosvall, M. Identifying Modular Flows on Multilayer Networks Reveals Highly Overlapping Organization in Interconnected Systems. Phys. Rev. X 2015, 5, 011027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amelio, A.; Pizzuti, C. Community Detection in Multidimensional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 26th International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence, Limassol, Cyprus, 10–12 November 2014; pp. 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamfil, A.R.; Howison, S.D.; Lambiotte, R.; Porter, M.A. Relating modularity maximization and stochastic block models in multilayer networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:cs.SI/1804.01964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucha, P.J.; Richardson, T.; Macon, K.; Porter, M.A.; Onnela, J.P. Community Structure in Time-Dependent, Multiscale, and Multiplex Networks. Science 2010, 328, 876–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnani, M.; Hanteer, O.; Interdonato, R.; Rossi, L.; Tagarelli, A. Community Detection in Multiplex Networks. arXiv 2021, arXiv:cs.SI/1910.07646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Nie, F.; Huang, H.; Ding, C. Nonnegative Matrix Tri-factorization Based High-Order Co-clustering and Its Fast Implementation. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE 11th International Conference on Data Mining, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 11–14 December 2011; pp. 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.J.; Shen, H.; Gao, J.; Ouyang, W.; Cheng, X. A Non-negative Symmetric Encoder-Decoder Approach for Community Detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Singapore, 6–10 November 2017; pp. 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gligorijević, V.; Panagakis, Y.; Zafeiriou, S. Non-Negative Matrix Factorizations for Multiplex Network Analysis. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2019, 41, 928–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, J.; Choi, S. Orthogonal nonnegative matrix tri-factorization for co-clustering: Multiplicative updates on Stiefel manifolds. Inf. Process. Manag. 2010, 46, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; He, X.; Han, J.; Huang, T.S. Graph Regularized Nonnegative Matrix Factorization for Data Representation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2011, 33, 1548–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Zhang, C.; Fu, H.; Liu, S.; Zhang, H. Diversity-induced Multi-view Subspace Clustering. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, H.; Pan, B.; Leung, M.F.; Cao, Y.; Yan, Z. Tensor Factorization With Sparse and Graph Regularization for Fake News Detection on Social Networks. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2023, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Che, H.; Leung, M.F.; Liu, C.; Yan, Z. Robust multi-view non-negative matrix factorization with adaptive graph and diversity constraints. Inf. Sci. 2023, 634, 587–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Li, C.; Che, H. Nonconvex low-rank tensor approximation with graph and consistent regularizations for multi-view subspace learning. Neural Netw. 2023, 161, 638–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cozzo, E.; Kivelä, M.; Domenico, M.D.; Solé-Ribalta, A.; Arenas, A.; Gómez, S.; Porter, M.A.; Moreno, Y. Structure of triadic relations in multiplex networks. New J. Phys. 2015, 17, 073029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretton, A.; Bousquet, O.; Smola, A.; Schölkopf, B. Measuring Statistical Dependence with Hilbert-Schmidt Norms. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Algorithmic Learning Theory, Singapore, 8–11 October 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, C.; He, X.; Simon, H.D. On the Equivalence of Nonnegative Matrix Factorization and Spectral Clustering. In Proceedings of the 2005 SIAM International Conference on Data Mining (SDM), Newport Beach, CA, USA, 21–23 April 2005; pp. 606–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Che, H.; Leung, M.F.; Liu, C.; Yan, Z. Centric graph regularized log-norm sparse non-negative matrix factorization for multi-view clustering. Signal Process. 2024, 217, 109341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Kwong, S.; Zhou, Y.; Jia, Y.; Gao, W. Nonnegative matrix factorization with mixed hypergraph regularization for community detection. Inf. Sci. 2018, 435, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Sang, X.; Zhao, Q.; Lu, J. Community detection algorithm based on nonnegative matrix factorization and pairwise constraints. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2020, 545, 123491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.; Sun, J.; Xu, Z. Joint orthogonal symmetric non-negative matrix factorization for community detection in attribute network. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 283, 111192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith Aguilar, S.; Aureli, F.; Busia, L.; Schaffner, C.; Ramos-Fernandez, G. Using multiplex networks to capture the multidimensional nature of social structure. Primates 2018, 60, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Dong, D.; Wang, Q. Community Detection in Multi-Layer Networks Using Joint Nonnegative Matrix Factorization. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2019, 31, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sharoa, E.M.; Aviyente, S. Community Detection in Fully-Connected Multi-layer Networks Through Joint Nonnegative Matrix Factorization. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 43022–43043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Bouza, M.; Aviyente, S. Community Detection in Multiplex Networks Based on Orthogonal Nonnegative Matrix Tri-Factorization. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 6423–6436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazega, E. The Collegial Phenomenon: The Social Mechanisms of Cooperation Among Peers in a Corporate Law Partnership; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, D.; Cunningham, P. A Matrix Factorization Approach for Integrating Multiple Data Views. In Proceedings of the ECML PKDD 2009: Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases, Bled, Slovenia, 6–10 September 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rasiwasia, N.; Costa Pereira, J.; Coviello, E.; Doyle, G.; Lanckriet, G.R.; Levy, R.; Vasconcelos, N. A new approach to cross-modal multimedia retrieval. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Firenze, Italy, 25–29 October 2010; pp. 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzi, M.; Jeub, L.G.S.; Arenas, A.; Howison, S.D.; Porter, M.A. A framework for the construction of generative models for mesoscale structure in multilayer networks. Phys. Rev. Res. 2020, 2, 023100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, S.; Tackx, R.; Navelkar, A.; Guillaume, J.L.; Mitra, B. Discovering Community Structure in Multilayer Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA), Tokyo, Japan, 19–21 October 2017; pp. 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Rai, P.; Daumé, H. Co-regularized multi-view spectral clustering. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Granada, Spain, 13–15 December 2011; pp. 1413–1421. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, F.; Tian, L.; Li, X. Multiview Clustering via Adaptively Weighted Procrustes. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, London, UK, 19–23 August 2018; pp. 2022–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, K.; Nie, F.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y. Multiview Consensus Graph Clustering. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2019, 28, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).