Abstract

We study the square root computation by Leonardo Fibonacci (or Leonardo of Pisa) in his MSS Liber Abaci from c1202 and c1228 and De Practica Geometrie from c1220. In this MSS, Fibonacci systematically describes finding the integer part of the square root of an integer in numerous examples with three to seven decimal digits. The results of these examples are summarized in a table in the paper. Liber Abaci also describes in detail finding an approximation to the fractional part of the square root. However, in other examples in Liber Abaci and De Practica Geometrie, only the approximate values of the fractional part of the square roots are stated. This paper further explores these approximate values using techniques like reverse engineering. Contrary to many claims that Fibonacci also used other methods or approximations, we show that all examples can be explained using one digit-by-digit method to compute the integer part of the square root and one approximation scheme for the fractional part. Further, it is shown that the approximation scheme is tied to the method to compute the integer part of the square root.

Keywords:

history of algorithms; digit-by-digit; Cardano; Viéte; Heron; history of mathematics; computational science MSC:

01A35; 65-03; 68-03

1. Introduction

Leonardo Fibonacci or Leonardo of Pisa lived around 1170 to 1250. He was born in Italy, but educated in North Africa. He travelled widely in the Mediterranean until around 1200 when he settled in Pisa. He wrote several books of which copies of Liber Abaci from around 1202 with a second edition from around 1228, De Practica Geometrie from around 1220, Flos from around 1225, and Liber quadratorum from around 1225. The books Liber Abaci and De Practica Geometrie contain numerous examples computing the integer part of square root of natural numbers. Fibonacci consider 16 examples, five in Chapter 14 of Liber Abaci and 11 in Chapter 2 of De Practica Geometrie: The only example where the technique is expanded compared with the other 15 examples is finding the square root of 7234. For this example, Fibonacci multiplies 7243 with and finds the integer part of the square root of 7234 using the same technique as for the other examples. We find the spelling Liber Abbaci and Liber Abaci in the literature, though Abaci is used more often today [1] (p. 37).

The method used by Fibonacci to compute the integer part of the square root deviates from the technique later used by Cardano in 1539 [2] (Ch. 23) (see [3] and the references therein), Viéte in 1600 [4,5] or Horner in 1819 [6] where the number is divided in groups of two digits. Fibonacci is using a recursive technique where he assumes that only the last digit in the integer part of the square root needs to be determined [7]. So to determine the integer part , the technique assumes that the integer part of the square root ( is the floor function) and the residual are known. In his book on Liber Abaci, Lüneburg [8] (p. 258) writes “Hier wird man nun von Fibonacci wieder einmal überrascht. Er entwickelt nicht Schritt für Schritt vor unseren Augen den Tertianeralgorithmus (Algorithm taught in High School mathematics) zur berechnung von , vielmehr sagt Fibonacci, man solle gemäss den obigen Entwicklungen berechnen.” The recursive thinking is further evident in the example of in De Practica Geometrie where Fibonacci consider the root of a seven digit number but first finds the root of the first five digits. The method used by Fibonacci is not the Hindu method described by Datta and Singh [9] (p. 169–175) as claimed in [10] (p. 35) or the computational method of al-Nasawī (c. 1011–c. 1075) where is demonstrated [11]. In computing the integer part of the square root, a further misconception is that this is the Indian-Arabic algorithm [12]. It is a common misconception that Chapter 14 of Liber Abaci contains nothing significant not found in the Euclid’s Elements [13] (p. 10) [14] (p. 71). Early contributions to the History of Mathematics focus mainly on Fibonacci’s computation of the fractional part of the square root [15] (p. 30). The range of topics based on the works on Fibonacci is vast, ranging from recreational mathematics (see [14,16] and the references therein) to geometric constructions [17]. A comprehensive list is compiled by Charles K. Cook and Fibonacci Association [18].

It is common to regard computing the integer part of the square root and computing the fractional part as not dependent on each other. In the approximations, Fibonacci is not using a decimal fraction, but rely on fractions. It is shown that the actual implementation of computing the fractional part depends on the method used by Fibonacci to compute the integer part.

The remaining part of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we introduce the notation and the technique used by Fibonacci to compute the integer part of the square root and summarizes the results from [19]. Section 3 introduces Fibonacci’s computation of an approximation of the fractional part of the square root and summarizes the calculated examples from [19]. The first part of the next section contains examples computing the approximations of the fractional part of the square root from Liber Abaci and in the second part examples from De Practica Geometrie.

2. Integer Part of the Square Root

Let the decimal representation of a positive integer N be

where (not both equal 0). Since

the integer part of the square root of N has k digits. Partition N so that The integer part of will have digits and assume that the decimal representation of the integer part of is known

and put . The decimal representation of the integer part of N must then be

where is the next digit to be determined. Consider the remainder or residual using the binomial expansion

The will be largest integer in so that

Since is the largest integer that satisfies (2), the next integer in sequence will satisfy . Then

Since all terms on the left side of the inequality (3) are integers, we have

The last digit will be the smallest so that (4) holds. The left hand side of (4) is the remainder or residual (1) and the right hand side is twice the computed root. The two inequalities (2) and (4) uniquely determine the integer . A third inequality on is based on (2)

Approximations to this upper bound are

and

and

The upper bound and the approximations need not be calculated accurately, only the first digit in the fraction is needed. For the last example in De Practica Geometrie, Fibonacci is using (8), which uses even fewer decimal digits in the nominator and denominator than (6) and (7). Fibonacci’s method to compute the integer part of the square root is in a wider class of digit-by-digit methods. Contrary to methods often called evolution methods [20,21] which evolve one digit at the time, Fibonacci’s method is a (front-end) recursion.

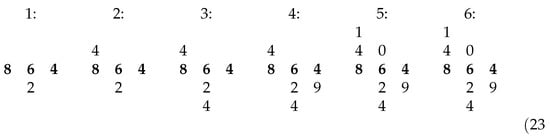

In Hughes’ translation of De Practica Geometrie [10] (p. 36), he demonstrates Fibonacci’s square root computation of in seven steps all based on the binomial expansion (1).

- 1:

- The root will be a two-digit number. The square of the first digit is immediately less than the first digit 8 () of N. So place 2 under the 6.

- 2:

- Subtract from 8 and put the remainder 4 () over the 8.

- 3:

- Double 2 and put it under 2.

- 4:

- An approximation to is (6), . Largest digit less than 11 is 9, probably the last digit of the root. Put 9 in the first place under 4.

- 5:

- Multiply 9 by 4 (under 2) and subtract 36 from 46 to obtain 10. Place 10 on the diagonal.

- 6:

- Square 9, subtract 81 from 104 (on the diagonal), to obtain the remainder 23.

- 7:

- The root is verified by showing that satisfies the second bound (4), i.e., that the remainder does not exceed twice the root found:

Hughes [10] (p. 36) illustrates Fibonacci’s computation with an evolution of Tables 1 to 6 in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Notation used in Hughes [10] to illustrate computing the square root of 864.

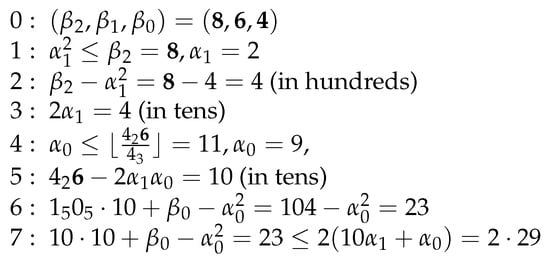

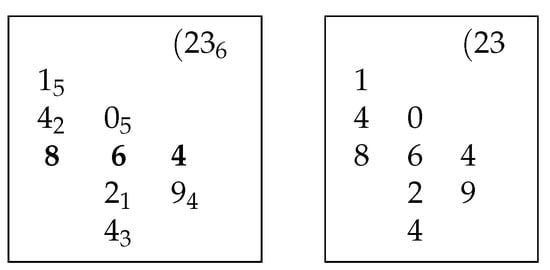

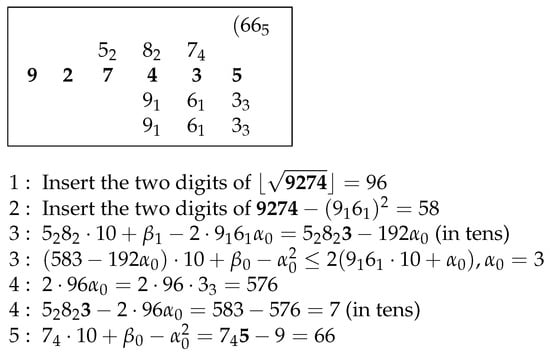

With the notation used in this paper, the corresponding computation is given in Figure 2 where the numbered lines correspond to the seven steps and to the tables in Figure 1. The subscripts where the digit is inserted in Figure 3 correspond to table in Figure 1 and line number in Figure 2. Note that is the number 46 (in tens) where 4 (in hundreds) is computed in line 2 and is the second digit in 864.

Figure 2.

The actual computation of .

Figure 3.

To the left, notation used in this paper, and [19,22] and to the right, illustration from MS [23] (Folie 12r).

The sequence of tables in Figure 1 can readily be reconstructed from the table in Figure 3. The table on the left in Figure 3 is first used by Ball [22].

The integer part of square root of 864 is 29 with remainder 23 which is marked as in Figure 1 and in Figure 3. Fibonacci’s computation of the remainder is just an rearrangement of the binomial expression for which is shown below.

Hughes [10] translates to English De Practica Geometrie in 2008 based on the transcript of Boncompagni from 1862 [24]. The following example from De Practica Geometrie of computing the integer part of is based on [10] (p. 39), via the use of Google translate from Latin of [24] (p. 19), and OpenAI. The blue inserted text in the quoted material below, [L:x] refers to line x in the table for the square root computation in Figure 2. The line number is the subscript in the table in Figure 3.

If you wish to find the root of 864,

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

- 5.

- 6.

More on notation:

- Boldface digits are the digits of the number to be taken square root of.

- In both editions of Liber Abaci the digits of the root are written two times to compute the sum, while in De Practica Geometrie the digits are multiplied by 2 (except the last digit of the root).

- Fibonacci calls the last digit (second digit) and the first digit.

2.1. Example Computing in Liber Abaci

The following emphasized text is based on the transcripts by Boncompagni [25] (p. 355) and Giusti [26] (p. 551), the translation by Sigler [13] (p. 492, 493).

To follow Fibonacci’s recursive thinking, we compute in Figure 4.Again if you wish to find the root of a six-digit number, as 927,435, which must have a root with three digits, …you therefore find the root of the number made of the last four digits, namely the 9274, and this you do according to that we demonstrated above in the finding of a root of a number of four digits.

Figure 4.

Use of Fibonacci’s method for .

The two successive inequalities in Figure 4 uniquely determine the last digit . In the example and and inequality (4) is used to determine the last digit in the integer part of square root of N. A reference [L:2] refers to line two (for the second number inserted in the table) in Figure 5 and [L:3.1] refers to the first of the lines marked 3:

Figure 5.

Fibonacci’s example for from Liber Abaci.

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

- 5.

2.2. Summary of Computing the Integer Part of the Square Root

Table 1 summarizes the finding in [19] and gives an overview of the different examples and the inequalities used to determine the last digit . The first column contains the number to be taken square root of, N, the second column contains a reduced number consisting of the digits of N except the two last digits, n, the third and fourth columns contain the integer part of the square root of the reduced number, a, and its remainder . The first five examples are from Liber Abaci, while the remaining eleven examples are from De Practica Geometrie.

Table 1.

Summary of the computation of the integer part of the square root.

3. Computing the Fractional Part

Let a be an approximation to the square root of positive integer N (not a perfect square) and let r be the residual . A common approximation is

The residual (or remainder) is a measure on how good the solution is. If the approximation is not sufficiently close to the solution, the iteration is repeated

We will say that is a correction to a and similarly, is a correction term to . In a digit-by-digit method, common choices are or . In the first case the residual r is positive, while in the other case the residual will be negative. In the calculated examples in Liber Abaci, Fibonacci chooses while other places in Liber Abaci and in De Practica Geometrie the choice is also used. The same iterates are generated by Heron’s method (also called the Babylonial method). Heron of Alexandra (active around 60 AD) computed the iterates as [29] (pp. 323, 324)

Further, from the equation defining

so the new residual is the negative of the square of the correction of a. The computation by Fibonacci is then given by

The term is twice the root found and is the sum of the two last rows in the tables in Liber Abaci and is on the last row in the tables in De Practica Geometrie (except the last digit) so the nominator and denominator for are computed. The computational procedure used by Fibonacci is very natural and makes the computation by hand very efficient.

In his work on approximation methods of Fibonacci, Glushkov 1976 [30] points out that (12) is used. However, without giving any examples. Cantor [15] shows the two approximations (12) and takes the example

Table 2 summarizes the worked out examples in Liber Abaci using the notation in the paper.

Table 2.

Computing the fractional part of the square root.

We observe that Fibonacci never uses three or more iterations and for the two first iterations results from the computation of the integer part are used.

Computing an approximation to deviates somewhat from the examples presented in Table 2. First is computed using the digit-by-digit method. Let and computed using the digit-by-digit method). The correction is . The approximation of is then and the approximation of is .

3.1. Other Examples of Square Root Computation in Liber Abaci

While the examples in Table 2 are worked out in details, other approximate fractions of square roots in Liber Abaci are just explicitly stated. There is no evidence that Fibonacci has used other than the two formulas (12) for computing an approximation of the fractional part of the square root. Three examples are given below.

- To show thatFibonacci first gives a geometric proof and then verifies the computation with approximate numbers [13] (p. 500). Fibonacci states that is a little less than , and that is a little less than Further, is a little less than . Thus he hasTo see the approximations observe , but is closer to 3 than 2.and is a little less than . ForFurtherso

- Fibonacci consider two ways to compute [13] (p. 503). First, what Fibonacci calls the common way, to observe that is a little less than , hence is a little less than . The second way, what Fibonacci calls the masterly way, is to observe that . The two last terms can be approximated and Fibonacci observes that is a little less than and that is about . The sum of the three terms is a little more than 33 and Fibonacci observes that is about .The approximations are for and is a little less than . First, observe and . For then is a little less than . The sum of the three terms 16, , and , is a little more than 33 and for which is a little larger than .A possible derivation of could be using (13) a little less than 16/5. For then and is a little less so will be a little less than and is a little less than . Another explanation is given by in Høyrup [31] (p. 28) which uses a little less than and for we have for that a little less than .

- To compute , Fibonacci again does this in two ways. Fibonacci states that is a little less than [13] (p. 504) and a little less than and the sum is the desired result. The way according to the art, writes Fibonacci, is to observe that which is shown geometrically. However, no approximation of is given.Let , and . For the next iteration then is a little less than .

There is no evidence that Fibonacci has used other than two formulas (12) for computing an approximation of the fractional part of the square root in Liber Abaci. Natural rounding in hand calculation like is needed to reproduce the results. Fibonacci also used (12) for rational N. The derivation and justification is a case of reverse engineering, in that no such derivation is in the source materials.

3.2. Fractional Square Root Computation in De Practica Geometrie

Fibonacci demonstrates in detail in Liber Abaci how to compute an approximation to the fractional part summarized in Table 2. These examples are not in De Practica Geometrie. However, in some cases there are explicit uses of (9) and (10). In De Practica Geometrie Fibonacci is also demonstrating square root of fractions. To compute (an approximation) of the square root of a fraction, multiply the fraction with a large number; the larger the number is, the more accurate solution. Let , and k be positive integers then

where k is large and q divides k.

More than 20 examples of approximation to the square root are given in De Practica Geometrie.

- Ref. [10] (p. 47, §18) [24] (p. 23): To compute in unit rods Fibonacci first converts to inches (1 rod is 6 feet and 1 foot is 18 inches)) and with remainder . The correction term computed by Fibonacci is and is (approximately) inches or 49 feet and inches which is or 8 rods, 1 foot and inches. Fibonacci is here computing in (12).

- Ref. [10] (p. 47, §20.2) [24] (p. 24): Compute in unit rods is with a remainder of 3. The correction term is in rods or foot. Fibonacci approximates this to 1 foot equal rod. The new approximation is then rods. The remainder is . The next correction is in rods or in unit inches or approximately 2 inches which is rods. New approximation to the square root is then with remainder . This is approximately in inches which is the approximation mentioned by Fibonacci. This approximate value will give the second correction . However, using the computed values gives the correction in incheswhich is the second correction in [24] (p. 24). The correction is in [10] (p. 47, §20.2) and in [24] (p. 24), [23] (Folie 14v), and [32] (Folie 20v).

- Ref. [10] (p. 48, §21) [24] (p. 24): To compute rods the integral part of the square root is with remainder . The first correction term is feet or rod. New approximation is with remainder . New correction is rods or inches. Fibonacci writes the fraction is too large so simply call it a little less and the approximation to the root is 10 rods, 3 feet, and inches. In [10] (p. 48, §21) it is 10 rods, 3 feet, and inches while in the transcription [24] (p. 24) the number of inches is .

- Ref. [10] (p. 48, §22): The exercise is to compute rods. The integral part of the square root is with a remainder of . Correction to be added to 35 is in inches. The approximation used is , but so Fibonacci writes use or , but this will decrease the accuracy.

- Ref. [10] (p. 52, §32): To compute take the square which is . Fibonacci states a little less than . To see this let then and the result is a little less than .

- Ref. [10] (p. 54, §37): To compute take the square which is . But from above example, is a little less than and the result is a close approximation.

- Ref. [10] (pp. 55, 56, §41): and from above is a little less than which must be divided by 60. Here, Fibonacci is using (13).

- Ref. [10] (p. 56, §41) in rods is inches. For then and the root is a little less than inches.

- Ref. [10] (p. 56, §41): Square root of 4/5 of one degree in seconds is . Then and a little less than 3220 so a little less than . Here Fibonacci is using (13). In his translation Hughes [10] (pp. 55, 56, §41) points out in a footnote that there is too much information in the transcribed version [24] (p. 30).

- Ref. [10] (p. 56, §42) [24] (p. 30): Find the number of feet of given in rods. (in rods) and (in feet) with remainder (in feet). The correction converted to inches isFibonacci states that the correction is 16. In a footnote this error is pointed out and the error invalidates the computation [10] (p. 56). However, the method used is the same as in the other cases. The new approximation by Fibonacci is therefore 4 feet and 16 inches or feet with remainder . The next correction will then be in feetor in inches which is the final given correction.

- Ref. [10] (p. 56, §42) [24] (p. 30): An alternative method to find the number of feet of given in rods is given in the same paragraph. Let and the correction is in feet or in inches. The approximation is then 5 feet minus inches or 4 feet and inches. In [10] (p. 56, §42) it is and in [24] (p. 30) it is .

- Ref. [10] (p. 72, §15) [24] (p. 34): To find the area of a triangle, Fibonacci gives that a little less than and approximately . Let and , then the correction will be and the approximation is a little less than . The next correction will be . It follows that is a little less than which is the result by Fibonacci. An alternative approach leading to the same result will be for and the correction is

- Ref. [10] (p. 86, §40) [24] (p. 43): It is stated that is a bit more than . Note that for and residual the correction is . Further is a little larger than the square root and is a little smaller than the root.

- Ref. [10] (p. 89, §47) [24] (p. 45): is a little more . For with residual , the correction is and the square root is a little larger than . The text [24] (p. 45) has , but context requires [10] (Footnote p. 89).

- Ref. [10] (p. 98,99, §66) [24] (p. 51) [23] (Folie 30v): To compute Fibonacci first computes to be approximately . Then approximately . Note that for then and the correction term is . The second correction term isFor , then and the first correction term is and the second correction will be

- Ref. [10] (p. 155, §194) [24] (p. 89) [23] (Folie 54r): Fibonacci states that (in rods) is 26 rods and inches. Let , then the correction will be which is in inches.

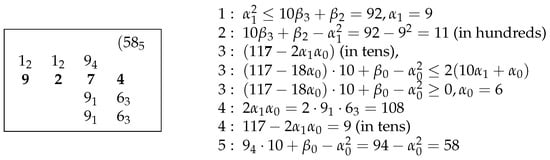

- Ref. [10] (p. 156, §196) [24] (p. 91): Fibonacci states that the square root of 3359 rods minus inches or is 58 rods minus inches. Let , the for the correction in inches is .

- Ref. [10] (p. 159, §203) [24] (p. 93): Fibonacci gives a little less than . Choose and . The correction term will be a little larger than so the new iterate will be a little less than the square root of N.

- Ref. [10] (p. 170, §233), [24] (p. 104), [32] (Folie 84r), and [23] (Folie 64r): Fibonacci gives approximately 20 rods 4 feet and inches. A possible derivation is . Then and the square root is a little less than rods. But rods is inches or 4 feet and inches or approximately inches.

- Ref. [10] (p. 172, §203): Fibonacci gives a little less than . Choose and . The correction term will be , so is a little larger than .

- Ref. [10] (p. 197, §16) [24] (p. 118): is a little less than . Let , and then the correction is .

- Ref. [10] (p. 293, §27) [24] (p. 169) [23] (Folie 107v): Fibonacci writes that is a bit more than but less than an additional and larger than an additional . To see the first part consider for the remainder will be and the correction iswhich added to will be an upper bound on the square root of 41,472. A lower bound will be with the addition of (and not ).

- Ref. [10] (p. 384, §28*) [24] (p. 222): A curiosity of this last example is the use of sexagesimal numbers. In the comments, Hughes questions whether this part is Fibonacci’s work or that of another [10] (p. 363). Further, there is some confusion on the actual numerical values. The integer part of the square root of is 1539 and the fractional part in sexagesimal digits is given as (in minutes, seconds and thirds) [24] (p. 222). The fractional part should have been , which is consistent with the remaining paragraph. The first time the integer and fraction appears in [32] (Folie 172v, 173r) and [23] (Folie 144r), it is written in the Arabic fashion which in modern notation is . The fractional part using sexagesimal digits is most likely computed using a digit-by-digit method for sexagesimal computation [33].

In the introduction to the translation of Chapter 2 in De Practica Geometrie, Hughes [10] (p. 37) suggests that Fibonacci might be using

for the square root. However, we do not find any indications of this. Some rounding of the final figures, like , or rounding in the first correction is needed to reproduce the results. We observe that in the second correction the nominator is most likely replaced by in some of the cases. Further, it is probably that Fibonacci used (9) and (10), and (12) also for rational N and a in De Practica Geometrie. However, such explicit use is not in the sources of De Practica Geometrie.

4. Concluding Remarks

In this paper we have shown that the verbal description of the method in computing the integer part of the square root of a natural number in Fibonacci’s Liber Abaci and De Practica Geometrie is the same for all worked out examples except for the approximation to the upper bound on the final digit in the root. Further, we show that computing the fractional part is uniquely described and uses the results from the computation of the integer part in the worked out examples in Liber Abaci. All other use of numerical approximations of the fractional part in Liber Abaci and De Practica Geometrie of the square root can be traced to the same method as described in Liber Abaci.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the anonymous referees for their helpful comments that improved the quality of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Drozdyuk, A.; Drozdyuk, D. Fibonacci, His Numbers and His Rabbits; Choven Publishing: Toronto, ON, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cardano, G. Practica Arithmetice, et Mensurandi Singularis; J.A. Castellioneus for B. Caluscus: Milan, Italy, 1539. [Google Scholar]

- Rivolo, M.; Simi, A. Il Calcolo delle Radici Quadrate e Cubiche in Italia da Fibonacci a Bombelli. Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 1998, 52, 161–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viète, F. De Numerosa Potestatum ad Exegesim Resolutione; Excudebat David Le Clerc: Paris, France, 1600. [Google Scholar]

- Viète, F. Opera Mathematica; van Schooten, F., Ed.; Elsevier: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1646. [Google Scholar]

- Horner, W.G. A new method of solving numerical equations of all orders, by continuous approximation. Philos. Trans. 1819, 109, 308–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüneburg, H. 1202–2002: Fibonacci’s Liber Abbaci. MAA Focus 2002, 22, 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lüneburg, H. Leonardi Pisani Liber Abbaci, oder Lesevergnügen eines Mathematikers, 2nd ed.; BI-Wissenschaftsverlag: Mannheim, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, B.; Singh, A.N. History of Hindu Mathematics I. Numeral Notation and Arithmetic; Motilal Banarsi Das: Lahore, Pakistan, 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, B. (Ed.) Fibonacci’s De Practica Geometrie; Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, H. Über das Rechenbuch des Ali ben Ahmed el-Nasawi. Bibl. Math. 1906, 7, 113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, K. Fibonacci, Leonardo, or Leonardo of Pisa. In Dictionary of Scientific Biography; Gillespie, C.C., Ed.; Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1971; Volume IV, pp. 604–613. [Google Scholar]

- Sigler, L. Fibonacci’s Liber Abaci: A Translation into Modern English of Leonardo Pisano’s Book of Calculation; Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, K. Recreational mathematics in Leonardo of Pisa’s LIBER ABBACI. In Proceedings of the Recreational Mathematics Colloquium II, Évora, Brazil, 27–30 April 2011; pp. 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Cantor, M. Vorlesungen über Geschichte der Mathematik, 2nd ed.; Zweiter Band; Teubner: Leibzig, Germany, 1900. [Google Scholar]

- Hannah, J. Conventions for recreational problems in Fibonacci’s Liber Abbaci. Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 2011, 65, 155–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldarola, F.; d’Atri, G.; Maiolo, M.; Pirillo, G. New algebraic and geometric constructs arising from Fibonacci numbers. Soft Comput. 2020, 24, 17497–17508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, C.K. Author and Title Index for The Fibonacci Quarterly. Fibonacci Q. 1993, 31, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Steihaug, T. Annotated square root computation in Liber Abaci and De Practica Geometrie by Fibonacci. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.12016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.D. Notices of the progress of the problem of evolution. In The Companion to the Almanac; Charles Knight & Co.: London, UK, 1839; pp. 34–52. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, A.T. Horner versus Holdred: An Episode in the History of Root Computation. Hist. Math. 1999, 26, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, N. Getting to the Root of the Problem: An Introduction to Fibonacci’s Method of Finding Square Roots of Integers. Lucerna. A Univ. Mo.-Kans. City Undergrad. Res. J. Present. Honor. Program 2010, 5, 53–71. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10355/8617 (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Fibonacci, L.P. Practica geometriae. MS. Urb. lat. 292, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Città del Vaticano, Sec. XV. Available online: https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Urb.lat.292 (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Boncompagni, B. Scritti di Leonardo Pisano, matematico del secolo decimoterzo. Leonardi Pisani Pr. Geom. Opuscoli 1862, 2, 1–224. [Google Scholar]

- Boncompagni, B. Scritti di Leonardo Pisano, matematico del secolo decimoterzo. Liber Abbaci Leonardo Pisano 1857, 1, 1–459. [Google Scholar]

- Giusti, E.; d’Alessandro, P. Leonardo Bigolli Pisani vulgo Fibonacci, Liber Abbaci; Olschki, L.S., Ed.; Biblioteca di Nuncius: Firenze, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fibonacci, L.P. Liber Abbaci. MS. BNCF, Magliabechiano XI.21, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, Firenze, Sec. XIV. Available online: https://archive.org/details/magliabechiano-xi.-21 (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Fibonacci, L.P. Incipit liber abaci compositus a Leonardo filio Bonacii Pisano in anno MCCII. MS. BNCF, Conventi Soppressi C.I.2616, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, Firenze, Sec. XIV. Available online: https://bibdig.museogalileo.it/tecanew/opera?bid=1072400 (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Heath, T. A History of Greek Mathematics; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1921; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Glushkov, S. On approximation methods of Leonardo Fibonacci. Hist. Math. 1976, 3, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Høyrup, J. Peeping into Fibonacci’s Study Room. Ganita Bharati 2021, 43, 1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Fibonacci, L.P. Practica geometriae. MS. Urb. lat. 259, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Città del Vaticano, Sec. XVII. Available online: https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Urb.lat.259 (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Steihaug, T. Fibonacci and Digit by Digit Computation; An Example of Reverse Engineering in Computational Mathematicsi. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).