Abstract

The linkable ring signature supporting stealth addresses (SALRS) is a recently proposed cryptographic primitive, which is designed to comprehensively address the soundness and privacy requirements associated with concealing the identities of both the payer and payee in cryptocurrency transactions. However, concerns regarding the scalability of SALRS have been underexplored. This becomes notably pertinent in intricate blockchain systems where multiple cryptographic primitives operate concurrently. To bridge this gap, our work revisited and formalized the ideal functionality of SALRS within the universal composability (UC) model. This encapsulates all correctness, soundness, and privacy considerations. Moreover, we established that the newly proposed UC-security property for SALRS is equivalent to the concurrent satisfaction of signer-unlinkability, signer-non-slanderability, signer-anonymity, and master-public-key-unlinkability. These properties represent the four crucial game-based security aspects of SALRS. This result ensures the ongoing security of previously presented SALRS constructions within the UC framework. It also underscores their adaptability for seamless integration with other UC-secure primitives in complex blockchain systems.

PACS:

J0101

MSC:

94A62

1. Introduction

In traditional cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin and Ethereum, the anonymity they provide is at a pseudonymous level. During transactions, it is not possible to link the wallet address to the real identity of the transactor. However, privacy-focused cryptocurrencies like Monero or Zcash demand the preservation of both payer and payee anonymity and unlinkability in transactions. In some of the blockchain systems, e.g., CryptoNote [1], linkable ring signatures (LRS) [2] and the key derivation mechanism (KeyDerM) [1] are employed to address the aforementioned goals of anonymity and unlinkability.

Specifically, when a payer intends to conduct a payment transaction with a payee, the payer first utilizes KeyDerM to derive a derived public key from the payee’s master public key as the receiving address for the transaction. As the payee’s master public key does not appear in the transaction, the recipient of this transaction, i.e., the payee, cannot be identified. KeyDerM is also known as the stealth address (SA) [3] mechanism. When the payee wishes to spend the currency associated with this derived public key, they need to select a ring of derived public keys during the transaction. This ring includes their own derived public key. Through this ring, a linkable ring signature is generated, allowing anyone to verify the validity of the signature without knowing the actual signer. The linkability aspect is also useful in detecting double-spending behavior by the signer, as two different signatures generated for the same derived public key will be linked.

Recently, there has been significant attention in the community on linkable ring signatures (LRS) and stealth addresses (SA) [4,5,6,7,8]. For instance, in projects like Monero [9] and CryptoNote [1], LRSs and KeyDerM are considered foundational constructs, but they are treated as separate entities without a unified security analysis, despite their tight coupling in usage. The existing literature [2,10,11,12] largely addresses LRSs or SAs individually, particularly in the context of standard signature schemes [4,8]. Moreover, the signature keys and public keys used in LRSs are generated by the SA mechanism, which means that the LRS mechanism used in the blockchain system does not independently generate keys. Further research is needed to explore the security and privacy aspects of key generation in SA. Whether the security and privacy models of linkable ring signatures and stealth addresses can be effectively applied in cryptocurrency scenarios requires thorough analysis by researchers. This is especially pertinent in the context of key selection attacks by adversaries, where existing linkable models either lack consideration for such attacks or fail to align with the practical use cases of cryptocurrencies.

In order to address the aforementioned issues, Liu et al. [13] proposed a new cryptographic primitive, namely the linkable ring signature supporting stealth addresses (SALRS). This scheme aims to fulfill the security and privacy requirements of concealing both the payer and the payee in cryptocurrency transactions. The security model of SALRS provides properties such as strong unforgeability, signer-linkability, and signer-non-slanderability. The privacy model ensures properties like signer-anonymity, master-public-key-unlinkability, and derived-public-key-unlinkability. All these properties can be concurrently defined in the SALRS model, aligning with the practical requirements of cryptocurrency scenarios, especially in the context of key selection attacks. Liu et al. [13] also introduced a lattice-based construction for SALRS and demonstrated its privacy and security under the random oracle model. However, there has not been dedicated research on the universal composability (UC) of SALRS to date. This section will analyze and study the UC security of SALRS, providing separate proofs for its security and privacy under UC security definitions. The conclusion drawn will affirm that SALRS satisfies UC security, enhancing its security and practicality in application scenarios like cryptocurrency.

1.1. Our Results

In this paper, we revisit the security definition of SALRS and explore its modularity and adaptability to other cryptographic primitives within a comprehensive cryptocurrency system. Our contributions can be summarized as follows.

- We provide a novel security definition of linkable ring signatures supporting stealth addresses (SALRS) in the universal composability (UC) framework. We define the ideal functionality, which simultaneously captures correctness, signer-linkability, signer-non-slanderability, signer-anonymity, and master-public-key-unlinkability. This is a more robust simulation-based security definition, implying that the protocol remains secure even when composed with arbitrary protocols.

- We further investigate the security level of the proposed security definition. Through rigorous analysis, we demonstrate that the proposed UC-security of SALRS is equivalent to the concurrent satisfaction of signer-linkability, signer-non-slanderability, signer-anonymity, and master-public-key unlinkability.

- We establish that the ideal functionality can be securely realized by the previously proposed construction that achieving the former four security definitions. This finding indicates that, including the SALRS construction proposed in [13], all secure SALRS constructions satisfy the security definition of [13], are UC-secure, and can arbitrarily compose with other UC-secure components in a complicated blockchain system.

1.2. Related Work

Before Liu et al. [13] gave the first practical quantum-resistant solution that hides the payers and payees of transactions in cryptocurrencies, there were several studies on linkable ring signatures [5,14,15,16], but none of them introduced stealth addresses. Without taking efficiency into account, [17,18] can also attain a logarithmic signature size concerning the number of signers in the ring. The constructions supporting stealth addresses [4,8] do not fulfill the criteria for linkable ring signature satisfaction.

While our work is the first to specifically address the UC-security of SALRS, it is worth noting that there have been various studies focusing on UC-secure signature schemes. Canetti [19] initially proposed a functionality for signature schemes, but a flaw in the definition made secure realization impossible. Subsequently, Backes et al. [20] and Canetti [21] addressed the flaw, establishing that the newly defined UC-security is equivalent to the game-based definition of EUF-CMA. In this paper, we employ a similar proven technique to circumvent the flaw identified in [19]. Apart from typical signature schemes, Abe et al. [22] introduced the UC-secure non-committing blind signature. Later, Hong et al. [23] formally defined the UC security of proxy re-signature. More recently, Zhu et al. [24] discussed the UC-security of the key-insulated and privacy-preserving signature scheme with publicly derived public key (PDPKS). While similar techniques are employed in defining the ideal functionality of digital signatures, it is crucial to emphasize that SALRS is distinct from these signature-related primitives, offering unique functionality and security features.

1.3. Outline

In Section 2, we show the syntax and security definitions of the primitive linkable ring signature with stealth addresses (SALRS), and preliminaries on the universal composability framework. In Section 3, we define the ideal functionality of SALRS, which captures its UC-security. In Section 4, we prove the existence of a UC-secure construction, by proving the equivalence between the game-based security [13] and the newly defined security. This paper is concluded in Section 5.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we begin by revisiting the definition of SALRS as proposed by Liu et al. [13]. Next, we review the background of the Universal Composability (UC) framework [19], as well as the definition of UC-security.

2.1. SALRS: Linkable Ring Signature Supporting Stealth Addresses

2.1.1. Syntax

An SALRS scheme [13] consists of the following eight algorithms:

- . Taking as input a security parameter , the algorithm outputs the system public parameter , which corresponds to the common parameters in the system.

- . Each user executes the master-key-generating algorithm to generate its master public–private key pair.

- . Anyone can execute the derived public-key-generating algorithm to generate a fresh derived public key from a master public key .

- . Taking as input a derived public key and a master public–private key pair , the owner of the master public key can execute the derived public key owner checking algorithm to obtain a bit , indicating whether a derived public key is a valid derived public key generated from its master public key .

- . Taking as input a derived public key , anyone can execute the derived-public-key-checking algorithm to obtain a bit , indicating whether the derived public key is well formed, so that it can use them as ring numbers for its ring signature generation.

- . Taking as input a message M, a ring of well-formed derived public keys , a derived public key , and its corresponding master public-private key pair , the key owner can execute the signing algorithm to generate a signature on the message M with respect to the ring R.

- . Taking as input a message M, a ring of well-formed derived public keys R, and a purported signature on the message M with respect to the ring R, anyone can execute the verifying algorithm to obtain a bit indicating the validity of the signature.

- . Taking as input two valid signatures and , anyone can execute the linking algorithm to obtain a bit indicating whether two signatures are linked or unlinked.

Remark 1.

We consider a public key ring R as an ordered set. Specifically, it is composed of a set of public keys, and during the execution of () and (), the public keys are arranged in a specific order, each assigned a unique index.

Remark 2.

We note that the nature of whether () is probabilistic or deterministic remains open, as it may vary depending on the specific constructions employed.

Correct. An SALRS scheme is correct if it satisfies the following property:

Let ,

- , , it holds that and .

- , any ring of well-formed derived public keys R, and s.t. for some master key pair , it holds that .

- , any well-formed derived public key rings , and , s.t. for some master key pairs , , it holds thatif , andif .

2.1.2. Security Models

Below, we provide the security definitions of SALRS, including soundness and privacy. Specifically, soundness encompasses unforgeability, signer-linkability, and signer-non-slanderability, while privacy includes signer-anonymity, master-public-key-unlinkability, and derived-public-key-unlinkability [13].

In more detail, unforgeability holds when only the user possessing the secret key for some public key in a ring can generate a valid signature with respect to that ring. Signer-linkability concerns the scenario where, with respect to a derived public key, if the key owner generates two or more valid signatures, these signatures will be identified as linked. This fulfills the security requirement of preventing double spending in cryptocurrencies. Signer-non-slanderability ensures that no one can falsely implicate other users by creating a signature linked to the signature of the target user.

For privacy requirements, signer-anonymity ensures that, given a valid signature for a ring of derived public key, it is infeasible for anyone to identify the signer’s derived public key within the ring. This property captures the privacy-preserving requirement of concealing the payer’s identity. Master-public-key-unlinkability ensures that, given a derived public key and its corresponding signatures, it is impossible to determine which master public key, from a known set of master public keys, was the origin of the derivation. Derived-public-key-unlinkability ensures that, given two derived public keys and their corresponding signatures, it is impossible to ascertain whether they are derived from the same master public key. This property ensures privacy by obscuring the link between payees in different transactions.

Particularly, Liu et al. [13] shows that unforgeability can be implied from signer-linkability and signer-non-slanderability together, and derived public-key-unlinkability can be implied from master public-key-unlinkability. We focus mainly on the remaining four properties in this paper. Formal definitions on the security properties are shown as follows.

Definition 1

(Signer-Linkability). For an SALRS scheme defined according to the specifications described above, for any PPT adversary , consider the following experiment :

- Setup Phase. is executed, where r represents the randomness used within (). acquires both and r.

- Output Phase. The adversary outputs a set of tuples , where .

The adversary succeeds if (1) , it holds that , (2) , and (3) .

The SALRS scheme is signer-linkable, if for any PPT adversary , there is a negligible function such that .

Definition 2

(Signer-Non-Slanderability). For an SALRS scheme defined according to the specifications described above, for any PPT adversary , consider the following experiment :

- 1.

- Setup Phase. is executed, where r represents the randomness used withinSetup(). acquires both and r.A set of master key generating algorithms are initiated, and the resulting set is presented to .An empty set, , is initialized, which serves the purpose of storing valid derived public keys derived from the target master public keys.

- 2.

- Probing Phase. The adversary can query the following two oracles adaptively:

- -

- Derived Public Key Adding Oracle :Taking as input a derived public key and a master public key , the adversary receives from this oracle a bit . If the response , update .

- -

- Signing Oracle :Taking as input a message , a ring of well-formed derived public keys R, and a derived public key , the adversary receives from this oracle a signature , where represents the master key pair for .

- 3.

- Output Phase. The adversary outputs two well-formed tuples, denoted as and .

Let be the query-answer tuples for . succeeds if (1) , (2) for some , (3) , and (4) .

The SALRS scheme is signer-non-slanderable if, for any PPT adversary , there is a negligible function such that .

Definition 3

(Signer-Anonymity). For an SALRS scheme defined according to the specifications described above, for any PPT adversary , consider the following experiment :

- Setup Phase. Same as the Setup phase in the experiment as defined in Definition 2.

- Probing Phase 1. Same as the Probing phase in the experiment as defined in Definition 2.

- Challenge Phase. The adversary outputs a message , a ring of well-formed derived public keys , and two indices , such that (1) , (2) , and (3) none of or were queried as input of .A challenge bit is selected; the adversary is provided with the signature , where represents the master key pair for .

- Probing Phase 2. Same as Probing Phase 1, with the added condition that none of or were queried as an input of .

- Output Phase. The adversary outputs a bit as its guess for b.

The advantage of the adversary winning is .

The SALRS scheme is signer-anonymous if, for any PPT adversary , there is a negligible function such that .

Definition 4

(Master-Public-Key-Unlinkability). For an SALRS scheme defined according to the specifications described above, for any PPT adversary , consider the following experiment :

- Setup Phase. Same as the Setup Phase in the experiment as defined in Definition 2.

- Probing Phase 1. Same as the Probing phase in the experiment as defined in Definition 2.

- Challenge Phase. The adversary outputs two indices , such that . A challenge bit is selected, and the adversary is provided with the derived public key . Update .

- Probing Phase 2. Same as Probing Phase 1, with the added condition that none of were queried as an input of .

- Output Phase. The adversary outputs a bit as its guess for b.

The advantage of the adversary winning is .

The SALRS scheme is master-public-key-unlinkable if, for any PPT adversary , there is a negligible function , such that .

With these comprehensive security and privacy models, SALRS effectively addresses the security- and privacy-preserving requirements essential in practical cryptocurrency scenarios. Notably, SALRS accommodates rings containing derived public keys that an adversary generated from their own master public keys. This realistic feature acknowledges situations where an attacker might create derived public keys from their master public keys, engaging in transactions among these keys with the intention of executing attacks, such as double spending or compromising the security and privacy of other users.

2.2. Universal Composability

We adopt the concept of universally composable security as defined by Canetti [19]. This framework offers a systematic approach to defining the security properties of cryptographic primitives, ensuring security is preserved under a general composition with an unbounded number of instances of arbitrary protocols running concurrently. Within this framework, all protocols operate in a specified computational environment in the presence of an adversary. The computational environment represents other protocols that may be concurrently executed alongside the protocol under consideration.

Given that communication is public, with no assurance of message delivery and is asynchronous without a guarantee of messages being delivered in order in the actual network, we presume that the communication between parties is authenticated. This authentication ensures that messages sent by honest parties will not be tampered with. We proceed by providing an overview of the model for protocol execution, known as the real-world model of computation. Subsequently, we introduce the ideal-world model of computation and present the general definition of security that realizes an ideal functionality.

In the real world, there exists an adversary A and a protocol that realizes a functionality among several parties. We denote the output of environment Z when interacting with adversary A and parties running protocol on a security parameter k, auxiliary input z, and random input , where each element represents the random tape used by the corresponding participant. We use the notation to represent this output. Additionally, let denote the random variable describing when r is uniformly chosen.

In the ideal world, there is a simulator S that simulates the real-life scenario, an ideal functionality F, and n dummy parties for the integrity of the simulation. Let denote the output of environment Z when interacting with adversary S and ideal functionality F on security parameter k, auxiliary input z, and random input , where each element represents the random tape used by the corresponding participants. Let denote the random variable describing when r is uniformly chosen.

The definition of universal composability is shown as follows.

Definition 5

(Universal Composability [19]). A protocol π UC-realizes a well-designed ideal functionality if, for any PPT adversary , the ensembles and are indistinguishable.

3. Security Model of SALRS in the UC Framework

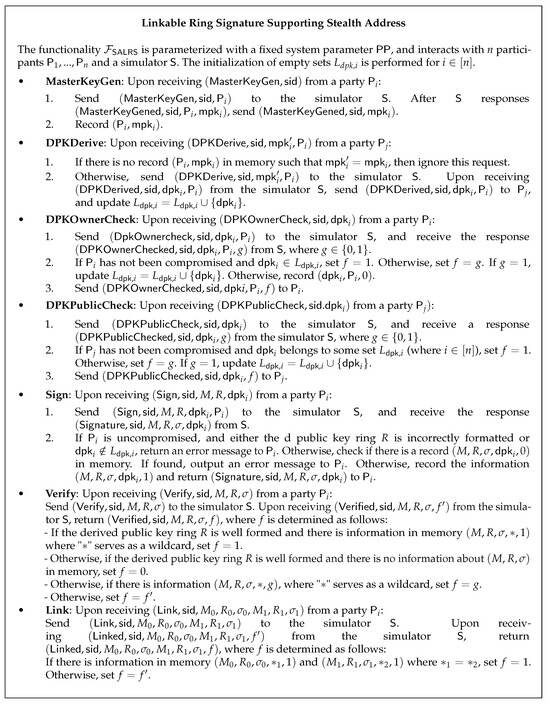

In this section, we aim to define the security model of SALRS in the universal composability model by introducing the newly designed ideal functionality . The definition of is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Ideal functionality of linkable ring signature supporting stealth addresses.

We assume that this ideal functionality operates under a fixed system parameter, hence the functionality interface. This omission eliminates the need for repetitive checks on the rationality of system parameters in subsequent interfaces.

Remark 3.

Our definition in the UC framework captures the correctness, soundness, and privacy of SALRS simultaneously. A formal proof establishing the existence of a UC-secure construction will be presented in Section 4.

4. A UC-Secure SALRS Construction

In this section, we prove that the UC-security of SALRS defined above in Section 3 is equivalent to satisfying signer-linkability, signer-non-slanderability, signer-anonymity, and master-public-key-unlinkability simultaneously.

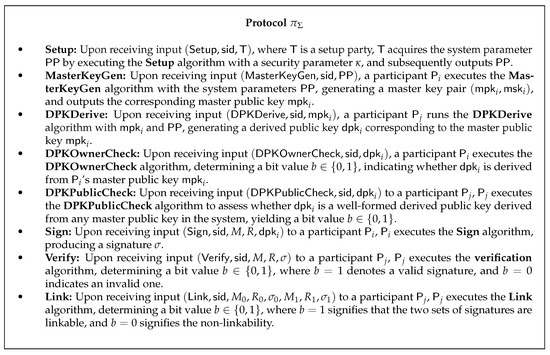

Let denote the SALRS scheme. The protocol is constructed from , shown in Figure 2. Similar to the ideal functionality , it shares identical interfaces with the environment .

Figure 2.

An SALRS protocol .

We establish equivalence by proving that a UC-secure SALRS scheme implies an SALRS scheme with signer-linkability, signer-non-slanderability, signer-anonymity, and master-public-key-unlinkability, and vice versa.

Lemma 1.

Let Σ be an SALRS scheme. If the corresponding protocol securely realizes the ideal functionality , then the SALRS scheme Σ satisfies signer-linkability (SN-LINK), signer-non-slanderability (SN-NSL), signer-anonymity (SN-ANO), and master-public-key-unlinkability (MPK-UNL) simultaneously.

Proof.

We prove this lemma by contradiction. In other words, if lacks signer-linkability, signer-non-slanderability, signer-anonymity, or master-public-key-unlinkability, then cannot UC-realize the ideal functionality .

Firstly, if lacks signer-linkability, there exists an adversary that can break the signer-linkability property of with a non-negligible advantage. In other words, there exists a PPT adversary , for any ideal world simulator , and an environment that, with the assistance of , can distinguish and with a non-negligible probability. The process of the environment is as follows:

- 1.

- activates the Setup Party with information , obtaining system parameters PP, and sends PP to adversary .

- 2.

- receives k (where ) tuples () from adversary , consisting of messages, well-formed derived public key rings, and signatures.

In step 2, because adversary can break the signer-linkability of , the k tuples received by satisfy the following conditions:

- 1.

- , where ;

- 2.

- ;

- 3.

- .

When executes in the real world, all these conditions can be verified. However, when executes in the ideal world, since the ideal functionality does not store relevant information, the first condition cannot be verified. Therefore, distinguishes between the real and ideal worlds, and the probability that distinguishes between the real and ideal worlds is equal to the probability that can break the signer-linkability. Hence, if does not satisfy signer-linkability, then cannot UC-realize .

Secondly, if lacks signer-non-slanderability, there exists an adversary that can break the signer-non-slanderability property of with a non-negligible advantage. In other words, there exists a PPT adversary , for any ideal-world simulator , and an environment that, with the assistance of G, can distinguish and with a non-negligible probability. The interaction process of the environment is as follows:

- 1.

- activates the setup party with information , obtaining system parameters PP, and sends PP to adversary .

- 2.

- When receives a query on the master public key of a participant from adversary , activates participant to obtain its master public key and sends it to . can inquire about the master public key of any participant.

- 3.

- When receives a query from adversary regarding whether a given derived public key is derived from a given master public key , activates participant to obtain the check result and sends it to .

- 4.

- When receives a signature query about from adversary , activates the owner of the derived public key to obtain the signature result and sends it to .

- 5.

- When receives two well-formed tuples and from adversary , where (1) can be verified by signature, (2) is the signature result of ’s query to about a derived public key , (3) is not the signature result of ’s query to about derived public key , and (4) these two tuples can pass the linkable verification, outputs 0 and halts. Otherwise, activates the party to return the linkable verification bit. obtains such tuples, and if is interacting with and in the real world, will output 1, since signature verification and linkable verification are valid. If is interacting with and in the ideal world, will output 0 because the ideal function does not record , so signature verification cannot pass, or records , but , so linkable verification cannot pass.

Since can break the signer-non-slanderability property of with a non-negligible probability, the probability that outputs 1 when interacting with the real model is also non-negligible. Therefore, can distinguish the interaction with the real model and the ideal model with a non-negligible probability. In other words, if lacks signer-non-slanderability, then cannot UC-realize .

Thirdly, if lacks signer-anonymity, there exists an adversary that can break the signer-anonymous property of with a non-negligible advantage. In other words, there exists a PPT adversary , for any ideal-world simulator S, and an environment that, with the assistance of , can distinguish and with a non-negligible probability. The interaction process of the environment is as follows:

- 1.

- Activate parties with the message to obtain individual master public keys .

- 2.

- Send to , and play the roles of oracle for adding derived public keys and the signing oracle . Initialize the empty set .

- 3.

- Receive a message , a well-formed derived public key ring , and two derived public keys and from , satisfying the following: (1) , and (2) neither or is queried before as an input by oracle .

- 4.

- Randomly choose a bit , run the algorithm to obtain the participant corresponding to the selected target derived public key , and activate this participant to obtain a signature , where is the master key pair corresponding to . Send this signature to .

- 5.

- Continue to play the roles of oracle and oracle for the adversary .

- 6.

- Receive from , output 1 if , otherwise output 0 and halt.

In step 2, adversary initiates queries , where query is one of the following:

- Oracle : receives a derived public key adding request concerning dpk and the master public key . sends a derived public key owner check request regarding this information to the participant corresponding to the master public key , obtaining the return value . If , update . Return the result b to .

- Oracle : receives a signature request concerning the message M, a well-formed derived public key ring R, and a derived public key . queries the owner of the derived public key dpk and activates the owner of the derived public key dpk with this signature request. receives the returned signature information , where is the master public–private key pair corresponding to dpk. Return the signature to .

These query requests may be adaptive, meaning that each query may be determined based on the answers to previous queries .

In step 5, adversary initiates more queries , where may be adaptively chosen as in step 2, except that and cannot be queried.

When interacts with and , in step 4 obtains a signature , and can break the signer-anonymity with a non-negligible advantage. When interacts with and , we use to denote the probability that outputs 1.

In contrast, when interacts with the ideal functionality and any adversary, the instance of ’s perspective is statistically independent of b. In this case, the probability that is exactly one-half. ’s perspective is independent of b; it includes all derived public-key-checking algorithms and signing algorithms. The randomly generated by is independent of b, and the oracle queries provided by are also independent of b.

When interacts with and the ideal functionality , we denote by the probability that outputs 1.

Therefore, the probability . Thus, can distinguish and with a non-negligible probability, proving that UC-secure SALRS implies signer-anonymity of SALRS.

Fourthly, if lacks master-public-key-unlinkability, there exists an adversary that can break the master-public-key-unlinkability property of with a non-negligible advantage. In other words, there exists a PPT adversary , for any ideal world simulator , and an environment that, with the assistance of , can distinguish and with a non-negligible probability. The interaction process of the environment is as follows:

- 1.

- Activate each participant with the message (), obtaining the master public keys for each participant, and send them to .

- 2.

- Play the roles of the oracle and a signature oracle for adversary during the interaction. Initialize an empty set .

- 3.

- sends two master public keys and to . randomly chooses a bit , selects an arbitrary participant , and activates with (), obtaining .

- 4.

- Send to as the target derived public key.

- 5.

- Continue playing the role of an oracle and a signature oracle for adversary during the interaction, except that queries where cannot be made.

- 6.

- outputs as the guess result. If , output 1; otherwise, output 0 and halt.

In step 2, adversary initiates queries , where query can be one of the following:

- Oracle : When receives a query from about whether a given derived public key dpk belongs to a certain master public key , sends this information to the participant corresponding to . When receives the result from participant , if , update . Submit the result b to .

These query requests may be adaptive, meaning that each query may depend on the responses to previous queries .

In step 5, adversary initiates additional queries , where may be adaptively chosen like in step 2, except for queries , where , cannot be made.

When interacts with and , in step 3, obtains . can break the master-public-key-unlinkability with a non-negligible advantage. When interacts with and , we use to denote the probability that outputs 1.

In contrast, when interacts with the ideal functionality and any adversary, the perspective of the instance is statistically independent of b. In this case, the probability that is exactly one-half. The derived public key generated by is independent of b, and the queries provided by are also independent of b. When interacts with and in the ideal world, let denote the probability that outputs 1.

Therefore, . Thus, can distinguish from with a non-negligible probability, demonstrating that UC-secure SALRS inherently implies the non-linkability of public keys in SALRS.

In conclusion, if UC-realizes , then satisfies the properties of signer-linkability, signer-non-slanderability, signer-anonymity, and master-public-key-unlinkability. □

Lemma 2.

If an SALRS scheme Σ satisfies signer-linkability, signer-non-slanderability, signer-anonymity, an d master-public-key-unlinkability simultaneously, the corresponding protocol securely realizes the ideal functionality .

Proof.

We establish the proof through a method of contradiction. In other words, if cannot UC-realize , then fails to satisfy at least one of the properties: signer-linkability, signer-non-slanderability, signer-anonymity, or master-public-key-unlinkability.

Firstly, we claim that if cannot UC-realize , while satisfying the other three properties, it can be deduced that does not satisfy signer-linkability. In more detail, we assume the existence of an adversary in the real world such that for any ideal world adversary , there exists an environment capable of distinguishing and . If this holds true, then there exists an adversary that simulates the simulator and the ideal functionality , using the environment to distinguish between the ideal and real world.

simulates the ideal adversary in the following manner: Firstly, obtains the public key of participant from .

- 1.

- Upon receiving input from the environment , forwards this input to and replicates ’s output as its own output.

- 2.

- Upon receiving from , first checks if . If not, it ignores this information; otherwise, it runs the algorithm to obtain a derived public key corresponding to .

- 3.

- Upon receiving from , queries the derived public key adding oracle to verify whether is derived from and returns the verification result .

- 4.

- Upon receiving from , runs the corresponding algorithm and returns the verification result.

- 5.

- Upon receiving from , queries the signature oracle to obtain a signature for the message M, the ring R, and the derived public key , and returns .

- 6.

- Upon receiving from , runs the verification algorithm to obtain a verification value f and returns .

- 7.

- Upon receiving from , runs the corresponding linking verification algorithm to obtain a verification value f and returns .

Clearly, in the above interaction, through querying oracles and invoking algorithms, the simulated and by are indistinguishable from the real and .

When the environment activates the participant with , verifies whether this information is linkable. If the linkability verification fails, and at the same time, can successfully verify the signatures for the tuples and while having queried the signature oracle about and , obtaining signatures and , where , then outputs and halts. In other words, has obtained a set of information that breaks the linkability of signers. Otherwise, continues the simulation.

If can obtain such a set of information, then for the input , if interacts with the real-world protocol , the observed output by is 1; if executes in the ideal world, observes an output of 0. In other words, can distinguish whether it is interacting with the ideal functionality or the implemented protocol . Therefore, if the probability of successfully breaking the signer-linkability is negligible, then the probability that the environment can distinguish between the real world and the ideal world is also negligible, contradicting the assumption.

Secondly, we claim that if cannot UC-realize , while satisfying the other three properties, it can be deduced that does not satisfy signer-non-slanderability. In more detail, we assume the existence of an adversary in the real world such that for any simulator , there exists an environment capable of distinguishing from . This assumption leads to the existence of an adversary that simulates the ideal world simulator and ideal functionality , attempting to distinguish between the ideal and the real world by interacting with the environment .

simulates the ideal adversary in the following manner: Firstly, obtains the public key of all participants from .

- 1.

- Upon receiving input from the environment , forwards this input to and replicates ’s output as its own output.

- 2.

- Upon receiving from , first checks if . If not, it ignores the message; otherwise, it runs the algorithm to obtain a derived public key corresponding to .

- 3.

- Upon receiving , queries the oracle to verify whether is derived from and returns the verification result.

- 4.

- Upon receiving , runs the corresponding algorithm and returns the verification result.

- 5.

- Upon receiving , queries the signing oracle to obtain the signature for the message M, context R, and derived public key , and returns .

- 6.

- Upon receiving , runs the signature verification algorithm to obtain the verification value f and returns .

- 7.

- Upon receiving , runs the corresponding linkability verification algorithm to obtain the verification value f and returns .

Clearly, in the above interaction, through querying oracles and invoking algorithms, the simulations of and by are indistinguishable from the actual and .

When the environment outputs two tuples and , these tuples satisfy the following conditions: (1) can be verified by signature verification; (2) is the signature result queried by regarding a certain derived public key ; (3) is not the signature result queried by regarding the derived public key ; (4) these two tuples can be successfully verified by the linkability verification. In this case, outputs this message pair and halts, indicating that has obtained a pair of messages that can defame the signer. Otherwise, continues the simulation.

If can obtain such a pair of messages that can defame the signer, then if interacts with and in the real world, the outputs observed by are 1 due to the effectiveness of signature verification and linkability verification. If interacts with and in the ideal world, signature verification cannot pass, since is not recorded in the ideal functionality . Therefore, observes an output of 0. Alternatively, if records , but ?, linkability verification cannot pass, and observes an output of 0. In this way, can distinguish whether it is interacting in the real or ideal world. Therefore, if the probability that can slander the signer is negligible, then the probability that can distinguish between the real and ideal worlds is also negligible, contradicting the assumption.

Thirdly, we claim that if cannot UC-realize , while satisfying the other three properties, it can be deduced that does not satisfy signer-anonymity. In other words, there exists an adversary , assisted by an environment , capable of breaking the signer-anonymity property of . To elaborate further, we assume the existence of an adversary in the real world such that for any adversary in the ideal world, there exists an environment capable of distinguishing from for any fixed security parameter and fixed input z:

We demonstrate that the adversary possesses an advantage in the signer-anonymity game, denoted as , where l is the total number of signed messages. The public keys of the participants are sent to and , allowing to make queries to the two mentioned oracles. conveys a message , and a correctly formatted derived public key ring to . simulates the operation of the environment similarly to the system running as follows.

- 1.

- Whenever participant is activated with input , instructs to return the corresponding derived public key. This is a perfect simulation, and at this step, cannot distinguish between and .

- 2.

- Whenever participant is activated with input , instructs to return the corresponding check result. This is a perfect simulation, and at this step, cannot distinguish between and .

- 3.

- Whenever participant is activated with input , instructs to return the corresponding check result. This is a perfect simulation, and at this step, cannot distinguish between and .

- 4.

- For the first instances, requests signatures on , where . instructs the signing party to return a signature , where is the public–private key pair corresponding to .

- 5.

- For the h-th instance, requests a signature on . randomly selects an honestly derived public key from the set and queries the oracle with information to obtain a signature in return. That is, during execution, when , ; when , .

- 6.

- For the remaining instances, requests signatures on , where . instructs the signing party to return a signature , where is the master public–private key pair corresponding to , and is the owner of .

- 7.

- Whenever participant is activated with input , instructs to output the execution result to . This is a perfect simulation, and at this step, cannot distinguish between and .

- 8.

- Whenever participant is activated with input , instructs to output the execution result to . This is a perfect simulation, and at this step, cannot distinguish between and .

- 9.

- When halts, outputs the output value of and halts.

We analyze the success probability of using the methodology of hybrid argument. For , let represent the event: interacts with in the ideal process, except that the first j signatures are generated by the truly derived public key rather than an arbitrarily chosen derived public key . Let be .

We easily observe that is equivalent to the probability of outputting 1 in the ideal world, and is equivalent to the probability of outputting 1 in the real world. Moreover, during the execution of , if obtains a value from its signing oracle that is generated by the actual derived public key , the probability of outputting 1 is equivalent to . If is generated from an arbitrarily chosen honest derived public key , the probability of outputting 1 is equivalent to . The detailed process is as follows:

Therefore, there exists some such that . Here, without loss of generality, we assume . Thus, the advantage of the adversary is as follows:

This implies that has a non-negligible advantage with respect to , as l is polynomially bounded in . Therefore, if the environment can distinguish between the real and ideal worlds, there exists an adversary that, under the help of the environment , breaks the signer-anonymity of .

Finally, we claim that if cannot UC-realize while satisfying the other three properties, it can be deduced that does not satisfy master-public-key-unlinkability. More specifically, we assume the existence of an adversary in the real world such that, for any ideal-world adversary , there exists an environmental machine , which can distinguish from for any fixed security parameter and fixed input z, as shown in Equation (3).

We demonstrate that the adversary exhibits an advantage in the game of master-public-key-unlinkability, denoted as , where l is the total number of generated target derived public keys. The public keys of participants, denoted as , are sent to both and , allowing to make queries to the aforementioned two oracles. simulates the environment in a manner analogous to the execution of .

- 1.

- For the first queries, requests participant to provide a derived public key related to , where . instructs to execute the corresponding algorithm and return .

- 2.

- For the h-th query, requests participant to provide a derived public key related to . randomly selects a public key such that and queries the oracle with the information to obtain the target derived public key . Subsequently, submits as the derived public key for . In other words, where or where .

- 3.

- For the remaining queries, requests participant to provide a derived public key related to , where . instructs to return .

- 4.

- Whenever participant is activated with the input , instructs to return the corresponding result f, where indicates that is linked to the public key of . Otherwise, queries the oracle about and receives the result value f, instructing to return this value to . This is a perfect simulation, and at this step, cannot distinguish between and .

- 5.

- Whenever participant is activated with the input , instructs to output the execution result and sends it to . Otherwise, queries the oracle with and , receiving the corresponding signature . instructs to return the information to . This is a perfect simulation, and at this step, cannot distinguish between and .

- 6.

- Whenever participant is activated with the input , instructs to output the execution result to . This is a perfect simulation, and at this step, cannot distinguish between and .

- 7.

- Whenever participant is activated with the input , instructs to output the execution result to . This is a perfect simulation, and at this step, cannot distinguish between and .

- 8.

- When halts, outputs the output value of and halts.

We analyze the success probability of using the methodology of hybrid argument. For , let represent the event: interacts with in the ideal world, except that the first j derived public keys are derived from the real master public key instead of . Let be .

We easily observe that is equivalent to the probability of outputting 1 in the ideal world, and is equivalent to the probability of outputting 1 in the real world. Moreover, during the execution of , if obtains the value from its derived public key oracle, where is derived from the genuine master public key , then the probability of outputting 1 is equivalent to . If is derived from the master public key , then the probability of outputting 1 is equivalent to . The detailed process is as follows:

Similar to the proof of signer-anonymity, there exists some such that . Here, without loss of generality, we assume . Thus, the advantage of the adversary is as follows:

This implies that has a non-negligible advantage with respect to , as l is polynomially bounded in . Therefore, if the environment can distinguish between the real and ideal worlds, there exists an adversary that, under the help of the environment , breaks the master-public-key-unlinkability of . □

Consequently, we arrive at the following theorem.

Theorem 1.

Let Σ be an SALRS scheme. The corresponding protocol securely realizes the ideal functionality if and only if the scheme Σ satisfies signer-linkability, signer-non-slanderability, signer-anonymity, and master-public-key-unlinkability simultaneously.

Proof.

The proof can be deduced from the preceding two lemmas. □

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we revisited and formalized the ideal functionality of the linkable ring signature supporting stealth addresses (SALRS) within the universal composability (UC) model, encapsulating all correctness, soundness, and privacy considerations. Furthermore, our research conclusively demonstrates that the newly introduced UC-security feature for SALRS aligns with the simultaneous fulfillment of essential game-based security properties: signer-unlinkability, signer-non-slanderability, signer-anonymity, and master-public-key-unlinkability. This finding not only safeguards the sustained security of pre-existing SALRS designs within the UC framework but also highlights their seamless integration capabilities with other UC-secure primitives in intricate blockchain systems. Future research may focus on providing security proofs for more cryptographic primitives in the UC model within the context of blockchain, thereby strengthening the overall security of the blockchain structure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W. and Z.L.; methodology, X.W., C.Z. and Z.L.; formal analysis, X.W.; writing—original draft preparation, X.W.; writing—review and editing, X.W. and Z.L.; supervision, Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62072305, 62132013).

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PPT | Probabilistic Polynomial Time |

| SALRS | Linkable Ring Signature Supporting Stealth Addresses |

| UC | Universal Composability |

References

- Van Saberhagen, N. CryptoNote v 2.0. 2013. Available online: https://www.bytecoin.org/old/whitepaper.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Liu, J.K.; Wei, V.K.; Wong, D.S. Linkable spontaneous anonymous group signature for ad hoc groups. In Proceedings of the Information Security and Privacy: 9th Australasian Conference, ACISP 2004, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 13–15 July 2004; Proceedings 9. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 325–335. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, P. Stealth Addresses. Bitcoin Development Mailing List. 6 January 2014. Available online: https://www.mail-archive.com/bitcoin-development@lists.sourceforge.net/msg03613.html (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Liu, Z.; Yang, G.; Wong, D.S.; Nguyen, K.; Wang, H. Key-insulated and privacy-preserving signature scheme with publicly derived public key. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P), Stockholm, Sweden, 17–19 June 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 215–230. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, C.; Lin, H.; Oechsner, S. Towards practical lattice-based one-time linkable ring signatures. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information and Communications Security, Lille, France, 29–31 October 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 303–322. [Google Scholar]

- Boyen, X.; Haines, T. Forward-secure linkable ring signatures from bilinear maps. Cryptography 2018, 2, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, P.; Mateus, P. A code-based linkable ring signature scheme. In Proceedings of the Provable Security: 12th International Conference, ProvSec 2018, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 25–28 October 2018; Proceedings 12. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 203–219. [Google Scholar]

- Courtois, N.T.; Mercer, R. Stealth address and key management techniques in blockchain systems. In Proceedings of the ICISSP 2017—3rd International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy, Porto, Portugal, 19–21 February 2017; pp. 559–566. [Google Scholar]

- Noether, S.; Mackenzie, A.; Monero Research Lab. Ring confidential transactions. Ledger 2016, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisaki, E. Sub-linear size traceable ring signatures without random oracles. IEICE Trans. Fundam. Electron. Commun. Comput. Sci. 2012, 95, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.K.; Au, M.H.; Susilo, W.; Zhou, J. Linkable ring signature with unconditional anonymity. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2013, 26, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, P.P.; Wei, V.K. Short linkable ring signatures for e-voting, e-cash and attestation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Security Practice and Experience, Singapore, 11–14 April 2005; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Nguyen, K.; Yang, G.; Wang, H.; Wong, D.S. A lattice-based linkable ring signature supporting stealth addresses. In Proceedings of the Computer Security—ESORICS 2019: 24th European Symposium on Research in Computer Security, Luxembourg, 23–27 September 2019; Proceedings, Part I 24. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 726–746. [Google Scholar]

- Alberto Torres, W.A.; Steinfeld, R.; Sakzad, A.; Liu, J.K.; Kuchta, V.; Bhattacharjee, N.; Au, M.H.; Cheng, J. Post-quantum one-time linkable ring signature and application to ring confidential transactions in blockchain (lattice RingCT v1. 0). In Proceedings of the Information Security and Privacy: 23rd Australasian Conference, ACISP 2018, Wollongong, NSW, Australia, 11–13 July 2018; Proceedings 23. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 558–576. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, F.; Tian, H.; Au, M.H. Anonymous post-quantum cryptocash. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Financial Cryptography and Data Security, Nieuwpoort, Curaçao, 26 February–2 March 2018; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 461–479. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Au, M.H.; Zhang, Z. Raptor: A practical lattice-based (linkable) ring signature. In Proceedings of the Applied Cryptography and Network Security: 17th International Conference, ACNS 2019, Bogota, Colombia, 5–7 June 2019; Proceedings 17. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 110–130. [Google Scholar]

- Libert, B.; Ling, S.; Nguyen, K.; Wang, H. Zero-knowledge arguments for lattice-based accumulators: Logarithmic-size ring signatures and group signatures without trapdoors. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT 2016: 35th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Vienna, Austria, 8–12 May 2016; Proceedings, Part II 35. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Esgin, M.F.; Steinfeld, R.; Sakzad, A.; Liu, J.K.; Liu, D. Short lattice-based one-out-of-many proofs and applications to ring signatures. In Proceedings of the Applied Cryptography and Network Security: 17th International Conference, ACNS 2019, Bogota, Colombia, 5–7 June 2019; Proceedings 17. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- Canetti, R. Universally composable security: A new paradigm for cryptographic protocols. In Proceedings of the 42nd IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, Newport Beach, CA, USA, 7 August 2002; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 136–145. [Google Scholar]

- Backes, M.; Hofheinz, D. How to break and repair a universally composable signature functionality. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Security, Palo Alto, CA, USA, 27–29 September 2004; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Canetti, R. Universally composable signature, certification, and authentication. In Proceedings of the 17th IEEE Computer Security Foundations Workshop, Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 30 June 2004; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 219–233. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, M.; Ohkubo, M. A framework for universally composable non-committing blind signatures. Int. J. Appl. Cryptogr. 2012, 2, 229–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Gao, J.; Pan, J.; Zhang, B. Universally composable secure proxy re-signature scheme with effective calculation. Clust. Comput. 2019, 22, 10075–10084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z. Universally Composable Key-Insulated and Privacy-Preserving Signature Scheme with Publicly Derived Public Key. In Proceedings of the Inscrypt 2023, HangZhou, China, 11–12 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).