Abstract

Connectivity plays an important role in measuring the fault tolerance of interconnection networks. As a special class of connectivity, m-component connectivity is a natural generalization of the traditional connectivity of graphs defined in terms of the minimum vertex cut. Moreover, it is a more advanced metric to assess the fault tolerance of a graph G. Let be a non-complete graph. A subset F is called an m-component cut of G, if is disconnected and has at least m components . The m-component connectivity of G, denoted by , is the cardinality of the minimum m-component cut. Let denote the n-dimensional leaf-sort graph. Since many structures do not exist in leaf-sort graphs, many of their properties have not been studied. In this paper, we show that is odd) and is even) for ; is odd) and is even) for .

MSC:

68R10; 05C40

1. Introduction

An interconnection network is usually modeled as an undirected graph, in which vertices and edges correspond to processor and communication links, respectively. Let be a graph with vertex set and edge set . As an application, graphs can also be used to study many issues related to interconnection networks [1,2]. For a graph G, the failure of vertices or edges is inevitable. In order to have an unimpeded interconnection network, we must think about the fault tolerance of a graph. There are many references focused on the fault tolerance of interconnection networks (see, for example [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]).

The connectivity of a graph is an important topology parameter in graph theory. The connectivity can be used to assess the vulnerability of corresponding networks, and is an important measurement for the reliability and fault tolerance of the network. A subgraph obtained from G by removing a set F of vertices and all associated incident edges is denoted by . In particular, F is called a vertex cut of a connected graph G, if becomes disconnected or has only one vertex. If F is a vertex cut of a graph G, then the biggst component of is called the big component. Furthermore, when G is not a complete graph, the traditional connectivity is defined to be the cardinality of a minimum vertex cut of G. By convention, the connectivity of a complete graph with n vertices is defined to be . A graph G is k-connected if .

However, traditional connectivity is not enough to evaluate the reliability of networks [11,12]. To further analyze the detailed situation of the disconnected graph caused by a vertex cut F, it is natural to generalize the traditional connectivity by introducing some conditions or restrictions on the vertex cut F and/or the components of . The notion concerning the number of components associated with the disconnected graph was first introducted by Chartrand et al. [13] and Sampathkumar [14]. Furthermore, in order to figure out how many sizes of a vertex cut can result in a disconnected graph with a certain number of components, Hsu et al. [15] proposed the definition of m-component connectivity. For a non-complete graph G, a subset F is called an m-component cut of G, if is disconnected and has at least m components . The m-component connectivity of G, denoted by , is the cardinality of the minimum m-component cut. By this definition, it is obvious that and for every positive integer m.

In recent years, the exact values of m-component connectivity have been studied for many graphs. For example, Hsu et al. [15] and Zhao et al. [16] studied the n-dimensional hypercube for and , respectively. Zhao and Yang studied the n-dimensional folded hypercube for and [17]. Zhang et al. [18] determined the -component connectivity of augmented cubes. In addition, the m-component connectivity has been studied for many graphs: alternating group networks [19,20], split-star networks [20], hierarchical star networks [21], balanced hypercube [22], bubble-sort star graphs, and burnt pancake graphs [23]. However, most of these results are related to and . For , there are a few results. Furthermore, it is worth noting that some scholars have studied the relationship between m-component connectivity and m-extra connectivity [24,25,26]. The m-extra connectivity, denoted by , is defined as the minimum number of vertices whose removal from G results in every component in having at least vertices [27].

In this paper, we study the m-component connectivity of leaf-sort graphs, which will be defined later in Section 2. Although this graph has been proposed for a long time, many properties related to it have not been studied due to its unique structure. The biggest feature of leaf-sort graphs is as follows: let , if n is odd, u has two outgoing neighbors in other subgraphs; if n is even, u only has one outgoing neighbor in other subgraphs (Proposition 2 in Section 2). Due to this special feature, many structures which exist in other graphs do not exist in leaf-sort graphs. This leads to many difficulties when studying this graph. Meanwhile, there are some conclusions about leaf-sort graphs [28,29]. It is worth noting that there are many scholars working on the domination number of a graph [30], which is a very interesting research topic, and we can try to do more research in this direction.

The remaining part of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the definition of and gives some properties of . In Section 3, we first prove that the following conclusion is true: when n is odd, ; when n is even, is an . Then, we get the exact value of . In Section 4, we prove certain structures do not exist in leaf-sort graphs firstly, and then get the exact value of . Section 5 concludes this paper.

2. Preliminaries

Let be a simple connected graph, where is the vertex set and is the edge set. For a vertex , is the set of neighbors of v. Let be the degree of v and be the minimum degree of G. If for every , then G is k-regular. A singleton of G is a vertex v with . For a vertex set X, is the neighbor of X. The distance between any two vertices u and v, denoted by , is the length of the shortest path from u to v. G is bipartite if there exist two vertex subsets with such that and for each edge , . It is well known that bipartite graphs contain no odd cycles. We use Bondy and Murty [31] for terminology and notation not defined here.

2.1. Definition of Leaf-Sort Graphs

Let , be two integers with . Set as an integer with . In the permutation , . For convenience, we denote the permutation by . In [32], every permutation can be denoted by a product of disjoint cycles. For example, . In particular, . The product of two permutations is the composition function followed by , e.g., . Let be the symmetric group on containing all permutations of . It is well known that is a generating set for . So (n is odd) is also a generating set for and (n is even) is also a generating set for . For terminology and notation not defined here, we follow [32]. Now, we give the definition of n-dimensional leaf-sort graphs .

Definition 1

([29]). The n-dimensional leaf-sort graph is a graph with vertex set in which two vertices are adjacent if and only if , or when j is even and n is odd, or when j and n are even.

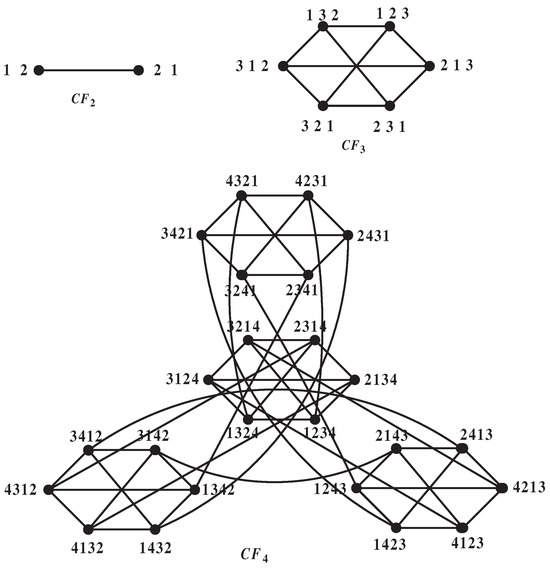

By definition, we can obtain as a -regular graph on vertices for odd n, and -regular graph on vertices for even n. The graphs , and are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The leaf-sort graphs , and .

2.2. Structural Properties of

We can partition into n subgraphs , where every vertex has a fixed integer i in the last position for . It is obvious that is isomorphic to for [29]. The edges’ end vertices in different are called cross-edges. Two edges are said to be independent if they do not share the same vertex. For with , we denote by the set of edges between and . For each vertex , two vertices adjacent to u via out-edges are called the outgoing neighbors of u, and are denoted by , . Let .

Proposition 1

([29]). Let be defined as above. Then, there are independent cross-edges between two different when n is odd; there are independent cross-edges between two different when n is even.

Proposition 2

([29]). Let , which is defined as above. Then, and belong to two different ’s when n is odd; belong to when n is even.

Proposition 3.

For any , when n is odd; when n is even.

Proof.

Let and , where for some . Then, , . Moreover, and . Hence, when n is odd, ; when n is even, . □

Proposition 4

([29]). For any integer , is bipartite.

Proposition 5.

For any two vertices , .

Proof.

If or , then ; otherwise, (i.e., ) there will be a 3-circle or , a contradiction. So we only consider the situation: . Next, we prove this result by induction on n.

For , as and .

For , if , as and . If , , let and , we know . If or , then . Thus, .

Now, we assume and the result holds for . If for , then by Proposition 3 and the inductive hypothesis, the result holds. So we let , , , . Then, , , , . We know and since , and . As and , we can assume .

When n is odd. If , then , . Thus, and , , . So . If and adjacent to x, then , . Thus, . Furthermore, holds if and only if ; this is similar to the situation . When , . So when n is odd, this result holds.

When n is even, note that . If or , then . Thus, .

In summary, this proposition is proven. □

Corollary 1.

When is even, if x and y belong to two different subgraphs in , then .

Corollary 2.

When is odd, for any two vertices , where , . Then, holds if and only if or .

Proposition 6

([29]). Let be the leaf-sort graph. Then, the connectivity when n is odd and when n is even.

Lemma 1

([28]). Let with when n is odd and when n is even . If is disconnected, then satisfies one of the following conditions:

has two components, one of which is a singleton;

has three components, two of which are singletons.

The conclusion of Lemma 1 is closely related to the m-component connectivity of , which is why we listed it here.

3. The 3-Component Connectivity of

In this section, we will discuss the 3-component connectivity of , and will prove that, when n is odd, for ; when n is even, for . Before proving our main results, we prove some useful lemmas firstly. Let S be a subset of (i.e., ; S is called an independent set if any two vertices are nonadjacent.

Lemma 2.

When n is odd, if , then there exists only vertices in , which can satisfy that ; when n is even, if , then there exists only vertices in such that . In addition, these vertices are all regular.

Proof.

Note that . When n is odd, is even, . Since , by Corollary 1 we know that must belong to a common subgraph in ; otherwise, if belong to different subgraphs in , then . So we can assume , . Now, we let , , then , , is odd. Since , by the proof process of Proposition 5, we now have two different situations:

Case 1.

belong to two different subgraphs in , and or .

In this case, we have . If , then ,…,. Thus, . If , then . Thus, .

Case 2.

belong to the same subgraph in .

In this case, we have , , . As , is even, , we can obtain belonging to a common subgraph in . Then, . Let , , then , and . As is odd, there are two different situations:

Subcase 2.1.

belong to two different subgraphs in , and or .

If , we can get . Thus, . If , then . Thus, .

Subcase 2.2.

belong to a same subgraph in .

This case is similar to case 2; this is a finite cycle process.

Finally, when n is odd, we can obtain vertices such that , they are , , , ,…,, .

When n is even, is odd, . Let , , . Assume , , then , ; similarly, we can also divide it into two different situations:

Case 1.

belong to two different subgraphs in , and or .

In this case, we have . If , then . Thus, . If , then . Thus, .

Case 2.

belong to a same subgraph in .

In this case, . Since and , and are in a same subgraph in . So . Let , , then , , is odd. As , we can also consider the following two situations:

Subcase 2.1.

and belong to two different subgraphs in , and or .

If , then . Thus . If , then . Thus .

Subcase 2.2.

and belong to a same subgraph in .

This case is similar to case 2; this is also a finite cycle process.

Finally, when n is even, we can obtain vertices such that , they are , , , ,…, , . □

Corollary 3.

Let is an n-dimension leaf-sort graph, . If , and , then .

Lemma 3.

For , let S is an -set and , then when n is odd, ; when n is even, .

Proof.

Let , as S is an -set, so and are nonadjacent. By Proposition 5 and the definition of , we know that and is a -regular graph is odd) or -regular graph is even). So, when n is odd, . When n is even, . □

Corollary 4.

For , let F be a subset of (i.e., ) and when n is odd, ; when n is even, , then contains a big component C, which satisfies .

Theorem 1.

For , when n is odd, ; when n is even, .

Proof.

For , since , we can obtain by Proposition 6. For , by Corollary 4, we can also obtain when n is odd and when n is even. Next, we will prove that, when n is odd, and when n is even, . Since , we can choose two different vertices , such that . From the definition of , we know that is a -regular is odd) and -regular graph is even), so when n is odd, ; when n is even, . Let ; we know contains three components and two of them only have a singleton. So we can obtain is odd) and is even). □

4. The 4-Component Connectivity of

Lemma 4.

When , let S be an -set and , .

Proof.

Let ; since S is an -set, are nonadjacent with each other. Note that , . Next, we will think about the following three cases.

Case 1.

belong to the same subgraph .

In this case, since and S is an -set, . By Proposition 3, we know the outgoing neighbors of are different. Thus, .

Case 2.

belong to two different subgraphs , .

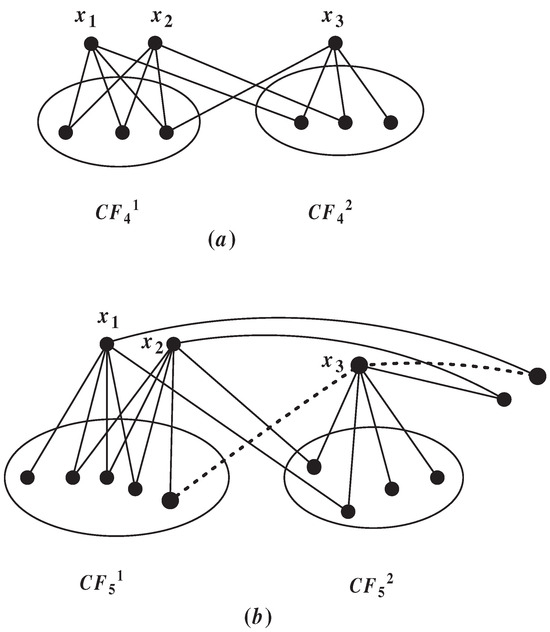

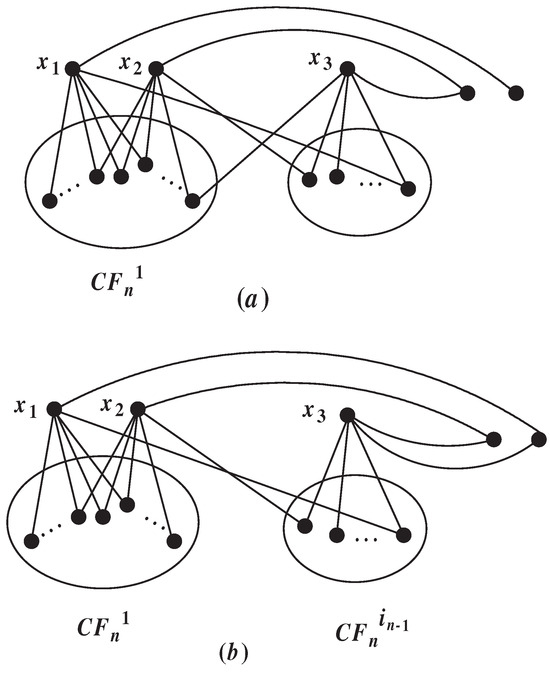

In this case, we can let , . Since and are nonadjacent, we can obtain , . By the definition of , we know only has one outgoing neighbor. If the structure shown in Figure 2a exists, . Now, we can show that this structure does not exist. As and , we assume , then or . Thus, , , and the structure shown in Figure 2a does not exist. Thus, .

Figure 2.

(a) is an illustration of in Lemma 4 and (b) is an illustration of Case 2 in Lemma 5.

Case 3.

belong to three different subgraphs , , are different from each other).

In this case, we can let . By the definition of , we know , thus .

Combining the above three situations, we can obtain . □

Lemma 5.

When , let S be an -set and , .

Proof.

Let , since S is an -set, are nonadjacent with each other. Note that . We think about the following three cases.

Case 1.

belong to the same subgraph .

Since , by Lemma 4, we can obtain . By the definition of and Proposition 3, we know the outgoing neighbors of are different and every vertex has two different outgoing neighbors. Thus, .

Case 2.

belong to two different subgraphs , .

In this case, we can let , . Since , by Lemma 3, we know that . By the definition of , we can obtain . By Proposition 2, we can ascertain that and have, at most, two neighbors which belong to . In other words, there are at least two neighbors of and belonging to . If the structure shown in Figure 2b exists, then . Furthermore, holds if and only if this structure exists. Now, we can prove this structure does not exist.

Since and , by Lemma 2, we can ascertain whether , or are different from each other).

If , then , . Since , and one of the two outgoing neighbors of belong to , we can obtain . Thus, . As are adjacent to , so or or . When , , , and is adjacent to . Since , , , . Thus, this structure does not exist. When , , , and is adjacent to . Since , and , , . When , , , and is adjacent to . Since , and , , . So this structure does not exist.

If , then , . Since , and one of the two outgoing neighbors of belong to , we can obtain . Thus, . As are adjacent to , so or or . As discussed above, we can also conclude that this structure does not exist.

Thus, the structure shown in Figure 2b does not exist, .

Case 3.

belong to three different subgraphs , , are different from each other).

Without loss of generality, we can let , , . By the definition of , we can obtain , thus .

Combining the above three situations, we can obtain . □

Lemma 6.

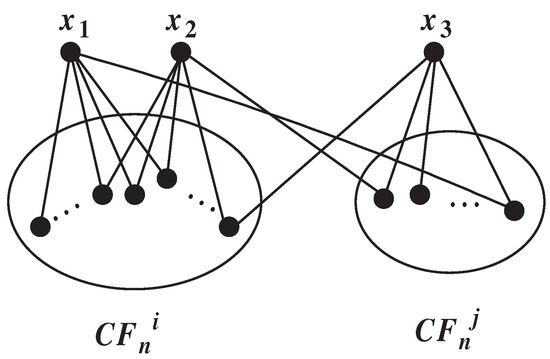

When n is odd, let be an -set, where , and . Then, .

Proof.

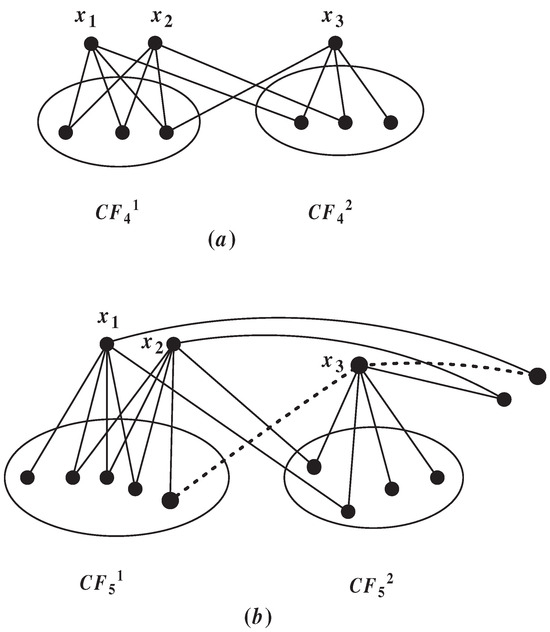

When n is odd, occurs if and only if the structure in Figure 3 appears. Next, we will prove that these structures cannot appear.

Figure 3.

(a,b) are the two cases of in Lemma 6.

Firstly, we prove that the structure shown in Figure 3a does not exist. Suppose, on the contrary, we assume this structure exists and , then , . As , by the proof process of Lemma 3, we can know that must have three common neighbors in . Note that n is odd, then is even, and . By Corollary 1, we can ascertain that must belong to a common subgraph in ; otherwise, if belongs to two different subgraphs in , then , which is a contradiction. So , , , , . By Corollary 3, we know . As one of the two outgoing neighbors of and belong to a common subgraph with , and . Now, we assume . As one of the two outgoing neighbors of belongs to , or . When , , . In this situation, , , since , we have , . Thus, this structure does not exist. When , as are adjacent to , we can obtain , ; this contradicts the fact that , thus this structure does not exist.

Lemma 7.

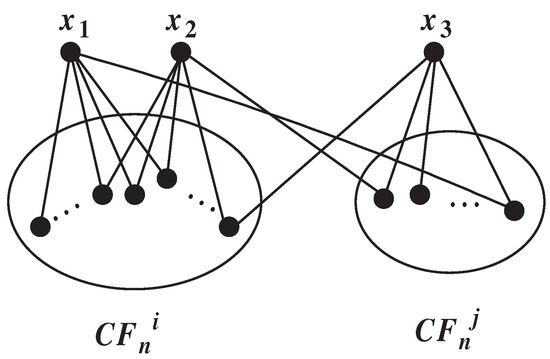

When n is even, let be an -set, where , and . Then, .

Proof.

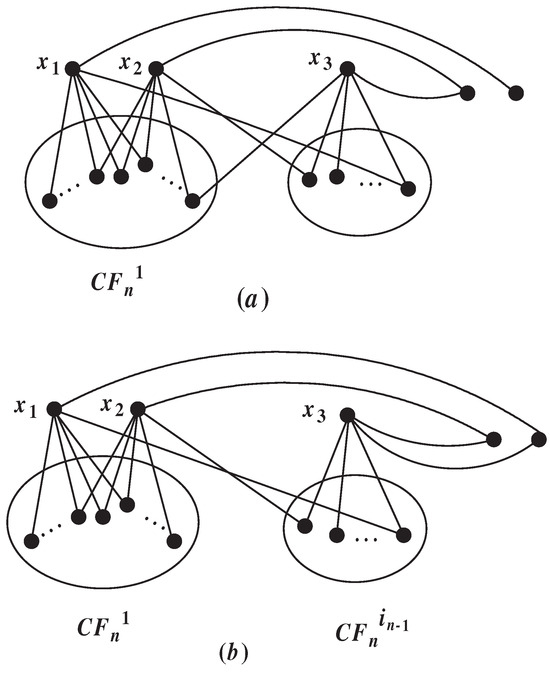

When n is even, occurs if and only if the structure in Figure 4 appears. Next, we will prove that this structure does not exist. Note that ; is odd.

Figure 4.

The case of in Lemma 7.

Suppose, on the contrary, we assume this structure exists; as , we know must have three common neighbors in by Lemma 3. Now, we let , . By Corollary 3, we know and . Thus, , , and can not belong to a common subgraph in ; this contradicts this structure. Thus, . □

Lemma 8.

When , let S be an -set and , then when n is odd, ; when n is even, .

Proof.

Let ; since S is an -set, are nonadjacent to each other. We prove this result by induction on n. By Lemmas 4 and 5, we know when , this result holds. Now, we assume that and the result holds for . Note that . Next, we think about the following three cases:

Case 1.

belong to a same subgraph .

When n is odd, by the induction hypothesis, we have . By Proposition 3 and the definition of , we know the neighbors of in are different and every vertex has two outgoing neighbors. Thus, .

When n is even, by the induction hypothesis, we have . By Proposition 3 and the definition of , we know the neighbors of in are different and every vertex has only one outgoing neighbor. Thus, .

Case 2.

belong to two different subgraphs , .

In this case, we can let , . By Lemma 3, we can obtain the following: when n is odd, ; when n is even, . By the definition of , we know that, when n is odd, ; when n is even, . When n is odd, by Proposition 2, we know that, at most, two outgoing neighbors can belong to ; in other words, there are at least two outgoing neighbors of that can belong to . So . By Lemma 6, we know , thus . When n is even, if the structure of Figure 4 exists, then . By Lemma 7, we know this structure does not exist, so .

Case 3.

belong to three different subgraphs , , are different from each other).

Without loss of generality, we can let , , . By Proposition 6, we have, when n is odd, ; when n is even, . Thus, when n is odd, ; when n is even, .

Thus, the result holds. □

Corollary 5.

When n is even, let be an -set, if , then belong to the same subgraph in .

Lemma 9.

For , if , then contains a big component C, which satisfies the result . In other words, satisfies one of the following conditions: has two components, one of which is a singleton or an edge; has three components, two of which are singletons.

Proof.

We are not going to think about being connected for the moment, so we assume that is disconnected. Let for with , where . If , then and is connected. By Proposition 2, we know every vertex in has an neighbor in . So is connected, which is a contradiction. Hence, we consider . Since , we have , , , , . Firstly, we prove the following claim is correct. □

Claim 1.

If for some , then is connected.

Proof of Claim 1.

By Proposition 6, we can ascertain that is connected for each . On the other hand, as , we can obtain , which implies for . Hence, is connected.

Since , by Claim 1, we can ascertain that is connected. If and are all connected, we know is connected. As , is connected. As , we establish that is connected. Since is disconnected, at least one of is disconnected, which leads to the following two cases.

Note that, if , by Proposition 3, we can ascertain that has a big component and, at most, one vertices, which has a neighbor in . Thus, if or is connected, then satisfies the condition . If and are all disconnected, then satisfies the condition . Hence, we only think about this situation: .

Case 1.

Both and are disconnected.

In this case, we know . Since , . Hence, , . By Corollary 4, we know has a big component and a singleton . By Lemma 1, should consider the following two situations: has two components, one of which is a singleton. has three components, two of which are singletons. For , let be the big component and be the singleton of ; since and , by Proposition 3, we can ascertain that is connected. Similarly, we can also ascertain that is connected. Thus, the result holds. For , let be the big component and , be singletons of . If is nonadjacent to , then are three singletons in . By Lemma 5, we can obtain ; this contradicts the fact that . If is adjacent to , say , then only has two components; otherwise, we let have three components, then is a singleton in . By Proposition 5, we have , which is a contradiction. Thus, the result holds.

Case 2.

Only is disconnected.

Since , . As is disconnected, we have and then . If , then , , which is a contradiction. Thus, . Since , is connected. As , by Corollary 4, we know has a big component S and, at most, one singleton. By the same argument as that of Case 1, we can ascertain that is connected. Then, must satisfy condition .

Case 3.

Only is disconnected.

By Proposition 6, we have . Since and , . As , we can see that is connected.

If , by Lemma 1, has a big component S and one single and two singletons. By the same argument as that of Case 1, we can see that is connected. Then, must be one of conditions and .

Now, we suppose . Then, . Let W be the union of components of , whose vertices, which are totally contained in , are not connected with . By Propositions 2 and 3, we know , which implies . Thus, satisfies or .

Combining the above three cases, we know this result holds. □

Lemma 10.

For , if , then contains a big component C, which satisfies the result . In other words, satisfies one of the following conditions: has two components, one of which is a singleton or an edge; has three components, two of which are singletons.

Proof.

Similarly, we do not think about the situation being connected, so we let be disconnected. Let for with , where . If , then and is connected. By Proposition 2, we can ascertain that is connected. So we assume . Since , we have , , , , , . Firstly, we prove the following claim is correct. □

Claim 2.

If , then is connected.

Proof of Claim 2.

By Proposition 6, we know is connected for each . On the other hand, since for , we can obtain . Thus, is connected.

By Claim 2, we know is connected. If both and are connected, we can establish that is connected, which is a contradiction. Thus, at least one of is disconnected, which leads to the following cases.

Case 1.

Both and are disconnected.

In this case, we know . By Corollary 4, we know that has a big component and one singleton . As , thus is connected. Similarly, we can see that is also connected. Thus, the result holds.

Case 2.

Only is disconnected.

As is disconnected, we have and then . Since , is connected. Since , by Corollary 4, has a big component C and one singleton. Since , we can ascertain that is connected. Then, must be one of the conditions .

Case 3.

Only is disconnected.

In this case, , . As , we can see that is connected.

If , by Lemma 9, has a big component C with . By the same argument as that of Case 2, we can see that is connected. Thus, the result holds.

If , then . Let W be the union of components of , whose vertices, which are totally contained in , and are not connected with . By Propositions 2 and 3, we have . Thus, the result holds. □

Lemma 11.

Let for odd n and for even n, then contains a big component C, which satisfies that . In other words, satisfies one of the following conditions: has two components, one of which is a singleton or an edge; has three components, two of which are singletons.

Proof.

By Lemmas 9 and 10, the result holds for . We prove this result by induction on n. Assume and that the result holds for . Now, we suppose is disconnected for any with or . Let for with , where .

When n is odd, if , then and is connected; thus, by Proposition 2, we can establish that is connected. Now, we assume ; when n is even, if , then and is connected, and thus, by Proposition 2, we can see that is connected. Now, we assume . □

Claim 3.

When n is even, if , then is connected; when n is odd, if , then is connected.

Proof of Claim 3.

By Proposition 6, we know is connected for each . On the other hand, since for is even) and for is odd), we can obtain . Thus, is connected.

Since is even) and is odd), we have for even n and for odd n. By Claim 3, we can ascertain that is connected. If and are all connected, as is even) and is odd), then is connected. Similarly, we can also see that is connected. So, at least one of is disconnected, which leads to the following cases.

Note that, when n is odd, if , by the same argument of Lemma 9, we know satisfies condition or . Hence, we assume that .

Case 1.

Both and are disconnected.

When n is even, we have . By Corollary 4, we know and all have a big component and one singleton. As , . Thus, is connected and the result holds.

When n is odd, we have . So, by Lemma 1, we would consider the following three subcases: both and have three components, two of which are singletons; only one of and has three components, two of which are singletons; and both and have two components, one of which is a singleton. Now, we just prove the first subcase and the other two subcases can be proved by the same argument. Let (resp., ) be the two singletons and the other big component of (resp., ). Since and , by Proposition 3, we know is connected. Similarly, we can ascertain that is connected.

If are four singletons in , then by Proposition 5, we know , which is a contradiction.

If has three singletons, then by Lemma 8, we can obtain ; this contradicts the fact that . So, has two singletons or only one singleton. □

Claim 4.

If has at least one edge, say , then only has two components.

Proof of Claim 4.

Suppose has at least three components. Then, is a singleton or . If is a singleton, then , which is a contradiction. If , then , which is a contradiction.

- Thus, by Claim 4, the result holds.

Case 2.

Only is disconnected.

As is disconnected, we have for even n and for odd n, then is even) and is odd). Since is even) and is odd), is connected. Since , when n is even, by Corollary 4, we know has a big component C and one singleton; when n is odd, by Lemma 1, we know has a big component C and at most two singletons. By the same argument as that of Case 1, we can establish that is connected. Then, must be one of conditions and .

Case 3.

Only is disconnected.

In this case, for even n and for odd n. As is even) and is odd), we know that is connected.

When n is even, if , by introduction, we know has a big component C with . By the same argument as that of Case 1, we can establish that is connected. Thus, the result holds. If , then . Let W be the union of components of , whose vertices are totally contained in and are not connected with . By Propositions 2 and 3, we have . Thus, the result holds.

When n is odd, if , by introduction, has a big component C with . By the same argument as that of Case 1, we can see that is connected. Thus, the result holds. If , then . Let W be the union of components of , whose vertices are totally contained in and are not connected with . By Proposition 3, . Then, we have . Thus, the result holds. □

Theorem 2.

For , when n is odd, ; when n is even, .

Proof.

By Lemma 1, we have . For , by Lemma 11, we can obtain, when n is odd, ; when n is even, . Next, we will prove that and . For , if we let , then has three singletons: . Thus, . For , when n is odd, let , where , , , then and there are three singletons in . Thus when n is odd, . When n is even, let , where , , , then and . As belong to a common subgraph, by Proposition 3, we know have different outgoing neighbors. So, and are three singletons in . Thus, when n is even, . □

5. Conclusions

It is very useful to study the connectivity of a graph. In this paper, we study the m-component connectivity of . The leaf-sort graph is a special Cayley graph that has many special properties. We have shown that, for , is odd) and is even); for , is odd) and is even). So far, we only obtained the value of , ; for , this problem is still unsolved. Therefore, we can seriously think about whether we can use a similar method to study on this basis. Furthermore, by referring to the references, we can find that there is a regularity between and . Similarly, and also have regularity. So, we can think about whether there some sort of relationship between and .

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L. and S.W.; investigation, H.L. and L.Z.; methodology, H.L.; writing—original draft, H.L.; writing and editing, H.L.; reviewing the results, H.L. and L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (61772010), the Shanxi Provincial Fundamental Research Program of China (202203021221128) and the Shanxi Province Graduate Research Innovation Project (2023KY429).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hayat, S.; Khan, S.; Khan, A.; Imran, M. A Computer-based Method to Determine Predictive Potential of Distance-Spectral Descriptors for Measuring the π-electronic Energy of Benzenoid Hydrocarbons With Applications. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 19238–19253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Hayat, S.; Zhong, Y.; Arif, A.; Zada, L.; Fang, M. Computational and topological properties of neural networks by means of graph-theoretic parameters. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 66, 957–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, J. Fault-tolerance of (n, k)-star networks. Appl. Math. Comput. 2014, 248, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Liu, H.; Lu, M. Fault-tolerant maximal local-connectivity on bubble-sort star graphs. Discret. Appl. Math. 2015, 181, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, S.; Khan, A.; Zhong, Y. On Resolvability- and Domination-Related Parameters of Complete Multipartite Graphs. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Hao, R. The fault tolerance of (n, k)-bubble-sort networks. Discret. Appl. Math. 2020, 285, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, S.; Khan, A.; Malik, M.Y.H.; Imran, M.; Siddiqui, M.K. Fault-Tolerant Metric Dimension of Interconnection Networks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 145435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Xu, M. Edge-fault-tolerant strong Menger edge connectivity on the class of hypercube-like networks. Discret. Appl. Math. 2019, 125, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsen, G. On the reliability of modified bubble-sort graphs. Trans. Combiatorics 2021, 11, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Hayat, S.; Siddiqui, H.M.A.; Imran, M.; Ikhlaq, H.M.; Cao, J. On the zero forcing number and propagation time of oriented graphs. AIMS Math. 2021, 6, 1833–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.; Li, P.; Xu, M. The component (edge) connectivity of shuffle-cubes. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2020, 835, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennayake, K.P. Generalized Edge Connectivity in Graphs; West Virginia University: Morgantown, WV, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chartrand, G.; Kapoor, S.F.; Lesniak, L.; Lick, D.R. Generalized connectivity in graphs. Bull. Bombay Math. Colloq. 1984, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sampathkumar, E. Connectivity of a graph-a generalization. J. Comb. Inf. Syst. Sci. 1984, 9, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, L.; Cheng, E.; Liptók, L.; Tan, J.J.M.; Lin, C.; Ho, T. Component connectivity of the hypercubes. Int. J. Comput. Math. 2012, 89, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Yang, W.; Zhang, S. Component connectivity of hypercubes. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2016, 640, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Yang, W. Conditional connectivity of folded hypercubes. Discret. Appl. Math. 2019, 257, 388–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhou, S.; Cheng, E. Component connectivity of augmented cubes. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2023, 952, 113784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Pai, K.; Wu, R.; Yang, J. The 4-component connectivity of alternating group networks. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2019, 766, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Hao, R.; Chang, J. Measuring the vulnerability of alternating group graphs and split-star networks in terms of component connectivity. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 97745–97759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Chang, J.; Hao, R. On component connectivity of hierarchical star networks. Int. J. Found. Comput. Sci. 2020, 31, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Chang, J.; Hao, R. On computing component (edge) connectivities of balanced hypercubes. Comput. J. 2020, 63, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Hao, R.; Tang, S.; Chang, J. Analysis on component connectivity of bubble-sort star graphs and burnt pancake graphs. Discret. Appl. Math. 2020, 279, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lin, C.; Fan, J.; Jia, X.; Cheng, B.; Zhou, J. Relationship between extra connectivity and component connectivity in networks. Comput. J. 2021, 64, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, R.; Gu, M. Jouming Chang, Relationship between extra edge connectivity and component edge connectivity for regular graphs. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2020, 833, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Zhang, M.; Zhai, S.; Xu, L. Relation of Extra Edge Connectivity and Component Edge Connectivity for Regular Networks. Int. J. Found. Comput. Sci. 2021, 32, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fóbrega, J.; Fiol, M.A. On the extraconnectivity of graphs. Discret. Math. 1996, 15, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, S. Connectivity and Nature Diagnosability of Leaf-sort graphs. J. Interconnect. Netw. 2020, 20, 2050011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Y. Mujiangshan Wang, Connectivity and matching preclusion for leaf-sort graphs. J. Interconnect. Netw. 2019, 19, 1940007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.; Hayat, S.; Jamil, H. The domination number of the king’s graph. Comput. Appl. Math. 2023, 42, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondy, J.A.; Murty, U.S.R. Graph Theory; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hungerford, T.W. Algebra; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).