Abstract

In this paper, we consider the numerical solution of a large complex linear system with a saddle-point form obtained by the discretization of the time-harmonic eddy-current optimal control problem. A new Schur complement is proposed for this algebraic system, extending it to both the block-triangular preconditioner and the structured preconditioner. A theoretical analysis proves that the eigenvalues of block-triangular and structured preconditioned matrices are located in the interval [1/2, 1]. Numerical simulations show that two new preconditioners coupled with a Krylov subspace acceleration have good feasibility and effectiveness and are superior to some existing efficient algorithms.

MSC:

65F08; 65F10

1. Introduction

The mathematical theory of optimal control has rapidly evolved over the last few decades into an important and distinct field of applied mathematics, as shown in [1]. J. L. Lions was the first to propose partial differential equation (PDE)-constrained optimization [2,3]. Eddy-current problems are a unique kind of electromagnetic field problem that appear in computational electromagnetism when at least one of the electromagnetic fields is changing very slowly over time. It is an application of Maxwell’s equations, which appears in many practical situations, such as in the numerical modeling of transformers, relays and electric motors [1,4].

We focus on the solution method of the complex-valued linear system obtained after the discretization of the time-harmonic eddy-current optimal control problem by the finite element method (FEM). At present, the main methods for solving large-scale linear systems are iterative methods and preconditioners. In 2001, Golub et al. extended the SOR iterative method to the generalized saddle-point problem and proposed the SOR-like method [5]. In 2002, Benzi et al. extended the HSS iterative method to the saddle-point problem [6,7]. Since then, numerous iterative solutions have emerged based on the HSS iterative method [8,9,10,11,12].

Because the coefficient matrix of the discrete linear equations has a special structure, the efficiency of the Krylov subspace method can be improved by constructing efficient preconditioners. In 2013, Krendl et al. [13] proposed a block diagonal preconditioner to accelerate the MINRES method. In 2016, Zheng and Zhang et al. [14] introduced a parameter on this basis and proposed a generalized block-diagonal preconditioner. In 2018, Liang et al. [15] proposed an efficient structured preconditioner to accelerate the GMRES method. In 2021, Liang et al. [16] proposed an exact complex decomposition technique of the Schur complement to accelerate the GMRES method [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. In 2022, Luo et al. [30] proposed two new block preconditioners and for solving saddle-point problems. In 2023, Luo et al. [31] used the block preconditioner for solving general block two-by-two linear systems by expanding the dimensions of the coefficient matrix.

We propose a new Schur complement based on [13,16] to obtain a new block-triangular preconditioner and a new structured preconditioner and theoretically prove the eigenvalue distribution interval of their preconditioned matrices. Numerical simulation results show that and exhibit stable numerical performance. When compared with the block-diagonal preconditioner and the algorithm EI-GMRES, the two newly proposed preconditioners can reduce iteration time and steps.

The paper is structured as follows. We introduce the background of the problem in Section 1. Some details and discretization processes of eddy-current problems are introduced in Section 2. We summarize the existing preconditioner and propose two new preconditioners and in Section 3. The algorithm of is derived, and the eigenvalue interval of its preconditioned matrix is proved in Section 4. The algorithm of is derived, and the eigenvalue interval of its preconditioned matrix is proved in Section 5. Numerical results of the preconditioners and are presented and discussed in Section 6. We summarize the work and look to the future in Section 7.

2. Eddy Current Problem

The problem originates from the magneto quasi-static model, which is the application of Maxwell’s equations in slowly changing electric fields [17,18]. We consider the following linearized eddy-current problem: find a time-varying magnetic vector potential such that

where is the space-time cylinder, and is its extracellular surface, . is a bounded region in with a Lipschitz continuous boundary , and is the outer normal vector of . j denotes the impressed current density, denotes the electrical conductivity, and v denotes the magnetic reluctivity. The time-harmonic field is an important type of time-varying electromagnetic field, whose solution is a sine function of a single frequency. According to [19], the following problem is considered: find the state and the control to minimize the cost function

subject to the time-harmonic problem

where is a function of the given target. is a regularization parameter, and is an extra regularization parameter, but in some cases, can be chosen. The conductivity is a constant, and the magnetic reluctivity is consistently positive and independent of .

In Ref. [20], it is deduced and proved that the vector-potential formulation method is used to solve the time-harmonic eddy-current optimal control problem. The external current density is a harmonic relation with time in alternating currents. According to the special case of a linear material law, we obtain a time-harmonic expression of the target state:

with angular frequency ; is a complex amplitude. For the original problems (2) and (3), the time-harmonic solutions are

where and are the solutions of the optimal control problems:

subject to

Therefore, the problem changes from the time domain to the frequency domain, and the time variation problem becomes a complex time-independent problem.

Since the operators in the problem are Hermitian, the same coefficient matrix can be obtained by using two approaches: the discretize-then-optimize or optimize-then-discretize approach. In order to solve problems (6) and (7), we choose to use the former. The FEM is used to discretize the problem, and the following finite-dimensional optimal control problems are obtained:

subject to

where is the mass matrix, is the stiffness matrix, with

and denotes the conjugate transposition vector, are the discrete forms of , respectively. is the linear Nédélec−I edge basis function [21,22]. This constrained optimization problem is solved by constructing the Lagrange function

where represents the Lagrange multiplier. In order to obtain stationarity, the following first-order necessary optimality conditions must be satisfied

The linear system is derived:

where . We simplify the system by eliminating variables. According to the system of Equation (9), we have , eliminating the Lagrange multiplier to obtain the system of equations:

3. The Preconditioners

Since the Krylov subspace method converges slowly when applied to large and sparse complex linear systems, an ideal preconditioner is required in order to achieve fast convergence. Since the coefficient matrix is Hermitian and it is more convenient to design the efficient preconditioning techniques when we consider the discretized linear system (12), we solve the discretized linear system (11) in this paper. For the discrete linear equations of the time-harmonic eddy-current optimal control problem, many papers have proposed and studied various preconditioners [13,14,15,16,25].

In 2013, Krendl et al. [13] designed the block-diagonal preconditioner for the Hermitian matrix

In 2016, according to the approximation Schur complement of the coefficient matrix [26]

Zheng et al. [14], on the basis of [13], proposed a generalized block-diagonal preconditioner

and applied the approximate Schur complement (14) to a block-triangular preconditioner

In 2018, Liang et al. [15] applied the approximate Schur complement (14) to the block two-by-two preconditioner and proposed the highly active structured preconditioner

In Ref. [15], it is proved that the structured preconditioned matrix and the block-triangular preconditioned matrix have the same eigenvalue distribution as . In 2021, Liang et al. [16] proposes an exact Schur complement form

which is inspired by [27]. The exact Schur complement (18) is used to accelerate the GMRES method to obtain the algorithm EI-GMRES.

Using the exact decomposition of (18), the article gives a practical expression for the inverse of the matrix :

where

and

Secondly, matrix (19) is applied to the preconditioned Krylov subspace method, and the following linear system needs to be solved:

According to Algorithm 1, the solution of the complex valued linear system (11) is equivalently transformed into the solution of two complex-valued linear systems with coefficient matrices and . For Steps 1 and 2, the article [16] first uses the C-to-R method to transform them into real-valued linear systems, respectively, and then the corresponding preconditioned square blocks (PRESB)-type preconditioners are used, i.e.,

and

| Algorithm 1 Computation of of system (11) |

|

This leads to Algorithms 2 and 3 below:

| Algorithm 2 Computation of from with , |

|

| Algorithm 3 Computation of from with , : |

|

Algorithms 2 and 3 implement steps 1 and 2 of Algorithm 1, respectively. The preconditioners and are such that the eigenvalue distributions of the preconditioned matrices is in the interval .

The advantage of algorithm EI-GMRES is that it retains the true Schur complement form and increases the accuracy of the calculation. However, there are two shortcomings in the exact Schur complement (18). The first is that the exact decomposition causes the first and third factors to be different, which increases the amount of computation. The second is that the exact decomposition introduces complex numbers, which increases computational complexity.

This paper focuses on how to overcome the shortcomings of the EI-GMRES algorithm. According to [13,14], matrices and have the same structure except for the different coefficient before . Note

which means that the two matrices are almost the same when the regularization parameter approaches 0.

In this paper, we propose a new approximate Schur complement

based on the Schur complement (14), and extend it to a block-triangular preconditioner and a block two-by-two preconditioner. A new block-triangular preconditioner

and a new structured preconditioner

are proposed for the Hermitian matrix . We prove that the distribution intervals of the eigenvalues of preconditioned matrices and are both when tends to 0. The block-triangular preconditioner and structured preconditioner proposed in this paper avoid the different decomposition factors and the calculation of complex numbers, which improves the efficiency of the calculation.

4. Block-Triangular Preconditioner

In this section, the algorithm of the preconditioner is presented through the expression of the inverse of the block-triangular preconditioner , and the eigenvalue interval of the preconditioned matrix is proved.

The preconditioner is applied to the preconditioned Krylov subspace method, and the linear systems need to be solved:

where denotes the current residual vector, and denotes the generalized residual vector.

Thus, the exact inverse can be written in the form

where . Based on (32), we can implement (29) by the following Algorithm 4.

| Algorithm 4 Computing the solution x of with and |

|

In the above steps, the equations to be solved in Steps 2–4 have coefficient matrices that are all real, symmetric, positive-definite matrices. We chose to use the conjugate gradient (CG) method to solve them.

Next, we consider the eigenvalue expressions of the preconditioned matrix .

Theorem 1.

Proof of Theorem 1.

Define . Then, the preconditioned matrix is similar to the following matrix

with . Since and are symmetric positive-definite matrices, there exists a positive diagonal matrix and an orthogonal matrix Q such that . Thus, we have

According to the eigenvalue determinant

the following equation

is obtained. The eigenvalues of the preconditioned matrix are solved to be 1 or

□

Theorem 2.

Assume that and are both symmetric positive-definite matrices. When the regularization parameter β tends to 0, the eigenvalues of the preconditioned matrix are equal to 1 or Equation (33), which lies in the interval

5. Structured Preconditioner

In this part, we decompose the structured preconditioner , deduce the algorithm of preconditioner , and prove the eigenvalue distribution interval of the preconditioned matrix .

Firstly, the structured two-by-two preconditioner is applied to the preconditioned Krylov subspace method, and the following linear system need to be solved:

where denotes the current residual vector, and denotes the generalized residual vector.

Secondly, based on [16] and Equation (28), the structured preconditioner can be decomposed into

with . According to the Equations (35) and (36), the linear system we solve becomes

thus obtaining the following two equations

and

Because of , Equation (38) can be written as

with . Similarly, Equation (37) can be written as

where

Finally, based on Equations (39) and (40), we can get the following Algorithm 5 to implement (35).

| Algorithm 5 Computing the solution x of with and |

|

In the above execution steps, the equations to be solved in Steps 2 and 3 have real, symmetric, positive-definite coefficient matrices. We chose to use the conjugate gradient (CG) method to solve them. Step 4 only requires direct computation and does not require any additional solving.

Next, we consider the eigenvalue expressions of the preconditioned matrix .

Lemma 1.

Suppose that and are positive-definite symmetric matrices. The true Schur complement of is , and the eigenvalues τ of the matrix satisfy

where is an eigenvalue of with

Proof of Lemma 1.

Assume that is an eigenpair of of the matrix ; thus,

Then, it is evident that such that S and are both positive-definite symmetric matrices. We obtain the equality

Divide both sides of Equation (42) by the coefficient to obtain

with . Multiply at both ends of Equation (43) to obtain

where is a symmetric positive-definite matrix, . The eigenvalues of the matrix can be obtained as

where is the eigenvalue of . Therefore, the eigenvalue interval of matrix is

□

In the following, we prove the eigenvalue interval of the preconditioned matrix .

Theorem 3.

Suppose that and are positive-definite symmetric matrices. When the regularization parameter β tends to 0, the eigenvalues of the preconditioned matrix are equal to 1 or Equation (41), which lies in the interval

Proof of Theorem 3.

Firstly, according to the decomposition form (36) of the structured preconditioner ,

can be obtained, where is an approximate Schur complement (26). Then, the inverse of the preconditioned matrix is

Let ; then, Equation (44) can be written in the following form

with .

Secondly, the preconditioned matrix is calculated. Denote

thus, we have

where

Finally, we can obtain the eigenvalues of the preconditioned matrix located in the interval □

6. Numerical Experiments

In this part, we solve linear system (11) using the new preconditioners and , and compare them with the preconditioner and the algorithm EI-GMRES. In Table 1, the numerical experiment method and corresponding abbreviations are shown.

Table 1.

The abbreviated names of the method being tested.

Example 1.

In the experiment, the CG method [28] was used in the inner iteration. The initial vector of the iteration method was assumed to be , the maximum number of iteration steps was , and the stopping tolerance was , where is the kth iteration. Similarly, the external iteration adopts the MINRES method or GMRES method. The initial vector of the iteration method was assumed to be , the maximum number of iteration steps was , and the stopping tolerance was . In Table 2, we show the relationship between the degree of mesh refinement and the orders of the matrices and .

Table 2.

Sizes of the matrix for the three-dimensional problem.

In Refs. [21,22], two classes of linear Nédélec edge finite element spaces were proposed. Here, we discretized the equations using the first class of Nédélec edge finite element spaces. The 3D problem used a tetrahedral dissection to discretize state variables and control variables. In order to construct the relevant matrices, we used the MATLAB package of [29]. All results were calculated in MATLAB with an Intel Xeon Gold 6258R Processor (38.5 M Cache, 2.70 GHz) FC-LGA14B, Tray.

We used the iteration step (denoted by “IT”) and CPU time in seconds (denoted by “CPU”) to illustrate the performance of the algorithm. For the additional regularization parameter , we chose two values as and .

In Table 3 and Table 4, the iteration time and iteration steps of different tested methods are shown with a mesh refinement degree of one in 3D.

Table 3.

IT and CPU of different methods with a mesh refinement degree of 1 ().

Table 4.

IT and CPU of different methods with a mesh refinement degree of 1 ().

In Table 5 and Table 6, the iteration time and iteration steps of different tested methods are shown with a mesh refinement degree of two in 3D.

Table 5.

IT and CPU of different methods with a mesh refinement degree of 2 ().

Table 6.

IT and CPU of different methods with a mesh refinement degree of 2 ().

In Table 7 and Table 8, the iteration time and iteration steps of different tested methods are shown with a mesh refinement degree of three in 3D.

Table 7.

IT and CPU of different methods with a mesh refinement degree of 3 ().

Table 8.

IT and CPU of different methods with a mesh refinement degree of 3 ().

Based on Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8, we can draw the following conclusions:

- With the increase in mesh refinement degree and matrix dimension, preconditioners and reduce the iteration steps and shorten the iteration time compared with preconditioner and the EI-GMRES algorithm.

- The algorithm is robust. Preconditioners and still have better numerical performance as parameters and change.

- As parameter decreases and tends to zero, the iteration time of preconditioners and also decreases. It shows that the assumption that tends to zero is reasonable.

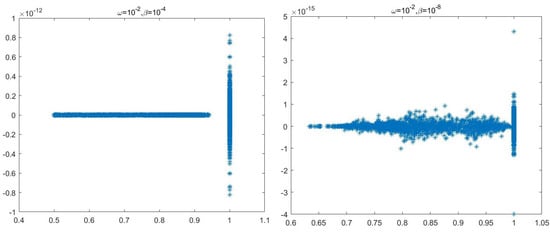

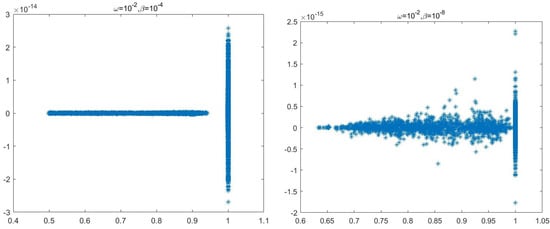

Finally, the eigenvalue distribution images of and are given. Here, the case where the mesh refinement degree is one and in 3D was tested.

In Figure 1, the eigenvalue distribution image of preconditioned matrix with is displayed.

Figure 1.

Eigenvalue distribution of preconditioned matrix .

In Figure 2, the eigenvalue distribution image of preconditioned matrix with is shown.

Figure 2.

Eigenvalue distribution of preconditioned matrix .

According to Figure 1 and Figure 2, the eigenvalues of the preconditioned matrices and are closer to one for smaller ’s. This partly explains the reason for the shorter iteration time for smaller ’s in the numerical calculations. As seen from Figure 1 and Figure 2, all the eigenvalues of the preconditioned matrices are indeed located in the interval , which is consistent with our spectral analyses in Section 4 and Section 5.

7. Conclusions

The purpose of this paper was to construct and analyze the block-triangular preconditioner and structured preconditioner of the discrete linear system of the time-harmonic eddy-current optimal control problem. It was proved that the eigenvalues of their corresponding preconditioned matrices were all located in the interval . Numerical experiments showed that both newly proposed algorithms were robust to the parameters involved in the problem and ran faster than some existing algorithms.

In the future, an extension of our work is to apply new block-triangular preconditioners and structured preconditioners to solve other problems arising in practice, such as the optimal control problem involving the heat equation in [15]. We can further apply this method to compute additional Hermitian operators, addressing problems as referenced in [32]. In addition, we can try to use the newly proposed preconditioners to solve more general algebraic problems with non-Hermite matrices, etc.

Author Contributions

Methodology, X.-H.S. and J.-R.D.; software, J.-R.D.; validation, J.-R.D.; formal analysis, X.-H.S. and J.-R.D.; investigation, X.-H.S.; resources, X.-H.S.; writing—original draft, X.-H.S. and J.-R.D.; writing—review and editing, X.-H.S. and J.-R.D.; project administration, X.-H.S.; funding acquisition, X.-H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tröltzsch, F. Optimal Control of Partial Differential Equations: Theory, Methods, and Applications; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2010; Volume 112. [Google Scholar]

- Kolmbauer, M. The Multiharmonic Finite Element and Boundary Element Method for Simulation and Control of Eddy Current Problems. Ph.D. Thesis, Johannes Kepler University, Linz, Austria, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lions, J.-L. Optimal Control of Systems Governed by Partial Differential Equations; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Ida, N. Numerical Modeling for Electromagnetic Non-Destructive Evaluation; Engineering NDE; Chapman & Halls: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Golub, G.H.; Wu, X.; Yuan, J.-Y. SOR-like methods for augmented systems. Bit Numer. Math. 2001, 41, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.-Z.; Golub, G.H.; Ng, M.K. Hermitian and skew-Hermitian splitting methods for non-Hermitian positive definite linear systems. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 2003, 24, 603–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzi, M.; Golub, G.H. An iterative method for generalized saddle point problems. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 2002, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Benzi, M. A generalization of the Hermitian and skew-Hermitian splitting iteration. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 2009, 31, 360–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.-Q.; Cao, Y. On local Hermitian and skew-Hermitian splitting iteration methods for generalized saddle point problems. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2009, 231, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.-L.; An, J.; Wu, Y.-J. A generalized preconditioned HSS method for non-Hermitian positive definite linear systems. Appl. Math. Comput. 2010, 216, 1715–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.-Z. Block alternating splitting implicit iteration methods for saddle-point problems from time-harmonic eddy current models. Numer. Linear Algebra Appl. 2012, 19, 914–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhang, G.-F.; Zhu, M.-Z. A block alternating splitting iteration method for a class of block two-by-two complex linear systems. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2015, 288, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krendl, W.; Simoncini, V.; Zulehner, W. Stability estimates and structural spectral properties of saddle point problems. Numer. Math. 2013, 124, 183–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhang, G.-F.; Zhu, M.-Z. A note on preconditioners for complex linear systems arising from PDE-constrained optimization problems. Appl. Math. Lett. 2016, 61, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.-Z.; Axelsson, O.; Neytcheva, M. A robust structured preconditioner for time-harmonic parabolic optimal control problems. Numer. Algorithms 2018, 79, 575–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.-Z.; Axelsson, O. Exact inverse solution techniques for a class of complex valued block two-by-two linear systems. Numer. Algorithms 2022, 90, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffa, A.; Ammari, H.; Nédélec, J.-C. A justification of eddy currents model for the Maxwell equations. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 2000, 60, 1805–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, K.; Sterz, O.; Hiptmair, R. Estimating the eddy-current modeling error. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2008, 44, 686–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, O.; Lukáš, D. Preconditioning methods for eddy-current optimally controlled time-harmonic electromagnetic problems. J. Numer. Math. 2019, 27, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaglmayr, S. High Order Finite Element Methods for Electromagnetic Field Computation. PhD Thesis, Universität Linz, Linz, Austria, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nédélec, J.-C. Mixed finite elements in R3. Numer. Math. 1980, 35, 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nédélec, J.-C. A new family of mixed finite elements in R3. Numer. Math. 1986, 50, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paige, C.C.; Saunders, M.A. Solution of sparse indefinite systems of linear equations. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1975, 12, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, Y.; Schultz, M.H. GMRES: A generalized minimal residual algorithm for solving nonsymmetric linear systems. SIAM J. Sci. Stat. Comput. 1986, 7, 856–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, O.; Liang, Z.-Z. A note on preconditioning methods for time-periodic eddy current optimal control problems. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2019, 352, 262–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, J.W.; Wathen, A.J. A new approximation of the Schur complement in preconditioners for PDE-constrained optimization. Numer. Linear Algebra Appl. 2012, 19, 816–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Farhat, C.; Murray, W.; Saunders, M. A practical factorization of a Schur complement for PDE-constrained distributed optimal control. J. Sci. Comput. 2015, 65, 576–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hestenes, M.R.; Stiefel, E. Methods of conjugate gradients for solving linear systems. J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand. 1952, 49, 409–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Valdman, J. Fast MATLAB assembly of FEM matrices in 2D and 3D: Nodal elements. Appl. Math. Comput. 2013, 219, 7151–7158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.-H.; Gu, X.-M.; Carpentieri, B. A dimension expanded preconditioning technique for saddle point problems. BIT Numer. Math. 2022, 62, 1983–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.-H.; Carpentieri, B.; Guo, J. A dimension expanded preconditioning technique for block two-by-two linear equations. Demonstr. Math. 2023, 56, 20230260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X. Efficient preconditioned iterative linear solvers for 3-D magnetostatic problems using edge elements. Adv. Appl. Math. Mech. 2020, 12, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).