Abstract

This study examines the problem of choosing optimal consumption, investment, early retirement, and effort levels for an economic agent who is unwilling to reduce their consumption over time. The agent’s income depends on a fixed wage rate, and varies proportionally with their level of effort, which incurs disutility due to labor. By applying the dual-martingale method, we reformulate the problem into its dual form, dividing it into two distinct sub-problems: one focuses on selecting a consumption path that does not decrease, while the other determines the optimal timing for early retirement. Using this method, we find optimal strategies in the form of explicit closed-form solutions.

Keywords:

consumption ratcheting; early retirement; effort choice labor supply; singular control; optimal stopping problem MSC:

91G10; 91B42; 93E20; 60H30

1. Introduction

Since Dybvig was awarded the Nobel Prize, one of his earlier works, the consumption ratcheting model in Dybvig [1], has been revisited, and has gained renewed attention. This model addresses the phenomenon where individuals are highly averse to lowering their standard of living once it has increased, emphasizing their tendency to maintain a certain level of consumption. This behavior has significant implications for retirement decisions and long-term financial planning. However, despite the growing interest in the consumption ratcheting framework, key factors such as labor supply, effort choice, and the timing of retirement have not been thoroughly explored.

In practice, individuals face complex decisions regarding their labor supply and work intensity, both of which directly affect their consumption and retirement planning. These factors become particularly important when considering the irreversibility of consumption decisions under a ratcheting constraint. Despite this, most existing models in the literature fail to account for the flexibility in labor effort and its impact on retirement behavior.

Jeon and Park [2] advanced this line of research by addressing the early retirement problem within a consumption ratcheting framework that incorporates the disutility of labor. However, their study did not allow for flexibility in effort choice or labor supply, leaving a gap in understanding how these factors influence optimal retirement strategies.

This paper aims to bridge that gap by incorporating both effort choice and labor flexibility into the consumption ratcheting framework. By allowing individuals to adjust their labor effort and retirement timing, we provide a more comprehensive analysis of how labor decisions interact with consumption and asset allocation under a ratcheting constraint. This contributes to a deeper understanding of optimal strategies for maintaining a desired consumption level while balancing work effort and retirement decisions.

To address this issue, we propose a model based on the consumption ratcheting framework, which integrates early retirement decisions and labor supply adjustments through effort choices. As the agent does not allow any decrease in consumption, the consumption trajectory is assumed to be strictly non-decreasing. The agent may choose an early retirement time, earning income proportional to their effort level at a fixed wage rate until retirement. Once retired, the decision is irreversible, meaning the agent cannot return to work. Additionally, exerting effort incurs a utility cost, represented by a convex function.

This problem introduces notable challenges, as the agent must simultaneously optimize, over a non-decreasing consumption trajectory, the timing of early retirement, an investment strategy, and the effort level. Consequently, solving the utility maximization problem requires the integration of stochastic control, singular control, and optimal stopping techniques.

To address this challenge, we utilize the dual-martingale approach to reformulate the agent’s problem into a dual framework. The additive structure of the utility cost allows the dual problem to be decomposed into two parts: a singular control for consumption, and an optimal stopping for early retirement. By solving these components independently, we derive explicit solutions for the dual problem. Additionally, a strong duality theorem is established, connecting the dual and primal problems and providing a characterization of the agent’s optimal strategies.

Earlier research has thoroughly explored early retirement and consumption ratcheting within continuous-time consumption and investment models (see, for instance, Choi and Shim [3], Choi et al. [4], Yang and Koo [5], Ivanov and Tian [6], Dybvig [1], Jeon et al. [7], Jeon et al. [8], Jeon and Park [2], Jeon and Park [9], and other related works). Our contribution to the literature lies in integrating these aspects by combining consumption ratcheting, early retirement, and labor supply through effort choices into a unified framework.

Additionally, our paper is closely related to the literature on consumption constraints (e.g., Abel [10], Chetty and Szeidl [11], Chetty and Szeidl [12], Detemple and Zapatero [13], Guasoni et al. [14], Deng et al. [15], van Bilsen et al. [16], and reference therein). Among them, we modeled the agent’s preference as consumption ratcheting, which is an extreme form of consumption habit.

Organization: Section 2 introduces the framework, which integrates early retirement, consumption ratcheting, and labor supply adjustments through effort choices. In Section 3, we formulate the dual problem and decompose it into two sub-problems: one focusing on the optimization of a non-decreasing consumption plan, and the other on identifying the optimal timing for early retirement. This section also characterizes the solutions to these sub-problems. Section 4 establishes a strong duality theorem, and provides a detailed characterization of the agent’s optimal strategy.

2. Model

We consider a financial market that operates in continuous time and consists of two primary assets: a risk-free asset with interest rate (here, r is constant), and a risky asset referred to as the stock .

The dynamics of are modeled by

where and are constants, and is a standard Brownian motion defined on the filtered probability space . The filtration is the usual augmentation of the natural filtration generated by .

Following the methodology of Dybvig [1], we investigate a setting where the agent prefers a non-decreasing consumption path. Let represent the agent’s consumption at time t. The consumption process is assumed to belong to the admissible set . The set consists of all -adapted, positive, right-continuous with left limits (RCLL), and non-decreasing processes that start with the initial value c.

Additionally, the agent receives income from labor and can choose an early retirement date, , at any time. However, the early retirement option is irreversible, meaning that once the agent retires early, they cannot return to work. The agent earns wage income proportional to their effort, , at a rate of at time t, where is the constant wage per unit of effort. Effort can be interpreted as working hours, work intensity, or both. The agent can choose effort within a bounded interval: for every ,

where L and H are fixed constants. The upper bound H corresponds to physical and/or psychological limit for effort when working. The lower bound L means that there exists a technological constraint on the effort level for work to be productive; work with an effort level lower than L is not productive.

Let represent the investment made by the agent in at time t. The evolution of the agent’s wealth process follows the dynamics given by:

with .

The agent’s preference is expressed by

Here, is the subjective discount rate, is the felicity function for consumption, and represents the utility cost of effort at time t.

To ensure the well-definedness, and to make the problem meaningful, we impose the following assumptions on utility u and cost h:

Assumption 1.

is with . Moreover, and in .

Remark 1.

Defining utility cost function h of effort as increasing and convex is reasonable because higher effort requires greater incremental costs due to physical and mental limitations. This structure reflects realistic decision-making, ensures mathematical stability in optimization, and aligns with observed behaviors like diminishing returns to effort.

Assumption 2.

is . Additionally, and in , and u satisfies the following conditions:

Remark 2.

Assumption 3 is the commonly used Inada condition frequently assumed in the economics literature. The Inada conditions ensure that marginal utility approaches infinity as consumption approaches zero and zero as consumption approaches infinity, promoting interior solutions in optimization problems.

Assumption 3.

For , the integral below is assumed to converge:

Here, and are two solutions to the following quadratic equation:

Remark 3.

Assumption 3 ensures the well-definedness of the value function in our optimization problem, as it is set in an infinite horizon framework. For further details, refer to Karatzas and Shreve [17] (Theorem 9.14).

Problem 1.

Let and be given. The agent’s value function is defined as

where represents the collection of all admissible strategies, subject to the following constraints:

- (i)

- ;

- (ii)

- is a -adapted positive process such that for all and almost surely;

- (iii)

- is an -progressively measurable process with ,

- (iv)

- . Here, is the family of all -stopping times that take values in ;

- (v)

- The wealth process , associated with the strategy , satisfies the natural wealth constraint:

3. Optimization Problem

Problem 1 requires identifying an increasing consumption , selecting the optimal retirement time , and determining the suitable effort level . To tackle the complexities of this problem, we employ the dual-martingale approach.

As part of this framework, we introduce the stochastic discount factor (SDF) , defined as

Using the SDF, the wealth dynamics Equation (2) can be reformulated as the following constraint:

We define the Lagrangian . For a given , the Lagrangian is represented as:

Here, is the initial Lagrange multiplier for (6), , and is defined as follows:

Here, represents the inverse of over the domain .

The inequality in (7) holds an equality if and only if the following holds for the effort level :

We now define the functions , , and as follows:

and

Using the Lagrangian , we establish the weak duality property: for any , the following inequality holds:

Here, is referred to as the dual value function. By its definition, is decomposed into two distinct sub-problems. The first sub-problem involves determining the non-decreasing consumption process, , while the second focuses on selecting the optimal retirement time, . The separability of these problems arises due to the additive structure of the disutility in the dual problem. Specifically, the consumption decision and the retirement timing are independent in the dual formulation. In contrast, these two components are interdependent in the primal problem, where decisions about consumption and retirement timing influence each other.

3.1. Sub-Problem I: Optimal Retirement Decision

We begin by analyzing the sub-problem associated with , which determines the optimal retirement time for the agent.

By applying a theory of optimal stopping, we consider the following variational inequality (VI) of :

There exists a critical threshold , such that

The smooth pasting condition provides the following boundary conditions:

To guarantee that the solution to the VI (13), we impose the following transversality condition:

For , the general solution to is composed of a combination of the homogeneous solution and a particular solution,

where the particular solution is

Remark 4.

Assuming a solution of the form , the characteristic equation becomes

which yields two roots, and . The general solution to the homogeneous equation is, therefore,

This condition ensures that does not grow exponentially as . Since grows unbounded as , the term involving must be excluded (). As a result, the general solution simplifies to

where vanishes as , satisfying the transversality condition.

Proposition 1.

The option value of voluntary retirement, , is expressed as

is and strictly convex function of . Also, , the optimal stopping time in , is given by

Proof.

is a martingale.

Define as

Using the strict convexity of h and the condition , it follows that

Since for , and

we obtain

For , the derivative of is given by

By applying the intermediate value theorem, we deduce the existence of a unique , such that

As a result, the parameter D is determined as follows:

The remaining parts are proved in the following three steps:

Step 1: in (25) is strictly convex and strictly increasing for .

Proof of Step 1. We can rewrite the form of as follows:

For , the derivative is

where integration by parts has been applied, and we use

Similarly, for , the second derivative is given by

where we have applied integration by parts to the Riemann–Stieltjes integrals, along with the condition

Since is non-decreasing, the Riemann–Stieltjes integrals remain non-negative. Furthermore,

Thus, is strictly convex for .

Given that , it follows that

Step 2: The function satisfies the variational inequality given by

where

Proof of Step 2. Since , it follows from Step 1 that

Clearly,

Since and for , we have

Combining these, satisfies the stated variational inequality.

Step 3: in (25) satisfies the following properties:

- (i)

- .

- (ii)

- .

- (iii)

- For all fixed , the process

Using Steps 1, 2, and 3, we conclude from Knudsen et al. [18] (Theorem 3.2) that

where

□

Lemma 1.

The following limiting behaviors hold:

Proof.

It is clear that

By Knudsen et al. [18] (Proposition 4.1),

By applying integration by parts, we obtain

Since is bounded for , the term involving vanishes as . Consequently,

Hence,

□

Lemma 2.

Proof.

For , the smoothness of implies

By utilizing the generalized Itô’s lemma to , we obtain

where is a risk-neutral measure with .

Let . Then,

Taking expectations under , and noting that the terminal term vanishes due to the transversality condition, we obtain

□

3.2. Sub-Problem II: Adjusting Consumption

In this subsection, we explore the optimal adjustment of consumption, building upon related discussions in Jeon et al. [8] and Jeon and Park [2]. For clarity, we summarize the key ideas and results without delving into exhaustive detail.

For any , the inverse mapping , defined for a right-continuous non-decreasing consumption process , is expressed as

Exploiting the one-to-one correspondence between the consumption path and its inverse , we derive the following:

The optimization problem can be represented as

As shown in Jeon et al. [8] and Jeon and Park [2], the following relationship holds:

Using the optimal stopping theory, we consider the variational inequality of as follows:

alongside the transversality condition,

Here, is defined as

Using an approach analogous to the one applied in the proof of Proposition 1, it can be shown that the following result holds:

with

For , a general solution takes the form

By enforcing continuity and smoothness at , we determine

The solution becomes

The function satisfies the following:

- ;

- ;

- There exist constants and , such that

Proof.

For , it is straightforward to verify that

We define a temporary function as

Calculating its derivative yields

Since , it follows that for all .

For , where , we compute

Thus, satisfies the conditions of the variational inequality (33) for both cases, and . □

Using an approach analogous to the one applied in the proof of Proposition 1, it can be shown that the following result holds:

where .

For a fixed , is given by

It then follows that

Since

where is defined as the inverse function of .

Using this relationship, we define as

According to Jeon et al. [8] and Jeon and Park [2], the following results hold:

Moreover, we have

In addition, is a strictly convex function and twice continuously differentiable for , with the following asymptotic properties:

4. Optimal Strategies

Building on the results derived in Section 3, we finally state our main theorem as follows.

Theorem 1.

For a fixed and :

- (a)

- and are connected through the strong duality given bywhere uniquely satisfies the condition .

- (b)

- The optimal retirement time is given bywhere .

- (c)

- The optimal consumption and investment , and effort are as follows:andMoreover, the wealth process , associated with the optimal strategy , is given by

Proof.

By utilizing Lemma 1 and Equation (53), the following limiting behavior is obtained:

Furthermore, using Lemma 2 and Equation (52), it can be expressed that

Due to the strict convexity of both and , the limits in Equation (60) guarantee the existence of a unique solution satisfying

This implies

where , , and are defined as specified in the theorem.

Adapting the arguments from Karatzas and Wang [19] (Lemma 6.3), there exists an admissible portfolio such that the strategy , and the associated wealth process satisfies

Since are Markov processes, the strong Markov property ensures

Applying the generalized Itô lemma to leads to the result

The relationship between x and is further elucidated as follows:

Therefore, it follows that

Finally, combining with the weak duality result (12), we conclude that

Thus, we conclude that is optimal. □

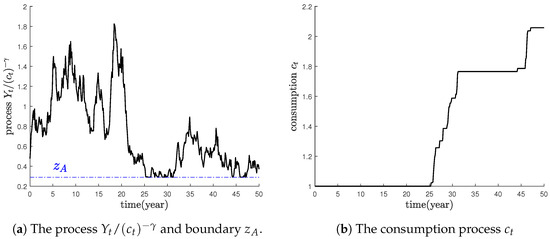

Figure 1 illustrates the process of consumption adjustment through simulation results. As shown in the figure, whenever the process reaches the free boundary , consumption increases.

Figure 1.

The consumption adjustment.

5. Implications

This section provides numerical simulations that highlight the optimal strategies obtained from Theorem 1. To achieve this, we represent the agent’s preferences with the constant relative risk aversion (CRRA) utility function as follows:

Moreover, we assume the quadratic cost function, as in Cadenillas et al. [20] and Bensoussan et al. [21],

Then, we compute the explicit form of as

Under these circumstances, is represented as

where is a unique solution of the algebraic equation

- For ,

- For ,

- For ,

Moreover, for a given , is given by

where

Using the closed forms of and , we can compute all the optimal strategies stated in Theorem 1.

To provide numerical results for the optimal strategies, we use the following parameters: , , , , , , , and .

For a given , by applying the one-to-one mapping from the dual domain to the wealth domain , we define the wealth boundaries and as follows:

The boundary represents the consumption adjustment boundary for wealth, and the boundary represents the retirement boundary for wealth. Let be defined as follows:

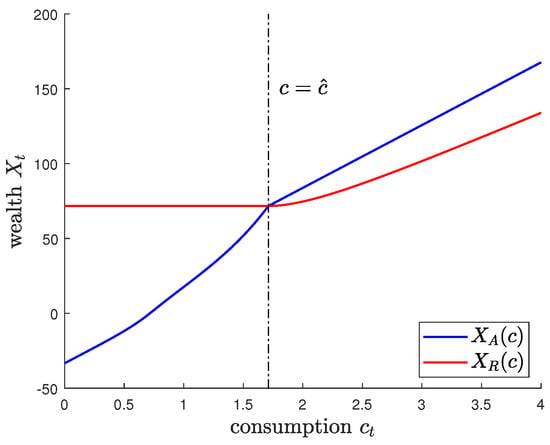

Figure 2 illustrates the changes in and with respect to consumption. As shown in the figure, if consumption is smaller than , the boundary is greater than . Conversely, if consumption is greater than , the boundary is greater than . This implies that when the current consumption is sufficiently large relative to wealth, the agent will choose the early retirement decision before increasing consumption.

Figure 2.

Two boundaries and .

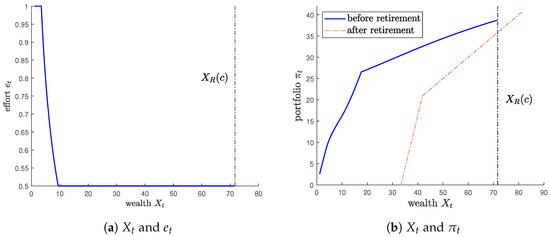

Figure 3 illustrates the relationship between wealth and effort , as well as between wealth and portfolio . As wealth increases sufficiently, the agent reduces effort due to the relatively lower need for income. Additionally, it can be observed that the agent always retires after reaching the lower bound of effort, L. Moreover, it can be observed that the agent increases risky investment based on wealth just before retirement. As commonly known in the early retirement literature, the agent increases risky investment to quickly reach the wealth boundary required for retirement. Immediately after retirement, a downward jump in risky investment occurs.

Figure 3.

The relationships between and , and between and .

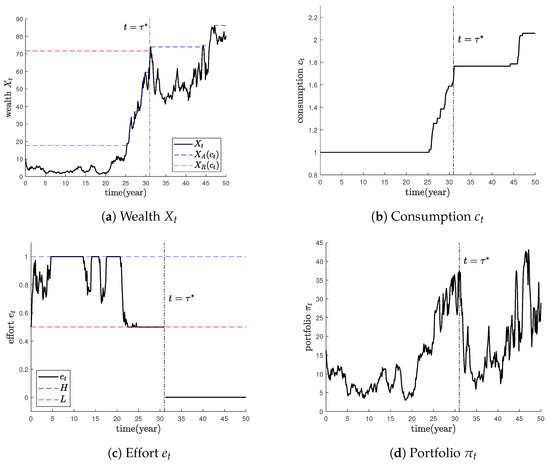

Figure 4 provides simulation results for the optimal strategies. As mentioned earlier, the agent increases consumption whenever their wealth reaches the boundary , and chooses early retirement upon reaching .

Figure 4.

Simulation paths for optimal strategies.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we have developed a theoretical framework for optimal consumption, investment, retirement, and effort decisions under a consumption ratcheting constraint using a dual-martingale approach within a continuous-time financial market. Our results provide a rigorous mathematical characterization of a single agent’s decision-making process, highlighting the interplay between stochastic control, singular control, and optimal stopping.

While our focus has been on single-agent optimization, we acknowledge that extending this framework to incorporate interactions among heterogeneous agents or emergent phenomena, as typically explored in agent-based modeling (ABM), could offer additional insights. ABM approaches, which simulate the behavior of multiple agents with diverse preferences and strategies, could complement our model by investigating how individual decisions are influenced by collective dynamics. However, since such an extension lies beyond the scope of the current study, and would require significant modifications to the present setup, we leave this for future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.K.; Methodology, J.J.; Formal analysis, G.K.; Investigation, G.K. and J.J.; Writing—original draft, J.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Seoul National University of Science and Technology.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dybvig, P.H. Dusenberry’s Ratcheting of Consumption: Optimal Dynamic Consumption and Investment Given Intolerance for any Decline in Standard of Living. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1995, 62, 287–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.; Park, K. Optimal Retirement and Portfolio Selection with Consumption Ratcheting. Math. Financ. Econ. 2020, 14, 353–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.J.; Shim, G. Disutility, Optimal Retirement, and Portfolio Selection. Math. Financ. 2006, 16, 443–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.J.; Shim, G.; Shin, Y.H. Optimal Portfolio, Consumption-Leisure, and Retirement Choice Problem with CES Utility. Math. Financ. 2008, 18, 445–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Koo, H.K. Optimal Consumption and Portfolio Selection with Early Retirement Option. Math. Oper. Res. 2018, 43, 1378–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, K.; Tian, W. Optimal Early Retirement with Target Wealth. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 2024, 167, 104926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.; Koo, H.K.; Shin, Y.H. Portfolio Selection with Consumption Ratcheting. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 2018, 92, 153–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.; Koo, H.K.; Shin, Y.H. Ratcheting with a Bliss Level of Consumption. Optim. Lett. 2019, 13, 1535–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.; Park, K. Dynamic Asset Allocation with Consumption Ratcheting Post Retirement. Appl. Math. Comput. 2020, 385, 125418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, B.A. Asset Prices under Habit Formation and Catching Up with the Joneses. Am. Econ. Rev. 1990, 80, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Chetty, R.; Szeidl, A. Consumption Commitments and Risk Preferences. Q. J. Econ. 2007, 122, 831–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, R.; Szeidl, A. Consumption Commitments and Habit Formation. Econometrica 2016, 84, 855–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detemple, J.; Zapatero, F. Asset Prices in an Exchange Economy with Habit Formation. Econometrica 1991, 59, 1633–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guasoni, P.; Huberman, G.; Ren, D. Shortfall Aversion. Math. Financ. 2020, 30, 869–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Li, X.; Pham, H.; Yu, X. Optimal Consumption with Reference to Past Spending Maximum. Financ. Stoch. 2022, 26, 217–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bilsen, S.; Laeven, R.J.A.; Nijman, T.E. Consumption and Portfolio Choice Under Loss Aversion and Endogenous Updating of the Reference Level. Manag. Sci. 2020, 66, 3927–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatzas, I.; Shreve, S. Methods of Mathematical Finance; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen, T.S.; Meister, B.; Zervos, M. Valuation of Investments in Real Assets with Implications for the Stock Prices. SIAM J. Control Optim. 1998, 36, 2082–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatzas, I.; Wang, H. Utility Maximization with Discretionary Stopping. SIAM J. Control Optim. 2000, 39, 306–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadenillas, A.; Cvitanić, J.; Zapatero, F. Leverage Decision and Manager Compensation with Choice of Effort and Volatility. J. Financ. Econ. 2004, 73, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensoussan, A.; Cadenillas, A.; Koo, H. Entrepreneurial Decisions on Effort and Project with a Non-Concave Objective Function. Math. Oper. Res. 2015, 40, 902–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).