Abstract

The terms “Industry 5.0” and “smart logistics” have recently emerged as key concepts within the field of logistics. Nevertheless, the interconnection between these two concepts has been less extensively examined in academic literature, particularly in the context of emerging economies. In the contemporary business context, the logistics industry is seeking to advance sustainable development through the implementation of Industry 5.0. However, the industry is still in its nascent stages of realizing the transformation of smart logistics. Accordingly, the objective of this study is to identify the key drivers of Industry 5.0 in relation to the advancement of smart logistics in the logistics industry in emerging economies. In this study, the initial screening and identification of 15 core drivers was conducted using the fuzzy Delphi method. This involved the collation of the relevant literature and the collection of opinions from experts in the field. The identified drivers were then classified into three groups: sustainability, people-centricity, and resilience. Subsequently, the study adopted the Grey-DEMATEL method, which combines grey system theory with the decision making trial and evaluation laboratory (DEMATEL) technology. This approach enables the effective resolution of complex system issues characterized by uncertainty and incomplete information, facilitating the identification of causal relationships between the drivers and the construction of a centrality–causality outcome diagram. The study identified two key drivers: “government support policies” and “logistics standardization and infrastructure development”. This study represents a preliminary investigation into the ways managers, practitioners and policy makers can leverage Industry 5.0 to advance the field of smart logistics within the logistics industry.

MSC:

90B06

1. Introduction

As we all know, the traditional logistics industry has significant shortcomings in terms of service functions, degree of informatization, ability to integrate resources, standardization and normalization, etc. For example, the traditional logistics industry is relatively lagging in terms of technological innovation [1], failing to fully utilize modern information technology, such as big data, cloud computing, and the Internet of Things, to enhance service quality and efficiency [2]. Therefore, the transformation and upgrading of traditional logistics to intelligent logistics has become an inevitable trend of development [3]. For the logistics industry, Industry 5.0 promotes a deep integration of man and machine, giving the logistics industry unprecedented flexibility and adaptability while accurately responding to the diversified needs of the market [4]. This is achieved through intelligent logistics technology, which facilitates transparency, visualization, and traceability within the supply chain [5]. However, the logistics industry encounters numerous challenges in the adoption of smart logistics. From an economic standpoint, the initial investment, operating costs, and time uncertainty often deter enterprises from embracing smart logistics. Technologically, smart logistics encompasses a range of sophisticated technologies, and the complexity and specialization of these technologies, including the Internet of Things, big data, and artificial intelligence, contribute to the difficulty of integrating new technology into existing systems. The rapid pace of technological advancement in the logistics sector further complicates the process of technological upgrading. If new technology cannot be effectively integrated with existing systems, it can lead to significant challenges and costs for enterprises seeking to upgrade their technological capabilities [6]. Therefore, for logistics companies to thrive, they must utilize Industry 5.0 to overcome the above obstacles [7,8].

The EU launched its Industry 5.0 strategy in due course in 2021 [9], aiming to lead the transformation of European industry toward sustainability, human-centeredness, and resilience through in-depth scientific research and innovative practices [10]. Some of the technologies include artificial intelligence (AI), big data and analytics, blockchain, digital twins, Internet of Things (IoT), cyber-physical systems (CPS), and cybersecurity technologies [11]. In recent years, Industry 5.0 has had a strong impact on all aspects of industry and human society and has gained traction and recognition in the global business, scientific, and political arenas [12]. With the arrival of Industry 5.0 for the logistics industry, the core is to promote deep integration and collaboration between humans and machines [13], This new model of man–machine symbiosis gives the logistics industry unprecedented flexibility and adaptability, enabling it to accurately match the market’s diverse and complex production needs. As a further development of Industry 4.0, Industry 5.0 offers efficient, interactive solutions for the optimization of smart logistics, thereby facilitating intelligent upgrading and sustainable development [11,14]. Industry 5.0 has emerged as a critical factor for the logistics sector to thrive in a dynamic competitive environment by driving intelligent transformation and efficiency enhancement [7,15].

In recent years, numerous studies have demonstrated that Industry 5.0 can act as a catalyst for the diffusion of smart logistics, thereby promoting economic development in logistics enterprises [3,13,16]. From a sustainability perspective, Industry 5.0 leverages circular economy, production regeneration, and green technology to establish the core concept of resource conservation in smart logistics [17]. Additionally, Industry 5.0 adopts a human–machine collaboration model to achieve dual enhancements in human intelligence and productivity, effectively reducing error rates [18]. During this process, logistics enterprises need to actively implement technologies and methods aligned with Industry 5.0 in their smart logistics transformation, aiming to construct and optimize sustainable logistics processes and operational models to meet future challenges [19].

However, compared with developing economies, developed economies are more likely to adopt Industry 5.0 technologies in the logistics sector [20]. Table 1 lists the top 20 countries contributing the most to the global logistics industry.

Table 1.

Top 20 countries with the highest Logistics Performance Index (LPI).

As shown in Table 1, 17 of the listed countries are developed economies, while 3 are developing economies. Notably, China, as the largest developing economy, ranks 20th in terms of its Logistics Performance Index (LPI), highlighting the numerous challenges still faced by China’s logistics industry. The LPI, a key indicator for assessing the development status of the logistics sector, is influenced by several factors, including customs efficiency, the ease of international transport, overall logistics service capability and quality, and timeliness of deliveries. Comparisons reveal that economies such as Singapore (LPI score 4.3), Finland (4.2), and Germany (4.1) exhibit significant advantages in logistics performance. In contrast, most emerging economies, including China and the United Arab Emirates, are not among the strongest performers in logistics metrics. However, China, as the world’s second-largest economy, has a large development trend, and the market demand for intelligent logistics will continue to grow. At the same time, the Chinese government will continue to promote the innovation and development of the logistics industry, especially the construction of intelligent logistics, which will provide a broader space and opportunities for the development of the logistics industry.

It is important to note that the adoption of Industry 5.0 technologies is still in its early stages, particularly in developing countries like China [19]. If successfully combined with smart logistics in emerging economies, the impact on national economic contributions could be substantial [20]. Our study’s novelty lies in the fact that, while a few existing studies have confirmed the positive effects of Industry 5.0 on smart logistics, there are significant challenges in applying these technologies in the context of logistics enterprises in emerging economies. Specifically, the key drivers that can facilitate the successful transition to smart logistics in emerging economies when adopting Industry 5.0 have not been adequately addressed in the existing literature. Therefore, this study aims to address these gaps by focusing on logistics enterprises in emerging economies and identifying the following research questions:

- What are the key drivers for logistics companies in emerging economies to enhance smart logistics in line with the Industry 5.0 paradigm?

- Examine the influence and underlying relationships of these key drivers.

In conclusion, this study identifies potential key drivers within the Industry 5.0 domain through a systematic literature search and the fuzzy Delphi method (FDM), which was employed to overcome the subjectivity and uncertainty of individual judgment [21]. Based on the aforementioned findings, a questionnaire survey was designed and implemented. This was followed by the application of the Grey-DEMATEL methodology [22], which was employed to determine the causal relationships between the drivers and to map the correlations between the drivers. The findings of this study can provide corporate decision-makers, investors, and government agencies with an accurate and efficient basis for decision-making, thus assisting them in developing more targeted strategies and policy measures.

The remaining chapters of this study are organized as follows: Section 2 introduces and discusses the relevant literature. Section 3 describes the FDM method and the Grey-DEMATEL method. Section 4 discusses an empirical study and analysis of the results for logistics firms in emerging economies. Section 5 presents the results of this study, and, finally, Section 6 presents the conclusions as well as the contributions of the study and the directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

This section presents a review of the literature on Industry 5.0 and smart logistics, identifying the key drivers and research gaps in this field.

2.1. Industry 5.0 and Intelligent Logistics

While the primary focus of Industry 4.0 was on the technological transformation of industrial paradigms with minimal consideration of human nature and society [23], the concept of Industry 5.0 has been a prominent area of research since 2017 [15], and in contrast to the focus on equipment interconnectivity and interconnectivity in Industry 4.0, Industry 5.0 places greater emphasis on the integration of humans and computers at the level of diverse factory collaboration [19]. According to Emma-Ikata and Doyle-Kent, Industry 5.0 significantly enhances production efficiency, creates human–machine adaptability, and ensures accountability in interactive and continuous monitoring activities. Akundi et al. argue that Industry 5.0 is built on principles such as human-centricity, environmental management, and social benefits [13]. It integrates organizational principles and technology to form a sustainable, human-centric, and resilient system. From a management point of view, logistics companies need to meet the requirements of rapid product development and flexible production [24]. Industry 5.0 will significantly improve manufacturing efficiency, create human–machine versatility, and have a major impact on smart logistics, supply chain management, and business models [20], By adhering to ecological boundaries and valuing the well-being of workers, businesses can transform into highly adaptive and resilient drivers of prosperity [11].

In recent years, the topics of Industry 5.0 and smart logistics have garnered widespread attention [2]. While many scholars have studied these topics from various perspectives, the supporting literature remains limited, with only about 18 key articles currently available. Some of the most notable works in this area include the following: Cardarelli et al. present a data fusion approach to obstacle detection in automated systems based on advanced automated guided vehicles (AGVs), which links Industry 5.0 and smart logistics [25]. Jefroy et al. delineate the hallmarks of Industry 5.0 and smart logistics, emphasizing the integration of smart automation, smart devices, smart systems, and smart materials [26]. They underscore that these novel technologies are not designed to supplant human operators but rather enhance their operations in a more efficacious manner, thereby facilitating the production of highly personalized products and services. Lin et al. established a framework to improve the sustainability, efficiency, and accessibility of smart logistics by integrating technologies into cyber–physical–social systems (CPSS) [8]. Despite the considerable attention devoted to examining the impact of disruptive technologies in smart logistics and supply chains [6,27], warehouse management [28], freight transportation [29], and other related topics, the primary focus is on the technological aspects rather than the main characteristics of Industry 5.0 [30]. The core elements of Industry 5.0 indicate that, alongside the technology-driven transformation of Industry 4.0, greater attention needs to be paid to social, environmental, and human perspectives. This shift will have a significant impact on logistics operations and management [19]. The objective is to establish a comprehensive framework for addressing emerging human and socially relevant challenges and achieving sustainable development through the adoption of disruptive technologies and innovative solutions [31].

From the above, it is evident that the majority of existing literature addresses the interrelationships, impediments, frameworks, technological domains, and practical applications between Industry 5.0 and smart logistics. However, it appears that the current literature still lacks an analysis of Industry 5.0 drivers to enhance smart logistics [32], particularly in the context of the logistics industry in emerging economies. Therefore, it is particularly important to identify Industry 5.0 drivers for logistics firms in emerging economies to help them better develop smart logistics in the context of competitive external segments.

2.2. Industry 5.0 Drivers for Enhancing Smart Logistics

A driver can be defined as “a resource, process, or condition” that is necessary for the successful implementation and development of a business [33]. In light of the numerous obstacles, including low digitization, a scarcity of operational resources, and a dearth of expertise, it is challenging for logistics firms in emerging economies to make effective investments in critical and accurate areas with limited capital [34]. Given the nascent stages of Industry 5.0 implementation in emerging economies, it is crucial to comprehend and assess the pivotal drivers for effective Industry 5.0 deployment, intending to achieve sustainable development in the logistics sector. To identify the drivers, this study searched for the following keywords in the existing literature: enablers, success factors, Industry 5.0, smart logistics, and sustainability of logistics companies. To achieve this, the present study searched the Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases, utilizing the search terms ‘Industry 5.0’ and ‘smart logistics’. The initial search yielded a total of 128 documents. Subsequently, a screening process was conducted to select relevant literature. The screening criteria were as follows: (1) the paper must ensure the international scope of the study; (2) the paper must be related to Industry 5.0 and smart logistics; (3) the title, abstract, and keywords of the paper must be related to the topic. Following this process, 42 papers were selected from the literature. Following discussions with experts, a total of 26 Industry 5.0 drivers for enhancing smart logistics were identified from the literature (see Table A1).

2.3. Research Gap

At present, Industry 5.0 has been effectively introduced in developed countries. However, in recent times, plans for investment and adoption of Industry 5.0 are also implemented in developing countries. For example, China is currently working on the “14th Five-Year Plan” for the development of modern logistics. This plan is designed to promote the high-quality development of the modern logistics industry and provide robust support for the formation of a strong domestic market. Additionally, it aims to facilitate a high level of international integration. Concurrently, implementing Industry 5.0 in smart logistics is a difficult task in itself; it must not only be efficient and convenient but also be able to incorporate these concepts. This requires technological innovation and integration to adapt to new demands [3,18]. For example, Aheleroff et al. demonstrate the transition from mass customization to mass personalized production in Industry 5.0 [24]. Previous research findings based on developed countries or large enterprise contexts have prompted questions regarding the applicability and validity of research findings in emerging economies and logistics enterprise environments.

Consequently, the identification of pivotal drivers can assist logistics enterprises in the effective utilization of Industry 5.0, thereby facilitating the advancement of intelligent logistics [35]. Nevertheless, there is a paucity of discourse in the extant literature on the micro and macro levels of Industry 5.0 within the enterprise. Consequently, a substantial corpus of research is required to comprehend and adopt Industry 5.0 and, in turn, harness its drivers for the advancement of smart logistics [1,23]. Concurrently, the implementation of Industry 5.0 in smart logistics represents a significant challenge. To achieve this, managers must consider both human and technological aspects [15]. Furthermore, a comprehensive grasp of the causal relationships between the drivers of Industry 5.0 is essential for optimizing the eco-economic and social benefits for logistics companies [16]. To enhance the success of smart logistics in organizations, potential drivers must be proposed [36]. In order to address the research gaps identified in this study, this study is dedicated to identifying the core Industry 5.0 drivers for the development of smart logistics and further analyzing the influence and causality between them.

3. Research Methodology

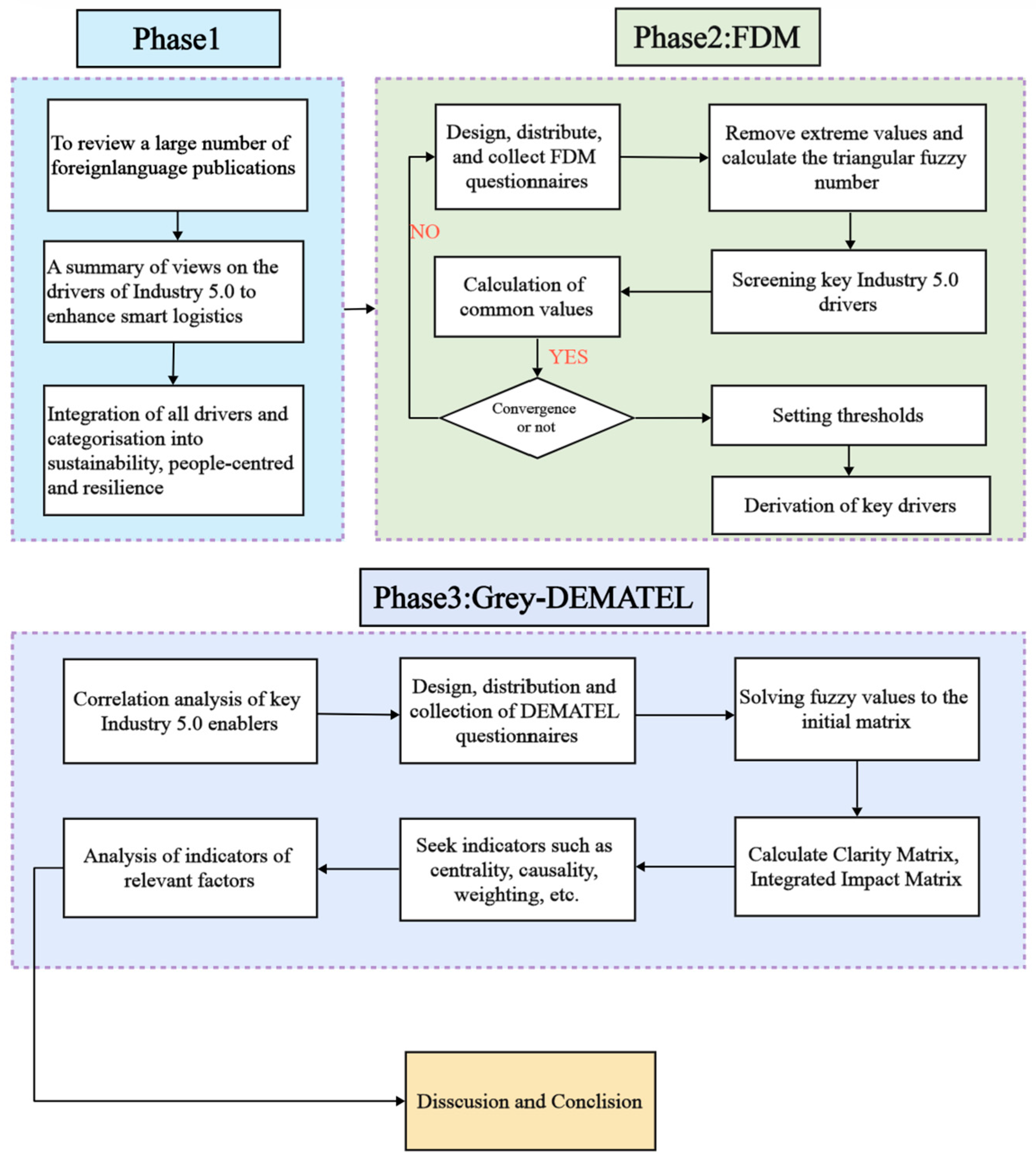

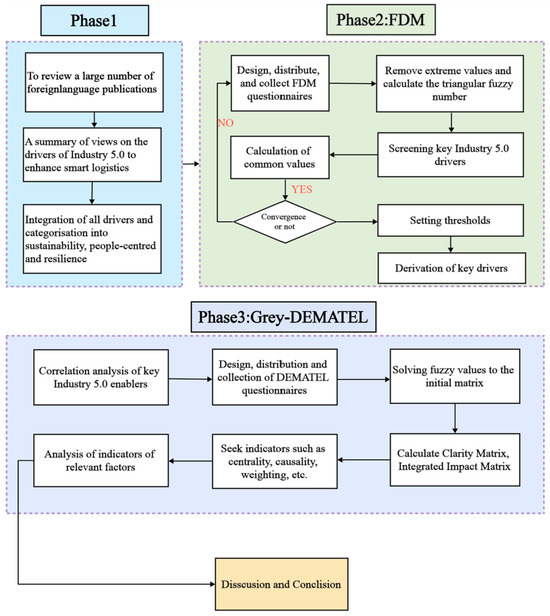

This study employs a literature review methodology to examine extensive literature and identify the driving factors of Industry 5.0 that enhance smart logistics levels. These factors are primarily categorized into three areas: sustainability, human-centricity, and resilience. The research methods utilized include the fuzzy Delphi method (FDM) and the grey decision-making trial and evaluation laboratory (Grey-DEMATEL). The specific analytical steps are outlined as follows.

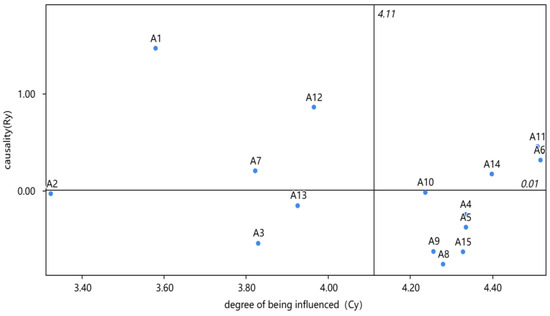

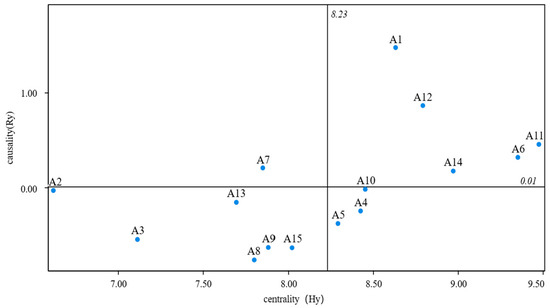

First, a literature search method was employed to initially identify and screen potential drivers of Industry 5.0. Subsequently, the FDM was used to further refine these factors and determine the key drivers. During this process, the consensus value (Gi) of each expert was calculated, and a reasonable Gi threshold was set to select the final key drivers. Next, based on their characteristics, these key drivers were systematically classified into three distinct driver groups. To further investigate the impact of each key driver on Industry 5.0, this study combined Grey-DEMATE method. Using this approach, the influence degree (Dy), influenced degree (Cy), centrality (Hy), and causality (Ry) of each factor were calculated. These metrics collectively reveal the importance and interrelationships of the factors within the system. Finally, based on the calculated causality and centrality values, a causality diagram was created to visually illustrate the causal relationships and influence paths among the factors. The following sections provide a detailed explanation of these steps, and the overall framework and specific procedures of the research method are shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Research methodology flow.

3.1. Introduction to Methods

FDM is a group decision-making technique that collects expert opinions through multiple rounds of anonymous surveys, ultimately aggregating them to form a relatively consistent expert forecast [37]. This method emphasizes anonymity, feedback, and statistical analysis, which helps avoid the influence of authority or majority opinion, ensuring the fairness and accuracy of decisions. It aims to overcome the shortcomings of traditional qualitative evaluation methods, making subjective judgments more closely aligned with objective reality. Typically, FDM involves multiple rounds of surveys and feedback, meaning that expert opinions are refined and improved after each round of feedback. Through repeated consultations and feedback, a more consistent prediction or assessment outcome can eventually be achieved. This conclusion combines the advantages of fuzzy theory and the Delphi method, which can deal with complex and fuzzy problems and make the decision-making process more scientific and objective [38].

This study conducted an extensive review of foreign literature to summarize the views of multiple scholars on the drivers of Industry 5.0 for enhancing smart logistics. Subsequently, all identified drivers were consolidated and categorized into three groups: sustainability, human-centricity, and resilience. The consolidated factors were then distributed to 12 experts in the relevant field using the FDM. The calculation steps of the FDM are as follows:

- Design an electronic questionnaire. The questionnaire sets a value range of 0–10 to assess the maximum and minimum values where a higher selected value indicates greater importance of the factor.

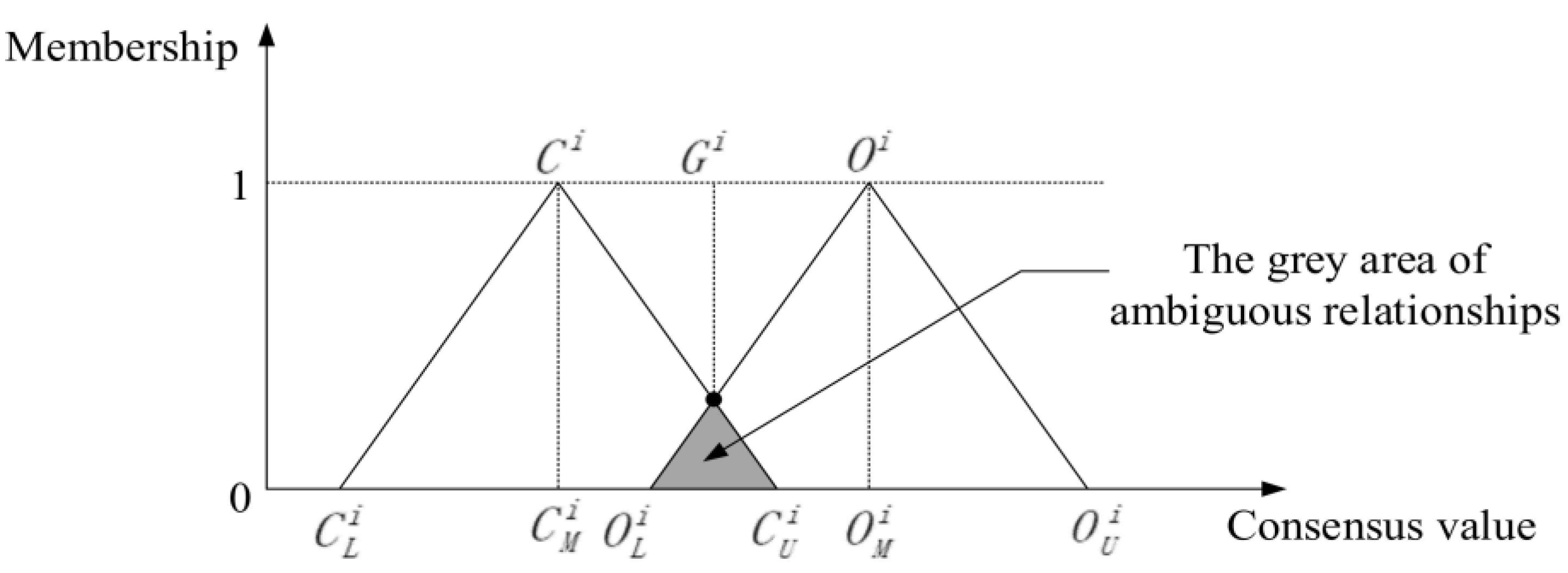

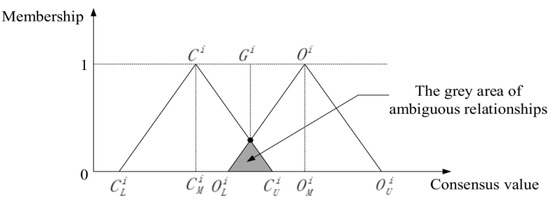

- Establish triangular fuzzy numbers. The overlapping area between two triangular fuzzy numbers is referred to as the “grey zone”. See Figure 2:

Figure 2. Triangular fuzzy numbers for maximum and minimum values.

Figure 2. Triangular fuzzy numbers for maximum and minimum values.

After the questionnaire data are organized, the standard deviation σ is calculated by Equation (1), and the number of numbers corresponding to each evaluated factor criterion is calculated by Equations (2) and (3) to form the triangular fuzzy function of “the most conservative cognitive value” = (, , ) and the triangular fuzzy function of “the most optimistic cognitive value” = (, , ).

- 3.

- After demulsifying Ci and Oi in the statistical questionnaire removing the extreme values that are more than twice the standard deviation and then pressing = (, , ) and = = (,,), calculate the triangular fuzzy number of the remaining scores.

Among them, the formula symbols represent the meaning of the following Table 2:

Table 2.

Meaning of formula symbols.

- 4.

- Calculate the importance of consensus Gi among experts, which is categorized into the following three cases:

- When Zi = 0, indicating that there is a consensus zone of expert opinion on the factor guidelines for assessment, the following formula is used for calculation:

- When Zi > 0, and Zi ≤ Mi, it means that although there is no consensus zone, it can be calculated by Equation (6) that:

- When Zi > 0 and Zi < Mi, it means that no consensus zone needs to repeat the above Steps 1 to 3 until the result of the expert’s opinion reaches convergence.

- 5.

- Finally, on this basis, with the objective of establishing an appropriate threshold limit for the results obtained in order to filter out factors of high importance, retain those above the threshold and eliminate those below the critical value.

3.2. Introduction to the Grey-DEMATEL Method

The DEMATEL methodology is an MCDM (Multiple Criteria Decision Making) methodology for identifying key drivers and assigning weights to indicators, enabling in-depth analyses of the logical relationships between factors and the degree of influence. Both methodologies have clear advantages in decision analysis, risk management, factor identification, etc. In this study, the specific steps for analyzing the Grey-DEMATEL model of Industry 5.0 drivers for enhancing smart logistics are as follows:

- Questionnaires were distributed using a questionnaire survey and data were collated to obtain the original relationship matrix for each factor.

- Matrix conversion: using Table 3 expert scoring gray language scale to enhance the smart logistics Industry 5.0 driving factors for conversion, the direct influence relationship matrix B = is obtained.

Table 3. Expert semantic scale design.

Table 3. Expert semantic scale design. - Standardized treatment, standardized according to Equation (7).where denotes the normalized lower limit gray matrix, denotes the normalized upper limit gray matrix, and denotes the difference between the maximum value of the upper limit mean gray matrix and the minimum value of the upper limit mean gray matrix.

- 4.

- Clarification processing. Clarification is performed according to Equation (8).

- 5.

- The clarity value is found with the following formula:

- 6.

- Row summation and column summation. The matrix is normalized and clarified to obtain the direct relationship matrix A=, which is in the interval [0, 1]. Using formulas (10) and (11) for row summation and column summation, the rows and columns of the total of the maximum value are selected to obtain the direct specification matrix X.

- 7.

- The integrated matrix T. After obtaining the direct norm matrix X, the integrated influence matrix T is obtained according to Equation (12) where I is the unit matrix.

- 8.

- Calculating the total value of each row and column adds up each row and column in the total impact relationship matrix (T) to get the sum of each column (D-value) and the sum of each row (R-value).

- 9.

- The cause and effect diagram is plotted as the sum of factor i influencing the other factors, incorporating both direct and indirect influences, and as the sum of factor j being influenced by the other factors.

4. Analysis

This section will proceed in a manner consistent with the approach outlined in Section 3, with the objective of identifying the key drivers and establishing the causal relationships between them.

4.1. Screening Key Drivers Through FDM

A review of the pertinent literature revealed that 12 experts consented to complete the questionnaire and excluded one anomaly. Given the relative novelty of the concept of Industry 5.0, particularly in an emerging economy such as China, the 12 experts permitted the inclusion of any other drivers that are deemed to enhance the Intelligent Logistics Industry 5.0. Ultimately, 11 more precise questionnaires were retrieved to ascertain the standard deviation σ of the most conservative perception value and the most optimistic perception value, as per Equation (1). Thereafter, the range of the left and right double standard deviation of 2σ centered on σ was determined, and the extreme values outside of the 2σ were excluded. The remaining data were then processed and classified into three dimensions: sustainability, people-centricity, and resilience.

Subsequently, the triangular fuzzy number of each factor questionnaire data was calculated according to Equations (2)–(4), to find out the minimum value of the most conservative cognitive value , the geometric mean, the maximum value , the minimum value of the most optimistic cognitive value , the geometric mean , the maximum value , the range of the geometric mean of the most optimistic cognitive value and the geometric mean of the most conservative cognitive value , the gray area of fuzzy relationship . Refer to Equations (5) and (6) for calculating the consensus degree value and, finally, sort through the obtained value , as shown in Table 4:

Table 4.

Consensus values for key drivers of Industry 5.0.

This study uses the FDM to set different thresholds in three different constructs after analyzing the following:

- Sustainability: the criterion is accepted if the G-value of the key factor of Industry 5.0 is ≥5.80. If not, it is deleted.Sustainability: the criterion is accepted if the G-value of the key factor of Industry 5.0 is ≥5.80. If not, it is deleted.

- People-centricity: the guideline is accepted if the G-value of the key factor of Industry 5.0 is ≥6.00. If not, it is deleted.

- Resilience: accept the guideline if the G-value of the key factor for Industry 5.0 is ≥5.90. If not, it is deleted.

Finally, the 26 factors are filtered out to 15 key drivers, and the results are shown in Table 5:

Table 5.

Screened drivers for enhancing Smart Logistics Industry 5.0.

In screening the key drivers, we used the FDM and made the following assumptions:

- The experts involved in the FDM had sufficient expertise and experience to provide valuable, reliable, and relatively objective opinions on the research questions, and 11 relatively accurate questionnaires were returned.

- The experts’ opinions in assessing the key drivers have a certain degree of vagueness and uncertainty, which can be expressed by the fuzzy delta number.

- According to the results of the FDM, we designed different thresholds for the three different constructs.

4.2. Analyzing Factor Importance Based on Grey-DEMATEL Methodology

- The second phase of the questionnaire is concerned with the interrelationships between the drivers of Industry 5.0 in the context of smart logistics. The integration of grey relational analysis (GRA) with decision-making trial and evaluation laboratory (DEMATEL) methods serves to enhance the realism, objectivity, and scientific rigor of the evaluation process. The Grey-DEMATEL method is employed for the analysis of the causal and logical relationships among the drivers of Industry 5.0 for enhancing smart logistics. The following steps are to be undertaken:

- Completion of the questionnaire to obtain the initial matrix. Based on the results of the FDM, the second-round questionnaire was designed and distributed to 32 experts in relevant fields (two general managers, four operations managers, four supply chain managers, four production managers, two industrial engineers, two design engineers, two environmental engineers, five senior professors in operations management, five professors in logistics management, and two corporate executives) for completion.

- The upper and lower grey numbers are normalized by Equations (7) and (8) where n is the number of experts. The original relationship matrix combined with Table 3 expert scoring language scale design corresponding to the interval grey number is transformed into a 15 × 15 grey number proof. As shown in Table 6 and Table 7:

Table 6. Lower bound average grayscale matrix.

Table 6. Lower bound average grayscale matrix. Table 7. Upper limit mean gray matrix.

Table 7. Upper limit mean gray matrix.

- 4.

- The total normalized clarity values are calculated using Equation (9). The clarity matrix Lx is obtained as shown in Table 8:

Table 8. Clarification matrix Lx.

Table 8. Clarification matrix Lx.

- 5.

- By utilizing Formulas (10) and (11), we sum each row and each column, and then select the rows and columns corresponding to the maximum total values to obtain the direct specification matrix Nx, as presented in Table 9.

Table 9. Direct specification matrix Nx.

Table 9. Direct specification matrix Nx.

- 6.

- The combined impact matrix T was obtained using Equation (12) and is shown in Table 10:

Table 10. Integrated impact matrix T.

Table 10. Integrated impact matrix T.

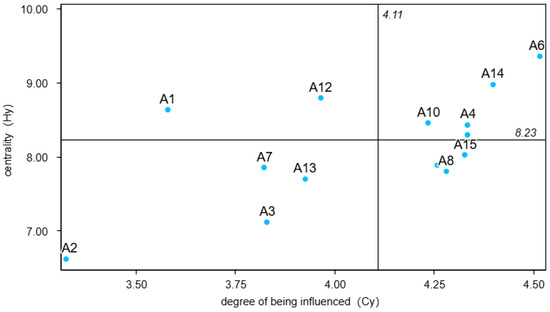

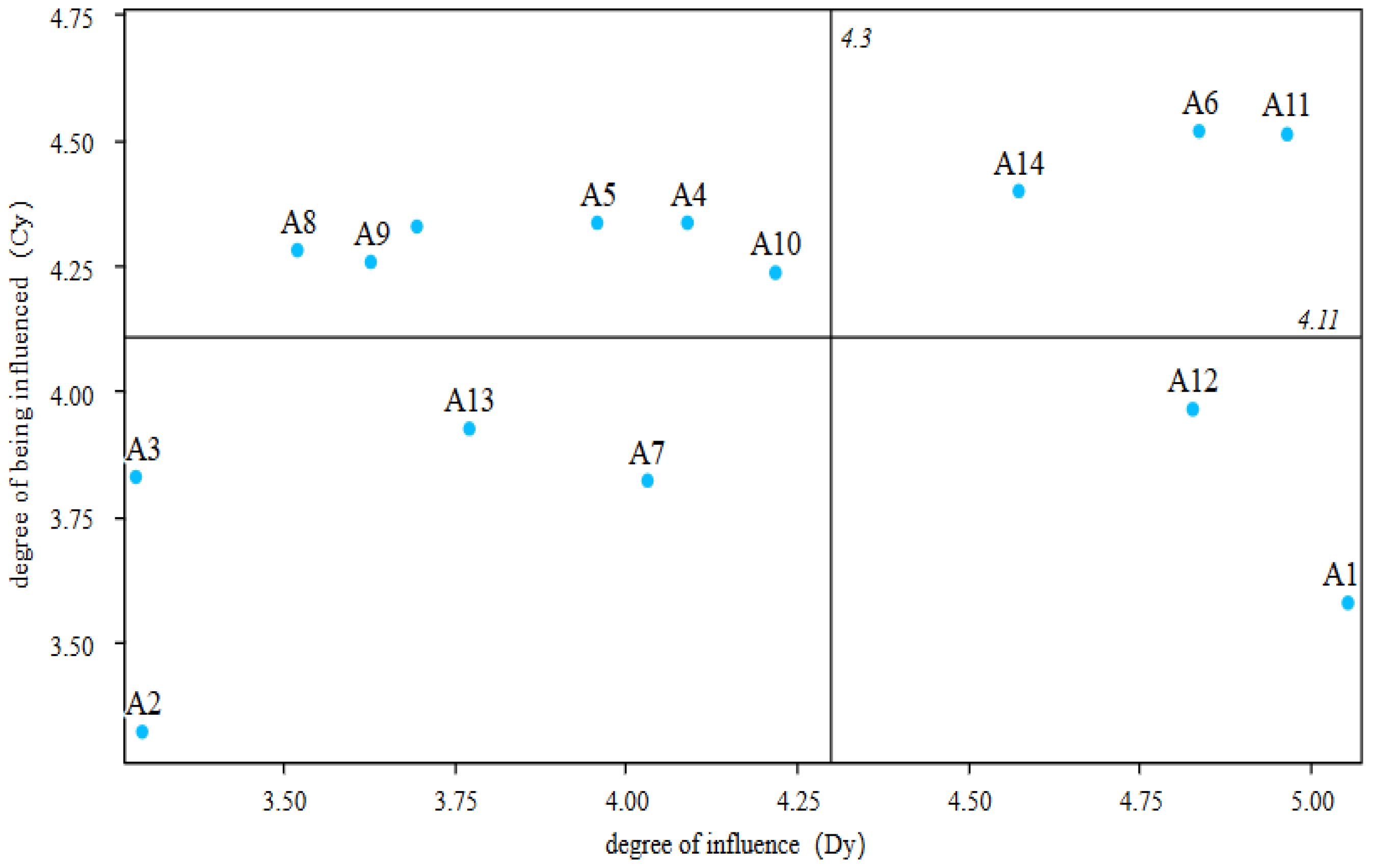

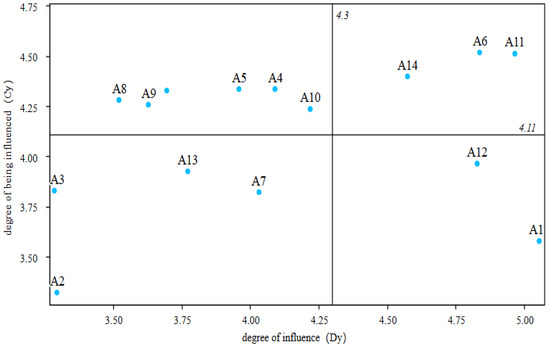

- Quadrant 1 represents factors with a high influence degree (Dy) and a high influenced degree (Cy), i.e., A6, A11, and A14.

- Quadrant 2 represents factors with a low influence degree (Dy) and a high influenced degree (Cy), i.e., A8, A9, A15, A5, A4, and A10.

- Quadrant 3 represents factors with a low influence degree (Dy) and a low influenced degree (Cy), i.e., A2, A3, A7, and A13.

- Quadrant 4 represents factors with a high influence degree (Dy) and a low influenced degree (Cy), i.e., A1 and A12 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Influence–influenced chart.

Figure 4. Influence–influenced chart.

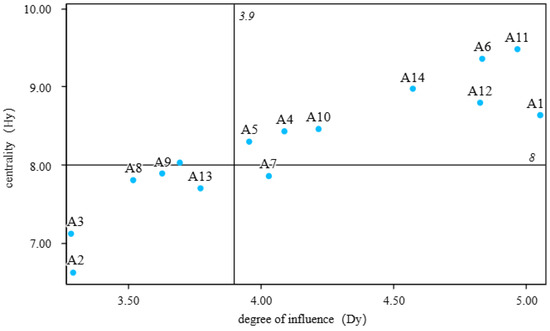

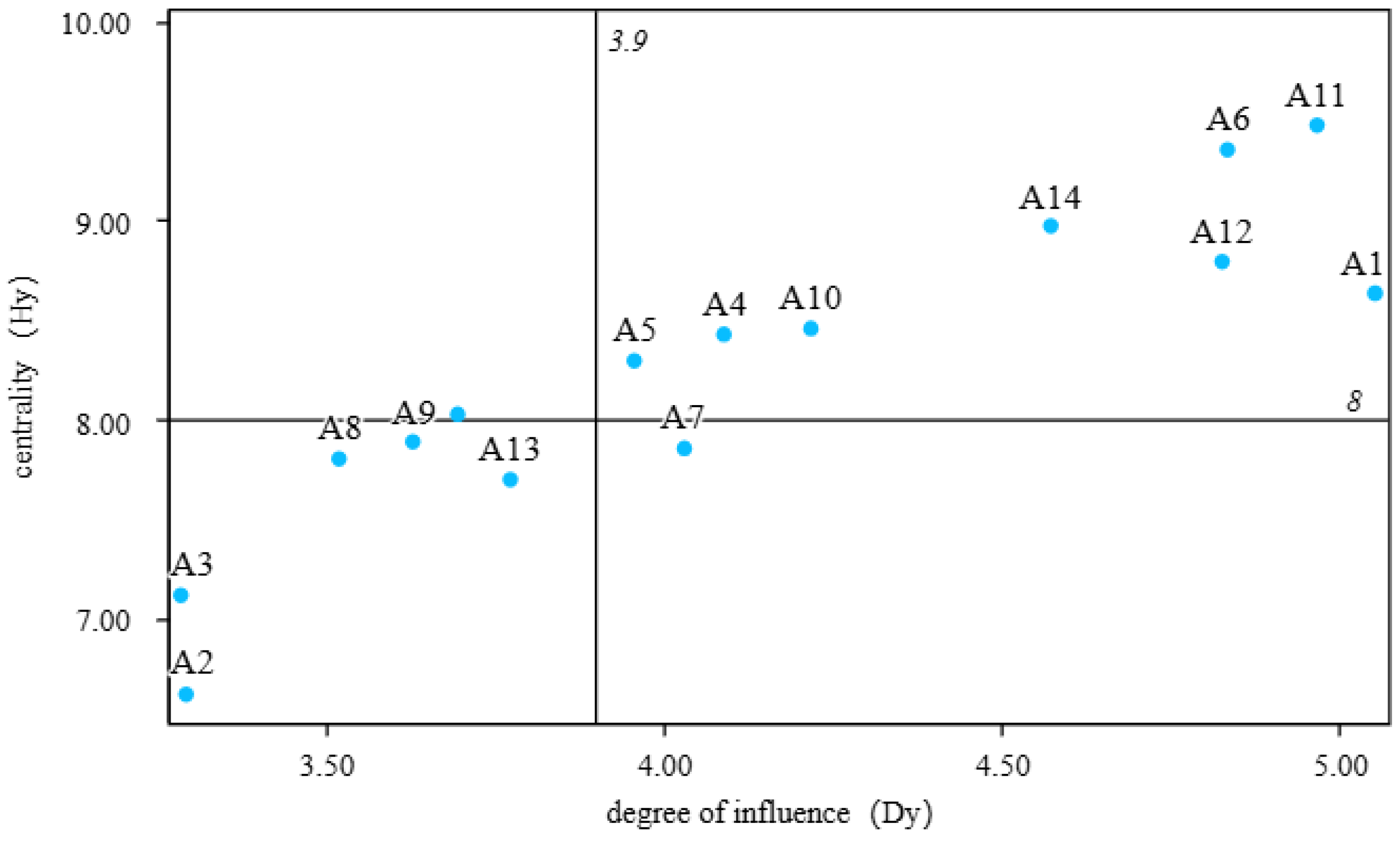

- Quadrant 1 indicates a high influence degree (Dy) and a high centrality degree (Hy), i.e., A15.

- Quadrant 2 indicates a low influence degree (Dy) and a high centrality degree (Hy), i.e., A5, A4, A10, A14, A12, A1, A6, and A11.

- Quadrant 3 indicates a low influence degree (Dy) and a low centrality degree (Hy), i.e., A2, A3, A9, A8, and A13.

- Quadrant 4 indicates a high influence degree (Dy) and a low centrality degree (Hy), i.e., A7.

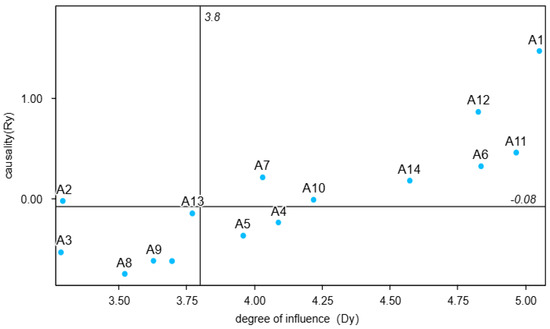

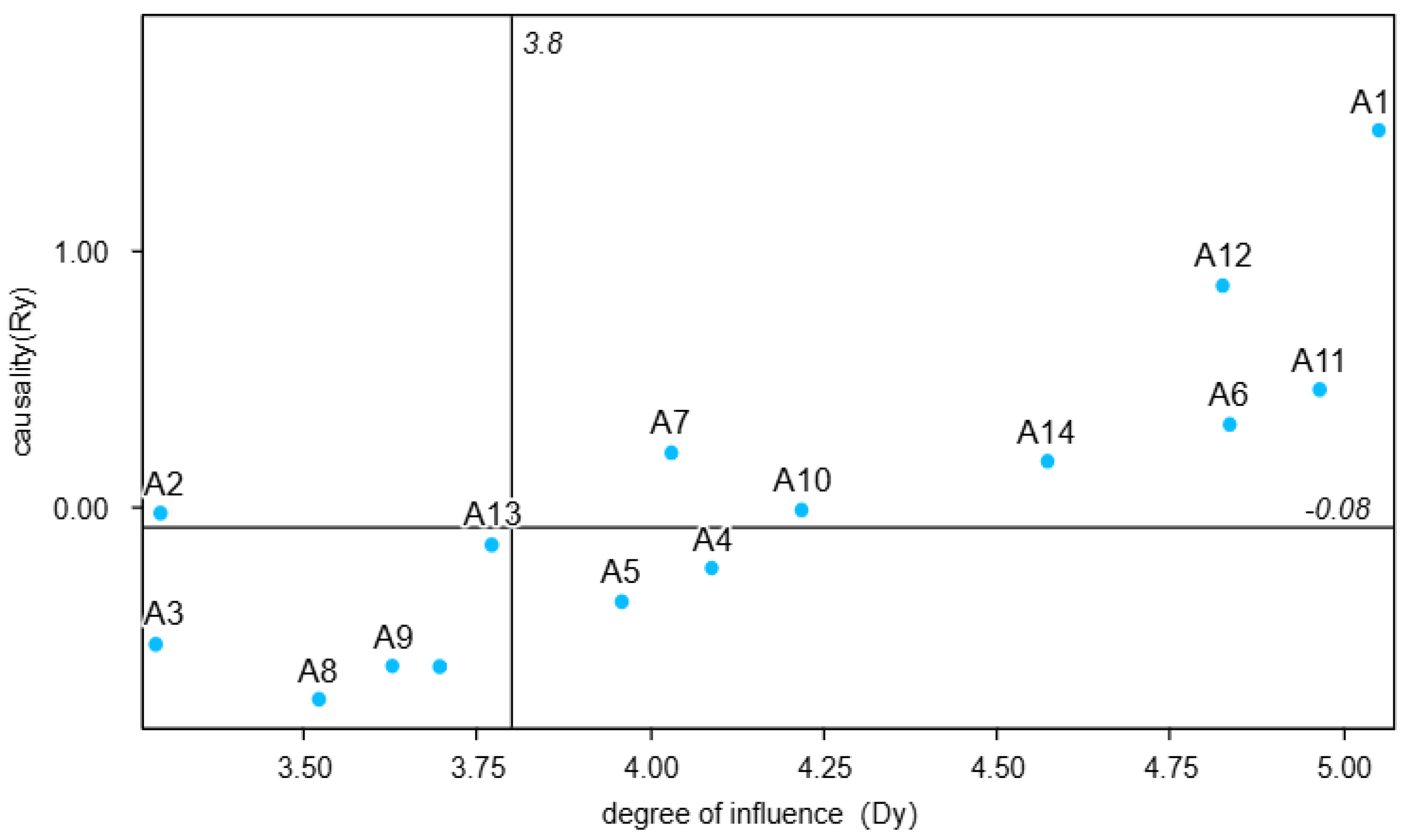

- Quadrant 1 indicates a high influence degree (Dy) and a high cause degree (Ry), i.e., A2.

- Quadrant 2 indicates a low influence degree (Dy)and a high cause degree (Ry), i.e., A7, A10, A14, A11, A6, A12, and A1.

- Quadrant 3 indicates a low influence degree (Dy) and a low cause degree (Ry), i.e., A3, A8, A9, A13, and A15.

- Quadrant 4 indicates a high influence degree (Dy) t and a low cause degree (Ry), i.e., A4 and A5.

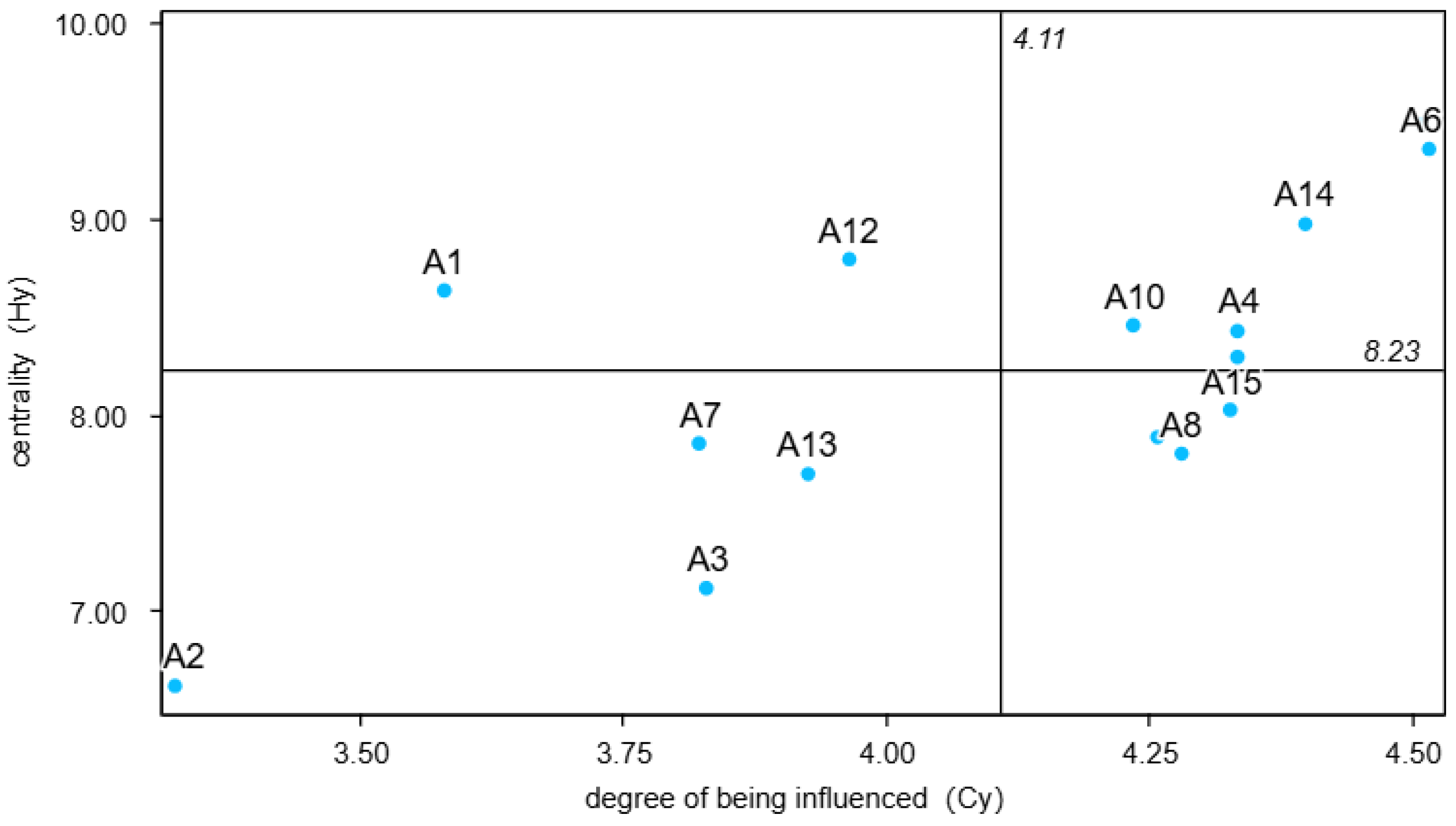

- Quadrant 1 indicates a high influenced degree (Cy) and a high centrality degree (Hy), i.e., A1 and A12.

- Quadrant 2 indicates a low influenced degree (Cy) and a high centrality degree (Hy), i.e., A4, A10, A14, A6, A5, and A11.

- Quadrant 3 indicates a low influenced degree (Cy) and a low centrality degree (Hy), i.e., A3, A2, A7, and A13.

- Quadrant 4 indicates a high influenced degree (Cy) and a low centrality degree (Hy), i.e., A8, A15, and A9.

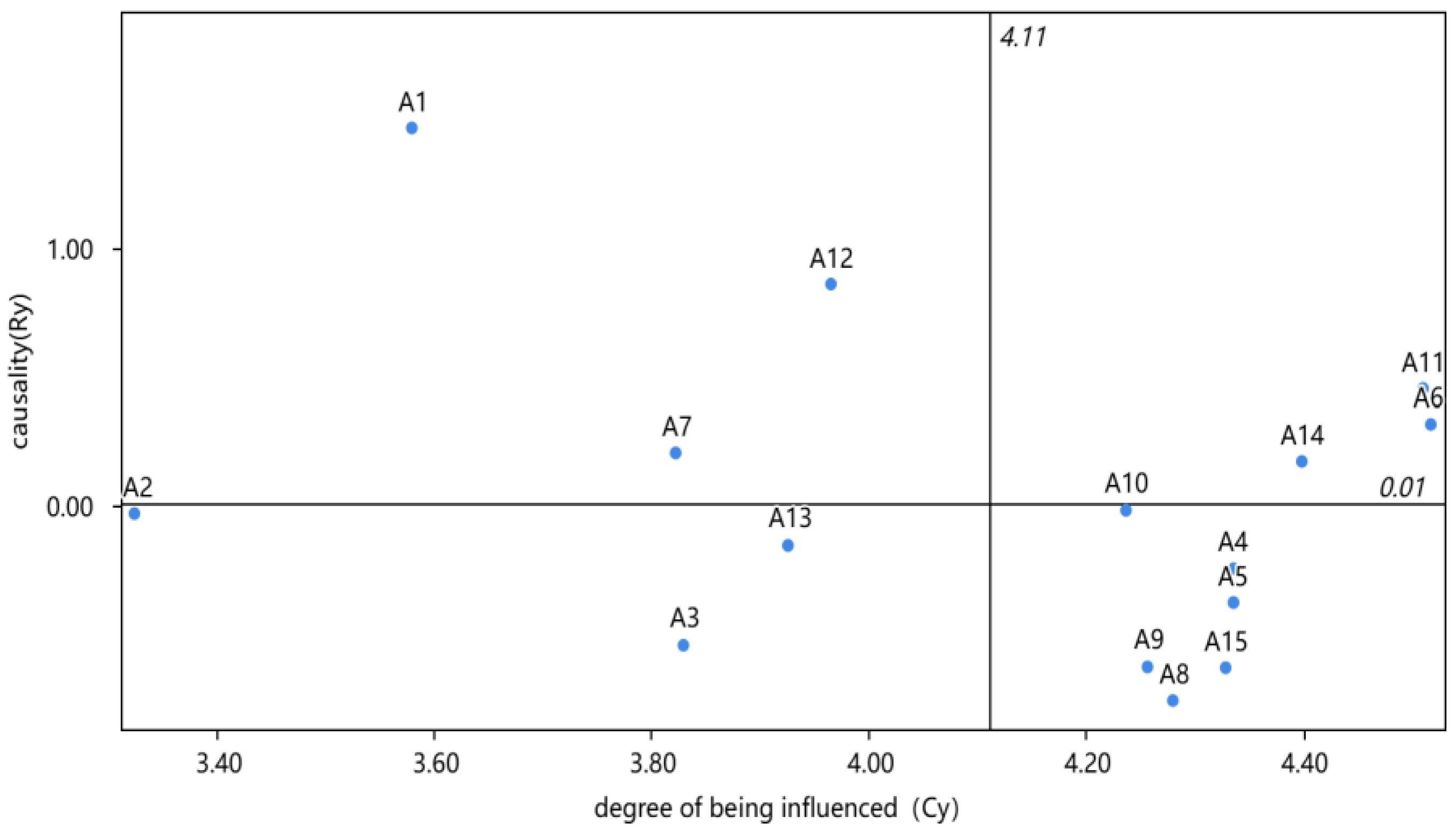

- Quadrant 1 indicates a high influenced degree (Cy) and a high cause degree (Ry), i.e., A1, A12, and A7.

- Quadrant 2 indicates a low influenced degree (Cy) and a low cause degree (Ry), i.e., A14, A6, and A11.

- Quadrant 3 indicates a low influenced degree (Cy) and a low cause degree (Ry) i.e., A2, A3, and A13.

- Quadrant 4 indicates a high influenced degree (Cy)and a low cause degree (Ry), i.e., A8, A15, A9, A4, A5, and A10.

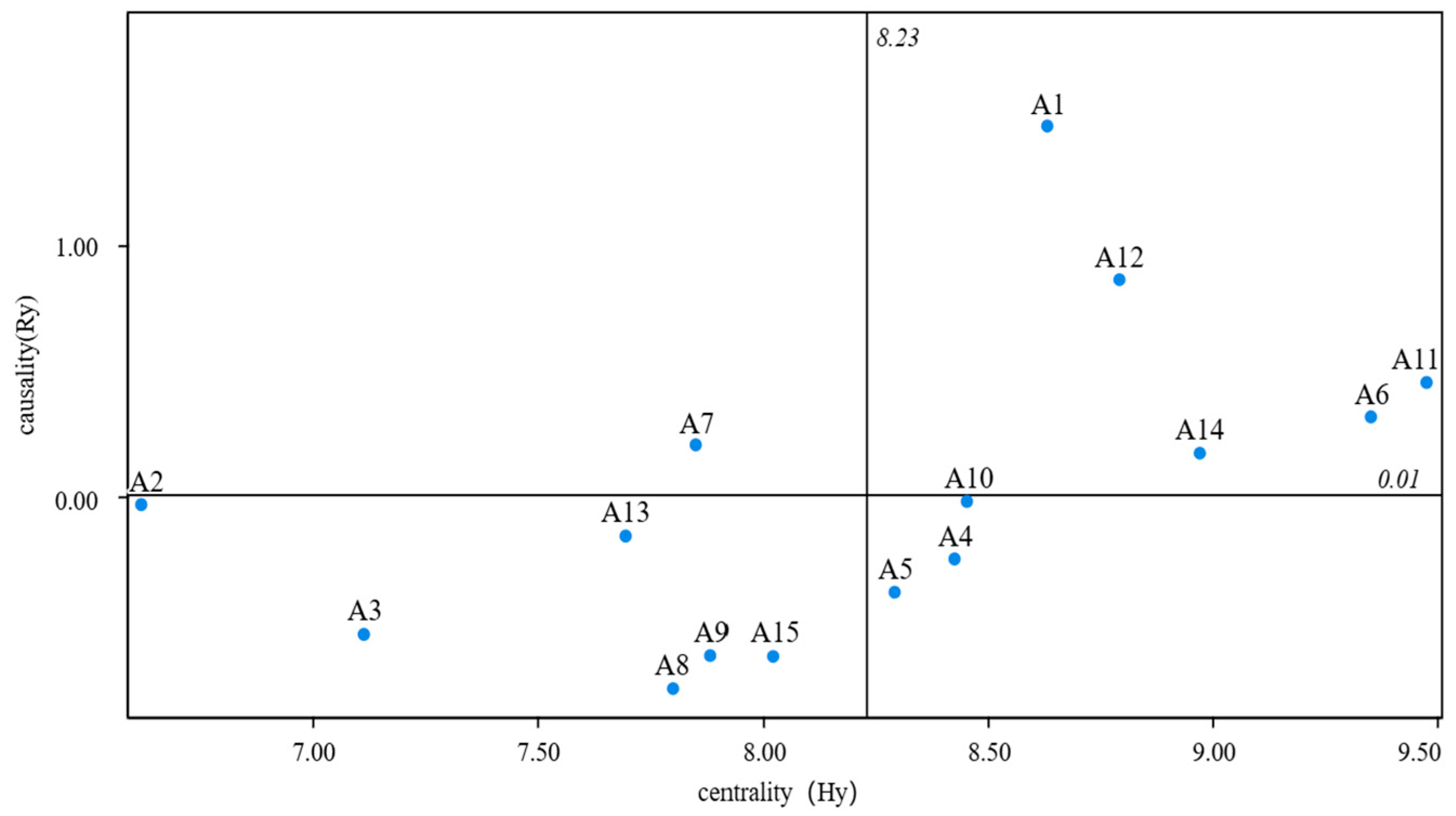

- Quadrant 1 indicates that both centrality and causality are engaged, i.e., the element is of high importance and is a causal factor.

- Quadrant 2 indicates low centrality and high cause degree, i.e., the element is of low importance and is a cause factor.

- The cause indicators are A1, A6, A7, A11, A12, and A14, with A1 having the greatest importance.

- Quadrant 3 indicates low centrality and high cause, i.e., the element is of low importance and is a result factor.

- Quadrant 4 indicates high centrality and low causality, i.e., the factor is of high importance and is an outcome factor.

The remaining nine are outcome indicators, namely, A2, A3, A4, A5, A8, A9, A10, A13. and A15.

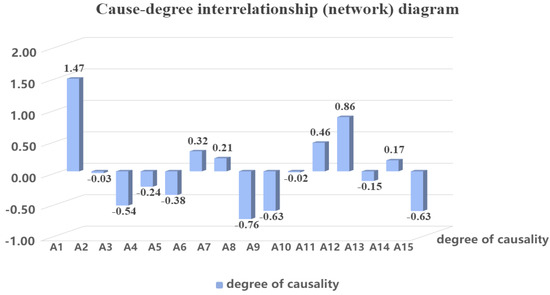

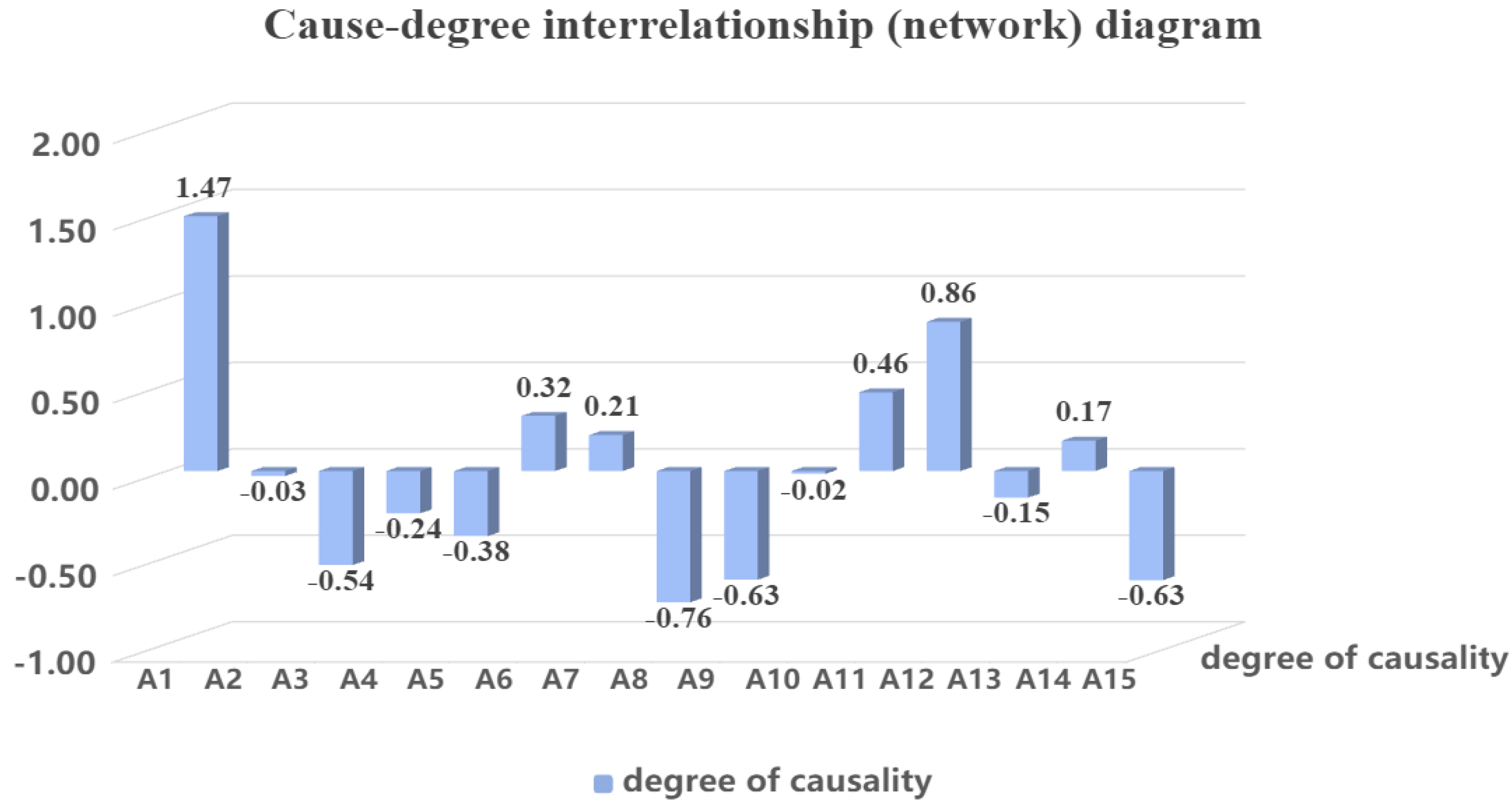

Figure 9 provides a clear delineation of the cause degree and center degree of each influencing factor. The most pertinent indicator for assessing the characteristics of the factors is the cause degree. Following the principle that the cause degree is greater than zero, all Industry 5.0 drivers for enhancing smart logistics are classified into six cause factors and nine result factors. Causal factors are typically the immediate drivers of smart logistics development, whereas consequential factors represent the degree of influence exerted by other factors. The centrality degree serves to illustrate the relative importance of each influencing factor, and the cause degree is used to quantify the influence of factors in the system and the degree to which they are influenced by other elements.

5. Discussion of Findings

This study aims to identify the Industry 5.0 drivers that enhance smart logistics in logistics enterprises of emerging economies and to analyze the causal relationships among these drivers. In the first stage of our analysis, we identified 15 key Industry 5.0 drivers and categorized them into 3 groups: sustainability, human-centricity, and resilience. Based on the R-C dataset values, we determined six causal factors: “Clear Government Policies and Active Support (A1)”, “Cultivation of Practical Logistics Skills (A6)”, “Worker Training and Knowledge Updates (A7)”, “Managerial Support Commitment and Effective Governance (A11)”, “Standardization and Infrastructure Development in Logistics (A12)”, and “Formulating Management Strategies to Enhance Resource Sharing (A14)”. These factors are detailed in Table 12. The upper and lower grey numbers are normalized by Equations (7) and (8) where n is the number of experts. The original relationship matrix combined with Table 3 expert scoring language scale design corresponding to the interval grey number is transformed into a 15 × 15 grey number proof, as shown in Table 6 and Table 7.

Therefore, managers should pay particular attention to the influence of these six factors. In the second stage of our analysis, we employed the Grey-DEMATEL method to explore the causal relationships among the 15 factors. The results presented in Table 11 allowed us to evaluate the influence degree, affected degree, centrality, and causality of these key drivers. In the following sections, we further discuss the importance and ranking of the six causal factors and nine effect factors.

In particular, “Clear Government Policies and Active Support (A1)” exerts the most significant influence on other drivers, indicating that this factor has a marked impact on other drivers. Changes in this factor can trigger or accelerate corresponding changes in other factors, making it a pivotal driver for the development of smart logistics. For logistics enterprises, clear government policies and active support, such as fiscal incentives, can encourage the digital transformation of logistics companies, thereby accelerating the formation of green and low-carbon supply chains and aiding in achieving sustainable development. This finding is supported by previous literature. For example, Elsanhoury et al. noted that clear policy directions and proactive support measures established by the government create an attractive investment environment and collaboration opportunities for logistics enterprises, effectively stimulating market vitality and promoting the rapid inflow of capital and the establishment of extensive partnerships [16]. Similarly, Romanova and Sirotin argued that clear government policies are crucial for the integrated development of economic, ecological, and social systems, ensuring the optimal functioning of operational systems [39].

Among the factors, “Standardization and Infrastructure Development in Logistics (A12)” ranks second in causality and fourth in influence. This indicates that A12 not only has significant driving or influencing capabilities on other factors but is also susceptible to changes in other factors. This highlights the critical role of infrastructure development in enabling logistics enterprises to leverage Industry 5.0 for the advancement of smart logistics. This finding is supported by Meng et al., who demonstrated that in the logistics industry, the use of technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT), big data, and sensors, along with infrastructure development, can enhance productivity and efficiency [40]. Notably, when infrastructure is well developed, it can reduce losses and waste during transportation, further improving the economic benefits of enterprises.

“Managerial Support Commitment and Effective Governance (A11)” ranks third in causality. Although it is not the most prominent in terms of causality, it has the highest centrality. This suggests that changes in A11 could potentially trigger changes in other factors within the system in the future. The potential impact of this factor renders its importance and analysis particularly crucial, as it could hold a vital role in the system’s evolution. Therefore, managers should closely monitor the trends of this driver. Industry 5.0 envisions intelligent and automated factories, enabling interactive and continuous monitoring responsibilities. Without managerial support and effective governance, this vision cannot be realized [20]. For logistics enterprises in emerging economies, the adoption of Industry 5.0 requires substantial support at both internal and external levels. This conclusion is supported by Raja Santhi and Muthuswamy whose study shows that with the help of modern digital and computational technologies, the integration of various intelligent machines and processes in industrial units creates an interconnected, intelligent, and agile ecosystem [11]. These advancements stem from effective governance and development by managers. By introducing new technologies and methods and optimizing logistics operations, logistics enterprises can continuously meet market demands and achieve sustainable development.

Among the causal factors, “Cultivation of Practical Logistics Skills (A6)” ranks fourth in causality and third in influence. This indicates that in the decision-making process, the comprehensive impact of this factor should be carefully considered and given appropriate attention. According to Chung, the lack of practical talent poses significant challenges to the construction of synergies among logistics enterprises, directly limiting the optimization and efficient utilization of resources on a broader scale, which, in turn, affects the operational efficiency and competitiveness of the entire logistics network [41]. Practical logistics skills talent has become a crucial driving force for technological innovation and application, and the application of these technologies has enhanced the intelligence and automation levels of logistics operations [42]. As logistics technology continues to evolve and be applied, the demand for talent in the logistics industry is also changing. Therefore, enterprises should strengthen the monitoring and management of this driver and its potential impacts while exploring the establishment of more robust innovation mechanisms. This is essential for enhancing the system resilience and reducing risks.

The fifth-ranked causal factor is “Worker Training and Knowledge Updates (A7)”, which is crucial for supporting Industry 5.0 and the development of smart logistics. As the logistics industry continues to evolve, enterprises must adapt to new market conditions and technological trends. Through worker training and knowledge updates, employees can better adapt to these changes. This finding is supported by Ikenga and van der Sijde whose study demonstrates that Industry 5.0, as a driver of smart logistics, will contribute to creating a sustainable, human-centric, and resilient business environment [43]. Therefore, Industry 5.0 requires emerging economies to make substantial investments in training and education programs to develop the high-skilled workforce needed to collaborate with machines and artificial intelligence. Such technological development and training will equip participants with the skills and information required to adopt cutting-edge and new technologies. These programs will provide professional training and vocational courses to help individuals meet the demands of Industry 5.0, enhance their technical capabilities, and adapt to the evolving work environment.

The last-ranked causal factor is “Formulating Management Strategies to Enhance Resource Sharing Levels (A14)”. Although this driver has a lower causality score, it does not diminish its importance. On the contrary, Mehdiabadi et al. emphasize the significance of management strategies [44]. By fostering resource sharing, businesses can expand their scale and coverage. The implementation of management strategies can enable logistics enterprises to optimize transport routes and delivery plans in real time using big data analytics and intelligent algorithms, thus reducing idle and waiting times. This helps companies achieve digital transformation and maintain alignment with industry developments, ultimately leading to higher economic, ecological, and social benefits.

The following section will address the outcome factors. As illustrated in Figure 3, the following factors have been identified as key drivers of success: “Green Energy Recycling (A2)”, “Seeking Ecological Innovations for Sustainable Development (A3)”, “Transforming Operations to Improve Supply Chain Efficiency (A4)”, “Comprehensive Assessment of Multiple Sustainability Indicators (A5)”, “Designing Intelligent and User-Friendly Workplaces (A8)”, “Understanding Employee Needs and Focusing on Employee Welfare (A9)”, “Emphasizing Technology That Adapts to the Needs and Diversity of industry Workers (A10)”, “Focusing on Production Flexibility and Agility (A13)”, and “Establishing Internal Organizational Culture and Communication (A15)”. These nine drivers are categorized as outcome factors, which are susceptible to causal factors and are highly interrelated. Among these, A4, A5, A10, and A15 have been identified as having high centrality, indicating that they are of significant importance. However, given their high level of influence and negative causality, it can be seen that these drivers are susceptible to change as a result of the causal factors. In light of the ongoing progression of society, logistics enterprises must strengthen their monitoring and management of this driver and its potential impact while simultaneously exploring the establishment of a more effective innovation mechanism. Furthermore, an examination of the direct relationship matrix N (Table 9) reveals that the most influential of the nine outcome factors are A1 and A11 of the cause factors. It is, therefore, incumbent upon managers to exercise control over the cause factors in advance to ensure that these outcome factors perform at a high level. It is important to note that, despite the relatively low influence, cause, and centrality indicators for the four drivers A2, A8, A9, and A13, these factors should not be overlooked. It is crucial for logistics firms in emerging economies to be aware of the potential threats posed by competitors in the market. Therefore, these firms need to invest more time and effort in these areas before their competitors do [36].

6. Concluding Remarks

This study delineates 15 drivers for logistics companies in emerging economies to enhance the Smart Logistics Industry 5.0 and elucidates the causal relationship between the aforementioned drivers. This study takes China, the world’s largest emerging economy, as its context. The data used in this study are drawn from the industry’s most authoritative experts and scholars, thereby ensuring the applicability and reliability of the research results. Firstly, 41 drivers were initially identified through a review of the literature and the collection of experts’ opinions. Subsequently, the 15 most representative drivers were selected from the numerous candidates using the FDM. Secondly, the causal relationships between these 15 key drivers were analyzed using the Grey-DEMATEL method.

The analysis reveals that the 15 identified key drivers not only function independently but also interact with each other. Additionally, Grey-DEMATEL is useful for determining causal relationships between drivers under conditions of ambiguity and uncertainty. The data for this study were collected from academic experts, with a particular focus on emerging economies such as China to ensure its applicability. Specifically, this study identified six causal factors: “Clear Government Policies and Active Support (A1)”, “Cultivation of Practical Logistics Skills (A6)”, “Worker Training and Knowledge Updates (A7)”, “Managerial Support Commitment and Effective Governance (A11)”, “Standardization and Infrastructure Development in Logistics (A12)”, and “Formulating Management Strategies to Enhance Resource Sharing (A14)”. Additionally, nine effect factors were identified: “Green Energy Recycling (A2)”, “Seeking Ecological Innovations for Sustainable Development (A3)”, “Transforming Operations to Improve Supply Chain Efficiency (A4)”, “Comprehensive Assessment of Multiple Sustainability Indicators (A5)”, “Designing Intelligent and User-Friendly Workplaces (A8)”, “Understanding Employee Needs and Focusing on Employee Welfare (A9)”, “Emphasizing Technology That Adapts to the Needs and Diversity of industry Workers (A10)”, “Focusing on Production Flexibility and Agility (A13)”, and “Establishing Internal Organizational Culture and Communication (A15)”.

A thorough examination of the principal motivating factors will assist logistics enterprises in allocating their limited capital and resources to the most crucial areas, thereby enhancing the probability of achieving success in the advent of Industry 5.0 for smart logistics. This study proffers the following recommendations for logistics enterprises in emerging economies: Firstly, the enactment of supportive government policies is of paramount importance, and thus, enterprise managers must be obliged to maintain a close watch on policy developments and to adapt their business strategies flexibly to ensure that they optimize the utilization of policy dividends, while ensuring legal compliance [24]. Secondly, to enhance the quality of service and competitiveness in the market, logistics enterprises in emerging economies must continuously cultivate practical logistics personnel with the requisite skills, which, in turn, will drive innovation and development in the industry. Finally, in the context of the alterations to the cost structure brought about by Industry 5.0, managers must exercise meticulous control over the costs associated with initial investment, equipment maintenance, and upgrades. This is to prevent deficits while simultaneously capitalizing on the potential for long-term cost reductions. It is also important to consider the potential for long-term cost reductions. From a macro perspective, logistics enterprises in emerging economies should adopt a people-oriented approach, prioritizing employee health and safety while integrating humans and machines. The comprehensive implementation of these strategies will provide a robust foundation for logistics enterprises in emerging economies to achieve intelligent transformation in the era of Industry 5.0.

The contributions of this study are as follows:

- In the context of emerging economies, there is a paucity of discussion in the existing literature regarding the investigation and definition of Industry 5.0 drivers for enhancing smart logistics. This study addresses this gap by integrating existing literature to identify the key drivers. This work assists managers in comprehending the causal relationships between these factors, thus enabling them to recognize the role of Industry 5.0 as a catalyst for the dissemination of smart logistics and its impact on the sustainable development of logistics enterprises. Moreover, it will assist logistics companies in leveraging Industry 5.0 to enhance their economic performance and contribute to societal benefits.

- The Grey-DEMATEL method used in this study is employed to determine the interrelationships among various factors in complex domains, particularly suitable for addressing decision-making problems with uncertainty and incomplete information. It also generates a centrality–causality diagram, which will help managers understand the impact of each driver, thereby facilitating the formulation of effective plans to promote sustainable development in the ecological, economic, and social dimensions for logistics enterprises in emerging economies.

- This study demonstrates that the principles of Industry 5.0 place an emphasis on sustainability, human-centricity, and resilience. These concepts complement and extend those of Industry 4.0, rather than simply continuing or replacing them. This clarification is beneficial for both academic and industrial contexts as it facilitates a more comprehensive understanding of the fundamental principles and future trajectory of Industry 5.0. From an industrial standpoint, the adoption of Industry 5.0 should be regarded as a strategic decision to enhance cost efficiency, reduce costs and energy consumption, and facilitate the rapid development and transformation of the logistics sector.

- The analysis presented in this study demonstrates that government support policies represent a pivotal factor within the causal group, exerting a pervasive influence across the full spectrum of drivers associated with the concept of smart logistics. The findings of this study provide managers with effective governance methods to improve performance and time management. Moreover, it is evident that the implementation of transparent governmental policies and the provision of adequate support are of paramount importance for the advancement of Industry 5.0, with the objective of conserving resources and fostering a sustainable culture within the domain of logistics enterprises. By establishing transparent and coherent policies, the government can facilitate the planning and development of logistics infrastructure, thereby accelerating the rapid growth of the modern logistics industry.

In conclusion, this study makes a notable contribution to theoretical, practical, and social aspects of knowledge although it also has some limitations. While the findings are applicable to logistics enterprises in emerging economies, it should be noted that the current development level of these enterprises is relatively low. Consequently, organizations must prioritize innovation and implementation to facilitate a transition from a resource-driven model to a platform-driven model in smart logistics systems, thereby enhancing their competitiveness in the domain of smart logistics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-H.H. and S.-J.C.; methodology, C.-H.H. and M.-Q.H.; software, S.-J.C. and Q.L.; validation, C.-H.H., S.-J.C., and M.-Q.H.; formal analysis, C.-H.H.; investigation, C.-H.H. and S.-J.C.; resources, C.-H.H.; data curation, S.-J.C.; writing-original draft preparation, S.-J.C. and Q.L.; writing—review and editing, C.-H.H. and S.-J.C.; visualization, C.-H.H. and M.-Q.H.; supervision, C.-H.H. and M.-Q.H.; project administration, C.-H.H. and M.-Q.H.; funding acquisition, C.-H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was supported by the Fujian Province Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 2024T020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

All of our participating authors are very much indebted to the Editor and anonymous referees who greatly helped improve this paper with their valuable comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Industry 5.0 drivers.

Table A1.

Industry 5.0 drivers.

| Grade | Industry 5.0 Drivers | Bibliography |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | Clear government policies and active support | Xu et al., (2021) [23]; Akundi et al., (2022) [13]; Grosse et al., (2023) [45]; Iyengar et al., (2022) [7]; Zhou et al., (2024) [32]; Mohamed, (2023) [46]; Raja Santhi and Muthuswamy, (2023) [11]; Ivanov, (2023) [47] |

| A2 | Green energy recycling | Carayannis and Morawska-Jancelewicz, (2022) [48]; Cimini et al., (2020) [34]; McFarlane et al., (2016) [49]; Patil et al., (2022) [30]; Rana, (2023) [50]; Bakator et al., (2024) [51] |

| A3 | Seeking ecological innovations for sustainable development | Xu et al., (2021) [23]; Zhou et al., (2024) [32]; Maddikunta et al., (2022) [20]; Mohamed, (2023) [46]; Ouyang et al., (2019) [4]; Patil et al., (2022) [30]; Romanova and Sirotin,(2024) [37]; Xingxia Wang et al., (2023) [52]; Akundi et al., (2022) [13]; Bakator et al., (2024) [51] |

| A4 | Transforming operations to improve supply chain efficiency | Carayannis and Morawska-Jancelewicz, (2022) [48]; Grosse et al., (2023) [45]; Iyengar et al., (2022) [7]; Maddikunta et al., (2022) [20]; Marinagi et al., (2023) [9]; Mohamed, (2023) [46]; Raja Santhi and Muthuswamy, (2023) [11]; Hsu et al., (2024) [31]; Golovianko et al., (2023) [1]; Hassoun et al., (2022) [53] |

| A5 | Comprehensive assessment of multiple sustainability indicators | Xu et al., (2021) [23]; Elsanhoury et al., (2022) [16]; Ouyang et al., (2019) [4]; Rana, (2023) [50]; Bakator et al., (2024) [51]; Akundi et al., (2022) [13]; Ljubo Vlacic et al., (2024) [42] |

| A6 | Cultivation of practical logistics skills | Akundi et al., (2022) [13]; Fu and Zhu, (2019) [54]; Grosse et al., (2023) [45]; Lagorio et al., (2023) [5]; Maddikunta et al., (2022) [20]; McFarlane et al., (2016) [49]; Zhou et al., (2024) [32]; Romanova and Sirotin, (2024) [37] |

| A7 | Worker training and knowledge updates | de Azambuja et al., (2023) [55]; Cimini et al., (2020) [34]; Iyengar et al., (2022) [7]; Zhou et al., (2024) [32]; Ouyang et al., (2019) [4]; Bakator et al., (2024) [51]; Ljubo Vlacic et al., (2024) [42]; Golovianko et al., (2023) [1]; Liu et al., (2022) [56] |

| A8 | Designing intelligent and user-friendly workplaces | Fu and Zhu, (2019) [54]; Maddikunta et al., (2022) [20]; Ouyang et al., (2019) [4]; Patil et al., (2022) [30]; Rana, (2023) [50]; Bakator et al., (2024) [51]; Romanova and Sirotin,(2024) [37]; Hassoun et al., (2022) [53] |

| A9 | Understanding employee needs and focusing on employee welfare | Aheleroff et al., (2022) [24]; Hariram et al., (2023) [18]; Lagorio et al., (2023) [5]; Marinagi et al., (2023) [9]; McFarlane et al., (2016) [49]; Raja Santhi and Muthuswamy, (2023) [11]; Ivanov, (2023) [47]; Ljubo Vlacic et al., (2024) [42]; Liu et al., (2022) [56] |

| A10 | Emphasizing technology that adapts to the needs and diversity of industry workers | de Azambuja et al., (2023) [55]; Fu and Zhu, (2019) [54]; Issaoui et al., (2022) [57]; Rana, (2023) [50]; Akundi et al., (2022) [13]; Hsu et al., (2024) [31]; Golovianko et al., (2023) [1]; Liu et al., (2022) [56]; Kang et al., (2024) [58] |

| A11 | Managerial support commitment and effective governance | Jefroy et al., (2022) [26]; Hariram et al., (2023) [18]; Iyengar et al., (2022) [7]; Mohamed, (2023) [46]; Raja Santhi and Muthuswamy, (2023) [11]; Bakator et al., (2024) [51]; Xingxia Wang et al., (2023) [52]; Akundi et al., (2022) [13] |

| A12 | Standardization and infrastructure development in logistics | Akundi et al., (2022) [13,35,54] Zhou et al., (2024) [32]; Maddikunta et al., (2022) [20]; Marinagi et al., (2023) [9]; McFarlane et al., (2016) [49]; Bakator et al., (2024) [51]; Hsu et al., (2024) [31]; Golovianko et al., (2023) [1] |

| A13 | Seeking ecological innovations for sustainable development | Grosse et al., (2023) [45]; Issaoui et al., (2022) [57]; Zhou et al., (2024) [32]; Mohamed, (2023) [46]; Ivanov, (2023) [47]; Hsu et al., (2024) [31]; Ding et al., (2021) [6]; Aheleroff et al., (2022) [24]; Liu et al., (2022) [56] |

| A14 | Formulating management strategies to enhance resource sharing | de Azambuja et al.; (2023) [55], Carayannis and Morawska-Jancelewicz, (2022) [48]; Cimini et al., (2020) [34]; Iyengar et al., (2022) [7]; Patil et al., (2022) [30]; Rana, (2023) [50]; Hsu et al., (2024) [31] |

| A15 | Establishing internal organizational culture and communication | Iyengar et al., (2022) [7]; Maddikunta et al., (2022) [20]; Ouyang et al., (2019) [4]; Raja Santhi and Muthuswamy, (2023) [11]; Rana, (2023) [50], Akundi et al., (2022) [13]; Javaid et al., (2022) [59]; Kang et al., (2024) [58] |

| A16 | Using analytical forecasting methods and making optimal decisions in response to market changes (big data techniques) | Jefroy et al., (2022) [26]; Grosse et al., (2023) [45]; Maddikunta et al., (2022) [20]; Ouyang et al., (2019) [4]; Ljubo Vlacic et al., (2024) [42]; Golovianko et al., (2023) [1] |

| A17 | Security during logistics information interaction | Elsanhoury et al., (2022) [16]; Rana, (2023) [50]; Romanova and Sirotin, (2024) [37]; Ljubo Vlacic et al., (2024) [42]; Javaid et al., (2022) [59]; Liu et al., (2022) [56] |

| A18 | Enhanced technology integration and governance (e.g., cloud computing to integrate supply chain personnel, risk prediction) | Aheleroff et al., (2022) [24]; Lagorio et al., (2023) [5]; Marinagi et al., (2023) [9]; Hsu et al., (2024) [31]; Liu et al., (2022) [56] |

| A19 | Analyzing the impact of technology on human work | Grosse et al., (2023) [45]; Zhou et al., (2024) [32]; Ouyang et al., (2019) [4]; Zhou et al., (2024) [32]; Romanova and Sirotin, (2024) [37]; Ding et al., (2021) [6] |

| A20 | Skill development and updating of workers’ knowledge | Akundi et al., (2022) [13]; Iyengar et al., (2022) [7]; Mohamed,(2023) [46]; Rana, (2023) [50]; Bakator et al., (2024) [51]; Romanova and Sirotin, (2024) [37]; Xingxia Wang et al., (2023) [52]; Ding et al., (2021) [6] |

| A21 | Considering the cognitive and physical load of older workers to improve work distribution in production and logistics systems | Jiménez Rios et al., (2024) [60]; Xu et al., (2021) [23]; Maddikunta et al., (2022) [20]; Ding et al., (2021) [6]; Liu et al., (2022) [56]; Hassoun et al., (2022) [53]; Kang et al., (2024) [58] |

| A22 | Manufacturing process and business refinement (reducing duplication and resource wastage) | Elsanhoury et al., (2022) [16]; Maddikunta et al., (2022) [20]; Raja Santhi and Muthuswamy, (2023) [11]; Bakator et al., (2024) [51] |

| A23 | Introduction of safer and more efficient robotic systems | Aheleroff et al., (2022) [24]; Issaoui et al., (2022) [57]; Marinagi et al., (2023) [9]; Zhou et al., (2024) [32]; Xingxia Wang et al., (2023) [52]; Javaid et al., (2022) [59] |

| A24 | Improving occupational health and safety | Carayannis and Morawska-Jancelewicz, (2022) [48]; Hariram et al., (2023) [18]; Mohamed, (2023) [46]; Zhao et al., (2023) [27]; Golovianko et al., (2023) [1] |

| A25 | Increased sales of services (development of other value-added businesses to improve corporate services) | Aheleroff et al., (2022) [24]; Fu and Zhu, (2019) [54]; Marinagi et al., (2023) [9]; Bakator et al., (2024) [51] |

| A26 | Improvement of firms’ own technological and innovation capabilities | de Azambuja et al., (2023) [55]; Maddikunta et al., (2022) [20]; Patil et al., (2022) [30]; Rana, (2023) [50]; Zhao et al., (2023) [27]; Aheleroff et al., (2022) [24] |

References

- Golovianko, M.; Terziyan, V.; Branytskyi, V.; Malyk, D. Industry 4.0 vs. Industry 5.0: Co-existence, Transition, or a Hybrid. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 217, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, P.; Minner, S.; Schiffer, M. Smart and sustainable city logistics: Design, consolidation, and regulation. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 307, 1071–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korczak, J.; Kijewska, K. Smart Logistics in the development of Smart Cities. Transp. Res. Procedia 2018, 39, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Q.; Zheng, J.; Wang, S. Investigation of the construction of intelligent logistics system from traditional logistics model based on wireless network technology. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2019, 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagorio, A.; Cimini, C.; Pinto, R.; Cavalieri, S. 5G in Logistics 4.0: Potential applications and challenges. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 217, 650–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Jin, M.; Li, S.; Feng, D. Smart logistics based on the internet of things technology: An overview. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2021, 24, 323–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, K.P.; Pe, E.Z.; Jalli, J.; Shashidhara, M.K.; Jain, V.K.; Vaish, A.; Vaishya, R. Industry 5.0 technology capabilities in Trauma and Orthopaedics. J. Orthop. 2022, 32, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Na, X.; Wang, D.; Dai, X.; Wang, F.-Y. Mobility 5.0: Smart Logistics and Transportation Services in Cyber-Physical-Social Systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 8, 3527–3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinagi, C.; Reklitis, P.; Trivellas, P.; Sakas, D. The Impact of Industry 4.0 Technologies on Key Performance Indicators for a Resilient Supply Chain 4.0. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanvand, B.; Mortazavi, S.B.; Mahabadi, H.A.; Ahmadi, O. Determining essential criteria for selection of risk assessment techniques in occupational health and safety: A hybrid framework of fuzzy Delphi method. Saf. Sci. 2023, 167, 106253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhi, A.R.; Muthuswamy, P. Industry 5.0 or industry 4.0S? Introduction to industry 4.0 and a peek into the prospective industry 5.0 technologies. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. (IJIDeM) 2023, 17, 947–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata, J.; Kayser, I. Industry 5.0—Past, Present, and Near Future. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 219, 778–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akundi, A.; Euresti, D.; Luna, S.; Ankobiah, W.; Lopes, A.; Edinbarough, I. State of Industry 5.0—Analysis and Identification of Current Research Trends. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2022, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, N. Intelligent logistics scheduling model and algorithm based on Internet of Things technology. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.; Sha, W.; Wang, B.; Zheng, P.; Zhuang, C.; Liu, Q.; Wuest, T.; Mourtzis, D.; Wang, L. Industry 5.0: Prospect and retrospect. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 65, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsanhoury, M.; Mäkelä, P.; Koljonen, J.; Valisuo, P.; Shamsuzzoha, A.; Mantere, T.; Elmusrati, M.; Kuusniemi, H. Precision Positioning for Smart Logistics Using Ultra-Wideband Technology-Based Indoor Navigation: A Review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 44413–44445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Sun, X. Uncertain remanufacturing reverse logistics network design in industry 5.0: Opportunities and challenges of digitalization. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariram, N.P.; Mekha, K.B.; Suganthan, V.; Sudhakar, K. Sustainalism: An Integrated Socio-Economic-Environmental Model to Address Sustainable Development and Sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, P.; Bessa, C.; Landeck, J.; Silva, C. Industry 5.0: The Arising of a Concept. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 217, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddikunta, P.K.R.; Pham, Q.-V.; Prabadevi, B.; Deepa, N.; Dev, K.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Ruby, R.; Liyanage, M. Industry 5.0: A survey on enabling technologies and potential applications. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2022, 26, 100257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffie, N.A.M.; Shukor, N.M.; Rasmani, K.A. Fuzzy delphi method: Issues and challenges. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Logistics, Informatics and Service Sciences (LISS), Sydney, Australia, 24–27 July 2016; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzu, A.C. Application of fuzzy DEMATEL approach in maritime transportation: A risk analysis of anchor loss. Ocean Eng. 2023, 273, 113786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Lu, Y.; Vogel-Heuser, B.; Wang, L. Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0—Inception, conception and perception. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 61, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aheleroff, S.; Huang, H.; Xu, X.; Zhong, R.Y. Toward sustainability and resilience with Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0. Front. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 2, 951643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardarelli, E.; Sabattini, L.; Secchi, C.; Fantuzzi, C. Multisensor data fusion for obstacle detection in automated factory logistics. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Computer Communication and Processing (ICCP), Cluj, Romania, 4–6 September 2014; pp. 221–226. [Google Scholar]

- Jefroy, N.; Azarian, M.; Yu, H. Moving from Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0: What Are the Implications for Smart Logistics? Logistics 2022, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Hong, J.; Lau, K.H. Impact of supply chain digitalization on supply chain resilience and performance: A multi-mediation model. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 259, 108817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, K.; Yalçın, G.C.; Simic, V.; Önden, I.; Edinsel, S.; Bacanin, N. A single-valued neutrosophic-based methodology for selecting warehouse management software in sustainable logistics systems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 129, 107626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro, F.; Nocera, S. Flexible-route integrated passenger–freight transport in rural areas. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pr. 2023, 169, 103604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, A.R.; Thakur, K.; Gandhi, K.; Savale, V.; Sayyed, N. A Review on Industry 5.0: The Techno-Social Revolution. Int. J. Mech. Eng. 2022, 7, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.-H.; Wu, J.-Z.; Zhang, T.-Y.; Chen, J.-Y. Deploying Industry 5.0 drivers to enhance sustainable supply chain risk resilience. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2024, 17, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Yu, K.; Xie, W.; Lyu, J.; Zheng, Z.; Zhou, S. Digital Twin-Enabled Smart Maritime Logistics Management in the Context of Industry 5.0. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 10920–10931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutfi, A.; Alrawad, M.; Alsyouf, A.; Almaiah, M.A.; Al-Khasawneh, A.L.; Alshira’H, A.F.; Alshirah, M.H.; Saad, M.; Ibrahim, N. Drivers and impact of big data analytic adoption in the retail industry: A quantitative investigation applying structural equation modeling. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradpour, N.; Pourahmad, A.; Ziari, K.; Hataminejad, H.; Sharifi, A. Downscaling urban resilience assessment: A spatiotemporal analysis of urban blocks using the fuzzy Delphi method and K-means clustering. Build. Environ. 2024, 263, 111898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimini, C.; Lagorio, A.; Romero, D.; Cavalieri, S.; Stahre, J. Smart Logistics and The Logistics Operator 4.0. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 10615–10620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.G. Design and Development of Intelligent Logistics Tracking System Based on Computer Algorithm. Int. J. Appl. Inf. Manag. 2023, 3, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, B.; Diaz-Madroñero, M.; Soares, A.L.; Poler, R. Enabling technologies to support supply chain logistics 5.0. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 43889–43906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, H.M.; Heng, P.P.; Illias, M.R.H.; Karrupayah, S.; Fadhli, M.A.; Hod, R. A qualitative exploration and a fuzzy delphi validation of high-risk scaffolding tasks and fatigue-related safety behavioural deviation among scaffolders. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanova, O.A.; Sirotin, D.V. From Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0: Problems and Opportunities for the Metal Industry Development in Russia. Steel Transl. 2024, 54, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Zou, Y.; Ji, C.; Zhai, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z. Data-driven electric vehicle usage and charging analysis of logistics vehicle in Shenzhen, China. Energy 2024, 307, 132720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.-H. Applications of smart technologies in logistics and transport: A review. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 153, 102455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlacic, L.; Huang, H.; Dotoli, M.; Wang, Y.; Ioannou, P.A.; Fan, L.; Wang, X.; Carli, R.; Lv, C.; Li, L.; et al. Automation 5.0: The Key to Systems Intelligence and Industry 5.0. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2024, 11, 1723–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikenga, G.U.; van der Sijde, P. Twenty-first century competencies; about competencies for industry 5.0 and the opportunities for emerging economies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdiabadi, A.; Shahabi, V.; Shamsinejad, S.; Amiri, M.; Spulbar, C.; Birau, R. Investigating Industry 5.0 and Its Impact on the Banking Industry: Requirements, Approaches and Communications. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosse, E.H.; Sgarbossa, F.; Berlin, C.; Neumann, W.P. Human-centric production and logistics system design and management: Transitioning from Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 7749–7759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M. Toward Smart Logistics: Hybrization of Intelligence Techniques of Machine Learning and Multi-Criteria Decision-Making in Logistics 5.0. Multicriteria Algorithms Appl. 2023, 1, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D. The Industry 5.0 framework: Viability-based integration of the resilience, sustainability, and human-centricity perspectives. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 61, 1683–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Morawska-Jancelewicz, J. The Futures of Europe: Society 5.0 and Industry 5.0 as Driving Forces of Future Universities. J. Knowl. Econ. 2022, 13, 3445–3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, D.; Giannikas, V.; Lu, W. Intelligent logistics: Involving the customer. Comput. Ind. 2016, 81, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S. Industry 5.0: Sustainable development in Bangladesh. Int. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2023, 8, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakator, M.; Ćoćkalo, D.; Makitan, V.; Stanisavljev, S.; Nikolić, M. The three pillars of tomorrow: How Marketing 5.0 builds on Industry 5.0 and impacts Society 5.0? Heliyon 2024, 10, e36543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Miao, Q.; Wang, F.-Y.; Zhao, A.; Deng, J.-L.; Li, L.; Na, X.; Vlacic, L. Steps Toward Industry 5.0: Building “6S” Parallel Industries with Cyber-Physical-Social Intelligence. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2023, 10, 1692–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassoun, A.; Prieto, M.A.; Carpena, M.; Bouzembrak, Y.; Marvin, H.J.; Pallarés, N.; Barba, F.J.; Bangar, S.P.; Chaudhary, V.; Ibrahim, S.; et al. Exploring the role of green and Industry 4.0 technologies in achieving sustainable development goals in food sectors. Food Res. Int. 2022, 162, 112068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Zhu, J. Operation Mechanisms for Intelligent Logistics System: A Blockchain Perspective. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 144202–144213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Azambuja, A.J.G.; Plesker, C.; Schützer, K.; Anderl, R.; Schleich, B.; Almeida, V.R. Artificial Intelligence-Based Cyber Security in the Context of Industry 4.0—A Survey. Electronics 2023, 12, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, J.; Shi, Y.; Lee, P.T.-W.; Liang, Y. Intelligent logistics transformation problems in efficient commodity distribution. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 163, 102735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issaoui, Y.; Khiat, A.; Haricha, K.; Bahnasse, A.; Ouajji, H. An Advanced System to Enhance and Optimize Delivery Operations in a Smart Logistics Environment. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 6175–6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Cui, X.; Zhou, Y.; Han, Y.; Nie, J.; Zhang, Y. Self-powered wireless automatic countering system based on triboelectric nanogenerator for smart logistics. Nano Energy 2024, 123, 109365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R.; Gonzalez, E.S. Understanding the adoption of Industry 4.0 technologies in improving environmental sustainability. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2022, 3, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, A.J.; Petrou, M.L.; Ramirez, R.; Plevris, V.; Nogal, M. Industry 5.0, towards an enhanced built cultural heritage conservation practice. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96, 110542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).