Abstract

The tuning of fractional-order proportional-integral-derivative (FOPID) controllers for automatic voltage regulator (AVR) systems presents a complex challenge, necessitating the solution of real-order integral and differential equations. This study introduces the Dumbo Octopus Algorithm (DOA), a novel metaheuristic inspired by machine learning with animal behaviors, as an innovative approach to address this issue. For the first time, the DOA is invented and employed to optimize FOPID parameters, and its performance is rigorously evaluated against 11 existing metaheuristic algorithms using 23 classical benchmark functions and CEC2019 test sets. The evaluation includes a comprehensive quantitative analysis and qualitative analysis. Statistical significance was assessed using the Friedman’s test, highlighting the superior performance of the DOA compared to competing algorithms. To further validate its effectiveness, the DOA was applied to the FOPID parameter tuning of an AVR system, demonstrating exceptional performance in practical engineering applications. The results indicate that the DOA outperforms other algorithms in terms of convergence accuracy, robustness, and practical problem-solving capability. This establishes the DOA as a superior and promising solution for complex optimization problems, offering significant advancements in the tuning of FOPID for AVR systems.

Keywords:

Dumbo Octopus Algorithm; fractional-order proportional-integral-derivative; automatic voltage regulators; quantitative analysis; statistical analysis MSC:

68W50

1. Introduction

In modern power systems, automatic voltage regulators (AVRs) are crucial for maintaining generator output voltage stability and overall system reliability [1]. The primary function of an AVR is to maintain the output voltage at a set level by adjusting the generator’s excitation current. When the system detects a deviation from the set voltage, the AVR swiftly adjusts the excitation current to correct it. Hence, designing a high-performance AVR controller is essential to improve the stability and response speed of power systems [2].

Traditional AVR systems typically utilize proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controllers for voltage regulation [3]. PID controllers are popular due to their simplicity, ease of implementation, and reliable performance. However, as power systems become more complex and dynamic, traditional PID controllers exhibit limitations in handling complex working conditions and nonlinear characteristics. Issues such as slow adjustment speed, overshooting, and oscillation arise, especially under wide load variations and fast dynamic responses [4]. To address these limitations, researchers have developed advanced control strategies to enhance AVR performance [5]. One promising approach is the fractional-order proportional-integral-derivative (FOPID) controller, which has garnered significant attention due to its superior performance in managing complex nonlinear systems. By incorporating fractional-order calculus, FOPID controllers can more flexibly describe system dynamics, offering better frequency and time-domain performance compared to traditional PID controllers [6]. This results in significant improvements in system stability, reduced overshoot, and enhanced response speed [7].

Through precise parameter tuning, the FOPID controller can significantly improve the stability and response speed of AVR systems, thereby enhancing the operating efficiency of the power system, reducing voltage fluctuations, and improving the power supply quality and reliability of the grid. In addition, FOPID controllers are particularly important in the power industry to reduce power equipment damage due to voltage fluctuations, extend equipment life, and reduce maintenance costs. In terms of renewable energy integration, such as wind and solar power generation, its intermittency and unpredictability put higher demands on the adaptability and stability of the grid, and the optimized FOPID controller helps to better integrate these energy sources and improve the energy efficiency and environmental friendliness of the entire grid. Especially in areas such as industrial automation and data centers where power supply stability and continuity are highly required, FOPID controllers with good performance ensure that production processes and data are safe from voltage fluctuations, thus guaranteeing the efficient and stable operation of the system.

However, tuning the parameters of FOPID controllers is complex, particularly for high-dimensional nonlinear systems. Traditional tuning methods struggle to achieve global optimization [8]. For FOPID controllers, optimal parameter tuning involves finding the best values for proportional gain (), integral gain (), differential gain (), integral order (), and differential order () to meet specific performance requirements [9]. To overcome this challenge, heuristic algorithms have been introduced. These algorithms do not depend on the model and do not require specific derivative or gradient information. Through a series of optimization strategies, they explore and identify optimal or near-optimal solutions. Heuristic algorithms are highly adaptable, use gradient-free mechanisms, and effectively avoid local optima, making them suitable for complex, nonlinear, and high-dimensional problems [10,11,12]. Integrating advanced fractional-order controllers with optimization algorithms can overcome traditional control method limitations, further improving the AVR system’s dynamic response and robustness. This integration offers substantial theoretical value and practical application prospects. Currently, developing an effective optimization algorithm for FOPID parameter tuning in AVR systems is a key research goal.

Recent years have seen the development of many swarm intelligence algorithms inspired by animal behaviors, such as Sand Cat Swarm Optimization (SCSO) [13], Tunicate Swarm Algorithm (TSA) [14], Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO) [15], Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) [16], and Beluga Whale Optimization (BWO) [17]. The no free lunch (NFL) theorem encourages the development of new or improved optimization methods for various problem subsets [18]. However, traditional heuristic algorithms often rely on empirical heuristic rules, and their optimization ability may be limited for complex and high-dimensional problems.

Therefore, the heuristic optimization algorithm assisted by machine learning came into being, and the combination of machine learning and heuristic algorithm has become an important way to solve various practical problems. In the process of heuristic optimization, machine learning technology is introduced to guide the search direction of the optimization algorithm, so as to select candidate solutions more intelligently and improve the search efficiency and convergence speed [19]. In complex engineering design problems, optimization algorithms can generate high-quality initial solutions through machine learning models, which can significantly reduce the convergence time of algorithms [20]. In addition, machine learning technology can also be applied to the parameter adjustment and adaptive control of optimization algorithms. Researchers can automatically adjust the parameter settings of the optimization algorithm by using historical data and experience, making the algorithm more robust and efficient on different problems and data sets [21].

Inspired by these theorems, this paper introduces a new heuristic algorithm, the Dumbo Octopus Algorithm (DOA), based on the Dumbo Octopus’s prey-catching behavior. The DOA is proposed for the first time and shows promise in optimizing the FOPID parameters, significantly improving performance with high-quality solutions and fast convergence. Distinct from existing heuristic methods, the DOA has unique characteristics. Firstly, inspired by the predation process of the Dumbo Octopus, this paper divides its behavior into stages such as risk judgment, capture, seduction, scare, and escape. These unique natural behaviors provide a novel perspective for the design of the DOA, enabling it to dynamically balance exploration and exploitation in the search and optimization process. The DOA simulates the behavior of the Dumbo Octopus in assessing risks in unknown areas by random exploration and dynamic neighborhood adjustment. The DOA uses the dynamic switching probability factor to model the catching behavior of the Dumbo Octopus. This mapping allows the DOA to flexibly switch between exploration and exploitation to find better solutions. In the seduction stage, the DOA uses the Q-learning strategy to simulate the behavior of the Dumbo Octopus using luminous organs to lure prey. During the scare and escape phases, the DOA uses improved mutation strategies to simulate the escape behavior of octopuses in the face of threats, and these maps enable the DOA to efficiently search for and optimize solutions in local exploitation. Secondly, the DOA is unique in that it combines the Q-learning strategy in machine learning with traditional heuristic algorithms. In the process of local search, Q-Learning can switch the exploitation direction of individuals through the intelligent decision-making mechanism, thus effectively improving the convergence speed and accuracy of the algorithm and further highlighting the innovation of the DOA. Thirdly, the DOA adopts a multi-stage evolution mechanism, which differs from existing algorithms mainly in terms of the diversity and adaptability of its behavioral stages. In the global exploration stage, the DOA can switch different search strategies according to the risk environment, while in the local exploitation stage, the DOA uses seduction and escape behavior to ensure local exploitation while maintaining a certain global exploration ability to avoid the premature convergence of the algorithm to the local optimal solution. This multi-stage evolutionary process enables the DOA to dynamically adjust its search strategy according to the complexity of the problem, balancing exploration and exploitation, and ensuring better search efficiency and convergence performance in high-dimensional, non-linear problems. Finally, due to its simple structure and strong adaptability, the DOA can provide more competitive performance than other algorithms when solving the optimization problems of FOPID parameter tuning in AVR systems.

To evaluate the DOA’s performance, this paper compares it with 11 competing algorithms, including the Sand Cat Swarm Optimization (SCSO), Tunicate Swarm Algorithm (TSA), Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO), Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO), Beluga Whale Optimization (BWO), Ant Lion Optimizer (ALO) [22], Aquila Optimizer (AO) [23], Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [24], Sine Cosine Algorithm (SCA) [25], Slime Mould Algorithm (SMA) [26], and Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) [27] as competing algorithms. The evaluation uses 23 standard benchmark functions, CEC2017 and CEC2019 test suites, and includes quantitative analysis, qualitative analysis, parameter sensitivity analysis, and statistical tests. Additionally, the DOA’s superiority in FOPID parameter tuning for AVR systems is verified through simulation experiments comparing its performance with other optimization algorithms.

The key features and contributions of this work are as follows.

- Introduction of DOA: A novel metaheuristic algorithm, named the Dumbo Octopus Algorithm, is introduced. This algorithm mimics the risk judgment, capture, seduction, scare, and escape behaviors of the Dumbo Octopus.

- Effective Evolution Mechanism: The DOA incorporates three evolutionary mechanisms that enhance information exchange among individuals in the population, reduce the likelihood of premature convergence, balance global exploration and local exploitation, and significantly accelerate algorithm convergence.

- Machine learn-assisted DOA: In the local stage of the algorithm, the Q-Learning strategy of reinforcement learning is combined to switch the exploration mechanism, increase the information interaction of different individuals, and avoid falling into local extreme values.

- Benchmark Performance: The DOA demonstrates superior problem-solving ability, faster convergence speed, and higher convergence accuracy compared to 11 well-known metaheuristic algorithms across 23 classic benchmark functions and CEC2019 benchmark functions.

- Application in AVR Systems: This paper proposes a method for tuning the parameters of a fractional-order proportional-integral-derivative (FOPID) controller for automatic voltage regulator (AVR) systems using the DOA. Simulation results indicate that this method provides good stability and time-domain performance.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the principles of FOPID parameter tuning for AVR systems using heuristic optimization algorithms. Section 3 describes the inspiration and mathematical model underlying the proposed DOA. Section 4 discusses the experimental results and analyses of the DOA and 11 competing algorithms based on three sets of benchmark functions. Section 5 examines the advantages of the DOA algorithm in tuning FOPID parameters for AVR systems. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the main conclusions, limitations, and prospects.

2. Background Theory

This section briefly presents the well-known fractional-order PID (FOPID) controller, introduces a model of the automatic voltage regulator (AVR) system and finally explains briefly, heuristic algorithm-based FOPID parameter tuning for an AVR system.

2.1. FOPID Controller

Fractional calculus [28] is a branch of mathematics that deals with differential and integral functions of a non-integer order. The general expression of fractional calculus is as follows:

where represents the -order derivative with respect to , represents the -order integral in , is the fractional differential integral operator, and are the lower and upper limits, respectively, and is the order of the fractional differential integral, and in general, it can be either real or complex. In reference [29], fractional calculus has three common definitions. In this paper, the Riemann–Liouville definition shown in Equation (2) is used, and with the help of the FOMCON toolbox [30],

where , is an integer, is a real number, represents the -order derivative with respect to , and represents the gamma function.

From a control engineering perspective, fractional calculus can be applied to system modeling [31] or controller design [32]. The general transfer function [33] of the FOPID controller is as follows:

where , , , , and are proportional gain, integral gain, differential gain, integral order and differential order, respectively.

2.2. The Theory of Parameter Tuning of AVR System Based on Heuristic Algorithm

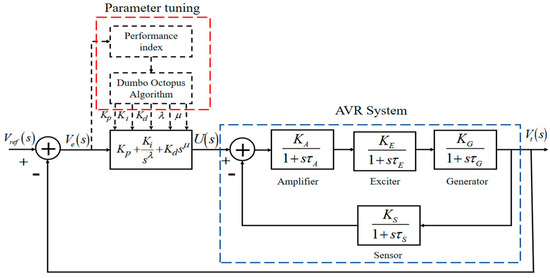

An automatic voltage regulator (AVR) is a control device primarily used to maintain the output voltage stability of a generator, ensuring reliable operation of a power system. With the increasing demand for electricity and the growing complexity of power systems, the performance and stability of AVR systems are critical. The AVR system comprises four main components: amplifier, exciter, generator, and sensor [34]. The principle of FOPID parameter tuning for the AVR system using a heuristic algorithm is to minimize the objective function by employing the optimization algorithm’s updating mechanism, thereby identifying the optimal decision variable from all possible solutions. The optimization problem in this paper is an unconstrained problem, and the objective function is non-differentiable. The FOPID parameter tuning process for the AVR system using a heuristic algorithm is illustrated in Figure 1. In the figure, is the expected signal of the system, is the actual output of the system, is the system error signal, which is the input signal of the FOPID controller, is the output signal of the controller, and , , , , and are the proportional coefficient, integral coefficient, differential coefficient, integral order and differential order of FOPID, respectively. Each component is represented as a first-order system with gain and time constant set to , respectively. Due to its excellent tracking response performance and robust anti-interference capability, the ITAE criterion results in minimal transient response oscillation in control systems and offers good parameter selectivity [35]. Therefore, this paper selected the ITAE performance evaluation criterion for subsequent experiments.

Figure 1.

FOPID parameter tuning of AVR system based on heuristic algorithm.

The optimization goal of this paper is to use the optimization strategy of the DOA to minimize the error index, ITAE, thereby finding the optimal parameter combination of the FOPID controller to improve the performance of the AVR system. In each iteration, the DOA evaluates the error index for the current combination of parameters and adjusts the search direction based on the evaluation results. When a certain number of iterations is satisfied or a predetermined ITAE is reached, the DOA terminates, and the optimal or near-optimal solution set of FOPID controller parameters is obtained. The mathematical model of this optimization problem can be represented as follows.

- Consider: ,

- Objective function: ,

- Controlled plant: ,

- Variables: .

In recent decades, the increasing dimensionality and complexity of problems have brought advanced control systems based on heuristic algorithms into focus. Oziablo et al. designed a method to optimize two types of fractional-variable-order PID (FVOPID) digital controllers for the automatic voltage regulator (AVR) system using the yellow saddle goatfish algorithm (YSGA) with a new fitness function [36]. Sony et al. used the Rao algorithm to optimize the AGC of a sample two-region interconnected multi-source power system with a FOPID controller, combining the integral square error (ISE) criterion with output variables; however, accuracy remained relatively low [37]. Lee proposed an improved electromagnetic-like algorithm (IEMGE) to adjust the parameters of the FOPID controller, achieving good performance [38], but its performance was significantly inadequate compared to many new algorithms [39,40,41]. Tumari et al. introduced a novel tuning tool tailored to the AVR system by utilizing the marine predators algorithm (MPA) [42]. Although the results were superior to those of most algorithms, the global exploration and local exploitation capabilities for some complex problems were not outstanding, failing to meet practical engineering requirements. To enhance the dynamic response and stability of the FOPID controller, the literature proposed a tuning method based on salp-swarm optimization [43]. Despite its robustness, this method is only applicable to a few controlled objects. The design of a FOPID controller based on the sine-cosine algorithm is discussed in the literature [44], which improves the FOPID controller’s performance, but issues such as slow convergence speed, low convergence accuracy, and the possibility of falling into local optima persist. Demirören et al. proposed an improved version of the artificial electric field algorithm, named opposition-based AEF, for the first time ever to tune a FOPID controller used in a magnetic ball suspension system [45]. In addition, many people have conducted a lot of research on fractional PID parameter tuning in AVR systems [34,46,47].

Although the aforementioned systems perform well, they still face challenges such as slow convergence speed, low convergence accuracy, and susceptibility to local optima. Additionally, there is a need to improve global exploration and local exploitation capabilities to meet the demands of some engineering problems.

3. Dumbo Octopus Algorithm

This section starts with the motivation for the Dumbo Octopus Algorithm (DOA) and then describes the mathematical model for this novel algorithm.

3.1. Inspiration

The Dumbo Octopus, part of the Opisthoteuthidae family in the Octopoda order, is a distinctive deep-sea mollusc. Found in locations such as New Guinea, Algu Beach, the Canary Islands, the Azores, Gascony Bay, Singesbice Deep, and the South China Sea, this species thrives in deep waters and has a lifespan of 3 to 5 years. Nicknamed the “Dumbo Octopus” due to its resemblance to Disney’s Dumbo, it features semigelatinous, smooth skin, two distinctive ear-like fins, and an elongated nose and is capable of changing body color. Adapted to deep-sea environments, Dumbo Octopuses possess advanced eyes and a unique U- or V-shaped cartilaginous shell, contributing to their captivating presence in ocean depths.

The Dumbo Octopus uses its large ear-like fins to maintain balance and navigate in the dark sea, typically covering distances of more than a mile. Unlike shallow-water octopuses that use jet propulsion, the Dumbo Octopus swims by flapping its ear-shaped fins or using its interbrachial membrane, resembling flight underwater. They typically dwell on the seabed, capturing crustaceans, polychaetes, and cephalopods as prey. When seizing small crustaceans, they leverage their morphological advantages, strategically selecting feeding locations, assessing food quality, and evaluating foraging risks. Upon detecting prey, the octopus promptly captures it, ensnaring it with a mucous web. When threatened, they may expand their interbrachial membrane to deter predators or roll their arm suckers outward, covering the mantle with webbing while displaying luminescent organs to repel unwanted guests.

The Dumbo Octopus’s behavior and environment maximize its underwater living space and food sources, inspiring algorithm research. The proposed Dumbo Octopus algorithm in this work simulates their prey-catching process, including risk judgment, capture, seduction, scare, and escape behaviors. The different stages of the Dumbo Octopus catching prey are described as follows:

- Risk Judgment Behavior

- ○

- Unknown Area Judgment: Dumbo Octopuses use their fins or interbrachial membranes to swim and explore deep-sea fields, roughly locating prey while assessing the risk and food abundance of foraging sites.

- ○

- Known Area Judgment: In familiar environments, they enhance their search strategy based on experience and learning to increase foraging efficiency.

- Capture Behavior

- ○

- Large-Scale Hunting: In identified foraging areas, Dumbo Octopuses use their developed vision to search for prey such as polychaetes and crustaceans, hunting them across the area.

- ○

- Small Trapping: They wander on rock surfaces and slowly swim with curled legs to obtain food.

- Seduction Behavior: Dumbo Octopuses use luminescent devices instead of suction cups to lure prey. Observing prey characteristics, they choose the most advantageous food types and trap them with a slime net produced by their bodies.

- Scare and Escape Behavior: When encountering predators like tuna and sharks while feeding, Dumbo Octopuses reveal all their luminescent organs to scare and drive away threats and then contract their interbrachial membranes to quickly escape.

3.2. Mathematical Model of the DOA

The Dumbo Octopus Algorithm (DOA) is inspired by the prey-catching process of Dumbo Octopuses, involving stages of risk judgment, capture, seduction, scare, and escape. These stages are analogized to different phases of the algorithm to balance exploration and exploitation effectively. Based on the hunting characteristics of the Dumbo Octopus, the proposed DOA is structured into four main stages, each mirroring specific behaviors observed in the octopus’s hunting strategy.

- i.

- Initialization Stage:

- Early in the algorithm, the DOA models the risk judgment behavior of the Dumbo octopus according to whether the random constant is greater than 0.1, which enables the algorithm to flexibly switch between exploring unknown and known fields.

- When , the DOA performs risk judgments in the unknown domain, expanding search trajectories across the entire search space bounded by upper () and lower () limits to ensure thorough exploration and ergodicity.

- When , the DOA updates positions based on the individual’s position vector and those of two randomly selected individuals, enhancing global exploration via random difference steps.

- ii.

- Capture Stage (Balanced Exploration and Exploitation):

- In the middle phase of DOA, the capture stage is simulated based on a dynamic switching probability factor, .

- This factor regulates the transition between global exploration and local exploitation phases, optimizing the algorithm’s ability to explore diverse solution spaces while exploiting promising regions.

- iii.

- Seduction, Scare, and Escape Stage (Local Exploitation):

- Towards the later stages of the DOA, the algorithm transitions between seduction (luring prey), scare (evading threats), and escape behaviors.

- This phase evolution is governed by the current iteration number relative to the maximum iteration number , ensuring the algorithm’s adaptation and avoidance of premature convergence to local optima.

By incorporating these stages inspired by the Dumbo Octopus’s adaptive hunting behaviors, the DOA aims to optimize search processes effectively, balancing between global exploration and local exploitation to enhance solution quality and algorithmic robustness.

3.2.1. Initialization

To reflect the characteristics of swarm intelligence, a population of individuals, including Dumbo Octopus individuals, is defined in the initialization stage of the algorithm. Each individual in this multidimensional optimization problem is an matrix. Each row represents a solution to the problem. In a D-dimensional space with individuals, the position of the individual can be defined as , and each variable must be located between the upper and lower bounds. Thus, the position of each individual is represented in the matrix as

where is the initial location of the population, and is the population number. is a characteristic of the optimization problem and is also known as the dimension. is the position of the individual in the dimension, whose value is randomly generated between the upper and lower bounds of the given problem, and its formula is as follows:

where and are the upper and lower bounds of the search domain, respectively, and where and . denotes a random value between 0 and 1.

The position vector of each individual is substituted into a predefined fitness function to evaluate its fitness, and the obtained fitness value is stored as

where Equation (10) describes the quality of the solution vector. The lower the fitness values are, the higher the quality of the solution vector.

3.2.2. Risk Judgment Phase (Exploration)

Risk judgment behavior in the Dumbo Octopus can be categorized into unknown region judgment and known region judgment. When in an unknown region (), the Dumbo Octopus uses its fins to hit the water or contracts its interbrachial membrane like a jellyfish, swimming randomly to extensively explore, evaluate, and determine the search space. Specifically, the Dumbo Octopus aims to gather as much useful information as possible within the upper and lower bounds of the exploration space. Modeling this behavior enables the Dumbo Octopus to quickly explore various locations, increasing the likelihood of finding an optimal solution. The mathematical model for this behavior is as follows:

where is a random number between 0 and 1, and represents the Dumbo Octopus candidate position vector for the next iteration.

When , the algorithm simulates the behavior of the Dumbo Octopus when exploring a familiar environment. Upon recognizing a familiar area, the Dumbo Octopus re-assesses prey abundance and the associated risks. In this context, all individuals in the DOA are treated as candidate solutions. To enhance foraging efficiency and quickly capture prey, the DOA moves to various positions in the search space, guided by the distance between two random position vectors. This enhances global exploration capabilities and aims to identify the current optimal solution. During each iteration, the algorithm evolves by facilitating position interaction and updates within the population through a dynamic field based on random distances. The neighborhood of each individual is automatically adjusted according to the position vectors of two random Dumbo Octopuses, effectively leveraging historical information from the iteration process. This ensures population diversity and allows the algorithm to thoroughly explore the problem space in the early stages. The mathematical model of this process is shown below:

where represents the current position vector of the Dumbo Octopus, and represents the position vectors of two individuals randomly selected from the entire population, is a random number between 0 and 1, and represents the candidate position vector of the Dumbo Octopus for the next iteration.

3.2.3. Capture Phase (Balance Exploration and Exploitation)

The DOA simulates these catching behaviors, switching methods based on prey distance, food intake complexity, and hunger level to balance exploration and exploitation stages, ensuring feeding efficiency and quality. In each iteration, the algorithm updates the position of the DOA using the distance information between the current individual’s position vector and a random individual’s position vector. This accelerates information flow between individuals, ensuring overall convergence speed and accuracy while mitigating algorithm stagnation. Additionally, the algorithm’s coverage in the search space is improved by constantly changing the neighborhood of each individual. To maintain population diversity and prevent premature convergence, a dynamic switching probability parameter is introduced, balancing global exploration and local exploitation in each iteration. The mathematical model of this process is shown below:

where represents the current position vector of the Dumbo Octopus, represents the position vector of an individual randomly selected from the entire population, is a random value between 0 and 1, and represents the candidate position vector of the Dumbo Octopus for the next iteration. is a dynamic switching probability factor, simulating the distance of prey, the complexity of food intake, and the degree of hunger to switch the capturing mode. The formula for is shown as follows:

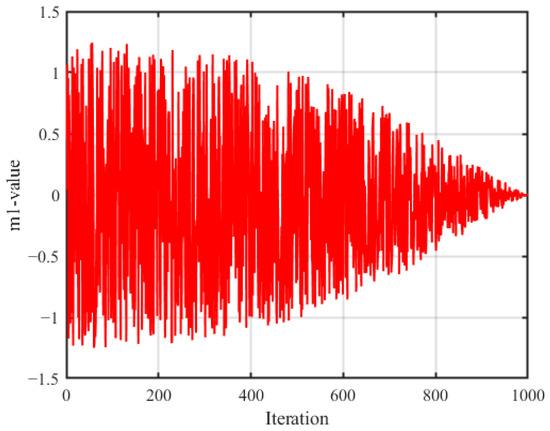

where represents the current number of iterations, represents the maximum number of iterations, , , and are random numbers between 0 and 1, and represents a sign function used to explore a wide search space. is a fixed value, and is used to simulate the maximum degree to which the Dumbo Octopus judges the distance of prey, the difficulty of food intake, and the hunger condition. is a parameter related to the number of iterations.

Figure 2 illustrates how the value of changes with the number of iterations. Clearly, can fluctuate over a large range, allowing the Dumbo Octopus to explore as much space as possible, and within a small range, enabling localized exploration. This property allows for flexible switching between catching modes, balancing global exploration and local exploitation effectively.

Figure 2.

Variations in the value of m1.

3.2.4. Seduction, Scare, and Escape Phase (Exploitation)

The Dumbo Octopus attracts prey through its luminous luminaries and chooses the most favorable prey to catch. This seduction behavior of the Dumbo Octopus is governed by the principle of optimality. In the Q-learning strategy [48,49], the reward table is a matrix used to punish and reward the agent according to the combination of the agent’s actions and states. The Q-table can be assumed to be the agent’s experience [50]. The agent tries to choose the best action by updating its state, which considers the corresponding Q-value, the value in the Q-table, and all possible actions it can take. Each agent gains experience by exploring the environment in a particular iteration (number of iterations) and updating the corresponding Q-table according to Bellman’s equation:

where is the learning rate (), which determines how much new information overrides the old information. is the discount factor (), which determines the importance of future rewards. is the current state. is the action taken. is the next state after acting . represents the possible actions in the next state, . is the immediate reward calculated by and . The main idea of the Q-learning strategy is to build a Q-table according to the different states of and different actions of to store values, and then select the actions that can obtain the greatest benefits according to the values. The search steps of the Q-learning algorithm are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

The pseudocode of Q-learning algorithm.

The algorithm simulates this behavior of the Dumbo Octopus when . In this stage, individuals in the population act as agents, the state represents the current actions of everyone, and the action represents the change of everyone from one state to another. Q-learning controls the actions of everyone at this stage, adaptively switching from one state to another according to the Q-table. In the reward table, a reward (+1) is given to an individual who performs well, while a negative reward (−1) is given to an individual who performs poorly. When , the prey is captured. Otherwise, the Dumbo Octopus position vector remains unchanged. The mathematical model of this process is as follows:

where represents the current number of iterations, represents the maximum number of iterations, represents the position vector of the current optimal prey, is a random value between 0 and 1, represents the current position vector of the Dumbo Octopus, is used to simulate the migratory path of the prey attracted, and represents a random variable of the Student-t distribution with six degrees of freedom. It is used to simulate the behavior of the Dumbo Octopus, as it quickly catches and grabs its prey. In this process, this paper initializes the Q-table as a zero matrix, and the reward table is shown as follows:

At the same time, the best operation to perform for the current iteration is obtained based on the values contained in the Q-table of the current state. We perform the selected actions and calculate the new fitness, calculating instant rewards as required. Finally, the Q-table is updated according to the formula. The instant rewards are as follows:

When , the algorithm simulates the scare and flight behaviors of the Dumbo Octopus. Predators such as tuna and sharks can influence its optimal foraging behavior. When a predator appears, the Dumbo Octopus abandons its prey and quickly shifts to an escape strategy. The algorithm uses the distance between the improved differential mutation strategy and random individuals as the neighborhood for the current optimal solution. This allows the Dumbo Octopus to perform targeted location updates during each iteration, generating multiple aggregation areas and enhancing the local exploitation capability of the DOA algorithm. This approach facilitates effective communication between individuals in different spaces, maintains population diversity, and reduces the likelihood of premature convergence. Additionally, by using the position vectors of individuals with the top four fitness values, an improved mutation strategy is constructed to simulate the Dumbo Octopus’s escape actions. This strategy combines local and global information, rather than relying on a single mutation approach, to enhance local search and optimization abilities. This method helps avoid issues such as premature convergence and search stagnation, while improving the convergence speed and accuracy of the algorithm. The mathematical model of this process is as follows:

where

where is used to simulate the migration path of natural enemies such as tuna and shark, is a random value between 0 and 1, represents the position vector of the current optimal natural enemy, , , and represent the position vectors of the individuals whose fitness values rank second, third, and fourth, respectively, and represents the position vector of the individuals randomly selected from the whole population. is an improved differential mutation strategy that is used to simulate the flee behavior of the Dumbo when it finds the enemy behind, violently contracts the interbrachial membrane to obtain the burst speed, and escapes.

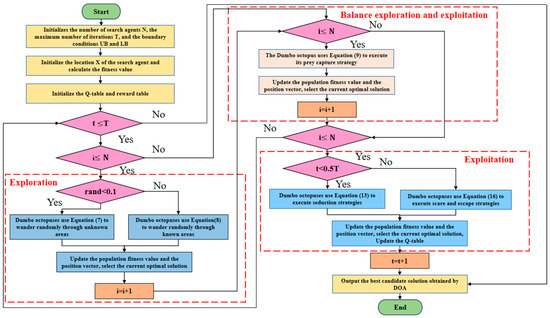

3.3. Pseudocode and Flowchart

This subsection presents the pseudocode and flowchart to demonstrate the DOA optimization process. The optimization begins by generating a randomly predefined set of candidate solutions, known as the population. Through a series of search strategies, including risk judgment, capture, seduction, scare, and escape, the DOA explores reasonable locations near the optimal solution. The position of each solution is updated based on the best solution obtained throughout the optimization process. The DOA search process terminates when the termination criteria are met. The pseudocode of the proposed algorithm is shown in Table 2, and its flowchart is illustrated in Figure 3.

Table 2.

The pseudocode of the DOA.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the proposed DOA algorithm.

4. Experiments and Discussion

To verify the ability of the proposed DOA to solve the global optimization problem, the DOA performance is tested and discussed in this section.

4.1. Benchmark Functions and Comparative Optimization Algorithms

The evaluation of the DOA’s optimization performance utilized three sets of renowned benchmark functions [50,51], encompassing the 23 classic benchmark functions, as well as the test suits of the CEC2017 and CEC2019 benchmark functions. Various well-established performance indicators, such as best-so-far (BEST), worst-so-far (WORST), average (AVG), and standard deviation (STD) of the optimal solution, were employed to quantitatively assess the quality of the solutions obtained. Each algorithm was independently executed 30 times for each test function, with a maximum of 500 iterations per run. A comparative analysis was conducted against 11 competing metaheuristic optimization algorithms, including established methods like PSO, GWO, WOA, SCA, AO, HHO, and ALO as well as recent approaches like SMA, TSA, SCSO, and BWO. This comparison aimed to validate the superiority and statistically significant differences of the proposed DOA.

4.2. Experimental Settings

All experiments in this study were conducted on a computer equipped with MATLAB 2022a, featuring a 12th Gen Intel(R) Core (TM) i5-12600KF processor clocked at 3.70 GHz with 16 GB of memory. The control parameters for the competing algorithms (ALO, AO, BWO, GWO, HHO, PSO, SCA, SCSO, SMA, TSA, and WOA) were set as identical to their original implementations. However, the parameters for the proposed DOA are detailed in Section 4.3. Specific parameters for each algorithm are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Parameter settings of optimization algorithms.

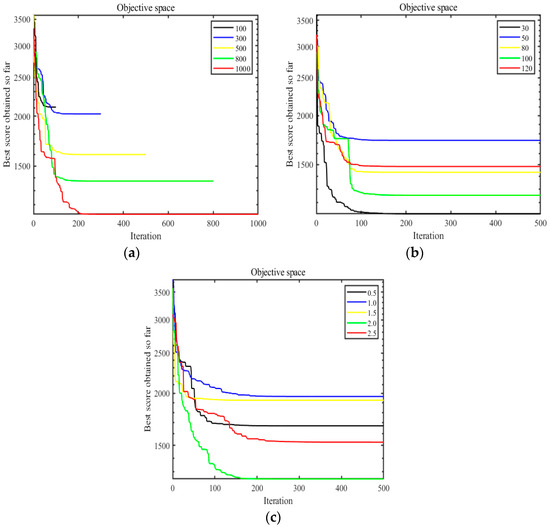

4.3. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

The parameter sensitivity analysis investigates how variations in control parameters affect the performance of an optimization algorithm. The control parameters in the algorithm can be categorized into dynamic parameters, which automatically update during optimization, and fixed parameters, whose values remain constant throughout iterations. Dynamic parameters, such as the dynamic switching probability factor, do not require a sensitivity analysis due to their automatic adjustment nature. In contrast, fixed parameters like maximum number of iterations, population size, and fixed value are subjected to a sensitivity analysis to understand their impact on algorithm performance.

To assess the sensitivity of key parameters, this study conducts sensitivity analyses on the maximum number of iterations, population size, and fixed value across a set of benchmark functions (F5, F15, F23 from a set of 23 benchmark functions; F1, F10, F30 from CEC2017; and F5, F10 from CEC2019). Each setting was performed once independently to capture key sensitivity trends. For brevity, the discussion uses F10 from CEC2017 as a representative example, analyzing its convergence under different settings of maximum iterations, population sizes, and fixed values.

- Maximum number of iterations: The sensitivity analysis varies the maximum iterations between 100, 300, 500, 800, and 1000, while keeping the population size at 30 and fixed value is set to 2.

- Population size: This analysis examines population sizes of 30, 50, 80, 100, and 120, with a fixed maximum iteration of 500 and fixed value is set to 2, aiming to determine the optimal population size for enhancing algorithm accuracy.

- Fixed value : This parameter influences the balance between global exploration and local exploitation in the algorithm. The sensitivity analysis tests fixed values of 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, and 2.5, with a population size of 30 and maximum iterations set to 500, aiming to identify the optimal fixed value that facilitates effective algorithm convergence.

The optimal solutions obtained for different settings of maximum iterations, population sizes, and fixed values are summarized in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5, respectively. Convergence curves depicting algorithm performance under these varied conditions are presented in Figure 4. From Table 5 and Figure 4a, it is evident that increasing the maximum number of iterations enhances convergence towards the optimal solution. Table 5 and Figure 4b indicate that a population size of 30 yields significantly better results compared to other settings. Moreover, Table 6 and Figure 4c demonstrate that a fixed value of 2 generally produces results closer to the optimal solution across various benchmark functions.

Table 4.

The optimal solution of DOA under different maximum iterations.

Table 5.

The optimal solution of DOA under different population numbers.

Figure 4.

Sensitivity analysis of key parameters: (a) maximum number of iterations; (b) size of population; (c) fixed value a1.

Table 6.

The optimal solution of DOA with different fixed values a1.

In conclusion, the sensitivity analysis on these key parameters provides insights into their effects on algorithm performance, aiding in the optimization and fine-tuning of the proposed algorithm for better practical application.

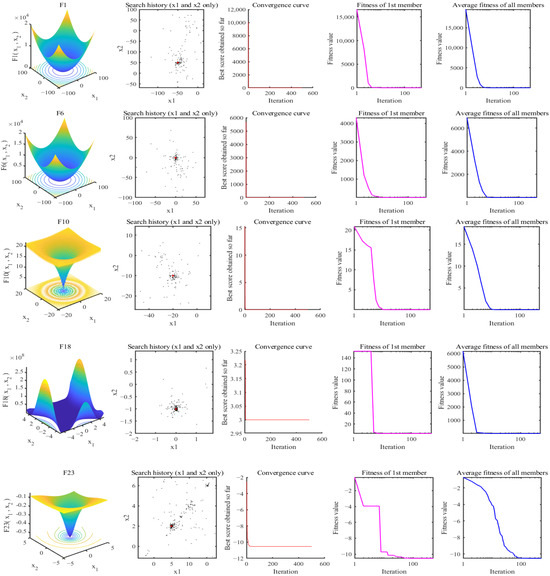

4.4. Qualitative Analysis for Convergence

Convergence in an algorithm denotes its ability to achieve the global optimal solution within a specified iteration limit. In this study, the convergence of the proposed DOA is evaluated using eight randomly selected benchmark functions (F1, F6, F10, F18 and F23). Figure 5 presents the search history of the proposed DOA, featuring 3D representations of the benchmark functions in the first column, the population’s search history in the second column, and convergence curves in the third, fourth, and fifth columns illustrating the DOA’s performance in terms of overall convergence, fitness values of the first objective function, and average fitness values of the population, respectively. From the analysis of Figure 5 across all selected benchmark functions, several observations can be made:

Figure 5.

Search history of the proposed DOA.

- (1)

- Sample points are uniformly distributed across the search space and tend to cluster around the optimal values.

- (2)

- The algorithm exhibits rapid convergence in the early stages of iteration, transitioning to a slower convergence rate in the middle and late stages.

- (3)

- Both the fitness values of the first objective function and the average fitness curve of the population decrease swiftly in the early stages and stabilize as the iteration progresses.

These findings collectively demonstrate that the proposed DOA effectively balances global exploration and local exploitation. It shows a capability to approach optimal solutions with a satisfactory convergence speed, highlighting its potential efficacy for solving optimization problems across diverse benchmark functions.

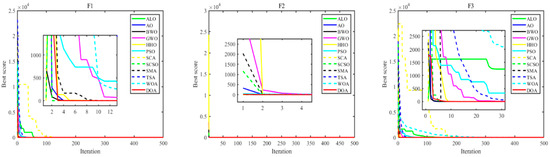

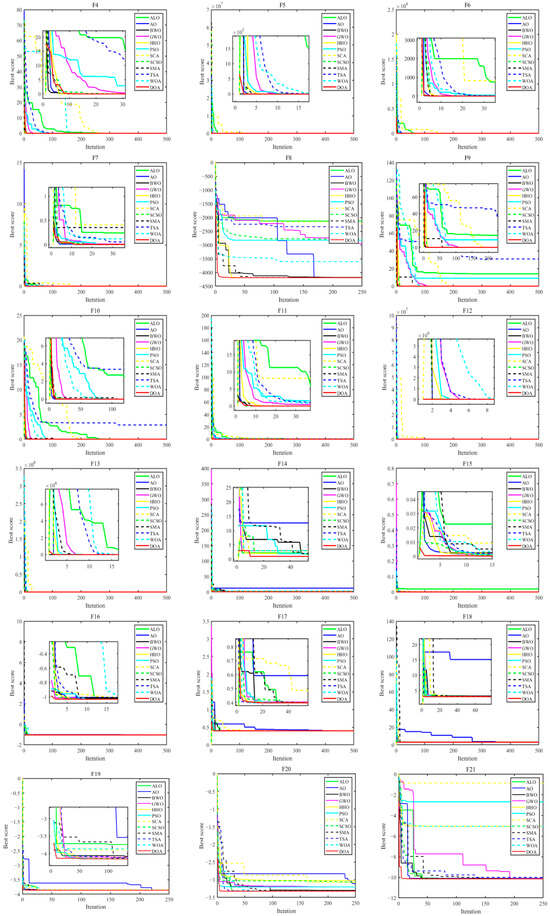

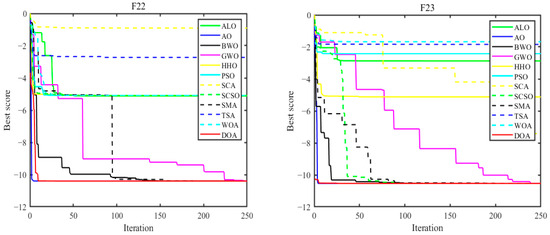

Furthermore, the convergence characteristics of the proposed DOA are contrasted with those of 11 other competing algorithms across 23 classical benchmark functions. The DOA exhibits distinct convergence behaviors: it initially converges rapidly within the designated search space during the iterative process. Importantly, the algorithm demonstrates resilience against being trapped in local optima, showcasing an ability to explore around current optimal values and ultimately converge towards the global optimum.

Figure 6 presents the convergence curves of the proposed DOA alongside those of the 11 competing algorithms across the benchmark functions. A comparative analysis reveals the following:

Figure 6.

Convergence curves of different algorithms.

- The DOA achieves convergence to the optimal solution relatively quickly.

- It effectively captures high-precision solutions within a reduced number of iterations compared to the other algorithms.

These results underscore the efficacy of the proposed DOA in swiftly achieving convergence and securing accurate solutions across a diverse set of benchmark functions, highlighting its competitive performance among contemporary optimization algorithms.

4.5. Results Comparison Using Benchmark Test Functions

4.5.1. Comparison of Results of Classic Benchmark Functions

A total of 23 classical benchmark functions were employed to evaluate the performance of the proposed DOA, along with 11 comparative algorithms (ALO, AO, BWO, GWO, HHO, PSO, SCA, SCSO, SMA, TSA, and WOA). Each algorithm was independently run with a maximum of 500 iterations, and performance metrics, such as Best-so-Far (BEST), Worst-so-Far (WORST), Average (AVG), and Standard Deviation (STD), of the optimal solutions from 30 independent runs were computed.

These metrics serve specific purposes:

- BEST represents the smallest objective function value obtained, indicating convergence accuracy.

- WORST corresponds to the largest objective function value obtained; a smaller WORST value signifies better convergence.

- AVG reflects the average value of the optimal solutions, indicating concentration tendencies.

- STD measures the variability or repeatability of the algorithm’s performance across multiple runs.

The 23 benchmark functions are categorized into the following:

- Unimodal functions (F1–F7), which have a single global optimal value, used to evaluate exploitation ability.

- High-dimensional multimodal functions (F8–F13), featuring numerous local optima, used to assess global exploration ability.

- Fixed-dimensional multimodal functions (F14–F23), which test the algorithm’s ability to escape local optima.

- Table 7 presents the results of BEST, WORST, AVG, and STD metrics for the DOA and the 11 competing algorithms across all benchmark functions. The analysis of Table 7 reveals the following:

Table 7. Comparison of results of 23 classical benchmark functions.

Table 7. Comparison of results of 23 classical benchmark functions. - For benchmark functions F1, F2, F3, F4, F5, and F7, the DOA achieves significantly better BEST, WORST, AVG, and STD metrics compared to the other algorithms.

- Despite performing less favorably on benchmark function F6 compared to PSO, the DOA’s metrics still fall within an acceptable range and are competitive.

- Across high-dimensional multimodal (F8–F13) and fixed-dimensional multimodal (F14–F23) benchmark functions, the DOA consistently produces results closer to the optimal values, often outperforming the other algorithms.

In summary, the DOA demonstrates superior optimization performance and strong competitiveness relative to the 11 competing algorithms. It effectively balances global exploration and local exploitation, making it a robust choice for solving a variety of optimization problems represented by diverse benchmark functions.

4.5.2. Comparison of the Results of the CEC2019 Benchmark Functions

In this subsection, the performance of the proposed DOA is further evaluated using the CEC2019 test suite, which provides a rigorous assessment across a diverse set of benchmark functions. This suite is designed to comprehensively test optimization algorithms with various complexities and challenges.

CEC2019 benchmark functions were employed to evaluate the performance of the proposed DOA with 11 comparative algorithms. Each algorithm was independently run with a maximum of 500 iterations, and performance metrics such as BEST, WORST, AVG, and STD of the optimal solutions from 30 independent runs were computed.

These metrics serve specific purposes:

- Table 8 presents comparative results of BEST, WORST, AVG, and STD metrics obtained by the DOA and 11 competing algorithms (ALO, AO, BWO, GWO, HHO, PSO, SCA, SCSO, SMA, TSA, and WOA) on the CEC2019 benchmark functions. Key findings include the following:

Table 8. Comparison of results of CEC2019 benchmark functions.

Table 8. Comparison of results of CEC2019 benchmark functions. - For benchmark function F6, the STD metric obtained by TSA is smaller than that of the DOA, but TSA’s BEST, WORST, and AVG metrics are less optimal compared to the DOA.

- Across the remaining benchmark functions, the DOA consistently achieves superior BEST, WORST, AVG, and STD metrics compared to the 11 competing algorithms.

In summary, the DOA demonstrates excellent comprehensive performance when compared to competitive algorithms on the CEC2019 test suite. It showcases robust global exploration and local exploitation capabilities, effectively navigating complex optimization landscapes and achieving competitive results across a variety of benchmark functions. These results underscore the DOA’s efficacy and suitability for solving challenging optimization problems in practical applications.

4.6. Friedman and Nemenyi Tests

This subsection uses the Friedman test to evaluate the statistical significance between different algorithms, with the aim of highlighting the differences between them. The Friedman test is a non-parametric method used to assess whether there is a significant difference between multiple population distributions based on rank. This study compares DOA with 11 competing algorithms for the Friedman statistic on 23 classical benchmark functions and the CEC2019 benchmark functions test set. In determining statistical significance, a standard p-value, i.e., 0.05, was used in this paper. When the p-value is less than 0.05, there is a significant difference between the DOA and 11 competing algorithms. In addition, the Nemenyi test is used in this subsection to check which algorithms differ significantly from the proposed DOA. The Nemenyi test is a nonparametric test used to compare multiple independent samples, and it is one of the follow-up tests to the Friedman test. The key to the Nemenyi test is to calculate the critical distance (CD), which is modeled as follows.

where is the critical value corresponding to the significance level in the Nemenyi test, is the number of algorithms, and is the number of data sets. In this study, and . When the average rank difference (ARD) between the DOA and competing algorithms is greater than the CD, it indicates that the performance of the algorithms is significantly different.

Table 9 and Table 10 show the results of significance tests of 12 algorithms in 23 benchmark functions and the CEC2019 test set. As shown in Table 9, the proposed DOA obtained the smallest Friedman statistic among the 23 benchmark functions and CEC2019 test set, and the calculated p-value was less than 0.05. In the Nemenyi test, the ARD obtained by the DOA among the 23 benchmark functions and ALO, AO, WOA, GWO, HHO, SCA, BWO, and TSA is greater than the calculated CD. The ARD obtained between the CEC2019 test set and WOA, HHO, SCA, BWO, and TSA is greater than the calculated CD. Therefore, the proposed DOA is significantly different from the 11 competing algorithms and is clearly competitive in optimizing different benchmark functions.

Table 9.

Results of significance tests of iterative version on classical benchmark functions.

Table 10.

Results of significance tests of iterative version on classical CEC2019 benchmark function.

4.7. Scalability Test

To test the DOA’s ability to solve large-scale problems, this subsection analyzes the scalability of the DOA. The parameters of the algorithm used are set the same as in Section 4.2. The dimensions of the decision variables are set to 500, 800, and 1000 respectively, each algorithm is run independently 30 times, the maximum number of iterations is 500, and the population size is 30. In order to ensure the length and space of the article, F1, F2, F3, F4, F5, F6, and F7 of the 23 classical benchmark functions are excerpted as the objective functions. Table 11, Table 12 and Table 13 show the results obtained by 11 competing algorithms and the proposed DOA in seven benchmark functions, respectively.

Table 11.

Scalability test of 12 algorithms in 23 standard reference functions (F1–F7) at dim = 500.

Table 12.

Scalability test of 12 algorithms in 23 standard reference functions (F1–F7) at dim = 800.

Table 13.

Scalability test of 12 algorithms in 23 standard reference functions (F1–F7) at dim = 1000.

As can be seen from the tables, in the classical benchmark functions F1, F2, F3, F4, F5, and F7, when the decision variable changes from 500 to 800, the values of BEST, WORST, AVG, and STD obtained by the DOA are all smaller than those obtained by the 11 competing algorithms. However, in the classical benchmark function F6, the values of BEST, WORST, AVG, and STD obtained by the DOA are second only to those obtained by the BWO algorithm. The ALO algorithm and SCA algorithm obtain poor results in the seven benchmark functions. To sum up, in most functions, the DOA can be infinitely close to the optimal solution when the dimension of the decision variable is increased. Therefore, the DOA can maintain good accuracy and robustness in most cases when encountering large-scale problems and can solve large-scale problems.

4.8. Runtime Analysis

In this subsection, we analyze the running time of DOA and 11 competing algorithms. Due to space limitations, only some standard benchmark functions are selected for testing. This subsection calculates the total run time independently for each benchmark function, with a maximum iteration of 500 and a population size of 30, in order to compare the run times of the various algorithms. Table 14 shows the results of a comparison of the DOA’s optimal values and runtime with other algorithms.

Table 14.

Run-time comparison.

According to the results in the table, for the benchmark functions F1, F2, F4, F5, F6, F8, F9, F10, and F11, the running time of the DOA always ranks among the top three, and the optimal solution obtained by the DOA is significantly better than those of other algorithms. For the benchmark function F6, the DOA has the best running time of all algorithms, and its optimal solution is second only to PSO. On the benchmark function F12, the DOA’s runtime is second only to WOA, GWO, SCA, and TSA, but its optimal solution is better than those of all four algorithms.

Although the DOA runs longer on the benchmark functions F3 and F13, it is still within the acceptable range. This is because the DOA uses the intelligent exploitation switching strategy of the Q-learning mechanism, and although it increases a certain amount of computing overhead, its convergence accuracy is significantly improved. Overall, while the DOA runs longer on some benchmark functions than some optimization algorithms, its performance on these benchmarks is significantly superior.

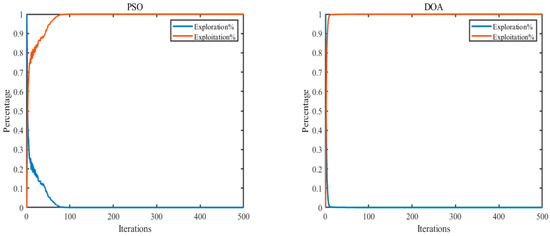

4.9. Exploration-Exploitation Ratio Analysis

In order to explore the reasons why the DOA performs worse than the PSO in benchmark function F6 in Section 4.5, this subsection discusses the exploration-exploitation ratio analysis of the PSO and DOA. However, the current ability of metaheuristic algorithms to balance exploration and exploitation is a relative concept that is challenging to quantify and specify. Different intelligent swarm optimization algorithms employ various strategies to achieve individual global and local exploration during the iterative process. When the algorithm diverges, the dimensional differences between individuals increase, leading to their dispersion throughout the search space. Conversely, when individual differences are small, individuals tend to cluster in a particular region, exhibiting the potential to converge toward the optimal solution. When the global exploration capability is too strong, the algorithm may escape from the optimal value. When the local exploitation is too strong, the algorithm may become stuck in a local optimum. A qualitative analysis of the convergence and quantitative analysis for benchmark functions may not provide a comprehensive understanding of the balance between the global and local exploration of the algorithms. Recently, a method called dimension diversity measurement has used the median instead of the mean to effectively reflect the population’s center. Its mathematical model is as follows:

where is the median value of the variable of the individual, represents the average value of all individuals, and denotes the average value of the diversity of each dimension. Thus, the percentage of exploration and exploitation of the population in each iteration can be expressed as

Figure 7 shows the exploration-exploitation ratio analysis of the PSO and DOA in the iterative process, providing intuitive evidence for studying the balance between exploration and exploitation of the PSO and DOA. The experimental parameters were set to 30 populations and 500 iterations, and the algorithm was run independently once. For the benchmark function F6, the exploration-exploitation ratios of the DOA and PSO are 0.00%:100.00%. Figure 7 shows that in the first 10 iterations, the DOA has strong exploration and weak exploitation. After iteration 10, the DOA rapidly reduced its exploration and then entered a distinctly exploitation phase. However, PSO can maintain a strong balance between exploration and exploitation in the early stage of iteration and has a strong exploitation ability in the late stage of iteration. This explains why the result obtained by PSO in the benchmark function F6 is better than that obtained by the proposed DOA.

Figure 7.

Exploration and exploitation of algorithms on F6.

5. FOPID Parameter Tuning of AVR System Based on Heuristic Algorithm

To verify the stability and reliability of the proposed DOA-FOPID controller, the proposed DOA-FOPID controller is tested under different conditions in this section, which mainly includes two types of analysis (step and robustness) of the controller. The fractional-order proportional-integral-derivative (FOPID) controller is an extension of the integer order PID controller [52]. At present, the proposed DOA is mainly used in offline environment to optimize the parameters of FOPID controller. The algorithm does not involve real-time adaptive adjustment in the process of execution, but determines the optimal controller parameter configuration in advance by offline optimization. This offline optimization method provides efficient initial parameter setting and is ideal for scenarios where the actual operation changes little or predictably. In this way, the DOA can ensure that the controller has been adjusted to an optimal state before actual deployment, which can quickly achieve stability and maintain efficient performance while the system is running. To meet the requirements of a practical engineering problem, five parameters of the optimal FOPID controller need to be found, namely, the proportional gain (), integral gain (), differential gain (), integral order () and differential order ().

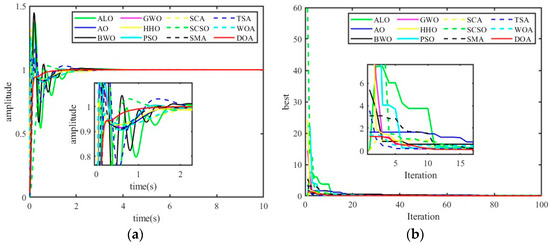

5.1. Step Response Analysis

In order to evaluate DOA algorithm’s solution to the problem of fractional PID parameter tuning in AVR system, this subsection runs DOA algorithm and 11 comparison algorithms independently for one time, and sets the maximum number of iterations and population number to 500 and 30, respectively. The rise time (), setting time (), overshoot (), steady-state error () and ITAE obtained by 12 algorithms in this problem are compared. Table 15 shows the optimization results of fractional-order PID parameter tuning. Figure 8a shows the step response diagram of fractional-order controller. Figure 8b shows the iterative curve diagram of FOPID parameter tuning by 12 algorithms. As can be seen from the table, , , and ITAE obtained by the DOA when optimizing FOPID controller parameters are smaller than those obtained by competitive algorithms. The FOPID controller with the DOA tuning can improve the dynamic response speed of AVR systems, reduce the overshoot and enhance the stability of AVR systems.

Table 15.

Optimization results of FOPID parameter tuning.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the results of tuning FOPID parameters by 12 algorithms: (a) step response; (b) iterative curve.

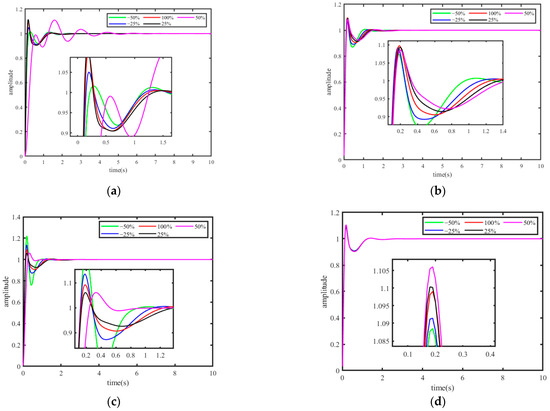

5.2. Robustness Analysis

In real industrial applications, the operating environment of an AVR system can experience various changes, such as fluctuations in load or the aging of equipment, which can cause controller performance to gradually degrade over time. In order to effectively deal with the performance degradation problem that may occur in the long-term operation of the system, the DOA can be used regularly for offline re-optimization. Through this periodic off-line optimization strategy, controller parameters can be updated and adjusted in time as the system ages or load conditions change, thus maintaining the long-term stability and reliability of the system.

In order to ensure that the parameters identified by the DOA can maintain the stability and robustness of the controller under different working conditions, this subsection provides a robust analysis of the time constants of the amplifier (), exciter (), generator (), and sensor () described in Section 2.2. The method used is to check the performance change of the DOA-based controller by changing the values of , , , and in the range of −50% to 50%, selecting rise time, settling time, and overshoot as the evaluation indicators. Figure 9 shows the results of robustness analysis under different parameter variations. Table 16 shows the robustness analysis results of the control system. It can be seen from Table 16 that with the changes of parameters of the AVG system, the proposed controller can also produce satisfactory results.

Figure 9.

The robustness analysis results under different parameter variations: (a) robustness analysis of ; (b) robustness analysis of ; (c) robustness analysis of ; (d) robustness analysis of .

Table 16.

The robustness analysis results of the control system.

6. Conclusions

The study introduces the “Dumbo Octopus Algorithm” (DOA), a novel metaheuristic inspired by the behavior of the Dumbo Octopus. Extensive testing compared the DOA with 11 common metaheuristic algorithms including 23 benchmark functions and CEC2019 suites. The key findings highlight several significant results: first, in quantitative and qualitative convergence analyses across benchmark functions, the DOA consistently outperformed competing algorithms in accuracy, speed of convergence, and robustness. Second, statistical tests confirmed significant differences between the DOA and other heuristic algorithms. Lastly, the successful FOPID parameter tuning of AVR using DOA further validated its performance.

In summary, the DOA algorithm exhibits clear superiority over existing methods, laying the groundwork for future research applications. Although the DOA has demonstrated excellent performance in the parameter optimization of FOPID controller in AVR systems, its performance is largely affected by its parameter configuration, and its application in other optimization problems has not been fully verified, which suggests that future research needs to further explore the effectiveness and applicability of the DOA in diverse application scenarios. At the same time, the comparison range of the algorithm is extended, and its performance in practical engineering problems is evaluated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L., G.W. and L.Z.; Methodology, Y.L. and G.W.; Validation, Y.L., S.S.A. and L.Z.; Formal analysis, G.W., S.S.A. and L.Z.; Investigation, L.N. and S.S.A.; Resources, L.N.; Data curation, G.W.; Writing—original draft, Y.L., L.N., G.W. and S.S.A.; Writing—review & editing, G.W., S.S.A. and L.Z.; Supervision, G.W.; Funding acquisition, L.N. and G.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the Doctoral Research Fund of Southwest University of Science and Technology under Grant No. 22zx7140 and the Key Technologies R&D Program of Sichuan Province, China under Grant No. 23ZDYF0471.

Data Availability Statement

The manuscript has associated data and code in the repository that can be publicly accessed through the following link: https://github.com/1Yuanyuan-Li/Dumbo-octopus-algorithm (accessed on 10 August 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article. No human participation occurs in this implementation process. No violation of human or animal rights is involved.

References

- Ćalasan, M.; Micev, M.; Radulović, M.; Zobaa, A.F.; Hasanien, H.M.; Abdel Aleem, S.H.E. Optimal PID Controllers for AVR System Considering Excitation Voltage Limitations Using Hybrid Equilibrium Optimizer. Machines 2021, 9, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogruer, T.; Can, M.S. Design and robustness analysis of fuzzy PID controller for automatic voltage regulator system using genetic algorithm. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2022, 44, 1862–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, S.; Izci, D.; Abu Zitar, R.; Laith, A. Development of Lévy flight-based reptile search algorithm with local search ability for power systems engineering design problems. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 20263–20283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micev, M.; Ćalasan, M.; Oliva, D. Fractional Order PID Controller Design for an AVR System Using Chaotic Yellow Saddle Goatfish Algorithm. Mathematics 2020, 8, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, N.D.; Sharma, G.; Gandhi, R.; Çelik, E. A Novel Salp Swarm Optimization Oriented 3-DOF-PIDA Controller Design for Automatic Voltage Regulator System. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 20181–20196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Lin, M.; Guo, J. Robust fractional order PID controller synthesis for the first order plus integral system. Meas. Control 2023, 56, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepljakov, A.; Alagoz, B.B.; Yeroglu, C.; Gonzalez, E.A.; Hosseinnia, S.H.; Petlenkov, E.; Ates, A.; Cech, M. Towards Industrialization of FOPID Controllers: A Survey on Milestones of Fractional-Order Control and Pathways for Future Developments. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 21016–21042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noman, A.M.; Almutairi, S.Z.; Aly, M.; Alqahtani, M.H.; Aljumah, A.S.; Mohamed, E.A. A Marine-Predator-Algorithm-Based Optimum FOPID Controller for Enhancing the Stability and Transient Response of Automatic Voltage Regulators. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muresan, C.I.; Birs, I.; Ionescu, C.; Dulf, E.H.; De Keyser, R. A review of recent developments in autotuning methods for fractional-order controllers. Fractal Fract. 2022, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegatheesh, A.; Thiyagarajan, V.; Selvan, N.B.M.; Devesh Raj, M. Voltage Regulation and Stability Enhancement in AVR System Based on SOA-FOPID Controller. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2024, 19, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salawudeen, A.T.; Nyabvo, P.J.; Nuhu, A.S.; Akut, E.K.; Cinfwat, K.Z.; Momoh, I.S.; Imam, M.L. Recent Metaheuristics Analysis of Path Planning Optimaztion Problems. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference in Mathematics, Computer Engineering and Computer Science (ICMCECS), Lagos, Nigeria, 18–21 March 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadimi-Shahraki, M.H. An Effective Hybridization of Quantum-based Avian Navigation and Bonobo Optimizers to Solve Numerical and Mechanical Engineering Problems. J. Bionic Eng. 2023, 20, 1361–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyyedabbasi, A.; Kiani, F. Sand Cat Swarm Optimization: A nature-inspired algorithm to solve global optimization problems. Eng. Comput. 2023, 39, 2627–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Awasthi, L.K.; Sangal, A.L.; Dhiman, G. Tunicate Swarm Algorithm: A new bioinspired based metaheuristic paradigm for global optimization. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2020, 90, 103541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.A.; Mirjalili, S.; Faris, H.; Aljarah, I.; Mafarja, M.; Chen, H.L. Harris hawks optimization: Algorithm and applications. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 97, 849–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Mirjalili, S.M.; Lewis, A. Grey Wolf Optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2014, 69, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.G.; Li, G.; Meng, Z. Beluga whale optimization: A novel nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 251, 109215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathollahi-Fard, A.M.; Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M.; Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, R. Red deer algorithm (RDA): A new nature-inspired meta-heuristic. Soft Comput. 2020, 24, 14637–14665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.R.; Hu, W.; Fan, Q.C.; Cui, Y.B.; Qi, C.K. A Q-learning based multi-strategy integrated artificial bee colony algorithm with application in unmanned vehicle path planning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 236, 121303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, H.T.; Shoaib, U.; Lali, M.I.; Alhaisoni, M.; Irfan, M.N.; Khan, M.A. Particle Swarm Optimization with Probability Sequence for Global Optimization. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 110535–110549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.Q.; Zhou, G.; Wang, L. A Cooperative Scatter Search with Reinforcement Learning Mechanism for the Distributed Permutation Flowshop Scheduling Problem with Sequence-Dependent Setup Times. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2023, 53, 4899–4911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S. The Ant Lion Optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2015, 83, 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualigah, L.; Yousri, D.; Elaziz, M.A.; Ewees, A.A.; Al-qaness, M.A.A.; Gandomi, A.H. Aquila Optimizer: A novel meta-heuristic optimization algorithm. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 157, 107250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhart, R.; Kennedy, J. A new optimizer using particle swarm theory. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Symposium on Micro Machine and Human Science, Nagoya, Japan, 4–6 October 1995; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1995; pp. 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S. SCA: A Sine Cosine Algorithm for solving optimization problems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2016, 96, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.M.; Chen, H.L.; Wang, M.J.; Heidari, A.A.; Mirjalili, S. Slime mould algorithm: A new method for stochastic optimization. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 111, 300–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Lewis, A. The Whale Optimization Algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2016, 95, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, V.E. General Fractional Calculus: Multi-Kernel Approach. Mathematics 2021, 9, 91501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guirao, J.L.G.; Mohammed, P.O.; Srivastava, H.M.; Baleanu, D.; Abualrub, M.S. Relationships between the discrete Riemann-Liouville and Liouville-Caputo fractional differences and their associated convexity results. AIMS Math. 2022, 7, 18127–18141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, L.; Dehghan, S.; Chen, Y.; Xue, D. A review and evaluation of numerical tools for fractional calculus and fractional order controls. Int. J. Control 2016, 90, 1165–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Vázquez, S.; Gómez-Aguilar, J.F.; Lavín-Delgado, J.E.; Escobar-Jiménez, R.F.; Olivares-Peregrino, V.H. Applications of Fractional Operators in Robotics: A Review. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2022, 104, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yang, Y.; Han, F.; Zhao, M.; Guo, L. Containment control of heterogeneous fractional-order multi-agent systems. J. Frankl. Inst. 2019, 365, 752–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelfattah, H.; Aseeri, A.O.; Abd Elaziz, M. Optimized FOPID controller for nuclear research reactor using enhanced planet optimization algorithm. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 97, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschos, I.; Parisses, C. A novel optimal PIλDND2N2 controller using coyote optimization algorithm for an AVR system. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2022, 26, 100991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Jiang, M.; Huang, Y. Formal Verification of Fractional-Order PID Control Systems Using Higher-Order Logic. Fractal Fract. 2022, 6, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oziablo, P.; Mozyrska, D.; Wyrwas, M. Fractional-variable-order digital controller design tuned with the chaotic yellow saddle goatfish algorithm for the AVR system. ISA Trans. 2022, 125, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sony, M.G.; Thomas, L.P.; Deepak, M.; Mathew, A.T. Frequency regulation on an interconnected power system with fractional PID controllers optimized using RAO algorithms. Electr. Power Compon. Syst. 2022, 50, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Chang, F. Fractional-order PID controller optimization via improved electromagnetism-like algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 2010, 37, 8871–8878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhookya, J.; Kumar, J.R. Sine-cosine-algorithm-based fractional order PID controller tuning for multivariable systems. Int. J. Bio-Inspired Comput. 2021, 17, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravari, M.A.; Yaghoobi, M. Optimum design of fractional order PID controller using chaotic firefly algorithms for a control CSTR system. Asian J. Control 2019, 21, 2245–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.; Molina, Y.; Silva, C.; Naupari, Z. Simultaneous tuning of the AVR and PSS parameters using particle swarm optimization with oscillating exponential decay. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 133, 107215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumari, M.Z.M.; Ahmad, M.A.; Rashid, M.I.M. A fractional order PID tuning tool for automatic voltage regulator using marine predators algorithm. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.A.; Alghamdi, A.S.; Jumani, T.A.; Alamgir, A.; Awan, A.B.; Khidrani, A. Salp Swarm Optimization Algorithm-Based Fractional Order PID Controller for Dynamic Response and Stability Enhancement of an Automatic Voltage Regulator System. Electronics 2019, 8, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhookya, J.; Jatoth, R.K. Optimal FOPID/PID controller parameters tuning for the AVR system based on sin-cosine-algorithm. Evol. Intell. 2019, 12, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirören, A.; Ekinci, S.; Hekimoglu, B.; Izci, D. Opposition-based artificial electric field algorithm and its application to FOPID controller design for unstable magnetic ball suspension system. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2021, 24, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türksoy, Ö.; Türksoy, A. A fast and robust sliding mode controller for automatic voltage regulators in electrical power systems. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2024, 53, 101697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, R.; Ahmad, M.A. Fast and optimal tuning of fractional order PID controller for AVR system based on memorizable-smoothed functional algorithm. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2022, 35, 101264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, C.J.C.H.; Dayan, P. Q-Learning. Mach. Learn. 1992, 8, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, U.K.; Das, P.K.; Kabat, M.R. Hybridization of meta-heuristic algorithm for load balancing in cloud computing environment. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34 Pt A, 2332–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandran, M.; Devanathan, S.; Muraleekrishnan, R.; Bhagawan, S.S. Optimizing properties of nanoclay–nitrile rubber (NBR) composites using Face Centred Central Composite Design. Mater. Des. 2012, 35, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahzadeh, B.; Gharehchopogh, F.S.; Barshandeh, S. Discrete farmland fertility optimization algorithm with metropolis acceptance criterion for travelling salesman problems. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2021, 36, 1270–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.C.; Tran, D.T.; Dinh, T.Q.; Ahn, K.K. Tracking Control for an Electro-Hydraulic Rotary Actuator Using Fractional Order Fuzzy PID Controller. Electronics 2020, 9, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).