Abstract

This paper studies a continuous-review stochastic replenishment model for a multi-component system with regular and emergency orders. The system consists of N parallel and independent components, each of which has a finite life span. In addition, there is a warehouse with a limited stock of new components. Each broken component is replaced by a new component from the stock. When no component is available, an emergency supply is ordered. The stock is managed according to an policy, which is a combination of an policy for the regular order and a policy for the emergency order. The regular order is delivered after an exponentially distributed lead time, whereas the emergency order is delivered immediately. We study three sub-policies for emergency orders, which differ from each other in size and in relation to the regular order. Applying the results from queueing theory and phase-type properties, we derive the optimal thresholds for each sub-policy and then compare the economic benefit of each one.

MSC:

60G51; 60J28; 93E20; 90B05

1. Introduction

Despite the high cost of immediate delivery, an emergency order is sometimes necessary to maintain a high service level and to avoid the high downtime costs of waiting for a regular order. There are many examples where an emergency order is manifested as a second source of replenishment. For example, in commercial aviation, delaying an airplane for two hours might cost the airline up to USD 150,000 [1]. Volvo Parts Corporation in Sweden, in addition to regular replenishment from a central retailer, issues an emergency order from local points in cases of stock-outs in its spare parts [2]. More examples come from the aircraft industry, the chemical industry, construction, and semiconductor manufacturing [3,4,5,6,7]. The above examples show that lack of inventory is a major concern, especially in systems with high down-time costs. Emergency orders have been proven to be an effective mechanism for improving the system performance. Because emergency orders are more costly than regular orders, the policy for requesting such orders is of crucial importance. Specifically, the questions facing the manager involve when to place the order, how much to order, and whether the order will be used as an addition to the regular order or as an alternative.

The purpose of this paper is to shed some light on the questions raised by investigating different emergency supply policies. We consider a continuous review system that has N components operating in parallel. The system functions as long as there are N operating components. Each operating component in the system has a finite life span independently of the others. When a component fails, it is immediately replaced by a new component (if available) from the company warehouse. The warehouse has a limited stock of new components that are held in cold standby and cannot fail. The stock is managed according to a base-stock inventory policy, so that when the number of components in stock drops to a specific level, a regular order is placed and the stock is replenished after some lead time. In order to ensure the sufficiency and reliability of the components in stock, complete maintenance is further provided by the supplier when the regular order arrives. However, if, during the lead time, the stock level drops to zero and an operating component fails, the system cannot continue functioning. Such a situation is unallowable, and the company’s protocol requires an immediate emergency supply of components. The need for an emergency supply is accompanied by important planning decisions. For example, the company needs to decide on the size of the emergency supply, and how the regular (pending) order and the maintenance activity associated with it will be affected by the emergency supply (if at all). This study aims to shed some light on these important decisions.

Identifying an optimal or near-optimal inventory control policy remains a complex problem for analysis and implementation [8,9]. Hence, research has focused on evaluating and optimizing simple heuristic inventory control policies. The and policies, as special types of the base-stock family, are frequently employed in practice and theory. Under the classical up-to-level policy, whenever the stock level drops to or below level s, an order is placed to bring the level up to S. The policy is often used in inventory control management. A real-world example of a supplier using the policy is a gas supplier and food suppliers refilling food-vending machines in public (e.g., in hospitals and academic institutions). In the context of multi-component systems, the policy is a common one, e.g., delivering to maintenance service engineers in isolated areas and nuclear power plants [10,11]. Under the fixed-order-quantity policy, when the stock level drops to or below r, a fixed amount of Q components is ordered. The policy has become more popular in practice in recent years due to advanced information systems [12,13]. Applications of reported in the literature include the aviation industry of Turkish Airlines Technic MRO [14], the auto industry [15], replenishment of fresh agricultural products sold in supermarkets [16], the bakery industry [17], and the shipping industry [18].

In this paper, we assume that the warehouse is managed according to an policy, which is a combination of the classical and policies (in this paper and ). Each time the stock drops to s, a regular order is placed and arrives after some random lead time; upon arrival, the stock is replenished to its full capacity level S. However, if during the lead time a component fails and no new components are available in the stock, an emergency order of a fixed size is placed in order to avoid a system shutdown. Thus, an policy is implemented for the regular order, as well as a policy for the emergency order. We study three emergency supply sub-policies for the emergency orders differ from each other in size and in relation to the regular order. We start with the sub-policy, i.e., both the emergency order and the regular order replenish the stock up to its maximum capacity. The second sub-policy assumes that ; i.e., the emergency order may be smaller than the regular order. Under both sub-policies, an emergency order cancels the regular order. The third sub-policy also considers a smaller emergency order however, there is no cancellation and the regular order arrives after the lead time, as expected.

In the real world, the need for an emergency supply stems from the randomness of both the component’s life span and the lead times. We study the case of an exponentially distributed lead time and a phase-type distributed life span of each component. An exponentially distributed lead time is well motivated in practice; e.g., for a company that receives orders from several independent suppliers, each order is served in an M/M/1 queue. The lead time includes the preparation of the order and the delivery time and can be interpreted as the sojourn time of the M/M/1 queue, which is exponentially distributed. Examples of a model whose life span has a phase-type distribution can be found in Neuts [19] and Neuts and Takahashi [20]. In reliability models, a phase-type distribution is often useful to represent an evolutionary process, such as the degradation of a component and hence is appropriate to represent the life span of a component. It should be noted that when general distributions are used for modeling the life span of components, the phase-type family includes all finite mixtures of convolutions of Erlang distributions and, therefore, can be implemented in a natural way. We further note that any nonnegative continuous distribution of the probability can be approximated through phase-type distributions [21,22].

To assess the performance of the system under the different emergency policies, we assume the following costs: a replacement cost for each failed component, regular and emergency order costs including a fixed cost for each order, a variable cost depending on the quantity purchased, and maintenance cost for both the warehouse and the system. Using matrix-geometric methods and queueing models with phase-type distributions, we construct closed-form expressions for the costs and derive the optimal thresholds and , which minimize the expected discounted total cost. Our model belongs to the interdisciplinary field of inventory management with an emergency supply and system reliability.

The main contribution of this paper is threefold.

- (1)

- Compared to most of the literature on multi-component systems that allow system shutdowns, with a focus on system reliability, we propose a more practical and integrated model of such systems. The scope of the model covers a wide range of real-world problems, such as the uncertainty of lead times, random life spans, and limited warehouse capacity. In addition, the scope of our cost structure covers a wide range of costs. In particular, we consider both economies and diseconomies of scale for the maintenance cost. While most existing models assume either a fixed, linear, or concave cost function for maintenance activities, real-world examples show that maintenance activities may exhibit a convex cost function with diseconomies of scale with increasing marginal costs (due to overstocking, overuse of resources, increasing operational complexity, and so on). In this paper, we compare several cost functions that differ in their concavity and study the impact of these various concave cost functions on the system’s performance and the optimal thresholds. Our results show that the total cost is convex as a function of the thresholds. We further show that in contrast to the threshold , the threshold is significantly affected by the concavity pattern of the warehouse cost function: a concave cost yields a higher implying that it is worthwhile for the company to issue fewer but larger orders.

- (2)

- In this day and age of increasing competition and rising service levels, system shutdowns are usually prohibited, and as a result, emergency supplies are essential. Using numerical analysis, we compare different emergency order policies in a variety of scenarios, focusing on the financial benefit of canceling the regular order while ordering an emergency supply. By way of these comparisons, we provide managerial insights and practical applications that can help practitioners make more informed decisions regarding the optimal emergency order policy. For example, we show that when the emergency order costs are high, canceling the regular order yields significant cost savings. We further show that it is to the benefit of companies to issue fewer, but larger, emergency orders so as to achieve the full benefit of the emergency order.

- (3)

- Most of the literature is based on analytic derivations under the long-run average criterion, without taking the timing of payments into consideration. By contrast, our model is analyzed under the discounted cost criterion. When a company is considering issuing an emergency order, timing is a crucial factor that captures the trade-off between fixed and variable costs. Here, we introduce a practical policy in which the fixed cost (per order) is paid when the order is placed (as in reality, this cost is nonrefundable, even in the event of a cancelation) and the variable cost (per component) is paid when the order arrives. This difference in the timing of the two payments is important due to the discount factor, which makes our model more adaptable to real-world considerations that companies are faced with. In this regard, it is not surprising that increasing the discount factor leads to the postponement of the order time.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents a comprehensive literature review on base-stock policies with emergency supply. The preliminaries and the tools of our analysis are introduced in Section 3. The model is described in more detail in Section 4. In Section 5, Section 6 and Section 7, we derive the cost functions for the three emergency order sub-policies. Numerical results, comparisons, and sensitivity analyses are also provided. Finally, Section 8 concludes and suggests some avenues for future research.

2. Literature Review

Our model belongs to the interdisciplinary field of base-stock inventory control management with emergency supply and system reliability. In what follows, we review the literature of these fields and underline our contributions.

In the delicate balance between the risk of stockout, operating components with random life spans, and orders with random lead times, companies endeavor to find the most efficient inventory policy. Base-stock inventory policies with emergency supply are designed to solve this problem in the most practical way [23]. The use of base-stock inventory policies with emergency supply dates back to Moinzadeh and Schmidt [24], who place the emergency orders depending on the arrival times of the regular orders in addition to the stock level. Dohi et al. [25] analyzed a model where the stock level is continuously reviewed after a fixed amount of time, , and the decision of whether to place an emergency order or a regular one depends on the stock level. Similarly, Giri and Dohi [26] derive the optimal ordering time that maximizes the cost-effectiveness criterion for a fixed-order quantity model. Song and Zipkin [27] extend Moinzadeh and Schmidt [24] by considering a system of multiple supply sources under stochastic demand and lead times. Allon and Mieghem [28] propose an inventory policy of ordering a fixed quantity from the regular supply source and a variable quantity from the emergency supply one. Howard et al. [2] introduce a modified policy, where the emergency supply policy is based on the time that it takes the regular order to reach some point. Barron and Hermel [29] study production–inventory models with two dual-sourcing policies under backordering and lost sales. Kouki et al. [30] derive the steady-state behavior of a dual-sourcing policy with perishable items. Among the studies that assume deterministic lead times, we cite Axsäter [31] and Huang et al. [32], who propose several heuristic decision rules for ordering emergency supplies.

Many relevant studies that assume stochastic lead times also assume a inventory policy. Among these studies are [33,34]. Boxma et al. [35] consider a policy with regular and emergency orders that are issued at different stock levels and delivered after exponentially distributed lead times. In between deliveries, the stock level decreases according to a state-dependent rate function · We refer to Poormoaied et al. [5] and Svoboda et al. [36] for extensive reviews of the literature on continuous- and periodic-review inventory models with an emergency supply.

We note that the inventory management of spare parts is closely related to our model [37,38]. In a series of papers, Wang et al. [39], Xie and Wang [40], and Wand et al. [41] present a joint strategy that combines periodical inspections and an policy for regular orders. For a similar system, Keizer et al. [42] formulate the problem as a Markov decision process minimizing the long-run average cost per time unit. Bacchetti et al. [43] develop a hierarchical multi-criteria classification method to enable differentiation between planning choices according to the parts’ specificities. Selçuk [6] models a multi-dimensional Markov chain for a single-item system and presents an adaptive base-stock inventory policy for the spare parts in which stock-out situations are handled by emergency shipments. Mo et al. [44] consider different response times under different user requirements. Teixeira et al. [45] present a multi-criterion classification methodology that combines maintenance and logistic perspectives. Johansson and Olsson [46] focus on a spare-parts inventory system with nonlinear backorder costs. Using approximation, Boucherie et al. [47] obtain the control levels for a spare-parts inventory model for repairable parts and emergency shipments. Wingerden et al. [48] show that emergency shipments can lead to cost savings of up to 30%. Using a dynamic early-warning model, He and Gao [49] incorporate two maintenance approaches: one for the regular order and one for the emergency order. Marchi [50], Çelik et al. [51], and Cardona and Rivera-Cadavids [52] discuss the coordination of replenishment policies with warehouse operation costs. Poormoaied et al. [5] consider a periodic-review problem of a retailer who uses a base-stock inventory policy for regular replenishment and a specific-time policy for emergency orders.

The above literature review shows that base-stock inventory policies with an emergency supply have been widely studied in the context of inventory management [53]. However, they have received far less attention in the context of system reliability [54,55]. Relatively few papers study different emergency ordering policies to prevent a system shutdown. Rahimi-Ghahroodi et al. [56] designed a cooperative contract between an emergency supplier and a service provider in asset management where the system is subject to random shutdowns. Mor et al. [57] presents a framework based on the obsolescence rate of the components. Basten and van-Houtum [58] considered multi-item inventory models with central and local warehouses with emergency shipments. Oshan and Caron [59] presented an optimization model for a system design under the risk of shutdown that includes the location and the capacity of the warehouse. Peng et al. [60] examined the effects of supply reliability, risk aversion, and wealth on the optimal order policy of retailers in the context of uncertain demand.

In theory as in practice, the need for an immediate emergency supply stems from the randomness of both the life span and the lead time. Exponentially distributed lead times are well supported by the literature. Song et al. [7] used an exponential server to capture the randomness of lead times. Chang [61] investigated the impact of exponentially distributed lead times on the performance measures of spare-parts stock. Boxma et al. [35] considered exponentially distributed lead times for both regular and emergency orders. More examples are found in [54,62,63]. This paper considers a phase-type distributed life span, which is an extension of the exponential distribution. Models with phase-type distribution in reliability analysis can be found in [22,64], among others. However, while most of these studies focus on evaluating the performance characteristics of the system, little effort has been invested into analyzing the interaction between system performance, inventory control, and the impact of different emergency supply policies. In this paper, we aim to shed light on this interaction.

To outline our position, the most relevant studies concerning inventory and reliability models under the base-stock policy are given in Table A1 in Appendix A. To conclude the literature review, we point out that none of the papers cited above have studied emergency supply policies for a multi-component system with random lead times and life spans in the context of system reliability. To the best of the author’s knowledge, this is the first paper to do so. Hence, the model developed below significantly contributes to the existing literature.

We next briefly summarize the main tools used in our analysis in order to make this paper self-contained. Following convention, vectors are marked in bold letters, and matrices in blackboard bold letters. We let be the indicator of an event be the unit column vector, and be the identity matrix. Dimensions of vectors and matrices are omitted if they can be easily understood from the context.

3. Preliminaries and Notation

- (a)

- Exponential distribution and related properties

Let X be a nonnegative generally distributed random variable (r.v.) with a Laplace–Stieltjes transform (LST) Let Y be an independent exponentially distributed r.v. at rate . It is easy to verify that

- (b)

- Phase-type distribution and Kronecker functions

Let be a continuous-parameter Markov chain with an infinitesimal generator The transition matrix rate is of order such that for and for That is, the time spent at each state , is an exponentially distributed r.v. at a rate and is the transition rate from state i to state . The n-column vector describes the absorption rate into state and is the initial probability vector of order on the set of transient states. A phase-type (PH) distributed r.v. with representation of order n is the distribution of the time until absorption into state 0 of the chain Its probability distribution function and density function are given, respectively, by

with mean and LST In our study, we will use the matrix multiplication whose -th element is

The symbols ⊗ and ⊕ denote the Kronecker product and the Kronecker sum of matrices, respectively (see [19,21] for a discussion on the properties of the Kronecker product and sum). Let be an n-square matrix; then, the matrices and are given by

Note that

Corollary 1.

Let of order n and of order m be two independent random variables. The r.v. has a PH distribution with representation of order , where

i.e., and (see Theorem 2.6.4 in [65]).

- (c)

- The phase-type (PH) renewal process and the variable

Consider a renewal process where the times between renewals are i.i.d. r.v.’s having distribution of order n. Such a process is called a PH renewal process ([19]). From the construction of the PH distribution, we may visualize a phase-type renewal process as follows. When the process enters the absorbing state 0, a renewal occurs and the process is instantaneously restarted with the initial probability vector . Let be the number of renewals in Obviously, is Markovian. For more details, see [19]. Next, we expand the PH renewal process and consider N independent and identically distributed PH renewal processes of order n; i.e., when enters state 0, a renewal occurs and is instantaneously restarted with initial probability vector .

In our context, we consider a system that contains N independent “places” for the N operating components. Each operating component has a distributed life span of order When an operating component fails, it is replaced by a new component from the warehouse, if available (a renewal). Thus, the number of components that fail at each “place” is a PH renewal process. Of special interest is the time until the i-th failure. Let and (both are matrices of order ), andassume that N operating components start with initial phase vector Neuts and Takahashi [20] showed that is a distributed r.v. of order The matrix and the vector are given by

The transition rate matrix is either the matrix representing the failure of a component and its replacement by a new one from the stock, or the matrix representing the transitions between the states of the operating components. (Note that .) Let and be the density function, probability distribution function, and LST function of respectively. We further denote by the LST matrix form of given by

(The last multiplication by the probability vector in (4) indicates the phase selection of the new component that replaces the broken one).

4. Mathematical Description of the Model

We assume a system with N independent components that operate in parallel. Each component has a random life span and is subject to failure. Denote by the life span of a component We assume that are i.i.d. r.v.’s following a phase-type distribution with representation of order When a component fails, it is no longer usable and is discarded. Thus, upon failure, the component is replaced by a new component from the stock, if available; the replacement takes a negligible amount of time, and the new component starts operating in the system, independently of other operating components, at a phase that is chosen according to the probability vector . The new components are stored in a warehouse and cannot fail while in storage (also known as cold standby status). We assume that the warehouse has a limited capacity of S components. The stock in the storage is managed according to a continuous review -type inventory policy, which is an extension of the classical base-stock inventory policy. Under the classical policy, whenever the stock of new components drops to level an order is placed to raise the stock level up to S. Here, we assume that the order is carried out after an exponential lead time Y at rate Upon arrival, the provider is used for additional services and a complete maintenance of both the system and the warehouse is performed. That is, the stock is replenished by up to S new components, and the N operating components are upgraded to as-good-as-new condition at a phase chosen according to the vector . From that point on, the system starts operating like new with N components.

To clarify, we summarize the main assumptions of the model.

- 1.

- The system consists of N i.i.d. components, each of which has a phase-type distribution life span.

- 2.

- New components are stored in a finite capacity warehouse in cold standby status.

- 3.

- The warehouse is managed according to an policy, that is, an policy for the regular order, and for the emergency order.

- 4.

- The regular order arrives after an exponentially distributed lead time while the emergency order arrives immediately.

- 5.

- Upon regular order arrival, the complete maintenance of the system and the warehouse is performed.

We note that the assumption of a phase-type distribution for the life span is quite general, since any nonnegative continuous distribution can be approximated through the phase distributions. Moreover, we are aware that an exponential lead time simplifies the analysis. However, when the lead time distribution is general, our results may still be used as an approximation. We further note that in some cases, an emergency order arrives after some lead time (albeit significantly shorter). In this case, the analysis becomes extremely challenging, and, thus, we leave it for future work.

Let be the number of new components in stock at time t with Let be an N-dimensional vector of the phases of the working components in the system at time Let be the two-dimensional process with a state space given by

When s components fail during the lead time, decreases to and the system operates with zero new components in stock. In that case, if one of the N operating components fails before the order arrives, the system cannot continue operating. Thus, to keep the system operating, an emergency supply is ordered and received in a negligible amount of time at a premium cost. In what follows, three emergency supply sub-policies are suggested.

- (a)

- The policy. The emergency supply consists of new components, of which S are stored in the warehouse, and one joins the components in the system. From that point on, the system continues operating. In this case, the regular order is no longer necessary and, therefore, is canceled (with a cancellation fee). When the emergency supply arrives, complete maintenance of the warehouse and the system is carried out, and the system is upgraded to as-good-as-new condition. Under this policy, the main duty of the provider is to deliver the emergency supply in a negligible amount. Once the provider arrives, they can also perform additional services, such as handling, upgrading, and maintaining the system and the warehouse.

- (b)

- The policy, . Here, we extend the above policy and consider a smaller emergency order. Specifically, when drops to level s, a regular order is placed. However, if during the lead time a component fails and no new components are available in the warehouse, an immediate and expensive emergency order of size () is placed, and the regular order is canceled. Whenever the stock drops to level s again, a new (regular) order is placed.

Note that under both policies, the complete maintenance of the warehouse and the system is performed when either the regular order or the emergency supply arrives.

- (c)

- The policy, Here, too, when drops to level a regular order is placed. However, if during the lead time a component fails and no new components are left, an immediate and expensive emergency order of size is placed. What distinguishes this policy from the second policy is that the emergency supply serves only as a temporary source in addition to the regular order. Therefore, the regular order is not canceled, and maintenance is performed only when the regular order arrives. Note that subsequent emergency orders may be placed during the lead time.

Let be the j-th time that the warehouse is replenished up to S new components and undergoes complete maintenance. Clearly, the two-dimensional process is a regenerative process that starts anew from level the times are the regenerative points of the process. We define the cycle length with . Note that the cycle length is composed of two subsequent periods: (i) the time until failures occur at that time, drops to s and an order is placed, and (ii) the remaining time until the warehouse is replenished and undergoes complete maintenance. It is easy to verify that the stochastic behavior of before level 0 is similar under all three emergency policies. It changes only after the emergency order is placed.

4.1. The Cost Structure

We assume the following costs.

- Replacement cost. Let be the cost of replacement of a broken component by a new component from the warehouse.

The costs of the regular order

The regular order includes three components: an order cost for each order issued (fixed cost), a cost of maintaining the warehouse (warehouse cost), and a component cost for each purchased component (variable cost). More precisely:

- Fixed order cost. Whenever the number of components in stock drops to level s, an order is placed at a cost of . As in practice, is paid at the time of ordering, and it is nonrefundable, even if the order is canceled.

- Warehouse cost. Let be the cost of maintaining the warehouse. Since the warehouse capacity is limited to S components, the cost is typically assumed to be proportional to S. There are several functions that are used to express the warehouse cost. Here, we consider two of them: a discrete piecewise function and a continuous power utility function. As for the discrete piecewise function, we assume that has the form where and are step functions. Piecewise functions are well motivated in practice and in theory; see, e.g., [66,67,68,69]. As for the continuous power utility function, we assume the form Power utility functions are widely used in stochastic inventory management due to their general structure; see, e.g., [70,71]. We further let be the maintenance cost of the warehouse at time .

- Variable cost. When the order arrives, the warehouse is replenished up to level and all components undergo a complete upgrading such that the system resumes operation as good as new with N operating components. Let be the cost of each purchased component, and let be the cost of upgrading an operating component at phase to as good as new (alternatively, can be considered a salvage cost). When the order arrives, the number of purchased components is random, depending on the stock level upon arrival. Specifically, if the order arrives at time t, the number of purchased components is (note that the number of upgraded components is N). It is reasonable to assume that is increasing in that and, therefore, that is decreasing in . It is further assumed that since is the cost of replacing a broken component by a new component from the warehouse.

The costs of the emergency order

The emergency cost has three components: the fixed order cost, the warehouse cost, and the variable cost. Specifically:

- Emergency cost. An emergency supply incurs a fixed cost and a variable cost of for each supplied component. For simplicity, we assume that includes the fee for canceling the order (under policies (a) and (b)). As in practice, and An emergency supply is placed only when no new components are left in the stock, and an operating component fails. Thus, the emergency supply includes components at a cost In addition, we have a cost of + for maintenance activities of the warehouse and for upgrading the system (under policies (a) and (b)). It is reasonable to assume the same warehouse and upgrading costs for both regular and emergency orders; usually, in practice, the very arrival of the emergency supply constitutes the main cost, and all associated costs do not differ much.

To derive the costs, we use renewal theory and PH properties. To that end, let be the expected discounted cycle length using the discount factor , i.e., . Let and be the expected discounted replacement cost, fixed cost, warehouse cost, variable cost, and emergency cost, respectively. Similarly, let and be the corresponding expected discounted costs per cycle. Applying renewal theory, we can express the costs as follows:

The expected discounted total cost is thus

To provide a complete and exhaustive investigation of the three different emergency policies, our analysis is structured hierarchically in three stages. We start with the policy (Section 5). Using the approach for the policy as a baseline, we expand our analysis to the second policy (Section 6). The third policy completes our analysis (Section 7).

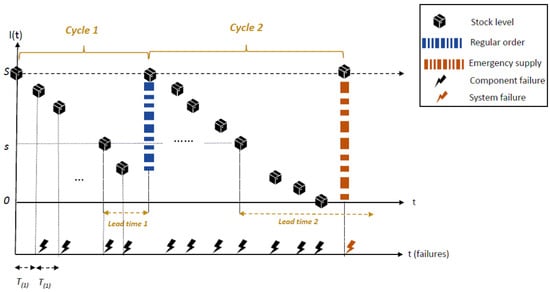

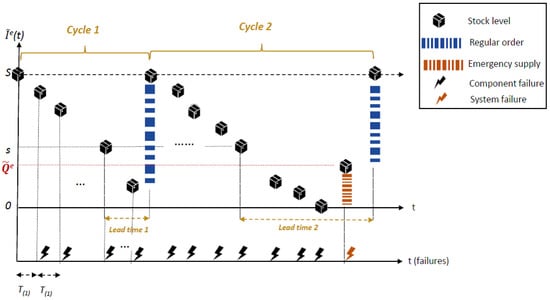

5. The Policy

The policy assumes that i.e., each time an emergency order is placed, the stock is replenished with S new components, the regular order is canceled, and a complete maintenance of the warehouse and the system is carried out. Here, the cycle ends when either the regular order or the emergency order arrives. The time indicates the arrival time of the j-th order. At times the process starts at state with probability Figure 1 depicts a typical sample path of the stock level (). The blue vertical line represents the regular order, and the red vertical line represents the emergency order. The yellow dashed arrows indicate the lead times. Component failures are indicated by black lightning symbols, and a system failure (the critical failure, when drops to ) is indicated by a red lightning symbol. Figure 1 illustrates two cycles. The first cycle ends with the arrival of the regular order (when is positive). By contrast, the second cycle ends with the arrival of the emergency supply (when drops to zero and the system fails). In the event of a system failure, an emergency supply of new components arrives, the cycle ends, and the pending regular order is canceled. (To emphasize this cancelation, the theoretical residual lead time 2 is indicated by the continuation of the dotted yellow dashed arrow in the figure).

Figure 1.

A typical sample path of under the policy.

We denote by and by the number of new components in the warehouse just before the arrival of the j-th order. Similarly, we denote by the phases of the N operating components just before the arrival of the j-th order. Next, we use the generic form and i.e., the time, the number of new components, and the phases of the operating components just before the arrival of the first order, respectively. We further let be the set of states of the form , and we let be the set of states of the form . It is easy to see that the pair has state space State space describes the states when the regular order arrives, and describes the states when the emergency order arrives. Our aim is to derive the cost functions and the optimal thresholds and that minimize the expected total cost.

We assume an initial state with probability and start by addressing the stopping time variable as a key variable in our analysis. The derivation of the cycle length and the costs are as follows.

The variable

and its application

The stopping time, represents the time until the i-th component’s failure. Special attention is given to the time until the first component’s failure, , which is the minimum of N independent PH renewal processes. Following Section 3(c), of order with and LST matrix The variable is used mainly to derive the matrix with less computational effort than the use of Equation (4) requires.

Lemma 1.

The matrix can be derived using of order as follows:

Proof.

Consider N independent operating components, each of which has a distributed life span. Since is the time until the first component fails, the time can be written as

Given the time and the phase the memoryless property of the exponential distribution implies that the processes and are conditionally independent. Thus, the time until the next component fails, is stochastically identical to , with the exception of the state Thus, we have By Equation (9), we obtain

□

5.1. Cycle Length and Related Costs

Each cycle is composed of two periods: the time from the beginning of the cycle to the time that components fail, after which a regular order is placed, and the time from to the arrival of next replenishment (either by a regular or emergency order). Applying the strong Markov property, we can express the cycle length C as

where is the time of the second period. Accordingly, the expected discounted cycle length is

Claim 1.

The vector is given by

Proof.

We start with the following decomposition:

Applying (1) and (10), the first term of (14) is the matrix

For the second term of (14), we use the equality

The multiplication by the vector yields that is the LST of the lead time Y, which is an exponentially distributed r.v.:

In addition, applying (1) yields

Substituting (17) and (18) into (16) and rearranging yields

Substituting (19) and (15) into (14) completes the proof. □

Corollary 2.

The fixed order cost and the warehouse cost are charged once per cycle. Specifically, the fixed cost is charged at time and the warehouse cost is charged at the beginning of the cycle. Thus, it is easy to see that

5.2. Replacement Cost

Each failed component is replaced immediately by a new component from the warehouse, if available, at a cost . Let be the number of replaced components per cycle, and denote by the time of the k-th replacement. The expected discounted replacement cost is given by

The first term is the initial probability vector of the N operating components. Here, we need to follow the phases of the operating components at the time of each replacement, since the system continues operating. Each component failure belongs to either one of the first failures (after which a regular order is placed) or one of the component failures during the lead time (maximum s failures). Thus, satisfies the next relation:

Substituting (21) into (20) yields

To derive Equation (22) in a more structured way, we first present the next definition and the following Lemma.

Definition 1.

Let be the expected accumulated discounted time until k component fail, i.e.,

Lemma 2.

The term satisfies

It is easy to verify Lemma 2 using the equality and the formula of the finite geometric series sum.

Claim 2.

The replacement cost per cycle is given by

Proof.

The first term is the expected accumulated discounted time until From that point on (with LST ), failed components are replaced (up to s components) as long as the pending regular order has not arrived. By (1) is the expected accumulated discounted time until that event. Multiplying by completes the proof. □

5.3. Variable Cost

Here, we include the cost of the purchased items and the cost of upgrading the system when the order arrives. Assume that the regular order arrives when i components are in the warehouse, i.e., Then, the warehouse is replenished with new components at a cost of per component. Recall that is the cost of upgrading an operating component at phase to as good as new. Let be the upgrading cost vector whose entry is given by

It is easy to verify that if upon arrival, then the variable cost is

Claim 3.

The variable cost is given by

Proof.

The variable cost satisfies

The term is the discounted time a regular order is placed. Assume that and i.e., the order arrives before the system fails. Then, a cost of is incurred. Otherwise, an emergency order is placed. Specifically, assume that components fail during the lead time, i.e., Equation (28) can then be written as

When the lead time includes two periods: the time until the k-th failure, , and the time until the regular order arrives, Let be the residual lead time, such that Given the time and the exponential memoryless property yields that is also an exponentially distributed r.v. at rate and therefore, and have the same distribution. In matrix form, we have

Applying (1) and yields

To complete the derivation, we derive Note that, here, we need to consider the phases of the N operating components (since the cost of upgrading an operating component is a function of its phase). To do so, we refer to Section 3.2 of Latouche and Ramaswami [65]. In Section 3.2 of [65], it is shown that for a renewal process of , the matrix with elements

takes the form . For N i.i.d. PH renewal processes, we have the matrix . Thus, is given by

Substituting (31) and (32) into (29) completes the proof. □

5.4. Emergency Cost

The emergency cost includes the fixed order cost, , the component cost, and the upgrading cost of the remaining components at phase . Similarly, we let be the upgrading cost, whose entry is given by

Assume that then, the emergency cost at the time of ordering is .

Claim 4.

The emergency costis given by

Proof.

We present only the key steps of the proof. The emergency supply arrives at time given that . Hence, we have

where

Recall that when s components fail, the system continues operating. Thus, for each of the s failures, we apply the matrix Then, in the next component failure, the system stops operating. Here, we apply the matrix by replacing with since no replacement is carried out. Substituting (36) into (35) yields (34) □

5.5. Example 1

Our basic example includes a system with components operating in parallel. Each component has a phase-type distributed life span with phases and

i.e., the life span of each component includes three phases that last an exponential time at rates 2, 1.5 and 1, respectively. We assume an exponentially distributed lead time at rate , and a discount factor The cost structure includes a replacement cost and upgrading cost vector

Clearly, the warehouse capacity affects the maintenance cost, the holding cost, and the number of components ordered (since each regular order replenishes the warehouse to its maximum capacity). Thus, it is important to investigate how the system’s performance is impacted by the warehouse size. On the one hand, the larger the warehouse, the more new components there are in stock, and hence the less likely the need for an expensive emergency supply. On the other hand, the cost of replenishing and maintaining the warehouse increases as a function of its size. As discussed in Section 4.1, there are several cost structures that can be taken into consideration. We model the warehouse cost by using two structures, namely, a discrete piecewise function and a continuous power utility function. For each cost structure, we define a concave, a linear, and a convex function (for a total of six warehouse cost functions). The piecewise functions are denoted by the power utility functions are denoted by The index refers to concave, linear, and convex functions, respectively. The functions and for are given in Equation (38)

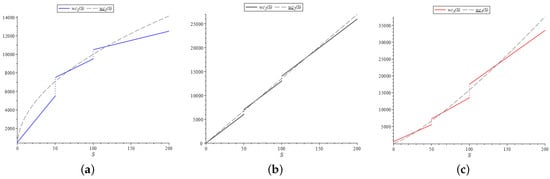

Figure 2a–c shows the curves for the concave, linear, and convex warehouse costs for , respectively; the piecewise functions, are indicated by the solid curves; and the power utility functions, are indicated by the dashed curves.

Figure 2.

(a) The warehouse costs , . (b) The warehouse costs , . (c) The warehouse costs , .

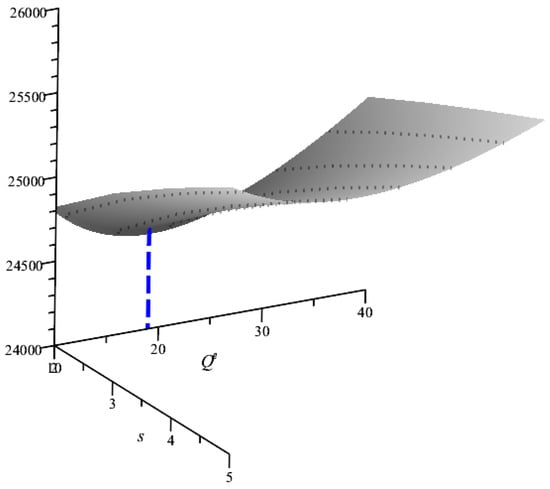

Our aim is to find the optimal thresholds and that minimize the expected total cost Unfortunately, the cost functionals are too complicated to be mathematically interpreted, and so we use a numerical analysis; we use Maple 2023.1 for our numerical investigation. Figure 3a–c shows as a function of S and s for , and respectively. We see that, while is convex in S and and are piecewise convex functions (i.e., convex within each range of S). We note that displays a similar convexity property in all our numerical examples. Thus, the search for and can be easily accomplished by a simple linear search (for the continuous functions and within each range for the piecewise functions).

Figure 3.

(a) for the warehouse costs . (b) for the warehouse costs . (c) for the warehouse costs .

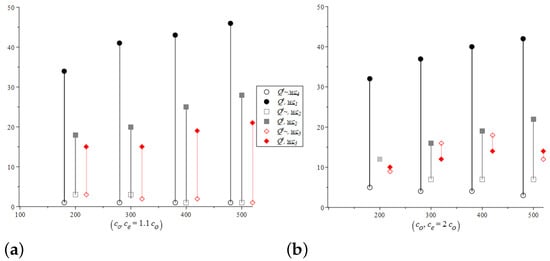

An emergency order is expensive; experience shows that it can cost up to twice as much as a regular order. Hence, we assume that and . We further study the system’s performance for two values of : a relatively high cost (i.e., 10% higher than the regular cost), and an extremely high cost, (i.e., 100% higher than the regular cost). Table 1 presents the optimal thresholds and cost and as functions of and the top and bottom sub-tables refer to and respectively.

Table 1.

, and and for (top sub-table), and (bottom sub-table).

In order to investigate the system’s performance as a function of and more numerical analyses have been conducted (which are not reported here). Below is a summary of our main conclusions.

- (i)

- The total expected cost is (piecewise) convex with respect to the thresholds S and which makes it easier to derive the optimal thresholds.

- (ii)

- The optimal thresholds and the optimal cost are decreasing in and That is, the shorter the lead time, the more economically profitable it is for the company to place more frequent but smaller orders. As expected, increasing the discount factor leads to a delay in ordering.

- (iii)

- The optimal threshold (reorder point) is hardly affected by the warehouse cost type (whether linear, concave, or convex). By contrast, the optimal threshold is significantly affected; we see that a concave cost (whether piecewise or continuous) yields a higher and hence a larger difference Since a concave function implies a decreasing marginal cost and exhibits economies of scale, it is economically profitable for the company to place fewer but larger orders.

- (iv)

- Our results show that for the same and We believe that this result mainly depends on the functions themselves and cannot be an absolute conclusion.

- (v)

- As expected, increasing increases ; this holds for all warehouse cost functions.

- (vi)

- Increasing increases and , with a more significant increase observed for Obviously, for a very high emergency cost, the best strategy is to reduce the number of emergency orders by increasing the regular order (i.e., setting a higher ).

6. The Policy

We next extend the policy by considering an emergency supply of an arbitrary quantity Since an emergency order is more expensive than a regular order, it may be economically feasible to partially replenish the warehouse with fewer components (enough to keep the system operating), rather than completely replenish the warehouse with S components. Under the policy, we assume that when drops to level s, a regular order is placed. However, if during the lead time a component fails and no new components are available in the warehouse, an emergency order of a fixed quantity () is ordered and received in a negligible amount of time at a premium cost. Here, too, the emergency order cancels the pending regular order, and when drops to s again, a new regular order is placed. Clearly, the policy is a special case of the first policy, where . We further emphasize that the complete maintenance of the warehouse and the system is carried out upon arrival of both orders (regular and emergency). Note that the regular order may be placed several times per cycle (due to cancellations), but only one of them is implemented, thus ending the cycle. Accordingly, an emergency supply may be placed several times per cycle.

In what follows, we use superscript e to denote functions under the policy. Let be the stock level under the policy, and let be the arrival time of the j-th regular order. The stopping times are regenerative points for . Denote by the generic form of . Figure 4 depicts a typical sample path of under the policy. We see that in the first cycle (Cycle 1), the lead time (Lead time 1) ends when thus, the warehouse is replenished up to S and the cycle ends. In the next cycle (cycle 2), a component fails during the lead time (lead time 2) when Thus, an emergency order is placed, the warehouse is replenished up to level and the pending regular order is canceled (as indicated by the yellow dashed arrow of Lead time 2). When again drops to level s, a new regular order is placed, and, this time, the cycle ends after lead time 3.

Figure 4.

A typical sample path of under the ( policy).

We first derive the expected discounted cycle length and then the cost functionals. The proofs are analogous to those in Section 5, and therefore, we omit all but the key steps.

6.1. Cycle Length

Let be the residual cycle length when and let be its LST vector. Claim 5 is obtained by applying the first step expectation technique.

Claim 5.

The expected discounted cycle length is given by

Proof.

Equation (39) is straightforward. Consequently, it is easy to verify that the vector satisfies the following decomposition:

Note that a regular order arrives only when , at which point the cycle ends. The last term of (41), is given by (39) with replacing We emphasize that a complete maintenance is performed upon the arrival of both orders, regular and emergency, after which the phases of the operating components are chosen according to the vector (with a matrix probability form ). Substituting (19) and (15), rearranging, and solving for completes the proof. □

6.2. Cost Derivations

Let and be the warehouse, replacement, order (fixed and variable), and emergency costs per cycle, respectively. Let be the residual replacement cost vector when (i.e., k components are in the warehouse). Accordingly, let and be the warehouse, order (fixed and variable), and emergency cost vectors respectively when there are s components in the warehouse. In the next proposition, we integrate the recursive technique and the first-step expectation technique to make the derivation simpler and structured.

The expected discounted costs per cycle are given by

- (The warehouse cost)

- (The replacement cost)

- (The fixed order cost)

- (The variable cost)

- (The emergency cost)

Proof.

We start with Equation (42) A warehouse cost is incurred each time an order arrives, be it regular or emergency. Similar to Equation (41), can be written as

where is obtained by substituting instead of S into Substituting (19) and (15) and solving for yields Equation (42) Next, we consider Equation (43) with the replacement cost . When a component fails before the lead time ends (with LST ) and no new component is available in the warehouse, an emergency supply replenishes the inventory to level , and the remaining replacement cost is thus . The cost for is straightforward. Finally, consider Equations (44) and (46) with and respectively. The fixed order cost is incurred when a regular order is placed, whereas the cost is incurred when each time an emergency order is placed. Thus, it is easy to verify that and satisfy

where and are obtained by substituting instead of S into and respectively. The matrix in Equation (48) is due to the fact that we need to follow the phases of remaining components for the derivation of the upgrading cost. When the emergency supply arrives, is replenished to level . Solving for and and noting that completes the derivations. Finally, is obtained by applying similar techniques to those of Equation (27). □

6.3. Example 2

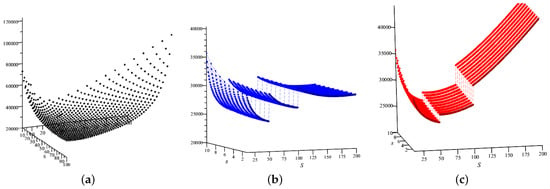

We start by studying the behavior of the total cost as a function of and To do so, we consider the set and the warehouse cost . Similar to Example 5.5, we let and fix (see Table 1). Figure 5 depicts for varying in and varying in We see that is convex in and , which makes the search for the optimal thresholds easier (here, we obtain and , as indicated by the blue dashed line in Figure 5). We note that, although we did not prove it, displays a similar convexity property in all our numerical examples.

Figure 5.

The total cost ).

Our goal is to examine whether partial orders, i.e., when , are economically profitable. To do so, we assume that the company keeps the inventory at optimal thresholds and derive the optimal emergency supply . We consider two cases. In Case , we assume that and (as in Table 1) and derive level , which minimizes In Case , we assume that and derive the levels and that minimize Table 2 presents the results for and The results for Cases and are marked in red and blue, respectively; the black values are taken from Table 1.

Table 2.

(a) The optimal thresholds for Cases and (marked in red and blue, respectively) when . (b) The optimal thresholds for Cases and (marked in red and blue, respectively) when .

As expected, comparing the results of Cases and to the results in Table 1 shows that

To quantify the cost savings by letting we further calculate the savings percentages, and which are given by

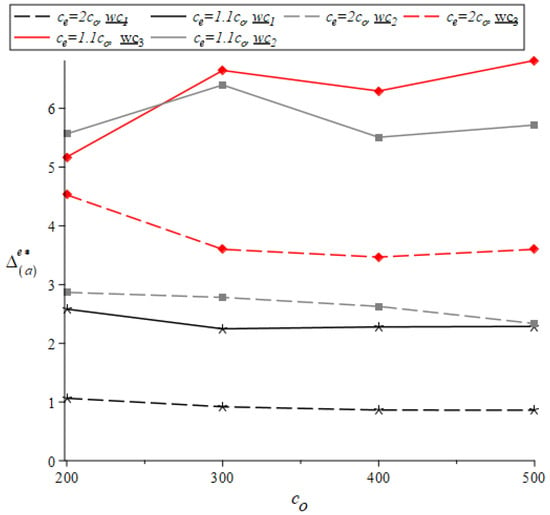

The percentages and are indicated in the red and blue parentheses in Table 2, respectively. In addition, Figure 6 curves for (solid lines) and (dashed lines). The black, gray, and red lines in the figure refer to respectively. Similarly, in Figure 7 represents the curves, and the black, gray, and blue lines refer to respectively.

Figure 6.

as a function of , and .

Figure 7.

as a function of , and .

Conclusions

- (i)

- The total cost is convex in and , which makes the search for the optimal thresholds easier.

- (ii)

- An emergency supply with yields a cost savings (of up to 8%) even when we preserve and (Case ). Clearly, when optimizing both and , the cost savings increase, as expressed by (which is less than ).

- (iii)

- In most cases, the benefit of ordering is higher when the warehouse cost function is convex (especially for high and as indicated by the red line in Figure 7 and the blue line in Figure 7). Thus, when the warehouse cost exhibits diseconomies of scale, it is recommended that decision makers invest effort in determining the optimal emergency supply and, if possible, the optimal threshold as well.

- (iv)

- Regarding Case , Figure 6 shows that the economic advantage of deriving is relatively constant for the different values. We further see that is increasing in and decreasing in Clearly, when the regular order is expensive (i.e., has a high ), the benefit of an emergency order increases, and thus increases). We further see that is smaller for a convex cost function, probably to save cost.

- (v)

- Regarding Case , Figure 7 shows that is slightly increasing in . In contrast to the slight decrease in for Case (a), we observe a significant decrease in when compared to when . In order to optimize (usually to , we can decrease the emergency order (i.e., reduce ), especially when the emergency cost is high. Moreover, the low values of (compared to those of Case ) are probably due to the fact that, since the regular order is canceled, it is economically profitable to delay the time of ordering (i.e., decrease ) thereby taking full advantage of the emergency supply.

7. The Strategy

The above policies assume that placing an emergency order entails the cancelation of the regular order. However, since emergency orders are very expensive, it is worthwhile to investigate the benefit of replenishing the warehouse with a safety stock while awaiting the regular order. Specifically, we introduce the policy for , which operates as follows: when the stock level drops to s, a regular order is placed. However, if during the lead time a component fails and no new component is available in the warehouse, an additional (emergency) order of a specified fixed size is placed. Upon arrival, the warehouse is replenished with new components, one component replaces the broken component, and the system resumes operation. As before, this safety emergency supply is received in a negligible amount of time at a premium cost. We emphasize that the aim of this safety emergency supply is to prevent a system failure and serves as a temporary source of supply, in addition to the regular one. Thus, the complete maintenance of the warehouse and the system is performed only when the lead time ends and the regular order arrives. We further note that during the lead time, additional regular orders are not allowed (so that no crossover occurs); however, subsequent safety emergency supplies may be placed to prevent a system failure.

To clarify, we highlight the main points of comparison between the and policies:

- (i)

- Under both policies, when the inventory drops to level a regular order of up to S new components is placed. Upon arrival, the complete maintenance of the warehouse and the system is performed.

- (ii)

- Under both policies, if a component fails and no new components are available in the warehouse, an emergency order of () new components is placed.

- (iii)

- Under the policy, a pending regular order is not affected when an emergency order is placed. Under the policy, the emergency order replaces the regular order.

- (iv)

- Under the policy, maintenance is performed only when the regular order arrives, after which the cycle ends.

- (v)

- Under the policy, maintenance is performed when both orders arrive. Note that if the cycle ends when both orders arrive, whereas if the cycle ends when only the regular order arrives.

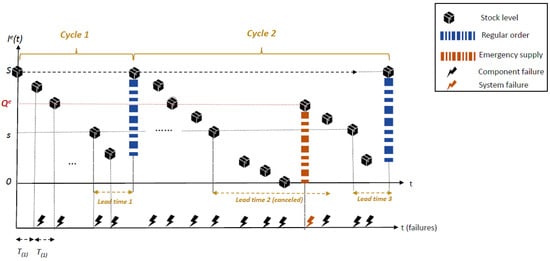

In what follows, we use the symbol ~ to indicate terms associated with the policy. Let be the stock level at time , let be the arrival time of the j-th regular order, and let be the generic form of the cycle length. Clearly, and are the regenerative points of . Figure 8 demonstrates a typical sample path of under the policy. Here, Cycle 1 ends without an emergency order, and therefore, it is stochastically similar to Cycle 1 in Figure 1 and Figure 4. By contrast, during Cycle 2, a component fails when the stock is empty, and therefore, an emergency order is placed. Figure 8 highlights that the regular order is not affected and arrives after lead time 2, after which the cycle ends.

Figure 8.

A typical sample path of under the policy.

Let be the i-th arrival time of the emergency supply. At times the stock level is replenished with new components and one new component replaces the broken one in the system (its phase is chosen according to the probability vector . Thus, the times are semi-regenerative points of with . Recall that since no maintenance is performed at time the phases of the operating components are kept for the continuity of the system.

7.1. Cycle Length and Related Costs

A regular order is placed once per cycle, after which the cycle ends. Thus, we have

Since we have

Corollary 3.

Similar to Corollary 2, the fixed order cost and the warehouse cost are charged once per cycle. Specifically, the fixed cost is charged at time and the warehouse cost is charged at the beginning of each cycle (which is also the end of the previous cycle). Thus, it is easy to see that the fixed and warehouse costs per cycle ( and respectively) are given by

Remark 1.

It should be noted that the upgrading cost is also paid once per cycle, when the order arrives. However, this cost depends on the components’ phases and requires a deeper snapshot of the system. Thus, its derivation is included in Section 7.2.

7.2. Other Costs

Let and be the replacement, variable, and emergency costs per cycle. Let be the residual replacement cost vector when Similarly, let and be the variable and emergency cost vectors, when , respectively.

Proposition 1.

The expected discounted costs are given by

- (The replacement cost)

- (The variable cost)

- (The emergency cost)

Proof.

The cost functions are derived similarly to those in Section 5 and Proposition 6.2. The main difference is that the maintenance is performed (and paid for) only when the regular order arrives. At that time, the system continues operating, and hence, the cost is not relevant. □

7.3. Example 3

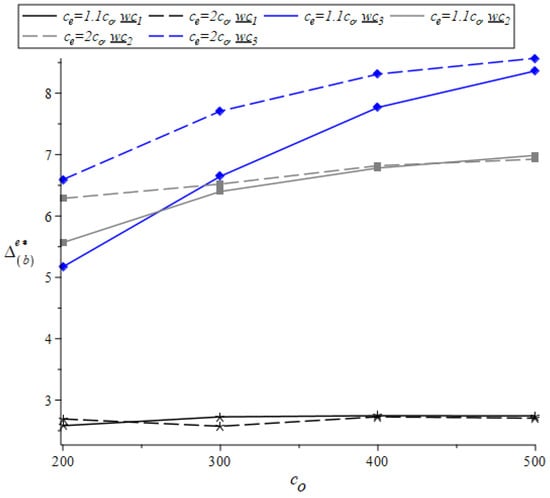

We use the same values as those of Example 6.3 (i.e., ). Here, too, we set the optimal thresholds to and (as in Table 1) and obtain the optimal emergency supply Table 3a,b tabulate the results as functions of and for and respectively. The optimal values and are marked in red. In order to better our understanding of the benefit of an emergency order and the extent of its necessity relative to the regular order, we calculate the following two measures:

Recall that and are given in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. The measure marked in black italics in Table 3, represents the benefit of ordering a smaller emergency supply. The measure marked in red in Table 3, represents the benefit of using the emergency supply as a second source of supply (and cancel the pending regular order). We see that in all cells; i.e., replenishing the warehouse with such a small safety stock may yield significant cost savings. By contrast, the effectiveness of canceling the pending regular order is questionable. To highlight this point, all cells in Table 3, where are colored yellow. It can be seen that when the emergency cost is high (either or ) or the warehouse cost is convex (i.e., with diseconomies of scale leading to increasing marginal costs), it is economically profitable to cancel the pending regular order when placing an emergency one. That is, when the emergency supply is expensive, it pays to take full advantage of it by increasing its size and canceling the pending regular order (see also Figure 9 below).

Table 3.

(a) The thresholds and for . (b) The thresholds and for .

Figure 9.

(a) and when . (b) and when .

To compare the optimal emergency order threshold to , we use a graphical illustration. Figure 9a,b curve and for and respectively; is indicated by solid shapes and by hollow ones (here, we take ). In each figure, the black, gray, and red shapes refer to , and respectively. Figure 9a shows that when , By contrast, when Figure 9b shows that decreases, increases, and, hence, the difference decreases (and we even obtain ; see the results for . These changes are consistent with the discussion above.

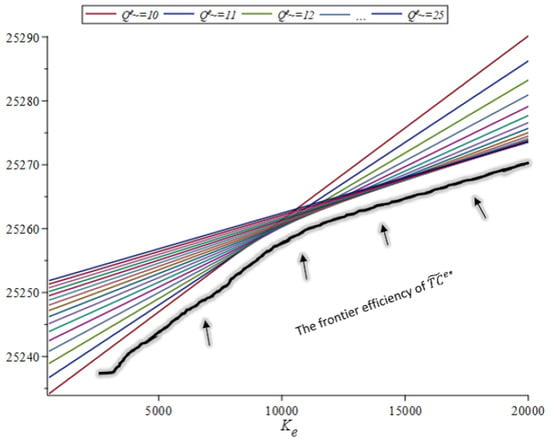

Furthermore, increasing reduces the economic savings of the emergency supply. To increase the impact of , we assume and a cost where Figure 10 depicts the total cost for We see that for a relatively low (high) , the cost is increasing (decreasing) in The immediate implication of this is that increasing increases the optimal emergency order threshold . Figure 10 further shows that setting the optimal the frontier efficiency curve of exhibits economies of scale (i.e., a decreasing marginal cost; see the black curve highlighted with arrows in Figure 10).

Figure 10.

The total cost for .

Conclusions

- (i)

- The total cost is convex in (although we did not prove this, it has been observed in all our numerical results).

- (ii)

- A convex warehouse cost function yields a higher optimal emergency order threshold As a result, the regular order is smaller, which leads to cost savings. Comparing the results for and surprisingly shows that the latter yields a higher ; the higher thresholds and are probably responsible for this increase. Furthermore, Table 3a,b shows that increasing increases to obtain a full utilization of the emergency supply.

- (iii)

- (iv)

- As expected, increasing and decreases the benefit of the emergency order. We see that that is, replenishing the warehouse with an immediate and relatively small safety stock may yield significant cost savings (of up to 15%), in particular when and are low. By contrast, the decision whether to cancel the regular order is not straightforward. It is noteworthy that the higher the emergency cost ( ) and the warehouse cost ( ), the more economically profitable it is to cancel the regular order. The logic here is that if the expensive emergency order has already been placed, the regular order is not needed, and therefore it is canceled.

8. Concluding Remarks and Further Research

This paper studies a multi-component system, where each component has a random life span and is subject to failure. The system is supported by a warehouse with a limited capacity S. Two types of orders can be placed: a regular order and an emergency order. We study three emergency supply policies that differ from each other in size and in relation to the regular order. We start with , and extend it to where in both cases, the regular order is canceled when an emergency order is placed. The third policy assumes that the regular order is not canceled when the emergency order is placed. Numerical results show that the total cost is convex as a function of and the optimal threshold , particularly when the warehouse cost is high. In this case, the benefit of ordering less than the maximum capacity is higher. Increasing the emergency cost and the warehouse cost increases the benefit of canceling the regular order and increases . Meaning that it is economically profitable to place fewer but larger emergency orders. When the emergency cost is relatively low, the emergency order may yield significant cost savings, but with a smaller order quantity and in addition to the regular order.

There are several avenues for future research. In this paper, we assume the base-stock policy for the regular order. We believe that the tools used here can be applied to other base-stock inventory policies with emergency supply, such as the policy. Under the policy, when the stock level drops to there is a regular order of fixed size if during lead time the level drops to zero, an emergency order is placed up to level . The assumption that implies that there is at most one regular order at any given point in time. Since the stock level is not known at the order arrival time, there are no natural renewal cycles at replenishment times. Thus, the analysis under the policy is more challenging but worthwhile [35]. We further note that the policy is well applied in practice; see [13,72]. Here, too, different policies with emergency orders that differ from each other in size and in relation to the regular order can be investigated.

Motivated by Songet al. [7], a second interesting and practical extension would be to assume a phase-type distributed lead time for the regular order (or a general distribution) rather than an exponential one. It is not unusual for an order to go through several sequential procedures, each of which takes a random (probably exponential) period of time; e.g., supplier selection, order confirmation, quality check, etc. The total time in the procedures can be represented by the phase-type distribution, since the phase distribution is constructed of different phases, each with an exponential distribution. In this case, the lead time may be longer and, thus, an emergency supply plays an even more dominant role in preventing system failure.

The third extension would be to assume a fixed or random lead time for the emergency supply. Real-world examples show that an emergency supply is sometimes also accompanied by some lead time, which, albeit shorter, is not negligible; see, e.g., [35]. Clearly, this significantly complicated the analysis since we assume two stochastic lead times, for the regular order and for the emergency one. We further note that studying the policy with random (but different) lead-time distributions is certainly a rich and challenging extension.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.B.; methodology, Y.B.; software, C.B.; validation, C.B.; formal analysis, Y.B.; investigation, Y.B. and C.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.B.; writing—review and editing, Y.B. and C.B.; supervision, Y.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

In Table A1, we summarize the most relevant literature studies concerning inventory and reliability models under the base-stock policy.

Table A1.

Inventory and reliability models under the base-stock policy.

Table A1.

Inventory and reliability models under the base-stock policy.

| Base-Stock Inventory/Reliability Models | Paper | Demand/Life Span | Shortage Policy | Regular Order Policy | Emergency Order Policy | Additional Features and Solution Method | Optimization Criterion |

|

| Keizer et al. (2017) | Poisson | System Shutdown | (s, S, T) | No emergency |

| Long run average |

| Fixed L.T. |

| ||||||

|

| Boucherie et al. (2018) | Poisson | Backlog | (n, S) | (S−1,S) |

| Long run average |

| General L.T. | Fixed L.T. |

| |||||

|

| Kouki et al. (2018) | Poisson | Lost sales, Backorder | (S−1, S) | (Ŝ, S) |

| Long run average |

| Fixed L.T | Fixed L.T. |

| |||||

|

| Rahimi-Ghahroodi et al. (2019) | Poisson | Partial backlog | (S−1, S) | (S−1, S) |

| Long run average |

| Exp L.T. | Zero L.T. |

| |||||

|

| van Wingerden et al. (2019) | Poisson | System shutdown | (S−1, S) | Fixed |

| Long run average |

| Fixed L.T. |

| ||||||

|

| Poormoaied et al. (2020) | Poisson | Backlog | (s, S, T) | (u, s) |

| Long run average |

| Zero L.T. | Zero L.T. |

| |||||

|

| Barron (2022) | Fluid + MAP | Lost sales | (s, S) | (0, Se) |

| Discounted |

| Exp L.T. | Zero L.T. |

| |||||

|

| Guo et al. (2022) | General | System shutdown | (T, s, S) | No emergency |

| Long run average |

| Fixed L.T. |

| ||||||

|

| He & Gao (2023) | Bernoulli(p) | System shutdown | Fixed times | Fixed times |

| Long run average |

| Fixed L.T. | Fixed L.T. |

| |||||

|

| Basten & Houtum (2023) | Poisson | Limited Backlog | (S−1, S) | (S−1, S) |

| Long run average |

| Exp L.T. | Fixed L.T. | ||||||

|

| Boxma et al. (2023) | Release rate function | Lost sales | (Qn, rn) | (Qe, re) |

| Long run average |

| Exp L.T. | Exp L.T. |

| |||||

|

| This study | Phase-type | No shortage | (s, S) | 3 policies of (0,Qe)-type |

| Discounted |

| Exp L.T. |

| ||||||

References

- Turrini, L.; Meissner, J. Spare parts inventory management: New evidence from distribution fitting. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 273, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, C.; Marklund, J.; Tan, T.; Reijnen, I. Inventory control in a spare parts distribution system with emergency stocks and pipeline information. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2015, 17, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulaksil, Y.; Hamdouch, Y.; Ghoudi, K.; Fransoo, J.C. Comparing policies for the stochastic multi-period dual sourcing problem from a supply chain perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 232, 107923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, S. A review of the joint replenishment problem from 2006 to 2022. Manag. Syst. Eng. 2022, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poormoaied, S.; Atan, Z.; de Kok, T.; Van Woensel, T. Optimal inventory and timing decisions for emergency shipments. IIE Trans. 2020, 52, 904–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selçuk, B. An adaptive base stock policy for repairable item inventory control. Int. Prod. Econ. 2013, 143, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.S.; Xiao, L.; Zhang, H.; Zipkin, P. Optimal policies for a dual-sourcing inventory problem with endogenous stochastic lead times. Oper. Res. 2017, 65, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipkin, P. Old and new methods for lost-sales inventory systems. Oper. Res. 2008, 56, 1256–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahmias, S. Perishable Inventory Systems; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 60. [Google Scholar]

- Scala, N.M.; Rajgopal, J.; Needy, K.L. A base stock inventory management system for intermittent spare parts. Mil. Oper. Res. 2013, 18, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dendauw, P.; Goeman, T.; Claeys, D.; De Turck, K.; Fiems, D.; Bruneel, H. Condition-based critical level policy for spare parts inventory management. Comput. Ind. 2021, 157, 107369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaesmen, I.Z.; Scheller-Wolf, A.; Deniz, B. Managing perishable and aging inventories: Review and future research directions. In Planning Production and Inventories in the Extended Enterprise; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 393–436. [Google Scholar]

- Kouki, C.; Jemaï, Z.; Minner, S. A lost sales (r,Q) inventory control model for perishables with fixed lifetime and lead time. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 168, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, M.; Eldemir, F. Application of (Q,R) policy for non-smooth demand in the aviation industry. In Industrial Engineering in the Industry; Caisir, F., Akdag, H.C., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, S.; Wang, W.; Cho, S.; Yan, H. Reducing emissions in transportation and inventory management: (R,Q) Policy with considerations of carbon reduction. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 269, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Song, Z.; Piao, S. Analysis research on the lateral replenishment strategy of the chain supermarket fresh agricultural products. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2015, 8, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tovia, F.; Whitt, B. Implementing a dynamic Inventory model in a perishable frozen warehouse. In Proceedings of the 2010 Industrial Engineering Research Conference; Johnson, A., Miller, J., Eds.; IEEE Computer Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mallidis, I.; Iakovou, E.; Dekker, R.; Vlachos, D. The impact of slow steaming on the carriers’ and shippers’ costs: The case of a global logistics network. Transp. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2018, 111, 18–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuts, M.F. Matrix-Geometric Solutions in Stochastic Models: An Algorithmic Approach; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Neuts, M.F.; Takahashi, Y. Asymptotic behavior of the stationary distributions in the GI/PH/c queue with heterogenous servers. Z. Wahrscheinlichkeitstheorie Verw Geb. 1981, 57, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmussen, S. Matrix-analytic models and their analysis. Scand. J. Stat. 2000, 27, 193–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Castro, J.E. Complex multi-state systems modelled through marked Markovian arrival processes. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 252, 852–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, Y. The continuous (S, s, Se) inventory model with dual sourcing and emergency orders. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 301, 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moinzadeh, K.; Schmidt, C.P. An (S-1,S) inventory system with emergency orders. Oper. Res. 1991, 39, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohi, T.; Kaio, N.; Osaki, S. Continuous review cyclic inventory models with emergency order. J. Oper. Res. Soc. Japan. 1995, 38, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, B.C.; Dohi, T. Cost-effective ordering policies for inventory systems with emergency order. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2009, 57, 1336–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.S.; Zipkin, P. Inventories with multiple supply sources and networks of queues with overflow bypasses. Manag. Sci. 2009, 55, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allon, G.; Van Mieghem, J.A. Global dual sourcing: Tailored base-surge allocation to near- and offshore production. Manag. Sci. 2010, 56, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, Y.; Hermel, D. Shortage decision policies for a fluid production model with MAP Arrivals. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2017, 55, 3946–3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouki, C.; Babai, M.Z.; Minner, S. On the benefit of dual-sorcing in managing perishable inventory. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 204, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axsäter, S. An improved decision rule for emergency replenishments. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 157, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Axsäter, S.; Dou, Y.; Chen, J. A real-time decision rule for an inventory system with committed service time and emergency orders. Eur. J. Oper. 2011, 215, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, Y. Group maintenance policies for an R-out-of-N system with phase-type distribution. Ann. Oper. Res. 2018, 261, 79–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haughton, M.; Isotupa, K.S. A continuous review inventory system with lost sales and emergency orders. Am. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 8, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Boxma, O.; Perry, D.; Stadje, W. Stationary analysis of an (R,Q) inventory model with normal and emergency orders. J. Appl. Probab. 2023, 60, 106–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoboda, J.; Minner, S.; Yao, M. Typology and literature review on multiple supplier inventory control models. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 293, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guajardo, M.; Rönnqvist, M.; Halvorsen, A.M.; Kallevik, S.I. Inventory management of spare parts in an energy company. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2015, 66, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Shi, Q.; Guo, C. Multi-period spare parts supply chain network optimization under (T,s,S) inventory control policy with improved dynamic particle swarm optimization. Electronics 2022, 11, 3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chu, J.; Mao, W. An optimum condition-based replacement and spare provisioning policy based on Markov chains. J. Qual. Maint. Eng. 2008, 14, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Wang, H. Joint optimization of condition-based preventive maintenance and spare ordering policy. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Wireless Communications, Networking and Mobile Computing, Dalian, China, 12–17 October 2008; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]