Abstract

The paper considers the a posteriori error estimates for fully discrete approximations of time-dependent Poisson–Nernst–Planck (PNP) equations, which provide tools that allow for optimizing the choice of each time step when working with adaptive meshes. The equations are discretized by the Backward Euler scheme in time and conforming finite elements in space. Overcoming the coupling of time and the space with a full discrete solution and dealing with nonlinearity by taking G-derivatives of the nonlinear system, the computable, robust, effective, and reliable space–time a posteriori error estimation is obtained. The adaptive algorithm constructed based on the estimates realizes the parallel adaptations of time steps and mesh refinements, which are verified by numerical experiments with the time singular point and adaptive mesh refinement with boundary layer effects.

Keywords:

Poisson–Nernst–Planck equations; a posteriori error estimates; full discrete approximations; finite element method; robustness MSC:

65N15; 65N30; 65J15; 35K61

1. Introduction

In this work, we focus on the Poisson–Nernst–Planck (PNP) equations, which are among the models for charge transport. The system serves as the basis for modeling many devices, such as semiconductor studies, electrodiffusion problems, and the dynamics of ion transport in biological membrane channels [1,2,3]. The system and its modifications have been studied with the existence, uniqueness, and stability of a solution [4,5,6].

A variety of numerical methods have been used extensively for solving PNP equations [7,8,9]. In the application of time-dependent PNP equations, the boundary layer effect due to the thin Debye layer will arbitrarily change their positions in space with the flow of time, which causes the computational cost of the solving process being very large, and the methods in [7,8,9] lose effectiveness. Therefore, solving time-dependent PNP equations with boundary layers is valuable and challenging.

The adaptive finite element method can reduce the computational complexity through nonuniform mesh distributions, which is a good method to solve time-dependent PNP equations with boundary layers. For time-dependent problem, the solving process with the parallel adaptations of time steps and mesh refinements will make the calculation more efficient. The aim of this paper is to propose an adaptive finite element method for fully discrete time-dependent PNP equations, more precisely, to provide tools that allow for optimizing the choice of each time step when working with adaptive meshes.

The a posteriori error analysis plays an important role in adaptivity techniques, which can measure the actual discrete errors without knowledge of the exact solution. With the nonlinearity and strong coupling properties of PNP equations, the a posteriori estimates and associated adaptive algorithms for time-dependent PNP equations are challenging, both for theory and computations. Such issues are, for instance, the way to analyze the a posterior error estimation of fully discrete approximations, robust estimates for strongly coupled nonlinear parabolic problems, and the algorithms for both the time step and the spatial mesh adaptivity. Then, we will explore methods to solve the difficulties through a literature review.

There have been considerable efforts devoted to overcoming the coupling of time and space for a posteriori error estimates of fully discrete approximations. Picasso [10], Verfürth [11], Chen and Jia [12], and Chami and Sayah [13] have managed to bound the error by the spatial estimators at each time step based on the error equation. Bergam, Bernardi and Mghazli [14] established an approach, and the main idea consists of uncoupling time and space errors as much as possible. According to the idea of [14], Bernardi and Verfürth [15] and Bernardi and Sayah [16,17] derived estimates of time-dependent Stokes problem, time-dependent Stokes equations with mixed boundary conditions, and time-dependent Navier–Stokes equations with mixed boundary conditions, respectively. The main estimate tool in Lakkis and Makridakis [18] is the elliptic reconstruction technique introduced by Makridakis and Nochetto [19] for the model problem of semi-discrete finite element approximation. The elliptic reconstruction leads to an appropriate pointwise representation of the error equation. Akrivis [20], and Makridakis and Nochetto [21] have applied the reconstruction technique into Crank–Nicolson and Runge–Kutta schemes. Bnsch, Karakatsani and Makridakis [22] devoted their work to an a posteriori error analysis of fully discrete finite element approximations to the time-dependent Stokes system, where estimates are based on the methodology developed in [18,19] for space discrete and in [20,21] for time discrete schemes.

For nonlinear time-dependent problem, the construction of a posteriori error estimators for fully discrete approximations is a challenge. The pioneering work of Moore [23] and Eriksso and Johnsone [24] discussed a class of nonlinear scalar problem. Verfürth [25] showed that estimates for fully discrete approximations of certain quasilinear parabolic paroblems and estimators are not computable. Moreover, ref. [25] used the framework in [26]. Babuška, Feistauer and Šolín [27] converted a parabolic or hyperbolic problem to a system of ordinary differential equations, and gave a posteriori error estimates for a general nonlinear parabolic problem with a strongly monotonic elliptic operator. Bernardi and Sayah in [17] used the theory of Pousin and Rappaz [28] to handle the nonlinear term of time-dependent Navier–Stokes equations. It is worth noting that the techniques dealing with the nonlinearity in [28] are similar to those in [26]. The situation for fully discrete nonlinear time-dependent problems, however, has not yet been as thoroughly explored.

It is worth noting that a small positive perturbation parameter leading to the solutions of PNP equations typically contains layers. We expect to have a robust a posteriori analysis of PNP equations with respect to the singular perturbation parameter. For the boundary layer effect, there are many studies on the a posterior estimation of stationary linear singular perturbation problems [29,30,31] and the nonstationary convection dominated convection–diffusion equation [27,32]. Time-dependent PNP equations have received less attention, and coupling and nonlinearity properties make the problem more difficult.

In this paper, we consider the time-dependent PNP equations which are discretized by the Backward Euler scheme in time and conforming finite elements in space. For PNP equations, the way to construct the error equation [10,11,12,13] and build elliptic reconstruction [18,19,20,21,22] by the properties of linear equations is not a good choice due to the nonlinearity and strong coupling properties of the system. Instead of using the time semi-discrete solution to decouple the error [14,15,16,17], our method consists of associating with a full discrete solution. With the full discrete solution, we can obtain a posteriori estimates through the solution existence and uniqueness of linearized equations derived by taking G-derivatives of the nonlinear system. Meanwhile, the efficient and reliable a posteriori error estimators are proved, referring to the techniques in [17,26]. The robustness of the estimator is demonstrated with an improved energy norm in view of the coupling properties of PNP equations. Based on the adaptive algorithm in [10,12], numerical experiments are conducted. Numerical results show the phenomenon of adaptive time step adjustment due to the time singular point and adaptive mesh refinement with boundary layer effects.

The paper is organized as follows. We begin in Section 2 by defining the PNP equations, its variational form, and the finite element spaces to be used. In Section 3, we verify the solution existence and uniqueness of linearized equations with details presented in Appendix A, and further develop the a poteriori error estimate with time and space. The computable, robust, effective and reliable space–time a posteriori error estimations are derived. We introduce the adaptive algorithm in Section 4, and numerical experiments are reported with showing the adaptive phenomenon in time and space, respectively. Conclusion remarks and future work are finally given in Section 5.

2. The Poisson–Nernst–Planck Equations and Their Discretization

In this work, we consider the time-dependent Poisson–Nernst–Planck (PNP) equations [9]:

which describe the nonlinear coupling of the electric potential and the ionic concentration of the i-th species, where the number of ion species is K. The first equation is called the Nernst–Planck equation for species i, and the second one is named Poisson’s equation. Here, and are the diffusivity and valence, respectively. , where is the Boltzmann constant and is the absolute temperature. e is the elementary charge, and are the relative and vacuum dielectric permittivities, and is generally the fixed charges.

The boundary conditions are a critical component of the PNP model and determine important qualitative behavior of the solution. Let be a bounded domain with Lipschitz boundary . Homogeneous no-flux conditions are considered for each charged species, i.e.,

where is the outward unit normal vector on the boundary .

The external electrostatic potential is influenced by applied potential, which can be modeled by prescribing a Dirichlet boundary condition, i.e.,

For nonhomogeneous Dirichlet boundary conditions such as , they can be transformed into homogeneous Dirichlet boundary conditions. Since the PNP equations is assumed to satisfy the no-flux boundary condition for the charge carrier concentrations, it is known that the charge carrier concentrations satisfy the conservation of mass [33].

For convenience, assuming

is a constant in system (1). Let be the initial ionic concentrations and electric potential. We use standard notations for Sobolev spaces , and the associated norms and semi-norms. Here, and , which means the dual space of . The variational form of system (1) is as follows.

To find such that

where is the valence of , the scalar product is the standard -scalar product, and is the initial value. When , there is a unique solution to the variational problem [4]. For simplicity, in the following, we choose and .

Let the quasi-uniform mesh of be with mesh size [34] and the corresponding finite element space be

and

where and .

For the time discretization, define a partition of the time domain,

where and .

. For all , , , and . Define the following scheme:

and using the Backward Euler scheme, the fully discrete form of the variational problem is as follows.

For , find such that

The initial value is the interpolation of in . Ref. [35] proved the existence and uniqueness of solutions to the above problems. By setting the test functions , we have , that is, the global mass conservation property is satisfied.

Assuming is the weak solution of system (3), where if and only if , , satisfies

Hence, the weak problem of the system (3) is to find such that

where is a nonlinear operator from to

Similarly, the finite element approximation of system (4) indicates that the full discrete approximation of problem (6) is to find satisfying,

where

The error in this work is measured in following the norm, i.e., ,

and

where .

And , we define

and where is the dual space of ,

where .

For brevity, we introduce the space

which is a Banach space [36] with respect to the norm defined by

A similar definition can be found in [11,37].

For the system (3), we have with , and .

3. The a Posteriori Error Estimates

In this section, we present a posteriori error estimates for PNP equations. In Section 3.1, we bound the error by the computable error estimator . And the lower bound of the local error in space and time is proved, respectively, in Section 3.2.

3.1. Upper Bound of Errors

For the a posteriori error studies, we use the piecewise affine function , which takes the values in the interval as follows:

And we consider the a posteriori error estimate for the error .

Our method consists of associating with such that

can be split as

and

Furthermore, for a posterior error estimates of , it can be observed that can only be reduced by changing the time step at a fixed time, then we treat the estimates of as the time a posterior error estimates. Meanwhile, the remaining part is handled as a posterior error estimates of the space. In the following discussion, we will deal with the estimates of firstly.

For the estimate about , we deal with the nonlinearity through the property of the linearized equations derived by taking G derivatives of the nonlinear system. The definition of at is as follows [38]:

which leads to the following linear problem:

Meanwhile, , that is .

For the estimate about , Lemma 2 is proved firstly. One of the important tools used in the proof of Lemma 2 is the solution existence and uniqueness of the linear problem (10), which is verified in Lemma 1. In all proofs, means , where C is a constant independent of .

Lemma 1.

If , and , there exists a unique solution of Equation (10) in .

Proof.

The proof of the lemma is referred to in [4]; see Appendix A for details. □

Lemma 2.

If , , and ψ satisfy the condition in Lemma 1, we have the regularity conclusion for Equation (10) that :

where constant is independent of , , , and ϵ.

Proof.

Due to the variational form of Equation (10) as Equation (11), we have

Due to Lemma 1, we have the one-to-one mapping . By the bounded inverse theorem, there exists an inverse → and ,

with and , we have

and Equation (12) is proved with independent of , , , and . □

Theorem 1.

If , , and ψ satisfy the condition in Lemma 1, and , then

where are constants in Equation (12) in taking .

Proof.

Denote . The definition of the G derivative [38] indicates that ,

The second inequality of (12) in Lemma 2 leads to as taking . Hence,

Notably, we shall have if ; however, we restrict the condition as , for simplicity, and have

This proves the inequality (13). □

For the sake of discussion, let us define some symbols. For a regular triangle subdivision of , represents the set of all vertices divided, represents all edges contained in , and contains the inner edges of . We set , , and . denotes the diameter of any set B. Let E be the shared edge of K and , i.e., , and represent the outward normal vector of E in K. We define the jump across the edge by

and ; we set for convenience.

The a posteriori estimates of the space can be derived from the right end of Theorem 1 by quite standard arguments [26] with interpolation and the bubble functions.

Lemma 3

(The estimation of interpolation [39]). Let be the interpolation operator for a regular partition, then, ,

where and S represent the edge E or element K. Constants , ..., only depend on the reference element and regular partition.

Let () be the area coordinates on the reference element K. We define the bubble functions and as follows:

where j and k are the indices of E’s two vertexes associated with while l and m are that with , and . The space of vector bubble functions is then denoted by with . Here, and are spaces of linear polynomials on K and E, respectively, and is a continuation operator.

Lemma 4

(Bubble function space [40]). and , where and ,

where constants depend on the reference element and regular partition only.

Theorem 2.

There exists a constant independent of , and ϵ such that

where , and the oscillation term , with , and

Here, denotes the area of K.

Proof.

With Equation (5),

We denote with a interpolation and have . We denote by and the dual space of and the dual operator of , respectively. is the Banach space of continuous linear maps of in .

Then,

The two terms on the right-hand side (RHS) of the above inequality are considered one by one as shown below. The first term is

In the second term of the RHS of (28),

Therefore, according to the above analysis and Equation (26),

□

Theorem 3.

If and satisfy the conditions in Theorem 1, there exists a constant independent of , and ϵ such that

where .

Proof.

Equation (8) gives for

Then, we have

According to Theorem 1,

Therefore, with Theorem 2, we have

with independent of , and . □

Remark 1.

For the oscillation term ϵ in inequality (30), when is piecewise , [41]. Specially, and when is a piecewise constant function on .

3.2. Upper Bounds of the Estimators

In this subsection, we prove the upper bounds of the space and time estimators, respectively. We now begin with the space estimator. The special bubble function [42] is defined before discussions.

Given any number , we denote the transformation , which meets

where . , we set invertible affine map [43] on reference element that

Set for the edge bubble function on , ,

and we call the special edge bubble function on . We set on for simplicity defining the function on with as follows:

and .

Lemma 5

(Special bubble function [42]). T is the element and E is one of its edge, then ,

where constants and only depend on the reference element and regular partition.

The weak problem of the system (3) at can be represented so as to find such that

Corresponding to problem (31), we obtain the following linear problem at by the G derivative: , to find , such that

where satisfies Equation (31) and

To build the relationship between and , we discuss the relationship between and at first.

Theorem 4.

Denoting . If , , , and , we have

where constant is independent of , and ϵ.

Proof.

The definition of the G derivative [38] indicates that, ,

Then, with inequality (33) and (16) choosing and , respectively, we have

where the second inequality is provided by using the first inequality in (12).

Consequently,

and independent of , , and . □

Theorem 5.

If and satisfy the conditions in Theorem 4, there exist constants independent of , , and ϵ such that

and

where , and .

Proof.

For defined in Equation (27), the relationship between and each term of is considered. Then, we have

where inequality (18) is applied for having the first inequality, and inequalities (17) and (20) are used for obtaining the second inequality.

Let , then

where the last inequality is obtained by inequalities (17) and (22).

With the left side of inequality (24) and , we have

On the side of , we have

where represents the maximal diameter of K in . Inequalities (19) and (23) are applied for showing the first and second inequalities, respectively. Inequality (21) is used to obtain the fourth inequality.

Denote , with the constant to be determined later. Based on the Green formulation and Lemma 5, then

Choosing , it reads

In summary,

and

For the first term on the right side of inequalities (39) and (40),

with Theorem 4 and

we have

Analogously, we can obtain inequality (36). □

Remark 2.

According to Theorem 3, Remark 1, and the numerical integration formula, at a fixed time , we can have the conclusion that

and

Recalling that robust means that the estimators yield upper and lower bounds on the error such that the ratio of the upper and lower bounds is bounded from below and from above by constants which depend neither on any mesh size nor on the perturbation parameter [42], and combined with the conclusion in Theorem 5, we verify that our work ensures the robustness for the a posteriori estimates of space under the improved energy norm.

To finish the proof of the upper bound, we have to estimate the term . In our a posteriori error estimates, for fixed time-step , we control the error between and . A mature analytical method is presented in [17], and here, we give a brief proof.

Theorem 6.

Each defined in Lemma 2 satisfies the following upper bound

Proof.

Equation (8) gives for ,

Then, we have

Furthermore, we obtain the bound

We integrate between and , and obtain

and thus, Theorem 5 is proved. □

4. Adaptive Algorithm and Numerical Experiments

In this section, we provide one possible implementation of the adaptive algorithm for PNP equations and give numerical experiments to validate the algorithm.

Considering the algorithm for time-step size control, the time discretization error is equally distributed to each time interval . Let be the total tolerance to the time discretization, then

With , a natural way to achieve inequality (41) is to adjust the time step size such that the following relations are satisfied

Let be the tolerance allowed for the space discretization. The usual stopping criterion for the mesh adaption is to satisfy

With , the relation in inequality (43) converts into

A natural way to achieve adaptive algorithm for time-dependent PNP equations is to adjust the time step size and , satisfying Equations (42) and (44). The method also appears in [12].

At each time step, the well-known cycle of the adaptive method for the space is “SOLVE →ESTIMATE→MARK→ REFINE”. The difficulty in solving time-dependent PNP equations lies in how to deal with the nonlinear term. We choose Picard’s linearization in [44] for the nonlinear term in system (3). It is important to mention that the equations with lead to systems that are potentially convection dominated, which leads to potential algorithmic difficulties in solving the system. Here, we use the edge-averaged finite element (EAFE) scheme in [45]. The method has been discussed in [33,46] for PNP equations. Algorithm 1 provides one possible implementation of time and space adaptivity for the time-dependent PNP equations at each time step referred to in [10,12,31].

Some numerical experiments are presented to verify the viability and efficiency of the a posteriori estimations. For these experiments, we use the following model to verify our theory.

To find such that

where and .

Compared with the previous system (3), the system (45) has the right end term and the boundary condition becomes a homogeneous Dirichlet condition. Because the homogeneous Dirichlet condition is a special case of the boundary condition (2), the analysis in our previous sections can be adapted to the system (45). According to the analysis of Theorem 2, the forms of and change as

where and

The first experiment presented here is designed to verify the adaptive effect in the time step adjustment due to the time singular point, and the time and space parallel adaptive adjustment with the flow structure changing caused by time. The second numerical experiment verifies the problem with the boundary layer effect. All experiments are in two dimensions, and simulations are performed with the software MATLAB 7.0 based on an integrated finite element method package iFEM.

| Algorithm 1 Time and space adaptive algorithm. |

|

Example 1

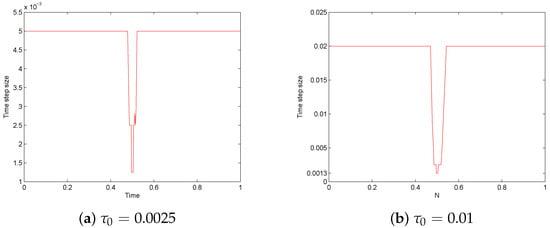

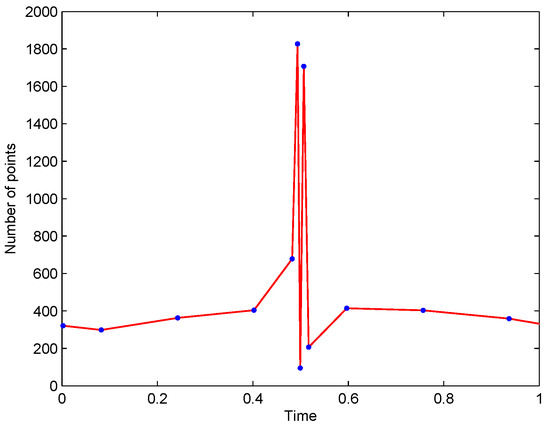

For Algorithm 1, we choose in Example 1 and give some specific cases of time-step adaptation. Firstly, we constrain the time step to be extended only once when the time step is too small at each time step. Figure 1 shows the number of nodes and the time step size at each time step n with , respectively, when and . We note that the time step size drops in a small time interval around and is constant in the rest of the interval. It is not a surprise, as changes exponentially from to 0 and then from 0 to around . The ratio of the maximum time step size to the minimum is when . That means the efficiency of the adaptation can increase by an order of magnitude. Then, Figure 2 shows the number of nodes of at each time step when , , and without the constrains on the number of time extensions.

Figure 1.

The time step size at each time step n with different initial step size when and . The total numbers of the calculation time are and , respectively.

Figure 2.

The number of nodes of at each time step when , , and initial time step .

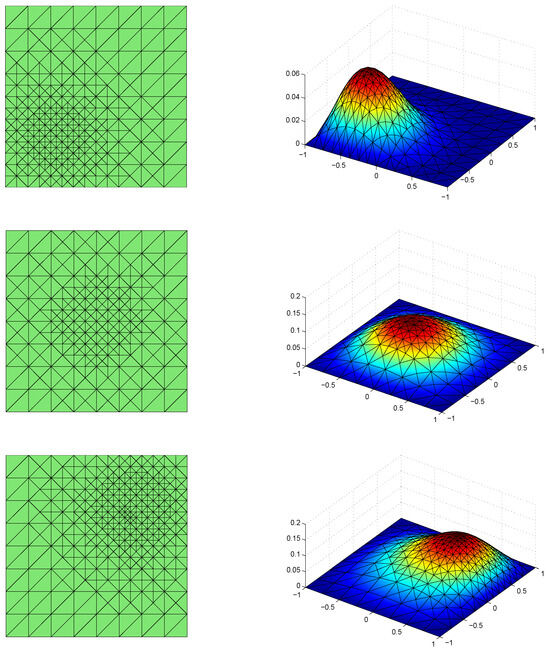

In Figure 3, the surface plots of discrete solutions and the corresponding meshes at are displayed. It clearly indicates the ability of Algorithm 1 to capture the singularity of the solutions by locally refining and coarsening the meshes, and to realize the adaptive adjustments of time steps and mesh sizes simultaneously.

Figure 3.

Surface plots of discrete solutions (right) and the corresponding meshes (left) at (from top to bottom). The numbers of nodes of the meshes are for , respectively.

In summary, Figure 1 shows the adaptive effect in time step adjustment due to the time singular point. The time and space parallel adaptive adjustments with the flow structure are verified in Figure 2 and Figure 3. The numerical results mean Algorithm 1 can realize adaptive adjustments of the time steps and mesh sizes simultaneously.

Example 2

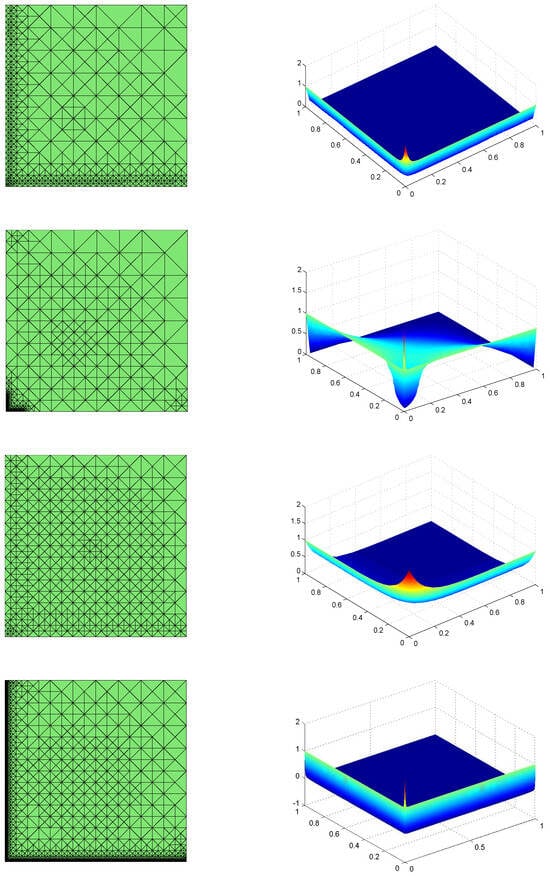

([31]). Considering the boundary layer changing with time, we take

to be the exact solution to system (45) on . Correspondingly, the right-hand side functions , , and are determined by the above exact solution.

Here, we focus on the adaptivity in the space and choose uniform time refined with in Example 2, and Figure 4 shows that the boundary layer is perfectly captured, and the mesh adaptation is realized. The first two lines in Figure 4 show the surface plots of discrete solutions (right) and the corresponding meshes (left) at (from top to bottom) for . As time goes on, we observe more grids near the original point than other parts of the boundary when degrees of freedom are close to each other. Furthermore, in order to observe the boundary layer with the decrease of at the same time, we give the surface plots of discrete solutions (top right) and the corresponding meshes (top left) at for in the third line of Figure 4. The adaptivity can be demonstrated as more condensed grids near the boundaries as decreases. For the case with , the mesh refinements are well observed in the boundary, i.e., and , as the number of meshes is increased to be large enough. The corresponding surface plots of discrete solutions (bottom right) and the corresponding meshes (bottom left) are shown in the last line of Figure 4.

Figure 4.

For the first two lines, surface plots of discrete solutions (right) and the corresponding meshes (left) at t = 0.16, 0.96 (from top to bottom) for . The numbers of the mesh nodes are 579, 568 for t = 0.16, 0.96, respectively. For the last two lines, the surface plots of discrete solutions (right) and the corresponding meshes (left) at t = 0.96 for (from top to bottom). The numbers of the meshes nodes are 573, 11,398 for , respectively.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, the a posteriori error estimation is adopted for the adaptive analysis of time-dependent PNP equations, where the nonlinearity and strong coupling are focused. During the theoretical study of the a posteriori error estimation, we establish two types of computable error estimators which bound the time and space error, respectively. The estimates for the upper bounds of the time and space estimator are derived, respectively, so as to demonstrate the efficiency and reliability of the error estimator. In particular, the a posterior error estimate in space is robust under the improved energy norm. The adaptive algorithm is constructed based on the estimates and realizes the parallel adaptivity of time steps and mesh refinements. Numerical experiments show the phenomenon of adaptive time step and mesh size adjustments due to the time singular point and the flow structure with time, and successfully capture boundary layers arbitrarily changing with the flow of time. Although our work can solve the boundary layer problem well, it is still valuable to find a method with lower computational complexity. In the future, we plan to explore various a posterior error estimation methods and seek more effective methods to solve such problems through comparative analysis. We will use different control algorithms to achieve adaptive time steps, and extend the theoretical analysis to anisotropic meshes, which are more efficient for real physical problems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.F. and T.H.; methodology, K.F. and T.H.; software, K.F. and T.H.; validation, K.F. and T.H.; formal analysis, K.F. and T.H.; investigation, K.F. and T.H.; resources, T.H.; data curation, K.F. and T.H.; writing—original draft preparation, K.F. and T.H.; writing—review and editing, K.F. and T.H.; project administration, T.H.; funding acquisition, T.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12301467), and Applied Basic Research Project of Changzhou Science and Technology Bureau (No. CJ20235027).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Proof of Solution Existence and Uniqueness

To find , , such that ,

where satisfies Equation (6)

Proof.

Solution Uniqueness:

Let be fixed. Then, there exists a unique such that

(This follows from the standard results on elliptic equations, e.g., see [43])

We define by ,

where .

For the initial value problem,

where . It is uniquely solvable (this follows from the standard results on evolution equations; see [36]). The mapping from into itself assigning to and will be denoted by Q. We shall prove that Q has a fixed point. From (A3), it follows by means of the test function ,

then,

and ,

and thus,

When choosing , we have

This proves that , if

The preceding estimates along with (A3) show that

Consequently, Q maps a bounded set in into a bounded set in which is compactly embedded in .

Using similar arguments to those used before,

where represents the difference between any two elements in B, and .

Therefore, Schauder’s Fixed Point Theorem yields the existence of a fixed point of Q.

Solution Uniqueness:

Assuming both and satisfy (A1), we prove and as following, and thus . We define , then have

where are related to and .

When ,

Gronwall’s Lemma completes the proof (when then ). □

References

- Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, M. Studies on Ionic flows via Poisson–Nernst–Planck systems with Bikerman’s local Hard-Sphere potentials under relaxed neutral boundary conditions. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Lu, B. A class of finite element methods with averaging techniques for solving the three-dimensional drift-diffusion model in semiconductor device simulations. J. Comput. Phys. 2022, 458, 111086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasielec, J.J. Electrodiffusion phenomena in neuroscience and the Nernst–Planck–Poisson equations. Electrochem 2021, 2, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewski, H.; Groger, K. On the basic equations for carrier transport in semiconductors. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1986, 113, 12–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerome, J.W. Consistency of semiconductor modeling: An existence/stability analysis for the stationary van Roosbroeck system. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 1985, 45, 565–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biler, P.; Hebisch, W.; Nadzieja, T. The Debye system: Existence and large time behavior of solutions. Nonlinear Anal. Theory Methods Appl. 1994, 23, 1189–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerome, J.W.; Kerkhoven, T. A finite element approximation theory for the drift diffusion semiconductor model. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1991, 28, 403–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.R.; Murthy, J.Y. A multigrid method for the Poisson Nernst Planck equations. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2009, 52, 4031–4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Sun, P. A linearized local conservative mixed finite element method for Poisson Nernst Planck equations. J. Sci. Comput. 2018, 77, 793–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picasso, M. Adaptive finite elements for a linear parabolic problem. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 1998, 167, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verfürth, R. A posteriori error estimates for finite element discretizations of the heat equation. Calcolo 2003, 40, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Feng, J. An adaptive finite element algorithm with reliable and efficient error control for linear parabolic problems. Math. Comput. 2004, 73, 1167–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chami, F.E.; Sayah, T. A posteriori error estimators for the fully discrete time dependent Stokes problem with some different boundary conditions. Calcolo 2010, 47, 169–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bergam, A.; Bernardi, C.; Mghazli, Z. A posteriori analysis of the finite element discretization of some parabolic equations. Math. Comput. 2005, 74, 1117–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, C.; Verfürth, R. A posteriori error analysis of the fully discretized time-dependent Stokes equations. ESIAM Math. Model. Numer. Anal. 2004, 38, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, C.; Sayah, T. A posteriori error analysis of the time dependent Stokes equations with mixed boundary conditions. IMA J. Numer. Anal. 2014, 35, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, C.; Sayah, T. A posteriori error analysis of the time dependent Navier-Stokes equations with mixed boundary conditions. Sema J. 2015, 69, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lakkis, O.; Makridakis, C. Elliptic reconstruction and a posteriori error estimates for fully discrete linear parabolic problems. Math. Comput. 2006, 75, 1627–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Makridakis, C.; Nochetto, R.H. Elliptic reconstruction and a posteriori error estimates for parabolic problems. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2003, 41, 1585–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akrivis, G.; Makridakis, C.; Nochetto, R.H. A posteriori error estimates for the Crank-Nicolson method for parabolic equations. Math. Comput. 2006, 75, 511–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akrivis, G.; Makridakis, C.; Nochetto, R.H. Optimal order a posteriori error estimates for a class of Runge-Kutta and Galerkin methods. Numer. Math. 2009, 114, 133–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bnsch, E.; Karakatsani, F.; Makridakis, C.G. A posteriori error estimates for fully discrete schemes for the time dependent Stokes problem. Calcolo 2018, 55, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, P.K. A posteriori error estimation with finite element semi- and fully discrete methods for nonlinear parabolic equations in one space dimension. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1994, 31, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, K.; Johnson, C. Adaptive finite element methods for parabolic problems IV: Nonlinear problems. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1995, 32, 1729–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verfürth, R. A posteriori error estimates for nonlinear problems: Lr (O, T; W1,ρ (Ω) -error estimates for finite element discretizations of parabolic equations. Math. Comput. 1998, 67, 1335–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Verfürth, R. A posteriori error estimates for nonlinear problems: Finite element discretizations of elliptic equations. Math. Comput. 1994, 62, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babuška, I.; Feistauer, M.; Śolin, P. On one approach to a posteriori error estimates for evolution problems solved by the method of lines. Numer. Math. 2001, 89, 225–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pousin, J.; Rappaz, J. Consistency, stability, a priori and a posteriori errors for Petrov-Galerkin methods applied to nonlinear problems. Numer. Math. 1994, 69, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, M.; Babuška, I. Reliable and robust a posteriori error estimation for singularly perturbed reaction-diffusion problems. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1999, 36, 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, S.; Zhao, J. Guaranteed a posteriori error estimates for nonconforming finite element approximations to a singularly perturbed reaction-diffusion problem. Appl. Numer. Math. 2015, 94, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, T.; Ma, M.; Xu, X. Adaptive finite element approximation for steady-state Poisson-Nernst-Planck equations. Adv. Comput. Math. 2022, 48, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verfürth, R. Robust a posteriori error estimates for nonstationary convection-diffusion equations. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2005, 43, 1783–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metti, M.S.; Xu, J.; Liu, C. Energetically stable discretizations for charge transport and electrokinetic models. J. Comput. Phys. 2016, 306, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, S.C.; Scott, L.R. The Mathematical Theory of Finite Element Methods; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Prohl, A.; Schmuck, M. Convergent discretizations for the Nernst-Planck-Poisson system. Numer. Math. 2009, 111, 591–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L.C. Partial Differential Equations, 2nd ed.; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Verfürth, R. A posteriori error analysis of space-time finite element discretizations of the time-dependent Stokes equations. Calcolo 2010, 47, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidler, E. Nonlinear Functional Analysis and Its Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ciarlet, P. The Finite Element Method for Elliptic Problems; North-Holland Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, M.; Oden, J.T. A Posteriori Error Estimation in Finite Element Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, P.; Nochetto, R.H.; Siebert, K.G. Data oscillation and convergence of adaptive FEM. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2001, 38, 466–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verfürth, R. Robust a posteriori error estimators for a singularly perturbed reaction-diffusion equation. Numer. Math. 1998, 78, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciarlet, P.G. Basic error estimates for elliptic problems. Handb. Numer. Anal. 1991, 2, 17–351. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Sun, P.; Zheng, B.; Lin, G. Error analysis of finite element method for Poisson Nernst Planck equations. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2016, 301, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zikatanov, L. A monotone finite element scheme for convection-diffusion equations. Math. Comput. 1999, 68, 1429–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousquet, A.; Hu, X.; Metti, M.S.; Xu, J. Newton solvers for drift-diffusion and electrokinetic equations. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2018, 40, B982–B1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubuka, I.; Vogelius, M. Feedback and adaptive finite element solution of one-dimensional boundary value problems. Numer. Math. 1984, 44, 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binev, P.; Dahmen, W.; Devore, R. Adaptive finite element methods with convergence rates. Numer. Math. 2004, 97, 219–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).