Abstract

Dupin cyclides are interesting algebraic surfaces used in geometric design and architecture to join canal surfaces smoothly and to construct model surfaces. Dupin cyclides are special cases of Darboux cyclides, which in turn are rather general surfaces in of degree 3 or 4. This article derives the algebraic conditions for the recognition of Dupin cyclides among the general implicit form of Darboux cyclides. We aim at practicable sets of algebraic equations on the coefficients of the implicit equation, each such set defining a complete intersection (of codimension 4) locally. Additionally, the article classifies all real surfaces and lower-dimensional degenerations defined by the implicit equation for Dupin cyclides.

MSC:

65D17; 14Q30

1. Introduction

Darboux cyclides are classical algebraic surfaces in that have promising applications in geometric design and architecture. Their implicit equation has the form

Here, are real coefficients. Remarkably, Darboux cyclides are covered by several families of circles [1,2,3]. Hence, they are natural candidates to model a surface composed of patches blended along circles. This task is still challenging for more general Darboux cyclides [4], but the special cases of Darboux cyclides called Dupin cyclides have definite applications already [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Conveniently, Dupin cyclides are canal surfaces whose curvature lines are circles or lines. They are useful to join pipes between canal surfaces [8] and to model surfaces smoothly blended along curvature lines [9,10,11,12]. Significantly, the set of Dupin cyclides is stable under the offsetting at a fixed distance along the surface normals [6,11,13]. The offset operation arises frequently in geometric design and manufacturing [2,6]. On that account, geometric modeling with Dupin cyclides simplifies the computation of offset surfaces. The contrast between Dupin and Darboux cyclides is illustrated in Figure 1. Darboux cyclides generally have six circles through each point on the surface [14,15], while Dupin cyclides have two principal circles as lines of curvature and two so-called Villarceau circles through each point; the principal circles represent pairs of coalescing circles of the general Darboux cyclide ([2], Theorem 18(v)).

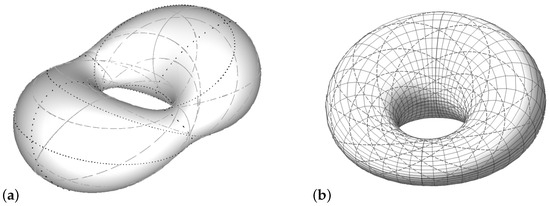

Figure 1.

(a) A smooth Darboux cyclide covered by six families of circles drawn in solid, dash, dot, dashdot, spacedot, or longdash. There are two examplar points with six circles through them near the donut hole. (b) A smooth Dupin cyclide covered by four families of circles; the solid circles are principal circles and the dashed circles are Villarceau circles (see Section 6.2).

It is evidently desirable to distinguish Dupin cyclides among general Darboux cyclides. The implied standard recognition procedures involve bringing the implicit equation (1) to a known canonical form by Möbius transformations [4,16], or discerning that a geometric characterization is satisfied [12,17,18]. To establish a more convenient recognition procedure, we compute the set of algebraic equations on the coefficients characterizing Dupin cyclides among the form (1). Our starting point is the following canonical forms of Dupin cyclides under the Euclidean transformations. A quartic Dupin cyclide can be presented by the implicit equation

after Euclidean translations and rotations ([6], pp. 223–224), ([19], Ch. IX). We broadly assume that , , , , thereby allowing cyclides without real points along other degenerate cases. All degenerate cases are described further in Section 6.3. A cubic Dupin cyclide can be brought to the form

with . This differs from the equation in ([7], p. 151) by a scaling of with a factor of 2. The Euclidean equivalence to these two forms replaces here the classical definition of Dupin cyclides by Möbius equivalence in to a torus, a cylinder, or a cone [18]. We give a generic explicit Möbius isomorphism between Dupin cyclides and toruses in Section 6.1.

It is straightforward to normalize the coefficients to zero (if ) by Euclidean translations, but further normalization by orthogonal or Möbius transformations is cumbersome. This article presents the computed set of necessary and (generically) sufficient algebraic conditions on so that Equation (1) defines a Dupin cyclide. The problem of recognizing Dupin cyclides from an implicit equation is a complementary question to the constructive classification of Dupin and Darboux cyclides by normal forms [4] or pentaspherical projection from [15]. We view the 14 coefficients in (1) as the homogeneous coordinates in the real projective space , which is identified as the space of Darboux cyclides. The Dupin cyclides are represented by the projective variety in defined by the found algebraic conditions. Some of the points on this variety represent degenerations of cyclides to reducible, non-reduced, or quadratic surfaces.

To organize the results, the cases of quartic and cubic cyclides are considered separately. The subvariety of representing quartic Dupin cyclides has in (1); it will be denoted by . The subvariety of representing cubic Dupin cyclides (i.e., with and ) will be denoted by . We are interested only in the real points on those varieties so that the coefficients in (1) are real. The next section states the main results of this article: the algebraic equations that characterize the two main subvarieties and . The results are proven in Section 3 (for quartic cyclides) and Section 4 (for cubic cyclides).

As summarized in Section 5.2, the co-dimension of the considered spaces of Dupin cyclides inside the respective projective spaces of Darboux cyclides equals 4. In particular, the variety has dimension 9. The main explicit result is presented in Theorem 1 by underscoring open subvarieties of those varieties that are complete intersections in a suitable ambient open subspace of . This way of presenting the results should be convenient for practical applications, we suggest. The results are applied in Section 6.2 to compute an important invariant of Dupin cyclides under the Möbius transformations. Additionally, Section 6 classifies the real surfaces defined by the equations for Dupin cyclides, including degenerations to a few or no real points.

2. The Main Results

To present the results in a more compact form, these abbreviations are used throughout the article:

These expressions are symmetric under the permutations of the variables or, equivalently, under the permutations of the indices . We will use several non-symmetric expressions, starting from

Let , , be the permutations of the coefficients in (1) which permute the indices or or , respectively. This allows us to express variations of non-symmetric expressions straightforwardly. In particular,

2.1. Recognition of Quartic Dupin Cyclides

In order to simplify the recognition of quartic Dupin cyclides among Darboux cyclides, we first assume in (1) without loss of generality. Thereby, the ambient space of Darboux cyclides is identified with the affine space rather than . Further, we can easily apply the shift

and eliminate the cubic term . Thus, the recognition problem simplifies to the consideration of cyclides of the form

One could further apply orthogonal or inversion transformations to bring the quartic equation to an even simpler canonical form with , but those transformations are cumbersome to calculate. The recognition of Dupin cyclides in the form (15) is therefore a pivotal practical problem. The ambient space of Darboux cyclides simplifies accordingly to a 10-dimensional affine space with the coordinates . We denote by the variety of Dupin cyclides there.

The variety is the orbit of under easy translations (14). The following theorem describes the equations for . The equations for are obtained by a straightforward modification of the coefficients in (15), as described in Section 5. Besides (11), we immediately use these polynomials:

Theorem 1.

The hypersurface in defined by (15) is a Dupin cyclide if and only if one of the following cases holds:

- (a)

- , , , , .

- (b)

- , , , , .

- (c)

- , , , , .

- (d)

- , , .

- (e)

- , , ,.

- (f)

- , , , .

Example 1.

A prototypical example of a Dupin cyclide is the torus with the minor radius r and the major radius R. It is defined by the equation

Our main theorem applies with and

Case (e) applies, as , and its last two equalities hold with and .

Remark 1.

The cases of Theorem 1 define a stratification of the variety into pieces that are complete intersections in , possibly of variable dimensions. This localization onto complete intersections is our deliberate strategy of presenting a practical procedure of recognizing Dupin cyclides. The aim is to check the minimal number of (rather cumbersome) equations for each particular cyclide. The co-dimension of in turns out to be 4; hence, this minimal number of equations equals 4.

Concretely, the parts (a)–(c) define three intersecting open subvarieties of as complete intersections on the Zariski open subsets , and of . Only four equations are checked in these cases, as the codimension equals 4. The cases (d)–(f) define subvarieties of of smaller dimensions inside the closed subset of . There, we have two reduced components (d), (e) of dimension 5, and the former is a complete intersection already. The latter component is further stratified into the cases and , leading to the concluding complete intersections (e), (f) of the codimension 5 or 6, respectively.

2.2. Recognition of Cubic Dupin Cyclides

The general cubic Darboux cyclides have an implicit equation of the form

The ambient space of Darboux cyclides is therefore considered as the real projective space , in which we describe . To formulate the result for the cubic cyclides, we define the rational expression

Theorem 2.

The co-dimension of equals 4, and the dimension equals 8 within the hyperplane . With , the coefficients to the cubic and quadratic parts can be chosen freely, and then there are unique values for so that (19) defines a Dupin cyclide. The analogous question for quartic cyclides is considered in Remark 5.

3. Quartic Dupin Cyclides

In this section, we prove Theorem 1 for the recognition of quartic Dupin cyclides of the form (15). The proof refers to Gröbner basis computations, which were carried out using computer algebra packages Maple and Singular. But we also present constructive ways of obtaining the presented equations from the initial ones. The initial equations are derived from the well-known canonical form (2) of quartic Dupin cyclides. We consider the variety as the orbit of this canonical form under the orthogonal transformations . Rather than introducing the orthogonal transformations explicitly and eliminating their parameters, we compare the invariants under for the general equation (15) and the canonical equation. This effective comparison is carried out in Section 3.2. The coefficients of the canonical form are eliminated in Section 3.3. Finally, Section 3.4 finds the complete intersection cases of Theorem 1 as expounded in Remark 1.

3.1. From the Canonical Form

We adopt the parametrized description of the quartic equation (2) for quartic Dupin cyclides to the implicit form like (15).

Lemma 1.

A quartic Dupin cyclide can be expressed, up to translations and orthogonal transformations in , in the form

with the relations

Proof.

The canonical form defines a variety of dimension , as we have five coefficients in (23) and two relations between them. The action adds 3 degrees of freedom, hence the dimension in has to equal 6.

Remark 2.

An inverse map is defined by

Each of these values can be multiplied by , as long as .

Remark 3.

The cases of Theorem 1 with are in the orbit of the canonical form (23) with . The splitting into the cases (d) and (e)–(f) is consistent with the expression . The canonical form for the case (d) has in (2), or , , in (23). The canonical form for the case (e) has either , , , or , , . The canonical form for the case (f) has, more particularly, , (or ), and .

3.2. Applying Orthogonal Transformations

The direct way to compute the -orbit of the canonical form (2) is to apply an arbitrary orthogonal matrix to the vector of the indeterminates. The coefficients would then be parametrized by the 14 variables—the 5 coefficients in (23), and the 9 entries of the matrix—restrained by two Equations (24) and (25) and the 6 orthonormality conditions between the rows on the matrix. The expected dimension of is thereby confirmed: . But the elimination of the parametrizing variables appears to be too cumbersome even using computer algebra systems such as Maple and Singular.

Instead of working with the nine variables of the orthogonal matrix, we identify the -invariants for Equations (15) and (23). The group acts on the quadratic and linear parts of these equations disjointly, making the identification of invariants and their relations easier. The further elimination of is carried out in the next section.

Lemma 2.

Proof.

An orthogonal transformation acts as follows:

- The highest degree term remains invariant.

- The quadratic forms and are related by the conjugation between their symmetric matrices

- The linear forms and are related by the same orthogonal transformation M acting on the corresponding vectors and . Their relation to the matrices in (36) will be preserved, and thus, must be an eigenvector of the first matrix with the eigenvalue . This gives the relations (31)–(33). In addition, the Euclidean norms of the two vectors will be equal, giving (34).

- The constant coefficients will be equal, giving (35).

□

3.3. Elimination of the Coefficients of the Canonical Form

Here we start using the abbreviations (4)–(10) and the algebraic language of ideals. Let us denote the polynomial ring

The variety of Dupin cyclides is defined by the ideal obtained by eliminating from Equations (24), (25) and (28)–(35). As an intermediate step, it is straightforward to eliminate and leave only as an auxiliary variable.

Lemma 3.

The hypersurface (15) is a Dupin cyclide if and only if there exists such that these polynomials vanish:

Proof.

Here is an explicit reversible transformation between the equations of Lemmas 2 and 3. Equations (31)–(33) do not contain the variables we eliminate, , so they are copied as . The other equations are symmetric in . Using (28), (29), Equation (30) becomes with

This is the characteristic polynomial of the first matrix in (36), of course. The elimination of from (24) and (25) gives

We expand this equation to , where

Equation (25) with eliminated becomes . Considering as polynomials in , we divide the two cubic by the quadratic . The division remainders

are linear in . Indeed, and

We modify to the somewhat simpler .

The elimination of from the six equations (38)–(43) is not complicated, as five of them are linear in .

Proposition 1.

The ideal specifying Dupin cyclides in (15) is generated by the following 12 polynomials:

Proof.

The 12 polynomials of this proposition can be derived explicitly from Lemma 3 as follows. Most straightforwardly, are obtained by eliminating from the pairs of polynomials in (31)–(33). The polynomial turns up as follows:

The polynomials , are obtained similarly. Further, , , are obtained by pairing with , or and eliminating . The polynomial is obtained by the combination

It is clear that is the resultant of and with respect to . The polynomial is the resultant of and with respect to . Its compact expression is obtained by translating so that

and by computing the resultant as the determinant of the Sylvester matrix

Compared with Proposition 1, our main Theorem 1 specifies pieces of that are complete intersections in and cover the whole . This is explained in Remark 1. We wrote Maple routines for deciding whether a given implicit equation (1) defines a Dupin cyclide using either Theorem 1 or Proposition 1. When we tried to recognize a Dupin cyclide with five parameters, the routine that uses Theorem 1 recognized correctly in a few minutes, while the other routine took unreasonably longer.

3.4. Proof of Theorem 1

We find convenient, complete intersection pieces of by investigating the syzygies between the 12 generators of in Proposition 1. The simplest and most frequent factors of the syzygies found suggest the localizations in where requires fewer defining equations. The localization at those factors shrinks the set of generators of . In particular, we find that the localizations at (or , or ) give complete intersections immediately, leading to the cases (a)–(c) of Theorem 1. The subvariety turns out to be reducible. One component is already a complete intersection, giving the case (d). The other component is additionally stratified to complete intersections by considering whether .

Here are some simplest syzygies between the 12 generators in Proposition 1:

Assume that . From the firs thre syzygies, we see that , , and imply , , and . Similarly, we have the syzygy

and the -symmetric syzygy with . Therefore, if we use , then we have , . There are similar syzygies that express , , and in terms of -multiples of lower degree generators as well. Therefore, we obtain the case (a). By symmetry between , and , the specialization at gives us the case (b) and the specialization at gives us the case (c).

Let us consider now the degeneration . Let denote the polynomial ring , and let denote the specialization map . Note that the polynomials vanish in and the image ideal is generated by and . The product belongs to the ideal since

If , the ideal is generated by and . The option (d) then follows. Assume that . One can check that the ideal in is generated by , , , , where

There are two syzygies between them:

So the localization with gives a complete intersection generated by and , giving us the option (e). If , then we reduce to . After the elimination of with

we obtain an ideal generated by one element. We recognize such element compactly as or , and conclude the last option (f). It is left to track the case . We have again the syzygy

So we have the ideal inclusion . This case is therefore subsumed by (d).

4. Cubic Dupin Cyclides

Here, we prove Theorem 2, which characterizes the cubic (also called parabolic [17]) Dupin cyclides in the space of cubic Darboux cyclides (1) with . We compute the ideal defining as the orbit of a canonical form (3) of cubic Dupin cyclides under orthogonal transformations and translations. The -orbit of (3) is computed in Section 4.1, following the same strategy as in Section 3.2. Theorem 2 is proved in Section 4.2 after applying general translations in .

4.1. Applying Orthogonal Transformations

Applying an orthogonal transformation to our initial canonical form (3) gives us an intermediate form

of cubic Dupin cyclides. To define the set of generating relations between the coefficients here, let us define the polynomials:

Recall (4) that we denote .

Lemma 4.

Proof.

As in the proof of Lemma 2, we consider the action in each homogeneous part. Clearly, . The cubic and linear parts are proportional:

We obtain the following equations from a comparison of the quadratic parts and the eigenvector role of :

This system is similar to (28)–(33). The computation and comparison of Gröbner bases with respect to the same ordering shows that the elimination of p, q gives the ideal generated by the polynomials (66). □

Constructively, the equations , , are obtained by eliminating in (68) and (71)–(73). From (69), we obtain . The equations for then follow from (67). The proportionality in (67) gives the simple equations , , . A Gröbner basis with respect to a total degree ordering shows a few more vanishing polynomials of degree 2: , , , and the -variants.

4.2. Proof of Theorem 2

The general form (19) of cubic Darboux cyclides is obtained by applying an arbitrary shift

to the form (63), up to the multiplication of (19) by a scalar. We still assume in the computations and then homogenize the expressions by inserting the powers of to match the degrees of monomials. The shift (74) leads to these identification relations between the coefficients of (19) and (63):

The expressions for are obtained by the symmetries . Up to the homogenization, the space is defined by the ideal generated by these relations and the polynomials of Lemma 4. The elimination of the coefficients is straightforward. The accordingly modified equations , , are linear in with the discriminant . We solve in the non-homogeneous form (i.e., keeping ):

and the respective , modifications for expressions for . Now we can express using (78) and , , using the last three equations in (66).

5. The Whole Space of Dupin Cyclides

It is useful to compute the projective closure of the variety of quartic Dupin cyclides. If this closure contains the variety of cubic Dupin cyclides as a component at , it is natural to define the whole space of Dupin cyclides as this Zariski closure of in . In Section 5.1, we indeed conclude that is contained in the closure. As it turns out, the infinite limit includes also reducible components with . We discard the components with complex (rather than all real) points , and describe the quadratic limit surfaces in Remark 4. The geometric characteristics such as the dimension, the degree, and the Hilbert series of , , and are presented in Section 5.2.

5.1. Cubic Cyclides as Limits of Quartic Cyclides

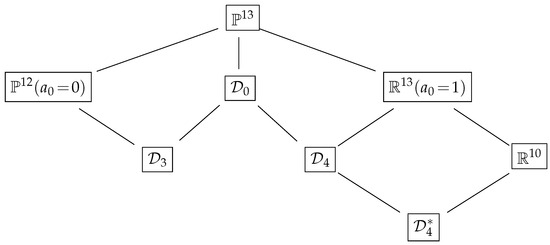

An alternative way to obtain the variety of cubic Dupin cyclides is to consider the projective limit of the variety of quartic cyclides. The latter variety is the restriction of the whole space of Dupin cyclides. This projective variety is defined by homogenizing the vanishing polynomials for with . Taking in gives a limiting variety that we identify with after throwing out complex components. The general picture of the introduced varieties of Dupin cyclides and the ambient spaces is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The inclusion diagram for the varieties of Dupin cyclides embedded in the spaces of Darboux cyclides.

The ideal in of the variety is obtained from our main results on by employing the normalizing shift (14). This shift transforms the general equation (1) for Darboux cyclides to

Comparing the coefficients here with those in (15), we modify the equations for the variety in Proposition 1 or Theorem 1, and obtain the defining equations for the space .

Moving towards in Figure 2, the homogenized ideal for is specified using the following standard result.

Proposition 2.

Let I be an ideal of the polynomial ring over a field k, and let be a Gröbner basis for I with respect to a graded monomial ordering in . Denote by the homogenization of a polynomial with respect to the variable . Then, is a Gröbner basis for the homogenized ideal .

Proof.

This is Theorem 4 in ([20], §8.4). □

We used Singular computations with respect to the total degree monomial ordering ([20], p. 52). The computed that the Gröbner basis for has 530 elements; the computation took about an hour on Singular. After the homogenization with and setting , we obtain a reducible variety, where some components (possibly one) are restricted by . We ignore these components by additionally assuming . Then, the Gröbner basis with respect to has 321 elements. The elimination of leads to the expressions of Theorem 2 with , without any relation between the other coefficients of (19). This completes the alternative way of obtaining the ideal for .

Remark 4.

It is interesting to see what quadratic surfaces with in (1) are contained in the variety as Dupin cyclides. After the substitution in the Gröbner basis with 530 elements, we obtain a reducible variety with two components of codimension 2 in (over ). One component is defined by the vanishing of two polynomials: the discriminant of the characteristic polynomial of the matrix P in (36), and the determinant of this extended matrix:

The discriminant equals this sum of squares:

where

The real points of this component are therefore defined by the ideal generated by the three cubic polynomials . This ideal defines a variety of co-dimension 2. This variety is intersected with the degree four hypersurface (which prescribes a singularity on the quadratic surface).

The second component restricts only the coefficients and coincides with . Hence, it subsumes the real points of the first component. The variety specifies the quadratic part of (1) to be in the -orbit of . The projective dimension of this orbit is 3 (rather than ) because the rotations around the z-axis preserve . Based on the identification with , the rotational quadratic surfaces (and the paraboloids like ) can be considered as Dupin cyclides.

Remark 5.

We have seen from Theorem 2 that a cubic Dupin cyclide is determined uniquely from the coefficients to the cubic and quadratic monomials in (19). For quartic Dupin cyclides (1) with , the projection to the coefficients is generically a 6:1 map. It is sufficient to see this 6:1 correspondence for the canonical form (23). With fixed , there are these six possibilities for the linear part: , and , with satisfying (24) and (25). It can also be checked (by computing a Gröbner basis) that a monomial basis for in the ring has six elements.

5.2. Dimension, Degree, Hilbert Series

It is straightforward to compute the Hilbert series for the computed ideals using Singular or Maple. The Hilbert series for the projective variety is the rational function with

The dimension of is indeed , and the degree equals . There are linearly independent polynomials of the minimal degree 5.

The Hilbert series for the affine variety is

The dimension of is 6, and the degree equals 42.

The Hilbert series for projective variety is

The dimension of is , and the degree equals 46. Recall that describes the component of the subvariety of . The homogeneous version of the Gröbner basis for with respect to has 261 elements. It has linearly independent polynomials of the minimal degree 5.

The co-dimension of all considered spaces of Dupin cyclides inside the corresponding projective spaces of Darboux cyclides equals 4.

Remark 6.

Besides the usual grading, the equations of our varieties have a weighted degree that reflects their invariance under the scaling with . The weights of the variables are the following:

and , . The symmetries do not change the weighted degree. The 12 equations in Proposition 1 have these weighted degrees:

and , , .

6. Classification of Real Cases of Dupin Cyclides

The torus equation (18) is also defined over when or . Similarly, the canonical equation (2) is defined over if , or if exactly two of these numbers are on the imaginary line, . Then, we may obtain degenerations to surfaces with a few (if any) real points.

Section 6.3 classifies all degenerations of Dupin cyclides. For that purpose, Section 6.1 defines general Möbius isomorphisms between Dupin cyclides and toruses and follows the cases when they are defined over . Section 6.2 defines a Möbius invariant of Dupin cyclides. This invariant and a few semi-algebraic conditions classify the Dupin cyclides up to real Möbius transformations.

6.1. Möbius Isomorphisms of the Torus

Spherical inversions or Möbius transformations between Dupin cyclides and a general torus have been constructed geometrically ([18], Theorem 3.5) and computed ([21], §2.3). An explicit Möbius isomorphism that maps a canonical Dupin cyclide (2) to the torus equation (18) is given by

where , . This Möbius transformation is defined over if and only if and . If , the canonical equation (2) coincides already with the torus equation (18) with , . With , the minor and major radii of the torus are given by

We can further apply scaling by the factor

to the immediate torus equation if either all or all . The resulting torus equation has , . Otherwise, the scaling can be adjusted by the factor , and the radii become , .

On the other hand, the canonical equation (2) is symmetrical ([6], (1)–(2)) with respect to the simultaneous interchange , . This symmetry implies a Möbius equivalence to the torus with the minor radius (and the same major radius R) as well. Up to scaling, this Möbius equivalence is symmetric to (86):

Both Möbius isomorphisms are defined over if and is between and on the real line. This means that because (87) implies

A composition of the two Möbius isomorphisms relates two toruses with the minor radii r and , when . This transformation is obtained explicitly by applying (89) with , , . After additional scaling of by , we obtain the Möbius transformation

that brings torus (18) to the torus

When , this Möbius duality is not defined over . If , then (18) defines a singular spindle torus ([17], p. 288), and the surface (92) has no real points. If , then (18) defines a singular horn torus, while (92) defines a circle.

6.2. The Toroidic Invariant for

Any torus (18) has two clear families of circles on it, namely on the vertical planes or horizontal planes . These circles are the principal curvature lines on the torus and are known as principal circles. Less known are two families of Villarceau circles [22,23] on the bitangent planes with on smooth toruses with . The angles , between principal and Villarceau circles depend only on the families of the involved circles. The sine (or the complementary cosine) of equals [23] the quotient . The duality (91) of toruses with the minor radii r and underscores constancy of the angle pair , under the (conformal!) Möbius transformations. Krasauskas showed us that the numbers and are equal to the two possible cross-ratios within the quaternionic representation [11] of Dupin cyclides.

The symmetry between and leads to this invariant under the Möbius transformations:

We define the invariant for general Dupin cyclides by the Möbius equivalence. The maximal value gives the “most round” cyclides (with ) that optimize the Willmore energy [24]

for the smooth real surfaces S with the torus topology. The integrand is the mean curvature H squared, and is the infinitesimal area element. The Willmore energy is conformally invariant, and it equals ([25], p. 275)

for a smooth torus (18). The duality breaks down for , as Möbius transformation (91) is then not defined over . The singular-horn torus (with ) is paired to the degeneration to a circle (), and the spindle toruses (with ) are paired with algebraic surfaces with no real points ().

We apply our results to compute the invariant for all Dupin cyclides. In the case of a canonical quartic cyclide (23), we choose Möbius equivalence (86) with a torus and obtain

due to (90) and (27). Then,

To obtain expressions of for the general quartic cyclide (15), we first eliminate as in Lemma 3. The result is

After the elimination of , we generically obtain

These expressions were obtained after heavy Gröbner basis computations with the new variable (or rather, its numerator and denominator separately) and the superfluous . They can be checked by reducing (to 0) the numerator of the difference to (99) in the Gröbner basis in for Lemma 3.

To obtain an expression of for the cubic cyclide (3), we apply the procedure at the beginning of this section: transform the variables according to the shift (14) and the form (1), homogenize with , and set . Here is a relatively compact rational expression of the lowest weighted degree obtained after heavy computations:

with , and

The variables could be eliminated in (102) using Lemma 2, but the obtained rational expression of degree 6 (after using ) is much larger.

6.3. Classification of Degenerate Dupin Cyclides

The cubic Dupin cyclides (3) always have real points and are easy to classify, starting from ([7], p. 151), ([17], p. 288):

- Smooth cyclides when ;

- Spindle cyclides when , ;

- Horn cyclides when , ;

- Reducible surface (a sphere and a tangent plane) when ;

- Reducible surface (a plane and a point on it) when .

Degeneration to quadratic surfaces is explained in Remark 4.

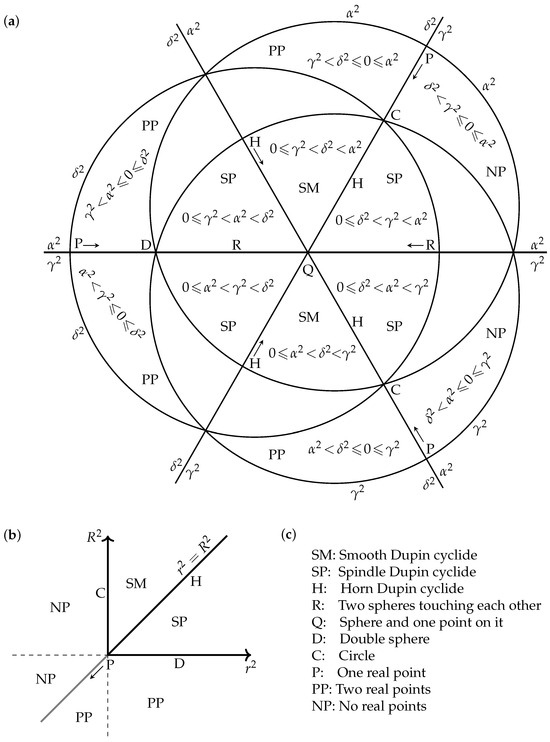

The full classification of the real points defined by the quartic canonical equation (2) depends on the order of on the real line, as we demonstrate briefly. The classification is depicted in Figure 3a. The border conditions , , are depicted by three intersecting circles (marked on the outer side by ). Their inside disks represent positive values of , respectively, while the negative values are represented by the outer sides of the circles. The conditions are represented by the three lines intersecting at the center. Their markings near the edge of the picture (say, and ) indicate which of the values ( or ) is larger on either side of the line. Most triangular regions are marked by a sequence of inequalities between ; these admissible regions represent the cases when the canonical equation is defined over . The six asymptotic outside regions represent the cases when all three are negative; they are not admissible. The admissible regions, several edges, and vertices are labeled by abbreviations for various types of Dupin cyclides. The labels are not repeated when the type does not change when passing from a triangular region to its edge or vertex. These coincidences are represented by the non-strict inequalities between 0 and . When a distinct edge and its vertex have the same type, the type is indicated near the vertex, and an arrow is added to the direction of that edge. The values of can be considered as constant along the radial directions from the center Q, with the optimal in the vertical directions, on the horizontal line , and along the other two drawn lines; see (97). The trivial case is not represented in Figure 3a, though it is represented by the origin point in Figure 3b.

This classification can be proved from the easier classification of torus equations (18) in Figure 3b, and by considering which of the two Möbius transformations (86) and (89) are defined over . The case of “toruses” with no real points can be seen from this alternative form of (18):

The cases of toruses lie on the circles and of Figure 3a. The Möbius equivalence (86) is defined over if and is either larger or smaller than both . It preserves and maps the applicable triangular regions onto the segments of the circle representing toruses. The adjacency of the corresponding triangular regions and segments cannot hold for the two lower-right regions SM, SP with ; these are the cases when the scaling by (88) has to be adjusted by . Similarly, (89) is defined over if and is either larger or smaller than both . This covers all cases except the line and the two leftmost triangular regions. When , the canonical equation (2) factorizes and defines (generically) two spheres with the centers at and touching at the point . If, then, , only the touching point is real; the other few deeper degenerations are straightforward. For the leftmost triangular region with , the canonical equation can be rearranged to

see ([19], p. 325). All three terms are positive for that region, and the Dupin surface then consists of two points on the line , . Similarly, two points are obtained for the other leftmost region .

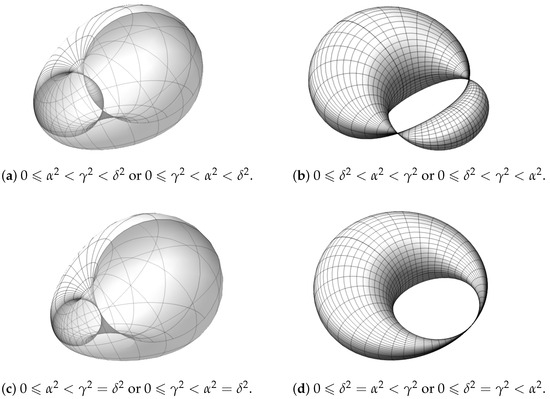

The SM-regions for smooth Dupin cyclides separate pairs of SP-regions for spindle cyclides. Accordingly, there are two types of spindle cyclides in ; see Figure 4(a,b) or ([18], Fig. 3), ([21], Fig. 2.23). Spindle cyclides have two real singular points that either (a) delimit a lemon-shaped volume inside an apple-shaped body [26] confined by the self-intersecting surface, or (b) delimit two horn-shaped volumes. These two types of spindle cyclides are related by a spherical inversion centered inside the apple or horn parts. There are two types of horn cyclides as well; see Figure 4(c,d). They are the limiting cases of the two types of spindles cyclides, with one real singular point.

Figure 4.

(a,b) Spindle Dupin cyclides. (c,d) Horn Dupin cyclides.

The conditions on can be directly translated to the conditions on the coefficients in (23) using (27). The quadratic covering (24) of the -plane confirms the topology of four admissible regions connected at six corners. The translated classification is as follows:

- Smooth Dupin cyclides, when . Then and , .

- Spindle cyclides, when either (a) . or (b) , , with reference to Figure 4. In either case, , .

- Horn cyclides, when either (c) , , or (d) , . In either case, .

- The reducible surface of two touching spheres, when (then ) or . In either case, .

- Reducible surface of a sphere and a point on it, when . Then, is undefined.

- Double sphere, when . Then .

- A circle, when , . Then , .

- Two real points, when either (then , , ) or , (then , ).

- One real point, when either , (then ), or (then ), or .

- No real points, when . Then , .

Further translation in terms of the coefficients in (15) is cumbersome. Some basic distinctions are determined by the -invariant, represented by the directions from the central point Q in Figure 3a. The circular boundaries , , do not represent semi-algebraic conditions (except at the vertices C, D), as they separate the cases of whether the surface equations (2) and eventually (15), (1) are defined over or not. To distinguish the six regions around Q and the six outer regions, it is tempting to invent a polynomial that vanishes at the vertices C and D and has different signs for the inner and outer regions. But the polynomials in (or the other coefficients) that vanish at C and D also vanish at the opposite meeting corners or the PP and NP regions. The practical suggestion to distinguish the cases is to compute using one of the equations (linear in ) of Lemma 3, and then compute as the roots of the quadratic polynomial . After eliminating , we obtain the equation

with the roots , . If preferable, one can reduce the degree in in the last equation using (43).

7. Conclusions

Dupin cyclides are algebraic surfaces in the 3-dimensional Euclidean space, of degree four or three, that have applications in geometric design and architecture. The larger class of Darboux cyclides is promising for these applications as well, yet recognising Dupin cyclides from the implicit equation (1) will remain an important practical problem. Considering the free coefficients in (1) as projective coordinates, we identify the space of Darboux cyclides as the projective space . The points in that correspond to Dupin cyclides form an algebraic variety of codimension 4. It can be computed as the orbit of canonical equations (2) and (3) under Euclidean transformations in . This article aims at establishing practical sets of algebraic equations for or its representative subvarieties. Additionally, Section 6.3 classifies the real types of Dupin cyclides and their degenerations.

The affine chart represents quartic Darboux cyclides. The affine variety of quartic Dupin cyclides can be simplified by affine translations (14) to the representative variety of Section 3; see Figure 2. The equations for are formulated in Proposition 1 and Theorem 1. The latter theorem is more practical as it specifies the minimal number (the codimension 4) of equations to check, depending on a convenient stratification of . This stratifies locally into complete intersections. The cubic cyclides are located at infinity of , and the equations defining the cubic (also known as parabolic) Dupin cyclides are formulated in Theorem 2. The variety of cubic Dupin cyclides is a complete intersection already. It contains the Zariski closure of in , as pointed out in Section 5. The requisite extensive computations with Gröbner bases were carried out using the computer algebra systems Maple 2018 and Singular 4.2.1.

An algorithm for recognizing Dupin cyclides based on the results of this article is implemented in Maple. It is available at https://github.com/menjanahary/DupinRecognitionAlgorithm (accessed on 29 July 2024). We checked the efficiency of this implementation on a five-parameter family of cyclide equations constructed following the classical definition [12,17,27] of Dupin cyclides as the envelope of a one-parameter family of spheres touching three fixed spheres. Let us specify a sphere by its center c and the radius r. The tangential distance between two spheres and equals . Up to Euclidean transformations and scaling, we can assume that the three fixed spheres generating a Dupin cyclide are given by , , . Following Darboux [28], a point X on the Dupin cyclide is treated as a sphere with a radius of zero. The Dupin cylide defined by satisfies the equation

where and . Using the localized formulation in Theorem 1, the Maple implementation took about 136 s CPU time (on AMD Ryzen 5 4500U processor running at 2.38 GHz) to decide that this equation indeed defines a Dupin cyclide generally. The large defining equations of Proposition 1 could not be checked within a reasonable time for this particular example.

The main results of this article were used recently [29] for deriving algebraic conditions for blending Dupin cyclides along a fixed circle. An important problem for future work is to understand the geometric meaning of linear subspaces within the variety of Dupin cyclides. For instance, some lines in this variety represent Dupin cyclides that blend smoothly along a Villarceau circle ([29], § 6.2). Another research direction is to determine the number of non-degenerate Dupin cyclides that a line in can contain. This problem is related to the task of fitting nine generic points with Dupin cyclides. This will enhance our understanding of the capacity of Dupin cyclides in geometric fitting problems. The problem of fitting cones, cylinders, and toruses through a set of points is solved already in [30,31].

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, J.M.M. and R.V.; writing—review and editing, J.M.M. and R.V.; methodology, J.M.M. and R.V.; software, J.M.M. and R.V.; visualization, J.M.M. and R.V.; investigation, J.M.M. and R.V.; conceptualization, R.V.; supervision, R.V.; project administration, R.V.; funding acquisition, J.M.M. and R.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is part of a project that has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 860843.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Darboux, G. Principes de Géométrie Analytique; Gauthier-Villars: Paris, France, 1917. [Google Scholar]

- Pottmann, H.; Shi, L.; Skopenkov, M. Darboux cyclides and webs from circles. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 2012, 29, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Krasauskas, R.; Zube, S. Kinematic interpretation of Darboux cyclides. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 2020, 83, 101945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Jia, X.; Tu, C.; Mourrain, B.; Wang, W. Enumerating the morphologies of non-degenerate Darboux cyclides. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 2019, 75, 101776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.R. Principal patches—A new class of surface patch based on differential geometry. In Eurographics’83; Ten Hagen, P.J.W., Ed.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1983; pp. 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, M.J. Cyclides in computer aided geometric design. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 1990, 7, 221–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.J. Cyclides in computer aided geometric design II. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 1995, 12, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druoton, L.; Langevin, R.; Garnier, L. Blending canal surfaces along given circles using Dupin cyclides. Int. J. Comput. Math. 2014, 91, 641–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.; Dutta, D. Cyclides in pure blending I. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 1997, 14, 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.; Dutta, D. Cyclides in pure blending II. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 1997, 14, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zube, S.; Krasauskas, R. Representation of Dupin cyclides using quaternions. Graph. Models 2015, 82, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasauskas, R.; Mäurer, C. Studying cyclides with Laguerre geometry. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 2000, 17, 101–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peternell, M.; Pottmann, H. A Laguerre geometric approach to rational offsets. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 1998, 15, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, R. Circles on surfaces in the Euclidean 3-space. In Geometry and Differential Geometry; Artzy, R., Vaisman, I., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1980; pp. 213–221. [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi, N. Cyclides. Hokkaido Math. J. 2000, 29, 119–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastl, B.; Jüttler, B.; Lávička, M.; Schulz, T.; Šír, Z. On the parameterization of rational ringed surfaces and rational canal surfaces. Math. Comput. Sci. 2014, 8, 299–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandru, V.; Dutta, D.; Hoffmann, C.M. On the geometry of Dupin cyclides. Vis. Comput. 1989, 5, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottens, L. Dupin Cyclides. Bachelor’s Thesis, Faculty of Science and Engineering, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth, A. Lectures on the Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1912. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, D.; Little, J.; O’Shea, D.; Sweedler, M. Ideals, Varieties, and Algorithms; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1997; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- van der Valk, M. On Dupin Cyclides. Bachelor’s Thesis, Faculty of Science and Engineering, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yvon Villarceau, A.J. Extrait d’une note communiquée à M. Babinet par M. Yvon Villarceau. C. R. Hebd. Séances l’Acad. Sci. 1848, 27, 246. [Google Scholar]

- Weisstein, E.W. Villarceau Circles. 2008. Available online: https://mathworld.wolfram.com/VillarceauCircles.html (accessed on 29 July 2024).

- White, J.H. A global invariant of conformal mappings in space. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 1973, 38, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmore, T.J. Riemannian Geometry; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rigaud, G.; Hahn, B. Reconstruction algorithm for 3D Compton scattering imaging with incomplete data. Inverse Probl. Sci. Eng. 2020, 29, 967–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupin, C. Applications de Géométrie et de Méchanique; Bachelier: Paris, France, 1822. [Google Scholar]

- Darboux, G. Sur les sections du tore. Nouvelles Ann. Math. 1864, 3, 156–165. [Google Scholar]

- Menjanahary, J.M.; Vidunas, R. Dupin cyclides passing through a fixed circle. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buse, L.; Galligo, A.; Zhang, J. Extraction of cylinders and cones from minimal point sets. Graph. Models 2016, 86, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buse, L.; Galligo, A. Extraction of tori from minimal point sets. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 2017, 58, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).