Abstract

Under-dispersed count data often appear in clinical trials, medical studies, demography, actuarial science, ecology, biology, industry and engineering. Although the generalized Poisson (GP) distribution possesses the twin properties of under- and over-dispersion, in the past 50 years, many authors only treat the GP distribution as an alternative to the negative binomial distribution for modeling over-dispersed count data. To our best knowledge, the issues of calculating maximum likelihood estimates (MLEs) of parameters in GP model without covariates and with covariates for the case of under-dispersion were not solved up to now. In this paper, we first develop a new minimization–maximization (MM) algorithm to calculate the MLEs of parameters in the GP distribution with under-dispersion, and then we develop another new MM algorithm to compute the MLEs of the vector of regression coefficients for the GP mean regression model for the case of under-dispersion. Three hypothesis tests (i.e., the likelihood ratio, Wald and score tests) are provided. Some simulations are conducted. The Bangladesh demographic and health surveys dataset is analyzed to illustrate the proposed methods and comparisons with the existing Conway–Maxwell–Poisson regression model are also presented.

Keywords:

generalized Poisson distribution; mean regression model; MM algorithms; over-dispersion; under-dispersion MSC:

62-08

1. Introduction

Under-dispersed count data often appear in clinical trials, medical studies, demography, actuarial science, ecology, biology, industry and engineering. Examples include the number of embryonic deaths in mice in a clinical experiment [1], the number of power outages on each of 648 circuits in a power distribution system in the southeastern United States [2], the number of automotive services purchased on each visit for a customer at a US automotive services firm [3], the species richness that is the simplest measure of species diversity [4], the number of births during a period for women who live in Bangladesh (https://www.dhsprogram.com/data, accessed on 28 January 2022) and so on.

The Poisson distribution is suitable for modeling equally dispersed count data, while the negative binomial distribution is often utilized to model over-dispersed count data. To fit under-dispersed count data, theoretically speaking, researchers should employ the generalized Poisson (GP) distribution because it possesses the twin properties of under- and over-dispersion [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. However, in the past 50 years, most authors just treat the GP distribution as an alternative to the negative binomial distribution by eyeing the former’s over-dispersion property, while seeming to ignore its under-dispersion characteristic [6,8,9,10,11,12,13], although Consul & Famoye [6] proved that there exist unique MLEs of parameters for both over- and under-dispersion cases. The main reason for hindering researchers from using the GP distribution with under-dispersion is that calculating the maximum likelihood estimates (MLEs) of parameters in GP models without/with covariates by a stable algorithm is not so easy. To our best knowledge, the issue of calculating MLEs of parameters in the GP model without/with covariates for the case of under-dispersion was not solved up to now; in other words, we may not obtain the correct MLEs of parameters by using the existing algorithms, see Section 5.

A non-negative integer-valued random variable (r.v.) X is said to follow a generalized Poisson (GP) distribution with parameters and , denoted by , if its probability mass function (pmf) is given by [5,14]

where and is the largest positive integer for which when . The expectation and variance of X are given by [14]

respectively. The distribution reduces to the when , and it has the twin properties of over-dispersion when and under-dispersion when .

To formulate the mean regression of the GP distribution, Consul & Famoye [7] introduced a so-called Type I generalized Poisson () distribution, denoted by , through the following reparameterizations:

It is easy to show that the pmf of Y is

where , and is the largest positive integer for which when . The mean and variance of Y are given by:

respectively, where denotes the square root of the index of dispersion. The distribution reduces to the when , and it has the twin properties of over-dispersion when and under-dispersion when . Thus, the mean regression model for the distribution is [7]

where the notation “” means that follow the same distribution family but with different mean parameters , and are independent; is the covariate vector of subject i and is the vector of regression coefficients.

This paper mainly focuses on developing two new MM algorithms to stably calculate the MLEs of parameters in the distribution with under-dispersion (i.e., ) and the MLEs of the vector of regression coefficients and the parameter for the mean regression model in (3). Besides, we want to compare the performance of goodness-of-fit and computational efficiency between the mean regression model and the Conway–Maxwell–Poisson regression model in simulations and real data analysis.

2. MLEs of Parameters in Generalized Poisson with Under–Dispersion and Its Mean Regression Model

Let and denote the observed counts. Define

Let denote the number of elements in for , then we have . Based on (2), the likelihood function of is

where and . Then, the log-likelihood function of is given by

where is a constant free from .

2.1. MLEs of via a New MM Algorithm

This subsection aims to find the MLEs of for the case of . Define . Because for all , we have . Thus, we obtain

for all , where

and is a constant free from .

2.2. MLEs of in the Mean Regression Model

In this subsection, we consider the mean regression model (3) with . Similar to (4), the log-likelihood function of is given by

where , , , and is a constant free from . The goal is to calculate the MLEs of .

2.2.1. MLE of Given

Since , we have

According to (8), we know that , thus . Given and , to calculate the -th approximation of , we first restrict in the following convex set

where is the midpoint of the two endpoints of the open interval and . Then, for any , since , we have

On the other hand, we define

By combining (9) with (11), we have

i.e., is a positive semi-definite matrix. By applying the second-order Taylor expansion of around , we have

where the equality holds iff , and . Let denote the conditional log-likelihood function of given , we have

which minorizes at , where is a constant free from .

Note that the is a weighted log-likelihood function of for the Poisson regression model with weight vector and observations with

We can calculate the MLEs of , denoted by , of the weighted Poisson regression model directly through the built-in ‘glm’ function in the VGAM R package. Since is restricted in the convex set , we project on the convex set , and calculate the -th approximation of as

where

2.2.2. MLE of Given

Define . Given , we have

where is a constant free from and

Let denote the conditional log-likelihood function of given , we have

which minorizes at , where is a constant free from . By setting , we have the following MM iterates:

where

3. Hypothesis Testing

For the mean regression model (3), suppose that we are interested in testing the following general null hypothesis:

where is a known matrix with , is the vector of parameters and is a known vector.

3.1. The Likelihood Ratio Test

Let be given by (8). The likelihood ratio statistic is given by

where is the unconstrained MLEs of , which can be calculated by the MM algorithm (14) and (16); while is the constrained MLEs of under . asymptotically follows a chi-squared distribution with degrees of freedom. The corresponding p-value is

where is the estimated likelihood ratio statistic.

3.2. The Wald Test

The Wald statistic is given by

where denotes the unconstrained MLEs of and is the Fishier information matrix (see Appendix B) evaluated at . is asymptotically distributed as a chi-squared distribution with degrees of freedom. The corresponding p-value is

where is the estimated Wald statistic.

3.3. The Score Test

The score statistic is given by

where denotes the constrained MLEs of under , and

with details being presented in Appendix B. is asymptotically distributed as a chi-squared distribution with degrees of freedom. The corresponding p-value is

where is the estimated score statistic.

4. Simulations

4.1. Accuracy of MLEs of Parameters

To investigate the accuracy of MLEs of parameters, we consider dimensions: . The sample sizes are set to be ; and other parameters are set as follows:

- (A1)

- When , ; , with ;

- (B1)

- When , ; , , , .

For a given , we first generate , and then generate by the inversion method [15] based on the pmf given by (2). Then, we can calculate the MLEs via the MM algorithm (14) and (16) with the generated and corresponding covariate vectors . Finally, we independently repeat this process 10,000 times.

The resultant average bias (denoted by Bias; i.e., average MLE minus the true value of the parameter) and the mean square error (denoted by MSE; i.e., Bias2 + (standard deviation), the standard deviation is estimated by the sample standard deviation of 10,000 MLEs) are reported in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Parameter estimates based on 10,000 replications for Case (A1).

Table 2.

Parameter estimates based on 10,000 replications for Case (B1).

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

In this subsection, we explore the performances of the likelihood ratio, Wald and score statistics presented in (18)–(20) for the hypothesis testing in (17) with various parameter configurations. The sample sizes are set to be , where means from to with step size s, and other parameters are set as follows:

- (A2)

- When , , is set to be , , and , so that (17) becomes . The true value of in is , while the value of in is . We generate and set ;

- (B2)

- When , , is set to be ,so that (17) becomes . The true value of in is and the value of in is . We generate , , , and set ;

- (A3)

- When , , , and , so that (17) becomes . The alternative values of in are set as 0.9 and 0.95. We generate and set ;

- (B3)

- When , , , and , so that (17) becomes . The alternative values of in are set as 0.9 and 0.95. We generate , , , and set .

All hypothesis testings are conducted at a significant level of 0.05. To calculate the empirical levels of the three tests, we first generate under . Repeating this process for L (=10,000) times, we obtained . Since our MM algorithm (14) & (16) is designed for , we apply two-stage method to obtain the MLEs of for the regression model. In the first stage, we calculate the MLEs via the MM algorithm (14) & (16) with the generated and corresponding covariate vectors . If the estimated , implying that the dataset is under-dispersed, we shall keep the estimation result and will not go to the second stage. If the estimated , implying that the dataset may be equal- or over-dispersion, we shall go to the next stage; that is recalculating the MLEs through the ‘vglm’ function by choosing family as ‘genpoisson1’ in VGAM R package because this function can only calculate the MLEs of the parameter when . Let denote the number of rejecting the null hypothesis by the likelihood ratio, Wald and score statistics, respectively. Hence, the actual significance level can be estimated by under . Similarly, we generate under . Repeating this process for L (=10,000) times, we obtained . The empirical power can be estimated similarly to the empirical level. All results are reported in Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8.

Table 3.

The empirical levels of statistics (, , ) for Case (A2).

Table 4.

The empirical powers of statistics (, , ) for Case (A2).

Table 5.

The empirical levels of statistics (, , ) for Case (B2).

Table 6.

The empirical powers of statistics (, , ) for Case (B2).

Table 7.

The empirical levels/powers of statistics (, , ) for Case (A3).

Table 8.

The empirical levels/powers of statistics (, , ) for Case (B3).

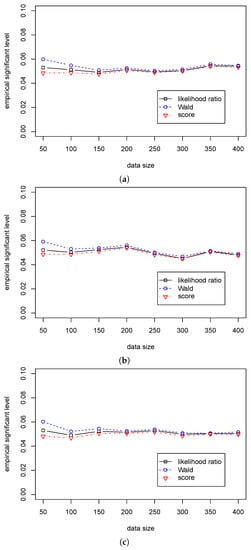

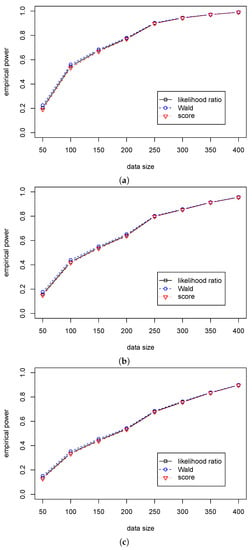

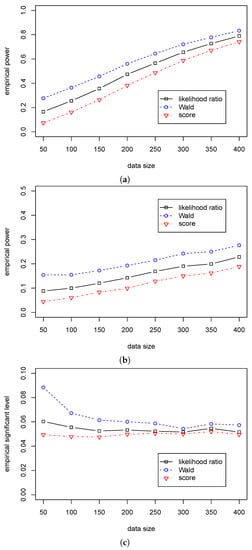

Table 3 shows that the significant levels in the three statistics are around 0.05 for different sample sizes. Table 4 shows that the Wald statistic outperforms the likelihood ratio statistic, and the likelihood ratio statistic outperforms the score statistic. At the same time, the differences in the empirical powers among the three tests are very small. So, we can use the likelihood ratio, Wald, and score statistics for the regression hypothesis testing for various values of when . The differences in performance among the three statistics are presented in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1.

The empirical levels of three test statistics (, , ) for testing in Case (A2) for different . (a) The empirical level with for ; (b) The empirical level with for ; (c) The empirical level with for .

Figure 2.

The empirical powers of three test statistics (, , ) for testing in Case (A2) for different ’s. (a) The empirical power with for ; (b) The empirical power with for ; (c) The empirical power with for .

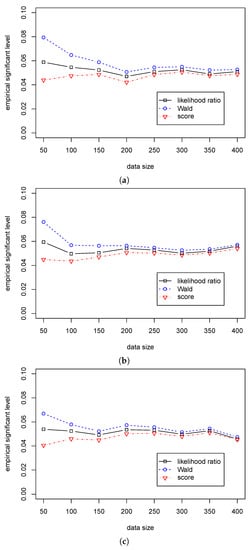

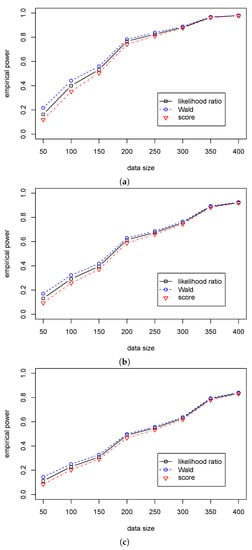

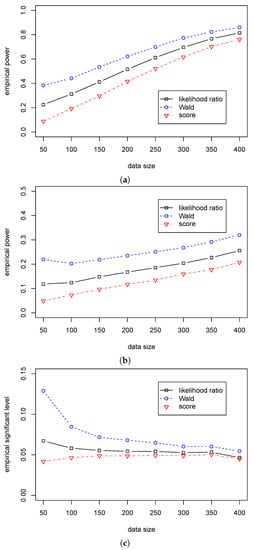

Table 5 shows that the significant level in the likelihood ratio and the score statistics are around 0.05 for different sample sizes, while the significant levels in Wald statistic are around 0.07 for different when and quickly decrease to 0.05 with the growth of sample size. Table 6 shows that the Wald statistic outperforms the likelihood ratio statistic, and the likelihood ratio statistic outperforms the score statistic. Unlike the differences in the empirical power among the three tests are small in Case (A2), Table 5 shows that the differences are more considerable in Case (B2). So, we can use the likelihood ratio and score statistics for the regression hypothesis testing for various values of and different samples size when . Furthermore, we can use the Wald statistic when the sample size is more than 100. The differences in performance among the three statistics are presented in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Figure 3.

The empirical levels of three test statistics (, , ) for testing in Case (B2) for different . (a) The empirical level with for ; (b) The empirical level with for ; (c) The empirical level with for .

Figure 4.

The empirical powers of three test statistics (, , ) for testing in Case (B2) for different . (a) The empirical power with for ; (b) The empirical power with for ; (c) The empirical power with for .

According to Table 7 and Table 8, we can see that the Wald statistic outperforms the other two statistics in Cases (A3)–(B3), and the likelihood ratio statistic outperforms the score statistic. Figure 5 and Figure 6 show a significant difference in empirical power among the three statistics. Furthermore, we can see that the empirical significant levels for the likelihood ratio and score statistics are satisfactorily controlled. In contrast, the significant level for the Wald statistic is over 0.08 when and gradually decreases to 0.05 with the growth of the sample size. So, we suggest using the likelihood ratio statistic for the dispersion hypothesis testing when the sample size is less than 200; and using the Wald statistic when the sample size is more than 200.

Figure 5.

The empirical powers/level of three test statistics (, , ) for testing in Case (A3) for different . (a) The empirical power with for ; (b) The empirical power with for ; (c) The empirical significant level with for .

Figure 6.

The empirical powers/level of three test statistics (, , ) for testing in Case (B3) for different . (a) The empirical power with for ; (b) The empirical power with for ; (c) The empirical significant level with for .

4.3. Comparisons of the Regression Model with the Conway–Maxwell–Poisson Regression Model

To compare the performance of the goodness-of-fit tests and computational complexity in the regression model (3) and the Conway–Maxwell–Poisson (CMP) regression model, we consider using both models to fit a dataset, which is generated from one of the two models. A discrete r.v. Y is said to follow the CMP distribution with parameters and , denoted by , if its pmf is [16]:

where is a normalizing constant and is the dispersion parameter. The distribution reduces to the when , and it has the twin properties of over-dispersion when and under-dispersion when . The CMP regression model [3,17] is:

The sample size is set to be , , , , , , and other parameter configurations are set as follows:

- (A4)

- For a fixed , set and generate with for .

- (B4)

- For a fixed , set and generate with for .

To assess the performance of the two models, we use the following three criteria: The average Akaike information criterion (AIC), the average Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and the average Pearson chi-squared statistic [18]:

where and are the estimated mean and variance of and is the degree of the Pearson chi-squared statistic because we use the MLEs or to calculate . To show the differences in performance in the two models with the same data set, we first generate a data set from (A4) and estimate parameters with the and CMP regression models 1000 times. Specifically, we can calculate the MLEs of parameters for the regression model with the MM Algorithm (14) & (16). The MLEs of parameters of the CMP regression model can be calculated directly through the built-in ‘glm.cmp’ function in the COMPoissonReg R package. Next, we generate another data set from (B4) and estimate these parameters with the two models. By averaging the obtained results, the log-likelihood, AIC, BIC, and the time cost of the system when the algorithm converged (denoted by Sys. Time) are reported in Table 9.

Table 9.

Model comparisons based on 1000 replications for Cases (A4) & (B4).

According to Table 9, in Case (A4), we can see that the log-likelihood of the regression model is larger than that of the CMP regression model, and the AIC and BIC of the regression model are smaller than that of the CMP regression model. However, the values of the log-likelihood, AIC and BIC show an inverse numerical relationship between and CMP regression models in Case (B4). So, the /CMP regression model performs better log-likelihood, AIC, and BIC when the data is generated from /CMP. For the Pearson chi-squared statistic, the regression model outperforms the CMP regression model in Case (A4) because the value of is closer to the degree of the Pearson chi-squared statistic, 995. In Case (B4), the of the regression model is greater than 995 by around 5, and the of the CMP regression model is less than 995 by around 5, implying they have similar performances. For the cost of time, our proposed regression model converges faster than the CMP model in simulation, in which the time cost of the regression model is nearly half of the CMP regression model.

5. Births in Last Five Years for Women in Bangladesh

The dataset is obtained from the Bangladesh demographic and health surveys (DHS) program (https://www.dhsprogram.com/data, accessed on 28 January 2022), recording several variables, e.g., Age, Education (educational level), Religion and Division, from 9067 women who are aged between 30 and 35. Our goal is to understand better the relationship between Births (births in the last five years) and its relevant explanatory variables. In this section, we construct a regression model to link the mean of Births with the values of Age, Education, Religion and Division and the mean regression model is presented as follows:

Meanwhile, for comparisons, we also use the CMP regression model to fit the Bangladesh DHS data

The MLEs of parameters for the regression model in (21) can be calculated through the proposed MM algorithm (14) and (16) and the MLEs of parameters for the regression model in (22) can be calculated through the built-in ‘glm.cmp’ function in the COMPoissonReg R package. For a fixed j (), the Std of calculated by the Wald statistic for testing is , where denotes the 15-dimensional vector with 1 for the -th element and 0’s elsewhere and is the Fisher information matrix in Appendix B. Thus, the z-values (i.e., MLE/Std) and p-values can be calculated by the MLEs and their Stds and the estimation results of the and the CMP regression models are presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

MLEs and CIs of parameters for the regression model in (21) and CMP regression model.

Table 10 indicates that the Age coefficient is implying that the Age affects the number of births in the past five years negatively; that is, the willingness to give birth decreases as the growth of ages. The coefficients of Education shows that women with Higher education levels have more births than those with Primary and Secondary education levels. For the religious factor, we realize that there is no significant difference between women, whether Islam, Hinduism, or Christianity. Finally, we can see that the number of births varies widely depending on the Division where they live. More specifically, women who live in Chittagong, Mymensingh and Sylhet are willing to birth more kids, while those who live in Dhaka, Khulna, Rajshahi and Rangpur choose fewer births.

Table 10 shows that there exists minor difference of the coefficients between the and CMP regression models. The coefficients of Education shows that the Primary and Secondary, respectively, fails to pass the null hypotheses and in the CMP regression model under the significant level 5% because their corresponding p-values are both larger than 0.05. However, the two explanatory factors are significant in the regression model under the above conditions. It deserves to note that the regression links the mean with the covariate vector directly, so the model is of statistical meaning. However, the CMP regression lacks such statistical meanings because the regression model only constructs a connection between the parameter with the subject’s personalities.

Furthermore, to have a better understanding of the advantages of the proposed MM algorithm (14) and (16), we apply the existing ‘vglm’ function in VGAM R package to calculate the MLEs of the regression model in (3). Further, we choose two functions ‘genpoisson0’ and ‘genpoisson’ in ‘vglm’ to calculate the MLEs of the parameters, in which the ‘genpoisson0’ function restricts while the ‘genpoisson’ function allows . The criteria for the goodness-of-fit, like AIC, BIC and the Pearson chi-squared statistic, can be calculated by the obtained MLEs, the number of parameters, sample size, and log-likelihoods. The results are presented in Table 11.

Table 11.

Comparisons of goodness-of-fit among the regression model, CMP regression model, log-lambda based GP regression model with constraint and the log-lambda based GP regression model without constraint on .

Table 11 shows that the regression model estimated by the proposed MM algorithm and the CMP regression model share similar performance of the goodness-of-fit statistics, like AIC, BIC and Person Chi-square statistic, implying that both models fit the data set well. However, our MM algorithm converges to the as nearly five times faster than the ‘glm.cmp’ function for calculating the CMP regression model. We can also see that the log-likelihood, AIC, BIC and obtained through genpoisson0 and genpoisson functions perform much worse than and CMP regression models, even though they have a relatively less time for computation.

To test the dispersion, we use the likelihood ratio, Wald and score statistics, which have been proved efficiently for large sample sizes in Cases (A3)–(B3) in Section 4.2. The results in Table 12 show that the p-values of the three tests are zeros, implying that the null hypothesis : should be rejected.

Table 12.

Dispersion test for testing : .

6. Discussion

In the present paper, given , to avoid directly calculating in the maximization of the original log-likelihood function , we successfully constructed a surrogate function , which is equivalent to the log-likelihood function in a weighted Poisson regression, so that we can compute directly by using the VGAM R package. By projecting on the convex set , we calculated as shown in (14). Besides, given , we obtained an explicit expression for by maximizing a surrogate function . The simulation and real data analysis results showed that the proposed MM algorithms could stably obtain the MLEs of parameters for the distribution without/with covariates for various parameter configurations, while the built-in ‘genpoisson1’ function in the VGAM R package may converge to a wrong estimate of parameters. Besides, the results of the comparison between the proposed model and the existing CMP regression model reflected that the two models possess similar performance from the aspect of the goodness-of-fit. However, the proposed model outperforms the CMP regression model regarding computational efficiency and statistical meanings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.-J.L. and G.-L.T.; Methodology, X.-J.L. and G.-L.T.; Formal analysis, X.-J.L.; Investigation, M.Z., G.T.S.H. and S.L.; Resources, M.Z., G.T.S.H. and S.L.; Data curation, M.Z., G.T.S.H. and S.L.; Writing—original draft, X.-J.L.; Writing—review & editing, X.-J.L. and G.-L.T.; Supervision, G.-L.T.; Funding acquisition, G.-L.T. and G.T.S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China: 12171225; Research Grants Council of Hong Kong: UGC/FDS14/P05/20; Big Data Intelligence Centre in The Hang Seng University of Hong Kong.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: [https://www.dhsprogram.com/data].

Acknowledgments

Guo-Liang TIAN’s research was partially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12171225). G.T.S Ho would like to thank the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong for supporting this research under the Grant UGC/FDS14/P05/20. Furthermore, this research is also supported partially by the Big Data Intelligence Centre in The Hang Seng University of Hong Kong.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Discrete Version of Jensen’s Inequality

Let is a concave function defined on a convex set , i.e., for all . The discrete version of Jensen’s inequality is

which is true for any probability weights satisfying: and . Especially, in (A1) set , , and suppose that and , then we obtain

where the equality holds iff , is a constant free from , and

Appendix B. The Gradient Vector and Fisher Information Matrix

The gradient vector of with respect to and are given by

The Hessian matrix is

where

The Fisher information matrix is given by

where

References

- Saha, K.K. Analysis of one-way layout of count data in the presence of over or under dispersion. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 2008, 138, 2067–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guikema, S.D.; Goffelt, J.P. A flexible count data regression model for risk analysis. Risk Anal. Int. J. 2008, 28, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, K.F.; Borle, S.; Shmueli, G. The COM-Poisson model for count data: A survey of methods and applications. Appl. Stoch. Model. Bus. Ind. 2012, 28, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, H.J.; Thorson, J.T.; Shelton, A.O. Dealing with under- and over-dispersed count data in life history, spatial, and community ecology. Ecology 2014, 95, 3173–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consul, P.C.; Jain, G.C. A generalization of the Poisson distribution. Technometrics 1973, 15, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consul, P.C.; Famoye, F. The truncated generalized Poisson distribution and its estimation. Commun. Stat.–Theory Methods 1989, 18, 3635–3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consul, P.C.; Famoye, F. Generalized Poisson regression model. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 1992, 21, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angers, J.F.; Biswas, A. A Bayesian analysis of zero-inflated generalized Poisson model. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2003, 42, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joe, H.; Zhu, R. Generalized Poisson distribution: The property of mixture of Poisson and comparison with negative binomial distribution. Biom. J. 2005, 47, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Hardin, J.W.; Addy, C.L.; Vuong, Q.H. Testing approaches for over-dispersion in Poisson regression versus the generalized Poisson model. Biom. J. 2007, 49, 565–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Hardin, J.W.; Addy, C.L. A score test for over-dispersion in Poisson regression based on the generalized Poisson-2 model. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 2009, 139, 1514–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, K.F.; Morris, D.S. Underdispersion models: Models that are “under the radar”. Commun. Stat.–Theory Methods 2017, 46, 12075–12086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, D.; Umetsu, C.A.; Camargo, A.F.M.; de Lara, I.A.R. Flexible models for non-equidispersed count data: Comparative performance of parametric models to deal with under-dispersion. AStA Adv. Stat. Anal. 2022, 106, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consul, P.C.; Shoukri, M.M. The generalized Poisson distribution when the sample mean is larger than the sample variance. Commun. Stat.–Theory Methods 1985, 14, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seber, G.A.F.; Salehi, M.M. Adaptive Sampling Designs: Inference for Sparse and Clustered Populations, Chapter 5: Inverse sampling methods; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shmueli, G.; Minka, T.P.; Kadane, J.B.; Borle, S.; Boatwright, P. A useful distribution for fitting discrete data: Revival of the Conway–Maxwell–Poisson distribution. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C (Appl. Stat.) 2005, 54, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, K.F.; Shmueli, G. A flexible regression model for count data. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2010, 4, 943–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.C.; Trivedi, P.K. Regression Analysis of Count Data, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).