Abstract

In this article, based on the regularization techniques, we construct two new algorithms combining the forward-backward splitting algorithm and the proximal contraction algorithm, respectively. Iterative sequences of the new algorithms can converge strongly to a common solution of the variational inclusion and null point problems in real Hilbert spaces. Multi-inertial extrapolation steps are applied to expedite their convergence rate. We also give some numerical experiments to certify that our algorithms are viable and efficient.

Keywords:

variational inclusion; null point; regularized method; multi-step inertial iteration; strong convergence MSC:

47H04; 47H05; 47H10; 65K10

1. Introduction

Let H be a real Hilbert space such that norm is and the inner product is , respectively. We recall that the variational inclusion problem (VIP):

where is a set-valued operator and is a single-valued operator. We denote the solution set of (1) by . The variational inclusion problem is a crucial extension of the variational inequality problem. Many nonlinear problems such as problems of saddle point, minimization, and split feasibility can be transformed into variational inclusion problems which can be applied to signal processing, neural networks, medical image reconstruction, machine learning, and data mining, etc., see [1,2,3,4,5,6,7].

As we all know, (1) can be converted to the fixed point equation for some , where is the resolvent operator of A. The famous forward–backward splitting method (FBSM) was proposed by Lions and Mercier [8] in 1979:

where A and B are maximally monotone and -inverse strongly monotone, respectively, . Note that the Lipschitz continuity of an operator is a weaker property than the inverse strong monotonicity. So the algorithm has a shortcoming: the convergence requires a strong hypothesis. In order to overcome this difficulty, Tseng [9] constructed a modified forward–backward splitting algorithm (TFBSM) in 2000:

where B is monotone and Lipschitz continuous.

On the other hand, a famous method for solutions of variational inequalities is the projection and contraction method which was first introduced by He [10] for the variational inequality problem in Euclidean space. Inspired by this, the following proximal contraction method (PCM) was proposed by Zhang and Wang [11] in 2018:

where ,

, and the sequence of variable stepsizes satisfies some conditions. Notice that both (TFBSM) and (PCM) can only get weak convergent results in real Hilbert spaces. In general, weakly convergent results are obviously less popular than strongly convergent ones. In order to get the strong convergence, Hieu et al. [12] gave an algorithm named the regularization proximal contraction method (RPCM), for solving (1) in 2021:

where , , and satisfies some appropriate conditions. Before this, some scholars successfully applied this technique to the variational inequality problem. Very recently, Song and Bazighifan [13] introduced an inertial regularized method for solving the variational inequality and null point problem.

In recent years, there has been interest in methods with inertia which are considered effective methods to expedite the convergence. The inertial method is favored by many scholars because of its simple structure and easy operation, which is promoted by many scholars and in-depth research. In 2003, Moudafi and Oliny [14] combined (FBSM) with the inertial method to construct a new algorithm:

where is a positive real sequence. Furthermore, some scholars have proposed multi-step inertial methods. In 2021, Wang et al. [15] proposed the multi-step inertial hybrid method to solve the problem (1).

Inspired by [12,13,15], we consider the variational inclusion and null point problem:

where G and F are nonlinear operators. We propose two modified regularized multi-step inertial methods to solve the above problem. These two algorithms are the modified forward-backward splitting algorithm and the proximal contraction algorithm. Using regularization techniques, the new algorithms converge strongly under mild conditions. Some numerical examples are given to show that our algorithms are efficient.

This article is arranged as follows: we introduce some notations, fundamental definitions, and results that are used in later proofs in Section 2. In Section 3, we present the new algorithms and discuss their convergence. In Section 4, we report some numerical experiments to support our theoretical results obtained.

2. Preliminaries

Let H be a real Hilbert space. The weak convergence and strong convergence of sequence are denoted by and , respectively.

Definition 1

([16]). The mapping T: is called

- (i)

- monotone, if

- (ii)

- γ-strongly monotone (), if

- (iii)

- δ-inverse strongly monotone (), if

- (iv)

- l-Lipschitz continuous (), if

- (v)

- firmly nonexpansive, if

- (vi)

- nonexpansive, if

Definition 2

([16]). Let be a set-valued mapping. The graph of T is defined by . The mapping T is said to be

- (i)

- monotone, if

- (ii)

- maximally monotone, if T is monotone on H and for any ,

Lemma 1

([17]). Let be a maximally monotone operator, and be a monotone Lipschitz continuous operator. Then is maximally monotone.

Lemma 2

([18]). Let be a of nonnegative real sequence satisfying

where and satisfying the conditions:

- (i)

- , ;

- (ii)

- ;

- (iii)

- with .

Then

Lemma 3

([19]). Let C be a nonempty closed convex subset of H and be a nonexpansive mapping. Then, the mapping is demiclosed at zero, i.e., if and , then

3. Main Results

We mainly introduce our new algorithms and analyze their convergence in this section. Let H be a real Hilbert space. The following assumptions will be needed throughout the paper:

- (A1)

- is maximally monotone.

- (A2)

- is monotone and L-Lipschitz continuous.

- (A3)

- is -strongly monotone and k-Lipschitz continuous.

- (A4)

- is -inverse strongly monotone.

- (A5)

- , where is the solution set of (1).

To solve (2), we construct a auxiliary problem:

for each and , the solution of the problem (3) denoted by .

Lemma 4.

Under the assumptions (A1)–(A4), for each and , the problem (3) has a unique solution .

Proof.

Since the properties of A, B, G, and F in the hypothesis, we can conclude that is strongly monotone. It is well known that strong monotone operators have unique solutions (see [20]). Therefore, the problem (3) has a unique solution . □

Lemma 5.

The net is bounded.

Proof.

For each and , we have , and . Thus,

and

Using the monotonic property of and G, we derive

By (4) and the -strong monotonicity, it follows that

Consequently (5) and the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality, we find , then , we get

So the net is bounded. □

Lemma 6.

For all , there exists such that,

Proof.

According to the assumption, are solutions of the problem (3), let us suppose that . Then,

and

which implies

and

By Lemma 1, we know that

or, equivalently,

The properties of G and F and the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality imply that

which equal to

The Lipschitz continuity of the mapping F and G imply they are bounded. Combining the Lagrange’s mean-value theorem, we deduce that

this together with (6), implies that

where . Indeed, since F and G are Lipschitz continuous, the net and is bounded. If , we can also get the same results. □

Lemma 7.

Proof.

According to the conclusion of Lemma 5, there exists a subsequence of the net such that and as . From RVI, we have that . Let us take a point in , that is, . Thus, we derive by the assumption (A1),

Replace with , we deduce from the monotonicity of B that

It obtains that the sequence is bounded by the boundedness of the sequence and the Lipschitz continuity of F. Letting in relation (8) and we infer that

For every , and . By (3), we obtain

due to the definition of , we know that

by the monotonicity of F,

which leads to

For any , is nonexpansive obviously holds. Owing to Lemma 3, we obtain that ,

together with (9), implies

Noting (5), we obtain for all . Letting , we have

By Minty lemma [21], we get

Due to uniqueness of the solution to the problem (2), we have . Since is any point in , , that is, the net converges weakly to . After that, applying (5) for , we get

Taking limit in (11) as , we obtain

Thus, . □

Remark 1.

can be chosen as , where .

Lemma 8.

Under the condition (A2), the sequence generated by Algorithm 1 or Algorithm 2 is convergent and

To be more precise, we have .

| Algorithm 1 Modified multi-steps inertial forward-backward splitting method with regularization |

|

| Algorithm 2 Modified multi-steps inertial proximal contraction method with regularization |

|

Proof.

Since

in the case of ,

By induction, can draw the sequence has the lower bound . Since the computation of , we can get

that is

Let represent for all . And we know , then

Because , obviously

Besides , we infer

then,

Since has the lower bound , we know . So we have

furthermore,

Therefore, is convergent. □

Theorem 1.

If the conditions (A1)–(A5) hold, is the unique solution of problem (2) and the sequence is generated by Algorithm 1, then converges strongly to .

Proof.

Setting ,

Since

Let and be three positive numbers such that

By virtue of Lemma 8, and , there exists , such that

Because F is strongly monotone,

Theorem 2.

If the conditions (A1)–(A5) hold, is the unique solution of problem (2) and the sequence is generated by Algorithm 2, then converges strongly to .

Proof.

We have by Lemma 8, so for all , there exists and such that . We can also obtain , then is bounded. We will use the letter V to denote , obviously .

In the remainder proof, we assume that . Setting , then

In the meantime,

By the definition of ,

and

And then, by the properties of B and G, we infer that

Using the same method in the Theorem 1, we get

where . Cause , we assume . Hence

The remaining proofs are the same as Theorem 1. □

4. Numerical Experiments

Three examples are given to show the performances of our algorithms. When the coefficients of inertia are equal to zero, let us use MFBMR and MPCMR for Algorithms 1 and 2, respectively. We denote Algorithm 1 for by MIFBMR, 2-MMIFBMR and 3-MMIFBMR, respectively. Similarly denote Algorithm 2 for by MIPCMR, 2-MMIPCMR and 3-MMIPCMR, respectively. All the programmes are written in Matlab 9.0 and performed on PC Desktop Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-1035G1 CPU @ 1.00 GHz 1.19 GHz, RAM 16.0 GB.

Example 1.

Suppose . Let be a mapping defined as

and as

Set mapping as

It is obvious that A is maximally monotone. We can prove that B is monotone and Lipschitz continuous. We know G is -inverse strongly monotone by calculation. Let .

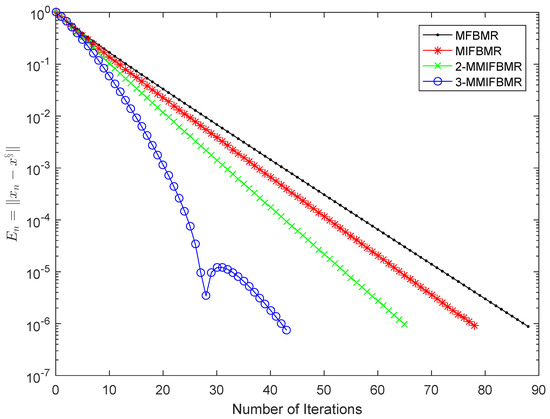

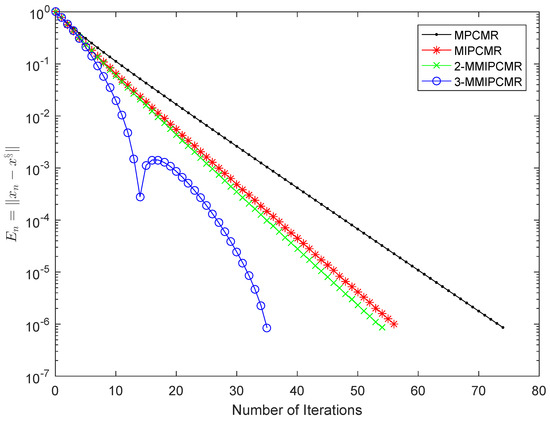

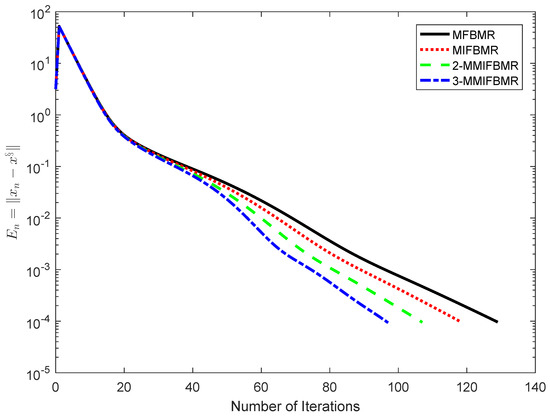

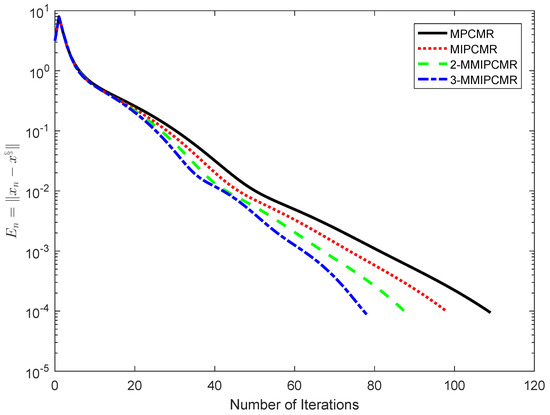

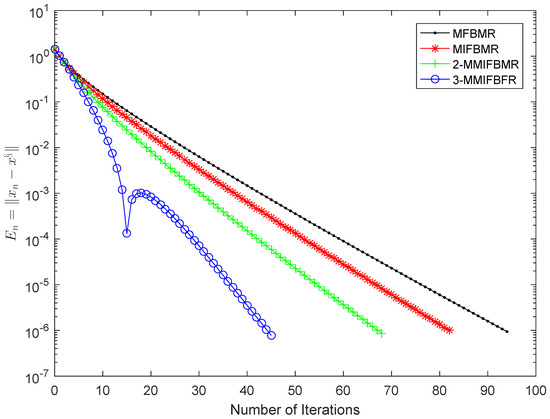

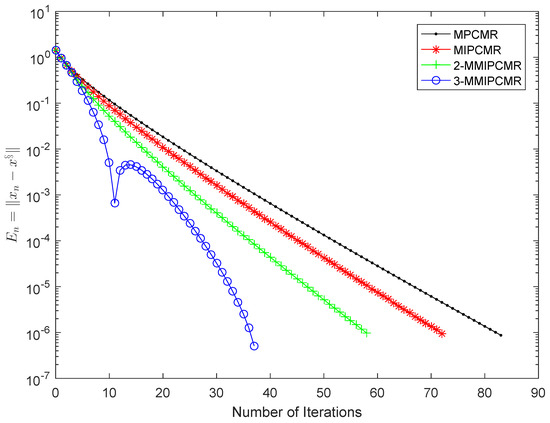

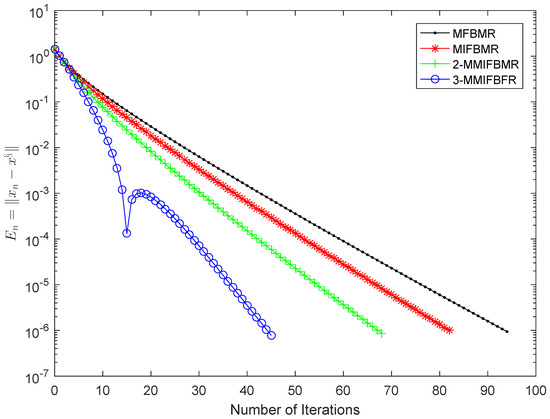

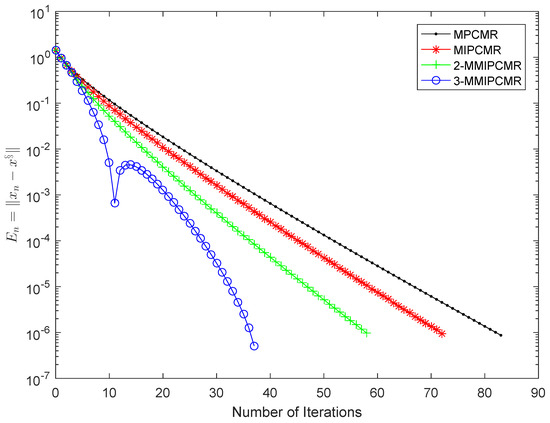

Choose , and for MIFBMR, 2-MMIFBMR, 3-MMIFBMR, MIPCMR, 2-MMIPCMR and 3-MMIPCMR. Choose , , , , and for each algorithm. Choose , for MPCMR, MIPCMR, 2-MMIPCMR, and 3-MMIPCMR. It is obvious that and is the only one solution of problem (2). The numerical results of this example are represented in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Comparison of MFBMR, MIFBMR, 2-MMIFBMR and 3-MMIFBMR in Example 1.

Figure 2.

Comparison of MPCMR, MIPCMR, 2-MMIPCMR and 3-MMIPCMR in Example 1.

Example 2.

Let . Let . Let be defined by

where J is an upper triangular matrix whose nonzero elements are all 1 in . Let be a mapping defined as

where

here C is a matrix, S is a skew-symmetric matrix and D is a diagonal matrix whose diagonal entries are positive. They all in . Therefore E is positive definite. Obviously, B is monotone and Lipschitz continuous. Define as

where Q is a nonzero matrix in . We know G is -inverse strongly monotone by calculation.

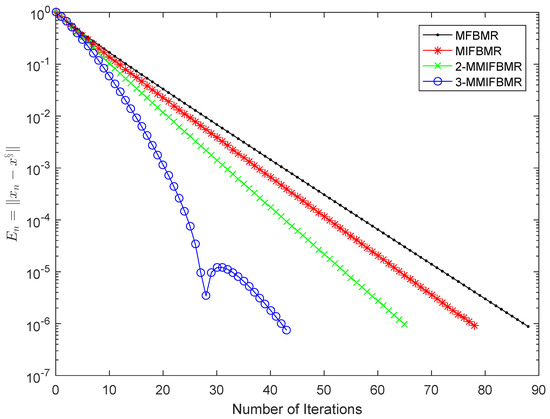

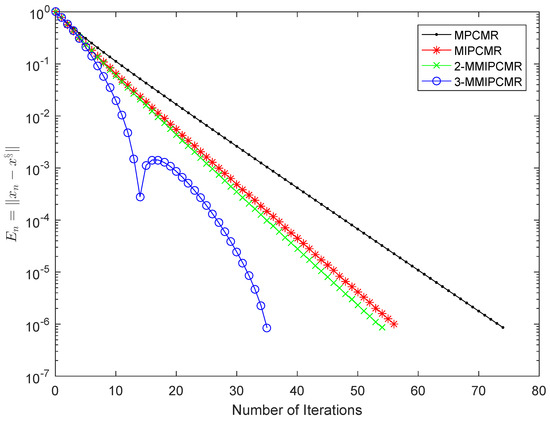

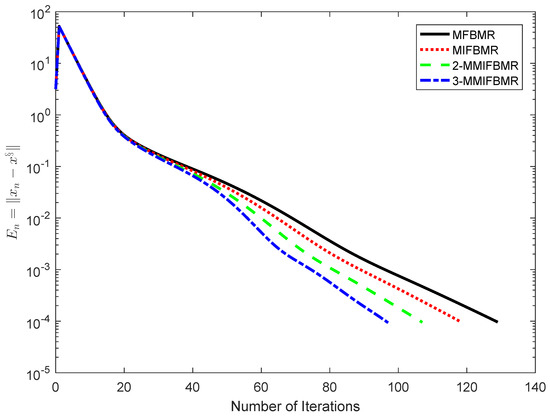

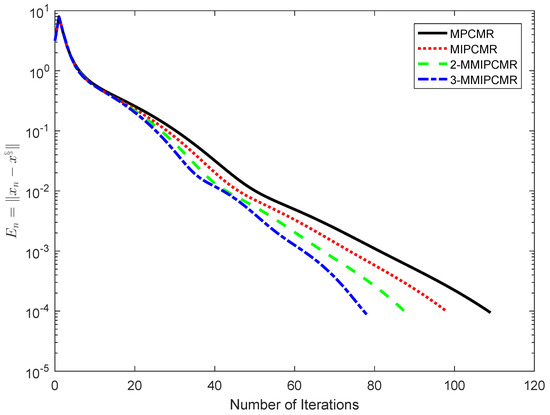

Choose , and for MIFBMR, 2-MMIFBMR, 3-MMIFBMR, MIPCMR, 2-MMIPCMR and 3-MMIPCMR. Choose , , , , and for each algorithm. Choose , for MPCMR, MIPCMR, 2-MMIPCMR and 3-MMIPCMR. All the diagonal elements of D are arbitrary in , the elements of C, S and Q are generated randomly in , and , respectively. It is obvious that and hence the solution of (2) is unique. The numerical results are represented in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Comparison of MFBMR, MIFBMR, 2-MMIFBMR and 3-MMIFBMR in Example 2 with .

Figure 4.

Comparison of MPCMR, MIPCMR, 2-MMIPCMR and 3-MMIPCMR in Example 2 with .

Example 3.

Let . Let be a mapping defined as

be a mapping defined as

and be a mapping defined as

Define as

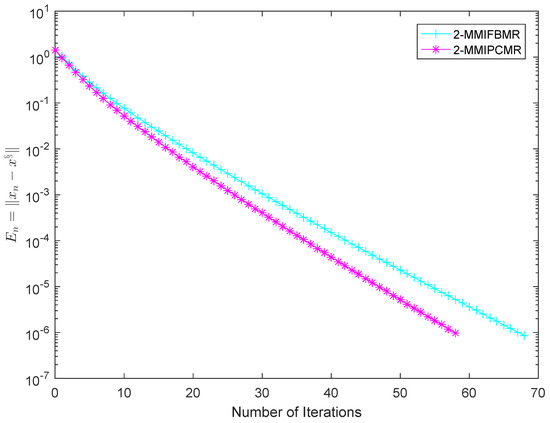

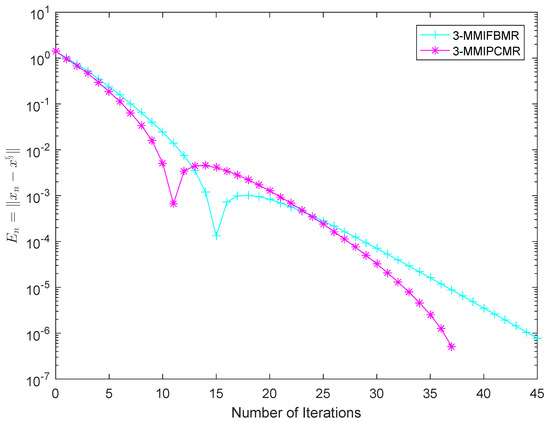

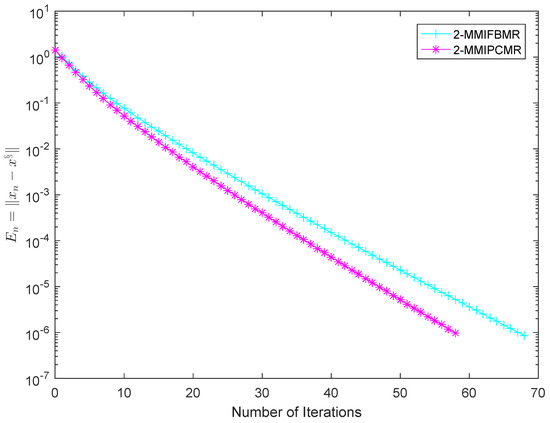

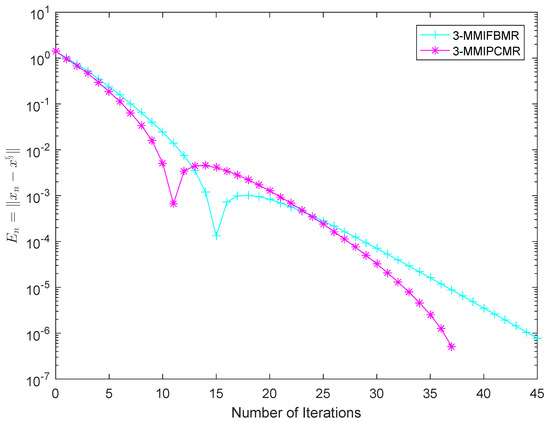

We can claim that B is monotone and -Lipschitz continuous, F is 1-strongly monotone and -Lipschitz continuous. We know G is 2-inverse strongly monotone by calculation. Choose , and for MIFBMR, 2-MMIFBMR, 3-MMIFBMR, MIPCMR, 2-MMIPCMR and 3-MMIPCMR. Choose , , , , and for each algorithm. Choose , for MPCMR, MIPCMR, 2-MMIPCMR and 3-MMIPCMR. It is obvious that and is the only solution of problem (2). The numerical results are represented in Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8.

Figure 5.

Comparison of MFBMR, MIFBMR, 2-MMIFBMR and 3-MMIFBMR in Example 3.

Figure 6.

Comparison of MPCMR, MIPCMR, 2-MMIFBMR and 3-MMIPCMR in Example 3.

Figure 7.

Comparison of 2-MMIFBMR and 2-MMIPCMR in Example 3.

Figure 8.

Comparison of 3-MMIFBMR and 3-MMIPCMR in Example 3.

Remark 2.

In Algorithms 1 and 2, the values of L, k and ξ are not necessary to be known.

5. Conclusions

We have introduce two improved regularized algorithms with multi-step inertia to solve the variational inclusion and null point problem in Hilbert spaces. Then we can get strong convergence without using the inverse strongly monotone assumption. Another advantage of our algorithms is that the stepsizes do not need to use the Lipschitz constant of the operator. In addition, the values of k, L, and are not needed in the calculation process, and the choice of seems harsh but is actually available, such as , . Finally, the feasibility and effectiveness of our algorithms can be seen in the figures of the numerical experiments. After this, a question is how to get strong convergence under weaker conditions. We will discuss and study this issue in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L.; Methodology, Y.W. and B.J.; Validation, Y.W., M.L. and C.Y.; Formal analysis, Y.W.; Investigation, M.L. and C.Y.; Resources, C.Y. and B.J.; Data curation, C.Y. and B.J.; Writing—original draft, M.L.; Writing—review & editing, B.J.; Project administration, Y.W., M.L. and C.Y.; Funding acquisition, Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 11671365).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

References

- Combettes, P.L.; Wajs, V.R. Signal recovery by proximal forward-backward splitting. Multiscale Model. Simul. 2005, 4, 1168–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daubechies, I.; Defrise, M.; De Mol, C. An iterative thresholding algorithm for linear inverse problems with a sparsity constraint. Comm. Pure Appl. Math. 2004, 57, 1413–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchi, J.; Singer, Y. Efficient online and batch learning using forward backward splitting. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2009, 10, 2899–2934. [Google Scholar]

- Raguet, H.; Fadili, J.; Peyré, G. A generalized forward-backward splitting. SIAM J. Imaging Sci. 2013, 6, 1199–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilshad, M.; Aljohani, A.F.; Akram, M.; Khidir, A.A. Yosida approximation iterative methods for split monotone variational inclusion problems. J. Funct. Space 2022, 2022, 3667813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, J.; Kumam, P.; Garba, A.I.; Abdullahi, M.S.; Ibrahim, A.H.; Sitthithakerngkiet, K. An inertial iterative scheme for solving variational inclusion with application to Nash-Cournot equilibrium and image restoration problems. Carpathian J. Math. 2021, 37, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeke, C.C.; Izuchukwu, C.; Mewomo, O.T. Strong convergence results for convex minimization and monotone variational inclusion problems in Hilbert space. Rend. Circ. Mat. Palermo Ser. 2 2020, 69, 675–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lions, P.L.; Mercier, B. Splitting algorithms for the sum of two nonlinear operators. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1979, 16, 964–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, P. A modified forward-backward splitting method for maximal monotone mappings. SIAM J. Control Optim. 2000, 38, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.S. A class of projection and contraction methods for monotone variational inequalities. Appl. Math. Optim. 1997, 35, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, Y. Proximal algorithm for solving monotone variational inclusion. Optimization 2018, 67, 1197–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hieu, D.V.; Anh, P.K.; Ha, N.H. Regularization proximal method for monotone variational inclusions. Netw. Spat. Econ. 2021, 21, 905–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Bazighifan, O. Modified inertial subgradient extragradient method with regularization for variational inequality and null point problems. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudafi, A.; Oliny, M. Convergence of a splitting inertial proximal method for monotone operators. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2003, 155, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yuan, M.; Jiang, B. Multi-step inertial hybrid and shrinking Tseng’s algorithm with Meir-Keeler contractions for variational inclusion problems. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholamjiak, P.; Hieu, D.V.; Muu, L.D. Inertial splitting methods without prior constants for solving variational inclusions of two operators. Bull. Iran. Math. Soc. 2022, 48, 3019–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Long, X.; Lei, Z.; Chen, Z. New self-adaptive methods with double inertial steps for solving splitting monotone variational inclusion problems with applications. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2022, 2022, 106656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Wang, Y.; Yao, J.C. Multi-step inertial regularized methods for hierarchical variational inequality problems involving generalized Lipschitzian mappings. Mathematics 2021, 9, 2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Pan, C. The iterative solutions of split common fixed point problem for asymptotically nonexpansive mappings in Banach spaces. Fixed Point Theory Appl. 2020, 2020, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.S. The Mann and Ishikawa iterative approximation of solutions to variational inclusions with accretive type mappings. Comput. Math. Appl. 1999, 37, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottle, R.W.; Yao, J.C. Pseudo-monotone complementarity problems in Hilbert space. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 1992, 75, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).