Abstract

We make use of generalized iterations of the Sacks forcing to define cardinal-preserving generic extensions of the constructible universe L in which the axioms of ZF hold and in addition either (1) the parameter-free countable axiom of choice fails, or (2) holds but the full countable axiom of choice fails in the domain of reals. In another generic extension of L, we define a set , which is a model of the parameter-free part of the 2nd order Peano arithmetic , in which (Comprehension for formulas with parameters) holds, yet an instance of Comprehension for a more complex formula fails. Treating the iterated Sacks forcing as a class forcing over , we infer the following consistency results as corollaries. If the 2nd order Peano arithmetic is formally consistent then so are the theories: (1) , (2) , (3) .

MSC:

03E15; 03E35

1. Introduction

In this paper, we let be the second-order Peano arithmetic without the schema of (countable) Choice. Discussing the structure and deductive properties of , one of founders of modern proof theory Georg Kreisel ([1], § III, page 366) wrote that the selection of subsystems “is a central problem”. In particular, Kreisel notes, that

[…] if one is convinced of the significance of something like a given axiom schema, it is natural to study details, such as the effect of parameters.

Recall that parameters in this context are free variables in various axiom schemata in , , , and other similar theories. Thus the most obvious way to study “the effect of parameters” is to compare the strength of a given axiom schema S with its parameter-free subschema . (The asterisk will refer to the parameter-free subschema in this paper).

Some research in this direction was accomplished in the early years of modern set theory. In particular Levy [2] proved that the generic collapse of cardinals below (called the Levy collapse, see Solovay [3]) results in a generic extension of in which fails, where is the parameter-free subschema of the (countable) Choice schema in the language of . This result by Levy implies the formal consistency of .

Later Guzicki [4] established that the Levy-style generic collapse below results in a generic extension of in which (in the language of ) fails, but the parameter-free subschema holds, so that is strictly weaker than , or saying it differently, is consistent. (This can be compared with an opposite result for the dependent choice schema , in the language of , which happens to be equivalent to its parameter-free subschema by a simple argument given for instance in [4]).

We may note that the Levy and Guzicki results above involve uncountable cardinals up to (Levy) and (Guzicki), so that the consequent consistency results are based on set theoretic tools far beyond the axiomatic system itself. This discrepancy motivated us to conduct this research, aimed at cardinal-preserving constructions of models with the same properties, with the final goal to obtain the consistency results as above on the basis of the consistency of alone.

Outside of the domain of , some results related to parameter-free versions of the Separation and Replacement axiom schemata in also are known from [5,6,7]. This gives us an additional motivation to include the Comprehension schema in our study, which is a direct counterpart of the Separation and Replacement schemata.

To conclude, our paper is devoted to further clarification of the role of parameters in the Choice and and Comprehension schemata and in . The main integrated result is that the parameter-free versions of both and are strictly weaker than the full versions of the schemata (Theorems 1 and 2 below), but still the parameter-free version of is not provable in (Theorem 3). Special attention will be paid to the evaluation of those proof theoretic tools used in the arguments. That is, we show that the formal consistency of suffices. This is the main contribution of this paper. It has a crucial advantage comparably to the above-mentioned earlier results and approaches by Levy [2] and Guzicki [4], which involve cardinal-collapse forcing notions and thereby definitely cannot be rendered on the basis of the consistency of .

The following Theorems 1–3 are the main results of this paper.

Theorem 1.

In , let be the constructible universe. Then:

- (i)

- There is a cardinal-preserving generic extension of in which (that is, for ordinal-definable relations) holds, but the full fails in the domain of reals.

- (ii)

- If is consistent then does not prove .

Theorem 1 is entirely new. Part (i) greatly surpasses the above-mentioned result of Guzicki [4] by the requirement of cardinal-preservation. This is a conditio sine qua non for Claim (ii) to be obtained by a similar technique, because the involvement of uncountable cardinals in the arguments, as in [4], is definitely beyond the formal consistency of .

In the next theorem, is the subtheory of in which the full schema is replaced by its parameter-free version , and the Induction principle is formulated as a schema rather than one sentence.

Theorem 2.

In , let be the constructible universe. Then:

- (i)

- There is a cardinal-preserving generic extension of , and a set in this extension, such that and M models .

- (ii)

- If is consistent then does not prove .

This is a new result as well, appeared in our recent ArXiv preprint [8].

The next theorem, albeit not entirely new in part (i), is added in for good measure, because its proof involves basically the same type of generic extensions.

Theorem 3.

In , let be the constructible universe. Then:

- (i)

- There is a cardinal-preserving generic extension of in which fails.

- (ii)

- If is consistent then does not prove .

Part (i) of this theorem essentially follows from a result by Enayat [9], where it is shown that using the finite-support infinite product of Jensen’s minimal--real forcing [10] results in a permutation model of with an infinite Dedekind-finite set of reals, and the existence of such a set implies the refutation of . Part (ii) is new.

The first claims of all three theorems will be established by means of a complex iteration of the Sacks forcing which resembles the generalized iteration by Groszek and Jech [11], but is carried out in a pure geometric way that avoids any formalism of forcing iterations. We call this technique arboreal Sacks iterations. The associated coding by degrees of constructibility is also involved, more or less along the lines discussed in ([12], p. 143).

To conclude, the main novelty of all three theorems is that the unified forcing technique of arboreal Sacks iterations is used to define generic cardinal-preserving models of set theory and second-order Peano arithmetic with different effects related to parameters in the Choice and Comprehension schemata in , to subsequently prove that the parameter-free versions of the schemata are weaker than the full versions. This leads to further development of the research line outlined by Georg Kreisel [1], see a quote above. The other principal novelty is that we demonstrate, by claims (ii) of all three theorems, that the ensuing consistency results can be obtained on the basis of the consistency of alone, rather than on the basis of full-scale set theoretic forcing technique. Claims (i) of Theorems 1 and 2 are new as they stand; claim (i) of Theorem 3 is a corollary of a known result.

It remains to note that topics in subsystems of second order arithmetic remain of big interest in modern studies, see e.g., [13,14,15], and our paper contributes to this research line.

The paper is organized as follows. After a short review of preliminaries in Section 2, we take some space to briefly describe the aforementioned cardinal-collapse models by Levy [2] and Guzicki [4] in Section 3 and Section 4.

Our basic forcing notion is introduced in Section 5; it consists of iterated perfect sets. The structure of -generic extensions of is studied in Section 6 and Section 7. In particular, Theorem 4 provides the cardinal preservation, and Theorem 5 presents several important results on the degrees of constructibility of reals and the relation of true -successor in the generic extensions considered.

The proof of Theorem 3(i) is carried out in Section 8 modulo an important lemma (Lemma 11) established in Section 9. Basically, a generic extension that proves Theorem 3(i) will be obtained as a certain subextension of a -generic extension , which is the content of Theorem 6.

Claims (i) of Theorems 1 and 2 are established in Section 10 and Section 11, via certain other subextensions of a -generic extension, studied by Theorems 7 and 8 respectively.

Finally Section 12 contains the proof of claims (ii) of all three theorems. To accomplish this proof, we will redo the proofs of claims (i) of all three theorems in some uniform manner. This will involve a rather well-known Theorem 9 on the equiconsistency of and the set theory without the Power Set axiom.

The paper ends with a usual conclusion-style material in Section 13.

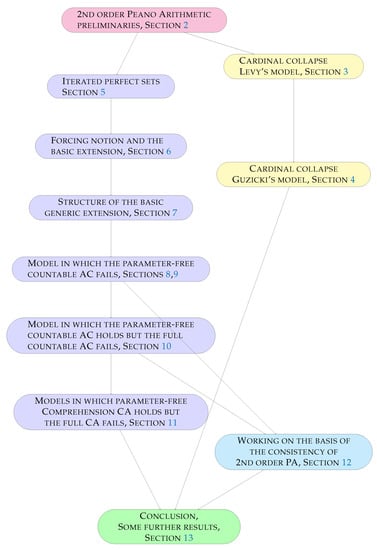

A flowchart follows on page 4, Figure 1 for the convenience of the reader.

Figure 1.

Flowchart.

2. Second Order Peano Arithmetic Preliminaries

Following [1,16,17] we consider the second order Peano arithmetic as a theory in the language with two sorts of variables—for natural numbers and for sets of them. We use for variables over and for variables over , reserving capital letters for subsets of and other sets. The axioms are as follows in (1)–(4):

- (1)

- Peano’s axioms for numbers.

- (2)

- The Induction schema: , for every formula in , and in we allow parameters, i.e., free variables other than k. (We do not formulate Induction as one sentence here because the Comprehension schema will not be assumed in full generality in Section 11).

- (3)

- Extensionality for sets of natural numbers.

- (4)

- The Comprehension schema : , for every formula in which x does not occur, and in we allow parameters.

is also known as (see e.g., an early survey [16]), as (see e.g., Simpson [17] and Friedman [18]), as (in [19] or elsewhere). Note that the schema of Choice (see below) is not included in .

The following schemata are not assumed to be parts of , yet they are often considered in the context of and in connection with .

- The Schema of Choice :

- , for every formula , where we allow parameters in , and , as usual.

We use instead of AC, more common in studies, because AC is the general axiom of choice in the context.

- Dependent Choices DC:

- , for every formula , and in we allow parameters.

We let be the parameter-free sub-schema of (that is, contains no free variables other than k). We define the parameter-free sub-schema the same way. The parameter-free sub-schema can be defined as well, but this does not make much sense because is known to be equivalent to by a simple argument, see e.g., [4].

In set-theoretic setting, and can be considered in the assumption that is a set-theoretic binary relation on , whose type can be restricted in this or another way depending on the context. In particular, assumes that is an (ordinal-definable) relation. (See [20] on ordinal definability). In addition, say or means the restriction to the type of lightface (parameter-free) or resp. boldface (with parameters in allowed) formulas.

3. A Cardinal-Collapse Model Where the Parameter-Free Fails

Here we recall an old model by Levy [2] in which the parameter-free fails for a certain (lightface) relation. This is basically any model of . To obtain this model, Levy makes use of the collapse below , i.e., a Cohen-style generic sequence of (generic) collapse maps is adjoined to the Gödel-constructible universe . Consider the set and the class of all sets hereditarily F-ordinal-definable in . Then N is a model of .

We may note that the set of all reals in N is equal to the set .

To prove that fails under , Levy considers the relation , and f codes a well-ordering of length .

Then, first, fails for R under by obvious reasons, and second, R can be presented as a lightface relation.

To prove the second claim, we may note, following Levy, that is equivalent to the following relation:

, f codes a well-ordering, whose length we denote by , and, for every countable transitive set X which models minus the Power Set axiom, if then it is true in that “there are at least infinite cardinals ”.

To see that is a relation, Levy uses well-founded relations on as a substitution for countable transitive sets. Since the well-foundedness is a property, the definition of can be converted to a form.

From a more modern perspective, we may note that is a relation, where is the transitive set of all hereditarily countable sets, and then make use of the conversion theorem (see e.g., Theorem 25.25 in [20]) saying that relations on the reals are the same as relations.

4. A Cardinal-Collapse Model Where the Parameter-Free Holds but the Full Fails

The Guzicki model with such an effect appeared in [4]. It is similar to Levy’s model of [2], yet it makes use of the Levy collapse below . To obtain such a model, we adjoin, to the Gödel constructible universe , a Cohen-style (finite-support) generic sequence of (generic) collapsing maps . Consider the set and the class N of all sets hereditarily F-real-ordinal definable in . Then N is a model of .

The set of all reals in N is equal to .

To check that fails in N for a relation, let code a strictly increasing map whose range is cofinal in . Accordingly the sequence of cardinals is cofinal in . This allows to accomodate the arguments in Section 3, with minor changes mutatis mutandis, and prove that fails in N for a relation similar to R but defined with p as a parameter.

To see that the parameter-free , and even for all ordinal-definable relations holds in N, let be an ∈-formula with an ordinal as the only parameter. Assume that holds in N. Then for every k there exist ordinals such that a set satisfying in N exists in . Let be the least such an ordinal. The sequence immediately belongs to . Yet using the homogeneous character of the product collapse forcing that yields f, one can prove that in fact the sequence in fact belongs to . Therefore , and accordingly for any k there is a set satisfying in N. It remains to note that .

5. Iterated Perfect Sets

Here we begin the proof of Theorems 1–3. The proof involves the engine of generalized iterated Sacks forcing developed in [21,22] on the base of earlier papers [11,23,24] and others. We consider the constructible universe as the ground model.

Arguing in in this section, we define, in , the set

of all non-empty tuples , , of ordinals , partially ordered by the extension ⊂ of tuples. is a tree without the minimal node (the empty tuple), which we exclude.

Our plan is to define a generic extension of by an array of reals , in which the structure of “sacksness” is determined by this set , so that in particular each is Sacks-generic over the submodel . Then Theorems 1–3 will be obtained via submodels of the basic model .

Let be the set of all countable and finite initial segments (in the sense of ⊂) . If then is the set of all initial segments of .

Greek letters will denote sets in .

Characters are used to denote elements of .

For any we consider initial segments and and defined analogously.

We consider as identical to so that both and for are homeomorphic Polich compact spaces. Points of will be called reals.

Assume that . If then let denote the usual restriction. If then let . To save space, let mean , mean , etc.

But if then we put .

To describe the idea behind the definition of iterated perfect sets, recall that the Sacks forcing consists of perfect subsets of , that is, sets of the form , where is a homeomorphism.

To obtain a product Sacks model, with two factors (the case of a two-element unordered set as the length of iteration), we have to consider sets of the form where H is any homeomorphism defined on so that it splits in obvious way into a pair of one-dimensional homeomorphisms.

To obtain an iterated Sacks model, with two stages of iteration (the case of a two-element ordered set as the length of iteration), we have to consider sets of the form , where H is any homeomorphism defined on such that if and then .

The combined product/iteration case results in the following definition.

Definition 1

(iterated perfect sets, [21,22]). For any is the collection of all sets such that there is a homeomorphism satisfying

for all and , . Homeomorphisms H satisfying this requirement will be called projection–keeping. In other words, sets in are images of via projection–keeping homeomorphisms.

We put .

Remark 1.

Note that ⌀, the empty set, formally belongs to Ξ, and then , and we easily see that is the only set in .

For the convenience of the reader, we now present five lemmas on sets in established in [21,22].

Lemma 1

(Proposition 4 in [22]). Let . Every set is closed and satisfies the following properties:

- 1.

- If and then is a perfect set in .

- 2.

- If , and a set is open in X (in the relative topology) then the projection is open in . In other words, the projection from X to is an open map.

- 3.

- If , , , and then .

Proof (sketch).

Clearly satisfies P-1, P-2, P-3, and one easily shows that projection–keeping homeomorphisms preserve the requirements. □

Lemma 2

(Lemma 5 in [22]). Suppose that , , , is any set, and . Then .

Lemma 3

(Lemma 6 in [22]). If , , , then .

Lemma 4

(Lemma 8 in [22]). If , , a set is open in X, and then there is a set , clopen in X and containing .

Lemma 5

(Lemma 9 in [22]). Suppose that , , , and . Then belongs to .

In particular , since obviously .

Corollary 1.

Assume that , , , , and . Then .

Proof.

The bigger set belongs to by Lemma 5. In addition, by Lemma 2 (with , ). It follows that , because . We conclude that by Lemma 5. Finally, we have by construction. □

Corollary 2.

Assume that are pairwise disjoint, , and for each k. Then the set belongs to , and for all k.

Proof.

For each k, there exists a projection–keeping homeomorphism . Define by for all k. Then H is projection–keeping and . □

Still arguing in , we let be the group of all permutations of the index set , i.e. all bijections such that . Any such a permutation induces a transformation acting on several types of objects as follows.

- If , or generally , then .

- If and then is defined by for all . That is, formally , the superposition.

- If and then .

- If then .

The following lemma is obvious.

Lemma 6.

If then .

Moreover π is an order preserving automorphism of .

6. The Forcing Notion and the Basic Extension

This section introduces the forcing notion we consider and the according generic extension called the basic extension.

We continue to argue in . Recall that a partially ordered set is defined in Section 5, and is the set of all at most countable initial segments in . For any let .

The set will be the forcing notion.

To define the order, we put whenever . Now we set (i.e. X is stronger than Y) if and only if and .

Remark 2.

We may note that the set as in Remark 1 belongs to and is the -largest (i.e., the weakest) element of .

Now let be a -generic set (filter) over .

Remark 3.

If in then X is not even a closed set in in . However we can transform it to a perfect set in by the closure operation. Indeed the topological closure of such a set X in taken in belongs to from the point of view of .

It easily follows from Lemma 4 that there exists a unique array , all being elements of , such that whenever and . Then is a -generic extension of , which we call the basic extension.

For the sake of convenience, let .

Theorem 4

(Thm 24 in both [21,22]). Every cardinal in remains a cardinal in . Every is Sacks generic over the model .

Proof (idea).

The forcing has the following property in , common with the ordinary one-step Sacks forcing:

- (∗)

- if sets are open dense in , and , then there is a stronger condition , , and finite sets pre-dense in below Y, in the sense that any stronger , , is compatible with some .

This property, established in [21,22] by means of a splitting/fusion technique, easily implies the preservation of all -cardinals in -generic extensions of . □

Here follow several lemmas on reals in -generic models , established in [21]. In the lemmas, we let be a set -generic over .

Lemma 7

(Lemma 22 in [21]). Suppose that sets satisfy . Then .

Lemma 8

(Lemma 26 in [21]). Suppose that is an initial segment in , and . Then .

Lemma 9

(Corollary 27 in [21]). If then and even .

Lemma 10

(Lemma 29 in [21]). If is an initial segment of , and , then either or for some .

7. Structure of the Basic Extension

We apply the lemmas above in the proof of the next theorem. Let denote the Gödel well-ordering on so that if and only if . Let mean that but , and mean that and .

Say that y is a true-successor of x (where ) if and only if and any real satisfies .

Theorem 5.

Let be a set -generic over , and . Then we have the following:

- (i)

- if and then

- (ii)

- if and then

- (iii)

- if and then or for some ,

- (iv)

- if , , then is a true -successor of

- (v)

- if , and is a true -successor of , then there is such that

- (vi)

- if , then is a true -successor of

- (vii)

- if is a true -successor of , then there is such that

Proof.

(i) Apply Lemma 7 with and .

(ii) Apply Lemma 8 with .

(iii) If there are elements , , such that , then let be the largest such one. Let (a finite initial segment of ). By Lemma 10, either , or there is such that . In the “either” case, we have by (i), so that by the choice of . In the “or” case we have , hence by (ii). However, this contradicts the choice of and .

Finally if there is no , , such that , then the same argument with gives .

(iv) The relation is implied by Lemmas 7 and 8. If now then or for some by (iii), and in the latter case in fact , hence , and then .

(v) As , by Lemma 10 there is such that and . If strictly then by the true -successor property, hence by (ii), contrary to the choice of . Therefore in fact . Then we have still by the true -successor property and (i), (ii). This implies for some , because if say then is strictly between and , contrary to the true -successor property.

(vi) Similar to (iv). Recall that . This implies . On the other hand, holds by Lemma 8 with . If now then or for some by (iii), and in the latter case in fact , hence then , contrary to the choice of z.

(vii) As , by Lemma 10 (with ) there is such that . If strictly then by the true -successor property, hence , contrary to Lemma 8 with . Therefore in fact . This implies for some , because if, say, then is strictly between and , contrary to the true -successor property. □

Now consider the following formula:

is a tuple of reals such that and each () is a true -successor of .

Thus separates tuples of true successor iterations, of length n.

Remark 4.

is a relation, absolute for any transitive model of containing the true , and component-wise -invariant in the argument . Indeed to see that is note that ‘being a true -successor’ is by direct estimation. To see the absoluteness note that both ‘being a true -successor’ and are relativized to the lower -cone of the arguments. The invariance is obvious.

Corollary 3

(of Theorem 5). Let be a set -generic over .

- (i)

- If , , andthen holds in .

- (ii)

- Conversely if and holds in then there is such that component-wise, that is, , , , …, .

8. A Model in Which the Parameter-Free Fails

Here we prove Theorem 3(i). Let us fix a set , -generic over and consider the according -generic array and the -generic extension . The goal is to define a sub-extension of in which the parameter-free fails.

- Let be the set of all finite or -countable initial segments such that there is a number satisfying for all .

- Let be the set of all restrictions of the form , , of the generic array .

- Let be the class of all sets -ordinal-definable in . Thus iff x is definable in by a set-theoretic formula with parameters in .

Here is the class of all ordinals, as usual. See [20,25] on ordinal definability.

- Let be the class of all sets , hereditarily -ordinal-definable in , i.e., it is required that x itself, all elements of x, all elements of elements of x, etc., belong to the above defined class in .

The following theorem implies Theorem 3(i). Indeed the model is a cardinal-preserving extension of by Theorem 4.

Theorem 6.

If a set is -generic over then is a model of in which the parameter-free/ fails.

It follows that is a model of .

Proof.

That classes of the form model see [20], Chapter 13.

Note that if then via the initial segment , and hence as well. It follows by Corollary 3(i) that is true in , where . Our goal will be to show that the parameter-free formula , the right-hand side of , fails in , meaning that fails in for the formula .

Suppose to the contrary that there is satisfying . This obviously results in a sequence of tuples of reals satisfying , that is, and each () is a true -successor of .

By definition there is an -formula with free variables , a parameter of the form , where , and some ordinals as parameters—such that if and then is true in iff . (The case of several parameters of the form , , can be easily reduced to the case of one parameter).

As , there is a number such that for all . Fix this m and consider the tuple . By Corollary 3(ii), there is a tuple , such that component-wise, that is, for all .

Note that by the choice of m. There is a number such that still but the shorter tuple belongs to , and hence . Then by Corollary 3 the -degree is definable in by the next formula, in which .

To conclude, and the -degree is definable in by an -formula with and ordinals as parameters. But this contradicts Lemma 11 that follows in the next Section. The contradiction refutes the contrary assumption above.

We finally note that is a formula by Remark 4. □

9. The Non-Definability Lemma

Here we prove the following lemma.

Lemma 11.

If a set is -generic over , , and then the -degree cannot be defined in by an -formula with and ordinals as parameters.

Proof.

Suppose to the contrary that is a formula as indicated, and it holds in that . Then there is a “condition” such that

where is the -forcing relation over , and is the canonical -name for the generic filter G. Let , so that .

We argue in . Thus . See Section 5 on permutations of .

As are countable initial segments of , it does not take much effort to define, in , a permutation satisfying the following:

- (A)

- is the identity

- (B)

- , and if then .

Coming back to (2) above, we put , . Note that by Lemma 6, where . We claim that

To prove the claim, let be -generic over , and . We have to check that, in , .

The set is -generic over and obviously . It follows from (2) that in . Yet (since ), by (A), and finally by construction. Thus, indeed in , as required. This completes the proof of (3).

The next step is to establish

- (C)

- and are compatible in .

We check this claim arguing in , so that and , where . It follows from (A), (B) that the set satisfies , and in addition . Let . Then belongs to by Corollary 1. Thus , hence (C) holds. This implies (3) since is obvious.

10. A Model in Which the Parameter-Free Holds but the Full Fails

Here we prove Theorem 1(i). The model will be a modification of the model studied in Section 8. We still fix a set , -generic over and consider the -generic array and the -generic extension . We are going to define a sub-extension of in which the parameter-free holds but the full fails.

- Let be the set of all finite or -countable initial segments such that for any there is a number satisfying for all satisfying .

- Let be the set of all restrictions of the form , , of the generic array .

- Let be the class of all sets -ordinal-definable in . Thus if and only if x is definable in by a set-theoretic formula with sets in as parameters.

- Let be the class of all sets , hereditarily -ordinal-definable in .

The following theorem implies Theorem 1(i). Indeed it follows from Theorem 4 that the model is a cardinal-preserving extension of .

Theorem 7.

If a set is -generic over then is a model of in which the parameter-free/ holds, even (with ordinals as parameters) holds, but the full fails. It follows that is a model of .

Proof.

Let be the formula ‘’. (See the definition of in Section 7). Note the parameter in this formula. Similarly to the proof of Theorem 6, if then and . It still follows by Corollary 3(i) that is true in , where . Moreover, arguments similar to the proof of Theorem 6, which we leave for the reader, show that the formula , the right-hand side of , fails in . Thus (with real parameters) fails in .

It remains to prove that (with ordinals as parameters) holds in . Suppose towards the contrary that is an -formula with ordinals as parameters, such that fails for in . Thus there exists a condition satisfying

- (†)

- “it holds in that but ”.

Here is the -forcing relation over , and is the canonical -name for the generic filter G, as above.

As holds in , there is a sequence of reals , satisfying , . By definition, for any k there is a set such that (meaning that only and ordinals are admitted as parameters), and the sequence belongs to as well. Furthermore, as the forcing relation is definable in , there exist sequences of conditions (possibly ), and of sets , such that

Now, arguing in , we let , , and . Thus and all belong to . Clearly there exists a sequence of permutations (see Section 5), , such that the sets are pairwise disjoint and disjoint with .

Let , so that in by Lemma 6, where . Define ; . It follows by Corollary 2 that the set belongs to and , for all k.

On the other hand, the sets belong to (because so do ) and are pairwise disjoint (because so are the sets ). However is closed in under countable disjoint union, hence .

We still work in . Starting with (4) and arguing as in the proof of Lemma 11 (the proof of 3 on page 13), we deduce that, for all k,

and hence

because and .

Finally, if H is -generic then the class has a well-ordering, say , also -ordinal-definable in . See e.g., [20], Section 13, the class is identical to as in [20]. Therefore, if H is any -generic set over containing , then, arguing on the basis of (5), we can define in such that, for each k, is equal to the -least set in , satisfying . This proves that for any such H, and hence

But this contradicts (†) above since . □

11. Models in Which the Parameter-Free Holds but the Full Fails

Here we sketch a proof of Theorem 2(i). See a full proof in our recent ArXiv preprint [8]. Thus the goal is to define a set in a cardinal-preserving generic extension of , which is a model of (with the parameter-free Comprehension ) in which the full fails.

Following the arguments above, assume that is a set -generic over , define () and the array as above, and consider the set

Here , , .

Thus and . (Not necessarily .) We put

The next theorem implies Theorem 2(i) since it follows from Theorem 4 that the set belongs to a cardinal-preserving extension of .

Theorem 8.

If a set is -generic over then is a model of (with the parameter-free Comprehension )in which the full holds but the full fails.

Proof (sketch, see [8] for a full proof).

That is a model of (with parameters) follows by the Shoenfield absoluteness theorem, because is Gödel-closed downwards by construction. That the parameter-free holds in follows by the ordinary permutation technique by a method rather similar to the verification of in the proof of Theorem 7 above.

Finally, fails to satisfy the full . Indeed the reals () do not belong to , since by construction. On the other hand, each is analytically definable in as the set containing the numbers such that the structure of true -successors above has a split at -th level, and possibly containing or not containing 0. Note the role of as a parameter in this definition of in . The ensuing definability formula for is by direct estimation, because it is based on the definability of the relation of ‘being a true -successor’. □

Another model of , in which fails even in the most elementary form of the nonexistence of complements of some its members, is also presented in [8]. It has the form , where is a Cohen-generic sequence over . Note that the complements are not adjoined to M, so that is violated in M even in the form , with as a parameter. On the other hand, the parameter-free holds in M by ordinary permutation arguments.

12. Working on the Basis of the Consistency of

This section is devoted to claims (ii) of our main Theorems 1–3. We recall that the consistency of is a common assumption in claims (ii). As the proofs of claims (i) of the theorems, given above, contain a heavy dose of the forcing technique, first of all we have to adequately replace with a more -like, forcing-friendly theory. This will be , a subtheory of obtained as follows:

- (a)

- the Power Set axiom PS is excluded;

- (b)

- the Axiom of Choice AC is replaced with the well-orderability axiom WA saying that every set can be well-ordered;

- (c)

- the Replacement schema, which is not sufficiently strong in the absence of PS, is replaced with the Collection schema;

See, e.g., [26] for a comprehensive account of main features of .

Two more principles are considered in the context of namely

- :

- every set is finite or countable,

- :

- every set is Gödel-constructible, i.e., the axiom of constructibility.

Theorem 9.

Theories and are equiconsistent. In fact they are interpretable in each other.

Proof.

This has been a well-known fact since while ago, see e.g., Theorem 5.25 in [16]. A more natural way of proof is as follows.

Firstly the theory (i.e., without WA and Collection) is interpreted in by the tree interpretation described e.g., in [16], § 5, especially Theorem 5.11, or in [17], Definition VII.3.10 ff. Kreisel [1], VI(a)(ii), attributed this interpretation to the category of “crude” results. Secondly the whole theory is interpeted in by means of the same tree interpretation, but restricted to only those trees that define sets constructible below the first gap ordinal, see a rather self-contained proof in [27]. This second part belongs to the category of “delicate” results of Kreisel [1], VI(b)(ii). □

Theorem 9 allows us to replace the consistency of in claims (ii) of our Theorems 1–3 by the equivalent consistency of , which is a much more forcing-friendly theory.

This makes it possible to argue in the frameworks of in the following proof of Theorem 3(ii). The proof is an adaptation of the proof of the statement (i) of the same Theorem 3, on the basis of .

Proof of Claims (ii) of Theorems 1–3.

We argue on the basis of . In other words, all sets are countable and constructible, so that the ground universe behaves like in many ways. Yet, to avoid unnecessary misunderstanding, we accept the following.

Definition 2.

The ground universe of is denoted by . Accordingly will be the collection (a proper -class) of all ordinals in .

Emulating the construction in Section 5, we define proper classes and , and sets , , , etc., similar to Section 5. But coming to Definition 1, we face a problem. Indeed, each space and any homeomorphism is now a proper class, hence as by Definition 1 is a class of proper classes, which cannot be considered. Therefore we have to parametrize homeomorphisms by sets.

Definition 3.

( form of Definition 1).

Arguing in , let . Define

this is a countable dense subset of in .

Let be any map (a set in ). Let be its extension defined on by whenever the limit exists, so is a continuous map defined on , a topologically closed “subset” or rather subclass of (also a proper class).

We define to be the class of all maps such that , is and is a projection–keeping homeomorphism.

Finally if then let .

Then and are proper classes, of course.

It is quite obvious that in the setting coincides with the collection of all sets , . This allows us to use the map as a parametrization of in , so that is the set of codes for the and each particular is the set of codes for . We will use as a forcing notion, that is, put , with the order if and only if in the sense of Section 5.

Note that both (∗) and the order are definable proper classes in .

Conditions should be informally identified with corresponding objects (parametrically defined proper classes) .

The property (∗) in the proof of Theorem 4 transforms to the following property of the forcing has a property in :

- (∗−)

- if a parametrized sequence of classes is such that each is open dense in , and , then there is a stronger condition , , and finite sets pre-dense in below Y.

In other words, is a pretame forcing notion in in the sense of [28] or [29].

It follows (see e.g., [29]) that any -generic extension of is still a model of , and the forcing and definability theorems hold similar to the case of usual set-size forcing. Furthermore all constructions and arguments involved in the proofs of Theorems 6–8 above (i.e., claims (i) of Theorems 1–3), as well as the results of [21,22] cited in the course of the proofs, can be reproduced mutatis mutandis on the basis of the theory . In particular, Theorem 6 takes the form asserting that the -part of a certain subextension of any -generic extension of satisfies .

Metamathematically, this means that the formal consistency of implies the consistency of . However the consistency of is equivalent to the consistency of by Theorem 9. This concludes the proof of Claim (ii) of Theorem 3.

Pretty similarly, Theorems 7 and 8 take appropriate forms sufficient to infer the consistency of resp.

13. Conclusions, Remarks, and Problems

In this study, the method of generalized arboreal iterations of the Sacks forcing is employed to the problem of obtaining cardinal-preserving models of , and models of and the second-order Peano arithmetic , in which the parameter-free version of the Comprehension or Choice schema holds but the full schema fails. These results (Theorems 1–3 above) contribute to the ongoing study of both subsistems and extensions of as in [13,14,15,17,30,31] among many others, as well as to modern studies of forcing extensions in class theories and -like theories as in [26,32,33,34].

From our study, it is concluded that the technique of generalized arboreal iterations of the Sacks forcing succeeds to solve important problems in descriptive set theory and second-order Peano arithmetic related to parameter-free versions of such crucial axiom schemata as Comprehension and Choice, by our Theorems 1–3.

From the results of this paper, the following remarks and problems arise.

Remark 5.

Identifying the theories with their deductive closures, we may present the concluding statements of Theorems 1–3 as resp.

Studies on subsystems of have discovered many cases in which holds for a given pair of subsystems , see e.g., [17]. And it is a rather typical case that such a strict extension is established by demonstrating that proves the consistency of S. One may ask whether this is the case for the results in (6). The answer is in the negative: namely

by a result in [18], also mentioned in [19]. This equiconsistency result also follows from a somewhat sharper theorem in [35], 1.5.

Remark 6.

There is another meaningful submodel of the basic model . Namely, consider the set of all finite or countablewell-foundedinitial segments , , instead of the sets W (as in Section 8) and (as in Section 10). Define a corresponding submodel accordingly. Then holds in but fails. Yet a better model is defined in [31], in which holds but even (the best possible in this case) fails.

Remark 7.

It will be interesting to study problems considered in this paper in the frameworks of non-ZF-oriented set theories like Quine’s New FoundationsNF[36], various non-well-founded and anti-foundational theories (see [37]), or (as suggested by one of the anonymous reviewers) the ideal set theory or the ideal calculus as in [38]—which is essentially a nave set or class theory with a rather vague axiomatic. Yet it seems to us that those theories haven’t so far developed an adequate instrumentarium to study and answer such sort of questions.

We proceed with a list of open problems.

Problem 1.

Is the parameter-free countable choice schema in the language true in the models defined in Section 11?

We expect that fails in the first model in Section 11 via the relation codes k-incomparable reals minimal over , and it’s a separate problem how to modify this model to allow .

Problem 2.

Can we sharpen the result of Theorem 8 by specifying that , rather than , is violated? The combination plus over would be optimal for Theorem 2. Can we similarly sharpen the result of Theorems 6 and 7 by specifying that , resp., are violated?

As conjectured by V. Gitman, Jensen’s iterated forcing may lead to the solution of Problem 2 by methods outlined in [31]. Such a construction makes use of the consecutive “jensenness”, known to be a relation, instead of the consecutive “sacksness”, which can help to define the counterexamples required at minimally possible levels.

Problem 3.

As a generalization of Problem 2, prove that, for any , does not imply . In this case, it would be possible to conclude that the full schema is not finitely axiomatizable over . There are similar questions related to Theorems 6 and 7, of course. Compare to Problem 9 in ([16], § 11).

We expect that methods of inductive construction of forcing notions in that are similar to the iterated Jensen forcing as in [31] but carry hidden automorphisms, recently developed in our papers [39,40,41,42,43], may lead to the solution of Problem 3.

Problem 4

(Communicated by Ali Enayat). A natural question is whether the results of this note also hold for second order set theory (the Kelley–Morse theory of classes), with suitable reformulations of the Choice and Comprehension schemata.

This may involve a generalization of the Sacks forcing to uncountable cardinals, as e.g., in Kanamori [44], as well as the new models of set theory recently defined by Fuchs [45], on the basis of further development of the methods of class forcing introduced by S. D. Friedman [28].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.K. and V.L.; methodology, V.K. and V.L.; validation, V.K.; formal analysis, V.K. and V.L.; investigation, V.K. and V.L.; writing original draft preparation, V.K.; writing review and editing, V.K. and V.L.; project administration, V.L.; funding acquisition, V.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially supported by Russian Foundation for Basic Research RFBR grant number 20-01-00670.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable. The study did not report any data.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their thorough reviews, and highly appreciate the comments and suggestions, which significantly contributed to improving the quality of the manuscript. We would like to thank Ali Enayat, Gunter Fuchs, Victoria Gitman, and Kameryn Williams, for their enlightening comments that made it possible to accomplish this research, and separately Ali Enayat for references to [18,19,35] in matters of Theorem 3.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kreisel, G. A survey of proof theory. J. Symb. Log. 1968, 33, 321–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, A. Definability in axiomatic set theory II. In Mathematical Logic and Foundations of Set Theory, Proceedings of the International Colloquium, Jerusalem, Israel, 11–14 November 1968; Bar-Hillel, Y., Ed.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; London, UK, 1970; pp. 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovay, R.M. A model of set-theory in which every set of reals is Lebesgue measurable. Ann. Math. 1970, 92, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzicki, W. On weaker forms of choice in second order arithmetic. Fundam. Math. 1976, 93, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrada, M. Parameters in theories of classes. Stud. Log. Found. Math. 1978, 99, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, A. Parameters in comprehension axiom schemes of set theory. Proc. Tarski Symp. internat. Symp. Honor Alfred Tarski Berkeley 1971 Proc. Symp. Pure Math. 1974, 25, 309–324. [Google Scholar]

- Schindler, S.; Schlicht, P. ZFC without Parameters (A Note on a Question of Kai Wehmeier). Available online: https://ivv5hpp.uni-muenster.de/u/rds/ZFC_without_parameters.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Kanovei, V.; Lyubetsky, V. The parameterfree Comprehension does not imply the full Comprehension in the 2nd order Peano arithmetic. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.07599. [Google Scholar]

- Enayat, A. On the Leibniz—Mycielski axiom in set theory. Fundam. Math. 2004, 181, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, R. Definable sets of minimal degree. In Mathematical Logic and Foundations of Set Theory, Proceedings of the International Colloquium, Jerusalem, Israel, 11–14 November 1968; Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics; Bar-Hillel, Y., Ed.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; London, UK, 1970; Volume 59, pp. 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groszek, M.; Jech, T. Generalized iteration of forcing. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 1991, 324, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathias, A.R.D. Surrealist landscape with figures (a survey of recent results in set theory). Period. Math. Hung. 1979, 10, 109–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frittaion, E. A note on fragments of uniform reflection in second order arithmetic. Bull. Symb. Log. 2022, 28, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturi, G.; Viale, M. Second order arithmetic as the model companion of set theory. Arch. Math. Logic 2023, 62, 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, K. A few more dissimilarities between second-order arithmetic and set theory. Arch. Math. Logic 2023, 62, 147–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apt, K.R.; Marek, W. Second order arithmetic and related topics. Ann. Math. Logic 1974, 6, 177–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, S.G. Subsystems of Second Order Arithmetic, 2nd ed.; Perspectives in Logic; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; ASL: Urbana, IL, USA, 2009; p. xvi + 444. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, H. On the necessary use of abstract set theory. Adv. Math. 1981, 41, 209–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, T. A disquotational theory of truth as strong as . J. Philos. Log. 2015, 44, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jech, T. Set Theory, The Third Millennium Revised and Expanded ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2003; p. xiii + 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovei, V. Non-Glimm-Effros equivalence relations at second projective level. Fund. Math. 1997, 154, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovei, V. On non-wellfounded iterations of the perfect set forcing. J. Symb. Log. 1999, 64, 551–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, J.E.; Laver, R. Iterated perfect-set forcing. Ann. Math. Logic 1979, 17, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groszek, M.J. Applications of iterated perfect set forcing. Ann. Pure Appl. Logic 1988, 39, 19–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myhill, J.; Scott, D. Ordinal definability. In Axiomatic Set Theory; Proceedings of Symposia in Pure Mathematics 13, Part I; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1971; pp. 271–278. [Google Scholar]

- Gitman, V.; Hamkins, J.D.; Johnstone, T.A. What is the theory ZFC without power set? Math. Log. Q. 2016, 62, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovei, V.G. Theory of Zermelo without power set axiom and the theory of Zermelo- Fraenkel without power set axiom are relatively consistent. Math. Notes 1981, 30, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.D. Fine structure and class forcing. In De Gruyter Series in Logic and Its Applications; de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2000; Volume 3, p. x + 221. [Google Scholar]

- Antos, C.; Gitman, V. Modern Class Forcing. In Research Trends in Contemporary Logic; Daghighi, A., Rezus, A., Pourmahdian, M., Gabbay, D., Fitting, M., Eds.; College Publications: London, UK, 2023; forthcoming; Available online: https://philpapers.org/go.pl?aid=ANTMCF (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Enayat, A.; Schmerl, J.H. The Barwise-Schlipf theorem. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 2021, 149, 413–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.D.; Gitman, V.; Kanovei, V. A model of second-order arithmetic satisfying AC but not DC. J. Math. Log. 2019, 19, 1850013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antos, C.; Friedman, S.D.; Gitman, V. Boolean-valued class forcing. Fundam. Math. 2021, 255, 231–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitman, V.; Hamkins, J.D.; Holy, P.; Schlicht, P.; Williams, K.J. The exact strength of the class forcing theorem. J. Symb. Log. 2020, 85, 869–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holy, P.; Krapf, R.; Lücke, P.; Njegomir, A.; Schlicht, P. Class forcing, the forcing theorem and Boolean completions. J. Symb. Log. 2016, 81, 1500–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmerl, J.H. Peano arithmetic and hyper-Ramsey logic. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 1986, 296, 481–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quine, W.V. New foundations for mathematical logic. Am. Math. Mon. 1937, 44, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, K. The Joy of Sets. Fundamentals of Contemporary Set Theory, 2nd ed.; Undergraduate Texts Math; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fraenkel, A.A.; Bar-Hillel, Y.; Levy, A. Foundations of Set Theory. With the Collab. of Dirk van Dalen, 2nd rev. ed. Reprint; Stud. Logic Found. Math.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1984; Volume 67. [Google Scholar]

- Kanovei, V.; Lyubetsky, V. Models of set theory in which nonconstructible reals first appear at a given projective level. Mathematics 2020, 8, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovei, V.; Lyubetsky, V. On the problem of Harvey Friedman. Mathematics 2020, 8, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovei, V.; Lyubetsky, V. Models of set theory in which separation theorem fails. Izv. Math. 2021, 85, 1181–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovei, V.; Lyubetsky, V. The full basis theorem does not imply analytic wellordering. Ann. Pure Appl. Logic 2021, 172, 102929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovei, V.; Lyubetsky, V. A model in which the Separation principle holds for a given effective projective Sigma-class. Axioms 2022, 11, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanamori, A. Perfect-set forcing for uncountable cardinals. Ann. Math. Logic 1980, 19, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, G. Blurry Definability. Mathematics 2022, 10, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).