Abstract

In this paper, we construct a new numerical algorithm for the partial differential equation of up-and-out put barrier options under the CEV model. In this method, we use the Crank-Nicolson scheme to discrete temporal variables and the cubic B-spline collocation method to discrete spatial variables. The method is stable and has second-order convergence for both time and space variables. The convergence analysis of the proposed method is discussed in detail. Finally, numerical examples verify the stability and accuracy of the method.

MSC:

65M06; 91G20

1. Introduction

With the further acceleration of economic globalization, the price turbulence in the financial market is becoming more and more serious, and various risks caused by it have become a hot issue concerned and studied by economists and investors. In recent years, the derivatives market has become increasingly important in the financial and investment fields. Options have become an important tool for companies and investors to hedge assets and investment portfolios to control the risks brought by stock price fluctuations. There are many types of options, such as European options, American options, Asian options, barrier options, exotic options, lookback options, etc. European options are options that one party of the call option must exercise on the expiration date of the option. American options and barrier options are path-dependent options, and the return of these two options depends on the volatility path of the underlying asset price, not just the asset price on the maturity date.

The famous Black-Scholes option pricing model was proposed by Fischer Black and Myron Scholes in 1973 [1]. This model assumes that the underlying asset price follows the geometric Brownian motion, i.e., its distribution is logarithmic normal, and when it focuses on option pricing under the premise that its volatility is constant, it can meet option pricing in most cases. Since the required preconditions are too strict, the conditions proposed by the Black-Scholes model do not conform to the reality. In 1975, Cox [2] first considered the characteristics of the relationship between the volatility of assets winning the bid in the market and their price level, and established the Constant Elasticity of Variance (CEV) model. Schroder’s [3] empirical research showed that the CEV model can more accurately describe the changes in the price of underlying assets. Therefore, applying the CEV model to option pricing can obtain a better solution.

The option pricing model used in this section is the CEV model. The stock price process satisfies:

where is a constant coefficient, , is expected rate of return, is standard Brownian motion.

The differential equation that the option price satisfies is

where is the value of options at the asset price S and at time t, T is the maturity date, is the volatility and r is the risk-free interest rate.

Barrier options are a kind of European option, and their final benefit depends not only on the price of the underlying asset on the expiration date of the option, but also on whether the price of the underlying asset reaches a certain level (barrier B) during the entire option validity period. When the price of the underlying asset reaches the barrier, the option terminates. This type of option is called a knock-out option. If the underlying price of the original asset is higher than the barrier, it is called a down knock-out barrier option; if the underlying price of the original asset is lower than the barrier, it is called an up knock-out barrier option. When the price of the underlying asset reaches the barrier period, the option becomes effective, and this type of option is called a knock-in option. Similarly, there are down knock-in options and up knock-in options. European options can be divided into call options and put options.

Let us consider the up-and-out put barrier options, the initial condition

and boundary conditions

where K is the exercise price.

Due to the fact that the initial condition is not smooth, the obtained solution is not smooth enough to perform the convergence of numerical approximations. We replace by a smooth function . We obtain

the initial condition

and boundary conditions

Using the transformation: . We obtain

with initial condition

and boundary conditions

where

Now, to solve the problem given in (9)–(12), we truncate the infinite domain into a finite domain , where is a sufficiently small negative real number. Then, we consider a general form of (9)–(12) on the truncated region :

where

with initial and boundary conditions

In order to ensure the existence of a unique solution of the above problem, we assume that [4]

There are numerous studies about the numerical methods of solving barrier options under the CEV model. For example, Thakoor et al. [5] provided a highly accurate and efficient numerical scheme for barrier options under CEV. In order to achieve the fourth order convergence, it is necessary to refine the grid at both the strike and barriers, and obtain oscillation-free hedging parameters; a full implicit time integration technique with extrapolation is employed. Ahmadian and Ballestra [6] developed a numerical method to price discrete barrier options based on an underlying described by the constant elasticity of variance model with jump-diffusion (CEVJD). This method is allowed to approximate differential terms and jump integral by means of two different numerical techniques. Dias [7] has developed two new methods for pricing and hedging European barrier option contracts under the Jump to Default Extended Constant Elasticity of Variance (JDCEV) model, i.e., the stopping time method based on the first passage time densities of the underlying asset price process through the barrier level, as well as a static hedging portfolio method in which the barrier option is replicated by a portfolio of plain-vanilla and binary options. Guo and Chang [8] proposed an accelerated static replication method for continuous European barrier options by using the repeated Richardson extrapolation technique for Romberg sequences.

The main motivation of this work is to develop a third-order numerical method for solving the CEV model given in (13)–(16). In this method, the Crank-Nicolson scheme is used to discrete the temporal variables, and the cubic B-spline configuration method is used to discrete the spatial variables. The stability of this method is analyzed. In addition, we prove that the proposed method is second order convergent in space and time. The theoretical results are verified by numerical experiments and the applicability of the method is illustrated. B-spline was originally proposed by Schoenherg [9] in 1946. B-spline has strong local control capabilities, as well as many advantages such as convexity preservation, convex hull, geometric invariance, and variability reduction. Nowadays, B-spline has become one of the most important numerical methods used to study and solve partial differential equations. For example, Shallu et al. [10] proposed an improved extrapolation collocation method based on cubic B-splines. The method is applied to a class of self adjoint singularly perturbed boundary value problems, with the equispaced discretization of the domain. Since the standard B-spline collocation method cannot achieve the optimal convergence order, the cubic B-spline interpolant and its higher-order derivatives are corrected later. The proposed technology can be applied to high-order linear, nonlinear problems, and partial differential equations. Shallu and V.K. Kukreja [11] obtained a numerical solution to the nonlinear modified Burgers equation using an improvised collocation technique with cubic B-spline as basis functions. In this method, the cubic B-spline is forced to satisfy interpolant conditions with some specific end conditions. Shallu and V.K. Kukreja [12] uses an improvised cubic B-spline collocation technique to solve the Benjamin-Bona-Mahony-Burgers (BBMB) equation due to the inability to achieve optimal accuracy and convergence order using the standard B-spline collocation method. Therefore, improvised cubic B-splines are formed by making a posteriori corrections to cubic B-spline interpolants and their higher-order derivatives. We note that numerical methods based on B-spline basis functions have been used to solve option pricing problems. For example, the authors of [13,14,15] used the B-spline basis function for solving the generalized Black Scholes equation.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, the time variable is discretized by the Crank-Nicolson format, and the convergence analysis is carried out. In the Section 3, we describe spatial discretization by the cubic B-spline collocation method, and discuss the stability and convergence analysis of this method. Numerical experiments are carried out in Section 4. The results will be discussed in Section 5.

2. Temporal Discretization

In order to solve the CEV model given in (13)–(16) more conveniently, we consider a uniform partition of the domain with node points , where and with and . We first discretize the problem (13)–(16) in the temporal direction.

2.1. Description of the Crank-Nicolson Method of Time Variable

2.2. Convergence Analysis

Next, we will conduct convergence analysis for the case of using the CN model discrete temporal variables.

The local truncation error of the temporal discretization method (17) is defined by

where is the approximate solution of the problem (17)–(20) obtained after one step of the semi-discrete scheme taking the exact value , instead of as the initial data, i.e.,

We define the global truncation error at time as

Lemma 1.

Let the operator be such that is the solution ‘u’ of:

Then

where denotes the range of the linear operator .

Proof.

(see, [16]). □

Lemma 2.

If

then there holds

where K is a constant independent of N.

Proof.

Because and v is a smooth function, hence by Taylor series expansion, we obtain

Using the above extension, we obtain

Using relations (13) and (21) gives

By relations (31) and (32), we obtain

Now, because

and on , we obtain

This means

It follows by (33) that

By using relation (24), we obtain

By directly application of Lemma 1, we obtain

In addition, we can decompose the global truncation error at time in the following form

By relations (17) and (24), we obtain

(34) and (35) gives the recurrence relation as

Here, we use the notation .

The operator ‘’ is defined by which is the solution of

Now, according to Gonzalez and Palencia (see, [17]) for the operator ‘’, where is a rational A-acceptable function (see, [18]), such that

Thus, we obtain

This imples that (30) follows. □

We can see that the discrete scheme is consistent by Lemma 2. Thus we obtain the following result with the help of Lax equivalence theorem (see, [19]) and Lemma 2.

3. Spatial Discretization

3.1. Description of Cubic B-Spline Method

First, we consider a uniform partition over the finite interval . Then we extend the uniform partition in order to construct the cubic B-spline for the partition , by adding four additional nodes .

Let be the approximation to the exact solution at the -th time level. Then, can be defined by

where are unknown parameters.

Following [20], we can obtain the representations of cubic B-splines with the required attributes:

Each basis function is twice continuously differentiable on the entire real line.

If we consider . Since one can easily see that the basis functions in are linearly independent on . Then is a finite dimensional linear sub-space of of dimension with basis .

By using (37), the values of basis functions , , at the grid points are listed in Table 1. By using (36) and Table 1, , and at the mesh points are obtained as

Table 1.

The values of basis functions , , at the grid points .

3.2. Formulation of Cubic B-Spline Collocation Method

In this part, we construct the cubic B-spline collocation method for the solution of the problem (17)–(20). Firstly, we write Equation (17) as:

where

the boundary conditions

Then, we force the function to satisfy Equations (41) and (43) at the node points , according to the cubic B-spline collocation technique. Thus, we have

Substituting the expressions for , and from Equations (38)–(40), respectively into Equation (44), we obtain a system of m + 1 equations in m + 1 unknowns

where

By using (45), we obtain

By using Equations (47)–(48), we eliminate , , and , such that

where

The system produced by Equations (49)–(51) can be expressed in matrix form as follows

where

with

and

where

One can easily see that for sufficiently large m, the matrix P is strictly diagonally dominant by rows. Hence P is invertible (see, [21]), and

We need obtain the initial vector to solve the system of matrix (52).

By solving the following interpolation problem can find the vector

where

Thus we obtain the following system of matrix

where

Now, since matrix A is diagonally dominant with strict diagonal dominance in all rows except the first row and the last row, it can be concluded from Gershgorin’s theorem (see [22]) that A is nonsingular. Therefore, the vector giving the initial vector can be uniquely found.

3.3. Stability Analysis

In this subsection, we use the Von-Neumann stability method to analyze the stability of the scheme defined by (52).

Theorem 2.

Proof.

We set to establish the stability result of method (52). We define as

where , is the time related parameter and the exponential term represents spatial correlation. Substituting Equation (53) into Equation (46), we obtain

Re-write above equation as

For the convenience of calculation, we introduce , and as

By reducing Equation (55), we obtain

Equation (56) means that

with

By taking the absolute value on both sides of Equation (57) we obtain

As and . This means

□

Thus, we can see that the scheme is unconditionally stable by Equation (59).

3.4. Convergence Analysis

Lemma 3.

Let set of all functions that reduces to cubic polynomials on each subintervals , , of then

and, there exists a unique cubic spline solving the interpolation problem-

where, is the solution of the discretized problem (41)–(43) at the time level n. The function ‘s’ is called the cubic spline interpolate to .

Proof.

(see, [23]). □

Theorem 3.

Proof.

In order to find error estimate, let be the unique spline interpolate from to the solution of the boundary value problem (41)–(43) at the nth-time level.

Here, (see, Lemma 3), is given by

The boundary value problem (41)–(43) can be rewritten as

where

If , , , lie in then , , . Therefore, according to Hall and Meyer error estimate (see, [24]), we can obtain

where, , , , . Since

Thus,

At the th-time level, we write

where is an error function which order of magnitude is and , are error functions which order of magnitude are .

Since ; , therefore we can re-write the system (70)–(72) in the following matrix form

where,

this implies

By using (52) and (73), we obtain

A simple use of Equation (74) and bound of derived in Section 3.2 gives

where .

In addition, with the help of Equations (71), (72) and (75), we obtain

Thus

Now,

By using given in Section 3.1, we can easily see that , , hence

□

Theorem 4.

Let be the solution of the initial boundary value problem (13)–(16) and be the collocation approximation to the solution after the temporal discretization stage. Then under the hypothesis of Lemma 2 and Theorem 3 the error estimate of the totally discrete scheme is given by

where K are positive constants.

4. Numerical Experiments

In this section, we mainly use RStudio version 4.2.0 to verify the feasibility of the obtained pricing model (52).

Consider the following issue of PDE of up-and-out put barrier options under the CEV model:

subject to the initial and boundary conditions

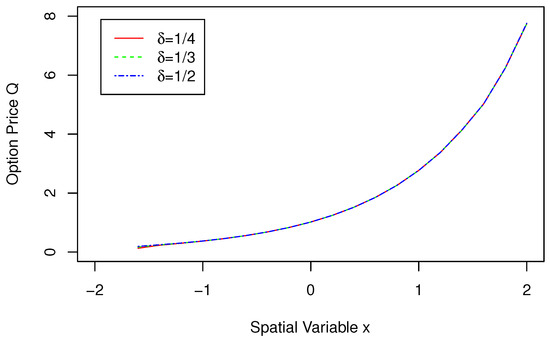

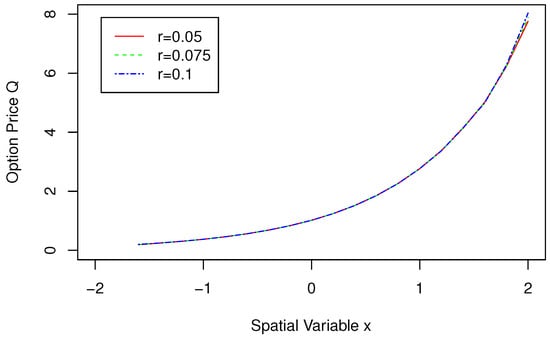

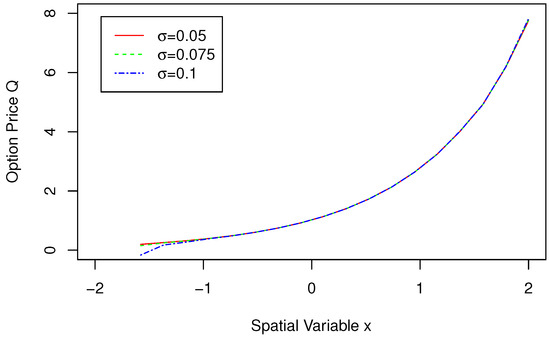

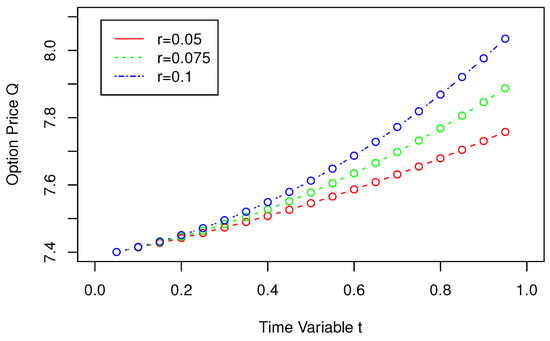

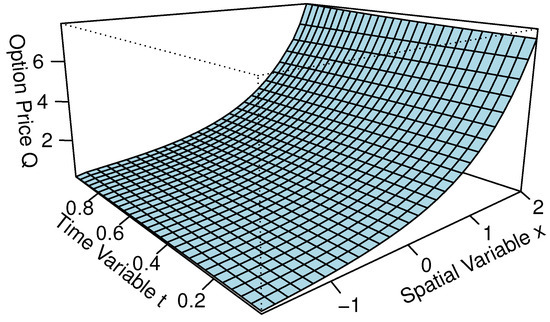

Figure 1 shows the change trend of Spatial Variable x and Option Price Q for when . When takes different values, it is noted that the changes in option prices are basically consistent, indicating that the obtained pricing model is feasible. Figure 2 shows the change trend of Spatial Variable x and Option Price Q for when . When the value of x approaches 2, the option price gradually increases as r increases, and the change trend of Spatial Variable x and Option Price Q is roughly the same in the rest of the time. Figure 3 shows the change trend of Spatial Variable x and Option Price Q for when . When the value of x is less than , the option price gradually increases as increases, and the change trend of Spatial Variable x and Option Price Q is roughly the same in the rest of the time. Overall, the option price gradually increases with the increase of spatial variable x, and the rate of growth also gradually increases. Figure 4 shows the change trend of Time Variable t and Option Price Q for when . The option price gradually increases as the time variable t increases. As can be seen from the figure, as r increases, the slope of the line gradually steepens, and the option price increases more quickly. When and , the surface plot of the approximate solution for is given in Figure 5.

Figure 1.

Approximate solutions with different values of and x in .

Figure 2.

Approximate solutions with different values of r and x in .

Figure 3.

Approximate solutions with different values of and x in .

Figure 4.

Approximate solutions with different values of r and t in .

Figure 5.

Approximate solution for .

Based on the studied option pricing model, in this section we considers the relationship between the time variable x and the spatial variable t and the option price, and select different parameters , r and . Based on the selected parameters, the trend chart of the option price was obtained, and the changes in the image were observed. The numerical simulation results were consistent with theoretical analysis.

5. Conclusions and Dicussion

In this paper, we study the cubic B-spline method for the barrier option problem under the CEV model. The time variable is discretized using the Crank-Nicolson method. On this basis, the spatial variable is discretized using the cubic B-spline collocation method to obtain a pricing model for barrier options. The time discretization of barrier options is analyzed for convergence, and the space discretization is analyzed for stability and convergence. The trend of log price of stock and option price for each parameter is analyzed in RStudio version 4.2.0, and the results show that cubic B-spline is feasible for solving barrier option problems under CEV models.

At present, there are still some shortcomings in this article. When truncating the infinite domain into the finite domain, some errors may occur. However, according to references [13,14,15], these errors are controllable. Thus, in the data experiment section, we make the error . Additionally, in this article, there is no comparison between the B-spline method used in this article and other methods for option pricing, which is also a limitation of this article.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, X.Y. and Q.H.; Writing—review & editing, Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Black, F.; Scholes, M. The pricing of options and corporate liabilities. J. Political Econ. 1973, 81, 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J. Notes on Option Pricing I: Constant Elasticity of Variance Diffusions; Unpublished Note; Stanford University, Graduate School of Business: Stanford, CA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Schroder, M. Computing the constant elasticity of variance option pricing formula. J. Financ. 1989, 44, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, A. Partial Differential Equations of Parabolic Type; Courier Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Thakoor, N.; Tangman, D.Y.; Bhuruth, M. Efficient and high accuracy pricing of barrier options under the CEV diffusion. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2014, 259, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian, D.; Ballestra, L.V. A numerical method to price discrete double Barrier options under a constant elasticity of variance model with jump diffusion. Int. J. Comput. Math. 2015, 92, 2310–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, J.C.; Nunes, J.P.V.; Ruas, J.P. Pricing and static hedging of European-style double barrier options under the jump to default extended CEV model. Quant. Financ. 2015, 15, 1995–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.H.; Chang, L.F. Repeated Richardson extrapolation and static hedging of barrier options under the CEV model. J. Futur. Mark. 2020, 40, 974–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenberg, I.J. Contributions to the problem of approximation of equidistant data by analytic functions: Part A.—On the problem of smoothing or graduation. A first class of analytic approximation formulae. In IJ Schoenberg Selected Papers; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1988; pp. 3–57. [Google Scholar]

- Shallu Kumari, A.; Kukreja, V.K. An Improved Extrapolated Collocation Technique for Singularly Per-turbed Problems using Cubic B-Spline Functions. Mediterr. J. Math. 2021, 18, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shallu Kukreja, V.K. An improvised collocation algorithm with specific end conditions for solving modified Burgers equation. Numer. Methods Partial. Differ. Equ. 2021, 37, 874–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukreja, V.K. Numerical treatment of Benjamin-Bona-Mahony-Burgers equation with fourth-order im-provised B-spline collocation method. J. Ocean. Eng. Sci. 2022, 7, 99–111. [Google Scholar]

- Roul, P.; Goura, V.M.K.P. A sixth order numerical method and its convergence for generalized Black–Scholes PDE. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2020, 377, 112881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, R. Quintic B-spline collocation approach for solving generalized Black–Scholes equation governing option pricing. Comput. Math. Appl. 2015, 69, 777–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadalbajoo, M.K.; Tripathi, L.P.; Kumar, A. A cubic B-spline collocation method for a numerical solution of the generalized Black–Scholes equation. Math. Comput. Model. 2012, 55, 1483–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavero, C.; Jorge, J.C.; Lisbona, F. Uniformly convergent schemes for singular perturbation problems combining alternating directions and exponential fitting techniques. In Applications of Advanced Computational Methods for Boundary and Interior Layers; Boole Press: Dublin, Ireland, 1993; pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- González, C.; Palencia, C. Stability of time-stepping methods for abstract time-dependent parabolic prob-lems. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1998, 35, 973–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.D. Computational Methods in Ordinary Differential Equations; John Wiley and Sons Incorporated: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Lax, P.D.; Richtmyer, R.D. Survey of the stability of linear finite difference equations. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 1956, 9, 267–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, R.C.; Jain, R.K. B-splines methods with redefined basis functions for solving fourth order parabolic partial differential equations. Appl. Math. Comput. 2011, 217, 9741–9755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varah, J.M. A lower bound for the smallest singular value of a matrix. Linear Algebra Its Appl. 1975, 11, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, R.S. Matrix Iterative Analysis; Springer Science and Business Medi: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Prenter, P.M. Splines and Variational Methods; Courier Corporation: North Chelmsfor, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.A.; Meyer, W.W. Optimal error bounds for cubic spline interpolation. J. Approx. Theory 1976, 16, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).