Abstract

This research uses the computing of conceptual distance to measure information content in Wikipedia categories. The proposed metric, generality, relates information content to conceptual distance by determining the ratio of the information that a concept provides to others compared to the information that it receives. The DIS-C algorithm calculates generality values for each concept, considering each relationship’s conceptual distance and distance weight. The findings of this study are compared to current methods in the field and found to be comparable to results obtained using the WordNet corpus. This method offers a new approach to measuring information content applied to any relationship or topology in conceptualization.

Keywords:

information content; semantic similarity; Wikipedia; conceptual distance; generality; graphs MSC:

68T30

1. Introduction

The success of information society and the World Wide Web has substantially increased the availability and quantity of information. The computational analysis of texts has aroused a great interest in the scientific community to allow adequate exploitation, management, classification, and textual data retrieval. Significant contributions have improved the comprehension of different areas using conceptual representations, such as semantic networks, hierarchies, and ontologies. These structures are models to conceptualize domains considering concepts from these representations to define semantic relationships between them [1]. The semantic similarity assessment is a very timely topic related to the explanation analysis of electronic corpora, documents, and textual information to provide novel approaches in recommender systems, information retrieval, and question-answering applications. According to psychological tests conducted by Goldstone (1994) [2], semantic similarity plays an underlying foundation by which human beings arrange and classify objects or entities.

Semantic similarity is a metric that states how close two words (representing objects from a conceptualization) are by exploring whether they share any feature of their meaning. For example, horse and donkey are similar in the context that they are mammals. Conversely, for examples such as boat and oar or hammer and screwdriver, their semantic relations do not directly depend on the higher concept of a semantic structure. Moreover, other relationships, such as meronymy, antonymy, functionality, and cause–effect, do not have a taxonomic definition but are part of the conceptualization. In the same way, arrhythmia and tachycardia are close because both diseases are related to the cardiovascular system. Additionally, the concepts are necessarily associated with non-taxonomic relationships; for example, insulin assists in the treatment of diabetes illness. In this sense, we say that a semantic relationship is one in which both cases consist of evaluating the semantic evidence presented in a knowledge source (ontology or domain corpus).

It is important to clarify that semantic similarity is not by itself a relationship, at least not in the same sense as meronymy or antonymy. In this context, similarity is a measure calculated between pairs of concepts, while the “other” relationships serve to “connect” and give meaning to the concepts. Within these relationships, some generate a hierarchical or taxonomic structure; for example, they can represent hyperonymy or hyponymy, which is the type of structure needed by many algorithms that compute semantic similarity. Thus, the DIS-C algorithm works with this type of relationship and those not generating taxonomies (for example, meronymy or antonymy).

The similarity measures assign a numerical score that quantifies this proximity based on the semantic evidence defined in one or more sources of knowledge [3]. These resources traditionally consist of more general taxonomies and ontologies, providing a formal and machine-readable way of expressing a shared conceptualization through integrated vocabulary and semantic linkings [4].

In particular, semantic similarity is suitable in tasks oriented to identify objects or entities that are conceptually near. According to the state of the art, this approach is appropriate in information systems [5]. Recently, semantic similarity has represented a pivotal issue in the technological advances concerning the semantic search field. In addition, the semantic similarity supplies a comparison of data infrastructures in different knowledge environments [6,7].

In the literature, semantic similarity is applicable in different fields of computer science, particularly novel applications focused on the information retrieval task to increase the precision and recall [8,9,10,11]; to find matches between ontology concepts [12,13]; to assure or restore ontology alignment [14]; for question-answering systems [15]; for tasks for natural language processing, such as tokenization, stopwords removing, lemmatization, word sense disambiguation, lemmatization, and named entity recognition [16,17]; for recommender systems [18,19]; for data and feature mining [20,21,22]; for multimedia content search [23]; for semantic data and intelligent integration [24,25]; for ontology learning based on web-scrapping techniques, where new definitions connected to existing concepts should be acquired from document resources [26]; for text clustering [27]; for biomedical context [28,29,30,31]; and for geographic information and cognitive sciences [6,32,33,34,35]. In a pragmatic perception, the semantic similarity helps us to comprehend human judgment, cognition, and understanding to categorize and classify various conceptualizations [36,37,38]. Thus, similitude is an essential theoretical foundation in semantic-processing tasks [39,40].

According to the evidence modeled on an ontology (taxonomy), the similarity measurements based on an ontological definition evaluate how concepts are similar by their meaning. So, the intensive mining of multiple ontologies produces further insights to enhance the approximation of similitude and determines different circumstances, where concepts are not defined in an exclusive ontology [9]. Based on the state of the art, various semantic similarity measurements are context-independent [41,42,43,44]; most of them were designed specifically for the problem and expressed on the base of domain-specific or application-oriented formalisms [31]. Thus, a person who is not a specialist can only interpret the great diversity of avant garde proposals as an extensive list of measures. Consequently, selecting an appropriate measurement for a specific usage context is a challenging task [1].

Thus, to compute semantic similarity automatically, we may consult different knowledge sources [45], such as domain ontologies like gene ontology [29,46], SNOMED CT [30,31,47], well-defined semantic networks like WordNet [48,49], and theme directories like the Open Directory Project [50] or Wikipedia [51].

Pirró (2009) [52] classified the approaches to assess similarity concerning the use of the information they manage. The literature proposed diverse techniques based on how an ontology determines similarity values. Nevertheless, Meng et al. (2013) [53] stated a classification for the semantic similarity measures: edge-counting techniques, information content approaches, feature-based methods, and hybrid measurements.

- Edge-counting techniques [44] evaluate semantic similarity by computing the number of edges and nodes separating two concepts (nodes) within the semantic representation structures. We defined the technique preferably for taxonomic relationships (edges and nodes) in a semantic network.

- Information content-based approaches assess the similitude by applying a probabilistic model. It takes as input the concepts of an ontology and employs an information content function to determine their similarity values in the ontology [41,54,55]. The literature bases the information content computation on the distribution of tagged concepts in the corpora. Obtaining information content from concepts consists of structured and formal methods based on knowledge discovery [31,56,57,58].

- Feature-based methods assess similitude values employing the whole conventional and non-conventional features by a weighted sum of these items [19,59]. Thus, Sánchez et al. (2012) [4] designed a model of non-taxonomic and taxonomic relationships. Moreover, ref. [34,60] proposed to use interpretations of concepts retrieved from a thesaurus. Then, the edge-counting techniques improve since the evaluation considers a semantic reinforcement. In contrast, they do not consider non-taxonomic properties because they rarely appear in an ontology [61] and demand a fine tuning of the weighting variables to merge diverse semantic reinforcements [60]. Additionally, the edge-counting techniques examine the similarity concerning the shortest path about the number of taxonomic links, dividing two concepts into an ontology [42,44,62,63].

- Hybrid measurements integrate various data sets, considering, in these methods, that the weights establish the portion of each data set, contributing to the similarity values to be balanced [5,63,64,65].

In this work, we are interested in approaches based on information content to evaluate the similarity between concepts within semantic representations. In principle, the information content (IC) is computed from the presence of concepts in a corpus [41,43,54]. Thus, some authors proposed the IC from a knowledge structure modeled in an ontology in various ways [3,40,56]. The measurements of IC consist of ontological knowledge, which is a drawback because they depend entirely on the coverage and details of the input ontology [3]. With the appearance of social networks [66,67], diverse concepts or terms, such as proper names, brands, acronyms, and new words, are not contained in application and domain ontologies. Thus, we cannot compute the information content supported by the knowledge resource with this information source. Domain ontologies have the problem that their construction process takes a long time, and their maintenance also requires much effort. For this reason, computation methods based on domain ontologies also have the same problem. An alternative is the crowdsensing sources, such as Wikipedia [51], which is created and maintained by the user community, which means that it is updated in a very dynamic way but maintains a set of good practices.

Additionally, this paper proposes a network model-based approach that uses an algorithm that iteratively evaluates how close two concepts are (i.e., conceptual distance) based on the semantics that an ontology expresses. A metric defined as generality of concepts is computed directly by mapping the IC of these same concepts. Network-based models represent knowledge in different manners and semantic structures, such as ontologies, hierarchies, and semantic networks. Frequently, the topology of these models consists of concepts, properties, entities, or objects depicted as nodes and relations defined by edges that connect the nodes and give causality to the structure. With this model, we used the DIS-C algorithm [68] to compute the conceptual distance between the concepts of an ontology, using the generality metric (it describes how a concept is visible to any other on the ontology) that will be mapped directly to the IC. The generality assumes that a strongly connected graph characterizes an ontological structure. Our method establishes the graph topology for the relationships between nodes and edges. Subsequently, each relationship receives a weighing value, considering the proximity between nodes (concepts). At first, a domain specialist could assign or establish the weighing values randomly.

The computation metric takes the inbound and outbound relationships of a concept. Thus, we perform an iterative adjustment to obtain an optimal change in the weighting values. In this way, the DIS-C algorithm evaluates the conceptual distances without any manual intervention and eliminates the subjectivity of human perceptions concerning the weights proposed by subjects. The network model applicable to DIS-C supports any relationship (hierarchies, meronyms, and hyponomies). We applied the DIS-C algorithm and the GEONTO-MET method [69] to compute the similitude in the feature-based approach [5], which is one of the most common models to represent the knowledge domain.

The research paper is structured as follows: Section 2 comprises the state of the art for similarity measures and approaches to computing the information and their computer science applications. Section 3 presents the methodology and foundations concerning the proposed algorithm. Section 4 shows the results of the experiments that characterize its performance. We present a discussion regarding the findings of our research in Section 5.

2. Related Work

2.1. Semantic Similarity

Ontologies have aroused considerable interest in the semantic similarity research community. These conceptual artifacts offer a structured and unambiguous representation of knowledge through interconnected conceptualizations, employing semantic connections [59]. Moreover, we use ontologies extensively to evaluate the closeness grade of two or more concepts. In other words, the topology of an ontological representation determines the conceptual distance between objects. According to the literature review, an ontology should be refined by adding different data sources for computing and enhancing the semantic similitudes. Zadeh and Reformat (2013) [70] propose diverse methods to compute semantic similarity. Various approaches have assessed the similarity between terms in lexicographic repositories and corpora [71]. Li et al. (2006) [72] established a method to compute semantic similarity among short phrases. The similarity measurements based on distance assess it by using data sets [73,74], such as semantic network-based representations, such as WordNet and MeSH [75], or novel information repositories of crowdsensing as Wikipedia [51].

There are ontology-based methods for computing and evaluating similarity in the biomedical domain. For instance, Batet et al. (2011) [28] developed a similarity function that can perform a precision level comparable to corpus-based techniques while maintaining a low computation cost and unrestricted path-based measure. This approach concentrates on path-based assessment because it considers the use of the physical model of the ontology. There is no need for preliminary data processing; consequently, it is more computationally efficient. By highlighting their equivalences and proposing connections between their theoretical bases for the biomedical field, Harispe’s unifying framework for semantic measures aims to improve the understanding of these metrics [1].

In addition, Zadeh and Reformat (2013) [70] proposed a method for determining the degree to which concepts defined in an ontology are semantically similar to another one. In contrast to other techniques that assess similarity based on the ontological definition of concepts, this method emphasizes the semantic relationships between concepts. It cannot only define similarity at the definition/abstract level, but it can also estimate the similarity of particular segments of information that are instances/objects of concepts. The approach conducts a similarity analysis that considers the context, provided that only particular groups of relationships are highlighted by the context. Sánchez et al. (2012) [59] suggested a taxonomic characteristic-based measure based on an ontology, examining the similarities and how ontologies are used or supplemented with other sources and data sets.

A similar principle is the Tversky’s model [38]; this principle states that the similarity degree between two concepts can be calculated using a function that supports taxonomic information. Further, Sánchez et al. (2012) [76] indicated that a straightforward terminological pairing between ontological concepts addresses issues relating to integrating diverse sources of information. By comparing the similarities between the structure of various ontologies and the designed taxonomic knowledge, Sánchez et al. (2012) [4] made efforts to improve the methods. The first one emphasizes the principles of information processing, which consider knowledge assets modeled in the ontology when predicting the semantic correlation between numerous ontologies modeled in a different form. The second one uses the network of structural and semantic similarities among different ontologies to infer implicit semantics.

Moreover, Saruladha et al. (2011) [77] described a computational method for evaluating the semantic similarity between distinct and independent ontology concepts without constructing a common conceptualization. The investigation examined the possibility of adjusting procedures based on the information content of a single existing ontology to the proposed methods, comparing the semantic similarity of concepts from various ontologies. The methods are corpus-independent and coincide with evaluations performed by specialists. To measure the semantic similarity between instances within an ontology, Albertoni and De Martino (2006) [71] proposed a framework in this context. The goal was to establish a sensitive semantic similarity measure, contemplating diverse hidden hints in the ontology and application context definition. Formica (2006) [78] described an ontology-based method to assess similarity based on formal concept analysis.

There are ontology-based approaches oriented towards computing similarity between a pair of concepts in an ontological structure. For instance, Albacete et al. (2012) [79] defined a similarity function that requires information on five features: compositional, gender, fundamental, limitate, and illustrative. The weighted and combined similitude values generated a general similarity method, tested using the WordNet ontology. Goldstone (1994) [80] developed a technique to measure similarity in the scenario that, given a set of items displayed on a screen device, the subjects reorganize them according to their coincidence or psychological similitude.

Consequently, defining hierarchies and ontologies is the most frequent form of describing knowledge. Nowadays, research works have proposed several high-level ontologies, such as SUMO [81], WordNet [82], PROTON [83], SNOMED-CT [84], Gene Ontology [85], Kaab [69], and DOLCE [86], among others. The knowledge representation of these ontologies is a graph-based model composed of concepts (nodes) and relations (edges).

Semantic similarity computing in graph-based models holds various ways to be calculated. For example, the measurements proposed by [42,44,62] used graph theory techniques to compute similarity values. Thus, the above measurements are suitable for hierarchies and taxonomies due to the underlying knowledge considered when comparing similarity. The main problem with these approaches is the dependence on the homogeneity and coverage of relationships in the ontology. Examples of ontologies such as WordNet are good candidates for applying these measurements due to their homogeneous distribution of relationships and coverage between different domains [41]. So, Resnik (1999) [55] described a similarity measurement based on information content given by two concepts to determine their similarity. Thus, it is necessary to quantify the ordinary information within their conceptual representation. This value represents the least common subsumer (LCS) of input items in a taxonomy. There are changes in this measurement. For example, the Resnik-type needs two criteria: (1) the arrangement of the subsumption hierarchy, and (2) the procedure applied to determine the information content.

2.2. Information Content Computation

Measuring the “amount of data” provided by a concept in a specific domain is crucial in computational linguistics. One of the most important metrics for this is information content (IC). Generally speaking, more general and abstract concepts have less information than more particular and concrete entities [56]. According to Pirró (2009) [52], IC is a measure of the amount of information provided by concepts, computed by counting how many times a term appears in a corpus. IC measures the amount of information about a term based on its likelihood of appearing in a corpus. It has been widely used in computing semantic similarity, mainly for organizing and classifying objects [3,28,31,41,43,52,54,55,56,78,87].

According to Rada et al. (1989) [44] and Resnik (1995) [43], the IC of a concept c is obtained, considering the negative logarithmic probability: , where is the probability of finding c in a given corpus. Specifically, let C be a set of concepts in an IS-A taxonomical representation, allowing multiple inheritances. Let the taxonomy be increased with a function p so that for any , is the likelihood of discovering an instance of the concept c. This entails that p is monotonous as one goes up the taxonomy: if IS-A , then . In addition, if the taxonomy has a single upper node, its likelihood is one [43,55].

Due to the limitations imposed by the corpus, some studies tried inherently to derive the information content values from it. These works assume that the taxonomic representation of ontologies such as WordNet [48,49] is structured significantly by expert subjects, where it is necessary to differentiate concepts from the existing ones. Thus, concepts with many homonym relationships are the most general and give less information than the leaf’s concepts in the hierarchy. The information theory field considers that the most abstract concepts show up with greater probability in a corpus since they are concepts that subsume many others. Then, the occurrence likelihood of a concept, including its information quantity, defines a function given by the overall value of hyponyms and their relative depth in the taxonomy [4,40].

The classical approaches of information theory [41,43,54] acquire the information content of a concept a by calculating the inverse of its probability of occurrence in a corpus (). In this way, uncommon terms provide more information than common ones (see Equation (1)):

It is important to mention that the incidence of each term within the corpus is counted as an additional occurrence of each of its taxonomical ancestors defined by an IS-A relationship (Equation (2)) [54]:

where is the set of terms in the corpus whose meanings are subsumed by a, and N is the overall number of terms embedded in the taxonomical representation.

On the other hand, Seco et al. (2004) [57] calculated the information content considering the overall number of hyponyms established for a concept. Thus, is the number of hyponyms in the taxonomical structure underneath the concept a, while N is the highest amount of concepts in the taxonomy (see Equation (3)):

According to Equation (3), the denominator is a leaf concept that is the most descriptive representation that yields normalized values of information content in the range from 0 to 1. Notice that the numerator processes the concept as a hyponym to prevent in case a is a leaf.

This method only engages a concept’s hyponyms of the taxonomical representation. Accordingly, if concepts containing the same frequency of hyponyms but differing degrees of generality are held high in the hierarchy, then any others will be identical. Thus, Zhou et al. (2008) [58] faced this issue by increasing the hyponym-based information content in the calculation with the concept’s relative depth in the taxonomy (see Equation (4)):

Additionally, and N have the same meaning as in Equation (3), in which is the value corresponding to the depth of the concept a in the taxonomy, and D is the higher depth of the whole taxonomy. Moreover, k is a setting item that modifies the weight of two features to evaluate the information content.

Sánchez et al. (2011) [56] presented an IC computation considering the possibility of having multiple inheritances because concepts that inherit multiple subsumers become more specific than those inherited from a fixed subsume. Even if they reside within the same level, the form incorporates distinctive features from many concepts, even if they share the same level of complexity. This strategy captures an extensive and rational concept formation than other research works based solely on taxonomic depth. Thus, the IC computation is performed by applying Equation (5):

where and such as ≪ is a binary relationship , being that C is the set of concepts in the ontology, where means that a is a hierarchical specialization of c, and L denotes the maximum number of leaves.

The proposed IC measurements always use the idea of the LCS. In the case of WordNet, it only uses the hyponymy relationship to characterize this property. In Sánchez et al. (2012) [4], the semantic similarity measurements based on the IC approaches proposed by the same authors a year earlier are presented.

Jiang et al. (2017) [45] provided multiple and innovative approaches for computing the informativeness of a concept and the similarity between two terms to overcome the limitations of the existing methods to calculate the information content and semantic similarity. The work computes the IC and similarity using the Wikipedia category structure. Note that the Wikipedia category structure is too large; the authors presented different IC calculation approaches by extending traditional methods. Based on these IC calculation techniques, they defined a method to calculate semantic similarity. In this case, the generalization of existing approaches to measure similarity for the Wikipedia categories was proposed. They tried to generalize what traditional IC-based methods are: finding the LCS (least common subsumer) of two concepts.

2.3. The WordNet Corpus

WordNet is a lexical database and resource for natural language processing and computational linguistics. It is an extensive, machine-readable database of words and their semantic relationships, including synonyms, antonyms, hypernyms (more general terms), hyponyms (more specific terms), and meronyms (part–whole relationships). Researchers at Princeton University created WordNet, widely used in various applications, such as information retrieval, text analysis, and natural language understanding (Fellbaum (2010)) [88]. It helps computers understand the meanings and relationships between words, making it a valuable tool in natural language processing and artificial intelligence tasks. Its structure is described as follows:

- Hierarchy of synonyms (Synset): WordNet’s central structure comprises sets of synonyms or “synsets”. Thus, each synset groups words that are interchangeable in a specific context and represent a concept or meaning. For example, the synset for “cat” would include words like “feline”, “pussy”, and “pet”.

- Relationships between Synsets: WordNet establishes sets of semantic relationships between synsets to represent the relationships between words and concepts. Some of the more common relationships include the following:

- –

- Hypernymy/hyponymy. It is a hierarchical relationship where a more general synset is a hyperonym of a more specific synset (hyponym). For example: “animal” (hypernym) is a hypernym of “cat” (hyponym).

- –

- Meronymy/holonymy. This relationship denotes the synsets’ part–whole or member relationship. For instance, “wheel” (meronym) is a part of “car” (holonym).

- –

- Antonymy. This relationship shows that two words have opposite meanings. For example: “good” is an antonym of “bad”.

- –

- Entailment. It indicates that one action implies another. For example: “kill” implies “injure”.

- –

- Similarity. It represents the similarity between the synsets, although they are not necessarily interchangeable. For instance, “cat” is similar to “tiger”.

- –

- Attribute. It describes the characteristics or attributes associated with a noun. For example, “high” is an attribute of “mountain”.

- –

- Cause. It indicates the cause–effect relationship between two events. For example: “rain” causes “humidity”.

- –

- Verb group. Match verbs that are used in similar contexts. For example, “to eat” and “to drink” belong to the group of feeding verbs.

- –

- Derivation. It shows the relationship between an adjective and a noun from which it is derived. For instance, “feline” is derived from “cat”.

- –

- Domain. It indicates the area of knowledge or context in which a synset is used. For example, “mathematics” is the domain of “algebra”.

- –

- Member holonymy. It indicates that an entity is a member of a larger group. For instance, “student” is a member of “class”.

- –

- Instance hyponymy. It shows that one synset is an instance of another. For example: “Wednesday” is an instance of “day of the week”.

- Word positions. Each word in a synset may be tagged as a part of speech (noun, verb, adjective, or adverb). This use makes it possible to distinguish different uses and meanings of a word.

- Definitions and examples. Synsets may be accompanied by definitions and usage examples that help clarify the meaning and context of the words.

- Synonymy and polysemy. WordNet addresses synonymy (several words with the same meaning) and polysemy (one word with multiple meanings) by providing separate synsets for each meaning and showing how they are related.

- Verb database. WordNet also includes a verb database that shows relationships between verbs and their arguments, such as “subject”, ”direct object”, and “indirect object”.

- Taxonomy. The structure of WordNet resembles a hierarchical taxonomy in which more general concepts (hyperonyms) are found at higher levels, and more specific concepts (hyperonyms) are found at lower levels.

2.4. The Wikipedia Corpus

Wikipedia is a free, multilingual, and collaboratively edited encyclopedia managed by the Wikipedia Foundation, a non-profit organization that relies on donations for support. It features over 50 million articles in 300 languages created by volunteers worldwide. It is a vast, domain-independent encyclopedic resource [89]. In recent years, various studies have utilized this corpus to address various issues [51,90,91,92,93,94]. The text on Wikipedia is highly structured for online use and has a specific organizational structure.

- Articles. Wikipedia’s primary information unit is an article composed of free text following a detailed set of editorial and structural rules to ensure consistency and coherence. Each article covers a single concept, with a separate article for each. Article titles are concise sentences systematically arranged in a formal thesaurus. Wikipedia relies on collaborative efforts from its users to gather information.

- Referral pages are documents that contain nothing more than a direct link to a set of links. These pages redirect the request to the appropriate article page containing information about the object specified in the request. They lead to different phrases of an entity and thus model synonyms.

- Disambiguation pages collect links for various potential entities to which the original query could refer. These pages allow users to select the intended meaning. They serve as a mechanism for modeling homonymy.

- Hyperlinks are pointers to Wikipedia pages and serve as additional sources of synonyms, missed by the redirecting process. They eliminate ambiguity by coding polysemy. Articles related to other dictionaries and encyclopedias refer to them through resident hyperlinks, which are referred to as a cross-referenced element model.

- The category structure in Wikipedia is a semantic web organized into groups (categories). Articles are assigned to one or more groups that are grouped together and subsequently organized into a “category tree”. This “tree” is not designed as a formal hierarchy but works simultaneously with different classification methods. Additionally, the tree is implemented as an acyclic-directed graph. Thus, categories serve as only organizational nodes with minimal explanatory content.

3. Methods and Materials

This section describes the use of the DIS-C algorithm for computing information content based on the generality of concepts in the corpus.

3.1. The DIS-C Algorithm for Information Content Computation

This work defines conceptual distance as the space dividing two concepts into a particular conceptualization described by an ontology. Another definition concerning conceptual distance addresses the dissimilarity in information content supplied by two concepts, including their specific conceptions.

The main contribution refers to the suitable adaptation of the proposed method in any conceptualization, such as a taxonomy, semantic network, hierarchy, and ontology. Notably, the method establishes a distance value for each relationship (all the types of relations in the conceptualization structure). It converts the last one into a conceptual graph (a weighted–directed graph). Additionally, each node represents a concept, and each edge is a relationship between a couple of concepts.

We apply diverse theoretical foundations from the graph theory to treat the fundamental knowledge encoded within the ontological structure. Thus, once we generate the conceptual graph, the native sequence calculates the shortest path to meet the distance value between unrelated concepts.

The Wikipedia category structure is a very complex network. So, compared to traditional taxonomy structures, Wikipedia is a graph in which the semantic similarity between concepts is evaluated by using the DIS-C algorithm, and the theoretical information approaches based on information content are integrated. So, the DIS-C algorithm computes the IC value of each concept (node) in the graph. Thus, the process guarantees to cover the whole search space.

3.2. Generality

According to Resnik (1999) [55], the information content of a concept c can be represented by the formula . Here, p is the probability that c is associated with any other concept, determined by dividing the sum of concepts with c as their ancestor by the total number of concepts. This method is suitable when considering taxonomic structures, where concepts at the bottom of the hierarchy inherit information from their ancestors, including themselves. Therefore, the information content is proportional to the depth of the taxonomy.

Similarly to the Resnik approach, we propose the “generality” to describe the information content of a concept. However, our method deals with ontologies and taxonomies that can contain multifold types of relations (not only a “is-a” relationship type). Moreover, the “generality” analyzes the information content of the concepts allocated in the ontology, considering how related they are. Thus, the “generality” quantifies how a concept connects with the entire ontology.

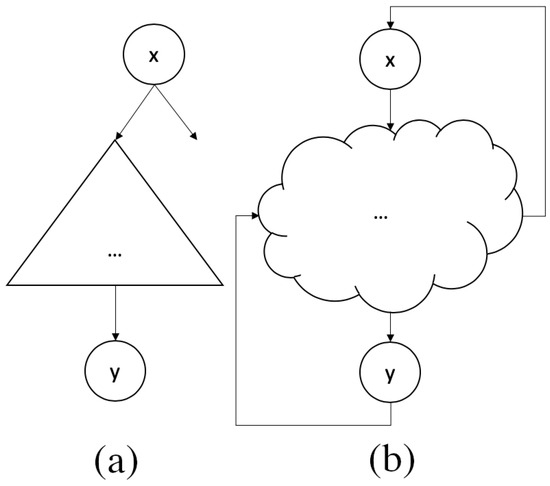

In Figure 1a, we have a taxonomy where the concept x is very general, providing information to the concept y; x is located “above” in the conceptualization, so it only provides information to the concepts that are more “below” and does not obtain any information from them. On the other hand, y obtains information from x and all the concepts found in the path . Moreover, y does not provide information about any concept.

Figure 1.

Taxonomy (it does not have a partition) vs. Ontology (it has partitions).

In Figure 1b, we have an ontology in which concept x not only provides information to concept y but also receives information from y and the rest of the concepts in the ontology. Suppose there is no relationship between x and another different ontology concept. In that case, little information is necessary to identify that concept and denote if it is very general or abstract. Thus, the conceptual distance concerning other concepts can be more significant over the average if it only relates to a few concepts; then, the routes for linking them with most of the rest will be larger too. In contrast, more detailed concepts are established from more general concepts. Thus, let x be a general concept. It implies that the rest of the concepts will be near x in their meanings. If x is the most general concept, the mean distance from other concepts in the ontological representation to x will be smaller. We conclude that the “generality” of concept x refers to the balanced proportion of information content needed by x from other terms for their meanings and IC that x gives to the rest of the concepts in the ontology.

We propose that information provided by a concept x to all others is proportional to the average distance of x towards all the others. Similarly, information obtained by x from all other concepts is proportional to the average distance from all concepts to x. Thus, a first approximation to the definition of generality is shown in Equation (6):

where is the conceptual distance from concept x to concept y in the conceptualization K.

In the case of the taxonomy of Figure 1, the distance from any concept y to a more general concept x will be infinite, as no path connects y with x, so the generality of x is ∞. Otherwise, the generality of y will be 0. To avoid these singularities, we normalize the generality of x. Let be a shared conceptualization of a domain, in which are concepts and refers to the conceptual distance from x to y. So, the generality defined by is represented by Equation (7). Thus, the generality of x will be in the range , where 0 is the maximum generality, and 1 is the minimum. On the other hand, this form of generality is defined as the probability of finding a concept related to x. Then, by using the proposal of Resnik (1995) [43], the IC is defined by Equation (8):

The generality computation needs to know the conceptual distances between any pair of terms. In [68], we presented the DIS-C algorithm to calculate such a distance. The theory behind the DIS-C algorithm is based on analyzing an ontology as a connected graph and computing the weight of each edge by applying the generality definition to each concept (nodes in the graph). We computed the generality to determine the conceptual distance, considering the semantics and intention of the corpora developer to introduce the concepts and their definitions established in the conceptual representation. In conclusion, the nearest concepts are more significant in the conceptualization domain because they explain the corpus. Therefore, the generality of a concept gives information concerning the relationships in the conceptualization, using this approach to define the weighting of each edge.

Due to the conceptual distance calculated with the generality definition, we assumed that those entire nodes (concepts) are similarly generic, and the topology of the conceptual representation is needed to capture the semantics and causality of the corpus. Each degree and vertex is also used as the input and output, respectively. So, the “generality” of each concept and its conceptual distance are computed as follows.

Letting be a conceptualization considering the above definition, the directed graph is generated by converting each concept in a node into the graph : . Subsequently, for each relationship , where , the edge is incorporated into .

The next procedure is to iteratively create from , the weighted directed graph . For this purpose, in the j-th iteration, we make , and, for each edge , edges and are incorporated into , where is the arithmetic mean of the approximation of the conceptual distance from vertex a to vertex b at the j-th iteration. These expressions are computed by applying Equation (9):

where is a variable that specifies how much importance is given to new values, and therein significance given to old values; generally, . is the generality of the vertex at j-th iteration (the value of is computed by considering the graph ). Thus, we establish that , i.e., the early value of generality for all nodes is equal to 1. Additionally, the expressions and are the conceptual distance values of the relations between a and b (onward and backward, respectively), whose values are requested. In the beginning, these conceptual distances are 0, i.e., and for all .

Thus, is the “obtained” value at vertex x. It is also the likelihood of not meeting an edge coming into vertex x, i.e., . Moreover, is the value of “leaving” vertex x, determined by the likelihood of not meeting an edge leaving vertex x, i.e., , where is the inside degree of vertex x, and is the outside degree of the same vertex x.

With the graph , the values of generality for each vertex are computed in the j-th iteration using Equation (7), and considering the shortest path from a to b in graph .

Furthermore, it computes a new conceptual distance value for each relationship in ℜ. This value refers to the mean of distances between edges sharing the same relation. It is obtained by applying Equation (10):

where is the set of edges that represents a relationship .

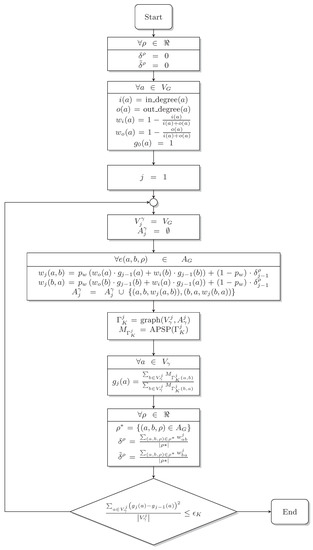

The procedure initiates with and grows the value of j by one until it satisfies the condition of Equation (11), where is the threshold of maximal transition, with the whole procedure depicted in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of the DIS-C algorithm.

3.3. Corpus Used for the Testing: Wikipedia and WordNet

The categories and pages are taken as graph nodes to calculate the conceptual distance. The categories are structured hierarchically through category links, which we use as hypernymy or hyponymy relationships. Hyperlinks are employed as generic relationships; since these vary in their nature, there is no information on the specific semantics of each link.

The experiments to assess the proposed method employed the Wikipedia and WordNet corpus to obtain the information content value, constraining the test to particular categories. Concerning Wikipedia, its entire content is available in a specific format, which allows us to copy, modify and redistribute it with few restrictions. Moreover, we used two downloaded functions: the structure of categories and the list of pages and hyperlinks between them. Thus, data are suitable for generating a database for each corpus graph feature. In the first case, there are 1,773,962 categories represented by nodes and 128,717,503 category links defining the edges. In the second case, 8,846,938 pages correspond to nodes, and 318,917,123 links define their edges.

In the case of WordNet, the synsets become nodes of the DIS-C graph, and each one of the relationships is taken into account. The type is labeled later to calculate the semantic value of each type of relationship as is defined in [68]. Thus, information is accessed through a provided API and a dump file that contains the data. This corpus composes a graph of 155,287 nodes and 324,600 edges.

4. Results and Discussion

In [68], the results of testing the DIS-C algorithm using WordNet as a corpus are presented. Thus, we compare our results with other similarity measures in Table 1.

Indeed, diverse difficulties arose in obtaining the results. However, the largest was the corpus size since we discussed the order of various million concepts and relationships. This issue was faced by emptying all information from Wikipedia into a MySQL database, which allowed us to have structured access to the data through a robust search engine. The database scheme occupies 75.1 GB, and the relations (category links and hyperlinks) occupy the most space with 62.7 GB. Regarding the equipment where the tests were executed, we used a MacPro with an Intel Xeon @ 3.5GHz processor, with 16 GB of DDR3 RAM @1866MHz.

On the other hand, Rubenstein and Goodenough (1965) [95] compiled a set of synonymy judgments composed of 65 pairs of nouns. The set composition gathered 51 judges, who placed a score between 0 and 4 for each couple, pointing out the semantic similitude. Afterward, Miller and Charles (1991) [75] performed the same test but only used 30 pairs of nouns selected from the previous register. The experiment split words with high, medium, and low similarity values.

Jarmasz and Szpakowicz (2003) [96] replicated both tests and showed the outcomes of six similarity measures based on the WordNet corpus. The first one was the edge-counting approach, which serves as a baseline, considering that this measure is the easiest and most cognitive method. Hirst et al. (1998) [97] designed a method based on the length of the path and the values concerning its direction. The semantic relationships of WordNet defined these changes.

In the same context, Jiang and Conrath (1997) [41] developed a mixed method related to the improved edge counting approach by the node-based technique for computing the information content stated by Resnik (1995) [43]. Thus, Leacock and Chodorow (1998) [62] summed the length of the path in a set of nodes instead of relationships, and the length was adjusted according to the taxonomy depth. Moreover, Lin (1998) [54] used the fundamental equation of information theory to calculate the semantic similarity. Alternatively, Resnik (1995) [43] computed the information content by the subsumption of concepts in the taxonomy or hierarchy. Those similarity measures and their values obtained by our algorithm (the asymmetry property does not hold for conceptual distance (); as a result, we express the conceptual distance from term A to term B (DIS-C(to) column), from term B to term A (DIS-C(from) column), the average of these distances (DIS-C(avg) column), the minimum (DIS-C(min) column), and the maximum (DIS-C(max) column)) are presented in Table 1.

As mentioned previously in the Miller and Charles (1991) [75] study, the analysis consisted of asking 51 individuals to make a judgment concerning the similarity of 30 pairs of words, considering for the evaluation a scale defined between 0 and 4, in which 0 is not at all similar, and 4 is very similar. Several authors have proposed different scales for evaluating similarity; in general, 0 is entirely different, and there can be some positive values for identical concepts. However, the DIS-C method does not calculate similarity (directly); it computes the distance. That is how it takes values that go from 0 (for identical concepts), and it does not have an upper bound since it can take distance values as large as the corpus is vast. For this reason, Table 2 shows the correlation between the values obtained by different methods (including ours) and those obtained by Miller and Charles (1991) [75]. In other words, it shows the correlation coefficient between the human judgments proposed by Miller and Charles (1991) [75] and the values attained by other techniques, including our method and the best result revealed by Jiang et al. (2017) [45]. According to the results, it is appreciated that the proposed approach achieves the best correlation coefficient for the rest of the methods. These outcomes suggest that conceptual distances calculated applying the DIS-C algorithm are more consistent than human judgments.

Table 1.

The similarity of pairs of nouns proposed by Miller and Charles (1991) [75].

Table 1.

The similarity of pairs of nouns proposed by Miller and Charles (1991) [75].

| Word A | Word B | Miller and Charles (1991) [75] | WordNet Edges | Hirst et al. (1998) [97] | Jiang and Conrath (1997) [41] | Leacock and Chodorow (1998) [62] | Lin (1998) [54] | Resnik (1995) [43] | DIS-C(to) | DIS-C(from) | DIS-C(avg) | DIS-C(min) | DIS-C(max) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| asylum | madhouse | 3.61 | 29.00 | 4.00 | 0.66 | 2.77 | 0.98 | 11.28 | 1.22 | 1.64 | 1.43 | 1.22 | 1.64 |

| bird | cock | 3.05 | 29.00 | 6.00 | 0.16 | 2.77 | 0.69 | 5.98 | 0.63 | 0.33 | 0.48 | 0.33 | 0.63 |

| bird | crane | 2.97 | 27.00 | 5.00 | 0.14 | 2.08 | 0.66 | 5.98 | 1.51 | 1.35 | 1.43 | 1.35 | 1.51 |

| boy | lad | 3.76 | 29.00 | 5.00 | 0.23 | 2.77 | 0.82 | 7.77 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| brother | monk | 2.82 | 29.00 | 4.00 | 0.29 | 2.77 | 0.90 | 10.49 | 0.33 | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.33 | 0.63 |

| car | automobile | 3.92 | 30.00 | 16.00 | 1.00 | 3.47 | 1.00 | 6.34 | 1.26 | 0.59 | 0.92 | 0.59 | 1.26 |

| cemetery | woodland | 0.95 | 21.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 1.16 | 0.07 | 0.70 | 3.21 | 2.49 | 2.85 | 2.49 | 3.21 |

| chord | smile | 0.13 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 1.07 | 0.29 | 2.89 | 2.67 | 3.95 | 3.31 | 2.67 | 3.95 |

| coast | forest | 0.42 | 24.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 1.52 | 0.12 | 1.18 | 1.84 | 2.89 | 2.37 | 1.84 | 2.89 |

| coast | hill | 0.87 | 26.00 | 2.00 | 0.15 | 1.86 | 0.69 | 6.38 | 1.22 | 1.58 | 1.40 | 1.22 | 1.58 |

| coast | shore | 3.70 | 29.00 | 4.00 | 0.65 | 2.77 | 0.97 | 8.97 | 0.33 | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.33 | 0.63 |

| crane | implement | 1.68 | 26.00 | 3.00 | 0.09 | 1.86 | 0.39 | 3.44 | 1.55 | 1.82 | 1.69 | 1.55 | 1.82 |

| food | fruit | 3.08 | 23.00 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 1.39 | 0.12 | 0.70 | 0.85 | 1.58 | 1.21 | 0.85 | 1.58 |

| food | rooster | 0.89 | 17.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.83 | 0.09 | 0.70 | 2.10 | 1.94 | 2.02 | 1.94 | 2.10 |

| forest | graveyard | 0.84 | 21.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 1.16 | 0.07 | 0.70 | 2.27 | 1.55 | 1.91 | 1.55 | 2.27 |

| furnace | stove | 3.11 | 23.00 | 5.00 | 0.06 | 1.39 | 0.24 | 2.43 | 1.26 | 0.62 | 0.94 | 0.62 | 1.26 |

| gem | jewel | 3.84 | 30.00 | 16.00 | 1.00 | 3.47 | 1.00 | 12.89 | 0.58 | 1.31 | 0.94 | 0.58 | 1.31 |

| glass | magician | 0.11 | 23.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 1.39 | 0.12 | 1.18 | 2.08 | 2.58 | 2.33 | 2.08 | 2.58 |

| journey | car | 1.16 | 17.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.83 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.24 | 1.59 | 1.42 | 1.24 | 1.59 |

| journey | voyage | 3.84 | 29.00 | 4.00 | 0.17 | 2.77 | 0.70 | 6.06 | 0.26 | 0.68 | 0.47 | 0.26 | 0.68 |

| lad | brother | 1.66 | 26.00 | 3.00 | 0.07 | 1.86 | 0.27 | 2.46 | 1.55 | 2.16 | 1.85 | 1.55 | 2.16 |

| lad | wizard | 0.42 | 26.00 | 3.00 | 0.07 | 1.86 | 0.27 | 2.46 | 1.55 | 2.23 | 1.89 | 1.55 | 2.23 |

| magician | wizard | 3.50 | 30.00 | 16.00 | 1.00 | 3.47 | 1.00 | 9.71 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| midday | noon | 3.42 | 30.00 | 16.00 | 1.00 | 3.47 | 1.00 | 10.58 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| monk | oracle | 1.10 | 23.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 1.39 | 0.23 | 2.46 | 2.78 | 2.49 | 2.63 | 2.49 | 2.78 |

| monk | slave | 0.55 | 26.00 | 3.00 | 0.06 | 1.86 | 0.25 | 2.46 | 1.90 | 1.47 | 1.69 | 1.47 | 1.90 |

| noon | string | 0.08 | 19.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.98 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.49 | 2.86 | 2.68 | 2.49 | 2.86 |

| rooster | voyage | 0.08 | 11.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.53 | 3.10 | 2.81 | 2.53 | 3.10 |

| shore | woodland | 0.63 | 25.00 | 2.00 | 0.06 | 1.67 | 0.12 | 1.18 | 1.92 | 1.92 | 1.92 | 1.92 | 1.92 |

| tool | implement | 2.95 | 29.00 | 4.00 | 0.55 | 2.77 | 0.94 | 6.00 | 0.68 | 0.26 | 0.47 | 0.26 | 0.68 |

Table 2.

Correlation between the human judgments and the similarity approaches using the WordNet corpus.

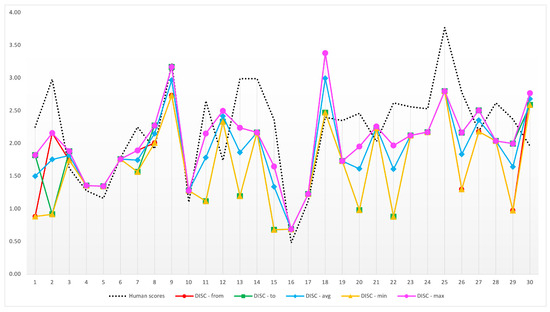

Nevertheless, we validated the computation of the conceptual distance in a larger corpus, such as Wikipedia, by using the 30 pairs of Wikipedia categories proposed by Jiang et al. (2017) [45]. The pairs are presented in Table 3, including their similarity qualification given by a group of people. The results of the calculation of the conceptual distance are also depicted. Moreover, they are represented asymmetrically in Table 1 and shown in Figure 3. It is worth mentioning that Jiang et al. (2017) [45] did not report the corresponding results of similarity values between each pair. In this case, the study presented different methods to calculate the similarity and the correlation of the set of results regarding the reference set (human scores). Table 4 also presents the generality and information content evaluations for the categories proposed in the same work. In this sense, there are no results reported to compare with ours.

Table 3.

Set of 30 concepts (Wikipedia categories) presented in [45] with averaged similarity scores.

Figure 3.

Similarity scores obtained with the DIS-C for the set of 30 categories presented in [45].

Table 4.

The information content and generality for concepts presented in [45].

On the other hand, Jiang et al. (2017) [45] carried out a similar study to that of [75], but they took 30 pairs of the Wikipedia categories. Thus, Table 3 presents these contrasted results with our algorithm’s results. Besides Table 2, we report the correlation values between the human judgments of [45] and the distance values that DIS-C yielded in Table 5.

Table 5.

The correlation between the human judgments and the similarity approaches using the Wikipedia corpus.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents the definition and application of computing the conceptual distance for determining the information content in Wikipedia categories. The generality definition proposes to relate the information content and conceptual distance, which is essential to compute the latter. In the literature, this concept has been used to calculate semantic similarity. However, as we argued in our previous research, it is relevant to remind that semantic similarity is not the same as conceptual distance.

We introduced a novel metric called generality, defined as the ratio between a concept’s information and the information it receives. Thus, the proposed DIS-C algorithm calculates each concept’s generality values. Moreover, we considered the conceptual distance between any couple of concepts and the weight related to each type of relationship in the conceptualization.

The results presented in this research work were compared against other state-of-the-art methods. First, the set of words presented by Miller (1995) [37] serves as a point of comparison (baseline) and calibration for our proposed method. Later, using Wikipedia as a corpus, the results were satisfactory and very similar to those obtained using the corpus of WordNet. On the other hand, we used the 30 concepts (Wikipedia categories) presented by Jiang et al. (2017) [45] to evaluate the results with those they proposed in their work, which has been compared with others in the literature. The results were also satisfactory as can be appreciated in the corresponding tables depicted in Section 4.

On the other hand, the early studies have yet to report their results regarding the value of the information content for each concept or category presented in the sets. Thus, we show these results as a novel contribution due to there being no report or any evidence of other results of previous studies in the literature related to this field. So, we cannot compare this particular issue with them.

It is worth mentioning that to obtain these results, we used algorithms to extract the most relevant subgraphs of the huge graph generated with all the categories and Wikipedia pages; added together, there are more than 10 million entities that have to be analyzed, and this task is not feasible to carry out. Therefore, future works are oriented towards analyzing those algorithms, particularly for calculating such subgraphs and their repercussions on the conceptual distance computation and the information content. Moreover, we want to face one of the most exciting problems of the DIS-C algorithm: the computational complexity that is . For this reason, we will study alternatives to accelerate the DIS-C method based on optimized and approximation algorithms. According to the experiments, we discovered that the bottleneck can be avoided using the proposed 2-hop coverages, bringing the DIS-C almost linearity. Moreover, our efforts will be centered on providing new visualization schemas for these graphs, considering GPU-based programming and augmented reality approaches to improve the information visualization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.Q. and M.T.-R.; methodology, R.Q.; software, R.Q. and C.G.S.-M.; validation, R.Q. and M.T.-R.; formal analysis, R.Q. and M.T.-R.; investigation, R.Q.; resources, F.M.-R. and M.S.-P.; data curation, M.S.-P. and F.M.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, R.Q.; writing—review and editing, M.T.-R.; visualization, C.G.S.-M.; supervision, M.T.-R.; project administration, M.S.-P.; funding acquisition, F.M.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Work partially sponsored by Instituto Politécnico Nacional under grants 20231372 and 20230454. It also is sponsored by Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencias y Tecnologías (CONAHCYT) under grant 7051, and Secretaría de Educación, Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación (SECTEI).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The databases used in this paper are available at https://dumps.wikimedia.org/backup-index.html accessed on 23 March 2023, and https://wordnet.princeton.edu/download accessed on 12 April 2023.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the reviewers for their invaluable and constructive feedback that helped improve the quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Harispe, S.; Sánchez, D.; Ranwez, S.; Janaqi, S.; Montmain, J. A framework for unifying ontology-based semantic similarity measures: A study in the biomedical domain. J. Biomed. Inform. 2014, 48, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstone, R.L. Similarity, interactive activation, and mapping. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 1994, 20, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, D.; Batet, M. A semantic similarity method based on information content exploiting multiple ontologies. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 1393–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, D.; Solé-Ribalta, A.; Batet, M.; Serratosa, F. Enabling semantic similarity estimation across multiple ontologies: An evaluation in the biomedical domain. J. Biomed. Inform. 2012, 45, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, M.; Egenhofer, M. Comparing geospatial entity classes: An asymmetric and context-dependent similarity measure. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2004, 18, 229–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwering, A.; Raubal, M. Measuring semantic similarity between geospatial conceptual regions. In GeoSpatial Semantics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 90–106. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Yang, J.; Yu, P.S. Clustering by pattern similarity in large data sets. In Proceedings of the 2002 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Madison, WI, USA, 4–6 June 2002; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 394–405. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mubaid, H.; Nguyen, H. A cluster-based approach for semantic similarity in the biomedical domain. In Proceedings of the Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, 2006, EMBS’06, 28th Annual International Conference of the IEEE, New York, NY, USA, 30 August–3 September 2006; pp. 2713–2717. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mubaid, H.; Nguyen, H. Measuring semantic similarity between biomedical concepts within multiple ontologies. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part C (Appl. Rev.) 2009, 39, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budan, I.; Graeme, H. Evaluating WordNet-Based Measures of Semantic Distance. Comutational Linguist. 2006, 32, 13–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hliaoutakis, A.; Varelas, G.; Voutsakis, E.; Petrakis, E.G.; Milios, E. Information retrieval by semantic similarity. Int. J. Semant. Web Inf. Syst. (IJSWIS) 2006, 2, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Baliyan, N.; Sukalikar, S. Ontology Cohesion and Coupling Metrics. Int. J. Semant. Web Inf. Syst. (IJSWIS) 2017, 13, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirrò, G.; Ruffolo, M.; Talia, D. SECCO: On building semantic links in Peer-to-Peer networks. In Journal on Data Semantics XII; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Meilicke, C.; Stuckenschmidt, H.; Tamilin, A. Repairing ontology mappings. In Proceedings of the AAAI, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 22–26 July 2007; Volume 3, p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Tapeh, A.G.; Rahgozar, M. A knowledge-based question answering system for B2C eCommerce. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2008, 21, 946–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwardhan, S.; Banerjee, S.; Pedersen, T. Using measures of semantic relatedness for word sense disambiguation. In Computational Linguistics and Intelligent Text Processing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 241–257. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, R.; Mihalcea, R. Unsupervised graph-basedword sense disambiguation using measures of word semantic similarity. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Semantic Computing (ICSC 2007), Irvine, CA, USA, 17–19 September 2007; pp. 363–369. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Fernández, Y.; Pazos-Arias, J.J.; Gil-Solla, A.; Ramos-Cabrer, M.; López-Nores, M.; García-Duque, J.; Fernández-Vilas, A.; Díaz-Redondo, R.P.; Bermejo-Muñoz, J. A flexible semantic inference methodology to reason about user preferences in knowledge-based recommender systems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2008, 21, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likavec, S.; Osborne, F.; Cena, F. Property-based semantic similarity and relatedness for improving recommendation accuracy and diversity. Int. J. Semant. Web Inf. Syst. (IJSWIS) 2015, 11, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J.; Ferreira, A.; Aravena, E. Discovering implicit intention-level knowledge from natural-language texts. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2009, 22, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, D.; Isern, D. Automatic extraction of acronym definitions from the Web. Appl. Intell. 2011, 34, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, M.; Greenwood, M.A. A semantic approach to IE pattern induction. In Proceedings of the 43rd Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 25–30 June 2005; pp. 379–386. [Google Scholar]

- Rissland, E.L. AI and similarity. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2006, 21, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, F. Ontology-Based Geospatial Data Integration. In Encyclopedia of GIS; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 812–815. [Google Scholar]

- Kastrati, Z.; Imran, A.S.; Yildirim-Yayilgan, S. SEMCON: A semantic and contextual objective metric for enriching domain ontology concepts. Int. J. Semant. Web Inf. Syst. (IJSWIS) 2016, 12, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, D. A methodology to learn ontological attributes from the Web. Data Knowl. Eng. 2010, 69, 573–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Li, C.H.; Park, S.C. Genetic algorithm for text clustering using ontology and evaluating the validity of various semantic similarity measures. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 9095–9104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batet, M.; Sánchez, D.; Valls, A. An ontology-based measure to compute semantic similarity in biomedicine. J. Biomed. Inform. 2011, 44, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, F.M.; Silva, M.J.; Coutinho, P.M. Measuring semantic similarity between Gene Ontology terms. Data Knowl. Eng. 2007, 61, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, T.; Pakhomov, S.V.; Patwardhan, S.; Chute, C.G. Measures of semantic similarity and relatedness in the biomedical domain. J. Biomed. Inform. 2007, 40, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, D.; Batet, M. Semantic similarity estimation in the biomedical domain: An ontology-based information-theoretic perspective. J. Biomed. Inform. 2011, 44, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, M. Similitud Semantica Entre Sistemas de Objetos Geograficos Aplicada a la Generalizacion de Datos Geo-Espaciales. Ph.D. Thesis, Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nedas, K.; Egenhofer, M. Spatial-Scene Similarity Queries. Trans. GIS 2008, 12, 661–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.A.; Egenhofer, M.J. Determining semantic similarity among entity classes from different ontologies. Knowl. Data Eng. IEEE Trans. 2003, 15, 442–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeren, D.; Mustière, S.; Zucker, J.D. A data mining approach for assessing consistency between multiple representations in spatial databases. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2009, 23, 961–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstone, R.L.; Medin, D.L.; Halberstadt, J. Similarity in context. Mem. Cogn. 1997, 25, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.A. WordNet: A lexical database for English. Commun. ACM 1995, 38, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A.; Gati, I. Studies of similarity. Cogn. Categ. 1978, 1, 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, H.C.; Chen, M.Y.; Chen, Y.M. A semantic-based approach to content abstraction and annotation for content management. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 2360–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, D.; Isern, D.; Millan, M. Content annotation for the semantic web: An automatic web-based approach. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2011, 27, 393–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.J.; Conrath, D.W. Semantic similarity based on corpus statistics and lexical taxonomy. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Research in Computational Linguistics, Madrid, Spain, 7–12 July 1997; pp. 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Palmer, M. Verbs semantics and lexical selection. In Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics, Las Cruces, New Mexico, 27–30 June 1994; pp. 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Resnik, P. Using information content to evaluate semantic similarity in a taxonomy. arXiv 1995, arXiv:cmp-lg/9511007. [Google Scholar]

- Rada, R.; Mili, H.; Bicknell, E.; Blettner, M. Development and application of a metric on semantic nets. Syst. Man Cybern. IEEE Trans. 1989, 19, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Bai, W.; Zhang, X.; Hu, J. Wikipedia-based information content and semantic similarity computation. Inf. Process. Manag. 2017, 53, 248–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.; Dinakarpandian, D. Finding disease similarity based on implicit semantic similarity. J. Biomed. Inform. 2012, 45, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batet, M.; Sánchez, D.; Valls, A.; Gibert, K. Semantic similarity estimation from multiple ontologies. Appl. Intell. 2013, 38, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsaee, M.G.; Naghibzadeh, M.; Naeini, S.E.Y. Semantic similarity assessment of words using weighted WordNet. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2014, 5, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Bao, H.; Xu, D. Concept vector for semantic similarity and relatedness based on WordNet structure. J. Syst. Softw. 2012, 85, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguitman, A.G.; Menczer, F.; Erdinc, F.; Roinestad, H.; Vespignani, A. Algorithmic computation and approximation of semantic similarity. World Wide Web 2006, 9, 431–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medelyan, O.; Milne, D.; Legg, C.; Witten, I.H. Mining meaning from Wikipedia. Int. J. Hum.Comput. Stud. 2009, 67, 716–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirró, G. A semantic similarity metric combining features and intrinsic information content. Data Knowl. Eng. 2009, 68, 1289–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Huang, R.; Gu, J. A review of semantic similarity measures in wordnet. Int. J. Hybrid Inf. Technol. 2013, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, D. An information-theoretic definition of similarity. In Proceedings of the ICML, Madison, WI, USA, 24–27 July 1998; Volume 98, pp. 296–304. [Google Scholar]

- Resnik, P. Semantic similarity in a taxonomy: An information-based measure and its application to problems of ambiguity in natural language. J. Artif. Intell. Res. (JAIR) 1999, 11, 95–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, D.; Batet, M.; Isern, D. Ontology-based information content computation. Knowl. Based Syst. 2011, 24, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seco, N.; Veale, T.; Hayes, J. An intrinsic information content metric for semantic similarity in WordNet. In Proceedings of the ECAI, Valencia, Spain, 22–27 August 2004; Volume 16, p. 1089. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Gu, J. A new model of information content for semantic similarity in WordNet. In Proceedings of the FGCNS’08, Second International Conference on Future Generation Communication and Networking Symposia, Washington, DC, USA, 13–15 December 2008; Volume 3, pp. 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, D.; Batet, M.; Isern, D.; Valls, A. Ontology-based semantic similarity: A new feature-based approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 7718–7728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrakis, E.G.; Varelas, G.; Hliaoutakis, A.; Raftopoulou, P. X-similarity: Computing semantic similarity between concepts from different ontologies. JDIM 2006, 4, 233–237. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, L.; Finin, T.; Joshi, A.; Pan, R.; Cost, R.S.; Peng, Y.; Reddivari, P.; Doshi, V.; Sachs, J. Swoogle: A search and metadata engine for the semantic web. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Washington, DC, USA, 8–13 November 2004; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 652–659. [Google Scholar]

- Leacock, C.; Chodorow, M. Combining Local Context and WordNet Similarity for Word Sense Identification; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998; Volume 49, pp. 265–283. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Bandar, Z.; McLean, D. An approach for measuring semantic similarity between words using multiple information sources. Knowl. Data Eng. IEEE Trans. 2003, 15, 871–882. [Google Scholar]

- Schickel-Zuber, V.; Faltings, B. OSS: A Semantic Similarity Function based on Hierarchical Ontologies. In Proceedings of the IJCAI, Hyderabad, India, 6–12 January 2007; Volume 7, pp. 551–556. [Google Scholar]

- Schwering, A. Hybrid model for semantic similarity measurement. In On the Move to Meaningful Internet Systems 2005: CoopIS, DOA, and ODBASE; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 1449–1465. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Gil, J.; Aldana-Montes, J.F. Semantic similarity measurement using historical google search patterns. Inf. Syst. Front. 2013, 15, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Retzer, S.; Yoong, P.; Hooper, V. Inter-organisational knowledge transfer in social networks: A definition of intermediate ties. Inf. Syst. Front. 2012, 14, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero, R.; Torres-Ruiz, M.; Menchaca-Mendez, R.; Moreno-Armendariz, M.A.; Guzman, G.; Moreno-Ibarra, M. DIS-C: Conceptual distance in ontologies, a graph-based approach. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2019, 59, 33–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.; Quintero, R.; Moreno-Ibarra, M.; Menchaca-Mendez, R.; Guzman, G. GEONTO-MET: An Approach to Conceptualizing the Geographic Domain. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2011, 25, 1633–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, P.D.H.; Reformat, M.Z. Assessment of semantic similarity of concepts defined in ontology. Inf. Sci. 2013, 250, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertoni, R.; De Martino, M. Semantic similarity of ontology instances tailored on the application context. In On the Move to Meaningful Internet Systems 2006: CoopIS, DOA, GADA, and ODBASE; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 1020–1038. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; McLean, D.; Bandar, Z.; O’shea, J.D.; Crockett, K. Sentence similarity based on semantic nets and corpus statistics. Knowl. Data Eng. IEEE Trans. 2006, 18, 1138–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilibrasi, R.L.; Vitanyi, P. The google similarity distance. Knowl. Data Eng. IEEE Trans. 2007, 19, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollegala, D.; Matsuo, Y.; Ishizuka, M. Measuring semantic similarity between words using web search engines. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on World Wide Web, WWW 2007, Banff, AB, Canada, 8–12 May 2007; Volume 7, pp. 757–766. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, G.A.; Charles, W.G. Contextual correlates of semantic similarity. Lang. Cogn. Process. 1991, 6, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, D.; Moreno, A.; Del Vasto-Terrientes, L. Learning relation axioms from text: An automatic Web-based approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 5792–5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saruladha, K.; Aghila, G.; Bhuvaneswary, A. Information content based semantic similarity for cross ontological concepts. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2011, 3, 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Formica, A. Ontology-based concept similarity in formal concept analysis. Inf. Sci. 2006, 176, 2624–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albacete, E.; Calle-Gómez, J.; Castro, E.; Cuadra, D. Semantic Similarity Measures Applied to an Ontology for Human-Like Interaction. J. Artif. Intell. Res. (JAIR) 2012, 44, 397–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Goldstone, R. An efficient method for obtaining similarity data. Behav. Res. Methods Instruments Comput. 1994, 26, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niles, I.; Pease, A. Towards a standard upper ontology. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Formal Ontology in Information Systems-Volume, Ogunquit, ME, USA, 17–19 October 2001; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Fellbaum, C. WordNet: An Electronic Database; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, P.; Yeh, P.Z.; Verma, K.; Vasquez, R.G.; Damova, M.; Hitzler, P.; Sheth, A.P. Contextual ontology alignment of lod with an upper ontology: A case study with proton. In The Semantic Web: Research and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 80–92. [Google Scholar]

- Héja, G.; Surján, G.; Varga, P. Ontological analysis of SNOMED CT. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2008, 8, S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gene Ontology Consortium. The Gene Ontology (GO) database and informatics resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, D258–D261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangemi, A.; Guarino, N.; Masolo, C.; Oltramari, A.; Schneider, L. Sweetening ontologies with DOLCE. In Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management: Ontologies and the Semantic Web; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 166–181. [Google Scholar]

- Buggenhout, C.V.; Ceusters, W. A novel view on information content of concepts in a large ontology and a view on the structure and the quality of the ontology. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2005, 74, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fellbaum, C. WordNet. In Theory and Applications of Ontology: Computer Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 231–243. [Google Scholar]

- Ponzetto, S.P.; Strube, M. Knowledge derived from Wikipedia for computing semantic relatedness. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2007, 30, 181–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittoo, A.; Bouma, G. Minimally-supervised extraction of domain-specific part–whole relations using Wikipedia as knowledge-base. Data Knowl. Eng. 2013, 85, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptein, R.; Kamps, J. Exploiting the category structure of Wikipedia for entity ranking. Artif. Intell. 2013, 194, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nothman, J.; Ringland, N.; Radford, W.; Murphy, T.; Curran, J.R. Learning multilingual named entity recognition from Wikipedia. Artif. Intell. 2013, 194, 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorg, P.; Cimiano, P. Exploiting Wikipedia for cross-lingual and multilingual information retrieval. Data Knowl. Eng. 2012, 74, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, M.; Popescu-Belis, A. Computing text semantic relatedness using the contents and links of a hypertext encyclopedia. Artif. Intell. 2013, 194, 176–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, H.; Goodenough, J.B. Contextual correlates of synonymy. Commun. ACM 1965, 8, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarmasz, M.; Szpakowicz, S. Roget’s Thesaurus and Semantic Similarity. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Recent Advances in Natural Language Processing, Online, 1–3 September 2003; pp. 212–219. [Google Scholar]

- Hirst, G.; St-Onge, D. Lexical Chains as Representations of Context for the Detection and Correction of Malapropisms; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998; Volume 305, pp. 305–332. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).