Abstract

Differential evolution (DE) has shown remarkable performance in solving continuous optimization problems. However, its optimization performance still encounters limitations when confronted with complex optimization problems with lots of local regions. To address this issue, this paper proposes a dual elite groups-guided mutation strategy called “DE/current-to-duelite/1” for DE. As a result, a novel DE variant called DEGGDE is developed. Instead of only using the elites in the current population to direct the evolution of all individuals, DEGGDE additionally maintains an archive to store the obsolete parent individuals and then assembles the elites in both the current population and the archive to guide the mutation of all individuals. In this way, the diversity of the guiding exemplars in the mutation is expectedly promoted. With the guidance of these diverse elites, a good balance between exploration of the complex search space and exploitation of the found promising regions is hopefully maintained in DEGGDE. As a result, DEGGDE expectedly achieves good optimization performance in solving complex optimization problems. A large number of experiments are conducted on the CEC’2017 benchmark set with three different dimension sizes to demonstrate the effectiveness of DEGGDE. Experimental results have confirmed that DEGGDE performs competitively with or even significantly better than eleven state-of-the-art and representative DE variants.

Keywords:

differential evolution; dual elite groups-guided mutation; global numerical optimization; evolutionary algorithms; elite learning MSC:

68-04; 65-04

1. Introduction

Differential evolution (DE) is a population-based random search algorithm proposed by Storn and Price [1]. It is primarily used to solve numerical optimization problems [1,2,3,4]. On account of its ease of implementation and strong global search ability, DE has attracted a great deal of attention from researchers. As a result, many effective DE variants have been developed in recent years [2,3,5,6,7]. In particular, DE variants have won competitions on single objective optimization held in the IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC) in recent years [8,9,10]. Thanks to its good optimization performance when solving optimization problems, DE has also been used for a wide range of academic and engineering applications [5,6,7].

To be specific, a population of individuals are maintained in DE to search the solution space iteratively [1,2,3]. In the population, each individual represents a feasible solution to the optimization problem and undergoes three main processes [4,6,7], namely, the mutation process, the crossover process, and the selection process, to update its position during the iteration. Among the three processes, the mutation process has been demonstrated as the most critical part in DE [11,12,13,14,15] because it has significant influence on the search diversity and the search convergence of DE. As a result, researchers have poured a great deal of attention into designing effective mutation strategies to improve the optimization performance of DE. Resultantly, numerous DE variants with novel mutation schemes have been developed in recent years [16,17,18,19,20,21].

In general, the mutation operation is usually realized by shifting the base individual by the difference vectors between individuals in the population [19,22,23,24,25]. In essence, the key to designing effective mutation strategies lies in the selection of individuals participating in the mutation, such that the mutation diversity of the population remains high and, at the same time, the mutated individuals are likely to approach optimal areas fast [11,12,15,16,20]. To this end, researchers have developed a number of individual selection approaches, especially for choosing guiding exemplars to direct the mutation of individuals [14,15,16,17,18]. Among these selection strategies, fitness values of individuals are commonly used to choose guiding exemplars to direct the evolution of the population [16,17,18,19,20]. To enhance the mutation diversity, researchers have also designed many other measures to select promising individuals to mutate the population, for example, cosine similarity [26], novelty of individuals [23], fitness and diversity contribution of individuals [27], and consecutive unsuccessful updates of individuals [25].

The above DE variants commonly utilize only one single mutation strategy to mutate all individuals. Nevertheless, different mutation strategies usually have different advantages in solving different optimization problems. Therefore, some researchers have even proposed to employ multiple mutation strategies to evolve the population, such that the strengths of different mutation schemes can be integrated to mutate the population effectively [28,29,30,31,32]. In a broad sense, the hybridization of multiple mutation strategies is classified into two major methods, namely, population-level hybridization [28,29,31,32,33,34] and individual-level hybridization [30,35,36,37,38]. In the former category of hybrid DE variants [31,33,34], in each generation, a mutation strategy is selected from the mutation strategy pool and then all individuals share this strategy to mutate. In contrast, in the latter category of hybrid DE variants [12,36,38], at each iteration, for each individual, a mutation scheme is selected from the mutation strategy pool to update the individual.

In addition to the mutation operation, the optimization performance of DE is also significantly influenced by the control parameters associated with the mutation operation and the crossover operation, that is, the scaling factor, F, in the mutation and the crossover probability, CR, in the crossover [35,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. It has been experimentally verified that on the one hand, the settings of these two key parameters are usually different for the same DE in different optimization problems; on the other hand, even in the same optimization problem, the settings of these two parameters are also usually different for DE with different mutation or crossover schemes [35,41,43,44]. This indicates that DE is very sensitive to these two parameters when solving optimization problems.

To alleviate this issue, researchers have been dedicated to devising adaptive parameter adjustment strategies for DE. As a result, many adaptive parameter adaptation methods have been developed to change the settings of F and CR dynamically during the evolution process [35,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Broadly speaking, existing parameter adaptation strategies can be divided into two main categories, namely, (1) dynamic parameter adjustment strategies [39,40,41,42] and (2) self-adaptive parameter adjustment strategies [35,43,44,45,46]. In general, the former type of parameter adaptation schemes mainly adjust the parameter values dynamically without considering the evolutionary states of the population or individuals [39,40,41,42], while the latter type of parameter adaptation methods usually take the evolutionary information or states of individuals into consideration to adaptively adjust the values of the two parameters [35,43,44,45,46].

Though many novel mutation strategies and effective parameter adaptation methods have been designed to help DE improve its optimization performance, DE still cannot find satisfactory solutions to complex optimization problems with lots of local regions because of the stagnation of the population [2,3,5,6,7]. However, with the rapid development of big data and the Internet of Things, optimization problems are becoming more and more complex due to the increasing variables, especially the increasingly correlated ones [47,48,49,50,51]. As a result, there is an increasing demand for effective strategies to further improve the optimization ability of DE in solving complicated optimization problems.

To this end, this paper devises a dual elite groups-guided mutation strategy called “DE/current-to-duelite/1” to effectively mutate all individuals in the population. As a result, a novel DE variant named dual elite groups-guided DE (DEGGDE) is developed for solving complex optimization problems. The contributions of this paper and the key components of DEGGDE are summarized as follows:

(1) A dual elite groups-guided mutation strategy named “DE/current-to-duelite/1” is proposed to mutate individuals with high diversity. Instead of only using the elites in the current population as the guiding exemplars to direct the mutation of individuals in existing studies [46], DEGGDE maintains an archive to store obsolete parent individuals and then assembles the elites in both the current population and the archive to guide the mutation of all individuals in the population. In this way, the diversity of the guiding exemplars used to mutate individuals is expectedly enlarged, and thus the mutation diversity of individuals is enhanced. This is beneficial for individuals to explore the solution space in diverse directions and aids in avoiding falling into local regions.

(2) A directional random difference vector is further proposed to accelerate the approaching speed to optimal areas. Instead of directly using two random individuals from the population to generate a completely random difference vector for mutating each individual, as in most existing studies [45,46,52,53,54], DEGGDE first compares the two randomly selected individuals from the population and then uses the better one as the first exemplar and the worse one as the second exemplar to generate a directional random difference vector for each individual to mutate. In this manner, the mutated individual is expected to move toward optimal areas fast.

With the above techniques, DEGGDE is anticipated to keep a good balance between search diversity and search convergence to explore and exploit the solution space to find the global optimum. To validate its effectiveness, experiments are conducted on the commonly used CEC’2017 benchmark set [55] with different dimension sizes by comparing DEGGDE with eleven state-of-the-art DE methods. In addition, the effectiveness of the above two components in DEGGDE are also studied by conducting experiments on the CEC’2017 benchmark set.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, the basic working principle of DE is first reviewed and then DE variants closely related to this paper are reviewed. After that, the devised DEGGDE is elaborated in detail in Section 3. Subsequently, a large number of experiments are carried out to verify the effectiveness of DEGGDE by comparing with eleven state-of-the-art DE variants in Section 4. Finally, conclusions are given in Section 5.

2. Related Work

This paper aims at minimization problems, which are formulated with the following general form:

where D is the number of variables to be optimized and x is a feasible solution to the optimization problem, which contains D elements. It is worth noting that we directly use the function value to evaluate the fitness of each individual in DE. Therefore, the smaller the fitness value of an individual is, the better it is.

2.1. Differential Evolution

The main idea of DE is to maintain a population of individuals to iteratively explore and exploit the solution space to find the global optimum of the optimization problem. During the iteration, individuals are updated sequentially by three operators, namely, mutation, crossover, and selection [2,3,4,5,6]. As a whole, the overall pseudo-code of DE is shown in Algorithm 1, where the following four steps are mainly involved:

(1) Initialization: In the initial stage, individuals in the population are randomly initialized. When solving continuous optimization problems, individuals are usually randomly initialized in the following way [4,5,6,7]:

where xi,j,0 is the value of the jth dimension for the ith individual in the 0th generation; and , with PS denoting the population size and D denoting the dimension size of the optimization problem. is a real random number generator to sample a real value uniformly within [0,1]. xj_max and xj_min represent the upper and the lower bounds of the jth dimension, respectively.

In the above manner, individuals in DE in the initial stage are expectedly dispersed in diverse areas of the solution space, which they can then search in distinct directions [19,22,23,24,25].

(2) Mutation: Mutation generates a mutation vector for each individual based on the difference vectors between individuals in the population [16,17,18,19,20]. It mainly generates new values for the population to create the offspring. Therefore, it has a significant effect on the optimization performance of DE. As a consequence, researchers have developed numerous mutation strategies for DE [11,12,13,14,15]. Some typical examples are listed below, with other recent ones reviewed in the next subsection:

DE/rand/1 [1]:

DE/best/1 [56]:

DE/current-to-best/1 [57]:

DE/current-to-rand/1 [52]:

DE/current-to-pbest/1 [46]:

where F is the scaling factor used to control the shifting of the base individual based on the difference vectors. is the mutation vector corresponding to the ith individual of the Gth generation, ; are the index values of three different individuals randomly chosen from the population, and ; is the best individual in the current population; is a randomly selected individual from the best ⌈p% × PS⌉ individuals in the Gth population; is a randomly selected individual from P∪A, where P denotes the current population and A represents one archive that stores the out-of-date parents, which are replaced by their offspring.

| Algorithm 1: The pseudocode of DE (DE/rand/1/bin) |

| Input: Population size PS, Scaling factor F, Crossover rate CR, Maximum fitness evaluations FESmax; |

|

| Output: f(x) and x |

(3) Crossover: Crossover creates an offspring for each individual by recombining the dimensions of the individual and those of its mutation vector generated by the mutation operation [45,46,52,53,54]. The most widely utilized crossover scheme is the binomial crossover [44]. It principally works as follows:

where CR is the crossover probability within [0,1]. It mainly determines the difference between the generated offspring and the associated parent individual; represents a randomly chosen dimension from all dimensions. It is used to ensure that the generated offspring, , is different from the parent individual, , in at least one dimension. As a whole, from (8), it is seen that if the randomly generated real value by is less than CR or j = , the value of the jth dimension in the mutation vector, , is assigned to the associated dimension of the offspring, ; otherwise, the value of the dimension in the parent individual, , is assigned to the dimension of . Therefore, the binomial crossover treats each dimension independently [34,37,58,59,60].

(4) Selection: After the generation of the offspring, the selection operation is performed to compare the offspring with the parent individuals to determine which one should enter the next iteration. In the literature, the most widely used selection method is the greedy strategy based on fitness [16,29,61,62,63], which works as follows:

where is the objective function of the optimization problem. In this selection strategy, each offspring is compared with its parent and the better one with a smaller function value goes into the next generation. Therefore, the selection strategy in (9) is suitable for DE to solve minimization problems.

As shown in Algorithm 1, individuals in the population are continuously updated with the mutation, the crossover, and the selection operations until the termination condition is satisfied. In the literature, the most widely used termination condition is when the afforded number of fitness evaluations runs out [27,64,65,66,67]. After the termination, DE outputs the found best solution.

2.2. Research on DE

Though the classical DE algorithm shown in Algorithm 1 has gained promising performance in solving simple optimization problems, such as low-dimensional unimodal problems [11,12,14,15,17], it encounters effectiveness degeneration when dealing with complicated optimization problems, such as high-dimensional multimodal problems with lots of local areas. To address the above predicament, researchers have been dedicated to advancing DE in the following two major directions.

2.2.1. Research on Mutation

The mutation operation in DE mainly imports new values into the population. Therefore, it significantly affects the performance of DE. As a result, numerous excellent mutation schemes have sprung up in recent decades [13,14,15,31,34]. Comprehensively speaking, existing mutation schemes are mainly categorized into two principal types, namely, the single mutation framework [11,12,14,15,17] and the multiple mutation strategies ensemble framework [28,30,31,32,34].

Researchers’ attention has been primarily focused on developing a uniform mutation scheme for all individuals to evolve. The key to this usually lies in the selection of parent individuals participating in the mutation operation [16,19,23,24,25]. At first, researchers focused on employing topologies to organize individuals and then selecting parents based on the adopted topology structures to direct the mutation of each individual [11,12,15]. To name a few representative ones, in [12], a random triangular topology-based mutation was proposed by first randomly choosing three individuals and then using the convex combination of the three difference vectors among the three individuals to mutate each individual. Combined with some basic mutation strategies and a restart mechanism, this mutation scheme helps DE solve optimization problems very effectively. In [11], cellular topology was used to organize individuals. Then, for each individual, the directional information among its neighbors determined by the topology was fully utilized to direct the mutation of this individual. In this manner, this mutation scheme tends to exploit the areas of better individuals with the help of the directional neighborhood information, which may accelerate the convergence of DE. Tian et al. [15] first used ring topology to build a promising individual group and then adaptively selected an individual from the group to direct the mutation of each individual based on its neighborhood performance. In this manner, the neighborhood information of each individual is considered to direct its mutation, which is beneficial for DE to properly adjust the search behavior of each individual during evolution. Since different topologies usually have different strengths in helping DE solve optimization problems, some researchers have attempted to assemble multiple topologies to design mutation strategies. For instance, Sun et al. [14] hybridized multiple topologies with different connectivity degrees and further designed an adaptive topology selection scheme to select a proper topology for each individual to form its neighbors by considering its evolutionary state.

Besides topology-based individual selection, researchers have also developed many other individual selection mechanisms. For instance, Gong et al. [17] proposed a fitness ranking-based individual selection strategy. They first ranked individuals from the best to the worst in terms of their fitness values and then assigned each individual a selection probability calculated by its fitness ranking. After that, they utilized the roulette wheel method to select the guiding exemplar for each individual to direct its mutation. In [19], a multi-objective sorting-based individual selection mechanism was proposed by first using the non-dominated sorting scheme to sort individuals based on their fitness values and their diversity contribution. After that, individuals participating in the mutation of each individual are selected by the roulette wheel method with the selection probabilities computed on the basis of the rankings in terms of fitness and diversity. In this way, during the individual selection, both fitness and diversity are considered and thus a promising balance between exploration and exploitation is potentially obtained. In [23], a novelty hybrid fitness individual selection mechanism was devised by introducing a new measure called novelty. Specifically, for each individual, its fitness value and novelty value are weighted together by two adaptive scaling parameters and then its selection probability is calculated by the weighted measurement. In this way, a good tradeoff between exploration and exploitation is expectedly achieved. In [25], an individual selection mechanism based on the number of consecutive unsuccessful updates was devised. To be specific, the selection probability of each individual is calculated based on the number of its consecutive unsuccessful updates. Then, the base individual and the terminal individual in the mutation operation are randomly selected by the roulette selection strategy based on the calculated probabilities.

To enhance the mutation diversity and efficiency, researchers have also attempted to incorporate historical evolutionary information into the mutation process. For example, Ghosh et al. [16] archived difference vectors which helped to generate successful offspring to replace their associated parents in past generations and then reused them in the subsequent generations to mutate individuals. In this way, promising directions for generating promising offspring could be made full use of to mutate individuals efficiently. Zhao et al. [30] proposed a “Top–Bottom” strategy that uses historical heuristic information derived from successful individuals and failed individuals to guide the mutation of the population. To be concrete, an archive is maintained to store failed individuals and cooperates with the population to assist individuals to evolve.

The above single mutation frameworks have assisted DE in gaining promising performance in solving different kinds of optimization problems. However, it has been found that different mutation strategies usually have different advantages and strengths in solving different types of optimization problems. Therefore, a natural thought is to assemble multiple mutation strategies to incorporate their strengths together to effectively cope with optimization problems. Along this road, researchers have devised a lot of ensemble methods to hybridize multiple mutation schemes [28,29,30,32]. In the case of hybridizing multiple mutation strategies, existing ensemble methods can be roughly classified into the following two main categories:

(1) Population-level ensemble methods. In this kind of ensemble method, all individuals share the same mutation scheme to evolve. For instance, Tan et al. [31] proposed an adaptive mutation ensemble method based on the fitness landscape of optimization problems. To be specific, they first trained a random forest algorithm to find the relationship between three mutation strategies and the fitness landscape of different optimization problems. Then, for each optimization problem, they used the trained model to select an appropriate mutation scheme from the mutation pool to help DE solve this problem. Gao et al. [29] proposed the use of multiple mutation schemes to generate multiple temporary mutation vectors for each individual, and then they further combined the generated multiple mutation vectors by weights to form the final mutation operator. Das et al. [34] proposed the use of two kinds of neighborhood models to generate a local mutation vector and a global mutation vector for each individual. Then, they combined the two mutation vectors by using a weight factor to form the final mutation vector. In [33], an improved version was further proposed by using five different pairs of global and local mutation models to generate five pairs of mutation vectors. Then, these mutation vectors were weighted together by an adaptive weighting strategy. Zhou et al. [36] proposed an underestimation-based ensemble method. To be concrete, for each individual, multiple mutation strategies are conducted to generate a set of offspring and then a cheap abstract convex underestimation model was used to select the most promising offspring to compare with the associated parent. To enhance mutation diversity, some researchers have proposed to divide the whole population into several sub-populations and then, for each sub-population, a mutation strategy is selected from the mutation pool to mutate all individuals in the sub-population. For instance, Cai et al. [28] proposed a cluster-based mutation strategy that involves two main levels of evolutionary information exchange. To be specific, the whole population is divided into clusters by the k-means algorithm. Then, an intra-cluster learning strategy and an inter-cluster learning strategy are designed to exchange information within the same cluster and between different clusters, respectively. Xia et al. [32] proposed a fitness-based adaptive mutation selection method by first dividing the whole population into multiple small subpopulations and then adaptively selecting a suitable mutation scheme from three popular mutation strategies for each sub-population to mutate its individuals based on the characteristics of all individuals in the subpopulation.

(2) Individual-level ensemble methods. In this kind of ensemble method, a suitable mutation scheme is adaptively selected for each individual. Therefore, different individuals may be mutated by different mutation schemes. For instance, Liu et al. [35] maintained a mutation pool containing three mutation strategies and then selected a mutation scheme for each individual based on its historical evolutionary experience and its heuristic information. Mohammad et al. [30] maintained three mutation strategies, namely, representative-based mutation, local random-based mutation, and global best history-based mutation. Then, they assigned each individual a mutation scheme adaptively through a winner-based allocation strategy.

Although the above DE variants using different mutation strategies have shown good performance in tackling certain kinds of optimization problems, their effectiveness still encounters great challenges when dealing with complex optimization problems. Therefore, improving the optimization effectiveness of DE in coping with complicated optimization problems is still an urgent demand. To this end, this paper aims to propose a simple yet effective dual elite groups-guided mutation strategy to help DE search the problem space with high effectiveness and high efficiency.

2.2.2. Research on Parameter Adaptation

Besides the mutation operation, two key control parameters, namely, the scaling factor, F, and the crossover rate, CR, also significantly influence the optimization performance of DE [40,41,42,43,45]. This means that DE is very sensitive to these two parameters. To alleviate this predicament, researchers have designed many parameter adaptation methods for the two key parameters. Broadly speaking, existing parameter adaptation approaches can be roughly divided into the following two categories:

(1) Dynamic parameter adaptation strategies. In this type of parameter adaptation strategy, the settings of the two key parameters are adjusted dynamically as the evolution continues, without considering the evolutionary states of individuals or the population [40,41,42]. To name a few representatives, in [40], two dynamic methods for setting F were proposed, namely, the random generation method and the time-varying method. In particular, the former randomly samples a value for F from the range (0.5, 1) with a uniform distribution, while the latter linearly decreases F over a specified interval. In [41], the value of F for each individual is randomly sampled by a normal distribution, N(0.5, 0.3). In [42], a sinusoidal function with respect to the number of generations was used to generate the values of F and CR.

(2) Self-adaptive parameter adaptation strategies. In this type of parameter adaptation strategy, parameter values are updated adaptively by using the evolutionary information of the population or individuals. For instance, in [35], the authors utilized the historical experience of the entire population and the heuristic information of each individual to adaptively adjust the settings of F and CR for this individual. Tang et al. [43] proposed an individual-dependent parameter adaptation strategy by using the fitness rankings or the fitness values of individuals. In [46], the settings of F and CR are generated randomly based on the Gaussian distribution and the Cauchy distribution, respectively. However, the mean value of the Gaussian distribution and the position parameter of the Cauchy distribution are adaptively adjusted based on those F and CR values associated with successful individuals. Inspired by this idea, researchers have developed many improved versions, among which the most representative one is the parameter adaptation strategy proposed in SHADE [45].

Specifically, SHADE maintains an archive called MF to store the mean value computed on the basis of the successful F values and another archive called MCR to store the mean value calculated on the basis of the successful CR values. The sizes of the two archives are both H. In the initial stage, each element (MCRi, and MFi (i = 1,..., H)) in the two archives is initialized as 0.5. Then, in each generation, a random index, ri, is uniformly chosen from [1, H] and then the settings of Fi and CRi for each individual are randomly generated as follows:

where is the selected element from MF to generate the setting of Fi for each individual, while is the selected element from MCR to generate the setting of CRi for each individual. is the Cauchy distribution with the position parameter set as and the scaling factor set as 0.1, while is the Gaussian distribution with the mean value set as and the deviation set as 0.1. When generating CRi, if it is not within [0,1], it is regenerated until the generated value falls into the range. When generating Fi, if , it is regenerated until ; if , it is truncated to 1.0.

During the update of individuals, if the generated offspring is better than its parent, the associated Fi and CRi are recorded into SF and SCR, respectively. Then, after the update of the whole population in each generation, the oldest elements in MF and MCR are updated in the following manner:

where and are the two sets used to record the Fi and CRi values associated with the offspring which successfully replace their parents. represents the fitness improvement of the offspring as compared with its parent. With this adaptive strategy, SHADE obtains very promising performance in solving optimization problems [45].

Except for the above typical parameter adaptation strategies, researchers have also proposed many other individual-level parameter adaptation schemes. To list some representatives, in [68], Li et al. adjusted the values of F and CR associated with each individual based on fitness improvement. To be concrete, for each individual, if the associated F and CR values cooperate with the mutation strategy to create a better trial vector, such settings of F and CR are still used in the next generation. On the contrary, if such values of F and CR fail to help the mutation strategy to create a better offspring in many consecutive iterations, they are then randomly regenerated. In [69], the authors took advantage of the Gaussian distribution, the Cauchy distribution, and a triangular wave function to randomly sample three groups of values for F and CR, respectively. Then, they selected the proper settings of F and CR for each individual based on the evolutionary information of this individual. In [70], a parameter adaptation scheme was devised by making full use of the population feature information. Specifically, the standard deviation of the fitness values of all individuals, the sum of the standard deviation with respect to each dimension of all individuals, and the successful F and CR values are considered to adaptively regulate the settings of F and CR.

The above parameter adaptation methods have been widely incorporated into different DE variants to help them achieve good optimization performance in dealing with various optimization problems [2,3,4]. Since the focus of this paper is to design a novel mutation scheme, we directly take advantage of the parameter adaptation approach in SHADE [45] to cooperate with the devised DEGGDE to solve optimization problems.

3. Proposed DEGGDE

Although many advanced DE methods have been proposed in recent years, the performance of DE is still not as satisfactory as we had anticipated it would be when it encounters complex optimization problems with many local basins. Nevertheless, in the era of big data and the Internet of Things, variables likely correlate with each other and, consequently, optimization problems become more and more complicated [55,71,72]. Confronted with such problems, designing effective mutation schemes is the key to improving the optimization effectiveness of DE. To this end, this paper develops a simple, yet effective mutation scheme called “DE/current-to-duelite/1”, which is elucidated in detail in the following.

3.1. DE/Current-to-Duelite/1

In the research on evolutionary algorithms, it has been widely recognized that elite individuals usually preserve more valuable evolutionary information to guide the population to approach optimal areas [51,73,74]. Therefore, elites are widely utilized to direct the update of individuals. Nevertheless, most existing studies only make use of elites in the current population to assist the evolution of the population. Such utilization may limit the diversity of the guiding exemplars, with the result that individuals in the population are guided in limited directions.

To enhance the diversity of the guiding exemplars, we turn to the historical evolutionary information of the population to seek some useful elite individuals. Along this road, we design a novel mutation scheme called “DE/current-to-duelite/1” for DE by assembling historical elite individuals to guide the mutation of the population.

Specifically, given that the population size is PS, we maintain an archive (denoted as A) of the same size (namely PS) to store the obsolete parent individuals. Then, unlike existing mutation strategies [11,12,13,14,15], which only utilize elite individuals in the current population as the candidate guiding exemplars to direct the mutation of the population, we utilize the elite individuals in both the current population and the archive to direct the mutation of the population. To be concrete, we select the best [p1*PS] (p1 is actually the percentage of the number of the chosen elite individuals out of the whole population) individuals in the current population to form the elite set, denoted as PE. Then, we further select the best [p2*PS] (p2 is actually the percentage of the number of the chosen elite individuals out of the entire archive) individuals in the archive to form the elite set, denoted as AE. As a result, PE∪AE constitutes the candidate guiding exemplars for mutating individuals in the population.

In particular, each individual in the population is mutated by the devised “DE/current-to-duelite/1” as follows:

where is an elite individual randomly selected from PE∪AE to direct the mutation of ; is the ith individual in the Gth generation; . is the generated mutant vector; is the scaling factor associated with ; and and are two individuals randomly selected from P∪A by the uniform distribution, where P and A denote the current population and the archive, respectively. It is worth noting that r1 ≠ r2 ≠ i.

Another thing that should be noted is that, instead of using a completely random difference vector like most existing mutation mechanisms, “DE/current-to-duelite/1” utilizes a directional random difference vector. To be concrete, “DE/current-to-duelite/1” first randomly chooses two different individuals from P∪A and then lets the better one between the two selected individuals act as while the worse one acts as . In this way, the difference vector between the two random individuals is directional from the worse individual to the better individual.

Observing Equation (17), we find that the devised “DE/current-to-duelite/1” could help DEGGDE strive a good balance between exploration of the problem space and exploitation of the found promising areas due to the following reasons:

(1) The elite individual set PE∪AE provides diverse candidate-guiding exemplars for individuals to mutate. On the one hand, the introduction of the elite individuals in the archive storing historical evolutionary information affords additional leading exemplars for individuals to mutate. This largely improves the mutation diversity of individuals and thus is of great profit for individuals to traverse the problem space in diverse directions. On the other hand, the elite individuals in both PE and AE are expectedly better than most individuals in the current population, P. Therefore, it is hoped that most individuals are likely guided to move towards optimal regions. From this perspective, it is highly possible that individuals can approach optimal areas fast.

(2) The selection of two random individuals, and , from P∪A further enhances the mutation diversity of individuals. Specifically, instead of selecting the two random individuals only from P, “DE/current-to-duelite/1” randomly selects both of the random individuals from P∪A. This largely promotes the diversity of the random difference vectors of all individuals. Consequently, the search diversity of DEGGDE is improved greatly, which is highly beneficial for escaping from local areas.

(3) The directional random difference vector affords great assistance for individuals to move towards optimal regions fast. Instead of using completely random difference vectors for all individuals, “DE/current-to-duelite/1” utilizes a directional random difference vector for each individual by letting the better one between the two selected random individuals act as the first exemplar and the worse one act as the second exemplar. In this way, individuals are expectedly mutated in promising directions. This is of considerable benefit for individuals to find promising areas fast.

With the above mechanisms, DEGGDE is anticipated to strike a very promising balance between exploration and exploitation to traverse the problem space sufficiently. Aside from the above techniques for mutation, another two key techniques should also be paid careful attention.

In the initial stage, we set archive A as empty. During evolution, the obsolete parents are sequentially added into A. When the number of individuals exceeds its fixed size, PS, we randomly select an individual from A and then compare it with the obsolete parent to be added. If the obsolete parent is better than the randomly selected individual, it replaces the individual; otherwise, it is discarded. In this way, on the one hand, high diversity can be maintained in A; on the other hand, the quality of individuals in A can also be ensured. This updating mechanism of A also potentially assists DEGGDE to maintain a good compromise between search diversity and search convergence.

For the settings of p1 and p2, p2 determines the number of the elite individuals in A, while p1 determines the number of the elite individuals in P. Since A stores the obsolete parents, theoretically, it is highly possible that the overall quality of individuals in A is worse than that of individuals in P. Thus, the number of elite individuals in A should be smaller than that in P. For convenience, in this paper, we set p2 = p1/2, leading to the number of the elite individuals in A being only half of that in P.

Subsequently, upon deeper analysis of p1, we find that a large p1 results in that a large number of elite individuals participating in the mutation of the population. This improves the search diversity of DEGGDE. Nevertheless, a too-large p1 may lead to too-high search diversity, which may do harm to the convergence of DEGGDE. In contrast, a small p1 leads to only a few elite individuals taking part in the mutation of the population. This is beneficial for fast convergence of the population to optimal areas, but it may result in low mutation diversity and then to low search diversity, which may bring stagnation of the population. From the above analysis, we find that a fixed p1 is not suitable for DEGGDE to achieve satisfactory performance.

For ease and convenience, we propose a dynamic strategy for setting p1 to alleviate the above predicament. To be concrete, at each generation, we randomly sample a value for p1 from [0.1, 0.2] by the uniform distribution. In this way, on the one hand, the sensitivity of DEGGDE to p1 could be alleviated; on the other hand, a dynamic balance between exploration and exploitation can be maintained by DEGGDE. This endows DEGGDE with a good capability of searching the problem space diversely while at the same time refining the quality of the found optimal solutions.

It should be mentioned that the range of [0.1, 0.2] is used here because the devised “DE/current-to-duelite/1” can be actually seen an extension of the mutation strategy “DE/current-to-pbest/1” in JADE [46]. Therefore, we directly borrow the recommended setting range of p in JADE to randomly sample a value for p1 in this paper.

3.2. Difference between “DE/Current-to-Duelite/1” and Existing Similar Mutation Strategies

In the literature, many existing mutation strategies also utilize elite individuals to direct the mutation of the population [46,57,73,74], such as “DE/current-to-best/1” [57] and “DE/current-to-pbest/1” [46]. Compared with these existing mutation schemes, “DE/current-to-duelite/1” differs from them mainly in the following aspects:

(1) The most significant difference between “DE/current-to-duelite/1” and existing elite-guided mutation strategies lies in the dual elite groups guided mutation mechanism. Most existing studies only use the elite individuals in the current population to direct the mutation of all individuals. Nevertheless, in “DE/current-to-duelite/1”, the elite individuals in the current population and those in the archive are used together to direct the evolution of all individuals. Therefore, compared with most existing mutation schemes, “DE/current-to-duelite/1” possesses more candidate guiding exemplars and thus preserves higher mutation diversity. Such utilization of historical evolutionary information, by focusing on the best historical individuals, provides strengthens DEGGDE in locating optimal regions fast.

(2) The second significant difference between “DE/current-to-duelite/1” and existing mutation strategies lies in the selection of two random individuals and the construction of the random difference vector. Most existing mutation strategies choose the two random individuals from the population, whereas “DE/current-to-duelite/1” selects the two random individuals from P∪A. This selection mechanism affords a high diversity of random difference vectors and thus is very beneficial for improving the search diversity of DEGGDE, which may greatly benefit the population in avoiding being trapped in local zones. In addition, unlike most existing mutation schemes that use completely random difference vectors, “DE/current-to-duelite/1” utilizes a directional random difference vector by taking the better one between the two random individuals as the first exemplar while taking the worse one as the second exemplar. By this means, it is expected that the directional random difference vectors could provide positive and promising directions for individuals to mutate. As a result, slightly faster convergence of the population to optimal regions could be achieved.

3.3. The Complete DEGGDE

In addition to “DE/current-to-duelite/1”, this paper employs the binomial crossover scheme to combine the target vector and the corresponding mutation vector to generate the final offspring. With the aim of reducing the sensitivity to the control parameters F and CR, DEGGDE adopts the widely used individual-level parameter adaptation strategy in SHADE [45] to generate the settings of the two parameters for each individual. However, a small modification is made to the CR settings. To be concrete, this paper first generates a set of CR values for all individuals and then sorts them from the smallest to the largest. Subsequently, in the crossover operation, we assign smaller CR values to better individuals. In this way, the generated offspring of the better individuals preserve smaller differences with their parents; in contrast, the generated offspring of the worse individuals preserve larger differences with their parents. As a result, better individuals can focus on exploiting the optimal areas they locate while worse individuals concentrate on exploring the problem space to find more promising areas. For all these techniques, the pseudocode of the complete DEGGDE is outlined in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2: The pseudocode of DEGGDE |

| Input: Population size PS, Maximum fitness evaluations FESmax; |

|

| Output: f(gbest) and gbest |

In the initial phase, as shown in lines 1–2, PS individuals are randomly initialized and then evaluated. Along with the initialization of the population, the related archives for the parameter adaptation and mutation are also initialized. Subsequently, the algorithm enters the main loop. At first, as shown in line 5, the value of p1 is randomly generated according to the uniform distribution, and then the value of p2 is computed. After that, as shown in line 6, individuals in the current population, P, and those in the archive, A, are sorted from the best to the worst, respectively. Then, as shown in line 7, the elite sets PE and AE are formed by selecting the best [p1*PS] in P and the best [p2*PS] in A, respectively. Subsequently, a set of F values and a set of CR values are randomly generated based on the Cauchy distribution and the Gaussian distribution, respectively (line 8). After that, the set of CR values is sorted from the smallest to the largest (line 9). After the above preparations, the evolution of all individuals begins as shown in lines 10–27. To update each individual, the associated CR value is first obtained according to its fitness ranking, as shown in line 11. Then, one elite individual is randomly selected from PE∪AE (line 12). Next, two random individuals are selected from P∪A (line 13). After that, the devised mutation scheme is performed to mutate the individual (line 14), following which the binomial crossover operation generates the final offspring, as shown in line 15. Afterwards, the offspring is evaluated and the records in the relevant archives are updated along with the selection operation (lines 16–26). The above operations are performed iteratively until the termination condition is satisfied, which is commonly the completion of the maximum number of fitness evaluations. Finally, before the termination of the algorithm, the found optimal solution and its fitness value are output.

Without considering the time for fitness evaluations, at each generation, it takes O(PS × logPS) to sort individuals in P and another O(PS × logPS) to sort individuals in A. To generate two sets of values for F and CR, respectively, it requires O(PS) twice. To sort the set of CR values, it requires O(PS × logPS). Then, O(PS × D) is required to generate the offspring for all individuals. In the selection process, O(PS × D) is required twice for updating the population, P, and the archive, A. Finally, O(PS) is needed for parameter adaptation. As a whole, the overall time complexity of DEGGDE is O(PS × logPS + PS × D), which does not impose a serious burden as compared with the time complexity of the classical DE.

4. Experiments

This section comprehensively verifies the effectiveness of DEGGDE in tackling optimization problems by conducting a large number of experiments. To start with, the experimental setup is first introduced, including the used benchmark problem set, the selected state-of-the-art algorithms for comparisons, and their parameter settings. Next, the performance of DEGGDE is extensively compared with the methods in the benchmark set. Finally, in-depth observation on DEGGDE is carried out by validating the usefulness of the designed mutation scheme and the devised parameter adaptation strategy.

4.1. Experimental Setup

In the experiments, we use the CEC’2017 benchmark set, which has been widely used to test the optimization performance of evolutionary algorithms [75,76,77,78], to demonstrate the effectiveness and efficiency of DEGGDE. This set consists of 29 numerical optimization problems, which are classified into four different types. Specifically, F1 and F3 are unimodal optimization problems, F4–F10 are multimodal optimization problems, F11–F20 are hybrid optimization problems, and F21–F30 are composition optimization problems. Brief information about these 29 problems is listed in Table 1, and more detailed information can be referred to in [55]. To comprehensively verify the effectiveness of DEGGDE, we set three different dimensionalities, namely, 30D, 50D, and 100D, for all the CEC’2017 benchmark problems.

Table 1.

Summarized information of the CEC’2017problems.

To make comparisons with DEGGDE, eleven representative and advanced DE variants are selected, namely, SHADE [45], GPDE [79], DiDE [80], SEDE [81], FADE [32], FDDE [27], TPDE [69], NSHADE [53], CUSDE [25], PFIDE [70], and EJADE [54].

Similar to the devised DEGGDE, SHADE, NSHADE, DiDE, FDDE, and CUSDE adopt a single mutation framework to mutate individuals. Specifically, SHADE utilizes “DE/current-to-pbest/1” to mutate individuals with an adaptive strategy for F and CR [45]. Such an adaptive strategy is also used in the devised DEGGDE to mutate individuals. Therefore, SHADE is selected as a baseline method to compare with DEGGDE. NSHADE is the latest improvement on SHADE with a new parameter adaptation scheme based on the nearest spatial neighborhood information [53]. DiDE employs an extension of “DE/current-to-pbest/1” to mutate individuals by introducing an external archive based on depth information. For the parameter adaptation of F and CR, it divides the population into several groups and separately adjusts the settings of F and CR for individuals in different groups adaptively [80]. FDDE utilizes a new mutation operator to mutate the population by selecting parental individuals based on their probabilities, which are computed on the basis of both fitness rankings and diversity rankings of individuals [27]. CUSDE uses the number of consecutive unsuccessful updates to calculate the selection probability of each individual and then chooses the base individual and the terminal individuals by the roulette wheel selection method. Inferior individuals with a large number of consecutive unsuccessful updates are removed during the evolution [25].

Unlike the above methods, GPDE, SEDE, FADE, TPDE, and EJADE assemble multiple mutation strategies to mutate different individuals distinctly. In particular, GPDE assembles a newly designed Gaussian distribution-based mutation operator and “DE/rand-worst/1” to mutate each individual adaptively. Then, a cosine function is employed to sample F and a Gaussian distribution is used to sample CR dynamically in GPDE [79]. SEDE hybridizes three different mutation strategies to mutate individuals adaptively by controlling the proportion of individuals where each mutation strategy is performed to get the associated mutation vector [81]. FADE first divides the population into several sub-populations and then adaptively selects a mutation strategy from three mutation candidates for each individual to mutate based on its fitness [32]. TPDE first separates the population into three sub-populations according to the newly designed zonal-constraint stepped division mechanism and then employs three elite-guided mutation operations to mutate individuals in the three sub-populations, respectively. Then, it leverages the Gaussian distribution, the Cauchy distribution, and a triangular wave function to generate F and CR for individuals in the three sub-populations, respectively [69]. EJADE assembles two sets of integrated crossover and mutation operations to create promising offspring [54].

Different from the above 10 compared DE methods, PFIDE develops a parameter adaptation framework for DE. Specifically, it takes advantage of population feature information, such as the summation of the standard deviation values with respect to each dimension of all individuals in the population and the standard deviation in terms of the fitness values of all individuals, to allocate historical successful F and CR values with high similarity measured by the population feature to the current population [70].

To ensure fair comparisons, for those compared algorithms which were also tested on the CEC’2017 benchmark set with three settings of dimensionality, we directly adopt the recommended settings of the population size in the associated papers for them. For those compared methods which were not tested on the CEC’2017 benchmark set, we fine-tuned the population size, PS, for them for CEC’2017 problems with the three dimensionality settings. The specific settings of the population size for all algorithms to solve the CEC’2017 problems with the three settings of dimensionality are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

The optimal PS settings of all algorithms for the 30D, 50D, and 100D CEC’2017 sets.

Unless otherwise stated, the maximum number of fitness evaluations for all algorithms is set as 10,000*D, with D denoting the dimension size. For fairness, we run each algorithm 30 times independently on each benchmark problem and then use the mean and the standard deviation values to evaluate the optimization performance of each algorithm on each benchmark problem. To make statistical difference, the Friedman test at the significance level α = 0.05 is performed to get the average rank of each algorithm with respect to the overall performance on one whole benchmark set. In addition, the Wilcoxon rank sum test at the significance level α = 0.05 is also performed to compare the optimization result of DEGGDE with that of each compared method on each benchmark problem. The symbols “+”, “=”, and “−” at the upper right corner of each p-value in the tables indicate that DEGGDE obtains significantly better, equivalent, and significantly worse performance than the compared method on the corresponding problem, respectively. “w/t/l” in the tables count the numbers of “+”, “=”, and “−”, respectively.

Finally, it deserves mentioning that DEGGDE is implemented in Python and all experiments are executed on the same PC with four Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-3470 3.20 GHz CPUs, 4Gb RAM, and the Ubuntu 12.04 LTS 64-bit system.

4.2. Comparisons between DEGGDE and State-of-the-Art DE Methods on the CEC’2017 Set

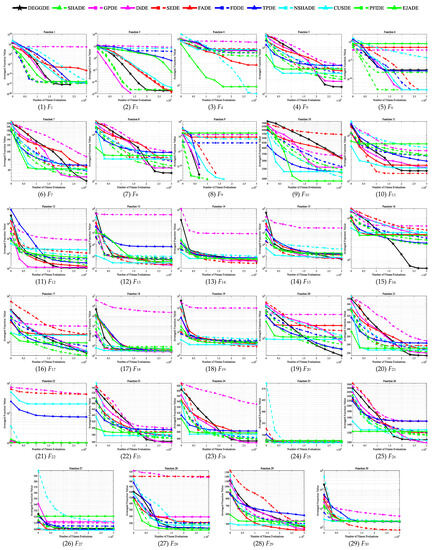

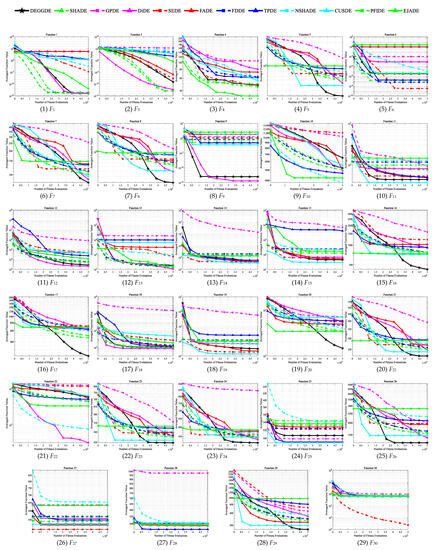

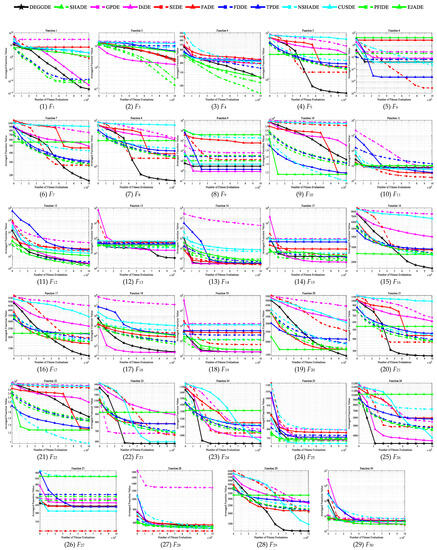

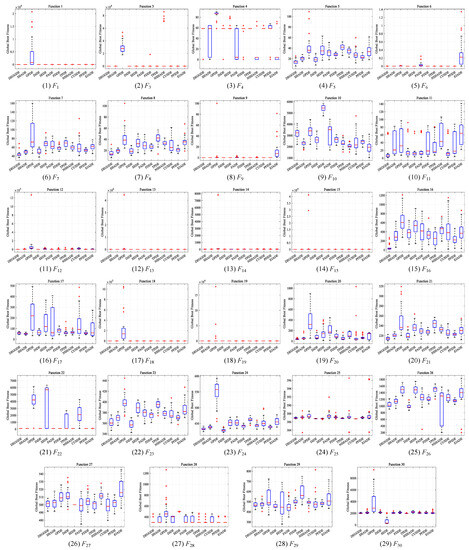

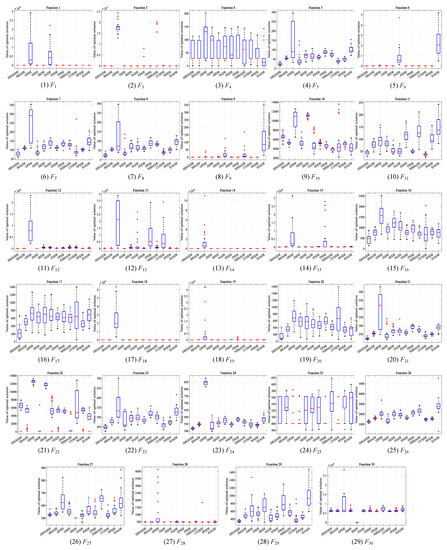

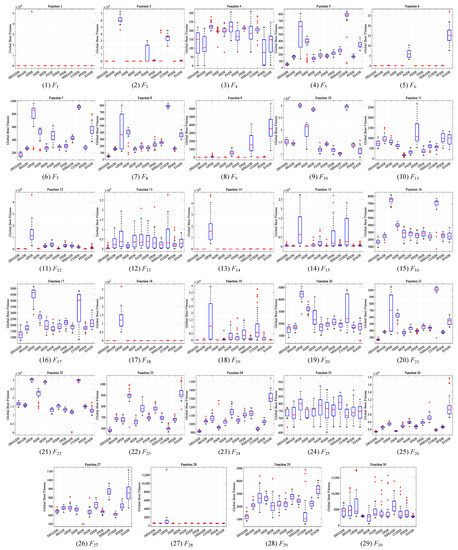

This section compares DEGGDE with the selected eleven state-of-the-art DE variants on the CEC’2017 benchmark set with three dimensionality settings, namely, 30D, 50D, and 100D. With the settings of the population size for all algorithms listed in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 show the detailed optimization performance of all algorithms and their comparisons on the 30D, 50D, and 100D CEC’2017 benchmark sets, respectively. For better comparisons, we summarize the statistical comparison results in terms of “w/t/l” and the average rank “Rank” in Table 6. Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the convergence behaviors of all algorithms on the 30D, 50D, and 100D CEC’2017 benchmark sets, respectively. In addition, following the guideline in [82], we also present the box-plot diagrams of the global best fitness values obtained by DEGGDE and the eleven compared DE variants in the thirty independent runs on the 30D, 50D, and 100D CEC’2017 benchmark sets in Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6, respectively. In these figures, the rectangular box shows the distribution of the global best fitness values obtained in the thirty runs by quartiles. The horizontal line inside the rectangular box represents the median value of the thirty data. The upper and the lower boundaries of the rectangular box represent the upper and the lower quartiles of the thirty data, respectively. The top and the bottom extended lines out of the rectangular box represent the maximum and the minimum values among the thirty data, respectively. The symbol “+” represents the outlier values among the thirty data.

Table 3.

Comparison results between DEGGDE and the eleven state-of-the-art DE variants on the 30D CEC’2017 benchmark functions.

Table 4.

Comparison results between DEGGDE and the eleven state-of-the-art DE variants on the 50D CEC’2017 benchmark functions.

Table 5.

Comparison results between DEGGDE and the eleven state-of-the-art DE variants on the 100D CEC’2017 benchmark functions.

Table 6.

Summarized comparison results between DEGGDE and the eleven compared algorithms with respect to “w/t/l” derived from the Wilcoxon rank sum test and the average rank obtained from the Friedman test on the 30D, 50D, and 100D CEC’2017 benchmark sets.

Figure 1.

Convergence behaviors of DEGGDE and the eleven compared DE variants on the 30D CEC’2017 set.

Figure 2.

Convergence behaviors of DEGGDE and the eleven compared DE variants on the 50D CEC’2017 set.

Figure 3.

Convergence behaviors of DEGGDE and the eleven compared DE variants on the 100D CEC’2017 set.

Figure 4.

Box-plot diagrams of the global best fitness values obtained by DEGGDE and the eleven compared DE variants in the thirty independent runs on the 30D CEC’2017 set.

Figure 5.

Box-plot diagrams of the global best fitness values obtained by DEGGDE and the eleven compared DE variants in the thirty independent runs on the 50D CEC’2017 set.

Figure 6.

Box-plot diagrams of the global best fitness values obtained by DEGGDE and the eleven compared DE variants in the thirty independent runs on the 100D CEC’2017 set.

Making deep and close observations on the above figures and tables, we gain the following findings:

(1) From the Friedman test results, on the one hand, DEGGDE consistently ranks in first place for the 30D, 50D, and 100D CEC’2017 benchmark sets. This demonstrates that DEGGDE obtains the best overall optimization performance among all algorithms. Furthermore, the rank value of DEGGDE is much smaller than those of the eleven compared methods on the three CEC’2017 benchmark sets. This reveals that DEGGDE shows significant superiority to the eleven compared methods in solving optimization problems.

(2) From the “w/t/l” derived from the Wilcoxon rank sum test, we find that with increasing dimensionality, DEGGDE achieves better and better optimization performance than the eleven compared methods. Specifically, on the 30D CEC’2017 benchmark set, DEGGDE obtains significantly better performance than the eleven compared algorithms on at least ten problems. In particular, it significantly outperforms six compared methods (namely, SHADE, GPDE, FDDE, TPDE, NSHADE and EJADE) on more than twenty problems. On the 50D CEC’2017 benchmark sets, DEGGDE achieves significantly better performance than the eleven compared methods on at least fifteen problems. Particularly, it shows significant superiority to nine compared methods (namely, SHADE, GPDE, SEDE, FADE, FDDE, TPDE, NSHADE, PFIDE, and EJADE) on more than twenty problems. On the 100D CEC’2017 set, DEGGDE is significantly superior to the eleven compared methods on more than eighteen problems. In particular, it performs significantly better than seven compared methods (namely, GPDE, FADE, FDDE, NSHADE, CUSDE, PFIDE, and EJADE) on more than twenty problems.

(3) With respect to the optimization performance on different types of optimization problems, we find that DEGGDE is particularly good at solving complex optimization problems, such as multimodal problems, hybrid problems, and composition problems. Specifically, (a) in the two unimodal problems (F1 and F3), DEGGDE shows significantly better performance for both problems than seven, eight, and six compared methods on the 30D, 50D, and 100D CEC’2017 benchmark sets, respectively. (b) On the seven multimodal problems (F4–F10), DEGGDE achieves increasingly better performance as the dimensionality increases. On the 30D multimodal problems, DEGGDE presents significant dominance over the eleven compared methods on at least three problems and only shows failures to them on, at most, three problems. In particular, it is significantly better than five compared methods on more than five problems. On the 50D multimodal problems, DEGGDE significantly outperforms the eleven compared methods on four problems and only fails the competition with them on, at most, two problems. Particularly, it is significantly superior to five compared methods on more than five problems. On the 100D multimodal problems, DEGGDE performs significantly than the eleven compared methods on more than four problems and only shows inferiority to them on, at most, three problems. Particularly, it is significantly better than nine compared methods on more than five problems. (c) On the ten hybrid problems (F11–F20), DEGGDE also shows increasingly better performance with increasing dimensionality. Specifically, DEGGDE performs significantly better on more than seven problems than seven, nine, and nine compared methods on the 30D, 50D, and 100D CEC’2017 benchmark sets, respectively. (d) On the ten composition problems (F21–F30), DEGGDE also consistently achieves significantly better performance than most of the eleven compared algorithms. Specifically, it shows significant dominance on more than six problems compared to ten, nine, and nine other methods on the 30D, 50D, and 100D CEC’2017 benchmark sets, respectively.

(4) In terms of the convergence behavior comparisons between DEGGDE and the eleven compared methods shown in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3, we find that DEGGDE achieves much faster convergence speed along with much better solutions than most of the eleven compared methods. Specifically, on the 30D CEC’2017 benchmark set, DEGGDE obtains the best performance in terms of both the solution quality and the convergence speed among all methods on eight problems (F1, F5, F7–F8, F12, F16, F20–F21). On the 50D CEC’2017 benchmark set, DEGGDE achieves the fastest convergence speed and the best solutions among all algorithms on eleven problems (F5, F7–F8, F16–F17, F20–F21, F23–F24, F26, F29). On the 100D CEC’2017 benchmark set, DEGGDE performs the best with respect to both the convergence speed and the solution quality among all approaches on thirteen problems (F1, F5, F7–F8, F13, F16–F17, F20–F21, F23–F24, F26, F29).

(5) With respect to the box-plot diagrams shown in Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6, we find that DEGGDE achieves much more stable performance than the eleven compared methods. It was also found that the overall quality of the global optima found by DEGGDE in the thirty independent runs is much better than most of the eleven compared methods. Specifically, on the 30D CEC’2017 benchmark set, the distribution of the global best fitness values obtained by DEGGDE is more centered around a better optimum than the eleven compared methods on eighteen problems (F1, F3, F5–F9, F11–16, F18–F19, F21–F22, F28), which indicates its superior and stable performance. On the 50D CEC’2017 benchmark set, the distribution of the global best fitness values obtained by DEGGDE is more centered around a better optimum than the eleven compared methods on twenty problems (F1, F3, F5–F9, F12, F14–F21, F23–F24, F26, F29). On the 100D CEC’2017 benchmark set, the distribution of the global best fitness values obtained by DEGGDE is more centered around a better optimum than the eleven compared methods on eighteen problems (F1, F3, F5–F8, F12–F14, F16–F19, F21, F23–F24, F26, F29).

Above all, the above extensive comparisons between DEGGDE and the eleven compared methods demonstrate that DEGGDE preserves high effectiveness and efficiency in solving optimization problems. DEGGDE also performs very stably. In particular, it is good at solving complex optimization problems, such as multimodal problems, hybrid problems, and composition problems.

4.3. Deep Investigation on the Effectiveness of “DE/Current-to-Duelite/1”

In this section, we conduct experiments to verify the effectiveness of the devised “DE/current-to-duelite/1”. To this end, we develop several variants of “DE/current-to-duelite/1”.

First, in the designed mutation scheme, we utilize the elite individuals in both the population and the archive to direct the mutation of individuals. To demonstrate the effectiveness of this scheme, we only utilize the elite individuals in the population to guide the mutation of the population, developing a variant of “DE/current-to-duelite/1”, which is denoted as “DE/current-to-Pelite/1”. Similarly, we also only utilize the elite individuals in the archive to direct the mutation of the population, developing another variant of “DE/current-to-duelite/1”, which is denoted as “DE/current-to-Aelite/1”.

Second, as for the directional random difference vector in the devised mutation scheme, unlike existing studies, we randomly choose two random individuals from P∪A for each individual to be mutated and then take the better one as while taking the worse one as . In this way, the generated mutation vector expectedly moves towards the optimal areas fast. To demonstrate the effectiveness of this method of generating the random difference vector, we also develop several variants of “DE/current-to-duelite/1”. Firstly, we remove the directional scheme, taking the better one as while taking the worse one as , and thus develop a variant of “DE/current-to-duelite/1”, which is represented as “DE/current-to-duelite/1-WD”. Subsequently, instead of choosing the two random individuals both from P∪A, we randomly choose one random individual from P and another random individual from P∪A. Without the directional scheme between the two randomly selected individuals, we develop a variant of “DE/current-to-duelite/1”, which is denoted as “DE/current-to-duelite/1-PWD”. Along with the directional scheme, we develop another variant of “DE/current-to-duelite/1”, which is represented as “DE/current-to-duelite/1-PD”.

After the above preparation, we conducted experiments on the 50D CEC’2017 benchmark set to compare the original “DE/current-to-duelite/1” with the developed five variants. Table 7 presents the comparison results. In this table, the Friedman test is performed to get the average rank of each variant of “DE/current-to-duelite/1”. The Wilcoxon rank sum test is also performed to compare the original “DE/current-to-duelite/1” with each of the developed versions on each benchmark problem. According to the results of this test, “w/t/l” in this table counts the number of problems where “DE/current-to-duelite/1” is significantly better than, equivalent with, and significantly worse than the corresponding developed versions, respectively. From this table, we gain the following findings:

Table 7.

Comparison results among DEGGDE variants with different mutation schemes on the 50D CEC’2017 benchmark set.

(1) Regarding the Friedman test, DEGGDE with “DE/current-to-duelite/1” ranks first among all versions of DEGGDE. This means that “DE/current-to-duelite/1” helps DEGGDE achieve the best overall performance on the 50D CEC’2017 benchmark set. Additionally, the rank value of “DE/current-to-duelite/1” is much smaller than the other versions. This reveals that “DE/current-to-duelite/1” shows significant superiority to the other versions.

(2) From the perspective of “w/t/l”, we find that DEGGDE with “DE/current-to-duelite/1” performs significantly better than DEGGDE with the other versions on more than ten problems and only shows inferior performance to them on no more than three problems. In particular, compared with “DE/current-to-Pelite/1” and “DE/current-to-Aelite/1”, “DE/current-to-duelite/1” achieves significantly better performance on fourteen and twenty-one problems, respectively. This proves the great effectiveness of using both the elite individuals in the population and the ones in the archive to direct the mutation of the population. Compared with “DE/current-to-duelite/1-WD”, “DE/current-to-duelite/1” significantly outperforms it on eleven problems. This illustrates the effectiveness of the directional random difference vector in the devised mutation scheme, i.e., taking the better one between the two randomly selected individuals as , and taking the worse one as . Furthermore, “DE/current-to-duelite/1” significantly outperforms “DE/current-to-duelite/1-PD” and “DE/current-to-duelite/1-PWD” on ten and nineteen problems, respectively. This demonstrates the great effectiveness of selecting the two random individuals both from P∪A.

The above experimental results have demonstrated the great effectiveness of the devised mutation scheme, namely “DE/current-to-duelite/1”. In particular, the dual elite groups, namely the elite individuals in the current population and those in the archive, provide diverse yet promising guiding exemplars to lead the mutation of individuals. This not only affords great help in diversity enhancement, but also offers great assistance in convergence acceleration. Together with the directional random difference vector, the devised mutation scheme provides directional guidance for individuals to approach optimal areas fast.

5. Conclusions

This paper has devised a dual elite groups-guided differential evolution (DEGGDE) by designing a novel mutation scheme, called “DE/current-to-duelite/1”. To make full use of the historical evolutionary information, this mutation scheme maintains an archive to store the obsolete parent individuals and then utilizes the elite individuals in both the current population and the archive as the candidate guiding exemplars to direct the mutation of the population. In this way, the diversity of the leading exemplars could be largely enhanced, which is beneficial for individuals to search the problem space diversely. In addition, to accelerate the convergence of DEGGDE, instead of generating the random difference vector in the mutation scheme completely randomly, we propose to generate a directional random difference vector for the devised mutation scheme by first randomly selecting two individuals from the combination of the current population and the archive and then taking the better one as the first exemplar and the worse one as the second exemplar. In this way, the directional random difference vector provides a promising direction for the mutated individual to move towards optimal areas. With the collaboration between the two main techniques, DEGGDE is expected to strike a good balance between exploration and exploitation and thus is anticipated to achieve promising performance in solving optimization problems.

Extensive experiments have been executed on the CEC’2017 benchmark set with three different settings of dimensionality (namely 30D, 50D, and 100D). The experimental results have shown that, compared with eleven state-of-the-art DE variants, DEGGDE obtains significantly better performance than them in solving the 30D, 50D, and 100D CEC’2017 problems. In particular, DEGGDE shows good capability in coping with complex optimization problems, such as multimodal optimization problems, hybrid optimization problems, and composition optimization problems. Additionally, the effectiveness of the devised mutation scheme and the dynamic adjustment of the number of elite individuals has also been verified.

In the current version of DEGGDE, we dynamically adjust the number of elite individuals without considering the evolutionary state of the population. In the future, to further improve the optimization performance of DEGGDE, we aim to devise an adaptive adjustment strategy for this parameter by taking into account the evolutionary information of individuals and the evolutionary state of the population. Another future direction is to employ DEGGDE to solve practical optimization problems in both academic and engineering applications, such as path planning of unmanned aerial vehicles [83], automatic machine learning [84], control parameter optimization in wireless power transfer systems [85], expensive optimization [86], and optimization problems relevant to social networks [87].

Author Contributions

T.-T.W.: Implementation, formal analysis, and writing—original draft preparation. Q.Y.: Conceptualization, supervision, methodology, formal analysis, and writing—original draft preparation. X.-D.G.: Methodology, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62006124 and in part by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province under Project BK20200811.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Storn, R.; Price, K. Differential evolution—A simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. J. Glob. Optim. 1997, 11, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, D.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Jeon, S.-W.; Zhang, J. Proximity ranking-based multimodal differential evolution. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2023, 78, 101277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; He, H.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Jeon, S.-W.; Zhang, J. Function value ranking aware differential evolution for global numerical optimization. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2023, 78, 101282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Yan, J.-Q.; Gao, X.-D.; Xu, D.-D.; Lu, Z.-Y.; Zhang, J. Random neighbor elite guided differential evolution for global numerical optimization. Inf. Sci. 2022, 607, 1408–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Xing, L.; Zheng, X.; Du, N.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Q. A self-adaptive differential evolution algorithm for scheduling a single batch-processing machine with arbitrary job sizes and release times. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 51, 1430–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Pi, D.; Wu, Z.; Chen, J.; Zio, E. Hybrid discrete differential evolution and deep q-network for multimission selective maintenance. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2022, 71, 1501–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, Q.; Pan, N.; Sun, Y.; An, Y.; Pan, D. Uav stocktaking task-planning for industrial warehouses based on the improved hybrid differential evolution algorithm. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brest, J.; Maučec, M.S.; Bošković, B. Single objective real-parameter optimization: Algorithm jso. In Proceedings of the IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, Donostia, Spain, 5–8 June 2017; pp. 1311–1318. [Google Scholar]

- Awad, N.H.; Ali, M.Z.; Suganthan, P.N. Ensemble sinusoidal differential covariance matrix adaptation with euclidean neighborhood for solving cec2017 benchmark problems. In Proceedings of the IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, Donostia, Spain, 5–8 June 2017; pp. 372–379. [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe, R.; Fukunaga, A.S. Improving the search performance of shade using linear population size reduction. In Proceedings of the IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, Beijing, China, 6–11 July 2014; pp. 1658–1665. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, J.; Cai, Y.; Wang, T.; Tian, H.; Chen, Y. Cellular direction information based differential evolution for numerical optimization: An empirical study. Soft Comput. 2016, 20, 2801–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.W. An improved differential evolution algorithm with triangular mutation for global numerical optimization. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2015, 85, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opara, K.; Arabas, J. Comparison of mutation strategies in differential evolution—A probabilistic perspective. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2018, 39, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Cai, Y.; Wang, T.; Tian, H.; Wang, C.; Chen, Y. Differential evolution with individual-dependent topology adaptation. Inf. Sci. 2018, 450, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Gao, X.; Yan, X. Performance-driven adaptive differential evolution with neighborhood topology for numerical optimization. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 188, 105008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Das, S.; Das, A.K.; Gao, L. Reusing the past difference vectors in differential evolution—A simple but significant improvement. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2020, 50, 4821–4834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Cai, Z. Differential evolution with ranking-based mutation operators. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2013, 43, 2066–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Gao, J. High-dimensional waveform inversion with cooperative coevolutionary differential evolution algorithm. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2012, 9, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liao, J.; Zhou, Y.; Cai, Y. Differential evolution enhanced with multiobjective sorting-based mutation operators. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2014, 44, 2792–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Gong, W.; Liao, Z.; Wang, L. Hybrid niching-based differential evolution with two archives for nonlinear equation system. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2022, 52, 7469–7481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.X.; Yang, Q.; Gao, X.D. Gaussian sampling guided differential evolution based on elites for global optimization. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 80915–80944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, N.M.; Essam, D.L.; Sarker, R.A. Constraint consensus mutation-based differential evolution for constrained optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2016, 20, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Tong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, X.; Yang, H.; Gui, L.; Li, Y.; Li, K. Nfdde: A novelty-hybrid-fitness driving differential evolution algorithm. Inf. Sci. 2021, 579, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Xu, G.; Rui, L.; Liu, D.; Liu, H.; Yuan, J. A failure remember-driven self-adaptive differential evolution with top-bottom strategy. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2019, 45, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Pan, Z.; Gao, Z.; Gao, J. Improving the search accuracy of differential evolution by using the number of consecutive unsuccessful updates. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 250, 109005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Wu, D.; Zhou, Y.; Fu, S.; Tian, H.; Du, Y. Self-organizing neighborhood-based differential evolution for global optimization. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2020, 56, 100699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]