Abstract

In the first part of this article, we discuss and generalize the complete convergence introduced by Hsu and Robbins in 1947 to the r-complete convergence introduced by Tartakovsky in 1998. We also establish its relation to the r-quick convergence first introduced by Strassen in 1967 and extensively studied by Lai. Our work is motivated by various statistical problems, mostly in sequential analysis. As we show in the second part, generalizing and studying these convergence modes is important not only in probability theory but also to solve challenging statistical problems in hypothesis testing and changepoint detection for general stochastic non-i.i.d. models.

Keywords:

complete convergence; r-quick convergence; sequential analysis; hypothesis testing; changepoint detection MSC:

60F15; 60G35; 60G40; 60J05; 62L10; 62C10; 62C20; 62F03; 62H15; 62M02; 62P30

1. Introduction

In [1], Hsu and Robbins introduced the notion of complete convergence which is stronger than almost sure (a.s.) convergence. Hsu and Robbins used this notion to discuss certain aspects of the law of large numbers (LLN). In particular, let be independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) random variables with the common mean . Hsu and Robbins proved that, while in Kolmogorov’s strong law of large numbers (SLLN), only the first moment condition is needed for the sample mean to converge to as , the complete version of the SLLN requires the second-moment condition (finiteness of variance). Later, Baum and Katz [2], working on the rate of convergence in the LLN established that the second-moment condition is not only necessary but also sufficient for complete convergence. Strassen [3] introduced another mode of convergence, the r-quick convergence. When , these two modes of convergence are closely related. In the case of i.i.d. random variables and the sample mean , they are identical. This fact and certain statistical applications motivated Tartakovsky [4] (see also Tartakovsky [5] and Tartakovsky et al. [6]) to introduce a natural generalization of complete convergence—the r-complete convergence, which turns out to be identical to the r-quick convergence in the i.i.d. case.

The goal of this overview paper is to discuss the importance of quick and complete convergence concepts for several challenging statistical applications. These modes of convergence are discussed in detail in the first part of this paper. Statistical applications, which constitute the second part of this paper, include such fields as sequential hypothesis testing and changepoint detection in general non-i.i.d. stochastic models when observations can be dependent and highly non-stationary. Specifically, in the second part, we first address near optimality of Wald’s sequential probability ratio test (SPRT) for testing two hypotheses regarding the distributions of non-i.i.d. data. We discuss Lai’s results in his fundamental paper [7], which was the first publication that used the r-quick convergence of the log-likelihood ratio processes to establish the asymptotic optimality of the SPRT as probabilities of errors go to zero. We then go on to tackle the much more difficult multi-decision problem of testing multiple hypotheses and show that certain multi-hypothesis sequential tests asymptotically minimize moments of the stopping time distribution up to the order r when properly normalized log-likelihood ratio processes between hypotheses converge r-quickly or r-completely to finite positive numbers. These results can be established based on the former works of the author (see, e.g., Tartakovsky [4,5] and Tartakovsky et al. [6]). The second challenging application is the quickest change detection when it is necessary to detect a change that occurs at an unknown point in time as rapidly as possible. We show, using the works of the author (see, e.g., [5,6] and the references therein), that certain popular changepoint detection procedures such as CUSUM, Shiryaev, and Shiryaev–Roberts procedures are asymptotically optimal as the false alarm rate is low when the normalized log-likelihood ratio processes converge r-completely to finite numbers.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses pure probabilistic issues related to r-complete convergence and r-quick convergence. Section 3 explores statistical applications in sequential hypothesis testing and changepoint detection. Section 4 outlines sufficient conditions for the r-complete convergence for Markov and hidden Markov models, which is needed to establish the optimality properties of sequential hypothesis tests and changepoint detection procedures. Section 5 provides a final discussion and concludes the paper.

2. Modes of Convergence and the Law of Large Numbers

We begin by listing some standard definitions in probability theory. Let be a measurable space, i.e., is a set of elementary events and is a sigma-algebra (a system of subsets of satisfying standard conditions). A probability space is a triple , where is a probability measure (completely additive measure normalized to 1) defined on the sets from the sigma-algebra . More specifically, by Kolmogorov’s axioms, probability satisfies: for any ; ; and for , , , where ⌀ is an empty set.

A function defined on with values in is called a random variable if it is -measurable, i.e., belongs to the sigma-algebra . The function is the distribution function of X. It is also referred to as a cumulative distribution function (cdf). The real-valued random variables are independent if the events are independent for every sequence of real numbers. In what follows, we shall deal with real-valued random variables unless specified otherwise.

2.1. Standard Modes of Convergence

Let X be a random variable and let () be a sequence of random variables, both defined on the probability space . We now give several standard definitions and results related to the law of large numbers.

().

Let be the cdf of and let be the cdf of X. We say that the sequence converges to X in distribution (or in law or weakly) as and write if

at all continuity points of .

.

We say that the sequence converges to X in probability as and write if

.

We say that the sequence converges to X almost surely (a.s.) or with probability 1 (w.p. 1) as under probability measure and write if

It is easily seen that (1) is equivalent to the condition

and that the a.s. convergence implies convergence in probability, and the convergence in probability implies convergence in distribution, while the converse statements are not generally true.

The following double implications that establish necessary and sufficient conditions (i.e., equivalences) for the a.s. convergence are useful:

The following result is often useful.

Lemma 1.

Let be a non-negative increasing function, . If

then

Proof.

For any , and , we have

Letting and taking into account that

we obtain

Since can be arbitrarily large, we can let and since, by assumption, , it follows from (2) that the upper bound approaches 0 as . This completes the proof. □

.

Let be i.i.d. random variables with the mean for and the initial condition . Then, is called a random walk with the mean .

In what follows, in the case where are i.i.d. random variables and , we prefer to formulate the results in terms of the random walk (typically but not necessarily ).

We now recall the two strong law of large numbers (SLLN). Write for the partial sum (), so that is a random walk with an initial condition of zero as long as are i.i.d. with mean .

.

Let be a random walk under probability measure . If exists, then the sample mean converges to the mean value w.p. 1, i.e.,

Conversely, if , where , then .

.

Let be a zero-mean random walk under probability measure . The two following statements are equivalent:

- (i)

- for ;

- (ii)

- .

2.2. Complete and r-Complete Convergence

We begin with discussing the issue of rates of convergence in the LLN.

.

Let be a sequence of random variables and assume that converges to 0 w.p. 1 as . The question asks what the rate of convergence is. In other words, we are concerned with the speed at which the tail probability decays to zero. This question can be answered by analyzing the behavior of the sums

More specifically, if is finite for every , then the tail probability decays with a rate faster than , so that for all as .

To answer this question, we now consider modes of convergence that strengthen the almost sure convergence and therefore help determine the rate of convergence in the SLLN. Historically, this issue was first addressed in 1947 by Hsu and Robbins [1], who introduced the new mode of convergence which they called complete convergence.

.

The sequence converges to 0 completely if

which is equivalent to

Let be a random walk with a mean of . Kolmogorov’s SLLN (4) implies that the sample mean converges to w.p. 1. Hsu and Robbins [1] proved that, under the same assumptions (i.e., under the only first-moment condition ) the sequence does not need to completely converge to , but it will do so under the further second-moment condition . Thus, the finiteness of variance is a sufficient condition for complete convergence in the SLLN. They conjectured that the second-moment condition is not only sufficient but also necessary for complete convergence. Thus, it follows from these results that, if the variance is finite, then the rate of convergence in Kolmogorov’s SLLN is for all .

In 1965, Baum and Katz [2] made a further step towards this issue. In particular, the following result follows from Theorem 3 in [2] for the zero-mean random walk .

Theorem 1.

Let and . If is a zero-mean random walk, then the following statements are equivalent:

Setting and in (6), we obtain the following equivalence

which shows that the conjecture of Hsu and Robbins is correct—the second-moment condition is both necessary and sufficient for complete convergence

Furthermore, if for some , the -th moment is finite, , then the rate of convergence in the SLLN is for all .

Previous results suggest that it is reasonable to generalize the notion of complete convergence into the following mode of convergence that we will refer to as r-complete convergence, which is also related to the so-called r-quick convergence that we will discuss later on (see Section 2.3).

Definition 1 (r-Complete Convergence).

Let . We say that the sequence of random variables converges to X as r-completely under probability measure and write if

Note that the a.s. convergence of to X can be equivalently written as

so that the r-complete convergence with implies the a.s. convergence, but the converse is not true in general.

Suppose that converges a.s. to X. If is finite for every , then

and probability goes to 0 as with the rate faster than . Hence, as already mentioned above, the r-complete convergence allows one to determine the rate of convergence of to X, i.e., to answer the question of how fast the tail probability decays to zero.

The following result provides a very useful implication of complete convergence.

Theorem 2.

Let and be two arbitrary, possibly dependent sequences of random variables. Assume that there are positive and finite numbers and such that

and

i.e., and . If , then for any random time T

Proof.

Fix , and let be the smallest integer that is larger than or equal to . Observe that

Thus, to prove (10), it suffices to show that the two terms on the right-hand side go to 0 as .

For the first term, we notice that, for any ,

so that

Since as , the upper bound goes to 0 as due to condition (8).

Next, since , there exists such that

As a result,

where the upper bound goes to 0 as by condition (9) (see Lemma 1). □

Remark 1.

Remark 2.

Theorem 2 can be applied to the overshoot problem. Indeed, if and the random time T is the first time n when exceeds the level b, , then Theorem 2 shows that the relative excess of boundary crossing (overshoot) converges to 0 in probability as when completely converges as to a positive number μ.

2.3. r-Quick Convergence

In 1967, Strassen [3] introduced the notion of r-quick limit points of a sequence of random variables. The r-quick convergence has been further addressed by Lai [7,8], Chow and Lai [9], Fuh and Zhang [10], and Tartakovsky [4,5] (see certain details in Section 2.4).

We define r-quick convergence in a way suitable for this paper. Let be a sequence of real-valued random variables and let X be a random variable defined on the same probability space .

Definition 2 (r-Quick Convergence).

Let and for , let

be the last entry time of in the region . We say that the sequence converges to X r-quickly as under the probability measure and write if and only if

where is the operator of expectation under probability .

This definition can be generalized to random variables X, taking values in a metric space with distance d: if

Note that the a.s. convergence () as to a constant can be expressed as , where . Therefore, the r-quick convergence implies the convergence w.p. 1 but not conversely.

Also, in general, r-quick convergence is stronger than r-complete convergence. Specifically, the following lemma shows that

Lemma 2.

Let be a sequence of random variables. Let be a non-negative increasing function, , , and let for

be the last time that leaves the interval .

- (i)

- For any and any , the following inequalities hold:

- (ii)

- If is a power function, , , then the finiteness of

Proof.

Proof of (i). Obviously,

from which the inequalities (13) follow immediately.

Proof of (ii). Write , where is a smallest integer greater or equal to u. We have the following chain of inequalities and equalities:

It follows that

which yields the implication (14) and completes the proof. □

The following theorem shows that, in the i.i.d. case, the implications in (12) become equivalences.

Theorem 3.

Let be a zero-mean random walk. The following statements are equivalent

2.4. Further Remarks on r-Complete Convergence, r-Quick Convergence, and Rates of Convergence in SLLN

Let be a random walk. Without loss of generality, let and .

- Strassen [3] proved, in particular, that if in Lemma 2, then for

- 2.

- Lai [8] improved this result, showing that Strassen’s moment condition for can be relaxed. Specifically, he showed that a weaker condition

- 3.

- Let and . Chow and Lai [9] established the following one-sided inequality for tail probabilities:

The results of Chow and Lai [9] provide one-sided analogues of the results of Baum and Katz [2] as well as extend their results. Indeed, the one-sided inequality (23) implies that the following statements are equivalent for the zero-mean random walk :

- (i)

- ;

- (ii)

- ;

- (iii)

- ,

where .

Clearly, the two-sided inequality (24) yields the assertions of Theorem 1.

- 4.

- The Marcinkiewicz–Zygmund SLLN states that, for , the following implications hold:

The strengthened r-quick equivalent of this SLLN is: for any and , the following statements are equivalent,

3. Applications of -Complete and -Quick Convergences in Statistics

In this section, we outline certain statistical applications which show the usefulness of r-complete and r-quick versions of the SLLN.

3.1. Sequential Hypothesis Testing

We begin by formulating the following multi-hypothesis testing problem for a general non-i.i.d. stochastic model. Let , be a filtered probability space with standard assumptions about the monotonicity of the sub--algebras . The sub--algebra of is assumed to be generated by the sequence observed up to time n, which is defined on the space . The hypotheses are , , where are given probability measures assumed to be locally mutually absolutely continuous, i.e., their restrictions and to are equivalent for all and all , . Let be a restriction to of a -finite measure Q on . Under , the sample has a joint density with respect to the dominating measure for all , which can be written as

where , are corresponding conditional densities.

For , define the likelihood ratio (LR) process between the hypotheses and

and the log-likelihood ratio (LLR) process

A multi-hypothesis sequential test is a pair , where T is a stopping time with respect to the filtration and is an -measurable terminal decision function with values in the set . Specifically, means that the hypothesis is accepted upon stopping, i.e., . Let , , denote the error probabilities of the test , i.e., the probabilities of accepting the hypothesis when is true.

Introduce the class of tests with probabilities of errors that do not exceed the prespecified numbers :

where is a matrix of given error probabilities that are positive numbers less than 1.

Let denote the expectation under the hypothesis (i.e., under the measure ). The goal of a statistician is to find a sequential test that would minimize the expected sample sizes for all hypotheses , at least approximately, say asymptotically for small probabilities of errors, i.e., as .

3.1.1. Asymptotic Optimality of Walds’s SPRT

First, assume that , i.e., that we are dealing with two hypotheses and . In the mid-1940s, Wald [11,12] introduced the sequential probability ratio test (SPRT) for the sequence of i.i.d. observations , in which case in (27) and the LR is

After n observations have been made, Wald’s SPRT prescribes for each :

where are two thresholds.

Let be the LLR for the observation , so the LLR for the sample is the sum

Let and . The SPRT can be represented in the form

In the case of two hypotheses, the class of tests (28) is of the form

That is, it includes hypothesis tests with upper bounds and on the probabilities of errors of Type 1 (false positive) and Type 2 (false negative) , respectively.

Wald’s SPRT has an extraordinary optimality property: it minimizes both expected sample sizes and in the class of sequential (and non-sequential) tests with given error probabilities as long as the observations are i.i.d. under both hypotheses. More specifically, Wald and Wolfowitz [13] proved, using a Bayesian approach, that if and thresholds and can be selected in such a way that and , then the SPRT is strictly optimal in class . A rigorous proof of this fundamental result is tedious and involves several delicate technical details. Alternative proofs can be found in [14,15,16,17,18].

Regardless of the strict optimality of SPRT which holds if and only if thresholds are selected so that the probabilities of errors of SPRT are exactly equal to the prescribed values , which is usually impossible, suppose that thresholds and are so selected that

Then

where and are Kullback–Leibler (K-L) information numbers so that the following asymptotic lower bounds for expected sample sizes are attained by SPRT:

(cf. [6]). Hereafter, .

The following inequalities for the error probabilities of the SPRT hold in the most general non-i.i.d. case

These bounds can be used to guarantee asymptotic relations (30).

In the i.i.d. case, by the SLLN, the LLR has the following stability property

This allows one to conjecture that, if in the general non-i.i.d. case, the LLR is also stable in the sense that the almost sure convergence conditions (33) are satisfied with some positive and finite numbers and , then the asymptotic formulas (31) still hold. In the general case, these numbers represent the local K-L information in the sense that often (while not always) and . Note, however, that in the general non-i.i.d. case, the SLLN does not even guarantee the finiteness of the expected sample sizes of the SPRT, so some additional conditions are needed, such as a certain rate of convergence in the strong law, e.g., complete or quick convergence.

In 1981, Lai [7] was the first to prove the asymptotic optimality of Wald’s SPRT in a general non-i.i.d. case as . While the motivation was the near optimality of invariant SPRTs with respect to nuisance parameters, Lai proved a more general result using the r-quick convergence concept.

Specifically, for and , define

() and suppose that () for some and every , i.e., that the normalized LLR converges r-quickly to under and to under :

Strengthening the a.s. convergence (33) into the r-quick version (34), Lai [7] established the first-order asymptotic optimality of Wald’s SPRT for moments of the stopping time distribution up to order r: If thresholds and in the SPRT are so selected that and asymptotics (30) hold, then as ,

Wald’s ideas have been generalized in many publications to construct sequential tests of composite hypotheses with nuisance parameters when these hypotheses can be reduced to simple ones by the principle of invariance. If is the maximal invariant statistic and is the density of this statistic under hypothesis , then the invariant SPRT is defined as in (29) with the LLR . However, even if the observations are i.i.d. the invariant LLR statistic is not a random walk anymore and Wald’s methods cannot be applied directly. Lai [7] has applied the asymptotic optimality property (35) of Wald’s SPRT in the non-i.i.d. case to investigate the optimality properties of several classical invariant SPRTs such as the sequential t-test, the sequential -test, and Savage’s rank-order test.

In the sequel, we will call the case where the a.s. convergence in the non-i.i.d. model (33) holds with the rate asymptotically stationary. Assume now that (33) is generalized to

where is a positive increasing function. If is not linear, then this case will be referred to as asymptotically non-stationary.

A simple example where this generalization is needed is testing versus regarding the mean of the normal distribution:

where is a zero-mean i.i.d. standard Gaussian sequence and is a polynomial of order . Then,

for a large n, so and in (36). This example is of interest for certain practical applications, in particular, for the recognition of ballistic objects and satellites.

Tartakovsky et al. ([6] Section 3.4) generalized Lai’s results for the asymptotically non-stationary case. Write for the inverse function of .

Theorem 4 (SPRT asymptotic optimality).

Let . Assume that there exist finite positive numbers and and an increasing non-negative function such that the r-quick convergence conditions

hold. If thresholds and are selected so that and and , then, as ,

This theorem implies that the SPRT asymptotically minimizes the moments of the stopping time distribution up to order r.

The proof of this theorem is performed in two steps which are related to our previous discussion of the rates of convergence in Section 2. The first step is to obtain the asymptotic lower bounds in class :

These bounds hold whenever the following right-tail conditions for the LLR are satisfied:

Note that, by Lemma 1, these conditions are satisfied when the SLLN (36) holds so that the almost sure convergence (36) is sufficient. However, as we already mentioned, the SLLN for the LLR is not sufficient to guarantee even the finiteness of the SPRT stopping time.

The second step is to show that the lower bounds are attained by the SPRT. To do so, it suffices to impose the following additional left-tail conditions:

for all . Since both right-tail and left-tail conditions hold if the LLR converges r-completely to ,

and since r-quick convergence implies r-complete convergence (see (12)), we conclude that the assertions (37) hold.

Remark 3.

In the i.i.d. case, Wald’s approach allows us to establish asymptotic equalities (37) with and being K-L information numbers under the only condition of finiteness . However, Wald’s approach breaks down in the non-i.i.d. case. Certain generalizations in the case of independent but non-identically and substantially non-stationary observations, extending Wald’s ideas, were considered in [19,20,21]. Theorem 4 covers all these non-stationary models.

Fellouris and Tartakovsky [22] extended previous results on the asymptotic optimality of the SPRT to the case of the multistream hypothesis testing problem when the observations are sequentially acquired in multiple data streams (or channels or sources). The problem is to test the null hypothesis that none of the N streams are affected against the composite hypothesis that a subset is affected. Write and for the distribution of observations and expectation under hypothesis . Let denote a class of subsets of that incorporates prior information which is available regarding the subset of affected streams, e.g., not more than streams can be affected. (In many practical problems, K is substantially smaller than the total number of streams N, which can be very large.)

Two sequential tests were studied in [22]—the generalized sequential likelihood ratio test and the mixture sequential likelihood ratio test. It has been shown that both tests are first-order asymptotically optimal, minimizing the moments of the sample size and for all up to order r as in the class of tests

The proof is essentially based on the concept of r-complete convergence of LLR with the rate . See also Chapter 1 in [5].

3.1.2. Asymptotic Optimality of the Multi-hypothesis SPRT

We now return to the multi-hypothesis model with that we started to discuss at the beginning of this section (see (27) and (28)). The problem of the sequential testing of many hypotheses is substantially more difficult than that of testing two hypotheses. For multiple-decision testing problems, it is usually very difficult, if even possible, to obtain optimal solutions. Finding an optimal non-Bayesian test in the class of tests (28) that minimizes expected sample sizes for all hypotheses , is not manageable even in the i.i.d. case. For this reason, a substantial part of the development of sequential multi-hypothesis testing in the 20th century has been directed towards the study of certain combinations of one-sided sequential probability ratio tests when observations are i.i.d. (see, e.g., [23,24,25,26,27,28]).

We will focus on the following first-order asymptotic criterion: Find a multi-hypothesis test such that, for some ,

where .

In 1998, Tartakovsky [4] was the first who considered the sequential multiple hypothesis testing problems for general non-i.i.d. stochastic models following Lai’s idea of exploiting the r-quick convergence in the SLLN for two hypotheses. The results were obtained for both discrete and continuous-time scenarios and for the asymptotically non-stationary case where the LLR processes between hypotheses converge to finite numbers with the rate . Two multi-hypothesis tests were investigated: (1) the rejecting test, which rejects the hypotheses one by one, and the last hypothesis, which is not rejected, is accepted; and (2) the matrix accepting test that accepts a hypothesis for which all component SPRTs that involve this hypothesis vote for accepting it.

We now proceed with introducing this accepting test which we will refer to as the matrix SPRT (MSPRT). In the present article, we do not consider the continuous-time scenarios. Those who are interested in continuous time are referred to [4,6,19,21,29].

Write . For a threshold matrix , with and the being immaterial (say 0), define the matrix SPRT , built on one-sided SPRTs between the hypotheses and , as follows:

and accept the unique that satisfies these inequalities. Note that, for , the MSPRT coincides with Wald’s SPRT.

In the following, we omit the superscript N in for brevity. Obviously, with , the MSPRT in (39) can be written as

Introducing the Markov accepting times for the hypotheses as

the test in (40), (41) can be also written in the following form:

Thus, in the MSPRT, each component SPRT is extended until, for some , all N SPRTs involving accept .

Using Wald’s likelihood ratio identity, it is easily shown that for , , so selecting implies that . These inequalities are similar to Wald’s ones in the binary hypothesis case and are very imprecise. In his ingenious paper, Lorden [27] showed that, with a very sophisticated design that includes the accurate estimation of thresholds accounting for overshoots, the MSPRT is nearly optimal in the third-order sense, i.e., it minimizes the expected sample sizes for all hypotheses up to an additive disappearing term: as . This result only holds for i.i.d. models with the finite second moment . In the non-i.i.d. case (and even in the i.i.d. case for higher moments ), there is no way to obtain such a result, so we focus on the first-order optimality (38).

The following theorem establishes asymptotic operating characteristics and the optimality of MSPRT under the r-quick convergence of to finite K-L-type numbers , where is a positive increasing function, .

Theorem 5 (MSPRT asymptotic optimality

[4]). Let . Assume that there exist finite positive numbers , , and an increasing non-negative function such that, for some ,

Then, the following assertions are true.

- (i)

- For ,

- (ii)

- If the thresholds are so selected that and , particularly as , then for all

Assertion (ii) implies that the MSPRT asymptotically minimizes the moments of the stopping time distribution up to order r for all hypotheses in the class of tests .

Remark 4.

Both assertions of Theorem 5 are correct under the r-complete convergence

i.e., when

While this statement has not been proven anywhere to date, it can be easily proven using the methods developed for multistream hypothesis testing and changepoint detection ([5] Ch 1, Ch 6).

Remark 5.

As shown in the example given in Section 3.4.3 of [6], the r-quick convergence conditions in Theorem 5 (or corresponding r-complete convergence conditions for LLR processes) cannot be generally relaxed into the almost sure convergence

However, the following weak asymptotic optimality result holds for the MSPRT under the a.s. convergence: if the a.s. convergence (47) holds with the power function , , then, for every ,

whenever thresholds are selected as in Theorem 5 (ii).

Note that several interesting statistical and practical applications of these results to invariant sequential testing and multisample slippage scenarios are discussed in Section 4.5 and 4.6 of Tartakovsky et al. [6] (see Mosteller [30] and Ferguson [16] for terminology regarding multisample slippage problems).

3.2. Sequential Changepoint Detection

Sequential (or quickest) changepoint detection is an important subfield of sequential analysis. The observations are made one at a time and as long as their behavior suggests that the process of interest is in control (i.e., in a normal state), the process is allowed to continue. If the state is believed to have lost control, the goal is to detect the change in distribution as rapidly as possible. Quickest change detection problems have an enormous number of important applications, e.g., object detection in noise and clutter, industrial quality control, environment surveillance, failure detection, navigation, seismology, computer network security, genomics, and epidemiology (see, e.g., [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]). Many challenging application areas are discussed in the books by Tartakovsky, Nikiforov, and Basseville ([6] Ch 11) and Tartakovsky ([5] Ch 8).

3.2.1. Changepoint Models

The probability distribution of the observations is subject to a change at an unknown point in time so that are generated by one stochastic model and are generated by another model. A sequential detection rule is a stopping time T for an observed sequence , i.e., T is an integer-valued random variable such that the event belongs to the sigma-algebra generated by observations .

Let denote the probability measure corresponding to the sequence of observations when there is never a change () and, for , let denote the measure corresponding to the sequence when . We denote the hypothesis that the change never occurs by and we denote the hypothesis that the change occurs at time by .

First consider a general non-i.i.d. model assuming that the observations may have a very general stochastic structure. Specifically, if we let, as before, denote the sample of size n, then when (there is no change), the conditional density of given is for all and when , then the conditional density is for and for . Thus, for the general non-i.i.d. changepoint model, the joint density under hypothesis can be written as follows

where is the pre-change conditional density and is the post-change conditional density which may depend on , , but we will omit the superscript for brevity.

The classical changepoint detection problem deals with the i.i.d. case where there is a sequence of observations that are identically distributed with a probability density function (pdf) for and with a pdf for . That is, in the i.i.d. case, the joint density of the vector under hypothesis has the form

Note that, as discussed in [5,6], in applications, there are two different kinds of changes—additive and non-additive. Additive changes lead to a change in the mean value of the sequence of observations. Non-additive changes are typically produced by a change in variance or covariance, i.e., these are spectral changes.

We now proceed by discussing the models for the change point . The change point may be considered either as an unknown deterministic number or as a random variable. If the change point is treated as a random variable, then the model has to be supplied with the prior distribution of the change point. There may be several changepoint mechanisms, and, as a result, a random variable may be dependent on or independent of the observations. In particular, Moustakides [41] assumed that can be a -adapted stopping time. In this article, we will not discuss Moustakides’s concept by allowing the prior distribution to depend on some additional information available to “Nature” (see [5] for a detailed discussion); rather, when considering a Bayesian approach, we will assume that the prior distribution of the unknown change point is independent of the observations.

3.2.2. Popular Changepoint Detection Procedures

Before formulating the criteria of optimality in the next subsection, we begin by defining the three most popular and common change detection procedures, which are either optimal or nearly optimal in different settings. To define these procedures, we need to introduce the partial likelihood ratio and the corresponding log-likelihood ratio

It is worth iterating that, for general non-i.i.d. models, the post-change density often depends on the point of change, , so in general and also depend on the change point . However, this is not the case for the i.i.d. model (50).

The CUSUM Procedure

We now introduce the Cumulative Sum (CUSUM) algorithm, which was first proposed by Page [42] for the i.i.d. model (50). Recall that we consider the changepoint detection problem as a problem of testing two hypotheses: that the change occurs at a fixed-point against the alternative that the change never occurs. The LR between these hypotheses is for and 1 for . Since the hypothesis is composite, we may apply the generalized likelihood ratio (GLR) approach maximizing the LR over to obtain the GLR statistic

It is easy to verify that this statistic follows the recursion

as long as the partial LR does not depend on the change point, i.e., the post-change conditional density does not depend on . This is always the case for i.i.d. models (50) when . However, as we already mentioned, for non-i.i.d. models, often depends on the change point , so , in which case the recursion (51) does not hold.

The logarithmic version of , , is related to Page’s CUSUM statistic introduced by Page [42] in the i.i.d. case as . The statistic can also be obtained via the GLR approach by maximizing the LLR over . However, since the hypotheses and are indistinguishable for , the maximization over does not make very much sense. Note also that, in contrast to Page’s CUSUM statistic , the statistic may take values smaller than 0, so the CUSUM procedure

makes sense even for negative values of the threshold a. Thus, it is more general than Page’s CUSUM. Note the recursions

and

in cases where does not depend on .

Shiryaev’s Procedure

In the i.i.d. case and for the zero-modified geometric prior distribution of the change point, Shiryaev [43] introduced the change detection procedure that prescribes the thresholding of the posterior probability . Introducing the statistic

one can write the stopping time of the Shiryaev procedure in the general non-i.i.d. case and for an arbitrary prior as

where A () is a threshold controlling for the false alarm risk. The statistic can be written as

where the product for .

Often (following Shiryaev’s assumptions), it is supposed that the change point is distributed according to the geometric distribution Geometric

where .

If does not depend on the change point and the prior distribution is geometric (56), then the statistic can be rewritten in the recursive form

However, as mentioned above, this may not be the case for non-i.i.d. models, since often depends on .

Shiryaev–Roberts Procedure

The generalized Shiryaev–Roberts (SR) change detection procedure is based on the thresholding of the generalized SR statistic

with a non-negative head-start , , i.e., the stopping time of the SR procedure is given by

This procedure is usually referred to as the SR-r detection procedure in contrast to the standard SR procedure that starts with a zero initial condition . In the i.i.d. case (50), this modification of the SR procedure was introduced and studied in detail in [44,45].

If does not depend on the change point , then the SR-r detection statistic satisfies the recursion

Note that, as the parameter of the geometric prior distribution , the Shiryaev statistic converges to the SR statistic .

3.2.3. Optimality Criteria

The goal of online change detection is to detect the change with the smallest delay controlling for a false alarm rate at a given level. Tartakovsky et al. [6] suggested several changepoint problem settings, including Bayesian, minimax, and uniform (pointwise) approaches.

Let denote the expectation with respect to measure when the change occurs at and with respect to when there is no change.

In 1954, Page [42] suggested measuring the risk due to a false alarm by the mean time to false alarm and the risk associated with a true change detection by the mean time to detection when the change occurs at the very beginning. He called these performance characteristics the average run length (ARL). Page also introduced the now most famous change detection procedure—the CUSUM procedure (see (52) with replaced by )—and analyzed it using these operating characteristics in the i.i.d. case.

While the false alarm rate can be reasonably measure by the ARL to false alarm

as Figure 1 suggests, the risk due to a true change detection can be reasonably measured by the conditional expected delay to detection

for any possible change point but not necessarily by the ARL to detection . A good detection procedure has to guarantee small values of the expected detection delay for all change points when is set at a certain level. However, if the false alarm risk is measured in terms of the ARL to false alarm, i.e., it is required that for some , then a procedure that minimizes the conditional expected delay to detection uniformly over all does not exist. For this reason, we must resort to different optimality criteria, e.g., to Bayesian and minimax criteria.

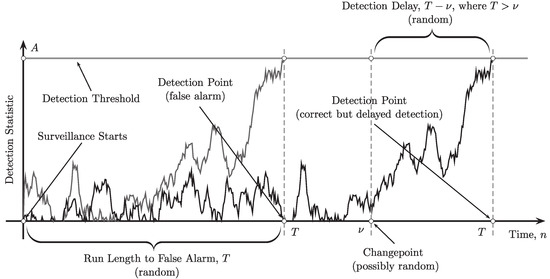

Figure 1.

Illustration of a single-run sequential changepoint detection. Two possibilities in the detection process: false alarm (left) and correct detection (right).

Minimax Changepoint Optimization Criteria

There are two popular minimax criteria. The first one was introduced by Lorden [46]:

This requires minimizing the conditional expected delay to detection in the worst-case scenario with respect to both the change point and the trajectory of the observed process in the class of detection procedures

for which the ARL to false alarm exceeds the prespecified value . Let denote Lorden’s speed detection measure. Under Lorden’s minimax approach, the goal is to find a stopping time such that

In the classical i.i.d. scenario (50), Lorden [46] proved that the CUSUM detection procedure (52) is asymptotically first-order minimax optimal as , i.e.,

Later on, Moustakides [47], using optimal stopping theory, in his ingenious paper, established the exact optimality of CUSUM for any ARL to the false alarm .

Another popular, less pessimistic minimax criterion is from Pollak [48]:

which requires minimizing the conditional expected delay to detection in the worst-case scenario with respect to the change point in class . Under Pollak’s minimax approach, the goal is to find a stopping time such that

For the i.i.d. model (50), Pollak [48] showed that the modified SR detection procedure that starts from the quasi-stationary distribution of the SR statistic (i.e., the head-start in the SR-r procedure is a specific random variable) is third-order asymptotically optimal as , i.e., the best one can attain up to an additive term :

where as . Later, Tartakovsky et al. [49] proved that this is also true for the SR-r procedure (59) that starts from the fixed but specially designed point that depends on , which was first introduced and thoroughly studied by Moustakides et al. [44]. See also Polunchenko and Tartakovsky [50] on the exact optimality of the SR-r procedure.

Bayesian Changepoint Optimization Criterion

In Bayesian problems, the point of change is treated as random with a prior distribution , . Define the probability measure on the Borel -algebra in as

Under measure , the change point has a distribution and the model for the observations is given in (49).

From the Bayesian point of view, it is reasonable to measure the false alarm risk with the weighted probability of false alarm (PFA) defined as

The last equality follows from the fact that because the event depends on the first k observations which under measure correspond to the no-change hypothesis . Thus, for , introduce the class of changepoint detection procedures

for which the weighted PFA does not exceed a prescribed level .

Let denote the expectation with respect to the measure .

Shiryaev [18,43] introduced the Bayesian optimality criterion

which is equivalent to minimizing the conditional expected detection delay

Under the Bayesian approach, the goal is to find a stopping time such that

For the i.i.d. model (50) and for the geometric prior distribution of the changepoint (see (56)), this problem was solved by Shiryaev [18,43]. Shiryaev [18,43,51] proved that the detection procedure given by the stopping time defined in (54) is strictly optimal in class if in (54) can be selected in such a way that , that is

Uniform Pointwise Optimality Criterion

In many applications, the most reasonable optimality criterion is the pointwise uniform criterion of minimizing the conditional expected detection delay for all when the false alarm risk is fixed at a certain level. However, as we already mentioned, if it is required that for some , then a procedure that minimizes for all does not exist. More importantly, as discussed in ([5] Section 2.3), the requirement of having large values of the generally does not guarantee small values of the maximal local probability of false alarm in a time window of a length , while the opposite is always true (see Lemmas 2.1–2.2 in [5]). Hence, the constraint is more stringent than .

Another reason for considering the MLPFA constraint instead of the ARL to false alarm constraint is that the latter one makes sense if and only if the -distribution of stopping times are geometric or at least close to geometric, which is often the case for many popular detection procedures such as CUSUM and SR in the i.i.d. case. However, for general non-i.i.d. models, this is not necessarily true (see [5,52] for a detailed discussion).

For these reasons, introduce the most stringent class of change detection procedures for which the is upper-bounded by the prespecified level :

The goal is to find a stopping time such that

3.2.4. Asymptotic Optimality for General Non-i.i.d. Models via r-Quick and r-Complete Convergence

Complete Convergence and General Bayesian Changepoint Detection Theory

First consider the Bayesian problem assuming that the change point is a random variable independent of the observations with a prior distribution . Unfortunately, in the general non-i.i.d. case and for an arbitrary prior , the Bayesian optimization problem (62) is intractable for arbitrary values of PFA . For this reason, we will consider the first-order asymptotic problem assuming that the given PFA approaches zero. To be specific, the goal is to design such a detection procedure that asymptotically minimizes the expected detection delay to first order as :

where as . It turns out that, in the asymptotic setting, it is also possible to find a procedure that minimizes the conditional expected detection delay uniformly for all possible values of the change point , i.e.,

Furthermore, asymptotic optimality results can also be established for higher moments of the detection delay of the order of

Since the Shiryaev procedure , which was defined in (54), (55), is optimal for the i.i.d. model and prior, it is reasonable to assume that it is asymptotically optimal for the more general prior and the non-i.i.d model. However, to study asymptotic optimality, we need certain constraints imposed on the prior distribution and on the asymptotic behavior of the decision statistics as the sample size increases, i.e., on the general stochastic model (49).

Assume that the prior distribution is fully supported, i.e., for all and and that the following condition holds:

Obviously, if , then the prior has an exponential right tail (e.g., the geometric distribution , in which case ). If , then it has a heavier tail than an exponential tail. In this case, we will refer to it as a heavy-tailed distribution.

Define the LLR of the hypotheses and

( for ). To obtain asymptotic optimality results, the general non-i.i.d. model for observations is restricted to the case that the normalized LLR obeys the SLLN as with a finite and positive number I under the probability measure and its r-complete strengthened version

It follows from Lemma 7.2.1 in [6] that, for any ,

so that if .

The following theorem that can be deduced from Theorem 3.7 in [5] shows that the Shiryaev detection procedure is asymptotically optimal if the normalized LLR converges r-completely to a positive and finite number I and the prior distribution satisfies condition (67).

Theorem 6.

Suppose that the prior distribution of the change point satisfies condition (67) with some . Assume that there exists some number such that the LLR process converges to I uniformly r-completely as under , i.e., condition (68) holds for some . If threshold in the Shiryaev procedure is so selected that and as , e.g., as , then as

and

Therefore, the Shiryaev procedure is first-order asymptotically optimal as in class , minimizing the moments of the detection delay up to order r whenever the r-complete version of the SLLN (68) holds for the LLR process.

For , the assertions of this theorem imply the asymptotic optimality of the Shiryaev procedure for the expected detection delays (65) and (66) as well as asymptotic approximations for the expected detection delays.

Remark 6.

The results of Theorem 6 can be generalized to the asymptotically non-stationary case where converges to I uniformly r-completely as under with a non-linear function similarly to the hypothesis testing problem discussed in Section 3.1. See also the recent paper [53] for the minimax change detection problem with independent but substantially non-stationary post-change observations.

It is also interesting to see how two other most popular changepoint detection procedures—the SR and CUSUM—perform in the Bayesian context.

Consider the SR procedure defined by (58), (59). By Lemma 3.4 (p. 100) in [5],

and therefore, setting implies that . If threshold in the SR procedure is so selected that and as , e.g., as , then as

and

whenever the uniform r-complete convergence condition (68) holds. Therefore, the SR procedure is first-order asymptotically optimal as in class , minimizing the moments of the detection delay up to order r, when the prior distribution is heavy-tailed (i.e., when ) and the r-complete version of the SLLN holds. In the case where (i.e., the prior distribution has an exponential tail), the SR procedure is not optimal. This can be expected since it uses the improper uniform prior in the detection statistic.

The same asymptotic results (69), (70) are true for the CUSUM procedure defined in (52) if threshold is so selected that and as and the uniform r-complete convergence condition (68) holds.

Hence, the r-complete convergence of the LLR process is the sufficient condition for the uniform asymptotic optimality of several popular change detection procedures in class .

Complete Convergence and General Non-Bayesian Changepoint Detection Theory

Consider the non-Bayesian problem where the change point is an unknown deterministic number. We focus on the most interesting for a variety of applications uniform optimality criterion (64) that requires minimizing the conditional expected delay to detection for all values of the change point in the class of change detection procedures defined in (63). Recall that this class includes change detection procedures with the maximal local probability of false alarm in the time window m,

which does not exceed the prescribed value . However, the exact solution to this challenging problem is unknown even in the i.i.d. case.

Instead consider the following asymptotic problem assuming that the given MLPFA goes to zero: find a change detection procedure which asymptotically minimizes the expected detection delay to the first order as . That is, the goal is to design such a detection procedure that

More generally, we may focus on the asymptotic problem of minimizing the moments of the detection delay of order :

To solve this problem, we need to assume that the window length is a function of the MLPFA constraint and that goes to infinity as with a certain appropriate rate. Using [54], the following results can be established.

Consider the SR procedure defined by (58), (59) with , in which case write . Let and assume that the r-complete version of the SLLN holds with some number , i.e., converges to I uniformly r-completely as under . If as and threshold in the SR procedure is so selected that and as , e.g., as defined in [54], then as

A similar result also holds for the CUSUM procedure if threshold is selected so that and as and the r-complete version of the SLLN holds for the normalized LLR as .

Hence, the r-complete convergence of the LLR process is the sufficient condition for the uniform asymptotic optimality of SR and CUSUM change detection procedures with respect to the moments of the detection delay of order r in class .

4. Quick and Complete Convergence for Markov and Hidden Markov Models

Usually, in particular problems, the verification of the SLLN for the LLR process is relatively easy. However, in practice, verifying the strengthened r-complete or r-quick versions of the SLLN, i.e., checking condition (68), can cause some difficulty. Many interesting examples where this verification was performed can be found in [5,6]. However, it is interesting to find sufficient conditions for the r-complete convergence for a relatively large class of stochastic models.

In this section, we outline this issue for Markov and hidden Markov models based on the results obtained by Pergamenchtchikov and Tartakovsky [54] for ergodic Markov processes and by Fuh and Tartakovsky [55] for hidden Markov models (HMM). See also Tartakovsky ([5] Ch 3).

Let be a time-homogeneous Markov process with values in a measurable space with the transition probability with density . Let denote the expectation with respect to this probability. Assume that this process is geometrically ergodic, i.e., there exist positives constants , , and probability measure on and the Lyapunov function V with such that

In the change detection problem, the sequence is a Markov process, such that is a homogeneous process with the transition density and is homogeneous positive ergodic with the transition density and the ergodic (stationary) distribution . In this case, the LLR process can be represented as

where .

Define

Under a set of quite sophisticated sufficient conditions, the LLR converges to I as r-completely (cf. [54]). We omit the details and only mention that the main condition is the finiteness of -th moment of the LLR increment, .

Now consider the HMM with finite state space. Then again, as in the pure Markov case, the main condition for the r-complete convergence of to I, where I is specified in Fuh and Tartakovsky [55], is . Further details can be found in [55].

Similar results for Markov and hidden Markov models hold for the hypothesis testing problem considered in Section 3.1. Specifically, if in the Markov case we assume that the observed Markov process is a time-homogeneous geometrically ergodic with a transition density under hypothesis () and invariant distribution , then the LLR processes are

where . If , then the LLR converges r-completely to a finite number

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of two modes of convergence in the LLN—r-quick and r-complete convergences. These strengthened versions of the SLLN are often neglected in the theory of probability. In the first part of this paper (Section 2), we discussed in detail these two modes of convergence and corresponding strengthened versions of the SLLN. The main motivation was the fact that both r-quick and r-complete versions of the SLLN can be effectively used for establishing near optimality results in sequential analysis, in particular, in sequential hypothesis testing and quickest changepoint detection problems for very general stochastic models of dependent and non-stationary observations. These models are not limited to Markov and hidden Markov models. The results presented in the second part of this paper (Section 3) show that the constraints imposed on the models for observations can be formulated in terms of either the r-quick or r-complete convergence of properly normalized log-likelihood ratios between hypotheses to finite numbers, which can be interpreted as local Kullback–Leibler information numbers. This is natural and can be intuitively expected since optimal or nearly optimal decision-making rules are typically based on a combination of log-likelihood ratios. Therefore, if one is interested in the asymptotic optimality properties of decision-making rules, the asymptotic behavior of log-likelihood ratios as the sample size goes to infinity not only matters but provides the main contribution.

The results presented in this article allow us to conclude that the strengthened r-quick and r-complete versions of the SLLN are useful tools for many statistical problems for general non-i.i.d. stochastic models. In particular, r-quick and r-complete convergences for log-likelihood ratio processes are sufficient for the near optimality of sequential hypothesis tests and changepoint detection procedures for models with dependent and non-identically distributed observations. Such non-i.i.d. models are typical for modern large-scale information and physical systems that produce big data in numerous practical applications. Readers interested in specific applications may find detailed discussions in [4,5,6,7,21,22,33,35,37,53,54,55,56,57,58].

Funding

This article received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No real data were used in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Hsu, P.L.; Robbins, H. Complete convergence and the law of large numbers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1947, 33, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baum, L.E.; Katz, M. Convergence rates in the law of large numbers. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 1965, 120, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strassen, V. Almost sure behavior of sums of independent random variables and martingales. In Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, San Diego, CA, USA, 21 June–18 July 1965 and 27 December 1965–7 January 1966; Le Cam, L.M., Neyman, J., Eds.; Vol. 2: Contributions to Probability Theory. Part 1; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1967; pp. 315–343. [Google Scholar]

- Tartakovsky, A.G. Asymptotic optimality of certain multihypothesis sequential tests: Non-i.i.d. case. Stat. Inference Stoch. Process. 1998, 1, 265–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartakovsky, A.G. Sequential Change Detection and Hypothesis Testing: General Non-i.i.d. Stochastic Models and Asymptotically Optimal Rules; Monographs on Statistics and Applied Probability 165; Chapman & Hall/CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA; London, UK; New York, NY, USA,, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tartakovsky, A.G.; Nikiforov, I.V.; Basseville, M. Sequential Analysis: Hypothesis Testing and Changepoint Detection; Monographs on Statistics and Applied Probability 136; Chapman & Hall/CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA; London, UK; New York, NY, USA,, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, T.L. Asymptotic optimality of invariant sequential probability ratio tests. Ann. Stat. 1981, 9, 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, T.L. On r-quick convergence and a conjecture of Strassen. Ann. Probab. 1976, 4, 612–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, Y.S.; Lai, T.L. Some one-sided theorems on the tail distribution of sample sums with applications to the last time and largest excess of boundary crossings. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 1975, 208, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuh, C.D.; Zhang, C.H. Poisson equation, moment inequalities and quick convergence for Markov random walks. Stoch. Process. Their Appl. 2000, 87, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, A. Sequential tests of statistical hypotheses. Ann. Math. Stat. 1945, 16, 117–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, A. Sequential Analysis; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Wald, A.; Wolfowitz, J. Optimum character of the sequential probability ratio test. Ann. Math. Stat. 1948, 19, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkholder, D.L.; Wijsman, R.A. Optimum properties and admissibility of sequential tests. Ann. Math. Stat. 1963, 34, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthes, T.K. On the optimality of sequential probability ratio tests. Ann. Math. Stat. 1963, 34, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, T.S. Mathematical Statistics: A Decision Theoretic Approach; Probability and Mathematical Statistics; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, E.L. Testing Statistical Hypotheses; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Shiryaev, A.N. Optimal Stopping Rules; Series on Stochastic Modelling and Applied Probability; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1978; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Golubev, G.K.; Khas’minskii, R.Z. Sequential testing for several signals in Gaussian white noise. Theory Probab. Appl. 1984, 28, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartakovsky, A.G. Asymptotically optimal sequential tests for nonhomogeneous processes. Seq. Anal. 1998, 17, 33–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdenskaya, N.V.; Tartakovskii, A.G. Asymptotically optimal sequential testing of multiple hypotheses for nonhomogeneous Gaussian processes in an asymmetric situation. Theory Probab. Appl. 1991, 36, 536–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellouris, G.; Tartakovsky, A.G. Multichannel sequential detection–Part I: Non-i.i.d. data. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2017, 63, 4551–4571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, P. Sequential analysis with more than two alternative hypotheses, and its relation to discriminant function analysis. J. R. Stat. Soc.-Ser. Methodol. 1950, 12, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernoff, H. Sequential design of experiments. Ann. Math. Stat. 1959, 30, 755–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, J.; Sacks, J. Asymptotically optimal sequential inference and design. Ann. Math. Stat. 1963, 34, 705–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorden, G. Integrated risk of asymptotically Bayes sequential tests. Ann. Math. Stat. 1967, 38, 1399–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorden, G. Nearly-optimal sequential tests for finitely many parameter values. Ann. Stat. 1977, 5, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, I.V. Sequential procedure of testing composite hypotheses with applications to the Kiefer-Weiss problem. Theory Probab. Appl. 1990, 35, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, M.; Tartakovsky, A.G. Asymptotic optimality of change-point detection schemes in general continuous-time models. Seq. Anal. 2006, 25, 257–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosteller, F. A k-sample slippage test for an extreme population. Ann. Math. Stat. 1948, 19, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakut, P.A.; Bolshakov, I.A.; Gerasimov, B.M.; Kuriksha, A.A.; Repin, V.G.; Tartakovsky, G.P.; Shirokov, V.V. Statistical Radar Theory; Tartakovsky, G.P., Ed.; Sovetskoe Radio: Moscow, Russia, 1963; Volume 1. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Basseville, M.; Nikiforov, I.V. Detection of Abrupt Changes—Theory and Application; Information and System Sciences Series; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Jeske, D.R.; Steven, N.T.; Tartakovsky, A.G.; Wilson, J.D. Statistical methods for network surveillance. Appl. Stoch. Model. Bus. Ind. 2018, 34, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeske, D.R.; Steven, N.T.; Wilson, J.D.; Tartakovsky, A.G. Statistical network surveillance. In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartakovsky, A.G.; Brown, J. Adaptive spatial-temporal filtering methods for clutter removal and target tracking. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2008, 44, 1522–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szor, P. The Art of Computer Virus Research and Defense; Addison-Wesley Professional: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tartakovsky, A.G. Rapid detection of attacks in computer networks by quickest changepoint detection methods. In Data Analysis for Network Cyber-Security; Adams, N., Heard, N., Eds.; Imperial College Press: London, UK, 2014; pp. 33–70. [Google Scholar]

- Tartakovsky, A.G.; Rozovskii, B.L.; Blaźek, R.B.; Kim, H. Detection of intrusions in information systems by sequential change-point methods. Stat. Methodol. 2006, 3, 252–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartakovsky, A.G.; Rozovskii, B.L.; Blaźek, R.B.; Kim, H. A novel approach to detection of intrusions in computer networks via adaptive sequential and batch-sequential change-point detection methods. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2006, 54, 3372–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegmund, D. Change-points: From sequential detection to biology and back. Seq. Anal. 2013, 32, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustakides, G.V. Sequential change detection revisited. Ann. Stat. 2008, 36, 787–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, E.S. Continuous inspection schemes. Biometrika 1954, 41, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiryaev, A.N. On optimum methods in quickest detection problems. Theory Probab. Appl. 1963, 8, 22–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustakides, G.V.; Polunchenko, A.S.; Tartakovsky, A.G. A numerical approach to performance analysis of quickest change-point detection procedures. Stat. Sin. 2011, 21, 571–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustakides, G.V.; Polunchenko, A.S.; Tartakovsky, A.G. Numerical comparison of CUSUM and Shiryaev–Roberts procedures for detecting changes in distributions. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 2009, 38, 3225–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorden, G. Procedures for reacting to a change in distribution. Ann. Math. Stat. 1971, 42, 1897–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustakides, G.V. Optimal stopping times for detecting changes in distributions. Ann. Stat. 1986, 14, 1379–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollak, M. Optimal detection of a change in distribution. Ann. Stat. 1985, 13, 206–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartakovsky, A.G.; Pollak, M.; Polunchenko, A.S. Third-order asymptotic optimality of the generalized Shiryaev–Roberts changepoint detection procedures. Theory Probab. Appl. 2012, 56, 457–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polunchenko, A.S.; Tartakovsky, A.G. On optimality of the Shiryaev–Roberts procedure for detecting a change in distribution. Ann. Stat. 2010, 38, 3445–3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiryaev, A.N. The problem of the most rapid detection of a disturbance in a stationary process. Sov. Math.–Dokl. 1961, 2, 795–799, Translation from Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR 1961, 138, 1039–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Tartakovsky, A.G. Discussion on “Is Average Run Length to False Alarm Always an Informative Criterion?” by Yajun Mei. Seq. Anal. 2008, 27, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Tartakovsky, A.G.; Veeravalli, V.V. Quickest change detection with non-stationary post-change observations. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2023, 69, 3400–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergamenchtchikov, S.; Tartakovsky, A.G. Asymptotically optimal pointwise and minimax quickest change-point detection for dependent data. Stat. Inference Stoch. Process. 2018, 21, 217–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuh, C.D.; Tartakovsky, A.G. Asymptotic Bayesian theory of quickest change detection for hidden Markov models. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2019, 65, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolessa, A.; Tartakovsky, A.; Ivanov, A.; Radchenko, V. Nonlinear estimation and decision-making methods in short track identification and orbit determination problem. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2020, 56, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartakovsky, A.; Berenkov, N.; Kolessa, A.; Nikiforov, I. Optimal sequential detection of signals with unknown appearance and disappearance points in time. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2021, 69, 2653–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergamenchtchikov, S.M.; Tartakovsky, A.G.; Spivak, V.S. Minimax and pointwise sequential changepoint detection and identification for general stochastic models. J. Multivar. Anal. 2022, 190, 104977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).