Abstract

For solving tensor linear systems under the tensor–tensor t-product, we propose the randomized average Kaczmarz (TRAK) algorithm, the randomized average Kaczmarz algorithm with random sampling (TRAKS), and their Fourier version, which can be effectively implemented in a distributed environment. We analyzed the relationships (of the updated formulas) between the original algorithms and their Fourier versions in detail and prove that these new algorithms can converge to the unique least F-norm solution of the consistent tensor linear systems. Extensive numerical experiments show that they significantly outperform the tensor-randomized Kaczmarz (TRK) algorithm in terms of both iteration counts and computing times and have potential in real-world data, such as video data, CT data, etc.

Keywords:

tensor linear system; randomized average Kaczmarz method; T-product; least-norm problem; Fourier domain MSC:

65F10; 65F45; 65H10

1. Introduction

In this paper, we focus on computing the least F-norm solution for consistent tensor linear systems of the form

where , , and are third-order tensors, and * is the t-product proposed by Kilmer and Martin in [1]. The problem has various applications, such as tensor neural networks [2], tensor dictionary learning [3], medical imaging [4], etc.

The randomized Kaczmarz (RK) algorithm is an iterative method for approximating solutions to linear systems of equations. Due to its simplicity and efficiency, the RK method has attracted widespread attention and has been widely developed in many applications, including ultrasound imaging [5] and seismic imaging [6]. Many developments [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14] of the RK method were obtained, including block Kaczmarz methods. The block Kaczmarz methods [12,13,14], which utilize several rows of the coefficient matrix at each iterate, can be implemented more efficiently in many computer architectures. However, each iteration of the block Kaczmarz method needs to apply the pseudoinverse of the submatrix to a vector, which is expensive. To solve this problem, Necoara [10] proposed the randomized average block Kaczmarz (RABK) method, which utilizes a combination of several RK updates. This method can be implemented effectively in distributed computing units.

Recently, the RK algorithm was extended to solve the system of tensor equations [15,16,17,18]. Ma and Molitor extended the RK method to solve consistent tensor linear systems under the t-product and proposed a Fourier domain version in [15]. Li and Tang et al. [16] presented sketch-and-project methods for tensor linear systems with the pseudoinverse of some submatrix. In [17], Chen and Qin proposed the regularized Kaczmarz algorithm, which avoids the need for the calculation of the pseudoinverse for tensor recovery problems. Wang and Che, et al. [18] proposed the randomized Kaczmarz-like algorithm and its relaxed version to deal with the system of tensor equations with nonsingular coefficient tensors under general tensor–vector multiplication.

In this paper, inspired by the [10,17], we explore the randomized average Kaczmarz (TRAK) method, which is pseudoinverse-free and speeds up over the TRK method for solving tensor linear system (1). However, the entries of each block are determined, which have significant effects on the behavior of the TRAK method. Thus, we propose the tensor randomized average Kaczmarz algorithm with random sampling (TRAKS) which gives an optimized selection of the entries in each iteration. Meanwhile, considering that circulant matrices are diagonalized by the discrete Fourier transform (DFT), we discuss the Fourier domain versions of the TRAK and TRAKS methods. Their corresponding convergence analyses are proved. Numerical experiments are given to illustrate our theoretical results.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we introduce some notations and tensor basics. Then, we describe new algorithms and give their convergence theories in Section 3, Section 4 and Section 5. In Section 6, some numerical experiments are presented to illustrate our theoretical results. Finally, we propose a brief conclusion in Section 7.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we provide clarification of notations, a brief review of fundamental concepts in tensor algebra and some existing algorithms.

2.1. Notation

Throughout this paper, we use calligraphic capital letters for tensors, capital letters for matrices, and lowercase letters for scalars. For any matrix A, we use , , , , , and to denote the transpose, the conjugate transpose, the Moore–Penrose pseudoinverse, Frobenius norm, Euclidean norm, and the minimum nonzero singular values of A, respectively. For an integer m, let . For a set C, we define as the cardinality of C. We denote and as the expectation of and the conditional expectation of given , respectively. By the law of total expectation, we have .

2.2. Tensor Basics

In this subsection, we provide some key definitions and facts in tensor algebra, which can be found in [1,15,16,19,20].

For a third-order tensor , as done in [15,16], we denote its entry as and use , and to denote the horizontal slice, the lateral slice and the frontal slice. To condense notation, represents the frontal slice of . We define the block circulant matrix of as

Definition 1

(DFT matrix). The DFT matrix is defined as

where .

The inverse matrix of the DFT matrix (IDFT) is .

Lemma 1

([1]). Suppose is an tensor and is an DFT matrix. Then

where “⊗” is Kronecker product, denotes the identity matrix, is the frontal face of which is obtained by applying the DFT on along the third dimension and is the block diagonal matrix formed by the frontal faces of .

We denote the operator and its inversion as

Definition 2

(t-product [1]). The tensor–tensor t-product is defined as

where and .

For and , it holds that

and

Definition 3

(conjugate transpose [15]). The conjugate transpose of a tensor is denoted as and is produced by taking the conjugate transpose of all frontal slices and reversing the order of the frontal slices .

For , we have

For , the block circulant operator commutes with the conjugate transpose, this is

For and , we have that

Definition 4

(identity tensor). The identity tensor is the tensor whose first frontal slice is an identity matrix, and its other frontal slices are all zeros.

For , it holds that

Definition 5

(Moore–Penrose inverse [20]). Let . If there exists such that

then is called the Moore–Penrose inverse of and is denoted by .

Definition 6

(inner product). The inner product between and in is defined as

where is the conjugate of .

For , and , it holds that

Definition 7

(spectral norm and Frobenius norm). The spectral norm and Frobenius norm of are defined as

and

respectively.

For and , it holds that

Definition 8

(K-range space, K-null space [1]). For , define

We easily know that

For and all , it holds that

Theorem 1

([20]). Let , and . Then the minimum F-norm solution of a consistent system is unique, and it is .

Theorem 2.

Let with , and be consistent. Then, there is only one solution to in , which is the minimum F-norm solution .

Proof.

Suppose that are the solutions of , then, we have that

Note that the above equations can be written as

Therefore,

By , we also know that

Thus,

From Equation (7) and Definition 5, we can obtain

Finally, by Theorem 1, we obtain the desired result. □

2.3. Randomized Average Block Kaczmarz Algorithm

For computing the least-norm solution of the large consistent linear system Necoara [10] developed the randomized average block Kaczmarz (RABK) algorithm which projected the current iteration vector onto each individual row of the chosen submatrix and then averaged these projections with the weights. The updated formula of the RABK algorithm with a constant stepsize can be written as

where the weights are chosen to satisfy for all i and sum to 1.

In each iteration, if we average obtained projections with the weights , we can obtain Algorithm 1. This algorithm avoids the need for each iterate of the randomized block Kaczmarz algorithm [14] to apply the pseudoinverse to a vector, which is cheaper.

| Algorithm 1 Randomized average block Kaczmarz (RABK) algorithm |

|

2.4. Randomized Regularized Kaczmarz Algorithm

Chen and Qin [17] provided the randomized regularized Kaczmarz algorithm based on the RK algorithm for the consistent tensor recovery problem:

where the objective function f is strongly convex, and .

Let and be the convex conjugate function of f and the gradient of at , respectively. Then, the randomized regularized Kaczmarz algorithm is obtained as follows (Algorithm 2).

| Algorithm 2 Randomized Regularized Kaczmarz Algorithm |

|

For the least F-norm problem of consistent tensor linear systems (1), we have

3. Tensor Randomized Average Kaczmarz Algorithm

In this section, similar to the RABK algorithm, the TRAK algorithm is designed to pursue the minimum F-norm solution of a consistent tensor linear systems (1), which takes a combination of several TRK updates, i.e.,

We give the method in Algorithm 3. We emphasize that the algorithm can be implemented on distributed computing units. If the number of partition for is , then the TRAK algorithm will reduce to the TRK algorithm.

| Algorithm 3 Tensor randomized average Kaczmarz (TRAK) algorithm |

|

Remark 1.

Since and

we obtain that by induction. Therefore, Iif the iteration sequence generated by the TRAK algorithm converges to a solution , will be the least F-norm solution by Theorem 2.

Next, we analyze the convergence of the TRAK algorithm with a constant stepsize.

Theorem 3.

Let the tensor linear system (1) be consistent. Assume that is a partition of . Let and . Then the iteration sequence generated by the TRAK algorithm with converges in expectation to the unique least F-norm solution . Moreover, the expected norm of solution error obeys

Proof.

Subtracting from both sides of the TRAK update given in Equation (15), we have that

To simplify notation, we use . Then,

Since , we can obtain

Taking the conditional expectation conditioned on , we have

By Remark 1 and Theorem 2, we have .

Therefore,

By the law of total expectation, we have

Finally, unrolling the recurrence gives the desired result. □

When , the tensor , and will degenerate to an matrix A, an matrix X and an matrix B, respectively. Problem (1) becomes a problem of solving the least F-norm solution for consistent matrix linear systems

where , and .

Then, Algorithm 3 becomes Algorithm 4.

| Algorithm 4 Matrix randomized average Kaczmarz (MRAK) algorithm |

|

In this setting, Theorem 3 reduces to the following result.

Corollary 1.

Let the matrix linear system (17) be consistent. Assume that is a partition of . Let and . Then the iteration sequence generated by the MRAK algorithm with converges in expectation to the unique least F-norm solution . Moreover, the expected norm of solution error obeys

4. Tensor Randomized Average Kaczmarz Algorithm with Random Sampling (TRAKS)

In Algorithm 3, we give the partition of before the TRAK algorithm starts to run. In this setting, the entries of each block are determined in the iteration. However, the partition of has a significant effect on the behavior of the TRAK method, as shown in [14]. Motivated by [21], we use a small portion of the horizontal slice of to estimate the whole and propose the tensor randomized average Kaczmarz algorithm with random sampling (TRAKS).

In the TRAKS method, we first randomly sample from the population with normal distribution . Next, in order to avoid unreasonable sampling that cannot estimate the whole well, we use “Z” test [22] to evaluate the results of each random sampling. Precisely, let be random samples from all horizontal slices of . Then, the significant difference between the samples and the population can be judged by the Z-score:

where is the population mean, is the sample mean and is the sample standard deviation. If , the occurrence probability of significant difference will be no more than and we accept the sampling, otherwise, we need to resample from the population. We list the TRAKS method in Algorithm 5.

| Algorithm 5 Tensor randomized average Kaczmarz algorithm with random sampling (TRAKS) |

|

In order to prove the convergence of Algorithm 5, we need to prepare a lemma and a theorem firstly.

Lemma 2

([23]). If both and are two arrays with real components and satisfy , then the following inequality is established

Lemma 3

([22] (Chebyshev’s law of large numbers)). Suppose that is a series of independent random variables. They have expectation and variance , respectively. If there is a constant C such that , for any small positive number ϵ, we have

Lemma 3 indicates that if the sample size is large enough, the sample mean will approach to the population mean.

Next, we discuss the convergence of the TRAKS method.

Theorem 4.

Let the tensor linear system (1) be consistent. Assume that β is the size of the sample and is the cardinality of the sample set accepted by the “Z” test. Let , and . Then the iteration sequence generated by the TRAKS algorithm with converges in expectation to the unique least F-norm solution . Moreover, the expected norm of solution error obeys

Proof.

From the last line of (16) in the Proof of Theorem 3, we have that

Since , we can obtain

Taking conditional expectation conditioned on , we have that

Assume that the sample set accepted by the “Z” test is C and , we can obtain that

According to Lemma 3, when is large enough and is sufficiently large, there exist , such that

and

By Remark 1 and Theorem 2, we have .

Therefore,

By the law of total expectation, we have

□

For solving (17), Algorithm 5 becomes Algorithm 6.

| Algorithm 6 Matrix randomized average Kaczmarz algorithm with random sampling (MRAKS) |

|

Theorem 4 reduces to the following result.

Corollary 2.

Let the matrix linear system (17) be consistent. Assume that β is the size of the sample and is the cardinality of the sample set accepted by the “Z” test. Let , and . Then the iteration sequence generated by the MRAKS algorithm with converges in expectation to the unique least F-norm solution . Moreover, the expected norm of solution error obeys

5. The Fourier Version of the Algorithms

We first introduce two additional notations that are widely used in this subsection. For , denotes the mode-3 fast Fourier transform of , which can also be written as ( is defined in Definition 1.). Similarly, denotes the mode-3 inverse fast Fourier transform of and . By Definition 1, we easily know that . Furthermore, for the convenience of viewing, we introduce the tensor operator “bdiag” again. For , is the block diagonal matrix formed by the frontal faces of , i.e.,

By Lemma 1, the tensor linear system can be reformulated as

where , and are the frontal slices of , and , respectively ( is an DFT matrix and is defined in Definition 1.)

Before we present the algorithms in the Fourier domain, we provide a key theorem.

Theorem 5.

Let and be the set of horizontal slice indicator in and the set of row indicator in , respectively. Assume that the sequence is generated by

with and for solving Equation (22). Then, for tensor linear systems (1), the iteration scheme of the TRAK and TRAKS algorithms in the Fourier domain is

for Moreover, it holds that

Proof.

where the second equality follows from

and .

With the use of the block-diagonal structure, Equation (24) can be reformulated as

for

Since and , we can generate that

and

where is the cardinality of .

Therefore, it holds that

Since and , with the recurrence Formula (27) it holds that

This completes the proof. □

By the above analysis, we propose the Fourier version of the TRAK and TRAKS algorithms, i.e., Algorithms 7 and 8.

| Algorithm 7 TRAK algorithm in the Fourier domain () |

|

| Algorithm 8 TRAKS algorithm in the Fourier domain () |

|

Remark 2.

By multiplying the IDFT matrix (Definition 1) and folding on both sides of (27), we obtain

If we select , where are the stepsizes of the algorithms that are not in the Fourier domain and stepsizes of the algorithms in the Fourier domain, respectively, Equation (28) will be similar to the update (15) of the algorithms that are not in the Fourier domain. However, the and algorithm make use of the block-diagonal structure, which can be implemented more efficiently than the TRAK and TRAKS algorithms. Moreover, the and algorithms can be computed in parallel well.

Taking advantage of the relationship between the TRAK and updates and the TRAKS and updates, the convergence guarantees of the and algorithms are generated as follows.

Theorem 6.

Assume that the tensor linear system (1) is consistent. Assume that is a partition of . Let and . Then the iteration sequence generated by the algorithm with converges in expectation to the unique least F-norm solution . Moreover, the expected norm of the solution error obeys

Theorem 7.

Let the tensor linear system (1) be consistent. Assume that β is the size of the sample and is the cardinality of the sample set accepted by the “Z" test. Let , and . Then the iteration sequence generated by the algorithm with converges in expectation to the unique least F-norm solution . Moreover, the expected norm of solution error obeys

6. Numerical Experiments

In this section, we compare the performances of the TRK, TRAK, TRAKS, and algorithms in some numerical examples. The tensor t-product toolbox [24] is used in our experiments. The stopping criterion is

or the number of iteration steps exceeds . In our implementations, all computations are started from the point . IT and CPU(s) mean the medians of the required iteration steps and the elapsed CPU times with respect to 10 times of the repeated runs of the corresponding method, respectively. In the following experiments, we use the structural similarity index (SSIM) between two images X and Y to evaluate the recovered image quality, which is defined as

where and are the mean and standard deviation of image X, is the cross-covariance between X and Y, and and are the luminance and contrast constants. SSIM values can be obtained by using the MATLAB function SSIM.

All experiments were carried out using MATLAB R2020b on a laptop with an Intel Core i7 processor, 16GB memory, and Windows 11 operating system.

For the TRAK and algorithms, we consider a partition of , which is proposed in [14]:

where is a permutation on chosen uniformly at random.

6.1. Synthetic Data

We generate the sensing tensor and the acquired measurement tensor as follows:

We set and .

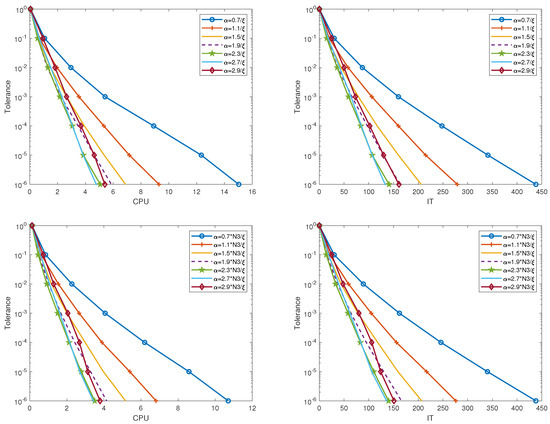

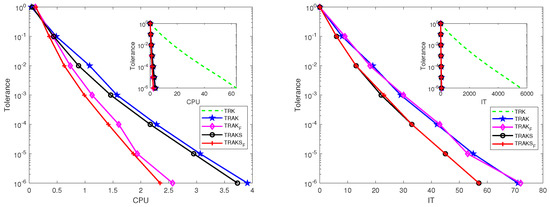

In the TRAK, TRAKS, , and algorithms, we know that s, , and affect the numerical results. Thus, we first show how they impact the performance of our methods in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4. In Figure 1, we plot the CPU and IT of the TRAK and algorithms with the number of partitions and different stepsizes for different tolerances. We can find that the convergences of the TRAK and algorithms are quicker with respect to the increase of and the fixed , but slow down after reaching the faster convergence rate. Moreover, the TRAK and algorithms also converge for and , and converge much faster by using the appropriate extrapolated stepsize. In Figure 2, we plot the curves of the TRAKS and algorithms with different stepsizes when . In this experiment, we approximate by using the maximum value of obtained by random sampling 100 times. From this figure, we can observe that the convergence rates of the TRAKS and algorithms raise firstly and then slow down with respect to the increase of .

Figure 1.

CPU and IT of the TRAK and algorithms with the number of partitions and different stepsizes for different tolerances. Upper: TRAK. Lower: .

Figure 2.

CPU and IT of the TRAKS and algorithms with and different stepsizes for different tolerances. Upper: TRAKS. Lower: .

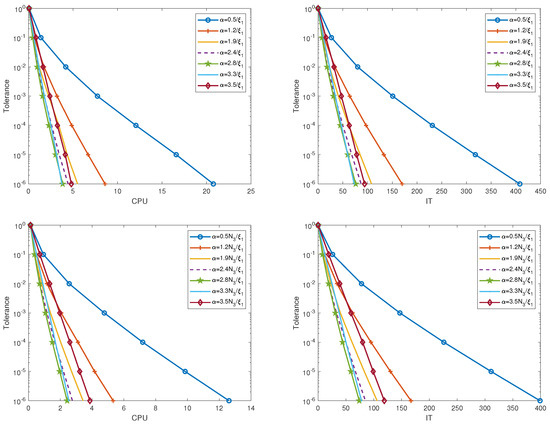

Figure 3.

CPU and IT of the TRAK and algorithms with extrapolated stepsize and different number of partitions. Upper: TRAK. Lower: .

Figure 4.

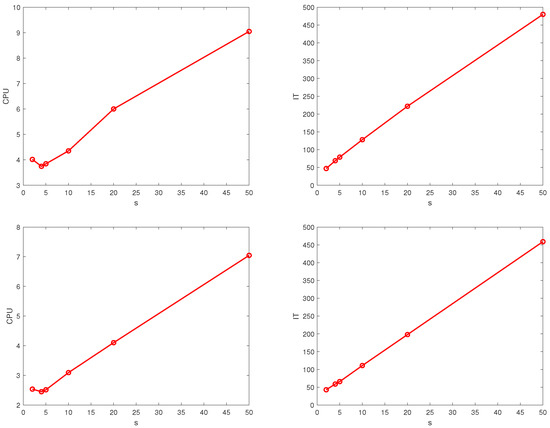

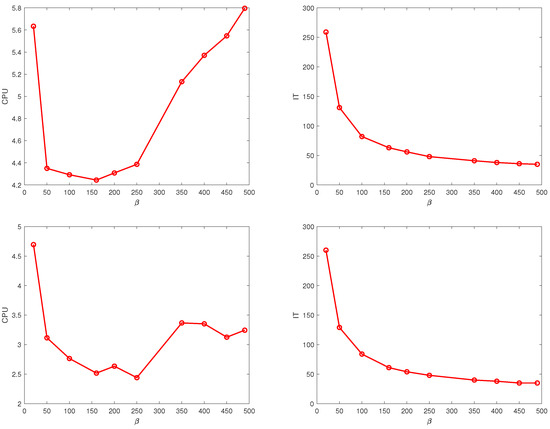

CPU and IT of the TRAKS and algorithms for different . Upper: TRAKS. Lower: .

In Figure 3, we depict the curves of the average number of iterations and computing times of the TRAK and algorithms versus the different number of partitions. In Figure 4, we plot the curves of the average CPU times and average IT of the TRAKS and algorithms for different . We use , , and . For all cases, we set . From these figures, we see that the CPU times are decreasing at the beginning and then increasing with respect to the increase of parameters. The number of iteration steps are always increasing, with respect to the increase of s, for both TRAK and , while the TRAKS and algorithms are the opposite for the number of iteration steps. In general, from Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, there is an optimal combination of parameters that makes our algorithms perform best. In the following experiments, we use the optimal experimental results obtained by trial and error.

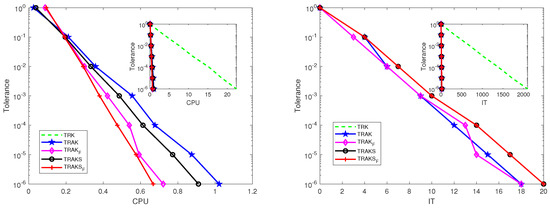

To compare the performances of these algorithms, we use , which makes the TRK algorithm achieve optimal performance. For the TRAK, , TRAKS, and algorithms, , , , , and are used. In Figure 5, we depict the curves of tolerance versus the iteration steps and the calculated times. We observe that the TRAK, , TRAKS, and algorithms converge much faster than the TRK algorithm, and the original algorithms and their Fourier versions have the same number of iteration steps for identical tolerance. The algorithm has the best performance in terms of CPU time.

Figure 5.

Pictures of tolerance versus IT and CPU times for the TRK, TRAK, , TRAKS, and algorithms when is synthetic data.

6.2. 3D MRI Image Data

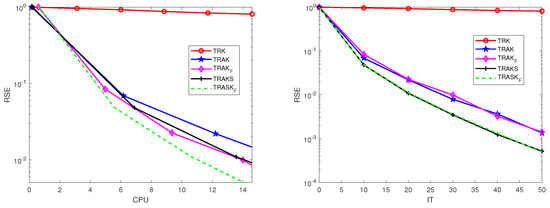

This experiment considers an image data from data set mri in MATLAB. We generate randomly a Gaussian tensor and form the measurement tensor by . The parameters are tuned to achieve optimal performance in all algorithms. We use , , , , , and . The results are reported in Figure 6. From the figure, we find that the TRAK, , TRAKS, and algorithms significantly outperform the TRK algorithm. Meanwhile, it is easy to see that the algorithm performs better than the other algorithms in terms of CPU time.

Figure 6.

Pictures of tolerance versus IT and CPU times for the TRK, TRAK, , TRAKS, and algorithms when comes from the 3D MRI image data set.

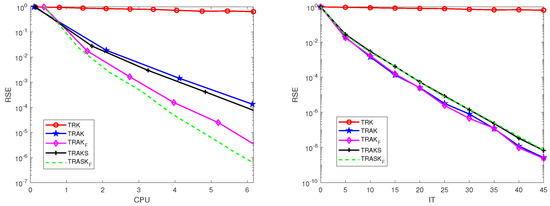

6.3. Video Data

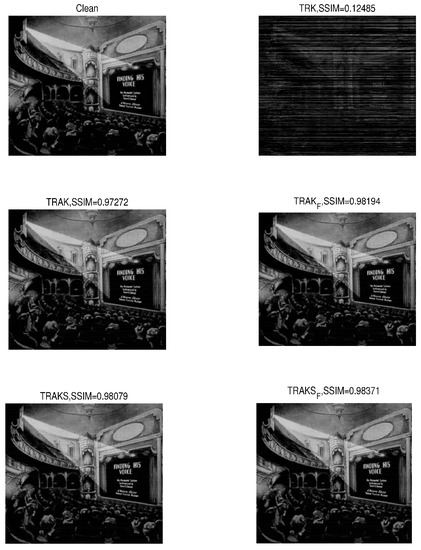

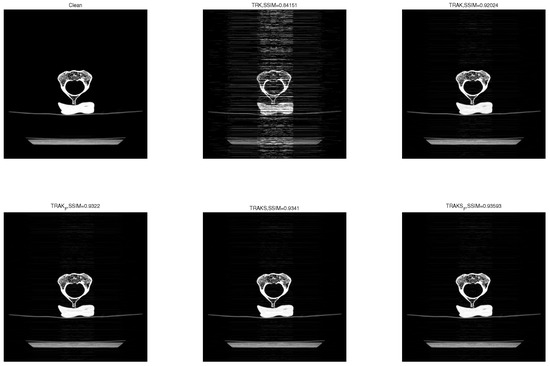

The experiment was implemented on video data, where the frontal slices of tensor were the first 60 frames from the 1929 film “Finding His Voice” [25]. Each video frame had pixels. Similar to Experiment Section 6.2, we randomly obtained a Gaussian tensor and form the measurement tensor by . In this test, we used , , , , , and , which made all algorithms achieve the best performance. In Figure 7, we plot the curves of the average RSE versus IT and CPU times for all algorithms. From this figure, we observe that the TRAK, , TRAKS, and algorithms significantly outperformed the TRK algorithm in terms of IT and CPU times and the algorithm had a great advantage in the calculating time. In addition, we run the TRK, TRAK, , TRAKS, and algorithms for 50, 15, 15, 19, and 19 iterations, respectively. Their reconstructions are reported in Figure 8. From Figure 8, we observe that the SSIM of the TRK algorithm was much smaller than that of the TRAK, , TRAKS, and algorithms, which implies that the reconstruction results of the TRAK, , TRAKS, and algorithms are apparently better than that of the TRK algorithm. Moreover, the algorithm requires less CPU time than the other algorithms.

Figure 7.

Pictures of the average RSE versus IT and CPU times for the TRK, TRAK, , TRAKS, and algorithms when is the video datum.

Figure 8.

The frame of the clean film and the images recovered by the TRK, TRAK, , TRAKS, and algorithms. , , , , .

6.4. CT Data

In this experiment, we test the performance of the algorithms using the real world CT data set. The underlying signal is a tensor of size , where each frontal slice is a matrix of the C2-vertebrae. The images were taken from the Laboratory of the Human Anatomy and Embryology, University of Brussels (ULB), Belgium [26]. We also obtain randomly a Gaussian tensor and . Let , , , , , and . We run the TRK, TRAK, , TRAKS, and algorithms for 40, 15, 15, 13, and 13 iterations, respectively. Their numerical results are presented in Figure 9 and Figure 10. From Figure 9, we see again that the TRAK, , TRAKS, and algorithms converge faster than the TRK algorithm. From Figure 10, we observe that the SSIMs of the TRAK, , TRAKS, and algorithms are much closer to 1 than that of the TRK algorithm, which implies that the TRAK, , TRAKS, and algorithms achieve better reconstruction results. In addition, the algorithm requires less CPU time than the other algorithms.

Figure 9.

Pictures of the average RSE versus IT and CPU times for the TRK, TRAK, , TRAKS, and algorithms when is a CT data.

Figure 10.

The slice of the clean image sequence and the images recovered by the TRK, TRAK, algorithms. , , , , .

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we propose the TRAK and TRAKS algorithms and discuss the Fourier domain version. The new algorithms can be efficiently implemented in distributed computing units. Numerical results show that the new algorithms have better performance than the TRK algorithm. Meanwhile, we note that the sizes of the samples, the number of partitions, and the stepsizes play important roles in guaranteeing fast convergences of the new methods. Therefore, in future work, we will obtain more appropriate parameters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.B. and F.Z.; Methodology, W.B. and F.Z.; Validation, W.B. and F.Z.; Writing—original draft preparation, F.Z.; Writing—review and editing, W.B., F.Z., W.L., Q.W. and Y.G.; Software, Q.W. and Y.G.; Visualization, F.Z., Q.W. and Y.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (grant number ZR2020MD060), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant number 20CX05011A), and the Major Scientific and Technological Projects of CNPC (grant number ZD2019-184-001).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the referees for their constructive comments and valuable suggestions, which have greatly improved the original manuscript of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kilmer, M.E.; Martin, C.D. Factorization strategies for third-order tensors. Linear Algebra Its Appl. 2011, 435, 641–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, E.; Horesh, L.; Avron, H.; Kilmer, M. Stable tensor neural networks for rapid deep learning. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.06569. [Google Scholar]

- Soltani, S.; Kilmer, M.E.; Hansen, P.C. A tensor-based dictionary learning approach to tomographic image reconstruction. Bit Numer. Math. 2016, 56, 1425–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Li, L.; Zhu, H. Tensor regression with applications in neuroimaging data analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2013, 108, 540–552. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, A.H.; Kak, A.C. Simultaneous algebraic reconstruction technique (SART): A superior implementation of the ART algorithm. Ultrason. Imaging 1984, 6, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, J.E.; Paulsson, B.N.; McEvilly, T.V. Applications of algebraic reconstruction techniques to crosshole seismic data. Geophysics 1985, 50, 1566–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouzias, A.; Freris, N.M. Randomized extended Kaczmarz for solving least squares. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 2013, 34, 773–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needell, D. Randomized Kaczmarz solver for noisy linear systems. BIT Numer. Math. 2010, 50, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, J.D.; Tu, T.K.; Molitor, D.; Needell, D. Randomized Kaczmarz with averaging. Bit Numer. Math. 2021, 61, 337–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Necoara, I. Faster randomized block Kaczmarz algorithms. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 2019, 40, 1425–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.Q.; Wu, W.T. On greedy randomized average block Kaczmarz method for solving large linear systems. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2022, 413, 114372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfving, T. Block-iterative methods for consistent and inconsistent linear equations. Numer. Math. 1980, 35, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggermont, P.P.B.; Herman, G.T.; Lent, A. Iterative algorithms for large partitioned linear systems with applications to image reconstruction. Linear Algebra Its Appl. 1981, 40, 37–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needell, D.; Tropp, J.A. Paved with good intentions: Analysis of a randomized block Kaczmarz method. Linear Algebra Its Appl. 2014, 441, 199–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A.; Molitor, D. Randomized Kaczmarz for tensor linear systems. BIT Numer. Math. 2022, 62, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H. Sketch-and-project methods for tensor linear systems. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.00667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Qin, J. Regularized Kaczmarz algorithms for tensor recovery. SIAM J. Imaging Sci. 2021, 14, 1439–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Che, M.; Mo, C.; Wei, Y. Solving the system of nonsingular tensor equations via randomized Kaczmarz-like method. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2023, 421, 114856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilmer, M.E.; Braman, K.; Hao, N.; Hoover, R.C. Third-order tensors as operators on matrices: A theoretical and computational framework with applications in imaging. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 2013, 34, 148–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Bai, M.; Benítez, J.; Liu, X. The generalized inverses of tensors and an application to linear models. Comput. Math. Appl. 2017, 74, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wu, G.; Jiang, L. A Kaczmarz method with simple random sampling for solving large linear systems. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.14693. [Google Scholar]

- Carlton, M.A. Probability and Statistics for Computer Scientists. Am. Stat. 2008, 62, 271–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, W.; Bao, W.; Gao, X. Nonlinear Kaczmarz algorithms and their convergence. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2022, 399, 113720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C. Tensor-Tensor Product Toolbox. Carnegie Mellon University. 2018. Available online: https://github.com/canyilu/tproduct (accessed on 17 July 2022).

- Finding His Voice. Available online: https://archive.org/details/FindingH1929 (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Bone and Joint ct-scan Data. Available online: https://isbweb.org/data/vsj/ (accessed on 25 August 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).