Abstract

The point of this research is to present a new iterative procedure for approximating common fixed points of nonexpansive mappings in Hadamard manifolds. The convergence theorem of the proposed method is discussed under certain conditions. For the sake of clarity, we provide some numerical examples to support our results. Furthermore, we apply the suggested approach to solve inclusion problems and convex feasibility problems.

MSC:

47J25; 47H10

1. Introduction

Let C be a nonempty, closed, and geodesic convex subset of a Hadamard manifold M. Assume that is a nonexpansive mapping, which means that for every , where stands for a Riemannian distance function. In this research, we consider the following fixed point problem:

denotes the set of fixed points of the mapping g. Many problems, such as convex feasibility problems, convex optimization problems, monotone variational inequalities, and image restorations, can be cast in the light of fixed point problems for nonexpansive mappings, which leads to a wide range of specific applications (see [1,2,3,4] and references therein).

To estimate fixed points, there is a significant amount of literature on fixed point iteration approaches. Most of the research has focused on the case when g is a self-mapping defined on a convex subset C of a normed linear space, and here are some of the most famous variations:

- 1.

- The Picard algorithm [5] is defined by

- 2.

- The Mann algorithm [6] is defined bywhere is a sequence in .

- 3.

- The Ishikawa algorithm [7] is defined bywhere and are sequences in . One can see that the Ishikawa algorithm is a two-step Mann algorithm.

Assuming g is a contraction mapping, the sequence generated by Picard’s iteration (2) converges strongly to a unique fixed point. The Picard method may not converge if the mapping g is nonexpansive. On the other hand, the sequence produced by Mann’s iteration (3) converges weakly to a fixed point of the nonexpansive mapping g. Subsequently, numerous scholars have investigated the Mann method and the Ishikawa algorithm to estimate fixed points of nonexpansive mapping. Observe, for instance [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15].

Both Sahu et al. [9] and Thakur et al. [10] published their findings in 2016, proposing the same iterative approach for approximating fixed points of nonexpansive mappings in uniformly convex Banach spaces:

where , and are sequences in . The authors [9,10] showed that the iterative scheme (5) converges to fixed points of contractive mappings faster than various existing iterative schemes. Recently, the iterative method (5) has been an attractive process and has been extensively studied in many directions; see, e.g., Refs. [12,16,17,18]. In particular, Padcharoen and Sukprasert [12] improved and extended the iterative scheme (5) for finding common fixed points of two nonexpansive mappings , which is defined by the following:

where , and are sequences in . The authors of [12] proved that the sequence achieved by (6) converges weakly to common fixed points. Moreover, they applied the proposed iteration to solve common solutions of accretive operators, convex constrained least square problems, convex minimization problems, and signal processing in Banach spaces.

In recent years, many scholars have turned their attention to nonlinear problems in nonlinear systems such as Hadamard manifolds and CAT(0) spaces [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Nonlinear problems naturally extend from linear spaces to Riemannian manifolds, which provides a range of advantages. For instance, non-convex problems can be transformed as convex problems by introducing an appropriate Riemannian metric, and constrained optimization problems can be approached in the same manner as unconstrained problems. In addition to this, Hadamard manifolds are suitable frameworks for the development of effective methods for the solution of realistic problems [27,28,29,30].

In 2010, Li et al. [11] investigated the fixed point problem (1) in the context of Hadamard manifolds. The Mann and Halpern methods were also extended from Euclidean spaces to Hadamard manifolds. Recently, S-iterative techniques for approximating common fixed points of two nonexpansive mappings in the setting of Hadamard manifolds were recently presented by Sahu et al. [13].

Algorithm 1 (S-iterative algorithm rank 2).

Givenare nonexpansive mappings andis defined by

where, are sequences inand exp is an exponential mapping.

Algorithm 2 (S-iterative algorithm rank 3).

Givenare nonexpansive mappings andis defined by

whereandare sequences in.

It was shown by the authors [13] that any sequence produced by the suggested two algorithms converges to the common fixed points of nonexpansive maps. In addition, they provide numerical examples to support their assertions.

The goal of this paper is to provide a formal introduction to the iterative process (6) in terms of exponential mappings on Hadamard manifolds, building on the foundation laid in [11,12]. Under certain conditions, we establish the convergence theorem of our proposed method for common fixed points of two nonexpansive mappings. We provide some numerical examples to indicate how successful the proposed method is, and we compare it with some of the other methods that are already in use. In addition to this, we illustrate how the proposed method can be utilized to solve inclusion and convex feasibility problems in Hadamard manifolds.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, we present basic concepts and fundamental results in Riemannian geometry. In Section 3, we propose an iterative algorithm for finding common fixed points of nonexpansive mappings in Hadamard manifolds. We establish the convergence results of the proposed algorithm. In Section 4, we present some numerical experiments to demonstrate applications of the results in the present paper. Section 5 consists of applications to inclusion problems and convex feasibility problems in Hadamard manifolds. Finally, Section 6 provides a concise overview of the paper.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we review the necessary terminology, concepts, properties, and results from Riemannian geometry that will be used in the rest of the paper. Readers may find references to it in a variety of textbooks that serve as introduction to Riemannian geometry. Some examples are [31,32,33].

Let us assume that M is a connected manifold with finite dimensions. The tangent bundle of M is defined by , where is the tangent space of M at p and denotes the zero section of Every manifold M is a Riemannian manifold if and only if it is endowed with a Riemannian metric with the corresponding norm denoted by If there is no doubt, the subscript p is omitted. Determine the length of the piecewise smooth curve by using the formula where is the tangent vector at in the tangent space . A Riemannian distance, indicated by , is the shortest path between any two points p and q.

Let ∇ be a Levi–Civita connection associated with the Riemannian manifold M. A smooth vector field V along a smooth curve is said to be parallel ⟺. If is parallel to itself, we call it a geodesic, and in this case is a constant. The curve is considered to be normalized when the value of . If the length of a geodesic that joins two points p and q in M is equal to the distance between those two points, then we refer to that geodesic as a minimizing geodesic.

If the geodesics of a Riemannian manifold can be determined for any value of , then the manifold is said to be complete. The Hopf–Rinow theorem states that if M is complete, then any two points in M can be connected via a minimizing geodesic. In addition to this, because is a complete metric space, any bounded closed subset is a compact subset.

Let M be a complete Riemannian manifold and . The exponential map is given by , where is the geodesic starting at the point p with velocity u (i.e., and ). Then, for each real number t, we have and . Note that exponential map is differentiable on for each . This implies that the exponential map has an inverse . We also have .

A complete simply connected Riemannian manifold of non-positive sectional curvature is named a Hadamard manifold. The remainder of the article will proceed on the assumption that M is a Hadamard manifold with finite dimensions. The exponential mapping is a diffeomorphism for . Any two points have a unique minimizing normalized geodesic connecting them ([31] Theorem 4.1).

A geodesic triangle of a Riemannian manifold M is a set consisting of three points , and , and three minimizing geodesics joining these points.

Proposition 1

([31]).Let be a geodesic triangle. Then

and

Moreover, if θ is the angle at , then we have

Readers can refer to [34] for further information on the relation between geodesic triangles on Riemannian manifolds and triangles on .

Lemma 1

([34]).Let be a geodesic triangle in M. Then, there exists a triangle for such that , indices taken modulo 3; it is unique up to an isometry of .

The triangle in Lemma 1 is said to be a comparison triangle for . The points , , are called comparison points to the points respectively.

Lemma 2.

Let be a geodesic triangle in M and be its comparison triangle.

- (i)

- Let (respectively, ) be the angles of (respectively, ) at the vertices (respectively, , , ). Then

- (ii)

- Let q be a point on the geodesic joining to and its comparison point in the interval . If and , then .

Several convex analysis concepts and results have been extended in the setting of manifolds. We present some of these that will be used throughout the rest of the paper.

Let M be an Hadamard manifold. A set is called geodesic convex if for any two points p and q in C, the geodesic joining p to q is contained in C; that is, if is a geodesic such that and , then and . A real valued function is called geodesic convex if for any geodesic the composition function is convex; that is,

Proposition 2

([31]).Let the distance function be . Then, is a geodesic convex function with respect to the Riemannian metric product; that is, the following inequality holds for any pair of geodesics and .

In particular, for each , the function is a geodesic convex.

Let us conclude this section with the following results, which are essential to proving our convergence theorem.

Definition 1

([20]).Assume that is a sequence in M and that C is a nonempty subset of M. If and , then is Fejér monotone with respect to C.

Lemma 3

([20]).Let C be a nonempty subset of M and be a sequence in M, such that is a Fejér monotone with respect to C. Then, the following holds:

- (i)

- For every , converges;

- (ii)

- is bounded;

- (iii)

- Assume that any cluster point of belongs to C, then converges to a point in C.

3. Main Results

Unless otherwise stated, the rest of this article will refer to C in terms of a nonempty, closed, and geodesic convex subset of a Hadamard manifold Given two mappings g and h from C to C, we say that g and h have at least one fixed point. The common fixed points between mappings g and h are denoted . An iterative approach for finding common fixed points of two nonexpansive mappings g and h is described below.

Algorithm 3.

Letare mappings, andbe an initial point. Givenand calculateby

whereandare real positive sequences in.

Following this, we are going to prove that Algorithm 3 satisfies the conditions required to achieve the convergence theorem.

Theorem 1.

Let C be a nonempty, closed and geodesic convex subset of a Hadamard manifold M, and are nonexpansive mappings such that . Suppose that and are real positive sequences satisfying and . Let and is defined by Algorithm 3. Then converges to a common fixed point of g and h.

Proof.

Because is a complete metric space and , it is sufficient to show by Lemma 3 that is Fejér monotone with respect to and the cluster point of belongs to .

Fix , let and be geodesic connecting to , be geodesic connecting to and be geodesic connecting to . Hence, (11), (12) and (13) can be written as and , respectively. By applying the geodesic convexity of the Riemannian distance, we have arrived at the conclusion that

and

As a result, is a Fejér monotone with respect to . Lemma 3 (ii) states that is bounded. Therefore, there is a subsequence of that converges to a cluster point p. Following this, we will prove that

Fix and for . Let be a geodesic triangle with vertices , and , and be the corresponding comparison triangle. Then, we obtain and Let be the comparison point of . Using (ii) of Lemma 2 together with the expressions (14) and (15),

which implies that

Based on the fact that , so Summing up (18) from to , we obtain

Letting , we have

Hence,

Now, let be a geodesic triangle with vertices , and , and be the corresponding comparison triangle. Then, we obtain

Let be the comparison point of . Using (ii) of Lemma 2 and (14), then

Adding (20) into (17) and using (14), we get

Note that . Summing up (21) form to , we obtain

Taking , yields

Therefore,

Moreover, let represent a geodesic triangle with vertices , and , and be the corresponding comparison triangle. Then, we get

Let be the comparison point of . Using (ii) of Lemma 2, then

Combining (23) and (17), and using (15), yields

Note that . Taking the sum of (24) from to , we get

Letting , we have

This indicates that

With the help of the geodesic convexity of the Riemannian distance,

Taking into the last inequality and applying (25), we get

Because g is nonexpansive, then

In view of (25) and (26), we deduce that

Recall (12) that , we get

Letting to the above inequality and using (22), so

Now,

By taking into (29). Then, by combining (19), (26), (27) and (28),

Consider,

and

By letting , we are able to show that and . This proves that . According to Lemma 3 (iii), the sequence generated by Algorithm 3 converges to a common fixed point of g and h. As a result, the proof has been completed. □

4. Numerical Examples

We provide two numerical examples on Hadamard manifolds in order to illustrate the performance of Algorithm 3 and to evaluate its efficacy in comparison to other existing algorithms. All programs were coded in Matlab R2016b, and the computations were done on a personal computer with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i7 @1.80 GHz, together with 8 GB 1600 MHz DDR3.

Example 1.

Let be an Hadamard manifold with Riemannian metric and , where is matrix defined by

The Riemannian distance between any x and y in M is defined by

See [28] for further details. The geodesic joining the points and is given by

where , and

Therefore, where is the unique geodesic starting from with . To define the inverse exponential mapping, we use the following formula:

In the same vein as [35] [Example 5.1], we define two nonexpansive mappings by

and

Then, and . These imply that . Let and the initial point . Denoted as the stopping criterion. The five different cases of control parameters and are as follows:

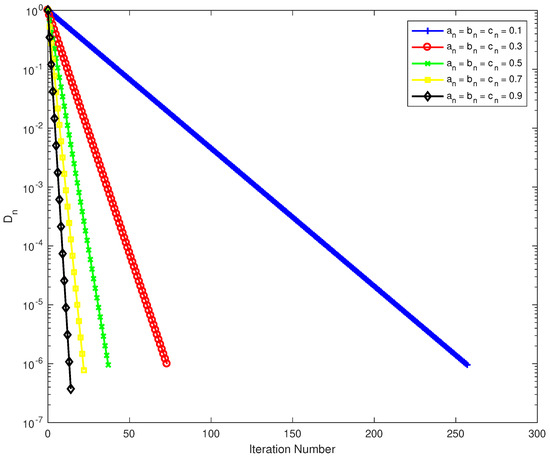

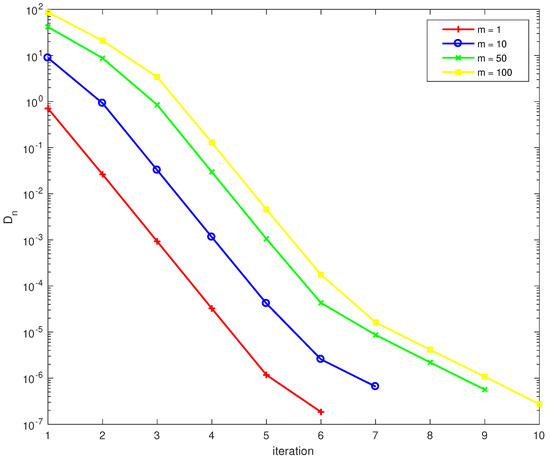

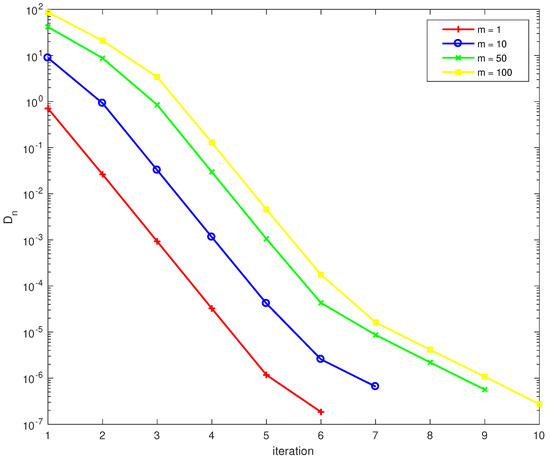

The numerical behavior of Algorithm 3 using different choices of control parameters is reported in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Table 1.

Numerical experiments of Example 1.

Figure 1.

Numerical behaviour of for Example 1.

Remark 1.

- (i)

- Table 1 shows that Algorithm 3 with different choices of control parameters is efficient and simple to implement. The most essential point is that Algorithm 3 converges quickly when the control parameter are .

- (ii)

- The speed of our proposed Algorithm 3 with the parameter is clearly faster than others, as can be seen in Figure 1.

Example 2.

for all Then, and We can see that .

Let be the 3−dimensional hyperbolic space endowed with the Lorentz metric of defined by

For richer details, see [36,37]. Then, is a Hadamard manifold with sectional curvature . The normalized geodesic starting from is defined as

where is unit vector. In light of this, we deduce that The inverse exponential map is assigned by

The Riemannian distance is defined by .

Let are nonexpansive mappings respectively defined by

and

In order to show the effectiveness of our Algorithm 3, we compare it to two others algorithms: S-iteration algorithm of rank 2 (7) and S-iteration algorithm of rank 3 (8). In Algorithm 3, we set . In S-iteration algorithm of rank 2 and S-iteration algorithm of rank 3, we take . Let and a random initial point

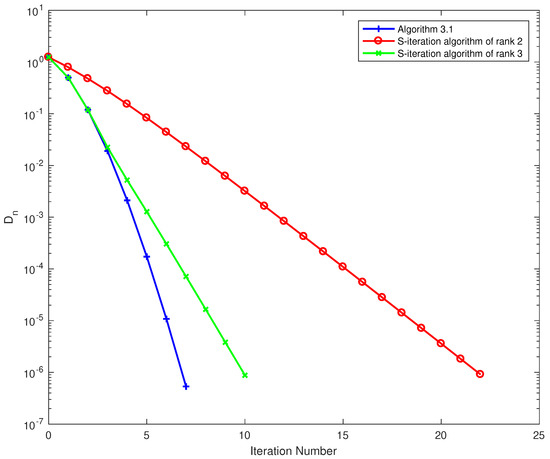

We denoted as the stopping criterion. The computational results of Algorithm 3, S-iteration algorithm of rank 2 and S-iteration algorithm of rank 3 are indicated in Table 2 and Figure 2 for the behavior of . It is seen that our proposed method converges faster than other iterative methods.

Table 2.

Numerical experiments of Example 2.

Figure 2.

Numerical behavior of for Example 2.

5. Applications

5.1. Inclusion Problems

Let be the set of all multivalued vector fields such that , and denote the domain of A defined by . Suppose that is a multivalued vector. A point is called a singularity of A such that . The set of all singularities of A is assigned by

Next, we recall concept of monotonicity for a multivalued vector field on Hadamard manifolds.

Definition 2

([38]).A vector field is said to be

- (i)

- monotone ifand

- (ii)

- maximal monotone if it is monotone and and , the condition

Li et al. [21] provided a definition for the resolvent of a multivalued vector field as well as a firmly nonexpansive mapping on Hadamard manifolds.

Definition 3

([21]).Given and let the multivalued vector field , the resolvent related to A of order λ is a multivalued map defined by

Remark 2

([21]).Assume that According to the definition of the resolvent, then the range of the resolvent is contained the domain of A and

Definition 4

([21]).A mapping is said to be firmly nonexpansive if for any two points , the function defined by

is nonincreasing.

According to the concept of firmly nonexpansive mappings, it is straightforward to deduce that all firmly nonexpansive mappings are nonexpansive. By the way, the monotonicity and the expansiveness are closely related to one another.

Theorem 2

([21]).Let a vector field . Then, the multivalued vector field A is monotone ⟺ is single-valued and firmly nonexpansive, .

Let be a geodesic convex function. We know that the subdifferential at x is closed and geodesic convex [33] and is defined as

The following lemma states that the subdifferential is maximal monotone vector field.

Lemma 4

([39]).Let be a proper lower semicontinuous geodesic convex function and Then, the subdifferential of g is a maximal monotone vector field.

Clearly,

where stands for the set of minimizers.

Here we consider an inclusion problem in the setting of Hadamard manifolds. Then the problem is to find such that

where . represents the solution set of the inclusion problem (32). In light of Remark 2, the challenge of finding singularities of A is transformed into the problem of finding fixed points of the mapping .

Next, we apply Algorithm 3 to find a common singularity of two multivalued monotone vector fields.

Theorem 3.

Let be multivalued monotone vector fields such that . Assume that and are real positive sequences satisfying and . Let and is defined by

where . Then, converges to an element in

Proof.

Set and . Form Theorem 2, g and h are single-valued and firmly nonexpansive mappings. Hence, they are nonexpansive mappings with and . From the hypothesis, Therefore, according to Theorem 1, we get the desired result. □

Now, we discuss a numerical experiment which support Theorem 3.

Example 3.

Let and . As [28], let be the Riemannian manifold with the Riemannian metric defined by and , where is a diagonal metrix defined by Tangent space at , denoted by . The Riemannian distance is defined by

Thus, is a Hadamard manifold. The exponential map on is given by

for and The inverse of the exponential map is assigned by

Let be a mapping defined by

where satisfy and for . The minimizer of g is , where for . Ferreira et al. [19] showed that g is a geodesic convex function in . Taking and , for , we obtain 1 as the minimizer of the mapping g. Let be a mapping defined by

It is easy to see that h is geodesic convex function, and 1 is the minimizer.

From (31), we have

and

The subdifferential and are maxiaml monotone vector fields, as shown by Lemma 4. Thus, we instead the multivalued monotone vector fields A and B by and , respectively. In addition to it, we have

and

Due to the fact that the minimizer of both g and h is 1, it is possible for us to observe that .

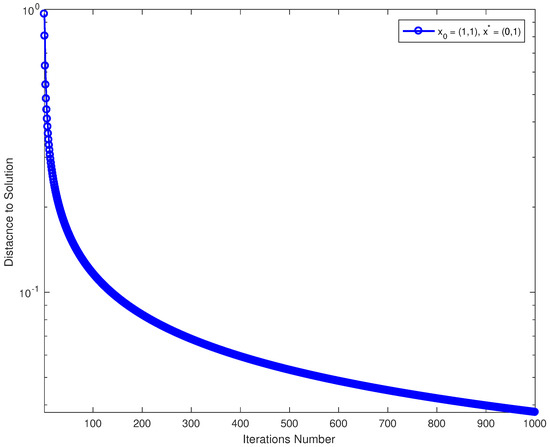

Choose , , and let . We take into account of the various of numbers for dimension m. Denoted as the stopping criterion. The initial values are randomly generated in MATLAB. Both Table 3 and Figure 3 include the numerical results that we obtained.

Table 3.

Numerical experiments of Example 3.

Figure 3.

Numerical behavior of for Example 3.

Remark 3.

- (i)

- Numerical experiments, as shown in Table 3, demonstrate that the proposed Algorithm (33) with different dimensional sizes converges to a common singularity of maximal monotone multivalued vector fields. Our method is efficient and simple to implement for solving the inclusion problem (32). Furthermore, the number of iterations required by Algorithm (33) is unaffected by the dimension selection; in fact, the number of iterations required by the proposed method is only slightly affected by the dimension leaping change.

- (ii)

- The functions g and h in the Example 3 are nonconvex functions in the Euclidean sense. Therefore, the iterative method [12] can’t be applied to solve the problem (32).

5.2. Convex Feasibility Problems

Suppose that C is a nonempty, closed and geodesic convex subset of M. The projection operator is defined by . We know that the projection operator is single-valued and firmly nonexpansive [21].

Let and are nonempty, closed and geodesic convex subsets of M such that . Since with and with are nonexpansive mappings. Therefore, . This means that finding an element in is analogous to finding a point in the intersection of two nonempty, closed and geodesic convex subsets of Hadamard manifolds.

Next, we apply Algorithm 3 to find a point in the intersection of two nonempty, closed, and geodesic convex subsets of Hadamard manifolds.

Theorem 4.

Let and are nonempty, closed, and geodesic convex subset of M such that . Assume that and are real positive sequences satisfying and . Let and is defined by

Then, converges to an element in

Proof.

Set and . Then, g and h are nonexpansive mappings with and . From the hypothesis, Therefore, according to Theorem 1, we get the desired result. □

Now, we discuss a numerical experiment which support Theorem 4.

Example 4.

Let be the Poincaré plane endowed with the Riemannian metric defined by

The sectional curvature of is equal to , and the geodesics of the Poincaré plane are the semilines and the semicircles or admit the following natural parameterizations:

see e.g., [33]. Furthermore, consider two points and in . Then, the Riemannian distance between y and z is defined by

where

To get the expression of , we consider a smooth geodesic curve φ joining y to z defined by

where and are respectively defined by

and

By the Riemannian metric endowed on (c.f. (35)), one checks that

see [32] (p. 7). Therefore, by elementary calculus, we get

It follows from [40] [Example 5.1], that we must let be closed convex subsets of defined as

and

From [33] (p. 301), and are convex because that is level set convex function defined by

and is a geodesic of , receptively. Moreover ,

and

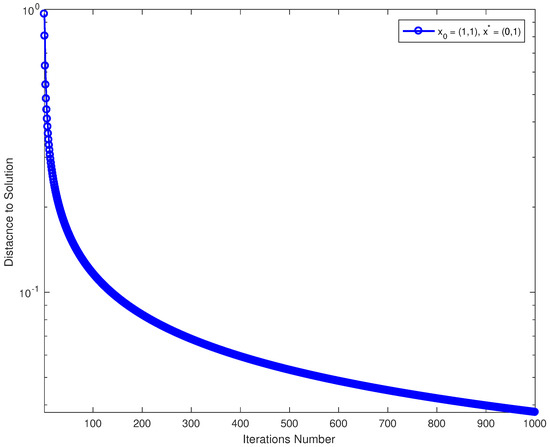

Choose and the initial point with . The computational results of Algorithm (34) are presented in Table 4 and Figure 4.

Table 4.

The numerical results of Algorithm (34).

Figure 4.

Distance to solution of each iteration number where the initial point is .

6. Conclusions

The problem of finding common fixed points of two nonexpansive mappings in the setting Hadamard manifolds is the subject of this research. Regarding the solution to this problem, a new three-step method is suggested. The proposed method has been shown to converge under certain assumptions. The effectiveness of the proposed method is shown by numerical examples.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K., P.C. and K.S.; methodology, K.K. and P.C.; software, K.K. and P.C.; validation, K.K., P.C. and K.S.; formal analysis, K.K., P.C. and K.S.; investigation, K.K., P.C. and K.S.; writing—original draft preparation, K.K., P.C. and K.S. writing—review and editing, K.K., P.C. and K.S.; visualization, K.K., P.C. and K.S.; supervision and funding acquisition, P.C. and K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research project is supported by The Science, Research and Innovation Promotion Funding (TSRI) (Grant no. FRB650070/0168). This research block grant was managed under Rajamangala University of Technology Thanyaburi (FRB65E0632M.1).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The first author would like to thank Faculty of Science and Technology, Rajamangala University of Technology Thanyaburi (RMUTT). The second author was supported by Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI) Basic Research Fund: Fiscal Year 2023. Moreover, the last author acknowledges the financial support provided by the Science, Research, and Innovation Promotion Funding (TSRI) (Grant no. FRB650070/0168). This research block grant was managed under Rajamangala University of Technology Thanyaburi (FRB65E0632M.1).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bauschke, H.H.; Combettes, P.L. Convex Analysis and Monotone Operator Theory in Hilbert Spaces, 2nd ed.; CMS Books in Mathematics/Ouvrages de Mathématiques de la SMC; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; p. xix+619, With a foreword by Hédy Attouch. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauschke, H.H.; Borwein, J.M. On projection algorithms for solving convex feasibility problems. SIAM Rev. 1996, 38, 367–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitkuan, D.; Kumam, P.; Martínez-Moreno, J. Generalized Halpern-type forward-backward splitting methods for convex minimization problems with application to image restoration problems. Optimization 2020, 69, 1557–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padcharoen, A.; Kumam, P.; Cho, Y.J. Split common fixed point problems for demicontractive operators. Numer. Algorithms 2019, 82, 297–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, E. Mémoire sur la théorie des équations aux dérivées partielles et la méthode des approximations successives. Journal de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées 1890, 6, 145–210. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, W.R. Mean value methods in iteration. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 1953, 4, 506–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, S. Fixed points by a new iteration method. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 1974, 44, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.P.; O’Regan, D.; Sahu, D.R. Iterative construction of fixed points of nearly asymptotically nonexpansive mappings. J. Nonlinear Convex Anal. 2007, 8, 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Sahu, V.K.; Pathak, H.K.; Tiwari, R. Convergence theorems for new iteration scheme and comparison results. Aligarh Bull. Math. 2016, 35, 18–42. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, B.S.; Thakur, D.; Postolache, M. A new iteration scheme for approximating fixed points of nonexpansive mappings. Filomat 2016, 30, 2711–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; López, G.; Martín-Márquez, V. Iterative algorithms for nonexpansive mappings on Hadamard manifolds. Taiwan. J. Math. 2010, 14, 541–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padcharoen, A.; Sukprasert, P. Nonlinear Operators as Concerns Convex Programming and Applied to Signal Processing. Mathematics 2019, 7, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, D.R.; Babu, F.; Sharma, S. The S-iterative techniques on Hadamard manifolds and applications. J. Appl. Numer. Optim. 2020, 2, 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, P.; Konwar, N.; Radenović, S. (Eds.) Metric Fixed Point Theory. Applications in Science, Engineering and Behavioural Sciences; Forum for Interdisciplinary Mathematics (FFIM); Springer: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorčević, V. Harmonic Quasiconformal Mappings and Hyperbolic Type Metrics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuri, S.A.; Louhichi, I. A novel Ishikawa-Green’s fixed point scheme for the solution of BVPs. Appl. Math. Lett. 2018, 82, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintunavarat, W.; Pitea, A. On a new iteration scheme for numerical reckoning fixed points of Berinde mappings with convergence analysis. J. Nonlinear Sci. Appl. 2016, 9, 2553–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.; Ali, F.; Kumar, P. Approximation of fixed points for Suzuki’s generalized non-expansive mappings. Mathematics 2019, 7, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, O.P.; Louzeiro, M.S.; Prudente, L.F. Gradient method for optimization on Riemannian manifolds with lower bounded curvature. SIAM J. Optim. 2019, 29, 2517–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, O.P.; Oliveira, P.R. Proximal point algorithm on Riemannian manifolds. Optimization 2002, 51, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; López, G.; Martín-Márquez, V.; Wang, J.H. Resolvents of set-valued monotone vector fields in Hadamard manifolds. Set-Valued Var. Anal. 2011, 19, 361–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, S.Z. Variational inequalities on Hadamard manifolds. Nonlinear Anal. 2003, 52, 1491–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisu, S.; Kumam, P.; Sriwongsa, S.; Abubakar, J. On minimization and fixed point problems in Hadamard spaces. Comput. Appl. Math. 2022, 41, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumam, P.; Chaipunya, P. Equilibrium problems and proximal algorithms in Hadamard spaces. J. Nonlinear Anal. Optim. 2017, 8, 155–172. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, W.; Shahzad, N. Fixed Point Theory in Distance Spaces; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; p. xii+173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisu, S.; Minjibir, M.S.; Kumam, P.; Sriwongsa, S. Convergence theorems for fixed points in CAT_p(0) spaces. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, R.L.; Dedieu, J.P.; Margulies, J.Y.; Martens, M.; Shub, M. Newton’s method on Riemannian manifolds and a geometric model for the human spine. IMA J. Numer. Anal. 2002, 22, 359–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Cruz Neto, J.X.; Ferreira, O.P.; Pérez, L.R.L.; Németh, S.Z. Convex- and monotone-transformable mathematical programming problems and a proximal-like point method. J. Glob. Optim. 2006, 35, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grohs, P.; Hosseini, S. Nonsmooth trust region algorithms for locally Lipschitz functions on Riemannian manifolds. IMA J. Numer. Anal. 2016, 36, 1167–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristály, A. Nash-type equilibria on Riemannian manifolds: A variational approach. J. Math. Pures Appl. 2014, 101, 660–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, T. Riemannian Geometry. In Translations of Mathematical Monographs; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1996; Volume 149, p. xiv+358, Translated from the 1992 Japanese original by the author. [Google Scholar]

- do Carmo, M.P.A. Riemannian geometry. In Mathematics: Theory & Applications; Birkhauser Boston, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 1992; p. xiv+300, Translated from the second Portuguese edition by Francis Flaherty. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udrişte, C. Convex Functions and Optimization Methods on Riemannians Manifolds. In Mathematics and Its Applications; Kluwer Academic Publishers Group: Dordrecht, the Netherlands, 1994; Volume 297, p. xviii+348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridson, M.R.; Haefliger, A. Metric spaces of non-positive curvature. In Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften [Fundamental Principles of Mathematical Sciences]; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; Volume 319, p. xxii+643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Homidan, S.; Ansari, Q.H.; Babu, F.; Yao, J.C. Viscosity method with a ϕ-contraction mapping for hierarchical variational inequalities on Hadamard manifolds. Fixed Point Theory 2020, 21, 561–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, O.P.; Pérez, L.R.L.; Németh, S.Z. Singularities of monotone vector fields and an extragradient-type algorithm. J. Glob. Optim. 2005, 31, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.J.; Huang, N.J. Korpelevich’s method for variational inequality problems on Hadamard manifolds. J. Glob. Optim. 2012, 54, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cruz Neto, J.X.; Ferreira, O.P.; Lucambio Pérez, L.R. Monotone point-to-set vector fields. Balkan J. Geom. Appl. 2000, 5, 69–79, Dedicated to Professor Constantin Udrişte. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; López, G.; Martín-Márquez, V. Monotone vector fields and the proximal point algorithm on Hadamard manifolds. J. Lond. Math. Soc. 2009, 79, 663–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, C.; Yao, J.C. Projection algorithms for convex feasibility problems on Hadamard manifolds. J. Nonlinear Convex Anal. 2016, 17, 483–497. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).