Abstract

In 1989, Chartrand, Oellermann, Tian and Zou introduced the Steiner distance for graphs. This is a natural generalization of the classical graph distance concept. Let be a connected graph of order at least 2, and . Then, the minimum size among all the connected subgraphs whose vertex sets contain S is the Steiner distance among the vertices of S. The Steiner k-eccentricity of a vertex v of is defined by , where n and k are two integers, with , and the Steiner k-diameter of is defined by . In this paper, we present an algorithm to derive the Steiner distance of a graph; in addition, we obtain a relationship between the Steiner k-diameter of a graph and its line graph. We study various properties of the Steiner diameter through a combinatorial approach. Moreover, we characterize graph when is given, and we determine for some special graphs. We also discuss some of the applications of Steiner diameter, including one in education networks.

Keywords:

Steiner distance; Steiner diameter; line graph; combinatorial thinking; education networks MSC:

05C05; 05C12; 05C76

1. Introduction

In this paper, all the graphs are assumed to be undirected, finite and simple. The degree of a vertex v in graph is denoted by . We denote by and the maximum and minimum degrees of the vertices of , respectively. A subdivision of is a graph obtained from by replacing edges with pairwise internally disjointed paths. We write when is the disjointed union of k copies of a graph H. As usual, by , , and , we denote, respectively, the cycle, path, star, and complete graph of order n. We also denote a complement graph of by . The connectivity of a graph is the minimum size of a vertex set V such that is disconnected. The edge connectivity of a graph is the minimum size of an edge set E such that is disconnected. The line graph of is the graph with vertex set , where two elements are adjacent in if and only if they correspond to two edges in sharing a common endpoint. Let and . Then for , the ℓ-th iterated line graph is defined by . We skip the definitions of other standard graph-theoretical notions, which can be found in, e.g., [1,2,3,4].

1.1. The Generalized Concept of Distance

One of the most fundamental ideas in graph-theoretic subjects is distance. Let be a connected graph with . Then the length of a shortest path between x and y is the distance . The eccentricity of any vertex v in is defined by . Moreover, the diameter and radius of are defined by and . These two graph invariants are related by the inequalities . The center of a connected graph is defined by .

The minimum size of a connected subgraph containing two vertices x and y in a connected graph is equal to the distance between these two vertices x and y. This observation suggests a generalization of distance. The Steiner distance of a graph, first proposed in 1989 by Chartrand, Oellermann, Tian and Zou [5], is a natural and nice generalization of the concept of classical graph distance. An S-Steiner tree, or a Steiner tree connecting S (or simply, an S-tree), is a tree of , for a graph and a set . Let S be a nonempty set of vertices of a connected graph . Then the Steiner distance among the vertices of S (or simply the distance of S) is the minimum size among all connected subgraphs whose vertex sets contain S. Note that if G is a connected subgraph of such that and , then G is a tree. Observe that , where T is a subtree of . In particular, if , then . If there is no S-Steiner tree in , then we assume that . For its basic mathematical properties including related results, see [6,7,8,9].

Observation 1.

Let Γ be a graph of order n with integer k such that . If and , then .

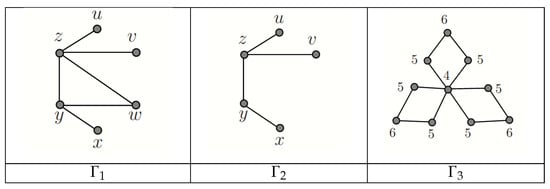

Let k and n be two integers such that . The Steiner k-eccentricity of a vertex u of is defined by . (If there are two graphs in the context, then we use instead of .) The Steiner k-radius of is , while the Steiner k-diameter of is . Note that for every connected graph , for all , and hence, and . Let be a graph in Figure 1. For any and , obviously, . If we take , then the Steiner tree of is (see Figure 1), and hence, we have . Moreover, each vertex of the graph in Figure 1 is labeled with its Steiner 3-eccentricity, so that .

Figure 1.

Three graphs , and .

Observation 2.

Let k and n be two integers, with.

If H is a spanning subgraph of Γ, then .

For a connected graph Γ, .

1.2. Background and Recent Progress

In 1971, Hakimi [10] and Levi [11] introduced the Steiner tree problem in graphs. For an undirected and unweighted graph , the problem is to find a minimal connected subgraph that contains the vertices in S, where . More specifically, the determination of a Steiner tree in a graph is a discrete analogue of the well-known geometric Steiner problem: Find the shortest possible network of line segments interconnecting a set of given points in Euclidean space. Researchers have studied the computational part of this problem and have found it an NP-hard problem for general graphs (see [4]).

Chartrand, Okamoto and Zhang [12] presented the following result.

Theorem 1

([12]).Let Γ be a connected graph of order n with integer k such that . Then . Moreover, the upper and lower bounds are sharp.

Mao et al. [13] studied the problem of determining the minimum size of a graph of given order, Steiner diameter and maximum degree. Mao et al. [14] studied the Steiner distance of Cartesian and lexicographic product graphs. Dankelmann et al. [15] presented an upper bound on : , where n is the order, and is the minimum degree of . Mao [16] gave the upper and lower bounds for the Steiner diameter of graphs.

The Steiner k-center of a connected graph is the subgraph induced by the vertices of minimum k-eccentricity in . According to Oellermann and Tian [17], every graph is the k-center of another graph. The Steiner k-median of is the subgraph of induced by the vertices of of minimum Steiner k-distance. We refer interested readers to [17,18,19] for further discussions of Steiner medians and Steiner centers.

Dankelmann, Oellermann and Swart [20] introduced the average Steiner distance of a graph . It is defined as

For mathematical properties on average Steiner distance, see [20,21] and the references therein.

Let be a k-connected graph, and . Let be a family of k vertex-disjoint paths between x and y, i.e., . Let be the number of edges of path such that . The k-distance between vertices x and y is the minimum among all , and the k-diameter of is defined as the maximum k-distance over all pairs of vertices of . The concept of k-diameter emerges rather naturally when one looks at the performance of routing algorithms. Several authors (Chung [22], Du, Lyuu and Hsu [23], Hsu [24,25], Meyer and Pradhan [26]) have studied and discussed applications of such notions as k-diameter to network routing in distributed and parallel processing.

In [27], Mao et al. obtained the following results, which are used later.

Lemma 1

([27]).Let Γ be a graph of order n. Then Γ is connected if and only if .

Lemma 2

([27]).Let Γ be a connected graph with n vertices. Then

Γ is 2-connected if and only if ;

Γ contains at least one cut vertex if and only if .

Lemma 3

([27]).Let Γ be a connected graph with vertices and connectivity κ. Then

if and only if ;

or Γ contains only one cut vertex if and only if ;

there are at least two cut vertices in Γ if and only if .

Lemma 4

([27]).Let Γ be a connected graph with n vertices and connectivity κ. Then

there are at least three cut vertices in Γ if and only if ;

if and only if .

If , then .

1.3. Three Problems

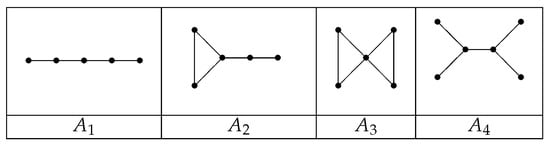

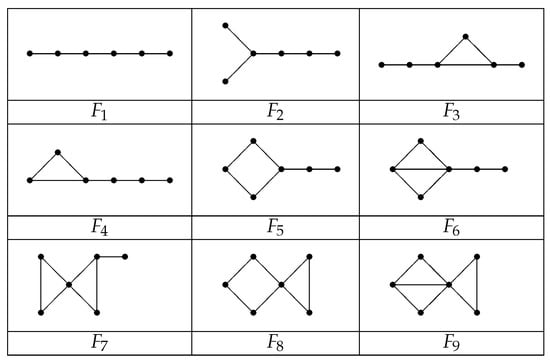

Let be the graphs shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The forbidden subgraphs .

In [28], Ramane et al. obtained the following results.

Theorem 2

([28]).Let Γ be a graph with . If Γ does not contain as its induced subgraph, then .

Theorem 3

([28]).Let Γ be a graph with . If Γ does not contain as its induced subgraph, then does not contain as its induced subgraph.

Theorem 4

([28]).Let Γ be a graph with . If Γ does not contain as its induced subgraph, then for ,

;

does not contain as its induced subgraph.

In this paper, to better understand this notion of the Steiner diameter of a graph and its associated line graphs, we propose and study the following problems.

Problem 1.

Let Γ be a graph with , and ℓ is an integer. Find some induced subgraphs such that if Γ does not contain such induced subgraphs, then .

Problem 2.

Find some induced subgraphs that characterize .

The following observation is immediate from Theorem 1.

Observation 3.

Let Γ be a connected graph with m edges. Then

In 1979, Bauer and Tindell [29] studied graphs with prescribed connectivity and line-graph connectivity.

Theorem 5

([29]).For each , , there is a graph such that and .

Li and Mao [30] investigated this problem for generalized connectivity. In this paper, we consider the same problem for distance-edge-monitoring numbers.

Problem 3.

For each , , is there a graph such that and ?

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we present an algorithm to derive the Steiner distance of graph . In Section 3, we obtain a relationship between the Steiner k-diameter of a graph and its line graph and provide a solution to Problem 1. In Section 4, we characterize the graphs when is given and provide an initial solution to Problem 2. In Section 5, we determine for some special graphs , including cycles, paths, complete graphs, fan graphs and friendship graphs, and provide a solution to Problem 3; and finally, in Section 6, we discuss some applications of these aforementioned results, as well as the combinatorial approach that we applied in our studies.

2. A Steiner Tree Construction Algorithm

As pointed out in [31], this Steiner problem in networks was originally formulated in [10], where a straightforward algorithm was suggested: a solution to this problem can be found by the enumeration of the minimum spanning trees (MSTs) of subnetworks of induced by subsets W of V such that Although algorithms for the MST problem do exist [32,33], it is well known that there are an exponential number of subsets in Thus, this straightforward algorithm takes an exponential amount of time to finish. Many algorithms following different approaches, together with heuristics, for a more general problem when the involved graph is weighted, i.e., all the edges come with positive weights, have been presented in, e.g., [31]. Although some of these approaches do lead to a polynomial solution for some special classes of graphs/networks, they all lead to exponential algorithms in the general case. Indeed, the problem of finding the Steiner distance of a set of vertices, the Steiner Problem, is NP-complete [3,34]. On the other hand, to expose a constructive nature for finding this important quantity, we describe an alternative algorithm to find the Steiner distance for a given in a graph

Calling any graph with just one vertex trivial, non-trivial otherwise [1], we start with the following well-known result.

Lemma 5

([1]).Every non-trivial tree has at least two leaves.

Corollary 1.

A graph is a tree iff, for some vertices is a tree, and v is a leaf.

Proof.

The sufficiency follows from Lemma 5. Let v be one of the two leaves, has to be both connected and cycle free, otherwise, it would contradict the assumption that is a tree itself. Regarding the necessity, assume is a tree; then by definition of a tree, it is connected and contains no cycle. It is clear that with the additional edge connecting u and is still connected and cycle free, and is thus a tree. □

Given a graph the following algorithm Tree as shown in Algorithm 1, returns true if vertices in W form a tree in Let W be

| Algorithm 1: Algorithm Tree |

1. If 2. //An isolated vertex is a tree 3. return True 4. Else 5. For 6. If 7. For 8. If is adjacent to only one 9. // is a leaf in W 10. return True 11. //No such a leaf exists 12. return False |

In terms of complexity, let be the number of checks we need to do in Line 8 or the constant operation that we need to do in Line 1. It is clear that When with the worst-case scenario, we have to go through a loop m times in Line 5; for each loop, we have to recursively call Tree , for which we have to go through another loop in Line 7 times. Hence,

It is thus easy to see that

By the following Stirling’s approximation,

where e refers to the natural logarithm 2.71828..., we may conclude that

We are now ready to present a Steiner algorithm in Algorithm 2, by definition, to construct a Steiner tree in a graph We notice the remark that we quoted in Section 1.1, “...if is a connected subgraph of such that and then G is a tree. Obviously, if then is simply the classical distance between u and ” [14].

| Algorithm 2: Steiner algorithm |

0. Given , and 1. 2. // Initially set St to infinite, by definition in the DMTC paper 3. for 4. // With the number of the vertices to be added. 5. // Since we want to get the minimum size, we start with 0 and go up. 6. //We quit in Line 12 as soon as we find a Steiner tree. 7. Choose a subset , , is a subset of V-S 8. // Notice that the number of is . 9. If //If the so-chosen set is a tree, we 10. //are done, and the size of this tree is . 11. 12. break 13. return 14. //If none of the vertex subsets satisfy the condition in 9, 15. we return ∞. |

When applying the Steiner algorithm to as shown in Section 1.1, we start by picking in Line 3; in Line 7 since Tree() returns True (In Tree(S, E)), let Tree(E) returns True; and since v is only adjacent to we are done. is set to 1 in Line 11, and it then breaks in Line 12 and returns 1 in Line 13.

In terms of complexity, the best scenario is that the loop in Line 3 runs only once; i.e., when S itself is a Steiner tree with edges in then its complexity is the same as that of Tree(), i.e., .

The worst case is that is a Steiner tree itself, or it does not contain any Steiner tree, in which case the algorithm will have to go through all the subsets of In this worst case, the inner loop in Line 2 and the outside loop in Line 7 would cost altogether Since, as mentioned earlier, this Steiner problem is NP-complete, there is no way to significantly improve the efficiency of such an algorithm.

3. Steiner Diameter of a Graph and Its Line Graph

In this section, we address Problems 1 and 2, as suggested in Section 1.3. Chartrand and Steeart [35] investigated the relation between the connectivity and edge-connectivity of a graph and its line graph.

Lemma 6

([35]).Let Γ be a connected graph with connectivity κ and edge-connectivity λ. Then

if ;

;

.

The following result is immediate from Theorem 1.

Proposition 1.

Let be two integers with or . Additionally, let Γ be a connected graph of order n, and Γ is not a tree. Then , and .

Proof.

Since is a connected graph of order n, we have is a connected graph with . It follows that . From Theorem 1, we have , and . □

For , we have the following result.

Proposition 2.

Let Γ be a connected graph of order n with edge-connectivity λ and integer k such that .

For , then .

If , there exists only one cut edge in Γ; then .

If and there exist at least two cut edges, then .

Proof.

For , since , by Lemma 6, we have . Using this result with Lemmas 3 and , we obtain .

Suppose and there exists only one cut edge in . Then we have , and there exists only one cut vertex in . From of Lemma 3, we have , as desired.

Suppose and there exist at least two cut edges in . Then there exist at least two cut vertices in . From Lemma 3, we have , as desired. □

Proposition 3.

Let Γ be a connected graph with n vertices and edge connectivity λ. If , then . Moreover, the bound is sharp.

Proof.

Since , it follows from of Lemma 6 that . If , then from Lemma 4 (3), we have , as desired. Otherwise, . From Lemma 4 (2), we have . This completes the proof of the result.

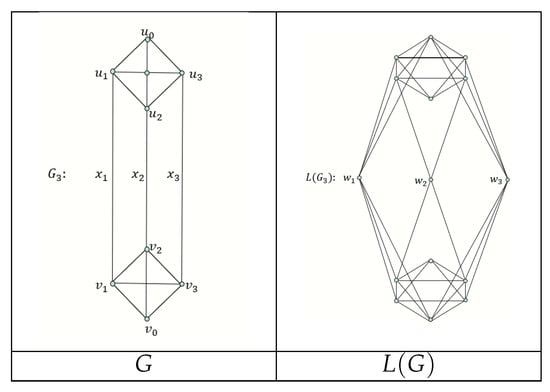

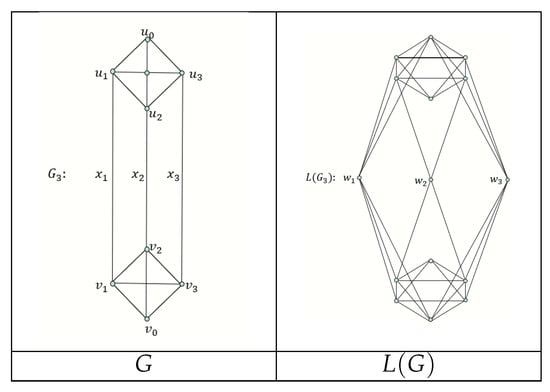

Moreover, if we take (see Figure 3), then we obtain . It follows from Lemma 4 (3) that we have , as desired. □

Figure 3.

Graph G and its line graph .

We now focus our attention on the case of . We now introduce nine graphs (see Figure 4), which are used later.

Figure 4.

Graphs .

- Let be a path of order 6;

- Let be the graph obtained by identifying a vertex of degree 2 in the 3-vertex path with one end vertex of the 4-vertex path;

- Let be the graph obtained by identifying a vertex of a cycle with one end vertex of the 3-vertex path and identifying the other vertex of this cycle with one end vertex of the 2-vertex path;

- Let be the graph obtained by identifying a vertex of a triangle with one end vertex of the 4-vertex path;

- Let be the graph obtained by identifying a vertex of a 4-vertex cycle with one end vertex of the 3-vertex path;

- Let be the graph obtained by identifying a vertex of degree 3 in with one end vertex of the 3-vertex path, where denotes the graph obtained from by deleting one edge;

- Let be the graph obtained by identifying a vertex of degree 2 of with one vertex of the 2-vertex path, where is the graph obtained by identifying a vertex of a triangle with one vertex of another triangle;

- Let be the graph obtained by identifying a vertex of 4-vertex cycle with one vertex of a triangle;

- Let be the graph obtained by identifying a vertex of degree 3 in with one vertex of a triangle, where denotes the graph obtained from by deleting one edge.

The following result provides a solution to Problem 1; that is, given a graph with , we want to find some induced subgraphs such that if does not contain such induced subgraphs, then .

Theorem 6.

Let Γ be a connected graph with . If Γ contains neither nor as its induced subgraph, then .

Proof.

Let be the edges of a graph . These are all the vertices of . Let , where . Note that are three edges in . First, we assume that is connected. This means that if one of them, say , is adjacent to the other two edges, then vertex is adjacent to both vertex and vertex in . Thus, the tree T induced by the edges in is an S-Steiner tree in , which implies , as desired.

Next, we assume that is disconnected. We now may assume that or . Since does not contain as its induced subgraph, we only need to consider the case . Let be adjacent to in , and let be adjacent to neither nor in . Set , and . Suppose that one vertex in is adjacent to one vertex in . Without loss of generality, let . Then the tree T induced by the edges in is an S-Steiner tree in , and hence , as desired. Suppose that none of are adjacent to one vertex in . Since , it follows that there exists a vertex such that w is adjacent to one vertex in and w is adjacent to one vertex in . By symmetry, we may assume that or . Table 1 shows the edges between w and one element in . By Figure 4, subgraphs induced by the vertices in are shown in Table 1. Note that and contains as its subgraph. If contains neither nor as its induced subgraph, then . □

Table 1.

Edges between w and vertices in of and .

4. Line Graphs with Steiner Diameter

The following observation is immediate.

Observation 4.

Let Γ be a connected graph with vertices and m edges. Then if and only if for any and , the subgraph induced by the edges in S is connected.

Proposition 4.

Let Γ be a connected graph with n vertices, and . Then if and only if .

Proof.

If for , then . Conversely, let . We have to prove that . Since is connected, it follows that contains a spanning tree, say T. If T is not a star, then there exists a non-leaf edge e. We choose k edges from different components of . Then the subgraph induced by these k edges is not connected, contradicting Observation 4. Thus T is a star. Note that is a graph obtained from T by adding some edges. Suppose that u is the center of T. We claim that is a star. Otherwise, let be an edge of Then is a spanning tree but is not a star, which is a contradiction. This completes the proof of the result. □

Proposition 5.

Let Γ be a unicycle graph of order n with integer s . Then if and only if , where is a cycle plus hanging edges into the cycle randomly.

Proof.

If is , then it follows from Observation 4 that . Conversely, let . Since is a unicyclic graph, it follows that contains a cycle, say . We claim that the edge must be a pendant edge. Otherwise, we can find a path , and . Then there exists a non-leaf edge . We choose edges from . Then the subgraph induced by these edges is not connected, contradicting Observation 4. Thus, we have . □

Proposition 6.

Let Γ be a connected graph with size m and for all . Then if and only if .

Proof.

From Lemma 2, if and only if is 2-connected. If , then it follows from Lemma 6 that , and so .

Conversely, let ; thus . If there exists a cut edge e in , it follows that e is a cut vertex in , which means that , which is a contraction. Hence, . □

The following result provides a first step to address Problem 2, i.e., finding some induced subgraphs that characterize when .

Corollary 2.

Let Γ be a connected graph with vertices. Then if and only if Γ satisfies one of the following conditions:

• for ;

• for ;

• for .

5. Results for Some Special Graphs

For any graph with positive integer k, we now explore the relationship between and as follows:

Lemma 7.

For any graph Γ with positive integer , we have

with equality if and only if or .

Proof.

For , and , and hence ; the equality holds. We already mentioned in Section 1.1, that . For , the equality thus also holds. Otherwise, and . For any , we have . Let be any set of vertices with . First, we have to prove that

Let T be a spanning tree of graph . For , as . The strict inequality (1) holds. We now assume that . We prove the result (1) by mathematical induction on k. Assume that the result in (1) holds for k and prove it for . For this, let be any set of vertices with such that . Then, there exists a vertex w in S such that . Therefore, by the mathematical induction hypothesis with the above result, we obtain

as . Hence, the result (1) holds by induction when and . It follows that with equality if and only if or . □

Theorem 7.

Let k, n be two integers.

Let Γ be a path , and , .

Let Γ be a cycle , and , .

Let Γ be a star , and , .

Proof.

Let and . By the definition of a line graph . By Observation 3, we have . We can assume that is a set of vertices with such that . Then, we have . It follows that and hence .

Since , we obtain .

Since , we obtain . □

From Theorem 7 , we have the following observation.

Observation 5.

Let be a cycle, and also let be positive integers. Then

Proof.

From Theorem 7 , we have . Thus, we have

□

The friendship graph, , can be constructed by joining n copies of the complete graph with a common vertex, which is called the universal vertex of .

Theorem 8.

Let be a friendship graph with two positive integers k and n. Then

Proof.

Let . Further, let and , where is its universal vertex. We consider the following three cases:

- : . Let or or , where . If , then . Otherwise, or or . Then . Hence, .

- : . Let such that . Then, the subgraph induced by the edges in is an S-Steiner tree; hence, , and so .

For any , if , then the subgraph induced by the edges in is an S-Steiner tree, and hence . If , then the subgraph induced by the edges in , and so ; hence . Therefore, .

- : . Then, it follows from Theorem 1 that . □

Theorem 9.

Let k, n be two positive integers. Then,

Proof.

Let , , and . For any , we have , , and

We consider the following cases:

- : . First we assume that there is a set S with such that . Then, .

Next, we assume that ; that is, . It follows from that , and hence .

- : , and is even. Let . For any with , let , and . One can easily see that . Clearly, , and . Since , we have , and hence, . Therefore . Since , it follows that there exists a vertex or . If and where , then from (2), we have or . If or , then, . Thus we obtain

Since S is any subset in with , we have .

Let . Then , and therefore . Hence, .

- : and is odd. Let . For any and and , there exists a vertex or . Similarly, as in the proof of , we define D, and . One can obtain easily that , , , , and . From (2), we obtain

Therefore, .

Let . Then, , and hence .

- : . Since , it follows from Lemmas 2 and 3 that . □

Theorem 10.

Let be a complete bipartite graph. Then,

Proof.

Let and , where and . For any , let and , where , and .

- : . First, we assume that there is no such that and . Without loss of generality, we can assume that if , there is a Steiner tree, T, obtained from such that . It follows that .

Next, we assume that there exists such that and . Then, we find a Steiner tree T such that . Thus, . It follows that for with , we have , and hence, .

- : . By the Nestle principle, there exists an such that and . Similar to , , , and hence , which means . From Observation 3, , and hence, . □

Theorem 11.

Let be a complete graph of order n with positive integer k. Then

Let . Further, let t be a positive integer such that , where . Then .

Proof.

Let . Then . For any edge , we have

Let M be a perfect matching or almost perfect matching in . Then .

- : . Let with . Recall that a Steiner tree connecting S is defined as a subgraph of , which is a subtree satisfying . Then , and hence, .

One can easily see that . Together with Lemma 7, we obtain . Hence, .

- : . Let . We denote by , . Let be a subset of with . First, we assume that . Then C is a vertex cut of . Let . Then .

Next, we assume that . For any with , one can easily obtain that . Then .

- : . We have , and hence, is connected for any , where and . Therefore, contains a spanning tree T of order , and hence, .

We now assume that and , where . Let . We denote by the edge set of the subgraph induced by the edges in . Let be the set of edges from to in .

Let be the number of edges in . Then and . It follows that

Thus, we have . Since , then we consider a set , where and . By Observation 4, we have

and hence . This completes the proof of the theorem. □

A general fan graph is defined as the graph join . We denote fan graph by .

Theorem 12.

Let be a fan graph of order n with positive integer k. Then

Proof.

Let and .

- : . Let with . First, we assume that . Let , where . Then, the subgraph induced by the edges in is an S-Steiner tree of , and hence .

Next, we assume that . In this case, let , where . Then, the subgraph induced by the edges in is an S-Steiner tree of , and hence, . From the above result, one can easily see that for , and . Hence, for .

- : . First, we assume that for . Then, the subgraph induced by the edges in is an S-Steiner tree, and hence, . Next, we assume that . Then, the subgraph induced by the edges in is an S-Steiner tree, and hence, . From Theorem 1, we have , and hence, .

- : . Then it follows from Lemma 1 that . □

Theorem 13.

Let be a fan graph of order with positive integer k. Then

Proof.

Let . Additionally, let and . For any , we have , and

and

- : . Since , we have .

First, we assume that there is a set S with such that . From and , we obtain .

Next, we assume that . Then, one can easily see that . If we take , then we obtain , and so .

- : . Since , it follows from Lemma 4 that .

- : . Since , it follows from Lemmas 2 and 3 that . □

We obtain the relation between the diameter of the line graph and the cardinal of vertex set S as follows.

Observation 6.

For any Γ and integer k, we have

Moreover, the bound is sharp.

Proof.

From Observation 3 and Lemma 7, we have

□

We now address Problem 3 that we proposed in Section 1.3; that is, for integer , , is there a graph such that and ?

In Table 2, we present some graphs such that and , which starts to provide a solution to Problem 3; that is, for each , is there a graph such that and ?

Table 2.

and .

We indeed have the following general observations. For any graph , let and . Then

Observation 7.

Let Γ be a connected graph with . Then

Proof.

For any vertex , we can assume that such that . Let . Clearly, , and hence . □

Observation 8.

Let Γ be a graph of order n with positive integer k such that . Then

Moreover, the lower bound is sharp.

Theorem 14.

Let Γ be a graph of order n with size and positive integer k such that . Then

Moreover, the bound is sharp.

Proof.

From Observation 3, we have . From Theorem 1, we have , and hence, .

Let . From Observation 5, the lower bound is sharp. If , then the upper bound is sharp. □

6. Applications

During an economic debate on social networking technologies in education, Vicki A. Davis proposed the concept of education networks [36,37], where Steiner trees may find application. For instance, one may want to connect certain kinds of educational resources in a subnetwork that uses the smallest number of communication links. To do this, one needs a Steiner tree for the vertices of the subnetwork corresponding to the educational resources that need to be connected.

Combinatorial thinking, also known as “connected thinking” or “combined thinking”, is a way of thinking in which a number of seemingly unrelated things are connected so that they become a new and inseparable whole. Combinatorial thinking is innovative, contemporary and inheritable. Forms of combinatorial thinking include homogeneous combination, heterogeneous combination, recombination combination, shared substitution and concept combination.

Mathematics education researchers Rezaie and Gooya [38] speculated on the claim that learning combinatorial concepts requires a special way of thinking, and by reviewing the related literature in this area, they found that some researchers acknowledged this speculation and called it combinatorial thinking. In 2002, Graumann [39] regarded combinatorial thinking as a tool for solving problems when he was experimenting with children doing geometrical tasks.

As a more specific example related to the technical results that we report in this paper, graph operations such as line graphs are motivated by the desire to “construct” graphs with established properties to obtain new graphs that inherit those properties. From Proposition 2, we can get an upper bound of from the upper bound of . One can also see from Theorem 5 that both and hold. The teaching of graph operations is thus a good example for training combinatorial thinking ability.

7. Concluding Remarks

In this paper, we derived an algorithm to calculate the Steiner distance. Next, we provided a solution to Problem 1: that is, given a graph with , we wanted to find some induced subgraphs such that if did not contain such induced subgraphs, then , where . We also obtained a relationship between the Steiner k-diameter of a graph and its line graph and studied various properties of the Steiner diameter through a combinatorial approach. In addition, we obtained Steiner diameters for some special graphs. Moreover, whether for each , , there exists a graph such that and is still open; we got several results, as shown in Table 2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L., Z.S., C.Y. and K.C.D.; investigation, H.L., Z.S., C.Y. and K.C.D.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L., Z.S., C.Y. and K.C.D.; writing—review and editing, H.L., Z.S., C.Y. and K.C.D. All authors have read and agreed to the submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

C.Y. is supported by the National Science Foundation of China (no. 12061059). K.C.D. is supported by the National Research Foundation funded by the Korean government (grant no. 2021R1F1A1050646).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bondy, J.A.; Murty, U.S.R. Graph Theory; GTM 244; Springer: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, F.; Harary, F. Distance in Graphs; Addision-Wesley: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Garey, M.R.; Johnson, D.S. Computers and Intractibility: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness; Freeman & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, F.K.; Richards, D.S.; Winter, P. The Steiner Tree Problem; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Chartrand, G.; Oellermann, O.R.; Tian, S.; Zou, H.B. Steiner distance in graphs. Časopis Pěstování Matematiky 1989, 114, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y. Steiner distance in graphs-a survey. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.05779. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Y.; Das, K.C. Steiner Gutman index. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem. 2018, 79, 779–794. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Das, K.C. Steiner degree distance of two graph products. Analele Stiintifice Univ. Ovidius Constanta 2019, 27, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Mao, Y.; Das, K.C.; Shang, Y. Nordhaus-Guddum type results for the Steiner Gutman index of graphs. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakimi, S.L. Steiner’s problem in graph and its implications. Networks 1971, 1, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, A.Y. Algorithm for shortest connection of a group of graph vertices. Sov. Math. Dokl. 1971, 12, 1477–1481. [Google Scholar]

- Chartrand, G.; Okamoto, F.; Zhang, P. Rainbow trees in graphs and generalized connectivity. Networks 2010, 55, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Dankelmann, P.; Wang, Z. Steiner diameter, maximum degree and size of a graph. Discret. Math. 2021, 344, 112468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Cheng, E.; Wang, Z. Steiner distance in product networks. Discret. Math. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2018, 20, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Dankelmann, P.; Swart, H.; Oellermann, O.R. (Kalamazoo, M.I., 1996); Bounds on the Steiner Diameter of a Graph; Combinatorics, Graph Theory, and Algorithms; New Issues Press: Kalamazoo, MI, USA, 1999; Volume I–II, pp. 269–279. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Y. The Steiner diameter of a graph. Bull. Iran. Math. Soc. 2017, 43, 439–454. [Google Scholar]

- Oellermann, O.R.; Tian, S. Steiner centers in graphs. J. Graph Theory 1990, 14, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oellermann, O.R. From steiner centers to steiner medians. J. Graph Theory 1995, 20, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oellermann, O.R. On Steiner centers and Steiner medians of graphs. Networks 1999, 34, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankelmann, P.; Oellermann, O.R.; Swart, H.C. The average Steiner distance of a graph. J. Graph Theory 1996, 22, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankelmann, P.; Swart, H.C.; Oellermann, O.R. On the average Steiner distance of graphs with prescribed properties. Discret. Appl. Math. 1997, 79, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, F.R.K. Diameter of graphs: Old problems and new results. In Proceedings of the 18th Southeastern Conference on Combinatorics, Graph Theory and Computing, Boca Raton, FL, USA, 23–27 February 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Du, D.Z.; Lyuu, Y.D.; Hsu, D.F. Line digraph iteration and connectivity analysis of de Bruijn and Kautz graphs. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1993, 42, 612–616. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, D.F. On container width and length in graphs, groups, and networks. IEICE Trans. Fundam. Electron. Commun. Comput. Sci. 1994, E77-A, 668–680. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, D.F.; Łuczak, T. Note on the k-diameter of k-regular k-connected graphs. Discret. Math. 1994, 133, 291–296. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, F.J.; Pradhan, D.K. Flip trees. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1987, 37, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Melekian, C.; Cheng, E. A note on the Steiner (n-k)-diameter of a graph. Int. J. Comput. Math. CST 2018, 41, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramane, H.S.; Revankar, D.S.; Gutman, I.; Walikar, H.B. Distance spectra and distance energies of iterated line graphs of regular graphs. Publ. Inst. Math. 2009, 85, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, D.; Tindell, R. Graphs with prescribed connectivity and line graph connectivity. J. Graph Theory 1979, 3, 393–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Mao, Y. A result on the 3-generalized connectivity of a graph and its line graph. Bull. Malays. Math. Sci. Soc. 2018, 41, 2019–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, P. Steiner problem in networks: A Survey. Networks 1987, 17, 129–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, J.B. On the shortest spanning subtree of a graph and the traveling salesman problem. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 1956, 7, 48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prim, R.C. Shortest connection networks and some generalizations. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1957, 36, 1389–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, R.M. Reducibility among combinatorial problems. In Complexity of Computer Computations; Miller, R.E., Thatcher, J.W., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1972; pp. 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Chartrand, G.; Steeart, M. The connectivity of line graphs. Math. Ann. 1969, 182, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, J.A. Thinking more deeply about networks in education. J. Educ. Chang. 2010, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liang, J.; Das, K.C. Extra connectivity and extremal problems in the education networks. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaie, M.; Gooya, Z. What do I mean by combinatorial thinking? Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 11, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graumann, G. General Aims of Mathematics Education Explained with Examples in Geometry Teaching; The Mathematics Education into the 21st Century Project: Palermo, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).