Abstract

We axiomatize strictly positive fragments of modal logics with the confluence axiom. We consider unimodal logics such as , , and with unimodal confluence as well as the products of modal logics in the set , which contain bimodal confluence . We show that the impact of the unimodal confluence axiom on the axiomatisation of strictly positive fragments is rather weak. In the presence of , it simply disappears and does not contribute to the axiomatisation. Without it gives rise to a weaker formula . On the other hand, bimodal confluence gives rise to more complicated formulas such as (which are superfluous in a product if the corresponding factor contains ). We also show that bimodal confluence cannot be captured by any finite set of strictly positive implications.

MSC:

03B45; 06B15

1. Introduction

Strictly positive modal formulas are constructed of propositional variables and the constant ⊤ using only conjunction and diamonds. Strictly positive logics consists of implications between strictly positive modal formulas. They were studied in the context of universal algebra [1], knowledge representation [2,3] and proof theory [4,5,6].

In this paper, we investigate strictly positive fragments of modal logics that include the confluence axiom and its bimodal counterpart . The confluence axiom is an example of a simple but very useful formula. It appears in very different areas of modal logic, ranging from epistemic logic to the logic of space-time (cf. [7]) and the logic of forcing [8]. Bimodal confluence is valid in any product of two Kripke frames and plays an important role in multidimensional modal logic [9]. When stands for and stands for , bimodal confluence turns into the principle , which is one of the basic axioms of first-order logic.

For a modal logic L by , we denote its strictly positive fragment; that is, the set of all strictly positive implications in L. The modal calculus can be easily modified to work only with strictly positive implications yielding a natural calculus . The question of whether, given a strictly positive implication , axiomatises was thoroughly investigated in [10]. For example, this is true for and but not for . The confluence axiom cannot be rewritten as a strictly positive implication. This raises the question of how this axiom is reflected in strictly positive fragments of modal logic that contain it. This question is highly non-trivial. For example, Svyatlovskii showed in [11] that the strictly positive fragment of is axiomatised by and , which is a rather unexpected transformation of .3 axiom (undefinable as a strictly positive implication as well as confluence axioms, see Section 9.1 of [10]).

In this paper, we show that the impact of the unimodal confluence axiom on the axiomatisation of strictly positive fragments is rather weak. In the presence of , it simply disappears and does not contribute to the axiomatisation. Without it changes into a weaker formula . Some may find it unsurprising, but in our opinion, this is a remarkable property of the unimodal setting. In contrast, we show that the strictly positive fragment of is axiomatised by an infinite set of formulas of the form and , and that it cannot be captured by any finite set of strictly positive implications. We also show that strictly positive fragments of two-dimensional products of modal logics in the set also are axiomatised by these two infinite series of formulas, except for the cases when one or both of the factors contain , in which case some or all of these formulas become superfluous and can be omitted.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Basic Modal Logic

Let be a countable set of proposition letters, with typical members denoted by p, q, etc. Modal formulas over are built using the constants ⊤ and ⊥, dual-modal operators ⋄ and □ and (classical) binary connectives ∨ and ∧ and →.

A normal modal logic is a set L of formulas that contains all classical propositional tautologies, the formula , and that is closed under the standard rules Modus ponens, Uniform substitution and Generalization (given infer ). The smallest normal modal logic is denoted by . For a set of modal formulas and a modal logic L, denotes the smallest normal modal logic containing . For a modal formula, , .

As usual, a Kripke frame is a pair , where W is a non-empty set of worlds and R is a binary relation on W (that is ). Sometimes, we refer to the W- and R-components of as and . A point u in W is called final in F if u has no R-successors. A (Kripke) model based on F is a pair , where V is a function assigning to each proposition letter p a subset of W. The inductive definition of the truth value of a formula at a point x in a model M is standard. The fact that is true at x in M is denoted by . In particular, boolean connectives are computed by classical truth tables within a point, if there is a point such that and if for all points y such that we have .

A formula is said to be true in a model, in symbols , if is true at all worlds in W; is valid in a frame F, in symbols , if is true in all models based on F.

Each class of Kripke frames gives rise to a normal modal logic . It is known (cf. [12]) that is the logic of all Kripke frames satisfying .

In addition to , we consider the logics

Their axioms , and are strictly positive implications and correspond to conditions , and in the same way as corresponds to .

2.2. Strictly Positive Implications

A strictly positive term (or sp-term) is a modal formula constructed from propositional variables, the constant ⊤, conjunction ∧, and the unary diamond operator ⋄. An SP-implication takes the form , where and are SP-terms. An SP-logic is a set of SP-implications that contains formulas

and is closed under uniform substitution (of sp-terms for propositional variables) and rules

(see also the Reflection Calculus of [4,5]). For an sp-implication , denotes the smallest SP-logic containing . By , we denote the natural modification of for strictly positive implications with two modal operators and with two versions of the third rule for each of the two diamonds. It is easy to see that the rule

is admissible in .

For a normal modal logic , the strictly positive fragment of is

It is easy to check that is an SP-logic.

Given an sp-term , we define by induction a Kripke model based on a finite tree with root . For , consists of a single irreflexive point with for all variables p. For , consists of a single irreflexive point , , and for . For , we first construct disjointed and , and then merge their roots and into r such that iff , for some . Finally, for , we add a fresh point r to , and set and for all variables p. We refer to as the -tree model.

Given two Kripke models, and , a map is a homomorphism from into if it satisfies the following conditions:

- for all in , if , then

- for all x in and propositional variables p, implies

Proposition 1.

For any sp-term t, Kripke model M and point w in M, we have if there is a homomorphism with .

Proposition 2.

For any sp-terms s and t, the implication is derivable in if there is a rooted homomorphism from into .

Propositions 1 and 2 are well known and can be shown by induction on the length of the sp-term t. Proposition 2 can also be obtained as a consequence of a representation theorem for semilattices with monotone operators [13], but this is outside of the scope of this paper, where we prefer to approach the completeness of -based calculi syntactically whenever it is possible.

2.3. The Chase

A tuple-generating dependency [14] is a first-order formula of the form

where , and are disjoint tuples of variables and and are possibly empty conjunctions of R-atoms in respective sets of variables. We call the body and the head of the corresponding TGD. Examples of TGDs include and

For a conjunction of R-atoms (with variables and without constants) we introduce constants for all object variables v in and set where and .

Given a Kripke frame trigger h for a TGD of the form (4) is a homomorphism from into F. Trigger h is good if h cannot be extended to a homomorphism from into F. An application of a good trigger h for to F is a frame where extends W with fresh constants for all and extends R with pairs for all atoms in where

For a set of TGDs by we mean the relational structure, which is the result of the simultaneous application of all good triggers for F for all TGDs in to F. We define as the union or the inverse limit of infinite chain . This version of the chase is similar to the one defined in [15] and is known in the database literature as ‘standard chase’ (in [16]) or as ‘restricted chase’ (in recent papers). In papers on logic, good triggers are sometimes called ‘defects’ and the chase construction is then referred to as ‘defect elimination’.

It should be clear that always satisfies . For a Kripke model , we define as . Those points of that are already in F are called non-anonymous, and those that are not are called anonymous. Anonymous points are often referred to in the database literature as ‘labelled nulls’, but we like to think that Kripke models consist of points. The rank of an anonymous point is the number of the iteration when it was created. The rank of non-anonymous points is 0 by definition.

Proposition 3.

For any SP-implication we have iff .

(⇒) Suppose that . Clearly and also , so there exists a frame such that , . Therefore, this F refutes , showing that is not in .

(⇐) Suppose that . Consider an arbitrary Kripke frame F satisfying , valuation V and its point w such that . Hence there is a homomorphism f from into F sending the root of to w. Now consider (potentially infinite) the step-by-step construction of . Following this process in a step-by-step manner and using the fact that F satisfies at each step, we extend f to a homomorphism h from to F. Since , it follows that . This shows that is in .

2.4. Two-Dimensional Products of Modal Logics

In this paper, we also consider modal formulas with two modalities: and , and their dual modalities: and .

The definition of a normal bimodal logic repeats the definition of normal modal logic except for the axioms () and the Generalization rules (given as infer ) (). The smallest bimodal logic is denoted by . For a set of bimodal formulas and a bimodal logic L, denotes the smallest normal bimodal logic containing .

Definition 1.

For Kripke frames and we define , where

Frame is called the product of and .

Definition 2.

For two normal modal logics, and , we define the product

Definition 3.

Let and be two modal logics with one modality □, then the fusion of these logics is the following bimodal logic:

where is the set of all additional axioms in where each □ is replaced by .

We consider the following formulas

They correspond to the following TGDs:

Definition 4.

For two unimodal logics and we define the commutator of these logics by

Theorem 1

([17]). For logics

3. Two Conditions for TGDs

Consider the following two conditions for a set of TGDs :

- (P1)

- given an sp-term s and a propositional variable p, the valuation in does not contain anonymous points of and

- (P2)

- given an sp-term s, every generated submodel rooted at an anonymous point of contains only anonymous points.

It will be explained later how (P1) and (P2) allow us to lift a homomorphism from into for a simpler (think of and ). What we mean by a ‘simpler ’ will also be clear later. At this point, only note that,

Proposition 4.

Suppose Π is a subset of {Conf, Ser, Refl, Trans}. Then Π satisfies (P1) and (P2).

In fact, (P1) holds for all TGDs without unary predicates in the head. On the other hand, and violate (P2), and so logic with these two axioms will need a special approach.

4. Strictly Positive Fragments of Unimodal Logics with Confluence

In this section, we prove the following two theorems:

Theorem 2.

.

Theorem 3.

For each L in the following set of logics we have (and so they both are axiomatised by with the strictly positive axioms of L due to a general result from [10]).

The proof of Theorem 2 is based on the following two lemmas. The following lemma can be called the completeness of with respect to TGD .

Lemma 1.

Suppose that s and t are sp-terms such that there is a rooted homomorphism h from into . Then is derivable in .

Proof.

First note that in we can derive :

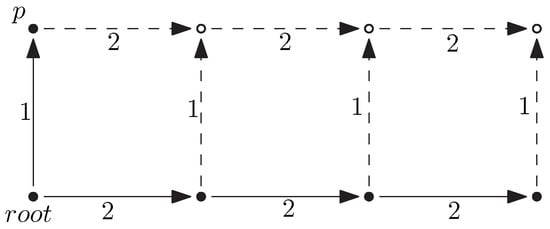

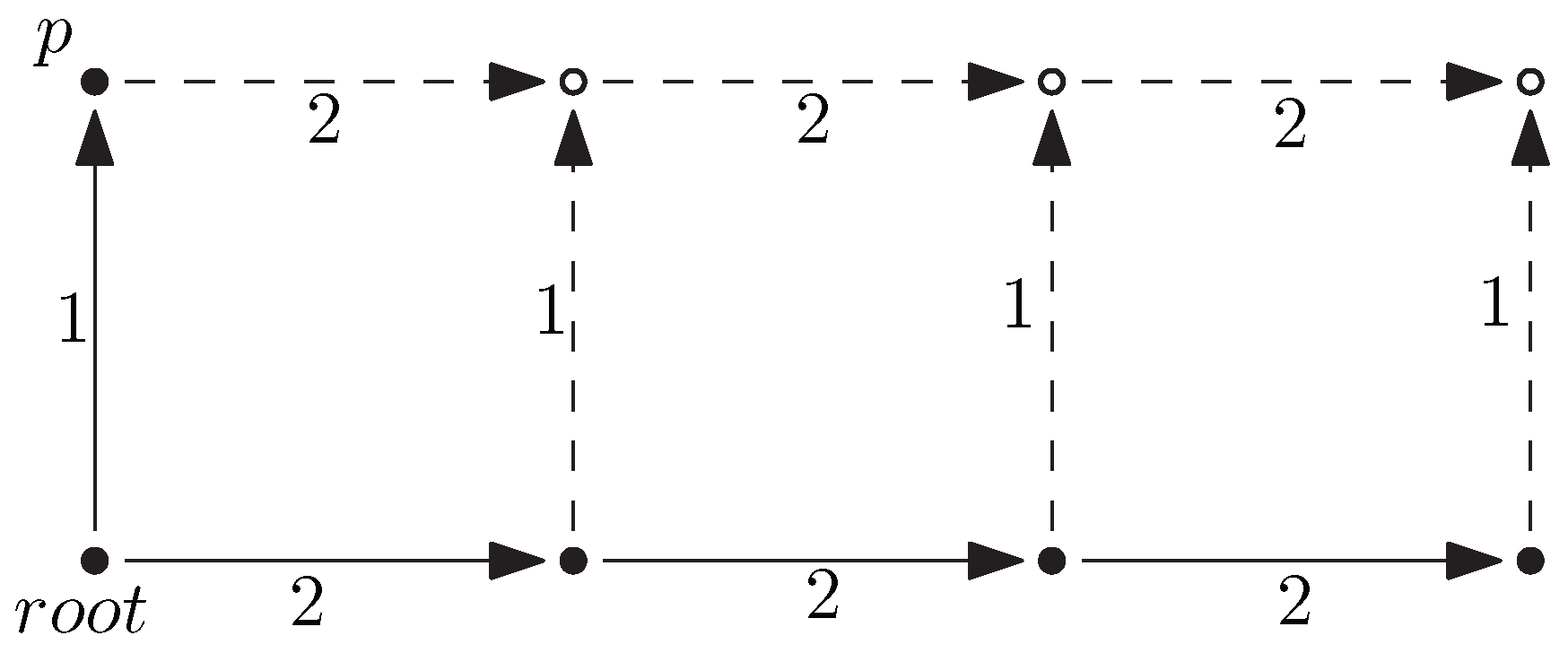

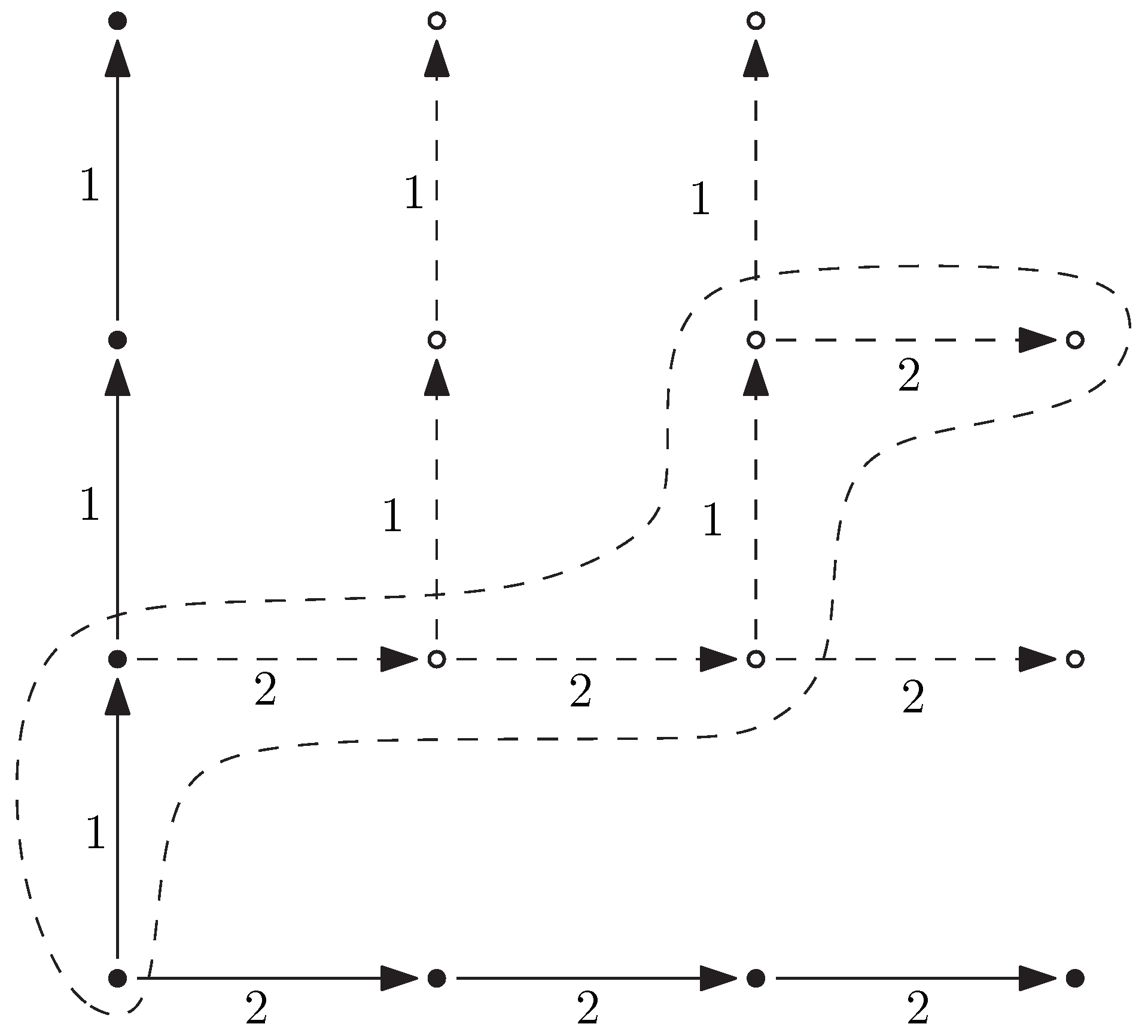

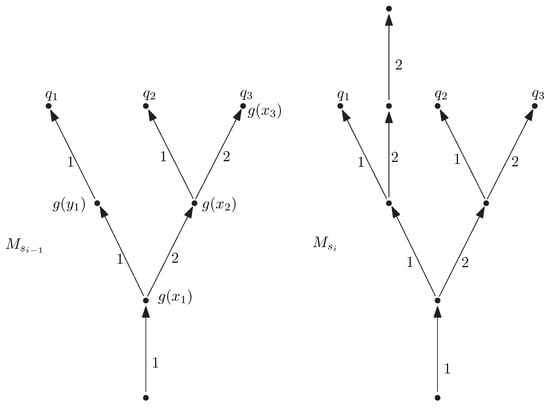

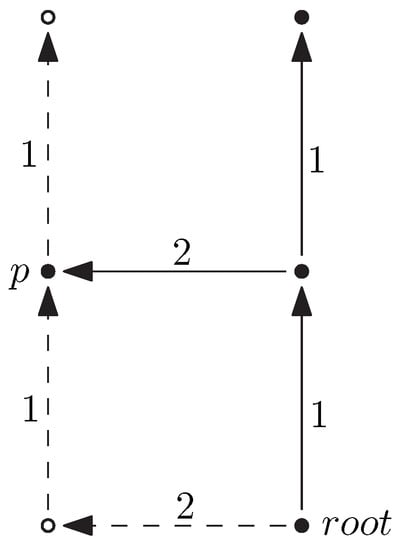

Then note that can be obtained from by a sequence of applications of individual triggers for in such a way that all intermediary models are of the form for some term . (This is due to the fact that applications of preserve the ‘tree-shapedness’ of models.) Thus there exists a sequence of sp-terms such that is the result of the application of trigger g for to for and a rooted homomorphism from into . Now we argue that all implications are derivable in . To derive it is sufficient to take , then substitute the term corresponding to the ‘part of sitting above ’, which is common for and , and then apply rules 3 and (3) of to derive ‘the part of sitting below ’, which is again common for two models, on both sides of the resulting implication (here x and y are variables in the antecedent of ). This argument is illustrated in Figure 1. The implication is derivable by Proposition 2. Now it remains to apply times the first rule of . □

Figure 1.

Suppose that and with , and g as in the figure. Then the term corresponding to the ‘part of sitting above ’ is . Therefore, we substitute in and infer . Then by an admissible in rule (3) from the latter formula and the axiom we infer . Then by rule 3 of we infer and by rule (3) we infer which is .

Lemma 2.

For each frame F we can define a partial function on such that

- its domain contains all non-final points of F and the image of .

- if , then .

Proof.

Each non-final point u of F has a successor v, which gives rise to trigger h for . If this trigger is good, we set to be introduced by an application of this trigger. Otherwise, we set to be , where h is an extension of h to the head of the rule. Then we define on those points of where it has not been defined so far. Then we deal similarly with and so on. □

Proof of Theorem 2.

It should be clear that every theorem of is a strictly positive theorem of since is a theorem of . Therefore, it remains to show that every strictly positive theorem of is a theorem of . Now take a strictly positive implication such that . By Proposition 3, it follows that . Therefore, there exists a rooted homomorphism h from into . If is a singleton, then both and are isomorphic to , and we are done. Otherwise, note that satisfies (P1) and (P2). It follows that . Indeed, we can define a homomorphism from into by recursion. We set for non-anonymous . For anonymous we look at the parent v of u in and set assuming that is already defined. It should be clear that is a homomorphism, since due to (P1) and (P2), no points above an anonymous u in can be in for any p. It remains to apply Lemma 1 to conclude that is derivable in . □

The proof of Theorem 3 is similar. We use TGDs , and and the fact that properties (P1) and (P2) still hold in the setting of L. For example, for , (P1) and (P2) hold for , and this allows us to transform a homomorphism into one using the fact that each point in has a successor. We also use the ‘completeness lemma’ for strictly positive counterparts of to go from the existence of to a derivation of in the corresponding strictly positive logic:

Lemma 3.

Suppose that Φ is a subset of and that Π is the corresponding subset of . Then for any sp-terms s and t, if there is a rooted homomorphism h from into , then the implication is derivable in .

We consider this lemma as folklore (cf. [1,2,5,10]) and leave it without a proof.

5. Strictly Positive Fragments for Logics with Bimodal Version of Confluence

In this section, we consider logic with bimodal versions of confluence . We start by considering this axiom on its own.

We define

and correspond to the TGDs:

The next part of the paper is dedicated to the proof of the following theorem:

Theorem 4.

.

Lemma 4.

All formulas in and are theorems of .

To illustrate the interplay between and , consider the following inference:

This deduction exemplifies the following ‘completeness lemma’ for and :

Lemma 5.

Suppose that s and t are sp-terms. Then if maps homomorphically into the model (with preservation of roots), then the implication is derivable in .

To prove it, we need more verbose modifications of and . We define, by recursion, the terms for and by setting , and for . Now we set and Since one can easily derive in implications and and then use admissible rule (3), we have

Lemma 6.

The formula is derivable in and the formula is derivable in .

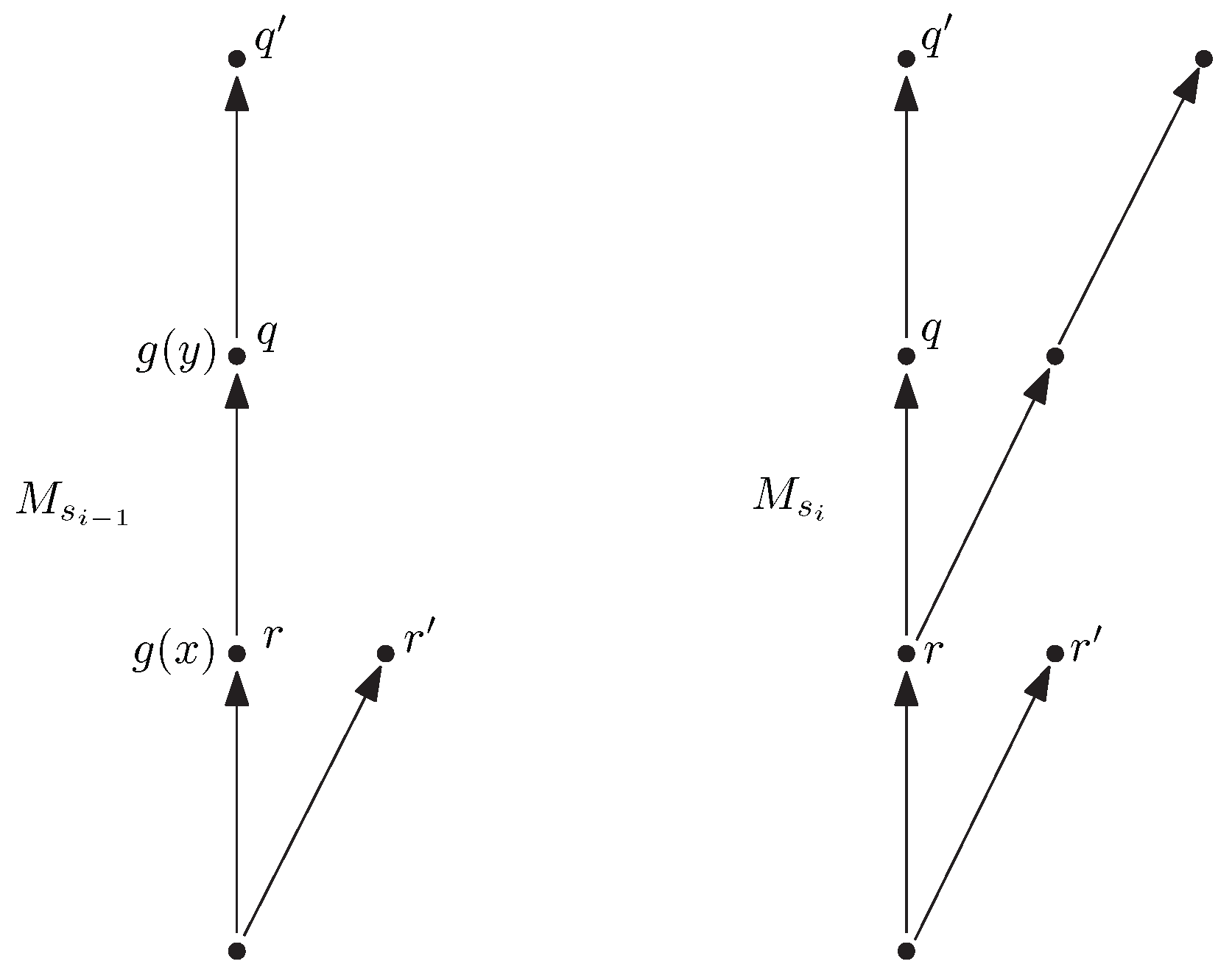

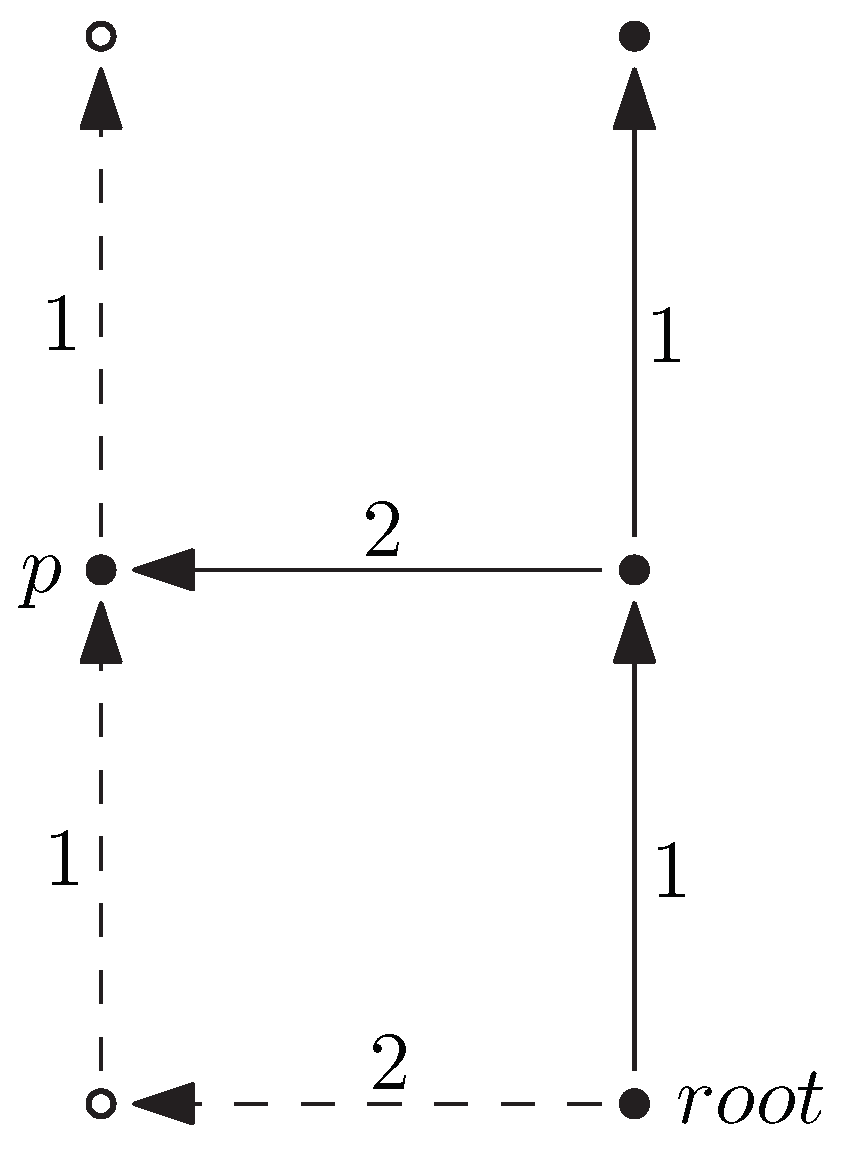

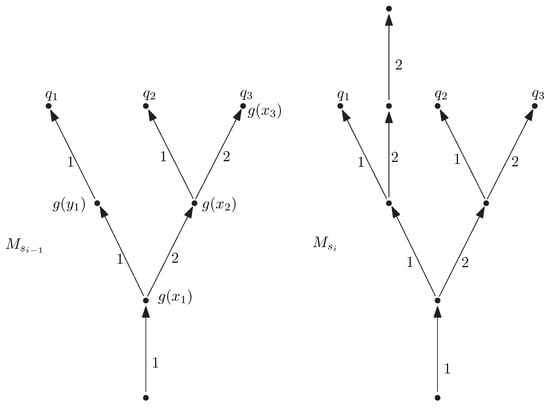

The proof of Lemma 5.

The proof is similar to the proof of Lemma 1. Recall that a chase is a sequence of applications of triggers. Further, note that if a model M is obtained by an application of a trigger for or to a model for an sp-term , then there is an sp-term such that M is isomorphic to . (This is due to the fact that applications of and preserve the ‘tree-shapedness’ of models.) Thus there is a sequence of terms , such that is obtained from by an application of a trigger for or and a homomorphism from into . We argue that implications are deducible in . Indeed, we start with an axiom or expressing the application of a trigger, and then apply substitutions and the rules

for to infer full implication (cf. (2) and (3)). This argument is explained in Figure 3. Additional variables in and serve as substitution slots at object variables and in the body of TGDs. Implication is deducible in by Proposition 2. Now it remains to apply times the rule

□

Figure 3.

Suppose that and with , and trigger g as in the figure. To infer , we take , substitute , , , , obtain and apply .

Let be a frame and . The i-depth of x is the maximum overall lengths of -path starting in x if its finite and ∞ otherwise. Notation: . For example, for a reflexive point x, we have .

Lemma 7.

Let be an arbitrary frame satisfying and . Then for each x and y in W we have

- if , then , and

- if , then .

To see this, note that the statements of Lemma 7 simply rephrase and using the notion of depth.

Given an sp-term t with operators and , a root branch in is a finite sequence of 1 and 2 such that if we define, by recursion, the terms for by setting and for , there is a rooted homomorphism from into . For a term t by we denote the largest number of i’s in any root branch in for . For example, for and .

Lemma 8.

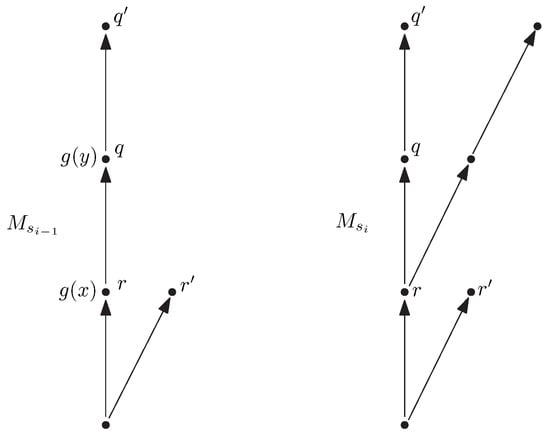

Let be an arbitrary frame satisfying and . Suppose that and t is a variable-free term such that and . Then there is a homomorphism from into F, sending the root of t to x.

Proof.

The proof is by induction on the length of term t. The case when is obvious.

If , then , and there exists y with and

Assuming , we use and deduce that . We apply the IH and conclude that there is a homomorphism from to F, sending the root of to y. This homomorphism can be easily extended to by sending the root of to x.

The case when is similar. If , then IH can be applied to and . The desired homomorphism is the union of homomorphisms from and from . □

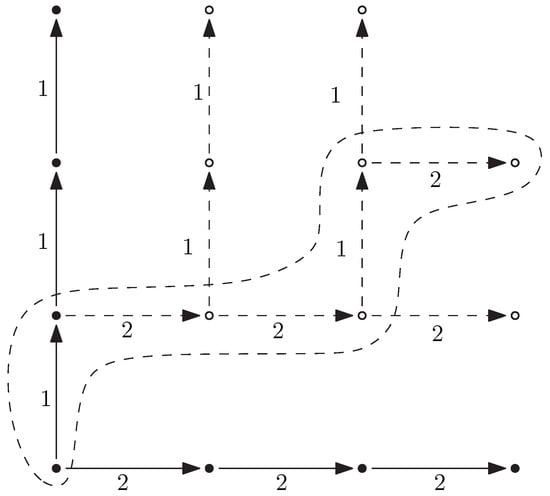

This argument is illustrated in Figure 4 for .

Figure 4.

Proof of Lemma 8 for .

The following lemma says that for any term s, the ‘anonymous part’ of is commutative in the strong following sense.

Lemma 9.

Fix a term s. Suppose that h is a trigger for into such that is an anonymous point of rank . Then there is a point v in of rank such that and . A similar claim holds for .

To see this, focus on the moment when z is created by trigger for and take as v.

Suppose that t is an sp-term and x is a point in such that for all propositional variables p. In this case, by we denote such a term that the submodel of generated by x is isomorphic to .

The proof of Theorem 4.

(⊇) In Lemma 4, we prove that all formulas in and are theorems of .

(⊆) Now take a strictly positive implication such that . By Proposition 3 it follows that . Therefore, there exists a rooted homomorphism h from into . Suppose that holds in , is not anonymous, but is anonymous. By the iterative application of Lemma 9 we obtain that and . Therefore, by Lemma 8, there exists a homomorphism from the subtree of generated at x in the direction of y into , sending x to . In a similar way, we define homomorphisms for pairs of points of such that holds in , is not anonymous, but is anonymous. By applying this argument to all such pairs in , we obtain a homomorphism from into . Again (P1) and (P2) are used to ensure that no points above an anonymous u in can be in for any p. Finally, by Lemma 5, we conclude that is derivable in . □

Now let us turn to the product logic , which, in addition to , contains axioms and . Let us define a set of TGDs

These axioms are already strictly positive and from a general result of [10] (Theorem 35). Therefore, it follows that for . Now we argue that indeed

Theorem 5.

.

Since TGDs create points that do not satisfy (P2), we need a softer condition. Suppose that and . Take an sp-term s and consider . All anonymous points in fall into two groups: introduced by (type 1) and introduced by (type 2). Relying on Lemma 9, we claim that

- (P2’)

- given an sp-term s, every generated submodel rooted at an anonymous point of of type 2 contains only anonymous points of type 2.

Like in Theorem 4, we first establish ‘completeness with respect to TGDs’ for :

Lemma 10.

Suppose that s and t are sp-terms. Then if maps homomorphically into the model (with preservation of roots), then the implication is derivable in .

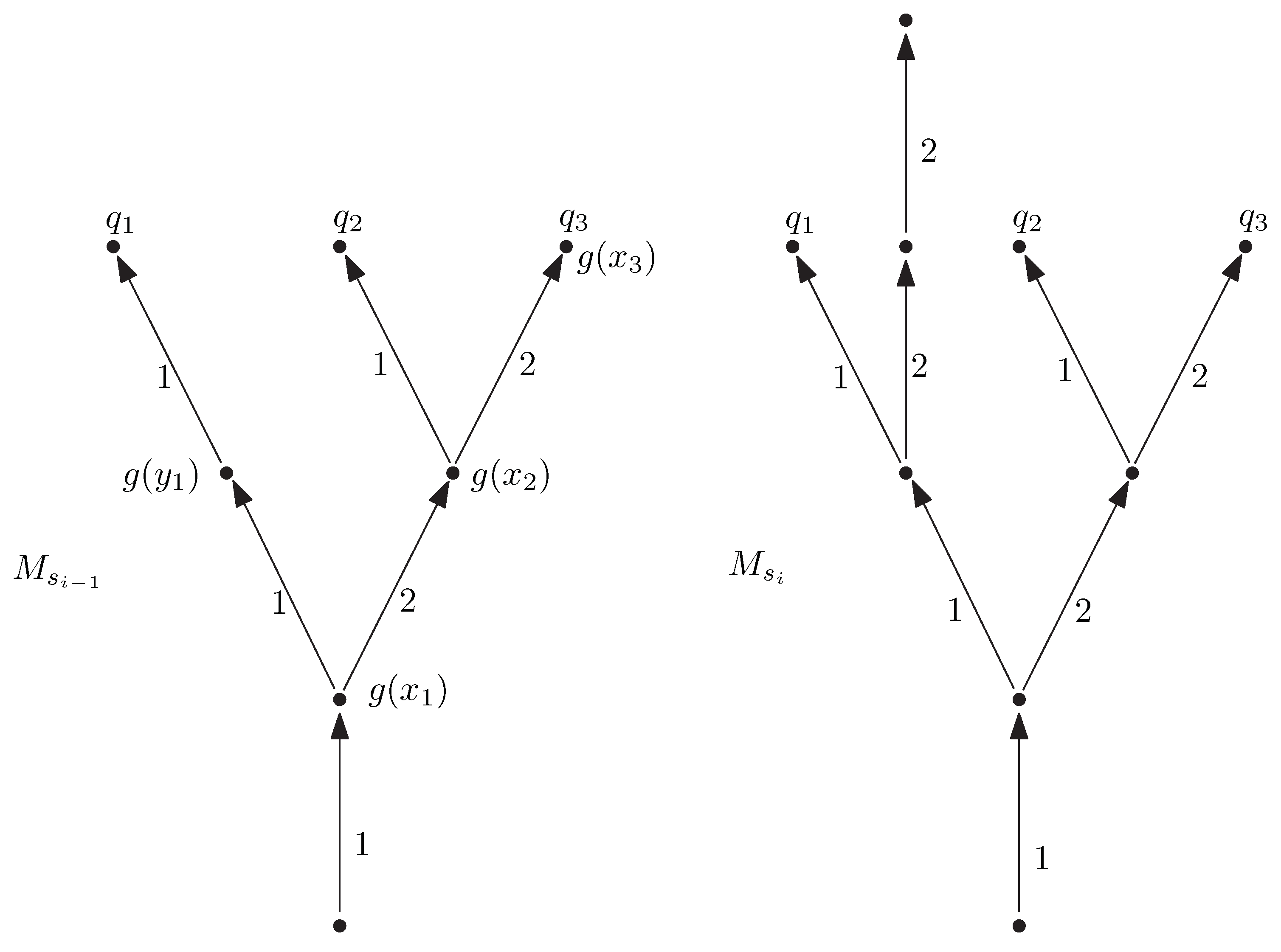

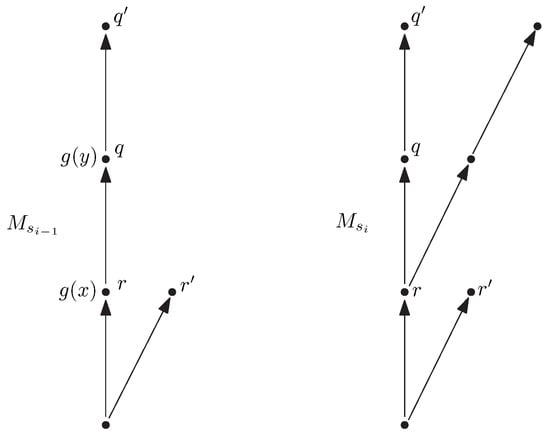

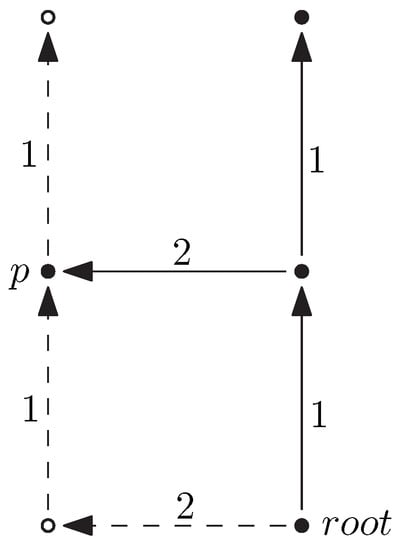

Proof.

Suppose that h is a rooted homomorphism from into . Suppose that is a point of such that is an anonymous point of type 1 in introduced by by trigger g (defined on ). Suppose that is the predecessor of in and are successors of in . Note that this can happen only in case , for , and all are equal. We say that a homomorphism from into is obtained by -surgery of h at if

- is obtained from by changing

- -

- -arrow between and into -arrow

- -

- -arrows between and into -arrows for

- -

- terms ‘sitting’ at in into their conjunction.

- coincides with h on all points except

- (here g is the trigger, and y is a variable of ).

We argue that in this case, the implication is derivable in . Indeed, we take the axiom , apply the substitution , inclusion ‘weakening’ from to , and then we ‘grow’ the common part of h and by the rules

We similarly define -surgeries and argue that by a sequence of surgeries, h may be reduced to a homomorphism from into , which does not use any points of type 1. Thus we can apply Lemma 5 and derive the implication as well as implications between the terms corresponding to the intermediate steps of the surgeries. Finally, we apply the rule a few times

This argument is illustrated in Figure 5. □

Figure 5.

To derive in we first derive and then .

Proof of Theorem 5.

Inclusion from right to left is proved in Lemma 4.

Now, take a strictly positive implication such that . By Proposition 3, it follows that . Therefore, there exists a rooted homomorphism h from into . Now, we argue that there exists a homomorphism from into . Suppose that holds in , is not anonymous, but is anonymous of type 2. By the iterative application of Lemma 9, we obtain that and . Therefore, by Lemma 8 there exists a homomorphism from the subtree of at x in the direction of y into , sending x to . We similarly deal with points x and y such that holds in , is not anonymous, but is anonymous of type 2. By applying this argument to all such pairs of points of , we obtain a homomorphism from into . Finally, by Lemma 10, we conclude that is derivable in . □

Theorem 6.

There is no finite set of formulas Φ such tha .

Proof.

This follows from the fact that in

the formula is not derivable and a standard argument due to Tarski. □

Theorem 7.

For logics

where is the set of all additional axioms in with all ⋄ replaced by .

Proof.

The main remaining ingredient of the proof is ‘completeness of with respect to the corresponding set of TGDS ’ ( because stands for ). It follows from Theorem 35 of [10], Proposition 3, and Kripke completeness of modal counterparts of logics in question. Indeed, if is a rooted homomorphism from into , then by Proposition 3 is derivable in , and by Theorem 35 (see also the text at the beginning of Section 2 of this paper) of [10] any sp-implication in is derivable in .

Now we proceed as before. We assume that s and t are sp-terms such that there is a rooted homomophism h from into . Then using (P2’) for and the fact that there are no final points in , we transform h into a rooted homomorphism from into . Finally, we apply the corresponding ’completeness statement’ to conclude that is derivable in . □

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we develop a technique for axiomatising strictly positive fragments of normal modal logics with confluence axioms and . We apply it to obtain strictly positive axiomatisation for strictly positive fragments of some two-dimensional products of modal logics. Possible directions of future research include axiomatising strictly positive fragments of -dimensional modal logics and strictly positive fragments of restricted fragments of first-order logic that correspond to products of modal logics directly [18] or indirectly [19]. In the context of cylindrical correspondence [18], products of (which are not covered in this paper) are particularly interesting because then modal operators are interpreted as quantifiers, and the confluence axiom turns into the principle , which plays a crucial role in the axiomatisation of these fragments.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, S.K. and A.K.; Writing—review & editing, S.K. and A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewer for careful reading of the paper and helpful comments and questions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jackson, M. Semilattices with closure. Algebra Universalis 2004, 52, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofronie-Stokkermans, V. Locality and subsumption testing in EL and some of its extensions. In Advances in Modal Logic; Areces, C., Goldblatt, R., Eds.; College Publications: London, UK, 2008; Volume 7, pp. 315–339. [Google Scholar]

- Bötcher, A.; Lutz, C.; Wolter, F. Ontology Approximation in Horn Description Logics. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Macao, China, 10–16 August 2019; pp. 1574–1580. [Google Scholar]

- Beklemishev, L. Calibrating provability logic: From modal logic to reflection calculus. In Advances in Modal Logic; Bolander, T., Braüner, T., Ghilardi, S., Moss, L., Eds.; College Publications: London, UK, 2012; Volume 9, pp. 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Dashkov, E. On the positive fragment of the polymodal provability logic GLP. Math. Notes 2012, 91, 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.d.A.; Joosten, J.J. Quantified Reflection Calculus with one modality. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.13651. [Google Scholar]

- Chalki, A.; Koutras, C.D.; Zikos, Y. A quick guided tour to the modal logic S4.2. Log. J. IGPL 2018, 26, 429–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamkins, J.; Löwe, B. The modal logic of forcing. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 2008, 360, 1793–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbay, D.; Kurucz, A.; Wolter, F.; Zakharyaschev, M. Many-Dimensional Modal Logics: Theory and Applications. In Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 148. [Google Scholar]

- Kikot, S.; Kurucz, A.; Tanaka, Y.; Wolter, F.; Zakharyaschev, M. Kripke completeness of strictly positive modal logics over meet-semilattices with operators. J. Symb. Log. 2019, 84, 533–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svyatlovskiy, M. Axiomatization and polynomial solvability of strictly positive fragments of certain modal logics. Math. Notes 2018, 103, 952–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, P.; de Rijke, M.; Venema, Y. Modal Logic; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sofronie-Stokkermans, V. Representation theorems and the semantics of (semi)lattice-based logics. In Proceedings of the 31st IEEE International Symposium on Multiple-Valued Logic (ISMVL 2001), Warsaw, Poland, 22–24 May 2001; pp. 125–136. [Google Scholar]

- Abiteboul, S.; Hull, R.; Vianu, V. Foundations of Databases; Addison-Wesley Reading: Boston, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fagin, R.; Kolaitis, P.G.; Miller, R.J.; Popa, L. Data exchange: Semantics and query answering. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2005, 336, 89–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, A.; Nash, A.; Remmel, J. The chase revisited. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Seventh ACM SIGMOD-SIGACT-SIGART Symposium on Principles of Database Systems (PODS ’08), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–12 June 2008; pp. 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay, D.; Shehtman, V. Products of modal logics. Part I. J. IGPL 1998, 6, 73–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venema, Y. Cylindric modal logic. J. Symb. Log. 1995, 60, 591–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbay, D.M.; Shehtman, V.B. Products of modal logics. Part 2: Relativised quantifiers in classical logic. Log. J. IGPL 2000, 8, 165–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).