Abstract

We investigate a nonparametric, varying coefficient regression approach for modeling and estimating the regression effects caused by two functionally correlated datasets. Due to modern biomedical technology to measure multiple patient features during a time interval or intermittently at several discrete time points to review underlying biological mechanisms, statistical models that do not properly incorporate interventions and their dynamic responses may lead to biased estimates of the intervention effects. We propose a shared parameter change point function-on-function regression model to evaluate the pre- and post-intervention time trends and develop a likelihood-based method for estimating the intervention effects and other parameters. We also propose new methods for estimating and hypothesis testing regression parameters for functional data via reproducing kernel Hilbert space. The estimators of regression parameters are closed-form without computation of the inverse of a large matrix, and hence are less computationally demanding and more applicable. By establishing a representation theorem and a functional central limit theorem, the asymptotic properties of the proposed estimators are obtained, and the corresponding hypothesis tests are proposed. Application and the statistical properties of our method are demonstrated through an immunotherapy clinical trial of advanced myeloma and simulation studies.

Keywords:

functional data; hypothesis testing; regression function; reproducing kernel Hilbert space; sparsely observed data MSC:

62G05; 62G10

1. Introduction

Modern biomedical technology has made it possible to measure multiple patient features during a time interval or intermittently at several discrete time points to review underlying biological mechanisms. Functional data also arise in genetic studies—a massive amount of gene expression data is recorded for each subject and could be treated as a functional curve [1]. Functional data analysis provides distinct features related to the dynamics of cellular responses and activity and other biological processes. Existing methods, such as projection, dimension-reduction, and functional linear regression analysis, are not adapted for such data. Overviews can be found in the book by Horváth and Kokoszka [2] and some recently published papers such as Yuan et al. [3] and Lai et al. [4].

Ramsay and Silverman [5], Clarkson et al. [6], and Ferraty and Vieu [7] introduced some basic tools and widely accepted methods for functional data analysis; Horváth and Kokoszka [2] established some fundamental methods for estimation and hypothesis testing on mean functions and covariance operators of functional data. The topics are broad and the results are in depth. Conventionally, each data curve is assumed to be observed over a dense set of points, often over thousands of points, then smoothing techniques are used to produce continuous curves, and these curves are treated as completely observed functional data for statistical inference. In contrast with those assumptions, we consider the more practical issues in which the data curves are only observed at some (not dense) time points, and the observed data curves are actually interpolations at those observed points. Of course, a relatively large sample size is needed for sparse observations. The effects of both number of observation points and sample size are also considered in our analysis.

For analyzing longitudinal data, Zeger and Diggle [8] considered a semiparametric regression model of the form, with longitudinal observations

where is the response variable, is the covariate vector at time t, is a constant vector of unknown regression coefficients, is an unspecified baseline function, is a zero-mean stochastic process, and represents the observation interval. Under this model, Lin and Ying [9] estimated via a weighted least squares estimator based on the theory of counting processes; Fan and Li [10] further studied this model using a weighted difference-based estimator and a weighted local linear estimator followed by statistical inference, as discussed in Xue and Zhu [11].

For functional data analysis, the data are often represented by , and the model is [12,13,14]

Some researchers considered the following model [2,5,15]

To estimate , assume there are basis and , which span the spaces of the and , respectively. The estimate of of the form is given by

and is estimated by minimizing the residual sum of squares . Although the resulting estimator is useful, a representation theorem for such an estimator is hard to obtain, and hence the asymptotic distribution of this approach is not clear. Yao, et al. [15] investigated a functional principle component method for estimation of model (3) and obtained consistent results. Müller and Yao [16] studied a variation of the above model in the conditional expectation format.

The smoothing spline method is popular for curve estimation. The function curves can be estimated at any point, followed by the computation of coefficients. However, the asymptotic property of estimators based on the spline method is tough to handle. For natural polynomial splines, the number of knots is the number of untied observations, which is sometimes redundant and undesirable. B-splines only require a few (the degree of the polynomial plus two) basis functions and are easy to implement [17,18,19]. Another method is local linear fit [20,21,22], but the difficulty is in choosing the bandwidth, especially when the observation points are uneven. Therefore, in this paper we employ reproducing kernel Hilbert space (RKHS), a special form of spline method in which the turning point from curve estimation to point estimation Yuan and Cai [12] explored its application on functional linear regression problem, and Lei and Zhang [23] extented it to RKHS-based partially functional linear models. In general, one needs to choose a set of (orthogonal) basis functions and the number of basis for functional estimations, while with RKHS one only needs to determine the kernel(s) of RKHS. Furthermore, the Riesz presentation theorem shows that any bounded linear function can be reproduced as a representer based on the RKHS kernel with a closed form.

However, existing RKHS methods often meet obstacles when choosing different norms and the corresponding optimization procedures. Although using a carefully selected norm in the optimization criterion has the advantage of interpretation, it suffers in that the resulting regression estimator generally needs the computation of an inversion of a large matrix (the same as the sample size). Moreover, most of the existing methods, including the aforementioned RKHS methods, are designed for the case where the observed data are sampled from a dense rate and are limited to models in which either the response or predictors are functions. New methods for estimation and hypothesis testing of regression parameters for the more general case where both the response and predictors are functions with sparsely observed data are needed. To address these problems, we propose a new RKHS method with a unified norm to characterize the RKHS and the optimization criterion for function-on-function regression. Although the statistical interpretation of this optimization criterion is not fully clear, with a simple closed form of the estimated regressors under a general function-on-function regression model, this optimization is more computationally reliable and applicable without the need of computing the inverse of a massive matrix. By establishing a representation theorem and a functional central limit theorem based on the proposed model, we obtain the asymptotic distribution of the estimators. Hypothesis testing of the underlying curves is proposed accordingly.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the proposed method for the estimation and hypothesis testing of regression parameters for functional data via the reproducing kernel Hilbert space and establishes some theoretical properties. Simulation studies and a real-data example to demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposed method are given in Section 3 and Section 4, respectively. Section 5 gives some concluding remarks, and all technical proofs are left in the Appendix A.

2. The Proposed Method

We consider the observed data . The underlying data curves are iid copies from , where and are random curves on some region T. The observation times are generally assumed to be different for each subject i for some . We assume that time points () are iid copies from some integer-valued random variable m, and given , the time points for () are iid copies from a positive random variable G, with its support on . For each individual, the observed data can be interpolated as curves on T. We assume the following model for the observed data

where are the true regression coefficient functions for the covariates ’s, and the ’s are random errors. In general, and are non-independent for , e.g., being a zero-mean Gaussian process with some covariance function , known or unknown. Note that model (4) is more general than (2) and is more straightforward than model (3) in describing the relationship between the responses -th and the covariates . Typically, we set , and so is the baseline function. Since and may be different even for the same j, there may be no observation or just a few observations at each time point t.

To estimate the regression coefficient function , the simplest way is the point-wise least squares estimate or any other non-smoothing (i.e., without roughness penalty) functional estimates. However, those estimates have some undesirable properties, often with wiggly shape and large variances in the area with sparse observations. An established performance measure for functional estimation is the mean square error (MSE),

Non-smoothed estimates often have small bias but large sampling variance, while smoothed estimates are the other way around, with much smoother shape by adjusting the shape from neighboring data, but with larger bias. To better balance the trade-off between bias and sampling variance and optimize the MSE, a regularized smooth estimate is preferred, in which a smoothing parameter could control the degree of penalty.

Existing smoothing methods all suffer different aspects of weakness. Functional principal component analysis [15] is computationally intensive. General spline and kernel smoothing methods [24] do not fit the problem under research due to their constant choice of bandwidth. It is known that for non-smoothing methods, computation complexity is often of the order , where n is the data sample size, while for smoothing methods the amount of computation may substantially exceeds and even become computationally prohibitive. Thus, for smoothing methods, it is important to find a method with computation load. To achieve this with spline methods, the basis should have only local support (i.e., nonzero only locally). Recently, a popular method in functional estimation is using the reproducing kernel Hilbert space (RKHS). RKHS is a special spline method that has this property, and can achieve the computation for many functional estimation problems [5,12].

For functional estimate with RKHS, we define two norms (inner products) on the same RKHS : one, denoted by , defines the objective optimization criterion, and another one, denoted by , is for the RKHS . Different from a general Hilbert space, in an RKHS of functions on T, the point evaluation functional is a continuous linear map, so that by the Riesz representation theorem, there is a bi-variate function on T such that

Take , we also get

The above two properties yield the name RKHS.

Note that for a given Hilbert space , a collection of functions on some domain T with a given inner product , its reproducing kernel K may not be unique. In fact, for any mapping , is a reproducing kernel for , and any reproducing kernel of can be expressed in this form (Berlinet and Thomas-Agnan, 2004), and it has a one-to-one correspondence with a covariance function on . The choice of a kernel is mainly for convenience. However, a reproducing kernel under one inner product may not be a reproducing kernel under another inner product on the same space . Assume , with being some RKHS and a known kernel , both are to be specified later. Let be another inner product on (typically and for all ). With the observed curves , ideally an optimization procedure for estimating in (4) will be of the form

where is a penalty functional, and is the smoothing parameter. The penalty term can be significantly simplified via the RKHS as shown in the proof of Theorem 1 below. If , the above procedure gives the unsmoothed estimate with some undesirable properties such as overfitting and large variance.

For model (2) with one covariate variable, Yuan and Cai [12] considered penalized estimate of . The corresponding estimator has a closed form of being linear in , but the computation involves the inverse of an matrix. For model (1) with d covariates, we first consider estimator of in the form of linear in . It turns out that the estimator has a closed form but also involves the inverse of a matrix, which is computationally infeasible in general.

Consider an estimator of in the form of a linear combination of . For any , denote , and for any , denote and similarly for . For matrix and matrix , let be the d rows of , be the d columns of , and define a d-column vector. Since , and , has a basis , we consider estimate of with the form , where is a matrix, is a matrix, and is . With , for fixed an RKHS estimator of is of the form

where

For the penalty, let be a pre-specified symmetric positive definite constant matrix; we define

and

as the null space for the penalty, and is its orthogonal complement (with respect to the inner product ). Then, . That is, ; it has the decomposition , with and . Here, is also an RKHS with some reproducing kernel on . With RKHS, for all , which implies that . Further, for all , and . Thus

Typically, is chosen to be a identity matrix. The choices of , , and the inner product will be addressed latter.

For a function and a vector of functions , denote ; for a matrix , denote , and similarly for the notations and . The following representation theorem shows that the estimator given in (5) is computationally feasible for many applications.

Theorem 1.

Assume , for . Then for the given penalty functional and fixed λ, there are constant matrices and such that given in (5) has the following representation

where , and in vector form of

where the matrices (), (), ), and , and the vectors and are given in the proof.

For the ordinary regression model , with and , the least squares method yields the estimation of as . Since is of order (a.s.), can be viewed as approximately a linear form . Let and . Now we consider estimate of with linear form . Since , and , we only need to consider an estimate of the form , where is a parameter matrix, is a parameter matrix, and is a d-vector. This allows us to express the estimate via the basis of the RKHS and with a greater degree of flexibility than the linear combination of . Another advantage of using estimates of the form is convenience of hypothesis testing. As typically , thus testing the hypothesis of linearity of is equivalent to testing .

For any function , we set , and for fixed ,

where

Let be the vector representation of ; be that of , with , with , , and its vector form , and its vector form ; be all the eigenvalues of D, and be its normalized eigenvectors, and .

Theorem 2.

Assume , for . Then for the given penalty functional and fixed λ, there are constant matrices and such that given in (6) has the following representation

and in vector form of when the following inverse exists,

Below we study asymptotic behavior of given in (6). Denote as the true value of , and is the determinant of a square matrix . Lai et al. [25] proved strong consistency of the least squares estimate under general conditions, while Eicker [26] studied its asymptotic normality. The proposed estimators in this paper have some similarity to the least squares estimate, but they also have some different features and require different conditions.

- (C1).

- .

- (C2).

- .

- (C3).

- for all bounded , where .

- (C4).

- (a.s.).

- (C5).

- .

Theorem 3.

Assume conditions (C1)–(C5) hold, then as ,

To emphasize the dependence on n, we denote . Let be the space of bounded functions on T equipped with the supreme norm, and stands for weak convergence in the space . With the following condition (C6), we obtain the asymptotic normality of

- (C6).

- .

Theorem 4.

Assume conditions (C1)–(C4) and (C6) hold. Then as ,

where is the zero-mean Gaussian process on T with covariance function given in the proof, , and is given in the proof.

Test linearity of .

It is of interest to test the hypothesis is linear in t, where J is a d-dimensional vector with entries 0 or 1, with 1 corresponding to the element of to be tested for linearity. The hypothesis is equivalent to test the corresponding coefficients in be zeros. Let , , , , . Let and be the vector representations of and , and . Denote , . By Theorem 4, we have

Corollary 1.

Assume the conditions of Theorem 4 hold, under , we have

where is the sub-matrix of that corresponds to the covariance of , , and Γ is given in the proof of Theorem 4.

The nonzero bias term in Theorem 4 and Corollary 1 is typical in functional estimation, and often such a bias term is zero for the corresponding Euclidean parameter estimation.

Choice of the smoothing parameter. In nonparametric penalized regression for the model , the most commonly-used method for the choice of the smoothing parameter is cross-validation (CV), based on the ideas of Allen (1974) and Stone (1974). This method chooses by minimizing

where is the estimated regression function without using the observations of the ith individual. This method is usually computationally intensive even when the sample size is moderate. An improved version of the method is K-fold cross-validation. This method first randomly partitions the original sample equally into K subsamples, and then the cross-validation process is conducted K times. At each replicate, subsamples are used as the training data to construct the model, while the remaining one is used as the validation datum. The results from K folds are averaged to obtain a single estimation. In notation, let be the sample sizes of the K folds, then the K-fold cross-validation method is to choose the which minimizes

where is the estimated regression function without using the data in the Jth fold. In this paper, we set , which is also the default setting in much software.

Choices of, , and. For notational simplicity, we consider without loss of generality. Recall that for a function f on with continuous derivatives and , it has the following Taylor expansion [27]

where if and otherwise.

To construct an RKHS on , a common choice for the inner product on is , and the orthogonal complement of is , with inner product , where

The inner product on is . Kernels for the RKHS with more general for and for with these inner products can be found in [28]. More generalized construction of kernels and can be found in Ramsay and Silverman [5]. For our case,

With the above inner product, , and , let , then , , and and are orthogonal to each other with respect to , but these are not true if is replaced by a different inner product on .

3. Simulation Studies

In this section, we conduct two simulation studies to investigate the finite sample performance of the proposed RKHS method. The first simulation study is designed to compare the RKHS estimator with the conventional smoothing spline and local polynomial model methods in terms of curve fitting. For more details on the implementations of smoothing spline and local polynomial model methods, please refer to the book by Fang, Li, and Sudijianto [24]. The second simulation study is to examine the performance of Corollary 1 for testing the linearity of the regression functions. It turns out that with moderate sample sizes, the proposed RKHS estimator performs very favorably with the competitors, and the type I errors and powers of the testing are satisfactory.

Simulation 1. Assume that the underlying individual curve i at time point is generated from

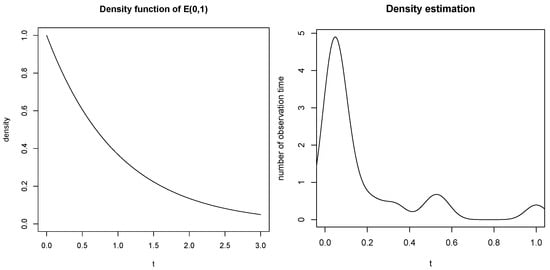

where , and is a stationary Gaussian process with zero mean, unit variance, and a constant covariance between any two distinct time points. For each subject i, the number of observation time points is generated from the discrete uniform distribution on , and the observation time points , are independently generated from the exponential distribution . The density function of is displayed in the left panel of Figure 1, from which it is easy to see that the density value decreases as t increases.

Figure 1.

Left panel visualizes the density function of ; right panel visualizes the kernel density estimation of the number of observation time of MD001.

Then, we use cubic interpolation to interpolate the , , and on T to obtain , , and , respectively.

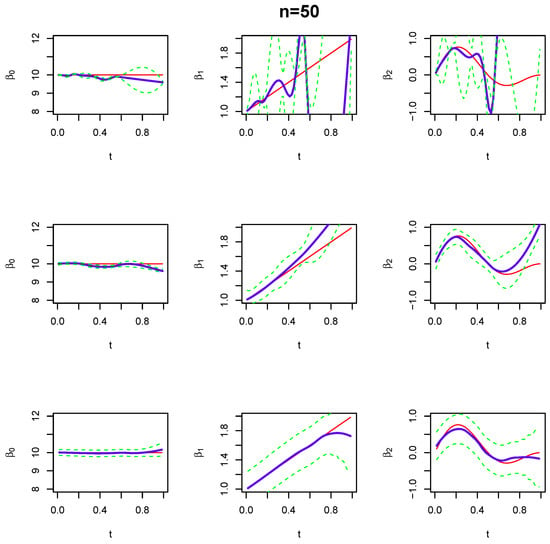

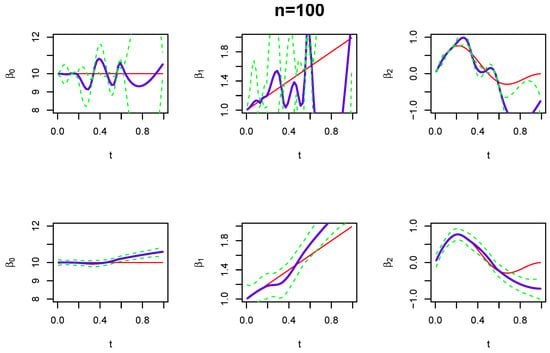

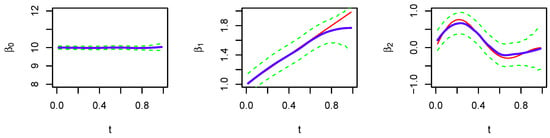

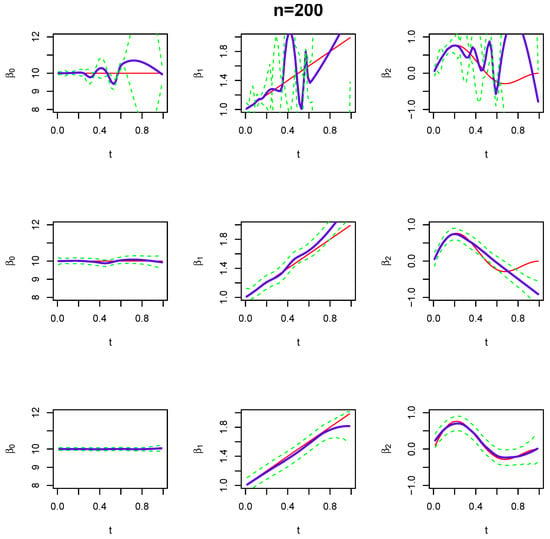

Based on the functions , , and described above, we use the RKHS introduced in Section 2 to estimate the regression functions , and , and compare its performance with the spline smoother and local polynomial models. Typical comparisons (the random seed is set to be “set.seed(1)” in R) are given in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 with sample sizes of 50, 100, and 200, respectively. The simulation shows that the proposed RKHS method estimates the regression functions well and compares very favorably with the other two methods. Broadly speaking, the RKHS estimator has relatively stable performance and is close to the “true” curve; it has narrower confidence bands at dense sampling regions, and they become wider at sparse sampling regions. On the contrary, the spline smoother and local polynomial model appear to have good fit at dense sampling regions, but they have large bias when the data become sparse.

Figure 2.

Performance of curve estimation when the sample size is 50 and the random seed is “set.seed(1)” in R. First row: curve estimation performance of the spline smoother; Second row: curve estimation performance of the local polynomial model; Third row: curve estimation performance of the proposed RKHS method. Solid red line: true curve; Solid blue line: estimated curve; Dotted lower and upper green lines: confidence bands.

Figure 3.

Performance of curve estimation when the sample size is 100 and the random seed is “set.seed(1)” in R. First row: curve estimation performance of the spline smoother; Second row: curve estimation performance of the local polynomial model; Third row: curve estimation performance of the proposed RKHS method. Solid red line: true curve; Solid blue line: estimated curve; Dotted lower and upper green lines: confidence bands.

Figure 4.

Performance of curve estimation when the sample size is 200 and the random seed is “set.seed(1)” in R. First row: curve estimation performance of the spline smoother; Second row: curve estimation performance of the local polynomial model; Third row: curve estimation performance of the proposed RKHS method. Solid red line: true curve; Solid blue line: estimated curve; Dotted lower and upper green lines: confidence bands.

In order to make a thorough comparison for this simulation, we use the root integrated mean squared prediction error (RIMSPE) to measure the accuracy of the estimates [24]. The RIMSPE for estimate of is given by

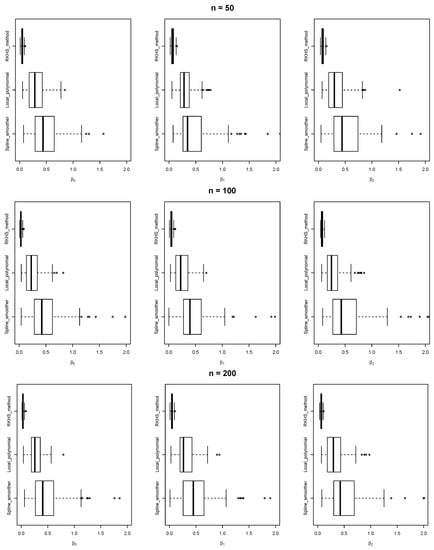

and the simulation is repeated 1000 times. By using the R software, the CPU time of implementing this simulation is about 84.5 s on a PC with a 1.80 GHz dual-core Intel i5-8265U CPU and 8 GB memory. The boxplots of the RIMSPE values are presented in Figure 5, from which it is clear that RKHS performs much better than the other two methods, because it has much smaller RIMSPE values.

Figure 5.

Boxplots of the RIMSPE values. The first row corresponds to sample size 50, the second row corresponds to sample size 100, and the third row corresponds to sample size 200. In each row, the left panel is for estimating , the middle panel is for estimating , and the right panel is for estimating .

Simulation 2. In this simulation study, we examine the performance of Corollary 1 for testing the hypothesis

According to the setting described in Simulation 1, is linear in t, whereas is apparently not linear in t. Therefore, we will check the type I error for testing and the power for testing . By setting the significance level to and repeating the simulation 1000 times, we use Corollary 1 to derive testing statistics and list its type I errors and powers in Table 1 for various sample sizes. The results in Table 1 suggest that the type I error of the test is close to the nominal level , and the power of the test is not small even with a sample size of 50.

Table 1.

Summary of simulation results for linearity testing.

4. Real Data Analysis

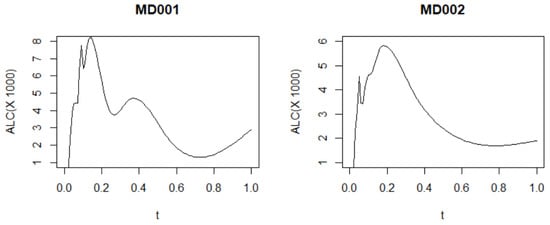

In this section, the proposed method is applied to characterize the relationships in patient immune response in a clinical trial of combination immunotherapy for advanced myeloma. The objective of the original trial was to study whether introducing vaccine-primed T cells early leads to cellular immune responses to the putative tumor antigen hTERT. In this study, 54 patients were recruited and assigned to two treatment arms based on their leukocyte response to human leukocyte antigen A2. Various immune cell parameters (CD3, CD4, CD8), T-cell levels, cytokines (IL7, IL-15), and immunoglobulins (IgA, IgG, IgM) were measured repeatedly to investigate the treatment effect on immune recovery and function. The measurements were taken at nine time points: 0, 2, 7, 14, 40, 60, 90, 100, and 180 days [29]. Moreover, as a subtype of white blood cells in the human immune system, absolute lymphocyte cell (ALC) count was recorded over time during or after patients’ hospitalization up to day 180. Figure 6 shows the trajectories of two individuals, namely “MD001” and “MD002”, in the dataset, with the observation interval scaled to . The trajectories of all 54 individuals can be found in the paper by Fang et al. [30]. Previous research has shown that the patient’s survival time is associated with the trajectory of the patient’s ALC counts.

Figure 6.

Left panel: trajectory of individual “MD001"; right panel: trajectory of individual “MD002". The observation interval has been scaled to .

In the human immune system, the relationships among various biological features are too complicated and have been topologically described only. For illustrating the performance of our proposed methods with a limited sample size, we only investigate how the levels of a patient’s immunoglobulin IgG and immune cell CD8 dynamically affect the trajectory of the patient’s ALC counts in this section. For simplicity, the observation time points are scaled to the interval . Let and be the trajectories of the patient’s IgG, CD8, and ALC counts, respectively. Their relationship can then be described as follows

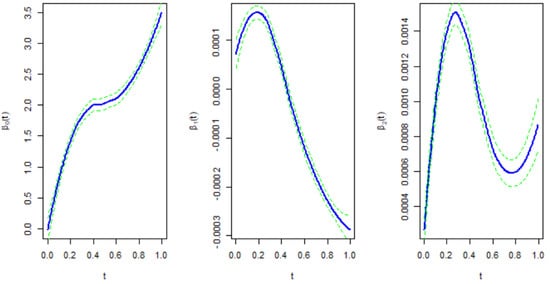

where and are the regression coefficient functions, and is the random error function. The purpose of this study is to estimate the regression coefficient functions and test whether and are linear functions in t.

In the used data, the number of observation times generally becomes sparse as t increases. The right panel of Figure 7 visualizes the kernel density estimation of individual “MD001” in the data. The distribution of observed time points reveals the trend. The proposed RKHS method is used to estimate the regression coefficient functions and test the linearity. By using the R software, the CPU time of implementing the estimation procedure is only about 1.5 s on a PC with a 1.80 GHz dual-core Intel i5-8265U CPU and 8 GB memory. Figure 7 visualizes the estimated curves and their confidence bands. It is observed that and are apparently nonlinear in t. This observation is also confirmed by the statistic derived from Corollary 1, which yields p-values less than for both and . It is worth noting that is monotone in t, but and are not monotone in t. The results show that with the immunotherapy of tumor antigen vaccination, a patient’s immunoglobulin IgG enhances the ALC counts. When the increasing CD8 immune cells result in a high ALC count, immunoglobulin IgG inhibits the patient’s ALC counts such that the level of ALC counts is reconverted into the normal interval , and this immunotherapy can potentially improve patient survival time.

Figure 7.

The regression coefficient functions estimated by the proposed RKHS method. Solid blue line: estimated curve; dotted lower and upper green lines: confidence bands. The time t has been scaled to the interval .

5. Concluding Remarks

The existing work on functional data analysis has focused primarily on the case where the observed data are sampled from a dense rate and has been limited to models in which either the response or predictors are functions. In this paper, we consider the more practical situation for functional data analysis where the data are only observed at some (not dense) time points, and we propose a general regression model in which both the response and predictors are functions. This function-on-function regression model, as given by Equation (4), can be viewed as a generalization of multivariate multiple linear regression to allow the response, predictors, and even the regression coefficients to be all functions of t. In order to estimate the underlying regression curves and conduct hypothesis testing on these curves, we use reproducing kernel Hilbert space (RKHS), which only needs to choose the kernel(s) of the RKHS, and enables a closed-form solution for the regression coefficients in terms of the kernel. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first representation of functional regression coefficients with sparsely observed data. Furthermore, the estimator based on RKHS provides a foundation for hypothesis testing, and the asymptotic distribution of the estimator is obtained. Simulation studies show that the RKHS estimator has relatively stable performance. Application and statistical properties of our method are further demonstrated through an immunotherapy clinical trial of advanced myeloma. By using the proposed function-on-function regression model and related theorems established in this paper, this real application showed that with the immunotherapy of tumor antigen vaccination, patient immunoglobulin IgG enhances ALC counts, and hence this immunotherapy can potentially improve patient survival time. Future work may consider experimental design for the time points to be observed. If the time points can be controlled by the experimenter, their careful selection would improve the efficiency of the estimator (e.g., reduce the bias or MES). Further, we hope to study function-on-function generalized linear regressions with sparse estimation coefficient functions by the penalized method of Zhang and Jia [31].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.-B.F.; methodology, H.H.; validation, G.M.; formal analysis, H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.H.; writing—H.-B.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) grant P30CA 051008 and the Key Laboratory of Mathematical and Statistical Models (Guangxi Normal University), Education Department of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data included in this study are available upon request by contacting the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Proof of Theorem 1 (1-dimensional case).

thus

From this we get

where, . Note , or

Further, , or

where, by convention, , a n-dimensional row vector.

or

It is easy to check that , (), , , , , , and , . Denote , and , ), then the above system of equations can be rewritten as

or when the following inverse exists,

In this case, , , , , , , and

Below we evaluate . As

Rewrite (2) as

where . must satisfy

□

Proof of Theorem 2 (one-dimensional case).

It is easy to check that , (); , ; ; ; and . Denote , , and , the above system of equations is rewritten as

or when the following inverse exists,

In this case, , , , , , and

As in the proof of Theorem 1 (one-dimensional case), must satisfy

or

□

Proof of Theorem 1.

where . Note , or

Further, , and , or

where, by convention, is the matrix with -th entry .

For any two matrices and of the same dimension, denote . Let . It it not difficult to check that

We first simplify the penalty term . By property of RKHS, , thus , and , . Thus

Note that the inner product of the RKHS is often not the inner product used in the optimization objective, such as the one corresponding to the norm. Thus, the above expression of does not hold under the inner product .

Below we need to evaluate . For this, write for the i-th row of , and for the i-th column of . Then

and we get, since , and ,

From this we get

Rewrite (2) as

where . must satisfy

To solve the linear system (A3), we need to rewrite it in terms of vector forms and of and . For this, let be the vector representation of ; be that of . For , is a matrix with -th entry . Similarly, is a matrix with -th entry ; is a matrix with -th entry ; and is a matrix with -th entry .

Likewise, is a matrix with -th entry ; is a matrix with -th entry ; and is a matrix with -th entry .

Let the notation means rearrange elements in the matrix as a -vector in dictionary order in terms of its -vector form. Thus,

where ; Similarly,

where ; and

where .

Likewise,

and

where .

Rewrite as

Let , be the matrix of 1’s, , and

Then (A1) is rewritten as

or when the following inverse exists,

□

Proof of Theorem 2.

we get, since ,

where is the i-th row of D. From this we get

or

or

Let be the solution of (A5).

In this case, is a d-vector and, similar to the proof of Theorem 1, we have . To evaluate , write , where is the j-th column of . Then , and

Now (3) is rewritten as

where , and must satisfy

To solve the linear system (A5), we need to rewrite it in terms of vector forms and of and . For this, let be the vector representation of ; let be that of .

Let the notation mean rearranging the elements in the matrix in terms of its vetor form. As in the proof of Theorem 1,

where

Similarly,

where ;

and

Denote and its vector form ; let and its vector form ; since D is semipositive definite, let be its eigenvalues, and be its normalized eigenvectors, , then . Rearranging elements of in vector form similarly as before

where .

Then (A5) is rewritten as

or when the following inverse exists,

□

Proof of Theorem 3.

Note that

Note that (C3) implies and , so by Theorem 7.9 (or Corollary 7.10) in Ledoux and Talagrand [32], (a.s.), where . By (C4), (a.s.). Thus, (a.s.).

Let , , , , is the empirical distribution based on n iid samples from . Let

By (C5) and (C4) and the fact (a.s.),

In the above we used Theorem 7.9 (or Corollary 7.10) in Ledoux and Talagrand [32] again to get (a.s.).

Note that implies , this together with (C3) implies that has an unique (and finite) minimizer . We first prove (a.s.).

By definition of , (a.s.), and by (A7), (a.s.). Thus,

where is some bounded set of ’s, and we used the fact that is a Glivenko–Cantelli class on any bounded . Thus (a.s.).

On the other hand, since is the unique minimizer of , for every , there is , such that

Thus, by (A8) we must have that for all large n, (a.s.) for every . This gives (a.s.).

Note that , which is the minimizer of the conditional expectation , and is also the pointwise least squares “estimate" of itself under the objective functional , so by (C1), , (C2) implies is invertible, and so can be written in the form . Since also minimizes (over a larger space than that belongs to), we must have , and (a.s.) gives (a.s.). □

Proof of Theorem 4.

Recall the blockwise inversion formula

and for , .

By (C2) and (C3), for all large n, , , , and all exist (a.s.). Using the above blockwise inversion formulae, by Theorem 2, we get

In the proof of Theorem 3, we showed (a.s.), i.e., (a.s.). Further, similar to the proof of Theorem 3, we can get

Let and be the vector representations of and , then we have

Denote and , we first find the asymptotic distribution of . Denote , , and , then , and . By (C6),

It can be shown that the sequences and are Donsker classes, and so

where , is the vector form of and is the vector form of . From the above we get, as is symmetric,

Now, rewrite , with , and , where , and . Then , and by (A9) we get

where is a mean zero Gaussian process on T with covariance function . □

References

- Ullah, S.; Finch, C.F. Applications of functional data analysis: A systematic review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horváth, L.; Kokoszka, P. Inference for Functional Data with Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, A.; Fang, H.B.; Li, H.; Wu, C.O.; Tan, M. Hypothesis Testing for Multiple Mean and Correlation Curves with Functional Data. Stat. Sin. 2020, 30, 1095–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, T.Y.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Wang, Y.F. Testing Independence and Goodness-of-Fit Jointly for Functional Linear Models. J. Korean Statsitical Soc. 2021, 50, 380–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, J.O.; Silverman, B.W. Functional Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, D.B.; Fraley, C.; Gu, C.; Ramsay, J.O. S+ Functional Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraty, F.; Vieu, P. Nonparametric Fuctional Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zeger, S.L.; Diggle, P.J. Semiparametric Models for Longitudinal Data with Application to CD4 Cell Numbers in HIV Seroconverters. Biometrics 1994, 50, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.Y.; Ying, Z. Semiparametric and Nonparametric Regression Analysis of Longitudinal Data. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2001, 96, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Li, R. New Estimation and Model Selection Procedures for Semiparametric Modeling in Longitudinal Data Analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2004, 99, 710–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xue, L.; Zhu, L. Empirical Likelihood Semiparametric Regression Analysis for Longitudinal Data. Biometrika 2007, 94, 921–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Cai, T. A Reproducing Kernel Hilbert Space Approach to Functional Linear Regression. Ann. Stat. 2010, 38, 3412–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, P.T.; Goldsmith, J.; Shang, H.L.; Ogden, R.T. Methods for Scalar-on-Function Regression. Inte. Stat. Rev. 2017, 85, 228–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Guo, S.J.; Qian, X.H. Functional Linear Regression: Dependence and Error Contamination. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2022, 40, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.; Müller, H.G.; Wang, J.L. Functional Linear Regression Analysis for Longitudinal Data. Ann. Stat. 2005, 33, 2873–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Müller, H.G.; Yao, F. Functional Additive Models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2008, 103, 1534–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, N.; Boulesteix, A.L.; Tutz, G. Penalized Partial Least Squares with Applications to B-spline Transformations and Functional Data. Chem. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2008, 94, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayashi, K.; Hayashi, M.; Reich, B.; Lee, S.P.; Sachdeva, A.U.C.; Mizoguchi, I. Functional Data Analysis of Mandibular Movement Using Third-degree B-Spline Basis Functions and Self-modeling Regression. Orthod. Waves 2012, 71, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, A.M.; Aguilera-Morillo, M.C. Penalized PCA Approaches for B-spline Expansions of Smooth Functional Data. Appl. Math. Comput. 2013, 219, 7805–7819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlinet, A.; Elamine, A.; Mas, A. Local Linear Regression for Functional Data. Ann. Inst. Stat. Math. 2011, 63, 1047–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abeidallah, M.; Mechab, B.; Merouan, T. Local Linear Estimate of the Point at High Risk: Spatial Functional Data Case. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 2020, 49, 2561–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sara, L. Nonparametric Local Linear Regression Estimation for Censored Data and Functional Regressors. J. Korean Stat. Soc. 2020, 51, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Zhang, H. Non-asymptotic Optimal Prediction Error for RKHS-based Partially Functional Linear Models. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.04729. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, K.T.; Li, R.; Sudjianto, A. Design and Modeling for Computer Experiments; Chapman & Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, T.L.; Robins, H.; Wei, C.Z. Strong Consistency of Least Squares Estimates in Multiple Regression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1978, 75, 3034–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eicker, F. Asymptotic Normality and Consistency of the Least Squares Estimators for Families of Linear Regressions. Ann. Math. Stat. 1963, 34, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahba, G. Spline Models for Observational Data; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, C. Smoothing Spline ANOVA Models; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, A.P.; Aqui, N.A.; Stadtmauer, E.A.; Vogl, D.T.; Fang, H.B.; Cai, L.; Janofsky, S.; Chew, A.; Storek, J.; Gorgun, A.; et al. Combination immunotherapy using adoptive T-cell transfer and tumor antigen vaccination based on hTERT and survivin after ASCT for myeloma. Blood 2011, 117, 788–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fang, H.B.; Wu, T.T.; Rapoport, A.P.; Tan, M. Survival Analysis with Functional Covariates Based on Partial Follow-up Studies. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2016, 25, 2405–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jia, J. Elastic-net Regularized High-dimensional Negative Binomial Regression: Consistency and Weak Signals Detection. Stat. Sin. 2022, 32, 181–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledoux, M.; Talagrand, M. Probability in Banach Spaces; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).