Abstract

This paper reports the construction of synchronization criteria for the delayed impulsive epidemic models with reaction–diffusion under the Neumann boundary value. Different from the previous literature, the reaction–diffusion epidemic model with a delayed impulse brings mathematical difficulties to this paper. In fact, due to the existence of second-order partial derivatives in the reaction–diffusion model with a delayed impulse, the methods of first-order ordinary differential equations from the previous literature cannot be effectively applied in this paper. However, with the help of the variational method and an appropriate boundedness assumption, a new synchronization criterion is derived, and its effectiveness is illustrated by numerical examples.

Keywords:

Neumann boundary value; delayed impulse; synchronization; reaction–diffusion epidemic models; variational methods MSC:

34K24; 34K45

1. Introduction

The dynamics of epidemic models has always been a hot topic [1,2]. Ordinary differential equation epidemic dynamic models are the most common models, and fractional order models especially have been hot topics in recent research [3,4,5,6] whose ideas or methods have been applied to studying epidemic dynamic models. Moreover, the reaction–diffusion epidemic models have become one of the key topics because of the migration behavior of the population [7,8,9,10]. Usually, infectious diseases are controlled within a certain range, so we consider the Neumann boundary value, that is, there is no diffusion on the boundary of the infectious area because the disease area is usually isolated from the outside world by some measures, so the Neumann zero boundary value is considered in this paper. To prevent the spread of disease, the government or relevant departments often take impulse measures. This impulse management measure is not only aimed at the epidemic situation, but also considered impulse control measures for economic management, mechanical engineering and other issues [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Delayed impulse models have also been investigated by many researchers [11,12], for delayed impulse models better simulate the actual situation, that is, the impulse effect usually takes some time to appear. However, the models with a delayed impulse are usually ordinary differential systems, and reaction–diffusion systems with a delayed impulse are rarely seen in the existing literature. This inspired us to write this paper. In fact, due to the existence of second-order partial derivatives in the reaction–diffusion model with a delayed impulse, the methods of first-order ordinary differential equations in the existing literature cannot be effectively applied to partial differential equations. By means of the variational method, differential mean value theorem and convergence of sequence, the synchronization criterion of the delayed impulse reaction–diffusion epidemic model is obtained in this paper. Intuition tells us that the shorter the impulse interval, the greater the impulse frequency and the faster the impulse effect appears, and the greater the impulse intensity, the faster the synchronization between the models must be. These intuitive conclusions are affirmed in the synchronization criterion given in this paper.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we present some preliminaries about the reaction–diffusion epidemic model with a delayed impulse. In Section 3, we propose and derive the synchronization criterion for reaction–diffusion epidemic models under a delayed impulse. In Section 4, an illustrative numerical example is provided to show the effectiveness of the newly obtained criterion. Finally, some conclusions are written in Section 5.

The main contributions are as follows:

- Proposing and studying reaction–diffusion epidemic models with a delayed impulse for the first time;

- Deriving for the first time the synchronization criterion of an epidemic system with a Neumann boundary value under a delayed impulse.

2. System Description and Preliminaries

In [1], the following epidemic system was studied:

where the function is the fraction of the susceptible population, the infected fraction, the recovered fraction, and . In addition, the disease transmission rate is denoted by and the recovery rate is . In 2020, the authors of [7] considered the epidemic system with inevitable diffusions:

where is the Laplacian operator.

Generally speaking, for .

Denote with The following impulsive epidemic model with a Neumann boundary value is investigated in this paper:

where and is the impulse moment for satisfying and For any impulse moment is a constant parameters matrix that quantifies the impulse strength at the moment The time delay with for each , , and so is a bounded smooth domain with smooth boundary

Denote the external normal direction of .

System (3) is the drive system, and its response system can be considered as follows,

and then the error system is proposed as follows,

where . Moreover,

We assume in this paper that variables are left continuous at impulse moment , for example,

Obviously, . Moreover, in consideration of the fact that population resources are limited, we can assume throughout this paper that their regional change rate is also limited, and so the change rate of the change rate is even limited:

- H1

- For any , there exists a constant such that

- H2

- There is a constant such that ;

- H3

- There is a constant such that .

Lemma 1.

(See, e.g., [21]). is a bounded domain with its smooth boundary that is of class . is a real-valued function and . Then,

where is defined by the least positive eigenvalue of the problem:

3. Main Result

Theorem 1.

Assume there exists a positive definite diagonal matrix Q and a constant such that

and

then system (3) and system (5) are synchronized, where is the identity matrix, with defined in (H1), ,

Here, inequality (8) indicates that is a non-negative definite matrix. For any symmetric matrix B, the real numbers and represent the minimum and maximum eigenvalue of B, respectively. For a matrix B, is its norm with .

Proof.

Consider the following Lyapunov function:

where Q is a positive definite symmetric matrix. Denote for any vector Lebesgue square-integrable function

It follows from and that

So,

which means

Particularly,

On the other hand,

and

Now we can see it from the differential mean value theorem and definition of that there exists such that

which means

Finally, for

which, together with , implies

where . This completes the proof. □

Remark 1.

Contrary to the existing literature related to impulsive reaction–diffusion epidemic models (see, e.g., [13,14]), the delayed impulse is firstly considered in the reaction–diffusion epidemic system in this paper. Indeed, although time delays were introduced in [13], the impulse was not delayed. However, in real life, the effectiveness of many defensive measures usually takes place after a period of time. Therefore, the delayed impulse epidemic model studied in this paper clearly has practical significance.

Remark 2.

Introducing the delayed impulse into reaction–diffusion epidemic models means bringing new mathematical difficulties to this paper. Therefore, this paper adopts a method different from [13,14] to overcome the mathematical difficulties, and a new synchronization criterion is derived.

4. Numerical Example

Example 1.

Let , then Set , , and

Case 1: Let , , and

Using a computer with Matlab’s LMI toolbox results in the following feasibility datum:

then, , and

where According to Theorem 1, system (3) and system (5) are synchronized.

Case 2: Let , , and

Using Matlab’s LMI toolbox results in the following feasibility datum:

then, , and

where According to Theorem 1, system (3) and system (5) are synchronized.

Remark 3.

Table 1 reveals that the bigger the impulse frequency, the faster the synchronization speed.

Table 1.

Comparison of the influence from different impulse frequencies when other data are unchanged.

Case 3: Let , , and

Using Matlab’s LMI toolbox results in the following feasibility datum:

then, , and

where According to Theorem 1, system (3) and system (5) are synchronized.

Remark 4.

Table 2 implies that the bigger the impulse intensity, the faster the synchronization speed.

Table 2.

Comparison of the influence from different impulse intensities when other data are unchanged.

Case 4: Let , , and

Using Matlab’s LMI toolbox results in the following feasibility datum:

then, , and

where According to Theorem 1, system (3) and system (5) are synchronized.

Remark 5.

Table 3 means that the smaller the time delays of the impulse effect, the faster the synchronization speed.

Table 3.

Comparison of the influence of different time delays of the impulse effect when other data are unchanged.

Below, another numerical example is presented to show the validity of Theorem 1 via very simple computations.

Example 2.

Set , , , , , and then direct computations lead to

Let ; then, Set ; then,

Hence, it follows from (14) and (15) that

where

Now, letting and , we can get by (14)–(16) that

which implies (9) holds.

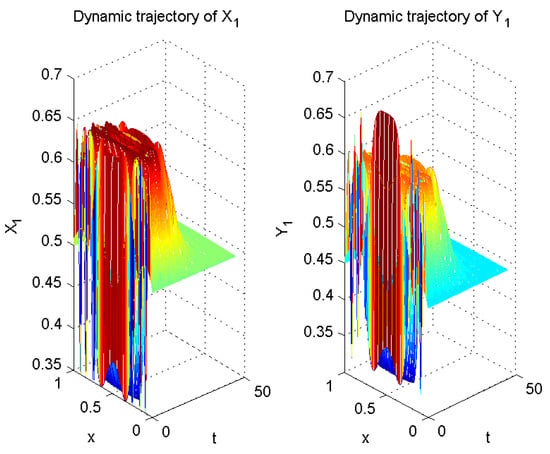

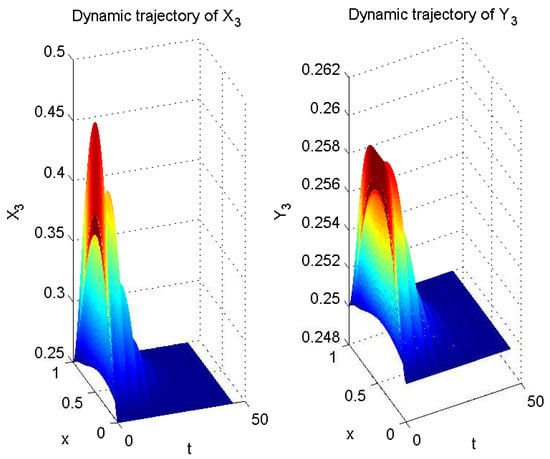

According to Theorem 1, system (3) and system (5) are synchronized (see Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Computer simulation of in (3) and in (5).

Figure 2.

Computer simulation of in (3) and in (5).

Figure 3.

Computer simulation of in (3) and in (5).

Remark 6.

Example 2 illustrates that the validity of Theorem 1 can be easily verified even without using Matlab’s LMI toolbox.

5. Conclusions

This paper reported the synchronization control of two epidemic systems with a Neumann boundary value under a delayed impulse. Different from the previous relevant literature in which the effect of the impulse control was immediate, our impulse effect was delayed, which is in line with the actual situation during an epidemic. At the same time, the newly obtained criterion and numerical examples illustrate that the shorter the time delay of the pulse effect, the faster the synchronization speed. In addition, the smaller the pulse interval, the faster the synchronization. On the other hand, Remarks 1 and 2 illustrated the novelty of this paper by comparing the related literature with this paper.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft and revising, R.R.; participating in the discussion of the literature and polishing English, Z.L., X.A. and J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the 2019 provincial undergraduate innovation and entrepreneurship training program of Chengdu Normal University (S201914389037).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bacaer, N.; Gomes, M.G.M. On the final size of epidemics with seasonality. Bull. Math. Bio. 2009, 71, 1954–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nabti, A.; Ghanbari, B. Global stability analysis of a fractional SVEIR epidemic model. Math. Meth. Appl. Sci. 2021, 44, 8577–8597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Abbes, A.; Jahanshahi, H.; Alotaibi, N.D.; Wang, Y. Fractional-order discrete-time sir epidemic model with vaccination: Chaos and complexity. Mathematics 2022, 10, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihan, F.A.; Al-Mdallal, Q.M.; AlSakaji, H.J.; Hashish, A. A fractional-order epidemic model with time-delay and nonlinear incidence rate. Chaos Solit. Frac. 2019, 126, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.; Zhu, Q. Impulsive method to reliable sampled-data control for uncertain fractional-order memristive neural networks with stochastic sensor faults and its applications. Nonlinear Dyn. 2020, 100, 2595–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Zhong, S.; Wen, S. Improved approach to the problem of the global Mittag–Leffler synchronization for fractional-order multidimension-valued BAM neural networks based on new inequalities. Neu. Net. 2021, 133, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X. Time periodic traveling wave solutions for a Kermack-McKendrick epidemic model with diffusion and seasonality. J. Evol. Equ. 2020, 20, 1029–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Cui, R. Qualitative analysis on an SIRS reaction-diffusion epidemic model with saturation infection mechanism. Nonlinear Anal. RWA 2021, 62, 103364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zhang, L.; Teng, Z. Dynamics in a reaction-diffusion epidemic model via environmental driven infection in heterogenous space. J. Biol. Dyn. 2021, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, R. Asymptotic profiles of the endemic equilibrium of a reaction-diffusion-advection SIS epidemic model with saturated incidence rate. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst. B 2021, 26, 2997–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Braverman, E. Time-delay systems with delayed impulses: A unified criterion on asymptotic stability. Automatica 2021, 125, 109470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Qiu, J. Input-to-state stability of nonlinear systems with hybrid inputs and delayed impulses. Nonlinear Anal. Hybrid Sys. 2022, 44, 101145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Zhu, Q. Stability criteria for impulsive stochastic functional differential systems with distributed-delay dependent impulsive effects. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cyb. Syst. 2021, 51, 2027–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R. Impulsive control and global stabilization of reaction-diffusion epidemic model. Math. Meth. Appl. Sci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Zhu, Q.; Karimi, H. Some improved Razumikhin stability criteria for impulsive stochastic delay differential systems. IEEE Trans. Auto. Control 2019, 64, 5207–5213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Cao, J. Parameter estimation algorithms for hammerstein finite impulse response moving average systems using the data filtering theory. Mathematics 2022, 10, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Q.; Zhu, W. Event-triggered impulsive optimal control for continuous-time dynamic systems with input time-delay. Mathematics 2022, 10, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Zhu, Q. Razumikhin-type theorem for pth exponential stability of impulsive stochastic functional differential equations based on vector Lyapunov function. Nonlinear Anal. Hyb. Syst. 2021, 39, 100983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Cao, J. Robust exponential stability of markovian jump impulsive stochastic cohen-grossberg neural networks with mixed time delays. IEEE Trans. Neu. Net. 2010, 21, 1314–1325. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Li, P. Stability of time-delay systems with impulsive control involving stabilizing delays. Automatica 2021, 124, 109336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Liu, X.; Zhong, S. Stability criteria for impulsive reaction-diffusion Cohen-Grossberg neural networks with time-varying delays. Math. Comput. Model. 2010, 51, 1037–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).