Abstract

Vocabulary instruction is a critical component of language and literacy lessons, yet few studies have examined the nature and extent of vocabulary activities in early elementary classrooms. We explored vocabulary activities during reading lessons using video observations in a sample of 2nd- and 3rd-grade students (n = 228) and their teachers (n = 38). Teachers spent more time in vocabulary activities than has been previously observed. In the fall, 28% of their literacy block was devoted to vocabulary in 2nd grade and 38% in 3rd grade. Our findings suggest that vocabulary activities were most likely to take place prior to reading a text—teachers rarely followed-up initial vocabulary activities after text reading. Analysis of teachers’ discourse moves showed more instructional comments and short-answer questions than other moves; students most frequently engaged in participating talk, such as providing short, simple answers to questions. Students engaged in significantly more talk during vocabulary activities (including generative talk such as initiating an idea) in the spring of 3rd grade than the spring of 2rd grade. These data contribute descriptive information about how teachers engage their students in vocabulary learning during the early elementary years. We discuss implications for practice and future research directions.

1. Observations of Vocabulary Activities during Second- and Third-Grade Reading Lessons

Across studies and over time, scholars have found that students’ vocabulary knowledge is significantly associated with their achievement in reading comprehension [1,2,3,4]. This is the case for students in the early stages of learning to read as well as the middle- and high-school years [1,5,6]. The connection between vocabulary knowledge and reading comprehension achievement is both specific (that is, a large number of unfamiliar words make a text hard to understand) and general (that is, limited vocabulary is associated with limited achievement in reading comprehension [4,7,8,9].

Children come to school with varying funds of vocabulary knowledge that are largely attributable to the opportunities they have to learn words in their homes and communities [10]. Learning to read provides all students opportunities to learn new words, but even so, differences in vocabulary knowledge tend to persist through the elementary years [1,11]. The consensus is that instruction in vocabulary should begin when children start school, involve the development of oral and print vocabulary, and be a regular component of teachers’ reading lessons [12,13,14,15,16].

In recent years, there has been considerable interest in determining effective methods for teaching vocabulary skills. According to Hairrell, Rupley, and Simmons [17], six reviews and two meta-analyses centered on methods of vocabulary instruction have been published between 1998 and 2009. Most recently, Wright and Cervetti [9] reviewed 36 studies that examined the effects of vocabulary instruction on reading comprehension. In theory, the extent of students’ word knowledge (both depth and breadth) contributes to their comprehension of texts [4,18,19]. The number of different words they know and the depth of their knowledge further contribute to how well they grasp ideas and information in written texts. Yet, acquiring depth of knowledge about words takes time, practice, and experience [20], thus, it is not surprising that exposure to a variety of instructional methods and reinforcement of concepts through a variety of activities is one promising approach to support vocabulary development [2,9].

The National Reading Panel report [2] emphasized the value of direct instruction, repeated or multiple exposures to words, learning words in rich contexts, and students’ active engagement in literacy activities. Similar recommendations are found in other reviews and meta-analyses [17]; however, recent research has shown that some methods appear to be more effective than others. Wright and Cervetti [9] reported that neither direct teaching of word meanings nor instruction in just one or two strategies has a significant effect on general measures of reading comprehension. More promising are methods that require students to participate in active processing of words and their meanings, involving a variety of different types of word-learning strategies [4].

Of considerable concern is the fact that few studies have examined the methods and time teachers actually devote to vocabulary instruction, especially in the early elementary years. As a result, we do not know whether teachers’ practices conform to findings of studies that have identified effective methods of vocabulary instruction. This gap in our knowledge of early literacy instruction is important to address because 60% of fourth graders lag behind standards for proficiency in reading comprehension [21]. The RAND study group [3] highlights this issue by asking; “How does the teaching community ensure that all children have the vocabulary and background knowledge they need to comprehend certain content areas and advanced texts?”

The results of several observational studies in the early grades suggest limited attention to vocabulary instruction and a tendency to provide brief definitions or explanations of words. For example, Wright and Neuman [16] found that teachers tended to provide in-the-moment explanations of words encountered in books they read to their kindergartners. Explanation of a word’s meaning was very brief, and there were no systematic efforts to reinforce students’ understanding of words. Two other recent studies have used audiorecorded vocabulary instruction in early elementary classrooms to characterize the nature of teachers’ discourse during vocabulary activities [22,23]. Their results confirm the frequency of the kinds of brief explanations of word meanings that Wright and Neuman [16] found in their kindergarten observations.

While there is much we need to know about vocabulary instruction in early elementary classrooms, we do know that a number of books suggesting methods of teaching vocabulary are available to teachers [20,24,25,26]. Most core or comprehensive reading programs include systematic vocabulary activities that teachers are advised or required to use. Teachers in Wanzek’s [23] focus groups, for example, indicated that their vocabulary instruction consisted of reviewing the word list for a given text recommended by the core reading program. They also reported feeling strapped for time—not having enough instructional time to target all the vocabulary activities outlined within the core reading program. As a practical matter, educators might benefit from further studies of current practices in teaching vocabulary in early elementary classrooms, with the goal of understanding the extent to which practices meet standards and expectations derived from theories and results of empirical studies. Because student uptake of lessons is critical [27], there is value to having information about teachers’ instructional practices during vocabulary activities and students’ participation in these activities. This would constitute a first step toward determining whether students receive adequate opportunities to develop the vocabulary knowledge they need to comprehend increasingly challenging academic texts.

2. Teaching Vocabulary within the Context of Reading Lessons

In an effort to understand current instruction in vocabulary in the elementary years, we carried out a study in which we analyzed observations of entire reading lessons (i.e., the literacy block) in 2nd and 3rd-grade classrooms in the fall and spring. Within these lessons, we focused specifically on teachers’ activities involving oral language and print vocabulary. In early elementary classrooms, studies have suggested that teachers tend to integrate instruction in various areas of reading during lessons. They might plan lessons that include any of the five foundational skills that the National Reading Panel Report considered essential components of reading instruction [2]: phonemic awareness, decoding, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension. They also might adjust their planned lessons to meet students’ needs—for example, by reviewing the meaning or pronunciation of words as students are reading and discussing a text. Thus, in our study, we examined vocabulary activities within the context of such lessons.

Teachers’ integration of instruction across various areas of reading had implications for our study. One was the expectation that instruction would go beyond memorizing definitions; teachers would embrace activities that build conceptual representations, and when necessary, use discourse moves to help students integrate word meanings with their existing knowledge [9]. Another was the expectation that some vocabulary activities would be planned and others spontaneous; there are times, for example, when anything more than a brief explanation of a word would disrupt the flow of a lesson [14]. In both cases the teacher needs to help the students link the meaning of a new word to their previous knowledge or experience. The two examples below (excerpts from observations of early elementary classrooms) illustrate this. In the first example, the teacher reviews vocabulary words with her students prior to reading the text, she makes an effort to link the word’s meaning to a student-friendly usage. The second example illustrates a brief exchange while reading a text in which the teacher uses the students’ personal experience to help them understand the meaning of a word.

In the following example, the teacher is directing a small group of four students. She first calls the students to the carpet to review the vocabulary words that they will see in the story they are about to read.

- T:

- For our vocabulary words this week, we are going to talk about the words clutch and refuse. If you clutch something, you hold it tight. If you refuse something, you do not want it. S1, if you refuse to do something, are you going to do it or are you not going to do it?

- S1:

- Not going to do it.

- T:

- Right. If you refuse something, you are not going to do it. Now, I’m going to name things that you might clutch or refuse. If you think you should clutch, do this with your hands [motions with hand]. If you think you should refuse it, do this with your hands [motions with hand]. Okay? [Teacher models hand motions again]. I’m going to clutch or I’m going to refuse.

- T:

- Monkey bars on the playground. Clutch or refuse?

- Ss:

- Clutch [students chorally respond].

- T:

- A basketball. Are you going to clutch it or refuse it?

- S1:

- Let it go. You are going to clutch it at first and then let it go.

- T:

- Good. And if you are getting the ball away from someone else, you might clutch it. Okay. Let’s go get our reading books and head to the back table. We’re going to read a story called the Great Ball Game.

In this example the teacher uses the students’ experience to help them grasp the meaning of the word “vigorously.” Students have read a story on their own; now the teacher is reviewing the story with them, asking them questions. One of the students is reading a portion of the text aloud, and he stops on the word “vigorously.”

- T:

- I am guessing you are unsure about that word, right?

- Ss:

- [nods in agreement]

- T:

- Vigorously. How many people participated in the walking club outside?

- Ss:

- [A number of students raise their hands]

- T:

- So when you are walking around the track, do you go very slowly or do you go quickly?

- Ss:

- [several say “quickly” enthusiastically]

- T:

- So you are going vigorously; you are doing something with energy. You are not just dragging, you are doing something vigorously. Does that make sense in the sentence you just read, S1?

- S1:

- Yeah, it does.

Because we set out to study vocabulary instruction that involved both planned and spontaneous, in-the-moment explanations and discussion of new words, our observation study may present a somewhat different picture of vocabulary learning than has been recorded by other studies, some of which focus on older students [27]. With regard to younger students, Graves [25] and Watts [15] noted that observed vocabulary instruction largely focused on pre-reading activities that most often involved looking up and writing down definitions of words. However, we were also interested in extended lessons, those that included discussions of vocabulary during and after time spent reading a text.

With regard to the time devoted to vocabulary, Watts [15] found that 10% of the time in 4th grade reading lessons was spent on vocabulary. Several more recent observation studies in the early elementary years provide some insight into both the amount of time spent on vocabulary and teachers’ preferred instructional methods. Connor, Spencer, Day and colleagues [28] observed literacy lessons in 3rd-grade classrooms and reported that students spent about 5 min on average engaged in oral language and print vocabulary activities. Wanzek [23] gathered information about “direct instruction” in vocabulary in 2nd-grade classrooms. Fourteen teachers audiorecorded their literacy instruction for three sequential days; analysis of the data showed that 8% of the core reading lesson was devoted to vocabulary (the range was 0–23 min). Direct instruction in this study included a wide range of vocabulary instructional methods; the most commonly observed were giving word definitions and providing examples of word meanings. Much less common were morphology instruction, context clue instruction, semantic instruction, and discussion.

Other studies have also characterized teachers’ discourse during vocabulary activities. Michener et al. [22] audiorecorded vocabulary instruction in 31 3rd–5th grade classrooms three times during the school year to examine the relation between teachers’ discourse moves and students’ reading comprehension outcomes. They found that two teacher discourse moves, teacher explanations and follow-up questions, predicted students’ reading comprehension.

In an observational study, Carlisle, Kelcey and Berebitsky [29] examined four particular discourse practices that teachers were likely to use during vocabulary instruction in 2nd- and 3rd-grade classrooms. The most common was asking students to read vocabulary words in sentences from workbook exercises (31.6%). This finding was seen as reflecting teachers’ use of the required basal program in their schools. In about 25% of the lessons, the teacher defined words and/or asked students to examine the meaning of a word in context. Far less common were asking students to define a word (9.5%) and fostering discussion (7.6%). One finding of interest was that when a teacher employed a rarer action (e.g., asking students to define a word), he or she had a high probability of employing the more common actions as well. In another study of 2nd- and 3rd-grade vocabulary activities during reading lessons, Kelcey and Carlisle [30] noted differences between common and infrequent discourse actions; explaining words or word contexts was observed in 75% of the lessons; asking questions and providing practice in 77% and 75% of the lessons respectively. Less common were fostering discussion (40%) and giving students an opportunity to ask questions (32%).

On the basis of these observational studies, we developed expectations about the actions or “moves” that we might expect 2nd- and 3rd-grade teachers to use frequently in vocabulary activities. These included the following: telling/explaining word meanings (including student-friendly usages), asking basic questions about word meanings, and asking students to read words or words in sentences aloud. Less common would be teachers’ efforts to engage students in discussion of a word’s meaning or asking for students’ explanation of words in context—actions that stimulate students’ thinking. We expected to see more use of discourse moves that engage students’ thinking in the 3rd than in 2nd grade because both teachers and reading researchers have suggested that reading presents greater challenges in 3rd grade [23,31]. We had no reason to expect differences in basic discourse moves by grade level or timing of observation (fall versus spring). The example below illustrates three types of teachers’ common or basic vocabulary discourse moves. To help the students understand the new vocabulary words, the teacher explains the word meanings, asks the students basic questions about the words, and asks them to read sentences that include the vocabulary words aloud.

This 2nd-grade teacher is introducing new vocabulary words during a small group vocabulary activity.

- T:

- Now, the next word is clamber. Does anyone know what that means?

- Ss:

- [students nod their heads “no”]

- T:

- Clamber means to climb up something with both hands and feet.

- S2:

- Like a puppy! When a puppy gets up, he goes like this [student acts out puppy climbing].

- T:

- Yes, and a panda bear might also clamber up the tree to get leaves.

- Ss:

- [students pretend to climb up a tree like a panda bear]

- T:

- The next word is clumsy. If you are clumsy, you might trip and fall over things sometimes. Let’s read a few sentences together that have the word clumsy in them.

- Ss:

- [Teacher and students read together]. The clumsy lamb was wobbly. The clumsy puppy took a step.

However, we were aware that observing and counting the particular vocabulary discourse moves (e.g., explaining word meanings) teachers use offers a limited view of the opportunities students have to acquire deep understanding of new words. It seemed important to go beyond teaching techniques by recording and analyzing students’ response to their teachers’ practices. We were particularly interested in the extent to which students gave relatively rote responses to teachers’ questions, as opposed to demonstrating a deeper interest in word meanings. A number of researchers [9,14,17] note that in theory students’ active processing is central to word learning. Active learning may grow out of discussion in which students explore their understanding of words. Student explanations and discussion are thought to reflect the quality of their verbal reasoning and metalinguistic development [22,32]. They need to make connections between new and known information, and they need to acquire depth of knowledge about word meanings (e.g., different meanings or ways to use a word). Discussion is one way to achieve that goal, albeit not the only way. Blachowicz and Fisher [33] proposed that for instruction to be effective, it should have the goal of immersing students in exploring word meanings, taking ownership of words as they become comfortable using them orally and in their writing.

Thus, for our observations of students’ engagement in the vocabulary activities, we included a set of moves focused on their basic responses (participating talk) and a set focused on their generative/interactive responses (generative talk). Examples of participating talk are answering short-answer questions or reading aloud; examples of generative talk are sharing ideas, initiating questions, and participating in a discussion. We expected that generative responses would be greater in 3rd than 2nd grade. The example below illustrates both participating and generative talk.

This 2nd-grade teacher is introducing a new text to a small group. To make sure the students understand the title, the teachers encourages them to make connections (text-to-self) with the word, celebration. The students answer her “short-answer” questions but in doing so also share ideas.

- T:

- What does celebrations mean?

- S:

- It’s a birthday party, like when you do something fun with cake and balloons and stuff.

- T:

- Anyone else? Another kind of celebration?

- S:

- We celebrate Easter.

- T:

- Okay, what else?

- S:

- Birthday.

- S:

- Christmas.

- T:

- That is definitely a celebration. So our story this week is called “City Celebrations.” How could a city celebrate? What do you think it might do that? City celebrations? Have you ever heard of anything?

- S:

- Fourth of July.

- T:

- Could a city have a birthday?

- Ss:

- Yes [chorally respond].

Experts in vocabulary instruction argue that students need to have a chance to experience the use and meaning of words in different contexts and have opportunities to use words. To achieve this goal, researchers suggest that learning unfamiliar words depends in large on repeated exposures [34]. Beck and McKeown [35] and Coyne et al. [36] found that extended, rich vocabulary instruction led to better learning than instruction that was rich but of relatively short duration. Thus, we expected vocabulary activities to take place at different times, relative to engagement in reading and discussing a text—that is, before reading, while reading, or after reading a text. At least some teachers were likely to carry out vocabulary activities, both before and after text reading in order to provide extended opportunities to engage in understanding unfamiliar words [35].

To summarize, our study was designed to contribute descriptive information about how teachers engage their students in vocabulary learning. One particular interest is the ways that teachers include vocabulary activities in reading lessons, as it is apparent they also use considerable portions of the literacy block to help students acquire foundational reading skills. This includes examining the duration of time teachers engage their students in oral language and print vocabulary activities as well as the timing of their instruction—whether vocabulary activities preceded and/or followed text reading within the lesson. A second interest is the nature and extent of both teachers’ moves and students’ participation, evaluating the frequency and types of talk teachers and students used during vocabulary activities. Information pertaining to these aspects of vocabulary instruction in the early elementary years should help guide future research designed to examine the effects of these practices on students’ reading comprehension. Our overarching research question is: what do classroom observations tell us about vocabulary instruction within early elementary reading lessons? We outline our four research questions below.

- What percentage of the reading lesson is designated to vocabulary activities, and does this vary for 2nd- and 3rd-grade students?

- What discourse moves (those that involve basic instruction of word meanings and those that involve discussion of meanings) are teachers using during vocabulary activities, and are there differences between 2nd and 3rd grade?

- How often are students exhibiting participating and generative talk during vocabulary activities, and are there differences between 2nd and 3rd grade?

- When are teachers delivering vocabulary instruction during reading lessons? More specifically, what is the probability that vocabulary activities precede and/or follow text reading during the reading lesson?

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

Our study included students in second (n = 114) and third grade (n = 114) and their teachers (n = 19 2nd grade; 19 3rd grade) across five schools who were drawn from a longitudinal study of reading comprehension instruction in the early elementary years between 2009 and 2011 [37]. Participating teachers and families provided informed consent after all study procedures, potential risks, and benefits were disclosed prior to the start of the study, and Institutional Review Board approval was maintained throughout the longitudinal study. Participating teachers were 96% female; 95% identified as White. They reported an average of 16 (SD = 8.87) years of teaching experience. Eighteen percent of the teachers reported having an M.A or M.S. degree, and 5% reported having an M.Ed. As part of the larger study, six students were randomly selected from each classroom based on their reading ability, selecting two higher achieving, two typical, and two lower-achieving students per classroom.

3.2. Procedures

All 2nd- and 3rd-grade teachers followed a 90-min district-mandated block of time devoted to literacy instruction. During this time, teachers used the district-mandated curriculum, Harcourt Trophies, and other reading materials (e.g., trade books with narrative and expository texts). As part of the larger project, reading lessons (i.e., the literacy block) were video-recorded three times across the school year, once in the fall, winter, and spring. However, the current study only utilized observations from the fall and spring of the school year. Trained research assistants coded the reading lessons using the observation system, Individualized Student Instruction (ISI) [37,38], which is a multi-dimensional observation tool that describes student-level classroom reading activities. In addition, teachers’ discourse moves and students’ responses were coded during teacher-managed literacy activities that centered on text-based topics using the observation system, Creating Opportunities to Learn from Text (COLT) [39]. The video observations were coded using Noldus Observer® Video-Pro Software (Noldus Information Technology, Leesburg, VA, USA, 2010). The teacher and the six target students per classroom were coded with the COLT system. Both the ISI and COLT observation systems have good reported interrater agreement, with a Cohen’s Kappa coefficient score of 0.72 for ISI and scores ranging between 0.78–0.90 for COLT.

Vocabulary Activities. We analyzed the amount of time that teachers and students spent in two types of vocabulary activities (oral language and print vocabulary) during reading lessons in the fall and the spring. We also examined the frequency of teachers’ discourse moves and students’ responses during vocabulary activities. As outlined in the ISI observation system, oral language activities focus on increasing students’ oral vocabularies (i.e., their ability to access a word’s meaning upon hearing it) and/or listening and speaking skills when print or text is not present, whereas, print vocabulary activities focus on increasing students’ ability to access a word’s meaning upon seeing its written form. All activities outlined in the ISI observation system last at least 15 s; thus the system detects even minimal times that teachers spend teaching vocabulary as well as how they may move in and out of vocabulary activities during the reading lesson. Finally, we coded vocabulary activities without regard to grouping arrangement (whole-class and small-group sessions) because instruction did not always conform to a single format. For example, the teacher might start with the whole class, have students work in small groups for a short time, and then reconvene the whole group.

Teacher Discourse Moves and Student Responses. Our conceptualization of teachers’ discourse moves and students’ responses were adapted from the COLT Observation system to identify and measure teacher discourse moves that support student reading comprehension gains within early elementary classrooms. Appendix A provides a list and description of the teacher discourse moves and student responses. Full manuals are available from the authors upon request.

The COLT system outlines discourse moves that have been identified as key components in the process of teaching reading comprehension, such as efforts to extend students’ talk and promote higher-order thinking. In the current study, we describe two broad categories of teacher discourse moves that, based on the research literature, we might expect 2nd- and 3rd-grade teachers to use during vocabulary activities. Basic Instruction in Word Meanings includes a set of commonly observed discourse moves, such as reading aloud to students, providing explanations, and asking short-answer questions. Discussion/Elaboration of Word Meanings includes less common moves that engage students’ thinking, such as facilitating sharing of ideas, asking follow-up questions, and challenging students to reason.

We also adapted student responses from the COLT system, outlining two dimensions of student talk that represent key aspects of vocabulary teaching and learning. Participating talk, students’ responses that show active involvement in learning activities, includes such responses as answering simple questions, choral responding, and reading text aloud. Generative talk, talk that focuses on cognitive engagement in which students construct or generate new information, includes such responses as answering questions that require thinking, sharing ideas, and participating in discussions.

4. Results

4.1. Data Preparation

It is important to note that 2nd- and 3rd-grade classrooms were included in the analyses only if they had both fall and spring classroom observations. We summed the total number of responses of the six students in each classroom and reported the average of the summed responses. The median of students’ choral responses, in which teachers asked the students to respond together, were used rather than summing. Distribution properties were examined through descriptive statistics for each of the teacher discourse moves and student responses. We identified one outlier for the teacher discourse moves (asking short-answer questions) in the spring of 2nd grade and one in the fall of 3rd grade. We also identified two outliers for student responses in the fall of 2nd grade (choral responding and taking notes to dictation). We then combined the variables to comprise two categories of teacher discourse moves (Basic Instruction in Word Meanings and Discussion/Elaboration of Word Meanings) and two categories of student responses (participating talk and generative talk) for both 2nd and 3rd grade separately—all of which were normally distributed (skewness < 2).

4.2. Vocabulary Activities in 2nd and 3rd Grade

RQ1. What percentage of the reading lesson is designated to vocabulary activities, and does this vary for 2nd- and 3rd-grade students?

Time Spent on Vocabulary Activities. We examined the amount of time that teachers spent teaching oral language and print vocabulary activities during their designated literacy block, using time metrics; from the duration of time and proportion metrics we derived a percentage score reflecting time on vocabulary activities out of the total reading lesson (literacy block). The literacy block in 2nd grade ranged from 120 min in the fall to 121 min in the spring. In 3rd grade it ranged from 103 min in the fall to 93 min in the spring. In the fall of 2nd grade, teachers spent an average of 31 min (SD = 26), 28% of their reading lesson, on vocabulary activities. This dropped to 24 min (SD = 16), 21%, in the spring although the length of the literacy block was consistent from fall to spring. Teachers designated 38 min (SD = 23) or 39% of their reading lesson to vocabulary activities in the fall of 3rd grade and 29 min (SD = 18), 30%, in the spring. These means might suggest that time spent on vocabulary was greater in 3rd than 2nd grade, but we did not statistically examine this because of differences in the time designated to literacy blocks in the two grades.

4.3. Teacher Discourse Moves

RQ2. What discourse moves (those that involve basic instruction of word meanings and those that involve discussion of meanings) are teachers using during vocabulary activities, and are there differences between 2nd and 3rd grade?

Types of Discourse Moves. Count metrics were used to provide information on the total number of occurrences that teachers used discourse moves in both categories, Basic Instruction in Word Meanings (basic) and Discussion/Elaboration of Meanings (discussion). We first calculated the total number of occurrences for each discourse move and then combined these and calculated the average number of occurrences by category. See Table 1 for means and standard deviations of each teacher discourse move and each category. Overall, 2nd-grade teachers used 58.42 (SD = 48.99) basic discourse moves on average in the fall and 29.63 (SD = 27.29) in the spring. We observed a similar pattern in 3rd grade, with teachers using 63.79 (SD = 41.64) basic moves in the fall and 47.47 (SD = 38.64) in the spring of the school year. Consistent with the current literature, we observed less frequent use of discussion moves in 2nd grade (M = 5.84; SD = 8.60) than 3rd grade (M = 8.00; SD = 6.72)—both fall and spring of the school year.

Table 1.

Teacher discourse moves in vocabulary activities.

Differences between 2nd and 3rd Grade. Using multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA), we did not observe significant differences in basic or discussion moves between 2nd and 3rd grade.

4.4. Student Participation

RQ3. How often are students exhibiting participating and generative talk during vocabulary activities, and are there differences between 2nd and 3rd grade?

Types of Student Responding. Count metrics were used to provide information on the total number of occurrences that students exhibited participating and generative talk during the vocabulary activities. Similar to teacher discourse moves, we first calculated the total number of occurrences for each student response and then combined these and calculated the average number of occurrences by category. See Table 2 for means and standard deviations of each student response and each category. On average, 2nd-grade students exhibited 25.53 (SD = 28.49) participating and 3.68 (SD = 4.93) generative responses in the fall. In the spring, students in 2nd grade exhibited 13.00 (SD = 15.13) participating and 2.16 (SD = 2.27) generative responses. In 3rd grade, students exhibited 45.10 (SD = 29.69) participating responses and 7.95 (SD = 6.98) generative responses on average in the fall; they exhibited 28.42 (SD = 21.23) participating and 2.79 (SD = 5.99) generative responses in the spring.

Table 2.

Student responses during vocabulary activities.

Differences between 2nd and 3rd Grade. Using MANOVA, we next evaluated whether significant differences in participating and generative talk existed between 2nd and 3rd grade. The results indicated that differences in students’ responses between grades in the fall of the school year were not statistically significant. However, we did find differences in the spring, with students exhibiting significantly more participating talk, F (1) 36 = 5.57, p = 0.024, and more generative talk, F (1) 36 = 7.012, p = 0.012, in 3rd grade than in 2nd grade.

4.5. Timing of Vocabulary Activities during Reading Lessons

RQ4. When are teachers delivering vocabulary instruction during their reading lessons? More specifically, what is the probability that vocabulary activities precede and/or follow text reading during the reading lesson?

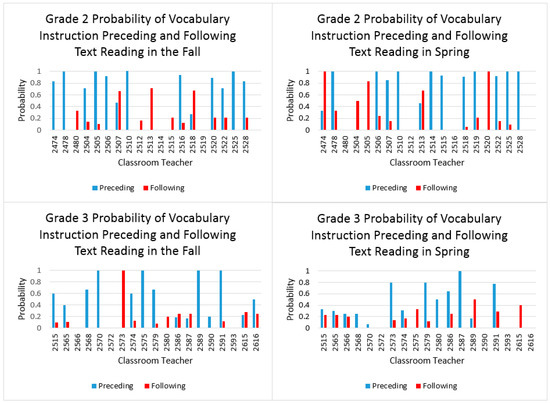

Lag sequential analysis was used to observe the pattern of when teachers delivered vocabulary activities during the reading lesson. We were interested in further understanding whether vocabulary activities took place before or after reading a text, whether this varied from fall to spring, and whether this varied from 2nd to 3rd grade. In 2nd grade, there was a 0.58 probability that vocabulary activities took place before reading a text in the fall and a 0.60 probability in the spring. However, there was only a 0.20 probability that vocabulary activities followed text reading in the fall and a 0.28 probability in the spring. This pattern was similar in 3rd grade. There was a 0.43 probability that vocabulary activities preceded text reading in the fall and a 0.33 probability in the spring. Yet, there was only a 0.15 probability that vocabulary activities followed text reading in the fall and a 0.15 probability in the spring.

Figure 1 outlines the probability of vocabulary activities preceding (blue) and following (red) text reading in the fall and spring per classroom in 2nd and 3rd grade. We found marked variability between the classrooms and seasons, yet the likelihood that teachers delivered vocabulary activities following text reading was overall low, with 16 2nd-grade teachers at or below 0.30 probability in the fall and 15 teachers in the spring. Similarly, 18 of the 19 3rd grade teachers fell at or below a 0.30 probability in the fall and 17 teachers in the spring. Finally, of the total 19 classrooms, eight 2nd-grade and nine 3rd-grade teachers spent time teaching vocabulary both before and after text reading in the fall and nine 2nd- and 3rd-grade teachers did so in the spring.

Figure 1.

Probability of vocabulary activities preceding and following text reading.

4.6. Additional Exploratory Analyses

After observing means and standard deviations of students’ responses, we carried out additional analyses to evaluate whether differences in participating and generative talk existed across the school year. Although not part of our initial hypotheses, it appeared that students responded overall less often in the spring compared to the fall of the school year. We used repeated measures ANOVA to examine mean differences in students’ responses between the fall and spring. Findings indicated a significant difference in student participating talk, F (1) 35 = 6.88, p = 0.013, between the fall and the spring, with students exhibiting significantly more participating talk in the fall than spring at both grade levels. Differences between students’ generative talk from fall to spring were approaching significance, F (1) 35 = 3.80, p = 0.059.

5. Discussion

Vocabulary instruction is a critical component of language and literacy lessons in the early school years; it plays a very important role in the development of students’ reading comprehension. No wonder experts, such as the RAND Study Group [3], ask whether vocabulary instruction in the elementary years is of sufficient quality to prepare students for the challenges of reading and learning in content areas through school and beyond. In order to answer this question, we need to gather information about the nature and extent of classroom vocabulary activities in these years. To address this need, we examined teachers’ vocabulary activities during reading lessons using video observations of early elementary classrooms. We explored the amount of time teachers spent teaching vocabulary activities during their larger literacy block and the timing of teachers’ vocabulary activities—that is, how they intertwined vocabulary activities within their reading lessons. We also evaluated teachers’ discourse moves and the type and frequency of students’ responding. Our study extends the current literature by providing detailed information regarding elementary classrooms’ vocabulary activities as well as a foundation for future research to examine how much and what kind of vocabulary instruction may be most beneficial to students as they are learning to read and comprehend text. We outline implications for practice and future directions.

5.1. Teaching Vocabulary Activities during Reading Lessons

In contrast to previous reports of the small amounts of time designated to vocabulary instruction during reading lessons [28], we found that teachers devoted a good portion of their reading lessons to vocabulary activities, especially in the fall of the school year. Third-grade teachers spent an average of 38 min and 2nd-grade teachers spent an average of 31 min teaching vocabulary activities. We observed a decrease in the percentage of time that teachers spent teaching vocabulary activities from the fall to the spring, with 3rd-grade teachers designating 29 min (30%) and 2nd-grade teachers designating 24 min (21%) to vocabulary activities, although we have no basis for interpreting this decrease.

By way of comparison, Watts [15] reported that 10% of reading lesson time was spent on vocabulary; similarly, Wanzek [23] found that 8% of the time was spent on vocabulary. One possible reason for our larger percentages is that the district mandated an uninterrupted block of at least 90 min for literacy lessons in the state of FL, allowing more time for language activities that supplemented text reading. In some cases this involved the use of mandated curriculum and activities required within Reading First schools. Particularly in Reading First schools, teachers were likely to be aware that vocabulary was one of the five required areas of instruction recommended by the National Reading Panel Report [2]. Another explanation for the relatively large amount of time spent on vocabulary may reflect the use of video observations and our observation system. We coded vocabulary activities within classroom observations using a coding system that allowed us to capture both planned and incidental vocabulary activities, such as brief exchanges between teachers and their students around vocabulary words. For example, during a whole group vocabulary activity, a 3rd-grade teacher helped her student make a text-to-self connection when she came across the word “dense” in the text.

- T:

- The trees are very close together?

- S1:

- Yes.

- T:

- So you live by a dense wooded area, don’t you?

- S1:

- Yes.

- T:

- So in a dense forest, are there going to be 1 or 2 pine trees or a whole bunch of pine trees?

- S1:

- A whole bunch.

It is likely that we captured more incidental opportunities to talk about word meanings than has been found in most other studies, although Wright and Neuman [16] found that brief explanations of word meanings was a primary means of vocabulary development in kindergarten classes. Because our study is limited by the number of video observations in each classroom and across classrooms, we have only a snapshot of what is happening within reading lessons. That is, there is much variability in how teachers plan or adjust activities during reading lessons. The frequency of in-the-moment explanations of the meaning of a word might come about because teachers want to respond to students’ needs [14]. Furthermore, the teachers’ goals/objectives of the lesson might not focus on students’ familiarity with vocabulary words in a given lesson. It is possible that, by the spring of the school year, teachers in our study focused more on text comprehension and less on the meanings of particular words. To examine such changes, researchers would need to carry out a more comprehensive set of observations across a school year. Still, even with the decrease of time we documented from fall to spring, more time was spent teaching vocabulary activities than has often been reported.

5.2. Teachers’ Discourse Moves during Vocabulary Activities

We next took a closer look into what was happening within vocabulary activities. We observed and examined a set of teacher discourse moves, collapsing specific moves into two broad categories. Basic discourse moves include moves, such as asking students short-answer questions and providing them with definitions—moves that have been commonly observed in previous studies of vocabulary instruction [23]. Less common are discourse moves that teachers’ use to encourage discussion and elaboration centered on word meanings, such as facilitating sharing of ideas and challenging students to reflect on alternative meanings of a word. Similar to previous studies [22,29], we found that teachers most frequently used basic discourse moves during the vocabulary activities, especially in the fall of the school year. Surprisingly, however, we did not observe significant differences in teacher discourse moves between 2nd and 3rd grade as we had expected.

We found that teachers in both grades made instructional comments and asked short-answer questions relatively more often than all other moves. Similar to the findings of Wright and Neuman [16], we found that the teachers commonly provided brief explanations of words without efforts to support students’ understanding beyond the immediate use of the word in a text. For example, during a 2nd-grade reading lesson, the students come across the word “mare” while reading the story, Visit to the County Fair. The student that is reading pronounces the word “mare” as “mayor.” The teacher takes a few minutes to explain what “mare” means before having the students continue reading.

- T:

- What’s a mare?

- S2:

- It’s like a type of horse.

- T:

- A type of horse, and a mare is the type of horse that can have a baby horse. There is another kind of mayor (writes out word “mayor” on a piece of paper) that leads the city, someone that is the leader of a city is called the mayor, spelled like this (she shows the students the word “mayor”). But not mare. This word is mare. A horse. A female horse.

Studies have suggested that the most promising types of teacher-led vocabulary activities for impacting comprehension go beyond having students memorize word meanings. Rather, students become active participants in the word learning process [9,35]. They should have ample opportunities to review and practice using new words and be comfortable using multiple word-learning strategies. The results of our study reveal the relatively infrequent times that teachers introduce discussion or elaboration of word meanings when familiarizing their students with new words. In these early elementary vocabulary activities, teachers might not be using what experts consider to be the most effective means for developing students’ vocabulary [27]. However, this study provides only an initial look at how teachers are delivering vocabulary activities. Future research is needed to better understand the impact of varying types of discourse moves, or combinations of moves, on student vocabulary learning and reading achievement more broadly.

5.3. Students’ Responses during Vocabulary Activities

Describing Students’ Responses in Vocabulary Activities. In addition to teacher discourse moves, we observed and examined a set of student responses to better understand the type and frequency of student engagement during vocabulary activities. We created two broad categories of students’ responses, adjusting the coding categories in the original COLT system to suit analysis of students’ involvement in vocabulary activities. One is participating talk, which focuses on students’ basic or brief responses, such as providing short, simple answers to questions or raising a hand in response to a question. The other is generative talk, which focuses on students’ reflections of word meanings and thinking about how words are used in different contexts. This involves cognitive engagement, in which students construct or generate new information, going beyond basic memorization [33]. This sort of active engagement with words has been associated with students’ recall of words in vocabulary lessons and with positive effects on reading comprehension [9,17,35]. We found that students most frequently engaged in participating talk overall; we observed very few occurrences of generative talk, especially in 2nd grade.

Differences in Student Responses between 2nd and 3rd Grades. Interestingly, we did not observe significant differences in students’ responses in the fall of the school year between 2nd and 3rd grades. However, we did find that students exhibited significantly more participating and generative talk in the spring of 3rd grade. Students exhibited 13 occurrences of participating talk, on average, in the spring of 2nd grade and 28 occurrences in the spring of 3rd grade. They answered non-verbal and short-answer questions as well as chorally responded more often than other responses. Generative talk also increased from an average of two occurrences in the spring of 2nd grade to 13 occurrences in the spring of 3rd grade. Students more commonly initiated new ideas and answered thinking questions; we observed some occurrences of participating in a discussion and reading self-generated text, although not frequently. In the following example, the teacher facilitates a discussion about the word “stage fright,” drawing on students’ personal experiences to help them understand the meaning of a word.

- S1:

- I was afraid of the dark when I was little.

- T:

- (teacher writing). Okay. I overcame, or let’s put here, I need to overcome.

- S1:

- I need to overcome that but it’s hard.

- T:

- I know it is. Me too.

- S2:

- I like the dark.

- T:

- When I was little, I used to think there were monsters under my bed, and I had to overcome that fear.

- Ss:

- (laughing)

- S3:

- I used to be afraid too. I used to think there was something under my bed too.

- T:

- Thank you for being brave and willing to share.

- S4:

- I was afraid when I was reading my book and everyone was staring at me.

- T:

- I’m going to call that stage fright.

- S4:

- I have stage fright.

- T:

- A lot of people have stage fright. Okay, who else is brave enough to share?

- S1:

- I had to overcome this. I used to be afraid around people I don’t know.

- T:

- You know, that is a good thing. A lot of people are afraid of that. I am too. I can understand that because you don’t know what to say.

- S4:

- I had the same problem. In first grade, I was afraid of singing.

- T:

- You were afraid of singing in front of a group?

- S3:

- Same thing happened to me. I was scared to sing. I was in 2nd grade.

We did expect to observe more generative talk in 3rd grade, given the increasing complexities of the texts. Nonetheless, these findings contribute to a limited body of research overall, as previous studies have solely focused on teachers’ discourse moves without consideration of students’ responses. Although we observed more participating talk overall, it is promising to see the increased amount of participating and generative talk by the end of 3rd grade as well as instances in which students take ownership over their learning, such that they are motivated and interested in learning new words, as observed in the example above.

Differences from Fall to Spring. We observed a significant decrease in students’ participating talk from fall to spring in both 2nd and 3rd grade. It is possible that this is a function of less time spent in vocabulary activities and fewer teacher discourse moves in the spring overall, but further research is needed, as we have no basis for understanding this finding. Students’ use of generative talk from fall to spring was approaching significance, with students exhibiting more generative talk in 3nd grade. Here, too, with the low frequency of generative talk overall, further research is needed to explore the types of generative talk that students exhibit in classroom vocabulary activities and how they vary across the school year.

5.4. Timing of Vocabulary Activities

The few studies that have examined the timing of vocabulary activities within reading lessons have focused on the need for extended opportunities to learn and use selected words [35,36]. Thus, we were interested in better understanding when teachers taught vocabulary activities during their literacy block (e.g., before or after text reading). We evaluated the likelihood that vocabulary activities preceded and followed text reading in both 2nd and 3rd grade, and we found that there was a relatively strong probability that teachers taught vocabulary activities before reading a text at both grade levels. This finding is not surprising as most comprehensive reading programs encourage teachers to familiarize students with words prior to reading the text. As part of the curriculum, teachers might review specific words, gauge students’ understanding of the word meanings, and provide definitions—all before reading a text.

The following example outlines a teacher’s efforts to expose her students to a set of vocabulary words prior to reading the text, The Lion and the Mouse. See Appendix B for the complete excerpt. The teacher provides an opportunity for her students to practice using the new words. She first has them cut out and pair vocabulary words and word meanings, and then asks the students to highlight the key words in the definitions. She then turns their attention to the word “aches”, providing an example of the word to support comprehension.

- T:

- Aches. You told me aches means you don’t want to do it. Listen, “Oh, my elbow aches after playing tennis. My elbow aches after I played tennis (holding her elbow as if it hurts). She then leans toward S3. So, you are telling me aches means you don’t want to do it. Did you hear my sentence about aches?

- S3:

- (nods her head)

- T1:

- My elbow hurts because I played tennis (holding her elbow as if it hurts). She then leans toward S1. Oh, but look here (points to the word and definition). You said that aches means to be the best. Looks like we have a mess up here. Let’s look here. My elbow hurts. My elbow hurts from playing tennis (points to the correct definition).

- S1:

- Aches.

Because experts recommend extended opportunities to engage students in understanding unfamiliar words [35], we expected to see teachers carry out vocabulary activities at several times within a reading lesson—before and after text reading, for example. However, most surprising was the low probability that vocabulary activities followed text reading, especially in 3rd-grade classrooms (0.15 probability that vocabulary activities followed text reading). Examining individual plots (Figure 1) from each classroom illustrate that some teachers spend a lot of time on vocabulary in a given lesson while others spend none at all. Such variability is to be expected, as we noted above, and as others have found as well [30]. Again, these data suggest that many factors influence how, when, and what teachers deliver during the literacy block. Even so, by counting times that both before and after activities take place, we can see that there are relatively fewer instances in which teachers follow up initial vocabulary activities after reading. This finding runs counter to the recommendations of experts in vocabulary instruction who argue that students need multiple opportunities to experience unfamiliar words [20,25]. Thus, our findings bring new urgency to answering the question: are students receiving adequate opportunities to develop the vocabulary knowledge they need to read and comprehend text?

5.5. Strengths and Limitations

This descriptive study contributes to the current literature in several ways. We focused on younger children than in previous studies and examined the type and amount of teachers’ discourse moves and students’ responses during vocabulary activities. The use of video-recorded observations, as well as the ISI and COLT coding systems, allowed for detailed examination of the engagement patterns between teachers and their students during vocabulary activities (both incidental and planned). In addition, we were able evaluate teachers’ and students’ moves in the fall and spring of 2nd and 3rd grade, providing an overview or a snapshot of vocabulary instruction across the school year. The use of lag sequential analysis to evaluate timing of vocabulary activities is a new contribution to the field, following up on recommendations for repeated exposures and extended learning activities to enhance students’ learning of unfamiliar words. Although the descriptive nature of our study in many ways is a strength, it also is a limitation because we were not able to make claims about specific moves that are important for student participation and learning. Nor did we examine how differences in time and talk about vocabulary predicted students’ vocabulary gains. Having just two observations for each teacher and 19 teachers at each grade level also affects our ability to make generalizations and draw conclusions about early elementary vocabulary instruction. Thus, replication and extensions of this study are needed, as is research to evaluate how teacher discourse moves and student responses during vocabulary activities relate to one another and to student reading outcomes. Nevertheless, the results of this study are encouraging. Teachers and students were spending more time in vocabulary instruction than previous studies have indicated; while much of the discourse around vocabulary was fairly low level, we did observe instances when students were engaging in generative talk; and most, but not all vocabulary instruction preceded reading text.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.S., J.F.C. and C.M.C.; Formal analysis, N.S.; Methodology, N.S. and J.F.C.; Validation, N.S., J.F.C. and C.M.C.; Writing—original draft, N.S., J.F.C. and C.M.C.; Writing—review & editing, N.S., J.F.C. and C.M.C.

Funding

This research was funded by the U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences; grant numbers R305A160399 and R305B070074, and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant number R01HD48539.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Teacher Discourse Moves and Student Responses in Vocabulary Activities

| Teachers’ Vocabulary Discourse Moves | Description and Examples |

| Basic Instruction in Word Meanings | |

| Reading aloud to students | The teacher reads words, lists, or text to the students |

| Asking students to read aloud | The teacher calls on one or more students to read words or text |

| Providing explanations/instructional comments | The teacher provides definitions, explanation, or other information about target words |

| Asking questions that require nonverbal responses | The teacher asks students to signal agreement or disagreement (e.g., raise hand) |

| Asking short-answer questions | The teacher asks simple questions to evaluate students’ knowledge of word |

| Discussion/Elaboration of Meanings | |

| Facilitating sharing of ideas | The teacher asks for opinions, points of view, or students’ experiences with a word |

| Asking follow-up questions | The teacher asks questions for clarification or elaboration |

| Challenging students to reason | The teacher asks questions that require inferencing, drawing conclusions, interpretations, or alternative explanations |

| Student Responses | Description and Examples |

| Participating Talk | |

| Answering nonverbal questions | Raising hand in response to teacher question |

| Verbally answering simple questions | Short-answer questions often requesting meaning of word |

| Choral responding | Often pronouncing words in a list or repeating a word or phrase as a group |

| Reading text silently | Often studying use of target word |

| Choral reading | Reading text as a group |

| Reading text aloud | Read words or text aloud, as directed or volunteered |

| Taking notes or writing to dictation | Writing words and meanings or words given by teacher |

| Generative Talk | |

| Answering questions that require thinking | Making inference about meaning of a word in context, suggesting alternative meaning |

| Initiating a new idea, topic, experience | Contributing information about a word or its use |

| Asking simple, on-topic questions | Raising a question about word meaning or use |

| Using text to justify a response | Providing evidence of word meaning from text |

| Writing questions and/or responses to questions | Sometimes completing work sheets or questions about word meaning |

| Reading self-generated text | After writing definitions/sentences, share with group |

| Participating in a discussion | Contributing ideas, responding to others’ ideas |

| Discussing a topic with peers | Sharing experiences, making text-to-self connections |

Notes. The observation system captures the frequency of each teacher discourse move and student response during vocabulary activities. The discourse moves were combined to comprise the two categories of discourse moves that teachers might use to teacher vocabulary activities; Basic Instruction in Word Meanings and Discussion/Elaboration of Meanings. Student responses were combined to comprise two categories of responding; Participating talk and generative talk.

Appendix B

Vocabulary Activity Preceding Text Reading

|

References

- Cunningham, A.E.; Stanovich, K.E. Early reading acquisition and its relation to reading experience and ability 10 years later. Dev. Psychol. 1997, 33, 934–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching Children to Read; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2000.

- RAND Study Group. Reading for Understanding: Toward an R&D Program for Reading Comprehension; RAND: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, S.A.; Fairbanks, M.M. The effects of vocabulary instruction: A model-based meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 1986, 56, 72–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieffer, M.J.; Biancarosa, G.; Mancilla-Martinez, J. Role of morphological awareness in the reading comprehension of Spanish-speaking language minority learners: Exploring partial mediation by vocabulary and reading fluency. Appl. Psycholinguist. 2013, 34, 697–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricketts, J.; Nation, K.; Bishop, D.V. Vocabulary is important for some but not all reading skills. Sci. Stud. Read. 2007, 11, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, N. Size and depth of vocabulary knowledge. Lang. Learn. 2014, 64, 913–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannenbaum, K.R.; Torgesen, J.K.; Wagner, R.K. Relationships between word knowledge and reading comprehension in third-grade children. Sci. Stud. Read. 2006, 10, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T.S.; Cervetti, G.H. A systematic review of research on vocabulary instruction that impacts reading comprehension. Read. Res. Q. 2017, 52, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, B.; Risley, T. Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experiences of Young American Children; Paul H. Brookes: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, D.K.; Tabors, P.O. Beginning Literacy with Language: Young Children Learning at Home and School; Brookes: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Biemiller, A.; Boote, C. An effective method for building meaning vocabulary in primary grades. J. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 98, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupley, W.H.; Nichols, W.D. Vocabulary instruction for the struggling reader. Read. Writ. Q. 2005, 21, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, S.A. Four problems with teaching word meanings (and what to do to make vocabulary an integral part of instruction. In Teaching and Learning Vocabulary: Bringing Research to Practice; Hiebert, E.H., Kamil, M.L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, S. Vocabulary instruction during reading lessons in six classrooms. J. Read. Behav. 1995, 27, 399–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T.S.; Neuman, S.B. Paucity and disparity in kindergarten oral vocabulary instruction. J. Lit. Res. 2014, 46, 330–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hairrell, A.; Rupley, W.; Simmons, D. The state of vocabulary research. Lit. Res. Instr. 2011, 50, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.C.; Freebody, P. Vocabulary Knowledge and Reading; Reading Education Report #11; Center for the Study of Reading: Campaign-Urbana, IL, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, W.E.; Scott, J.A. Vocabulary processes. In Handbook of Reading Research; Kamil, M.L., Mosenthal, P.B., Pearson, P.D., Barr, R., Eds.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000; Volume 3, pp. 269–284. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, S.A.; Nagy, W.E. Teaching Word Meanings; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. The Nation’s Report Card: A First Look: 2013 Mathematics and Reading (NCES 2014–451); NAEP: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Michener, C.J.; Proctor, C.P.; Silverman, R.D. Features of instructional talk predictive of reading comprehension. Read. Writ. 2018, 31, 725–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanzek, J. Building word knowledge: Opportunities for direct vocabulary instruction in general education for students with reading difficulties. Read. Writ. Q. 2014, 30, 139–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, I.L.; McLeown, M.G.; Kucan, L. Bringing Words to Life: Robust Vocabulary Instruction, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, M.F. The Vocabulary Book: Learning and Instruction; International Reading Association: Newark, DE, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hiebert, E.H.; Kamil, M.L. Teaching and Learning Vocabulary: Bringing Research to Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.A.; Jamieson-Noel, D.; Asselin, M. Vocabulary instruction throughout the day in twenty-three Canadian upper elementary classrooms. Elem. Sch. J. 2003, 103, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, C.M.; Spencer, M.; Day, S.L.; Giulani, S.; Ingebrand, S.W.; McLean, L.; Morrison, F.J. Capturing the complexity: Content, type, and amount of instruction and quality of the Classroom Learning Environment synergistically predict third graders’ vocabulary and reading comprehension outcomes. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 106, 762–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlisle, J.F.; Kelcey, B.; Berebitsky, D. Teachers’ support of teachers’ vocabulary learning during literacy instruction in high poverty elementary schools. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2013, 50, 1360–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelcey, B.; Carlisle, J.F. Learning about teachers’ literacy instruction from classroom observations. Read. Res. Q. 2013, 48, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiebert, E.H.; Mesmer, A.E. Upping the ante of text complexity in the common core state standards: Examining the potential impact on young readers. Educ. Res. 2013, 42, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, W. Metalinguistic awareness and the vocabulary comprehension connection. In Vocabulary Acquisition: Implications for Reading Comprehension; Wagner, R.K., Muse, A.E., Tannenbaum, K.R., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 52–77. [Google Scholar]

- Blachowicz, C.; Fisher, P. Teaching vocabulary. In Handbook of Reading Research; Kamil, M., Mosenthal, P., Pearson, P.D., Barr, R., Eds.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000; Volume 3, pp. 503–523. [Google Scholar]

- McKeown, M.G.; Beck, I.L.; Omanson, R.C.; Pople, M.T. Some effects of the nature and frequency of vocabulary instruction on the knowledge and use of words. Read. Res. Q. 1985, 20, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, I.L.; McKeown, M.G. Increasing young low-income children’s oral vocabulary repertoires through rich and focused instruction. Elem. Sch. J. 2007, 107, 251–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, M.D.; McCoach, D.B.; Kapp, S. Vocabulary intervention for kindergarten students: Comparing extended instruction to embedded instruction and incidental exposure. Learn. Disabil. Q. 2007, 30, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, C.M.; Morrison, F.J.; Fishman, B.J.; Crowe, E.C.; Al Otaiba, S.; Schatschneider, C. A longitudinal cluster-randomized controlled study on the accumulating effects of individualized literacy instruction on students’ reading from first through third grade. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 1408–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, C.M.; Morrison, F.J.; Fishman, B.; Ponitz, C.C.; Glasney, S.; Underwood, P.; Schatschneider, C. The ISI classroom observation system: Examining the literacy instruction provided to individual students. Educ. Res. 2009, 38, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, C.M.; Kelcey, B.; Sparapani, N.; Petscher, Y.; Siegal, S.; Adams, L.; Hwang, J.; Carlisle, J. Talking in class? Students’ and their Classmates’ Talking predicts their reading comprehension gains. Manuscript in Preparation.

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).