Abstract

The business model canvas (BMC) is broadly used in entrepreneurship education as a trusted, practical tool for mapping out a company’s business model. Although the BMC helps students to obtain a quick overview of business operations, in practice, entrepreneurs need to adapt and change their business operations constantly in order to grow and remain viable. These changes in a business model are represented by business model innovation (BMI), but frameworks that capture changes in operations are not well developed. Hence, there is a need to present the dynamics of business model innovation through a dynamic business model framework. In this paper, we followed the experiential learning approach and focused on teaching BMI through applying and analyzing BMI in real start-up cases. We applied a two-phase research design by first asking students to apply and analyze the BMI of real start-ups using both the current business model canvas and the proposed dynamic business model framework. Following their analyses, master’s students were administered a survey to assess the benefits of the proposed dynamic business model framework. The results show that the current business model canvas has limitations in capturing the dynamics of BMI, which can be addressed by our proposed dynamic business model framework. The proposed framework can improve students’ level of understanding of BMI and, in particular, its dynamic nature.

1. Introduction

Scholars have highlighted that technology education needs to include more “innovation and entrepreneurship” components, with education programs that anticipate “organizational renewal and new-venture creation” (Clarysse et al., 2009, p. 428). Innovation and entrepreneurship components in education prepare students to find or create jobs in today’s knowledge-based economy. Entrepreneurship education positively impacts engineering education (Ohland et al., 2004; Souitaris et al., 2007). This is particularly true when teaching engineering students, whose technical training does not help them come up with business initiatives (Maresch et al., 2016; Snihur et al., 2021). While entrepreneurship education is loosely connected to learning theories (Kakouris et al., 2023; Kakouris & Morselli, 2020; Neergaard et al., 2012), many studies have highlighted the importance of experiential learning (e.g., Nabi et al., 2017; Neck & Greene, 2011). Experiential learning is a pedagogical approach in which students learn by doing, and it contributes to a positive impact on entrepreneurial intention and to the development of entrepreneurial skills and competences (Motta & Galina, 2023). Moreover, there is a high emphasis on teaching through practice, since this provides greater interaction between students and real-world challenges (Bandera et al., 2018; Bell, 2020; Chang & Rieple, 2013). Scholars have questioned the traditional approach to entrepreneurship education on writing business plans (Leschke, 2013) and argue in favor of focusing more on recursive interaction, which reflects the unique, dynamic process of crafting business models (Demil et al., 2015). When addressing grand challenges, entrepreneurs need to fundamentally rethink how their organizations create (or destroy), deliver, and capture value—that is, their business models (Snihur & Bocken, 2022; Snihur & Markman, 2023). The business model canvas (BMC) (Osterwalder et al., 2010) is well-known as a method of visualizing a firm’s business model, and it has gradually become an essential tool in entrepreneurship education (Verrue, 2014). The BMC has a customer-centric approach that helps entrepreneurs to map the essential resources and partnerships in designing a value proposition. In education, the BMC is used by students to create business propositions for their own start-up ideas or analyze and summarize business models. While the tool is useful for iterating on a solution and designing business models to deliver and capture the value being created, research suggests that the BMC reduces creativity due to its analytic nature and predefined elements (N. Bocken & Snihur, 2020).

Limiting students’ creativity is particularly problematic when teaching students to develop and create business opportunities. Following the lean start-up thinking approach, developing new business opportunities is increasingly seen as an iterative and creative process (Ries, 2011) based on searching for and pivoting ideas in response to new information that is collected through the customer discovery process (Blank, 2013). The search process continues through various stages in the early growth of a start-up (Vohora et al., 2004), and as a result, the business model changes from early opportunity recognition to the later stages of credibility and sustainability (Doganova & Eyquem-Renault, 2009; Schneckenberg et al., 2022). Teaching about the business models of start-ups with tools that merely represent the business logic at a single moment in the growth of a start-up limits what can be learned about the dynamics of new start-ups (Rosenberg et al., 2011; Carter & Carter, 2020; Euchner & Ganguly, 2014; Cosenz, 2015; Toro-Jarrín et al., 2016; Fritscher & Pigneur, 2015). It inhibits students’ analytical approach to making decisions in response to new information gathered through customer discovery processes during various stages of new start-up growth. Hence, teaching about entrepreneurship, and especially about business model development for start-ups, requires more dynamic tools that account for the new information and new insights that students collect during their search processes. Such tools will bring rigor, logic, and realism to students’ thinking and actions (Neck & Corbett, 2018).

Hence, to better teach business model change and adaptation in a classroom setting that resembles the dynamics of business growth in practice, we need a tool that captures business model dynamics. This leads to the core problem we address in our paper: how can educators foster both creative and analytical thinking when teaching business modeling for start-ups?

Business model dynamics are attracting an increasing number of studies from theoretical perspectives (e.g., Foss & Saebi, 2018; Khodaei & Ortt, 2019). After introducing criteria to assess the degree of dynamics in any business model framework, as per Khodaei and Ortt (2019), we asked students to apply and assess the BMC. Next, we asked students to apply and analyze a case through the proposed dynamic business model framework (Kamp et al., 2021; Kharbeet et al., 2024). Through an experiential learning approach, focusing on active learning about BMI, this paper seeks to answer the following questions: (1) How can we teach the dynamics in business model innovation? and (2) Does a dynamic business model framework contribute to the teaching of engineering students to better understand the dynamics of a company’s business model? To address these questions, we investigated existing frameworks that describe a firm’s business model and are used in class settings, and help students to see how they can understand and analyze the dynamics of real start-up business models. We asked a sample of 370 engineering students to work with the frameworks, and we asked them to reflect on the frameworks through a semi-structured survey. First, students were asked to reflect on the business model of the existing start-up using the business model canvas and then critically evaluate and analyze its limitations. Second, they were asked to apply the dynamic business model framework and evaluate the framework based on the dynamic criteria as well as the pedagogical objectives of the course modules on BMI. The results show that the current BMC cannot capture the business model innovation of start-ups. However, engineering students valued the proposed dynamic business model framework by helping them to better understand and apply a business model of start-ups and to understand and reconcile the business model dynamics. Therefore, the study responds to a recent call to examine the effectiveness of current business model frameworks such as the business model canvas (Snihur et al., 2021). Moreover, from an analytical point of view, our research contributes to Greene and Rice’s (2007) and Fayolle’s (2008) call for deeper insight into the evaluation of entrepreneurship education methods by questioning the effectiveness of a new method for introducing entrepreneurship related to “what” we teach, “how” we teach, and “for what” we teach (learning objectives) (Kremer et al., 2017).

A detailed reflection on the business model literature is given in Section 2, and it discusses the criticism of using BMC and foundation for our proposed framework. Next, Section 3 presents the materials and methods used for data collection. Section 4 presents the results, and Section 5 shows the discussion, conclusions, including the implications and limitations of this study, and proposes future lines of research.

2. Theoretical Background

How to teach entrepreneurship in a classroom setting is an ongoing debate among scholars, and at times, it is questioned whether it can be taught or if entrepreneurs are born (Neck & Greene, 2011). The current view is that the necessary entrepreneurial skills and competencies can be acquired. However, consensus exists that traditional class-based teaching is insufficient. This is because entrepreneurship is essentially an experiential activity based on iterative learning and adjustments to new environmental conditions, such as new market information or technological feasibility. A class setting based on creative idea development, practical reflections on new information inputs, and interaction between students who work on real-world cases (Bandera et al., 2018; Bell, 2020; Chang & Rieple, 2013) can stimulate more effective entrepreneurship education (Othman et al., 2012). This learning approach follows experiential learning theory, developed by Kolb (1984). Experiential learning is the process of developing knowledge and new insights that students draw from experiences, reflections, and peer discussions. The challenge remains in how to stimulate creative and analytical thinking through experiential learning using business modeling frameworks in a classroom setting.

2.1. Business Modeling

Among the various aspects of entrepreneurship, education in this field often focuses on ‘entrepreneurship basics’, which include core content such as the entrepreneurial process, innovative business models, lean start-up thinking, entrepreneurial orientation, and entrepreneurial cognition (M. H. Morris & Liguori, 2016). Common across entrepreneurship education is its focus on the search process for business opportunity (Blank, 2013). This process involves searching for the product-market fit and adapting the key operations across the phases of new venture growth—from opportunity recognition to sustainability (Vohora et al., 2004). Hence, because entrepreneurship is not static, entrepreneurship education must remain vigilant by applying frameworks and principles that promote bringing rigor, logic, and realism to students’ thinking and acting (Neck & Corbett, 2018). Describing business operations through a business model has become a popular and practical method for analysis, and has proven effective in creating a more engaging environment for teaching entrepreneurship to students (Kremer et al., 2017). Based on the definitions by Amit and Zott (2001), Johnson et al. (2008), Magretta (2002), M. Morris et al. (2005), Osterwalder et al. (2010), Teece (2010), and Fielt (2014), the business models are visualized through key elements of business operations, providing a simplified but accessible representation of the complexity of business operations. Several attempts have been made to visually describe business operations within a business model. Bouwman and Fielt (2008) introduced a service-based business model that places technology design and innovation at its core. It offers organizations a structured approach for understanding how technological capabilities create and deliver customer value. Building on this, Johnson et al. (2008) proposed an even more streamlined perspective based on a four-dimensional framework, which clarifies how a customer value proposition, profit formula, key processes, and key resources interact to form a cohesive and sustainable business strategy. To bring more logic to the value creation process and to facilitate the analysis of the business operations, Jouison-Laffitte and Verstraete (2008) offered a three-stage visual artifact that maps the generation, remuneration, and sharing of value creation processes. Their model emphasizes not only how value is created and monetized but also how it is distributed among stakeholders, fostering collaboration and long-term sustainability. This view was expanded by Pynnönen et al. (2012), who developed the “Business Mapping Framework” that helps to visualize value streams within complex networks. This was further developed in a six-dimensional template by Abdelkafi et al. (2013), focusing on the value proposition, creation, communication, capture, dissemination, and development. The view on value creation was centralized by Cavalcante (2014) through three core processes of value creation, delivery, and capture. According to Cavalcante, organizations should first define their core processes, then identify the requirements for change, and, finally, tackle the challenges that emerge as a result of these transformations. Among business model frameworks that emerged, the business model canvas (BMC) is a well-known framework that is used by educators to understand the way in which an organization creates, delivers, and captures value (Osterwalder et al., 2014). The BMC has been widely used in entrepreneurship programs, start-ups, and large companies as a user-friendly approach to present a firm’s business model (Blank, 2013).

2.2. Business Model Canvas and Its Criticisms

The BMC developed by Osterwalder and Pigneur (2009) presents how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value from a product or service by proposing nine elements. These elements are customer value proposition, segments, customer relationships, channels, key resources, key activities, partners, costs, and revenues (Osterwalder et al., 2010). The BMC is known as one of the most cited frameworks outlining the critical components responsible for detailing business operations (Ching & Fauvel, 2013). Beyond the confines of being a buzzword, the BMC is considered an effective and reliable visual presentation of the firm’s business performance (DaSilva & Trkman, 2014). The visual presentation helps entrepreneurs to simultaneously consider each business element individually, but also as a whole (Trimi & Berbegal-Mirabent, 2012). Leschke (2013) pointed out that the concept of a BMC is useful for introducing entrepreneurship to non-business students. Although the tool is considered useful for entrepreneurs and students to describe and understand the business operations, various conceptual, practical, and pedagogical concerns remain to bring the rigor, logic, and realism for teaching purposes that Neck and Corbett (2018) have called for in entrepreneurship education

The BMC is a practical tool for describing a firm’s business operations; however, its nine elements suffer from various conceptual problems. The main criticism is that it mixes levels of analysis, such as the value proposition, which is at the user level, and the revenue and cost structure, which are at the firm level, and key partners, which are at the industry level (Ching & Fauvel, 2013). The problem with mixing the levels of analysis can result in conceptual confusion between strategic, tactical, and operational goals. The value proposition and market segmentation are strategic long-term goals, whereas the industry partners are more tactical and medium-term focused, and resources and activities are operational and short-term focused. As such, the BMC does not explicitly address the philosophy of the business operations in terms of a diversification or cost-price strategy (Zott et al., 2011). Furthermore, by placing the customer at the center of the BMC, the model does not account for the wider stakeholder responsibility when formulating the problem-solution (Maurya, 2010). As a result, the business model tends to focus on the financial value created, while neglecting the social and environmental value that can also be created (Ching & Fauvel, 2013; Upward & Jones, 2015; Joyce & Paquin, 2016). In addition, the BMC is short on the role of competition. It has a focus on the advantage of the firm vis-à-vis its competitors, but it does not provide details about the strategic positioning of the firm in view of that competition (Maurya, 2010; Rosenberg et al., 2011; Ching & Fauvel, 2013). Neither is it explicit in terms of the key performance indicators (Maurya, 2010; Rosenberg et al., 2011) or clear business goals (Rosenberg et al., 2011; Ching & Fauvel, 2013) that a firm should prioritize to remain competitive in the market.

In practice, the BMC is conceptually criticized for its limitations in the applicability and suitability in different industry contexts (Paulet & Rowley, 2017; Qiao et al., 2022). These contextual limitations are a result of the BMC as a generic template that has shortcomings across diverse industries, specifically in health industries, where stakeholder groups of patients, insurance organizations, regulators, and healthcare providers are highly interdependent in their operations. Furthermore, the simplified representation of the business operations does not explain well the stage of business development a firm finds itself in and the logic of business operations in a particular stage. The practical limitations of the BMC are increasingly acknowledged in the literature. The BMC is applauded for its ease of use and visual presentation of the business operations. Scholars have also noted the lack of coherence between its elements (Euchner & Ganguly, 2014) and its failure to account for product–service complementarities and complexities (Günzel & Holm, 2013). Within each element of the BMC, specific choices are to be made, for instance, the type of channels used to deliver to customers, or the type of revenue model used, for example, upfront payments or subscription revenue models. These choices often evolve across different stages of a firm’s business development (Vohora et al., 2004). This limits understanding of the logic and coherence between the BMC elements, which are crucial to understand how business model choices are made and, as such, negatively impacts creative thinking (Eppler et al., 2011; N. Bocken & Snihur, 2020; Snihur & Wiklund, 2019). The absence of coherence between the elements makes the BMC too static an approach to understand the real dynamics of new business development (Rosenberg et al., 2011; Carter & Carter, 2020; Euchner & Ganguly, 2014; Cosenz, 2015; Toro-Jarrín et al., 2016; Fritscher & Pigneur, 2015; Khodaei & Ortt, 2019).

These criticisms should be taken very seriously, especially when designing education curricula in which students are asked to create, reflect, and analyze business operations. A simplification of reality through generic templates can help students to grasp and understand business operations, and the visualization in particular invites students to work with them. However, the static representation of the business operations and overlooking the coherence between business elements, or the lack of detail, which may vary when start-ups need to respond to new insights, limits the usefulness of the BMC in a class setting. More rigor, logic, and realism are needed in frameworks for business modeling to address the pedagogical requirements for student thinking and acting that Neck and Corbett (2018) referred to. The customer discovery process that underlies business modeling (Blank, 2013) is an experiential search for information about technology, customers, competitors, and market dynamics to validate assumptions and may require pivoting the business model according to new insights. Ensuring that students think in terms of business model adaptation to new information requires tools that stimulate students to question the logic of their business model and adapt it to new insight. This resembles the act of start-up companies that develop and introduce high-tech products in the market and have to cope with a dynamic, mainly turbulent, internal and external company environment. The business models of start-ups are constantly changing and adapting to cope with new insights about the business environment. In order to trace the origins of business model innovation and track effects, students require business model frameworks that capture the business dynamics (Schneider & Spieth, 2013).

2.3. Business Model Dynamics

The business model dynamics literature has gained significant interest over the last decade (Saebi et al., 2016) and resulted in concepts such as business model innovation (Amit & Zott, 2012), business model adaptation (Saebi et al., 2016), business model renewal (Khanagha et al., 2014), and business model evolution (Demil & Lecocq, 2010). Foss and Saebi (2017, p. 201) define business model innovation as “designed, novel, nontrivial changes to the key elements of a firm’s business model and/or the architecture linking these elements”. Demil and Lecocq (2010, p. 239) define business model evolution as a “fine-tuning process involving voluntary and emergent changes, in and between permanently linked core components” in response to both external and internal factors. According to the extant body of literature, business model dynamics refer to “how business models come into being (…) and the changes in the architecture between business model elements that produce alterations to the business model” (Foss & Saebi, 2018), as well as “shaping, adapting, and renewing the underlying business model of the company” for sustained value creation (Achtenhagen et al., 2013).

The need for a dynamic view of business activities is rooted in the need to adapt business operations to changes in the competitive landscape (Teece, 2010). As such, the business model is not a description of the business logic, but a reflection of the development and change processes taking place over time (Schneckenberg et al., 2022), within both established firms and new ventures (Doganova & Eyquem-Renault, 2009). By taking a dynamic approach to business modeling, the concept can help evaluate and validate future value creation and provide insights into capturing that value (Doganova & Eyquem-Renault, 2009).

2.4. Criteria for a Dynamic Business Model Framework

Combining insights from the literature on the current business model framework (e.g., BMC) and business model dynamics led previous research to develop a comprehensive dynamic business model framework. Khodaei and Ortt (2019) established a robust framework for evaluating the degree of dynamism in business models. It is based on four critical criteria. The first criterion refers to the completeness of business model aspects. It examines both internal company factors—such as resources, processes, and value propositions—and external environmental factors, including market conditions, regulatory influences, and competitive landscapes. The second criterion focuses on the interrelationships between business model aspects. This involves evaluating how different components—such as value creation, delivery, and capture—interact and align with one another. The coherence among these aspects is a key indicator of business model quality, as it reflects the model’s internal consistency and operational efficiency. The third criterion extends this analysis to interrelationships over time. Here, the emphasis lies on the need to understand how business model components evolve and influence each other as environmental conditions change. Finally, the fourth criterion addresses how the business model framework captures changes over time and across different contexts. A framework to analyze business models is useful when it remains simple, relevant, and adaptable in diverse and shifting environments. By applying these criteria, organizations can systematically analyze the dynamics of their business models, ensuring they are not only well-structured and coherent but also resilient and responsive to evolving challenges and opportunities. Table 1 presents a summary of the business model dynamics criteria.

Table 1.

Dynamic business model framework criteria (source: Khodaei & Ortt, 2019).

The aim of the dynamic business model framework is to capture business model dynamics in a comprehensive framework. Such a framework should reflect on the previous dynamic criteria, such as capturing various origins of changes as well as various types of changes in business model elements, in order to keep business model consistency. Kamp et al. (2021) present a dynamic business model framework following previous dynamic business model criteria by Khodaei and Ortt (2019).

BMI is based on four components: value proposition (VP), value creation (VCR), value capture (VCA), and value delivery (VD), as proposed by N. M. P. Bocken et al. (2018). In the frameworks proposed by Kamp et al. (2021) and Kharbeet et al. (2024), different types of business model changes are distinguished. A first distinction refers to the origin of change (either internal or external to the start-up). A second distinction refers to the order of changes. An initial change in the first BM is the ‘primary change’. All the following changes are called ‘secondary changes.’ A third distinction explores whether changes are strategic moves by the start-up or forced upon the start-up. This distinction is made because it can show the degree of freedom that an entrepreneur or manager has.

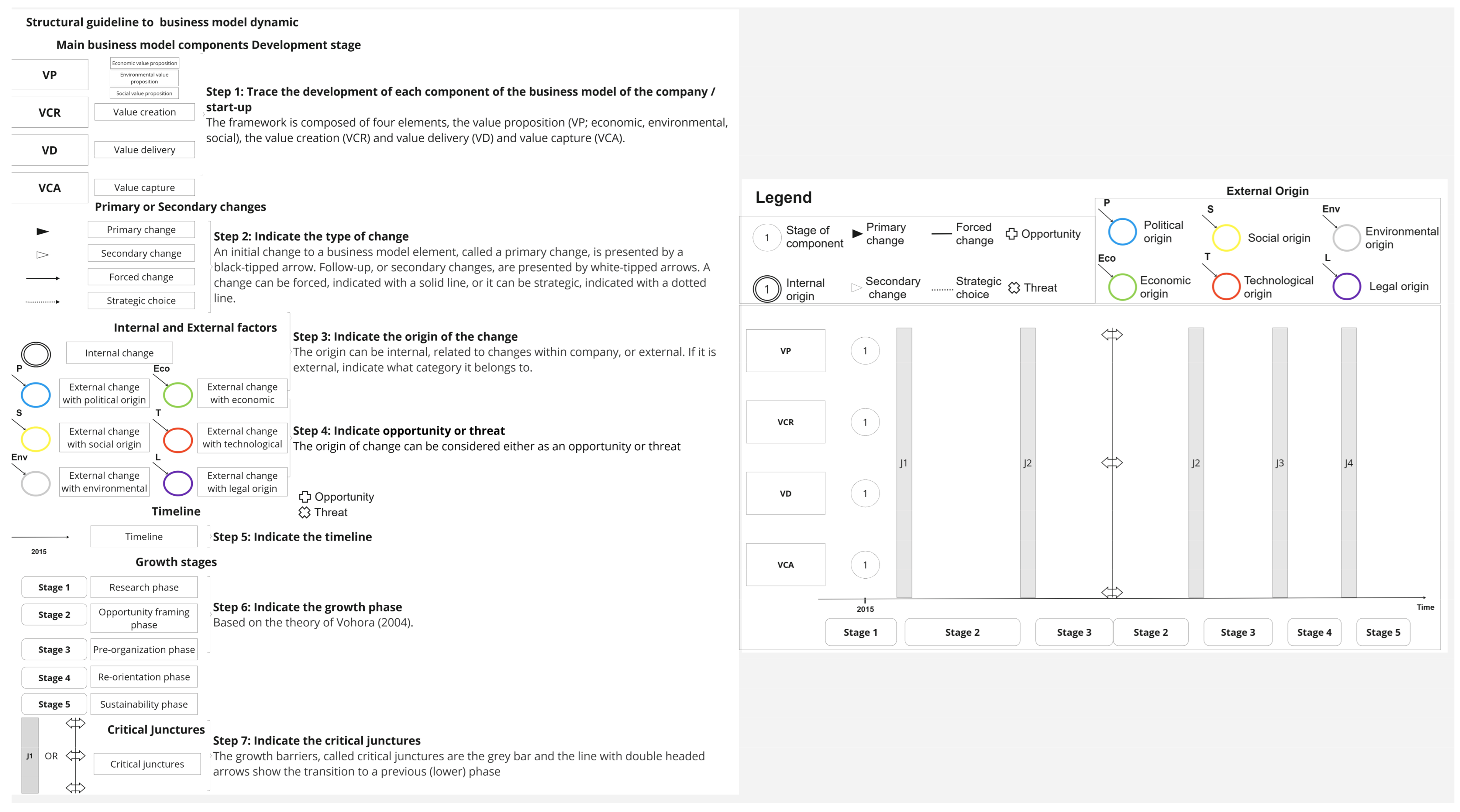

Following these reflections, this study builds on the following nine criteria to include the dynamics in a business model framework.

- The business model is subdivided into four main components: value proposition, value creation, value delivery, and value capture.

- There are different factors affecting the business model, which can lie inside or outside the company.

- The origin of change can be considered either as an opportunity or a threat.

- The initial change in the business model refers to one particular business model element.

- Business model consistency typically requires follow-up changes in one or more of the other business model elements.

- The initial changes are called primary changes, and the possible follow-up changes are called secondary changes.

- Business model changes can be either forced changes or strategic choices.

- The timeline of the growth stages of the start-ups is included in the framework.

- Critical junctures are identified in the framework.

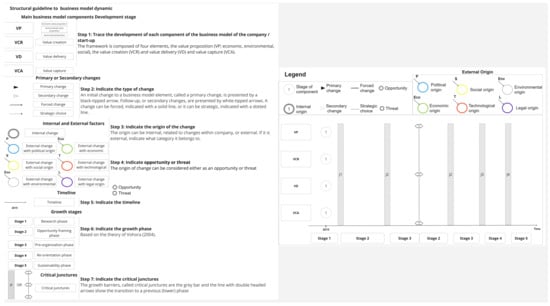

The nine criteria are included in the dynamic business model framework (see Figure 1). The framework uses growth stages and critical junctures to reflect the time element of business development. When the elements of a business model change due to force, this is represented by an arrow with a solid line. When it involves a strategic choice, it is shown with a dashed arrow. Change can originate from internal operations or from external sources. The origin of change is represented graphically with a double-lined circle, showing that change has an internal origin, while a circle with a small arrow attached to it shows that change has an external origin. Further, these factors are classified as posing a threat or providing an opportunity. Changes can be categorized as either primary—represented by a black-tipped arrow—or secondary—represented by a white-tipped arrow. Figure 1 presents a simplified visualization of how the business model evolves over the stages of start-up growth. The framework includes four components: value proposition (VP), value creation (VCR), value delivery (VD), and value capture (VCA), and it shows how a change in one component can lead to a change in another component. The stages of growth are based on Vohora et al. (2004): (1) Research; (2) Opportunity Framing; (3) Pre-organization; (4) Reorientation; and (5) Sustainable Returns. The stages are based on the stage-gate model approach, in which moments of relative stability are represented by the stages, while periods of turmoil—when the firm’s business operations drastically change—are represented by the critical junctures. Following Vohora et al. (2004), the framework identifies these junctures as (J1) opportunity recognition; (J2) entrepreneurial commitment; (J3) credibility; and (J4) sustainability. The framework visually illustrates how one change can trigger subsequent changes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The dynamic business model framework (structural guideline) (Vohora et al., 2004).

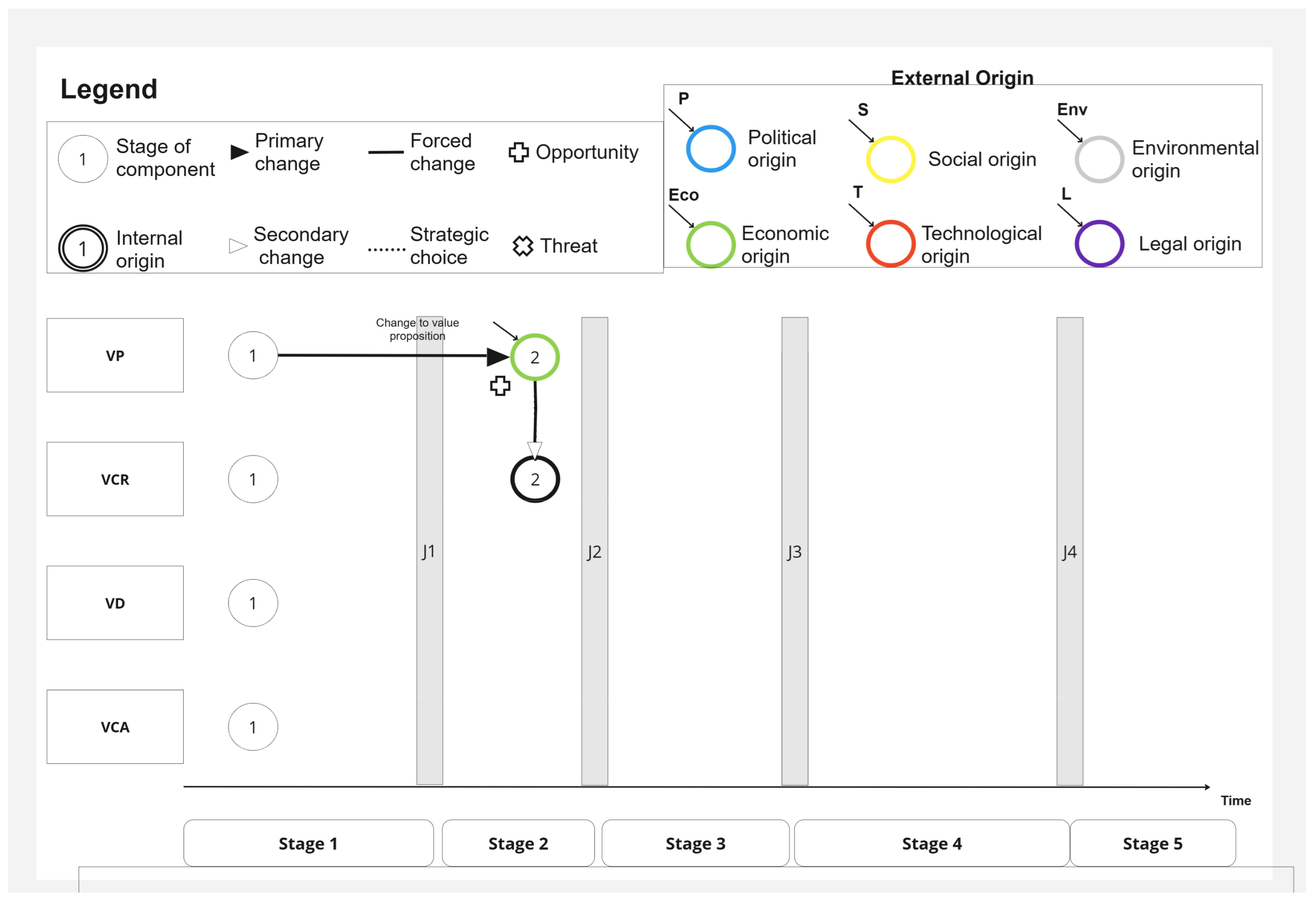

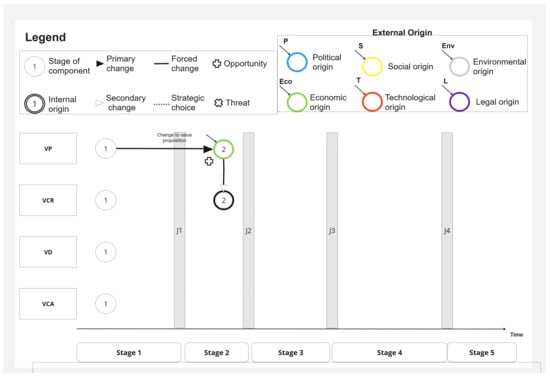

In Figure 2, a simplified example is shown: a modification in the value proposition (originating externally and recognized as an opportunity) results in a change in the value creation. The arrows in Figure 2 denote that these changes are solid, indicating that they signify forced changes. Therefore, following the initial forced changes in the value proposition (VP), the value creation (VCR) is forced to change as well. This dynamic can be seen in many start-ups where distinct value propositions are associated with different partners. For example, increasing complexity in photovoltaic (PV) projects has resulted in greater collaboration among network actors. This reflects a change in the value proposition that necessitates the involvement of new partners. In this case, both the initial change and the subsequent response are externally driven. The value proposition is compelled to evolve due to growing project complexity arising from customer needs, while the value creation is correspondingly forced to adapt in order to preserve coherence within the business model.

Figure 2.

The dynamic business model framework (simple version): example—value proposition (VP) change with external origin leading to forced value creation (VCR) change.

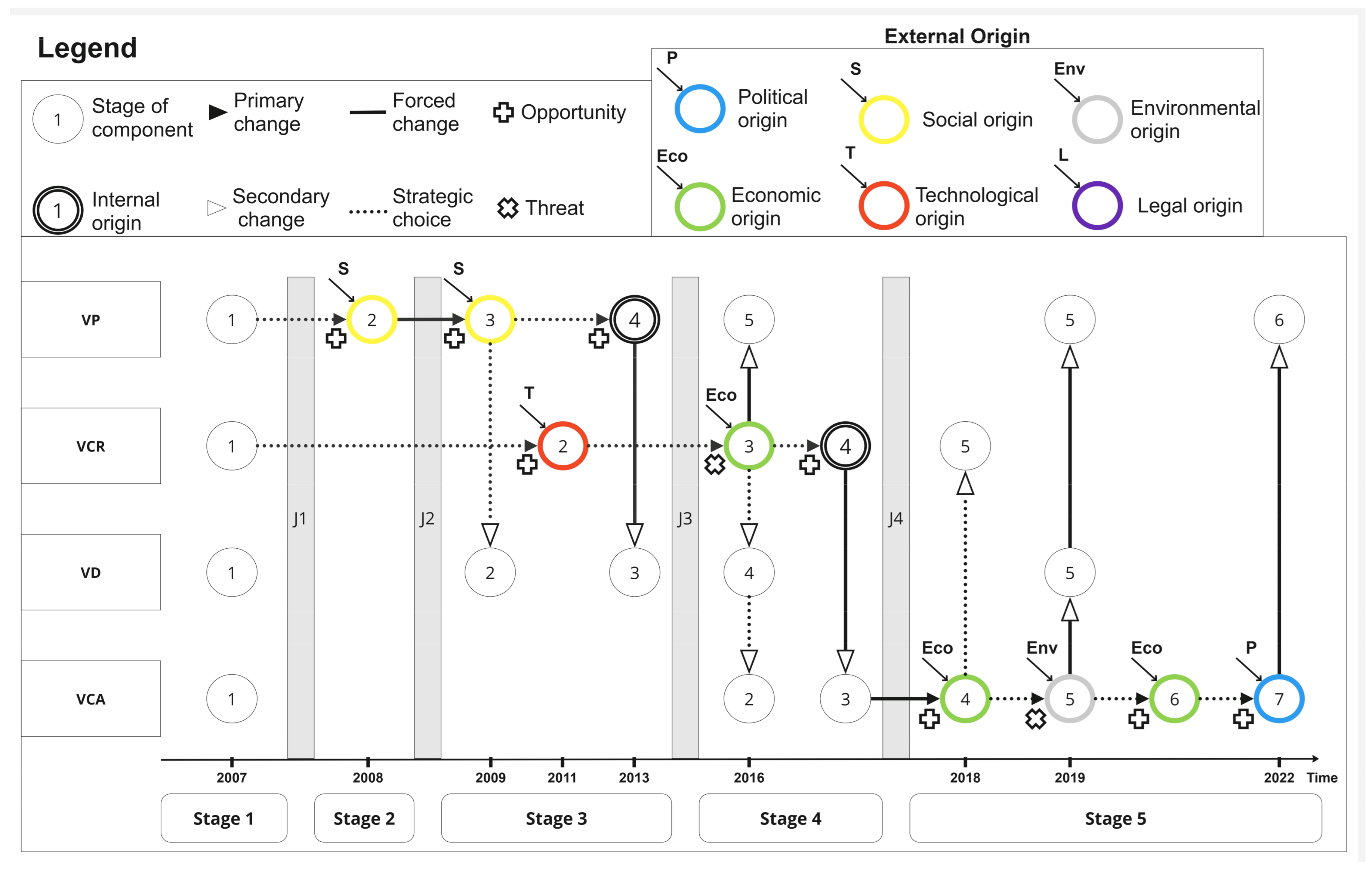

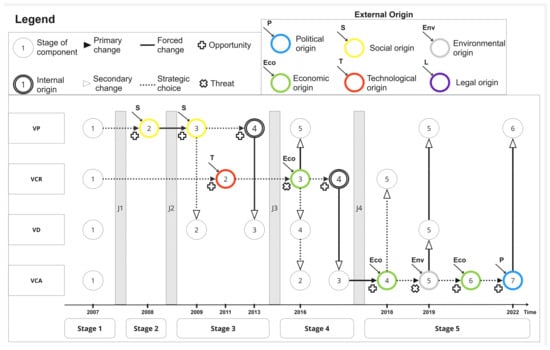

Figure 3 illustrates the complete version of the business model dynamics, follow-up changes triggered by external and internal factors during the development process of a start-up (SW). SW is a market leader in Africa’s off-grid solar sector, offering systems ranging from small phone-charging kits to larger solutions for SMEs. The company originated from a solar lamp designed by a Delft University of Technology student. He tailored the idea based on market research and customer preferences in that area. This led to the initial design (VP1 to VP2). His user research led to a power box able to charge phones and power lamps (VP2 to VP3). Founded in 2009, SW began selling through retailers and wholesalers (VD1 to VD2). In 2011, SW moved its HQ and R&D to YES!Delft, enabling tech advancements like weather-predictive battery systems (VCR1 to VCR2). As product offerings expanded (VP3 to VP4), market competition increased. Recognizing they could not compete on price, SW shifted its strategy. In 2015, SW partnered with Persistent Energy Capital and launched a new model: focusing only on larger household systems (VP4 to VP5), selling directly to end-users (VD2 to VD3), and introducing a pay-as-you-go model (VCA1 to VCA2). In 2016, SW opened an office and hired commission-based agents (VCR3 to VCR4, VC 2 to VCA3), followed by $2M in funding and expansion into other countries (VCA3 to VCA4, VCR4 to VCR5). However, the pay-as-you-go model proved fragile during crises like COVID-19, prompting a partial return to direct payments (VCA4 to VCA5). To serve SMEs, healthcare clinics, and weak-grid areas, SW began offering larger systems (VP5 to VP6, VD3 to VD4). In 2022, new investments ($4M + $2M) supported South African expansion (VCA5 to VCA6). Later that year, subsidies made smaller systems viable again, enabling SW to reintroduce them and broaden its product range (VP6 to VP7, VCA6 to VCA7).

Figure 3.

Dynamic business model framework (complete version): example-business model dynamics during the development process of a start-up (the case of technology-based start-up).

3. Research Design

To elaborate on the theory about how to teach BMI to engineering students to understand and be able to analyze the dynamics of new start-up development, we assess the existing BMC and the proposed dynamic business model framework. The design of the study followed a structured approach through which students who participated in an entrepreneurship course at the Delft University of Technology applied various tools to understand, analyze, and reflect upon the changes in the business model of existing start-ups. In our research design, we followed the experiential learning approach, as proposed by (Kolb, 1984), in several steps. The first step was Concrete Experience, and the learning goal for students was to investigate an unfamiliar task for them, which involved investigating and describing the business model through BMC of a start-up during specific stages of its early growth. We instructed the students about the theories and tools of BMI and BMC, and trained them to conduct desk research and interviews with founders to collect data on start-ups and to gain practical experience with the tools. This helped students develop skills in data collection through desk research, observation, and interview techniques. They also gain experience in using the tool from the moment of identifying the value proposition up to the moment of launching the business and scaling the start-up’s activities. During each of the growth stages, the students were asked to describe the target customer, the value proposition, the resources and partnerships, the channels used to reach customers, and how the start-up captured the value through the revenue model.

The second step was Reflective Observation, and the learning goal was for students to critically reflect on how the business model evolved the BMC. In this step, students were asked to identify the patterns of development and the changes in the business model from one stage to another. The task was to analyze the changes that happened in the business model and to provide reasoning for the changes that were made. We also asked students to discuss the findings and whether the findings challenged their understanding of the business development. This helped us to gather feedback to identify key limitations of the BMC. Students were asked if the BMC in one stage was helpful to explain what happened to the business model in subsequent stages of start-up growth.

The third step was Abstract Conceptualization. After reflecting on existing criticisms of the BMC, students were introduced to the proposed dynamic business model framework. The learning goal was to synthesize the insights they gained from connecting changes in the business models from one stage of growth to the other stage of growth and thereby identify the dynamics of the start-up’s business model. This step was critical to relate the findings to the start-up growth model and to envision the requirements for such a dynamic tool.

Fourth, the Active Experimentation step: We then instructed the students to apply a proposed dynamic business model framework to the growth stages of the start-up they had analyzed before. In this step, the goal was to evaluate the new framework in view of the changes in the start-up’s business model that students identified in the previous steps. We specifically asked students how they could explain and rationalize the changes in the business model. Based on this dynamic business model framework, students proposed suggestions to the start-up founders for future business model changes based on possible external factors they identified, and that might lead to business model changes. Through this cycle, students can put theory and reflections into practice (Farber et al., 2015; Motta & Galina, 2023).

Finally, the course assessment was based on the extent to which students were able to apply the theoretical models to describe and analyze the business model of the start-up. The course has been taught repeatedly over the last five years in every quarter at the master’s level.

3.1. Data Collection

Our data sample relies on four student cohorts during four quarters of education at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. Each quarter consisted of 10 weeks of education and accumulated up to a total of about 100 teaching hours, and was delivered between 2020 and 2023 to 370 students. The groups of students were instructed in each quarter with the same course, same staff, and same written and oral material based on student projects and presentations during the course. During the course, students were asked to provide written evaluations of the tools and oral feedback submitted in a digital education support system. These evaluations were used to assess the usefulness of the proposed tool for capturing the dynamic business model of a start-up. Data were collected through questionnaires, which were administered to students in their last week of the course.

3.2. Data Analysis

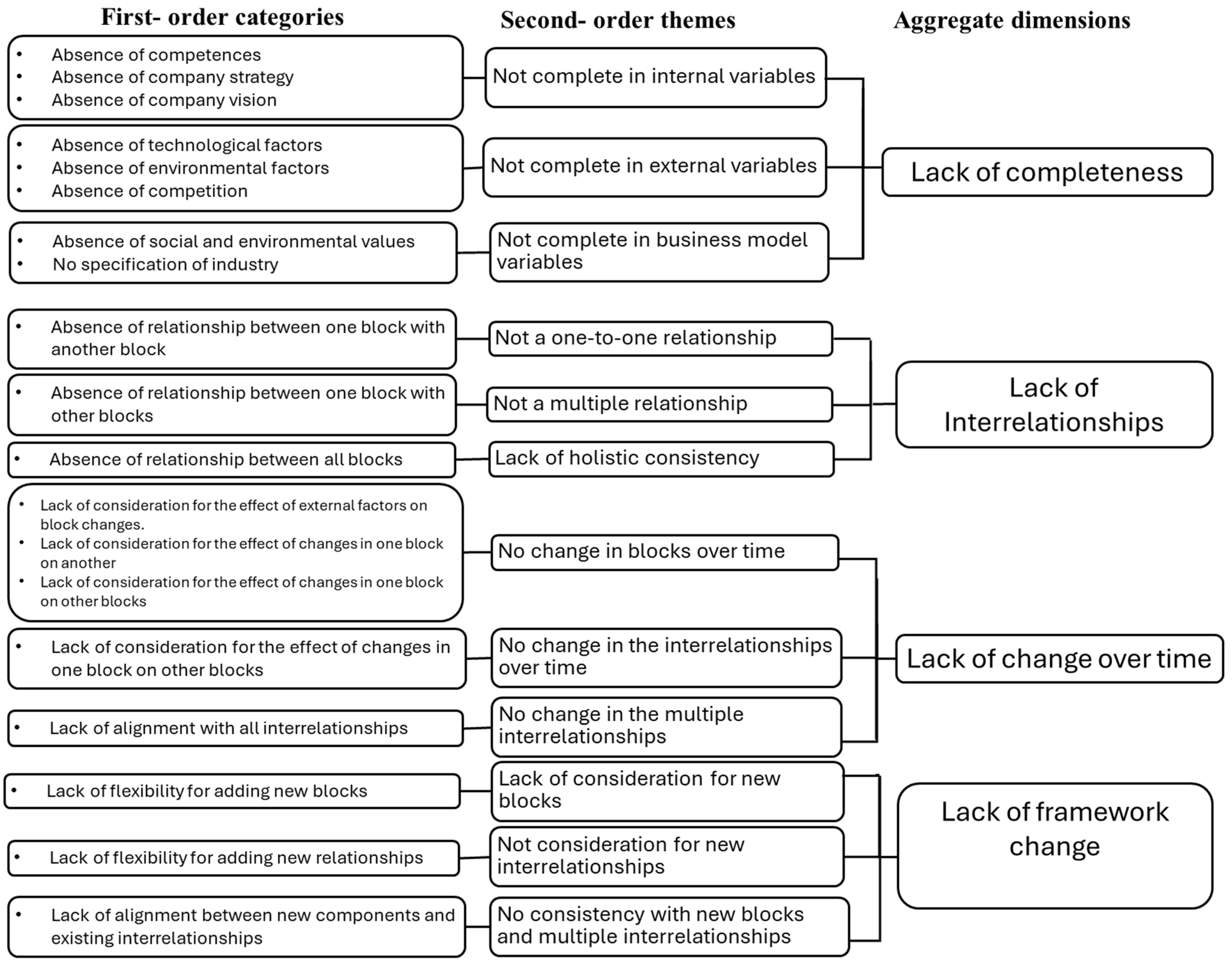

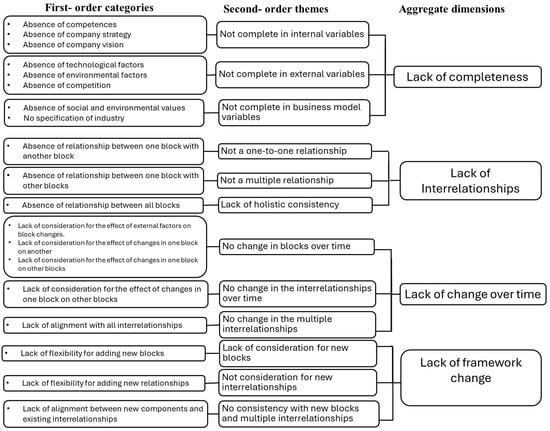

3.2.1. Evaluating the Current Business Model Canvas

The first part of our study was explorative in nature. We qualitatively investigated the students’ projects and presentations they submitted to develop the initial coding based on case analyses for each of the four student cohorts. Each author had the role here to develop the initial coding of two cohorts independently and then review the initial coding performed by the other author. In total, we cross-coded four datasets, each a cohort of students, and each author independently applied open coding to identify emergent themes. The differences were discussed by the two authors to increase the validity and reliability of the initial coding process. The results were compiled through cross-coding of the four data sets, in a large set of data-based “open codes” (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). These codes were then discussed between the authors and used to perform a thematic analysis on the instructor’s course notes, student feedback, and course evaluations, and several open questions regarding criticisms of BMC. For example, we asked, “What are the criticisms to the BMC?” The results of the initial coding process yielded 19 categories. The next step was to identify the underlying meanings and relationships between codes and different levels of themes (Braun & Clarke, 2006). This resulted in 12 second-order themes that provided the relationships between the codes. Finally, we grouped the themes into four aggregate themes (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Gioia et al., 2013). To clarify how this process was carried out, we illustrate one example from our coding structure. A student recalled that “the interrelations between the different boxes are not there, for example it’s not clear how key activities can be accomplished by different partners.” This quotation was first coded as ‘the absence of a relationship between one block and another block ‘ (first-order code). Through iterative comparison, it was grouped with related codes to ‘not a one-to-one relationship’(second-order theme). This theme, along with the other second-order themes, such as ‘not a multiple relationship’ and ‘lack of holistic consistency’, contributed to the aggregate theme ‘lack of Interrelationships’. Similar procedures were applied across all interviews, ensuring that first-order codes were grounded in respondents’ terms, while second-order themes and aggregate dimensions were abstracted to a more conceptual level (Gioia et al., 2013). Finally, the coding and categorization process was reviewed by the two authors with expertise in qualitative methods to ensure clarity, consistency, and conceptual accuracy. Thus, the reliability and credibility of the results were ensured through an investigator process involving peer evaluation and cross-checking of the coding process by (Archibald et al., 2015). Based on the themes and dimensions identified, the proposed dynamic business model framework was developed.

3.2.2. Evaluation of Proposed Business Model Dynamic Framework

For the second part of the study, we proposed that students use the dynamic business model framework. This framework builds on the model developed by Kamp et al. (2021) and Kharbeet et al. (2024), and incorporates the dynamic criteria outlined by Khodaei and Ortt (2019). We asked students to apply and illustrate the dynamics of the business models using the example of technology-based start-ups. To facilitate this, students worked with a template provided on the Miro online platform. This software allows real-time communication in the classroom with a basic set of features to improve the experience of collaborative work and provide a group discussion on the Miro board. The possibility of sharing and simultaneous joint editing of text documents, or calculation spreadsheets, was considered a valuable asset of online collaboration work, as well as steps and instructions (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Example of students’ work at Miro: https://miro.com/app/board/uXjVKBwJQlM=/, accessed on 21 January 2026.

4. Result

4.1. Business Model Canvas Limitations from Thematic Analysis

The first part presents findings from a thematic analysis of open-ended questions regarding criticisms of the BMC. The results show that the criticisms can be classified into four categories: a lack of completeness, a lack of interrelationship, a lack of change over time, and a lack of framework change. Figure 5 depicts the coding structure and presents supporting evidence.

Figure 5.

Coding structure for BMC critics.

4.1.1. Lack of Completeness

The results indicate that lack of completeness is linked to the three areas: internal and external variables, and business model components. External variables referred to the absence of technological factors, environmental factors, and the absence of competitors. Internal variables included missing elements such as organizational competencies, company vision, and strategic direction.

Many students highlighted the role of technological factors in shaping the business model. One student remarked: “External factors which influence the business model are not shown, like for example technology development”.

Students also noted the absence of environmental and social values, as well as specific-sector consideration that make the business model complete in elements. The absence of environmental and social values was mentioned by many students. For instance, one student stated: “It does not take into account any sustainability and social values. This means that sustainable development goals are not taken into account, when they should be”.

Students further indicated that the model lacked adaptability to complex industry contexts such as healthcare. As someone pointed out: “The customers in health care segment are diverse, so the value proposition for each customer is different, however these differences are not represented.” And another claimed: “Leaves out key elements in healthcare for example in medical industry it does not distinguish the user from the customer.”

4.1.2. Lack of Interrelationship

The capability to identify and assess the interrelationships between variables is another key criterion for capturing business model dynamics. Distinguishing between environmental variables and business model variables reflects a categorization that implies interconnections between them. The findings show that there are three types of relationships: one-to-one relationships, multiple relationships and a holistic or consistent view of all the blocks. As one student pointed out: “the interrelations between the different boxes are not there, for example it’s not clear how key activities can be accomplished by different partners”.

4.1.3. Lack of Change over Time

The ability to adapt and modify interrelationships over time is another key criterion for dynamics. Understanding cause-and-effect relationships is essential for capturing these dynamics effectively.

Based on the data analysis, three aspects of change were identified: change within the blocks, changes in interrelationships, and holistic change over time, which contributes to overall model consistency.

Regarding changes within blocks, the findings point to the effect of external factors on block change, change in one block with the other block, and change in one block with all the blocks. Among these elements, the effect of external factors on the relationship was mentioned. One student remarked that it is not explained how new technologies would affect new value proposition(s).

This indicates not only an external factor but also that a change in one block can lead to changes in other blocks and create new interrelationships within the business model. This was pointed out by one student as “changing the value creation will lead to change in new revenue model, or new revenue models can only be possible by changing the new value proposition”, and by another student as “how new value proposition(s) can attract more customers”. Another student mentioned: “It does not cover how the company has evolved in terms of different customer segments and it does not show the development.”

4.1.4. Lack of Framework Change

The business model framework change is another key criterion for the degree of dynamics. Models are simplifications that hold in specific conditions or when specific assumptions are met. Changes in the model can refer to aspects or interrelationships in the model. One student pointed out that “the framework is not flexible enough for adding new blocks or relationships”. And another student pointed out that “the current framework does not give the complete picture as it does not visualize strategic changes over time.”

4.2. Business Model Dynamic Framework, Student Assessment

Next, we introduced and evaluated the proposed business model dynamic framework (Kamp et al., 2021; Kharbeet et al., 2024). Students were asked to apply and evaluate the proposed business model dynamic using Likert scales as well as open questions. They evaluated the framework based on the dynamic framework criteria of completeness, interrelationship, interrelationship over time, and framework changes. The dynamic aspects are particularly well evaluated for the proposed business model dynamic framework by the students on all the items, with the interrelationship criterion receiving the highest scores. As one student claimed: “The business model dynamics include all the essential components of a business model meeting the completeness criteria. It captures the connections between different blocks in the business model and also the interactions over time. It is also possible to accommodate changes or new findings in the business model”. Another student pointed out that “ business model dynamic framework makes sure that all relevant aspects of business model are considered while focusing on keeping consistency within different elements of business model”.

Next, the students were asked to assess the pedagogical objectives of the course modules on learning business model innovation (Table 2). The highest means corresponds to the second item of learning objectives with “help me better illustrate and communicating the business model dynamics of the company”. As one student claimed: “The framework highlights the interdependencies between different elements of the business model and helps identify and analyze feedback loops, ensuring coherent and aligned changes across the model”.

Table 2.

The evaluation criteria for business model dynamic framework.

We also asked students to evaluate the business model dynamic framework using a template in the Miro board to assess how satisfied the students were with using the application.

A large majority of students appreciated the structure and simplicity of the framework’s design. Interestingly, they did not rank the user-friendliness aspects highly. Specifically, the interaction between team members and teamwork were areas they felt could be improved.

One student noted: “the Business model dynamics framework in Miro provides a comprehensive and holistic approach to understanding and visualizing various elements of a business model dynamics. It facilitates the identification and representation of interrelationships among different components of the business model that allows for a better understanding of how changes in one element can impact others”.

The framework in Miro enabled easy and flexible changes to the business model, supporting its dynamic nature and allowing users to effectively capture and visualize framework changes.

A student mentioned: “The Business Model Dynamics framework, used in tools like Miro, helps analyze and visualize the changes and evolution of a business model over time. It incorporates a temporal perspective by allowing users to map the timeline and iterations of the business model, capturing its dynamics at different stages.”

Overall, the findings indicate that students found the new business model dynamic framework valuable, as it effectively captured all key dynamic criteria. They also appreciated the interactive features of the Miro board, which enhanced the framework’s usability by clearly presenting its structure and design.

5. Discussion

There is a broad consensus in the scholarly literature that entrepreneurial education can increase the individual’s desire and ability to grow and adapt their knowledge and skills in order to better handle non-routine tasks and continuous change (Arpiainen & Kurczewska, 2017; Neck & Corbett, 2018). Researchers have criticized the traditional approach of entrepreneurship education, which emphasizes writing business plans (Leschke, 2013), and argued that it should instead focus on recursive interaction, reflecting the unique process of crafting business models known as BMI (Teece, 2010). In this vein, the paper contributes to the extant literature by emphasizing the importance of business model dynamics (e.g., Demil & Lecocq, 2010; Teece, 2010; Saebi et al., 2016), and in particular, to the development of a comprehensive business model dynamic framework (Khodaei & Ortt, 2019; Kamp et al., 2021; Kharbeet et al., 2024). Our study makes several theoretical contributions to the existing body of literature on business model innovation and entrepreneurship education. Specifically, it builds on the research stream related to teaching entrepreneurship through experiential learning (Nabi et al., 2017; Neck & Greene, 2011; Politis, 2005; Rae & Carswell, 2001; Wilson, 2008; Motta & Galina, 2023). We follow Farber et al.’s (2015) experiential learning cycle with a focus on experiential activities in terms of the development of projects and activities (Bell, 2020).

Business model innovation is considered an important aspect of business operations and is thus an emerging perspective in entrepreneurship education. This is specifically relevant when introducing entrepreneurship education to non-business students (e.g., Leschke, 2013). However, teaching business model innovation requires understanding and responding to the continuous changes in business operations in order to cope with environmental dynamism and turbulence. In line with previous studies on entrepreneurship education for engineering students, particularly those focused on teaching business model innovation, it is emphasized to further develop the usefulness of current business model frameworks (Snihur et al., 2021). This study contributes to the literature by critically assessing the current business model canvas (BMC), a well-known business model framework, and highlights the challenges of applying it in a dynamic and turbulent business environment. These criteria address, among others, the absence of competition (Maurya, 2010; Rosenberg et al., 2011; Ching & Fauvel, 2013) and the lack of a company vision and strategy (Rosenberg et al., 2011; Ching & Fauvel, 2013). Current business model frameworks have also been criticized for failing to unravel the cause-and-effect relationships (Baden-Fuller & Haefliger, 2013) among the business model elements and for reflecting the interdependent activities across the elements and the firm boundaries (Zott & Amit, 2010). This aligns with Euchner and Ganguly’s (2014) argument that the BMC does not represent well the coherence or relationships among its elements.

Researchers have pointed out that the static nature of the business model frameworks cannot capture the dynamics of a firm’s business operations (Rosenberg et al., 2011; Carter & Carter, 2020; Euchner & Ganguly, 2014; Cosenz, 2015; Toro-Jarrín et al., 2016; Fritscher & Pigneur, 2015). Building on criteria from the previous business model dynamic framework (Khodaei & Ortt, 2019), the proposed framework advances existing theories of business model evolution by analyzing the origin of change and subsequent changes in business model elements throughout a company development process to keep the business model consistent.

This also highlights the importance of business model consistency (e.g., Baden-Fuller & Morgan, 2010; Casadesus & Ricart, 2011; Giesen et al., 2010; M. Morris et al., 2005; Teece, 2010; Kranich & Wald, 2018). BM consistency has been called “the most powerful and neglected aspect of BMs” (Casadesus & Ricart, 2011, p. 104). It refers to a state of internal alignment in which all elements of a business model are in agreement with each other (Giesen et al., 2010).

Finally, Knowledge of variables that affect each other over time (without being able to distinguish cause and effect) enables the explanation of more complex dynamics (Khodaei & Ortt, 2019). This also aligns with the discussion of the adaptive business model, which refers to the process by which management actively aligns the firm’s business model in response to a changing environment, such as shifts in customers’ preferences, supplier bargaining power, technological changes, and competition (Saebi et al., 2016). The business model framework must highlight different aspects or relationships when the assumptions no longer hold (Khodaei & Ortt, 2019). Khodaei and Ortt (2019) propose that the highest degree of dynamics may even require changes to the framework itself. Business model innovation affects the business model as a whole and holds the potential to disrupt established industries (Foss & Saebi, 2018). This aligns with the definition of business model innovation as “the discovery of a fundamentally different business model in an existing business” (Markides, 2006, p. 20).

We encouraged students to apply the proposed business model dynamic framework to foster student engagement through learning by doing and reflection (Pittaway & Thorpe, 2012). Next, students evaluated the framework by Kamp et al. (2021), using both the dynamic criteria and the pedagogical objectives of the course modules on business model innovation. The results show that, from a pedagogical standpoint, the proposed framework helps students to understand, apply, and illustrate the business model innovation of companies and how business models evolve over time. Being able to perform such an analysis using a dynamic framework provides them with a better understanding of which aspects to consider when analyzing business model dynamics and how those elements influence one another. The two phases are linked into a mutually reinforcing relationship that enables student learning of business model innovation applicable to the technological innovations of the technology-based start-ups. Indeed, questioning the effectiveness of a new method for introducing entrepreneurship is directly related to “what” we teach (the business model dynamic framework), “how” we teach (experience-based learning using a Miro board that fosters collaboration), and “for what” we teach (learning objectives) (Kremer et al., 2017). By analyzing these new approaches to teaching business model innovation, we contribute to the previous studies on “what” we teach, “how” we teach, and new approaches in entrepreneurship education (Greene & Rice, 2007; Fayolle, 2008).

To bridge the gap between theory and practice, research underscores the importance of curricular activities that adopt a hands-on, interactive approach (Bandera et al., 2018; Bell, 2020; Chang & Rieple, 2013). By engaging directly with real-world challenges, students gain exposure to innovative business models through partnerships with companies. In these collaborations, student teams tackle actual problems by designing and executing projects that address genuine needs, allowing them to apply classroom concepts in practical, meaningful ways. This experiential learning not only reinforces academic knowledge but also demystifies entrepreneurship. A study by Tete et al. (2014) reveals that such activities provide students with a clearer and more realistic understanding of the entrepreneurial journey—its challenges, opportunities, and day-to-day realities. Working alongside entrepreneurs immerses students in authentic business environments, offering invaluable firsthand experience.

6. Implication for Technology Entrepreneurship Education

Our findings provide practical guidance for the development of entrepreneurship courses among engineering students with a focus on teaching business model innovation. Teaching technology entrepreneurship is an emerging theme, but has received little attention so far (Nelson & Monsen, 2014; Giones & Brem, 2017). We contribute to this stream of research on teaching engineering students about entrepreneurship by suggesting a dynamic framework to assess the business operations of technology-based start-ups. The use of a tool to assess the dynamics in business modeling will help students to critically assess the current business operations of technology-based start-ups and understand that the business model architecture is a result of the dynamic nature of the environment in which technology-based start-ups operate. We propose that students who work in teams on business development can benefit from working with online templates of dynamic business model frameworks and designing the business model at different stages of growth. The interactive framework stimulates active learning in teams and increases student engagement through hands-on participation. It triggers them to discuss the changes in business modeling and develop better insights through critical thinking. In particular, in a tech-savvy environment, as is the case with engineering students, this helps to adopt a more creative and design thinking approach to study and learn about opportunity recognition and subsequent business model development. Hence, the dynamic business model framework is useful for learning and teaching business model innovation from a pedagogical standpoint. The students’ survey shows that it helps them remember, understand, and apply a conceptual model of business model dynamism. According to Bloom’s taxonomy (revised by Krathwohl, 2002), the scores concerning how the application is understood and can be applied are consistent with our expectations. Our results thus match Leschke’s (2013) conclusions in that the business model is useful for introducing entrepreneurship to non-business students. Educators can adopt the dynamic business model as a simplified tool to better understand the origins and types of changes in business models, compare cases, and get more insights into the degree of changes to their business model. It can also help in teaching business models, consistently comparing and analyzing data regarding the origins and types of sequential changes in business models in a graphical manner, which allows for more effective information transfer.

7. Limitations and Future Research

While this research contributes several novel insights to the emerging literature on entrepreneurship teaching, some limitations should be acknowledged. The first limitation stems from the fact that certain aspects of the thematic analysis were conducted with subjective judgment, and authors are responsible for all the interpretations of the open-questions response. In addition, this research lacks triangulation in the student evaluations, which were primarily based on self-reported data. Future research could strengthen the validity of the findings by triangulating student feedback with additional data sources, such as instructor assessments or peer evaluations. In this research, we focus on engineers in a single institution. However, future research can extend the research in different contexts to analyze the business model education in non-engineering students to apply business model approaches to further enhance generalizability.

Future research could compare the effectiveness of various business model frameworks within different classroom settings, aiming to generate diverse, high-quality approaches to teaching business model innovation. Exploring how tools such as illustrative examples, case studies, and business model frameworks perform—whether used sequentially or simultaneously, and with varying group sizes—could yield valuable insights into optimizing pedagogical strategies. The dynamic business model framework, introduced in this paper, represents an initial step toward teaching the complexities of business model dynamics. As a contribution to both academic research and practical education, it equips educators and students with a structured tool to analyze the processes, origins, and types of changes that occur in business models. By using this framework, students can systematically compare cases, assess the degree of freedom entrepreneurs and managers have in adapting their models, and gain deeper insights into the factors driving business model evolution. The framework’s versatility allows for multiple applications. For instance, it enables students to consistently analyze and compare data related to the origins and types of business model changes. Its graphical representation simplifies complex information, making it easier and faster for students to grasp business model dynamics compared to traditional textual descriptions. Furthermore, the framework can be expanded and refined—such as by incorporating additional business model elements or integrating a broader range of external factors—offering even greater depth and adaptability for both educational and practical purposes. Another interesting avenue for further research to develop deeper knowledge of business model dynamics regarding the key role of business model consistency.

8. Conclusions

Scholars have increasingly criticized the traditional approach to entrepreneurship education, which focuses on new approaches to teach business model innovation (Demil et al., 2015). The business model canvas (BMC), introduced by Osterwalder et al. (2010), has become a broadly adopted tool for visualizing a firm’s business model in entrepreneurship education (Verrue, 2014). In educational settings, students commonly use the BMC to design business propositions for their own start-up ideas or to analyze and summarize the models of existing firms. While the BMC is valuable for structuring how value is delivered and captured, research indicates that its format may hinder creativity due to its reliance on predefined elements (N. Bocken & Snihur, 2020). In addition, when merely representing the business logic at a single moment in the growth of a start-up, it limits the learning process about the dynamics of new start-ups (Rosenberg et al., 2011; Carter & Carter, 2020; Euchner & Ganguly, 2014; Cosenz, 2015; Toro-Jarrín et al., 2016; Fritscher & Pigneur, 2015). Hence, there is a need to present the business dynamics in business model innovation through a dynamic business model framework.

We followed the experiential learning approach and focused on teaching BMI through applying and analyzing BMI in real start-up cases. We applied a two-phase research design by first asking students to apply and analyze the BMI of real start-ups in both the current BMC and the proposed dynamic business model framework. Following their analyses, master’s students were administered a survey to assess the benefits of the proposed dynamic business model framework. The results show that the current business model canvas has limitations to capture the dynamics of BMI, which can be addressed by our proposed dynamic business model framework. The proposed framework can improve students’ level of understanding of BMI and, in particular, its dynamic nature.

Using a dynamic tool to assess business model dynamics enables students to critically evaluate the current operations of technology-based start-ups and understand that the business model architecture is shaped by the dynamic environment in which these ventures operate. We suggest that students engaged in team-based business development activities can benefit from utilizing online templates of dynamic business model frameworks to design and analyze business models across different stages of growth. Especially in a tech-oriented educational setting, such as engineering programs, this method supports the adoption of a more creative, design-thinking mindset for opportunity recognition and subsequent business model development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.K. and V.S.; methodology, H.K.; validation, H.K.; formal analysis, H.K.; data curation, H.K. and V.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.K.; writing—review and editing, V.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Delft University of Technology (protocol code 3534 and date of approval: 15 November 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdelkafi, N., Makhotin, S., & Posselt, T. (2013). Business model innovations for electric mobility—What can be learned from existing business model patterns? International Journal of Innovation Management, 17(1), 1340003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achtenhagen, L., Melin, L., & Naldi, L. (2013). Dynamics of business models—Strategizing, critical capabilities and activities for sustained value creation. Long Range Planning, 46(6), 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R., & Zott, C. (2001). Value creation in e-business. Strategic Management Journal, 22(6–7), 493–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R., & Zott, C. (2012). Creating value through business model innovation. Sloan Management Review, 53(3), 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Archibald, M. M., Radil, A. I., Zhang, X., & Hanson, W. E. (2015). Current mixed methods practices in qualitative research: A content analysis of leading journals. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14(2), 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpiainen, R. L., & Kurczewska, A. (2017). Learning risk-taking and coping with uncertainty through experiential, team-based entrepreneurship education. Industry and Higher Education, 31, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden-Fuller, C., & Haefliger, S. (2013). Business models and technological innovation. Long Range Planning, 46(6), 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden-Fuller, C., & Morgan, M. S. (2010). Business models as models. Long Range Planning, 43(2–3), 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandera, C., Collins, R., & Passerini, K. (2018). Risky business: Experiential learning, information and communications technology, and risk-taking attitudes in entrepreneurship education. International Journal of Management in Education, 16(2), 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, R. (2020). Adapting to constructivist approaches to entrepreneurship education in the Chinese classroom. Studies in Higher Education, 45(8), 1694–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, S. (2013). Why the lean start-up changes everything. Harvard Business Review, 91(5), 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bocken, N., & Snihur, Y. (2020). Lean startup and the business model: Experimenting for novelty and impact. Long Range Planning, 53(4), 1019–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N. M. P., Schuit, C. S. C., & Kraaijenhagen, C. (2018). Experimenting with a circular business model: Lessons from eight cases. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 28, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwman, H., & Fielt, E. (2008). Service innovation and business models. In H. Bouwman, H. de Vos, & T. Haaker (Eds.), Mobile service innovation and business models (pp. 9–30). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M., & Carter, C. (2020). The creative business model canvas. Social Enterprise Journal, 16(2), 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadesus, R., & Ricart, J. E. (2011). How to design a winning business model. Harvard Business Review, 89(1/2), 100–107. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcante, S. A. (2014). Designing business model change. International Journal of Innovation Management, 18(02), 1450018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J., & Rieple, A. (2013). Assessing students’ entrepreneurial skills development in live projects. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 20(1), 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, H. Y., & Fauvel, C. (2013). Criticisms, variations and experiences with business model canvas. European Journal of Agriculture and Forestry Research, 1(2), 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Clarysse, B., Mosey, S., & Lambrecht, I. (2009). New trends in technology management education: A view from Europe. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 8(3), 427–443. [Google Scholar]

- Cosenz, F. (2015, September 10–12). Conceptualizing innovative business planning frameworks to improving new venture strategy communication and performance. A preliminary analysis of the “dynamic business model canvas”. The XXXVII AIDEA Conference, Piacenza, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- DaSilva, C. M., & Trkman, P. (2014). Business model: What it is and what it is not. Long Range Planning, 47(6), 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demil, B., & Lecocq, X. (2010). Business model evolution: In search of dynamic consistency. Long Range Planning, 43(2–3), 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demil, B., Lecocq, X., Ricart, J. E., & Zott, C. (2015). Introduction to the SEJ special issue on business models: Business models within the domain of strategic entrepreneurship. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 9(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doganova, L., & Eyquem-Renault, M. (2009). What do business models do? Innovation devices in technology entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 38(10), 1559–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppler, M. J., Hoffmann, F., & Bresciani, S. (2011). New business models through collaborative idea generation. International Journal of Innovation Management, 15(6), 1323–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euchner, J., & Ganguly, A. (2014). Business model innovation in practice. Research-Technology Management, 57(6), 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Farber, V. A., Prialé, M. A., & Fuchs, R. M. (2015). An entrepreneurial learning exercise as a pedagogical tool for teaching CSR: A Peruvian study. Industry and Higher Education, 29(5), 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A. (2008). Entrepreneurship education at crossroads: Towards a more mature teaching field. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 16(4), 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielt, E. (2014). Conceptualising business models: Definitions, frameworks and classifications. Journal of Business Models, 1(1), 85–105. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, N. J., & Saebi, T. (2017). Fifteen years of research on business model innovation: How far have we come, and where should we go? Journal of Management, 43(1), 200–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, N. J., & Saebi, T. (2018). Business models and business model innovation: Between wicked and paradigmatic problems. Long Range Planning, 51(1), 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritscher, B., & Pigneur, Y. (2015). Classifying business model canvas usage from novice to master: A dynamic perspective. In International symposium on business modeling and software design (pp. 134–151). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Giesen, E., Riddleberger, E., Christner, R., & Bell, R. (2010). When and how to innovate your business model. Strategy & Leadership, 38, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giones, F., & Brem, A. (2017). Digital technology entrepreneurship: A definition and research agenda. Technology Innovation Management Review, 7(5), 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, P. G., & Rice, M. P. (2007). Entrepreneurship education. Edward Edgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Günzel, F., & Holm, A. B. (2013). One size does not fit all—Understanding the front-end and back-end of business model innovation. International Journal of Innovation Management, 17(1), 1340002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. W., Christensen, C. M., & Kagermann, H. (2008). Reinventing your business model. Harvard Business Review, 86(12), 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Jouison-Laffitte, E., & Verstraete, T. (2008). Business model et création d’entreprise. Revue Française de Gestion, 181(1), 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, A., & Paquin, R. L. (2016). The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable business models. Journal of Cleaner Production, 135, 1474–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakouris, A., & Morselli, D. (2020). Addressing the pre/post-university pedagogy of entrepreneurship coherent with learning theories. In Entrepreneurship education: A lifelong learning approach (pp. 35–58). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Kakouris, A., Morselli, D., & Pittaway, L. (2023). Educational theory driven teaching in entrepreneurship. The International Journal of Management Education, 21(2), 100814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamp, L. M., Meslin, T. A., Khodaei, H., & Ortt, J. R. (2021). The dynamic business model framework—Illustrated with renewable energy company cases from Indonesia. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(4), 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanagha, S., Volberda, H., & Oshri, I. (2014). Business model renewal and ambidexterity: Structural alteration and strategy formation process during transition to a cloud business model. R&D Management, 44(3), 322–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharbeet, G., Khodaei, H., Scholten, V. E., & Ortt, R. (2024). Business model dynamics during the growth stages of technology-based start-ups. In Academy of management proceedings (Vol. 2024, p. 16915). Academy of Management. [Google Scholar]

- Khodaei, H., & Ortt, R. (2019). Capturing dynamics in business model frameworks. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 5(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Kranich, P., & Wald, A. (2018). Does model consistency in business model innovation matter? A contingency-based approach. Creativity and Innovation Management, 27(2), 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(4), 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, F., Jouison, E., & Verstraete, T. (2017). Learning and teaching the business model: The contribution of a specific and dedicated web application. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 20(2), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Leschke, J. (2013). Business model mapping: An application and experience in an introduction to entrepreneurship course. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 16, 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Magretta, J. (2002). Why business models matter. Harvard Business Review, 80(5), 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Maresch, D., Harms, R., Kailer, N., & Wimmer-Wurm, B. (2016). The impact of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial intention of students in science and engineering versus business studies university programs. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 104, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markides, C. (2006). Disruptive innovation: In the need for a better theory. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 23(1), 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, A. (2010). Why lean canvas vs. business model canvas? Practice trumps theory. Available online: https://www.leanfoundry.com/articles/why-lean-canvas-versus-business-model-canvas (accessed on 9 October 2013).

- Morris, M., Schindehutte, M., & Allen, J. (2005). The entrepreneur’s business model: Toward a unified perspective. Journal of Business Research, 58(6), 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M. H., & Liguori, E. (2016). Preface: Teaching reason and the unreasonable. In Annals of entrepreneurship education and pedagogy (pp. xiv–xxii). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Motta, V. F., & Galina, S. V. R. (2023). Experiential learning in entrepreneurship education: A systematic literature review. Teaching and Teacher Education, 121, 103919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G., Linan, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N., & Walmsley, A. (2017). The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. The Academy of Management Learning and Education, 16(2), 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neck, H. M., & Corbett, A. C. (2018). The scholarship of teaching and learning entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 1(1), 8–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neck, H. M., & Greene, P. G. (2011). Entrepreneurship education: Known worlds and new frontiers. Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neergaard, H., Tanggaard, L., Krueger, N., & Robinson, S. (2012, November 6–8). Pedagogical interventions in entrepreneurship from behaviorism to existential learning. 2012 Institute for Small Business and Entrepreneurship, Dublin, Ireland. [Google Scholar]