Abstract

The concepts of variable and parameter are fundamental for mathematical activity but are also challenging to rigorously introduce at a didactic level. In this paper, we discuss findings from an 11th-grade class interdisciplinary project involving mathematics and linguistics, promoting a conceptual approach to the learning of variables and parameters through narratives. We analyze the written productions of 22 Italian students across two tasks: the first aimed at exploring differences in the meaning of variables and parameters while employing a logico–scientific or narrative mode of thinking; the second involved a meta-reflection on the methodological tools used in the disciplines involved. Students’ productions were qualitatively analyzed using content analysis and thematic analysis, respectively. The analysis enables an elaboration on students’ understanding of the different roles of variables and parameters and of their epistemic features. Students’ conceptualizations of variables and parameters went beyond formal description, drawing on a variety of real-world situations. Moreover, the meta-reflection on the methodological tools shows new awareness of students’ understanding of disciplinary concepts. These findings suggest that interdisciplinary approaches involving mathematics and linguistics can effectively support the conceptual understanding of algebraic notions in secondary school. We therefore recommend further research exploring the integration of narrative contexts and cross-disciplinary collaborations in mathematics teaching.

1. Introduction

The concepts of variable and parameter are fundamental for mathematical education worldwide, yet introducing them at a didactic level poses persistent challenges. Variables and parameters stand for numbers of quantities or objects, and they assume different meanings depending on the specific context. The literature in mathematics education reveals that these concepts are often presented operationally and procedurally at school, without a deep exploration of their theoretical implications (Arcavi et al., 2016; Schoenfeld & Arcavi, 1988). This reflects a tacit principle suggesting that certain mathematical facts are left partially obscure to students (Hanna, 1989). The present study aims to investigate how students conceptualize variables and parameters through an interdisciplinary approach that integrates mathematics and linguistic–narrative practices. In particular, we explore how narrative thinking and linguistic analysis can support students’ conceptual understanding of these foundational algebraic notions.

Variables and parameters appear at different stages across national curricula worldwide, but similar learning difficulties emerge across educational systems. For instance, early algebra initiatives in North America, Europe, and Asia emphasize the progressive introduction of variable thinking from primary school onward (Blanton & Kaput, 2011; Kieran, 2022; Malara, 2003). However, empirical studies conducted in various countries highlight that students often conflate variables with unknowns, treat parameters as fixed constants without understanding their generative role, and struggle to interpret symbolic representations across multiple registers (Bardini et al., 2005; Bloedy-Vinner, 2001; Eisenberg, 2002; Furinghetti & Paola, 1994; Korntreff & Prediger, 2022; Malisani & Spagnolo, 2009).

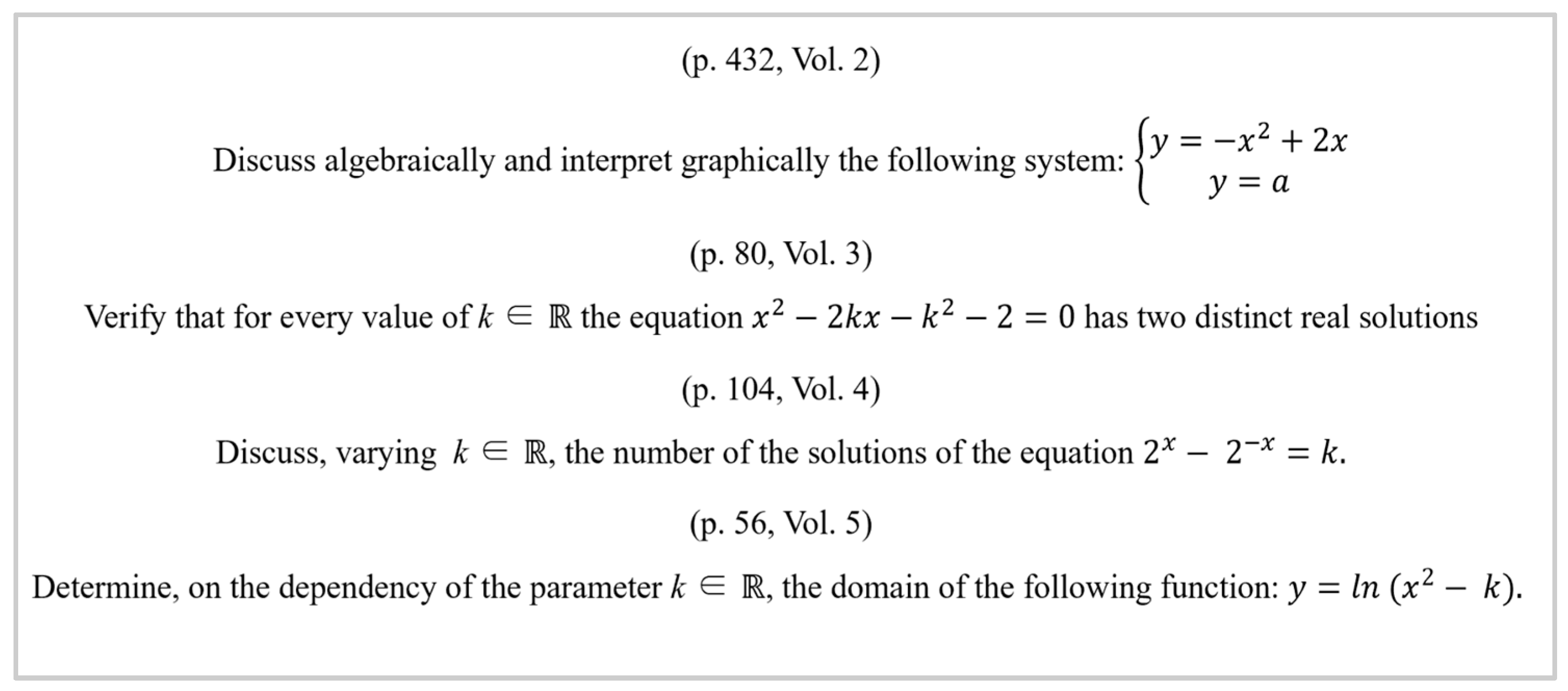

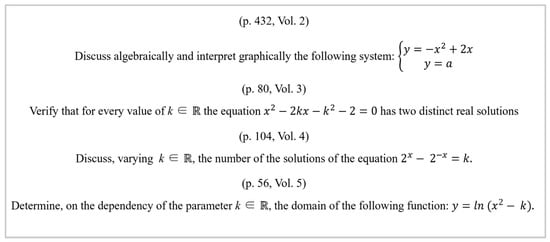

Against this global background, the Italian educational context represents a particularly illustrative case. Reviewing Italy’s mathematics curriculum reveals that parametric problems were addressed as early as the 1870s, as seen in graduation exam tasks (Lugli, 1890). Although current ministerial documents (Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca [MIUR], 2010) do not explicitly mention variables and parameters, Italian textbooks still include an abundance of procedural tasks on solving parametric equations (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Some examples of tasks concerning parametric equations adapted and translated from Sasso and Zanone (2019).

This situation mirrors what occurs in many other countries, where parameters are often introduced through symbolic manipulation rather than through conceptual or modelling perspectives. While this procedural emphasis ensures technical fluency, it may limit students’ opportunities to develop a flexible and meaningful understanding of variables and parameters as tools for describing relationships between quantities. The present study addresses this international educational challenge by proposing an interdisciplinary, narrative-based approach designed to support a deeper conceptualization of these notions.

The relationship between mathematical symbolism and linguistic structures has been widely explored in international research. Studies in mathematics education and applied linguistics show that grammatical analysis, sentence parsing, and syntactic decomposition support students’ ability to interpret complex symbolic expressions and problem statements (Gerofsky, 1996; Nemirovsky, 1996). Across different educational systems, students are trained to use brackets, hierarchical structures, and functional dependencies in both language and mathematics, suggesting deep structural analogies between the two domains (Matsumoto & Nakai, 2023).

From this perspective, variables can be seen as linguistic-like placeholders that acquire meaning through their syntactic position within symbolic expressions, much like words acquire meaning within sentences (Arcavi et al., 2016). Similarly, parameters function analogously to contextual modifiers in language, shaping the global structure of a relationship without directly participating in local variation. International research on algebraic thinking confirms that students benefit from instructional approaches that explicitly connect symbolic syntax with linguistic syntax (Kieran, 2022).

Empirical studies further show that narrative and grammatical approaches enhance students’ engagement with variable-based reasoning by grounding abstract symbols in meaningful communicative contexts (Bazzini et al., 2009; Korntreff & Prediger, 2022; Taranto, 2020; Zan, 2011). These findings provide a strong theoretical and empirical foundation for integrating linguistic analysis into the teaching and learning of variables and parameters.

This study presents instances of teaching and learning practices from an interdisciplinary project involving mathematics and linguistics (Italian and Latin) implemented in an 11th-grade class. Such an educational project can be considered interdisciplinary as it involves closely linked concepts and skills from two disciplines studied to generate new applications and new analyses (McGregor, 2004). Recent research in mathematics and science education has emphasized that true interdisciplinarity requires more than juxtaposing disciplinary contents: it involves developing a “beyond-disciplinary” awareness that critically questions the epistemic assumptions and boundaries shaping each field (Branchetti & Levrini, accepted; Capone, 2022; Satanassi et al., 2023). From this perspective, interdisciplinarity becomes a way to rethink how knowledge is organized and how teachers and students negotiate meaning across disciplinary borders—a vision that also guides the present study. Indeed, we believe that a new synergy might emerge from the transfer of knowledge between the disciplines involved in the interdisciplinary project.

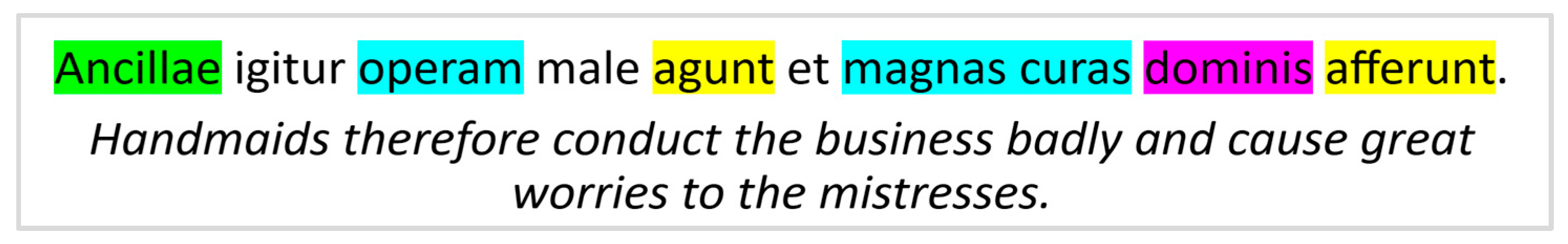

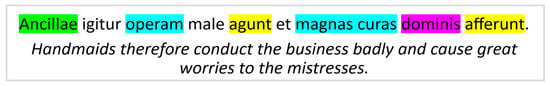

In the Italian educational system, students learn Italian as their primary language of instruction, and Latin is traditionally a mandatory subject in many high schools. Latin being an unspoken language, its study focuses on written translation (the so-called “versions”), and sentence analysis is a preliminary and central step aimed at reconstructing meaning from morphological markers (cases, inflections) rather than from fixed word order or prepositions. For this reason, visual and symbolic strategies (e.g., colours, parentheses, bars) are systematically used to identify syntactic functions before translation. These strategies operate as cognitive supports specific to Latin’s grammatical system and are not typically employed, in the same structured way, in the teaching of Italian or other modern languages. An example of how the analysis of a Latin sentence may be implemented is shown in Figure 2. Colours are used to identify words assuming the same logical function within the text (in the example, green for the nominative case, blue for the accusative case, pink for the ablative case, and yellow for predicates).

Figure 2.

Analysis of a Latin sentence. Sentence adapted from a textbook used in Italy (Conte & Ferri, 2009).

Studying Latin remains important mainly because it fosters logical and critical thinking, linguistic and text analysis, and problem-solving (Lucifora, 2022). All these processes and forms of reasoning are certainly a point of contact with mathematics.

A peculiarity of the humanities is also a narrative way of thinking and communicating. Such a narrative mode of understanding reality and experience has also been proven to be valuable in mathematics. Indeed, narratives allow students to connect mathematical abstract concepts to everyday contexts, and there are studies on this even for the concept of variables (e.g., Korntreff, 2023).

The results of the interdisciplinary project presented here demonstrate how some students, guided through a series of tasks, reflected on the concepts of variables and parameters from a mathematical perspective, supported by narratives.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Variables in Mathematics

As previously mentioned, the concept of variable is crucial in secondary school mathematics education, and its understanding is necessary for a meaningful understanding of all advanced mathematics. Five main meaning facets have been identified (Arcavi et al., 2016):

- Placeholder, when the variable is an empty place to be filled in with a specific value, as in [ ] + 5 = 6 + 2, where the empty box represents the value that makes the equality true (in this case, 3);

- Unknown number to be found, e.g., when solving equations;

- Varying quantity, when the variable stands for a domain of possible values in a dynamic process, e.g., a functional relationship where dependent and independent variables co-vary (Thompson & Carlson, 2017);

- Generalized number, when the variable is used to express general properties or relationships, as the associative law of addition, (a + b) + c = a + (b + c);

- Parameter, when the variable determines a situation as a whole. For instance, when the parameter denoting the slope of a line changes, it changes the entire trend of the line.

Variables are represented by symbols; hence, their treatment requires what Arcavi has called “symbol sense” (Arcavi, 1994). This idea was born amidst a change in algebra instruction, switching from a focus on symbolic manipulations to algebra as a tool for understanding, communicating, generalizing, and proving. Developing symbol sense turns out to be relevant not only in an algebraic perspective but also in a calculus one. Indeed, symbol sense means being able to create specific symbolic expressions for describing a certain situation, and this translation of a situation into symbols also requires making a decision on what to represent and how. Such translation may be particularly challenging for conceptualizing dynamic situations involving co-varying quantities. Indeed, understanding the variable concept as something dynamic—a varying quantity—is an aspect often underrated in math curricula (Thompson & Harel, 2021).

Tacit conventions exist regarding the use of different letters in different contexts (e.g., x, y, z for unknowns or undetermined variables; a, b, c for coefficients of a curve in its canonical form; h, k for parameters within families of lines or conics); these conventions may confuse students and lead them to interpret them as rigid designators (Arzarello et al., 1994; Chiarugi et al., 1995). Several misconceptions may arise, such as the well-known letter-as-object misconception (Küchemann, 1981) and its various subtypes, which appear to depend on the task’s features (Klingbeil & Moons, 2025).

Even in university courses, students often struggle with handling parametric equations and understanding applications of theorems with parameters (Chiarugi et al., 1995). Students tend to favour symbolic manipulations over graphical representations, without being able to recognize which approach is more convenient (Arcavi, 1994), and strive to interpret natural language statements (Vinner, 1989). The concepts of variable and parameter require early attention in secondary school to avoid conceptual and manipulative difficulties (Chiarugi et al., 1995; Thompson & Harel, 2021).

2.2. Narratives

In the history of humanity, storytelling represents one of the earliest and most enduring expressions of the narrative mode of thought, created to give meaning to reality and everyday experiences and to support learning and knowledge transmission. According to Bruner’s narrative principle (1986), the human mind organizes knowledge through two fundamental and complementary modes, the logico–scientific thinking and the narrative thinking.

“[The logico–scientific mode], attempts to fulfil the ideal of a formal, mathematical system of description and explanation. It employs categorization or conceptualization and the operations by which categories are established, instantiated, idealized, and related one to the other to form a system… […] The imaginative application of the narrative mode leads instead to good stories, gripping drama, believable (though not necessarily “true”) historical accounts. It deals in human or human-like intention and action and the vicissitudes and consequences that mark their course. It strives to put its timeless miracles into the particulars of experience, and to locate the experience in time and place.”(Bruner, 1986, pp. 11–13)

These two modes of thought are irreducible to one another, yet complementary, and reveal different epistemic orientations toward meaning-making.

Bruner (2006) further emphasized that narrative thinking allows the individual to connect the dimensions of reality (the external world) with that of experience (the internal, subjective world). This connection is particularly relevant in interdisciplinary educational contexts, where students are required to move across different epistemic frameworks and to negotiate meanings that cannot be fully captured within a single disciplinary language. In this sense, narrative thinking can function as a mediating space between disciplines, supporting the transfer and reinterpretation of knowledge. Narrative approaches have been shown to support students’ engagement with algebraic ideas, allowing learners to construct meaning and explore relationships between quantities in context and in real-world situations (Nemirovsky, 1996; Schoenfeld, 1991). From an interdisciplinary perspective, narratives allow students to explore how mathematical ideas emerge, evolve, and interact within shared problem situations, making visible the epistemic assumptions underlying each discipline.

Therefore, teachers play a crucial role in devising and creating contexts or narrative backgrounds, understood as a space and time in which to activate and practice reflective and critical thinking (Nemirovsky, 1996), as well as to develop narrative skills, “understood as the capacity to tell but also to listen, to interpret and construct meaning, i.e., to attribute meaning to events and learning, conscious of being in a situated situation; but also to stimulate a direction—to see, therefore, some kind of projectuality” (Raimondo, 2023, p. 8, English translation by the authors). This process aligns with an interdisciplinary vision of education, in which knowledge is not merely juxtaposed but reconfigured through students’ active engagement with multiple disciplinary perspectives.

Promoting the use of narrative thinking in school contexts means fostering a contextualized analysis of knowledge, even in mathematics, and recognizing the imaginative dimension as an important aspect of students’ engagement with real-world problems in mathematics. Narratives have already been shown to be a suitable means to initiate in-depth comparisons, allowing students to reflect on the epistemic specificities of different meanings of variables (e.g., Korntreff, 2023). This provides encouraging evidence to keep on exploring this line of research.

3. Research Questions

In light of the research objectives outlined in the Introduction and the theoretical elements previously introduced, we formulate the research questions guiding this study as follows:

- Which meanings of variable and parameter emerge from students’ written productions, benefiting from the support of the scientific and narrative thinking approaches?

- How did the interdisciplinary nature of the project contribute to improving students’ understanding of disciplinary concepts?

The first research question focuses on students’ understanding of the mathematical concepts at stake, variables and parameters, while disentangling their thinking approaches. The second research question instead refers to a meta-level and investigates the cross-contamination of methodological approaches between the disciplines involved.

4. Research Context

The educational project, here described, took place in an 11th-grade class of 22 students at a science-oriented secondary school in Italy, during the 2020/2021 school year. An effective interdisciplinary collaboration requires time and opportunities for planning, as well as dialogue, and faces methodological challenges (Silvestri et al., 2025). The interdisciplinary nature of this project is reflected in the collaboration between the mathematics and physics teacher, Silvia Beltramino (one of the authors), and the Italian and Latin teacher (hereafter referred to as the math teacher and the Latin teacher, respectively). The task design and implementation were co-designed by the teachers and the researchers’ team (the remaining authors). Regular meetings were held during both phases, and ongoing analysis informed the next steps in the implementation. Co-presence lessons, led by the Latin and math teachers, occurred as a concrete sign of this interdisciplinary collaboration.

Students begin studying Latin in grade 9, focusing on grammar and translating short sentences. Then, during the following grades, they focus more on translating versions, initially adapted and simplified ones, and then original versions from Latin authors. Concerning the students’ mathematical knowledge of variables and parameters, the math teacher, having taught the class for three years, familiarized students with working with different mathematical registers (algebraic, graphical, numerical) without specific lessons on variables and parameters. However, students encountered these concepts while studying parametric equations, exponential and logarithmic functions, conics, and analytical geometry problems throughout the year.

The project began with some classes focused on exploring covariation between quantities in the conceptualization of real phenomena (Thompson & Carlson, 2017). Students analyzed the mathematical and physical relationship between temperature and humidity (Bagossi, 2024). Real-time data collection, graphing with GeoGebra, and subsequent qualitative and quantitative analysis led the students to observe that, as temperature increases, humidity decreases, and vice versa. The project further involved interpreting psychrometric charts1 and discussing the role of independent/dependent variables, and parameters. In the words of the students, “assigning a role to a quantity implies a change in standpoint in the problem”. For example, transforming relative humidity into a variable or a parameter does not change the situation, but the perspective from which the situation is described. Students observed that the relationship is always the same, just expressed in different terms.

Following these statements, the math teacher, in agreement with the Latin teacher, set up a narrative background, proposing the reading of the science fiction story “The Master, the Waiter and the Customer” by Sheckley (1971), in which the same episode is told through the eyes of the three protagonists: the waiter, the customer, and the owner of a restaurant. As students observed, the various standpoints provide different details of the episode told, and only by reading all three one can obtain a complete picture of the situation. The math teacher pointed out the similarities between what students said, Sheckley’s story, and the role of parameters and variables in mathematics.

Simultaneously, co-presence lessons between the Latin and the math teachers tackled the analysis of various texts: Latin sentences to identify main and subordinate clauses, Italian poetries to identify rhythmic structures, and mathematics word problems to recognize the role of variables and parameters. Students applied methodological approaches to text structural analysis learnt in the linguistic lessons, such as colour coding or parentheses, to denote the different functions of elements in texts (see Figure 2 as an example). The project ended with a classroom discussion, led by both the teachers involved, on the analogies that emerged throughout the analysis of different kinds of text (Latin versions, poems, texts of mathematical problems), emphasizing that, akin to literary texts, multiple standpoints in a mathematical situation arise from the various roles variables can assume.

Following these classes, students delved into a mathematical problem related to the relationship between temperature, absolute humidity, and relative humidity. In addition to the resolution of the problem, the task required students to have a thorough understanding of the text, identifying the variables at stake, and the role played by the different representations and semiotic registers. Some weeks later, students were requested as homework to elaborate on a written report, Task 1, consisting of a reflection on what they had learnt about variables and parameters in mathematics until that moment. During such a task, they were left free to rely on the use of any digital tool they considered useful:

Task 1—In mathematics, it is important to grasp and explain the relationships between mathematical objects, especially between variables and parameters, specifying what varies and what remains the same. How would you describe this aspect of mathematics to a young student entering the first year of high school? Give an explanatory example.

Then, another report, Task 2, was administered as homework on one of the last days of school. Its purpose was to investigate which methodological approaches, acquired by students during their school education, were useful to them in facing mathematical problems, and specifically to better understand the different roles of variables and parameters.

Task 2—Throughout this year, among other things, we have reflected on the relationships between mathematical objects. At times, our work was carried out in collaboration with the Italian/Latin teacher. Have the analysis tools you acquired in your Italian and Latin courses been useful in solving mathematical problems? And have they helped you understand the relationships between mathematical objects, especially, to distinguish the role of variables and parameters? Think back on your learning journey from your first year [of secondary school] up to now, and explain which tools you believe have helped you to deepen your understanding of mathematics.

5. Data Collection and Analysis

We examined the written productions of the 22 students, labelled as Si (i = 1, …, 22), for the two tasks and conducted a qualitative analysis.

For Task 1, we consider the students’ written productions as their attempts to produce mathematical understanding about variables and parameters, drawing on all the stimuli provided throughout the project (e.g., the real-world experiments on temperature and humidity; Sheckley’s story, the text’s structural analysis for the translation of the versions; …) as well as their prior knowledge. Initially, we conducted a qualitative content analysis (Miles et al., 2014) to identify logico–scientific thinking or narrative thinking. Then, we outlined the meanings of variable emerging from the productions, and we coded how symbols were used to denote variables. Finally, we performed a cross-case analysis to connect the identified meanings of variable with the predominant thinking modes (logico–scientific vs. narrative) adopted in the texts.

For Task 2, we carried out a thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) to identify elements of interdisciplinarity emerging from the texts. Specifically, we read carefully all the protocols to gain familiarity and then coded all instances revealing that methods adopted in mathematics were perceived as beneficial for work in linguistics and vice versa. Next, we clustered the generated codes into potential themes. These emerging themes were then refined and defined through descriptive labels. The themes were elaborated and then iteratively revised in order to ensure clarity and avoid repetition. In what follows, each theme will be supported by illustrative extracts from the data to enhance credibility.

Among the 22 students who participated in the whole project, two (S7 and S16) did not complete Task 1, and one (S10) did not complete Task 2.

6. Findings

In this section, we summarize the outcomes for all students on each of the two tasks, emphasizing both the most common trends and the less frequent responses. Subsequently, to provide an exhaustive and illustrative overview, we will focus on selected productions as illustrative of widespread patterns and a few distinctive, though rare, elaborations.

6.1. Task 1

From the students’ written production, it clearly emerges that variables and parameters stand for numerical values. Referring to variables, S3 writes that for variables such values are “arbitrary, not necessarily fully known or even and often unknown”. Semiotic aspects related to the way variables and parameters are identified emerged in the productions of 19/20 students. All of them indicated, specifying expressions such as “generally” and “most of the time”, that the independent variable is indicated with x and the dependent variable with y. Different letters were used for the parameter: k by 9/19 students; m by 5/19, and four of them also introduced q as a letter to refer to a second parameter; a by 3/19; and n by 1/19. Two students spoke generically of a parameter, without indicating it with a specific letter. Only S9 pointed out that “[variables and parameters] are most often indicated by x, y and k”, but, in his example, he used as letters the initials of the objects he considers (basket weight = p, apples = m, basket size = g—note that the choice of letters is in line with the relevant Italian translations, e.g., “weight” is “peso”). The analysis of the expressions used by the students reveals their awareness that chosen letters for variables and parameters are conventional.

Six out of nineteen students brought up process-related aspects when explaining the definitions of variables and parameters to a potential grade 9 student: “To the independent variables we can assign any value” [S6], “y is the dependent variable because to know what it is worth we have to assign a value of x” [S11], “The value that [the parameter] takes on does not depend on anything, indeed it will be ‘decided’ by us” [S20] (emphasis added).

The formulation of Task 1 puts emphasis on a covariational perspective on variables and parameters, as this was the approach mostly stimulated throughout the first phases of the project. However, students were let completely free to reveal their own conceptualizations. Among the five facets of variables introduced in the Theoretical Background section, two of them were prominent in students’ productions. For the definition of variable, in 15/20 productions, students brought up the varying quantities meaning, referring explicitly to the concept of functional dependence (dependent vs. independent variable), S2 referred to the correspondence approach, while S5 and S8 mentioned the input/output approach, using the metaphor of a “machine” to express how one quantity changes in response to another. One student, S18, instead elaborated on a covariational perspective while describing the dependent variable as follows: “as my x varies, my y also varies”. The second predominant meaning was that of unknown (7/20), with examples often referring to the context of equations. Five out of these seven students adopted a logico–scientific mode of thinking in their productions. Concerning the definitions of parameter, all of the students addressed this as requested by the task itself, and a variety of facets and roles emerged. Seven students (S2, S3, S10, S11, S13, S17, S19) claimed parameters can be constants, arbitrary or varying, coefficients (S2, S17), or an independent variable (S2, S17, S18). The variety of roles that a parameter can assume is acknowledged by the students themselves. The most prevalent characterization in students’ productions was related to how parameters affect functions, and, in particular, their graphical representations. Parameters “vary the form of the function without, however, varying its structure” [S8].

Twelve out of twenty students used logico–scientific thinking, i.e., they proposed conceptual explanations and referenced formal mathematical descriptions, calling into question functions (mostly straight lines or parabolas) expressed in their symbolic or graphical form. Some also made use of different registers of representation simultaneously. One preferred freehand drawings with a digital application, while four others made use of graphical representations with GeoGebra or Desmos. For example, S21 wanted to show how the presence of a parameter affects the equation of a line by setting manually some values of a and providing distinct graphical representations. Therefore, S21 proposed the following two functions, f: y = ax and g: y = x + a, specifying that, in both, y is the dependent variable, x is the independent variable, and a is the parameter, and then used GeoGebra to represent the functions f and g for two distinct values of a. The emerging conceptualization is that each value of the parameter determines a line and, by varying the parameter, a family of functions is generated (a bundle of lines with a proper or improper centre), depending on its law. A similar conceptualization but with a different implementation can be observed in S15. Instead of reporting “static” images made with GeoGebra, S15 used a “dynamic” resource, a screen recording in which he showed the GeoGebra implementation of the function y = kx. He rendered k by means of a slider, showing how the slope of the line varies.

Eight out of twenty students began with explanations relevant to logico–scientific thinking, then evolved into a narrative thinking: they proposed examples which they labelled as “practical”, “concrete”, “from everyday life”, “in reality”, and therefore referred to episodes pertaining to reality.

S1 generated an analogy using a real example, a volleyball serve, to explain that variables are always present and, depending on the value of one, the value of the other changes. Whereas the parameter is not essential and, as S1 says, does not change the “structure” of the function:

S1: “Thinking of a concrete example, we could consider a volleyball serve. We could say that the independent variable is the force that the hitter applies on the ball, the dependent variable is how far the ball lands (i.e., the distance between the hitter and the point where the ball touches the ground) and as a parameter we could put the height of the player. We can therefore see that the variables are always present, and depending on the value of one, the value of the other changes. The parameter is not essential and does not change the ‘structure’ of the function.”

A similar approach can be detected in S12 who used a logico–scientific elaboration to provide a formal definition of variables and parameters and then moved to a narrative approach, recruiting basic knowledge and structures coming from the context of modelling wind turbine:

S12: “Let us set a real example. Consider a wind turbine, which transforms the rotation produced by the wind into electrical energy. One might think of establishing a relationship between x and y, defining x as the kinetic energy of the wind and y as the electrical energy produced by the turbine. In this way, however, one would have to construct a different relationship for each individual wind turbine, or perhaps for each model and type. It would then be useful to introduce a parameter, which could be called k, to represent the efficiency of the turbine itself. In this way, a single equation could satisfy all needs (assuming there are no other parameters to consider), and allows the calculation of the electrical energy produced by any given wind turbine.”

The shift observed in S1 and S12 from a purely logico–scientific approach to a narrative contextualization (e.g., volleyball serve, wind turbine) illustrates how narrative thinking can act as a mediating space for interdisciplinary reasoning, allowing learners to translate abstract mathematical relationships into meaningful real-world scenarios.

Furthermore, S3 and S20 considered the so-called “change in standpoint”, extensively discussed and referenced in Sheckley’s story (1971).

S20: “[…] we will decide which of the two entities will be a variable and which will be a parameter. In the previous case [y = mx], the choice between the two will be indifferent, but if we take the function y = mx2, the choice of the variable and the parameter will change the graphical aspect. Indeed, if our independent variable is x, then we will almost always have a parabola (except if m = 0 because otherwise we will have a straight line), whereas if our independent variable is m, then graphically we will always have a straight line.”

While not explicitly utilizing narrative thinking, S20’s arguments relied heavily on the idea of a “change in standpoint” introduced during the project. S20, like S4, recalled the bundle of straight lines with proper centres, but then took a further step. He considered a quadratic function with which he can obtain either a family of parabolas or again a bundle of straight lines with a proper centre. It is not only a question of recalling and mastering the imaginative capacity or visualization of the mathematical object, but also of being able to skillfully play with the elements that constitute that object. The fact that S20 drew on it shows that the narrative background chosen by the mathematics teacher really did function for the students as the space–time in which to practise and activate critical thinking. Moreover, in realizing the change in standpoint, S20 permuted the roles of parameter and dependent variable between x and m.

6.2. Task 2

Thematic analysis of the 21 students’ written reflections revealed several recurring themes that illustrate different ways of perceiving and articulating the connections between mathematics and the humanities. These themes encompassed symbolic and linguistic dimensions of mathematical reasoning as well as metacognitive awareness of learning processes. Six themes were identified (in order of frequency): the perceived connection between mathematics and Latin (12/21 students), variables and parameters (8/21), the use of brackets (7/21), argumentation (6/21), colour coding (5/21), and two cases of no answer. In what follows, each theme is discussed with illustrative excerpts, highlighting how students drew analogies between mathematical and linguistic reasoning and how such analogies reflect interdisciplinary awareness. Table 1 summarizes the frequency of each theme, the students involved, and the theme description.

Table 1.

Overview of thematic analysis results.

The most frequent theme concerned students’ recognition of methodological similarities between the two disciplines. Several students described how structured procedures and logical ordering in Latin translation were analogous to problem-solving steps in mathematics:

S1: “Latin and mathematics are two subjects that require an ordered procedure. […] I often try to find connections between mathematical objects which facilitate understanding.”

S5: “understanding the links between disciplines […] helped me see mathematics more comprehensively.”

S6: “in both subjects, certain operations must be done before others […] translating a sentence and solving an expression follow similar logical sequences.”

This reflects Bruner’s distinction between logico–scientific and narrative thinking: students applied narrative and contextual understanding from Latin to the formal reasoning structures of mathematics (Bruner, 1986, 2006).

By recognizing that both disciplines require logical coherence in explanations and reasoning, some students emphasized the role of argumentation and precise communication:

S3: “I had not realized how important communication is in both speaking and writing for full understanding.”

S7: “speaking correctly in Italian helps to make mathematics more comprehensible […] I now explain each step in solving an exercise.”

This reflects Bruner’s idea of narrative thinking as a vehicle for structuring knowledge and giving meaning to experiences (Bruner, 1986; Raimondo, 2023).

Students explicitly reflected on the mathematical notions of variable and parameter, often linking them to linguistic concepts or analytical strategies learned in Italian and Latin. Their reflections demonstrate awareness of the multiple meanings of variables (Arcavi et al., 2016), as well as the importance of symbol sense in creating and interpreting mathematical expressions:

S4: “the logic and procedure from Latin allowed me to find a more effective method to identify variables and parameters.”

S8: “learning to ‘break down’ a sentence helped understand relations between elements in a problem […] colours and brackets helped study variables and parameters.”

S9: “distinguishing elements was fundamental to discuss variables and parameters […] leveraging linguistic differences helped to clarify definitions.”

These findings suggest that early attention to variables and parameters, combined with interdisciplinary strategies, supports conceptual understanding and might mitigate common difficulties highlighted in the literature (Korntreff & Prediger, 2022; Schoenfeld & Arcavi, 1988).

Some students highlighted the usefulness of brackets not only to identify variables and parameters but, more generally, to organize complex structures, both in Latin sentences and in mathematical expressions:

S1: “I was impressed by the effectiveness of using mathematical elements, such as parentheses, in other areas […] to analyze Latin sentences.”

S7: “round, square, and curly brackets in Latin helped me divide main clauses and subordinate clauses […] a strategy transferable to mathematics.”

This supports the development of symbol sense and the ability to translate a situation into a structured representation, a key aspect of algebraic reasoning (Arcavi, 1994; Thompson & Harel, 2021).

Finally, some students reported that the use of colours, initially applied in Latin analysis, was also helpful in mathematical problem-solving:

S2: “there are elements like colours, for example, or ‘mathematical punctuation,’ which proved useful in contexts beyond standard exercises. […] Using different colours or parentheses was particularly effective for analyzing sentences.”

S7: “the use of colours is very useful in Latin. […] It also helped me in mathematics […] colours help me to orient myself better while solving problems.”

Colour coding served as a visual and semiotic strategy to distinguish different elements and structure reasoning across both disciplines. This aligns with Arcavi’s (1994) concept of symbol sense, highlighting how students use signs to represent abstract quantities and relationships.

These reflections illustrate that semiotic strategies serve as cognitive supports, bridging the symbolic demands of algebra with linguistic analysis, and facilitating both logico–scientific and narrative reasoning (Bruner, 1986).

7. Discussion

This study investigated how an interdisciplinary project, integrating mathematics and linguistic contexts, influenced students’ conceptualizations of variables and parameters. In light of our qualitative analyses, in what follows, we comment on the three main conceptual cores of our research: epistemic considerations on the conceptualization of variables and parameters, the potentialities of narratives, and the interdisciplinary nature of the project.

7.1. Epistemic Considerations on Variables and Parameters

The interdisciplinary nature of the project supported the emergence of a nuanced understanding of variables and parameters, going beyond a mere formal description. Not only through the resolution of the given mathematical problem, but also through the written productions of Tasks 1 and 2, students demonstrated awareness of the roles of variables and parameters as changing within the same mathematical task. Even when students used canonical letters for variables and parameters (Task 1), they demonstrated mastery of the symbolic register without interpreting these letters as rigid designators (e.g., S20 in Task 1).

The first research question investigated meanings of variable and parameter emerging from students’ written productions. Among the facets of variables, the most acknowledged among the students’ production were varying quantity and unknown. The distinction between independent and dependent variables lies in a dependence relationship (the variation in the former determines the variation in the latter) between the two that can be identified, for example, by looking at the real-world examples provided by students [S11 and S9 in Task 1]. The students’ reasoning revealed different underlying conceptions of functions (i.e., input–output, correspondence, and covariation—see S2, S5, and S8 in Task 1), which together illustrate their flexible understanding of the variable as expressing a dependency between quantities. When students employed a narrative way of thinking, variables were used to model quantities in real-world dynamic situations, expressing properties of generality (e.g., S1’s volleyball example, or S12’s turbine efficiency example, both in Task 1). Parameters were described as affecting the trend of a function without changing the “structure” of the function (S20 in Task 1). Conversely, the unknown facet was primarily connected to equation-solving contexts and was often articulated through a logico–scientific way of thinking.

Seven students, out of twenty, defined the parameter as a varying constant, an expression that is actually documented in the literature (Bloedy-Vinner, 2001). The graphical register has a strong relevance: if the independent and dependent variables are those represented, respectively, on x and y axes, the parameter is encapsulated in the slider, but the role assumed by the variables at stake depends on the chosen graphical representation. The use of sliders helps students observe that, if a parameter can be seen as a constant within a specific scenario (S21 in Task 1), when varying a parameter, a family of curves is generated, and so are several scenarios or settings (Thompson, 2011). These observations resonate with recent findings showing how the teacher’s role is essential in shaping students’ interpretations of parametric functions in dynamic environments (Bagossi et al., 2025), highlighting the benefits of framing parameters as determining multiple mathematical scenarios rather than fixed constants.

S9’s answer to Task 1 instead reveals an understanding of parameter closer to that of a varying quantity expressed using the symbolic register in his example (each value of a determines a different relationship between the number of apples and their total cost), and, as S9 says, a can be intended as an unknown that can be determined using values of x and y.

7.2. The Potentialities of Narratives

The narrative background provided (namely, Sheckley’s story proposed by the teachers) prompted narrative skills in the students. Indeed, students were able to interpret real-world situations and construct the meaning of variables and parameters by connecting the mathematical content to prior knowledge and contextual examples. Narrative facilitated interactions between verbal and graphical registers, allowing students to consider mathematical concepts from multiple perspectives and to draw analogies from everyday situations involving variables and parameters. The use of narratives also promotes inclusiveness in mathematics activities, aligning with previous research findings (Bazzini et al., 2009). On the one hand, narratives generally avoid the introduction of mathematical activities in a way that is far from students’ understanding and risks producing adhesion only to formal aspects of the discipline (Cobb et al., 1992), e.g., “acting on […] symbols which did not have to symbolize anything beyond themselves” (p. 103). On the other hand, as the thematic analysis of Task 2 shows, the project facilitated students’ meta-reflections on the tools and strategies employed in the classroom. Meaning-making—the actual understanding of the concepts of variable and parameter linked to real-world contexts—occurred through storytelling, where the students actively narrated, imagined, and constructed connections between knowledge rather than merely memorizing concepts.

Many of the comments in this and the previous section show how students have developed a deep and wide sense of symbol: most of them show a clear understanding of the role of variables, of the meaning of their covariation in functional relationships, and of the different role of parameters as governing the common mathematical structure of the different relationships expressed by the role of the covariation between the independent and the dependent variables. The examples related to Task 2 show important links with those of Task 1: the narratives (e.g., that about the volleyball or that about the wind turbine) clearly show how the variable–parameter duo is jointly operating in their descriptions within a productive dialectic between them. Through the narrative, students create a fresh meaning for the relationship between the two.

7.3. The Interdisciplinary Context

The thematic analysis of Task 2 highlights that most students were able to identify meaningful links between mathematics and linguistics. Procedural and structural analogies, as well as semiotic and communicative strategies, were the most frequently mentioned connections. These results align with theoretical perspectives on algebraic thinking (Kieran, 2022; Malara, 2003), symbol sense (Arcavi, 1994), and narrative mode (Bruner, 1986, 2006; Raimondo, 2023), suggesting that interdisciplinary reflection fosters both conceptual understanding and metacognitive awareness. Students’ ability to transfer strategies across domains exemplifies the interplay between logico–scientific and narrative thinking, supporting the idea that meaningful learning in mathematics benefits from contextualized and reflective practices. The interdisciplinary nature of the project promoted cross-disciplinary transfer. Students drew analogies between mathematical and linguistic reasoning, applied semiotic strategies such as colour coding and brackets, and developed meta-reflective awareness of their learning processes. This highlights the potential of interdisciplinary tasks to foster both conceptual understanding and reflective practices. Overall, students’ meta-reflection on what they are learning represents a valuable goal in a robust teaching–learning of mathematics, highlighting the value of combining narrative contexts with formal mathematical reasoning to foster deeper conceptual understanding (Schoenfeld & the Teaching for Robust Understanding Project, 2016).

The findings of the activities and of students’ written productions show an interesting genesis of what Schoenfeld (1991) has called (and continues to call) the processes of “Mathematics Sense Making”, a wide notion that includes that of “symbol sense” elaborated by Arcavi (1994). In the 1991 paper, Schoenfeld shows through commented examples how it is important “to blur the boundaries between formal and informal mathematics: [namely] to indicate that, in real mathematical thinking, formal and informal reasoning are deeply intertwined’’ (p. 311). He argues that, ‘‘in general, the quality of reasoning using formal systems depends on the quality of the maps from the situation being explored to the formal system, on the correctness of the reasoning within the formal system, and on the interpretation of results in the formal system that is transferred to the situation being analyzed’’. Our activities in fact allow students to generate these maps through the following: (i) the links between the algebraic signs structure and that of the Latin language: in a semiotic abbreviated picture, parenthesis and colours; (ii) the production of different narratives that link the different descriptions of “the same” situation to the relationship between different roles of signs: in an abbreviated math picture, variables and parameters.

The relevance of these findings also highlights how the collaboration between teachers of different disciplines and mathematics educational researchers in designing and coaching the activities has had remarkable consequences on students’ conceptualization of the variable–parameter relationship, as shown by students’ answers to the two tasks. From the one side, the common methodology used in facing algebraic and Latin sentences and, from the other side, the effectiveness of using different standpoints in describing real and formal facts in a narrative form has helped them to positively elaborate a rich conceptualization of variables and parameters. Their productions show how they effectively “blurred the boundaries between formal and informal mathematics” through the “maps” between the two generated by the interdisciplinary approach of our project.

As a final observation, the effectiveness of the project is the result not only of an interdisciplinary approach to a pivotal mathematical concept, where mathematics and linguistics have contributed to students’ conceptualization, but also of effective collaboration between teachers (from different disciplines) and educational researchers in mathematics. This collaboration is essential for producing research that can generate both effective practices in the class and valid theoretical results that properly focus such practices. This issue has been highlighted in a recent document by the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (2024) and is traditionally featured in Italian research in mathematics education, where the figure of the “researcher–teacher” (Arzarello & Bussi, 1998) is important, as was the case in this project.

8. Conclusions

The results of this study suggest several implications for practice, research, and curriculum design.

For teachers, narrative contexts and interdisciplinary projects can be used to help students connect formal mathematical concepts with real-world situations. Activities that allow learners to manipulate variables and parameters in meaningful contexts, and to explore different standpoints, foster critical thinking, flexibility, and a deeper understanding of mathematical relationships. Collaborations between teachers of different disciplines, as in this project, support the creation of rich learning environments where students can negotiate meaning across disciplinary boundaries.

For researchers, the study highlights the potential of narrative thinking as an epistemic device that mediates between disciplines. Future research could investigate how narrative and logico–scientific reasoning interact, and how researcher–teacher collaborations influence both the design and the effectiveness of interdisciplinary learning experiences.

For curriculum designers, integrating narrative-driven, interdisciplinary tasks into mathematics and linguistic curricula can enhance conceptual understanding and meta-reflective skills. Designing activities that blur the boundaries between formal and informal mathematics, and that incorporate digital tools such as GeoGebra or other simulations, can create learning environments that are both engaging and conceptually productive.

Overall, the project demonstrates that effective interdisciplinary learning relies on the combination of well-designed tasks, narrative scaffolds, and close collaboration between teachers (and/or researcher–teachers) and researchers, offering a model for designing educational experiences that simultaneously promote understanding, reflection, and meaningful cross-disciplinary connections.

Limitations of the study include the specific background of the students involved in an extended project on the topic and the lack of interviews with the subjects about their experiences to check if our interpretations are commensurate with their own experiences as they remember them. The absence of other sources for triangulation of the data, such as students’ interviews, suggests caution in generalizing results.

Looking ahead, future research should explore how narrative background can be further integrated into regular mathematics tasks to develop awareness about various mathematical concepts and how this meaning-making process takes place. Eventually, we would be interested in the possibility of implementing this interdisciplinary teaching on a larger scale, to discuss the strengths and limitations of such an approach and how teachers should be involved in the design to make it successful.

Author Contributions

All authors have contributed to conceptualization, methodology, and data curation. E.T. and S.B. (Sara Bagossi) have contributed to the data analysis and to the writing of the original draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

High school “M. Curie”—Pinerolo granted approval for this research with approval number 0004849 on 23 April 2022. Participation was voluntary; no sensitive or identifiable information was collected for this study; all data were anonymized.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the students’ parents for the use of the students’ responses.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

E. Taranto and S. Bagossi were partially supported by the “National Group for Algebraic and Geometric Structures, and their Applications” (GNSAGA-INdAM). This support is gratefully acknowledged. A heartfelt thank you to teacher Beltramino’s students, the true protagonists of the educational project, and to teacher Rossetti for his precious collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Note

| 1 | A psychrometric chart is a graphical representation of the physical properties of moist air at a constant pressure. Typically, it displays temperature on the horizontal axis, absolute humidity on the vertical axis, and a different curve is obtained for different percentages of relative humidity. |

References

- Arcavi, A. (1994). Symbol sense: Informal sense-making in formal mathematics. For the Learning of Mathematics, 14(3), 24–35. [Google Scholar]

- Arcavi, A., Drijvers, P., & Stacey, K. (2016). The learning and teaching of algebra: Ideas, insights and activities. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzarello, F., Bazzini, L., & Chiappini, G. P. (1994). L’Algebra come strumento di pensiero, Analisi teoriche e considerazioni didattiche [Algebra as an instrument of thought, Theoretical analysis and didactic considerations]. Quaderno n. 6 del CNR, Progetto strategico: Tecnologie e Innovazioni didattiche. Dipartimento di matematica. [Google Scholar]

- Arzarello, F., & Bussi, M. G. B. (1998). Italian trends in research in mathematical education: A national case study from an international perspective. In A. Sierpinska, & J. Kilpatrick (Eds.), Mathematics education as a research domain: A search for identity (Vol. 4, pp. 243–262). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagossi, S. (2024). Engaging in covariational reasoning when modelling a real phenomenon: The case of the psychrometric chart. Bollettino dell'Unione Matematica Italiana, 17(2), 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagossi, S., Taranto, E., Beltramino, S., & Arzarello, F. (2025). Roles of teacher in synchronous online mathematical discussion on parametric functions. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardini, C., Radford, L., & Sabena, C. (2005). Struggling with variables, parameters, and indeterminate objects or how to go insane in mathematics. In H. L. Chick, & J. L. Vincent (Eds.), Proceedings of the 29th conference of the international group for the psychology of mathematics education (Vol. 2, pp. 129–136). PME. [Google Scholar]

- Bazzini, L., Sabena, C., & Villa, B. (2009). Meaningful context in mathematical problem solving: A case study. In Proceedings of the 3rd international conference on science and mathematics education (pp. 343–351). CoSMEd. [Google Scholar]

- Blanton, M. L., & Kaput, J. J. (2011). Functional thinking as a route into algebra in the elementary grades. In Algebra in the early grades (pp. 5–23). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloedy-Vinner, H. (2001). Beyond unknowns and variables—Parameters and dummy variables in high school Algebra. In R. Sutherland, T. Rojano, A. Bell, & R. Lins (Eds.), Perspectives on school algebra (pp. 177–189). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branchetti, L., & Levrini, O. (accepted). Critical encounters with interdisciplinarity in mathematics pre-service teacher education. Recherches En Didactique Des Mathématiques. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J. S. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J. S. (2006). La fabbrica delle storie. Diritto, letteratura, vita [The story factory. Law, literature, life] (M. Carpitella, Trans.). Laterza. [Google Scholar]

- Capone, R. (2022). Interdisciplinarity in mathematics education: From semiotic to educational processes. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 18(2), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarugi, I., Fracassina, G., Furinghetti, F., & Paola, D. (1995). Parametri, variabili e altro: Un ripensamento su come questi concetti sono presentati in classe [Parameters, variables and more: Rethinking how these concepts are presented in class]. L’insegnamento della Matematica e delle Scienze Integrate, 18B(1), 34–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb, P., Yackel, E., & Wood, T. (1992). Interaction and learning in mathematics classroom situations. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 23(1), 99–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, G. B., & Ferri, R. (2009). Latino a colori [Latin in colors]. Mondadori Education. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, T. (2002). Functions and associated learning difficulties. In D. Tall (Ed.), Advanced mathematical thinking. mathematics education library (Vol. 11). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furinghetti, F., & Paola, D. (1994). Parameters, unknowns and variables: A little difference? In J. P. Ponte, & J. F. Matos (Eds.), Proceedings of the 18th conference of the international group for the psychology of mathematics education (Vol. 2, pp. 368–375). PME. [Google Scholar]

- Gerofsky, S. (1996). A linguistic and narrative view of word problems in mathematics education. For the Learning of Mathematics, 16(2), 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, G. (1989). ‘More than formal proof’. For the Learning of Mathematics, 9(1), 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kieran, C. (2022). The multi-dimensionality of early algebraic thinking: Background, overarching dimensions, and new directions. ZDM Mathematics Education, 54, 1131–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingbeil, K., & Moons, F. (2025). The omnipresence of the Letter-as-Object misconception: A multilevel Latent Transition Analysis on understanding variables. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 120, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korntreff, S. (2023). Supporting students’ comparisons of different conceptions of variables by telling stories–Insights from a design research study. In P. Drijvers, C. Csapodi, H. Palmér, K. Gosztonyi, & E. Kónya (Eds.), Thirteenth congress of the European society for research in mathematics education (CERME13) (pp. 584–591). Alfréd Rényi Institute of Mathematics and ERME. [Google Scholar]

- Korntreff, S., & Prediger, S. (2022). Students’ ideas about variables as generalizers and unknowns: Design Research calling for more explicit comparisons of purposes. In J. Hodgen, E. Geraniou, G. Bolondi, & F. Ferretti (Eds.), Twelfth congress of the European society for research in mathematics education (CERME12) (pp. 529–537). Free University of Bozen and ERME. [Google Scholar]

- Küchemann, D. (1981). Algebra. In K. M. Hart (Ed.), Children’s understanding of mathematics 11–16 (pp. 103–119). John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Lucifora, R. M. (2022). Latino e Competenze Trasversali Europee: Una lingua ‘morta’ per il futuro professionale [Latin and European Transversal Skills: A ‘dead’ language for the professional future]. Atti del convegno Latino, scuola e società, 13, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Lugli, A. (1890). Raccolta di temi di matematica [Collection of mathematics tasks]. Roma Tipografia Elzeviriana. [Google Scholar]

- Malara, N. A. (2003). Dialectics between theory and practice: Theoretical issues and aspects of practice from an early Algebra project. In N. A. Pateman, B. J. Dougherty, & J. T. Zilliox (Eds.), Proceedings of the 27th conference of the international group for the psychology of mathematics education (Vol. 1, pp. 33–48). PME. [Google Scholar]

- Malisani, E., & Spagnolo, F. (2009). From arithmetical thought to algebraic thought: The role of the “variable”. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 71(1), 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, D., & Nakai, T. (2023). Syntactic theory of mathematical expressions. Cognitive Psychology, 146, 101606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGregor, S. L. (2004). The nature of transdisciplinary research and practice. Kappa Omicron Nu Human Sciences Working Paper Series. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/238606943_The_Nature_of_Transdisciplinary_Research_and_Practice (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca [MIUR]. (2010). Indicazioni nazionali per licei [national guidelines for high school]. Available online: https://www.indire.it/lucabas/lkmw_file/licei2010/indicazioni_nuovo_impaginato/_decreto_indicazioni_nazionali.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. (2024). Linking mathematics education research and practice. Available online: https://www.nctm.org/Standards-and-Positions/Position-Statements/Linking-Mathematics-Education-Research-and-Practice/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Nemirovsky, R. (1996). Mathematical narratives, modeling, and algebra. In N. Bednarz, C. Kieran, & L. Lee (Eds.), Approaches to algebra: Perspectives for research and teaching (pp. 197–220). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Raimondo, E. M. (2023). I saperi che orientano: Il paradigma narrativo per una didattica orientativa [Orienting knowledge: The narrative paradigm for orientation education]. Lifelong Lifewide Learning, 20(43), 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sasso, L., & Zanone, C. (2019). Colori della matematica. Edizione blu [Colors of mathematics. Blue edition] (Vol. 5 α β). Petrini. [Google Scholar]

- Satanassi, S., Branchetti, L., Fantini, P., Casarotto, R., Caramaschi, M., Barelli, E., & Levrini, O. (2023). Exploring the boundaries in an interdisciplinary context through the family resemblance approach: The dialogue between physics and mathematics. Science & Education, 32(5), 1287–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, A. H. (1991). On mathematics as sense-making: An informal attack on the unfortunate divorce of formal and informal mathematics. In J. F. Voss, D. N. Perkins, & J. W. Segal (Eds.), Informal reasoning and education (pp. 311–343). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfeld, A. H., & Arcavi, A. (1988). On the meaning of variable. The Mathematics Teacher, 81(6), 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, A. H., & the Teaching for Robust Understanding Project. (2016). An introduction to the teaching for robust understanding (TRU) framework. Graduate School of Education. Available online: https://www.map.mathshell.org/trumath.php (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Sheckley, R. (1971). Pas de trois of the chef and the waiter and the customer. In Can you feel anything when I do this? And other stories (pp. 114–132). Doubleday & Company, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Silvestri, L., Bagossi, S., Pocalana, G., & Robutti, O. (2025). Towards a transdisciplinary approach in a mathematics teacher’s design of a STEAM activity. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 9, 100490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taranto, E. (2020). “Telling mathematics”: Storytelling and counting in pre-elementary school. Journal of Teaching and Learning in Elementary Education, 3(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P. W. (2011). Quantitative reasoning and mathematical modeling. In L. L. Hatfield, S. Chamberlain, & S. Belbase (Eds.), New perspectives and directions for collaborative research in mathematics education (Vol. 1, pp. 33–57). WISDOMe Monographs. University of Wyoming. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, P. W., & Carlson, M. P. (2017). Variation, covariation, and functions: Foundational ways of thinking mathematically. In J. Cai (Ed.), Compendium for research in mathematics education (pp. 421–456). National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, P. W., & Harel, G. (2021). Ideas foundational to calculus learning and their links to students’ difficulties. ZDM Mathematics Education, 53(3), 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinner, S. (1989). The avoidance of visual considerations in calculus students. Focus on Learning Problems in Mathematics, 11, 149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Zan, R. (2011). The crucial role of narrative thought in understanding story problem. Current State of Research on Mathematical Beliefs XVI, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.