1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic and technological advances pushed changes in teaching practices. Schools adapted to online and flexible formats. They started by simply digitizing traditional methods (

Beardsley et al., 2021). This transition demanded acquiring digital competencies and effectively engaging students in virtual environments. Many studies highlight the need to train teachers in technology-based digital teaching. This training helps them support flexible learning and encourage digital scholarship with open educational practices (

Låg & Sæle, 2019;

Weiß & Friege, 2021). However, some studies overlook key aspects like accessibility and inclusiveness (

Ainscow, 1995,

2024;

Ainscow et al., 2006). According to

Lopatina et al. (

2024), continuous professional development and institutional policies are key to promoting accessible learning environments. Without adequate training and systematic guidance, teachers might have trouble addressing the varied learning needs of their students.

The Learning Design for Flexible Education (FLeD) project involves six European universities and aims to support higher education teachers in flexible teaching design. A central component of the project is the FLeD Tool, a digital platform that scaffolds learning design by promoting asynchronous learning modalities, flexible educational approaches, and the integration of inclusive practices.

The authors, affiliated with one of the partner institutions, handled the projects’ pilot phase. During this phase, teachers designed learning scenarios based on a specific pedagogical structure (pattern) and on a set of guidelines (scaffolding) embedded in the FLeD Tool (

Albó et al., 2024) (

https://fledtool.upf.edu) (accessed on 30 July 2025). These guidelines provided effective strategies for adopting digital technologies and highlighted important considerations for the use of inclusive practices within the context of flipped learning environments.

This study explores the potential of the FLeD Tool to support inclusive learning design by addressing two main research questions (RQ):

How does the FLeD Tool support educators in designing accessible and inclusive learning scenarios?

What are the perspectives of experts in accessibility and inclusion regarding the learning scenarios designed using the FLeD Tool?

To address these research questions, the study analyzes the experiences of three teachers who used the FLeD Tool to design inclusive and accessible learning environments. Two Portuguese experts in accessibility and inclusive education were invited to evaluate the scenarios created. Through two qualitative interviews, the experts identified main barriers to inclusion and suggested strategies for overcoming them and enhance accessibility. Their insights contribute to a broader understanding of the potential and limitations of digital tools—like the FLeD Tool—in fostering inclusion in higher education.

The following sections of this article provide the theoretical grounding for the research, present the methodological approach, and report and analyze the findings from the expert evaluations. The article concludes with a discussion of the implications for inclusive digital pedagogy and recommendations for enhancing learning design practices in higher education.

2. Theoretical Context

The increasing availability of digital tools presents significant opportunities in higher education, yet a key challenge remains namely, the need to empower educators to adopt flexible, inclusive, and accessible teaching practices supported by technology. Current theoretical frameworks, including Universal Design for Learning (UDL), offer valuable guidance; nevertheless, a significant gap remains in providing comprehensive support for teachers. One potential solution to this issue is to facilitate dialogue between pedagogical innovation, digital literacy, and equitable access for all students. The present study aims to address this gap by contributing to the design of flexible, inclusive, and accessible digital learning experiences.

2.1. Flexible Learning Design

The COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated the digital transformation of education (

Afonso et al., 2020;

Morgado et al., 2021). During the lockdown, educational institutions were forced into emergency remote teaching, leaving little time to reflect on pedagogy. At the same time, emerging learning approaches have raised new challenges such as high academic demands, limited extracurricular opportunities, social isolation, and difficulties maintaining learning pace. However, research indicates that educators began to choose teaching methods more flexibly, adapting them to students’ needs and circumstances (

Noguera & Valdivia-Vizarreta, 2022).

teaching and learner management (pedagogical methods and strategies employed by educators and learning management);

operational management (course delivery and learner support mechanisms in flexible learning); and

institutional management (institutional strategies that enable open spaces for flexible design).

Flexibility refers to the ability of the pedagogical approach employed to accommodate diverse teaching modalities, including face-to-face, online, mixed, or hybrid formats (

Noguera et al., 2023).

FLeD is a dynamic educational approach (

Dikilitas & Noguera, 2023) that prioritizes inclusivity, supports diverse learning styles, allows for flexible task engagement, provides different options for interaction patterns, and integrates multimodality to enhance the learning experience. By applying these principles, educators can create stimulating and responsive learning environments tailored to the diverse needs of students.

In the FLeD conceptual framework, flexible learning—based on

Huang et al. (

2020)—eliminates constraints related to time, location, and pace, while offering diverse pedagogical choices. These choices include class schedules, course materials, teaching methods, learning resources, physical location, technological tools integration, completion timelines, and modes of communication.

Flexible learning design (FLD) is a teaching method that aims to create educational experiences tailored to different contexts. It seeks to address both instructional and interactional challenges that impact student engagement and attendance, while also promoting innovative and effective solutions. (

Dikilitas & Noguera, 2023).

FLD, as discussed in FLeD, is grounded in key pedagogical choices and values that enable students to customize their learning experience. These include:

learner choice (autonomy to choose participation modes that suit individual needs);

equivalency (access to similar learning activities and equivalent learning outcomes);

reusability (resources that are adaptable to different modalities);

accessibility (ensuring access to essential technological facilities and the ability to choose how to engage).

These guiding principles promote equitable access, involve students, and support diverse modes of participation.

By integrating these principles, FLeD (Learning Design for Flexible Education) seeks to enhance inclusive, student-centered digital pedagogical approaches. To ensure learners engage with content flexibly, the project’s flipped learning (FL) model supports autonomy, self-regulation, and co-regulation strategies (

Noguera et al., 2023).

2.2. Flipped Learning and Its Role in Flexible Learning

The Flipped Classroom (

Lundin et al., 2018) model aligns with the FLeD framework. It emphasizes learning as a social activity and encourages the development of regulatory skills across forethought, performance, and self-reflection phases.

Noguera et al. (

2022) highlight that flexible teaching and learning in the context of FC must go beyond traditional notions of flexibility to truly meet students’ individual needs. They argue that educators should have the autonomy to make choices in the design and delivery of their courses, while providing continuous support to help students succeed.

Furthermore,

Noguera et al. (

2023) also explored the adaptability of the FC model to diverse teaching modes in higher education. Their study shows that FC models maintain high levels of student satisfaction and positive learning outcomes.

Flexible teaching and learning enable adaptation across different teaching modalities, whether face-to-face, online, or hybrid approaches (

Kukulska-Hulme et al., 2022). Within the FLeD framework, the FC model shared responsibility between teachers and students. It supports student-centred learning, allowing students can study where and when they choose, access learning resources, and adapt the learning process to their educational needs, prior knowledge, and interests (

Dikilitas & Noguera, 2023).

The FC model aligns with flexible learning principles by reversing the traditional instructional sequence: students engage with instructional materials before class, and in-class time is used for active learning, discussion, and problem-solving (

Lundin et al., 2018).

Noguera et al. (

2022) argue that flexible teaching within the FC framework allows for personalized learning, enabling students to choose learning paths that suit their needs and engagement level and, to review material asynchronously before engaging in collaborative activities.

Research consistently suggests that FC models significantly improve student motivation, engagement, and learning outcomes (

Campillo-Ferrer & Miralles-Martínez, 2021;

Noguera et al., 2023). However, accessibility barriers and the lack of inclusive design may prevent students with disabilities from fully benefiting from flipped learning environments.

To address these challenges, the FLeD learning design tool (FLeD Tool) integrates patterns (constructive feedback, prior preparation, and team regulation), alongside pedagogical structures and an adaptive scaffolding system. These features support responsive teaching strategies to help adapt learning activities to students’ progress, ensuring inclusion in flexible learning scenarios.

2.3. Supporting Learning Design with the FLeD Tool

The FLeD Learning Design Tool is a web-based platform developed within the FLeD research project. It supports university teachers in creating flexible and inclusive learning scenarios using flipped learning patterns. The tool promotes inclusive education by guiding teachers in designing learning experiences that address diverse student needs, highlighting the essential role of flexibility.

The tool allows teachers to design learning scenarios that consider time, place, and pace, enabling students to engage with content tailored to their individual learning preferences. The FLeD Tool comprises several interrelated elements designed to support teachers in planning flexible and inclusive learning experiences. These features are based in pedagogical theory and offer both conceptual guidance and practical functionality.

Table 1 provides an overview of the main features of the FLeD Tool.

The FLeD tool guides teachers through the learning design process using a pattern-based approach and adaptive scaffolding system. Teachers can select suitable patterns and receive automatic recommendations based on their choices. The community platform and the toolkit have been developed to provide additional support and resources for inclusive design. The learning design editor has been designed to enable the customization of scenarios to meet the diverse needs of students.

By emphasizing flexibility and inclusiveness in learning design, the FLeD Tool aims to help teachers in creating learning scenarios that support all learners in achieving their educational goals. This approach ensures that educational experiences are both inclusive and effective for all while recognizing the diverse needs and preferences of learners.

2.4. Scaffolding Accessibility in Learning Design

Ensuring accessibility in digital learning environments requires a deliberate and systematic approach. The “Guidelines for Inclusion” (

Yovkova et al., 2023), an open educational resource developed within the FLeD project to assist teachers with inclusion issues in learning scenario design, categorizes accessibility strategies into key several areas:

Course Structure: Design of inclusive learning pathways that accommodate students with diverse abilities.

Digital Resources: Provide multimodal learning materials to support students with visual, hearing, or cognitive impairments.

Interactive Learning: Ensure that online discussions, group activities, and peer interactions are accessible to all students.

Assessment Strategies: Provide multiple assessment formats to meet the diverse needs of learners.

Yovkova et al. (

2023) emphasize the need to adapt flipped learning to address accessibility barriers, particularly for students with visual impairments, hearing impairments, and dyslexia. The authors suggest specific actions and strategies tailored to these Special Educational Needs (SEN).

While the FLeD Tool represents a significant advancement in flexible learning design, several challenges remain in integrating inclusive education principles into digital learning environments:

Lack of Teacher Training: Many educators lack both technical and pedagogical knowledge to implement accessibility measures effectively (

Lopatina et al., 2024).

Technical Barriers: Digital platforms often fail to meet basic accessibility standards, limiting the engagement of students with disabilities (

Veletsianos & Houlden, 2019).

Assessment Equity: Traditional assessment methods may disadvantage students requiring alternative formats (

Ainscow, 2024).

Yovkova et al. (

2023), in line with

Espada-Chavarria et al. (

2023), in highlight the importance of adapting inclusive pedagogical strategies for flipped learning contexts in higher education. Their focus on students with dyslexia, hearing, and visual impairments is based on the frequency of these SEND groups in higher education.

The Guidelines for Inclusion (

Yovkova et al., 2023) handbook, organize accessibility recommendations for FC by context: physical classroom (synchronous), virtual environment (synchronous), and fully online (asynchronous). Within each context, they provide practical strategies for content, interaction, and evaluation, aiming to reduce barriers for all learners. For instance,

Table 2 summarizes the most frequently recommended strategies for learning activities designed for visually impaired students in three different contexts.

3. Method

This study adopts a qualitative research design, employing semi-structured interviews with experts in inclusion and accessibility in higher education. This approach was chosen to gain a deeper understanding of challenges and best practices in inclusive learning design (

Creswell, 2013).

The study was conducted as part of the Learning Design for Flexible Education (FLeD) project, which explores how digital tools can improve accessibility and flexibility in higher education. By analyzing expert evaluations of learning scenarios designed with the FLeD Tool, the study aims to assess the tool’s effectiveness and identify areas for improvement.

The following subsections outline the participants, data collection process, and analysis procedures.

3.1. Participants and Context

Two Portuguese experts in accessibility and inclusive education participated in the study. They were chosen for their advanced academic qualifications, extensive of over a decade expertise, and participation in national and international projects and were interviewed on their key domains of expertise: higher education, special education, and digital accessibility and inclusion.

Table 3 summarizes the experts’ profiles.

Their complementary experiences and expertise range from the implementation of online courses to consulting on elearning in European projects (for example, Government Working Group—Special Needs in Science, Technology and Higher Education, EU4ALL–Accessible LifeLong Learning for Higher Education, EduTech Technologies and Accessibility in Virtual Higher Education, Inclusive Memory - Inclusive Museums for well-being and health through the creation of a new shared memory, Hela.H.Eduki–Inclusive Pedagogical Practices). This ensured a comprehensive and nuanced perspectives on this research topic, drawing from their theoretical knowledge and practical experience in diverse educational settings, as well as their understanding of accessible digital environments.

Both experts contributed to independently validating the FLeD Inclusion Manual and analyzing three Learning Scenarios designed by Portuguese higher education lecturers using the FLeD Tool. They provided feedback based on their expertise in accessibility, instructional design, and inclusive education.

The authors recognize that while interviewing only two experts offered rich, in-depth insights into their unique experiences, this qualitative approach limits the study’s generalizability and analytical richness.

3.2. Data Collection and Procedures

The data collection process included semi-structured interviews, allowing a balance between flexibility and consistency in the range of topics covered (

Bryman, 2012). The interviews aimed to explore experts’ perspectives on three aspects:

The inclusivity and accessibility of the learning scenarios designed by the Portuguese lecturers.

The effectiveness of the FLeD Tool in supporting accessible learning design.

Challenges and opportunities for improving digital accessibility in higher education.

Each interview lasted approximately 60 min and was conducted via Zoom. The participants consented to the recordings, which were transcribed verbatim and later translated into English for analysis.

The interview followed a structured protocol (see

Appendix A) developed based on existing guidelines for inclusion in digital education (

Yovkova et al., 2023). The protocol included categories such as: (i) General perceptions (How do you rate the inclusivity of the learning scenarios?); (ii) Digital accessibility (What are the main barriers to accessibility?); (iii) Assessment strategies (Are the assessment methods in the scenarios fair and inclusive?); (iv) Technology and platform usability (Does the FLeD Tool adequately support accessible learning design?) and, (v) Recommendations (What improvements would you suggest for the tool and learning scenarios?).

Three learning scenarios were selected for the expert evaluation as part of this study. Each scenario was designed by the lecturers using the FLeD Tool, and was expected to incorporate the flipped learning principles and apply the accessibility guidelines for such designs.

Table 4 summarizes the three evaluated learning scenarios.

Experts were asked to evaluate each scenario based on three main criteria: its level of inclusivity, the accessibility strategies implemented, and its alignment with Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles.

This study adhered to recognized ethical guidelines for research involving human participants. The following ethical principles were respected: informed consent; confidentiality; voluntary participation; and approval by the Ethics Committee of a participating university.

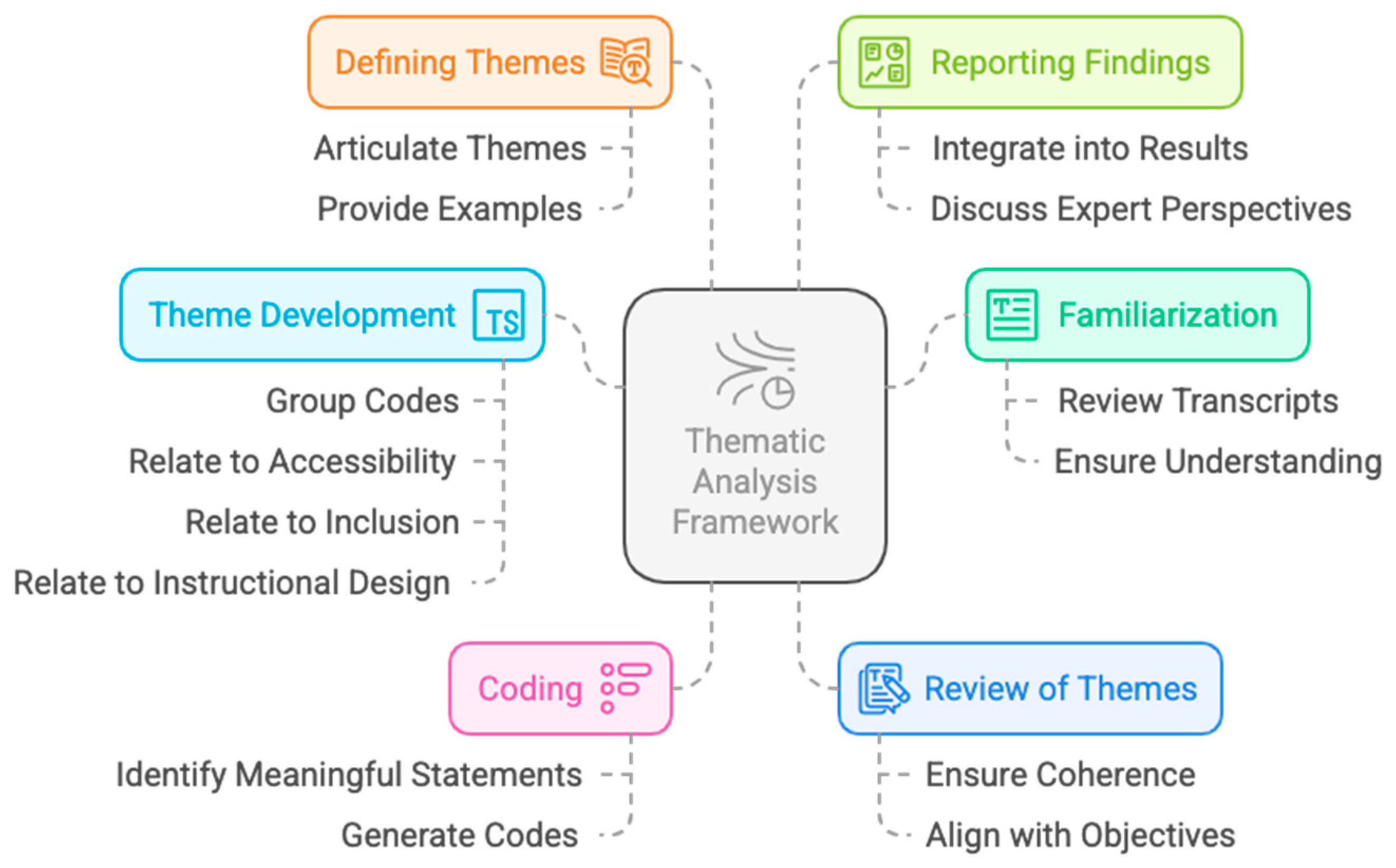

3.3. Data Analysis

Familiarization: Researchers reviewed transcripts multiple times to ensure a thorough understanding of the interviewees’ answers.

Coding: Initial codes were generated based on meaningful statements.

Theme Development: Codes were grouped into broader themes related to accessibility, inclusion, and instructional design.

Review of Themes: Emerging themes were refined to ensure coherence and alignment with the research objectives.

Defining Themes: Each theme was clearly articulated, with supporting quotations from the interviews.

Reporting Findings: Themes were integrated into the Results and Discussion sections, illustrating expert perspectives on inclusive learning.

To ensure validity and reliability, the themes were cross-checked by multiple researchers. Participants were invited to review the preliminary findings in a member-checking process to confirm accuracy and credibility.

4. Results and Discussion

The responses provided rich qualitative insights into best practices and areas for improvement in digital accessibility and inclusive learning design.

The analysis of the experts’ interviews highlighted key themes related to inclusive education, accessibility barriers, and the effectiveness of the FLeD Tool. Using thematic analysis (

Braun & Clarke, 2006), we categorized the findings into four primary areas: (1) Perceptions of inclusion and accessibility in higher education; (2) Evaluation of the FLeD Tool in supporting inclusive learning design; (3) Challenges identified in the learning scenarios and (4) Recommendations for improving inclusive learning design.

4.1. Perceptions of Inclusion and Accessibility in Higher Education

Expert 1 highlighted the persistent gap between institutional inclusion policies and their implementation in practice. Hence, it noted that many teachers lack adequate training or institutional support to implement inclusive teaching strategies, especially in relation to autism spectrum disorders. These observations align with recent findings by

Lopatina et al. (

2024), who argue that insufficiently structured training results in inconsistent and fragmented accessibility practices.

Experts identified several recurring barriers and key challenges to inclusive education. Expert 2 noted a generalized lack of faculty training, stating, “Many instructors are unaware of accessibility tools”. Expert 1 referred to institutional inconsistencies: “Each professor applies inclusion differently, with no clear guidelines”. Their statements reflect widespread concerns in the literature about institutional fragmentation (

Ainscow, 2024) and the absence of systematic accessibility integration (

Veletsianos & Houlden, 2019).

As noted by both experts, digital media and devices are used but are often not designed to accommodate neurodiverse learners needs particularly those with autism -highlighting the need for flexible and innovative solutions in higher education.

Indeed, autism in the context of higher education remains underexplored. Expert 1 emphasized that autistic students present highly diverse abilities and needs, yet few faculty members receive adequate training to support them effectively. Even though group tasks are often used, they can unintentionally leave out students with autism because of the social pressures they create, and this issue is noted in recent research on inclusive teaching. (

Ainscow, 2024;

Espada-Chavarria et al., 2023). Expert 2 shared this concern, noting that insufficient resources are often available to support effective interaction between students with hearing impairments and their peers during group work. Expert 2 also pointed to a lack of multimodal engagement options, which can restrict participation and undermine the principles of Universal Design for Learning (

Yovkova et al., 2023).

One recurring theme in the interview segments was flexibility. The accommodation of varied learners necessitates dynamic, flexible pedagogical practices that are personalized to meet the demands of each student, as explained by Expert 2.

In essence, both experts highlighted the discrepancy between the institutional aspirations and the practical implementation of inclusive practices in higher education. Although inclusion is acknowledged at the policy level, its application in regular classroom remains inconsistent. In the absence of adequate training and institutional support, many teachers find themselves lacking the necessary skills to address the specific learning needs of students, particularly those related to disability and neurodiversity.

These findings emphasize the importance of integrated institutional policies and thorough training programs as foundational steps toward more inclusive digital learning environments, as highlighted by

Bong and Chen (

2021).

4.2. Evaluation of the FLeD Tool in Supporting Inclusive Learning Design

The FLeD Tool was considered to be a valuable resource for designing flexible, student-centred inclusive learning contexts in higher education by both experts. They pointed out the tool’s predefined pedagogical patterns, which included constructive feedback, prior preparation, and team regulation, as effective in reinforcing inclusive teaching strategies and aligning with flipped classroom methodologies (

Dikilitas & Noguera, 2023). However, both experts also raised concerns about the tool’s limited capacity to support teachers identify possible accessibility gaps throughout the learning design process, which could compromise inclusivity. Expert 2 commented that: “The tool provides great pedagogical scaffolding, but it does not help educators identify accessibility gaps before implementing their learning designs.” This comment aligns with a prevailing concern in the literature regarding the absence of built-in accessibility checks in numerous digital education tools (

Espada-Chavarria et al., 2023), which are acknowledged as being essential for reducing the risk of unintentionally excluding students with disabilities (

Dikilitas & Noguera, 2023). Although the FLeD Tool supports pedagogical planning, the absence of automated accessibility checks weakens its practical contribution to inclusive learning.

While evaluating the ‘Virtual and Augmented Reality in Educational Contexts—Let Teachers Design!’ scenario, Expert 2 identified critical communication barriers that hinder student inclusion, thus noting that there is frequently no strategy to facilitate communication within groups in cases involving students with hearing impairments. Her question—“How can they communicate with their peers if they are unfamiliar with the local sign language? “—illustrates a broader gap in the design of collaborative tasks.

This lack of two-way communication strategies, particularly in group work, reinforces exclusionary dynamics while reflecting a recurring concern in inclusive learning research: that participation must go beyond presence—it requires structured, reciprocal involvement (

OECD, 2023).

Furthermore, Expert 2 also noted that current design patterns have a notable emphasis on task completion over meaningful inclusion, lacking differentiated means of engagement for students with diverse needs and abilities. To address this challenge, she proposed splitting student groups into participants and observers. Those students who directly engage with a simulation can later share their reflections with observers, promoting deeper comprehension through collaborative discussion. This reflective structure also promotes more inclusive pedagogy by allowing students with different abilities to contribute meaningfully.

Scenario 3, “Café para Todos”, was considered by the experts as the most inclusive, as it allowed students to choose between written, video, or audio format. Hence this multimodal flexibility aligns with UDL principles and enhances learner autonomy (

Yovkova et al., 2023).

Despite these strengths, Expert 2 raised concerns about the platform itself, particularly noting the unlabeled icons, its poor compatibility with assistive technologies, and its substantial reliance on external tools to meet accessibility standards. Furthermore, she highlighted the limited availability of training materials on inclusive teaching, which could limit educators’ ability to integrate inclusive practices within their learning designs.

4.3. Challenges Identified in the FLeD Tool and Learning Scenarios

While several modules within the pilot project flexible and multi-format options for students, others—particularly those dependent on visual or auditory interaction—evidenced significant accessibility gaps for students with diverse learning needs.

Expert 2 identified significant accessibility issues within both the platform and the ‘Guidelines for Inclusion’ manual, including validation errors when using standard accessibility tools. She noted the manual’s narrow focus limited to dyslexia, visual and hearing impairments as a major limitation, disregarding crucial areas such as motor difficulties, neurodiversity (e.g., autism) and mental health conditions. Similarly, Expert 1 also pointed out that the handbook itself was not accessible—only available in PDF format with inaccessible tables and written entirely in English, which represents a language barrier for many learners.

The two experts identified accessibility issues across all three learning scenarios analyzed, related to content format alternatives, assistive technology integration, and inclusive support structures.

Expert 2 expressed concerns about the lack of clear communication strategies, especially for group interactions involving students with hearing impairments. Although the scenarios implied interaction, there was no clear explanation of how educators would facilitate it in ways that ensure accessibility and inclusion.

In Scenario 1 (“Digital Educational Resources”) the primary accessibility issue was the absence of audio descriptions for visual content. The experts recommended adding text-to-speech tools and audio alternatives to improve usability for visually impaired learners.

Scenario 2 (“Virtual & Augmented Reality”) evidenced difficulties for visually impaired students. The highly visual format lacked any supportive alternatives, making meaningful interaction challenging. Working groups also created barriers can be challenging for students with hearing impairments due to the lack of planned communication strategies, such as sign language interpreters or captioning tools. Thus, Expert 2 noted the lack of engagement opportunities across all scenarios, pointing out that the dependence on singular activity formats diminished the potential for inclusive participation.

Scenario 3 (“Café para Todos” module) was considered as more inclusive, due to its multimodal nature, which is well aligned with UDL principles. However, the experts noted that the lack of explicit strategies—such as the inclusion of sign language support—limits participation for hearing-impaired students. Additionally, the unclear assessment criteria compromised the principles of transparency and fairness, for students with diverse needs. To address this difficulty, experts recommend incorporating captions, transcripts, and sign language interpreters.

Regarding the three designed scenarios, both experts emphasized the need for inclusive instructional design that integrates assistive technology, multimodal content, and clear accessibility protocols. Thus, they agree that several elements of the scenarios don’t offer multiple means of representation, action, and engagement, which is not in line with the Universal Design for Learning principles (UDL) (

Yovkova et al., 2023). As Expert 1 noted, “Students with disabilities should have multiple ways to access content, yet these scenarios mainly rely on text and visuals.” This supports the notion that inclusive design should be embedded at the structural level, rather than merely being applied at a later stage.

4.4. Recommendations for Improving Inclusive Learning Design

The experts provided several actionable recommendations to improve accessibility and inclusivity in digital education. These have been thematically organized under three key categories: technology, pedagogy, and policy.

4.4.1. Technology

Expert 2 suggested integrating a built-in accessibility checker. This feature would support teachers in identifying, recognizing, and addressing accessibility gaps early in the design process. This recommendation aligns with research emphasizing the relevance of built-in accessibility check in digital education tools to support inclusive practice (

Espada-Chavarria et al., 2023).

Expert 1 emphasized that students who were previously identified as having special education needs are often integrated into universal higher education frameworks without adequate adaptation in line with the principles of UDL (

Yovkova et al., 2023). This design framework promotes the integration of multimedia formats video, audio, and textual documents as core elements of inclusive teaching. Reliance on a single content modality, whether video, audio, or text, can create barriers for students with special needs. For example, documents can incorporate text and audio elements, improving accessibility in cases of dyslexia. This approach recognizes the variability of individual learning preferences and processes and underlines the need for tailored educational strategies.

4.4.2. Policy

Experts recommend standardized institutional policies on accessibility, alongside with faculty training programs. Expert 1 highlighted the challenge of achieving consistency in accessibility, including language, technology, and tools, while acknowledging the need for personalized approaches to meet specific cultural, religious, and learning needs. This reflects the general pedagogical tension between creating general accessibility features and accommodating individual differences (

Veletsianos & Houlden, 2019). As noted in the “Guidelines for Inclusion” (

Yovkova et al., 2023), teachers tend to rely on a reactive “overall solution”, instead of including accessibility issues in the initial learning design. On this matter, Expert 1 also identified language barriers as a growing concern in accessibility design, emphasizing that multilingual learning resources are crucial in today’s diverse and migratory student populations.

Expert 1 stated that higher education institutions must anticipate the needs of students who are now entering their programs. This involves updating resources and adopting teaching practices that reflect modern approaches to inclusion and accessibility. These anticipatory practices also extend to the assessment framework, where educators should provide flexible alternatives when students face challenges in collaborative work. Expert 1 also noted the challenge to address ethnicity. This includes integrating cultural and religious perspectives into educational design, which is essential for ensuring equal access to education and improving student success.

4.4.3. Pedagogy

Expert 1 emphasized the need of mandatory institutional training in inclusive pedagogy: “Higher education institutions must ensure that all educators receive training on accessibility standards and inclusive teaching methodologies.” Furthermore, she noted the need for teacher training focused on specific disabilities, emphasizing that inclusion should be a collective responsibility involving multidisciplinary teams. Furthermore, experts recommend that higher education institutions ensure all teachers receive training on accessibility standards and inclusive teaching methodologies. This training should focus on inclusive digital education, with the expected outcome of preparing faculty members to implement accessibility strategies effectively mainly in the field of technical and digital competencies (

Lopatina et al., 2024;

Veletsianos & Houlden, 2019).

Flexibility in teaching and learning formats, combining online and face-to-face teaching, can be both a solution and a challenge. While online learning increases access for some students, integrating different learning modes adds complexity for both students and teachers. This duality points out the necessity for inclusive guidelines that better respond to the needs of all students-including those with autism, dyslexia, or sensory impairments.

One specific area of concern was assessment. Expert 1 identified the complexities and challenges associated with peer assessment particularly the interpersonal dynamics between students. When students are required to assess peers with whom they share personal connections—whether positive or negative—the objectivity of the assessment can be compromised. This introduces an element of bias and can distort the perception of evaluation as a competitive exercise rather than an opportunity for constructive learning.

To address this issue, Expert 1 suggested incorporating alternative assessment strategies into the module design, providing students with options, and allowing them to choose between peer assessment and other evaluative methods, hence engaging with the format that best aligns with their needs. This flexibility is essential, especially in situations where social dynamics may present additional challenges, ultimately enhancing the fairness and effectiveness of the assessment process. These suggestions align with

Ainscow (

2024), who advocates for flexibility and choice in assessment design, and with

OECD (

2023), which advocates for institutional commitment to accessibility and digital inclusion.

In conclusion, the findings from the interviews reveal significant gaps in the inclusivity of the piloted learning scenarios, particularly in terms of accessibility and adaptability for students with disabilities. A primary challenge identified is the absence of specific strategies to support students with visual or hearing impairments in Scenario 2. As augmented reality is inherently visual, this module poses significant barriers for visually impaired students, and no alternatives are offered to provide an equivalent learning experience. Similarly, there is no provision for ensuring communication between hearing-impaired and hearing students, which could result in social isolation and reduced participation for students with hearing disabilities.

On the other hand, Scenario 3 showed more inclusive practices, by offering students multiple expression formats, thereby accommodating diverse preferences and needs. This flexibility is crucial to inclusive education, allowing students to work to their strengths rather than being constrained by rigid formats. However, the lack of explicit support for deaf students reveals some limitations.

In a broader sense, the absence of accessible resources and a user-friendly platform further increases the challenges of digital inclusive learning. As digital learning environments become increasingly central to education, ensuring the accessibility of both platforms and resources is critical. The failure of the platform to meet basic accessibility standards, such as proper labelling of symbols, poses a significant barrier to students with disabilities, making it difficult for them to engage fully with the content.

The experts’ recommendations—organized around technology, policy, and pedagogy— highlight the need for an institutional ecosystem embedding accessibility and inclusivity. Their insights reinforce the importance of anticipatory design, flexible assessment strategies, built-in accessibility checks, and continuous faculty training. Together, these actions support the transition of inclusive education from a mere aspirational policy into a consistent and equitable praxis.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the challenges that higher education institutions face in promoting accessibility and inclusion, focusing on the evaluation of the FLeD Tool—a web-based learning design tool that guides educators in creating adaptive and inclusive learning scenarios. Using qualitative interviews with two Portuguese experts in accessibility and inclusion in education, the study explored three learning scenarios designed by three Portuguese teachers using the FLeD Tool. Additionally, the experts provided several recommendations concerning the need for teacher training, the design of assessment tailored to this specific context, and the accessibility of online platforms.

The analysis of the interviews with the experts provided critical feedback on the scenarios, the tool’s functionalities, and the institutional conditions required to support inclusive digital learning.

Thematic analysis revealed four main areas of reflection: (1) Perceptions of inclusion and accessibility in higher education; (2) Evaluation of the FLeD Tool in support of the design of inclusive learning; (3) Challenges identified in learning scenarios; and (4) Recommendations to improve the design of inclusive learning. Across these dimensions, the analysis emphasised that institutional commitment, professional training, and technological infrastructure are all essential to promoting equity in digital education.

To explore the effectiveness of the FLeD Tool in supporting inclusive education, this study was guided by two research questions:

How does the FLeD Tool support educators in designing accessible and inclusive learning scenarios?

What are the perspectives of accessibility and inclusion experts regarding the learning scenarios designed with the FLeD Tool?

Regarding question 1, the findings demonstrated that the FLeD Tool provides structured pedagogical scaffolding systems and supports student-centered, flipped learning methodologies, promoting more interactive and flexible educational experiences. However, critical gaps were identified by the experts, the absence of an integrated accessibility checker, inadequate design strategies for learners with visual or hearing impairments, and limitations in supporting diverse communication formats-indicating further development is needed.

Addressing question 2, the experts feedback highlighted both the potential and the limitations of the learning scenarios created using the tool. While Scenario 3 (“Café para Todos”) was regarded as the most inclusive due to its multimodal flexibility, Scenario 2, which focused on augmented reality, presented substantial accessibility barriers. These findings evidenced the need for inclusive design principles to be systematically integrated throughout the design process, broader multimodal content options and stronger assistive technology integration.

Expert recommendations were organized across three interdependent domains: technology, policy, and pedagogy. The experts emphasised anticipatory design, inclusive assessment strategies, accessible interface design, and professional development in digital inclusion.

The FLeD Tool improved participants’ instructional methods and revealed the potential for broader use throughout institutions. However, its effective adoption demands an ecosystem of ongoing resource updates, inclusive assessment frameworks, and proactive accessibility design.

The study also acknowledges its methodological limitations. The findings, resulting from two expert interviews, provide both in-depth and specific insights. Although thematic analysis is an effective method of extracting meaning from qualitative data, the small sample size limits the generalizability of the findings (

Fugard & Potts, 2015). The triangulation of this data with additional sources, such as user testing and student feedback, would serve to further consolidate the analysis.

Furthermore, these results derive from two expert interviews and only three learning scenarios with limited SEND students, which may hinder the generalization of conclusions. We acknowledge that future research should involve a broader participant base, including students with diverse needs, instructional designers, and institutional decision-makers.

To conclude, although we agree that the FLeD Tool has the potential to guide inclusive digital learning practices, its impact will ultimately depend on how institutions embed accessibility into policies, training, and technology.

As digital and hybrid learning models continue to increase in higher education, it is essential to ensure that digital infrastructure and educational resources are fully accessible to all students.

Future research directions should consider broader perspectives, including different stakeholder groups, such as students with other needs and disabilities, as well as educational technologists, instructional designers, and policy makers. Additionally, it should explore scalability of the proposed model across different contexts and deepen engagement with underrepresented disability perspectives to ensure no learner is left behind.