Abstract

This systematic review aims to provide a comprehensive and up-to-date overview of the most effective identification protocols used to detect giftedness in primary school students, intended to be used by teachers, parents, and diagnostic professionals. This review, registered in PROSPERO (CRD420251064093), analyzed studies published between 2019 and 2024 in the PsycINFO, Web of Science, and Scopus databases. It included articles published in English or Spanish and focused on multidisciplinary fields. A total of 17 studies were selected and evaluated for quality using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale. The findings highlight the effectiveness of using multiple tools in the identification process, grouped into teacher nominations, family nominations, and tools for diagnostic professionals. This multidimensional approach helps reduce false negatives and supports the identification of underrepresented and twice-exceptional students. In conclusion, the identification of giftedness should be grounded in methods that prioritize general cognitive abilities over IQ scores and academic achievements.

1. Introduction

Numerous conceptualizations continue to coexist in the scientific literature regarding students whose abilities surpass the norm, and a variety of terms are used to refer to them (Sanchez et al, 2022). In this review, the term gifted and giftedness will be used to refer to this group of students. Traditionally, giftedness has been associated with several indicators, including high intelligence, creativity, outstanding academic performance, leadership, task commitment, and a high likelihood of success in culturally valued domains (Fernández et al., 2017; Peyre et al., 2016).

There are various theories and models that attempt to conceptually explain giftedness. One of them is the Differentiated Model of Giftedness and Talent, which describes it as the result of transforming natural abilities into fully developed competencies (Gagné, 2004). For their part, Harrison and Van Haneghan (2011) define giftedness as a potential present in learners that allows them to perform above their same-age peers.

More current perspectives, such as that of the National Association for Gifted Children (“A Definition of Giftedness that Guides Best Practice”; NAGC, 2019), define these students as those who demonstrate performance significantly above their peers in one or more areas and who require specific educational support to fully develop their potential. The NAGC (2019) further notes that gifted students can be found across all racial, ethnic, cultural, and socioeconomic groups. It is therefore essential to ensure equitable access to appropriate educational opportunities that can foster the development of their abilities. Additionally, Pasarín-Lavín et al. (2021) argue that in order to speak of giftedness, it is essential to take into account factors beyond students’ high ability in a specific and socially valued area.

Among the wide range of characteristics observed in gifted students, it is important to consider the possible coexistence of psychiatric or neurodevelopmental disorders, as well as sensory, physical, or communication disabilities—a phenomenon commonly referred to as twice-exceptionality (Foley-Nicpon & Assouline, 2020; Pfeiffer, 2013, 2015; Pfeiffer & Foley-Nicpon, 2018). These co-occurring conditions can vary significantly in severity, ranging from mild to severe (Pfeiffer, 2015). In addition to these challenges, gifted students, like their peers, often face social and emotional challenges (Pfeiffer & Stocking, 2000). In particular, asynchrony (understood as uneven intellectual, physical, social, and emotional development) may cause gifted students to perceive themselves as different or struggle to integrate with their peer group. Such experiences may, over time, negatively affect the development of their emotional intelligence (Ogurlu & Özbey, 2021).

In the scientific literature, the tools used to identify giftedness are commonly categorized into abbreviated versions of intelligence tests, as well as rating scales completed by teachers, families, and, though less frequently, by peers. However, the identification process of gifted students presents several challenges. Among these are the use of tools that lack sufficient validity and reliability, misinterpretation of assessment results, and limited coherence between identification protocols, institutional goals, and the educational services provided by schools (Lee et al., 2021). Several studies have highlighted that traditional identification protocols, primarily based on intelligence and achievement tests, are affected by biases that hinder the inclusion of students with diverse characteristics (Gentry et al., 2019; Ford et al., 2016; Naglieri & Ford, 2003, 2005). These limitations may also contribute to the underrepresentation of students from disadvantaged backgrounds (Lee et al., 2022). Learners who belong to minority groups, come from low socioeconomic contexts, or present with twice-exceptionality are frequently referred to in the literature as underrepresented students in gifted education (Arnstein et al., 2023; Baum & Olenchak, 2022; Dixson & Stevens, 2018).

Traditional giftedness identification protocols rely almost exclusively on quantitative tools, such as intelligence quotient assessments or standardized tests. These approaches often overlook the perspectives of teachers, families, peers, or other sources that could provide valuable and complementary information (Renzulli, 2011). Experts such as Carman et al. (2018) advocate for the adoption of alternative methods that promote more equitable identification, accounting for the diversity of characteristics gifted students may present. Such protocols should include evaluation by diagnostic professionals, such as psychologists or other professionals, as this would help ensure that all learners have access to comprehensive support personalized to their specific education needs (McBee et al., 2016).

Other authors such as Westberg (2012) also recommend incorporating teacher nomination into giftedness identification protocols. This approach offers several advantages, as teachers are well-positioned to observe students’ socio-emotional characteristics, as well as their academic strengths and difficulties. Teacher input should be considered during the initial stage of the identification process (Pollert, 2019; Worrell & Erwin, 2011). Overall, teacher nomination provides a valuable pathway in identifying giftedness, as it captures factors that are often overlooked by more traditional standardized tests (Westberg, 2012).

However, other studies have raised concerns about the nomination process; since gifted students are often surrounded by myths and prejudices that can hinder the identification process, it may introduce biases that compromise both the validity and equity of identification, potentially leading to the overidentification of gifted students (Bahar & Maker, 2020; Siegle et al., 2010). In their systematic review, Medina-Castro et al. (2024) highlight several of these stereotypes, including perfectionism and excessive self-demand, feelings of not belonging among peers, low frustration tolerance, social withdrawal, lack of empathy, introversion, and traits associated with neuroticism. Gifted students are also frequently perceived as socially distant, mentally unstable, or emotionally disturbed. These stereotypes are often rooted in a mismatch between the student’s cognitive abilities and their social environment, as well as in misaligned expectations from those around them, which are generally negative (Medina-Castro et al., 2024).

It is important to recognize that the prevalence of myths and prejudices surrounding giftedness limits both its identification and the implementation of effective and inclusive educational interventions for these students (Barrenetxea Mínguez & Izaguirre, 2020). For this reason, teachers require adequate training on the characteristics of giftedness to become proactive social agents in its identification (Valencia et al., 2023) These misconceptions extend beyond teachers and into the family context, as families of gifted students are often unaware of their children’s specific educational needs, and widespread societal myths surrounding giftedness can lead to misconceptions about this population (Medina-Castro et al., 2024). In contrast, families who understand the special educational needs (SENs) associated with giftedness tend to foster better academic outcomes and socio-emotional adjustment in their children (Clements & Gullo, 2016; Heller, 2016). For this reason, it is important to emphasize the role of families and to ensure they are adequately supported by the schools to participate meaningfully in the identification process (Valencia et al., 2023).

To improve inclusive identification strategies, it is essential to provide individualized and timely support that responds to the specific characteristics of each gifted student, allowing their abilities to be effectively nurtured. The absence of such differentiated strategies can lead to the development of emotional, behavioral, cognitive, and social difficulties among gifted students (Blaas, 2014; Guénolé et al., 2015).

In this regard, the present study aims to provide a comprehensive and current overview of the most effective identification protocols for detecting giftedness in primary school students. The goal is to support their implementation by both teachers and diagnostic professionals, thereby promoting the educational inclusion of as many underrepresented students as possible. More specifically, this systematic review seeks to examine, in depth, the most recent protocols, instruments, and measures used to identify giftedness at this educational level. It also aims to address the following research questions: What evidence does the scientific literature provide regarding the most effective and current tools available to teachers, families, and diagnostic professionals for identifying giftedness? Which procedures are most accurate in identifying underrepresented or twice-exceptional gifted students in primary education?

2. Materials and Methods

To obtain a current and equitable perspective on identification protocols, only studies published between 2019 and September 2024 were included. Relevant articles were identified through the PsychInfo, Web of Science, and Scopus databases. The search strategy involved three sets of keywords, which were first combined using the <<OR>> and then connected using the <<AND>>. The final search equation was (“gift” OR “high abilit*” OR “high potent*”) AND (asses* OR tool* OR question* OR test* OR batter*) AND (primar* OR child* OR infant*).

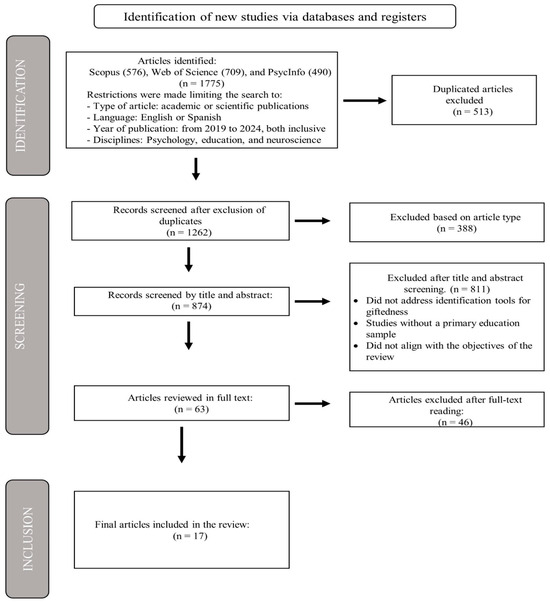

The inclusion criteria were as follows: articles published in English or Spanish, focused on disciplines such as psychology, neuroscience, educational research, family studies, and multidisciplinary fields. Both qualitative and quantitative studies were considered. Studies focusing on the identification of giftedness in adolescent populations or those not focused on identification tools were excluded. Study selection and review were carried out independently by three reviewers. As illustrated in Figure 1, the screening and selection process followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines (Page et al., 2021). In total, 17 studies that met the objectives of this systematic review were included. The review is registered in PROSPERO under registration number CRD420251064093.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of the selection process. The diagram illustrates the screening process conducted in this systematic review following the identification of studies through database research.

To complement the analysis of the selected studies, Table 1 shows the assessment of risk of bias using the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale. Of the seventeen studies analyzed, eleven were found to be of low quality, while six were rated as moderate-to-high quality. One of the items with the highest risk of bias across the included studies was the definition of control groups; only six out of the total seventeen studies provided a clear definition. The studies classified as low quality were cross-sectional and lacked both control and clinical comparison groups. Nevertheless, all of the included studies are considered valuable, as they contribute to a broader understanding of the current landscape of giftedness identification.

Table 1.

Risk of Bias.

3. Results

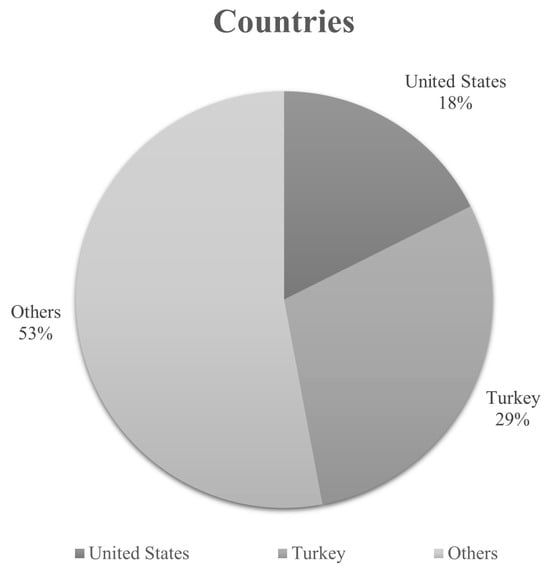

The majority of studies included in this systematic review originated from Asia, accounting for 52.9% of the total. The remaining studies are distributed across the Americas and Europe. As shown Figure 2, Turkey accounted for five articles, the United States for three, and Jordan, the Netherlands, South Korea, Iran, Italy, Brazil, Greece, Spain, and Kazakhstan each contributed one article. For analytical clarity, the protocols, instruments, and measures described in the review articles were grouped into three categories: teacher-administered screening tools, family-administered screening tools, and professionally administered assessment tools. This classification was used to support a clearer evaluation of the effectiveness of each tool, allowing teachers, families, and diagnostic professionals to select the most appropriate option during the identification process of gifted students.

Figure 2.

Distribution of articles by country. This figure shows the countries included in the studies in this systematic review.

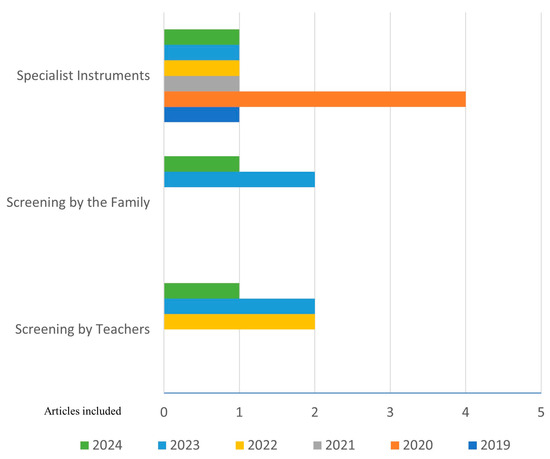

The publication years of the selected articles are presented in Figure 3, along with the number of studies categorized by type of tool. Of these, 52.9% correspond to tools designed to be used by diagnostic professionals, 17.6% by families, and 24.9% by teachers.

Figure 3.

Analysis of the results. The figure displays the selected studies by year of publication and the number of diagnostic tools used in the identification of giftedness, organized according to the person responsible for their administration.

The main finding from the studies indicates that the most effective way to identify underrepresented or twice-exceptional gifted students is through the use of multiple diagnostic tools (Sofologi et al., 2023; Lee et al., 2022; S. M. Wechsler et al., 2022; Silverman & Gilman, 2020; Callahan et al., 2022; Carman et al., 2020; Erden et al., 2020; Aydin-Karaca et al., 2024). The selection of identification protocols should consider not only students’ cognitive patterns but also their developmental history, with an emphasis on reasoning rather than processing skills (Silverman & Gilman, 2020). Table 2 presents an analysis of the key findings from the studies included in this systematic review.

Table 2.

Main objectives and findings of the selected studies.

3.1. Screening Tools for Families

Family involvement is a key component in the accurate identification of giftedness, as it contributes to a more holistic understanding of the student. In their study, Karaca and Kılınc (2023) validated the Short-Form Parent Rating Scale (SFPRS), indicating that parents, when equipped with an appropriate instrument, are often able to recognize gifted traits in their children with notable accuracy. The authors argue that parental insights can be both reliable and informative and, in some cases, may introduce fewer biases than teacher-based assessments.

Furthermore, Aydin-Karaca et al. (2024) developed the Parent Rating Scale for Gifted Students (PRSC), which may contribute robust data on the distinctive characteristics of gifted students, improving identification accuracy. The scale is grounded in a theoretical framework linked to practical intelligence and offers additional advantages in terms of applicability.

Tourón et al. (2023), in their validity study of the Gifted Rating Scales (GRS-2) originally developed by Pfeiffer and Jarosewich (2007), highlight the critical role of families in identifying giftedness. Parents provide crucial contextual information that teachers and diagnostic professionals should take into account. Their validation study demonstrates that the GRS-2 enables accurate assessment of socioemotional competencies, aiding in the identification of diverse giftedness characteristics. The authors’ findings suggest that the GRS-2 is highly valuable for educational practice in Spain, given the scarcity of validated assessment tools. However, they emphasize the need for further confirmatory studies.

3.2. Teacher Screening Tools

Callahan et al. (2022) demonstrated that teacher nominations failed to reliably predict successful giftedness identification. Despite these findings, the authors stress that teachers still play a critical role in the process. Notably, their study revealed a gender disparity, as teachers were significantly more likely to nominate boys than girls for creativity-based giftedness.

The Having Opportunities Promotes Excellence (HOPE) Scale (Gentry et al., 2015) is a teacher-completed tool designed to identify gifted students from diverse sociocultural backgrounds. Lee et al. (2022) found this scale particularly effective for identifying underrepresented students, as teachers evaluate candidates using both academic and social behaviors demonstrated in classroom settings. This approach leads to more equitable identification compared to traditional assessment tools (Lee et al., 2022). The authors further revealed that primary school teachers find it easier to recognize giftedness manifested through mathematical and calculation skills than through reading abilities.

The Gifted and Talented Evaluation Scale (GATES-2; Gilliam et al., 1996) is a teacher-completed tool used in the nomination process for giftedness. In their study of the Italian adaptation of GATES-2, Di Renzo et al. (2022) found that this instrument effectively differentiates between students with high and low ability levels. The authors further emphasize the importance of accounting for sociocultural biases that may affect the accurate identification of diverse giftedness profiles, as well as the unique characteristics of these students.

In their study aimed at optimizing child assessment through an integrated cognitive approach, S. M. Wechsler et al. (2022) developed the Intellectual and Creative Assessment Battery (BAICI), adapted from the adult version (Adult Intellectual Assessment Battery; BAIAD; S. M. Wechsler et al., 2022). The BAICI integrates measurements of both intelligence and creativity.

Results indicate that this battery enables a more comprehensive identification approach to childhood cognitive abilities. However, while the authors observed a correlation between intelligence and creativity, this association did not reach statistical significance. Consequently, S. M. Wechsler et al. (2022) emphasize the need to evaluate these constructs independently to achieve a holistic understanding of children’s cognitive functioning.

Biber et al. (2021) examined the relationship between teacher nominations and identification results from Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices (RSPM; Raven, 2003) in assessing giftedness. Their findings reveal that while teachers were unsuccessful in accurately nominating gifted students, they demonstrated better accuracy in identifying non-gifted students. The authors suggest that this discrepancy may stem from either a misalignment between teachers’ nomination criteria and the RSPM’s standardized measures or the potential influence of sociocultural biases in the nomination process.

Sofologi et al. (2023), in their validation study of the GRS-S in Greece, argue that this tool fosters a strong connection between assessment and the identification of giftedness. It is designed to capture multiple giftedness profiles across six domains, (a) intellectual ability, (b) academic achievement, (c) creativity, (d) artistic talent, (e) leadership, and (f) motivation, each grounded in contemporary theoretical models of giftedness. By considering all these domains, teachers are better equipped to understand the unique characteristics of each gifted student throughout the identification process.

The GCIS (Mambetalina et al., 2024), developed in Kazakhstan, assesses giftedness across four key areas: contextual, intellectual, creative, and social domains. This scale was designed to enable teachers to identify diverse manifestations of giftedness beyond general cognitive ability (Mambetalina et al., 2024). This scale was designed to enable teachers to identify diverse manifestations of giftedness beyond general cognitive ability (Mambetalina et al., 2024).

3.3. Tools Administered by Diagnostic Professionals

The Cognitive Abilities Test (CogAT; Lohman, 2011) is a standardized psychometric assessment designed to evaluate cognitive abilities related to academic performance. According to Callahan et al. (2022), this test has been successfully used in educational settings for giftedness identification. It measures key competencies including verbal reasoning, linguistic comprehension, and semantic relations skills, all critical foundations for literacy development, particularly in reading and writing. The verbal battery includes tasks such as analogies, sentence completion, and verbal classification, focusing on students’ ability to process, generalize, and apply linguistic information in abstract contexts. However, despite its effectiveness, relying solely on the CogAT for gifted identification results in underrepresentation of gifted students (Callahan et al., 2022).

Silverman and Gilman (2020) caution against using the Full-Scale IQ scores as the sole identification criterion, instead advocating for the use of any one of the six expanded index scores assessed by the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children—Fifth Edition (WISC-V; D. Wechsler, 2014), which are considered more suitable measures for gifted students with asynchronous development.

In line with this approach, Öpengin and Bal Sezerel (2023) report that the use of the WISC-IV to identify gifted students produces highly reliable results in distinguishing between students with and without giftedness.

The same authors examined the Anadolu-Sak Intelligence Scale (ASIS; Sak et al., 2019), which was developed specifically to identify giftedness while addressing the limitations of traditional identification protocols. Their findings suggest that the ASIS demonstrates adequate reliability in identifying both gifted students and those with twice-exceptionalities, while also recognizing the heterogeneous nature of giftedness.

In their comparative study of the Naglieri Nonverbal Ability Test (NNAT; Naglieri, 2008) and the CogAT7, Carman et al. (2020) report that the NNAT was less effective in identifying certain underrepresented student groups, whereas the CogAT7 demonstrated greater sensitivity in detecting giftedness among these populations. Despite these findings, both tools showed a limited capacity to identify historically underrepresented students when compared to their overrepresented peers. Furthermore, the authors note that the NNAT exhibited a higher tendency to produce false positives for giftedness than the CogAT7.

The use of the RSPM in the identification of giftedness is considered by Vogelaar et al. (2020) to be a robust and reliable tool. It is also regarded as less biased toward students from diverse sociocultural backgrounds. The RSPM assesses two distinct cognitive processes, abstract reasoning and fluid intelligence. In a related study, Biber et al. (2021) found that the RSPM more accurately identified giftedness than teacher nominations.

Dynamic assessments provide additional insights into students’ cognitive potential. They have also proven effective in reducing performance differences among various types of cognitive profiles, highlighting the value of dynamic training in uncovering individual abilities (Vogelaar et al., 2020). Similarly, Teymoori Pabandi et al. (2024) argue that combining elements such as problem-solving, reading comprehension, and scientific reasoning with the CogAT enhances the identification of science-related talent in primary education. They also report a strong correlation between academic performance and CogAT scores, underscoring the value of this tool in the identification process for giftedness.

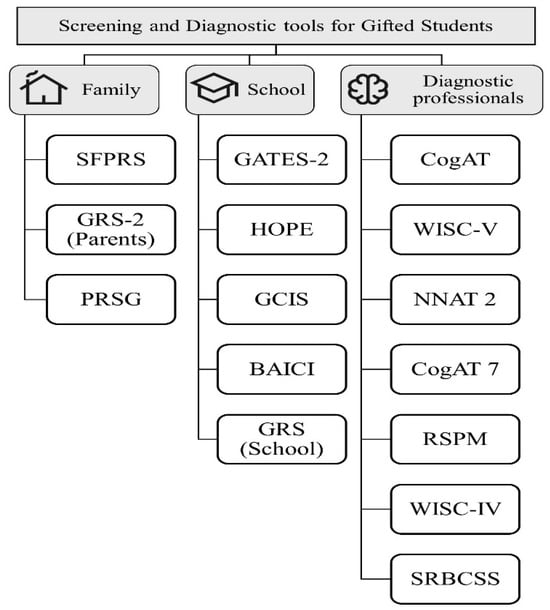

Figure 4 provides a visual synthesis of the screening and diagnostic tools identified in this systematic review, categorized according to their primary users—families, teachers, and diagnostic professionals. This classification illustrates the diversity of instruments available and the multi-informant approach in the identification of giftedness.

Figure 4.

Screening and diagnostic tools for gifted students categorized by user. The tools included in the figure are as follows: Gifted and Talented Evaluation Scales, Second Edition (GATES-2); Having Opportunities Promotes Excellence Scale (HOPE); Gifted Characteristics Identification Scale (GCIS); Battery for Intellectual and Creative Assessment—Child Version (BAICI); Gifted Rating Scales—School Form (GRS-S); Short-Form Parent Rating Scale (SFPRS); Gifted Rating Scales—Parent Form (GRS-2); Parental Rating Scale for Giftedness (PRSG); Nonverbal Cognitive Abilities Test (CogAT); Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fifth Edition (WISC-V); Naglieri Nonverbal Ability Test, Second Edition (NNAT 2); Nonverbal Battery of the Cognitive Abilities Test, Seventh Edition (CogAT7); Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices (RSPM); Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition (WISC-IV); Scales for Rating the Behavioral Characteristics of Superior Students (SRBCSS); and the Verbal Battery of the Cognitive Abilities Test (CogAT-V).

4. Discussion

The objective of this systematic review was to analyze the most recent protocols, tools, and measures used to identify giftedness in primary school students. The findings from the articles included in the review, published over the past five years and retrieved from the three databases previously mentioned, highlight the complexity of the identification process. This complexity is largely due to the heterogeneous profiles associated with giftedness, particularly in culturally and socioeconomically diverse contexts. One of the main challenges in this process lies in the gap between the different theories on giftedness and educational practice (Siegle et al., 2024).

This review emphasizes the importance of involving all relevant informants (teachers, families, and diagnostic professionals) in the identification of giftedness. The first two groups provide important information that should be considered by diagnostic professionals such as psychologists, as it complements and enriches the overall process.

In line with the findings of Acar et al. (2016), McBee et al. (2014), and McGowan et al. (2016), the identification of giftedness should consider not only students’ cognitive profiles but also their individual developmental and socio-educational trajectories.

Regarding teacher nominations, the findings acknowledge the fundamental role of educators in the identification process, as they are often able to recognize specific traits in students that may facilitate the inclusion of underrepresented and twice-exceptional gifted students. This aligns with the results reported by Foley-Nicpon et al. (2012) and Almeida et al. (2016). However, teacher nominations may introduce bias due to the persistence of misconceptions or myths surrounding giftedness, particularly when teachers lack adequate training, a concern supported by recent studies (Medina-Castro et al., 2024; Bahar & Maker, 2020; Siegle et al., 2024).

Parental nominations also proved to be highly valuable in the identification process of giftedness, especially considering the importance of integrating the student’s family context. This finding is consistent with the work of Marsili and Pellegrini (2022). As with teachers, however, the effectiveness of family input depends on mitigating the influence of myths and preconceived notions about the characteristics of giftedness.

Regarding the identification of underrepresented students, the HOPE Scale has proven to be effective, provided that sociocultural factors and potential teacher biases are also considered (Lee et al., 2022). Similarly, the BAICI offers a comprehensive approach to assessing both intelligence and creativity. The CogAT also demonstrates strong effectiveness in identifying giftedness, particularly when verbal and reasoning abilities are considered (Carman et al., 2020). However, it is important to note that when used in isolation, this tool tends to under identify gifted students.

This systematic review underscores the importance of using the expanded index scores of the WISC-V instead of the Full-Scale IQ, in order to achieve more equitable identification in diverse contexts. The ASIS, in turn, has demonstrated advantages by overcoming the limitations of traditional protocols and offering more accurate identification of students with giftedness or twice-exceptionality. The CogAT7 shows greater sensitivity in identifying underrepresented groups, making it a valuable tool in schools with greater sociocultural diversity in their student populations. This review also confirms the robustness of the RSPM in identifying giftedness, despite the inherent limitations of static tests, as it accounts for the diversity of cognitive profiles.

In contrast, dynamic assessment tools offer a more nuanced understanding of the potential of gifted students. They not only allow for a better grasp of student performance under guided conditions but also help narrow the gap between different cognitive profiles. As such, they can be considered one of the most promising alternatives for achieving a more inclusive diagnostic assessment.

The results of this review align with those of Erden et al. (2020), who point out the need for further studies that explore gifted student profiles through a more cohesive analysis of theoretical frameworks.

Practical Implications

This review compiles data from current research on the identification of giftedness and clearly highlights the need to use multiple tools to ensure an effective diagnostic process, as well as the most feasible approaches to avoid the underrepresentation of gifted students. In educational practice, having a reference of reliable tools available for use in the identification process would not only enhance the preparedness of teachers, families, and diagnostic professionals but also promote a more equitable identification of giftedness by considering students’ diverse cognitive profiles and the presence of twice-exceptionality.

5. Conclusions

This study confirms the need for identification protocols for giftedness that move beyond traditional approaches. It is essential to incorporate a balanced combination of standardized and dynamic assessments, qualified nominations, and developmental backgrounds. Identifying gifted students requires a complex, multidimensional approach that includes underrepresented and twice-exceptional learners, ensuring that their special educational needs are properly addressed. The exclusive use of traditional psychometric tests has proven insufficient and may be discriminatory in contexts characterized by high cognitive and sociocultural diversity.

Accurate identification of giftedness requires assessment practices that prioritize reasoning and learning potential over the measurement of crystallized abilities (such as acquired knowledge or academic skills). It is essential to raise awareness among educational stakeholders about the potential biases embedded in nomination processes, ensuring that all student profiles, including underrepresented and twice-exceptional learners, are appropriately identified and supported. To achieve this, further research is needed on teacher nominations as a key component in the identification of underrepresented gifted students.

Limitations

It is important to consider that this review presents certain limitations related to aspects such as the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies involving adolescent and early childhood samples were excluded, even though identification protocols for giftedness also exist in these age groups and could have enriched educational practice.

By selecting only three databases, relevant studies outside this selection may have been missed, particularly those published in gray literature or in sources without open access. Studies published in languages other than English and Spanish were also excluded, which may have introduced specific language bias.

The methodological quality of the selected studies, assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale, showed that 65% of the included articles were of low quality. Most of the selected studies focused on the validation of a single instrument. No studies were found in which different authors evaluated the same tool, which could lead to biases in the validity of these identification instruments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.D.-V., B.D., and I.N.-S.; methodology, L.D.-V., M.T., and I.N.-S.; software, L.D.-V., M.T., and M.R.-G.; validation, L.D.-V., B.D.; formal analysis, L.D.-V., M.T., M.d.l.C.S.-H., and I.N.-S.; investigation, L.D.-V., M.T., B.D., and I.N.-S.; resources, M.S.-D., I.N.-S. and M.R.-G.; data curation, L.D.-V., M.T., M.R.-G., and I.N.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.D.-V., M.d.l.C.S.-H.; writing—review and editing, L.D.-V., M.T., I.N.-S., and M.R.-G.; visualization, L.D.-V., I.N.-S.; supervision, B.D., M.S.-D.; project administration, B.D., I.N.-S.; funding acquisition, L.D.-V., B.D., M.S.-D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Habana Project at the University of Alicante through a scholarship awarded to the first author. The Habana Project had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of data, the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Acar, S., Sen, S., & Cayirdag, N. (2016). Consistency of the performance and nonperformance methods in gifted identification. Gifted Child Quarterly, 60(2), 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, L. S., Araújo, A. M., Sainz-Gómez, M., & Prieto, M. D. (2016). Challenges in the identification of giftedness: Issues related to psychological assessment. Anales de Psicologia, 32(3), 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alodat, A. M., & Zumberg, M. F. (2019). Using a nonverbal cognitive abilities screening test in identifying gifted and talented young children in Jordan: A focus group discussion of teachers. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 42(3), 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, K. B., Desmet, O. A., Seward, K., Traynor, A., & Olenchak, F. R. (2023). Underrepresented students in gifted and talented education: Using positive psychology to identify and serve. Education Sciences, 13(9), 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin-Karaca, S., Köksal, M. S., & Bi, B. (2024). Adaptation and development of parent rating scale for giftedness. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 42(7), 813–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, A. K., & Maker, C. J. (2020). Culturally responsive assessments of mathematical skills and abilities: Development, field testing, and implementation. Journal of Advanced Academics, 31(3), 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrenetxea Mínguez, L., & Izaguirre, M. M. (2020). Relevancia de la formación docente para la inclusión educativa del alumnado con altas capacidades intelectuales. Atenas: Revista Científico Pedagógica, 1(49), 1–19. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/dcart?info=link&codigo=8771544&orden=0 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Baum, S., & Olenchak, R. (2022). Twice-exceptional students: Ameliorating an educational dilemma. In Creating equitable services for the gifted: Protocols for identification, implementation, and evaluation (pp. 20–38). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Biber, M., Biber, S. K., Ozyaprak, M., Kartal, E., Can, T., & Simsek, I. (2021). Teacher nomination in identifying gifted and talented students: Evidence from Turkey. Thinking Skills And Creativity, 39, 100751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaas, S. (2014). The Relationship Between Social-Emotional Difficulties and Underachievement of Gifted Students. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 24(2), 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, C. M., Azano, A., Park, S., Brodersen, A. V., Caughey, M., & Dmitrieva, S. (2022). Consequences of implementing curricular-aligned strategies for identifying rural gifted students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 66(4), 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carman, C. A., Walther, C. A. P., & Bartsch, R. A. (2018). Using the cognitive abilities test (CogAT) 7 nonverbal battery to identify the gifted/talented: An investigation of demographic effects and norming plans. Gifted Child Quarterly, 62(2), 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carman, C. A., Walther, C. A. P., & Bartsch, R. A. (2020). Differences in using the cognitive abilities test (CogAT) 7 nonverbal battery versus the naglieri nonverbal ability test (NNAT) 2 to identify the gifted/talented. Gifted Child Quarterly/The Gifted Child Quarterly, 64(3), 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, D. H., & Gullo, D. F. (2016). Parents’ beliefs about the development of early numeracy. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 37, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Di Renzo, M., Bianchi di Castelbianco, F., Sartori, L., Venturini, G., Landi, M., Racinaro, L., Ciancaleoni, M., & Rea, M. (2022). Gifted students in Italy and GATES-2. TPM, 29(2), 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson, D. D., & Stevens, D. (2018). A potential avenue for academic success: Hope predicts an achievement-oriented psychosocial profile in African American adolescents. Journal of Black Psychology, 44(6), 532–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erden, G., Yiğit, İ., Çelik, C., & Guzey, M. (2020). The diagnostic utility of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Fourth Edition (WISC-IV) in identification of gifted children. The Journal of General Psychology, 149(3), 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, E., García, T., Arias-Gundín, O., Vázquez, A., & Rodríguez, C. (2017). Identifying gifted children: Congruence among different IQ measures. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley-Nicpon, M., & Assouline, S. G. (2020). High ability students with coexisting disabilities: Implications for school psychological practice. Psychology in the Schools, 57(10), 1615–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley-Nicpon, M., Rickels, H., Assouline, S. G., & Richards, A. (2012). Self-esteem and self-concept examination among gifted students with ADHD. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 35(3), 220–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, D. Y., Wright, B. L., Washington, A., & Henfield, M. S. (2016). Access and equity denied: Key theories for school psychologists to consider when assessing black and Hispanic students for gifted education. In School psychology forum (Vol. 10). National Association of School Psychologists. [Google Scholar]

- Gagné, F. (2004). Transforming gifts into talents: The DMGT as a developmental theory1. High Ability Studies, 15(2), 119–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, M., Gray, A. M., Whiting, G. W., Maeda, Y., & Pereira, N. (2019). Educación para superdotados en Estados Unidos: Leyes, acceso, equidad y falta de acceso en todo el país por localidad, estatus escolar de Título I y raza. Fundación Jack Kent Cooke y Fundación de Investigación de Purdue. Available online: https://www.education.purdue.edu/geri/new-publications/gifted-education-in-the-united-states/ (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Gentry, M., Pereira, N., Peters, S. J., McIntosh, J. S., & Fugate, C. M. (2015). Manual de administración de la escala de calificación docente HOPE. Prufrock Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam, J. E., Carpenter, B. O., & Christensen, J. R. (1996). Gifted and talented evaluation scales (GATES). PRO-ED. [Google Scholar]

- Guénolé, F., Speranza, M., Louis, J., Fourneret, P., Revol, O., & Baleyte, J. (2015). Wechsler profiles in referred children with intellectual giftedness: Associations with trait-anxiety, emotional dysregulation, and heterogeneity of Piaget-like reasoning processes. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology, 19(4), 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, G. E., & Van Haneghan, J. P. (2011). The gifted and the shadow of the future: Globalization and the needs of 21st century skills. Roeper Review, 33(4), 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, K. A. (2016). Parents’ beliefs about the gifted: Review and interpretation of research. In Handbook of giftedness in children (2nd ed., pp. 71–88). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Karaca, S. A., & Kılınc, S. (2023). Development of the short-form parent rating scale (SFPRS) for screening gifted children. Kliničeskaâ I Specialʹnaâ Psihologiâ, 12(4), 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H., Karakis, N., Akce, B. O., Tuzgen, A. A., Karami, S., Gentry, M., & Maeda, Y. (2021). A meta-analytic evaluation of naglieri nonverbal ability test: Exploring its validity evidence and effectiveness in equitably identifying gifted students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 65(3), 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H., Seward, K., & Gentry, M. (2022). Equitable identification of underrepresented gifted students: The relationship between students’ academic achievement and a teacher-rating scale. Journal of Advanced Academics, 33(3), 400–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohman, D. F. (2011). Cognitive abilities test, form 7. Riverside. [Google Scholar]

- Mambetalina, A., Lawrence, K., Amangossov, A., Mukhambetkalieva, K., & Demissenova, S. (2024). Giftedness characteristic identification among Kazakhstani school children. Psychology in the Schools, 61(6), 2589–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsili, F., & Pellegrini, M. (2022). The relation between nominations and traditional measures in the gifted identification process: A meta-analysis. School Psychology International, 43(4), 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBee, M. T., Peters, S. J., & Miller, E. M. (2016). The impact of the nomination stage on gifted program identification. Gifted Child Quarterly, 60(4), 258–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBee, M. T., Peters, S. J., & Waterman, C. (2014). Combining scores in multiple-criteria assessment systems: The impact of combination rule. Gifted Child Quarterly, 58(1), 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, M. R., Holtzman, D. R., Coyne, T. B., & Miles, K. L. (2016). Capacidad predictiva del coeficiente intelectual compuesto SB5 para superdotados frente al coeficiente intelectual completo en niños derivados para evaluaciones de superdotados. Roeper Review, 38, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Castro, M., Abín, A., & Fernández, E. (2024). Concepción de las Familias y la Escuela Sobre las Altas Capacidades: Una Revisión Sistemática. Revista de Psicología y Educación—Journal of Psychology and Education, 19(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naglieri, J. A. (2008). Naglieri nonverbal ability test: Multilevel form technical report. Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Naglieri, J. A., & Ford, D. Y. (2003). Addressing underrepresentation of gifted minority children using the naglieri nonverbal ability test (NNAT). Gifted Child Quarterly, 47(2), 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naglieri, J. A., & Ford, D. Y. (2005). Increasing minority children’s participation in gifted classes using the NNAT: A response to Lohman. Gifted Child Quarterly, 49(1), 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Association for Gifted Children. (2019). A definition of giftedness that guides best practice. National Association for Gifted Children. Available online: https://www.nagc.org/what-is-giftedness (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Ogurlu, U., & Özbey, A. (2021). Personality differences in gifted versus non-gifted individuals: A three-level meta-analysis. High Ability Studies, 33(2), 227–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öpengin, E., & Bal Sezerel, B. (2023). Los perfiles cognitivos de los niños superdotados: A latent profile analysis using the ASIS. Revista de Investigación Pedagógica, 7(4), 400–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Alonso-Fernández, S. (2021). Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Revista Española de Cardiología, 74(9), 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasarín-Lavín, T., Rodríguez, C., & García, T. (2021). Conocimientos, percepciones y actitudes de los docentes hacia las altas capacidades. Revista de Psicología y Educación—Journal of Psychology and Education, 16(2), 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyre, H., Ramus, F., Melchior, M., Forhan, A., Heude, B., & Gauvrit, N. (2016). Emotional, behavioral and social difficulties among high-IQ children during the preschool period: Results of the EDEN mother–child cohort. Personality and Individual Differences, 94, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, S. I. (2013). Serving the gifted. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, S. I. (2015). Essentials of gifted assessment. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, S. I., & Foley-Nicpon, M. (2018). Knowns and unknowns about students with disabilities who also happen to be intellectually gifted. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, S. I., & Jarosewich, T. (2007). The gifted rating scales-school form: An analysis of the standardization sample based on age, gender, race, and diagnostic efficiency. Gifted Child Quarterly, 51(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, S. I., & Stocking, V. (2000). Vulnerabilities of academically gifted students. Special Services in the Schools, 16, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollert, E. (2019). Advantages and disadvantages of using multiple forms of assessment to identify gifted and talented students in North Dakota. Minot State University. [Google Scholar]

- Raven, J. (2003). Raven progressive matrices. In R. S. McCallum (Ed.), Handbook of nonverbal assessment (pp. 223–237). Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzulli, J. S. (2011). What makes giftedness? Reexamining a definition. Phi Delta Kappan, 92(8), 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sak, U., Sezerel, B. B., Dulger, E., Sozel, K., & Ayas, M. B. (2019). Validity of the Anadolu-Sak Intelligence Scale in the identification of gifted students. Psychological Test and Assessment Modeling, 61(3), 263–283. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, C., Brigaud, E., Moliner, P., & Blanc, N. (2022). The Social Representations (SRs) of Gifted Children in childhood professionals and the general adult population in France. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 45(2), 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegle, D., Hook, T. S., & Wright, K. J. (2024). Confronting the gordian knot: Disentangling gifted education’s major issues. Gifted Child Quarterly, 68(3), 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegle, D., Moore, M., Mann, R. L., & Wilson, H. E. (2010). Factors that influence in-service and preservice teachers’ nominations of students for gifted and talented programs. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 33(3), 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, L. K., & Gilman, B. J. (2020). Best practices in gifted identification and assessment: Lessons from the WISC-V. Psychology in the Schools, 57(10), 1569–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofologi, M., Papantoniou, G., Avgita, T., Dougali, A., Foti, T., Geitona, A., Lyraki, A., Tzalla, A., Staikopoulou, M., Zaragas, H., Ntritsos, G., Varsamis, P., Staikopoulos, K., Kougioumtzis, G., Papantoniou, A., & Moraitou, D. (2023). The Gifted Rating Scales—School Form in Greek elementary and middle school learners: A closer insight into their psychometric characteristics. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1198119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teymoori Pabandi, S., Abdullah Mirzaie, R., Atabakhsh, M., & Asfa, A. (2024). The identification of primary school students who are gifted in science. Gifted and Talented International, 39(1), 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourón, M., Navarro-Asencio, E., & Tourón, J. (2023). Validez de Constructo de la Escala de Detección de alumnos con Altas Capacidades para Padres, Parent Gifted Rating Scales (GRS 2), en España. Revista De Educación, 1(402), 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, L. D., De Jesús Soto Diaz, M., & De la Caridad Sánchez Herrera, M. (2023). El licenciado en Pedagogía-Psicología en la atención al educando talento académico y a su familia. Dialnet. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=9353896 (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Vogelaar, B., Resing, W. C. M., & Stad, F. E. (2020). Dynamic testing of children’s solving of analogies: Differences in potential for learning of gifted and average-ability children. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 19(1), 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, D. (2014). Wechsler intelligence scale for children (5th ed.). NCS Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, S. M., Virgolim, A. M. R., Paludo, K. I., Dantas, I., Mota, S. P., & Minervino, C. A. M. (2022). Integrated assessment of children’s cognitive and creative abilities: Psychometric studies. Psico-USF, 27(4), 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westberg, K. L. (2012). Using teacher rating scales to identify students for gifted education services. In S. L. Hunsaker (Ed.), Identification: Theory and practice of identifying students for gifted and talented education services (pp. 363–379). Prufrock Press. [Google Scholar]

- Worrell, F. C., & Erwin, J. O. (2011). Best practices for identifying students for gifted and talented education programs. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 27, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).