Abstract

Inclusive education continues to face significant challenges nowadays due to a lack of resources, specialized support, and teacher training. In the context of primary education in Europe, families of students with functional diversity express their concern about the lack of adequate responses to their needs. However, there are merely a few studies that delve into the reality of inclusion from the family perspective. Therefore, this study aims to analyze the perceptions of families of students with functional diversity in Extremadura (Spain), regarding the quality of the educational response offered by schools. For this purpose, the study sample consisted of 70 family members of students with functional diversity in this region. For data collection and analysis, a semi-structured interview was used, applying thematic analysis and chi-square statistical tests in order to explore significant differences in the perceptions gathered. The interviews were transcribed and the answers gathered were categorized. The results show that almost half of the families consider the information received about the disability and the progress of their relatives to be insufficient. Likewise, there is a low level of satisfaction with the support and resources provided by both associations and the public administration. Consequently, the need to strengthen effective communication between schools and families is highlighted as a fundamental pillar to advance toward true educational inclusion.

1. Introduction

A great amount of progress is currently being made when it comes to granting the right to equal opportunities in educational institutions within the Spanish context. This progress is supported by regulatory frameworks such as the LOMLOE (2020), which establishes clear principles for inclusive education, and by pedagogical approaches such as Universal Design for Learning (UDL), which promote accessibility and participation for all students. Furthermore, these advances are part of Sustainable Development Goal No. 4 of the 2030 Agenda, which calls for ensuring inclusive, equitable, and quality education, as well as promoting lifelong learning opportunities for all (UNESCO, 2015). In this vein, authors such as Ainscow (2020) and Ossai (2022) emphasize that paying attention to students with special needs should be a structural priority in educational systems. However, certain barriers persist despite advances in educational policies and the development of curricular and pedagogical actions aimed at promoting such inclusion (Maqueira et al., 2023).

In this context, families play a fundamental role in the success of educational inclusion, as their involvement and satisfaction directly influence school adaptation, the quality of social relationships developed by students with functional diversity, and their emotional and physical well-being (Sánchez, 2020). UNESCO (1994) already recognized the importance of family participation as a key factor in promoting inclusive and effective school environments. Similarly, Booth and Ainscow (2015) emphasize the need to design programs that encourage the active and sustained participation between family and institutions, understanding this relationship as an essential pillar for student development and the promotion of inclusion (Sánchez, 2020). However, this cooperation continues to face challenges in terms of equity and democratic participation (Collet-Sabé, 2020). For example, Sakamoto (2021) warns that the mere involvement of families in school management does not guarantee academic improvements for students with special needs and may even have counterproductive effects. What is truly important is that schools make a genuine commitment to family participation, promoting spaces for dialogue and authentic collaboration. Therefore, a key question arises: Is the degree of satisfaction of families with children with functional diversity regarding the educational response they receive well known by these institutions and taken into account accordingly?

2. Literature Review

Various studies have addressed family perceptions of inclusion and educational responses aimed at SEN students (Escobedo-Peiro et al., 2021; López & Carmona, 2018; Paseka & Schwab, 2020; Rodríguez Gudiño et al., 2023; Sahin, 2019; Sepúlveda Opazo & Castillo Armijo, 2021). The findings of Woods et al. (2018) show that families who actively collaborate with educational centers have higher levels of satisfaction. This structured and sustained collaboration is revealed as a valuable element in improving the educational experience of these students (Pérez-Vera et al., 2024). In addition, it is observed that teachers in the early stages of education tend to maintain more fluid communication with families (Paseka & Schwab, 2020).

Likewise, the educational level of families influences their attitude toward inclusion: those with higher levels of education tend to show greater willingness and positive expectations (López & Carmona, 2018). For these families, successful integration depends as much on the attitude and motivation of the students themselves as on the commitment of teachers and the support of the educational community in general (Sahin, 2019). However, there are areas for improvement, especially with regard to guidance for learning at home and the assessment of academic progress, which tend to receive negative evaluations. Regarding the role of management teams, Crisol-Moya et al. (2022) indicate that their role is decisive in promoting inclusion, highlighting the need for greater involvement and collaboration with families. Along the same lines, Rojas Fabris et al. (2021) highlight the importance of ongoing training for management teams to strengthen inclusion, improve the provision of educational resources, and reformulate the prevailing assessment systems.

Taking a holistic perspective, Moriña (2020) proposes integrating beliefs, knowledge, designs, and actions into teaching, while also incorporating the voice of students in educational improvement processes. In family–school interaction, Schenker et al. (2017) identify barriers such as unrealistic expectations and parental stress, but also highlight positive values such as cooperation and professional respect. For their part, Gokalp et al. (2021) point out that, although many teachers blame families for low collaboration, they also recognize that the lack of teacher involvement is a limiting factor. Similarly, Gento (2007) concludes that school–family collaboration has a positive impact on family well-being and student development. These types of links help to overcome school barriers and consolidate more inclusive educational environments (Gokalp et al., 2021; González-Gil et al., 2019).

The choice of school by families with children with functional diversity is influenced by multiple factors. Domingo et al. (2010) highlight that they particularly value teacher training, openness to collaboration, and the quality of information they receive from schools. According to Benítez (2014), 25.1% of families prioritize the availability of human and material resources, 20.1% are guided by recommendations from other families, and 17.6% consider it important for their children to be able to attend the same school as their siblings. Likewise, 54.3% prefer public schools, compared to nearly 30% who opt for charter schools.

From the teachers’ perspective, the difficulties in improving the educational response to diversity are mainly attributed to insufficient specialized training. Gento (2007) points out that 66% of teachers specializing in inclusive education acknowledge problems in adapting to the needs of a high number of SEN students. This situation is exacerbated by the shortage of specialists, noted by 39% of the teachers surveyed, although 34% explicitly support the inclusive model (Cornejo, 2017; Pérez-Vera et al., 2024).

In terms of methodological practices, Sandoval and Waitoller (2022) emphasize that effective inclusion requires building on students’ prior knowledge, promoting active participation, and using formative assessment as a tool for continuous improvement. Authors such as Fernández Batanero and Benítez Jaén (2016) and Sharma and Jacobs (2016) underscore the importance of the teacher’s approach to the conception and assessment of diversity. Muntaner-Guasp et al. (2022) show that active methodologies promote inclusion and professional development among teachers, as well as stimulating reflection on the presence, participation, and learning of students with specific educational needs.

Although digital technologies are present in schools, their pedagogical integration remains uneven (Pardo-Baldoví et al., 2022). To promote real inclusion, innovation must be geared toward teacher training and technological adaptation to diverse needs. Travert and Sanahuja (2022) propose training through action research as a way to transform educational practice and reduce barriers. For their part, Pla-Viana and Villaescusa (2021) note that many teachers express concern about inclusion and demand ongoing training to adapt resources, manage collaboratively, and create favorable conditions for its effective development (Sanahuja et al., 2022).

In this regard, Pérez-Vera et al. (2024) highlight that there are still significant gaps in the initial and continuing training of teachers in diversity, which limits the effective implementation of inclusive measures (UNESCO, 2021). Added to these limitations are the shortage of specialized professionals (Díaz et al., 2019; Fernández et al., 2021) and the lack of coordination between support teachers and regular teachers (Abellán-Rubio et al., 2021). Ainscow (2012) warns that in order to achieve effective inclusion, it is essential to increase human resources and have teaching staff trained in diversity, since otherwise good intentions can lead to subtle forms of exclusion (Pérez-Vera et al., 2024).

3. Aims and Research Questions

As discussed in the previous section, numerous studies have explored the perceptions of families of students with functional diversity regarding educational inclusion. However, most of them use questionnaires as their main instrument, while interview-based research tends to be performed on small samples. Therefore, this study seeks to delve deeper into the experiences and assessments of families regarding inclusive practices in educational centers, recognizing them as key actors in the educational process. The overall objective of this research is to understand the quality of the educational response offered to students with functional diversity from the family’s perspective. To this end, the following research questions are posed:

- RQ1: How do families perceive and value the accompaniment, communication, and support their children receive in schools?

- RQ2: From the family’s experience, what are the main obstacles and shortcomings that hinder the achievement of effective educational inclusion?

- RQ3: What is the emotional impact and psychological well-being of families in relation to educational inclusion and associated experiences of discrimination?

- RQ4: How do families value the information and support they receive in areas complementary to the educational center, such as employment, leisure, and the family environment?

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Participants

The participants were a total of 70 family members of primary school students with functional diversity belonging to associations in the Autonomous Community of Extremadura. The subjects were selected using non-probabilistic convenience sampling. This was the method selected due to the fact that the selection of participants was based on their availability, accessibility, and willingness to participate in the study. This type of sampling is common in qualitative and exploratory research, especially when the aim is to gain a deeper insight into the perceptions of a specific group—in this case, family members with direct experience in inclusive educational settings.

4.2. Interview Instruments and Procedure

Once the centers for students with functional diversity had been selected, a visit was made to explain the purpose of the study, request collaboration, and schedule interviews with the families. They were asked about their willingness to participate in order to learn about their perception of the quality of inclusion in these centers. They were also asked for their informed consent to participate and for the interviews to be recorded, guaranteeing anonymity and confidentiality of the information collected at all times.

A semi-structured interview designed on the basis of relevant previous studies was used for data collection. Although numerous previous studies that used questionnaires as their main tool were reviewed and considered as potential guidelines for this research, the data collection instrument in this case consisted exclusively of a semi-structured interview with nine open-ended questions. In particular, the work of Sánchez-Pujalte et al. (2020), which applied a questionnaire of 26 items grouped into three dimensions with high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.97), was taken as a reference. Some of the items included were “Do you feel that you have been sufficiently informed and guided about your child’s current and future status as a SEN student?” and “Are the school professionals approachable and open to communication?” Other studies were also considered, such as Sánchez (2020), whose questionnaire included 69 indicators in seven dimensions, covering aspects such as the family–school relationship and the overall assessment of the care received, with questions such as “Do you receive guidance or educational guidelines from the school to continue the work at home?” and “Do you think there is a lack of training for the teachers who work with your child?” The interviews were conducted individually, either in person or via video call, depending on the families’ availability, with an approximate duration of 30 to 45 min.

The content of the interview was validated by four university experts specializing in educational inclusion. They assessed the relevance and appropriateness of each question on a scale ranging from 0 to 10, with 0 being the lowest possible score in each case. To ensure the quality of the research performed, a threshold of a 7-point average was established to consider the questions relevant or appropriate for this study. The average score obtained was 8.6 for relevance and 8.4 for appropriateness, thus exceeding the established threshold in both cases. The overall content validity index, calculated as the average of both dimensions, was 8.5, confirming the high validity of the instrument.

The final instrument consisted of an interview with nine questions, organized into four categories to facilitate the analysis of the different dimensions of the family experience in educational inclusion, as shown in Table 1:

Table 1.

Categories and questions in the interview.

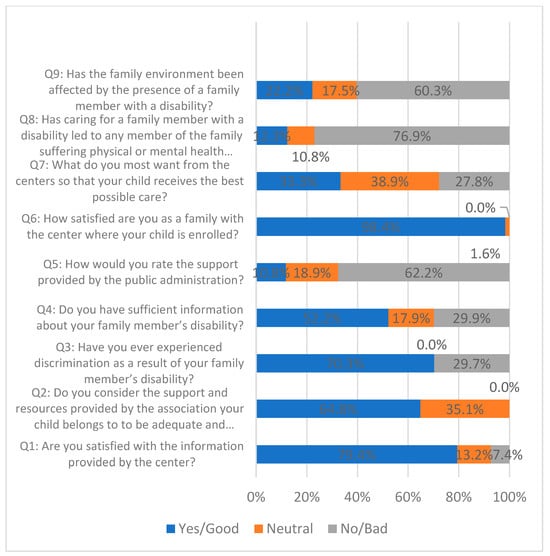

This study employed semi-structured interviews, combining straightforward questions and open-ended ones. Some questions expected a simple “yes/no/neutral” response (e.g., Q1. Are you satisfied with the information you have received from the center?; Q3. Have you ever experienced discrimination as a result of your family member’s disability?), while others elicited responses along ordinal scales such as “good/regular/poor” or “much/little/regular” (e.g., Q5. How good is the support provided by the public administration?). Regardless of format, responses were analyzed quantitatively by coding them as positive, neutral, or negative, as shown in Figure 1. While most participants provided direct responses, when no explicit answer was given, the quantitative category was inferred from accompanying comments or elaborations. Additionally, many questions generated qualitative data, as participants often offered justifications or further explanations, which were subsequently analyzed through thematic coding.

Figure 1.

Percentages of the perceptions of family members of students with functional diversity in relation to the quality of the response they receive in schools.

4.3. Procedure for Analyzing and Categorizing Family Interviews

The interviews with family members were transcribed, and a thematic analysis of the messages was carried out, segmenting them according to specific topics, following the method proposed by Montanero (2014). Closed-ended questions provided quantitative data with responses such as “yes,” “no,” or “neutral.” However, the positive, negative, or neutral nature of some answers was not always directly indicated, so it had to be inferred from the participants’ comments. Additional qualitative data were derived from participants’ justifications, elaborations, and open-ended responses. Each unit of analysis was classified according to the categories defined in Table 2, which were designed using an inductive–deductive process. In the first phase, various previous studies on perceptions of inclusive education (Rosado-Castellano et al., 2022) were reviewed to establish initial categories for the analysis of family comments. Subsequently, when examining the segments extracted from the sample, comments were identified that did not clearly fit into the pre-existing categories, which led to the incorporation of new categories to more accurately reflect the diversity of responses. After a training process for coding, two researchers achieved a level of agreement of over 80% when evaluating a random sample of 44 comments. The Cohen’s Kappa index obtained was 0.81 (p < 0.01), indicating high reliability in the categorization process.

Table 2.

System of categories of comments from family members of students with functional diversity in relation to the quality of schools.

4.4. Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using a mixed-methods approach, integrating quantitative and qualitative procedures. For each category, the number of positive, neutral, and negative responses provided by family members for each question was counted, and the corresponding percentages were calculated. Chi-square tests of independence were performed to explore differences between thematic categories and specific questions, with Cramer’s Phi and V measures quantifying the strength of associations. Qualitative data, consisting of participants’ justifications and open comments, were coded thematically and used to illustrate the quantitative trends and categories identified in the cross-category analysis,

4.5. Limitations

The main limitations of the study include the use of convenience sampling, which restricts the ability to generalize the findings to other populations. Additionally, as a qualitative study based on interviews, the results are influenced by the sociocultural context of the participants as well as their willingness to share personal experiences. Also, the interpretation of the data may be affected by the subjectivity of both the interviewees and the research team, despite the use of systematic analysis procedures to ensure rigorousness. Finally, another limitation entails the absence of precise data regarding the number of students with functional diversity who receive specific support, which could have allowed for a more comprehensive analysis in this case.

5. Results

This section presents the results of interviews with family members of people with functional diversity. The results are organized into two complementary sections. First, the quantitative results are reported, derived from the frequencies and percentages of dichotomous and scaled responses. These data are then supplemented by qualitative evidence, consisting of open comments and testimonies from families, which illustrate the meaning and nuances behind the responses. Finally, an inferential analysis exploring the statistical associations between the different dimensions and questions is presented. This analysis provides a deeper understanding of significant differences in these families’ perceptions of educational centers and their environments.

5.1. Descriptive Analysis of Family Responses and Testimonies Regarding the Quality of Educational Inclusion for People with Functional Diversity

In the 70 interviews conducted, 437 units of analysis were identified, from which the perceptions of the families of people with functional diversity who attend educational centers in Extremadura were explored. The results of the categorization are shown in Figure 1, which shows the quantitative response percentages according to the degree of agreement on each of the items in the interview. Alongside these, selected qualitative testimonies are presented to exemplify and enrich the numerical trends.

With regard to the first category, which is concerned with the information received by families, the results show a predominantly positive assessment. Quantitatively, a total of 79.4% of families say they are satisfied with the information provided by the school (Q1). Qualitatively, this perception is reinforced by the implementation of communication tools such as WhatsApp, mentioned by participant number 57: “New technologies (WhatsApp) make it easier.” However, 13.2% of families indicate that the information is insufficient or not very up to date. Family member number 4, for example, states: “There is a lack of up-to-date/more frequent information.” In addition, 7.4% express dissatisfaction with the communication received from the center. Regarding knowledge about the family member’s disability (Q4), quantitative data indicate that 52.2% of the informants report being provided with sufficient information, as expressed by family member 13: “I know about my sister’s illness, I have always been interested in all the doctors since she is my responsibility.” However, 29.9% indicate a lack of knowledge, and 17.9% take an intermediate position, as reflected in the comment: “I don’t think so, because you can never know everything about something, especially my son’s illness.”

In relation to the second category, which entails the resources made available to families and institutions (Q2, Q5, Q7), informants have a heterogeneous perception depending on the source of the support which provides these resources in each case. A total of 64.8% positively value the support and resources offered by the nonprofit association their child belongs to (Q2), compared to 35.1% who express a neutral position. Qualitative comments highlight both strengths and shortcomings such as “improvable computers” or “lack of funding to obtain resources.” By contrast, the support provided by the public administration (Q5) receives a clearly negative assessment: 62.2% consider it insufficient, compared to only 10.8% who value it positively. Family member number 10 comments: “The financial resources provided to us are scarce,” while number 20 points out: “They should take us more into account, we are one of the most forgotten groups.” In contrast, another family member indicates: “Luckily, the economy is doing well, as he has several paychecks and invests that money in himself.” Almost one in five family members (18.9%) express a more ambiguous opinion, with comments such as: “Well, my son’s paycheck isn’t bad, but don’t think it covers all his expenses.” As for the demands that families make of the centers (Q7), quantitative analysis shows that 38.9% call for more support staff, greater individualized attention, and smaller class sizes. Another 33.3% specifically request more employment opportunities for their children, while 27.8% mention other needs such as increased leisure options or material improvements.

With regard to the third category, which measures overall satisfaction, the assessment of the educational center (Q6) is overwhelmingly positive: quantitative results show that 98.4% of families are satisfied, and only 1.6% express a neutral opinion. No negative responses were recorded. This high level of satisfaction coincides with positive comments about staff involvement and fluid communication with families.

Finally, in relation to the fourth category, emotions and psychological well-being (Q3, Q8, Q9), the interviews explore the emotional and psychological impact on families. A total of 70.3% of families say they have experienced situations of discrimination related to disability (Q3). Qualitative testimonies illustrate this finding; for example, family member number 16 reports: “Yes, on many occasions. At school, on the street, in a restaurant... in many places.” Regarding the impact on the physical or mental health of a family member (Q8), 76.9% deny such a relationship. However, 12.3% of participants establish a direct connection, as illustrated by this testimony: “We have always had a lot of anxiety problems because we suffer a lot and have to be on the lookout for it 24 h a day.” In addition, 10.8% of the responses show an ambiguous perception, in which discomfort is acknowledged but not directly associated with the family member’s disability, with comments such as: “I have suffered from mental health problems and I still do, but it’s not entirely because of my brother, it’s because of me.” Regarding the family environment (Q9), quantitative analysis shows that 60.3% consider it has not been affected (for example: “The health problems we have are because we are older”), compared to 22.2% who say the opposite. Qualitative narratives provide additional context; for example, family member number 1 explains: “At first, it’s true that I was the first one who had the hardest time accepting it, and that was traumatic for me [...] his older brother also had a hard time.”.

5.2. Inferential Analysis of the Associations Between Family Responses and Dimensions of Educational Inclusion for People with Functional Diversity

The results of the chi-square tests show statistically significant differences both among the thematic dimensions analyzed and among the individual questions in the questionnaire. These analyses were applied only to the quantitative data. Firstly, significant differences were observed in the distribution of responses (positive, neutral, and negative) depending on the thematic category (χ2(4) = 96.08; p < 0.001), with a moderate association between variables, reflected in a Phi coefficient of 0.491 and a Cramer’s V of 0.35, both significant (p < 0.001). It is observed that some dimensions, such as information and resources, concentrate positive responses, while in the well-being category negative responses were highly predominant, suggesting a positive perception at the institutional level but a more critical view regarding emotional and family aspects.

Complementarily, the analysis by specific question also showed significant differences in the evaluations (χ2(10) = 158.83; p < 0.001), with a strong association evidenced by a Phi of 0.63 and a Cramer’s V of 0.45, both highly significant (p < 0.001). A high proportion of positive responses stand out in items such as satisfaction with the information received (Q1) and the resources offered by associations (Q2), with large standardized residuals indicating a higher frequency than expected, though seemingly by chance. In contrast, questions related to health impact (Q8) and family environment (Q9) showed a greater concentration of negative responses, reflecting sensitive areas that affect the families’ well-being.

6. Discussion

This study addresses a significant research gap regarding the analysis of the quality of the educational support provided to students with functional diversity from the perspective of their families. Through semi-structured interviews, it has explored how these families perceive and evaluate the educational response their children receive in schools.

Regarding the first research question, which aimed at understanding how families value the accompaniment, communication, and supports received, the results reveal a predominantly positive assessment. A total of 79.4% of families declare satisfaction with the information provided by the schools (Q1), supporting the claims of Paseka and Schwab (2020), who highlight the importance of the school–family link in inclusion processes. This finding contrasts with results from studies such as Castillo Armijo (2021) and Roa-González et al. (2022), where negative perceptions towards the relationship between families and institutions were highly predominant. Furthermore, the overall assessment of the school (Q6) is overwhelmingly positive (98.4%). It should be noted that this high level of satisfaction refers to the institution as a whole, and not solely to the teaching staff. It also seems to be associated with other factors of the school, such as the school’s atmosphere, the specific care received by students, or the accessibility of resources. These factors reinforce the idea, upheld by Ainscow (2012), that inclusive practices depend not only on material resources but also on human relationships and professional attitudes. This finding reinforces the need to promote continuous training and the active involvement of teachers in inclusive processes, as highlighted by Pla-Viana and Villaescusa (2021).

However, when analyzing the perception of the available resources (Q2, Q5), important nuances emerge. While 64.8% positively value the support offered by associations, 62.2% express a negative opinion about the resources provided by public administration. Families often link the lack of specialized personnel or adapted materials to structural deficiencies in public administration, rather than to the local institutions themselves. This finding aligns with studies by Gómez and Moya (2017), Fernández et al. (2021), and Pérez-Vera et al. (2024), which emphasize the persistence of barriers related to the scarcity of human and material resources in school settings. The demand for more specialized staff and individualized attention (Q7), expressed by 38.9% of participants, aligns with the statements made by Abellán-Rubio et al. (2021) and Ainscow (2012), which reinforces the urgency to review the student–teacher ratio to advance towards more effective educational inclusion.

Regarding the second research question hereby posed—concerned with the main obstacles and deficiencies hindering effective educational inclusion—the testimonies identify both structural and attitudinal barriers. Among the most notable of these barriers are the insufficiency of public resources (Q5), the scarcity of specialized supports, and the high student–teacher ratio. Nevertheless, families do not hold the schools directly responsible for the lack of resources but rather attribute this shortage to insufficient support from public administration. These demands reveal the persistence of an educational model based on integration logic rather than transformative inclusion (Ainscow, 2020). Likewise, families report limitations in their participation in educational decision-making, pointing to a lack of institutional shared responsibility. This aspect coincides with the claims made by Travert and Sanahuja (2022), who call for policies that recognize families as active agents in educational processes, beyond merely being recipients of information.

Concerning the third question—related to the emotional impact and psychological well-being of families regarding educational inclusion and experiences of discrimination—the data suggest a complex reality. Although 76.9% of families do not establish a direct relationship between their psychological well-being and the family member’s disability (Q8), 70.3% affirm having experienced discrimination in school and social contexts (Q3). This result corroborates the views of Sakamoto (2021), who denounces the persistence of social and attitudinal barriers which are not always institutionally recognized. These experiences also affect the family atmosphere (Q9): 22.2% report having suffered alterations in family dynamics, especially during the early stages of diagnosis or schooling. This emotional dimension reaffirms the need for an integral approach to inclusion, as proposed by Moriña (2020) and Jerrim and Sims (2022), which articulates educational and psychosocial aspects.

Finally, regarding the fourth question—how families value information and support in areas that are complementary to the school, such as employment, leisure, and the family environment—the results show clear dissatisfaction in these matters. Although communication with schools is generally highly valued, limitations persist in the transition to adulthood. A total of 33.3% of the families interviewed express their concerns about employment and leisure (Q7), pointing to deficiencies in available supports and discriminatory attitudes outside the educational environment. These findings align with those of Fernández et al. (2021) and Pérez-Vera et al. (2024), and correspond with the Sustainable Development Goals and UNESCO’s (2015) action framework, which propose a vision of inclusion that transcends the school space.

In this regard, authors such as Ossai (2022) and Ainscow (2020) stress the urgency of articulating public policies that promote dignified living conditions in all areas, not just education. As the analyzed testimonies show, inclusion is only real when access to transversal, sustained, and coordinated supports over time is guaranteed. In this context, it would be necessary to strengthen and evaluate the already existing programs in Extremadura, such as the Diversity Care Plan or the educational support measures of Decree 228/2014.

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study, based on a qualitative approach through semi-structured interviews with families of students with functional diversity in Extremadura, Spain, offers a valuable—although not generalizable—insight into how these families perceive educational inclusion. The exploratory nature of the research, combined with the non-probabilistic sample selection and the possible influence of social desirability bias, requires cautious interpretation of the results. Nevertheless, the obtained data allow the identification of significant patterns that deserve consideration by both educational authorities and the research community.

Firstly, families value the communicative relationship with educational centers positively, suggesting that institutional support—when close and receptive—can be a protective factor in contexts of diversity. However, this positive perception contrasts with the negative assessments regarding resources provided by the administration, highlighting a fracture between the local commitment of teaching staff and the structural conditions imposed by the system.

The results also reveal that barriers to inclusion are not limited to material issues but rather closely linked to social attitudes, institutional practices, and inflexible organizational structures. Experiences of discrimination and the emotional overload expressed by many families reflect partial inclusion, where the physical presence of students does not always translate into full participation or equal opportunities. Moreover, family and emotional well-being appear conditioned by factors outside the school environment, such as the lack of support at home, difficulties accessing leisure and employment services, or feelings of social isolation. These elements reinforce the need to move towards a comprehensive form of inclusion that goes beyond the strictly educational sphere and contemplates coordinated actions at the community and family levels.

Overall, the findings suggest that improving inclusion does not depend solely on increasing resources but also on fostering a school culture that is participatory, collaborative, and sensitive to diversity. In this task, the involvement of families—as observed in cases with higher satisfaction and progress—is essential to building fairer and more sustainable educational responses. Future studies could potentially deepen the analysis of these factors by using comparative or longitudinal approaches, also incorporating the voices of students with functional diversity and teaching staff. It would also be relevant to explore the impact of specific family–school collaboration programs on improving family well-being and reducing experiences of discrimination. Moreover, the influence of social desirability bias should be considered, particularly in responses related to institutional satisfaction or emotional well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.-H. and M.-J.F.-S.; methodology, L.d.C.M.; validation, S.S.-H.; formal analysis, L.d.C.M. and L.P.-V.; investigation, L.d.C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, L.P.-V. and L.d.C.M.; writing—review and editing, all authors; supervision, S.S.-H. and M.-J.F.-S.; project administration, S.S.-H.; funding acquisition, S.S.-H. and M.-J.F.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Regional Development Fund (A Way to Make Europe), the Government of Extremadura (Junta de Extremadura, groups SEJ020 and SEJ008), the MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, and the ERDF/EU (grant PID2023-147501OB-I00).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Extremadura (protocol code 177_2025, approved on 12 May 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article due to confidentiality restrictions and the lack of informed consent for third-party data sharing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Q1–Q9 | Interview items |

| ODS | Sustainable Development Goals |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| LOMLOE | Organic Law 3/2020, of December 29, amending Organic Law 2/2006, of 3 May, on Education |

References

- Abellán-Rubio, J., Arnaiz-Sánchez, P., & Alcaraz-García, S. (2021). El profesorado de apoyo y las barreras que interfieren en la creación de apoyos educativos inclusivos. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 24(3), 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M. (2012). Haciendo que las escuelas sean más inclusivas: Lecciones a partir del análisis de la investigación internacional. Revista de Educación Inclusiva, 5(1), 39–49. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4105297 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Ainscow, M. (2020). Promoting inclusion and equity in education: Lessons from international experiences. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 6(1), 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, A. M. (2014). La inclusión educativa desde la voz de los padres. Revistanacional e Internacional de Educación Inclusiva, 7(1), 110–120. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, T., & Ainscow, M. (2015). Guía para la educación inclusiva. Desarrollando el aprendizaje y la participación en los centros escolares. OEI, FUHEM. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo Armijo, P. (2021). Inclusión educativa en la formación docente en Chile: Tensiones y perspectivas de cambio. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación, 20(43), 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collet-Sabé, J. (2020). Les relacions entre l’escola i les famílies des d’una perspectiva democràtica: Eixos d’anàlisi i propostes per a l’equitat. Educar, 45(1), 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, C. (2017). Respuesta educativa en la atención a la diversidad desde la perspectiva de profesionales de apoyo. Revista Colombiana de Educación, (73), 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisol-Moya, E., Romero-López, M. A., Burgos García, A., & Sánchez-Hernández, Y. (2022). Inclusive leadership from the family perspective in compulsory education. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research, 11(2), 226–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, M., Villagra, A., & Castejón, F. J. (2019). Coordination between physical education teachers and physical therapists in physical education classes: The case of the autonomous community of Madrid in Spain. Movimiento, 25, 1–16. Available online: https://cutt.ly/9wrJFluO (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Domingo, J., Martos, M. A., & Domingo, L. (2010). Colaboración familia-escuela en España: Retos y realidades. REXE. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación, 9(18), 111–133. Available online: https://www.rexe.cl/index.php/rexe/article/view/133 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Escobedo-Peiro, P., Traver-Martí, J. A., & Sales, A. (2021). ¿De quién es la escuela? La voz del alumnado y de las familias en la construcción de una escuela inclusiva. Revista de Educación Inclusiva, 14(2), 166–181. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Batanero, J. M., & Benítez Jaén, A. M. (2016). Respuesta educativa de los centros escolares ante alumnado con síndrome de Down: Percepciones familiares y docentes. Profesorado, Revista De Currículum Y Formación Del Profesorado, 20(2), 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M. J., Pérez, L., & Sánchez, S. (2021). Escuela pública y COVID-19: Dificultades sociofamiliares de educación en confinamiento. Publicaciones, 51(3), 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gento, S. (2007). Requisitos para una inclusión de calidad en el tratamiento educativo de la diversidad. Bordón, 59(4), 581–595. [Google Scholar]

- Gokalp, S., Akbasli, S., & Dis, O. (2021). Communication barriers in the context of school-parents cooperation. European Journal of Educational Management, 4(2), 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, I., & Moya, A. (2017). Percepciones de las familias del alumnado con necesidades educativas especiales sobre la inclusión escolar en la educación primaria. In A. Rodríguez (Ed.), Prácticas Innovadoras inclusivas: Retos y oportunidades (pp. 97–105). Universidad de Oviedo. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Gil, F., Martín-Pastor, E., & Poy Castro, R. (2019). Educación inclusiva: Barreras y facilitadores para su desarrollo. Un estudio desde la percepción del profesorado. Profesorado, Revista De Currículum Y Formación Del Profesorado, 23(1), 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerrim, J., & Sims, S. (2022). Responsabilidad escolar y estrés docente: Evidencia internacional del estudio TALIS de la OCDE. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 34, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LOMLOE. (2020). Ley Orgánica 3/2020, de 29 de diciembre, por la que se modifica la Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de mayo, de Educación, núm. 340 de 30 de diciembre de 2020. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2020/BOE-A-2020-17264-consolidado.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- López, G., & Carmona, C. (2018). La inclusión socio-educativa de niños y jóvenes con diversidad funcional: Perspectiva de las familias. Revista de Educación Inclusiva, 11(2), 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Maqueira, G. C., Caraballo, S., Guerra Iglesias, R. I., & Velasteguí, E. (2023). La educación inclusiva: Desafíos y oportunidades para las instituciones escolares. Journal of Science and Research, 8(3), 210–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanero, M. (2014). El análisis del discurso educativo en el aula. Una revisión de las principales alternativas metodológicas. Investigación Cualitativa en Educación, 1, 122–127. [Google Scholar]

- Moriña, A. (2020). Approaches to Inclusive Pedagogy: A Systematic Literature Review. Pedagogika/Pedagogy, 140(4), 134–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntaner-Guasp, J. J., Mut-Amengual, B., & Pinya-Medina, C. (2022). Las metodologías activas para la implementación de la educación inclusiva. Revista Electrónica Educare, 26(2), 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossai, A. G. (2022). Sustainable Development Goal Four (SDG4): Challenges and the Way Forward. Academia Letters, 8(2), 4839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo-Baldoví, M. I., Marín-Suelves, D., & Vidal-Esteve, M. I. (2022). Prácticas docentes en la escuela digital: La inclusión como reto. Revista Latinoamericana de Tecnología Educativa—RELATEC, 21(1), 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paseka, A., & Schwab, S. (2020). Parents’ attitudes towards inclusive education and their perceptions of inclusive teaching practices and resources. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 35(2), 254–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Vera, L., Sánchez, S., Rabazo, M. J., & Fernández, M. J. (2024). Inclusión educativa de los estudiantes con discapacidad: Un análisis de la percepción del profesorado. Retos: Nuevas Tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, (51), 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pla-Viana, L., & Villaescusa, I. (2021). Preocupações do professor sobre a inclusão de alunos com deficiência nas salas de aula de educação regular. Psicologia em Pesquisa, 15(2), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa-González, R., Quiroga-González, N., & Araya-Cortés, A. (2022). Educación inclusiva de la primera infancia en tiempos de pandemia COVID-19: Percepciones de las familias. Revista Latinoamericana de Educación Inclusiva, 16(1), 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Gudiño, M., Jenaro Río, C., & Castaño Calle, R. (2023). Un estudio comparativo del compromiso de familias y profesorado con la inclusión educativa. Revista Española de Discapacidad, 11(1), 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas Fabris, M. T., Salas, N., & Rodríguez, J. I. (2021). Directoras y directores escolares frente a la Ley de Inclusión Escolar en Chile: Entre compromiso, conformismo y resistencia. Pensamiento Educativo, 58(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosado-Castellano, F., Sánchez Herrera, S., Pérez-Vera, L., & Fernández-Sánchez, M. J. (2022). Inclusive education as a tool of promoting quality in education: Teachers’ perception of the educational inclusion of students with disabilies. Education Sciences, 12, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, U. (2019). Parents’ participation types in school education. International Journal of Educational Methodology, 5(3), 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, J. (2021). The association between parent participation in school management and student achievement in eight countries and economies. International Education Studies, 14(1), 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanahuja, A., Borri-Anadon, C., & De Angelis, C. (2022). Prácticas inclusivas en el contexto escolar: Una mirada sobre tres experiencias internacionales. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, 89(1), 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, M., & Waitoller, F. (2022). Ampliando el concepto de participación en la educación inclusiva: Un enfoque de justicia social. Revista Española de Discapacidad, 10(2), 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M. L. (2020). Percepción de las familias de alumnos con necesidades específicas de apoyo educativo sobre el sistema escolar. Diseño y validación de un cuestionario [Doctoral Thesis, Universidad Católica de Valencia]. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Pujalte, L., Gómez-Domínguez, M. T., Soto-Rubio, A., & Navarro-Mateu, D. (2020). Does the school really support my child? SOFIA: An assessment tool for families of children with SEN in Spain. Sustainability, 12(19), 7879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenker, R., Rigbi, A., Parush, S., & Yochman, A. (2017). A survey on parent-conductor relationship: Unveiling the black box. International Journal of Special Education, 32(2), 387–412. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1184113.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Sepúlveda Opazo, F., & Castillo Armijo, P. (2021). Percepciones sobre la inclusión educativa en una comunidad escolar de la ciudad de Pelarco, Chile. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación, 20(44), 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, U., & Jacobs, D. T. K. (2016). Predicting in-service educators’ intentions to teach in inclusive classrooms in India and Australia. Teaching and TeacherEducation, 55, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travert, S., & Sanahuja, A. (2022). Acompañamiento y orientación educativa: Hacia procesos de asesoramiento orientados a generar prácticas más inclusivas. Revista Nacional e Internacional de Educación Inclusiva, 15(2), diciembre 2022, e-ISSN 1989-4643. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. (1994). Declaración de salamanca y marco de acción sobre necesidades educativas especiales. UNESCO y Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. (2021). Reimagining our futures together: A new social contract for education. UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, A. D., Morrison, F. J., & Palincsar, A. S. (2018). Perceptions of communication practices among stakeholders in special education. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 26(4), 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).