Exploring Greek Primary Teachers’ Perspectives in Inclusive Education for Special Educational Needs (SEN) Students and Related Research Trends: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Method

2.2. Search Strategy

- ““Greek” OR “Greece” AND “teachers” AND “Inclusive Education” AND “disabilities” OR SEN””,

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- ✓

- The articles refer to only in-service primary teachers;

- ✓

- The articles refer to Inclusive Education for SEN students;

- ✓

- The articles refer to the Greek context.

- ✓

- Articles were excluded if they were purely theoretical, policy-focused, or opinion-based, without presenting original empirical data on Greek primary teachers’ perspectives (attitudes, knowledge, challenges, and needs) on Inclusive Education for SEN students.

2.4. Screening Process

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

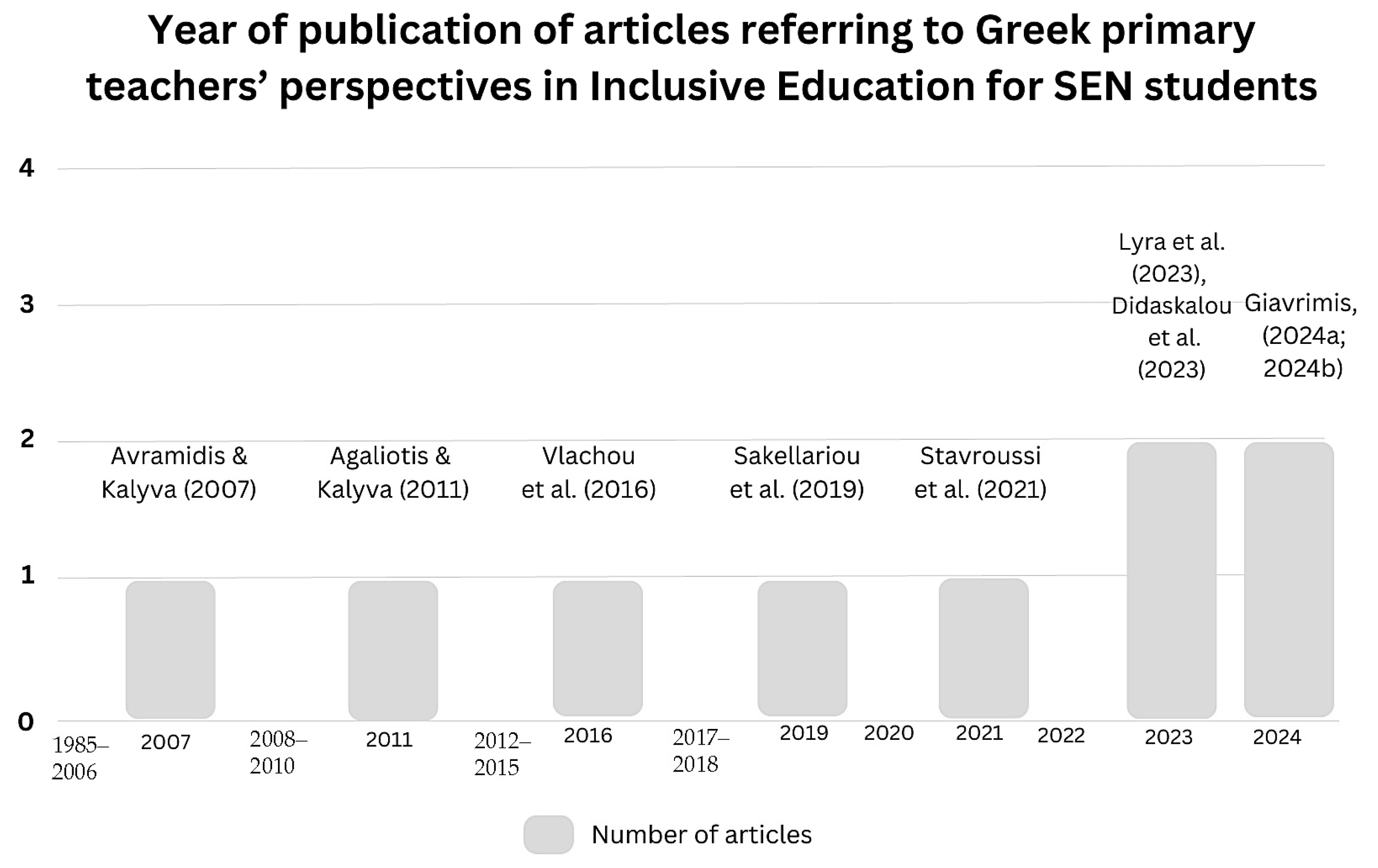

3.1. RQ1—What Are the Publication Trends and Methodological Characteristics of Journal Articles Examining Greek Primary Teachers’ Perspectives on Inclusive Education for SEN Students?

3.2. RQ2—What Attitudes and Perceptions Do Greek Primary School Teachers Hold Towards Inclusive Education for SEN Students, as Reported in the Literature?

3.3. RQ3—What Is the Level, Focus, and Adequacy of Greek Primary School Teachers’ Knowledge in the Fields of Inclusive Education for SEN Students?

3.4. RQ4—What Specific Challenges and Support Needs Are Identified for Greek Primary Teachers Implementing Inclusive Educational Approaches in Mainstream Classroom with SEN Students?

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Further Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agaliotis, I., & Kalyva, E. (2011). A survey of Greek general and special education teachers’ perceptions regarding the role of the special needs coordinator: Implications for educational policy on inclusion and teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(3), 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M. (2020). Promoting inclusion and equity in education: Lessons from international experiences. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 6(1), 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M. F., Alam, M., Kumar, A., & Ali, N. (2024). Investigation of primary school teachers’ attitude towards inclusive education in Western Division in Fiji. Cogent Education, 11(1), 2419704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloka, P. J. O., & Mamogobo, A. (2024). Teacher related challenges experienced in the implementation of inclusive education in one selected mainstream school in South Africa. International Journal of Social Sciences & Educational Studies, 12(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsolami, A., & Vaughan, M. (2023). Teacher attitudes toward inclusion of students with disabilities in Jeddah elementary schools. PLoS ONE, 18(1), e0279068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asila, K. (2025). The importance of education for primary school students and its impact on success in later academic activities. International Multidisciplinary Journal for Research & Development, 12(01), 805. [Google Scholar]

- Avramidis, E., & Kalyva, E. (2007). The influence of teaching experience and professional development on Greek teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 22(4), 367–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batsiou, S., Bebetsos, E., Panteli, P., & Antoniou, P. (2008). Attitudes and intention of Greek and Cypriot primary education teachers towards teaching pupils with special educational needs in mainstream schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 12(2), 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charitaki, G., Kourti, I., Gregory, J. L., Ozturk, M., Ismail, Z., Alevriadou, A., Soulis, S. G., Sakici, Ş., & Demirel, C. (2022). Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education: A cross-national exploration. Trends in Psychology, 32, 1120–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayso, A. L., Dulionan, M. O., Labot, V. S., Lassin, R. D., Mangsi, L. W., & Nucaza, J. M. (2025). Challenges and practices of education teachers on inclusive education. Cognizance Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, 5(1), 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didaskalou, E., Stavroussi, P., & Green, J. G. (2023). Does primary school teachers’ perceived efficacy in classroom management/discipline predict their perceptions of inclusive education? Pastoral Care in Education, 42, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dr. Ranbir. (2024). Inclusive education practices for students with diverse needs. Innovative Research Thoughts, 10(1), 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmer, E. T., & Hickman, J. (1991). Teacher efficacy in classroom management and discipline. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 51(3), 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forlin, C., Kong, H., Earle, C., & Loreman, T. (2011). The sentiments, attitudes, and concerns about inclusive education revised (SACIE-R) scale for measuring pre-service teachers’ perceptions about inclusion. Exceptionality Education International, 21(3), 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W. Q., Xie, Y., Li, R., & He, X. (2021). General teachers’ attitude toward inclusive education in Yunnan Province in China. International Journal of Psychology and Psychoanalysis, 7(1), 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galaterou, J., & Antoniou, A.-S. (2017). Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education: The role of job stressors and demographic parameters. International Journal of Special Education, 32(4), 643–658. [Google Scholar]

- Giavrimis, P. (2024a). Inclusion classes in Greek education: Political and social articulations. An interpretive phenomenological analysis. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 24(3), 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giavrimis, P. (2024b). Parallel support as an institution for tackling social and educational inequalities: Functioning and barriers in the Greek education system. Support for Learning, 39(3), 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jugan, M. B., Rozanne Delos Reyes, N. T., Pepito, J. C., Capuno, R. G., Pinili, L. C., Frances Cabigon, A. P., Sitoy, R. E., Mamites, I. O., & Author-Michelle Jugan, C. B. (2024). Attitudes of elementary teachers towards inclusive education of learners with special education needs in a public school. Power System Technology, 48(1), 2173–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryshtanovych, S., Sych, Y., Mashtakova, N., & Mordovtseva, N. (2022). Features of the development of primary education in the context of the impact of COVID-19. Revista Tempos e Espaços Em Educação, 15(34), e17157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, K. T., Schwab, S., Emara, M., & Avramidis, E. (2023). Do teachers favor the inclusion of all students? A systematic review of primary schoolteachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 38(6), 766–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyra, O., Koullapi, K., & Kalogeropoulou, E. (2023). Fears towards disability and their impact on teaching practices in inclusive classrooms: An empirical study with teachers in Greece. Heliyon, 9(5), e16332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantry, A., & Pradhan, B. (2023). Attitude of elementary school teachers towards inclusive education: A study on Jammu and Kashmir, India. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 19(2), 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S. (2024). Attitude of elementary school teachers towards Inclusive classroom at elementary stage. Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education (TURCOMAT), 15(2), 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, N., Lyons, C., & Frizelle, P. (2025). Staff perceptions and experiences of using key word signing with children with down syndrome and their peers in the first year of mainstream primary education. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 60(1), e13149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A. A. (2024). Knowledge level of teachers on inclusive education in tamale metropolis in the Northern Region of Ghana. Open Journal of Educational Research, 4(3), 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyzopoulou, K., & Tsakiridou, H. (2023). Attitudes of Greek general education teachers concerning Inclusion policy. European Journal of Education Studies, 10(6), 312–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pov, S., Kawai, N., & Matsumiya, N. (2024). Identifying Cambodian teachers’ concerns about including students with disabilities in regular classrooms: Evidence from a nationwide survey. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 24(4), 1148–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radojlovic, J., Kilibarda, T., Radevic, S., Maricic, M., Parezanovic Ilic, K., Djordjic, M., Colovic, S., Radmanovic, B., Sekulic, M., Djordjevic, O., Niciforovic, J., Simic Vukomanovic, I., Janicijevic, K., & Radovanovic, S. (2022). Attitudes of primary school teachers toward inclusive education. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 891930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmatullayeva, P. Z. (2025). Psychological and pedagogical barriers to the transition to inclusive education in primary grades. Journal of Applied Science and Social Science, 15(06), 324–329. [Google Scholar]

- Sakellariou, M., Strati, P., & Emmanouil, K. (2018). Exploring the attitude of Greek kindergarten and primary school teachers towards inclusive education. Journal of Advanced Research in Social Sciences, 1, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakellariou, M., Strati, P., & Mitsi, P. (2019). Aspects of Greek teachers concerning teaching within co-educational classes: An exploratory approach to elementary school. Open Journal for Educational Research, 3(2), 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis-Onofre, R., Catalá-López, F., Aromataris, E., & Lockwood, C. (2021). How to properly use the PRISMA statement. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarris, D., Riga, P., & Zaragas, H. (2018). School teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education in Greece. European Journal of Special Education Research, 3(3), 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savaş, H., & İsaoğlu, Y. (2025). Teachers attitudes towards inclusive education: A mixed method study. Ahmet Keleşoğlu Faculty of Education Journal, 7(1), 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shechtman, Z. (2002). Validation of the democratic teacher belief scale (dtbs). International Journal of Phytoremediation, 21(1), 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddik, A. B. (2025). Challenges and resources for inclusive education in Bangladesh: Insights from primary school Teachers. Journal of International Development Studies, 33(3), 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavroussi, P., Didaskalou, E., & Greif Green, J. (2021). Are teachers’ democratic beliefs about classroom life associated with their perceptions of inclusive education? International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 68(5), 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoiber, K. C., Gettinger, M., & Goetz, D. (1998). Exploring factors influencing parents’ and early childhood practitioners” beliefs about inclusion. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 13(1), 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tah, J., Raptopoulou, A., Tajic, D., & Gani Dutt, K. (2024). Inclusive education policy in differentiated contexts: A comparison between Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cameroon, Greece, India and Sweden. European Journal of Inclusive Education, 3(1), 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakiridou, H., & Polyzopoulou, K. (2014). Greek teachers’ attitudes toward the inclusion of students with special educational needs. American Journal of Educational Research, 2(4), 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uka, E. (2024). Exploring differences in primary school teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education in Kosovo. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 40(1), 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (1994). The Salamanca statement and framework for action on special needs education. UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Vlachou, A., Stavroussi, P., & Didaskalou, E. (2016). Special teachers’ educational responses in supporting students with special educational needs (SEN) in the domain of social skills development. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 63(1), 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcock, S., & Anderson, J. (2025). Conceptions to classrooms: The influence of teacher knowledge on inclusive classroom practice. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 8, 100412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X. (2024). The impact of regular elementary school teachers’ attitudes on inclusive education for special needs children and improvement suggestions. Communications in Humanities Research, 37(1), 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database/Website | Type of Search | Inclusive Education Results | Inclusive Education Results After Refinement (Article/Language) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scopus | Article, title, abstract, keywords | 30 | 25 |

| Science Direct | Title, abstract, keywords | 3 | 3 |

| ERIC | Abstract | 15 | 14 |

| MDPI | All journals | 5 | 5 |

| Total | 53 | 47 * |

| Database/Website | Inclusive Education Duplicates | Inclusive Education (Remained Articles) |

|---|---|---|

| Scopus | 0 | 25 |

| Science Direct | 2 | 1 |

| Eric | 7 | 7 |

| MDPI | 1 | 4 |

| Total | 10 | 37 |

| Database/Website | Inclusive Education Results | Inclusive Education Results After 1st Criterion |

|---|---|---|

| Scopus | 25 | 8 |

| Science Direct | 1 | 0 |

| Eric | 7 | 1 |

| MDPI | 4 | 1 |

| Total | 37 | 10 |

| Database/Website | Inclusive Education Results | Inclusive Education Results After 2nd Criterion |

|---|---|---|

| Scopus | 8 | 8 |

| Science Direct | 0 | 0 |

| Eric | 1 | 1 |

| MDPI | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 10 | 9 |

| Title | Year | Authors | Journal | Sample Size | Sample’s Affiliation | Study’s Scope | Research Method/Tool(s) | Database |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusion classes in Greek education: political and social articulations. An Interpretive phenomenological analysis. | 2024 | Giavrimis (2024a) | Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs | 9 | General Education teachers | The study explores the institution of inclusion classes as a supportive educational framework for students with special educational needs and/or disabilities (SEND) for their inclusion in the mainstream education system through teachers’ conceptualizations. | Qualitative method (semi-structured interview) | Scopus |

| Parallel support as an institution for tackling social and educational inequalities: Functioning and barriers in the Greek education system | 2024 | Giavrimis (2024b) | Support for learning | 12 | General Education teachers | The study investigates teachers’ views as critical factors in the success of inclusive education on the Parallel Support (PS) institution in Greece and the educational policies implemented. | Qualitative method (semi-structured interview) | Scopus |

| Fears towards disability and their impact on teaching practices in Inclusive classrooms: An empirical study with teachers in Greece. | 2023 | Lyra et al. (2023) | Heliyon | 15 | General and Special Education teachers | The study examines Greek special and general education teachers’ fears toward disability and their impact on teaching in inclusive classrooms. | Qualitative method (semi-structured interview) | Scopus |

| Does primary school teachers’ perceived efficacy in classroom management/discipline predict their perceptions of Inclusive Education? | 2023 | Didaskalou et al. (2023) | Pastoral Care in Education | 315 | General Education teachers | The study examines the relationships between Greek teachers’ perceived efficacy in classroom behavior management/discipline and their perceptions of inclusive education. | Quantitative method (Questionnaire including demographics/personal/professional characteristics part and SACIE-R (Teachers’ Sentiments, Attitudes and Concerns about Inclusive Education Revised) and teacher efficacy in classrooms management and discipline scales) | Scopus |

| Are Teachers’ Democratic beliefs about Classroom Life Associated with their perceptions of Inclusive Education? | 2021 | Stavroussi et al. (2021) | International Journal of Disability, Development and Education | 315 | General Education teachers | The study examines Greek in-service primary school teachers’ perceptions of inclusive education and the extent to which those perceptions are associated with democratic beliefs about classroom life. | Quantitative method (Questionnaire including demographics/personal/professional characteristics part and SACIE-R (Teachers’ Sentiments, Attitudes and Concerns about Inclusive Education Revised) and DTBS (Democratic Teachers’ Belief Scale) scales) | Scopus |

| Aspects of Greek Teachers Concerning Teaching within Co-Educational Classes: An Exploratory Approach to Elementary School | 2019 | Sakellariou et al. (2019) | Open Journal for Educational Research | 303 | General Education teachers | The study examines parameters relating to the co-education between SEN and non-SEN students, drawing conclusions about the attitudes, knowledge, and capability of Greek elementary school teachers regarding inclusive co-education. | Quantitative method (Questionnaire) | Eric |

| Special Teachers’ Educational Responses in Supporting Students with Special educational Needs (SEN) in the domain of Social Skills Development | 2016 | Vlachou et al. (2016) | International Journal of Disability, Development and Education | 40 | Special Education teachers | The study examines the responses of Greek Special Education teachers dealing with the difficulties experienced by SEN students in social domain. | Qualitative method (Semi-structured interview) | Scopus |

| A survey of Greek general and special education teachers’ perceptions regarding the role of special needs coordinator: Implications for educational policy on Inclusion and teacher education | 2011 | Agaliotis and Kalyva (2011) | Teaching and Teacher Education | 466 | General and Special Education teachers | The study examines the perceptions of Greek general and special primary teachers regarding the role and the professional characteristics of special needs coordinators (SENCOs) | Quantitative method (Questionnaire) | Scopus |

| The influence of teaching experience and professional development on Greek teachers’ attitudes towards Inclusion | 2007 | Avramidis and Kalyva (2007) | European Journal of Special Needs Education | 155 | General Education teachers | The study examines primary teachers’ attitudes towards the inclusion of SEN students in mainstream classrooms and the influence of teaching experience and professional development on their attitudes’ formation. | Quantitative method (Questionnaire including demographic section and My Thinking about Inclusion Scale) | Scopus |

| Thematic Category | Codes | Statements |

|---|---|---|

| Teacher-related constraints | Teachers’ insufficient training | “Lack of full training of teachers working in the ICs (inclusive classrooms) and lack of training and feedback from SEN co-ordinators” (general teachers) (Giavrimis, 2024a, p. 6) “Insufficient training of teachers in Inclusive Education” (general teachers) (Giavrimis, 2024b, p. 137) “Lack of training in Inclusive classroom management” (general teachers) (Lyra et al., 2023, p. 8) “Lack of adequate training (in strategies for SEN students’ social skills development)” (special teachers) (Vlachou et al., 2016, p. 88) |

| Teachers’ insufficient knowledge | “Limited knowledge of the special education field” (general teachers) (Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007, p. 382) | |

| Teachers’ attitudes | “Children attending IC may not participate in initiatives because teachers do not encourage them” (general teachers) (Giavrimis, 2024a, p. 7) “Teachers’ attitudes” (general teachers) (Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007, p. 383) | |

| Teachers’ experience | “Lack of experience of Inclusion” (general teachers) (Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007, p. 382) | |

| “Lack of experience (a) in planning, (b) in time management in co-teaching and, (c) in differentiated teaching” (general teachers) (Lyra et al., 2023, p. 7) | ||

| Teachers’ fears | “General education teachers talked about fundamental fears that touch upon their self-awareness and role” (general teachers) (Lyra et al., 2023, p. 8) “Fear of being exposed as not skilled enough or not effective enough in the eyes of their colleague” (special teachers) (Lyra et al., 2023, p. 9) “Fear of having more than one student with severe disabilities” (special teachers) (Lyra et al., 2023, p. 9) “Fear of change” (special teachers) (Lyra et al., 2023, p. 9) | |

| Resources and infrastructure | Teaching materials and resources | “Severe shortage of educational material…computer, Internet connection, educational games, cards, posters, etc.” (general teachers) (Giavrimis, 2024a, p. 6) “Lack of differentiated learning material… no differentiated exercises in books” (general teachers) (Lyra et al., 2023, p. 7) |

| Physical infrastructure | “Lack of appropriate facilities both in mainstream and even in special education schools (e.g., ramps for children with mobility disabilities) and technological support for children who may be visually or hearing disabled” (general teachers) (Giavrimis, 2024b, p. 143) “Lack of infrastructure… ramps, adequate architectural and spatial adjustments of classrooms, elevators” (general and special teachers) (Lyra et al., 2023, p. 7) | |

| Curriculum, time, and other systemic constraints | Curriculum | “The curriculum is very demanding…it is difficult for children with SEND and everyone else” (general teachers) (Giavrimis, 2024b, p. 144) “There was no curriculum (for Inclusive classrooms) for children with special educational needs” (general teachers) (Giavrimis, 2024b, p. 144) “The expectations for covering defined areas of the curriculum, (make) teachers feel stressed to achieve goals that concern mainly academic skills within a strict timeframe” (special teachers) (Lyra et al., 2023, p. 7) “Pressure to focus on SEN students’ academic skills (i.e., reading, writing, arithmetic) at the expense of other domains of development” (special teachers) (Vlachou et al., 2016, p. 88) |

| Time/Workload constraints | “Lack of time (to implement strategies for addressing SEN students’ Social Skills difficulties)” (special teachers) (Vlachou et al., 2016, p. 88) “Limited time” (general teachers) (Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007, p. 382) “Work overload” (general& special teachers) (Lyra et al., 2023, p. 8) | |

| Government/Schools | “With the institution of Parallel Support for a child with SEND, the state is reassured and believes it has no other ‘responsibility’” (general teachers) (Giavrimis, 2024b, p. 143) “The frequent displacement of teachers (many teachers work as substitutes) causes even more problems” (general teachers) (Giavrimis, 2024b, p. 143) “Lack of SEN teachers” (general teachers) (Giavrimis, 2024a, p. 6) “The continuous rearrangements that the Ministry of Education introduces…As…pointed out, over the last decades, it hasn’t been an unusual practice for Greek governments to revise or interrupt introduced rearrangements and new educational policies within short periods of time” (special teachers) (Lyra et al., 2023, p. 8) “Insufficient support from schools and local communities” (general teachers) (Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007, p. 382) | |

| Collaboration constraints | Limited/Absent collaboration | “collaboration between mainstream teachers and IC teachers… is only sometimes given” (general teachers) (Giavrimis, 2024a, p. 6) “Limited opportunities for collaboration” (general teachers) (Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007, pp. 382–383) |

| Culture of collaboration | “Teachers tend to be negative towards collaborative teaching, mainly due to issues of ‘ownership’ and leadership within the classroom” (special teachers) (Lyra et al., 2023, p. 8) | |

| SEN student-related barriers | SEN students’ behavior | “Offensive, violent or infringing behavior of SEN students” (general teachers) (Lyra et al., 2023, p. 6) |

| SEN students’ potential | “General education teachers expressed their concerns regarding specific SEN students’ potential (e.g., students with severe mental disabilities) to learn effectively in an inclusive class” (general teachers) (Lyra et al., 2023, p. 6) “Special education teachers also expressed their uncertainties in respect to whether SEN students can successfully attend the mainstream school. As reasons, they stated the severity of SEN” (special teachers) (Lyra et al., 2023, p. 6) | |

| Typical student-related barriers | Typical students’ reactions | “Typical students’ reactions to offensive, violent or infringing behavior of SEN students” (general teachers) (Lyra et al., 2023, p. 6) |

| Typical students’ attitudes | “Children do not participate in the school’s social life because of their challenges or adverse treatment from classmates” (general teachers) (Giavrimis, 2024a, p. 7) | |

| Parent-related barriers | SEN students’ parent-related barriers | “Families with low economic and educational backgrounds need more financial and educational capital to help their children effectively. Most students attending ICs come from low social strata, and their families struggle to provide them with the needed help” (general teachers) (Giavrimis, 2024a, p. 8) “The loose family structure makes it challenging to deal with children’s learning difficulties” (general teachers) (Giavrimis, 2024a, p. 8) “Some parents cannot accept the difficulties (of their SEND children)” (general teachers) (Giavrimis, 2024a, p. 8) |

| Typical students’ parent-related barriers | “However, parents often do not accept students attending IC and interfere, even during school hours. They fear that their children’s school performance will be affected or that there will be issues with SEND children’s behaviour” (general teachers) (Giavrimis, 2024a, p. 7) “Parental (of typical students) attitudes” (general teachers) (Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007, p. 382) |

| Ref. | Sample’s Geographical Distribution |

|---|---|

| (Giavrimis, 2024a) | Greek islands of North Aegean (Lesvos, Chios, Samos, Limnos) |

| (Giavrimis, 2024b) | Region of North Aegean |

| (Lyra et al., 2023) | Region of Attica |

| (Didaskalou et al., 2023) | North and Central Greece |

| (Stavroussi et al., 2021) | North and Central Greece |

| (Sakellariou et al., 2019) | Epirus Region |

| (Vlachou et al., 2016) | Broader Geographical area of Central Greece |

| (Agaliotis & Kalyva, 2011) | Mainland Greece |

| (Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007) | One region of Northern Greece |

| Thematic Category | Codes | Statements |

|---|---|---|

| Collaboration and support | Collaboration | “The collaboration of (mainstream/parallel support) teachers needs to be at the required level to produce better learning outcomes” (general teachers) (Giavrimis, 2024b, p. 143) “Participants reported that there should be a collaboration between all staff, which could make things better” (general teachers) (Giavrimis, 2024b, p. 143) |

| Additional teaching staff | “All teachers mentioned the need for more teaching staff (special education teachers, nurses, ergo therapists, and psychologists)” (general teachers) (Giavrimis, 2024b, p. 143) “Teachers opt for pastoral help by the parallel support educator as being the factor of uttermost importance” (general teachers) (Sakellariou et al., 2019, p. 113) “Both general and special educators believe that each Greek school should have a fulltime SENCO” (Special Needs Coordinator) (general and special teachers) (Agaliotis & Kalyva, 2011, p. 547) | |

| Collaborative networks | “Teachers focused on the need to create collaborative networks with regular education teachers, parents and especially external agencies such as psychological community-based services” (special education teachers) (Vlachou et al., 2016, p. 89) “Need of collaborative relationships with university staff” (general teachers)” (Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007, p. 383) “Consultation with teachers, specialists and parents” (general teachers) (Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007, p. 383) “Group discussions on inclusion practicalities” (general teachers) (Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007, p. 383) | |

| Teachers’ traits | Teachers’ behaviors | “All the participants stressed the catalytic importance of teachers’ behavior in socializing students attending IC” (general teachers) (Giavrimis, 2024a, p. 7) |

| Teachers’ experience | “High or even limited experience in teaching students with disabilities (compared to those with no experience), and those having interactions with people with disabilities, reported more positive overall perceptions of inclusive education” (general teachers) (Didaskalou et al., 2023, p. 10) “Need for direct teaching experiences with pupils with SEN” (general teachers) (Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007, p. 383) “Need for observation of other teachers in inclusive settings” (general teachers) (Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007, p. 383) “Exposition to children with SEN” (general teachers) (Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007, p. 383) | |

| Teachers’ beliefs | “Participants’ democratic beliefs about schooling, and specifically their Classroom Life Beliefs, were found to be strongly associated with their overall perceptions of inclusive education” (general teachers) (Stavroussi et al., 2021, p. 638) | |

| Teachers’ training | “Teachers with high levels of training in disabilities education, compared to those with no training at all, reported more positive overall perceptions of inclusive education” (general education teachers) (Didaskalou et al., 2023, p. 10) “In-service training” (general teachers) (Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007, p. 383) “Attending courses at the University” (general teachers) (Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007, p. 383) | |

| Teachers’ abilities | “Teachers’ abilities of dealing with SEN students’ behavioral problems” (general teachers) (Sakellariou et al., 2019, p. 113) | |

| Curriculum needs | Curriculum reform | “Need for modifications in the curriculum” (general teachers) (Sakellariou et al., 2019, p. 113) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sakellaropoulou, G.; Spyropoulou, N.; Kameas, A. Exploring Greek Primary Teachers’ Perspectives in Inclusive Education for Special Educational Needs (SEN) Students and Related Research Trends: A Systematic Literature Review. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 920. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070920

Sakellaropoulou G, Spyropoulou N, Kameas A. Exploring Greek Primary Teachers’ Perspectives in Inclusive Education for Special Educational Needs (SEN) Students and Related Research Trends: A Systematic Literature Review. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(7):920. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070920

Chicago/Turabian StyleSakellaropoulou, Georgia, Natalia Spyropoulou, and Achilles Kameas. 2025. "Exploring Greek Primary Teachers’ Perspectives in Inclusive Education for Special Educational Needs (SEN) Students and Related Research Trends: A Systematic Literature Review" Education Sciences 15, no. 7: 920. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070920

APA StyleSakellaropoulou, G., Spyropoulou, N., & Kameas, A. (2025). Exploring Greek Primary Teachers’ Perspectives in Inclusive Education for Special Educational Needs (SEN) Students and Related Research Trends: A Systematic Literature Review. Education Sciences, 15(7), 920. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070920