Abstract

Over the past decade, the mathematical performance of at-risk students has not improved and has, in fact, declined since 2020. Conceptual Model-Based Problem-Solving (COMPS) strategies have been studied by researchers in and outside of the U.S. To date, there is no systematic review evaluating this body of research. The purpose of this study was to conduct a systematic review evaluating the quality and evidence base of research studies that utilized COMPS strategies in helping students learn mathematics. A total of 20 studies involving students with disabilities or learning difficulties in mathematics, with grade levels ranging from third to eighth grade, were included in this review. We used Council for Exceptional Children quality indicators and What Works Clearinghouse standards to evaluate the methodology rigor of this body of research and determine the evidence base of the COMPS strategies. The results of this systematic review of the evidence base indicate that COMPS is an evidence-based practice particularly based on the single-case design studies identified in this review. Implications for future research and practices are discussed in the context of paradigm shifts in mathematics teaching and learning.

1. Introduction

Roughly 35% of the population experiences difficulties in learning mathematics, and an estimated 3–7% of people worldwide have a mathematics learning disability (Berch & Mazzocco, 2007; Hobri et al., 2021). Students in the U.S. are facing a math crisis marked by a performance decline that began more than a decade ago and accelerated sharply after the pandemic. The situation is more alarming for students with learning disabilities or difficulties in mathematics (LDM) who have exhibited greater achievement declines than their normal-achieving peers (U.S. Department of Education et al., 2024). This has caused an already existing achievement gap to become wider when compared to previous years. This widening gap proves that existing intervention practice has not been working well for students with LDM.

Mathematical achievement is a significant predictor of postsecondary outcomes, including employment and overall quality of life (Nasamran et al., 2017). Around the world, poor mathematics performance has been linked to reduced employment opportunities, lower wages, poorer financial well-being, and higher crime rates (Anser et al., 2020). Problem solving is the cornerstone of school mathematics. Mathematical word problems are verbal descriptions of problem situations in which mathematics operations must be applied to quantitative data found within the problem (Verschaffel et al., 2020). Mathematical word problem solving involves multiple cognitive processes (Gonsalves & Krawec, 2014). Students need to understand the information in the problem, make a solution plan, and apply strategies to solve for the answer (Montague et al., 2011).

1.1. Students with Disabilities and Diverse Learning Needs

Students with disabilities including individuals with mathematics learning disabilities (MLD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), intellectual disability (ID), and other special needs are often disadvantaged in attention, working memory, as well as planning and organization (Fuchs et al., 2014; Geary et al., 2007; Zentall, 2013). Students with MLD show persistent difficulties in counting sequences, “understanding and representing numerical magnitude,” difficulties in retrieving basic facts, error detection, word problem solving, and slow growth in learning mathematical procedures (Geary, 2011, p. 250). While visual memory has been deemed as strength of children with ASD, they lack organizational strategies to support memory. They tended to focus on detail rather than overall picture (Boutot & Myles, 2011). Students with mild ID often show delays in number sense and abstract reasoning, sharing some common characteristics with students with MLD.

1.2. Intervention Strategies for Students Struggling with Mathematics

Recently, researchers in the United States (Fuchs et al., 2021) have made specific arguments about the problem-solving process that might help students with disabilities and who are struggling in solving mathematical problems. In teaching elementary mathematics to students with LDM, the guidelines provided by the U.S. Institute of Educational Sciences (IES) suggest the use of systematic and explicit instruction through sequencing (e.g., concrete, semi-concrete, and abstract instructional sequences), using worked-out examples, providing visual and verbal supports, and teaching precise mathematical language (Fuchs et al., 2021). Existing metanalyses on word problem solving for students with learning difficulties (Myers et al., 2022) as well as several other metanalysis/research synthesis studies (e.g., Hughes et al., 2014; Kim & Xin, 2024; Zhang & Xin, 2012) support explicit teaching of problem structure representations and model-based problem-solving strategies.

1.3. Schema-Based Instruction

Scholars, particularly in the field of special education in the United States, promoted schema-based instruction (SBI, Cook et al., 2020) as one of the potential evidence-based practices. SBI emphasizes semantic analysis of word problems and representation of information in various schematic diagrams that are specific to different problem types (e.g., change, group, and compare) (Carpenter et al., 1999; Van de Walle et al., 2013). In schema-based instruction, students are trained to code the problem into types based on the word problem story situations (e.g., change, combine or group, and compare or difference, as in additive word problems). After that, students need to decide whether to add or subtract to solve the problems (Hord & Xin, 2013). The findings from existing research show its effectiveness in improving mathematics problem solving of students with MLD, ASD, and mild ID (Cook et al., 2020; Jitendra et al., 2016; Powell & Fuchs, 2018; Root et al., 2021).

SBI has its root in psychology (Marshall, 1995). While SBI moves students above and beyond picture drawing (e.g., number of red marbles and blue marbles), it emphasizes semantic analysis of a word problem story (e.g., change, combine, or compare story situations) and represents the story in its corresponding schematic diagrams (e.g., beginning set, change set, and ending set for the change problem schema). Then, students are taught to rely on memorized rules (e.g., if the total is given, then subtract) to decide which operation sign to use in the solution.

Cook et al. (2020) conducted a systematic literature review, using the U.S. Council for Exceptional Children’s (CEC) quality indicators and the evidence base standards (CEC, 2014), to determine whether SBI was established as evidence-based practices to support the learning of mathematics problem solving of students with learning disabilities in K-12 school settings. A total of ten studies met the inclusion criteria, including eight single-case design studies and two group design studies. The authors concluded that SBI was a “potentially evidence-based practice” (p. 82) due to limited number of participants.

1.4. Model-Based Problem Solving

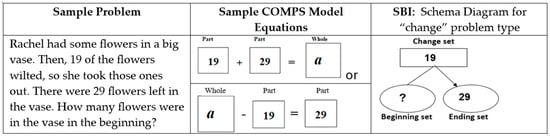

Embracing the best practices of Eastern and Western mathematics teaching, Conceptual Model-based Problem Solving (COMPS, Xin, 2012) has emerged as a powerful strategy that goes above and beyond semantic comprehension of word problem story situations; it focuses students’ attention on identifying and expressing mathematical relations in the algebraic model-equations. Existing research has shown that many students experience difficulties in making a “mental leap” from real-world-situated word problem story comprehension to a mathematical model or algebraic equation for effective and efficient problem solving (Blomhøj, 2004). One of its distinctive features is its emphasis on students’ understanding of mathematical relations decontextualized from variously situated word problems and represents such relations in a cohesive model equation (Xin, 2019). And then it is the model equation that drives the solution plan. Figure 1 compares COMPS and SBI representations.

Figure 1.

COMPS diagram equations (2nd column) in contrast with the SBI (3rd column).

In fact, much recent research in SBI has been taking advantage of and promoting COMPS model equations (Xin, 2008, 2012) to help students solve mathematical word problems involving individuals with MLD, ASD, and mild ID (e.g., Cox et al., 2021; Powell & Fuchs, 2018; Root et al., 2022, 2024). During the past decade, the COMPS strategies have been used within and outside of the United States to help improve word problem-solving performance of students with LDM (Xin et al., 2011), ASD (Cox et al., 2021; García-Moya et al., 2023; Root et al., 2022), and English learners (Wang et al., 2025; Xin et al., 2020a), just to name a few. This trend underscores the significance of assessing COMPS research and determining its quality and evidence base.

Despite the growing body of empirical studies that examined COMPS strategies on improving math problem solving of students with diverse needs, to date, no systematic literature review has evaluated this research base. Therefore, the purpose of this study was twofold: (a) to conduct a systematic review of empirical studies that used COMPS strategies to help mathematical problem solving of students with LDM and (b) to evaluate its quality and determine its evidence base. The research questions were as follows:

- According to the Council for Exceptional Children Quality Indicators (CEC, 2014), what was the quality of the extant COMPS research studies?

- According to CEC (2014) standards for evidence-based practices and What Works Clearinghouse Procedures and Standards Handbook (WWC, 2022), did COMPS intervention meet the criteria as an evidence-based practice (EBP)?

2. Methods and Data Source

2.1. Literature Search and Selection Procedures

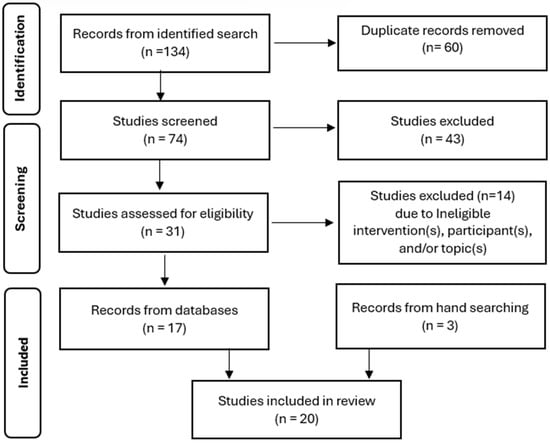

The systematic review employed the procedure of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Moher et al., 2009) to identify studies examining the effects of COMPS on improving the mathematics problem-solving performance of students with LDM. A comprehensive search was conducted using databases including Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC), PsycINFO, Education Source, and Web of Science. We utilized various combinations of key terms, including conceptual model-based problem solving or COMPS* or model-based problem solving or MBPS AND math* or problem solving or word problem solving AND disab* or learning difficulties or learning disabilities or at-risk or special education or MLD (math* learning disabilities) or MD (math* disabilities) or dyscalculia or LDM or ASD or ID. This search resulted in 134 studies. After removing duplicates (60), we had 74 studies. Then, we carefully screened titles and abstracts based on set inclusion and exclusion criteria described as follows:

Studies were included if they (a) were published in peer-reviewed journals between 2008 and July 2025 (note that the COMPS approach was first published in 2008 in the Journal of Special Education, Xin et al., 2008); (b) employed experimental designs or quasi-experimental designs including single-case designs (SCDs) or group designs; (c) included the COMPS strategies in the intervention to support students’ learning of mathematics problem solving (note: the study was included as long as the intervention included the use of COMPS diagram equations, the hallmark of the COMPS program); (d) included word problem-solving performance as part of the dependent measures; and (e) involved students with disabilities or LDM.

The screening of the abstract resulted in the exclusion of an additional 43 studies. Finally, a full-text readthrough was carried out on the remaining 31 studies. A coding book was used by each coder for record keeping and reliability check. Following the full-text review, 14 studies were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. As the final step in the literature search, we reviewed the references of the identified studies to discover qualified studies that were missed from the electronic database search. This resulted in an additional three studies. By combining these two phases of search, we identified a total of 20 studies to be included in this literature review. Figure 2 presents the PRISMA follow chart.

Figure 2.

Article search and identification procedures (PRISMA, Moher et al., 2009).

2.2. Coding Procedures for Methodology Rigor and Evidence Base

In 2014, the Council for Exceptional Children (CEC) established guidelines for assessing the quality of intervention research using a single-case design (Horner et al., 2005) and group design (Gersten et al., 2005). We used the quality indicators (QIs) stipulated by the CEC (2014) Standards for Evidence-based Practices in Special Education to assess the methodology rigor of the identified 20 studies and determine the evidence base.

CEC QIs encompass eight variables, which are listed in Table 1: Q1 = context and settings; Q2 = participants; Q3 = intervention agent; Q4 = description of practice; Q5 = implementation fidelity; Q6 = internal validity; Q7 = outcome measures/dependent variables; and Q8 = data analysis. Except for QI 1 and QI 8, all other QIs entail one or more sub-indicators that are suitable for either the single-case design studies or group comparison studies or both types of studies, resulting in a total of 22 QIs for single-case design studies and 24 indicators for group design studies.

Table 1.

Results of CEC quality indicator coding.

Each indicator and its sub-indicators will receive a rating: zero points for the QI “not met” or one point if the QI is met. Detailed introduction and application of each QI can be found in CEC (2014). We created a coding book based on the CEC’s eight QIs to assist with the evaluation of single-case or group design studies, respectively. Each indicator and its sub-indicators were rated as met or not met. All studies received independent coding by the authors. Inter-rater agreement was 94%, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion and revisiting the definition of QIs until consensus was reached.

According to the CEC (2014) standards for evidence-based practices in special education, only studies that met all QIs (i.e., a total of 22 QIs for single-case design and a total of 24 QIs for group design studies) would be considered methodologically sound and be included in the database for evaluation of the intervention effects and classification of the evidence base. Therefore, our reporting of the treatment effect and evaluation of whether the COMPS intervention program met the evidence base criteria were based on studies that met all CEC QIs.

3. Results

3.1. Description of Included Studies

3.1.1. Study Design

Out of 20 studies included in this review, 16 studies were single-case design studies, and 4 used group comparison designs. All 16 single-case design studies used a multiple-baseline design or an adapted multiple probe design to study the functional relationship between the COMPS intervention and the students’ performance in word problem solving. Three out of the four (75%) group design studies (Griffin et al., 2018; Xin et al., 2011, 2017) applied a randomized controlled trial (RCT) study design for comparing the effect of the COMPS intervention with a “business as usual” (BAU) control condition. Xin et al. (2017) compared the COMPS delivered by an intelligent tutor with the BAU condition taught by the schoolteachers. Xin et al. (2011) compared the COMPS with the BAU condition; the instructors, involving both the research team members and the schoolteachers, were counterbalanced across both conditions. In the study by Griffin et al. (2018), researchers delivered COMPS intervention to the experimental group. In contrast, the students in the BAU condition did not receive intervention in mathematical problem solving; they “received instruction or had independent study time in content areas other than mathematics (i.e., reading, written expression).” (p. 154). Nonetheless, both conditions were receiving regular mathematics instruction during school hours.

3.1.2. Participants

The 20 identified studies included a total of 150 participants with disabilities or LDM, with grade levels ranging from third to eighth grade. Specifically, fifteen studies included elementary students (n = 133), four studies included middle school students (n = 16), and one study (Polo-Blanco et al., 2022) included one 14-year-old student with severe autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and intellectual disability (ID) in a special education program.

All the studies provided detailed information about the participants’ diagnosis or at-risk status. Specifically, 5 out of 20 studies (25%) included students with ASD. The rest of the studies involved students with learning disabilities or learning difficulties in mathematics (LDM) or LDM along with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), ID, or English language learner status (ELs).

3.1.3. Targeted Math Problem-Solving Skills

Regarding the word problem-solving tasks involved, 15 out of 20 studies (75%) focused on multiplication and division word problem solving, in which 2 studies extended COMPS multiplicative reasoning to solve geometry problems pertinent to area and volume (e.g., Hord & Xin, 2015; Xin & Hord, 2013) and 2 studies extended COMPS to solve Cartesian product problems (García-Moya et al., 2023; Polo-Blanco et al., 2022). Four studies (20%) involved students in solving addition and subtraction word problems. One study (5%) (Xin et al., 2008) targeted both additive and multiplicative word problem solving, in which participating students were taught the COMPS strategies to solve either additive word problems or multiplicative problems based on the needs of each individual student with LDM.

3.1.4. Intervention Procedure

All studies provided detailed descriptions of intervention procedures and materials. For instance, Xin et al. (2023a) presented information about the model-based problem-solving computer tutor illustrated with sample screenshots from each of the three modules. García-Moya et al. (2023) depicted their modified COMPS intervention materials for students with ASD through demonstration of the diagram equations used as part of the intervention in the study. Several other studies (e.g., Xin, 2019) documented the teaching transcript to showcase the interaction between the teacher and the students during the problem-solving process. All studies utilized COMPS diagrams in various formats except for two studies that extended the COMPS diagram equations to solve Cartesian product problems (Polo-Blanco et al., 2022; García-Moya et al., 2023) and one study that combined COMPS with CSA instructional sequences to teach geometry word problem solving pertinent to the concept of area and volume (e.g., Hord & Xin, 2015).

3.1.5. Intervention Agent

Regarding the instructors who delivered the COMPS intervention, three group design studies (e.g., Xin et al., 2023a), including two randomized controlled trial (RCT) studies (Xin et al., 2011, 2017), involved schoolteachers in carrying out the instruction. In addition, two single-case design studies (Root et al., 2022; Polo-Blanco et al., 2022) involved schoolteachers (the special education teachers) in implementing the intervention during the special education class sessions. Among all other studies, the research team members conducted the intervention. As for the instructional settings, except for the study by Root et al. (2022), the interventions were conducted in small groups either in pull-out settings during the school day or during the afterschool program hours.

3.2. Presence of QIs

We applied the CEC’s eight quality indicators to assess methodological rigor. To receive a score of “met,” all sub-indicators under each variable must be fulfilled. If one or more criteria in an indicator were not reached in a study, the study will receive a rating of “not met” for this indicator. Table 1 presents the coding results of the CEC QIs. The number of sub-indicators being met is listed under each QI. The last row (numerator) shows the number of studies fully satisfied with each QI.

As demonstrated in Table 1, all 20 studies met the QIs of context and setting, participants, description of practice, internal validity, outcome measures/dependent variables, and data analysis. One study (Xin, 2008) did not clearly describe the intervention agent. Mostly, the included studies fell short of meeting the QI in reporting the implementation fidelity. Fifteen out of twenty studies (75%) fully met this QI. It should be noted that when a study used an intelligent tutor (e.g., Xin et al., 2017) or computer tutor (e.g., Xin et al., 2023a) as the intervention agent, we considered that the studies met the implementation fidelity, QI 5.0, if they met the following criteria simultaneously: (1) it was explicitly stated in the article that the students were required to complete each intervention task in pre-determined order delivered by the intelligent tutor or computer tutor, (2) utilized tools (i.e., screen capture, mouse clicks, or movement) for monitoring students’ engagement and learning progress and/or used computer log data to monitor student input/progress, and (3) the computer program consistently enforced the dosage and sequence of instructional modules. Given this, the studies were deemed as meeting the implementation fidelity quality indicators of properly delivering and tracking progress across different stages, participants, and settings.

Four single-case design studies did not fully meet the implementation fidelity QI (Ma & Xin, 2024; Xin et al., 2020a; Xin, 2008, 2019; Xin & Hord, 2013). For instance, the study by Xin et al. (2020a) investigated the effect of the COMPS computer tutor on additive word problem solving of English learners (ELs) with LDM. Xin et al. (2020a) did not provide the narrative in their publication that the participating students had to follow through the COMPS computer tutor or the computer tutor enforced the lesson sequences and intervention dosage, and the students’ engagement with the computer tutor was monitored by computer log of each participant’s keyboard input, mouse movement, etc., even though the COMPS tutor was the same program as the one investigated in Xin et al.’s (2023a) study. We still coded the study (Xin et al., 2020a) as not meeting the implementation QI simply because the statement was absent from the article. Finally, the studies conducted by Ma and Xin (2024), Xin (2008, 2019), and Xin and Hord (2013) also did not report the implementation fidelity data in their publications.

In summary, 15 out of 20 studies fully met the CEC QIs and were considered methodologically sound; they were included in the database for further evaluation of the evidence base. The five studies that were excluded from the EBP consideration (Ma & Xin, 2024; Xin et al., 2020a; Xin, 2008, 2019; Xin & Hord, 2013) included three students with ASD, five students with learning disabilities, three with mild ID, four ELs with LDM, and three students with LDM, a total of eighteen elementary students.

Table 2 presents descriptive information of these 15 studies. The 15 studies included a total of 132 participants with LDM, of which 30 students were diagnosed with learning disabilities, 3 with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, 3 with ID, 14 with ASD, 3 with writing difficulties, and 4 as English language learners. In addition, one study (Griffin et al., 2018) included eight students with disabilities, although the study did not specify the disability categories. The rest of the participants were identified as at risk or experiencing difficulties in mathematics (LDM).

Table 2.

Descriptive information of methodologically sound studies.

3.3. COMPS Intervention

Across the 15 studies that met the QIs, the COMPS strategy was applied to teach (a) additive word problem solving (including stories situations such as “combine,” “join-in,” and “separate-from,” with either the part or the whole as the unknown quantity, and additive compare, with either the smaller, bigger, or the difference quantity as the unknowns), (b) multiplicative word problem solving (including story situations such as rate × quantity, measurement division, fair share, and multiplicative comparison with either the compared or the referent quantity or the multiplier (scalar) as the unknowns), (c) Cartesian product problem solving, and (d) geometry pertaining area and volume problem solving (Van de Walle et al., 2013). The additive and multiplicative word problems addressed in these studies are typically found in elementary mathematics curricula, which roughly represent about 67% of the elementary mathematics content (Xin et al., 2012). Geometry problem solving and Cartesian problem solving are perhaps part of the 5th grade and middle school mathematics curricula.

3.4. Applying COMPS Strategy to Solve Additive and Multiplicative Word Problems

When using COMPS strategy to teach additive word problems, the focus was for students to represent the quantitative relations, decontextualized from the word problems, in the part–part–whole model equation, for instance, to solve this word problem: “Rachel had some flowers in a big vase. Then, 19 of the flowers wilted, so she took those ones out. There were 29 flowers left in the vase. How many flowers were in the vase in the beginning?” Unlike the SBI, students were not required to recognize it as a “change” problem situation (where there is a change in time) and map them into the corresponding schema diagram (see Figure 2, column 3, for the schema diagram, adapted from Xin, 2019, p. 142). Instead, students who engaged in COMPS would be charged to discover the mathematical relations between the quantities (e.g., whether it is the relation of “part and part makes up the whole”, see Figure 2, column 2) based on their comprehension of the problem.

And as needed, students will be supported with the Word Problem Story Grammar (Xin et al., 2008) self-prompting questions: “Which sentence (or question) talks about the “whole” or “combined” quantity?” “Which sentences tell about the two parts that make up the whole?”; these represent the quantities in the mathematical model equation. To solve this specific word problem (“Rachel had some flowers in a big vase. Then, 19 of the flowers wilted, so she took those ones out. There were 29 flowers left in the vase. How many flowers were in the vase in the beginning?”), students understood that the number of flowers in the vase, before some of them wilted, was the total (whole) or the bigger quantity, and the # of followers that were wilted (part 1) and the # of followers left in the vase (part 2) were the two parts that make up the whole (the beginning amount). Based on that understanding, students were able to map the three quantities into the PPW diagram equation (P + P = W), as shown in the second column in Figure 2.

As for multiplicative word problem solving, the existing literature, including studies that named their interventions as SBI or modified SBI (MSBI) have embraced the COMPS diagram equations (Xin, 2008; Xin et al., 2008) for teaching students with LDM, including individuals diagnosed with ASD, ID, ADHD, as well as ELs (Cox et al., 2021; Root et al., 2022; Xin et al., 2008, 2017). For instance, Cox et al. (2021) utilized the COMPS strategy to teach middle school students with ASD to solve multiplicative problems. Specifically, the COMPS diagram equation (“Compared/product = relation/multiplier x reference unit”, p. 331, taken from Xin, 2008, p. 540) was used to teach participants solve multiplicative comparison problems. Students were taught to “diagram the relationship,” “write the equation or number sentence,” “solve and write answer,” and check whether the “answer makes sense” (Cox et al., 2021, p. 331). Similarly, Root et al. (2022) took advantage of the COMPS diagram equation (as shown in their article, p. 42, Figure 1) to teach six middle school students with ASD/ID to solve multiplicative problems for instance. The findings from Cox et al. (2021) showed that students improved performance after the intervention and maintained their performance 4 to 8 weeks after the intervention. In addition, all participants generalized the skills learned to solve novel multiplicative comparison problems that involve irrelevant information. The findings from Root et al. (2022) indicated that six middle school students improved their problem-solving performance following the intervention showing a functional relation between the intervention and the improved performance.

3.5. COMPS-Based Computer Tutors

Other than human delivered intervention, Xin and her research team developed and evaluated an intelligent tutor (PGBM-COMPS, Xin et al., 2017) and a computer tutor (Xin et al., 2020a) on the basis of the COMPS program, integrating research-based practices from mathematics education and special education. Field studies were conducted to evaluate the effect of computer tutors. Xin et al. (2017) conducted an RCT study to evaluate the effect of the PGBM-COMPS intelligent tutor on multiplicative word problem solving of elementary students with LDM. Specifically, the COMPS program was augmented with a turn-taking game called “please go and bring me” (PGBM) that was designed to nurture a learner’s construction of fundamental ideas in multiplicative reasoning before students learn multiplicative problem solving using the COMPS strategy. Findings indicated that participating students in the PGBM-COMPS group not only outperformed the BAU group, who received instruction from schoolteachers, on the criterion test, but more importantly, the PGBM-COMPS group also demonstrated significant improvement on the problem-solving subtest of a norm-referenced standardized assessment, SAT-10 (Harcourt Assessment, 2004), following the intelligent tutor-assisted intervention.

Xin et al. (2023a) conducted another RCT study evaluating the effect of the COMPS-RtI, a computer tutor that was built on the COMPS program, on additive word problem solving of elementary students with LDM. The COMPS-RtI computer tutor also augmented the COMPS program with a module that nurtures students’ construction of the concept of “composite unit”, a fundamental mathematical idea that naturally leads to the additive reasoning (i.e., part and part makes up the whole) and problem solving. Findings from this study indicated that the COMPS-RtI tutor boosted participants’ performance above and beyond the BAU comparison group who were taught by the schoolteacher following the traditional teaching practices. In addition, the COMPS-RTI group improved their performance on an algebraic model expression test as well as a curriculum-based assessment, both served as generalization assessment.

3.6. Applying COMPS to Solve Cartesian Product Problems

Polo and her colleagues systematically adapted the COMPS strategy to teach individuals with ASD to solve multiplicative word problems. The research team extended the COMPS strategy to solve Cartesian product problems. For instance, García-Moya et al. (2023) employed a multiple-baseline-across-participants design to study the effect of the COMPS program on solving Cartesian product problems with three third- and fourth-grade students with ASD during the summer school. The COMPS was supplemented with augmentative and alternative communication systems as well as drawings to facilitate participants’ understanding of the problem; they were taught to “read the problem,” “choose and put a pictogram sentence,” “draw/choose a drawing,” write the numbers within the diagram equation, write the operations, and solve the problem (García-Moya et al., 2023, p. 249). The results of the study demonstrated an immediate improvement in the dependent measures for all three participants. In addition, the participants generalized their learned strategies to solve two-step problems involving addition and multiplication.

3.7. Extending COMPS to Solve Geometry Word Problem Solving

Hord and Xin extended the multiplicative reasoning that was emphasized in the COMPS program to solve geometry word problems pertinent to the concepts of area and volume. Hord and Xin (2015) applied a multiple-probe design across participants and evaluated the effect of the COMPS program on teaching area and volume problem solving to sixth-grade students with mild ID. The study accentuated the concrete-semi concrete-abstract (CSA) instructional sequence to support the three sixth-grade students with ID. The students followed the instruction sequence and learned to solve the following problem types: area of rectangle, volume of rectangular prism, area of triangle, volume of triangular prism, area of circle, and volume of cylinder using the COMPS strategies and diagram equations. During the phase of concrete level of instruction, “tape measures, wooden cubes, and plastic unit squares” were used to “measure items such as tabletops, cabinets, flags, windows, and cans of food.” (p. 123). Particularly, unit squares/tiles or cubes were used to create concrete models. Drawings were used during the semi-concrete phase, which facilitated the transition to the abstract mathematical model equations. Findings indicated that the COMPS program was effective for teaching the participants to “solve some of the area and volume problems they are expected to solve at grade level.” (p. 126).

3.8. COMPS-Based Problem Posing and Problem Solving

Finally, Yang and Xin (2022) and Wang et al. (2025) extended the COMPS program to engage students in problem posing based on a COMPS diagram equation to promote active engagement and deeper understanding mathematics learning of students with LDM. Taking advantage of the COMPS unified diagram equations and integrating research-based practices from mathematics education, middle school students with learning disabilities engaged in structured problem posing and problem solving pertaining multiplicative comparison problem situations. The students learned how to represent and solve the problems using the COMPS diagram equations (i.e., unit × multiplier = product). Then using the “What If NOT” strategy (Brown & Walter, 2005), students learned to pose specific structured problems when one of the elements in the COMPS diagram equation was unknown (i.e., what if the Unit is Not known?). Results from this study indicate that the participating students not only improved their problem-solving skills but also problem-posing skills.

Most recently, Wang et al. (2025) adapted the problem-solving and problem-posing strategies from Yang and Xin (2022) and integrated the COMPS-based problem-posing strategy with explicit systematic teaching on writing skills to facilitate the problem posing of participating students. The study involved three third-grade students with mathematics and writing difficulties in solving and posing equal-group problems (e.g., “There are 3 apples in each basket. How many apples are there if you have 4 baskets of apples?”). The intervention joined together (a) the COMPS strategy teaching using the unified diagram equation (number of groups × number of items in each group = total number” (Xin et al., 2008; Xin, 2012) and (b) explicit teaching on writing involving “a six-element sentence-writing convention checklist” (p. 6). Results from this study show that participants improved their performance on solving and posing equal-group word problems; they also improved on their writing skills that were measured by total number of words written, words spelled correctly, and correct writing sequence.

3.9. Evidence-Based Classification of COMPS

To determine evidence base for SCD studies, we relied on the 5-3-20 criteria referenced in What Works Clearinghouse (WWC, 2022), combining both WWW and CEC (2014) evidence classifications standards. That is, at least five studies should meet the standards for methodology rigor; and these studies should be conducted by at least three different research teams with no overlapping authorship and from different institutions and involving a combined total of at least 20 participants (cases). Findings from this review establish the evidence base of COMPS for improving word problem-solving skills for students with LDM because it met the 5-3-20 criteria. In this review, there were 11 SCD studies that met the methodology rigor, and they were conducted by at least three independent research teams from different institutions (e.g., Xin et al., 2008, Midwestern U.S.; Cox & Root, 2021, Southeastern U.S.; Polo-Blanco et al., 2022, Spain), involving a total of 42 participants. In addition to the treatment effects reported by these quality studies, we calculated the Tau-U effect for each of the SCD studies that did not report the effect size. As shown in Table 3, all the 11 high-quality SCD studies showed positive effects for all participants, with no negative effects.

Table 3.

Effects of the COMPS on student outcomes.

Above and beyond, based on the four group design studies (including three RCT studies), according to the criteria set by WWC (2022), (a) the intervention must show statistically significant positive effects on relevant outcomes, and (b) evidence must come from at least two studies conducted by different research teams. In addition, the studies must include a sufficient number of participants and be conducted in educationally relevant settings. As shown in Table 2 and Table 3, all four group design studies met the CEC quality indicators, and they showed large effect sizes (range = 0.6 to 1.99) on relevant outcomes. In addition, the studies were conducted by at least two different research teams (e.g., Xin et al., 2017; Griffin et al., 2018). While WWC did not specify a fixed number, a total of 90 participants were included in the four group design studies, including students with learning disabilities, ASD, ID, LDM, and other disabilities. In summary, the strong evidence base established by SCD studies plus the evidence from the group design studies together supports a well-founded argument that the COMPS has been established as an evidence-based practice to support the learning of mathematics problem solving for elementary and middle school students with LDM.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to conduct a systematic literature review of empirical studies that evaluated the effect of COMPS strategies on the mathematics word problem-solving performance of students with LDM and to evaluate its quality and determine its evidence base.

4.1. The Quality of the COMPS Research and the Establishment as an EBP

We aimed to answer two research questions: What was the quality of the COMPS research studies? Did the COMPS intervention meet the criteria as EBPs? After applying the CEC quality indicators and the evidence-base standards (2014), as well as the WWC (2022) evidence classifications, we can conclude that the COMPS has been established as an evidence-based practice to promote the learning of mathematics problem solving of students with LDM.

Specifically, we reviewed a total of 20 studies, including 16 SCD studies and 4 group design studies. Following the quality indicator review, 15 out of 20 (75%) studies met all the quality indicators, which included 11 SCD studies and all 4 group comparison studies. Mostly, the five studies that did not fully meet the QIs failed to report the implementation fidelity, including duration and frequency. It should be noted that four out of the five studies that did not fully meet the QIs were published in non-special education journals (e.g., Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, The Journal of Mathematical Behaviors, Reading & Writing Quarterly, and ZDM). Then, we examined the treatment effect of the 15 quality studies and applied the WWC and CEC standards for evidence-based practice in special education. We came to the conclusion that COMPS has been established as an “evidence-based practice” based on both the SCD and group design study databases.

4.2. Limitations and Future Studies

As the purpose of this study was to evaluate whether the COMPS intervention program can be considered an evidence-based practice to support the learning of mathematical problem solving of students with LDM, we targeted the studies that evaluated the effect of the COMPS strategy. In the case that an empirical study did not spell out the term COMPS in their publications but used the COMPS diagram equations (e.g., unit rate x # of units = product) as part of the intervention, we may not have been able to find these articles. The studies that were included in this review are the ones that we were able to find through our database search and reference search of the articles that we found. It is likely that the database was not exhaustive.

As for the limitations of the research studies that were included in this review, existing research (e.g., Cook et al., 2020) has acknowledged that most of the empirical studies included in this review were carried out by the research team. In our review, in 5 out of 15 studies (33%), the database used for evidence base decision making included schoolteachers in carrying out the instruction (Root et al., 2022; Polo-Blanco et al., 2022; Xin et al., 2011, 2023a, 2017). This result seems similar to what was found by Cook et al. (2020), where 70% of the SBI interventions were delivered by researchers. In our review, ten studies (67%) involved the researchers in implementing the intervention, although some of them might have been schoolteachers in the past (e.g., Hord & Xin, 2015; Xin, 2019). In addition, although there were four group design studies involving a total of 90 students, most of the studies included in this review were SCD studies (16). Future research perhaps should conduct more RCT studies that include a larger sample size to expand the existing evidence base.

4.3. Practical Implications

In the field of mathematics education, there has been a discussion of two paradigms in solving word problems: operational vs. relational operational paradigms. The operational paradigm directs students’ attention to translating words found in the word problem into an operational sign for calculating the solution, as it is believed that decision making on the operation is essential in word problem solving (Polotskaia & Savard, 2018). In contrast, the relational paradigm focuses on students’ understanding of mathematical relations in the problem. The COMPS intervention strategies align with the relational paradigm and intend to help students understand mathematical relations rather than focusing on whether to add or subtract or whether to multiply or divide. As indicated by scholars in the field who have adopted the COMPS in their teaching/research, “COMPS unifies different problem types and schema diagrams under one algebraic model equation, and advances student thinking to an algebraic level of operation while fostering meaningful connections between mathematical ideas” (Polo-Blanco et al., 2025, p. 26).

Considering research in mathematics education, often, students experience difficulties in making the mental leap from real-world-situated word problem stories to mathematical models (Blomhøj, 2004). The COMPS approach intended to teach problem solving that is based on students’ understanding of mathematical relations and express that relation in mathematical model equations to facilitate abstract level of thinking and generalized problem-solving skills. With a focus on mathematical relations in word problem solving, the model-based problem-solving approach promotes computational thinking by engaging students in constructing and applying generalizable algorithms. Integrating computational thinking into K–12 education is essential to prepare students for success in today’s technology-driven world. To change the current unsatisfactory mathematics performance of students with LDM and beyond, there is a critical need for a paradigm shift in mathematics teaching and learning.

Perhaps another advantage of using the COMPS strategy is that it levels the difficulty of solving various word problems. Unlike a traditional keyword-based strategy, where students often experience extreme difficulty in solving “inconsistent language” problems and commit high rate of reversing errors (see Xin et al., 2023b), the COMPS strategy equipped students with abilities to solve both consistent and inconsistent language problems, as the problem solving was driven by mathematical model equations rather than surface story features.

Across the publications that used and promoted the COMPS strategies, it is suggested that different levels of scaffolding might be applied for students with different disabilities. For instance, for students with ASD and students with MID, manipulatives with three dimensions, task analysis (break the task into small steps), and multiple levels of promptings (general verbal, specific verbal, direct modeling, etc., Browder et al., 2018) might be helpful to provide systematic instruction with more scaffolding support.

5. Conclusions

The numerous high-quality studies included in this review, both the SCDs and group design studies, seem to demonstrate that the COMPS is an evidence-based practice to support mathematics problem solving of students with LDM. Unlike existing strategies guided by operational paradigms, the COMPS program focuses more on promoting conceptual understanding of mathematical relations decontextualized from variously situated word problems, which promote generalized problem-solving skills, as demonstrated by numerous empirical studies (e.g., Xin et al., 2017; Polo-Blanco et al., 2022). One significant contribution of the COMPS strategies is that students no longer need to “gamble on” or rely on memorized rules to figure out the operation sign for solution because the COMPS model equation determines the operation needed for solution. The findings of this review boost confidence in using the COMPS strategy to support students’ learning of mathematics problem solving, particularly for students with LDM.

Given the studies identified in this review, over two-thirds of the COMPS interventions were implemented by research teams. How the COMPS program will be seamlessly integrated into the school mathematics curriculum carried out by schoolteachers/practitioners is a significant next step. More research is needed to further strengthen the current evidence base, and additional implementation studies are necessary to guide schoolteachers and practitioners in implementing the COMPS program as part of schools’ Tier I, Tier II, and/or Tier III interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.P.X.; Methodology, Y.P.X., Y.W., and B.Y.Y.; Validation, Y.P.X.; Formal analysis, Y.P.X., Y.W., B.Y.Y., and L.Y.; Investigation, Y.P.X., Y.W., B.Y.Y., and L.Y.; Resources, Y.P.X.; Data curation, Y.P.X. and Y.W.; Writing—original draft, Y.P.X., and Y.W.; Writing—review & editing, Y.P.X., Y.W., and B.Y.Y.; Visualization, Y.P.X., Y.W., and B.Y.Y.; Supervision, Y.P.X.; Project administration, Y.P.X., and Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| COMPS | Conceptual Model-based Problem Solving |

| ID | Intellectual Disability |

| LDM | Learning Difficulties in Mathematics |

| MLD | Mathematics Learning Disabilities |

| QI | Quality Indicator |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| SCD | Single-Case Design |

References

Note: the references (Cox & Root, 2021; García-Moya et al., 2023; Griffin et al., 2018; Hord & Xin, 2015; Ma & Xin, 2024; Polo-Blanco et al., 2022; Root et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2025; Xin, 2008, 2019; Xin & Hord, 2013; Xin et al., 2023a, 2020a, 2020b, 2012, 2017, 2008, 2011; Yang & Xin, 2009, 2022) are the studies included in this review.

- Anser, M. K., Yousaf, Z., Nassani, A. A., Alotaibi, S. M., Kabbani, A., & Zaman, K. (2020). Dynamic linkages between poverty, inequality, crime, and social expenditures in a panel of 16 countries: Two step GMM estimates. Journal of Economic Structures, 9(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berch, D. B., & Mazzocco, M. M. (2007). Why is math so hard for some children? The nature and origins of mathematical learning difficulties and disabilities. Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Blomhøj, M. (2004). Mathematical modelling: A theory for practice. In International perspectives on learning and teaching mathematics (pp. 145–159). National Center for Mathematics Education. [Google Scholar]

- Boutot, E. A., & Myles, B. S. (2011). Autism spectrum disorders foundations, characteristics, and effective strategies. Pearson Education, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Browder, D. M., Spooner, F., Lo, Y.-Y., Saunders, A. F., Root, J. R., Ley Davis, L., & Brosh, C. (2018). Teaching students with moderate intellectual disability to solve word problems. The Journal of Special Education, 51(4), 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S. I., & Walter, M. I. (2005). The art of problem posing. Psychology Press. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781410611833 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Carpenter, T., Fennema, E., Franke, M., Levi, L., & Empson, S. (1999). Children’s mathematics: Cognitively guided instruction. Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, S. C., Collins, L. W., Morin, L. L., & Riccomini, P. J. (2020). Schema-based instruction for mathematical word problem solving: An evidence-based review for students with learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 43(2), 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council for Exceptional Children (CEC). (2014). Council for exceptional children standards for evidence-based practices in special education. Available online: https://exceptionalchildren.org/sites/default/files/2021-04/EBP_FINAL.pdf?srsltid=ARcRdnq2bLU_NiVVrycLmdMZzd0i8ARUcnsydWF8HPH5aXsZZxEhtj78 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Cox, S. K., & Root, J. R. (2021). Development of mathematical practices through word problem–solving instruction for students with autism spectrum disorder. Exceptional Children, 87(3), 326–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S. K., Root, J. R., Goetz, K., & Taylor, K. (2021). Modified schema-based instruction to encourage mathematical practice use for a student with autism spectrum disorder. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 56(2), 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, L. S., Newman-Gonchar, R., Schumacher, R., Dougherty, B., Bucka, N., Karp, K. S., Woodward, J., Clarke, B., Jordan, N. C., Gersten, R., & Jayanthi, M. (2021). Assisting students struggling with math: Intervention in the elementary grades (WWC 2021006). National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE). Institute of Education Sciences. U.S. Department of Education. Available online: http://whatworks.ed.gov/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Fuchs, L. S., Schumacher, R. F., Sterba, S. K., Long, J., Namkung, J., Malone, A., Hamlett, C. L., Jordan, N. C., Gersten, R., Siegler, R. S., & Changas, P. (2014). Does working memory moderate the effects of fraction intervention? An aptitude-treatment interaction. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Moya, M., Polo-Blanco, I., Blanco, R., & Goñi-Cervera, J. (2023). Teaching cartesian product problem solving to students with autism spectrum disorder using a conceptual model-based approach. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 38(4), 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geary, D. C. (2011). Consequences, characteristics, and causes of mathematical learning disabilities and persistent low achievement in mathematics. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 32(3), 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geary, D. C., Hoard, M. K., Byrd-Craven, J., Nugent, L., & Numtee, C. (2007). Cognitive mechanisms underlying achievement deficits in children with mathematical learning disability. Child Development, 78(4), 1343–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersten, R., Fuchs, L. S., Compton, D., Coyne, M., Greenwood, C., & Innocenti, M. S. (2005). Quality indicators for group experimental and quasi-experimental research in special education. Exceptional Children, 71(2), 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierut, J. A., Morrisette, M. L., & Dickinson, S. L. (2015). Effect size for single-subject design in phonological treatment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 58(5), 1464–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonsalves, N., & Krawec, J. (2014). Using number lines to solve math word problems: A strategy for students with learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 29(4), 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, C. C., Gagnon, J. C., Jossi, M. H., Ulrich, T. G., & Myers, J. A. (2018). Priming mathematics word problem structures in a rural elementary classroom. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 37(3), 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harcourt Assessment. (2004). Stanford achievement test series: Tenth edition technical data report. Harcourt Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Hobri, H., Susanto, H. A., Hidayati, A., Susanto, S., & Warli, W. (2021). Exploring thinking process of students with mathematics learning disability in solving arithmetic problems. International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science, and Technology (IJEMST), 9(3), 498–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hord, C., & Xin, Y. P. (2013). Intervention research for helping elementary school students with math learning difficulties understand and solve word problems: 1996–2010. Learning Disabilities: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 19(1), 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hord, C., & Xin, Y. P. (2015). Teaching area and volume to students with mild intellectual disability. The Journal of Special Education, 49(2), 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, R. H., Carr, E. G., Halle, J., McGee, G., Odom, S., & Wolery, M. (2005). The use of single-subject research to identify evidence-based practice in special education. Exceptional Children, 71(2), 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, E. M., Witzel, B. S., Riccomini, P. J., Fries, K. M., & Kanyongo, G. Y. (2014). A Meta-Analysis of Algebra Interventions for Learners with Disabilities and Struggling Learners. Journal of the International Association of Special Education, 15(1), 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Jitendra, A. K., Nelson, G., Pulles, S. M., Kiss, A. J., & Houseworth, J. (2016). Is mathematical representation of problems an evidence-based strategy for students with mathematics difficulties? Exceptional Children, 83(1), 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. J., & Xin, Y. P. (2024). A meta-analysis of technology-based word-problem interventions for students with disabilities. Education Sciences, 14(12), 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X., & Xin, Y. P. (2024). Teaching mathematics word problem solving to students with autism spectrum disorder. The Journal of Special Education, 58(1), 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S. P. (1995). Schemas in problem solving. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339, b2535. Available online: https://www.bmj.com/content/339/bmj.b2535.short (accessed on 1 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Montague, M., Enders, C., & Dietz, S. (2011). Effects of cognitive strategy instruction on math problem solving of middle school students with learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 34(4), 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J. A., Witzel, B. S., Powell, S. R., Li, H., Pigott, T. D., Xin, Y. P., & Hughes, E. M. (2022). A meta-analysis of mathematics word-problem solving interventions for elementary students who evidence mathematics difficulties. Review of Educational Research, 92(5), 695–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasamran, A., Witmer, S. E., & Los, J. E. (2017). Exploring predictors of postsecondary outcomes for students with autism spectrum disorder. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 52(4), 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, R. I., Vannest, K. J., Davis, J. L., & Sauber, S. B. (2011). Combining nonoverlap and trend for single-case research: Tau-U. Behavior Therapy, 42(2), 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo-Blanco, I., González-López, M.-J., & Fernández-Cobos, R. (2025). A Follow-Up on the Development of Problem-Solving Strategies in a Student with Autism. Education Sciences, 15, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo-Blanco, I., Van Vaerenbergh, S., Bruno, A., & González, M. J. (2022). Conceptual model-based approach to teaching multiplication and division word-problem solving to a student with autism spectrum disorder. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 57(1), 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polotskaia, E., & Savard, A. (2018). Using the relational paradigm: Effects on pupils’ reasoning in solving additive word problems. Research in Mathematics Education, 20(1), 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, S. R., & Fuchs, L. S. (2018). Effective word-problem instruction: Using schemas to facilitate mathematical reasoning. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 51(1), 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root, J. R., Cox, S. K., & McConomy, M. A. (2022). Teacher-implemented modified schema-based instruction with middle-grade students with autism and intellectual disability. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 47(1), 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root, J. R., Ingelin, B., & Cox, S. K. (2021). Teaching mathematical word problem solving to students with autism spectrum disorder. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 56(4), 420–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root, J. R., Saunders, A., Cox, S. K., Gilley, D., & Clausen, A. (2024). Teaching word problem solving to students with autism and intellectual disability. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 57(1), 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics & National Assessment of Educational Progress. (2024). Mathematica assessment. Available online: https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/reports/mathematics/2024/g4_8/performance-by-student-group/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Van de Walle, J. A., Karp, K. S., & Bay Williams, J. M. (2013). Elementary and middle school mathematics: Teaching developmentally (8th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Verschaffel, L., Schukajlow, S., Star, J., & Van Dooren, W. (2020). Word problems in mathematics education: A survey. ZDM, 52(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Shanahan Bazis, P., & Lei, Q. (2025). Exploring the effects of a problem-posing intervention with students at risk for mathematics and writing difficulties. Education Sciences, 15(6), 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What Works Clearinghouse (WWC). (2022). What Works Clearinghouse procedures and standards handbook (Version 5.0). U.S. Department of Education. Institute of Education Sciences. National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance. Available online: https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/Docs/referenceresources/Final_WWC-HandbookVer5.0-0-508.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Xin, Y. P. (2008). The effect of schema-based instruction in solving word problems: An emphasis on pre-algebraic conceptualization of multiplicative relations. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 39, 526–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y. P. (2012). Conceptual model-based problem solving: Teach students with learning difficulties to solve math problems. Sense. Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-94-6209-104-7 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Xin, Y. P. (2019). The effect of a conceptual model-based approach on ‘additive’ word problem solving of elementary students struggling in mathematics. ZDM, 51(1), 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y. P., & Hord, C. (2013). Conceptual model-based teaching to facilitate geometry learning of students who struggle in mathematics. Journal of Scholastic Inquiry: Education, 1(1), 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, Y. P., Kim, S. J., Lei, Q., Liu, B. Y., Wei, S., Kastberg, S. E., & Chen, Y. V. (2023a). The effect of model-based problem solving on the performance of students who are struggling in mathematics. The Journal of Special Education, 57(3), 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y. P., Kim, S. J., Lei, Q., Wei, S., Liu, B., Wang, W., Kastberg, S., Chen, Y., Yang, X., Ma, X., & Richardson, S. E. (2020a). The effect of computer-assisted conceptual model-based intervention program on mathematics problem-solving performance of at-risk English learners. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 36(2), 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y. P., Kim, S. J., Zhang, J., Lei, Q., Yılmaz Yenioglu, B., Yenioglu, S., & Ma, X. (2023b). Effect of model-based problem solving on error patterns of at-risk students in solving additive word problems. Education Sciences, 13(7), 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y. P., Park, J. Y., Tzur, R., & Si, L. (2020b). The impact of a conceptual model-based mathematics computer tutor on multiplicative reasoning and problem-solving of students with learning disabilities. The Journal of Mathematical Behavior, 58, 100762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y. P., Si, L., Hord, C., Zhang, D., Cetinas, S., & Park, J. Y. (2012). Conceptual model-based problem solving that facilitates algebra readiness: An exploratory study with computer-assisted instruction. Learning Disabilities: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 18(2), 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, Y. P., Tzur, R., Hord, C., Liu, J., Park, J. Y., & Si, L. (2017). An intelligent tutor-assisted mathematics intervention program for students with learning difficulties. Learning Disability Quarterly, 40(1), 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y. P., Wiles, B., & Lin, Y.-Y. (2008). Teaching conceptual model—Based word problem story grammar to enhance mathematics problem solving. The Journal of Special Education, 42(3), 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y. P., & Zhang, D. (2009). Exploring a conceptual model-based approach to teaching situated word problems. The Journal of Educational Research, 102(6), 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y. P., Zhang, D., Park, J. Y., Tom, K., Whipple, A., & Si, L. (2011). A comparison of two mathematics problem-solving strategies: Facilitate algebra-readiness. The Journal of Educational Research, 104(6), 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X., & Xin, Y. P. (2022). Teaching problem posing to students with learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 45(4), 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zentall, S. S. (2013). Students with mild exceptionalities: Characteristics and applications. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D., & Xin, Y. P. (2012). A follow-up meta-analysis for word-problem-solving interventions for students with mathematics difficulties. The Journal of Educational Research, 105(5), 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).