Teaching Written Argumentation to High School Students Using Peer Feedback Methods—Case Studies on the Effectiveness of Digital Learning Units in Teacher Professionalization

Abstract

1. Teaching Didactic Skills to Promote Students’ Argumentation Competences in the Context of Higher Education Teaching

2. Teaching Argumentation with Peer Feedback

2.1. Argumentation as Part of the Language Aware (Geography) Education

2.2. Argumentation Theory Used for the Competency Model for Evaluating Student Teachers’ Performance on Lesson Planning for Promoting Argumentation Competence with Peer Feedback

2.3. Argumentation in Geography Education

2.4. Benefits of Peer Feedback

3. Methods: Using Peer Feedback to Teach Argumentation in High Schools: Developing an OER Unit and a Competency Model for Student Teachers Training in Geography

- On the basis of the experiences of university didactics and the teaching experiences at the schools, the researchers created a course unit to professionalize students of the teaching profession in the area of argumentation competences in political geography, among other things. The students should learn the method peer feedback so that they can use this method later with their students in order to use argumentation competence with their later students.

- Parallel to the creation of the learning unit, a competency model was developed in the process to operationalize which competencies students need to successfully use from the peer feedback method in the classroom to promote argumentation competencies.

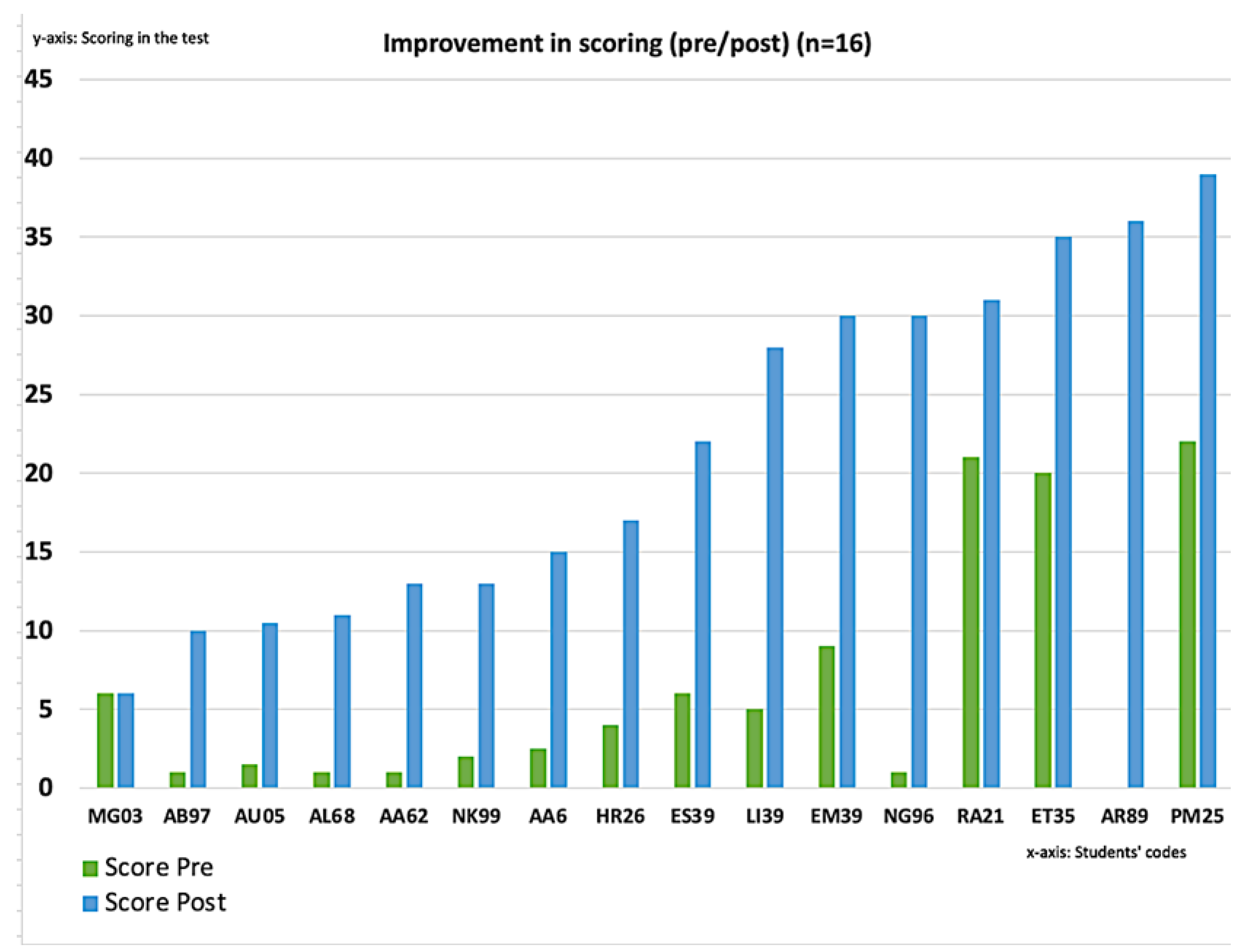

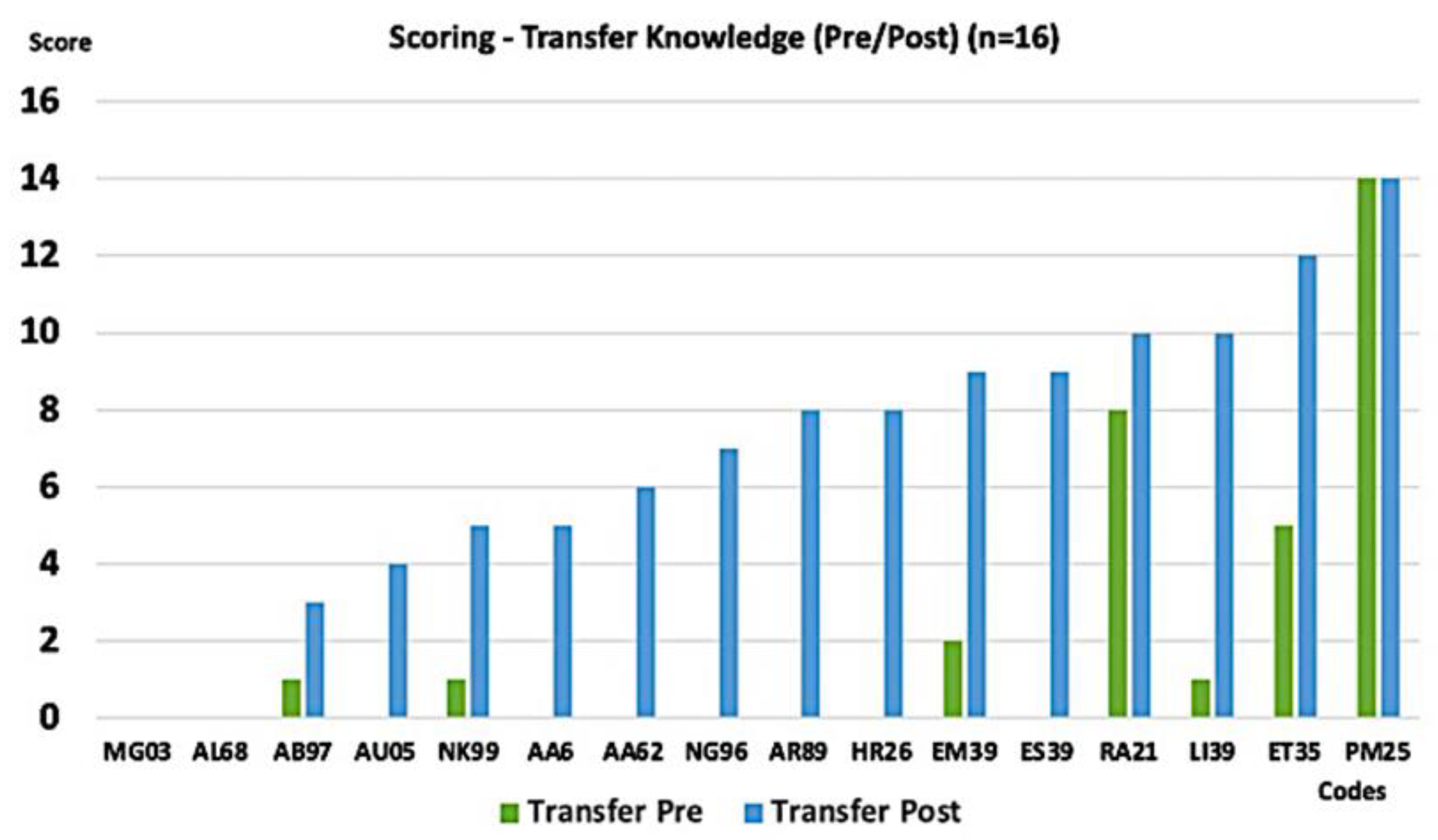

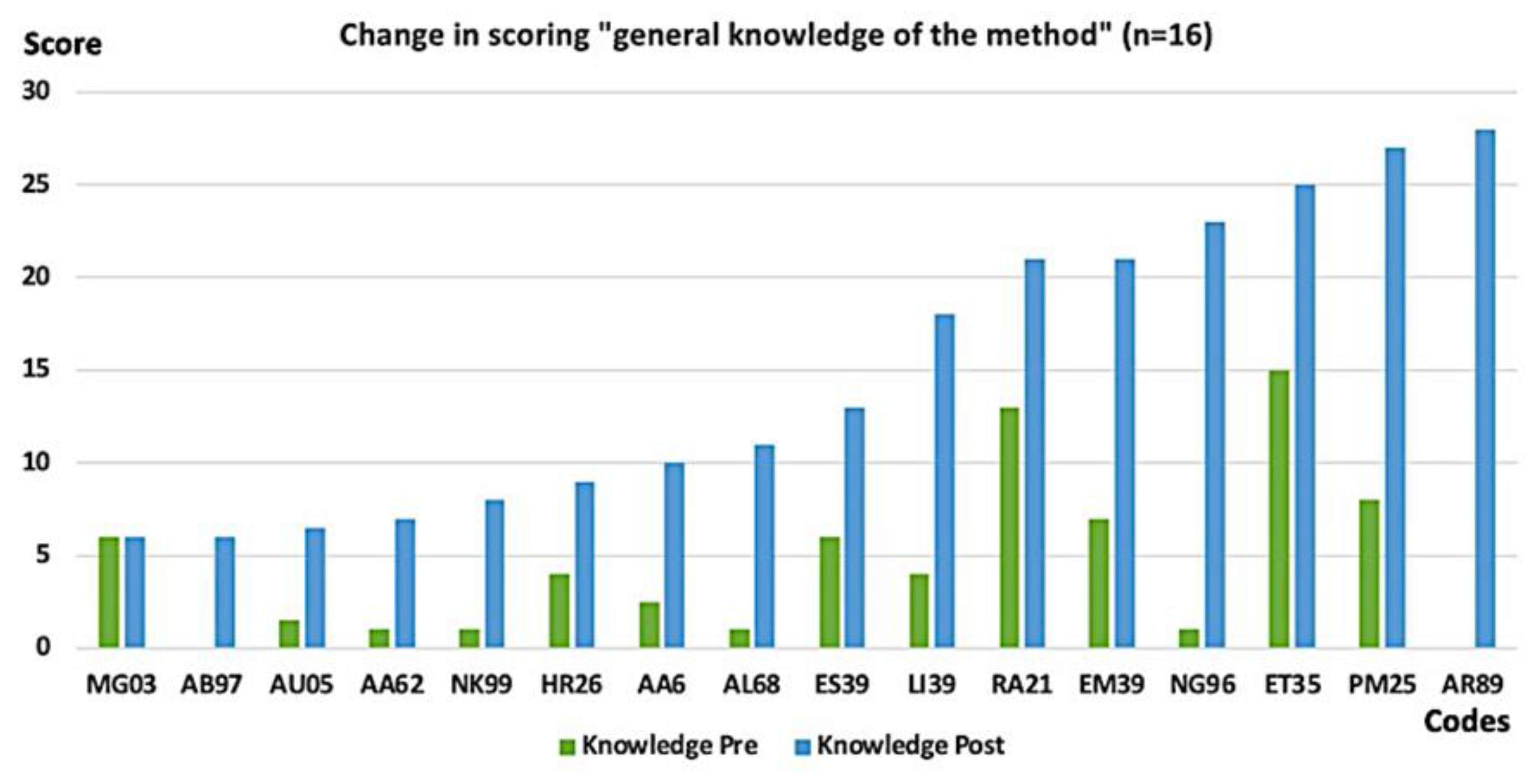

- A pre- and post-test was created to measure learning gains and changes in students’ self-assessment and self-reflection related to their use and engagement with the OER unit. This measured exactly these aspects through open and scaled questions and answer schemes. This will be explained in more detail later.

- The answers were analyzed quantitatively if nominally scaled or ordinally scaled. The open-ended questions were evaluated by using a content-summarizing content analysis according to [71,72]. For this purpose, different raters related the students’ answers to the competency model. Through operationalized scoring in the model, the students were able to be assigned points as an evaluation by consciously assigning statements to the model. This made it possible to give statements about the students’ self-assessment, reflection and formulated skills (statements about methodological didactic content) both before treatment through the OER unit and afterwards. The individual steps are explained in more detail below.

3.1. Development of a Digital Learning Unit (OER) to Support the Didactic Skills of Student Teachers to Promote the Students’ Competences to Argue with Peer Feedback

3.2. Step (Chapters I–II in the Learning Unit): Input: Students Read Empirical Articles on the Importance of Peer Feedback in Promoting Technical Language Requirements (Argumentation) in the Geography Classroom

3.3. Step (Chapter III in the Learning Unit): Get to Know: Students Learn (New) Strategies for Using Peer Feedback to Promote Argumentation Texts in Geography Lessons

3.4. Step (Chapter IV): Students Now Apply the (Acquired) Strategies for the Successful Use of Peer Feedback for Teaching Written Argumentation in One’s Own Teaching Unit Design

3.5. Step (Chapter V in the Learning Unit): Students Reflect on the Learning Gain through This Learning Unit Using Innovative Methods

4. Methods: Data Collection and Analysis

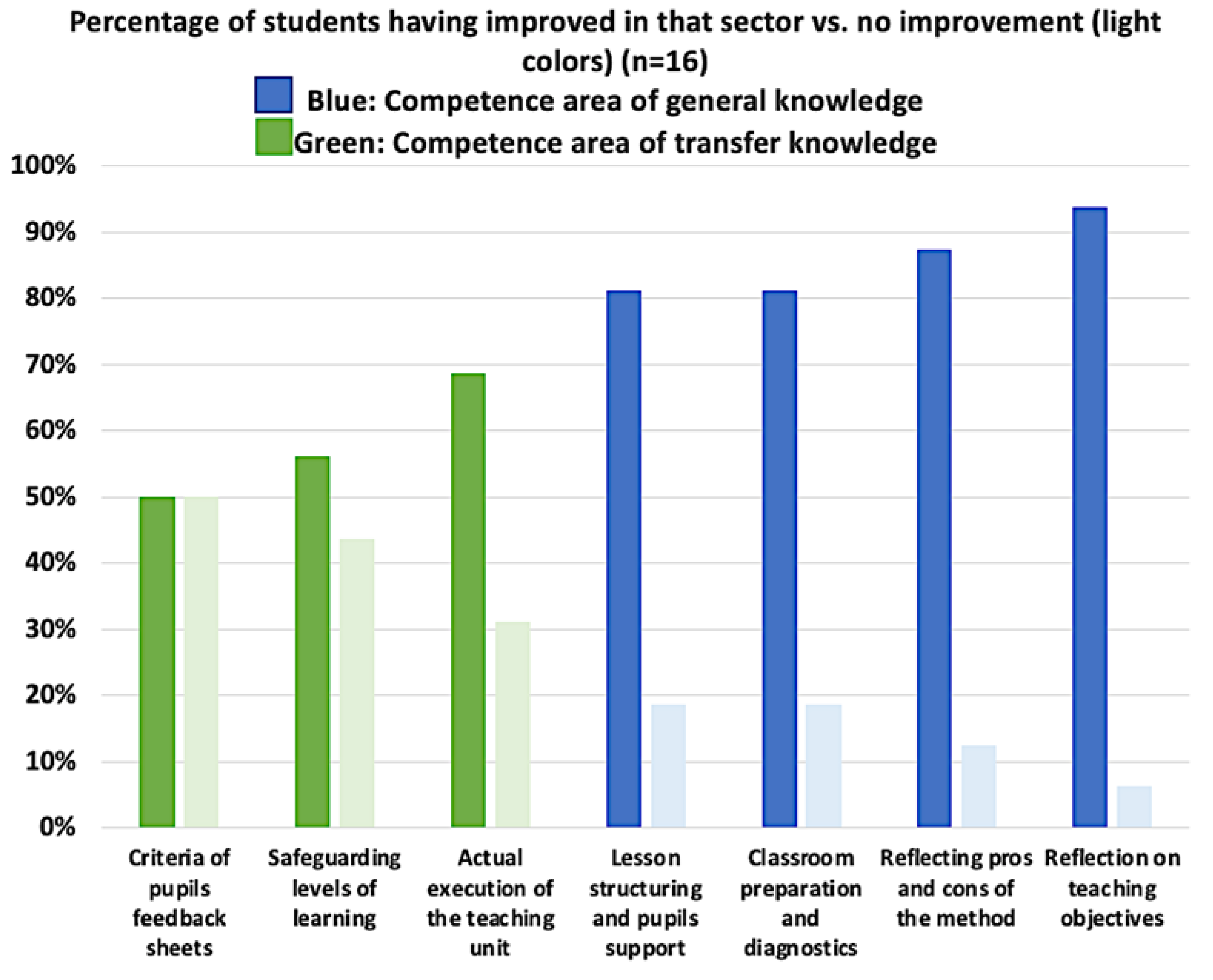

- Subject didactic knowledge about the method: to what extent has knowledge of the learning objectives that can be achieved through the use of peer review increased through the use of OER?

- Concrete preparation and diagnosis: to what extent are students aware of the benefits and uses of the feedback sheet after completing the OER?

- Implementation: to what extent can students meaningfully embed peer feedback into specific lesson planning after working with the OER?

- To what extent did the competency model for evaluating the student teachers’ performance on lesson planning promote argumentation competence with peer feedback?

4.1. Data Collection

4.2. Qualitative Approach of Evaluating Students’ Answers in the (Pre- and Post-) Test

Pretest: RA21: “The method can be time-consuming, depending on the length of the text, and should therefore be used with caution. One-sided feedback can also block the method. When dividing the students into groups/partners independently, it can/will happen that they are divided according to sympathy, which can significantly limit the method.”

Posttest: RA21: “The method is time-consuming, as you not only have to create texts and have them revised several times. Here it is also necessary to be flexible to a possible lack of time. For the teacher there is a high preparation effort. In addition to the information material, a questionnaire should be created, the digital platform must be set up, as well as the expected results. If the performance level or the thought processes of the pairs are too similar, it can come to the fact that no appropriate feedback comes about, so that here on suitable differentiation must be paid attention to. Likewise, attention should be paid to the fact that problems can occur if the criteria of the feedback sheet are not understood. If the materials do not correspond to the level of the students, it can happen that no feedback is given.”

5. Findings

Improvement in Scoring According to the Pre- and Post-Test

HR 26: “Students must first be comfortable with the lesson topic and writing an argumentative text so that they can confidently apply the criteria of the evaluation sheet. I would practice writing and then evaluating the argumentation often beforehand. Sample texts should make it easier to correct.“

AR89: “Give pros and cons, justify comments and make remarks in the text and in the feedback sheet, reduce students’ inhibitions (they should be honest and also criticize), communicate with each other. Students might not take this task of giving feedback seriously enough or they might not dare to criticize. But it could also be that some students do not know how to deal with criticism, especially if it does not come from the teacher, but from someone who has not yet understood the topic. First, students need to be taught the basics before they have time to write the texts. In addition, the criteria of writing should be known.”

AL 68: “Students can improve the following competencies via the method: Word processing skills, factual skills, assessment skills, writing skills. Students will also improve their reasoning skills by having to justify why they can use certain evidence and also write appropriately for the audience.”

AL 68: „Students must be honest and trained in this method”.

ET35: “The students are given another text and have to evaluate it according to the evaluation criteria/sheet. Afterwards, there is an exchange between the students to talk about it, if something was unclear, etc. The students are asked to evaluate the text. In plenary, common mistakes, ambiguities, etc. are discussed and improvements are noted. Students should also know the pros and cons of the method, be able to justify comments and make annotations in the text and feedback sheet. Inhibitions of the students should be reduced (they should be honest and also criticize) and communicate with each other and also allow questions. Feedback should be appreciative.”

6. Limitations, Discussion and Implications

7. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berland, L.; Reiser, B. Classroom communities’ adaptations of the practice of scientific argumentation. Sci. Educ. 2010, 95, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasly, S.D.; Roschelle, J. Constructing a Joint Problem Space: The Computer as a Tool for Sharing Knowledge. In Computers as Cognitive Tools; Lajoie, S.P., Derry, S.J., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1993; pp. 229–258. [Google Scholar]

- Berggren, J. Learning from giving feedback: A study of secondary-level students. ELT J. 2015, 69, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundstrom, K.; Baker, W. To give is better than to receive: The benefits of peer review to the reviewer’s own writing. J. Second. Lang. Writ. 2009, 18, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawski, M.; Budke, A. How Digital and Oral Peer Feedback Improves High School Students’ Written Argumentation-A Case Study Exploring the Effectiveness of Peer Feedback in Geography. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budke, A.; Weiss, G. Sprachsensibler Geographieunterricht. In Sprache als Lernmedium im Fachunterricht. Theorien und Modelle für das Sprachbewusste Lehren und Lernen. Language as Learning Medium in the Subjects; Michalak, M., Ed.; Schneider Hohengehren: Baltmannsweiler, Germany, 2014; pp. 113–133. [Google Scholar]

- Budke, A.; Kuckuck, M.; Morawski, M. Sprachbewusste Kartenarbeit? Beobachtungen zum Karteneinsatz im Geographieunterricht. GW-Unterricht 2017, 48, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawski, M.; Budke, A. Förderung von Argumentationskompetenzen Durch das “Peer-Review-Verfahren”. In Argumentieren im Sprachunterricht. Beiträge zur Fremdsprachenvermittlung; Abdel-Hafiez, M., Ed.; VEP: Landau, Germany, 2018; pp. 75–101. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, K.L.; Entwisle, D.R.; Olson, L.S. Schools, Achievement, and Inequality: A Seasonal Perspective. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 2001, 23, 71–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditton, H. Qualitätssicherung in Schulen. In Qualitätssicherung im Bildungssystem—Eine Bilanz. (Beiheft der Zeitschrift für Pädagogik); Klieme, E., Tippelt, R., Eds.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2008; pp. 36–58. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Inquiry and the National Science Education Standards; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; Available online: http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?isbn=0309064767 (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Geographie (DGfG). Bildungsstandards im Fach Geographie für den Mittleren Schulabschluss–mit Aufgabenbeispielen [Educational Standards in the Subject Geography for the Secondary School]. Bonn. 2014. Available online: http://dgfg.geography-in-germany.de/wp-content/uploads/geographie_bildungsstandards.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- European Union Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 December. Key Competences for Lifelong Learning. 2006. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2006:394:0010:0018:en:PDF (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Weinstock, M.P. Psychological research and the epistemological approach to argumentation. Informal Log. 2006, 26, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstock, M.P.; Neuman, Y.; Glassner, A. Identification of informal reasoning fallacies as a function of epistemological level, grade level, and cognitive ability. J. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 98, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogen, A. Didaktische Rekonstruktion des Themas Illegale Migration Argumentationsanalytische Untersuchung von Schüler*Innenvorstellungen im Fach Geographie. Didactical Reconstruction of the Topic “Illegal Migration“. Analysis of Argumentation among Pupils‘ Concepts. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Münster, Münster, Germany, 2016. Available online: https://www.uni-muenster.de/imperia/md/content/geographiedidaktische-forschungen/pdfdok/band_59.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Means, M.L.; Voss, J.F. Who reasons well? Two studies of informal reasoning among children of different grade, ability and knowledge levels. Cogn. Instr. 1996, 14, 139–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reznitskaya, A.; Anderson, R.; McNurlen, B.; Nguyen-Jahiel, K.; Archoudidou, A.; Kim, S. Influence of oral discussion on written argument. Discourse Process. 2001, 32, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, D. Education for Thinking; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Leitao, S. The potential of argument in knowledge building. Hum. Dev. 2000, 43, 332–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, E.M.; Sinatra, G.M. Argument and conceptual engagement. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 28, 573–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckuck, M. Konflikte im Raum—Verständnis von Gesellschaftlichen Diskursen Durch Argumentation im Geographieunterricht [Spatial Conflicts—How Pupils Understand Social Discourses through Argumentation]. In Geographiedidaktische Forschungen; Monsenstein und Vannerdat: Münster, Germany, 2014; Volume 54. [Google Scholar]

- Dittrich, S. Argumentieren als Methode zur Problemlösung Eine Unterrichtsstudie zur Mündlichen Argumentation-on von Schülerinnen und Schülern in Kooperativen Settings im Geographieunterricht. Solving Problems with Argumentation in the Geography Classroom. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Münster, Münster, Germany, 2017. Available online: https://www.uni-muenster.de/imperia/md/content/geographiedidaktische-forschungen/pdfdok/gdf_65_dittrich.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Müller, B. Komplexe Mensch-Umwelt-Systeme im Geographieunterricht mit Hilfe von Argumentationen er-schließen. Analyzing Complex Human-Environment Systems in Geography Education with Argumentation. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany, 2016. Available online: https://kups.ub.uni-koeln.de/7047/4/Komplexe_Systeme_Geographieunterricht_Beatrice_Mueller.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Leder, J.S. Pedagogic Practice and the Transformative Potential of Education for Sustainable Development. Argumentation on Water Conflicts in Geography Teaching in Pune. India. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany, 2016. Available online: http://kups.ub.uni-koeln.de/7657/ (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Budke, A.; Meyer, M. Fachlich Argumentieren Lernen—Die Bedeutung der Argumentation in den Unter-Schiedlichen Schulfächern. In Fachlich Argumentieren Lernen. Didaktische Forschungen zur Argumentation in den Unterrichtsfächern; Budke, A., Kuckuck, M., Meyer, M., Schäbitz, F., Schlüter, K., Weiss, G., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2015; pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Budke, A.; Creyaufmüller, A.; Kuckuck, M.; Meyer, M.; Schlüter, K.; Weiss, G. Argumentationsrezeptions-Kompetenzen im Vergleich der Fächer Geographie, Biologie und Mathematik. In Fachlich Argumentieren Lernen. Didaktische Forschungen zur Argumentation in den Unterrichtsfächern; Budke, A., Kuckuck, M., Meyer, M., Schäbitz, F., Schlüter, K., Weiss, G., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2015; pp. 273–297. [Google Scholar]

- Toulmin, S. The Use of Arguments; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Rapanta, C.; Garcia-Mila, M.; Gilabert, S. What Is Meant by Argumentative Competence? An Integrative Review of Methods of Analysis and Assessment in Education. Rev. Educ. Res. 2013, 83, 438–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budke, A. Förderung von Argumentationskompetenzen in Aktuellen Geographieschulbüchern. In Aufgaben im Schulbuch; Matthes, E., Heinze, C., Eds.; Verlag Julius Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2011; pp. 253–263. [Google Scholar]

- Kopperschmidt, J. Argumentationstheorie. Theory of Argumentation; Junius: Hamburg, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, D.N. The New Dialectic: Conversational Contexts of Argument; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, Canada, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perelman, C. The Realm of Rhetoric; University of Notre Dame Press: Notre Dame, IN, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Erduran, S.; Jiménez-Aleixandre, M.P. Argumentation in Science Education: Perspectives from Classroom-Based Research; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Mila, M.; Gilabert, S.; Erduran, S.; Felton, M. The effect of argumentative task goal on the quality of argumentative discourse. Sci. Educ. 2013, 97, 497–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, K.L. Teachers’ use of curriculum to support students in writing scientific arguments to explain phenomena. Sci. Educ. 2008, 93, 233–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felton, M.; Kuhn, D. The development of argumentative discourse skills. Discourse Process. 2001, 32, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, D. The Skills of Argument; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, D.; Shaw, V.; Felton, M. Effects of dyadic interaction on argumentative reasoning. Cogn. Instr. 1997, 15, 287–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billig, M. Arguing and Thinking: A Rhetorical Approach to Social Psychology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann, T.; Becker-Mrotzek, M. Schreibaufgaben Situieren und Profilieren. To Profile Writing Tasks. In Textformen als Lernformen. Text Forms als Learning Forms; Pohl, T., Steinhoff, T., Eds.; Gilles & Francke: Duisburg, Germany, 2010; pp. 191–210. [Google Scholar]

- Feilke. Schreibdidaktische Konzepte. In Forschungshandbuch Empirische Schreibdidaktik. Handbook on Empirical Teaching Writing Research; Becker-Mrotzek, M., Grabowski, J., Steinhoff, T., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2017; pp. 153–173. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, J.; Flower, L. Identifying the Organization of Writing Processes. In Cognitive Processes in Writing; Gregg, L., Steinberg, E., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1980; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, V.; Venville, G. High-school students’ informal reasoning and argumentation about biotechnology: An indicator of scientific literacy? Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2009, 31, 1421–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kienpointner, M. Argumentationsanalyse. Analysis of Argumentation. In Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Kulturwissenschaft; Institut für Sprachwissenschaften der Universität Innsbruck: Innsbruck, Austria, 1983; Volume 56. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, D. A developmental model of critical thinking. Educ. Res. 1999, 28, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, D. Metacognitive development. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2000, 9, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, D. Teaching and learning science as argument. Sci. Educ. 2010, 94, 810–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohar, A.; Nemet, F. Fostering students’ knowledge and argumentation skills through dilemmas in human genetics. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2002, 39, 35–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidler, D.; Sadler, T.; Applebaum, S.; Callahan, B. Advancing reflective judgment through socioscientific issues. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2009, 46, 74–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, T.D.; Donnelly, L.A. Socioscientific argumentation: The effects of content knowledge and morality. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2006, 28, 1463–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, K. Children’s understanding of scientific inquiry: Their conceptualization of uncertainty in investigations of their own design. Cogn. Instr. 2004, 22, 219–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, W.A.; Millwood, K. The quality of students’ use of evidence in written scientific explanations. Cogn. Instr. 2005, 23, 23–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evagorou, M.; Osborne, J. Exploring Young Students’ Collaborative Argumentation Within a Socioscientific Issue. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2013, 50, 209–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evagorou, M. Discussing a Socioscientific Issue in a Primary School Classroom: The Case of Using a Technology-Supported Environment in Formal and Nonformal Settings. In Socioscientific Issues in the Classroom; Sadler, T., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 133–160. [Google Scholar]

- Evagorou, M.; Jime´nez-Aleixandre, M.; Osborne, J. ‘Should We Kill the Grey Squirrels? ‘A Study Exploring Students’ Justifications and Decision-Making. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2012, 34, 401–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.; Akerson, V.; Oldfield, M. Environmental argumentation as sociocultural activity. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2012, 49, 869–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehnen, K. Kooperatives Schreiben. In Handbook on Empirical Teaching Writing Research; Becker-Mrotzek, M., Grabowski, J., Steinhoff, T., Eds.; Handbuch empirische Schreibdidaktik; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2017; pp. 299–315. [Google Scholar]

- Berland, L.K.; Hammer, D. Framing for scientific argumentation. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2012, 49, 68–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, D.; Hood, P.; Marsh, D. CLIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawski, M.; Budke, A. Learning With and By Language: Bilingual Teaching Strategies for the Monolingual Language-Aware Geography Classroom. Geogr. Teach. 2017, 14, 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breidbach, S.; Viebrock, B. CLIL in Germany—Results from Recent Research in a Contested Field. Int. CLIL Res. J. 2012, 1, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, G.; Simpson, C. Conditions under which Assessment supports Student Learning. Learn. Teach. High. Educ. 2004, 1, 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Diab, N.W. Effects of peer-versus self-editing on students’ revision of language errors in revised drafts. System 2010, 38, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H. Investigating learners’ use and understanding of peer and teacher feedback on writing: A comparative study in a Chinese English writing classroom. Assess. Writ. 2010, 1, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S´eror, J. Alternative sources of feedback and second language writing development in university content courses. Can. J. Appl. Linguist. 2011, 14, 118–143. [Google Scholar]

- Kelle, U. Mixed Methods. In Handbuch Methoden der Empirischen Sozialforschung; Baur, N., Blasius, J., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Qualitative Analysis of Content, 12th ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analyis in Practice; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA; London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Herzmann, P.; König, J. Lehrerberuf und Lehrerbildung; Verlag Julius Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrungg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terhart, E. Lehrerberuf und Professionalität. Gewandeltes Begriffsverständnis—Neue Herausforderungen. In Pädagogische Professionalität; Helsper, W., Tippelt, R., Eds.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2011; pp. 202–224. [Google Scholar]

- Leinhardt, G.; Greeno, J. The cognitive skill of teaching. J. Educ. Psychol. 1986, 78, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromme, R.; Rheinberg, F.; Minsel, B.; Weidemann, B. Die Erziehenden und Lehrenden. In Pädagogische Psychologie; Krapp, A., Weidemann, B., Eds.; Ein Lehrbuch: Weinheim, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bromme, R. Teacher Expertise. In International Encyclopedia of the Behavioral Sciences: Education; Smelser, N.J., Baltes, P.B., Weinert, F.E., Eds.; Pergamon: London, UK, 2001; pp. 15459–15465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmke, A. Unterricht Erfassen, Bewerten, Verbessern; Kaalmeyer: Seelze, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwoudt, J.E. Investigating synchronous and asynchronous class attendance as predictors of academic success in online education. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 36, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offir, B.; Lev, Y.; Bezalel, R. Surface and deep learning processes in distance education: Synchronous versus asynchronous systems. Comput. Educ. 2008, 51, 1172–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawski, M.; Budke, A. Language Awareness in Geography Education—An Analysis of the Potential of Bilingual Geography Education for Teaching Geography to Language Learners. Eur. J. Geogr. 2017, 7, 61–84. [Google Scholar]

- Fögele, J. Entwicklung Basiskonzeptionellen Verständnisses in Geographischen Lehrerfortbildungen. Rekonstruktive Typenbildung|Relationale Prozessanalyse|Responsive Evaluation. 2016. Available online: https://www.uni-muenster.de/imperia/md/content/geographiedidaktische-forschungen/pdfdok/gdf_61_f__gele.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Klieme, E.; Avenarius, H.; Blum, W.; Döbrich, P.; Gruber, H.; Prenzel, M.; Reiss, K.; Riquarts, K.; Rost, J.; Tenorth, H.-E.; et al. (Eds.) Zur Entwicklung Nationaler Bildungsstandards; Eine Expertise; BMBF: Bonn, Germany, 2003.

- Lord, F.M. Applications of Item Response Theory to Practical Testing Problems; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Rasch, G. Probabilistic Models for Some Intelligence and Attainment Tests; MESA: Chicago, IL, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- van Holt, N.; Manitius, V. Transfer Zwischen Lehrer(fort)bildung und Wissenschaft. Reihe: Beiträge zur Schulentwicklung; WBV: Bielefeld, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vigerske, S. Transfer von Lehrerfortbildungsinhalten in die Praxis. Eine empirische Untersuchung zur Transferqualität und zu Einflussfaktoren; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyer, B. Quasi-Experimental Research Designs; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement and Evaluation; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; Volume 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, C.; Babbie, S. Research Methods for Social Work, 9th ed.; Cengage: Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Arndt, C.; Ladwig, T.; Knutzen, S. Zwischen Neugier und Verunsicherung: Interne Hochschulbefragungen von Studierenden und Lehrenden im virtuellen Sommersemester 2020: Ergebnisse einer qualitativen Inhaltsanalyse. Tech. Univ. Hambg. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, S.; Rödel, B. Open Educational Resources (OER) an Berufsbildenden Schulen in Deutschland Ergebnisse Einer Bundesweiten Onlineumfrage; Wissenschaftliche Diskussionspapiere: Heft, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Beutner, M.; Schneider, J.N. Open Educational Resources in der aktuellen Bildungslandschaft: Motivation zur Teilung und Nutzung. Kölner Zeitschrift für Wirtschaft und Pädagogik 2015, 58, 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Hannafin, M.J. Design- Based Research and Technology-Enhanced Learning Environments. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2005, 53, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, E. Technology enhanced learning in science: Interactions, affordances and design-based research. J. Interact. Media Educ. 2010, 2010, Art. 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, F. The Basics of Item Response Theory; Tech. Univ. Hambg.; ERIC Clearinghouse on Assessment and Evaluation, University of Maryland: College Park, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

| Knowledge Type | Areas of Knowledge (Competency Area) | Exemplary Expectation Horizon: Student Teachers Know about the Following Potentials, Pros and Cons of the Method Peer Feedback |

|---|---|---|

| I General didactic knowledge about the use of the method | 1. Determination of learning objectives by the student teachers for pupils in the geography classroom using peer feedback |

|

| 2. Knowledge about the feedback sheet for implementation of the method peer feedback | Student teachers know (that):

| |

| II Practical transfer knowledge (Implementation of the method) | 3. Planning: Preparation and Diagnosis 4. Planning: Implementation & Transfer | Student teachers can:

|

| Questions in the Test | According to Competency Area (Competency Model; See Table 1) |

|---|---|

| Which learning objectives would you formulate in a didactic commentary on a teaching unit with peer feedback and which areas of competence/skills can be promoted in the pupils with this method? | 1. Determination of learning objectives by the student teachers for pupils in the geography classroom using peer feedback |

| What advantages and disadvantages do you see in the peer feedback method? | 1. Determination of learning objectives by the student teachers for pupils in the geography classroom using peer feedback |

| For which grade/age group do you think the feedback sheet and method presented in the unit is suitable? | 3. Planning: Preparation and Diagnosis |

| When in the course of a teaching sequence/series would you use the peer feedback method? | 3. Planning: Preparation and Diagnosis |

| What factors do you think play a central role in successful peer feedback among pupils? What do students need to consider for successful feedback? What needs to be taught to pupils in order for them to give feedback successfully? | 3. Planning: Preparation and Diagnosis 4. Planning: Implementation/Transfer |

| What concrete practical preparations do you need to make in planning before using the peer feedback method in the classroom? | 3. Planning: Preparation and Diagnosis 4. Planning: Implementation/Transfer |

| What steps should you follow to introduce/explain the peer feedback method in the classroom? | 3. Planning: Preparation and Diagnosis 4. Planning: Implementation/Transfer |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morawski, M.; Budke, A. Teaching Written Argumentation to High School Students Using Peer Feedback Methods—Case Studies on the Effectiveness of Digital Learning Units in Teacher Professionalization. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13030268

Morawski M, Budke A. Teaching Written Argumentation to High School Students Using Peer Feedback Methods—Case Studies on the Effectiveness of Digital Learning Units in Teacher Professionalization. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(3):268. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13030268

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorawski, Michael, and Alexandra Budke. 2023. "Teaching Written Argumentation to High School Students Using Peer Feedback Methods—Case Studies on the Effectiveness of Digital Learning Units in Teacher Professionalization" Education Sciences 13, no. 3: 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13030268

APA StyleMorawski, M., & Budke, A. (2023). Teaching Written Argumentation to High School Students Using Peer Feedback Methods—Case Studies on the Effectiveness of Digital Learning Units in Teacher Professionalization. Education Sciences, 13(3), 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13030268