A Review of Global Challenges and Survival Strategies of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Importance of SMEs in Economic Development

3. Theoretical Approaches—Explaining the Impact of Global Challenge and Survival Strategies

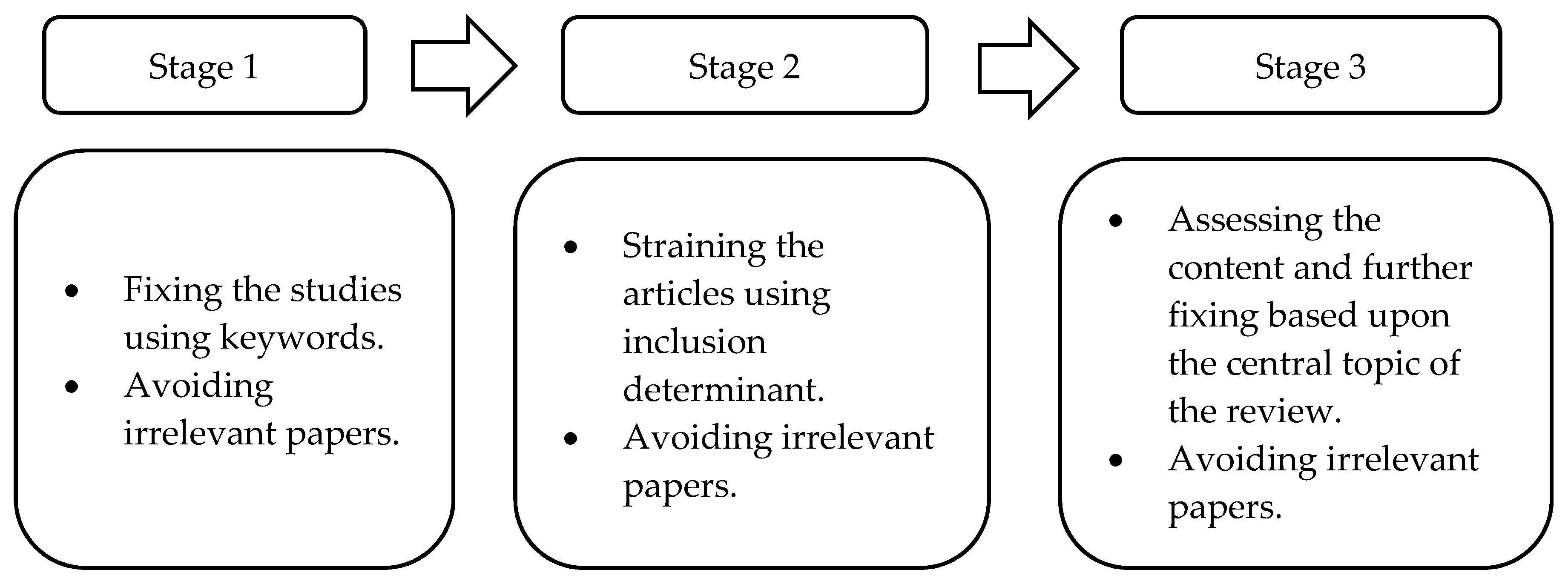

4. Methodology

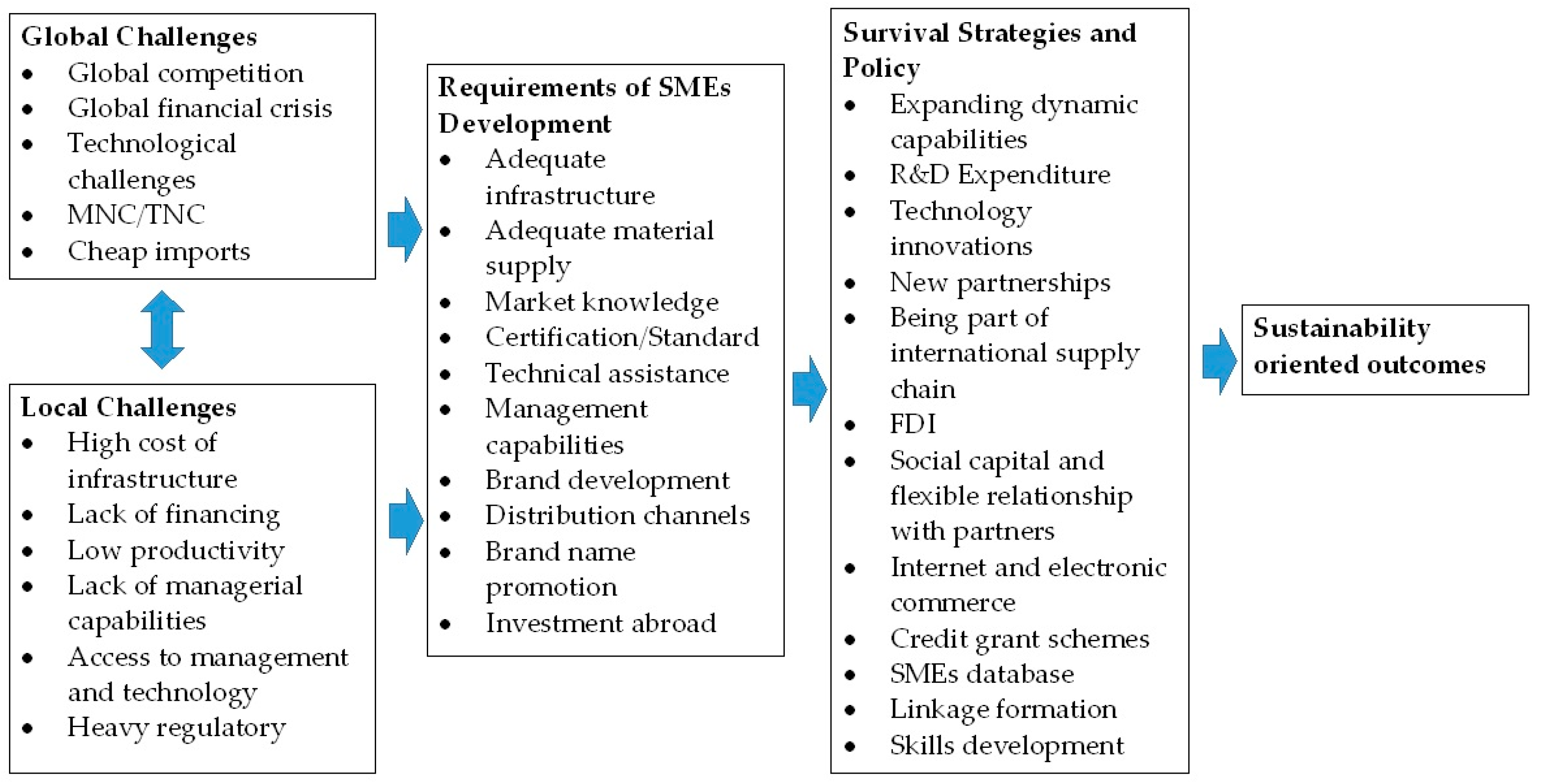

5. Global Challenges of SMEs

5.1. The Challenge of Global Economic Competition

5.2. The Challenge of Global Capital and Economic Crisis

5.3. The Challenge of Information Communication Technology

5.4. The Challenge of Multi-National Corporations

5.5. The Challenge of Trans-National Corporations (TNCs)

5.6. International Terrorism and Religious Conflicts

5.7. International Trade War

5.8. International Dumping

6. The Survival Strategies of SMEs Confronting Global Challenges

7. Concluding Remarks and Dimensions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmedova, Sibel. 2015. Factors for Increasing the Competitiveness of Small and Medium-Sizes Enterprises (SMEs) in Bulgaria. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 195: 1104–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainuddin, R. Azimah, Pawl W. Beamish, John S. Hulland, and Michael J. Rouse. 2007. Resource attributes and firm performance in international joint ventures. Journal of World Business 42: 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alauddin, Md, and Mustafa Manir Chowdhury. 2015. Small and Medium Enterprise in Bangladesh-Prospects and Challenges. Global Journal of Management and Business Research: C Finance 15: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Aldaba, Rafaelita M., and Fernando T. Aldaba. 2010. Assessing the Spillover Effects of FDI to the Philippines. Discussion Paper Series No. 2010-27; Makati: Pjilippine Institute for Development Studies, pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Alfred, M. Pelham, and David T. Wilson. 1996. A Longitudinal Study of the Impact of Market Structure, Firm Structure, Strategy, and Market Orientation Culture on the Dimension of Small-Firm Performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 24: 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andalib, Tarnima Warda, and Mohd Ridzuan Darun. 2018. An HRM model for manufacturing companies of Bangladesh mapping employee rights’ protocols and grievance management system. Indian Journal of Science and Technology 11: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, Karolina, and Carin Thuresson. 2008. The Impact of an Anti-Dumping Measure—A Study of an Anti-Dumping Measure. Bachelor’s thesis, Jonkoping International Business School, Jonkoping, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- APEC. 2010. Removing Barriers to SME Access to International Markets. Hong Kong: Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation. [Google Scholar]

- Asare, Roland, Mavis Akuffobea, Wilhelmina Quaye, and Kwasi Atta-Antwi. 2015. Characteristics of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises in Ghana: Gender and Implications for Economic Growth. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development 7: 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgary, Ali, Ali Ihsan Ozdemir, and Hale Ozyurek. 2020. Small and Medium Enterprises and Global Risks: Evidence from Manufacturing SMEs in Turkey. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 11: 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspers, Patrik, and Sebastian Kohl. 2015. Economic Theories of Globalization. In The Routledge International Handbook of Globalization Studies, 1st ed. Edited by Bryan S. Turner and Robert J. Holton. London: Routledge, vol. 1, pp. 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, Murat, Nilgun Anafarta, and Fulya Sarvan. 2013. The Relationship between Innovation and Firm Performance: An Empirical Evidence from the Turkish Automotive Supplier Industry. Procedia Social and Behavioral Science 75: 226–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auzzir, Zairol, Richard Haigh, and Dilanthi Amaratunga. 2018. Impacts of Disaster to SMEs in Malaysia. Proedia Engineering 212: 1131–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyagari, Meghana, Thorsten Beck, and Asli Demirguc-Kunt. 2007. Small and Medium Enterprises across the globe. Small Business Economics 29: 415–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdadi, Leila, Sonia BenKheder, and Hassan Arouri. 2016. Impact of Non-Tariff Measures on SMEs in Tunisia. Tunisia: International Trade Center. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, David Mc. A. 2014. The Effects of Terrorism on the Travel and Tourism Industry. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage 2: 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldacchino, Godfrey. 2005. Successful Small-Scale Manufacturing from Small Islands: Comparing Firms Benefiting from Locally Available Raw Material Input. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 18: 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, Jay. 1991. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management 17: 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belleflamme, Paul, Thomas Lambert, and Armin Schwienbacher. 2014. Crowdfunding: Tapping the right crowd. Journal of Business Venturing 29: 585–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernroider, Edward W. N. 2002. Factors in SWOT Analysis Applied to Micro, Small-to-Medium, and Large Software Enterprises. European Management Journal 20: 562–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, Zaroug Osman, and Nawal Said Al Mqbali. 2015. Challenges and Constraints Faced by Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in AL Batinah Governorate of Oman. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management, and Sustainable Development 11: 120–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomstrom, Magnus, and Ari Kokko. 1998. Multinational corporations and spillovers. Journal of Economic Surveys 12: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burn, Janice, and Emmanuel Tettah. 2001. Global strategies for SME business: Applying the SMALL framework. Logistics Information Management 14: 171–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J., and J. Sullivan. 2005. Crisis Response Tactics: US SMEs’ Responses to the Asian Financial Crisis. Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship 17: 56. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, Ngoc Tuan, and Hepu Deng. 2018. Critical Determinants for Mobile Commerce Adoption in Vietnamese SMEs: A Conceptual Framework. Procedia Computer Science 138: 433–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, Yoke-Tong, and Henry Wai-Chung Yeung. 2001. The SME Advantage: Adding Local Touch to Foreign Transnational Corporations in Singapore. Regional Studies 35: 431–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, Mohammed S., Rabiul Islam, and Zahurul Alam. 2013. Constraints to the development of small and medium-sized enterprises in Bangladesh: An Empirical Investigation. Australian Journal of Business and Applied Sciences 7: 690–96. [Google Scholar]

- CRS. 2019. China’s Economic Rise: History, Trends, Challenges, and Implications for the United States. Washington: Congressional Research Service. [Google Scholar]

- Dess, Gregory G., and Peter S. Davis. 1984. Porter’s generic strategies as determinants of strategic group membership and organizational performance. Academy of Management Journal 27: 467–88. [Google Scholar]

- Doh, Soogwan, and Byungkyu Kim. 2014. Government Support for SME Innovations in the Regional Industries: The Case of Government Financial Support Programme in South Korea. Research Policy 43: 1557–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domac, Ilker, Giovanni Ferri, and Tae Soo Kang. 1999. The Credit Crunch in East Asia: Evidence from Field Findings on Bank Behavior and Policy Issues. World Bank Working Papers. Washington: The World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez, Noemie, and Ulrike Mayrhofer. 2017. Internationalization stages of traditional SMEs: Increasing, decreasing and re-increasing commitment to foreign markets. International Business Review 26: 1051–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eniola, Anthony Abiodun, and Harry Entebang. 2015. Small Firm Performance-Financial Innovation and Challenges. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 195: 334–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eravia, Diana, Tri Handayani, and Julina. 2015. The Opportunities and Threats of Small and Medium Enterprises in Pekanbaru: Comparison between SMEs in Food and Restaurant Industries. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 169: 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Erixon, Fredrik. 2018. The Economic Benefits of Globalization for Business and Consumers. Brussels: European Center for International Political Economy. [Google Scholar]

- Eze, Titus Chinweuba, and Cyril Sunday Okpala. 2015. Quantitative Analysis of the Impact of Small and Medium Scale Enterprises on the Growth of Nigerian Economy: (1993–2011). International Journal of Development and Emerging Economics 3: 26–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fiseha, Gebregizabher Gebreyesus, and Akeem Adewale Oyelana. 2015. An Assessment of the Roles of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in the Local Economic Development (LED) in South Africa. Journal of Economics 6: 280–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, Luis, and Filipe Carvalho. 2019. The Reporting of SDGs by Quality, Environmental, and Occupational Health and Safety-Certified Organizations. Sustainability 11: 5797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, Luis, Amilcar Ramos, Alvaro Rosa, Ana Cristina Braga, and Paulo Sampaio. 2016. Stakeholders Satisfaction and Sustainable Success. International Journal of Industrial and Systems Engineering 24: 144–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaibulloev, Khusrav, and Todd Sandler. 2008. The Impact of Terrorism and Conflicts on Growth in Asia, 1970–2004—ADB Institute Discussion Paper No. 113. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Gamage, Sisira Kumara Naradda, E.M.S. Ekanayake, G.A.K.N.J. Abeyrathne, R.P.I.R. Prasanna, J.M.S.B. Jayasundara, and P.S.K. Rajapakshe. 2019. Global Challenges and Survival Strategies of the SMEs in the Era of Economic Globalization: A Systematic Review. Mihintale: Rajarata University of Sri Lanka. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, Guadalupe Manzano, Juan Carlos, and Ayala Calvo. 2020. Entrepreneurial Orientation: It’s Relationship with the Entrepreneur’s Subjective Success in SMEs. Sustainability 12: 4547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GEM. 2014. Spain Report. London: Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. [Google Scholar]

- Gherghina, Stefan Cristian, Mihai Alexandru Botezatu, Alexandra Hosszu, and Liliana Nicoleta Simionescu. 2019. Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs): The Engine of Economic Growth through Investment and Innovation. Sustainability 12: 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregar, Ales, Ladislav Kudlacek, Sisira Kumara Naradda Gamage, and Hewa Ravindra Kuruppuge. 2018. Employment Choice of Non-family Professionals in Family Firms. International Scientific Day 2018: 1168–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunday, Gurhan, Gunduz Ulusoy, kemal Kilic, and Lutfihak Alpkan. 2011. Effects of Innovation Types on Firm Performance. International Journal of Production Economics 133: 662–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, Hui-Lin. 2011. Assessing the SMEs Competitive Strategies on the Impact of Environmental Factors: A Quantitative SWOT Analysis Application. In Environmental Management in Practice. Rijeka: IntechOpen. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helen, Barry, and Brigid Milner. 2002. SMEs and electronic commerce: A departure from the traditional prioritization of training? Journal of European Industrial Training 26: 316–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessels, Jolanda, and Simon C. Parker. 2013. Constraints, internationalization and growth: A cross-country analysis of European SMEs. Journal of World Business 48: 137–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinson, Robert, and Olav Jull Sorensen. 2006. E-business and small Ghanaian exporters: Preliminary micro firm explorations in the light of the digital divide. Online Information Review 30: 116–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Tuan, Trang Thi Ngoc Nguyen, and Tho Ngoc Tran. 2018. How will Vietnam Cope with the Impact of the US-China Trade War? Ho Chi Minh City: Yusof Ishak Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Hogeforster, Max. 2014. Future Challenges for Innovations in SME in the Baltic Sea Region. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 110: 241–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, Abu Shams Mohammad Mahmadul. 2018. The effect of entrepreneurial orientation on Bangladeshi SME performance: Role of organizational culture. International Journal of Data and Network Science 2: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, Abu Shams Mohammad Mohamudul, and Zainudin Bin Awang. 2016. The Sway of Entrepreneurial Marketing on Firm Performance: Case of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Bangladesh. Paper presented at the Terengganu International Business and Economics Conference (TiBEC-V), Universiti Teknologi Mara (UiTM), Terengganu, Malaysia, September 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hoque, Abu Shams Mohammad Mahmudul, Uzairu Muhammad Gwadabe, and Atiqur Rahman. 2017. Corporate Entrepreneurship Upshot on Innovation Performance: The Mediation of Employee Engagement. Journal of Humanities, Language, Culture and Business 1: 54–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hoque, Abu Shams Mohammad Mohamudul, Zainudin Bin Awang, Habsah Muda, and Fauzilah Salleh. 2018. Ramification of crowd funding on Bangladeshi Entrepreneur’s Self-Efficiency. Accounting 4: 129–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houben, G., K. Lenie, and K. Vanhoof. 1999. A knowledge based SWOT-analysis system as an instrument for strategic planning in small- and medium-sized enterprises. European Management Journal 20: 562–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, Najafi Auwalu, and Abdulsalam Masud. 2016. Moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation on the relationship between entrepreneurial skills, environmental factors and entrepreneurial intention: A PLS approach. Management Science Letters 6: 225–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEP. 2016. Global Terrorism Index 2016—Measuring and Understanding the Impact of Terrorism. New York: Institute for Economics and Peace. [Google Scholar]

- Ifekwem, Nkiruka, and Ogundeinde Adedamola. 2016. Survival Strategies and Sustainability of Small and Medium Enterprises in the Oshodi-Isolo Local Government Area of Lagos State. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Economics and Business 4: 103–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhonopi, David, and Ugochukwu Moses Urim. 2016. The Spectre of Terrorism and Nigeria’s Industrial Development: A Multi-Stakeholder Imperative. African Journal of Criminology and Justice Studies 9: 20–41. [Google Scholar]

- ISDP. 2020. Snapshot of the U.S.-China Trade War. Washington: Institute for Security and Development Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Jeppesen, Soeren. 2005. Enhancing Competitiveness and Securing Equitable Development: Can Small, Micro and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs) Do the Trick? Development in Practice 15: 463–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinjarak, Yothin, and Ganeshan Wignaraja. 2016. An Empirical Assessment of the Export-Financial Constraint Relationship: How Different are Small and Medium Enterprises? World Development 79: 152–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julita, Julita, and Hasrudy Tanjung. 2019. Development of Porter Generic Strategy Model for Small and Medium Enterprises (SME’s) in Dealing with Asean Economics Community (AEC). International Journal of Recent Scientific Researches 8: 20262–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabanda, Salah Maureen Tanner, and Cameron Kent. 2018. Exploring SME Cyber security Practices in Developing Countries. Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce 28: 269–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaev Schmidt, Tobias, and Wolfgang Sofka. 2009. Liability of foreignness as a barrier to knowledge spillovers: Lost in translation? Journal of International Management 15: 460–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Atsushi, and Takahiro Kato. 2016. Violent Conflicts and Economic Performance of the Manufacturing Sector in India. Kobe: Research Institute for Economics and Business Administrations. [Google Scholar]

- Keynes, John Maynard. 1933. The Means of Prosperity. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Jahaggir H., Abdul Kader Nazmul, Md Farooque Hossain, and Munsura Rahmatullah. 2012. Perception of SME growth constraints in Bangladesh: An empirical examination from institutional perspective. European Journal of Business and Management 4: 256–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kijkasiwat, Ploypailin, and Pongsutti Phuensane. 2020. Innovations and Fir Performance: The Moderating and Mediating Roles of Firm Size and Small and Medium Enterprise Finance. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 13: 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, Maribel Dano, Tristan Canare, and Jamil Paolo Francisco. 2018. Drivers of Philippine SME competitiveness: Results of the 2018 SME survey. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maarof, Mohd Ghazali, and Fatimah Mahmud. 2016. A Review of Contributing Factors and Challenges in Implementing Kaizen in Small and Medium Enterprises. Procedia Economics and Finance 35: 522–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, Mariana, and Maria Macris. 2014. Analysis of the SMEs Development in Romania in the Current Europian Context Affected by the Global Economic Crisis. Procedia Economics and Finance 15: 663–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Will. 2001. Trade Policies, Developing Countries, and Globalization. Washington: Development Research Group, World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, Richard G. P. 1998. Stage Models of SME Growth Reconsidered. Small Enterprise Research 6: 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Dannu, Lioyd Steier, and Isabelle Le Breton-Miller. 2003. Lost in time: Intergenerational succession, change, and failure in family businesses. Journal of Business Venturing 16: 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulhern, Alan. 1996. Vanezuelan Small Businesses and the Economic Crisis: Reflection from Europe. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research 2: 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumbua, Mutisya Swabra. 2013. Competitive Strategies Applied by Small and Medium-Sized Firms in Mombasa County, Kenya. Master’s thesis, School of Business, Univerity of Nairobi, Nirobi, Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- Mundim, Ana, Alessandro Rossi, and Andrea Stochetti. 2000. SMEs in Global Market: Challenges, Opportunities and Threats. Brazilian Electronic Journal of Economics 3: 418–25. [Google Scholar]

- Munro, D. 2013. A Guide to Financing SMEs. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa, Hamidatun Khusna, and Sabariah Yaakub. 2018. Innovation and Technology Adoption Challenges: Impact on SMEs’ Company Performance. International Journal of Accounting, Finance and Business 3: 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Mwika, Dickson, Alick Banda, Christopher Chembe, and Douglas Kunda. 2018. The Impact of Globalization on SMEs in Emerging Economies: A case Study of Zambia. International Journal of Business and Social Science 9: 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narjoko, Dionisius, and Hai Hill. 2007. Winners and Losers during a Deep Economic Crisis: Firm-level Evidence from Indonesian Manufacturing. Asian Economic Journal 21: 343–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narteh, Bedman. 2008. Knowledge transfer in developed-developing country inter-firm collaborations: A conceptual framework. Journal of Knowledge Management 12: 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndeye, Lutfi Abdul Razak, Ruslan Nagayev, and Adam Ng. 2018. Demystifying Small and Medium Enterprises’ (SMEs) Performance in Emerging and Developing Economies. Borsa Istanbul Review 18: 269–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noe, Raymond A., John R. Hollenbeck, Barry Gerhart, and Patrick M. Wright. 2017. Human Resource Management: Gaining a Competitive Advantage, 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Nugent, Jeffrey B., and Seung-Jae Yhee. 2002. Small and Medium Enterprises in Korea: Achievements. Constraints and Policy Issues. Small Business Economics 18: 85–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, Mahendra Adhi, Arief Zuliyanto Susilo, M. Andryzal Fajar, and Diana Rahmawati. 2017. Exploratory Study of SMEs Technology Adoption Readiness Factors. Procedia Computer Science 124: 329–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obalade, Timothy A. Falade. 2014. Analysis of Dumping as a Major Cause of Import and Export Crises. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 4: 233–39. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2008. Annual Report 2008. Paris: Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2009. Top Barriers and Drivers to SME Internationalization, Report by the OECD Working Party on SME and Entrepreneurship. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2014. Annual Report 2014. Paris: Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2019. Report on G20 Trade and Investment Measures. Paris: OECD, WTO and UNCTAD. [Google Scholar]

- Ogechukwu, Ayozie Daniel, Jacob. S. Oboreh, F. Umukoro, and Ayozie Victoria Uche. 2013. Small and Medium Scale Enterprises (SMEs) in Nigeria the Marketing Interface. Global Journal of Management and Business Research Marketing 13: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, Jeen Wei, Hisamuddin Ismail, and Peik Foong Yeap. 2010a. Malaysian small and medium enterprises: The fundamental problems and recommendations for improvement. Journal of Asia Entrepreneurship and Sustainability 6: 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, Jeen Wei, Hishamuddin Bin Ismail, and Gerald Guan Gan Goh. 2010b. The Competitive Advantage of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs): The Role of Entrepreneurship and Luck. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 23: 373–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozar, Semsa, Gokhan Ozertan, and Zeynep Burcu Irfanoglu. 2008. Micro and Small Enterprise Growth in Turkey: Under the Shadow of Financial Crisis. The Developing Economies 46: 331–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaoikonomou, Eleni, Pere Segerra, and Xiaon Li. 2012. Entrepreneurship in the Context of Crisis: Identifying Barriers and Proposing Strategies. International Advances in Economic Research 18: 111–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelham, Alfred M. 2000. Market orientation and other potential influences on performance in small and medium-sized manufacturing firms. Journal of Small Business Management 38: 48–67. [Google Scholar]

- Poon, Simpson. 2002. Have the SME benefit from e-commerce. Australian Journal of Information Systems 10: 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, Michael E. 1985. Competitive Advantage. New York: The Free Press, pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Prasanna, RPIR. 2009. Impact of GSP+ Scheme on Sri Lankan Apparel Industry. Saga: Saga University. [Google Scholar]

- Prasanna, RPIR, JMSB Jayasundara, Sisira Kumara Naradda Gamage, EMS Ekanayake, PSK Rajapakshe, and GAKNJ Abeyrathne. 2019. Sustainability of SMEs in the Competition: A Systemic Review on Technological Challenges and SME Performance. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market and Complexity 5: 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, Muhammad Imran, Khalid Zaman, and Mansoor Nazir Bhatti. 2011. The impact of culture and gender on leadership behavior: Higher education and management. Management Science Letters 1: 531–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakesh, C. 2014. Pest analysis for micro small medium enterprises sustainability. Journal of Management and Commerce 1: 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ramskogler, Paul. 2015. Tracing the Origins of the Financial Crisis. OECD Journal 2: 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappa, Michael A. 2004. The utility business model and the future of computing services. IBM System Journal 43: 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Shengce, Andreas B. Eisingerich, and Huei-Ting Isai. 2015. How Do Marketing Research and Development Capabilities, and Degree of Internationalization Synergistically Affect the Innovation Performance of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs)? A Panel Data Study of Chinese SMEs. International Business Review 24: 642–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, John Lewis, T-Sb Liao, NC Martin, and Peter Galvin. 2012. The role of strategic alliances in complementing firm capabilities. Journal of Management and Organization 18: 858–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, Bernard N, and Stewart A Washburn. 1999. Developing strategy. Journal of Management Consulting 10: 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, Todd, and Walter Enders. 2008. Economic Consequences of Terrorism in Developed and Developing Countries: An Overview. In Terrorism, Economic Development and Political Openness. Edited by Phillip Keefer and Normal Loayza. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 17–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sceulovs, Deniss, and Elina Gaile-Sarkane. 2014. Impact of e-Environment on SMEs Business Development. 2014. Proceedia Social and Behavioral Science 156: 409–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sener, Sefer, Mesut Savrul, and Orhan Aydın. 2014. Structure of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Turkey and Global Competitiveness Strategies. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 150: 212–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, Mupemhi, Richard Duve, and Ronicah Mupemhi. 2013. Factors Affecting the Internationalization of Manufacturing SMEs in Zimbabwe. Gweru: Investment Climate and Business Environment Research Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Shihadeh, Fadi, Sisira Kumara Naradda Gamage, and Azzam (M. T.) Hannoon. 2019. The causal relationship between SME sustainability and banks’ risk. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 32: 2743–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shutyak, Yulia, and Didier Van Caillie. 2015. The Role of Government in Path-Dependent Development of SME Sector in Ukraine. Journal of East-West Business 21: 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Rajesh K., Suresh K. Garg, and S. G. Deshmukh. 2008. Strategy Development by SMEs for Competitiveness: A Review. Benchmarking: An International Journal 15: 525–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Rajesh K., Suresh K. Garg, and S. G. Deshmukh. 2009. The Competitiveness of SMEs in Globalized Economy, Observations from China and India. Management Research Review 33: 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinnathurai, Vijayakumar. 2013. Growth and Issues of Small and Medium Enterprises in Post Conflict Jaffna Sri Lanka. Economia Seria Management 16: 38–53. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, Stanley F., and John C. Narver. 1990. The Effect of a Market Orientation on Business Profitability. Journal of Marketing 54: 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soon, Tan Thiam. 1994. A Pragmatic Approach to SME Development in Singapore. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 11: 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, Peter, Oya Pinar Ardic, and Martin Hommes. 2013. Closing the Credit Gap for Formal and Informal Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises. Washington: International Finance Corporation, World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbock, Dan. 2018. US-China Trade War and Its Global Impacts. China Quarterly of International Strategic Studies 4: 515–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockdale, Rosemary, and Craig Standing. 2004. Benefits and barriers of electronic marketplace participation: An SME perspective. Journal of Enterprise Information Management 17: 301–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Pierre, Josee, Luc Foleu, Georges Abdulnour, Serge Nomo, and Maurice Fouda. 2015. SME Development Challenges in Cameroon: An Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Perspective. Transnational Corporations Review 7: 441–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, Elizabeth. 2011. Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons from Countries and the Literature. Oxfam Research Report. Nairobi: Oxfam, pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Sulayman, Muhammad, Cathy Urquhart, Emilia Mendes, and Stefan Seidel. 2012. Software process improvement success factors for small and medium web companies: A qualitative study. Information and Software Technology 54: 479–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Chang-Young, Ki-Chan Kim, and Sungyong In. 2016. Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Policy in Korea from the 1960s to the 2000s and Beyond. Small Enterprise Research 23: 262–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambunan, Tulus T. H. 2018. The Impact of Economic Crisis on Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises and Their Crisis Mitigation Measures in Southeast Asia With Reference to Indonesia. Asia and Pacific Policy Studies 6: 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todaro, Michae P., and Stephen C. Smith. 2015. Economic Development. Washington: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Tuluce, Nadide Sevil, and Ibrahim Dogan. 2014. The Impact of Foreign Direct Investments on SMEs’ Development. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 150: 107–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. 2009. Globalization of Production and the Competitiveness of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises in Asia and Pacific: Trends and Prospects. New York: Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yihan, Ari Van Assche, and Ekaterina Turkina. 2018. Antecedents of SME Embeddedness in Inter-Organizational Networks: Evidence from China’s Aerospace Industry. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 30: 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WEO. 2020. World Economic Outlook. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Wiid, Johannes A., Michael C. Cant, and Lizna Holtzhausen. 2015. SWOT analysis in the small business sector of South Africa: Friend or foe? Corporate Ownership and Control 13: 446–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WTO. 2016. World Trade Report—Levelling the Trading Field for SMEs. Washington: World Trade Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Henry, and Taewon Suh. 2014. Perceived resource deficiency and internationalization of small- and medium-sized firms. Journal of International Entrepreneurship 12: 207–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, İhsan. 2012. Developing a Multi-Criteria Decision Making Model for PESTEL Analysis. International Journal of Business and Management 7: 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, Srilata, and Akbar Zaheer. 2001. Market micro structure in a global B2B network. Strategic Management Journal 22: 859–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, Muhammad, Wen Jun, and Haseeb Ahmed. 2019. Effect of Terrorism on Economic Growth in Pakistan: An Empirical Analysis. Economic Research 32: 1794–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S. X., X. M. Xie, and C.M. Tam. 2010. Relationship between cooperation networks and innovation performance of SMEs. Technovation 30: 181–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yanlong, and Xiu’s Zhang. 2012. The Effect of Entrepreneurial Orientation on Business Performance: A Role of Network Capabilities in China. Journal of Chinese Entrepreneurship 4: 132–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Naradda Gamage, S.K.; Ekanayake, E.; Abeyrathne, G.; Prasanna, R.; Jayasundara, J.; Rajapakshe, P. A Review of Global Challenges and Survival Strategies of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). Economies 2020, 8, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies8040079

Naradda Gamage SK, Ekanayake E, Abeyrathne G, Prasanna R, Jayasundara J, Rajapakshe P. A Review of Global Challenges and Survival Strategies of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). Economies. 2020; 8(4):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies8040079

Chicago/Turabian StyleNaradda Gamage, Sisira Kumara, EMS Ekanayake, GAKNJ Abeyrathne, RPIR Prasanna, JMSB Jayasundara, and PSK Rajapakshe. 2020. "A Review of Global Challenges and Survival Strategies of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs)" Economies 8, no. 4: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies8040079

APA StyleNaradda Gamage, S. K., Ekanayake, E., Abeyrathne, G., Prasanna, R., Jayasundara, J., & Rajapakshe, P. (2020). A Review of Global Challenges and Survival Strategies of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). Economies, 8(4), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies8040079