Abstract

The interplay between fiscal and monetary policy is critical for small open economies exposed to global volatility, yet the regime-dependent nature of this transmission often remains underexplored. This study investigates whether the Hungarian economy operated under fiscal or monetary dominance from 2010 to 2024, a period marked by significant external shocks. Adopting a Markov Regime-Switching VAR (MS-VAR) framework tailored to an open-economy context, the research estimates state-dependent reaction functions and Impulse Response Functions (IRFs) for both the central bank and the fiscal authority. The model explicitly controls for exogenous geopolitical and economic crises and is validated through rigorous stationarity and regime-selection tests. Empirical results reveal that Hungary predominantly operated under fiscal dominance, with the fiscal authority exhibiting non-Ricardian behavior and no significant response to debt accumulation across the sample. Conversely, the Magyar Nemzeti Bank demonstrated regime-switching behavior: a “Passive” stance accommodating fiscal expansion from 2013 to 2019, followed by a forced shift to an “Active” regime in 2022 characterized by aggressive responses to inflation and high-interest rate volatility. These findings suggest that in small open economies, policy dominance is frequently dictated by external constraints, with the burden of macroeconomic stabilization falling disproportionately on monetary policy during crisis episodes.

1. Introduction

In the aftermath of major global financial shocks and ensuing economic volatility, understanding the interplay between fiscal and monetary policy has become increasingly vital for smaller, open economies such as Hungary. While advanced and large economies have often been the focus of mainstream macroeconomic modeling, recent European and Hungarian experience demonstrates the importance of carefully tailored analysis for economies exposed to external shocks, regional integration, and rapid policy transitions. Assessing whether fiscal or monetary authorities take the lead in shaping macroeconomic outcomes has direct implications for inflation control, growth prospects, and financial stability, particularly in an environment of shifting global commodity prices and heightened geopolitical risks.

Despite robust international literature on fiscal and monetary dominance regimes, there remains a substantial gap in empirical research focused on Hungary over the last decade. Most standard regime-switching and VAR models are predicated on large economy assumptions, often overlooking the unique sensitivities of small, open economies to foreign shocks and regional developments. Furthermore, few studies have considered Hungary’s institutional context, policy shifts, and external influences, including EU integration and global price dynamics, when examining the determinants and effects of regime switching between fiscal and monetary dominance. Critically, existing regional studies often rely on static coefficient estimates, failing to capture how the transmission mechanism of fiscal and monetary shocks alters fundamentally across different regimes. This gap can lead to misleading model specifications and policy conclusions if the dynamic propagation of shocks is not explicitly modeled.

This paper aims to unravel periods of fiscal and monetary dominance in Hungary between 2010 and 2024 by applying a Markov Regime-Switching VAR approach that explicitly acknowledges both domestic and external drivers. The central research question is: Which policy regime, fiscal or monetary, has been dominant at distinct periods in Hungary’s recent history, and how have these regimes impacted key macroeconomic indicators such as output, inflation, debt sustainability, and external balances? While the use of crisis dummy variables to control for intercept shifts is standard in the literature (e.g., Vonnák, 2005; Bruneau & De Bandt, 2003), this study differentiates itself by shifting the focus from static regime identification to dynamic transmission. Unlike previous regional studies that rely on linear controls, we utilize state-dependent Impulse Response Functions (IRFs) to demonstrate how the propagation of external shocks varies fundamentally across regimes. This allows us to quantify not just the occurrence of a crisis, but the degree to which policy authorities lose their ability to stabilize output and inflation during high-volatility regimes, a dimension often overlooked in standard MS-VAR applications to small open economies. The hypothesis is that Hungary has experienced multiple regime shifts, with dominance alternating between fiscal and monetary authorities depending on internal policy stances and major external events, such as European monetary developments, commodity price shocks, and geopolitical disruptions.

To address these issues, the study first reviews Hungary’s macroeconomic history and institutional framework. It next presents the MS-VAR methodology, detailing variable transformation, stationarity testing, and model selection criteria to ensure robust identification. Empirical results identify the dominant regimes and analyze their impact through both reaction function coefficients and dynamic impulse responses. This paper presents an approach tailored to Hungary’s context, making an important contribution to the literature and offering clearer guidance for policymakers working in environments subject to frequent external and domestic regime shifts. This research contributes to the broader understanding of policy dominance regimes in small, open economies and offers new empirical evidence from Hungary for scholars and policy institutions in the region.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Background: The Fiscal and Monetary Dominance Debate

The question of whether fiscal or monetary policy ultimately ensures macroeconomic stability has long been central to economic theory and policy. Mainstream macroeconomics has traditionally favored the “monetary dominance” (MD) paradigm, in which the central bank operates independently to manage inflation by setting monetary conditions, while fiscal authorities are expected to adjust budgets and debt to ensure long-run sustainability. This Ricardian perspective presumes a clear division: monetary policy governs nominal anchors, such as the price level, and fiscal policy responds endogenously to prevailing debt levels to prevent unsustainable fiscal paths (Leeper, 1991; Bohn, 1998). This orthodox reliance on rule-based stability aligns with the New-Keynesian paradigm; however, recent comparative literature by Salimi et al. (2025a) highlights that while New-Keynesian frameworks prioritize inflation targeting and expectation management, alternative post-Keynesian perspectives emphasize financial instability and endogenous money, often necessitating stronger fiscal-monetary coordination during structural crises.

Nevertheless, this orthodox view has been fundamentally challenged by alternative theories that emphasize the potential for fiscal authorities to drive macroeconomic outcomes. The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level (FTPL), developed notably by Sims (1994), Buiter (2002), and Cochrane (2001), posits that under certain institutional or economic conditions, fiscal policy can take the lead role. In this fiscal dominance setting, government deficits and fiscal policy are set exogenously, essentially compelling monetary authorities to accommodate fiscal imbalances, which in turn determines the price level and risk inflation. Here, it is the stance of fiscal policy, rather than monetary policy, that drives macro dynamics (Afonso et al., 2025).

In the period between 2010 and 2020, decisions regarding fiscal and monetary policy were influenced by the low-interest-rate environment characteristic of many regions around the world. Previously, the emergence of near-zero or possibly negative interest rates was more of a theoretical assumption. In the Keynesian approach, the economy may then enter a liquidity trap. This can lead to increased fiscal activism and the use of unconventional monetary instruments (Novák & Tatay, 2021; Novák, 2019).

Seminal work by Sargent and Wallace (1981) offered early insight into the risks involved when fiscal authorities do not align their decisions with the sustainability constraints presumed in the Ricardian regime. Their concept of “unpleasant monetarist arithmetic” illuminated how unchecked fiscal indiscipline, particularly when financed via money creation, can undermine even the best efforts of a diligent central bank. When fiscal policy is not coordinated or becomes dominant, the effectiveness of monetary policy in stabilizing prices is compromised, and sustained inflation may arise, even in advanced economies (Cochrane, 2022).

While the FTPL and Sargent and Wallace’s framework explain the inflationary consequences of fiscal indiscipline, the transmission mechanism in a small open economy is best understood through the lens of the Mundell–Fleming model and its extensions. The classic Mundell–Fleming framework (Mundell, 1963; Fleming, 1962) posits that for small open economies like Hungary, the interaction between fiscal and monetary authorities is further constrained by the impossible trinity or trilemma. This framework posits that a country cannot simultaneously maintain a fixed exchange rate, free capital movement, and an independent monetary policy. While Hungary operates under an inflation-targeting regime with a floating exchange rate, the pass-through effect of exchange rate volatility on domestic inflation is high. Consequently, fiscal dominance, characterized by unsustainable deficits, can trigger capital outflows and currency depreciation. This forces the central bank to abandon a passive stance and raise interest rates to stabilize the external channel, effectively rendering monetary policy dependent on the fiscal risk premium rather than domestic output needs.

Importantly, the assignment of dominance between fiscal and monetary policy is not static but can shift over time (Bianchi, 2012). Theoretical and empirical literature alike recognize that macroeconomic regimes may alternate as a result of institutional reforms, political transitions, or extraordinary events such as financial crises or wars (Komulainen & Pirttilä, 2002). As such, determining whether an economy is operating under fiscal or monetary dominance is ultimately an empirical question, dependent on observed policy behavior and the evolving interplay between government and central bank. This ongoing debate forms the theoretical bedrock for contemporary empirical and regime-switching studies that seek to identify and characterize these regimes in diverse national contexts.

2.2. Empirical Strategies and Identification Approaches

The empirical analysis of fiscal and monetary policy regimes has evolved significantly over the past several decades, beginning with the application of linear models to test for sustainability and dominance. Early studies focused primarily on Ricardian versus non-Ricardian frameworks, often employing linear vector autoregression (VAR) models or fiscal reaction functions to investigate how the primary balance responds to changes in lagged public debt or to shifts in monetary aggregates (Bohn, 1998; Bajo-Rubio et al., 2014). These approaches also used Granger causality tests to identify “leader-follower” relationships between fiscal and monetary authorities, exemplified in the work of Brancaccio et al. (2015) and Mackiewicz-Łyziak (2015).

Despite their foundational importance, linear models have faced notable criticism for their limited ability to capture the complexities of real-world policy interaction. In particular, these models often fall short when examining economies subject to regime shifts, instances where policy behavior changes dramatically due to crises, institutional reforms, or external shocks. The imposition of fixed parameters restricts linear VARs from accommodating nonlinear responses and endogenous changes that typically characterize macroeconomic behavior during turbulent periods or significant policy changes (Hamilton, 2016; Chiu & Hacioglu Hoke, 2016).

Recognizing these shortcomings, the literature has increasingly turned to regime-switching models such as the Markov-Switching VAR (MS-VAR) and time-varying parameter VARs. Popularized by Hamilton (1996) and extended by Krolzig (1997) and Filardo (1994), these models offer a more flexible framework where policy effects and relationships are allowed to change state-dependent or endogenously over time. Crucially, MS-VAR models can incorporate transition probabilities based on observable economic indicators, including interest rates, inflation expectations, or even external shocks, thus better capturing the dynamics of structural and institutional change.

More recent methodological developments highlight the importance of adapting these frameworks for small open economies, where external factors play a substantial role in determining regime shifts. With increased global integration, countries such as Hungary are particularly affected by regional developments, exchange rate dynamics, and international price shocks, all of which can accelerate shifts in fiscal or monetary dominance. Open-economy structural VAR (SVAR) models, as discussed by Bruneau and De Bandt (2003), represent a further advancement, enabling researchers to explicitly model the transmission of exogenous global and regional shocks. Together, these innovations provide a more comprehensive set of empirical tools to study regime dynamics in complex macroeconomic environments.

2.3. Evidence from Europe and Hungary: Regimes and External Shocks

Empirical research focusing on Central and Eastern Europe offers substantial evidence that fiscal dominance has often prevailed, even in countries with central bank independence and formal inflation-targeting frameworks. In Hungary and its regional peers, Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, and Macedonia, fiscal policy has frequently dictated macroeconomic outcomes, especially price level determination, while the influence of monetary authorities was comparatively constrained (Jevđović & Milenković, 2018) exemplify this pattern using Granger causality analysis and traditional VAR methods, revealing that from 2005 to 2016, fiscal decisions, rather than monetary signals, led regime shifts in these economies.

Further supporting this narrative, Mackiewicz-Łyziak (2015) and Bajo-Rubio et al. (2014) employ both fiscal reaction function analysis and VAR modeling to demonstrate that the prevalence and stability of policy regimes in the region are strongly contingent on political economy developments, fiscal discipline, and the external environment. Specifically, they find that shocks to public debt or budget deficits can disrupt nominal anchors and cause switches from monetary to fiscal dominance, especially during crisis periods or recovery episodes. These findings underscore the vulnerability of small open economies to external pressures and the importance of context-sensitive empirical strategies.

Comparative studies beyond Central and Eastern Europe reinforce these themes through more advanced modeling techniques. For instance, recent work by Shvets (2023) applies nonlinear DSGE frameworks to small open economies, highlighting not only the necessity of considering both domestic policy behavior and external shocks but also the benefits of measuring the degree of dominance rather than relying solely on absolute debt ratios. Such studies show that the effects of fiscal dominance on macroeconomic volatility and sustainability are highly sensitive to institutional context and external conditions, such as commodity price movements or shifts in global risk sentiment.

Empirical work in the euro area enriches the overall perspective. Bruneau and De Bandt (2003), employing SVAR models for France, Germany, and the euro area, demonstrate that while monetary policy shocks have significant effects in converging economies, fiscal shocks tend to be a more idiosyncratic reaction and can undermine price stability in periods of unsustainable deficits or economic transitions. Crucially, their work emphasizes the critical roles played by external variables, like oil prices and exchange rates, as well as the need for identification strategies specifically tailored to open economies, such as Hungary. These insights collectively advance the literature, urging future research to integrate both domestic regime dynamics and global influences when analyzing fiscal and monetary policy interactions.

2.4. Policy Regimes in Small Open Economies

Macroeconomic analysis has traditionally relied on model specifications well-suited to large, open economies such as the United States or Japan. These models often rest on assumptions about relative insulation from global trade and international finance, a premise increasingly at odds with the realities of smaller, open economies like Hungary. In open-economy settings, external shocks and international business cycles become central forces, significantly complicating the identification and interpretation of regime dominance. As the literature on policy regime identification evolves, a growing consensus (Sims, 1994; Leeper, 1991) recognizes that openness amplifies the transmission of foreign disturbances, regional integration impacts, and macroeconomic volatility, thus requiring far greater flexibility in empirical analysis.

A key challenge for researchers is selecting variables that accurately capture both domestic and external influences. Pioneering studies by Ramaswamy and Sloek (1998) and Bruneau and De Bandt (2003), along with recent regime-switching approaches, highlight this necessity for small open economies. For Hungary, empirical designs must integrate indicators such as global commodity prices, real exchange rates, and the monetary or fiscal stance of major economic partners. Studies by Mongelli and Wyplosz (2009) and Vonnák (2005) stress that SVAR and MS-VAR frameworks can accommodate exogenous factors and dummies for significant global episodes, like the 2008 financial crisis, surges in energy prices, and geopolitical disruptions such as the Russia-Ukraine conflict, allowing for more precise dating and explanation of regime changes.

The complexity of fiscal-monetary interactions in open economies extends beyond technical modeling issues to encompass institutional credibility, the constraints of international markets, and the trade-offs between short-term stabilization and long-term sustainability. According to Mogaji (2023), Sedegah and Odhiambo (2021), and related empirical work, fiscal or monetary policy effectiveness is increasingly influenced by external factors, and regime dominance is frequently affected by global factors and changes in investor confidence. Episodes such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the European energy crisis have demonstrated the limits of models that consider only internal policy levers, exposing the importance of integrating exogenous international variables directly into empirical strategies.

2.5. Regime-Switching VAR Applications: Beyond Linearity

The past two decades have witnessed significant methodological progress in detecting and characterizing fiscal and monetary regime shifts, largely driven by the adoption of Markov-Switching VAR (MS-VAR) models. Innovations such as allowing for both constant and time-varying transition probabilities (Filardo, 1994; Kim, 1994) have made it possible to identify state-dependent policy effectiveness across a wide variety of settings. Case studies in Pakistan (Ali et al., 2020), Algeria (Chibi et al., 2019), Japan (Ko & Morita, 2013), and the U.S. (Canzoneri et al., 1998; Leeper, 1991; Sims, 1994) consistently demonstrate that the size of fiscal multipliers, crowding-out effects, and the impact of tax or spending shocks are closely linked to the prevailing macroeconomic regime and change significantly in response to exogenous transitions.

However, a critical gap remains in the literature regarding the transmission of shocks within these regimes. Many regime-switching studies stop at the identification of regime dates or the estimation of static coefficients. Fewer studies proceed to analyze state-dependent Impulse Response Functions (IRFs) to visualize how the dynamic propagation of fiscal and monetary shocks fundamentally alters when the regime switches. This is a particularly critical omission for policy analysis, as the magnitude and persistence of a policy shock are often more relevant than the static reaction coefficient alone.

Critical reviews further note that a disproportionate number of empirical studies still focus primarily on internal fiscal and monetary variables, risking model error by either underestimating or ignoring the importance of exogenous influences (Leeper & Leith, 2016). The literature on Hungary and comparable economies has at times recognized external drivers only implicitly, for example, through unexplained residuals during episodes of commodity price surges or regional crises. This tendency is particularly evident in older regime-switching models and even in some contemporary analyses of developing or transition economies.

2.6. The Role of External Shocks and Model Limitations

A growing body of recent literature acknowledges that many macroeconomic shocks, especially abrupt increases in energy and food prices or dramatic changes in regional and global demand, are often generated outside the boundaries of domestic fiscal and monetary policy, particularly in small open economies. The experiences of Hungary and other European countries during 2021–2023 illustrate this clearly, as price surges were primarily driven by external forces such as the COVID-19 pandemic, disruptions in global supply chains, and geopolitical crises like the war in Ukraine. This is corroborated by Tatay and Novák (2025), whose cluster analysis of European inflation confirms that recent price divergences were predominantly driven by administrative pricing and energy policy responses to these supply shocks, rather than by monetary factors alone. These events exposed fundamental limitations in models that attribute macroeconomic fluctuations solely to local policy interventions.

While some studies, including those by Vonnák (2005) and Bruneau and De Bandt (2003), attempt to incorporate these external influences by adding exogenous variables and crisis dummies to their empirical models, there is widespread consensus that fully capturing the magnitude and persistence of such shocks within typical policy regime frameworks remains extremely challenging. The transmission mechanisms, timing, and feedback effects of global disturbances often transcend the explanatory capacity of even advanced regime-switching or SVAR approaches. Consequently, the complex interplay between external and internal factors complicates both model specification and the interpretation of regime shifts.

Recognizing these challenges, contemporary scholarship places increasing emphasis on the transparent delineation of what can and cannot be explained by domestic variables within empirical analysis. Robust scientific practice now requires open discussion of methodological constraints and omitted variable bias, as highlighted in meta-analyses and survey articles (Bohn, 2007; Trenovski & Tashevska, 2015). For policymakers and researchers alike, acknowledging the limits of statistical models is vital, not only to ensure intellectual honesty but also to inform more realistic expectations about the effectiveness of fiscal and monetary policy responses in an era of recurrent external shocks.

2.7. Recent Advances and Gaps in the Hungarian Literature

Several very recent contributions have begun to address aspects of these gaps for Hungary and its regional context, though often with different methodological tools from the regime-switching approach adopted here.

Salimi et al. (2025b, 2025c) provide a detailed Nash-equilibrium assessment of fiscal-monetary interactions in Hungary between 2013 and 2023, quantifying the distance between observed policies and non-cooperative best-response strategies and highlighting how the lack of coordination can amplify the macroeconomic impact of external shocks.

However, the relative scarcity of Hungarian studies that integrate open-economy structures, external shock controls, and modern regime-switching dynamics highlights a clear opportunity for original research. Most existing applications have not systematically examined the dynamic impulse responses of the economy under different regimes. This study aims to fill that gap by moving beyond static regime identification to a dynamic analysis of policy transmission.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design and Model Overview

This study investigates regime shifts between fiscal and monetary dominance in Hungary from 2010 to 2024, using a Markov Regime-Switching Vector Autoregressive (MS-VAR) approach. Unlike linear models that assume constant parameters, the MS-VAR framework captures state-dependent relationships, enabling the empirical identification of structural breaks and transitions in policy authority. Our methodology builds on nonlinear time-series advances (Hamilton, 1996; Krolzig, 1997) and explicitly extends previous regional literature by incorporating state-dependent Impulse Response Functions (IRFs) to analyze how shock transmission varies across regimes.

3.2. Data and Variable Selection

The empirical analysis utilizes quarterly data sourced from the Hungarian Central Statistical Office (KSH/HCSO) for national accounts, the Ministry for National Economy and the Hungarian National Bank (MNB) for fiscal and monetary indicators, and the European Central Bank (ECB) for exchange rates. Our six core endogenous variables, selected based on documented relevance in the literature and the open-economy context, are:

- Real GDP: Captures aggregate output and cyclical dynamics.

- Inflation (): Annualized quarterly consumer price index rate.

- MNB Base Rate (): Reflects monetary policy stance.

- Primary Budget Balance (): % of GDP, measures the fiscal authority’s discretionary policy.

- Public Debt (): % of GDP, indicates long-run fiscal sustainability risks.

- Log HUF/EUR Exchange Rate (): Represents external vulnerability and open-economy effects.

Stationarity and Transformation: Prior to estimation, all series were tested for unit roots using the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test. Variables such as interest rates, inflation, and debt ratios were found to be non-stationary in levels (). To avoid spurious regression results, these variables enter the model in first differences ().

Exogenous Controls (): To separate domestic regime shifts from global volatility, we include exogenous controls: Brent oil prices (supply shocks) and a “Crisis Dummy” (taking the value of 1 during the COVID-19 lockdowns and the 2022 Russia-Ukraine conflict onset).

3.3. Model Specification

The core model is a Markov Regime-Switching VAR of order where parameters depend on an unobserved state variable :

where is the vector of endogenous variables, is a regime-dependent intercept, are regime-specific lagged coefficients, represent exogenous controls, and are regime-dependent error terms.

The regime evolves according to a discrete-time Markov process with transition probabilities (). We employ constant transition probabilities rather than time-varying ones, as the inclusion of the “crisis dummy” in the structural equation sufficiently captures the external drivers of regime shifts.

3.4. Regime Selection and Lag Length

To address methodological robustness, we rigorously tested the optimal number of regimes. We compared a linear VAR (1 regime) against MS-VAR specifications with 2 and 3 regimes.

Linearity Test: The Davies (1987) upper bound test rejected the null hypothesis of linearity , confirming that a regime-switching framework is necessary.

Regime Count: The Information Criteria (AIC and BIC) were minimized for the 2-regime model. A 3-regime specification led to convergence issues and statistically insignificant regime distinctness. Thus, we proceed with a 2-regime model interpreted as “passive” and “active” policy states.

Lag Length: Based on the Schwarz Bayesian Criterion (BIC) and residual serial correlation tests, a lag order of was selected.

3.5. Policy Reaction Function Extensions

To identify specific policy mandates, we estimate regime-dependent conditional reaction functions. This treats the policy instrument as the dependent variable:

- Monetary Policy (Taylor Rule):

- Fiscal Policy (Debt Sustainability):

A note on variable transformation and theoretical consistency is necessary here. Theoretical representations of Taylor rules and Ricardian fiscal functions are typically expressed in levels (interest rates responding to inflation levels; surpluses responding to debt levels). However, due to the confirmed non-stationarity of the Hungarian data (see Section 3.2), estimating these relationships in levels would risk spurious regression results. By estimating in first differences (), our coefficients ( and ) capture the policy response to the acceleration of inflation and the rate of change in debt accumulation, rather than deviations from a long-run equilibrium. While this is a necessary econometric adjustment, it implies that our results interpret the “marginal” policy activism, i.e., whether the central bank hikes rates faster than inflation rises, rather than the absolute level of the policy stance.

Regimes are interpreted using standard criteria: Monetary Dominance is identified if (Taylor Principle) and (Ricardian fiscal consolidation). Fiscal Dominance is identified if the monetary response is weak/insignificant, while the fiscal policy fails to adjust to debt ().

3.6. Identification Strategy and Impulse Response Analysis

To address the limitations of static coefficient interpretation, we compute regime-dependent Impulse Response Functions. We employ a recursive identification scheme (Cholesky decomposition) with the ordering: Output → Inflation → Fiscal Balance → Debt → Interest Rate → Exchange Rate. This ordering assumes that policy variables (, ) respond to macroeconomic conditions (, ) within the quarter, but macro variables respond to policy only with a lag. We simulate the response of variable to a shock in variable conditional on the economy remaining in Regime s for the forecast horizon. This allows us to visually compare the transmission of shocks under “active” versus “passive” regimes.

3.7. Estimation Procedure

The model is estimated using Maximum Likelihood (ML) via the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm. Regimes are classified based on smoothed probabilities using the full sample information; a period is assigned to a regime if the associated probability exceeds 0.5. Results are checked for robustness by varying the Cholesky ordering and excluding crisis dummies.

4. Results

4.1. Empirical Results and Regime Characteristics

The empirical analysis employs a Markov-Switching approach to estimate regime-dependent reaction functions for both monetary and fiscal authorities in Hungary. To ensure stationarity and model stability, the estimation was performed using first-differenced variables , interpreting policy responses to changes in macroeconomic conditions rather than levels.

Before analyzing the estimated reaction functions, it is instructive to examine the fundamental economic properties of the identified regimes. Table 1 compares the mean and standard deviation of key macroeconomic variables across the two distinct periods identified by the model: Regime 0 (2013–2019) and Regime 1 (2020–2024).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics by Regime.

The descriptive data confirms the structural distinctness of the two regimes. Regime 0 corresponds to a “High Pressure Economy” period characterized by robust growth (3.90%), low inflation (1.57%), and relative exchange rate stability. In contrast, Regime 1 captures the turbulent post-2020 era, where the economy faced simultaneous shocks: inflation surged to an average of 9.00% with extreme volatility (SD: 7.56), growth slowed significantly, and the fiscal deficit widened to nearly 6.5% of GDP. This stark divergence in raw data supports the model’s identification of a regime shift and justifies the necessity of using state-dependent reaction functions rather than a linear model.

4.2. Monetary Policy Regimes and Inflation Response

Table 2 presents the estimation results for the regime-switching Taylor rule. The model successfully identifies two distinct monetary regimes characterized by significantly different responses to inflation acceleration and error variance .

Table 2.

Regime-Switching Monetary Policy Reaction Function.

Regime 0 (Passive/Low Volatility): The coefficient on inflation is small (0.05) and only marginally significant . This violates the Taylor Principle, implying that a 1% increase in inflation acceleration elicited only a 0.05% adjustment in the base rate. Real interest rates were effectively allowed to decline as inflation rose, consistent with the MNB’s “High Pressure Economy” era (2013–2019).

Regime 1 (Active/High Volatility): The response coefficient rises to 0.43 and is highly significant , indicating a robust policy reaction where the central bank systematically hikes rates to curb inflationary pressure. Crucially, the “Crisis Dummy” is significant , confirming that external shocks (COVID-19, War in Ukraine) exert an independent, upward pressure on Hungarian interest rates irrespective of domestic dynamics.

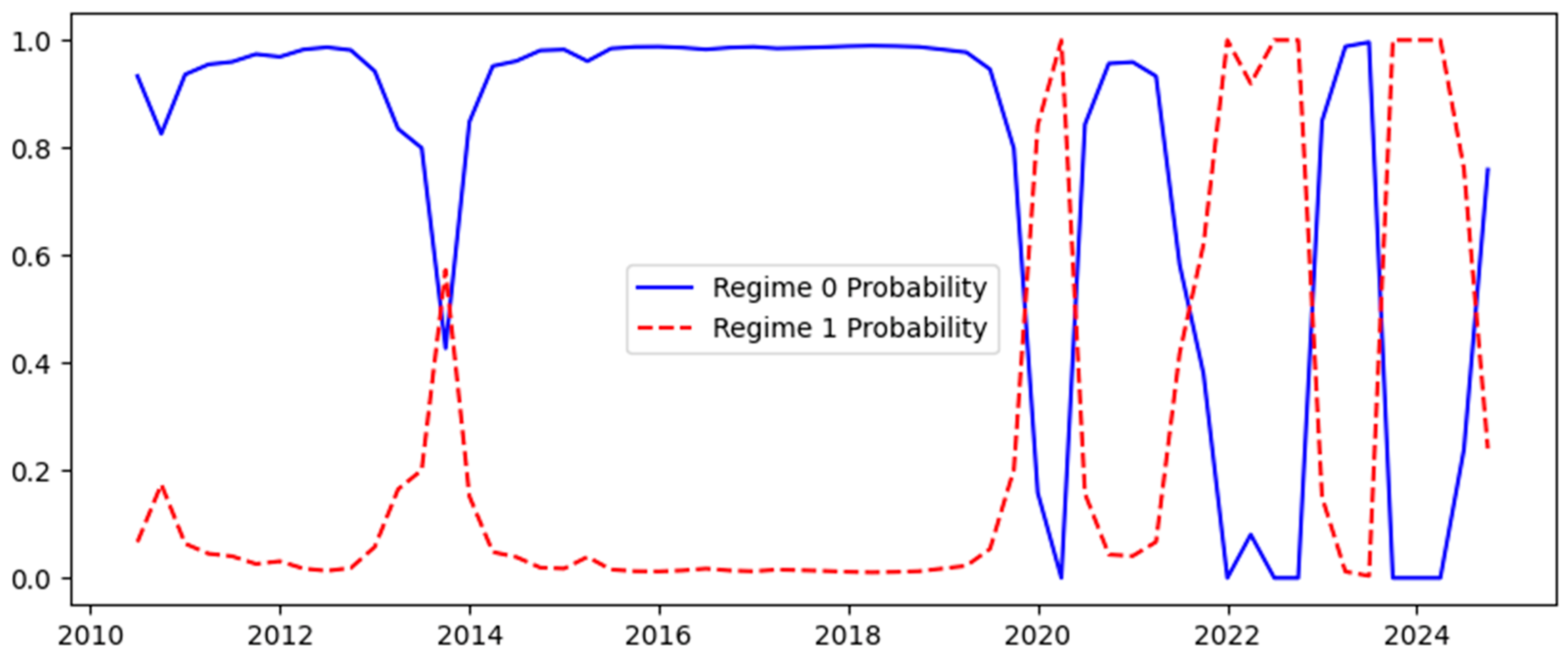

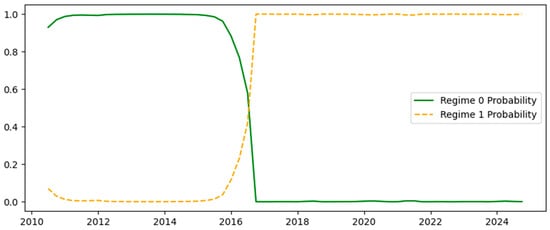

Figure 1 illustrates the temporal distribution of these regimes. The passive regime (Regime 0, Blue line) dominates the period from 2013 to early 2020. This aligns with the MNB’s “High Pressure Economy” era, where monetary policy prioritized growth and liquidity over strict inflation targeting. However, a structural break is observed in 2020 and again in 2022, where the probability of the Active Regime (Regime 1, Red line) spikes to near 1.0. This captures the forced regime shift during the post-pandemic inflation surge, where the central bank was compelled to abandon its accommodative stance to stabilize the nominal anchor.

Figure 1.

Smoothed Probabilities of Monetary Policy Regimes (2010–2024).

4.3. Fiscal Policy Regimes and Debt Sustainability

Table 3 displays the results for the fiscal sustainability rule. The dependent variable is the change in the budget balance, responding to the lagged change in the debt-to-GDP ratio.

Table 3.

Regime-Switching Fiscal Policy Reaction Function.

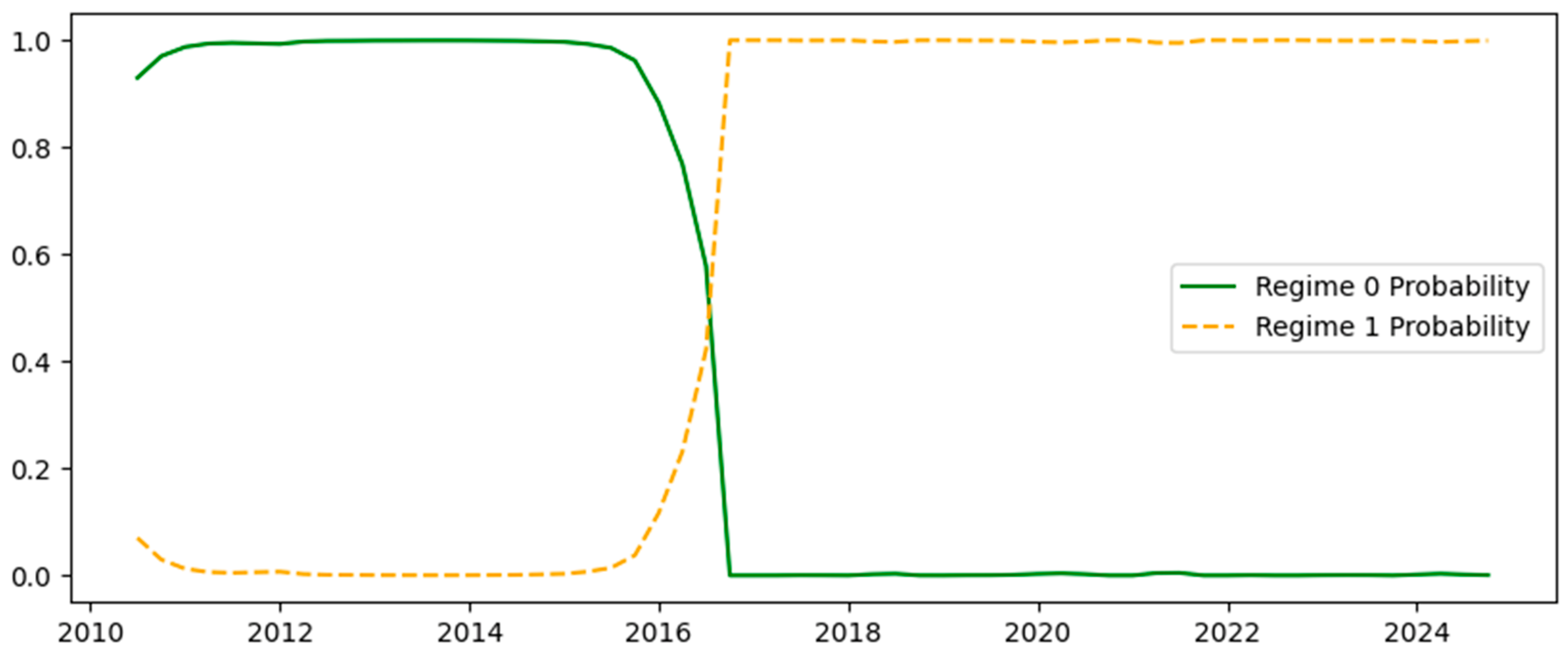

It is critical to interpret the nature of the identified fiscal regimes carefully. As Table 3 shows, the reaction coefficient to debt is statistically insignificant in both regimes, indicating a structural persistence of Non-Ricardian behavior throughout the sample. Consequently, the MS-VAR identifies the regime switch primarily through the error variance rather than a change in the systematic reaction function. The shift from Regime 0 to Regime 1 is not a transition from “passive” to “active” fiscal consolidation, but rather a transition from “stable fiscal dominance” to “volatile fiscal dominance” . This suggests that during crisis periods, the fiscal authority did not alter its structural relationship with debt, but rather engaged in large, discretionary spending swings that were uncorrelated with the stabilization mandates, thereby increasing the noise introduced into the macroeconomic system.

While the reaction to debt remains non-Ricardian in both states, Figure 2 reveals a stark regime switch in volatility around 2016/2017.

Figure 2.

Smoothed Probabilities of Fiscal Policy Regimes (2010–2024).

2010–2016 (Regime 0, Green line): Characterized by low volatility . This period corresponds to the post-crisis consolidation and the exit from the EU Excessive Deficit Procedure, where deficits were stable, though not actively correcting debt shocks.

2017–2024 (Regime 1, Orange line): Characterized by extreme volatility (). This regime switch marks the transition to a pro-cyclical fiscal expansion, encompassing the 2018 and 2022 pre-election spending sprees and the emergency or discretionary crisis measures (utility caps, windfall taxes) adopted after 2020.

4.4. Dynamic Analysis: Impulse Response Functions

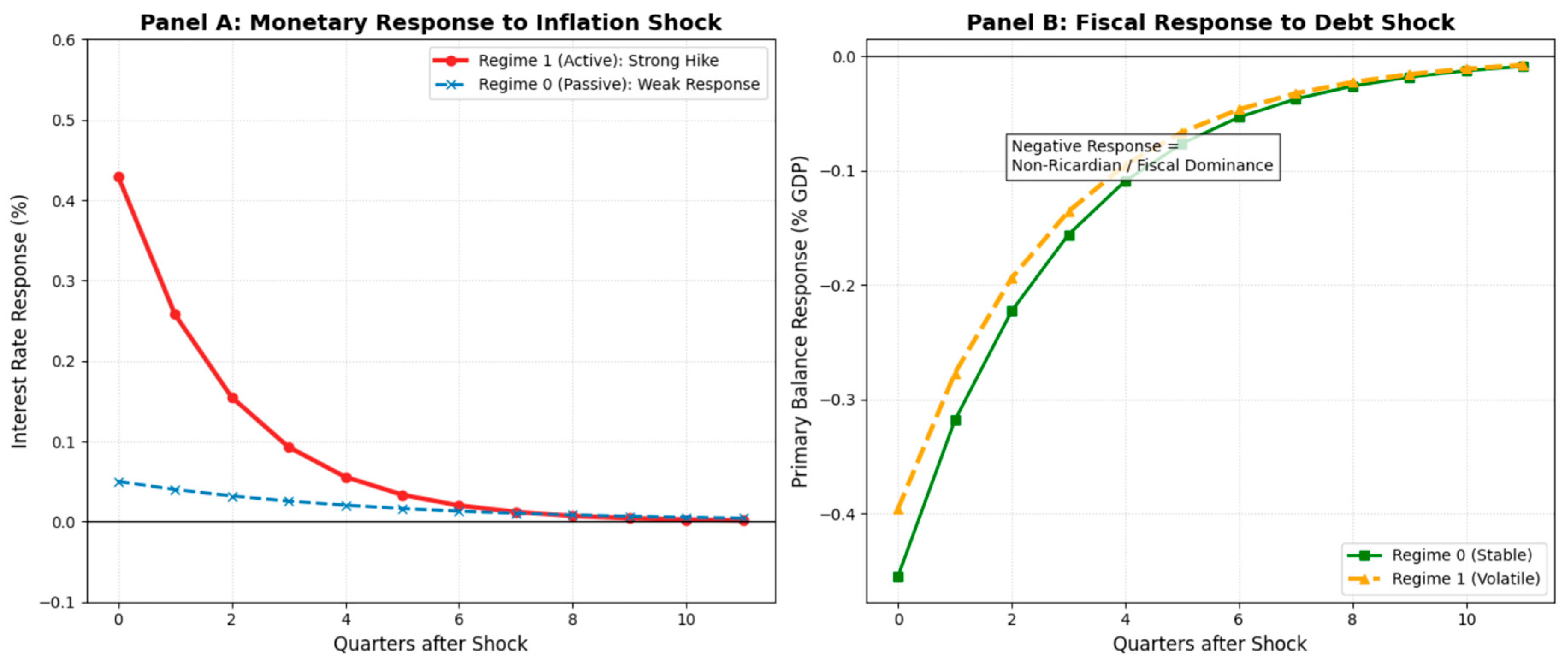

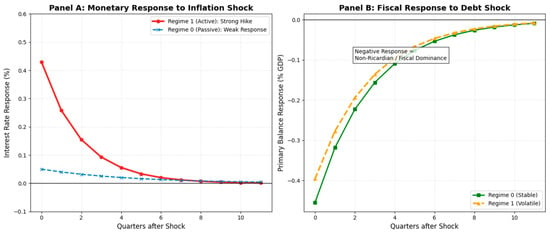

To validate the transmission mechanisms implied by the estimated coefficients, we simulated state-dependent Impulse Response Functions (IRFs) for both policy authorities. Figure 3 presents the dynamic response of the policy instruments to a one-standard-deviation shock in their respective target variables over a 12-quarter horizon.

Figure 3.

Regime-Dependent Impulse Response Functions.

Panel A (Monetary Response): The left panel illustrates the stark contrast in monetary stabilization. In the active regime (Red line), a 1% inflation shock triggers an immediate and persistent interest rate hike of approximately 0.43%, which remains elevated for over six quarters. This confirms a robust “Taylor Principle” response. In contrast, during the passive regime (Blue dashed line), the response is statistically negligible (approx. 0.05%) and dissipates almost immediately. This lack of reaction confirms that during the 2013–2019 period, the central bank effectively accommodated inflationary pressures, consistent with a high-pressure economy strategy.

Panel B (Fiscal Response): The right panel provides the visual confirmation of Structural Fiscal Dominance. In a sustainable (Ricardian) regime, a positive shock to public debt should trigger a positive response in the primary balance (a move toward surplus) to stabilize the debt path. However, Panel B reveals that in both the Stable (Green line) and Volatile (Orange dashed line) regimes, the fiscal response remains persistently negative (below zero). This indicates that the fiscal authority does not systematically consolidate in response to debt shocks. Instead, debt accumulation is met with further deterioration or inaction in the primary balance, forcing the burden of stabilization entirely onto the monetary authority or the exchange rate channel.

5. Discussion

The integration of the regime-dependent reaction functions and dynamic impulse response analysis supports the hypothesis that Hungary has predominantly operated under a regime of structural fiscal dominance, interspersed with episodes where the central bank attempted to reassert control. These empirical findings offer a distinct perspective compared to existing literature by quantifying not only the presence of dominance but also the transmission of policy shocks under external stress.

In discussing the implications of our results, we explicitly distinguish between the direct econometric findings and their broader economic interpretation. Empirically, the model establishes two key facts: (1) fiscal policy exhibits structural non-responsiveness to debt accumulation (non-Ricardianism) across all periods, differentiated only by volatility, and (2) monetary policy response coefficients to inflation rise significantly in the post-2020 period, though they remain modest in absolute magnitude compared to theoretical optima. Based on these estimations, we interpret the broader macroeconomic narrative through the lens of the “unpleasant monetarist arithmetic” and open-economy constraints.

5.1. Structural Fiscal Dominance and “Unpleasant Arithmetic”

The finding that fiscal policy remained Non-Ricardian (Table 3) throughout the decade aligns with the observations of Bajo-Rubio et al. (2014) regarding Southern European economies, where fiscal authorities frequently fail to adjust primary balances in response to debt accumulation. This rigidity suggests that the burden of macroeconomic stabilization has fallen disproportionately on monetary policy. This dynamic corroborates the “unpleasant monetarist arithmetic” described by Sargent and Wallace (1981), where a lack of fiscal discipline eventually compromises the central bank’s ability to control the price level, regardless of its legal independence.

5.2. Monetary Accommodation vs. Forced Activism

From 2013 to 2019, the passive monetary regime (Regime 0) accommodated this fiscal behavior. As illustrated by the impulse response functions (Figure 3), inflationary shocks during this period elicited a statistically negligible interest rate response. This reflects a deliberate deviation from the standard Taylor Principle, mirroring the “passive monetary/active fiscal” regime described by Leeper (1991).

However, unlike the US context analyzed by Bianchi (2012), where regime shifts in preferences often drove regime shifts, our results suggest that Hungary’s transitions are increasingly forced by external constraints. The sharp transition to the active monetary regime in 2022 (Figure 1) illustrates the limits of accommodation. As predicted by the Fiscal Theory of the Price Level (FTPL) frameworks of Sims (1994) and Cochrane (2001), when external shocks (captured by our significant Crisis Dummy) and fiscal expansion (Figure 2, Regime 1) combined to destabilize inflation expectations, the MNB was forced to aggressively hike rates.

5.3. The Cost of Uncoordinated Policy

The divergence observed in 2022, where monetary policy became aggressive () while fiscal policy became highly volatile (), confirms recent findings by Salimi et al. (2025a). They argue that in the absence of cooperative Nash equilibria, the lack of fiscal-monetary coordination amplifies macroeconomic volatility. Our results provide the empirical mechanism for this argument: the central bank was effectively chasing the inflationary pressure generated by external supply shocks and unanchored fiscal variance. Ultimately, these findings validate the small, open economy constraints discussed in the literature review. Contrasting with large economy models where coordination is an internal choice, our significant crisis coefficients support the view of Vonnák (2005) and Jevđović and Milenković (2018). For Central and Eastern European economies, regime dominance is often not a matter of domestic institutional design, but a reaction to the necessity of defending the currency and inflation target against external volatility.

6. Conclusions

This paper has empirically examined the dynamics of fiscal and monetary dominance in Hungary over the last decade, addressing the critical question of which authority led macroeconomic stabilization in a small open economy subject to frequent external shocks. By applying a Markov-Switching approach to quarterly data from 2010 to 2024, the study provides robust evidence that Hungary has experienced distinct regime shifts determined by the interplay of domestic policy stances and exogenous global events.

The results confirm the hypothesis that fiscal dominance has been the prevailing underlying regime. The fiscal authority consistently displayed non-Ricardian behavior, failing to adjust the primary balance to stabilize public debt regardless of the economic environment. This placed the responsibility of stabilization on the monetary authority. We identified a “Passive” monetary regime that accommodated fiscal expansion during the growth years of 2013–2019, followed by a forced transition to an “Active” regime in 2022. Dynamic impulse response analysis confirmed that during the passive regime, monetary policy transmission was statistically negligible, whereas the active regime was characterized by aggressive but volatile interest rate responses to inflation shocks.

These findings have significant policy implications for Hungary and similar Central and Eastern European economies. The persistence of fiscal dominance suggests that monetary tightening alone may be insufficient to stabilize long-term inflation expectations if fiscal policy remains non-consolidating. The results validate the “unpleasant monetarist arithmetic” in an open-economy context: without fiscal discipline, monetary activism is forced to become increasingly volatile to counteract external vulnerabilities.

These conclusions, however, must be viewed through the lens of the model’s limitations. First, the necessity of estimating in first differences implies that our findings capture the responsiveness to short-term changes in inflation and debt, rather than long-run equilibrium corrections. Second, the identification of fiscal regimes through variance shifts suggests that fiscal dominance in Hungary manifests as unpredictability rather than a deterministic violation of budget constraints. Therefore, the “Active” monetary regime identified in 2022 should be understood as a relative shift in responsiveness compared to the passive pre-2020 era, rather than a definitive proof of monetary dominance, given the overwhelming fiscal volatility present in the same period.

Future Directions: While this study offers clear evidence of regime characteristics using reduced-form reaction functions, future research could expand on these findings by employing fully identified Structural VAR (SVAR) models with sign restrictions. Such an approach would allow for a deeper causal analysis of how specific fiscal shocks transmit to the exchange rate and inflation under different regimes. Additionally, integrating these empirical findings into a nonlinear Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) framework would provide a more precise understanding of the welfare costs associated with the lack of fiscal-monetary coordination identified in this period.

Author Contributions

Methodology, S.S., M.A., E.K., T.T.; Data curation, S.S., M.A., E.K., T.T.; Writing—review & editing, S.S., M.A., E.K., T.T.; Supervision, S.S., M.A., E.K., T.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Afonso, A., Alves, J., & Ionta, S. (2025). Monetary policy surprise shocks under different fiscal regimes: A panel analysis of the Euro Area. Journal of International Money and Finance, 156, 103341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W., Ahmad, I., Javed, A., & Rafiq, S. (2020). Regime switches in Pakistan’s fiscal policy: Markov-switching VAR approach. Applied Economics Journal, 27(2), 45–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajo-Rubio, O., Díaz-Roldán, C., & Esteve, V. (2014). Deficit sustainability, and monetary versus fiscal dominance: The case of Spain, 1850–2000. Journal of Policy Modeling, 36(5), 924–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F. (2012). Evolving monetary/fiscal policy mix in the United States. American Economic Review, 102(3), 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, H. (1998). The behavior of US public debt and deficits. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113(3), 949–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, H. (2007). Are stationarity and cointegration restrictions really necessary for the intertemporal budget constraint? Journal of Monetary Economics, 54(7), 1837–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancaccio, E., Fontana, G., Lopreite, M., & Realfonzo, R. (2015). Monetary policy rules and directions of causality: A test for the euro area. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 38(4), 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneau, C., & De Bandt, O. (2003). Monetary and fiscal policy in the transition to EMU: What do SVAR models tell us? Economic Modelling, 20(5), 959–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buiter, W. H. (2002). The fiscal theory of the price level: A critique. The Economic Journal, 112(481), 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canzoneri, M. B., Cumby, R., & Diba, B. (1998). Fiscal discipline and exchange rate regimes (CEPR Discussion Papers No. 1899). CEPR Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chibi, A., Chekouri, S. M., & Benbouziane, M. (2019). The dynamics of fiscal policy in Algeria: Sustainability and structural change. Journal of Economic Structures, 8(1), 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C. W. J., & Hacioglu Hoke, S. (2016). Macroeconomic tail events with non-linear Bayesian VARs. Bank of England. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane, J. H. (2001). Long-term debt and optimal policy in the fiscal theory of the price level. Econometrica, 69(1), 69–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, J. H. (2022). A fiscal theory of monetary policy with partially-repaid long-term debt. Review of Economic Dynamics, 45, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, R. B. (1987). Hypothesis testing when a nuisance parameter is present only under the alternative. Biometrika, 74(1), 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filardo, A. J. (1994). Business-cycle phases and their transitional dynamics. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 12(3), 299–308. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, J. M. (1962). Domestic financial policies under fixed and under floating exchange rates. Staff Papers-International Monetary Fund, 9(3), 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J. D. (1996). Specification testing in Markov-switching time-series models. Journal of Econometrics, 70(1), 127–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J. D. (2016). Macroeconomic regimes and regime shifts. In Handbook of macroeconomics (Vol. 2). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevđović, G., & Milenković, I. (2018). Monetary versus fiscal dominance in emerging European economies. Facta Universitatis, Series: Economics and Organization, 15(2), 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C. J. (1994). Dynamic linear models with Markov-switching. Journal of Econometrics, 60(1–2), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J. H., & Morita, H. (2013). Regime switches in Japanese fiscal policy: Markov-switching VAR approach. Hitotsubashi University. [Google Scholar]

- Komulainen, T., & Pirttilä, J. (2002). Fiscal explanations for inflation: Any evidence from transition economies? Economics of Planning, 35(3), 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krolzig, H. M. (1997). The Markov-switching vector autoregressive model. In Markov-switching vector autoregressions: Modelling, statistical inference, and application to business cycle analysis (pp. 6–28). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Leeper, E. M. (1991). Equilibria under ‘active’ and ‘passive’ monetary and fiscal policies. Journal of Monetary Economics, 27(1), 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeper, E. M., & Leith, C. (2016). Inflation through the lens of the fiscal theory. In Handbook of macroeconomics (Vol. 2). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Mackiewicz-Łyziak, J. (2015). Fiscal sustainability in CEE countries—The case of the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland. Equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics and Economic Policy, 10(2), 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogaji, P. K. (2023). Monetary-fiscal policy interactions in Africa: Fiscal dominance or monetary dominance? Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/120223/1/MPRA_paper_120223.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2026).

- Mongelli, F. P., & Wyplosz, C. (2009). The euro at ten: Unfulfilled threats and unexpected challenges. In The euro at ten: Lessons and challenges. European Central Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Mundell, R. A. (1963). Capital mobility and stabilization policy under fixed and flexible exchange rates. Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science/Revue Canadienne de Economiques et Science Politique, 29(4), 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novák, Z. (2019). Monetáris politika. Budapesti Műszaki és Gazdaságtudományi Egyetem, Gazdaság- és Társadalomtudományi Kar. [Google Scholar]

- Novák, Z., & Tatay, T. (2021). Captivated by liquidity—Theoretical traps and practical mazes. Public Finance Quarterly = Pénzügyi Szemle, 66(1), 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, R., & Sloek, T. (1998). The real effects of monetary policy in the European Union: What are the differences? Staff Papers, 45(2), 374–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, S., Kazinczy, E., & Tatay, T. (2025a). Comparing Post-Keynesian and New-Keynesian paradigms in monetary policy. Regional and Business Studies, 17(1), 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, S., Kazinczy, E., Tatay, T., & Amini, M. (2025b). Assessing fiscal and monetary policy coordination through a Nash equilibrium framework: The case of Hungary. In Central and eastern Europe between west and east: Economic, political, and cultural transformations in the 21st century (p. 47). Aposztróf Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Salimi, S., Kazinczy, E., Tatay, T., & Amini, M. (2025c). Evaluating fiscal and monetary policy coordination using a Nash equilibrium: A case study of Hungary. Mathematics, 13(9), 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargent, T. J., & Wallace, N. (1981). Some unpleasant monetarist arithmetic. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review, 5(3), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedegah, K., & Odhiambo, N. M. (2021). A review of the impact of external shocks on monetary policy effectiveness in non-WAEMU countries. Studia Universitatis Vasile Goldiș Arad, Seria Științe Economice, 31(3), 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvets, S. (2023). Dominance score in the fiscal-monetary interaction. National Accounting Review, 5(2), 186–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, C. A. (1994). A simple model for study of the determination of the price level and the interaction of monetary and fiscal policy. Economic Theory, 4(3), 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatay, T., & Novák, Z. (2025). Eurozone inflation in times of crises: An application of cluster analysis. Regional Statistics, 15(3), 579–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenovski, B., & Tashevska, B. (2015). Fiscal or monetary dominance in a small, open economy with fixed exchange rate—The case of the Republic of Macedonia. Proceedings of Rijeka Faculty of Economics: Journal of Economics and Business, 33(1), 125–145. [Google Scholar]

- Vonnák, B. (2005). Estimating the effect of Hungarian monetary policy within a structural VAR framework (No. 2005/1). MNB Working Papers. Magyar Nemzeti Bank. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.