Abstract

Emphasizing the existence of information asymmetries between, e.g., young academics and potential employers, signaling theory has shaped our understanding of how high-ability students try to document their superior skills in a competitive environment such as the labor market: high-ability individuals benefit from a relative cost advantage compared to low-ability individuals when producing a credible signal of superior ability. When this cost advantage decreases, the signal’s value also decreases. We analyze how the signal ‘international qualification’ has changed due to increasing overall student mobility, driven by the effect of a massive change in the institutional framework, namely the implementation of the Bologna reforms. Using a large and hitherto not accessible dataset with detailed information on 9096 German high-ability students, we find that following the Bologna reforms, high-ability students extended their stays and completed degrees abroad (instead of doing exchange semesters). No such changes in behavior are to be observed in the overall student population. We conclude that completing a degree abroad is the new labor market signal for the ‘international qualification’ of high-ability students.

1. Introduction

1.1. Labor Market Signaling

The labor market is traditionally characterized by information asymmetries between employers trying to recruit the most productive job candidates and job seekers competing for highly paid entry positions. According to Spence (1973), high-ability individuals will, therefore, produce a signal to distinguish themselves from low-ability individuals and thereby improve their labor market position. Each signal serves as an indicator for employers to identify individuals who are more productive and, thus, more attractive as potential future employees. However, a signal is credible if only high-ability individuals are willing to produce it while its production is too costly for low-ability individuals who will, therefore, refrain from investing in its production (Spence 1973).

Previous evidence has shown that with the general expansion of higher education (Schofer and Meyer 2005) signals, such as the completion of a tertiary degree, are no longer credible as their exclusiveness has disappeared. Hence, other signals, where high-ability individuals can still profit from their lower relative cost in producing it, became relevant. While Frick and Maihaus (2016) found internships in prestigious companies to be a credible labor market signal, others have identified international qualifications, i.e., an exchange semester abroad, as another relevant labor market signal (Messer and Wolter 2007; Relyea et al. 2008; Netz and Finger 2016).

However, just as higher education, in general, has lost its signaling effect due to its decreasing exclusiveness, the broad increase in international student mobility (e.g., in the form of exchange semesters) in recent years (Teichler 2012; DAAD and DZHW 2020) may have resulted in a similar effect. For European students, one reason for this increase in international mobility can be associated with the Bologna reforms.

1.2. Bologna Reforms

The Bologna reforms refer to an initiative by 29 European countries1 to form a coherent European Higher Education Area with harmonized structures. An according declaration was signed by the education ministers of the participating countries in 1999 at the University of Bologna. Concrete measures of the reforms were implemented in the respective countries’ education systems subsequently (European Commission 2021; EHEA 2020).

The ultimate goals of the reforms were to “facilitate student and staff mobility, to make higher education more inclusive and accessible, and to make higher education in Europe more attractive worldwide” (European Commission 2021). The measures taken to achieve these goals include a harmonized education system consisting of three separate yet consecutive tiers (Bachelor, Master, and doctoral studies) and the mutual recognition of study efforts completed abroad (European Commission 2021; EHEA 2020).

Looking at these changes in the institutional framework from a signaling perspective, we hypothesize that barriers to international student mobility have been lowered and, thus, the cost of producing the signal of international qualifications was dramatically reduced for all students. More specifically, there is now less room for high-ability students to distinguish themselves from the overall student population.

Thus, we hypothesize that utility-maximizing high-ability students will shift their attention to alternative forms of international qualifications that still allow them to produce a credible labor market signal. Since a signal is credible only if its production is costly, high-ability students must enjoy a cost advantage compared to low-ability students. As a consequence, we expect a change in the mobility behavior of high-ability students due to the increasing overall student mobility driven by the implementation of the Bologna reforms.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Signaling Theory

According to signaling theory, high-ability individuals are interested in distinguishing themselves from low-ability individuals via the production of a credible signal that demonstrates their superior abilities. The latter will typically refrain from investing in the same signal because the production costs are too high for them. This underlying negative correlation between an individual’s productivity and the cost of producing a signal makes signaling so relevant for employers who are typically seeking to recruit the most productive job candidates (c.f., Bills 2003; Spence 1973).

In the labor market, higher education is one such signal. By acquiring certain educational credentials, an individual can signal his/her abilities to prospective employers and increase his/her labor market prospects (c.f., Spence 1973; Löfgren et al. 2002). Recently, a number of empirical studies have demonstrated that specific higher education signals are, for example, an individual’s grades relative to the overall student population (Tyler et al. 2000), internships in particularly prestigious companies (Frick and Maihaus 2016), and study stays abroad or, in general, international qualifications (Messer and Wolter 2007; Relyea et al. 2008; Netz and Finger 2016).

2.2. Existing Evidence on the Consequences of Studying Abroad on Labor Market Outcomes

A labor market signal indicating international qualifications can take various forms such as, e.g., an exchange semester, a research visit at a university in another country, or an academic degree acquired abroad. Students who invest in the production of such signals should, therefore, have better labor market prospects in the sense that they find jobs with better advancement opportunities and/or receive higher starting salaries than their peers who refrain from producing one (or more) of these signals.

A large body of literature has shown the positive effects of studying abroad on graduates’ labor market prospects: Messer and Wolter (2007) surveyed 3586 Swiss university graduates and found indeed that participation in an exchange program is associated with higher starting salaries. Similarly, Kratz and Netz (2018) used panel data from two German graduate surveys (n1 = 2719 and n2 = 1511) and found that international student mobility is correlated with both steeper wage growth after graduation and higher medium-term wages, the latter being due to a higher probability of working in large multinational companies. Parey and Waldinger (2011) confirmed this pattern in their analysis that used survey results of n > 50,000 German university graduates from the years 1989, 1993, 1997, 2001, and 2005. They found that having studied abroad increases the probability of working in a foreign country by about 6–15 percentage points, depending on their model specifications. Using an experimental design, Petzold (2017) randomly sent out 231 applications with systematically varied CV information on having studied abroad and on professional work experience for internships offered by German employers. The most important result of this study is that having studied abroad has a significantly positive impact on, first, the response time of the respective employer and, second, the probability of receiving an invitation for a job interview, particularly from multinational firms.

Given these positive effects of an international qualification on a student’s labor market prospects, we expect that utility-maximizing individuals will be motivated to invest in a study stay abroad or other forms of international experience (c.f., Petzold and Moog 2018; Relyea et al. 2008; Tomlinson 2008; Netz and Finger 2016).

However, the existing evidence also shows that this motivation to study abroad differs between different groups of individuals, depending on their field of study. Especially business and economics majors are motivated to use a study abroad signal to improve their labor market prospects. Toncar et al. (2006) found that business students are particularly well aware of the potential signaling effects of having studied abroad, emphasizing that such an experience will improve their labor market prospects. This is not surprising as one can expect that business and economics majors are familiar with the underlying concept emphasizing the costs of producing a signal and its relevance for potential employers.

2.3. Recent Developments of International Student Mobility

However, with the general expansion of (higher) education (Schofer and Meyer 2005), traditional higher education signals, such as an exchange semester spent abroad, may no longer be credible when the number of individuals that are able to produce a particular signal increase due to, e.g., a change in the institutional environment, the relative cost advantage to produce that signal decreases for high-ability individuals. This, in turn, makes the signal less valuable (Spence 1973). This is what happened to the signal “international qualification” in terms of spending one or two semesters at a university abroad2. Teichler (2012, p. 34), in his comprehensive analysis of international student mobility in the context of the Bologna reforms, concludes that the “value of student mobility gradually declines as a consequence of gradual loss of exclusiveness”.

With the changes in the institutional framework for studying abroad, i.e., the implementation of the Bologna reforms, the cost of studying abroad decreased for all students. As a consequence, more students are now able to go abroad, and the exclusiveness of the previously highly appreciated signal of international qualification decreases. The costs of studying abroad can be monetary, e.g., travel costs or higher costs of living abroad, and non-monetary, e.g., language barriers or efforts to organize a stay abroad and integrate it into the home university’s program (c.f., Petzold and Moog 2018; Doyle et al. 2010; Presley et al. 2010). Typically, high-ability students have an advantage relative to their low-ability peers with respect to the monetary as well as the non-monetary costs of studying abroad. First, they are more likely to obtain a scholarship based on their superior academic performance, and second, they are better able to organize a study stay abroad (c.f., Petzold and Moog 2018; Lörz et al. 2016). If these monetary and non-monetary obstacles are reduced by a massive change in the institutional environment, the relative cost advantage of high-ability students decreases and overall international student mobility increases, making a study stay abroad a less valuable labor market signal.

With the implementation of the European Higher Education Act (“Bologna-reforms”), the monetary as well as non-monetary costs of going abroad were reduced for all students. One explicit goal of the Bologna reforms was to foster international student mobility in an integrated higher education landscape. Specifically, the Bologna reforms stipulated the mutual recognition of academic credits and performances from foreign universities and the introduction of a comparable Bachelor-/Master-/PhD-system of academic degrees (EHEA 2020; European Commission 2021). As a consequence, especially the non-monetary costs of studying abroad decreased since (most of) the organizational barriers were removed. Additionally, the monetary cost obstacles declined with, e.g., financially supported exchange programs for students being established between universities in the participating countries.

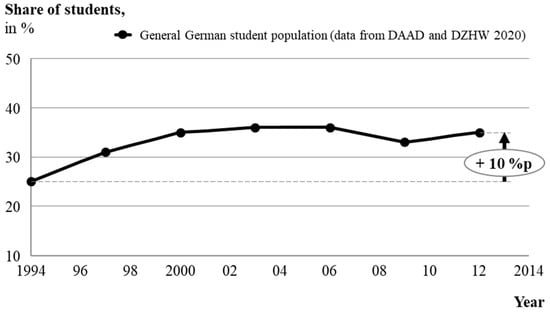

With these changes in the institutional framework, the costs of study stays abroad declined for all students. As a result, a steep increase in the international mobility of German students in the last two decades (see Figure 1) can be observed. Today, more than one-third of all German students in later semesters have spent a part of their time at university abroad (BMBF and KMK 2018).

Figure 1.

Development of German students in later semesters with study-related visits abroad (data from DAAD and DZHW (2020)).

Given these developments, we conclude that a ‘simple’ study stay abroad in the form of an exchange semester has become less exclusive and can, therefore, no longer be considered a credible signal of high-ability students to indicate their superior productivity. High-ability students wishing to distinguish themselves from low-ability students (following the paradigm of rational and utility-maximizing individuals) will, therefore, choose other signals of international qualification that low-ability students will not be able to produce at the same cost. As a consequence, we expect a change in the behavior of high-ability students towards signals where they still have a relative cost advantage over the general student population.

3. Methods and Data

3.1. Framework for the Analysis of International Student Mobility

We analyze the behavior of high-ability student mobility using the conceptual framework developed by Netz (2015). This framework distinguishes between (1) a pre-decision stage, (2) a planning stage, and (3) a post-realization stage. Between stages (1) and (2) is the decision threshold (whether to study abroad) and between (2) and (3) is the realization threshold (where and how to study abroad) (Netz 2015).

Our analyses are structured along this framework: First, we analyze the behavior of high-ability students at the decision threshold—whether they go abroad at all depending on the institutional framework while controlling for socio-demographics. The institutional framework is specified via the degree system: Diploma (Non-Bologna framework) vs. Bachelor/Master (Bologna framework). We estimate the impact of the Bologna system on the decision to go abroad (or not) using a Probit model. Potential interaction effects between the field of study and the change in the degree system are modelled via separate dummy variables. We then use post-estimation Wald-Tests to check for differences in the significance of the coefficients of the respective dummy variables. Second, we use Propensity score matching to isolate the effect of the degree system as follows: We match Bologna and Non-Bologna students based on their gender, age at study start, Abitur grade3 cluster, field of study, and year of study start. Thus, we measure the average treatment effect of the change in the institutional framework (identified via the degree system) and the resulting lower costs to go abroad under the Bologna system. This allows us to isolate the effect of the change in the degree system from the influence of socio-demographic characteristics as well as other time-variant external factors.

In a further step, we look at the particular realization of the studies abroad for those students who went abroad, that is, for those who passed the decision threshold. Again, we use a Probit model plus Propensity score matching to analyze a possible change in behavior in the realization of studies abroad with respect to the number of stays per student, the cumulative duration of stays per student, the duration per stay, and the likelihood of completing one or more degrees abroad.4

Thus, we first looked if the students went abroad (decision threshold), then second at the particular realization of the sub-sample of students who went abroad in terms of the number of stays, duration, degrees, etc.

3.2. Dataset

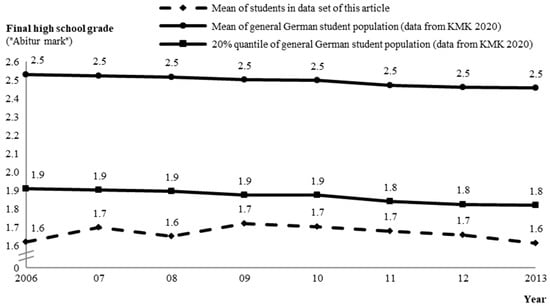

Our dataset was extracted from the database hosted by a large German scholarship institution5. This database comprises anonymous CV information of the scholars over a period of 20 years since the organization’s foundation. Scholarships are offered to pupils who ranked among the Top 3 in the respective Abitur (=high school diploma) cohort at their high school. Furthermore, unsolicited applications from students are possible. Key criteria for the selection of scholars are excellent academic performance, outstanding practical experience (e.g., via internships), and extracurricular engagement. Comparing the mean high school grade of the scholars in our sample with the general German student population6 (Figure 2), it appears that the students in our dataset are indeed performing much better than their peers and are constantly better than the top 20% of the overall German student population. Hence, we refer to the students in our dataset as “high-ability” students.

Figure 2.

Comparison of mean final high school grades (data for general German student population from (KMK 2020)).

From the original database, we extracted a dataset with detailed information on 10,844 German scholars with a study start between 1994 and 2013. We explicitly checked whether each student had completed his/her studies. We selected the three main fields of study in the database with 4764 students from Business & Economics, 2435 from Engineering, and 1897 from Natural Sciences & Mathematics. Hence, the final dataset used in our analyses included 9096 students.

3.3. Differentiation of Bologna and Non-Bologna Students and Destinations

Germany signed the Bologna declaration in 1999 with the aim to implement the respective initiatives, e.g., the Bachelor/Master degree system until 2010 (BFUG 2020). Thus, our dataset includes both pre- and post-Bologna students, i.e., students studying under the Diploma and the Bachelor/Master degree system.

Both students and study abroad destinations were differentiated accordingly: Students were categorized based on the degree they obtained into Bologna (Bachelor/Master degree system) vs. Non-Bologna students (Diploma-system). In this sense, Bologna students represent the treatment group and Non-Bologna students the control group for our statistical analyses.

Bologna destinations are defined as higher education institutions in one of the 48 member countries of the European Higher Education Area (this is, countries participating in the Bologna reforms) according to BFUG (2020), except for universities in Germany as the home country of the students in our dataset. Higher education institutions in other countries are defined as Non-Bologna destinations.

Table 1 presents an overview of the key variables and descriptive statistics of the dataset. In some of the more detailed analyses, we further distinguish by field of study (Business & Economics vs. Engineering vs. Natural Sciences & Mathematics) and destination of study abroad, i.e., Bologna vs. Non-Bologna destinations.

Table 1.

Overview of main variables and descriptive statistics.

4. Findings

As already mentioned above, we analyze the mobility patterns of high-ability students using the framework developed by Netz (2015); that is, we look at the behavior at the decision and the realization thresholds. At the decision threshold, we find a development in the going abroad behavior that is in line with the trend in the general student population. In particular, we see an increase in the mobility of high-ability students of 12–15 percentage points as a result of the implementation of the Bologna reforms, similar to the overall student population, where an increase of 10 percentage points is to be observed (Figure 1).

However, when looking at the realization of the study stay abroad, we observe a highly interesting, yet not surprising, change in behavior: We find a significant effect of the change in the degree system on the “degree mobility” of high-ability students.

4.1. Decision Threshold

Table 2 displays the results of two Probit models (D1 and D2) identifying the effect of the change in the institutional framework for going abroad following the Bologna reforms. We estimate the probability of going abroad during one’s time at university depending on the degree system while controlling for socio-demographic characteristics as well as other education-related factors. In model D2, we additionally control possible interaction effects between the degree system and the field of study using six different dummy variables representing different combinations of the field of study and degree system.

Table 2.

Statistical models D1 and D2 at decision threshold for stay abroad.

Overall, we find intuitively plausible effects of both the socio-demographic characteristics and the education-related factors. In model D1, we find a statistically significant effect for the field of study. Compared to Business & Economics students, Engineering and Natural Sciences & Mathematics majors are, other things equal, 21–25 percentage points less likely to go abroad during their course of study. Gender does not have a significant effect in either of the two models, suggesting that male and female students are equally likely to go abroad. The coefficients of the four final high school grade clusters are statistically significant only for clusters 3 and 4, suggesting that students with poorer high school grades are less likely to go abroad during their time at university.

According to model D1, the change in the degree system increased the individuals’ probability of going abroad by about 4 percentage points. The coefficients of the interactions between the change in the degree system change and the different fields of study (model D2) suggest that the effect is of a similar magnitude for all majors. Post-estimation Wald-tests reveal that the effect of the change in the degree system is statistically significant only for Business & Economics and Engineering students (p < 0.05) but not for students majoring in Natural Sciences & Mathematics.

To further isolate the effect of the change in the degree system, we applied Propensity Score Matching in model D3, the results of which are displayed in Table 3. This model confirms our initial observation, revealing a large and statistically significant effect. Under the Bologna system, high-ability students are 15 percentage points more likely to spend some time at a foreign university.

Table 3.

Statistical model D3 at decision-threshold for stay abroad.

Summarizing, these models suggest an increase in overall international mobility for high-ability students studying under the Bologna system of 4–15 percentage points (depending on the model specification). This figure is of the same magnitude as in the general student population (+10 percentage points between 1994 and 2012; see Figure 1 above).

However, more detailed analyses show that this is true for Business & Economics and Engineering students only, while it does not hold true for Natural Sciences & Mathematics majors. In this latter group of high-ability students, no change in behavior occurred due to the implementation of the Bologna reforms. We discuss this finding in more detail below.

To analyze other changes in behavior, a more detailed view needs to be taken at the specific realization of studying abroad. Therefore, we now proceed to analyze the behavior at the realization threshold.

4.2. Realization Threshold

4.2.1. Overview

As outlined above, different characteristics of the stay abroad were used to identify changes in the behavior of high-ability students at the realization threshold. Our key finding here is a significant increase in degree mobility (Table 4; for further analyses, see Appendix A). We find a strong and statistically significant effect of the Bologna system on degree mobility, that is, the probability of completing a stay abroad of at least 12 months. Our other findings with respect to changes in the behavior of high-ability students when going abroad are in line with this finding: Under the new regime, the stays abroad are longer, and the number of stays has increased (the respective estimation results can be found in Appendix A).

Table 4.

Statistical models R1 at realization threshold for stay abroad.

Table 4 presents the results of our Propensity score matching model R1 showing the average treatment effect (ATE) of the change in the degree system (i.e., studying in the Bologna regime) on degree mobility, i.e., the likelihood of completing a degree abroad by destination. We distinguish between Bologna and Non-Bologna destinations since the costs of going abroad, driven by the change in the institutional framework, are lower only in destinations participating in the Bologna reforms. Following the threshold logic developed by Netz (2015), we only consider students who have already passed the decision threshold and went abroad.

It appears from model R1 (Table 4) that degree mobility in Bologna destinations increased by 23 percentage points due to the change in the degree system. In contrast, no such change is to be found in Non-Bologna destinations.

4.2.2. Influence of Education Related Characteristics

In the next step, we again take a more nuanced perspective on the degree mobility of the students in our dataset. We now estimate two Probit models, including interaction effects between the change in the degree system and the field of study. Table 5 below displays the results.

Table 5.

Statistical models R2 & R3 at realization-threshold for stay abroad.

Interestingly, the findings regarding the effect of the change in the degree system vary considerably between the different fields of study and the two destinations. Model R2 suggests that the effect of the change in the degree system on degree mobility into Bologna destinations is statistically significant for Business & Economics (+20 percentage points) and for Natural Sciences & Mathematics students (+15 percentage points). For Engineering students, we do not find a significant effect. Post-estimation Wald-tests confirm the significance of the degree system effect in these two fields of study (p < 0.001). In model R3, we observe a similar pattern across the fields of study. With respect to the degree of mobility of Business & Economics students into Non-Bologna destinations, the model displays an effect of +7 percentage points (post-estimation via Wald-test confirms significance, p < 0.01), while for Natural Sciences & Mathematics students, the Probit model also suggests a positive effect. Here, however, post-estimation via Wald-test shows this effect to be insignificant.

In total, this more nuanced perspective reveals that a statistically significant increase in degree mobility induced by the Bologna reforms can be observed only among Business & Economics students and for Natural Sciences & Mathematics students (for the latter only for Bologna destination). This pattern suggests that high-ability Business & Economics students are more likely to invest in the production of credible signals since they are, by education, familiar with the underlying concept. Thus, compared to their fellow students from other fields, they are more likely to complete a degree abroad to distinguish themselves from other Business & Economics students and signal their superior productivity to the labor market. Producing such a signal is more relevant for Business & Economics students since especially the more able and talented ones are typically looking for jobs offered by globally active multinational corporations. The same applies to high-ability Natural Sciences & Mathematics students looking for career opportunities in research, where an international qualification is also a relevant signal. In contrast, German high-ability Engineering students find an attractive labor market in their home country. For them, investing in the costly production of the signal “international qualification” is not that relevant and may even be detrimental to their labor market prospects if potential employers prefer practical experience accumulated via extended internships in prestigious companies, e.g., the German engineering or automotive industry.

The effects of the final high school grade on the probability of completing a degree program abroad are as expected for both destinations. Students with poorer final high school grades are less likely to complete a degree abroad. However, for Non-Bologna destinations, this effect is statistically significant only for the worst cluster of students. With respect to the Bologna destinations, all the coefficients fail to reach conventional levels of statistical significance.

4.2.3. Influence of Socio-Demographic Factors

Models R2 and R3 (see Table 5) show that gender seems to play a minor role only for degree mobility into Non-Bologna destinations. The female high-ability students in our dataset are 4 percentage points less likely to complete a degree in Non-Bologna destinations. For Bologna destinations, we fail to find a statistically significant gender effect, suggesting that male and female students are equally likely to complete a full degree program abroad.

Finally, the effect of the students’ age at study start is statistically significant and plausible. With each additional year of age, the probability of completing a degree abroad decreases by 1–2 percentage points. Thus, older students are less likely to complete a degree abroad.

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion of Theoretical Context

Our results clearly suggest that high-ability students use a degree abroad as the new labor market signal for an “international qualification” to distinguish themselves from low-ability students, for whom the respective monetary as well as non-monetary costs are higher. We suggest two main drivers for this development:

First, the costs of studying abroad have recently declined for all students due to changes in the institutional framework (i.e., the implementation of the Bologna reforms). As a result, the relative cost advantage of high-ability students compared to their fellow low-ability students decreased since international student mobility has increased considerably, and an exchange semester or study stay abroad has lost its exclusiveness (Teichler 2012). Thus, a “simple” study stay abroad, e.g., in the form of an exchange semester, is no longer a credible labor market signal.

Second, the changes in the institutional framework have opened up new opportunities for high-ability students to produce other signals where they still benefit from a relative cost advantage. Specifically, with the change towards the BSc/MSc/PhD degree system, an international degree is now fully recognized in the high-ability students’ home country (here, Germany). More importantly, completing a degree abroad in a foreign language is arguably less costly for high-ability than for low-ability students for a number of reasons. First, high-ability students are more likely to access a full degree program abroad. Second, high-ability students are arguably better able to adapt quickly to new circumstances and to deal with language- and study-related challenges. Third, due to their performance, they are more likely to receive scholarships to fund their stay abroad, which is arguably more expensive than doing only an exchange semester. Fourth, in order to successfully complete a full degree program abroad, students must comply with a pre-defined course program. This means they have little (if any) freedom to choose ”easy” courses, which a student who, in contrast, “just” does an exchange semester is likely to do. This is where the relative cost advantage of high-ability students in completing a degree abroad materializes. Since they are not able to avoid courses that are considered “difficult” by most students, such as, e.g., (advanced) mathematics and/or econometrics in a business program, they can convincingly document their intellectual superiority as well as their academic stamina.

Admittedly, the human capital theory could also serve as an explanation for the identified increase in the degree of mobility of high-ability students. For example, opportunities to acquire a foreign language and/or intercultural skills are certainly drivers for the motivation to study abroad (Doyle et al. 2010). However, isolating the relative contributions of signaling vs. human capital theory to explain the wide range of education and labor market phenomena is typically rather difficult (Weiss 1995; Huntington-Klein 2021). In the present case, we consider signaling theory to explain the observable development of international student mobility better for a number of reasons. Completing a degree abroad will certainly lead to some increase in human capital and, thus, improve labor market prospects. This, in turn, could be an incentive for high-ability students to complete a degree abroad—independent of the overall increase in international student mobility. However, in our context, the incremental increase in an individual’s human capital, i.e., his/her abilities and skills, resulting from international experience, is likely to differ considerably between high- and low-ability students. The former will benefit far more from the signaling effect of a degree abroad as a means to distinguish themselves from their fellow students than low-ability students will benefit from a “simple” semester abroad as this is no longer considered a credible signal of international qualification. Thus, for high-ability students, we estimate the relative contribution of signaling to the motivation to complete a degree abroad to be higher than the contribution of an increase in the respective individual’s human capital.

5.2. Differentiation of Findings by Field of Study

Our findings show a statistically significant effect of a change in the degree system on international student mobility between 1994 and 2013 of 15–23 percentage points, depending on the subsample and the particular model specification. When distinguishing between different fields of study, we find this effect to be particularly strong for Business & Economics students while being significant for Natural Sciences & Mathematics students only for Bologna destinations. Among Engineering students, the reforms did not have any effect on international mobility, neither into Bologna nor Non-Bologna destinations. These results are interesting and as expected: On the one hand, Business & Economics students are well aware of the underlying concepts of signaling and screening in the labor market. Hence, they are more likely to “apply” signaling consciously to maximize the value of each study decision they have taken. Consequently, they fully understand that completing a degree abroad is far more valuable for their labor market prospects than “just” completing an exchange semester abroad.

On the other hand, signals of international qualification are more relevant for multinational companies (Petzold 2017). Assuming that high-ability Business & Economics students are attracted by the career prospects in multinational companies, signaling an international qualification is, in turn, particularly relevant for them (see also Toncar et al. 2006). The same applies to Natural Sciences & Mathematics students looking for a career in international research institutions. In contrast, the potential employers of German Engineering students typically place a much lower value on an international qualification but look primarily at the individuals’ performance in one of the arguably renowned German Engineering programs. Thus, high-ability German Engineering students find a highly attractive labor market in their home country and, therefore, do not need to invest in an international qualification.

5.3. Contextualization with Trends in Overall Student Mobility

To put this increase in the degree mobility of high-ability students into perspective, we compared this increase with respective data of the overall student population. To the best of our knowledge, no such increase can be found here: According to the European Tertiary Education Register (ETER), funded by the European Commission, the share of students completing a degree in another EU country has increased only marginally between 2011 and 2013 by 0.2 percentage points (European Commission 2020)9. Although these figures are not exactly comparable, the difference between the small increase in degree mobility in the general student population and the large increase among high-ability students in our dataset leads us to the following conclusion:

An exchange semester or a short-term study stay abroad has lost its credibility as a labor market signal as a result of an increase in overall international student mobility driven by the implementation of the Bologna reforms. Thus, high-ability students, particularly from Business & Economics and Natural Sciences & Mathematics, turned to completing a degree abroad as their new labor market signal demonstrating to potential employers their superior abilities and helping them to distinguish themselves from low-ability students.

Admittedly, our results would be even more convincing if we had access to comparable data from other countries, yielding similar results to the ones we have presented here. To the best of our knowledge, such data are currently not available. To partially compensate for this deficit, future research should focus on analyzing the mobility behavior of low-ability students and particularly their interest in completing a degree abroad. Moreover, future research should also analyze the returns to the labor market signal “international degree” by, e.g., looking at its impact on starting salaries and entry positions since these dimensions perfectly reflect how employers value the signal.

6. Conclusions

In summary, we confirm our initial hypothesis derived from signaling theory that utility-maximizing high-ability students will shift their attention from going abroad for one semester to alternative forms of international qualification as a credible labor market signal. Due to the increase in international student mobility induced by the Bologna reforms, the traditional signal of international qualification—a study abroad semester—has completely lost its exclusiveness as a labor market signal. We now find strong evidence that completing a degree program abroad is the new labor market signal for international qualification for high-ability students, particularly from the field of Business & Economics. Thus, in line with signaling theory, our data shows that with the implementation of the Bologna reforms, high-ability students complete academic degree programs abroad more often, while we fail to find any evidence for the same trend in the overall student population. Our interpretation that a degree program completed at a university abroad can be considered a credible labor market signal rests on the plausible assumption that while the Bologna reforms reduced the costs of studying abroad for all students, they did not affect the relative cost advantage of high-ability students to complete a full degree program abroad. In order to successfully complete a degree program abroad, the individuals’ intellectual abilities and academic stamina are likely to play a far more important role than the institutional framework. The Bologna reforms have increased the probability of spending a semester abroad not only for high- but also for low-ability students, with the former changing their behavior even more than the latter. This, in turn, suggests that the non-monetary, e.g., mental costs of going abroad, continue to be more important than the monetary costs, which are now much lower than they used to be in the pre-Bologna era.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.F. methodology, L.B.-W. and F.L. formal analysis, L.B.-W. and F.L. data curation, L.B.-W. and F.L. writing—original draft preparation, B.F. writing—review and editing, B.F. supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data is proprietary and cannot be made accessible to other researchers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Further statistical models at realization threshold for stay abroad.

Table A1.

Further statistical models at realization threshold for stay abroad.

| Variable | Model R4 | Model R5 | Model R6 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Propensity Score Matching | Propensity Score Matching | Propensity Score Matching | |||||

| Dependent variable | Stay abroad (yes/no) in… | Number of stays in… | Cumulative duration of stay in… | ||||

| Bologna destinations | Non-Bologna destinations | Bologna destinations | Non-Bologna destinations | Bologna destinations | Non-Bologna destinations | ||

| Average treatment effect (ATE) | Degree system Bologna | −0.05 (0.07) | 0.14 (0.07) * | 0.18 (0.08) * | 0.15 (0.04) ** | 10.26 (2.04) ** | 3.58 (2.04) |

| Matching variables | Gender, Age at study start, Final high school grade cluster, Field of study, Year of study start | ||||||

| Sub-sample condition | ≥1 stay abroad | ≥1 stay abroad | ≥1 stay in Bologna destinations | ≥1 stay in Non-Bologna destinations | ≥1 stay in Bologna destinations | ≥1 stay in Non-Bologna destinations | |

| Number of observations | 6029 | 6029 | 3976 | 3095 | 3976 | 3095 | |

| Number of matchings [min; max] | 1; 34 | 1; 34 | 1; 27 | 1; 16 | 1; 27 | 1; 16 | |

Legend: * denotes significance at 5%, ** at 0.1%; robust standard errors in parentheses.

Table A2.

Further statistical models at realization threshold for stay abroad.

Table A2.

Further statistical models at realization threshold for stay abroad.

| Variable | Model R7 | Model R8 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Propensity Score Matching | Propensity Score Matching | ||||

| Dependent variable | Share of stays abroad of a student’s total study duration for abroad stays in… | Duration per stay abroad in… | |||

| Bologna destinations | Non-Bologna destinations | Bologna destinations | Non-Bologna destinations | ||

| Average treatment effect (ATE) | Degree system Bologna | 0.10 (0.02) * | 0.03 (0.02) | 4.41 (0.96) * | 1.43 (1.57) |

| Matching variables | Gender, Age at study start, Final high school grade cluster, Field of study, Year of study start | ||||

| Sub-sample condition | ≥1 stay in Bologna destinations | ≥1 stay in Non-Bologna destinations | ≥1 stay in Bologna destinations | ≥1 stay in Non-Bologna destinations | |

| Number of observations | 3976 | 3095 | 3976 | 3095 | |

| Number of matchings [min; max] | 1; 27 | 1; 16 | 1; 27 | 1; 16 | |

Legend: * denotes significance at 0.1%; robust standard errors in parentheses.

Notes

| 1 | More countries joined the reforms later on. |

| 2 | In this article, we define “studies abroad” as one or more study stays abroad or the completion of a tertiary degree in a foreign country. |

| 3 | The Abitur is the final qualification in secondary education in Germany. The overall performance of a student in secondary education is expressed by his/her final Abitur grade. |

| 4 | We also checked whether high-ability students chose stays at top universities worldwide more often as an alternative signal. Therefore, we calculated the share of students who completed a stay abroad at a top university defined as those ranked between 2010 and 2020 among the top 25 universities worldwide according to the Times Higher Education World ranking (Times Higher Education 2020). However, the share of students in our data set attending one of the top universities remains constant over time. |

| 5 | The data are proprietary and cannot be made available to other researchers. |

| 6 | Official statistics of the Conference of German Cultural Ministers (KMK) are only available back to 2006. |

| 7 | For subsequent analyses categorized into clusters within the data set ([1.0; 1.19], [1.2; 1.39], [1.4; 1.69]. [1.7; 4]). |

| 8 | Total study duration = total time at university (abroad + in home country). |

| 9 | Degree mobility figures for the overall European student population were calculated based on ETER data (Available online: European Commission 2020) on resident and mobile students at ISCED levels 6 & 7 (this is, Bachelor- & Master-level) and according to the formula employed by Sánchez Barrioluengo and Flisi (2017, p. 12): Share of degree mobile students = ((number of mobile students)/(number of mobile students + number of resident students)). |

References

- BFUG. 2020. Full Members of the European Higher Education Act (EHEA). Bologna Follow-Up Group Secretariat. Available online: http://www.ehea.info/page-full_members (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Bills, David B. 2003. Credentials, Signals, and Screens: Explaining the Relationship between Schooling and Job Assignment. Review of Educational Research 73: 441–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BMBF and KMK. 2018. Die Umsetzung der Ziele des Bologna-Prozesses 2015–2018. Nationaler Bericht von Kultusministerkonferenz und Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung unter Mitwirkung von HRK, DAAD, Akkreditierungsrat, fzs, DSW und Sozialpartnern. Federal Ministry of Education and Research Germany (BMBF) and The Conference of German Cultural Ministers (KMK). Available online: https://www.bmbf.de/de/der-bologna-prozess-die-europaeische-studienreform-1038.html (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- DAAD and DZHW. 2020. Wissenschaft weltoffen 2020 kompakt. English Edition. Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD) and Deutsches Zentrum für Hochschul- und Wissenschaftsforschung (DZHW). Available online: http://www.wissenschaftweltoffen.de/kompakt/wwo2020_kompakt_en.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Doyle, Stephanie, Philip Gendall, Luanna H. Meyer, Janet Hoek, Carolyn Tait, Lynanne McKenzie, and Avatar Loorparg. 2010. An Investigation of Factors Associated With Student Participation in Study Abroad. Journal of Studies in International Education 14: 471–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EHEA. 2020. Website of the European Higher Edcuation Area. Bologna Process Secretariat. Available online: http://www.ehea.info/ (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- European Commission. 2020. ETER Database. European Tertiary Education Register. Available online: https://www.eter-project.com/#/search (accessed on 3 November 2020).

- European Commission. 2021. The Bologna Process and the European Higher Education Area. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/education/policies/higher-education/bologna-process-and-european-higher-education-area_en (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Frick, Bernd, and Michael Maihaus. 2016. The (ir-)relevance of internships. Signaling, screening, and selection in the labor market for university graduates. Business Administration Review 76: 377–88. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington-Klein, Nick. 2021. Human capital versus signaling is empirically unresolvable. Empirical Economics 60: 2499–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KMK. 2020. Schulstatistik. Abiturnoten im Ländervergleich. The Conference of German Cultural Ministers (KMK). Available online: https://www.kmk.org/dokumentation-statistik/statistik/schulstatistik/abiturnoten.html (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Kratz, Fabian, and Nicolai Netz. 2018. Which mechanisms explain monetary returns to international student mobility? Studies in Higher Education 43: 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löfgren, Karl-Gustaf, Torsten Persson, and Jörgen W. Weibull. 2002. Markets with Asymmetric Information: The Contributions of George Akerlof, Michael Spence and Joseph Stiglitz. Scandinavian Journal of Economics 104: 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lörz, Markus, Nicolai Netz, and Heiko Quast. 2016. Why do students from underprivileged families less often intend to study abroad? Higher Education 72: 153–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messer, Dolores, and Stefan C. Wolter. 2007. Are student exchange programs worth it? Higher Education 54: 647–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netz, Nicolai, and Claudia Finger. 2016. New Horizontal Inequalities in German Higher Education? Social Selectivity of Studying Abroad between 1991 and 2012. Sociology of Education 89: 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netz, Nicolai. 2015. What Deters Students from Studying Abroad? Evidence from Four European Countries and Its Implications for Higher Education Policy. Higher Education Policy 28: 151–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parey, Matthias, and Fabian Waldinger. 2011. Studying Abroad and the Effect on International Labour Market Mobility: Evidence from the Introduction of ERASMUS. The Economic Journal 121: 194–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzold, Knut, and Petra Moog. 2018. What shapes the intention to study abroad? An experimental approach. Higher Education 75: 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzold, Knut. 2017. Studying Abroad as a Sorting Criterion in the Recruitment Process: A Field Experiment Among German Employers. Journal of Studies in International Education 21: 412–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presley, Adrien, Datha Damron-Martinez, and Lin Zhang. 2010. A Study of Business Student Choice to Study Abroad: A Test of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Journal of Teaching in International Business 21: 227–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relyea, Clint, Faye K. Cocchiara, and Nareatha L. Studdard. 2008. The Effect of Perceived Value in the Decision to Participate in Study Abroad Programs. Journal of Teaching in International Business 19: 346–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Barrioluengo, Mabel, and Sara Flisi. 2017. Student Mobility in Tertiary Education: Institutional Factors and Regional Attractiveness. (JRC Science for Policy Report). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Schofer, Evan, and John W. Meyer. 2005. The Worldwide Expansion of Higher Education in the Twentieth Century. American Sociology Review 70: 898–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, Michael. 1973. Job Market Signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 87: 355–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichler, Ulrich. 2012. International Student Mobility in Europe in the Context of the Bologna Process. Research in Comparative and International Education 7: 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Times Higher Education. 2020. The World Ranking. Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/2021/world-ranking#!/page/0/length/25/sort_by/rank/sort_order/asc/cols/stats (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Tomlinson, Michael. 2008. ‘The degree is not enough’: Students’ perceptions of the role of higher education credentials for graduate work and employability. British Journal of Sociology of Education 29: 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toncar, Mark F., Jane S. Reid, and Cynthia E. Anderson. 2006. Perceptions and Preferences of Study Abroad. Journal of Teaching in International Business 17: 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, John H., Richard J. Murnane, and John B. Willett. 2000. Estimating the Labor Market Signaling Value of the GED. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 115: 431–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, Andrew. 1995. Human Capital vs. Signalling Explanations of Wages. Journal of Economic Perspectives 9: 133–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).