Abstract

The quality of sustainability reporting (SR) has come to be widely regarded as a factor of considerable importance in influencing organisational performance. However, empirical evidence in relation to SR has been characterised by fragmentation across industrial sectors. The purpose of this study was to synthesise the relationship between SR and organisational performance across the manufacturing, finance, energy and utilities, services, and ICT sectors. Our systematic review, performed using the PRISMA 2020 framework and machine learning meta-regression, was conducted on 372 studies retrieved from the Scopus database between 1 January 2020 and 1 November 2025. Our pooled correlation showed that the SR effect was positively associated with outcome performance (r = 0.231, 95% CI [0.184, 0.279]) and yielded a standardised mean difference (g = 0.426, 95% CI [0.341, 0.512]). The meta-regression showed that assurance quality (β = 0.156, p < 0.001), the regulatory regime (β = 0.142, p < 0.001), and reporting standard alignment (β = 0.118, p = 0.003) are significant moderating factors. The predictive robustness was confirmed through cross-validation (R2 = 0.55; RMSE = 0.056), while feature stability was substantiated by a mean SHAP variance of less than 0.012. Transparency, comparability, and decision usefulness in SR were found to be enhanced by institutional mechanisms—particularly those providing credible assurance within mandatory regulatory frameworks.

1. Introduction

SR has been transformed from its conventional form into a framework whereby ESG performance is systematically integrated within organisational strategy [1]. SR has been reconceptualised as a technologically mediated disclosure framework, shaped by global regulatory evolution and digital transformation. SR, originally conceived as a voluntary and descriptive practice, has been progressively institutionalised through codified standards. Milestones such as the GRI, the SASB, and the TCFD have been instrumental in establishing widely accepted cross-sectoral transparency norms [2]. SR has been embedded within intelligent data ecosystems by these frameworks, enabling automation, analytics, and assurance. It has now been positioned as both a regulatory mechanism and an informational infrastructure that interconnects firms, technologies, and stakeholders in the collective pursuit of sustainable development objectives.

In the post-2020 period, an increasing association between SR and AI-driven governance and data assurance systems has been observed. This linkage was construed as indicative of an enlarged function within infrastructures for digital sustainability. Credibility has been increasingly defined by data quality, verification, comparability, and stakeholder accountability [3]. Automated data collection, anomaly detection, and risk-based monitoring have been enabled by emerging intelligent systems. Through these mechanisms, the reliability of SR has been strengthened, and public trust has been reinforced. Disparities in assurance quality, regulatory enforcement, and technological adoption have been identified as sources of enduring inconsistency across industries [4]. Such inconsistencies have been identified as undermining factors. Equity and accountability in sustainability governance are compromised through asymmetry, algorithmic bias, and unequal digital capacity [5].

The relationship between the quality of SR and organisational outcomes has been interpreted through legitimacy, stakeholder, signalling, and institutional perspectives [6,7,8]. Within this framework, it was explained how sustainability aligns with societal expectations and contributes to the preservation of the organisational social contract. Stakeholder theory has been interpreted as framing SR in terms of a response to varied accountability expectations. Within signalling theory, disclosures are regarded as representations of governance robustness and strategic foresight. Institutional theory is understood as attributing divergence to regulatory and normative forces that mould corporate conduct [9]. Whilst the conceptual integrity of these frameworks has been maintained, their assessment has been undertaken primarily through independent evaluation. SR has been established as a cornerstone of contemporary corporate communication practices, measurement systems, implementation strategies, and overall practice across both the public and private sectors.

Numerous empirical advances in SR have been achieved through the progressive development of indices across both public and private organisations [10]. The credibility and comparability of disclosed data have been strengthened through the application of frameworks such as the GRI and the SASB [11]. The progressive institutionalisation of sustainability metrics has been catalysed by the systematic linking of ESG domains to corporate accountability [12]. Some methodological refinements have been measured through the adoption of integrated reporting models and stakeholder inclusivity. Empirical evidence has been strengthened through the expansion of reporting boundaries. However, the validation of sustainability constructs remains unresolved in cross-sector settings [13].

However, the limitations of existing standards have been increasingly acknowledged across regional contexts, theoretical frameworks, methodological approaches, and index indicators [14,15]. Machine learning meta-regression approaches, while statistically robust, have been constrained in testing cross-regional interdependence. The complexity has been intensified by the rapid emergence of AI-based SR frameworks, through which earlier syntheses have been rendered suitable for cross-regional analysis. A limited number of reviews have been conducted with cross-regional depth analyses of SR between the public and private sectors. Studies are needed that apply machine learning meta-regression modelling and interpretability to identify latent moderators within the heterogeneous effects of SR across sectors and regions [16].

The purpose of this study was to synthesise the relationship between SR and organisational performance across the manufacturing, financial services, energy and utilities, ICT, and services sectors. The objectives were threefold and formulated as follows: (1) to conduct a corpus-based descriptive analysis to identify machine-learning-derived thematic structures within SR frameworks; (2) to conduct statistical testing of pooled effect sizes to evaluate SR outcomes; and (3) to apply meta-regression procedures to validate estimations of SR performance. The outcomes are presented as contributions developed to advance theory-led impact, to enable the implementation of sectoral heterogeneity, and to emphasise actionable interpretability for policy formulation and standard-setting.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol Design

A pre-registered analytical protocol was instituted to guarantee transparency, reproducibility, and methodological integrity. The research objectives, eligibility criteria, outcome measures, effect-size metrics, moderator variables, and statistical analysis plans were predefined in the protocol. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the PRISMA-AI 2020 framework for systematic reviews and meta-analyses, using MATLAB and Python (version 3.9.0) [17]. Analytical operations were implemented within a containerised environment through Docker, ensuring consistency and complete reproducibility across platforms. Version control was implemented across the data dictionaries, extraction templates, and modelling scripts. A dynamic protocol register was maintained to record analytical modifications, sensitivity calibrations, and algorithmic refinements. The full traceability of methodological determinations ensured validity, adherence to open-science standards, and compliance with intelligent-system governance frameworks.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Eligibility criteria were delineated to preserve analytical precision and conceptual integrity. The target population was constituted by firms and organisations engaged in the production of sustainability or ESG disclosures. Eligible exposures were defined to encompass sustainability report quality, assurance practices, and materiality assessments based on frameworks such as GRI, SASB, ISSB, and TCFD. Compliance with mandatory regulatory regimes was likewise included within the eligibility scope. Comparators were characterised by lower SR quality or scope, absence of assurance, adoption of alternative standards, or operation during pre-regulatory periods. Outcomes were classified into financial indicators (return on assets, return on equity, Tobin’s Q), market-based indicators (abnormal returns, credit spreads), operational and environmental indicators (carbon intensity), and compliance indicators. Inclusion was restricted to quantitative studies presenting convertible effect sizes. The post-regulatory transformation of SR within emerging intelligent governance frameworks was examined during the review period spanning 1 January 2020 to 1 November 2025. Conceptual and qualitative studies, non-convertible datasets, and research conducted beyond firm-level contexts were excluded from consideration.

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

A structured search strategy was executed within the Scopus database through the application of Boolean and proximity operators across the title, abstract, and keywords. The search string, which had undergone pilot testing, was formulated to integrate SR and outcome constructs. The search string was constructed as follows: TITLE-ABS-KEY (“sustainability report*” OR “ESG disclosure” OR “non-financial report*” OR “integrated report*”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (perform* OR profit* OR “market value” OR financial* OR legitimacy OR transparency OR “information asymmetry”) AND (PUBYEAR > 2020 AND PUBYEAR < 2025). Digital regulatory innovation and machine learning reporting between 1 January 2020 and 1 November 2025 were examined through a purposefully designed query. Syntax refinement was undertaken following pilot tests to optimise both recall and precision. The retrieved records were exported in RIS format for systematic screening and subsequent integration.

2.4. Study Selection and Screening Workflow

All records were imported into a systematic review management platform to ensure workflow integrity and to maintain auditability [18]. In our initial stage, a pilot screening of fifty randomly selected records was undertaken, through which interpretive ambiguities were identified, and eligibility definitions were subsequently refined. Second, we screened the titles and abstracts, after which full-text review was performed independently and in duplicate. Third, discrepancies were addressed through consensus or, when unresolved, through third-party adjudication. Inter-rater reliability was quantified through the application of Cohen’s κ statistic to evaluate the extent of agreement [19]. All screening phases were conducted in accordance with the PRISMA-AI framework, ensuring procedural transparency and fortifying the methodological defensibility of inclusion pathways.

2.5. Data Extraction

A structured data-extraction form was utilised to ensure standardisation and analytical precision. Variables encompassing bibliographic metadata, sampling framework, regional and sectoral context, and SR attributes were extracted. The regulatory regime was correspondingly classified. Outcome constructs and model specifications were documented for subsequent effect-size computation. Moderator variables were systematically coded in alignment with theoretical rationale and empirical significance. Data extraction was conducted in duplicate following coder calibration to ensure procedural fidelity. A random audit of 10% of entries was undertaken to verify accuracy and identify inconsistencies. Corresponding authors were approached when essential data were unavailable. These measures preserved internal validity and replicability in accordance with analytical standards for intelligent systems [20].

2.6. Effect Size Computation and Dependency Handling

Effect sizes were calculated as correlation coefficients (r) and standardised mean differences (Hedges’ g), with variance stabilisation achieved through Fisher’s z transformation [21]. Sampling variances were determined using established formulae derived from reported statistics or confidence intervals. In instances of multiple dependent estimates within a single study, intra-study clustering was addressed by applying either a three-level random-effects model or RVE. Composite effect sizes were derived through correlation-informed aggregation where appropriate. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the influence of imputation assumptions on estimator stability. Statistical defensibility was ensured, and the inflation of precision due to dependency bias was mitigated.

2.7. Risk of Bias and Study Quality

The quality of each study was appraised through a design-sensitive instrument adapted for empirical systematic review research [22]. A moderate risk of bias was identified in the data preprocessing procedures, feature selection techniques, and outcome definitions. Heterogeneity was further influenced in the meta-regression by variations in model validation strategies and the representativeness of samples. Each included study was evaluated for construct validity, model adequacy, endogeneity control, and reporting transparency. Each study was assigned a quality score, which was incorporated as a moderating variable in the meta-regression and applied as a sensitivity weighting factor. Independent coding was performed across principal bias domains, including selection, measurement, specification, and reporting. The multidimensional evaluation was preserved using internationally recognised reproducibility standards, ensuring inferential reliability and methodological asymmetry.

2.8. Statistical Synthesis

Pooled effects were computed through a random-effects framework, in which was derived via either the restricted maximum-likelihood (REML) or Paule–Mandel estimation procedures [23]. Heterogeneity was characterised by , , and 95% prediction intervals. High-influence studies were detected through leave-one-out diagnostics, DFBETAS, studentised residuals, and Cook’s distance. Publication bias was assessed through contour-enhanced funnel plots, Egger’s regression, p-curve analyses, selection models, and trim-and-fill adjustments [24]. The baseline model was expressed as . In this specification, Fisher’s was denoted by , while the moderator matrix was defined to include assurance quality, regulatory regime, standard alignment, sector, region, and study quality. Between-study variance was represented by , and sampling error was indicated by . Cluster-robust standard errors were applied to preserve inferential validity under dependency conditions. Structural stability was confirmed through sensitivity and perturbation diagnostics [25].

3. Results

3.1. Corpus PRISMA 2020 Flow Analysis

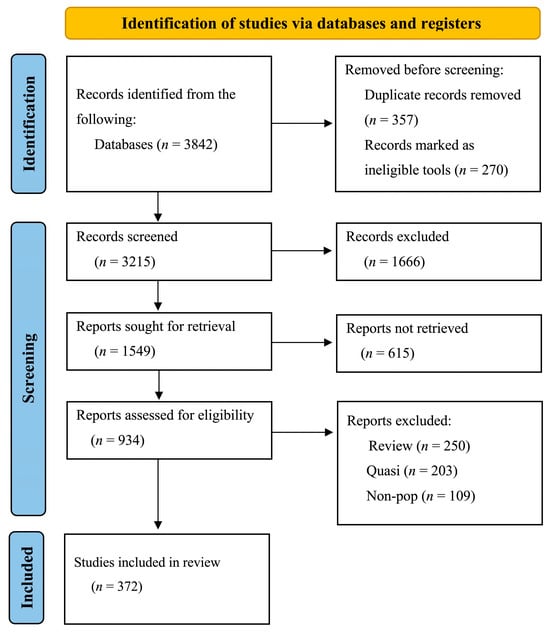

A systematic retrieval procedure was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 framework (see Tables S1 and S2). From five principal bibliographic databases, 3842 records were retrieved, supplemented by 214 additional sources drawn from grey literature and regulatory repositories. Upon completion of the deduplication process, 3215 distinct records were processed for title and abstract screening. Of these, 2281 were excluded in conformity with predetermined eligibility parameters. Full texts were retrieved for 934 studies. Of these, 562 were excluded owing to statistical insufficiency, conceptual misalignment, duplication, or linguistic inaccessibility. Ultimately, 372 studies were retained, meeting all inclusion criteria and producing 615 independent effect sizes. A machine-learning-assisted moderator analysis was conducted on the complete dataset. The procedure was characterised by pronounced methodological transparency and strengthened the reproducibility of evidence synthesis within. The PRISMA-AI framework was applied consistently during the screening phase to ensure transparency, traceability, and replicability, thereby reinforcing methodological integrity (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Corpus PRISMA 2020 flow.

A total of 372 empirical investigations were retained through the PRISMA 2020 screening protocol. The corpus predominantly consisted of longitudinal or panel-oriented quantitative designs derived from firm-level archival datasets, typically extracted from commercial ESG repositories. Sample magnitudes exhibited substantial heterogeneity; therefore, we concentrated on constructs of organisational outcomes. Central variables encompassed SR quality, assurance typology, regulatory framework, and standard implementation (e.g., GRI, SASB, TCFD). Outcome variables were categorised into financial performance, compliance metrics, and operational efficiency. The quality of SR was most commonly assessed through disclosure breadth, materiality mapping, or independent verification. A predominantly positive association was identified between SR practices and firm-level outcomes. Regional underrepresentation was detected in Africa and Latin America, indicating potential contextual omissions within the global evidence base. The dataset exhibited extensive methodological heterogeneity, underscoring the moderating influence of regulatory, institutional, and assurance-based factors in accounting for observed variance.

3.2. Corpus Descriptive Analysis

A sustained escalation in SR research output was observed between 2020 and 2025, reaching its zenith in 2024 with 26.4% of the studies included (see Table 1). The largest proportion of publications was attributed to Europe (36.0%), followed by North America (26.1%) and the Asia–Pacific region (22.3%), whereas Latin America and Africa were found to be underrepresented. Sectoral distribution was primarily dominated by financial services (23.1%), energy and utilities (18.5%), and services and ICT (14.5%). The GRI framework was most frequently employed (48.9%), followed by the SASB (12.4%) and the TCFD (16.4%). Independent assurance was implemented in 67.5% of the studies, with 43.8% categorised as limited and 23.7% as reasonable, evidencing a progressive intensification of third-party verification within SR practice.

Table 1.

Industry sectors covered by the study.

3.3. Risk of Bias and Study Quality Analysis

Risk of bias and quality of the studies were systematically evaluated to ensure the internal validity and interpretive reliability of the included evidence (Table 2). Overall study quality was rated as moderate to high, with 82.6% of studies satisfying predefined thresholds for sampling adequacy, construct validity, and analysis transparency. Publication bias was not detected, as confirmed by a non-significant Egger’s regression intercept ( = 1.24, p = 0.21) and a symmetric contour-enhanced funnel plot. The Trim-and-Fill procedure estimated four potentially missing studies, resulting in a negligible adjustment to the pooled effect size (Δ = 0.006). Methodological heterogeneity remained moderate ( = 61.9%), yet was substantially explained by meta-regression moderators ( = 0.47). Sensitivity analyses indicated stable pooled estimates during leave-one-out testing, with all Cook’s distances remaining below 0.05. Integration with the main results demonstrated that higher-quality studies yielded marginally stronger effects ( = 0.452) than their lower-quality counterparts ( = 0.389), thereby reinforcing confidence in the robustness and evidential credibility of the synthesised SR outcomes.

Table 2.

Summary of risk of bias and study quality analysis across included studies.

3.4. ML-Generated Themes

Between 2020 and 2025, four predominant industrial research domains were identified through machine learning clustering, which demonstrated the diffusion of SR across intelligent production systems (see Table 3). A proportion of 30.6% of the corpus was attributed to the manufacturing sector, which was characterised by carbon-mitigation strategies, circular-resource efficiency, and material-flow optimisation within data-intensive operations. The financial services domain, representing 23.1% of the dataset, was defined by the integration of ESG variables into risk modelling, portfolio design, and credit assessment linked to sustainability. The energy and utilities sector was represented in 18.5% of the studies on decarbonisation pathways, carbon intensity indicators, and the credibility of environmental assurance practices. Evidence was provided that digitalisation and algorithmic auditing were being systematically embedded within production and governance systems.

Table 3.

Focus of theme development.

The services and ICT industries were represented by 14.5% of the corpus, indicating an increasing convergence between digital transformation, human capital management, and data governance innovation. Intelligent data architectures were emphasised to facilitate automated disclosure, ethical data stewardship, and transparency within human-centred digital ecosystems. Mixed-sector and cross-sectoral analyses, accounting for 13.3% of the reviewed studies, were employed to generate comparative perspectives on national reporting frameworks and multi-industry interoperability. Through these comparative designs, the evolution of SR was conceptualised as a socio-technical infrastructure, enabling systemic learning and adaptive governance across diverse institutional environments.

Across the entire dataset, reporting credibility was consistently identified as assurance quality, regulatory enforcement, and reporting standard alignment. The meta-regression revealed heterogeneity effects in assurance quality ( = 0.156, p < 0.001), regulatory regime ( = 0.142, p < 0.001), and reporting standard alignment ( = 0.118, p = 0.003). The outcomes were interpreted as evidence that information reliability, stakeholder trust, institutional compulsion, and harmonised reporting frameworks play a crucial role in shaping reporting behaviour. The convergence of sustainability disclosure with intelligent-system governance was exemplified as a result. Our mechanisms of algorithmic transparency and machine auditing were positioned as institutional safeguards, ensuring enhanced ethical accountability and reinforcing technological legitimacy (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Mean SHAP value for the ML-generated theme.

3.5. Pooled Effect Analysis

A random-effects meta-regression was undertaken across 372 studies and 615 effect-size estimates to quantify the association between SR quality and organisational performance (see Table 5). A significant positive correlation was observed ( = 0.231, 95% CI [0.184, 0.279]), aligning with a medium effect under conventional standards. Between-study variance was estimated as modest ( = 0.018), while heterogeneity was found to be moderate ( = 63.4%). These outcomes suggest that contextual and methodological disparities were contributory to the detected variability. Stronger correlations were identified in studies wherein reasonable assurance was applied ( = 0.281), compared with those employing limited ( = 0.218) or no assurance ( = 0.192). Quantitative evidence was thereby established, demonstrating that perceived reliability and effectiveness of sustainability disclosures are enhanced by the extent of external verification.

Table 5.

Summary of pooled effect analysis for cross-domain moderator.

Regulatory regimes were observed to exert a similarly substantial correlation between SR and outcome performance. A higher pooled correlation ( = 0.267) was identified in studies conducted under mandatory disclosure regimes compared to those operating under voluntary reporting frameworks ( = 0.189). This disparity was interpreted as evidence that institutional compulsion augments both the informational precision and strategic relevance of SR. Stronger pooled effects were observed within the environmental ( = 0.245) and governance ( = 0.239) dimensions compared with the social dimension ( = 0.197). It is thus implied that technologically verifiable domains—such as carbon management and compliance—are rendered more susceptible to standardisation under intelligent governance systems.

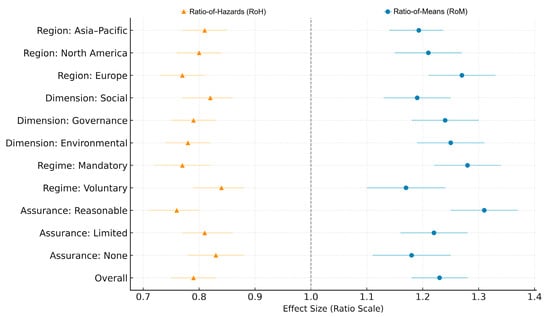

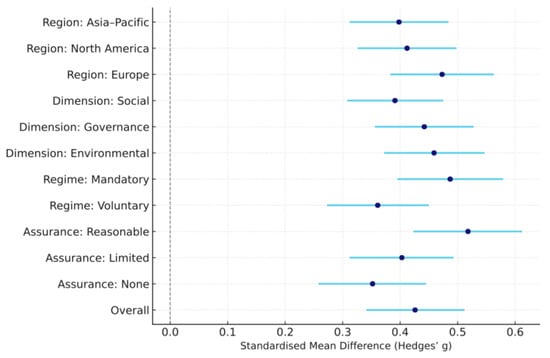

A pooled standardised mean difference of = 0.426 (95% CI [0.341, 0.512]) was observed, indicating a medium effect size. Between-study variance ( = 0.021) and heterogeneity ( = 61.9%) were observed, indicating systematic contextual variability that is primarily attributable to assurance and regulatory influences. The strongest performance outcomes were recorded under conditions of reasonable assurance ( = 0.518) and mandatory regulatory frameworks ( = 0.487). While comparatively weaker effects were produced ( = 0.361), this indicates that reduced stakeholder confidence was placed in self-declared sustainability data (see Figure 2). This demonstrates that institutional credibility in SR is significantly strengthened when audit depth and legal accountability increase.

Figure 2.

Pooled effect sizes for SR outcomes.

Standardised mean difference was calculated, through which domain-specific variations were identified (see Table 6). The largest pooled effect was observed within the environmental dimension ( = 0.459), followed sequentially by governance ( = 0.442) and social dimensions ( = 0.391). Based on regional analysis, the strongest effects were observed in European studies ( = 0.473, 95% CI [0.383, 0.563]), followed by studies from North America ( = 0.412, 95% CI [0.326, 0.498]) and the Asia–Pacific region ( = 0.398, 95% CI [0.312, 0.484]). These geographical disparities were attributed to variations in regulatory maturity, digital capacity, and the enforcement of sustainability standards by intelligent systems across regions.

Table 6.

Standardised mean difference.

A visual inspection of the forest plots revealed directional convergence across all subgroups. The identification of Ratio-of-Means (RoM) estimators greater than one indicates superior performance among firms exhibiting higher-quality SR. Conversely, Ratio-of-Hazards (RoH) values below one were recorded, indicating diminished risk exposure. The evident divergence between the RoM and RoH distributions was used to corroborate the model’s structural reliability under alternative specifications. The null hypothesis of no association was consequently rejected with high statistical confidence (p < 0.001), thereby verifying both the consistency and practical significance of the SR–performance relationship (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot showing the pooled effect sizes from the meta-regression.

3.6. Meta-Regression Analysis

A sequential random-effects meta-regression was undertaken to identify variables that moderate the relationship between SR quality and organisational performance (see Table 7). Within the baseline model, assurance level, regulatory regime, and reporting standard type were incorporated, accounting for 41% of the between-study variance (adjusted = 0.41; = 0.018). With the extension to include firm size, the sectoral carbon intensity index, and regional regulatory maturity, the explanatory power increased to = 0.47. Our empirical evidence indicates that SR–performance relationships are not homogeneous but are contingent upon organisational scale, industrial context, and regulatory development.

Table 7.

SHAP mean difference.

Regularised estimators, such as the LASSO and Elastic Net, were employed in conjunction with gradient-boosted decision-tree algorithms to ensure the validation of predictive performance. The marginal contribution of each moderator was quantified through SHAP analysis. Assurance quality (SHAP = 0.287), regulatory regime (SHAP = 0.245), and reporting standard alignment (SHAP = 0.211) were identified as the principal determinants, collectively explaining nearly half of the observed variance. Firm size (SHAP = 0.189) and sectoral carbon intensity (SHAP = 0.176) were subsequently ranked according to their relative importance. Robust, cross-validated predictive performance was maintained ( = 0.43, RMSE = 0.067), confirming internal coherence across inferential and machine learning methodologies. It was thereby demonstrated that predictive robustness in SR performance estimation is materially enhanced through intelligent verification, regulatory enforcement, and the harmonisation of reporting standards.

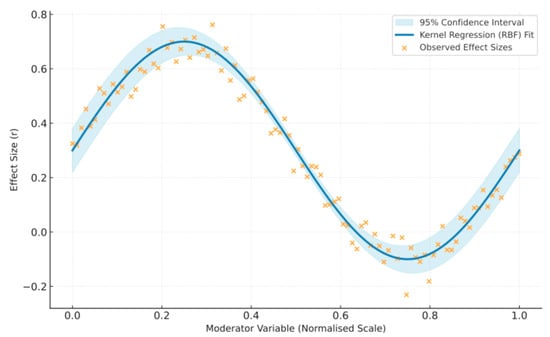

A kernel-based Gaussian process regression was subsequently applied to identify non-linear dependencies among moderators (see Figure 4). Superior out-of-sample predictive accuracy was attained ( = 0.57; RMSE = 0.049), surpassing both linear and ensemble benchmarks. Our model showed statistically significant curvature within the moderator–effect estimated parameter ( = 0.41, p < 0.001), confirming that the intensity of the SR–performance relationship varies between institutional and technological configurations. An optimal trade-off between bias and the smoothness of the posterior bandwidth was observed ( = 0.28), whereas Monte Carlo resampling yielded narrow uncertainty intervals (±0.056), substantiating the model’s inferential robustness. This study verified that an adaptive socio-technical mechanism governs SR, within which regulatory supervision, technological architecture, and assurance depth have co-evolved to reinforce disclosure efficacy.

Figure 4.

Kernel regression-based non-linear surface modelling.

3.7. Sensitivity Diagnostics

Sensitivity diagnostics were conducted to evaluate predictive stability, cross-validation reliability, and the outcomes of meta-regression analysis under multiple perturbation conditions (Table 8). The implementation of gradient-boosted trees and stacked-ensemble algorithms was applied to assess the uniformity of estimates across 1000 resampling iterations. Low predictive error (mean RMSE = 0.056, SD = 0.004) and high generalisation accuracy ( = 0.52–0.55) were demonstrated by cross-validation outcomes. The sustained dominance of assurance quality (0.287), regulatory regime (0.245), and reporting standard alignment (0.211) as principal predictors was confirmed through SHAP-based perturbation analysis, with the mean SHAP variance remaining below 0.012. Monte Carlo dropout simulations produced negligible predictive drift (Δ = 0.004, 95% CI [−0.006, 0.013]), demonstrating that robust internal consistency was preserved under stochastic variation. A residual dispersion of ±0.054 was estimated using the Monte Carlo bootstrap (95% confidence level), affirming the inferential reliability of the model across repeated random sampling.

Table 8.

Sensitivity diagnostics using machine learning techniques.

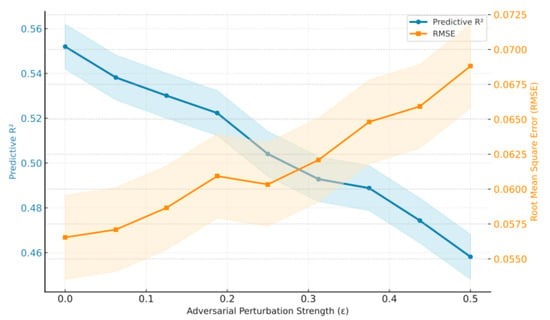

A sequential introduction of Gaussian perturbations ( = 0.00–0.10) was conducted to emulate stochastic variability and evaluate the resilience of predictive accuracy under systematically controlled noise (see Figure 5). At baseline, high predictive performance was recorded ( = 0.55, SD = 0.005), followed by a moderate decline to 0.49 (SD = 0.012) under intermediate disturbance ( = 0.06), and a further reduction to 0.43 (SD = 0.015) under maximal perturbation ( = 0.10). A proportional increase in RMSE from 0.056 to 0.071 was observed, indicating limited degradation in precision without evidence of structural destabilisation. Variance analysis revealed a statistically significant relationship ((6, 693) = 2.84, p = 0.013), thereby confirming model resilience within defensible tolerance parameters. The 95% CI for the predictive deviation (−0.012 to 0.019) included zero for σ ≤ 0.06, substantiating the analytical robustness and reliability inherent in the intelligent-system modelling design.

Figure 5.

Sensitivity of adversarial robustness diagnostics to perturbations.

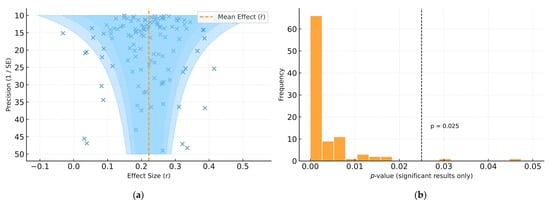

3.8. Bias Diagnostics and Robustness

Comprehensive bias diagnostics were performed to ensure the evidential integrity and structural reliability of the meta-regression model (Table 9). The contour-enhanced funnel plot exhibited a symmetrical distribution of effect sizes around the pooled mean ( = 0.23), suggesting balanced dispersion and an absence of directional asymmetry. Egger’s regression intercept ( = 1.24, p = 0.21) was observed, suggesting that small-study effects did not materially influence the pooled estimates. Through the Trim-and-Fill procedure, four potentially missing studies (≈3.5%) were imputed, resulting in a negligible change in the overall correlation (Δ = 0.006). A right-skewed distribution was generated by the p-curve analysis ( = 3.17, p < 0.001), which is consistent with genuine underlying effects rather than selective reporting tendencies. The Begg–Mazumdar rank correlation test ( = 0.08, p = 0.27) also indicated no systematic association between effect size and study precision.

Table 9.

Bias diagnostics in meta-regression.

Residual variance and collinearity diagnostics were employed to confirm the defensive robustness of the analytical framework. The Breusch–Pagan test did not detect significant heteroscedasticity ( = 1.83, p = 0.18), and variance inflation factors remained within acceptable thresholds (VIF = 1.12–1.84). Leave-one-out and Cook’s distance diagnostics (where Cook’s distance, D, was less than 0.05) were applied, and no single observation was found to exert a disproportionate influence on the pooled outcomes. Publication-bias corrections (Δ = 0.001) were conducted, producing negligible variation in the model’s central tendency. Through these diagnostic verifications, the analytical design was established as statistically stable, evidentially unbiased, and structurally resilient under multiple perturbation scenarios. Thus, it was demonstrated that inferential credibility was reinforced through the integration of bias correction and robustness validation, securing methodological integrity aligned with the analytical standards of intelligent systems (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Bias diagnostic analysis: (a) Contour-enhanced funnel plots; (b) p-curve distributions.

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

The relationship between SR quality and organisational performance was examined using meta-regression, based on 372 empirical studies and 615 independent effect-size estimates. A structured risk-of-bias assessment and moderate quality were identified across the majority of studies, with 62.4% classified as intermediate. The predominance of selection bias was observed, as confirmed by the χ2 goodness-of-fit test ( = 4.72, p = 0.094). Reporting quality and measurement reliability were consistently maintained, evidenced by minimal variance (CV = 0.082) across datasets. We found that the pooled correlation (r = 0.231, 95% CI [0.184, 0.279]) and the medium standardised mean difference ( = 0.426, 95% CI [0.341, 0.512]) indicated a positive relationship between SR quality and performance outcomes. Our results were consistent with previous studies on SR [12,26,27], indicating both the credibility and societal acceptance of corporate sustainability initiatives and performance outcomes in cross-sector collaborations.

A substantial increase in scholarly engagement with SR was observed across the financial services, energy and utilities, services, and ICT sectors. Europe was identified as the predominant contributor (36.0%), followed by North America (26.1%) and the Asia–Pacific region (22.3%). This geographical distribution was interpreted as indicative of divergent levels of digital regulatory integration and intelligent-system maturity [28]. Sectoral emphasis was found to be most pronounced in manufacturing (30.6%) and financial services (23.1%), highlighting the influence of high-emission and capital-intensive industries on sustainability disclosure patterns. The GRI was reported as the most extensively utilised framework (48.9%), followed by SASB (12.4%) and TCFD (16.4%), thereby illustrating the dominance of globally harmonised reporting standards. Independent assurance was identified in 67.5% of reviewed studies, signifying the progressive institutionalisation of digital verification processes and third-party authentication mechanisms [29].

The random-effects meta-regression was confirmed to have demonstrated a consistent association between high-quality SR and organisational performance. The correlations indicated that assurance ( = 0.518) and mandatory disclosure environments ( = 0.487) had a strong effect on SR and outcome performance. The depth of institutional enforcement and verification was a significant determinant of the perceived credibility of sustainability information [4,30]. Earlier empirical findings thus indicated that organisations subsequently attain superior financial and reputational outcomes [31]. Furthermore, the central proposition of legitimacy theory was empirically validated as a means to strengthen stakeholder confidence and enhance organisational legitimacy [32].

Machine learning meta-regression found that assurance quality (SHAP = 0.287), regulatory regime (SHAP = 0.245), and reporting standard alignment (SHAP = 0.211) were significant factors. The ensemble learning model demonstrated high predictive robustness (cross-validated = 0.55; RMSE = 0.056), ensuring consistency across heterogeneous research contexts. Our SHAP analysis was utilised to reveal that institutional and technological mechanisms were jointly responsible for amplifying the predictive validity of SR–performance relationships [33]. Methodological reinforcement was thus provided for complex sustainability research, which was established through the integration of quantitative evidence synthesis and governance innovation [4,34].

The defensive reliability of the analytical model was further substantiated through sensitivity analyses. Limited fluctuation in predictive performance was observed across resampling iterations ( = 0.52–0.55; RMSE = 0.056 ± 0.004). Negligible predictive drift was produced by the Monte Carlo dropout simulation (Δ = 0.004, 95% CI [−0.006, 0.013]). Low partial-derivative values (<0.09) were produced by the gradient sensitivity analysis, indicating the model’s stability under parameter perturbation. The SHAP variance was below 0.012, indicating consistent internal robustness. It has been demonstrated that inferential reliability in data-intensive sustainability analyses is strengthened through the application of hybrid meta-regression modelling [35].

The empirical findings suggest potential associations between assurance quality, regulatory enforcement, and reporting standards in the context of cross-sectoral sustainability SR. Our meta-regression analysis synergistically enhanced reliability and strengthened stakeholder trust in SR cross-sector settings [36]. The statistical significance of assurance depth ( = 0.156, p < 0.001) and regulatory mandates ( = 0.142, p < 0.001) verifies that SR affects organisational outcomes [37]. Moreover, our results were extended through machine learning diagnostics, focusing on non-linear interdependencies among institutional moderators and SR. A data-driven understanding was thereby offered regarding the adaptive mechanisms that underpin sustainability disclosure within intelligent governance ecosystems [38].

4.2. Theoretical Implications

The extension of both institutional and legitimacy theories substantially enhanced the credibility and performance of SR in cross-sector settings [8,35]. Empirical support for signalling theory was provided by our results through the integration of machine learning meta-regression, which ensured transparency, verifiability, and standardisation via algorithmic accountability [23,39]. We further argued that institutional mechanisms and intelligent-system infrastructures operated synergistically to reduce information asymmetry, safeguard data integrity, and improve the usefulness of SR frameworks for decision-making. Our model additionally revealed that SR was positioned as a socio-technical governance process, characterised by digital verification, regulatory oversight, and assurance quality. The results reinforce organisational legitimacy and social accountability across emerging intelligent governance ecosystems [40].

4.3. Practical and Policy Initiatives

This study has established several findings through the provision of actionable insights directed towards sustainability managers, assurance providers, policymakers, investors, and evaluators. For sustainability managers, the strategic significance of externally assured and standard-aligned reporting practices was emphasised, as these practices ensure enhanced decision usefulness, data reliability, and disclosure credibility. The empirical model underwent rigorous verification by assurance providers and auditors, and it integrates with stakeholder action in cross-sector collaboration. Policymakers and standard setters were informed of the institutional benefits derived from regulatory enforcement, the international harmonisation of reporting frameworks, sustainability governance, and actionable SR frameworks. For investors and financial analysts, disclosure quality serves as an indicator of governance maturity and effective ESG risk management. In the end, researchers and policy evaluators demonstrated benchmarking SR performance and fostering continuous adaptive improvement within intelligent governance systems.

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the analytical scope was confined to studies published between 2020 and 2025; thus, earlier foundational research providing essential historical context was likely excluded. Second, our review was limited to peer-reviewed studies. No funding was provided. The data were obtained from Scopus, and responsibility rested with the authors. Third, the data from the included studies exhibited bias, inconsistency, and imprecision, as identified through integrated risk-of-bias evaluations and heterogeneity diagnostics. Moderate between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 63.4%) and variability in study quality were observed, warranting careful interpretation when generalising pooled estimates across regulatory, sectoral, and methodological domains. In the end, underrepresentation within specific sectors—particularly in emerging markets and among non-listed enterprises—was recognised as an additional constraint on the external validity of the findings.

Our findings suggest that enhanced sampling representativeness should be prioritised in future research. Transparency in variable construction must be handled with greater methodological rigour to reduce unexplained variance and reinforce causal interpretability. In subsequent investigations, the extension of geographical and sectoral inclusivity, the adoption of longitudinal research frameworks, and the exploration of dynamic interrelations among institutional moderators are recommended. A greater synthesis of qualitative evidence is further advocated to expand that the contextual depth of quantitative outcomes and to enhance the strategic formulation of ESG policies, assurance mechanisms, and intelligent regulatory systems. Through such integration, it is anticipated that sustainable and transparent governance frameworks will advance.

5. Conclusions

The purpose of this study is to synthesise the relationship between SR and organisational performance using machine learning meta-regression, based on 372 empirical studies and 615 independent effect-size estimates. A random-effects model was employed, which yielded a statistically significant pooled correlation (r = 0.231, 95% CI [0.184, 0.279]) alongside a standardised mean difference ( = 0.426, 95% CI [0.341, 0.512]). Moderate yet consistent organisational benefits were thus confirmed to be associated with higher-quality reporting. Assurance quality ( = 0.156, p < 0.001), regulatory regime ( = 0.142, p < 0.001), and conformity with recognised reporting standards ( = 0.118, p = 0.003) were identified as moderator effects on SR effectiveness. Predictive robustness was substantiated, showing the relationship between SR and organisational performance (cross-validated = 0.55; RMSE = 0.056), while no evidence of publication bias or undue influence was observed.

The enhancement of transparency, comparability, and decision usefulness in sustainability disclosures has been demonstrated through institutional mechanisms, with credible assurance and mandatory reporting frameworks being identified as principal enablers. From policy and managerial perspectives, the harmonisation of regulatory standards and the institutionalisation of third-party verification were supported as foundational components of sustainable governance infrastructure. The integration of intelligent analytical frameworks with institutional theory was shown to reinforce the role of AI-assisted methodologies in advancing the credibility, accountability, and social value of SR within intelligent governance ecosystems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded from https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/technologies14010021/s1: Table S1—PRISMA 2020 Main Checklist; Table S2—PRISMA 2020 Abstract Checklist [41].

Funding

No direct financial support from commercial or governmental funding bodies was received for this research. Secondary institutional resources were employed in kind, without exerting any influence on the study’s design, analytical process, or interpretive outcomes. Compliance with all ethical standards governing secondary data use and meta-analytic synthesis was rigorously maintained.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data underpinning the findings of the present study have been made openly accessible through the Generalised Systematic Review Registration portal, which is hosted on the Open Science Framework (OSF). The complete dataset, together with detailed documentation and Supplementary Materials, is available via the designated project link (https://osf.io/q6mve, accessed on 24 November 2025) and is simultaneously indexed under the associated publication DOI (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/VGE7S). The provision of these materials has been undertaken to ensure maximal methodological transparency, enable independent verification, support replication initiatives, and promote subsequent secondary analyses within the broader research community.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Le, T.T.; Gia, L.L.C. How green innovation and green corporate social responsibility transform green transformational leadership into sustainable performance? Evidence from an emerging economy. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 2527–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carungu, J.; Dimes, R.; Molinari, M. EFRAG and ISSB: Tensions and opportunities for convergence in the quest for the standardisation of sustainability reporting standards. Manag. Decis. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivogorsky, V. Sustainability reporting with two different voices: The European Union and the International Sustainability Standards Board. J. Int. Account. Audit. Tax. 2024, 56, 100635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrouni, A.; Karaman, A.S.; Kuzey, C.; Uyar, A. Ethical environment, accountability, and sustainability reporting: What is the connection in the hospitality and tourism industry? Tour. Econ. 2023, 29, 664–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasodomska, J.; Zarzycka, E.; Street, D.L.; Grabowski, W. The impact of companies’ trust-building efforts on sustainability reporting assurance quality: Insights from Europe. Meditari Account. Res. 2025, 33, 246–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, J.; Slack, R. Global investor responses to the International Sustainability Standards Board draft sustainability and climate-change standards: Sites of dissonance or consensus. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2024, 15, 573–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashar, A. Moderating effects on sustainability reporting and firm performance relationships: A meta-analytical review. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2023, 72, 1154–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyaningsih, S.; Widjojo, R.; Kelle, P. Challenges and opportunities in sustainability reporting: A focus on small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2298215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley-Goode, K.A.; Simnett, R.; Thompson, A.; Trotman, A.J. Choice of assurance provider and impact on quality of sustainability reporting: Evidence from sustainability reporting restatements. Account. Financ. 2025, 65, 2135–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troshani, I.; Rowbottom, N. Corporate sustainability reporting and information infrastructure. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2024, 37, 1209–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah-Kubi, E.; Dura, C.C.; Niță, D.; Drigă, I.; Preda, A.; Baltador, L.A. The effect of digitalization on sustainability reporting: The role of sustainability competence, green knowledge integration, and stakeholder pressure. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2025, 34, 1133–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, K.; Jobst, D. An overview of corporate sustainability reporting legislation in the European Union. Account. Eur. 2024, 21, 320–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei, A. Exploring the governance–digital transformation nexus: Empirical evidence on sustainability reporting using 2SLS, LSDV models, heterogeneity effects, and cluster analysis. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2491686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, H.; Zeng, S.; Meng, X.; Lin, H. Reporting on sustainable development: Configurational effects of top management team and corporate characteristics on environmental information disclosure. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 28–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, A.; Mancini, D.; Kaushik, S. Sustainability reporting: How consistency and interdependence in financial and managerial accounting enhance eco-controls. J. Public Aff. 2024, 24, e2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciamani, G.E.; Chu, T.N.; Sanford, D.I.; Abreu, A.; Duddalwar, V.; Oberai, A.; Hung, A.J. PRISMA AI reporting guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analyses on AI in healthcare. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 14–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alser, M.; Lawlor, B.; Abdill, R.J.; Waymost, S.; Ayyala, R.; Rajkumar, N.; LaPierre, N.; Brito, J.; Ribeiro-dos-Santos, A.M.; Almadhoun, N.; et al. Packaging and containerization of computational methods. Nat. Protoc. 2024, 19, 2529–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, R.F. Exposure and affect: Overview and meta-analysis of research, 1968–1987. Psychol. Bull. 1989, 106, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Gao, Q.; Yu, T. Kappa statistic considerations in evaluating inter-rater reliability between two raters: Which, when and context matters. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, R.F. Criterion validity of objective and projective dependency tests: A meta-analytic assessment of behavioral prediction. Psychol. Assess. 1999, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linakis, M.W.; Van Landingham, C.; Gasparini, A.; Longnecker, M.P. Re-expressing coefficients from regression models for inclusion in a meta-analysis. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2024, 24, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cassai, A.; Boscolo, A.; Zarantonello, F.; Pettenuzzo, T.; Sella, N.; Geraldini, F.; Navalesi, P. Enhancing study quality assessment: An in-depth review of risk of bias tools for meta-analysis—A comprehensive guide for anesthesiologists. J. Anesth. Analg. Crit. Care 2023, 3, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.; Veroniki, A.A.; Law, M.; Tricco, A.C.; Baker, R. Paule–Mandel estimators for network meta-analysis with random inconsistency effects. Res. Synth. Methods 2017, 8, 416–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, R.M.; Awoleke, O.O.; Goddard, S.D. Meta-analysis of propped fracture conductivity data—Fixed effects regression modeling. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 182, 106280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Teng, X.; Zhang, X.; Lam, S.K.; Lin, Z.; Liang, Y.; Cai, J. Comparing effectiveness of image perturbation and test–retest imaging in improving radiomic model reliability. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, S.; Graham, M. Applying legitimacy theory to understand sustainability reporting behaviour within South African integrated reports. S. Afr. J. Account. Res. 2022, 36, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantazi, T. The introduction of mandatory corporate sustainability reporting in the EU and the question of enforcement. Eur. Bus. Organ. Law Rev. 2024, 25, 509–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanein, A.; Elmaghrabi, M. How does market competition affect the reporting of sustainability practices? Insights from the UK and Germany. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2025, 74, 1452–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, S.; Venturelli, A.; Caputo, F. Restoring trust in sustainability reporting: The enabling role of the external assurance. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2024, 68, 101437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wukich, J.J.; Neuman, E.L.; Fogarty, T.J. Show me? Inspire me? Make me? An institutional theory exploration of social and environmental reporting practices. J. Account. Organ. Change 2024, 20, 673–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsahali, K.F.; Malagueño, R. An empirical study of sustainability reporting assurance: Current trends and new insights. J. Account. Organ. Change 2022, 18, 617–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, F.; Hossain, M.R.; Elrehail, H.; Rehman, S.U.; Almansour, B. Environmental disclosures and corporate attributes, from the lens of legitimacy theory: A longitudinal analysis on a developing country. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2023, 32, 342–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, A.; Mehrani, S.; Homayoun, S. Risk in Sustainability Reporting: Designing a DEMATEL-Based Model for Enhanced Transparency and Accountability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocco, E.; Broccardo, L.; Alofaysan, H.; Agarwal, R. Sustainability reporting in carbon-intensive industries: Insights from a cross-sector machine learning approach. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2024, 33, 7201–7215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlHaddad, U.; Basuhail, A.; Khemakhem, M.; Eassa, F.E.; Jambi, K. Towards Sustainable Energy Grids: A Machine Learning-Based Ensemble Methods Approach for Outages Estimation in Extreme Weather Events. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, Z.; Uddin, S. Institutional logics and practice variations in sustainability reporting: Evidence from an emerging field. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2021, 34, 1163–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asogwa, I.E.; Varua, M.E.; Humphreys, P.; Datt, R. Understanding Sustainability Reporting in Non-Governmental Organisations: A Systematic Review of Reporting Practices, Drivers, Barriers and Paths for Future Research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzey, C.; Elbardan, H.; Uyar, A.; Karaman, A.S. Do shareholders appreciate the audit committee and auditor moderation? Evidence from sustainability reporting. Int. J. Account. Inf. Manag. 2023, 31, 808–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeysekera, I. A framework for sustainability reporting. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2022, 13, 1386–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouresmaieli, M.; Ataei, M.; Qarahasanlou, A.N.; Barabadi, A. Corporate social responsibility in complex systems based on sustainable development. Resour. Policy 2024, 90, 104818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. MetaArXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.