Abstract

This paper asks whether debt among affluent consumers reflects rational leverage, comparable to firms, or the influence of cognitive biases. Using survey data on Brazilian bank clients, we combine logistic regressions with a finite-mixture-inspired, rule-based classification and a test based on a ten-business-day overdraft grace period to identify heterogeneity in borrowing behavior. In the high-income subsample, Cognitive Reflection Test scores are unrelated to debt incidence, diverging from prior evidence in mixed-income populations. Among indebted affluent respondents, most borrowing is cost-sensitive and consistent with deliberate leverage (about 80 percent), while a minority displays patterns consistent with optimism bias and overconfidence (about 20 percent). The institutional feature of a temporary grace period lowers the effective cost of short-term credit and is associated with a marked reduction in overdraft use, reinforcing the leverage interpretation. Overall, consumer debt is heterogeneous; for the affluent, it largely aligns with leverage, though behavioral biases persist at the margins. Policy for high-income borrowers should prioritize targeted measures that address optimism bias and overconfidence while preserving deliberate leverage management through clear disclosures and monitoring of sensitivity to short-term credit costs.

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation, Research Question, and Hypotheses

Consumer indebtedness has long been associated with problems of self-control and poor cognitive reflection. A finding from Germany, where credit lines are broadly accessible, shows that individuals who perform poorly on the Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT) are more likely to rely on overdraft facilities, suggesting that debt use reflects impulsivity and a lack of deliberation rather than rational calculation (Dick & Jaroszek, 2014). This perspective aligns with behavioral accounts in which cognitive biases (systematic deviations from rational judgment) distort financial decision-making (Kahneman et al., 1982; Kahneman, 2011; Da Silva et al., 2023).

However, subsequent evidence indicates that this interpretation does not hold uniformly across income groups. In our earlier work (Da Silva et al., 2018), we replicated the German findings in a mixed-income sample but observed a striking reversal among high-income consumers. For this group, indebtedness was not explained by poor CRT performance. Instead, debt usage appeared consistent with leverage, akin to firms strategically using credit for investment purposes. Moreover, institutional practices reinforced this interpretation: banks often grant high-income clients grace periods before charging overdraft interest, effectively treating consumer debt like working capital loans to businesses. These findings raise a crucial puzzle: is high-income consumer borrowing truly rational leverage, or does it remain partly shaped by cognitive biases that our earlier design could not disentangle?

This paper directly addresses this puzzle by combining a data-driven approach with a structured bias framework. We reanalyze the dataset from our prior study, mapping observed borrowing behavior onto testable signatures of cognitive bias. This step was assisted by ChatGPT: we supplied an auxiliary document containing a comprehensive catalog of cognitive biases, and the LLM used the reference to nominate biases that our variables could plausibly capture; this assistance did not involve locating or selecting the academic studies discussed in the literature review, which were identified manually by the authors. To move beyond simple correlations, we supplement logistic regressions with a rule-based classification scheme inspired by finite-mixture modeling. In statistical terms, finite-mixture models separate a population into latent subgroups with different underlying relationships. Borrowing from this logic, we distinguish two borrower types: (1) a leverage-consistent class, characterized by debt coexisting with higher CRT performance, fewer arrears, and sensitivity to institutional costs, and (2) a bias-consistent class, characterized by debt linked to lower CRT scores and patterns of miscalibrated expectations. We, therefore, formulate two hypotheses, distinguishing between leverage-consistent and bias-consistent borrowing.

Hypothesis 1.

Among high-income consumers, debt is unrelated to poor cognitive reflection and instead reflects rational use of credit, consistent with firm-like leverage.

Hypothesis 2.

A subset of high-income consumers still exhibits borrowing patterns consistent with cognitive biases.

By testing these hypotheses, we contribute to a clearer understanding of the heterogeneity in high-income consumer debt behavior. We separate rational (leverage-consistent) from bias-consistent borrowing among the affluent. We show that most high-income debt is cost-sensitive and, thus, consistent with deliberate leverage, while a minority exhibits patterns consistent with optimism and overconfidence. Our empirical design combines the previously described regressions and the finite-mixture-inspired classification with a market-generated cost test based on the overdraft grace period.

1.2. Overview of Approach, Findings, and Contribution

This paper examines whether the debt of affluent consumers reflects deliberate, firm-like leverage or instead reflects the influence of cognitive biases. Using survey data on Brazilian high-income bank clients, we combine three complementary strategies: logistic regressions with equivalence testing of Cognitive Reflection Test effects; a transparent rule-based classification, inspired by mixture logic that separates leverage-consistent from bias-consistent borrowers; and an institutional price-sensitivity test that exploits a ten-business-day overdraft grace period available to these clients.

The results indicate that, within the affluent segment, cognitive reflection is not a meaningful predictor of holding debt. Among those who borrow, behavior is heterogeneous: most cases align with leverage that is cost-sensitive and rarely in arrears, while a smaller subset displays patterns consistent with optimism or overconfidence. Overdraft use also responds strongly to the grace-period regime, which points to price-responsive leverage rather than systematic mistakes. Note that in our coding, overdraft use refers to the interest-bearing state. The ten-day grace period makes short negative balances costless if cleared in time, and affluent clients typically repay or transfer funds within the window. As a result, the measured incidence of overdraft falls, which is the pattern predicted by a cost-sensitive, leverage interpretation.

These findings matter because affluent households control a disproportionate share of deposits, credit lines, and marketable assets, so their borrowing choices propagate quickly to bank balance sheets, liquidity conditions, and asset prices. If their debt largely represents deliberate, price-sensitive leverage, blanket debiasing or paternalistic constraints can suppress efficient risk sharing and liquidity provision. By contrast, identifying the smaller, bias-prone segment enables targeted consumer-protection and underwriting that reduce default risk without taxing productive leverage. The paper’s contribution is therefore twofold: it reframes how researchers, lenders, and regulators should interpret high-net-worth borrowing, and it offers a practical toolkit (equivalence tests, a mixture-inspired classifier, and an institutional cost test) for distinguishing leverage from bias in household finance and for improving policy design, risk management, and the external validity of theories estimated on mixed-income samples.

1.3. Related Literature

The benchmark approach, and the foundational line of inquiry, conceives borrowing as an intertemporal optimization problem. Consumers, like firms, may use credit as a tool for smoothing consumption, financing investment opportunities, or managing liquidity shocks. Classical models, such as Modigliani and Brumberg’s life-cycle hypothesis, predict that forward-looking individuals borrow and save to maximize lifetime utility. In the same vein, Friedman’s permanent income hypothesis posits that consumption tracks expected permanent income, with borrowing used to smooth temporary income shocks. This perspective strengthens our leverage interpretation for the affluent: like firms, high-income consumers may rationally use short-term credit as a liquidity-management tool, aligning borrowing with long-run income expectations rather than with transitory constraints. We note, however, that our dataset does not include direct measures of expectations or permanent-income beliefs, so this link is interpretive rather than directly tested.

In household finance, Campbell (2006) and Lusardi and Mitchell (2014) show how consumption and borrowing decisions are shaped by heterogeneity in financial literacy, risk preferences, and market participation. In corporate finance, Myers (1984) shows how firms strategically use leverage to exploit tax shields, hedge liquidity risk, and fund growth. Extending this analogy, our earlier study (Da Silva et al., 2018) suggested that affluent consumers often behave in ways similar to firms, treating credit not as a signal of financial distress but as a tool for managing portfolio liquidity. Institutional practices, such as preferential overdraft terms and extended grace periods offered to high-net-worth clients, further reinforce this parallel, blurring the boundary between household borrowing at the top of the income distribution and corporate financial intermediation.

In contrast, behavioral finance research has presented multiple ways in which cognitive biases distort household borrowing. Meier and Sprenger (2010) provide field-experiment evidence that present-biased time preferences are strongly associated with credit card borrowing: individuals identified as present-biased are more likely to carry revolving balances and, conditional on borrowing, hold significantly higher debt levels, even after controlling for income, demographics, and credit constraints. Similarly, Navarro-Martinez et al. (2011) show that repayment decisions are highly sensitive to how credit card information is framed. Their experimental and field evidence from U.S. and U.K. consumers shows that emphasizing minimum required payments anchors repayment behavior, leading borrowers to make lower payments than they otherwise would. Raising the minimum requirement tends to increase repayments for most consumers, but this adjustment does not fully offset the anchoring effect, while supplemental disclosures, such as interest costs or repayment duration, fail to improve repayment outcomes. These results suggest the critical role of framing and information design in shaping debt dynamics.

More recent work suggests the central role of overconfidence and related biases in household financial decisions. Lawrence et al. (2024) show that gender differences in overconfidence are closely linked to variation in financial literacy and financial outcomes, while Xu et al. (2024) disentangle “hubris” from “talent” in Chinese households’ investment decisions, documenting how overconfidence shapes portfolio choices. Together, these findings reinforce the idea that even financially sophisticated households may display biased beliefs, which is consistent with our distinction between leverage-consistent and bias-consistent borrowing among affluent clients.

Recent work has deepened this view by examining interactions between biases and household structure. Vihriälä (2025) investigates how intra-household frictions and anchoring contribute to the credit card debt puzzle: the co-holding of high-cost debt and low-yield liquid assets. He finds that couples co-hold 42% more relative to income when considered jointly than as individuals, and that they often fail to cooperate in reducing costly debt, showing coordination frictions. Moreover, anchoring to minimum payments emerges as a key mechanism: individuals who regularly pay only the minimum, or amounts close to it, account for 59% of individual co-holding. Both household frictions and repayment anchors thus sustain inefficient debt positions.

Another influential line of research showcases exponential growth bias, the tendency to linearize exponential functions when intuitively assessing them. Stango and Zinman (2009) show that households affected by this bias systematically underestimate interest rates and future values, which leads them to borrow more, save less, and prefer shorter maturities. More-biased households also make greater use of financial advice, even after controlling for sophistication and demographics. These findings provide compelling evidence of bias-driven debt, complementing our previous results (Da Silva et al., 2018) that link low CRT scores to higher borrowing costs.

A related set of studies emphasizes the consequences of miscalibrated beliefs about repayment capacity. Consumers often underestimate the likelihood of income shortfalls or overestimate their ability to manage repayment, producing borrowing patterns that may appear rational ex ante but ultimately result in arrears or costly refinancing ex post. Evidence from the U.K. reinforces this view: Gathergood (2012) shows that self-control problems and limited financial literacy are strongly associated with over-indebtedness. Individuals with poor self-control are more likely to miss payments, report excessive debt burdens, and rely on quick-access but high-cost credit products such as store cards and payday loans. They are also disproportionately exposed to income shocks, credit withdrawals, and unforeseen durable expenses, suggesting that self-control deficits magnify vulnerability to financial risk. Across most specifications, the role of self-control proves more powerful than financial illiteracy in explaining over-indebtedness, with direct implications for consumer credit policy.

More recent work on digital credit extends these concerns to online and fintech-mediated borrowing. Studies of mobile loans and digital finance show that, while new technologies expand access and can improve households’ resilience to shocks, they may also expose borrowers to debt traps when credit is easily accessible and weakly monitored (Suri et al., 2021; Yue et al., 2022). Complementary evidence from online consumer credit indicates that attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioral control are central determinants of internet credit use and repayment, emphasizing the behavioral channels through which digital credit markets operate (Zhao et al., 2022). New “buy now, pay later” arrangements similarly illustrate how low-friction installment products can increase online spending and shift the composition of debt toward easily accessible point-of-sale credit (Kumar et al., 2024).

At the same time, recent work has recognized the interaction between cognitive biases and institutional structures. Features such as default settings, disclosure formats, and pricing mechanisms can either amplify or dampen the behavioral distortions documented above. In our context, the grace period offered to high-income borrowers provides a natural institutional test: if borrowing is bias-driven, grace terms should be irrelevant, but if leverage-driven, repayment should respond systematically to cost incentives. Research on choice architecture in financial products supports this line of reasoning, with Bertrand and Morse (2011) showing that redesigned disclosure formats in payday lending markets alter repayment behavior and overall debt burdens.

Taken together, this literature suggests that borrowing behavior cannot be fully explained by rational intertemporal optimization. Time preferences, repayment anchors, exponential growth bias, and self-control deficits all drive patterns of borrowing, repayment, and over-indebtedness. Yet a key question remains underexplored: do these mechanisms operate similarly among affluent consumers, whose financial environments and institutional treatment more closely resemble those of firms? Existing studies tend to assume consumer indebtedness is uniformly bias-driven or to treat income as irrelevant (Dick & Jaroszek, 2014). This oversight constitutes a gap in the literature. By integrating behavioral and institutional perspectives, our approach identifies conditions under which debt reflects leverage rather than behavioral bias. If high-income debt is indeed a hybrid phenomenon (rational leverage for some, bias-driven for others), then corrective intervention, financial regulation, disclosure policies, and risk assessment must recognize this heterogeneity rather than relying on one-size-fits-all assumptions about consumer non-rationality.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Initial Research Steps

The present study was conceived as a continuation of earlier work on high-income consumer indebtedness (Da Silva et al., 2018), where a puzzle was left unresolved: to what extent does debt among affluent consumers reflect rational leverage vs. cognitive biases? To initiate this follow-up, we employed a mixed strategy that combined traditional empirical analysis with computational assistance.

We first articulated the leverage-vs.-bias research question in an initial prompt to a large language model, asking whether high-income debt should be interpreted as firm-like leverage or as the outcome of cognitive biases. To pursue this inquiry, we assembled two key inputs: (1) the published paper (Da Silva et al., 2018) containing the experimental dataset design, fieldwork details, and previously reported statistical analyses, and (2) a catalog of cognitive biases from Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_cognitive_biases; accessed on 1 November 2025) to guide bias detection and to construct a systematic “bias dictionary” for interpreting the data. These materials were then processed with ChatGPT 5 as an analytic assistant to identify which biases were empirically tractable, ensuring that subsequent statistical tests focused on mechanisms most consistent with the available evidence. The LLM was instructed to (1) identify which biases the dataset could plausibly reveal; (2) propose testable signatures of those biases; and (3) recommend an empirical strategy to disentangle leverage from bias-driven borrowing. This methodological dialog provided the framework for the present study, particularly in operationalizing the detected cognitive biases within the constraints of the available dataset.

2.2. Data

The empirical analysis for this follow-up study draws on the dataset originally assembled in our previous work. This is available at https://figshare.com/s/ff9353c0814944131d99. The fieldwork was conducted between 30 March and 29 April 2016, using online questionnaires distributed by one of the authors (A.L.B.), who worked as a personal banker, to clients with monthly earnings exceeding 10,000 Brazilian reais. Out of 329 invited participants, 212 completed the questionnaire, and 149 provided valid responses after applying timing and familiarity filters for the CRT. Importantly, the sample consists exclusively of high-income retail clients holding personal (individual) accounts; business accounts, including those for self-employed clients, are managed in separate segments by the bank and are not included in this dataset.

The dataset includes: (1) CRT scores, both the original (Frederick, 2005) and alternative versions (Toplak et al., 2014), designed to capture the ability to override intuitive but incorrect answers; (2) debt measures, binary indicators of any debt, overdraft debt, and overall debt (overdraft × non-overdraft), as well as limited detail on debt purpose; (3) demographics of age and gender; (4) institutional context: high-income clients received preferential treatment on overdraft facilities, including a ten-business-day grace period before interest charges accrued, effectively aligning their borrowing terms with those offered to firms.

Of note, the dataset does not include explicit measures of expectations, subjective confidence, or forward-looking income beliefs. This absence requires that biases be inferred indirectly from observed borrowing patterns, arrears (when available), and their relation to CRT performance.

2.3. Bias Dictionary and Hypotheses

Guided by the uploaded catalog of cognitive biases, we constructed a bias dictionary to translate theoretical constructs into observable patterns in the dataset. ChatGPT 5’s analysis of the dataset pointed to optimism bias and overconfidence as the most relevant cognitive biases. These biases appear to be the primary candidates for explaining consumer debt in the affluent group in our sample and are empirically tractable with the variables at hand. Optimism bias (Baron, 1994; Hardman, 2009; Sharot, 2011; O’Sullivan, 2015) refers to the systematic underestimation of negative financial outcomes. The testable signature in the dataset is high-income consumers who are indebted and display arrears or costly overdraft use despite strong CRT performance. Overconfidence bias (Lichtenstein et al., 1982; Pallier et al., 2002; Moore & Healy, 2008) refers to the tendency to overrate one’s knowledge or control. Testable signature in the dataset: indebted respondents with high CRT scores but evidence of misaligned borrowing (for example, short-term debt accumulation inconsistent with repayment ability).

Of note, in the mixed-income sample (Da Silva et al., 2018), present bias (O’Donoghue & Rabin, 1999) was identified as the relevant cognitive bias (as in Meier & Sprenger, 2010). This bias refers to the overweighting of immediate consumption over future costs. The testable signature is that lower CRT scores are associated with overdraft use or costly short-term debt.

These operational definitions ground the two hypotheses articulated in the Introduction: that high-income debt reflects primarily leverage (Hypothesis 1) but that a subset of affluent borrowers display patterns consistent with cognitive biases (Hypothesis 2).

Regarding sensitivity to bias definitions, we assess the robustness of the classification by re-labeling the affluent, indebted sample (N = 149) under two alternative rules. First, define low CRT as the bottom tercile of the CRT distribution rather than below the sample median. Second, require overdraft use to satisfy the short-term debt criterion for a bias label, with arrears (late payment or delinquency), when available, retained as an additional signal. For each alternative, we recompute the bias-consistent and leverage-consistent labels and the corresponding class shares.

We also consider uncertainty and stability criteria. For each alternative, uncertainty in the class shares is quantified using bootstrap resampling with replacement: 5000 draws, resample size equal to N, fixed random seed for reproducibility, and 95% percentile confidence intervals. Stability is judged against three pre-specified criteria: (1) the leverage-consistent group remains the majority; (2) the 95% confidence intervals for the alternative shares overlap those from the main specification; and (3) agreement between the alternative labels and the main labels, measured as the fraction of respondents assigned to the same class under both rules, is at least 0.75. Meeting these criteria indicates that the conclusion is robust to reasonable changes in how the labels are defined.

2.4. Empirical Strategy

To test the hypotheses, we adopt a three-step empirical approach. First, we estimate logistic regressions of debt outcomes on CRT scores in the high-income sample, controlling for age and gender. This identifies whether indebtedness among the affluent is associated with poorer cognitive reflection or, instead, appears unrelated to bias.

Second, we supplement the regressions with a rule-based classification approach inspired by finite-mixture modeling. Among the affluent, indebted respondents are sorted into two groups: (1) a leverage-consistent class, characterized by debt coexisting with relatively high CRT performance, fewer arrears, and sensitivity to institutional cost structures, and (2) a bias-consistent class, characterized by debt despite high CRT scores, often accompanied by overdraft use or arrears. This provides a pragmatic way to capture heterogeneity in borrowing behavior within the high-income sample.

Third, within the affluent sample, we implement a cost-sensitivity test to capture institutional influences. Specifically, we estimate whether overdraft use is lower among clients covered by the ten-day overdraft grace period. Under leverage-consistent behavior, overdraft incidence should decline when borrowing costs fall; under bias-driven behavior, grace terms would have little or no effect.

Regarding the identification of the grace-period effect, to reduce possible selection into the grace-period condition, we estimate stabilized inverse-probability weights using a logistic regression that predicts assignment to the grace period from age, age squared, gender, and the CRT score. We trim extreme predicted probabilities (below 0.05 or above 0.95) and then verify covariate balance, targeting standardized mean differences below 0.10. We report the average effect for those who receive the grace period using inverse-probability weighting. As robustness, we also present results from doubly robust augmented inverse-probability weighting and from nearest-neighbor matching with a 0.2 caliper on the log-odds of the propensity score.

Because the grace period is an institutional policy applied in the market, it serves as a market-generated quasi-experiment: if borrowing is rational and cost-sensitive, overdraft use should decline under grace; if bias-driven, grace should have little to no effect.

As for bias operationalization, the available indicators are CRT (standard and expanded items), any debt, overdraft (checking-account credit), arrears (when available), age, gender, and the grace-period institutional feature. Again, because the dataset lacks direct measures of expectations or subjective confidence, the evidence for bias is indirect, inferred from observable borrowing signatures. Among affluent respondents with debt, cases are labeled bias-consistent when they show overdraft or arrears and have a high CRT score (≥sample median). All other indebted cases are labeled leverage-consistent. This rule reproduces the ≈80.4% (leverage-consistent) and 19.6% (bias-consistent) shares reported.

We construct a composite index that aggregates four binary signals of potentially bias-consistent borrowing. The Bias Risk Score is

BRS = 0.40·I[overdraft] + 0.30·I[arrears] + 0.20·I[any debt] + 0.10·I[CRT ≥ median].

Here, I[·] denotes an indicator that equals 1 when the condition holds, and 0 otherwise. The components are defined as overdraft = 1 if the respondent reports using checking-account credit; arrears = 1 if late payment/delinquency is reported (when available); any debt = 1 if the respondent holds any form of debt; CRT ≥ median = 1 if the respondent’s CRT score is at or above the sample median. The weights (0.40, 0.30, 0.20, 0.10) sum to 1, so BRS ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating a stronger concentration of costly or misaligned short-term borrowing (overdraft/arrears) conditional on higher cognitive reflection. We report mean BRS by class (leverage-consistent vs. bias-consistent) and conduct sensitivity analyses that (1) assign equal weights to all components, and (2) replace the median split with CRT terciles.

Class proportions (leverage-consistent and bias-consistent) and the mean BRS are quantified using bootstrap resampling with 1000–5000 draws with replacement and a fixed random seed for reproducibility. For each statistic, the distribution of bootstrap estimates is summarized with 95% confidence intervals (percentile method). Results are presented alongside the observed (non-bootstrap) estimates to show sampling uncertainty and dispersion.

Descriptive diagnostics examine how the bias label and the BRS vary with respondent characteristics. The bias label (binary) is modeled with logistic regression on the CRT score, age, gender, and the interactions CRT × age and CRT × gender; the BRS (continuous) is modeled with ordinary least squares on the same set of predictors. Estimates are interpreted descriptively, not causally. We report coefficients and, when helpful, average marginal effects with robust standard errors to aid interpretation.

A key limitation is the lack of direct measures of expectations or subjective confidence in the dataset. As a result, the identification of psychological bias is operational and relies on observable borrowing signatures. Findings are therefore described as patterns consistent with optimism bias and overconfidence, rather than as direct measurements of those biases.

2.5. Equivalence Testing for CRT Effects

To assess whether CRT effects are practically negligible, we conduct two one-sided tests on the log-odds coefficient of CRT. We pre-specify equivalence bounds as ±ln(1.25) (odds ratios between 0.80 and 1.25 represent “no economically meaningful effect”), and we report 90% confidence intervals with robust standard errors. As a sensitivity, we also report bounds at ±ln(1.20).

2.6. Robustness Check

As a robustness check, we estimate a two-class latent class model on the sample of affluent, indebted respondents (N = 149), using three binary indicators as manifest variables: overdraft (uses checking-account credit), arrears (reports late payment or delinquency; included when available), and high CRT score (at or above the sample median). The model is estimated by maximum likelihood with the standard expectation–maximization procedure and multiple random starting values to reduce the risk of local optima. Identification is achieved through conventional constraints on item response probabilities (effect-coding style constraints for binary indicators).

For each respondent, the model yields probabilities of membership in each latent group. We present: (1) the probability-weighted share of each class (averaging the membership probabilities across individuals), and (2) a hard assignment that labels respondents by the highest membership probability. To make the labeling transparent, we flag ambiguous assignments where the highest probability is below 0.60. We then compare these latent-class labels with our rule-based labels by reporting an agreement table (confusion matrix), percentage agreement, and Cohen’s kappa coefficient (a chance-corrected agreement statistic). Close agreement and similar class shares strengthen the interpretation that our main results do not hinge on the manual rule. We judge the adequacy of a two-class structure by interpretability, similarity of class shares to the rule-based split, and stability under alternative thresholds and bootstrap uncertainty; the exploratory three-class solution does not introduce a coherent new behavior.

As an additional sensitivity analysis, we fit an exploratory three-class model using the same indicators and estimation settings and compare class sizes and interpretability. Given the modest sample size and the binary nature of the indicators, we treat the latent-class analysis as confirmatory robustness rather than a replacement for the primary rule-based approach. Our conclusions about a majority leverage-consistent group and a minority bias-consistent group are based on the full set of methods described above.

2.7. AI Assistance and Reproducibility

As observed, we used an LLM (ChatGPT 5) to structure the bias-testing workflow, draft alternative phrasings, and cross-check our interpretation and organization of literature that had been identified by the authors through conventional database searches. The literature search and selection themselves were carried out manually by the authors; ChatGPT was not used as a literature search engine. Statistical analyses, code, and classification rules were designed and executed by the authors; no data were generated, altered, or imputed by AI. We logged the main prompts and versions, and manually verified all factual claims and references to avoid fabricated citations.

We include three elements to make our AI use auditable and reusable. First, representative prompts: for example, “Outline a workflow to test for behavioral bias using the available variables (CRT score, overdraft use, arrears, age, and gender) and propose robustness checks, including bootstrap-based confidence intervals, inverse-probability weighting (and its doubly robust augmented form), and latent class analysis”; “Rewrite the following paragraph for clarity without altering any numerical values or claims”; and “List policy framings consistent with institutional cost sensitivity while flagging any statements that would require direct measures of expectations”.

Second, we used OpenAI’s conversational large language model (model tag: GPT-5 Thinking) via the ChatGPT web interface on 30 October 2025. Decoding settings were left at their defaults; in ChatGPT web, temperature and top-p are not user-configurable.

Third, a verification checklist applied before accepting any AI suggestion: all statistics were re-computed from our code; tables/figures were regenerated and compared against pre-AI baselines; every cited reference was checked for existence, stable DOI, and correct metadata; quotations and numerical claims were spot-verified against primary sources; wording edits were diff-checked to ensure no change in scientific meaning or numbers; and we maintained a prompt → draft → author decision change log documenting acceptance, revision, or rejection.

3. Results

3.1. CRT and Debt Among the Affluent

In the high-income sample, the logit regression of debt incidence on CRT (with controls for age and gender) produced a coefficient close to zero and nonsignificant (β = 0.036, SE = 0.097, z = 0.368, p = 0.713). Higher cognitive reflection neither protected against indebtedness nor substantially increased it. This absence of a bias-consistent relationship supports the interpretation of debt as rational leverage among affluent consumers.

For any debt, the CRT coefficient’s 90% confidence interval (CI) on the log-odds scale is [−0.124, 0.196], implying an odds ratio of [0.884, 1.216], which falls inside our equivalence region [0.80, 1.25]. Thus, we accept equivalence (i.e., no economically relevant CRT effect). For overall debt, the 90% CI is [−0.125, 0.205] (odds ratio [0.883, 1.227]), also inside the equivalence region. For overdraft-only, the 90% CI is [−0.529, 0.129] (odds ratio [0.589, 1.138]); at ±25% this does not meet equivalence, but it does at a wider ±50% bound.

3.2. Class Composition: Leverage Vs. Bias

To explore heterogeneity among indebted high-income respondents, we classified borrowers into two categories: bias-consistent (indebted, overdraft use, CRT below the sample median) and leverage-consistent (all others). Results show that 80.4 percent of indebted respondents are leverage-consistent, while only 19.6 percent fall into the bias-consistent group. This indicates that the overwhelming majority of affluent borrowers behave in ways consistent with strategic leverage, although a minority still exhibit borrowing patterns aligned with optimism bias or overconfidence.

Of note, the analysis does not test optimism bias or overconfidence per se; there are no direct measures of expectations or confidence in our dataset. Nevertheless, the bias-consistent group reflects observable signatures, notably overdraft or arrears alongside higher CRT scores, that are consistent with optimism/overconfidence. We therefore describe these findings as patterns consistent with those biases, while the majority group’s behavior is consistent with deliberate, cost-sensitive leverage.

Bootstrap resampling with replacement (5000 draws, resample size equal to the number of affluent, indebted respondents = 49 cases, using a fixed random seed for reproducibility) yields 95% percentile confidence intervals of 74.0–86.8% for the above leverage-consistent share, and 13.2–26.0% for the bias-consistent share. These intervals support the 80.4 percent vs. 19.6 percent pattern reported above and quantify the sampling uncertainty around those estimates.

On the affluent, indebted subsample (N = 149), we estimated a two-class latent class model using three binary indicators: overdraft use, arrears (late payment or delinquency, when available), and high CRT score (at or above the sample median). The two classes map cleanly onto our substantive labels: one class shows a low incidence of overdraft and arrears and aligns with leverage-consistent behavior. The other shows a higher incidence of overdraft and arrears conditional on high CRT scores and aligns with bias-consistent behavior. Using the model’s posterior membership probabilities, both the probability-weighted class shares and the hard-assignment shares (assigning each respondent to the class with the highest posterior probability) remain close to the 80.4 percent vs. 19.6 percent split reported for the rule-based scheme. Agreement between latent-class labels and rule-based labels, summarized by a confusion matrix, percentage agreement, and Cohen’s kappa, confirms that the main conclusion does not depend on manual labeling.

Why two clusters? Our hypotheses posit two mechanisms (leverage and bias), so a two-class structure is the natural starting point. Empirically, the latent-class solution mirrors the rule-based split and delivers similar class shares, and the exploratory three-class run does not reveal a new, interpretable behavioral type. Instead, the additional class partitions are the leverage group without a distinct indicator pattern. Stability checks (alternative label thresholds and bootstrap uncertainty) preserve the majority leverage share and high agreement with the main labels. Given the binary indicators, modest sample, and our emphasis on interpretability, we retain two clusters.

As for sensitivity to alternative labels, redefining low CRT as the bottom tercile (rather than below the median) and requiring overdraft use (rather than any debt) to flag bias leaves the leverage-consistent group as the majority among affluent, indebted respondents. Uncertainty, quantified via bootstrap resampling with replacement (5000 draws, resample size N = 149, using a fixed random seed for reproducibility), yields 95% percentile confidence intervals for the alternative shares that overlap the main-specification intervals (leverage-consistent: 74.0–86.8%; bias-consistent: 13.2–26.0%). Agreement between the alternative labels and the main rule-based labels is high (≥0.75), indicating that the leverage-majority conclusion is robust to these threshold changes.

3.3. Institutional Cost Sensitivity: Grace Period Test

To assess whether borrowing among the affluent responds to institutional cost structures, we estimated a logistic regression of overdraft use on the grace-period dummy (equal to 1 for high-income clients covered by the ten-business-day overdraft window). Results show that overdraft incidence is substantially lower under grace: β = −1.2069, SE = 0.2474, z = −4.879, p < 0.001, corresponding to an odds ratio of 0.299. In substantive terms, the predicted probability of overdraft falls from 0.661 for clients without grace to 0.368 for those with grace.

As a robustness check, adding age and gender as controls leaves the conclusion unchanged, though less precisely estimated (β = −0.6686, SE = 0.3595, p = 0.063).

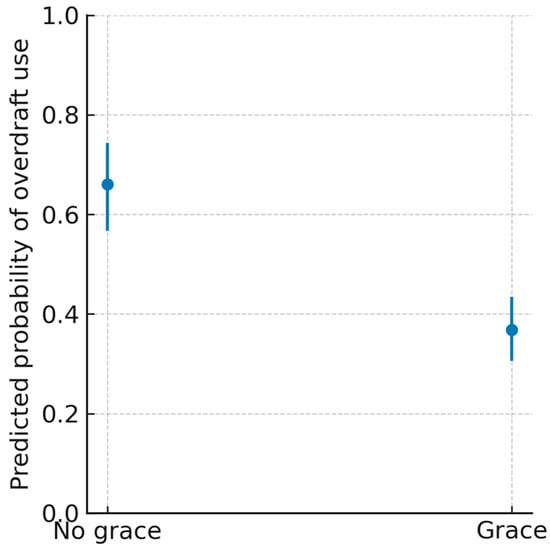

Taken together, these results indicate that the grace period sharply reduces baseline overdraft incidence, consistent with leverage-like, cost-sensitive borrowing among the affluent. See Table 1 and Figure 1.

Table 1.

Logistic regression of overdraft use in the grace period. This model tests whether the ten-business-day overdraft grace period offered to high-income clients reduces overdraft use. The “Grace Only” specification shows a large and statistically significant reduction in overdraft incidence under grace. The “Grace + Controls” specification, which adjusts for age and gender, yields a similar but less precisely estimated effect.

Figure 1.

Predicted probability of overdraft use by grace-period status. Estimates from the logistic regression of overdraft use on the grace period only. Clients without grace have a predicted probability of 0.66, compared to 0.37 under grace. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 1 shows a large drop in the predicted probability of overdraft under the grace-period condition (0.66 without grace vs. 0.37 with grace, with 95% confidence intervals), which is consistent with cost-sensitive, rational borrowing. Why does a grace period reduce overdraft? The grace window creates a kinked cost schedule: borrowing is free up to ten business days but becomes strictly positive thereafter. Price-sensitive borrowers therefore manage liquidity to remain on the free side of the kink, using the bank’s float briefly and then repaying or sweeping funds in before interest accrues. An overdraft is recorded only when the account stays negative beyond the grace window or otherwise triggers interest charges. Short, within-window negatives that are cleared on time are not classified as overdraft. As a result, the grace period promotes just-in-time repayment and reduces the frequency with which balances enter the interest-bearing state, which is exactly what a leverage-based explanation predicts.

To check robustness, we re-estimated predicted probabilities using stabilized inverse-probability weights that model assignment to grace as a function of age, age squared, gender, and CRT score. After trimming extreme propensities (0.05–0.95), covariate balance met conventional standards (all standardized mean differences below 0.10). The weighted estimates reinforce the same conclusion: the probability of overdraft remains substantially lower under grace, with a direction and magnitude similar to the unweighted 0.66 to 0.37 pattern and statistically distinguishable at conventional levels. This evidence strengthens the policy interpretation that making short-term credit costs salient and temporarily lower reduces overdraft use among affluent borrowers. And given that the sample is restricted to affluent retail clients with personal accounts rather than business accounts, this cost sensitivity is best interpreted as a household-level response rather than as small-business financing behavior.

3.4. Robustness Checks

A series of robustness checks reinforces the main conclusion that high-income debt is not driven by low cognitive reflection.

First, we can consider alternative CRT items (Toplak et al., 2014). Substituting the expanded CRT battery for the standard items produced coefficients that remained small and nonsignificant in the high-income sample (β = 0.04, SE = 0.10, z = 0.41, p = 0.68). This confirms that indebtedness among the affluent is not associated with weaker cognitive reflection regardless of the CRT variant used.

Second, debt definitions. When overdraft use alone was taken as the dependent variable, the CRT coefficient was again near zero and nonsignificant (β = −0.20, SE = 0.20, z = −0.98, p = 0.33). Using overall debt incidence, the coefficient was positive but small and statistically nonsignificant (β = 0.04, SE = 0.10, z = 0.37, p = 0.71). In both specifications, there is no evidence that poorer cognitive reflection predicts debt among high-income consumers.

Finally, gender controls. Male respondents scored significantly higher on the CRT (β = 0.52, SE = 0.12, t = 4.33, p < 0.001), consistent with prior literature (Frederick, 2005). (Frederick explicitly reports gender differences in CRT performance: men scored significantly higher than women. In his dataset of 3428 respondents, mean CRT scores were 1.47 for men and 1.03 for women, with the difference highly significant (p < 0.0001)). However, adding gender as a covariate in debt regressions did not alter the main findings: the CRT–debt relationship in the high-income sample remained statistically indistinguishable from zero.

3.5. Summary

The evidence points clearly to Hypothesis 1: debt among the affluent is not explained by poor cognitive reflection but aligns with leverage-consistent behavior. Most high-income borrowers (about 80 percent) use credit strategically, and overdraft incidence responds to institutional cost features such as grace periods. Still, a minority (about 20 percent) display bias-consistent borrowing, consistent with Hypothesis 2: optimism bias and overconfidence persist even in wealthy populations.

4. Discussion

Affluent borrowers in our data disproportionately exhibit optimism bias and overconfidence, precisely the traits that Kahneman (2011, Chapter 24) identifies as the psychological “engine of capitalism.” These dispositions encourage entrepreneurial entry and bold investment even when average returns are negative, thereby propelling economic dynamism while simultaneously imposing costs on many individuals (Cooper et al., 1988; Busenitz & Barney, 1997; Åstebro, 2003; Åstebro & Elhedhli, 2006). The same biases are visible in managerial decision-making, where overconfident CEOs are more likely to pursue value-destroying mergers or earnings manipulation (Roll, 1986; Malmendier & Tate, 2008, 2009). Optimism has also been shown to shape individual economic choices and new venture performance (Puri & Robinson, 2007; Windschitl et al., 2008), while competition neglect and above-average beliefs further illustrate the systematic nature of these biases (Williams & Gilovich, 2008; Simonsohn, 2010). Viewed in this light, our results suggest that high-income consumers in the dataset, those who display optimism bias and overconfidence, are not merely vulnerable to costly misjudgments but are also the very actors most inclined to drive the capitalist engine forward (Kahneman & Lovallo, 1993; Hayward et al., 2006).

The results of this study suggest that consumer indebtedness is not monolithic but instead reflects heterogeneity across income groups. For the general population, borrowing patterns are consistent with bias-driven behavior, particularly self-control problems and present bias (Da Silva et al., 2018), echoing the findings of Meier and Sprenger (2010), who link present bias to costly credit card debt, and Stango and Zinman (2009), who show that exponential growth bias predicts greater borrowing and financial mistakes. More recent evidence from Spain and Malaysia supports this picture: self-control problems and other behavioral biases are strongly associated with higher consumer indebtedness and difficulties managing revolving credit (Fernández-López et al., 2024; Hamid, 2025). In parallel, the emergence of online consumer credit and “buy now, pay later” products shows how streamlined digital borrowing channels can interact with these same biases, increasing spending and shifting debt toward short-term, easily accessible credit (Zhao et al., 2022; Kumar et al., 2024). Complementary evidence on ‘buy now, pay later’ products suggests that psychological factors such as impulsivity, present bias, and social norms are key determinants of “buy now, pay later” use (Relja et al., 2024), suggesting that new digital channels often amplify the same behavioral mechanisms we identify in more traditional overdraft credit.

By contrast, for high-income consumers, the association between debt and cognitive reflection disappears or even reverses. This suggests that affluent borrowers engage in leverage-consistent behavior, comparable to firms strategically using credit for liquidity management (Da Silva et al., 2018). However, this study suggests that a non-trivial subset of high-income borrowers falls into a bias-consistent class. This nuance is crucial: while present bias appears muted among the affluent, optimism bias and overconfidence remain detectable, indicating that some high-income consumers may underestimate liquidity risks or overrate their financial acumen.

The role of institutional context also emerges as pivotal. The overdraft grace period granted to high-income clients effectively lowers the marginal cost of borrowing, aligning consumer credit conditions more closely with corporate financing structures. Our findings that overdraft borrowing declines substantially under grace conditions (predicted probability falling from 66% to 37%) bolster the interpretation of leverage-like, cost-sensitive behavior. We interpret the grace-period evidence as a natural test of rationality: the large drop in predicted overdraft under grace (from 0.66 to 0.37) indicates cost-sensitive behavior among the affluent.

These findings carry theoretical implications. They call for an expanded framework in behavioral household finance that allows for heterogeneity by income and institutional treatment, rather than assuming uniform bias effects. They also suggest the importance of distinguishing between different biases: whereas present bias dominates in mixed-income populations, optimism and overconfidence may persist among the affluent.

There are also policy implications. For the general population, where present bias and limited cognitive reflection are more prevalent, measures such as financial literacy campaigns or repayment nudges may help mitigate bias-driven borrowing. Among high-income consumers, most borrowing appears leverage-consistent, but regulation should still combine safeguards for deliberate leverage with measures that address optimism bias and overconfidence, which continue to affect a minority of affluent borrowers.

This heterogeneity rules out one-size-fits-all interventions. For the general population, where present bias and weaker CRT are more prevalent, regulatory and educational tools should target self-control problems and cost salience (transparent pricing frames and delayed-reward training). For high-income consumers, oversight should combine safeguards for deliberate leverage management (such as monitoring sensitivity to short-term credit costs and disclosure rules that preserve rational price responses) with targeted measures addressing optimism bias and overconfidence, identified here as the residual source of risk. For high-income consumers, behavioral and institutional tools should operate jointly, pairing clear cost-salience measures with oversight that preserves price responsiveness, so that even borrowers showing bias-consistent patterns do not create vulnerabilities for themselves or the financial system.

Finally, a brief methodological note. In its automatic mode (System 1 thinking), the mind displays hostility to algorithms (Kahneman, 2011, Chapter 21). This helps explain what Schilke and Reimann (2025) describe as the “transparency dilemma,” whereby disclosure of AI involvement can paradoxically erode trust in research outputs. In this study, we take the calculated risk of such credibility costs: we disclose our use of an AI-assisted methodology for detecting biases and structuring research steps, on the premise that the benefits of rigor and systematicity outweigh the potential downsides.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

This study asks whether debt among high-income consumers reflects rational leverage, comparable to firms, or the influence of cognitive biases. Using logistic regressions and a rule-based classification inspired by finite-mixture modeling, we find clear heterogeneity: among the affluent, most borrowing is leverage-consistent, while a minority shows bias-consistent patterns indicative of optimism bias and overconfidence. Our contribution is analytical, combining a finite-mixture-inspired rule-based classification with an institutional cost-sensitivity test of the grace period, applied to an existing dataset; together, these tools separate leverage from bias-driven borrowing among the affluent.

In our earlier work (Da Silva et al., 2018), evidence from a mixed-income sample showed that debt was consistently associated with poorer CRT performance. Borrowing behavior in that context was best explained by self-control problems and present bias, whereby individuals overvalue immediate consumption relative to future costs. This pattern reinforced the link between low cognitive reflection and bias-driven borrowing.

The same study also examined affluent consumers, where the negative CRT–debt relationship disappeared and, in some specifications, was even reversed. This suggested that higher cognitive reflection was not protective against indebtedness and that debt in this group might align more closely with leverage, aided by institutional practices such as overdraft grace periods. However, the analysis left a key question unresolved: do high-income borrowers exclusively display leverage-consistent behavior, or do they also exhibit cognitive biases? The present paper directly addresses this issue by disentangling leverage-driven from bias-driven borrowing within the affluent sample.

Our analysis confirms that a non-trivial subset of high-income borrowers remains bias-consistent. Even in environments of financial privilege and favorable institutional terms, some respondents exhibit borrowing patterns consistent with optimism bias and overconfidence: expectations of future repayment capacity that do not always materialize, or there may be an overestimation of control over financial risks. By contrast, present bias appears less influential among high-income borrowers, suggesting that behavioral mechanisms do not apply uniformly across socioeconomic groups.

These findings contribute to the literature in two ways. First, they suggest that consumer debt cannot be explained by a single mechanism. In the general population, present bias and limited cognitive reflection are central drivers of borrowing, whereas among the affluent, most debt reflects leverage-consistent reasoning, with optimism bias and overconfidence affecting only a minority. Second, they emphasize the role of institutional context, such as overdraft pricing structures and grace periods, in shaping borrowing behavior. Together, these insights call for theoretical and policy frameworks that recognize heterogeneity not only between households and firms but also within different segments of the household sector.

While this study advances the understanding of heterogeneity in consumer debt, several limitations point to opportunities for future research. Our dataset does not contain direct measures of expectations, confidence, or purpose of debt, which constrained the identification of optimism bias and overconfidence to indirect signatures such as arrears or costly overdraft reliance. Adding survey items on income forecasts, repayment expectations, and subjective probability calibration would allow for sharper tests of optimism bias and overconfidence and could also make it possible to identify other relevant biases that remain unobserved in the current dataset. Similarly, asking respondents to report whether debt was taken for consumption smoothing, investment, or precautionary motives would help distinguish leverage from bias-driven borrowing more precisely. At the same time, it is precisely the absence of these direct measures that justifies the AI-assisted methodology adopted here, which leverages structured prompts and bias dictionaries to extract behavioral signatures from an otherwise limited dataset. A further limitation is the modest sample size (N = 149, with N = 49 in some subgroup analyses) and the fact that the fieldwork took place in 2016. While the key findings, such as the strong grace-period effect and the equivalence-tested absence of a meaningful CRT–debt relationship among the affluent, are statistically robust, the exact subgroup shares and the external validity to today’s credit environment should be interpreted with caution.

Experimental approaches could further complement observational data. For example, incentivized calibration tasks could measure misalignment between confidence and actual performance, while temporal discounting experiments could quantify present bias directly rather than through CRT proxies. Finally, linking survey data with bank account or credit bureau records would allow researchers to validate self-reported arrears and track how institutional features such as grace periods alter actual repayment behavior.

By integrating richer data into future studies, it is possible to construct a more comprehensive taxonomy of debt determinants: one that identifies not only when consumers behave like firms, but also when cognitive biases continue to shape borrowing decisions despite high income and financial sophistication.

Borrower heterogeneity rules out uniform interventions. For the general population, where present bias and lower CRT performance are more common, behavioral measures that raise awareness of credit costs and strengthen self-control should be emphasized, including transparent pricing, plain-language disclosures, and training that builds patience and planning. For high-income consumers, oversights that preserve rational responses to price, such as monitoring sensitivity to short-term credit costs and clear disclosure rules, should be combined with targeted safeguards addressing optimism bias and overconfidence. This joint approach uses behavioral tools for the many and governance tools for the affluent minority, reducing the risk that bias-driven borrowing harms individuals or the financial system.

In summary, the results suggest that debt at the top of the income distribution is best understood as a hybrid phenomenon: predominantly leverage, but with a meaningful minority of cases still shaped by cognitive biases. Future research should deepen this line of inquiry by incorporating direct measures of expectations, confidence, and borrowing purpose, thereby refining the mapping between bias signatures and observable financial behavior.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.D.S. and A.L.B.; methodology, S.D.S., M.Z.S., A.L.B.; software, R.M. and S.D.S.; validation, M.Z.S., A.L.B. and R.M.; formal analysis, S.D.S. and R.M.; investigation, A.L.B. and S.D.S.; resources, M.Z.S., A.L.B., S.D.S. and R.M.; data curation, M.Z.S., A.L.B. and R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.D.S.; writing—review and editing, S.D.S.; visualization, A.L.B. and R.M.; supervision, M.Z.S. and S.D.S.; project administration, M.Z.S. and A.L.B.; funding acquisition, M.Z.S., S.D.S. and R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by CNPq [Grant number: PQ 2 301879/2022-2 (S.D.S.) and PQ2 311548/2022-9 (R.M.)], Capes [Grant number: PPG 001 (S.D.S. and R.M.)], and FAPESC (M.Z.S.). The APC was funded by S.D.S., A.L.B., M.Z.S. and R.M.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study uses previously collected survey data from a project approved by the National Research Ethics Committee at Plataforma Brasil (Grant No. 10398419.7.0000.0121).

Informed Consent Statement

In the original study from which these data were obtained, informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is available at https://figshare.com/s/ff9353c0814944131d99 (accessed on 1 November 2025) and the code for replication is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30510305.v2 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

Acknowledgments

During manuscript preparation, we used ChatGPT (OpenAI; model tag GPT-5 Thinking, accessed 30 October 2025 via the ChatGPT web interface) to help outline the bias-testing workflow, refine wording, and check reference formatting. Statistical analyses, code, and classification rules were designed and executed by the authors; no data were generated, altered, or imputed by AI. All AI-assisted text was reviewed, verified, and edited by the authors, who take full responsibility for the content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Åstebro, T. (2003). The return to independent invention: Evidence of unrealistic optimism, risk seeking or skewness loving? The Economic Journal, 113, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åstebro, T., & Elhedhli, S. (2006). The effectiveness of simple decision heuristics: Forecasting commercial success for early-stage ventures. Management Science, 52, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, J. (1994). Thinking and deciding (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, M., & Morse, A. (2011). Information disclosure, cognitive biases, and payday borrowing. Journal of Finance, 66, 1865–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busenitz, L. W., & Barney, J. B. (1997). Differences between entrepreneurs and managers in large organizations: Biases and heuristics in strategic decision making. Journal of Business Venturing, 12, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J. Y. (2006). Household finance. Journal of Finance, 61, 1553–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A. C., Woo, C. Y., & Dunkelberg, W. C. (1988). Entrepreneurs’ perceived chances for success. Journal of Business Venturing, 3, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, S., Da Costa, N., Jr., Matsushita, R., Vieira, C., Correa, A., & De Faveri, D. (2018). Debt of high-income consumers may reflect leverage rather than poor cognitive reflection. Review of Behavioral Finance, 10, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, S., Gupta, R., & Monzani, D. (Eds.). (2023). Highlights in psychology: Cognitive bias. Frontiers Media SA. [Google Scholar]

- Dick, C. D., & Jaroszek, Ł. (2014, September 7–10). Knowing what not to do: Financial literacy and consumer credit choices. German Economic Association Annual Conference 2014 (No. 100383), Hamburg, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-López, S., Castro-González, S., Rey-Ares, L., & Rodeiro-Pazos, D. (2024). Self-control and debt decisions relationship: Evidence for different credit options. Current Psychology, 43, 340–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, S. (2005). Cognitive reflection and decision making. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathergood, J. (2012). Self-control, financial literacy and consumer over-indebtedness. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33, 590–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, F. S. (2025). Behavioral biases and over-indebtedness in consumer credit: Evidence from Malaysia. Cogent Economics & Finance, 13, 2449191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardman, D. (2009). Judgment and decision making: Psychological perspectives. Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward, M. L. A., Shepherd, D. A., & Griffin, D. (2006). A hubris theory of entrepreneurship. Management Science, 52, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D., & Lovallo, D. (1993). Timid choices and bold forecasts: A cognitive perspective on risk taking. Management Science, 39, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., Slovic, P., & Tversky, A. (Eds.). (1982). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A., Salo, J., & Bezawada, R. (2024). The effects of buy now, pay later (BNPL) on customers’ online purchase behavior. Journal of Retailing, 100, 602–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, C., Nguyen, T., & Wick, R. (2024). Gender difference in overconfidence and household financial literacy. Journal of Banking & Finance, 166, 107237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, S., Fischhoff, B., & Phillips, L. D. (1982). Calibration of probabilities: The state of the art to 1980. In D. Kahneman, P. Slovic, & A. Tversky (Eds.), Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases (pp. 306–334). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2014). The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature, 52, 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmendier, U., & Tate, G. (2008). Who makes acquisitions? CEO overconfidence and the market’s reaction. Journal of Financial Economics, 89, 20–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmendier, U., & Tate, G. (2009). Superstar CEOs. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124, 1593–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, S., & Sprenger, C. (2010). Present-biased preferences and credit card borrowing. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D. A., & Healy, P. J. (2008). The trouble with overconfidence. Psychological Review, 115, 502–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S. C. (1984). The capital structure puzzle. Journal of Finance, 39, 574–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Martinez, D., Salisbury, L. C., Lemon, K. N., Stewart, N., Matthews, W. J., & Harris, A. J. L. (2011). Minimum required payment and supplemental information disclosure effects on consumer debt repayment decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 48(SPL), S60–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, T., & Rabin, M. (1999). Doing it now or later. American Economic Review, 89, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, O. P. (2015). The neural basis of always looking on the bright side. Dialogues in Philosophy, Mental and Neuro Sciences, 8, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Pallier, G., Wilkinson, R., Danthiir, V., Kleitman, S., Knezevic, G., Stankov, L., & Roberts, R. D. (2002). The role of individual differences in the accuracy of confidence judgments. Journal of General Psychology, 129, 257–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, M., & Robinson, D. T. (2007). Optimism and economic choice. Journal of Financial Economics, 86, 71–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relja, R., Ward, P., & Zhao, A. L. (2024). Understanding the psychological determinants of buy-now-pay-later (BNPL) in the UK: A user perspective. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 42, 7–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roll, R. (1986). The hubris hypothesis of corporate takeovers. The Journal of Business, 59, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilke, O., & Reimann, M. (2025). The transparency dilemma: How AI disclosure erodes trust. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 188, 104405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharot, T. (2011). The optimism bias. Current Biology, 21, R941–R945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsohn, U. (2010). eBay’s crowded evenings: Competition neglect in market entry decisions. Management Science, 56, 1060–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stango, V., & Zinman, J. (2009). Exponential growth bias and household finance. Journal of Finance, 64, 2807–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, T., Bharadwaj, P., & Jack, W. (2021). Fintech and household resilience to shocks: Evidence from digital loans in Kenya. Journal of Development Economics, 153, 102697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toplak, M. E., West, R. F., & Stanovich, K. E. (2014). Assessing miserly information processing: An expansion of the cognitive reflection test. Thinking & Reasoning, 20, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vihriälä, E. (2025). Intra-household frictions, anchoring, and the credit card debt puzzle. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 107, 510–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E. F., & Gilovich, T. (2008). Do people really believe they are above average? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44, 1121–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windschitl, P. D., Rose, J. P., Stalkfleet, M. T., & Smith, A. R. (2008). Are people excessive or judicious in their egocentrism? A modeling approach to understanding bias and accuracy in people’s optimism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J., Khraiche, M., Mao, X., & Wang, X. (2024). Hubris or talent? Estimating the role of overconfidence in Chinese households’ investment decisions. International Review of Financial Analysis, 91, 102992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, P., Korkmaz, A. G., Yin, Z., & Zhou, H. (2022). The rise of digital finance: Financial inclusion or debt trap? Finance Research Letters, 47, 102604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H., Peng, H., & Li, W. (2022). Analysis of factors affecting individuals’ online consumer credit behavior: Evidence from China. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 922571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).