Abstract

Background: Pediatric patients often receive medicines manipulated from adult formulations due to a lack of age-appropriate products. While such practices are clinically routine, they may reflect deeper systemic deficiencies in pediatric pharmacotherapy. Objective: This scoping review aimed to map the prevalence, definitions, and types of pediatric drug manipulation and to conceptualize manipulation as an indicator of structural gaps in formulation science, regulation, and access. Methods: A systematic search of PubMed (January 2014–July 2024) included 10 studies reporting the frequency of drug manipulation in children aged ≤18 years. Eligible studies were synthesized narratively according to PRISMA-ScR guidelines. Results: Ten studies from nine countries were included, reporting manipulation frequencies ranging from 6.4% to 62% of all drug administrations and up to 60% at the patient level. Manipulated formulations most commonly included oral solid doses, altered through dispersing, splitting, or crushing. Definitions and methodologies varied considerably. The findings revealed five recurring structural gaps: limited pediatric formulations, inconsistent regulatory implementation, lack of standardized definitions and guidance, insufficient evidence on manipulation safety, and inequitable access across regions. Conclusion: Manipulation of finished dosage forms for use in children is a widespread, measurable phenomenon reflecting systemic inadequacies in formulation development, regulation, and access. Recognizing manipulation as a structural indicator may guide policy, innovation, and equitable pediatric pharmacotherapy worldwide.

1. Introduction

Children constitute a significant proportion of healthcare recipients globally; however, the majority of approved medicines are still primarily developed, tested, and formulated for adults [1]. Despite regulatory incentives from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to promote pediatric-appropriate drug formulations, many medicines still lack commercially available pediatric formulations. Economic and market constraints hinder the development of child-specific formulations, especially for off-patent drugs, meaning that regulatory encouragement alone does not ensure availability of safe, evidence-based pediatric products [2].

As a consequence, pediatric patients often receive drugs in dosages and formulations that are not suited to their physiological, developmental, or therapeutic needs [3,4]. This fundamental mismatch creates a persistent dependency on drug manipulation—the alteration of licensed dosage forms through splitting, crushing, dispersing, or compounding to achieve age-appropriate doses [5].

The pediatric population, as defined in regulatory frameworks, includes individuals from birth to 17 years and is usually stratified into age-based subgroups. The physiological variability of children, including differences in organ maturity, metabolic capacity, and body composition, increases their vulnerability to dosing inaccuracies and adverse drug reactions [6,7,8]. Manipulated medicines may exhibit unpredictable stability, bioavailability, and pharmacokinetics, particularly for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows or modified-release mechanisms [9,10,11,12,13,14]. Consequently, manipulation can lead to both underdosing and overdosing, compromising efficacy and safety across a range of clinical settings [15].

Despite these risks, drug manipulation remains an intrinsic component of pediatric pharmacotherapy. Healthcare professionals routinely alter adult formulations to accommodate pediatric needs, often without manufacturer guidance or evidence-based support [3,6,16]. Studies have shown that tablet splitting, for example, can produce significant dose variability [15], while dispersing or crushing coated or sustained-release preparations can alter absorption and pharmacodynamic profiles [17]. These practices are often undertaken out of necessity rather than choice.

Traditionally, drug manipulation has been viewed as a local workaround—a pragmatic response to the lack of suitable pediatric medicines. However, its ubiquity and persistence across health systems suggest a deeper systemic problem.

Understanding the scope and variation of these practices is therefore critical not only for clinical safety but also for identifying underlying structural barriers to optimal pediatric care. By mapping the prevalence, definitions, and characteristics of pediatric drug manipulation across contexts, this scoping review aims to conceptualize manipulation as a structural metric—a lens through which gaps in formulation science, regulation, and access can be revealed. In this context, a structural metric refers to a measurable phenomenon that reflects underlying system-level properties rather than isolated clinical behaviors. In the context of pediatric pharmacotherapy, drug manipulation serves as such a metric because it is not simply an individual practice, but rather the visible manifestation of deeper structural constraints within health systems, pharmaceutical markets, and regulatory frameworks. Hence, pediatric drug manipulation as a structural metric refers to the use, frequency, and nature of medicine alterations as a quantifiable indicator of system-level deficiencies in the availability, regulation, guidance, and real-world accessibility of age-appropriate formulations.

The primary objective of this study is to determine the frequency of drug manipulation in pediatric care across all healthcare settings. The secondary objectives are to quantify the number of patients receiving manipulated drugs, to characterize the types and formulations of manipulated medications, and to describe the various definitions and practices of drug manipulation applied in pediatric care.

2. Materials and Methods

The scoping review was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines to ensure a transparent and systematic process [18,19]. However, no formal review protocol was registered.

Eligibility criteria: Inclusion criteria were (1) studies reporting the frequency of drug manipulation in a pediatric population (years of age ≤18) and (2) published between January 2014–July 2024. Exclusion criteria were (1) studies not available in full text, (2) case reports, (3) conference abstracts, (4) a mix of pediatric and adult population (unless specific pediatric results were specifically presented), or (5) were not published in English.

Information sources and search: The search was conducted using PubMed on 18 July 2024, using the string: [(“manipulation” OR “manipulating” OR “manipulated”) AND (“children” OR “pediatric” OR “pediatric”) AND (“drug” OR “medicine”)]. The following filters were used: language: English, population: children from birth—18 years. Manual reference screening followed. Data were extracted independently by two authors and synthesized narratively due to heterogeneity.

Selection of source evidence: One of the authors (S.A.-R.) screened potential studies by reviewing their abstracts, with those meeting the inclusion criteria proceeding to full-text evaluation. To ensure accuracy, the search strategy results were reviewed twice and independently assessed by a second author (L.G.).

Data charting process: Conducted independently by the author (S.A.-R.) and subsequently reviewed in duplicate by a second author (L.G.) to confirm accuracy and consistency. Any discrepancies identified during the data extraction process were resolved through discussion between the authors.

Data items: Information collected included publication year, country, study design, study period, number of participants, number of administrations, age of participants, frequency of manipulation (dividing the number of manipulated administrations by the total number of administrations), number of patients receiving manipulated drugs (the number of patients receiving manipulated drugs divided by the total number of patients), drug formulation, type of manipulation, and definitions of manipulation.

Critical appraisal: No formal critical appraisal was performed, as the review focused on mapping literature rather than evaluating intervention effects.

Synthesis methods: Data extracted from each included study were synthesized narratively due to the considerable heterogeneity in study designs, populations, and reporting methods. The synthesis focused on summarizing key aspects related to drug manipulation in pediatric care, including its reported frequency, the characteristics of manipulated formulations, the types of manipulations performed, and the definitions or descriptions applied across studies. Findings were presented descriptively to provide an overview of current evidence and to identify patterns, gaps, and variations in reporting practices across healthcare settings.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

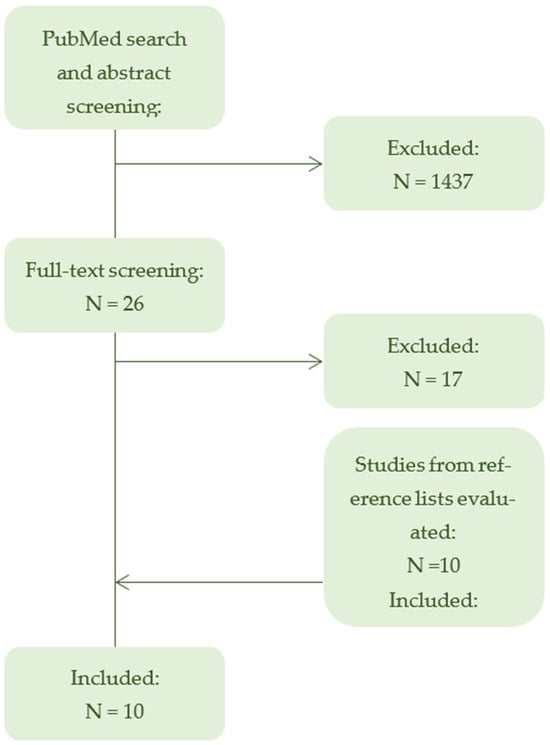

The database search identified 1463 records, of which 1437 were excluded after abstract screening (Figure 1). Twenty-six full texts were assessed for eligibility, resulting in 9 included studies. Screening of reference lists yielded 10 additional records, with one meeting the inclusion criteria, giving a total of 10 studies included in the review (Table 1). All studies explicitly examined pediatric drug manipulation as a primary research focus, reflecting a growing but fragmented body of evidence.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection. PRISMA-ScR flowchart summarizing the selection process of studies included in the scoping review. Of 1463 records identified through database searching, 10 studies met the inclusion criteria. After full-text screening, 17 articles were excluded, primarily due to inclusion of mixed populations comprising both adults and children, as well as articles not published in English. The flowchart illustrates the progressive exclusion of ineligible studies (->) and the identification of additional records (<-) through reference screening.

Table 1.

Study characteristics and results for primary and secondary outcomes.

3.2. Study Characteristics

The included studies were conducted between 2013 and 2021 and published between 2016 and 2023 across nine countries (Norway, Kenya, the Netherlands, Germany, China, the United States, Sweden, Sri Lanka, and Ethiopia). All were observational, with six specifying a cross-sectional design [20,21,22,23,24]. Study durations ranged from 1 month to 2.5 years, and population ages from 0 to 18 years. Sample sizes varied markedly (19–1497 participants), and the number of drug administrations ranged from 115 to 78,366. The diversity in designs, populations, and outcome measures highlights the lack of standardized methods for quantifying and reporting pediatric drug manipulation (Table 1).

3.3. Frequency and Nature of Manipulation

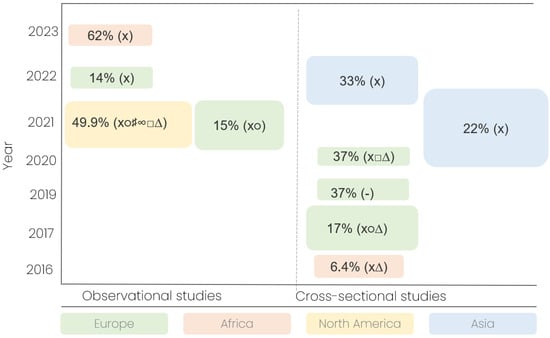

Across the included studies, the frequency of pediatric drug manipulation ranged from 6.4% to 62% of all administrations (Figure 2). Two studies additionally reported patient-level frequencies—57% and 60%—indicating that more than half of the treated children received at least one manipulated medication (Table 1). The wide range of reported manipulation frequencies (6.4–62%) highlights both the lack of standardized definitions for pediatric drug manipulation and the global prevalence of gaps in age-appropriate formulations.

Figure 2.

Overview of manipulation frequencies and drug formulation types in included studies. Bubble plot illustrating the reported frequencies of pediatric drug manipulation across the 10 included studies, stratified by country, study design, and publication year. Each bubble represents a single study. Bubble size is proportional to the total number of drug administrations observed in that study, with larger bubbles indicating studies with more observations. Bubble color corresponds to the continent of origin. Symbols: x, solid oral drugs; ∆, intravenous; ○, sachet; □, liquid; ♯, suppository; ∞, nebulizer; -, not provided.

Manipulated dosage forms included tablets (8 studies), capsules (6), intravenous formulations (4), liquids (2), sachets (3), suppositories (1), and nebulized drugs (1). Most studies involved multiple formulation types, suggesting that manipulation practices span across dosage form categories and reflect a lack of age-appropriate formulations, rather than clinical preference.

3.4. Manipulation Techniques and Definitions

Reported manipulation techniques varied but most frequently included dispersing (8 studies), splitting (7), crushing (5), opening (4), fractionating (3), and mixing (1) (Table 1).

Definitions of “manipulation” differed widely [20,22,23,24,25,26,27]:

- Four studies defined it as a physical alteration of a drug.

- Two as modifications not described in the Summary of Product Characteristics.

- One as alternative administration method;

- One as adjusting a dose to achieve the exact amount prescribed.

This definitional heterogeneity complicates cross-study comparisons and demonstrates the absence of harmonized conceptual and regulatory frameworks for describing and evaluating pediatric drug manipulation.

3.5. Synthesis and Interpretation

Across countries and healthcare settings, the high and variable frequencies of manipulation underscore that the practice is routine yet poorly standardized in pediatric care. The data collectively reveal that manipulation functions as a proxy indicator of systemic inadequacies in pediatric drug formulation, regulation, and access.

Rather than isolated clinical adaptations, these practices reflect a structural dependence on off-label adjustments of adult dosage forms to meet pediatric needs. The inconsistencies in study definitions, outcome measures, and reporting methods further emphasize the urgent need for standardized metrics and evidence-based guidelines to ensure safe, equitable, and age-appropriate pharmacotherapy for children globally.

3.6. Structural Gaps in Pediatric Pharmacotherapy

To further contextualize these findings, five structural gaps are highlighted by the review:

- Limited availability of pediatric-specific formulations;

- Inconsistent regulatory implementation and access;

- Lack of standardized definitions and guidance;

- Insufficient evidence to support safe manipulation practices;

- Inequitable access across regions.

Table 2 summarizes these structural gaps, linking the observed manipulation practices to broader systemic deficiencies.

Table 2.

Structural gaps in pediatric pharmacotherapy identified through the frequency and nature of drug manipulation.

These structural gaps illustrate that pediatric drug manipulation is not merely a clinical workaround but a measurable indicator of systemic deficiencies in formulation science, clinical pharmacotherapy, and regulation. Recognizing manipulation as a structural metric can guide targeted interventions, including the development of age-appropriate formulations, harmonized definitions, evidence-based guidance, and equitable access strategies.

4. Discussion

This scoping review demonstrates that drug manipulation in pediatric care is a widespread and variable practice, occurring in 6.4–62% of drug administrations and affecting up to 60% of children at the patient level (Table 1; Figure 2). Importantly, these practices extend beyond isolated clinical adaptations, reflecting systemic shortcomings in formulation availability, regulatory frameworks, clinical guidance, and healthcare infrastructure. In this context, pediatric drug manipulation can be conceptualized as a measurable indicator of broader deficiencies in pediatric pharmacotherapy (Table 2).

4.1. Age-Appropriateness and Formulation Challenges

Children present unique pharmacological and developmental needs, including swallowing ability, taste preferences, and excipient tolerability [28]. The lack of age-appropriate formulations forces healthcare providers to manipulate adult dosage forms using techniques such as dispersing, splitting, crushing, opening, or fractionating. Manipulations can compromise stability, bioavailability, and pharmacokinetics, particularly for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows or modified-release mechanisms [28,29]. For example, splitting a modified-release tablet may accelerate drug release, increasing the risk of toxicity, while dispersing tablets into liquids may result in variable absorption depending on the vehicle and excipient interactions [3,17]. These clinical risks underscore the need for standardized techniques and comprehensive guidance.

4.2. Global Disparities and Healthcare System Factors

The frequency and nature of drug manipulation vary geographically. European studies generally report lower frequencies (14–37%), likely reflecting the impact of the European Medicines Agency’s Pediatric Regulation, which mandates pediatric trials and encourages age-appropriate formulations [30]. However, even within Europe, manipulation remains common, particularly for rare indications or formulations not commercially available. Studies from low- and middle-income countries, including Kenya, Ethiopia, and Sri Lanka, report the highest and lowest manipulation rates (6.4–62%), reflecting variations in healthcare infrastructure, drug availability, and regulatory oversight (Table 1). These disparities highlight that manipulation is not merely a clinical choice but a reflection of structural inequities and systemic gaps in pediatric drug provision (Table 2).

4.3. Regulatory Initiatives and Limitations

Although regulatory initiatives such as the European Medicines Agency Pediatric Regulation and U.S. Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act and Pediatric Research Equity Act legislation have increased the number of approved pediatric formulations, they do not fully eliminate the need for manipulation [30,31,32,33]. Between 2007 and 2016, 260 new pediatric formulations were approved in Europe [34], yet a substantial proportion were either not marketed or unavailable in practice [35]. Consequently, clinicians continue to rely on manipulation to achieve accurate dosing, particularly for off-patent medications or specific age groups not covered by commercial formulations [36,37].

In parallel, pharmacy compounding serves as an essential mechanism for patients whose needs are not met by commercially available formulations. The 2011 Council of Europe Resolution on quality and safety assurance for pharmacy-prepared medicines seeks to harmonize standards and reduce the quality gap between compounded and industrially manufactured products [38]. In pediatrics, where suitable formulations are often lacking, compounded preparations can provide individualized doses and age-appropriate dosage forms tailored to clinical needs. However, this practice simultaneously mitigates and exposes underlying systemic shortcomings in the availability, quality assurance, and regulation of pediatric-appropriate medicines, reinforcing the broader structural deficiencies identified in this review.

4.4. Manipulation as a Systemic Indicator

Conceptualizing pediatric drug manipulation as a systemic indicator allows for actionable insights. Frequent manipulation signals gaps in formulation availability, inequitable access, inadequate guidance, and potential safety risks (Table 2). It provides a measurable parameter for evaluating healthcare system performance and highlights areas for targeted intervention, including regulation, compounding practices, and formulation development. Variation in techniques and the lack of harmonized definitions complicate cross-study comparisons and indicate the urgent need for standardized metrics and evidence-based guidelines [19,28].

4.5. Clinical Implications and Risks

Different manipulation techniques carry distinct risk profiles. Crushing cytotoxic drugs without appropriate personal protective equipment poses health risks for healthcare providers, while inaccurate splitting or dispersing may result in under- or overdosing in patients [15,20]. Furthermore, the chemical composition of excipients, pH, and the vehicle used can alter drug solubility and bioavailability, potentially compromising therapeutic outcomes [8,28]. These factors emphasize the necessity of formal guidance, training, and standardized procedures to mitigate clinical risks.

5. Future Directions

To address systemic gaps highlighted by manipulation practices, several strategies are recommended:

- Harmonization of definitions and measurement frameworks to allow reliable monitoring and international comparison.

- Standardized reporting of manipulation frequency and techniques, including administration- and patient-level metrics.

- Regulatory incentives and policies to encourage the development and commercialization of pediatric-appropriate formulations, particularly for rare diseases or age-specific populations.

- Evidence-based guidance and training for healthcare providers on safe manipulation practices.

- Innovation in pediatric formulation design, including mini-tablets, orally dispersible films, 3D-printing and taste-masked preparations, ensuring acceptability, swallowability, and stability.

- Expanded research on excipient safety and pharmacokinetic impact of manipulated formulations in pediatric populations.

Limitations

Heterogeneity in definitions, study designs, populations, and reporting limits comparability and generalizability. Most included studies are from Europe, with fewer data from low-resource settings, where systemic gaps may be most pronounced. The review was limited to PubMed because it provides comprehensive coverage of literature most relevant to pediatric pharmacotherapy and drug manipulation. Using PubMed allowed for a focused and efficient search of peer-reviewed, high-quality studies in English capturing the majority of relevant research. While this approach may have excluded some studies indexed in other databases or in the gray literature, it ensured a consistent and reproducible dataset for analysis. In addition, no formal critical appraisal of study quality was conducted, limiting the ability to assess risk of bias across included studies. Observational designs limit insight into underlying reasons for manipulation, and longitudinal outcomes of manipulation remain underexplored. Despite these limitations, the review provides a robust foundation for conceptualizing pediatric drug manipulation as a systemic metric and highlights the practical utility of the identified structural gaps.

6. Conclusions

This study shows that drug manipulation in pediatric medicine is widespread across healthcare systems globally. The types and frequency of drug manipulation, involving different types of patients, medicines and formulations, point to significant gaps in the availability of age-appropriate medicines. Variations in definitions and methods of modifying medicines confirm the lack of harmonization in practice and regulation. Our results suggest systemic deficiencies in formulation development, regulatory frameworks and healthcare infrastructure. Improving these deficiencies requires standardized definitions, validated manipulation methods, changes in legislation and innovation in pediatric medicine development. Acknowledging drug manipulation as a measurable indicator of system shortcoming may in the future inform targeted interventions that make children’s medicines safer, more effective and lead to more balance in pediatric pharmacotherapy globally.

Author Contributions

C.V.: Conceptualized and designed the study including the methodology, participated in the writing of the original manuscript draft, and approved the final manuscript. S.A.-R.: Conceptualized and designed the study including the methodology, designed the data collection instrument, performed data curation, data analyses and validation, participated in the writing of the original manuscript draft, and approved the final manuscript. L.G.: Conceptualized and designed the study including the methodology, designed the data collection instrument, performed data curation, data analyses and validation, participated in the writing of the original manuscript draft, and approved the final manuscript. Y.M.: Conceptualized and designed the study, participated in the writing of the original manuscript draft, and approved the final manuscript. I.M.H.: Conceptualized and designed the study, participated in the writing of the original manuscript draft, and approved the final manuscript. R.M.: Conceptualized and designed the study, participated in the writing of the original manuscript draft, and approved the final manuscript. A.M.: Conceptualized and designed the study, participated in the writing of the original manuscript draft, and approved the final manuscript. S.K.: Conceptualized and designed the study including the methodology, designed the data collection instrument, reviewed and edited the original manuscript draft, and approved the final manuscript. J.T.A.: Conceptualized and designed the study including the methodology, designed the data collection instrument, reviewed, and edited the original manuscript draft, and approved the final manuscript. C.G.: Conceptualized and designed the study methodology, designed the data collection instrument, participated in the writing of the original manuscript draft, and approved the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived, as all data included in this scoping review are available to the public.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Europa Kommissionen. Bedre Medicin Til Børn—Fra Idé Til Virkelighed; Europa Kommissionen: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Paulsson, M.; Svendsen, R.H.; Andersen, J.K.N.; Sporrong, S.K.; Andersson, Y.; Tho, I. Challenges and considerations in manipulating oral dosage forms in Peadiatric Healthcare Settings: A Narrative Review. Acta Paediatr. 2025, 114, 2480–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Vossen, A.C.; Al-Hassany, L.; Buljac, S.; Brugma, J.D.; Vulto, A.G.; Hanff, L.M. Manipulation of oral medication for children by parents and nurses occurs frequently and is often not supported by instructions. Acta Paediatr. 2019, 108, 1475–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, Å.C.; Lindemalm, S.; Onatli, D.; Chowdhury, S.; Eksborg, S.; Förberg, U. ‘Working outside the box’—An interview study regarding manipulation of medicines with registered nurses and pharmacists at a Swedish paediatric hospital. Acta Paediatr. 2023, 112, 2551–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health Research. Manipulation of Drugs Required in Children (MODRIC)—A Guide for Health Professionals; National Institute for Health Research: Southampton, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe, S. Rational Therapeutics for Infants and Children: Workshop Summary; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.Y.; Pettit, R.S. Pharmacokinetic considerations in pediatric pharmacotherapy. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2019, 76, 1472–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadharsini, R.; Surendiran, A.; Adithan, C.; Sreenivasan, S.; Sahoo, F.K. A study of adverse drug reactions in pediatric patients. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2011, 2, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richey, R.H.; Shah, U.U.; Peak, M.; Craig, J.V.; Ford, J.L.; Barker, C.E.; Nunn, A.J.; Turner, M.A. Manipulation of drugs to achieve the required dose is intrinsic to paediatric practice but is not supported by guidelines or evidence. BMC Pediatr. 2013, 13, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, Å.C.; Eksborg, S.; Förberg, U.; Nydert, P.; Lindemalm, S. Manipulated Oral and Rectal Drugs in a Paediatric Swedish University Hospital, a Registry-Based Study Comparing Two Study-Years, Ten Years Apart. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 16, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, A.J. Making Medicines That Children Can Take. 2003. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/479272917/Making-medicines-that-children-can-take-Nunn-2003 (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Verrue, C.; Mehuys, E.; Boussery, K.; Remon, J.P.; Petrovic, M. Tablet-splitting: A common yet not so innocent practice. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011, 67, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skwierczynski, C.; Conroy, S. How long does it take to administer oral medicines to children? Paediatr. Perinat. Drug Ther. 2008, 8, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, B.M.; Capparelli, E.V.; Diep, H.; Rossi, S.S.; Farrell, M.J.; Williams, E.; Lee, G.; van den Anker, J.N.; Rakhmanina, N. Pharmacokinetics of lopinavir/ritonavir crushed versus whole tablets in children. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2011, 58, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richey, R.H.; Hughes, C.; Craig, J.V.; Shah, U.U.; Ford, J.L.; Barker, C.E.; Peak, M.; Nunn, A.J.; Turner, M.A. A systematic review of the use of dosage form manipulation to obtain required doses to inform use of manipulation in paediatric practice. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 518, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kader, R.; Liminga, G.; Ljungman, G.; Paulsson, M. Manipulations of Oral Medications in Paediatric Neurology and Oncology Care at a Swedish University Hospital: Health Professionals’ Attitudes and Sources of Information. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunn, A.; Richey, R.; Shah, U.; Barker, C.; Craig, J.; Peak, M.; Ford, J.; Turner, M. Estimating the requirement for manipulation of medicines to provide accurate doses for children. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2013, 20, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters Micah, D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nderitu, H. Prevalence of Drug Manipulation to Obtain Prescribed Dose in the Paediatric In-Patient Units in Kenyatta National Hospital. Post Graduate Diploma In Biomedical Research Methodology, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bjerknes, K.; Bøyum, S.; Kristensen, S.; Brustugun, J.; Wang, S. Manipulating tablets and capsules given to hospitalised children in Norway is common practice. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 2017, 106, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahn, J.; Hoerning, A.; Trollmann, R.; Rascher, W.; Neubert, A. Manipulation of Medicinal Products for Oral Administration to Paediatric Patients at a German University Hospital: An Observational Study. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hu, Y.; Pan, P.; Hong, C.; Fang, L. Estimated Manipulation of Tablets and Capsules to Meet Dose Requirements for Chinese Children: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 747499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spishock, S.; Meyers, R.; Robinson, C.A.; Shah, P.; Siu, A.; Sturgill, M.; Kimler, K. Observational Study of Drug Formulation Manipulation in Pediatric Versus Adult Inpatients. J. Patient Saf. 2021, 17, e10–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeshkumar, A.; Sathiadas, G.; Sri Ranganathan, S. Administration of oral dosage forms of medicines to children in a resource limited setting. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannesson, J.; Hansson, P.; Bergström, C.A.S.; Paulsson, M. Manipulations and age-appropriateness of oral medications in pediatric oncology patients in Sweden: Need for personalized dosage forms. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 146, 112576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasahun, A.E.; Sendekie, A.K. Are pediatrics taking the prescribed tablet dosage form? Practices of off-label tablet modification in pediatric wards: A prospective observational study. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanovska, V.; Rademaker, C.M.A.; van Dijk, L.; Mantel-Teeuwisse, A.K. Pediatric drug formulations: A review of challenges and progress. Pediatrics 2014, 134, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batchelor, H.K.; Marriott, J.F. Paediatric pharmacokinetics: Key considerations. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 79, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- European Medicines Agency. Formulation of Choice for the Pediatric Population; European Medicines Agency: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act (BPCA); U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Pediatric Research Equity Act (PREA); U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act (FDAMA) of 1997; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Commission to the European Parliament and the Council. 10 Years of the EU Paediatric Regulation; Commission to the European Parliament and the Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tiengkate, P.; Lallemant, M.; Charoenkwan, P.; Angkurawaranon, C.; Kanjanarat, P.; Suwannaprom, P.; Borriharn, P. Gaps in Accessibility of Pediatric Formulations: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study of a Teaching Hospital in Northern Thailand. Children 2022, 9, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, R.B.; Ashworth, L.D.; Zhan, K.; Parrish, R.H., II. How Compounding Pharmacies Fill Critical Gaps in Pediatric Drug Development Processes: Suggested Regulatory Changes to Meet Future Challenges. Children 2022, 9, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Giannuzzi, V. Paediatric formulations—Part of the repurposing concept? Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1456247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Minghetti, P.; Pantano, D.; Gennari, C.G.M.; Casiraghi, A. Regulatory framework of pharmaceutical compounding and actual developments of legislation in Europe. Health Policy 2014, 117, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.