Abstract

The aim of this study is to experimentally capture the semantic, syntactic, and phonological properties of recursive compounds in English. We asked 22 native speakers of English to judge the semantic, syntactic, and phonological properties of 20 recursive compounds that are inherently ambiguous in interpretation (e.g., university entrance exam). We found variations among the participants in each of these three basic aspects. For semantic interpretation, there was a tendency among the participants to prefer left-branching interpretation (‘an exam for university entrance’) over right-branching interpretation (‘an entrance exam in a university’). Using a lexical integrity effect for the syntactic tests, it was found that certain recursive compounds allow for coordination inside. Phonologically, speaker variation was observed in whether and how recursive compounds were pronounced, with 16 participants obeying the Lexical Category Prominence Rule.

1. Introduction

Recursive compounds involve a compound noun that freely becomes the base of another compound noun, and these base compounds are said to be compositional. Recursion has been recognized as a fundamental property of human language that potentially differentiates it from other human cognitive domains and known communication systems in animals (Hauser et al. 2002; Corballis 2011). This study aims to explore recursive compounds in English. If recursion is considered a fundamental property of human language, analysis of recursive compounds will shed light on a significant aspect of human language. A recent debate on universal grammar concerned the existence of recursion in one of the Amazonian languages, Pirahã (Everett 2005).

Our target is recursion in morphology. Expressions (1)–(3) are called recursive compounds.

| (1) | a. | [restaurant [coffee cup]] |

| b. | [student [film committee]] | |

| Mukai (2008, p. 187) | ||

| (2) | a. | [[football] pitch] |

| b. | [[wallpaper] design] | |

| Wang and Holmberg (2021, p. 952) | ||

| (3) | a. | [kitchen [towel rack]] |

| b. | [[kitchen towel] rack] | |

| Kösling et al. (2013, p. 538) | ||

These are all recursive compounds, which involve a compound noun as their base. In three-word components such as (1), (2), and (3), there are two branching patterns: right-branching and left-branching. Right-branching recursive compounds are those with a complex head. For example, coffee cup in (1) is already a compound, acting as the head of the whole compound. The constituent restaurant modifies the complex head. Left-branching recursive compounds are those with a complex modifier. In (2a), wallpaper is a compound, modifying the head, design. The examples in (3) show that recursive compounds can also be ambiguous (Kösling et al. 2013, p. 538), i.e., they make sense for both left-branching and right-branching interpretations. For example, the string kitchen towel rack can be interpreted as either ‘a towel rack in a kitchen’ (3a) or ‘a rack for kitchen towels’ (3b).

As outlined earlier, recursive compounds contain two-member compounds; it is now important to reveal what has been argued in the previous literature about two-member compounds. First, it has been extensively argued that the head in a compound determines the semantic category of the whole compound, and the modifier specifies it (Plag 2003). For example, in a compound like kitchen towel, towel is the head, and kitchen is its modifier since it restricts the meaning of the towel (Bisetto and Scalise 2009). Second, it has been traditionally argued that words are islands for syntactic operations, and word combinations cannot be split. This is called lexical integrity (Lapointe 1980; Selkirk 1982; Di Sciullo and Williams 1987; Bresnan and Mchombo 1995; Bauer 1998; Lieber and Štekauer 2009). In addition, internal inflection is argued to be disallowed inside compounds (Kiparsky 1982; Selkirk 1982; Haskell et al. 2003; Bauer 2009). Furthermore, Liberman and Sproat (1992), Giegerich (2009) and Kösling (2012) suggest that a prominence assignment in compounds is quite variable, not obeying the Compound Stress rule (Chomsky and Halle 1968). Some studies propose a semantic account that distinguishes the stress patterns of two-member compounds in English.

Recursive compounds comprise two-member compounds like those presented in the previous examples (1–3). Thus, we can hypothesize that the semantic, syntactic, and phonological operations of recursive compounds are governed by similar rules that operate in two-member compounds. Although the topic of recursive compounding has been studied extensively (e.g., Mukai 2008; Giegerich 2009; Tokizaki 2010; Kösling 2012; Mukai 2018; Wang and Holmberg 2021; Mukai and Shimada 2021; Yonekura et al. 2023), the experimental approach is still in its infancy. This study’s aim is to present a comprehensive experimental study of all the properties of recursive compounds in English. Through a set of native speaker judgment tests, we consider whether there are any semantic, syntactic, and/or phonological differences between the right-branching (1a, 1b, and 3a) and left-branching (2a, 2b, and 3b) types.

Concretely, our research questions (RQs) to be addressed are as follows:

| (4) | a. | RQ1 on semantic properties: Given that recursive compounds are potentially ambiguous in their semantic structures, is there a preferred interpretation for native speakers? |

| b. | RQ2 on syntactic properties: Do both left-branching and right-branching recursive compounds obey the lexical integrity test, including coordination, internal modification, and internal pluralization? | |

| c. | RQ3 on phonological properties: Do recursive compounds in English obey the Lexical Category Prominence Rule? If so, to what extent? If not, are there similar patterns observed for two-member compounds? |

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, we introduce and review the previous literature on semantic, syntactic, and phonological analyses of compounds. In the following section, we introduce our research methodology and the details of the experimental tests that were carefully designed based on the previous analyses presented in Section 2. In Section 4, based on the results of this study, we answer Research Questions (4a)–(4c). Finally, Section 5 presents the results based on some of the previous theories of compounding. In conclusion, we summarize our answers to Research Questions (4a)–(4c).

2. Properties of Compounds

We first review the semantic, syntactic, and phonological properties of compounds that become prominent in word–phrase opposition.

2.1. Semantic Properties

Generally, the head in a compound determines the semantic category of the whole compound. In recursive compounds, there are two branching patterns: right-branching and left-branching. Haslpelmath (2010, chap. 7) argues that hierarchical structures in compounds exemplify the possible branching patterns for compounds, and he justifies the different branching patterns through the semantic plausibility of the corresponding phrases. Roeper et al. (2002) and Roeper and Snyder (2005), proposing the Root Compounding Parameter, also justify these different branching patterns based on the semantic interpretation of the compounds.

Huber (2023) devotes a whole chapter to discussing how we know which items in recursive compounds are immediate constituents, i.e., how we know whether the products are left-branching or right-branching. She has two criteria based on the previous literature. The first criterion is formal independence (Plag 2003, p. 39), and the second criterion compares the semantic plausibility. Schmid (2016, p. 206) suggests that we must bear in mind which elements can actually stand alone as lexemes. Following Plag (2003) and Schmid (2016), Huber (2023, chap. 5) applies the criterion of formal independence. For example, in football coach and home health care, the criterion of formal independence would suggest that ball coach does not occur independently, whereas football does. Semantically, the description ‘coach who trains football’ is the only acceptable solution, as opposed to ‘ball coach for foot’. Thus, this criterion decides the structure of football coach to be [[foot ball] coach]. In contrast, for the sequence home health care, health care does occur independently, whereas home health is not generally used as a complex lexeme. Semantically, health care has an established interpretation. Thus, this analysis proposes that the structure [home [health care]] is right-branching.

After conducting small experiments on interpretations of some recursive compounds, Huber (2023, pp. 41–43) goes on to discuss whether paraphrasing the whole compound can be a tool for determining the structure and concludes that it should be used with the awareness that, firstly, there are cases where an authentic paraphrase is not necessarily in line with the semantic structure for the compound. Secondly, paraphrasing often reflects what sounds more natural. In Huber (2023, sct. 5.1.3), she also mentions that paraphrasing is both the formal independence and semantic criterion, as it shows which combination of words can be used independently as compounds and allows us to test which alternative solutions are semantically more equivalent to the complex sequence. Independently, Schmid (2016) also argues that native speakers’ paraphrases of the target compound are reflected in the structure; e.g., the paraphrase ‘sale where people sell things from their car boots’ for car boot sale is reflected in its structure [[carboot] sale] (left-branching), and the paraphrase ‘a newspaper which is published on Sundays’ for Sunday newspaper has the structure [Sunday [newspaper]] (right-branching).

2.2. Syntactic Properties

When analyzing compounds syntactically, it is important to observe how they behave in terms of lexical integrity. To answer Research Question (4b), we will consider whether recursive compounds are more like words than phrases, using the lexical integrity test. According to the lexical integrity test, words are islands for syntactic operations, and word combinations cannot be split. Thus, no modifiable elements can be inserted between the two constituents of a compound, and the first element cannot be modified. For example, the following counterpart can be observed if blackbird is a compound, not a phrase:

| (5) | a. | a black bírd vs. a bláckbird |

| b. | an ugly black bírd vs. an ugly bláckbird |

In (5a), the phrase a black bird can be broken up by ugly, whereas such an insertion is not allowed in the compound blackbird. The adjective ugly only modifies the compound as a whole (Lieber and Štekauer 2009).

The following expressions show that no modifiable element can intervene in word combinations of compounds:

| (6) | a. | hotel room: *hotel cheap room |

| b. | shoe shop: *shoe big shop | |

| c. | life insurance: *life expensive insurance | |

| Shimamura (2015, p. 22) |

They are unacceptable because the adjectives break the link between the two nouns. For example, in (6a), hotel room cannot be split by the adjective cheap.

In addition, functional categories such as conjunctions do not undergo morphological derivation (Bresnan and Mchombo 1995). Bauer (1998, p. 74) also argues that the following is not grammatical, because buttercup is a compound. It does not seem possible to coordinate anything with either the first or second element. Example (7a) shows that the first element of the compound buttercup, butter, is not coordinated with the element bread, and Example (7b) shows that the second element, cup, cannot be coordinated with another element like saucer.

| (7) | a. | buttercup: *bread and buttercups |

| b. | buttercup: *buttercup and saucer |

In contrast, however, coordination seems possible in the construction steel bar (iron and steel bars, steel bars and weights) (Bauer 1998, p. 74), since the construction steel bar is considered a phrase.

The test of the inability to replace the second noun of a compound with a pro-form, such as one, is not used. For example, it is possible to replace the head of a noun phrase, such as a red book and a blue one, whereas it is impossible to do so with the head of a compound, such as a watch maker and a clock one. However, what is and what is not possible is not always clear (Bauer 1998, p. 77). In this work, we do not use this test, since it would be complex to construct test sentences by considering the collocations of the words.

In addition, we should not expect elements within compounds to be pluralizable (Bauer 1998, p. 72). In other words, internal inflection is not allowed inside compounds. Some famous examples are as follows:1

| (8) | a. | *rats eater |

| b. | rat eater | |

| Kiparsky (1982) |

Kiparsky (1982) observes that rule-governed plurals are not preferred as modifiers in compounds. Thus, an eater of rats is a rat eater, not a rats eater. Like this, plural inflection seems to be disallowed as a compound modifier, even when the interpretation can be plural. Interestingly, compounds containing irregular plural inflection are judged as more acceptable by linguists or children (Haskell et al. 2003). Thus, mice eater is accepted more than rats eater.

Although the first element of compounds is inflectionless in most cases, there are counterexamples in English compounds. Selkirk (1982, p. 52) suggests that the actual use of the plural marker might have the function (‘pragmatically speaking’) of imposing the plural interpretation of the non-head to avoid ambiguity. She gives the following examples:

| (9) | a. | programs coordinator vs. program coordinator |

| b. | private schools catalog vs. private school catalog |

Of interest in this study is (9b), which is constructed with three nouns, i.e., what we consider to be recursive compounds. According to Selkirk example (9b) is understood as a catalog for several private schools, not one private school. The non-head of the compound, private schools, involves internal inflection and is interpreted as ‘plural’ as opposed to singular.

There is a group of two-member compounds where the non-head is marked with an element that looks like an inflectional plural marker in English. This group could be a non-head member of recursive compounds. Thus, let us look closely at this kind of two-member compound. The following are typical examples discussed in the previous literature:

| (10) | a. | arms race |

| b. | arms cabinet | |

| (11) | a. | arm race |

| b. | arm cabinet | |

| Bauke (2014, p. 34) |

According to Bauke (2014), the forms in (10) contain an inflectional plural marker. The plurals have a lexicalized interpretation; namely, in these examples, arms is interpreted to mean weapons. The word in (10a) has a different dictionary entry from its corresponding word arm. Hence, an arms race is ‘a competition between two nations in producing and displaying all sorts of weapons.‘ In contrast, however, the novel examples in (11) cannot be interpreted as ‘having to do with weapons.’ They can only have the ‘arm as a limb’ interpretation.

Other examples that are similar to the word arms include sports, resources, and crimes. According to Haskell et al. (2003, p. 123), the compound sports announcer is possible and attested. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the meaning of ‘an occasion on which people compete in various athletic or other sporting activities’ is sports in a plural form. In addition, the word sports is used as a non-head of a two-member compound, such as in the following examples:

| (12) | a. | sports car |

| b. | sports event |

The word resources is used in its plural form with the meaning of ‘a country’s collective means of supporting itself or becoming wealthier, as represented by its reserves of minerals, land, and other natural assets.’ In addition, this word is usually used with this form, not its singular form. Thus, compounds like (13) are allowed:

| (13) | a. | resources policy |

| b. | resources development |

Another similar example is the word crimes. According to the Genius English-Japanese Dictionary, this word is usually used in its plural form:

| (14) | a. | crimes tribunals |

| b. | crimes trial |

In addition to the words above, another group of words appears in the plural form when used as the non-head of a compound word. Examples include systems, gains, emissions, and sales. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, they all appear in the plural, not singular, form as the non-head of a compound. Thus, examples like the following can be seen as compounds:

| (15) | a. | systems analysis |

| b. | sales representative | |

| c. | gains tax | |

| d. | emissions standard |

Since the plural markers in the data from (10) to (15) are not necessarily phonological representations of the plural feature, they do not disobey the rule of plural inflection being disallowed inside compounds. Bauer (2009) also says that a so-called ‘plural’ attributive may not be a genuine breach of the lexicalist hypothesis. In a later section, we will discuss this kind of group of compounds as non-heads in recursive compounds.

Finally, Bauer (2009) argues that in longer compounds, <s> is sometimes used to show the immediate constituent structure in the compound. For example, contrast the attested distinction between [[[British Council] jobs]] file] and [British Council] [jobs file] (Bauer 1978, p. 40). He goes on to argue that if the <s> is used in this way, it suggests that plurality is not all that is at stake here. If we see this kind of example in our data, we can consider it a recursive compound; then, <s> is used to link an element, as in Swedish (Holmberg 1992; Roeper et al. 2002).2

2.3. Phonological Properties

It has been traditionally argued that compounds in English are generally left-prominent (Chomsky and Halle 1968), e.g., bláckbird vs. black bírd. However, Compound Stress patterns are not monolithic. Giegerich (2004) argues that complement–head NNs are fore-stressed, whereas attribute–head constructions are end-stressed.

For recursive compounds, the most well-known phonological property of compounds is captured in the Compound Stress Rule (CSR) (Liberman and Prince 1977). Liberman and Prince adapted Chomsky and Halle’s (1968) Compound Stress Rule into their stress theory and proposed the ‘Lexical Category Prominence Rule’, which is given in (16):

| (16) | In a configuration [CABC]: | |

| a. | Nuclear Stress Rule (NSR): If C is a phrasal category, B is strong. | |

| b. | Compound Stress Rule (CSR): If C is a lexical category, B is strong if it branches. |

According to (16), one constituent is always strong, i.e., more prominent, with respect to its immediate sister constituent. The sister constituent is automatically assigned a weak status. In addition, the LCPR is thought to apply simultaneously at every level of the syntactic tree. Thus, at the level of complex word formation, such as recursive compounds, B, the second element, will receive the strongest stress if it is a compound itself. This is in the case of right-branching recursive compounds. In contrast, in the case of left-branching compounds, the second element, B, is not branching, meaning the first element, A, will receive prominence. For example, in left-branching compounds like [[seat belt] law], the leftmost noun, seat, receives the main stress. Hence, the left-branching seat belt law would be predicted to have seat as the most prominent constituent. In contrast, in right-branching compounds such as [team [locker room]], the second noun is most prominent, which is locker. Giegerich (2015) argues that there are eight possibilities for stress patterns of NNNs, each of which exists. In addition, he argues that all left-stressed NNs are compounds, whereas end-stressed NNs are not always phrases on syntactic and semantic grounds. Kösling (2012) shows that about a third of both left- and right-branching compounds do not behave according to the LCPR and explored some reasons for this violation, following the previous literature.

3. Methodology

As discussed in Section 1, the main aim of this work is to capture recursive compounds in English. To reveal the semantic, syntactic, and phonological properties of recursive compounds, we conducted experimental tests with native English speakers as participants. We collected nominal recursive compounds from the previous literature on recursive compounds, such as Bauer (1998), Kubozono (1999), Kösling (2012), Plag (2018), Huber (2023), and the Oxford Dictionary of English. However, this resulted in over 200 words. Even after trying to obtain the highest-frequency compounds from each alphabetic letter, we still had 60 words. Too many questions would make participants unwilling to participate, so we decided to test data that were unclear regarding their branching pattern, according to Huber (2023). In this subsection, we explain how we conducted these tests.

3.1. Data

More specifically, we rely on Huber’s method, determining branching directions in recursive compounds, and lexical integrity tests for a syntactic consideration. As a phonological matter, we are concerned with whether and how branching directions and prominence are related to each other.

Huber (2023) gives an in-depth analysis of compounds consisting of more than two lexemes. As far as we are aware, there is no study of complex compounds with a fundamental amount of data other than Huber’s. She collects data from the Corpus of Contemporary American English (Davies 2008). Huber cites some examples that are not clear concerning their branching pattern. They are listed in (17):

| (17) | aggression prevention program, cancer research center, currency exchange rate, data management system, infant mortality rate, missile defense system, office lunch bill, party membership card, program planning process, project evaluation process, prosecution team member, safety monitoring board, soil conservation program, transportation safety board, system development process, teacher education program, behavior assessment system, college entrance exams, drug rehabilitation program, highway traffic safety, sea surface temperature, vehicle registration number, violence prevention program, voter registration number, water filtration system |

These examples show no tangible difference between the two competing interpretations (Huber 2023, p. 47). As shown in Section 2.1, Huber (2023) suggests two ways to determine the branching patterns: formal independence and the plausibility of the meanings of the potential bases. She argues that the branching patterns of the examples in (17) cannot be determined using either formal independence or plausibility of the potential bases. For example, does the compound cancer research center denote ‘center for cancer research’ or ‘research center for cancer’? She argues that the two competing interpretations (branching) seem identical in meaning. We chose the following 13 compounds from (17) for our experimental study, which are common to both American and British native speakers of English:

| (18) | a. | cancer research center |

| b. | currency exchange rate | |

| c. | data management system | |

| d. | infant mortality rate | |

| e. | office lunch bill | |

| f. | party membership card | |

| g. | soil conservation program | |

| h. | system development process | |

| i. | English language teaching | |

| j. | university entrance exam | |

| k. | drug rehabilitation program | |

| l. | sea surface temperature | |

| m. | vehicle registration number |

These phrases were tested among our informants for each criterion, covering semantic, syntactic, and phonological criteria.

We also added the following compounds as experimental data:

| (19) | a. | carbon footprint |

| b. | strawberry and rhubarb pie | |

| c. | hot cross bun | |

| d. | hot water bottle | |

| e. | Christmas party hat | |

| f. | air traffic control system | |

| g. | elephant danger zone |

Let us explain why the above seven compounds were added to the test material. Compound (19a) was added to test whether an irregular plural is preferred to a regular plural inside compounds and whether the spelling as one word, like footprint in (19a), influences native speakers’ semantic interpretation of the whole word. Compound (19b) is a recursive compound that looks as if it contains a coordinate expression, strawberry and rhubarb, which seems to be an important example in terms of lexical integrity. Both (19c) and (19d) involve the adjective hot. According to the lexical integrity, internal modification is impossible, and the word hot cannot be modified by an adverb if the whole string of words is a compound and not a phrase. Regarding (19e), it is ambiguous between the two interpretations, that is, ‘a fun hat worn at a Christmas party’ and ‘a party hat worn at Christmas time’ (not necessarily at a party). Compound (19f) was included since Huber (2023, p. 47) observes that the compound traffic control system is ambiguous. Finally, the term (19g) was added instead of the term depression danger zone, which is cited in Huber’s ambiguous data. According to the control participant in our experiment, the word ‘depression’ could be a source of some awkwardness. We would like to see whether (19g) can be ambiguous in interpretation.

3.2. Study Procedure

Our experimental study consisted of three parts. Part 1 contains Interpretation Test 1, which concerns semantic interpretations. The participants were asked to explain each word to reveal the semantic characteristics ), i.e., to see whether the target recursive compound was left-branching or right-branching. The recursive compounds were presented to them one by one with the question, ‘What is the meaning of the expression above? Please write what you think intuitively and do not take too much time’ (see Appendix A, Test b for more details).

Part 2 contains Interpretation Test 2, which examines syntactic properties. To reveal whether the target compounds were closer to words than phrases based on lexical integrity (Lapointe 1980; Selkirk 1982; Di Sciullo and Williams 1987; Bresnan and Mchombo 1995; Bauer 1998; Lieber and Štekauer 2009). (see below for more details on lexical integrity), the participants were presented with a longer phrase including the word and asked this question: ‘How natural do you find the expression within a longer phrase (please judge on a scale of 1–7, where 1 means ‘totally unnatural’ and 7 means ‘perfectly natural)’? For example, another element can be inserted for English language teaching, so the participants were presented with ‘English language and French language teaching.’ The participants were asked to explain their answers so that the experimenter could understand what the participants were thinking when they scored the phrases. When the same study was conducted with the control participant, the reasons for their choices were not clear to the experimenter, because they were not asked to explain their reasons. When we know the participants’ reason(s) for their choice, it is easier to analyze the syntactic properties of the words (see Appendix A, Test c for more details).

In Part 3, we include a recording task as a phonological experiment. To see whether recursive compounds follow the LCPR in (16), we asked each participant to record their voice, reading a simple sentence involving the expression. They were asked to say the target sentence three times to ensure we obtained data for each target word.

The sentences were invented by the researcher. The LCPR in (16) says that if the target compound in the sentence is a left-branching recursive compound, the prominence stress is placed on the first element, whereas a right-branching recursive compound has the second element carrying the strongest prominence, and the first element has the second-strongest prominence (Section 2.3).

For example, to elicit ‘English language teaching’, the sentence was ‘This course offers English language teaching’ (see Appendix A, Test a, for more details).

3.2.1. How Did We Proceed with the Study?

To obtain as many participants as possible, we used the Internet application Gorilla Experiment Builder, which helps build psychological experiments (http://app.gorilla.sc, accessed on 22 August 2023). We sent a request letter with the experiment URL written so the participants could log in to the study automatically. For the URL, as long as they had a microphone installed on their computer/laptop or smartphone, the participants were able to record their voice for test Part 3. With the request letter and the URL, there was an explanation about the study to the participants, and the participants were given the choice to withdraw from the study (or, of course, not to participate in the study even after they had been asked), even during participation. They simply had to close the URL to withdraw from the study. This study is in compliance with the experimenter’s university’s ethical committee (Ethics Committee), and the participants’ rights were respected. They were able to ask the experimenter any questions by email. However, no questions were asked.

After all the participants told the experimenter they had finished the test by email, the experimenter downloaded the data from the URL and analyzed them.

3.2.2. Participants

The present study recruited 1 native speaker of British English as a control and 22 native speakers of English, of which 4 were American, and the rest were British. The control participant checked the content of the study, and according to his corrections, the content was then put together as described above.

The other participants were asked about their language environment to make sure they were all native speakers of English. In addition, to ensure they could conduct the tests without too much trouble, the experimenter asked her friends who had completed a minimum of a higher education qualification. She also asked her friends to pass information around to obtain more participants. One participant advertised recruitment on her postgraduate students’ website, and another asked friends she knew who had higher education qualifications. Finally, one participant also asked another group with a higher education qualification if they were interested in participating in such an experiment.

3.2.3. Equipment for Analyzing Speech for Part 3 (Stress Accent)

According to Kösling (2012), the stress assignment of compounds should not rely on the researcher’s intuition, and to ensure that data are as objective as possible, utterances should be measured acoustically. In Kösling’s experiment, he manually extracted the data from the Boston University Corpus. However, our experiment aimed to understand native speakers’ stress placement on recursive compounds, so we decided to record the participants’ voices. Kösling argues that pitch seems to be the strongest predictor of the stress of compounds (Kösling 2012, p. 25). For this study, after collecting all the participants’ recordings, their data were transcribed by the software Praat, created by Paul Boersma and David Weenink from the University of Amsterdam (Boersma and Weenink 2020) (http://www.praat.org/) (accessed on 10 September 2023).

Following the method used by Kösling (2012), we first manually segmented the target compound words from the three recorded sentences. We chose the sentence that was the clearest of the three. Then, we manually segmented the recorded sentence from which the target recursive compound was extracted. All the sentences had the target item in the same syntactic position, namely, at the end, except for We have the highest infant mortality rate in Africa for item (18d). For example, for item (18k), English language teaching, we asked the participants to say, ‘this course offers English language teaching’, from which (18k) English language teaching was extracted in Praat. Then, the mean pitch value of the vowel for each constituent was automatically measured by the Praat script. A total of 13 women and 9 men participated in this experiment. Gender-specific pitch ranges were considered by choosing pitch boundary settings of 75–250 Hz for male speakers and 100–300 Hz for female speakers (cf. Kösling 2012).

There were no cases of creaky voice or octave jumps on the recordings, so no adjustments were made. However, one of the participant’s pronunciations of (18m) and another’s pronunciation of (18k) were not on the recordings, so they were excluded from the data. We erroneously did not make a sentence for (19g); thus, we do not have any data for this compound (19g).

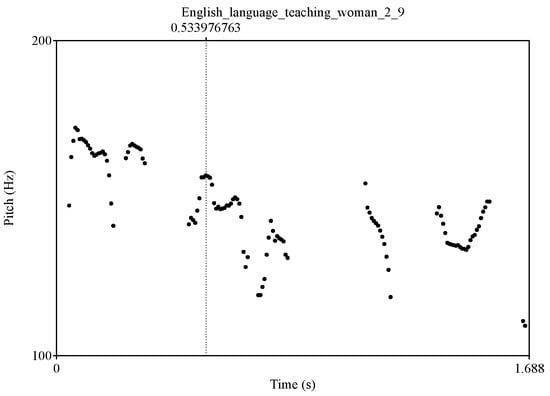

One participant’s pitch track, for example, of (18k), is as follows in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Pitch track of English language teaching (a female).

In this case, the speaker assigns the highest pitch to the first noun, English, as the dots show. In agreement with the LCPR (see (16)), the left-branching compound’s pitch track shows the highest pitch assigned to the first noun.

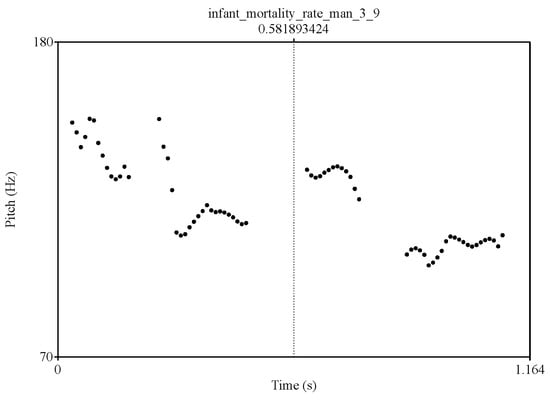

In contrast, Figure 2 suggests a relatively high pitch on both constituents N1 and N2, infant and mortality. Concretely, the word infant measured 116 Hz, whereas mortality measured 116.4. Thus, there is no significant difference between them. This is a typical pronunciation pattern of right-branching recursive compounds according to the LCPR.

Figure 2.

Pitch track of infant mortality rate (a male).

4. Results

4.1. Part 1: Semantic Interpretations

In Part 1, we asked the participants to write what the expression meant to them to know whether datasets (17) and (18) have left- or right-branching interpretations. The following points are what they wrote in their answers. We summarized their answers in our own words. When two interpretations are written, it means that some of the participants interpreted the item as both left- and right-branching. To determine the immediate constituents of the target compounds, we used the participants’ paraphrases (Section 2.1), since paraphrases can both be formally independent and have semantic plausibility. When the words in the participants’ speech were not the exact members of the target compounds, we analyzed them as those words, since the participants rephrased them in their own words. Based on Schmid’s (2016) and Huber’s (2023) analyses from paraphrasing, we determined the branching. For example, (18b) was interpreted by the participants as ‘the rate at which currency is exchanged.’ From this paraphrase, currency exchange is one word, resulting in a left-branching interpretation. Another interpretation was, ‘how much money you obtain when buying foreign currency?’ Buying foreign currency is explained as an exchange of currency, and how much money you obtain is the rate. Thus, the compound is left-branching.

| (20) | cancer research center Interpretation ‘a center where research into cancer is carried out’ | |

| (21) | a | currency exchange rate Interpretation 1 ‘the amount for exchanging one country’s currency into the currency of another country’ |

| b | Interpretation 2 ‘conversion rate between currencies’ (two people) | |

| (22) | data management system Interpretation ‘a computer-based or manual set of procedures designed to gather, organize, and distribute data in a meaningful way’ | |

| (23) | a | infant mortality rate Interpretation 1 ‘the percentage at which infants die’ |

| b | Interpretation 2 ‘the death rate of infants’ (two people) | |

| (24) | a | office lunch bill Interpretation 1 ‘total bill for everyone working in the office who have purchased lunch from a catering supplier’ |

| b | Interpretation 2 ‘lunch bill for all those in the office’ (two people) | |

| (25) | a | party membership card Interpretation 1 ‘card to identify specific membership in a political party’ |

| b | Interpretation 2 ’membership card you get sent when you join a political party’ (four people) | |

| (26) | soil conservation program Interpretation ‘a program to ensure that the soil remains fertile’ | |

| (27) | system development process Interpretation ’the process that one can use to create a set of procedures and/or structures for a given system’ | |

| (28) | English language teaching Interpretation ‘teaching of the English language to non-English speakers’ | |

| (29) | a | university entrance exam Interpretation 1 ‘an exam given by the university to score and order applicants to be admitted to the university’ |

| b | Interpretation 2 ‘an entrance exam to determine who should go to university’ (one person) | |

| (30) | drug rehabilitation program We made a mistake on this term; we wrote the term as ‘drug rehabilitation programmer’, so the participants’ interpretations are excluded from this work | |

| (31) | sea surface temperature Interpretation ‘the temperature of the surface of the sea’ | |

| (32) | a | vehicle registration number Interpretation 1 ‘the number that shows when a car is registered’ |

| b | Interpretation 2 ‘the registration number of the car, the way in which you can tell which car is yours’ (two people) | |

| (33) | carbon footprint Interpretation ‘the amount of carbon added to the atmosphere’ (right-branching) | |

| (34) | strawberry and rhubarb pie Interpretation ‘pie with a mix of strawberries and rhubarb’ | |

| (35) | hot cross bun Interpretation ‘a type of pastry with a cross-shaped pattern on top, served hot’ (right-branching) | |

| (36) | hot water bottle Interpretation ‘a rubber flask that you put hot water inside to keep you warm’ | |

| (37) | a | Christmas party hat Interpretation 1 ‘a hat worn at a Christmas party or Christmas time’ (four people) |

| b | Interpretation 2 ‘party hat worn at Christmas time’ (18 people) | |

| (38) | airport traffic control system Interpretation ‘a computer-based program that organizes and controls flight paths and airplane arrivals/departures’ | |

| (39) | elephant danger zone Interpretation ‘a zone where there might be a lot of elephants, so it is a danger to elephants or dangerous because of elephants’ |

4.2. Part 2: (Syntactic Properties)

In Part 2, we tested how natural the participants think a longer phrase is and asked them to score it from 1 to 7. The results of the test are summarized below at the end of this section. In this sub-section, we show the results of the tests. Unfortunately, we did not perform a test on the word currency exchange rate. To show the results of the test, we marked the target expressions with *, *?, and ?. * shows that the result of the average score among the participants is between 1 and 3, *? 3 and 5, and ? 5 and 6, and nothing for between 6 and 7. We discuss the results later in Section 5.

First, we show the results of the examples from the coordination test. The compounds that were tested using this method were as follows: data management system, infant mortality rate, soil conservation program, English language teaching, drug rehabilitation program, Christmas party hat, and elephant danger zone.

| (40) | ? data and finance management systems |

| (41) | *? infant and elderly mortality rate |

| (42) | ? soil and air conservation programmes |

| (43) | ? English language and French language teaching |

| (44) | drug and alcohol rehabilitation programs |

| (45) | ? Christmas party and sun hat |

| (46) | *depression and elephant danger zone |

Second, the result from the internal modification test is below. The compounds with this test are cancer research center, party membership card, hot cross bun, hot water bottle, air traffic control system, and sea surface temperature.

| (47) | *? the latest cancer research center |

| (48) | Labor party membership card |

| (49) | * very hot cross bun |

| (50) | *? very hot water bottle |

| (51) | *air traffic in control system |

| (52) | *? smooth sea surface temperature |

Third, we show the result from the test of plurals. The compounds in this test are office lunch bill, university entrance exam, vehicle registration number, system development process, carbon footprint, and strawberry and rhubarb pie.

| (53) | *? office lunches bill |

| (54) | *? universities entrance exam |

| (55) | *vehicles registrations number |

| (56) | ? systems development process |

| (57) | *carbon feet print |

| (58) | *strawberries and rhubarbs pie |

Is regular plural inflection really allowed inside recursive compounds? As discussed in Section 2.2, few two-member compounds allow for plural inflection, and words like sports, resources, crimes gains, emissions, and sales can be used in recursive compounds as the modifier element. We found the following cases. Before discussing the results of our study, below, we show examples from Kösling (2012) and Huber (2023). Other previous studies featured no recursive compounds with a plural inflection inside.

| (59) | a. | capital gains tax | (Kösling 2012, p. 62) |

| b. | auto emissions standard | (Kösling 2012, p. 155) | |

| c. | retails sales transaction | (Kösling 2012, p. 158) | |

| d. | water resources authority | (Kösling 2012, p. 158) | |

| (60) | a. | war crimes tribunal | (Huber 2023, p. 81) |

| b. | war crimes trial | (Huber 2023, p. 112) | |

| (61) | a. | boys basketball | (Huber 2023, p. 107) |

| b. | girls basketball | (Huber 2023, p. 107) |

Via a quick browse through Google, we find that (61a) and (61b) are written both with and without the apostrophe. The meaning of these words is sport for girls or boys. The apostrophe can sometimes be omitted. They are not semantically ‘plural’. We asked a native speaker if we were right in our analysis, and they said yes.

So far, we have found that an element that looks like a plural inflection marker inside recursive compounds is not semantically plural.

| (62) | a. | street lawyers studies | (Kösling 2012, p. 158) |

| b. | street lawyers program | (Kösling 2012, p. 158) | |

| c. | summer jobs programs | (Kösling 2012, p. 158) | |

| d. | tax payers foundation | (Kösling 2012, p. 158) |

By looking at examples cited in the prior literature, we found only the four above that are semantically plural, and the rest are either examples of compounds where the plural form has an attributive use or the meaning is specifically different from its singular counterpart. In addition, when we asked a native speaker for their intuitive judgment on the above compounds, they were not aware of (62a,b), and for (62c), the word means ‘programs for various jobs’, and (62d) is interpreted as ‘an organization supporting more than one taxpayer.’ As a result, these words are all treated as plural semantically, unlike their singular counterparts.

4.3. Part 3: Phonological Properties

To determine whether recursive compounds follow the LCPR (Liberman and Prince 1977), we asked each participant to record their voice, reading a simple sentence provided involving the expression.

After measuring the acoustic pitch of the vowel on each constituent of the whole compound, we counted the number of participants whose acoustic pitch was measured the highest and calculated the average of the pitch measurements. Detailed results are presented in Appendix B.

To condense the results into one simple sentence, we determined that there was no consistent pattern for acoustic pitch on these compounds. We observed different patterns between the male and female participants. Infant mortality rate, hot water bottle, and air traffic control system for the male participants and currency exchange rate, vehicle registration number, and system development process for the female participants had their N1 constituent with the highest prominence. In other words, there were variations between either the N1 and N2 words or between genders. We discuss the results in the following section in more detail.

4.4. Summary of the Results

Summarizing the results of the three tests, we present the following in Table 1. For the semantic interpretation, we decided whether the compound was left- or right-branching based on our participants’ judgments. We present the average score for the syntactic test, and for the phonological test, we show which word, N1, N2, or N3, was the most prominent. When the results were variable, we provided the results according to the different sexes. More detailed results for each test can be found in Appendix B.

Table 1.

Results of the three tests.

5. Discussion

5.1. Semantic Properties

- (4a) Research Question 1

Given that recursive compounds are potentially ambiguous in their semantic structures, is there a preferred interpretation given by native speakers of English?

In Section 2.1, we looked at Huber’s (2023) discussion on how to determine the branching directions of recursive compounds. Her methods examine the formal independence and plausibility of the meanings of the potential bases. We can also paraphrase the whole compound as long as we know the discrepancy between the semantic and syntactic structures. If, however, we go for what sounds natural, then we can use paraphrasing. To simply answer Research Question 1, based on our native speakers’ interpretations, there seems to be a tendency to have more left-branching interpretations than right-branching for all of the target recursive compounds. We also found that even when the participants interpreted the compounds differently, no compounds were ambiguous in terms of branching, as Huber argued. Thus, all the compounds were either left- or right-branching according to the participants’ interpretations.

Let us explain each compound in more detail. We first discuss the compounds with only left-branching interpretations, then those that were interpreted as more left-branching than right-branching. Thirdly, those with more right-branching than left-branching compounds are discussed. Finally, we discuss those with only right-branching interpretations.

Cancer research center, data management system, soil conservation system, English language teaching, sea surface temperature, hot water bottle, air traffic control system, and elephant danger zone are all interpreted as left-branching recursive compounds. For example, hot water bottle is interpreted as a ‘bottle with hot water for warming the body.’ ‘A water bottle that is hot’ is also a possible interpretation, but no participants interpreted it this way. Although all these compounds possibly have both combinations of the constituents, e.g., hot water or water bottle is possible, for system development or development process, the first two words are more likely to be in compounds than the second and third words. English language teaching is also a left-branching compound, since all the participants interpreted it as ‘teaching of the English language to non-English speakers.’ Thus, here, what is more natural is that English language is the base, which means ‘the language of English’, and the whole compound English language teaching is simply ‘teaching of the English language.’ In addition, some of the participants interpreted English language teaching as ‘teaching of non-English subjects in the English language.’

Strawberry and rhubarb pie contains a phrase and a so-called co-compound, forming a conceptual unit (e.g., father–mother denoting parents, cf. Wälchli 2005). Even though it does not contain an overt conjunction, co-compounds are compounds whose meanings are the result of coordinating the meaning of their components. Therefore, father–mother, for example, denotes ‘parents’, having the two constituents as semantic heads. Similarly, the participants in our experiment interpreted the word as ‘a pie with strawberries and rhubarb, a baked pie, brown crust, two different kinds of fruits or mixed fruits, pastry, etc.’ Both strawberry and rhubarb are then semantically heads.

In contrast, as Huber argues, some of the participants interpreted compounds as right-branching and the rest as left-branching for currency exchange rate, infant mortality rate, office lunch bill, party membership card, university entrance exam, and vehicle registration number. Huber argues that both left-branching and right-branching interpretations have the same meanings, which is why the branching direction is ambiguous (Section 3.1). However, the left-branching interpretations and right-branching interpretations, according to the participants’ intuition, are different. For example, party membership card with its left-branching interpretation is ‘a card to identify specific membership in a political party’, whereas its right-branching version is ‘a membership card for a political membership.’ The right-branching interpretation for all these words uses the second word twice. In addition, the participants tend to interpret these compounds with the left-branching interpretation rather than the right-branching one. For example, the number of participants who interpreted party membership card as left-branching was 18, and only 4 interpreted it as right-branching. Thus, we can safely argue that this word has a left-branching interpretation. For university entrance exam, only two participants interpreted it as right-branching. Moreover, for cancer research center, only three participants interpreted it as right-branching. Also, vehicle registration number had only two participants interpreting it as right-branching. Thus, these compounds had more participants interpreting left-branching.

Next, Christmas party hat had a higher number of participants interpreting it as right-branching than left-branching. Only four people interpreted it as a left-branching interpretation. Although the wording was different, they all interpreted it as ‘a hat worn at a Christmas party or Christmas time’, whereas 18 participants interpreted it as right-branching, e.g., ‘a party hat with a Christmas theme, silly party hat at Christmas.’ Interestingly, two of the participants interpreted it as both interpretations.

Finally, hot cross bun and carbon footprint were interpreted as right-branching by all participants. Hot cross bun was interpreted as ‘a type of pastry’ (which is a paraphrase for the word bun), with a ‘cross-shaped pattern on top, served hot’. Thus, the structure would be [hot [cross bun]]. Similarly, as for the compound carbon footprint, all the participants interpreted it as ‘the amount of carbon added to the atmosphere’, resulting in a right-branching structure, i.e., footprint is its head modified by carbon.

5.2. Syntactic Properties

- (4b) Research Question 2

Do both left-branching and right-branching recursive compounds obey the lexical integrity test, including coordination, internal modification, and internal pluralization?

As shown in the previous section, we tested whether the recursive compounds in question allow for coordination and internal modification. First, we report the results of the coordination test.

| (63) | a. | ?*English language and French language teaching |

| b. | *?infant and elderly mortality rate | |

| c. | ?data and finance management system | |

| d. | ?Christmas party and sun hat | |

| e. | ?drug and alcohol rehabilitation programs | |

| f. | ?soil and air conservation programs | |

| g. | * depression and rhinoceros danger zone |

As discussed in Section 2.2, Bauer (1998) argues that two-member compounds should not include any element separating their constituents. As he argues about two-member compounds, the target recursive compounds should not be separated by and, as the unnaturalness of some of the above phrases shows. Some of the participants even commented that the target compounds should be a unit, not separated by another element. This is in agreement with what Dahl (2004, p. 180) expresses. Those that did not sound too unnatural, such as (63b), (63c), (63d), (63e), (63f), and (63g), involve phrases inside them (see Nishiyama 2015 for Japanese compounds). It is necessary to check whether these have a phrasal accent rather than a compound accent, but we did not follow up on the participants’ phrasal accents in these examples. Christmas party hat has a right-branching interpretation as well as a left-branching interpretation, which may be the reason for allowing the coordination.

We show the results of the modification test below.

| (64) | a. | ? *very hot cross bun |

| b. | *very hot water bottle | |

| c. | *? the latest cancer research center | |

| d. | ? *air traffic in control system | |

| e. | Labor party membership card | |

| f. | *smooth sea surface temperature |

As the lexical integrity principle predicts, according to native speakers’ judgments, modification of the word hot in both hot water bottle and hot cross bun is not allowed. Some participants also commented that the word hot is a unit with the other two elements, so it cannot be modified by another word. This comment given by the participants agrees with what Shimamura (2015) argues about qualifying adjectives that appear as the non-head of two-member compounds, such as freshwater and small town. Shimamura argues that some qualifying adjectives serve to classify types when appearing as the non-head of compounds, losing their real function as adjectives. In addition, along with what Dahl (2004, p. 180) expresses, Shimamura argues that this type of compound with a qualifying adjective expresses a ‘unitary’ concept. We propose that expressions such as hot cross bun or hot water bottle also express a ‘unitary’ concept, and the adjective hot, which is a qualifying adjective, loses its real function and serves to classify types in the non-head of the compound. In other words, hot water bottle is not a bottle that is hot; it is a type of bottle. Similarly, hot cross bun is not a cross bun that is hot; it is a type of bun. The adjective hot has lost its ability to qualify the head noun(s). However, the average rate for very hot water bottle was 4.18, so it was not completely unnatural for some of the speakers. Therefore, for these speakers who say it is possible to say very hot water bottle, the whole expression is not considered as a ‘unitary’ concept. The same argument can be made for the expressions the latest cancer research center and smooth sea surface temperature. The combinations of the words latest and center and smooth and temperature, according to some of the participants, were not semantically natural. In addition, the phrase air traffic in control program is unnatural due to the insertion of the preposition in. The most interesting expression was Labor party membership card. Party membership card was interpreted as both right- and left-branching by the participants. Almost all participants judged it as natural, which may be due to the combination of the two words Labor and party. We can conclude that internal modification is sometimes allowed for these expressions, perhaps because these recursive compounds are ambiguous in their branching direction.

The results of our study suggest that it is not possible to have a regular plural inflection inside recursive compounds, even though the non-head constituent of the recursive compounds can be counted as semantically plural.

| (65) | a. | *strawberries and rhubarbs pie |

| b. | *?office lunches bill | |

| c. | *?universities entrance exam | |

| d. | *vehicles registrations number | |

| e. | ?systems development process | |

| f. | *carbon feetprint |

Even when, for example, there is more than one strawberry, lunch, university, or vehicle/registration concerned, some participants even commented that modifiers of a compound should not be in the plural form, only in the singular form. According to some of the participants’ comments, modifiers of compounds are considered adjectives in spite of their nominal appearances (e.g., strawberry or rhubarb is an adjective, which is why it cannot be pluralized (see more in Appendix B)). This is connected with the issues of relational adjectives, which do not express property but rather a relation to a concept designated by a noun (Ten Hacken 2019) and classify a specific type of noun (Shimamura 2015). Typical examples of relational adjectives that appear as non-heads of compounds are musical, solar, historical, architectural, commercial, and many others. Strawberry and rhubarb in the recursive compound (65a), although they appear in the nominal form, act semantically as relational adjectives, i.e., a relation to the concept of pie, and the whole compound semantically classifies a specific type of pie. The same argument can be made for the other examples, except for (e).

In addition, disallowing plural inflection inside compounds reminds us of what Baker (2003, pp. 210–11 and fn. 15) suggests about attributive adjectives, which are not used predicatively in English. He suggests that in languages that inflect for number, gender, and case, there is always agreement between the attributive adjectives and the nouns that they modify. This agreement is necessary, even in languages that do not have an overt agreement between these elements. He says, ‘if adjectives could not bear agreement (not even covert agreement) in a particular language, they would be barred from attributive constructions in that language’. Thus, an agreement between the attributive modifier (adjective) and the head of a compound, which is a noun, needs to take place. This might be the reason why the non-head of a compound is always singular, i.e., there is agreement with the head noun as a singular. In fact, Nagano (2015, p. 11) argues that such agreement needs to be there between direct modification and the noun in the constructions, such as a ten-year-old boy vs. a boy who is ten years old. The singular in the word year agrees with the head noun, boy, when used attributively.

Next, some of the participants commented that if the word university or vehicle was in the genitive form (university’s or vehicle’s), it would be grammatically correct. This type of compound with two constituents is called a genitive compound (Mukai 2008, 2018), a compound with an element that looks like a genitive case marker, but the element does not function as such. This element does not carry possessive meaning. The non-head of this type of compound serves to classify the whole compound (Shimamura 2014). This comment supports what (61) shows. In contrast, however, for compound (65e), the average score for the test was 5.24, which signifies that nearly all the participants allowed systems. As discussed in Section 4.2, the word systems can be used as a modifier of compounds along with system. This word, however, is not semantically plural but only has an attributive usage, as discussed in Section 4.2.

The results of the plural tests and modification tests suggest that recursive compounds behave as words, whereas the results of coordination tests do not. Thus, there arises a problem of how inconsistency is resolved. One possible way out is to assume that and can be a linking element, which forms a complex word. This kind of recursive compound allows for coordination and corresponds to the coordinate compound called dvandva. Dvandva is said not to be allowed in English (e.g., *hand-leg), whereas in Japanese, the words are said to be productive (e.g., te-ashi hand-leg ‘hand and leg’). When the coordinator and is between the constituents, dvandva compounds are also allowed in English (Yonekura et al. 2023). Thus, hand-and-leg and bed-and-breakfast are allowed. Thus, the results of the coordination tests in our experiment indicate that there is a dvandva compound embedded in recursive compounds, with a linker or a coordinator inside between the two constituents of the embedded compounds. Di Sciullo (2009, p. 152) suggests that a functional head, F, is there between the two constituents for interface interpretability conditions. She claims that the example bed-and-breakfast can be considered a coordinate compound in English.

5.3. Phonological Properties

- (4c) Research Question 3

Do recursive compounds in English obey the Lexical Category Prominence Rule? If so, to what extent? If not, are there any patterns?

The simple answer for RQ3 is that some compounds obey the LCPR for both left-branching interpretations, whereas compounds with right-branching interpretations do not (Section 2.3). We found that the results showed different patterns for the male and female participants (see Appendix B for more details). Thus, we discuss the different results for the different genders in this study. By considering previous studies on the LCPR, we find patterns for the variation and discuss them one by one in detail. To explain the patterns for the variant results, we checked the pronunciation in dictionaries, such as the Cambridge Dictionary and Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

5.3.1. Obeying the LCPR

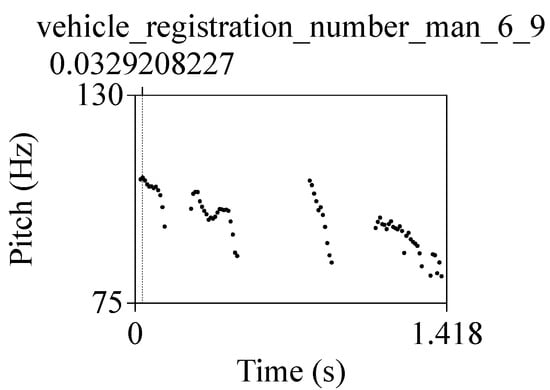

We start with the results for the compounds with left-branching interpretations. According to the LCPR (see (16)), N1 had the highest prominence, and this was observed among the male participants for infant mortality rate, hot water bottle, soil conservation program, vehicle registration number, and strawberry and rhubarb pie. For the female participants, it was obeyed in system development process, vehicle registration number, and strawberry and rhubarb pie. Interestingly, for soil conservation program, the same number of male participants was assigned the same pitch of prominence on both N1 and N2, so the LCPR was obeyed and disobeyed by different participants. Almost all the other compounds seemed to disobey this rule. Below, we show one of the male participant’s pitch track of vehicle registration number.

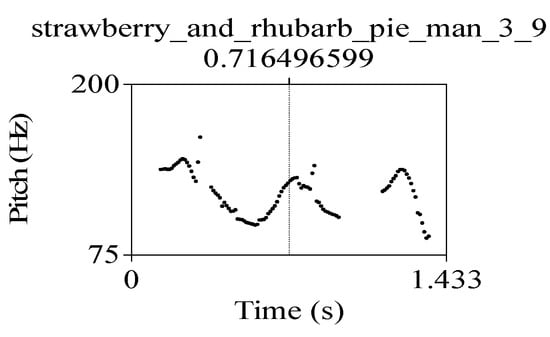

For strawberry and rhubarb pie, as Figure 3 shows, the interpretation was that the embedded compound strawberry and rhubarb was that of a coordinative compound (Section 5.1). Coordinative compounds follow phrasal stress (Kubozono 1999, p. 78). However, according to our participants’ prominence patterns, the compound strawberry and rhubarb behaves like a left-branching compound. Observing the acoustic patterns for recursive compounds with embedded coordinative compounds like this compound would be interesting. This should be considered for future research. Furthermore, Figure 4 shows the acoustic pattern of vehicle registration number, which is the case of obeying the LCPR.

Figure 3.

Pitch track of strawberry and rhubarb pie.

Figure 4.

Pitch track of vehicle registration number.

5.3.2. Disobeying the LCPR with N2 as the Highest Prominence

Next, our study found a few compounds with left-branching compounds that disobeyed the LCPR, with N2 as the highest prominence. The compounds were cancer research center for the male participants and infant mortality rate and soil conservation program for the female participants. Thus, the female participants seem to disobey the LCPR more than the male participants. For these compounds, most of the participants pronounced N2 as the highest prominence. This result, that some left-branching compounds have the highest prominence on N2, is also indicated by previous findings, such as those by Giegerich (2009) and Kösling (2012).

Giegerich argues that the predictions made by LCPR are wrong (Giegerich 2009, p. 10) and gives some left-branching compounds with embedded right-prominent NN compounds. The embedded compounds themselves disobey the Compound Stress Rule, and this pattern is maintained in the recursive compounds, such as [[toy car [collection] and [[school office [manager]. We also show whether our results show a similar pattern, i.e., the embedded NN in the left-branching compounds disobeys the Compound Stress Rule.

None of the dictionaries have an entry for the compound cancer research as an embedded NN compound in cancer research center. We then asked a native speaker to pronounce the compound, and according to him, this word obeys the Compound Stress Rule. Therefore, we cannot argue that the embedded right-prominent NN compound is retained in the NNN.

In contrast, some of the dictionaries show soil conservation and infant mortality. Though the former word assigns N1 with its highest prominence, obeying the Compound Stress Rule, the latter marks N2 with its highest prominence, thus leading us to argue that this pattern is maintained in the NNN compound of infant mortality rate. In addition, the whole string infant mortality rate, N2, has the primary accent marked in the dictionaries. For this compound, then, what Giegerich argues is correct.

Is there any other explanation for cancer research center, soil conservation program, and data management system for violating the LCPR? Giegerich (2009) argues that the violation of left-branching compounds may be explained in terms of semantics. N1 is [N2 + N3]’s place or time, N1 for [N2 + N3], and N1 has [N2 + N3]. The semantic relationships between [cancer research] and center, [soil conservation] and program, and [data management] and system can be explained by N1 for N2, which is also observed in the interpretation by eight of our participants ‘computer storage system (system) for information (data management).’ In addition, for the compound soil conservation program, the 14 participants interpreted it as ‘program for conserving the soil (using different wordings).’ Thus, for these words, what previous studies suggested is right. However, it is clear that we need more data to support our argument.

5.3.3. Gender-Based Variations

For the rest of the compounds and female or male participants, we could not find any patterns, although there were a number of compounds that observed the highest prominence on N2, with fewer participants than N1 among both male and female participants. For male participants, data management system, soil conservation program, and system development process are examples. For female participants, currency exchange rate and sea surface temperature showed N2 with the highest prominence but among fewer participants than N1. Again, a higher number of participants obey the LCPR, but the rest do not. These words seem to have the interpretation N1 for N2, e.g., a system for data management (as discussed in the above paragraph), a program for conserving the condition of the soil (earth), and the temperature of the sea surface. However, this is only a tendency, and clearly, we need more data with the same result to conclude the semantic pattern and explain the violation. In addition, since we did not systematically code the data for semantic relations or semantic categories, this assumption requires further support with systematic collection of the data. What about all the other compounds? We could not find any other systematic patterns for them. The results with variations are in line with the previous literature.

Secondly, we discuss the results for the compounds with right-branching interpretations: carbon footprint, hot cross bun, and Christmas party hat (more people than left-branching). The LCPR predicts the highest prominence on N2 for right-branching compounds (Section 3.2). None of the three compounds obeyed the LCPR by either sex. For example, carbon footprint had the highest prominence on N3 for the male participants, with a lower number than N2, and for women, N3 had a lower number than N1. To see if there were any explanations for these variations, we checked the aforementioned dictionaries for the pronunciations of these compounds. In fact, our participants’ prominence patterns aligned with what the dictionaries describe, i.e., the stress mark is written on the first syllable of N3.

Is there any explanation for this violation? Giegerich (2009) gives some examples of right-branching with the highest prominence on [N1 [N2 N3]]. To explain this violation, Kösling (2012) argues that they all provide the semantic pattern of N1 for N2, for example, tomato green-house, grain store-room, steel ware-house, and owl nest-box. They are all interpreted as, for example, green house for tomatoes. Although our results show the highest prominence on N3, not N1, like Giegerich or Kösling, we considered whether the target compounds provide any semantic pattern between the constituents. Christmas party hat, for example, was paraphrased by some of the participants as ‘a party hat which is worn during Christmas Day (or time).’ Hot cross bun is ‘a pastry with a cross on top, served hot’, which is a similar semantic pattern to Christmas party hat, i.e., N2 + N3 for N1. In the Cambridge Dictionary and Merriam-Webster Dictionary, the first syllable of N2 in carbon footprint is accented, so some of our participants did not even follow it. The interpretation is, however, that none of the patterns are presented by Giegerich. It is simply interpreted as the footprint produced from the emission of carbon. We cannot find any other explanations. For this compound, however, a higher number of our participants did follow the LCPR.

We need more data with the same result to conclude the semantic pattern and explain the violation.

In summary, our test empirically supports the fact that the LCPR is obeyed for some of the compounds, but for most of the compounds, it is not obeyed. The LCPR does not decide the branching direction, as Giegerich (2009), Kösling (2012), and Kösling et al. (2013) suggest with their empirical tests. In addition, we also showed that some of the violations seem to be explained by semantics or the violations of the embedded NN. A syntax–phonology mismatch was observed both for right-branching and left-branching recursive compounds. Our hypothesis for the phonological criterion is valid.

6. Conclusions

The main aim of this study was to capture the properties of recursive compounds, focusing on their semantic, syntactic, and phonological properties. We used the analyses of two-member compounds in the previous literature. To achieve this aim, we conducted empirical tests on the semantic, syntactic, and phonological properties of recursive compounds after collecting 13 different words from Huber (2023) and 7 from other sources. Our participants were from British- and American-English-speaking backgrounds. In total, there were 23 participants, including one British control participant. The results show that the target recursive compounds in English have left-branching interpretations, although there were some variations among the participants. In addition, three of the target compounds had right-branching interpretations. In addition, for the syntactic properties, the test showed that recursive compounds contain a coordinate inside while obeying the lexical integrity test. Additionally, we suggest that not allowing internal modification inside compounds is due to the fact that the non-heads of compounds are considered ‘adjectives’, which classify a specific type of nouns. In addition, we argued that the disallowance of plural inflection inside recursive compounds is due to the covert agreement between the non-head (considered to be an attributive adjective by the participants) and its head. Finally, for the phonological test, there were variations among the participants for almost all of the recursive compounds. We found some patterns in the variations, and some of the left-branching compounds obeyed the LCPR. However, most compounds disobeyed what the LCPR predicts, especially those with right-branching interpretations. These results are in line with those of the previous studies discussed.

To the best of our knowledge, there has been no sufficient or established account for recursive compounds to explain all of these properties, which was the aim of this study. We hope that our analyses will be applicable to recursive compounds in other languages and provide hints about linguistic theories. These are implications for future research.

Funding

This research was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number JP22K00512).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Ethics Committee of the author’s university (Receipt Number 23-02 and 3 August 2023) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. They were all allowed to withdraw from the study at any time.

Data Availability Statement

The collected data are unavailable due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and academic editors for their valuable comments and insightful feedback. We would also like to thank Chisaki Fukushima, and Hitoshi Mukai for their help on helping me get participants for the experiment. We would also like to thank Rebecca Dodgson for proofreading this paper. Finally, we would like to acknowledge the 23 participants’ help in completing this study and giving informative comments on the content of the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

The content of the study

The Consent Letter to the participants

- This study examines how English, Swedish, and Japanese native speakers interpret compound words comprising three words (e.g., peanut butter sandwich).

- What does the study involve?

This study consists of two parts. The study will last approximately 40 min, and each part’s content and estimated completion time are specified below.

Interpretation Test: You will read 20 English expressions consisting of three words (e.g., peanut butter sandwich), presented one by one. This test is divided into two parts: Test a and Test b.

- Your task is to record your voice by reading a sentence provided involving the expression of each expression (so, please use a microphone and recording system on your laptop or computer to record your voice); e.g., I am eating a peanut butter sandwich.

- Your task is to answer the following two questions.

- (1)

- How do you interpret the expression?

- (2)

- How natural do you find the expression within a longer phrase (please judge on a scale of 1–7, where 1 means ‘totally unnatural’, and 7 means ‘perfectly natural’)?

This test takes approximately 20 min to complete.

Participant questionnaire: This questionnaire asks you about your language background. This task takes about five minutes to complete.

- C.

- What will happen to the data I provide?

The data will be used together with the data of other participants to examine features of three-word expressions. The data will be sorted on a password-protected computer belonging to the researcher. It may be stored for longer than five years. Your responses will remain strictly confidential. The data are collected in such a way that anonymity is secured. The information collected in this study will be used in the preparation of papers for presentation in international conferences and journals concerned with linguistic research.

- D.

- Can I withdraw from your study? If, during your participation, you decide that you no longer wish to proceed, simply close the webpage to withdraw from the study. Please note, though, that withdrawing from the study will not be possible after completing the final task. This study is run in compliance with the researcher’s Ethics Committee and will respect all your rights as described therein. For any questions about this study, contact the researcher.

I agree: I have read and understood the above and hereby give my consent to take part in this experiment in full knowledge that data are being recorded.

- Test a: Recording Test

Say the sentence on the screen out loud three times in a clear voice:

- (1)

- This is a party membership card.

- (2)

- This is a sustainable soil conservation program.

- (3)

- We are reducing our carbon footprint.

- (4)

- I am wearing a Christmas party hat.

- (5)

- This place offers a drug rehabilitation program.

- (6)

- We use this data management system.

- (7)

- We have the highest infant mortality rate in Africa.

- (8)

- I am eating some hot cross buns.

- (9)

- This building is cancer research center.

- (10)

- This is the air traffic control system.

- (11)

- I have my vehicle registration number.

- (12)

- Here is the office lunch bill.

- (13)

- This summer saw the highest sea surface temperatures.

- (14)

- I am eating a strawberry and rhubarb pie.

- (15)

- We know the university entrance exam.

- (16)

- This is a hot water bottle.

- (17)

- Here is today’s currency exchange.

- (18)

- This course offers English language teaching.

- (19)

- We know the system development process.

- Test b: Semantic Interpretation

What is the meaning of the expression? Please write what you think intuitively and do not take too much time.

- (1)

- English language teaching

- (2)

- party membership card

- (3)

- carbon footprint

- (4)

- Christmas party hat

- (5)

- drug rehabilitation program

- (6)

- data management system

- (7)

- infant mortality rate

- (8)

- hot cross bun

- (9)

- cancer research center

- (10)

- air traffic control system

- (11)

- vehicle registration number

- (12)

- office lunch bill

- (13)

- sea surface temperature

- (14)

- strawberry and rhubarb pie

- (15)

- university entrance exam

- (16)

- hot water bottle

- (17)

- currency exchange rate

- (18)

- system development process

- (19)

- elephant danger zone

- (20)

- soil conservation program

- Test c: Interpretation Test (Syntactic Test)

How natural do you find the expression within a longer phrase (please judge on a scale of 1–7, where 1 means ‘totally unnatural’, and 7 means ‘perfectly natural’)?

- (1)

- English language and French language teaching

- (2)

- labor party membership card

- (3)

- carbon feetprint

- (4)

- Christmas party and sun hat

- (5)

- drug and alcohol rehabilitation programs

- (6)

- data and finance management systems

- (7)

- infant and elderly mortality rate

- (8)