Abstract

The intense contact between Guarani and Spanish in the Argentine province of Corrientes has produced a wide array of mutual contact effects, the most visible being widespread borrowing in both directions. This article examines a previously unreported feature of Argentine Guarani loans in Correntino Spanish: the social value they have acquired. Building on the growing body of work in sociolinguistics on internet memes, which are sites of phenomena rich in sociolinguistic value, an analysis is provided of Argentine Guarani loans in Correntino Spanish using an original corpus of memes collected from Correntino Instagram pages. Such memes, whose intended audience is monolingual, are a valuable source of Correntino Spanish features, which are used for humorous, ironic, or nostalgic effect. Via analysis of the relationship between these loans and the kinds of memes they appear in, I show that these loans have undergone enregisterment, i.e., they have taken on additional social meaning that allows them to index a complex variety of ideological stances toward Correntino social phenomena and character types. The results of this process evidence the fact that language contact, as an engine of variation, creates fertile ground for the emergence of social meaning and that memes are a productive and promising window into the (re)creation and evolution of such meaning.

1. Introduction

The scholarly treatment of language variation has evolved since variationist analysis began in earnest in the mid-twentieth century. Variationist studies are commonly grouped into three “waves” (Eckert 2012), delineated by differing theoretical treatment of the emergence of social meaning in variation and shifting approaches to speaker agency. As Hall-Lew et al. (2021, p. 1) summarize:

Traditional first- and second-wave approaches have treated variation as a window into language change (Weinreich et al. 1968), and have examined the stratification of variation according to both macrosocial categories (e.g., gender, class) and locally significant categories (e.g., jocks, burnouts). Proponents of a third-wave approach focus on linguistic variation as a resource for taking stances, making social moves, and constructing identity.

Approaches in the third (and current) wave, by virtue of their emphasis on the role variation plays in the construction of social categories as opposed to being mere by-products of them, offer important insight into the use of contact features in Correntino Spanish, a variety of Spanish unique to the Argentine province of Corrientes. Correntino Spanish is notable among Spanish varieties for the myriad ways in which it has affected and been affected by Argentine Guarani1 (Cerno 2017; Dietrich 2002), a variety of Guarani unique to Corrientes (closely related to but historically and linguistically differentiated from Paraguayan Guarani). Due to a complex mixture of sociohistorical and ideological factors, Correntinos find themselves situated geographically, culturally, and linguistically between Paraguay and Buenos Aires, the latter being the perceived core of Argentine culture throughout Latin America. The linguistic hallmarks of the province—Spanish-influenced Guarani and Guarani-influenced Spanish—are in many ways maligned by non-Correntinos and Correntinos alike, with Argentine Guarani characterized as an illegitimate variety of Guarani, not as “pure” as the variety spoken in Paraguay, and Correntino Spanish similarly characterized as an “impure” variety of Spanish (Pinta 2022). This overtly linguistic discrimination of Corrientes and its inhabitants, discursively justified on grounds of language purism, is inevitably linked to the social characteristics of the province, which is seen by many non-Correntino Argentines—in particular by porteños, i.e., citizens of Buenos Aires—as a socially backwards province characterized by poverty and superstition. An understanding of the social environment of Correntino Spanish (and Argentine Guarani) helps elucidate the linguistic phenomena that make the province unique, phenomena drawn from a diverse and rich pool of linguistic resources which are recruited by speakers in myriad ways to achieve myriad social ends.2

While the list of linguistic features that make Correntino Spanish unique as a variety goes beyond contact effects, the influence of Guarani on this variety is uncontroversially the most important of its delineating characteristics, some but not all of which are shared by Paraguayan Spanish and very few of which are shared by other Spanish varieties spoken in Argentina. Guarani-source contact effects are found in all areas of the grammar, the most visible, of course, being the lexicon. In this article, I examine a previously unreported feature of Argentine Guarani loans in Correntino Spanish: the social value they have acquired. Via analysis of an original corpus of internet memes collected from Correntino Instagram pages, I draw connections between the use of Guarani loans and the thematic patterns of the memes they appear in. I show that Guarani loans have undergone enregisterment (Agha 2003), i.e., that they have taken on additional social meaning which allows them to index a complex variety of ideological stances toward Correntino social phenomena and character types. This study therefore not only addresses social meaning in the context of third-wave sociolinguistic analysis generally but also foregrounds the role that contact features play in the accrual and deployment of social meaning in communities whose linguistic repertoires are the products of intense language contact.

Such social meaning is malleable and subject to context-specific interpretation. In Correntino internet memes, Guarani loans may in one meme be used in a fond, nostalgic manner while in another be used in the service of self-deprecating humor. They can be differentially associated with the romanticized ideal of the Correntino gaucho, i.e., the hard-working family man who is a skilled horse rider, expert in agricultural matters, master of the outdoors, and dependable head of household, as well as the Correntino womanizer, i.e., the smooth-talking, often heavy-drinking bender of the truth who is trusted by neither his romantic partner nor close friends. In their discussion of the connection between linguistic forms and social meaning, Hall-Lew et al. (2021, p. 5) note that “[t]he social meaning(s) that listeners arrive at, however vaguely, can only be determined in the moment of use, dependent on the particular ideologies made relevant in context”. This notion will prove crucial to an understanding of the varied and sometimes contradictory types of social meaning which Guarani loans are linked to, as will be further developed below.

This article is structured as follows. Section 2 provides the background necessary to situate the study, addressing both its theoretical grounding and internet memes as objects of inquiry. In Section 3, methodological details are provided, including the composition of the meme corpus on which this study is based and the analytical approach adopted here. Section 4 contains a thematic analysis of the memes in the corpus, followed by Section 5, in which the phenomena in the corpus are linked to the previous literature discussed in Section 2, demonstrating how these patterns inform our understanding of the social value of Guarani loans in Correntino Spanish generally. Finally, the article concludes with summarizing remarks in Section 6.

2. Background

2.1. Enregisterment, Indexical Fields, and Character Types

The nature of the relationship between linguistic variables, speech styles, and social categories has been at the heart of much of the work within third-wave sociolinguistics and a crucial theoretical framework used to understand the mechanism by which linguistic variables become meaningful social objects has been that of enregisterment. First used and defined by Agha (2003, p. 231) as “processes through which a linguistic repertoire becomes differentiable within a language as a socially recognized register of forms”, the process of enregisterment produces an identifiable relationship between linguistic features and social categories. The acquired social value of such features in turn demarcates them in important ways from other features that are part of the same linguistic system. The attribution of social value to a speech variety is contingent on the enregisterment of a subset of linguistic features of that variety, with the members of the subset being a class subject to constant reinterpretation and, over time, addition or subtraction. Agha (2003, p. 232) notes that such cultural value “is not a static property of things or people but a precipitate of sociohistorically locatable practices, including discursive practices, which imbue cultural forms with recognizable sign-values and bring these values into circulation along identifiable trajectories in social space”. As will be shown later, Correntino Spanish memes provide a unique and relatively novel window into the ways in which linguistic features that have come to acquire such social value are used and understood.

The theory of enregisterment has been applied to a number of sociolinguistic case studies since its introduction nearly 20 years ago. (For a variety of examples, see the 2009 special issue of American Speech, vol. 84, no. 2.) Zhang (2021) discusses the enregisterment of Cosmopolitan Mandarin, a novel style of Mandarin that is shown to participate in the creation of new social distinctions as opposed to being a mere product of them. In her analysis of the enregisterment of the distinguishing features of this variety, Zhang (2021, p. 281) notes “that the emergence of [Cosmopolitan Mandarin] is a contested process fraught with indexical instability and multiplicity, a process whereby [Cosmopolitan Mandarin] and its constitutive elements are imbued with varied and often conflicting indexical values”. This resulting set of conflicting values mirrors what occurs in Corrientes, as will be further elaborated on below.

Another well-known application of enregisterment is its use by Johnstone et al. (2006) in their analysis of a set of linguistic features unique to the variety of North American English spoken in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. They provide a classification of variable indexical meaning via analysis that combines a taxonomy of social meaning proposed by Labov (1972) with the orders of indexicality proposed by Silverstein (2003).3 They show that some features of “Pittsburghese” have gone through a three-step process: (1) acquiring first-order indexicality (i.e., becoming an “indicator”), by which they are regionally correlated with a group of speakers but not overtly recognized as such; (2) acquiring second-order indexicality (i.e., becoming a “marker”), by which speakers become aware of a connection between such features and locality, therefore allowing the features to become available for social work; and (3) acquiring third-order indexicality (i.e., becoming a “stereotype”). Once features acquire third-order indexicality, the conditions are created for speakers (and even non-speakers) of a given variety to “use regional forms drawn from highly codified lists to perform local identity, often in ironic, semiserious ways” (Johnstone et al. 2006, p. 83). Memes, as discussed below, provide a clear window into both the recruitment of features for such use and the end result of the set of social meanings they can acquire.

Such a set of meanings, which speakers draw from and alter according to their own ideological stances, constitute what Eckert (2008) calls an “indexical field”, or a non-static constellation of meanings which are linked ideologically. Building on the influential work of Silverstein (2003) on indexicality and indexical orders, Eckert proposes indexical fields as a way of accounting for constantly shifting social meanings associated with a synchronically static set of linguistic features, noting that indexical fields are “fluid, and each new activation has the potential to change the field by building on ideological connections” (Eckert 2008, p. 454). Experimental work by Campbell-Kibler (2007) demonstrates this fluid nature of indexical fields by showing that listener evaluations of the social meaning of enregistered features—in the case of this study, the rendering of the morpheme -ing in US English as either [In] or [IN]—is malleable according to context. She notes that the use of the former variant “influences the perception of education across multiple speakers on the one hand, and in a subset of the speakers also affects an accent associated with lack of education”, going on to stress that such seemingly paradoxical interconnections “are a fundamental aspect of sociolinguistic variation” (Campbell-Kibler 2007, p. 55).

The variation in interpretation of the social value of enregistered features further allows for the same features to be associated with differing speech styles, and subsequently, differing stereotypes of who uses such features. This phenomenon has been addressed in work on “character types”—sometimes used synonymously with “characterological figures” (Agha 2007, p. 177) or “personae” (Drager et al. 2021, p. 176)4—i.e., “stereotypical, reified figure[s] such as the California ‘Valley girl,’ often circulated via mass media” (Starr 2021, pp. 315–16). A crucial component of character types, as noted by Agha (2007, p. 177), is that they are “performable through a semiotic display or enactment (such as an utterance)”. That is, one end product of the process of enregisterment is that a set of enregistered features can be drawn on in the portrayal of stereotypical figures in ways that are locally meaningful. These representations are linked to larger societal characteristics that manifest themselves in individualized representations. As Eckert (2016, p. 75) notes (using “personae” in lieu of “character types”): “The attention to personae shifts the focus away from the social aggregate to individuals as they move through identities and situations. However, it does not amount to a study of the individual, but of the structure within which individuals find and make meaning”. Internet memes are a productive medium for the reproduction of such character types, which are construed via use of enregistered features, as further discussed below.

2.2. Memes as Objects of Analysis

Recent years have seen the emergence of internet memes as objects of sociolinguistic interest and analysis, in line with a growing awareness of memes as sites of phenomena rich in sociolinguistic value. Such value emerges both from the linguistic features that surface in these contexts but not in formal writing contexts and from the content of the memes themselves, which is often a valuable source of sociocultural references. A comparison could be made to the value of the colloquial Latin graffiti at Pompeii, which provides a source of linguistic and sociocultural information not available in more formal texts (Jones 2016). In the same way, memes can provide a space for colloquial, informal linguistic features—precisely the kinds of features that are so often imbued with social meaning—which might not appear in other written contexts.

The term “meme” was first coined by Dawkins (1976), who used it within the context of evolutionary biology, contrasting memes with genes.5 Taking Dawkins as a starting point, Davison (2012, p. 122) discusses the transition to the modern meaning of “meme”, ultimately providing his own definition:

In Dawkins’s original framing, memes described any cultural idea or behavior. Fashion, language, religion, sports—all of these are memes. Today, though, the term “meme”—or specifically “Internet meme”—has a new, colloquial meaning. While memes themselves have been the subject of entire books, modern Internet memes lack even an accurate definition. There are numerous online sources (Wikipedia, Urban Dictionary, Know Your Meme, Encyclopedia Dramatica) that describe Internet memes as the public perceives them, but none does so in an academically rigorous way. Given this, I have found the following new definition to be useful in the consideration of Internet memes specifically: An Internet meme is a piece of culture, typically a joke, which gains influence through online transmission.

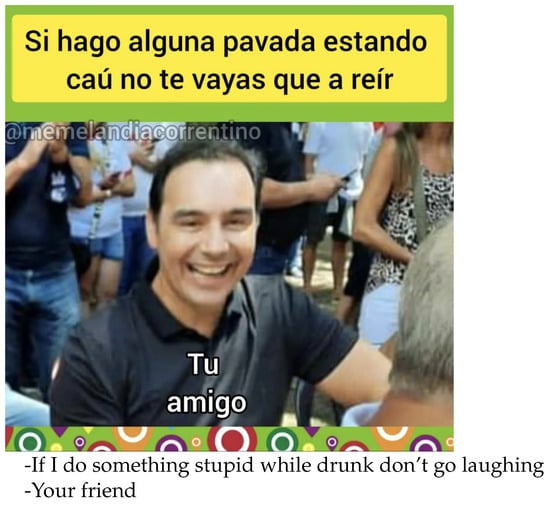

To narrow the definition even further, internet memes are understood in popular culture as being images (or sometimes short videos, gifs, or chunks of text), often with accompanying captions, and this is the sense in which “meme” is used here. An example of a meme from the corpus (whose composition will be discussed in detail in Section 3.1) is given in Figure 1, with an English translation provided immediately below it. Two Guarani loans are found in this meme: caú ‘drunk’ (from Guarani ka’u) and que, an intensifier particle used in imperative contexts (from the Guarani form ke, whose phonetic realization and function are the same as the Spanish borrowed form).

Figure 1.

Example of a meme from the Correntino Spanish meme corpus containing the Guarani loans caú ‘drunk’ and que, an imperative intensifier particle.6

The key consideration for this analysis is not what does and does not count as a meme7 but rather that a central property of memes is their sociocultural relevance, often to narrow or relatively small social groups. Such memes must necessarily be created by a member of such a social group (or someone with a thorough understanding of the group norms and values) and are likely to only be fully understood or appreciated by a member of the same group. For instance, while the general content of the meme provided in Figure 1 is easily interpretable by anyone, there is an additional layer of content that grounds the meme locally: the man laughing in the photo is the current governor of Corrientes, Gustavo Valdés.

As Shifman (2011, pp. 188–89) points out, “[O]nly memes suited to their socio-cultural environment will spread successfully; the others will become extinct…While some memes are global, others are more culture specific, shaping collective actions and mindsets”. In bringing up the notion of a meme’s success, Shifman refers to the propensity of a meme to be shared and to spread, either in its verbatim form or in an evolved form in which someone else reproduces the template and aesthetic but changes the joke. The ability of a meme to evolve, and the agency of the individual in the reinterpretation and redesign of a meme, is a crucial factor in a meme’s “virality”, or ability to spread quickly (Varis and Blommaert 2015), but a meme’s sociocultural relevance is ultimately the most important factor in determining its success. Knobel and Lankshear (2007, p. 209), in an early analysis of memes, comment on this as well, noting that one of the most important factors in the success of a meme is that it have “[a] rich kind of intertextuality, such as wry cross-references to different everyday and popular culture events, icons or phenomena”.

This “rich kind of intertextuality” can manifest itself culturally, linguistically, or both. For this reason, memes are often treated as a unique genre, with Wiggins (2019, p. 40) clarifying, “[A] meme, viewed as a genre, is not simply a formula followed by humans to communicate, but represents a complex system of social motivations and cultural activity that is both a result of communication and impetus for that communication”. It is precisely this property of memes that has drawn the attention of sociolinguists, combined with the fact that the common tools of linguistic analysis are extremely well suited for the analysis of memes (Cochrane et al. 2022).

Meme analysis in sociolinguistics, a subset category of the larger body of work addressing language in computer-mediated contexts (e.g., see Squires 2016), has proven a valuable approach in a variety of cases. Ndoci (forthcoming), for instance, via analysis of Greek memes, demonstrates how the construction of the Albanian immigrant stereotype is propagated via memes that utilize stereotyped features of the L2 Greek of Albanians. Members of Greek society without direct interaction with Albanian immigrants thus become aware of a link between these features and social notions of Albanians in Greece, subsequently further propagating harmful stereotypes via the resulting mock language (Hill 2007); memes provide a vehicle for such a phenomenon, which would not be possible otherwise among Greeks without direct exposure to such linguistic features.

Other studies have looked at how specific memes have accrued complex social meaning. Aslan and Vásquez (2018) analyze the “Cash me ousside/howbow dah” meme—a meme based on an utterance produced by a teenage girl on an American talk show in 2016—and the ways in which it indexes a variety of differing social meanings and categories. Drawing on the notion of “citizen sociolinguistics” (Rymes and Leone 2014), an approach that focalizes the participation of non-linguists in sociolinguistic exploration, they analyze metalinguistic commentary on YouTube videos to show how race, region, education, and class converge in the interpretation and reproduction of this meme, noting “that these categories overlap in complex, and not always predictable, configurations” (Aslan and Vásquez 2018, p. 406). Similarly, Procházka (2019) demonstrates how memes index a complicated mixture of ideologies via analysis of the “countryball” meme comics, which soared in popularity during the European migrant crisis. Countryball memes involve simplistic drawings of ball-shaped characters whose color patterns resemble the flags of different countries and whose linguistic and behavioral characteristics are satirized representations of sociocultural stereotypes associated with the countries they represent. The use and interpretation of these memes, located in the context of anti-immigrant and nationalist ideologies, resist a simple good-bad binary and evidence more complicated and overlapping ideological positions that are highly individualized. The analysis provides an important case study of memes as valuable and informative sociolinguistic objects of modern inquiry, concluding that “memes are not a mere product of participatory culture, but rather a powerful instigator of technosocial and often heteroglossic practices that co-organize social life in the new polycentric collectivities appearing on social media” (Procházka 2019, p. 717).

Drawing on these studies and the growing body of literature on memes in general, this study provides a novel analysis of the use of Argentine Guarani loans in Correntino Spanish memes. The uniqueness of Correntino Spanish combined with the particularly strong sense of Correntino identity allows for a sociolinguistic context that produces a complicated array of phenomena. As discussed in these previous analyses of memes, the linguistic features in question here, i.e., Argentine Guarani loans, are used in the service of a variety of seemingly conflicting ideological stances, themselves rooted in the contrast between local identity and the larger categories of porteño and Paraguayan identities. Correntino identity is forged simultaneously by drawing on aspects of these larger identities and by reinterpreting those aspects in opposition to them. Memes provide an easily accessible and easily malleable resource by which to produce and reproduce ideological stances about what is and is not “Correntinoness”. To demonstrate this, a unique corpus of Correntino Spanish memes was created, the composition of which is discussed in the following section.

3. Methodology

3.1. Meme Corpus

The data informing this study come from a corpus of 409 unique memes, all in Correntino Spanish, compiled from 2020 to 2022. The criterion for inclusion in the corpus was whether or not a given meme contained at least one Guarani loanword. However, given that the goal in creating the corpus was to focus narrowly on Correntino Spanish, all Guarani loanwords that have entered Argentine Spanish broadly conceived were left out. The criterion for establishing this categorization was made on the basis of the geographic diffusion of a given loan. Guarani loans that are common in the urban variety of Spanish spoken in Buenos Aires, such as loans for animal names (e.g., yacaré ‘caiman’), placenames (e.g., Iguazú, the name for Iguazu Falls), and other various loans (e.g., tereré, yerba mate drunk cold), were excluded from the corpus, as they are not emblematic of local speech and thus not available for explicit connection with Correntino culture and identity in the same way. The assessment of whether or not a given Guarani-source form is common in Buenos Aires was made on the basis of my own high degree of familiarity with that variety and, in cases of doubt, in consultation with native speakers of non-Correntino Argentine Spanish varieties.

The sources of the memes are 11 Instagram pages that are run by Correntinos and intended for Correntinos; these pages were chosen via an in-depth survey of Correntino Instagram pages, and all pages that were thematically locally oriented were included. These pages, along with their Instagram handle,8 number of followers, and the location out of which each page is run, are provided in Table 1. Additionally, a map of the province is provided in Figure 2, in which each of the locations in Table 1 is indicated. Some pages contributed more memes to the corpus than others, as some were much more prolific and active in posting than others. The number of memes from each specific source page is found in Figure 3.

Table 1.

The 11 Instagram pages from which the 409 memes comprising the Correntino Spanish meme corpus were sourced, along with their Instagram handles, the number of followers as of 27 October 2022, and the city/town out of which the page is run.

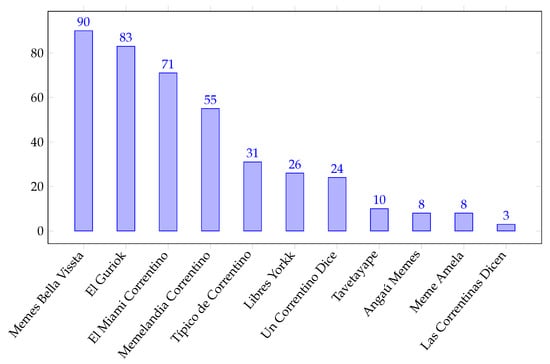

Figure 3.

Number of memes taken from each individual Instagram source page (total: 409).

The process of “collecting” a meme involved manually identifying it as containing a loan, screenshotting it, saving it, categorizing it by page of origin, and entering it into a database in Excel. Each meme was coded for the amount of loans it contained, what the loans were, whether the loans were morphosyntactic or lexical, and whether or not the content of the meme made explicit reference to Correntino identity or culture (discussed further in Section 3.2). Specific URL sources for each of the memes reproduced in this article are given in a footnote at the bottom of the page on which the meme appears, alongside the name of the account from which the meme was taken.

It is worth noting that the corpus here is not exhaustive in the sense of representing each and every meme across all 11 Instagram pages that contains a Guarani loan. Given that memes were collected manually, fully exhausting all 11 pages was beyond the scope of this study (for example, Memelandia Correntino alone contains well over 14,000 memes). However, many of the pages with smaller meme counts were fully exhausted, and in the cases of pages such as Memelandia Correntino, memes were not cherry-picked, as each collecting “session” consisted of searching an uninterrupted stretch of memes from a given page. This strategy mirrors the common approach in spoken speech analysis in which an uninterrupted stretch of speech is examined in order to extract all occurrences of a given variable. In such a stretch, all memes that contained a Guarani loan (other than those Guarani loans that have entered the general Argentine Spanish lexicon, as discussed above) were collected. Generally speaking, most memes from these pages do not contain Guarani loans, and memes without loans were ignored.10

Various memes contained more than one loan. Given this, the corpus contains 409 memes but 498 loans. Within these 498 loans, a basic division can be made between grammatical loans (i.e., borrowed morphemes, such as epistemic particles or evidentials, whose function is morphosyntactic) and lexical loans (i.e., borrowed nouns and adjectives). Of the 498 loans, 268 (53.8%) are grammatical and 230 (46.2%) are lexical.

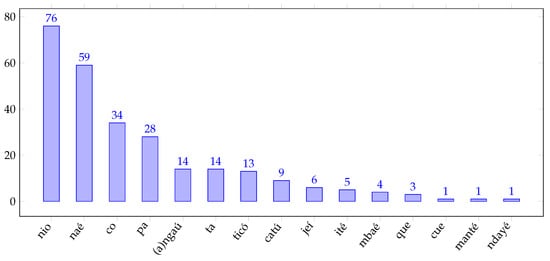

The lexical loans from Guarani in Correntino Spanish are numerous, and the corpus reflects this, with a wide variety of loans being represented from various semantic fields. The grammatical loans, however, are more restricted, with 15 total being registered in the corpus. The number of occurrences of each is given in Figure 4, followed by a description of the Guarani source form and the meaning of the resulting Spanish loan in Table 2.

Figure 4.

The number of occurrences of each of the 15 grammatical loans registered in the corpus. The Guarani source forms for each can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

All 15 grammatical loans found in the corpus, by order of frequency (see Figure 4), along with the Guarani source form and the general meaning of the resulting Spanish form.

With regard to the meaning of each grammatical loan, it is important to mention that the precise semantics of these loans is highly nuanced and contextually specific. No studies have provided an in-depth description of their semantics or pragmatics, and careful work is needed to provide a satisfactory account of how they are used synchronically and how they have evolved diachronically. Most of them strongly resemble the subset of discourse particles often called “modal particles” in other languages. These particles, best known from Germanic languages (in particular German, e.g., ja, doch, halt, etc.), are uninflected words usually confined to conversational or informal contexts that make subtle pragmatic contributions to a given utterance.11 Karagjosova (2004, p. 20) notes,

The meanings of [modal particles] are abstract and difficult to generalise over their particular contexts of occurrence and are usually explicated in terms of the propositional attitudes of their speaker. [Modal particles] can be omitted without influencing the truth value of their carrier sentence. They are typically used in dialogues and as such are primarily oriented towards the addressee and his preceding utterance.

Waltereit’s (2001, p. 1392) description of modal particles addresses another commonly reported characteristic, that of their elusive meaning:

[Modal particles] usually cannot carry stress, they cannot be coordinated, they cannot by themselves form a sentence, and their scope ranges over the entire sentence. Besides being identifiable on formal grounds alone, they are also clearly felt to be in some way semantically and pragmatically homogeneous (an intuition which is already reflected in the term modal particle or the more traditional German term Abtönungspartikel), although their semantics and pragmatics seem to be particularly elusive and difficult to grasp.

These morphosyntactic descriptions and the observation that the meaning of such forms is “particularly elusive and difficult to grasp” apply to most of these particles in Correntino Spanish as well. The source forms for many of such loans are epistemic particles in Guarani, and in many cases the resulting loans have semantically drifted from the original Guarani form12 and have come to acquire multifunctionality (Wiltschko et al. 2018), i.e., differing pragmatic interpretations depending on the discourse context. For example, the interpretation of angaú, which can mean “fake” or “supposedly” (see Table 2), depends on the pragmatic context, e.g., Es de buena marca angaú could be variably translated as “It’s supposed to be a good brand (and may be)” or “It’s supposedly a good brand (but absolutely isn’t)”.

The glosses of the resulting Spanish forms in Table 2 are given in the most general terms possible and are based on my familiarity with these forms in spoken Correntino Spanish in conjunction with descriptions provided to me by native speakers. There are notably various particles listed as “intensifier morphemes” (most of which come from Guarani epistemic particles) and “interrogative morphemes”, but this should not be interpreted as though the forms within these classes are interchangeable, as the syntactic properties of the loans are not identical, and they are no doubt differentiated semantically in subtle ways which have not yet been described.13 Interestingly, far more is known about the semantics of the source forms in Argentine Guarani (see Cerno 2013) than the resulting Correntino Spanish loanwords. The descriptions given here in Table 2 are a loose guide to the interpretation of these particles and not intended to be a satisfactory account of their semantics.

With regard to the presentation of memes here, each meme is accompanied by a line-for-line English translation found immediately below the meme. The translations here, all my own, prioritize functional equivalence over formal equivalence and accordingly aim to render the content in an idiomatic way. The nature of many of the grammatical loans makes their translation into English a challenging task, as there is rarely a one-to-one lexical correspondence between a given form and an English equivalent. As such, their rendering in English can vary from context to context. Subcaptions below each individual meme indicate the Guarani loans found within it; grammatical loans can be cross-referenced with Table 2.

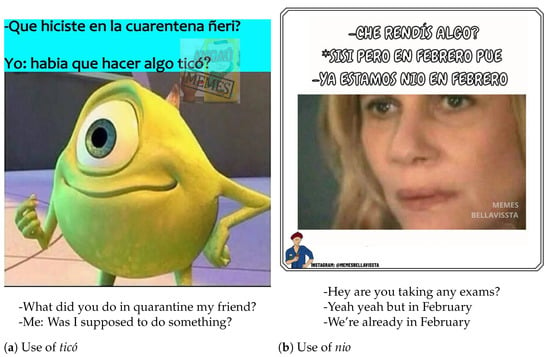

Methodologically, there is no distinction made here between the text in the image of the meme and the caption immediately below the meme, and thus loans in the meme itself were counted in addition to loans in the meme caption. This is due to the fact that meme captions are often as important as the content of the meme itself, representing an integral, sometimes crucial source of the humor of the overall entity. (Some memes, in fact, are uninterpretable when isolated from their caption). Meme captions are common sites for the meme creator to write using their own voice, adding commentary or a response to the content of the meme, often in the first person. Two examples of memes in which the loan is found within the caption are found in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Examples of memes in which the loan is found in the image caption as opposed to the meme itself.14

3.2. Theoretical Approach

My theoretical approach to the analysis of the meme corpus is rooted in grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss 1967; Strauss and Corbin 1990). I center my approach on the discussion of grounded-theory text analyses given by Bernard (2006, p. 492–97), which focuses on how to thematically synthesize a given text, grounding the resulting thematic generalizations in careful evaluation of the data. Memes by their very nature lend themselves well to such an approach, given their relative thematic simplicity compared to much lengthier texts such as interview transcriptions. The overall goal here is to identify the commonly recurring themes in the memes in which Argentine Guarani loanwords appear in order to reveal relationships between the use of these loans and particular social themes, in turn offering insight into the social value of these highly visible contact features.

To investigate this connection between Guarani loans and social meaning, each meme in the corpus was coded according to whether or not the content was in some way Correntino-specific. Ten criteria were used to justify counting a meme as “Correntino-specific”. Memes were evaluated on whether they contained the following:

- Overt reference to Corrientes, for any reason at all;

- Reference to food or drink typical of the province (e.g., mate, torta parrilla, torta frita, guiso, asado, etc.);

- Reference to flora, fauna, or ecological characteristics typical of the province (e.g., capybaras, caimans, yellow anacondas, the wetlands, etc.);

- Reference to local cultural customs involving song or dance (e.g., chamamé);

- Reference to rural life in the countryside (e.g., agriculture, horses, the summer heat, drought, mosquitoes, etc.);

- Reference to the provincial rivalry between Corrientes and Chaco;

- Reference to the perceived status of Corrientes as less developed than other Argentine provinces;

- Reference to Correntino politics;

- Reference to the local stereotype of Correntino machismo, generally conceived17 (e.g., that Correntino men have various romantic partners behind the back of their wife or girlfriend, that Correntino men are known for making advances on the female partners of their own close male friends, etc. Memes concerning romantic relationships in a general sense did not meet this criterion).

All memes in the corpus that did not meet these thematic criteria were counted as general, i.e., not Correntino-specific. Thematic patterns were common among this category of memes as well, with many of them having content that referred to schoolwork, Argentine culture broadly conceived (commonly about Argentine national politics), the COVID-19 pandemic, and general current events. Two examples of memes that fall into this general category are given in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Memes whose content is not Correntino-specific but still contain Guarani loans.18

4. Analysis

The memes that constitute the corpus discussed here are thematically often concerned with local issues of Correntino culture and current events. These memes serve as a niche for local content, as larger, more popular meme pages exist that focus on Argentina or Latin America more broadly. The role of these Correntino pages is therefore to replicate the patterns employed by meme creators in general, but in such a way as to provide localized content which is specifically aimed at Correntinos. Accordingly, and crucially, these memes consistently employ Correntino Spanish. There is no Guarani codeswitching in these memes, as their intended audience is unquestionably largely monolingual. All loans found in these memes, be they grammatical or lexical, are perfectly comprehensible by monolingual speakers of Correntino Spanish (but would not be comprehensible by speakers in, for example, Buenos Aires). The most common location for the production of these memes, as previously shown in Table 1, is Corrientes City, which is a virtually entirely monolingual space. As seen in Figure 2, even the memes that come from outside the provincial capital all come from population centers on the geographic periphery of the province, i.e., regions where Guarani has limited presence (Cerno 2013; Pinta 2022).

In Corrientes as elsewhere, internet culture is seen as aligned with modernity, technology, and urban lifestyles, and the content of the memes directly reflects this. Argentine Guarani is often portrayed as being in conflict with such things, being largely associated with tradition, agriculture, and rural lifestyles (Pinta 2022), a depiction of indigenous languages which is found throughout Latin America (Canessa 2012; French 2000). While there is a growing kind of cultural nostalgia in urban areas such as Corrientes City for things associated with the campo (‘countryside’) as being emblematic of the province in general, and while such topics do surface in the memes produced there, the use of Argentine Guarani in an overt way, even in a codeswitching context, is simply not an available linguistic resource for the younger, monolingual speakers of Correntino Spanish who are producing and consuming these memes.19

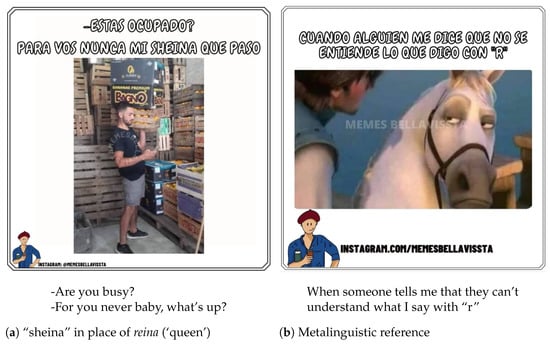

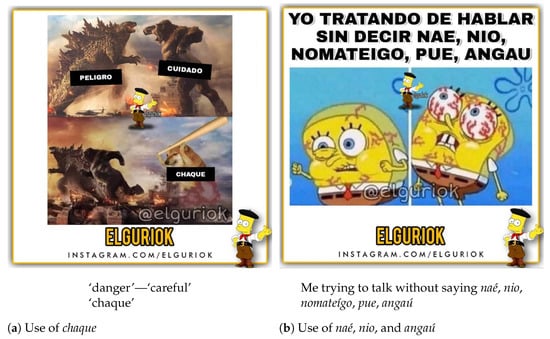

Given their locally focused nature, the memes make frequent use, occasionally in metalinguistic ways, of typically Correntino phonological, morphosyntactic, and lexical features. Prior to getting to the heart of the analysis here—lexical features, i.e., Guarani loans—it is worth looking at a phonological feature typical of Correntino Spanish that appears in Correntino memes: the use of the locally emblematic assibilated rhotic. While the majority of the features which delineate Correntino Spanish as a unique variety are Guarani in origin, a few are shared by other varieties of Latin American Spanish outside situations of Guarani contact, and this rhotic phenomenon is an example of this latter group. (It is, of course, interpreted in Corrientes as a salient phonological marker of local Spanish nonetheless.) Consideration of this feature is valuable as a prelude to the discussion of Guarani loans, as it serves as an excellent example of the ways in which local features are recruited in memes; the assibilated rhotic is found in metalinguistic contexts, affectionate contexts, and contexts of self-deprecating humor, and this thematic variety mirrors similar patterns which will be explored below in memes containing Guarani loans.

Correntino Spanish, like nearly all Spanish dialects, has two rhotic phonemes; in careful speech or formal contexts these are identical to the standard Spanish rhotics: the tap /R/ and the trill /r/. However, in informal contexts in Correntino Spanish, the trill is assibiliated, leading to a realization closer to [ʐ] or [Z]. (Similar realizations in other parts of the Spanish-speaking world, notably in the Andes, are often represented as [r̝].) This is represented orthographically by Correntinos, wishing to emphasize local pronunciation in written form, with sh. This written form is commonly employed in memes, often in ironic or humorous ways, and examples are seen in Figure 7 and Figure 8.20

Figure 7.

Examples of assibiliated rhotics being represented orthographically as sh in a romantic pet name (a) and referenced metalinguistically (b) in Correntino Spanish memes.21

Figure 8.

Examples of assibiliated rhotics being represented orthographically as sh in contexts of self-deprecating humor in Correntino Spanish memes.22

It is useful here to contrast the meme in Figure 7a with those in Figure 8. In Figure 7a, we see a man at work, obviously busy, responding to a text message from an individual we are to assume is his girlfriend. She asks if he is busy, and he replies that he is never too busy for her. Here we see the assibilated rhotic in the pet name reina ‘queen,’ written as sheina; this use is less a direct link to an aspect of Correntino culture and more a feature of the affectionate pet name being used. In speaking to a romantic partner, an informal register is assumed, and the use of the assibilated rhotic is perfectly appropriate in such a context. In the memes in Figure 8, we do not see quotations as in Figure 7a, but rather these memes are meant to directly communicate with the reader. In Figure 8a, we see what look like military boots but are actually “Croc Martens”, i.e., boots made to resemble leather Doc Martens brand boots that are in reality Crocs, the brand known for making inexpensive clogs made from a material similar to plastic or rubber. In Figure 8b, we see an image of someone ringing an electric doorbell with a video camera which is juxtaposed with a barking dog; the source of humor is the notion that “in other houses” doorbells are modern while in “Coshientes” the doorbell is a barking dog.

Thus, in Figure 7a, we see the assibilated rhotic as representative of an affectionate or intimate way of speaking, while in Figure 8a,b it is used to humorously portray Corrientes in a self-deprecating way. Although the writing of Corrientes as Coshientes can also take place in affectionate contexts which evoke local pride, the examples in Figure 8 illustrate the more common self-deprecating contexts, which humorously address what are perceived as societal or cultural shortcomings of the province. The latter contexts are far more common in the corpus than the former, and the humor in these cases is found in indirect references to the perception that Corrientes are less advanced or less modern than other regions of Argentina. Such humor is, in my experience, extremely common among locals in Corrientes. Jokes made by them about them are common, but crucially such jokes are only considered appropriate if made by locals. A joke about Corrientes made by an Argentine from another province would nearly certainly be seen as insulting in Corrientes. This is bound up with the use of the assibilated rhotic as a phonological feature that is emblematic of the province—only a Correntino could be saying en Coshientes in these examples. Use of this feature combined with the larger context of these memes as clearly coming from Correntino meme pages clearly communicates this as self-aware and self-deprecating—and therefore humorous as opposed to insulting.

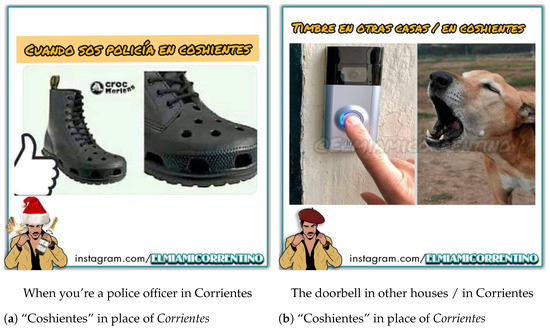

Returning to the corpus under discussion here, we frequently see the same kind of humorous connections between “Correntinoness” and linguistic features at play but via lexical items in lieu of phonological features. To take the most obvious class of examples, various memes make metalinguistic reference to Guarani loans, and examples of this are provided in Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Figure 9.

Memes making metalinguistic reference to Guarani loans.23

Figure 10.

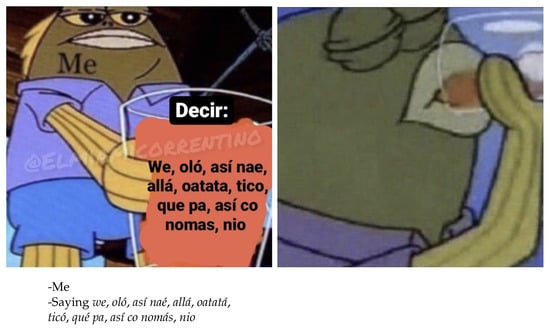

A two-part meme metalinguistically referencing various Guarani loans, i.e., naé, oatatá, ticó, pa, co, and nio.26

In Figure 9a, we see the Guarani loan chaque, meaning ‘[be] careful’ or ‘look out,’ being used in a meme which takes imagery from an advertisement for the 2021 film Godzilla vs. Kong. The standard Spanish forms peligro ‘danger’ and cuidado ‘[be] careful’ are seen fighting, overlaid on images of Godzilla and King Kong, only to be chased away by chaque with a baseball bat, which is overlaid on an image of a dog (which is itself a reproduction of the popular “Cheems” meme, in turn an iteration of the “Doge” meme). The implication of this meme—that chaque is the superior of the three terms, as the others are seen fleeing from it while it chases them away with a baseball bat—is relatively straight-forward.

In Figure 9b and Figure 10, we see variations of a recurring theme in the corpus: that of Correntinos being unable to avoid using Guarani loans, in particular the more frequent grammatical loans. In Figure 9b, we see the cartoon character SpongeBob SquarePants in two stages of increasing physical discomfort. The caption “Me trying to talk without saying naé, nio, nomateígo,24 pue,25 angaú”, when linked with this visual, communicates the idea that to attempt to speak without using these words is a source of visceral discomfort.

Similarly, in the two-part meme in Figure 10 we see a cartoon character (also from SpongeBob SquarePants) holding a drink, the contents of which are shown to be a series of emblematically Correntino words and expressions, most of them loans from Guarani. The second part of the meme shows the character finishing the drink in one motion. Notably, there is agency in this meme that is not clear in Figure 9b; these lexical forms are deliberately “ingested” in this case, presented as something the speaker is not resisting but rather desires.

The memes in Figure 9 and Figure 10 demonstrate Correntinos’ awareness of a host of lexical items that characterize Correntino Spanish. While some of the forms of non-Guarani origin are not unique to Correntino Spanish (e.g., pue, we27), the borrowed forms are in general not found in the Spanish of other Argentine provinces,28 which allows for their recruitment in metalinguistic ways.

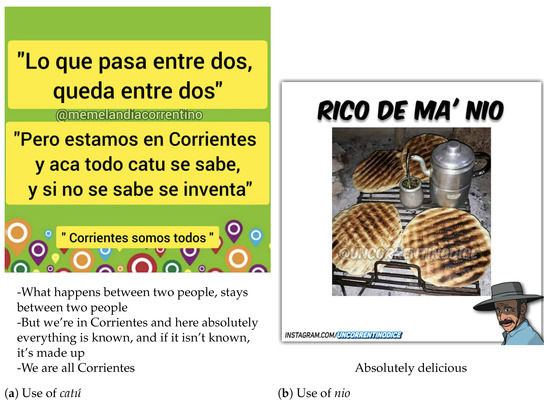

While the metalinguistic use of Guarani loans is telling, the vast majority of the memes that make use of such loans do not do so metalinguistically. Nonetheless, throughout the corpus Guarani loans appear in memes whose content is explicitly or implicitly Correntino in nature. Examples are provided in Figure 11 and Figure 12.

Figure 11.

Memes whose content is Correntino-specific and contains Guarani loans.30

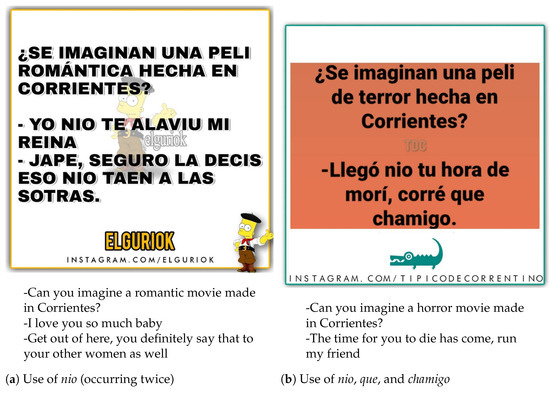

Figure 12.

Memes whose content is Correntino-specific and contains Guarani loans. In these cases, both make reference to what a Correntino-made movie of a particular genre would be like.31

In Figure 11a, we see reference to a common local cultural trope of Corrientes being a place where gossip is common and spreads quickly. The use of catú here plays the double role of grammatically underscoring the fact that “everything is known” and authenticating the phrase as Correntino, grounding it in a commonly shared cultural notion. This is further emphasized by the aesthetic nature of the meme, which is made to resemble the aesthetic used by the provincial government in tourism campaigns and public service announcements. The last of the three phrases—Corrientes somos todos ‘We are all Corrientes’—is the slogan used by the provincial government in such contexts, and the ironic use here adds a further layer of humor coming as it does after the point that everyone knows everything about one another in Corrientes.

In Figure 11b, we see a scene both common and beloved throughout the province, that of torta parrilla (a large piece of bread cooked on a grill) and yerba mate, being described via a classically Correntino linguistic construction. De ma, a reduced form of de más (often written demá), is a common intensifier in both Correntino Spanish and Argentine Guarani.29 This used alongside the Guarani-origin intensifier nio, together describing rico ‘delicious,’ yields an English translation along the lines of “absolutely delicious”. The recruitment of localized linguistic features to describe a localized culinary custom as delicious underscores both as emblematic of the province.

The memes in Figure 12 are versions of the common theme in Correntino memes of imagining what an authentically Correntino version of a given media genre would look like—in this case, what a horror movie and a romantic movie made in Corrientes would be like. Figure 12a is rich in Correntino phonological, morphosyntactic, and lexical features; the Guarani loan nio appears twice, and phonological features common to Correntino Spanish are represented orthographically (i.e., reductions such as taén from también ‘also,’ jape from rajá pue(s) ‘get out of here’). The “loan” alaviu is a Hispanicized rendition of the English phrase I love you,32 clearly used here as symbolic of Hollywood romantic movies. The humor is found in imagining the use of such emblematically Correntino features in a movie, and these features complement the non-linguistic Correntino content of the meme as well—the local stereotype of Correntino men as smooth talkers who have more than one romantic partner. The recruitment of Guarani-origin features for similar purposes is visible in Figure 12b as well. The loans nio and que (from the Guarani morpheme ke, used to strengthen imperatives) complement the deleted coda r in morir, written as morí,33 and the ubiquitous chamigo (‘my friend,’ a combination of the Guarani possessive che ‘my’ and Spanish amigo ‘friend’).

As evidenced in Figure 12, a variety of linguistic resources can be utilized to ground a meme as authentically Correntino, and the corpus is full of such occurrences. While there exist various linguistic features seen as emblematic of Correntino Spanish that are not Guarani in origin (e.g., pue, we, demá, etc.),34 they constitute exceptions, if important ones, to the generalization that Guarani-origin features are the defining characteristics of Correntino Spanish as a distinct variety not only within Argentina as a whole but within the Argentine northeast more narrowly. Memes whose purpose is to evoke Correntino ways of speaking, whether metalinguistically or not, inevitably rely heavily on Guarani-origin linguistic material to achieve this end.

Returning to the categorization criteria provided in Section 3.2, 241 of the 409 memes (58.9%) contain Correntino-specific content, while 168 (41.1%) contain general content. Of the 168 memes without reference to Correntino cultural phenomena, many of them still concern everyday aspects of Correntino life but not aspects unique to Corrientes. For example, many of the memes reference the devaluation of the Argentine peso.35 This devaluation has had a profound impact on the less economically prosperous provinces of Argentina, with Corrientes being one of the most affected. While this economic reality is in many ways a central characteristic of Correntino life at present, memes addressing such a reality are being made throughout the country, meaning such memes in the corpus cannot be considered specific to Corrientes. Despite these and similar memes being classified as general, the corpus still contains more Correntino-specific content than not, a pattern that is indicative of a link between Guarani loans and Correntino culture generally.

5. Argentine Guarani Loans as Enregistered Features

Argentine Guarani loans, representing the core of a constellation of linguistic features which constitute and demarcate Correntino Spanish as a unique Spanish variety, have come to acquire a variety of indexical values, some in conflict and paradoxical, mirroring the cases of Cosmopolitan Mandarin (Zhang 2021) and American English-ing (Campbell-Kibler 2007), as discussed in Section 2.1. The simultaneous indexing of positive and negative values associated with Corrientes and Correntinos evidences the complexity and malleability of the social meaning of these forms, which varies via context and can change over time.

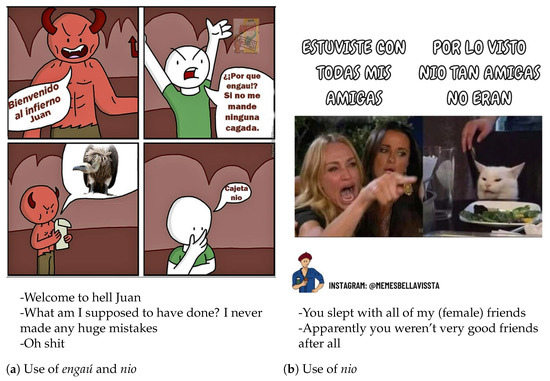

As described by Johnstone et al. (2006, p. 83) in their discussion of the enregisterment of particular features of Pittsburgh English, the conditions have formed in which Correntinos can “use regional forms drawn from highly codified lists to perform local identity, often in ironic, semiserious ways”, and we can account for this by returning to the previously discussed notion of character type. The varied social meanings of Guarani loans are used to evoke various Correntino character types that serve to amplify these meanings and make them increasingly visible. The stereotype of the smooth-talking, womanizing Correntino man is one such character type. Memes that draw on this stereotype are seen in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Memes illustrating the character type of the womanizing Correntino man.36

In Figure 13a, we see a man being welcomed to hell by the devil. When the man asks why he is in hell, the devil looks at a picture of a vulture. The vulture here is symbolic in the same way as the chajá mentioned earlier; i.e., buitre ‘vulture’ is a common designation for a man who seduces the girlfriend or wife of another man. Upon realizing that is why he is there, the man no longer protests, accepting both his guilt and that that is a legitimate reason for his punishment. In Figure 13b, we see a local version of the common woman-yelling-at-a-cat meme in which a woman accuses someone of having slept with all of her friends. The accused here, a cat who is understood to stand in for her male boyfriend or love interest, responds not by defending himself but rather by saying they must not have been very good friends after all. In choosing to not deny the accusation, the implication of his guilt is clear. These memes both provide a window into a common characteristic of the womanizing Correntino character type, that of a lack of sympathy or sense of guilt, of an almost brazen disregard for the consequences of his actions. The use of the Guarani loans engaú37 and nio authenticate this meme as linguistically Correntino and align it with the local stereotype of the buitre/chajá.

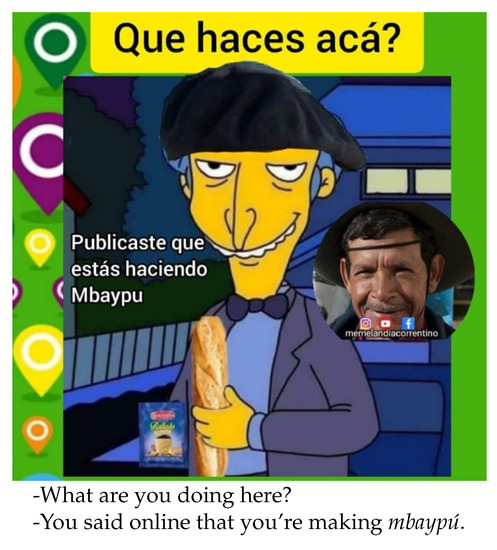

The womanizer character type directly contrasts with another common character type, that of the morally upright, hardworking Correntino gaucho. In fact, this character type is so common that the watermark of the meme page Memelandia Correntino, i.e., the symbol used on many of the memes to prevent others from passing them off as their own, is a gaucho whose name is given as Don Vicente. Occasionally, serious posts of Don Vicente are made, such as each April 30th, the local “day of the rural worker”, which celebrates those Correntinos who work in various agricultural capacities throughout the province. Although the watermark is usually made semi-transparent, in one meme in the corpus, seen in Figure 14, we can see it clearly, adjacent to the main content to which it is thematically unrelated.

Figure 14.

A meme illustrating the water mark of the meme page Memelandia Correntino. The loan mbaypú occurs, from the Guarani source form mbaipy, a common local dish similar to polenta that is traditionally made from corn flour.38

The character type of the hardworking Correntino gaucho takes various shapes in Correntino memes, but the uniting traits are honesty, service to the community, and a commitment to hard work. Two memes, different in aim but both drawing on this character type, are given in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Memes illustrating the character type of the hardworking Correntino gaucho.39

In Figure 15a we see a man dressed in prototypically rural attire who, wearing a mask out of respect for local anti-COVID measures, is at a local voting center on voting day. The simple description “excellent Correntino” is a relatively rare instance of a “meme” without irony or humor of any kind. It is meant as a self-serious homage to the idealized Correntino gaucho, a classically attired, upright community member doing his civic duty. In Figure 15b we see a different representation of the same character type, involving humor more reminiscent of the other memes in the corpus. A presumed sex worker is speaking to a man through his car window, offering any service for 1000 pesos. He responds happily, saying that he is in need of a farmhand to help him herd cattle. In addition to the obvious irony, this meme is understood to be reflective of the idealized Correntino gaucho, whose loyalty to his work and moral fortitude are his highest priority. In both memes in Figure 15, we again see the use of Guarani loans (and de ma in the case of Figure 15b) as sociolinguistically grounding them in a local way, offering an additional layer of social meaning beyond what would be found in a generalized meme whose target audience was all of Argentina or Latin America generally.

As evidenced by the linguistic and thematic patterns in Correntino memes, Guarani loanwords in Correntino Spanish have come to acquire social meaning that allows for uses that cannot be solely accounted for by their semantics. They have undergone enregisterment, the result of which has afforded them locally specific cultural value. Just as a collection of features of Pittsburgh English, as discussed by Johnstone et al. (2006), underwent enregisterment processes that took them through the indicator →marker→ stereotype evolutionary pathway, the same processes have resulted in the accrual of social meaning in Guarani loans in Correntino Spanish to the point of allowing their recruitment for use in local stereotypes, as evidenced by the character types visible in Correntino memes.

Correntino Spanish features are simultaneously associated with the romanticized ideal of the Correntino gaucho as well as the Correntino womanizer. The use of Guarani loans in the representation of such character types goes well beyond demarcating Correntino Spanish as a mere geographic variety; Podesva (2011, p. 9) notes that character types crucially “index much more than simply the regions from which such characters originate. They additionally index cultural values”. The malleable indexical values of the features used to evoke Correntino character types in turn create differing character types themselves, which are part of the process of production and reproduction of such cultural values. As Eckert (2008, p. 464) notes, “[t]he use of a variable is not simply an invocation of a pre-existing indexical value but an indexical claim which may either invoke a pre-existing value or stake a claim to a new value”. Such properties, whether at the level of a particular feature, the constellation of features, or the character types such features are linked to, allow for rapid evolution of social meaning, something which memes as a genre are in a perfect position to respond to and even assist in.

The agency of individuals in the process of interpreting and reproducing the social meaning of a set of forms was something commented on by Agha (2003, p. 242) in his pioneering work on enregisterment, in which he notes,

[I]t is not my purpose to assert that public sphere representations (such as the ‘mass media’ depictions discussed earlier) determine individual views, or anything of the sort. Contemporary mass media depictions are themselves the products of individuals caught up in larger historical processes; and the ‘uptake’ of such messages by audiences involve processes of evaluative response that permit many degrees of freedom. I am concerned rather with the ways in which these representations expand the social domain of individuals acquainted with register stereotypes, and allow individuals, once aware of them, to respond to their characterological value in various ways, aligning their own self-images with them in some cases, transforming them in others through their own metasemiotic work.

Memes function as a “public sphere representation” par excellence in that they are easily accessible, easily transformed according to an individual meme creator’s intention, and rapidly disseminable in a modified version. Correntino memes, with a host of linguistic features available to ground them as Correntino, are free to be used to index a complex variety of shifting social values and to portray an evolving set of character types. In fact, within the broader world of memes, originality via modification is in essence the defining characteristic of a good meme. The Correntino memes that do the best, i.e., which garner the greatest number of likes and comments, are commonly not memes created out of thin air but are rather locally tailored instantiations of meme templates, trending throughout the internet at large or more narrowly throughout Latin American or Argentine corners of it, which are then cleverly modified to make them Correntino. In this way, memes as a genre encourage a kind of quickened evolution of the form and meaning of the memes themselves, which in turn creates optimal conditions for subtle shifting of the accrued social meaning of the linguistic features that they employ.

The use of Guarani loans in Correntino memes in the service of reproducing stereotypes demonstrates that they are above the level of social awareness, and they are accordingly available for explicit social commentary. An illustrative example is found in Figure 12a, the meme that imagines what a romantic movie made in Corrientes would be like, with the proposed conversation between two characters reproduced here:

-Yo nio te alaviu mi reina ‘I love you so much baby’

-Jape, seguro la decís eso nio taén a las sotras ‘Get out of here, you definitely say that to your other women as well’

The double use of nio—the most common of the grammatical loans in the corpus (see Figure 4)—is a central part of the amalgamation of Correntino features here. These features are part of a complicated network of meanings and stances that allow the meme to work; they are predicated on the reader’s understanding of, at minimum: (1) the character type of the Correntino womanizer, (2) the lack of movies in which Correntino Spanish is heard (and by consequence the perception of a serious movie in Correntino Spanish as ironic), (3) the status of English as a common language of romantic films, and (4) the social value held by the linguistic features found in this conversation. This meme simply would not work in standard Spanish—its comedic value is entirely dependent on an irony that is only possible given the social value of the linguistic features used here. Only enregistered features are available for such work. Only features which have come to acquire locally grounded social meaning can be used effectively given that, in the case of memes, other non-linguistic characteristics which might be available to do such work in an embodied interaction (e.g., posture, gesture, clothes, etc.) are unavailable. The task of communicating “Correntinoness” here falls exclusively on linguistic features.

I echo Babel (2011, p. 56) in noting that “the theory of enregisterment provides a useful tool for interpreting the effects of language contact”, given that, as in the case of Argentine Guarani loanwords in Correntino Spanish, language contact is an engine of language variation, and language variation and social meaning are inextricable, as third-wave (and, indeed, first- and second-wave) sociolinguistic research has carefully demonstrated. Correntino Spanish, as a subvariety of a macrovariety often labeled “Argentine Spanish”, shares a wealth of linguistic features with Spanish speakers of other Argentine provinces such as Buenos Aires, Córdoba, Santiago del Estero, and so on. However, the array of Guarani contact features found in Correntino Spanish are visibly absent in these other closely related Argentine varieties, which allows for their recruitment as local, Correntino emblems. Notably, this can occur whether or not speakers are aware of their status as contact effects in the diachronic sense—that they are recognized as Correntino is all that is necessary for them to become enregistered in this way. The close contact Correntino Spanish has had with Argentine Guarani has endowed it with a particularly rich and diverse set of features which, although not the only enregistered features in Correntino Spanish, make an excellent case study for the targeting of contact-induced variation by the process of enregisterment.

6. Conclusions

This article has aimed to illuminate a previously unanalyzed aspect of the complex situation of language contact in the Argentine province of Corrientes: the social value of Argentine Guarani loanwords in Correntino Spanish. Via analysis of a unique corpus of internet memes, Guarani loans in Correntino Spanish are shown to have undergone enregisterment; i.e., they have become used and understood by speakers in ways that link them to a web of Correntino cultural characteristics and “Correntinoness” generally. Linguistic emblems of “Correntinoness” are simultaneously used to portray Correntino pride and in comedic self-deprecation; they are used to evoke positive and negative Correntino character types. Such differing values are contextually dependent, with the “hearer” (or in the case of memes, the reader) playing an active role in their emergence. These values are linked to larger social space; as Eckert (2008, p. 455) notes, “we construct a social landscape through the segmentation of the social terrain, and we construct a linguistic landscape through a segmentation of the linguistic practices in that terrain”. The Correntino linguistic landscape, being in many ways defined by contact features, provides speakers with a varied set of unique features with which to make connections to larger social phenomena.

Analysis of the enregisterment of such contact features not only allows for deeper understanding of the language contact situation in Corrientes generally, but also supports the notion, advanced by Babel (2011), that the theory of enregisterment provides a nuanced approach to situations of intense language contact—situations in which a complete account of language mixture requires not only an understanding of the linguistic mechanisms involved but also an understanding of the social value of the resulting contact features and the ways in which speakers exploit such value. By drawing on a complicated indexical field, whose social values are rooted in ideologies surrounding complex and paradoxical elements of Correntino identity, speakers deploy Guarani-origin contact features to achieve social ends, something only possible via the process of enregisterment. The ways in which such social ends are achieved are visible in Correntino internet memes, which are grounded in local perceptions, values, and stereotypes. The continued popularity of memes in Corrientes and the use of regionally grounded forms within those memes will no doubt both reflect and foster continued evolution of the social value of Guarani loans in Correntino Spanish.

While the use of internet memes as a primary object of analysis is not without limitations—internet memes, after all, are not naturalistic speech—the kinds of linguistic resources which meme creators employ in the act of creation/modification must necessarily be authentic for a meme to have the desired effect, particularly as it pertains to locally specific humor or irony. This article thus provides a further example of memes as windows into the kinds of sociolinguistic phenomena that can further our understanding of how linguistic features—in this case, contact features—become meaningful social objects.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge those who provided valuable feedback on the initial form of this article, as a chapter of my doctoral dissertation: Anna Babel, Don Winford, Cynthia Clopper, Holly Nibert, and Scott Schwenter, in addition to those whose suggestions and feedback greatly enriched this much improved version: Whitney Chappell, Sonia Barnes, Leonardo Cerno, and two anonymous reviewers. I am also indebted to those whose expertise in Correntino Spanish was a crucial source of assistance in the interpretation of many of the linguistic constructions in the memes informing this study; this article would not have been possible without the assistance (and patience) of Leonardo Cerno, Valeria Centurión, Daiana Barrios, Diego Ojeda, and Nicol Fariña.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The most common designation for this variety of Guarani is the Spanish term guaraní correntino. In English, I opt for use of the term “Argentine Guarani” (as opposed to “Correntino Guarani” or “Correntinean Guarani”) for reasons outlined in (Pinta 2022, pp. 6–10). |

| 2 | Throughout this article I will use the unspecified term “Guarani” as synonymous and interchangeable with the more precise “Argentine Guarani”, the variety that is in contact with Correntino Spanish. Argentine Guarani is treated by most scholars as a mere geographical extension of Paraguayan Guarani into Argentina—and therefore “Paraguayan Guarani” is commonly described as being spoken in Corrientes—despite the historical and linguistic differences between them that hinder mutual intelligibility and the societal differences that have produced vastly different sociolinguistic realities for speakers of the two varieties (Pinta 2022). It is, of course, perfectly acceptable to talk about the influence of “Guarani” on “Spanish” in the context of northern Argentina and Paraguay as a general region, abstracting over dialectal differences; however, the source of the Guarani loans in the Spanish spoken in Corrientes is, in some cases, demonstrably Argentine Guarani and not Paraguayan Guarani. Accordingly, all references to “Guarani” here are to be read as implying “Argentine Guarani”, and in cases where ambiguity is possible or precision is necessary then appropriately precise terms will be used. |

| 3 | For further discussion of the relationship between these two approaches, see (Eckert 2008, pp. 463–564). |

| 4 | Some scholars prefer a more fine-grained distinction between these and related categories, e.g., see (Moore and Podesva 2009). |

| 5 | For a detailed treatment of the history of the term and concept, see (Wiggins 2019, pp. 1–20). |

| 6 | Source: Memelandia Correntino, https://www.instagram.com/p/CZnjEPuFQar (accessed on 14 June 2023). |

| 7 | In fact, some of the memes in the corpus informing this article might fall outside a narrow definition of what a meme is, given that images are often seen as necessary components of memes in the prototypical sense, and some memes in the corpus are text unaccompanied by imagery. |

| 8 | Handles provide the web address of each individual page; by replacing the “X” in https://www.instagram.com/X with a given handle (minus the @) the address can be recovered, e.g., https://www.instagram.com/elmiamicorrentino (accessed on 14 June 2023). All pages are live as of 14 June 2023 with the exception of Memes Bella Vissta, which has been removed from Instagram for unknown reasons. |

| 9 | The map in Figure 2 was taken from Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:San_Miguel_(Provincia_de_Corrientes_-_Argentina).svg, accessed on 14 June 2023). It is reproduced here under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license and has been altered for the purposes of this article. |

| 10 | Exceptions to this include some memes which either directly reference Correntino culture in meaningful ways or memes which make metalinguistic reference to Correntino Spanish phonological features. These additional memes do not figure into the 409-meme corpus referenced here (unless they also happen to contain a loan), but some of them will be referenced below. |

| 11 | For a list of the properties of modal particles that justify them as a specific class, see (Abraham 1991, pp. 4–5). |

| 12 | See (Schwenter and Waltereit 2010) for discussion of this kind of historical change in additive particles. |

| 13 | See (Marco and Arguedas 2021) for discussion of intensification and the complexity of defining it. |

| 14 | Source (a): Típico de Correntino, https://www.instagram.com/p/CF2GiLEnrIi (accessed on 14 June 2023). Source (b): Angaú Memes, https://www.instagram.com/p/CCqWrU9HVokma6pAzyLpNmS7hb-5zrOTrzdC8c0 (accessed on 14 June 2023; this source URL only works for Instagram users who are followers of this page). |

| 15 | Itself a loan whose source is the Guarani form paje, it is described as local charm or magic, in both positive and negative contexts. |

| 16 | A mythological figure of Guarani origin who is said to live in rural regions. Alternatively described in positive and negative lights, e.g., as a protector of local wildlife or as a troublemaker, belief in the pombero is common among the rural inhabitants of the province, who both fear and respect him. During fieldwork in the rural interior of the province in 2017 and 2018, various locals recounted to me stories of having seen the pombero, and one individual very earnestly warned me of him. |

| 17 | While it could be argued that this kind of generalized machismo is not locally specific to Corrientes (and is perceived as common throughout Argentina, or Latin America in general), this category deserves inclusion here due to a variety of Correntino-specific lexical items which are used to describe such phenomena in a locally specific way. Many of these terms are Guarani in origin, e.g., chajá, from Guarani chahã, the name for the Southern screamer (Chauna torquata), a common bird species native to the province, which in turn came to be used for a man who seduces the wife or girlfriend of another man. |

| 18 | Source (a): Angaú Memes, https://www.instagram.com/p/CCXaY8FDEXmt07l36LPhwN3k25rnBdgoMYhqNE0 (accessed on 14 June 2023; this source URL only works for Instagram users who are followers of this page). The source page of the meme in (b), Memes Bella Vista, has been removed from Instagram, and accordingly the source URL is no longer available. |

| 19 | To clarify further, “the use of Argentine Guarani in an overt way” refers to proficiency of some kind in the language itself and does not include the use of Guarani loanwords in Spanish. Just as the use of raccoon or persimmon by an English speaker speaking North American English does not imply knowledge of Powhatan, the use of the Guarani loans discussed in this article by a Spanish speaker speaking Correntino Spanish does not imply knowledge of Guarani. |

| 20 | It is worth mentioning that while these memes come from Instagram pages used as sources for the corpus (those from Figure 7 are from Memes Bella Vista, and those from Figure 8 are from El Miami Correntino), they are not part of the 409 memes that constitute the corpus given that they do not contain Guarani loans. |

| 21 | The source page of both memes in Figure 7, Memes Bella Vista, has been removed from Instagram, and accordingly the source URLs are no longer available. |

| 22 | Source (a): El Miami Correntino, https://www.instagram.com/p/CJiy0HwnuKS (accessed on 14 June 2023). Source (b): El Miami Correntino, https://www.instagram.com/p/CIbPSpAHKo2 (accessed on 14 June 2023). |

| 23 | Source (a): El Guriok, https://www.instagram.com/p/CLaxD1KH8J_ (accessed on 14 June 2023). Source (b): El Guriok, https://www.instagram.com/p/CMsgltSnxAa (accessed on 14 June 2023). |

| 24 | Nomás te digo ‘I’m just saying’ but written as it is frequently pronounced, including the deletion of various consonants, i.e., [no.ma.t̪e."i.Go] instead of [no.mas.t̪e."Di.Go] in careful speech. |

| 25 | The Correntino realization of the highly frequent form pues, a discourse marker often found phrase-finally in Correntino Spanish. |

| 26 | Source: El Miami Correntino, https://www.instagram.com/p/CLrpCZ_HnVe (accessed on 14 June 2023). |

| 27 | A common phrase-initial discourse marker. |

| 28 | It should be noted that some of these loans occur in Paraguayan Spanish as well. However, others—e.g., the interrogative marker ta (Cerno 2013, p. 227)—are specifically Argentine Guarani in origin (i.e., their source form is nonexistent in Paraguayan Guarani) and therefore are unique to Correntino Spanish. The fact that some Guarani loans are shared between Correntino Spanish and Paraguayan Spanish should not be interpreted to mean that these two varieties of Spanish are largely the same. Various features, in particular phonological but also morphosyntactic and lexical, demarcate Paraguayan Spanish and Correntino Spanish as being clearly and immediately recognizably distinct Spanish varieties (for discussion along these lines specifically regarding contact features, see (Estigarribia et al. 2023)). |

| 29 | The original etymological source of this form, while unclear, may be the Portuguese demais ‘much, too much,’ which patterns in many ways like the forms in Argentine Guarani and Correntino Spanish (Leonardo Cerno, personal communication, 8 December 2022). |

| 30 | Source (a): Memelandia Correntino, https://www.instagram.com/p/CavIyqKl3oM (accessed on 14 June 2023). Source (b): Un Correntino Dice, https://www.instagram.com/p/CM703fTswy0 (accessed on 14 June 2023). |

| 31 | Source (a): El Guriok, https://www.instagram.com/p/CKO-ZLqH1Do (accessed on 14 June 2023). Source (b): Típico de Correntino, https://www.instagram.com/p/CJCM6SXHZWg (accessed on 14 June 2023). |

| 32 | It is interestingly treated as just a verb here as opposed to a verb phrase, replacing the Spanish verb form but not the Spanish pronouns yo ‘I’ or te ‘you’. |