Abstract

This study describes the segmental and suprasegmental phonology of Adur Niesu, a Loloish (or Ngwi) language spoken mainly in Liangshan, Sichuan, southwest China. Phonemically, there are 41 consonants, 10 monophthongs and 1 diphthong in Adur Niesu. All Adur syllables are open. Its segmental changes mainly happen to the vowels, featuring high vowel fricativization, vowel lowering, vowel centralization, vowel assimilation and vowel fusion. It is common for Adur Niesu syllables to be reduced in continuous speech, with floating tones left. There are three main types of syllable reduction: complete reduction including the segment and tone, partial reduction with a floating tone left, and partial reduction with the initial consonant left. Adur Niesu employs tones as an important means for lexical contrast, namely, high-level tone 55, mid-level tone 33, and low-falling tone 21. There is also a sandhi tone 44. There are two types of tonal alternation: tone sandhi and tone change. Tone sandhi occurs at both word and phrasal levels, and is conditioned by the phonetic environment, while tone change occurs due to the morphosyntactic environment. Finally, some seeming tonal alternation is the result of a floating tone after syllable reduction.

1. Introduction

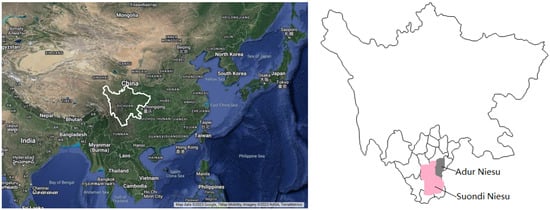

Adur Niesu is a member of the Nisoic (aka. Loloish or Ngwi) subgroup of the Niso–Burmese (i.e., Burmese–Lolo) language group of the Tibeto–Burman languages (Bradley 1997; Lama 2012). It is spoken by about 440,000 people, who are officially recognized as Yi (彝族), residing in mountainous regions in Liangshan (literally ‘Cool Mountains’), Sichuan, in southwest China. The Adur Niesu people often call themselves simply Adur, which is said to be the surname of a famous ruling clan living in Butuo (or ndʑi55la33pu44thɯ33) in eastern Liangshan. Adur is often associated with the title ndzɨ33mo21 (lord caste:master) ‘highest lord caste’ and its variant ndzɨ21mo21 (lord caste:big) ‘big (accomplished) highest lord caste’, namely, a33tu̠33ndzɨ33mo21 and ndzɨ21mo21a33tu̠33. It is noted that the tone on the morpheme meaning ‘lord caste’ is different when it is before and after Adur, namely, ndzɨ33 and ndzɨ21. This reflects a tone change that will be discussed in Section 4.4.3. When ndzɨ33mo21 is placed after Adur, without any tone change, it functions as a title, similar to the structure in su̠33ga55 ma55mo21 (surname teacher) ‘Mr. Suga’. When ndzɨ21mo21 is placed before Adur, with a tone change, it is a nominal modifier meaning ‘big (accomplished) lord caste’, similar to dza44ndo33vi33 su̠33ga55 (food:swallow:type surname) ‘Suga, big eater’. The Adur Niesu people mainly live in Butuo (布拖县), Puge (普格县) and Ningnan (宁南县), with some Adur population located along the border with Jinyang (金阳县) and Zhaojue (昭觉县); see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Adur Niesu.

Moreover, Adur people also call themselves Niesu [njɛ33 su33]. This autonym is shared by another group of Yi people adjacent to the Adur region, called Suondi Niesu or simply Suondi or Niesu; see Figure 1. Niesu [njɛ33 su33] has two meaning-bearing morphemes, namely, [njɛ33] ‘black’ and [su33] ‘people’, which literally means ‘black people’. The population of Suondi Niesu is around 550,000, estimated according to Chen et al. (1985); Gerner (2013) and the 2010 Population Census of Liangshan. Major Suondi-speaking regions are Dechang (德昌县), Huili (会理县), and Puge (普格县) within Liangshan, Miyi (米易县) in the adjacent city of Panzhihua (攀枝花市) in Sichuan, and Yongren (永仁县) and Yuanmou (元谋县) in Yunnan. Mutual intelligibility between Suondi Niesu and Adur Niesu is relatively high.

There are three recent studies about Niesu phonology, mostly focusing on Suondi Niesu in Mahai (2015, 2019) and in Mise (2020). Since Suondi Niesu is very close to Adur Niesu, these works are important references to understand Adur Niesu. But there is still room to improve the accuracy and adequacy of the analysis. Although some phonetic information, i.e., Adur consonants, vowels and tones, are presented in Sun’s (2020) construction of an Adur phonetics corpus, there is little research on the phonology. Therefore, this study will contribute to the literature by describing the phonological system of Adur Niesu. The Adur Niesu data presented in this paper are first-hand fieldwork data collected through spontaneous narration and elicitation, mainly based on the Tuojue dialect spoken in central Butuo, Liangshan. The fieldwork in Tuojue (or 拖觉镇), Butuo, started in 2018 and there have been five trips so far; each trip lasted for about two months. The two main consultants are Adur Niesu native speakers who are in their 30s. They started to learn Chinese after they were 10 years old in school and became fluent in Chinese around the age of 18. The data presented in the paper were also cross checked with elder speakers aged from 50 to 70 in Butuo, Liangshan. Although a series of studies have been devoted to the labiovelar sounds in Adur Niesu (i.e., kp, kph, gb, gb, ŋm) (Pan 2001; Matisoff 2006; Hajek 2006; Bradley 2008), such sounds are not found in the Tuojue dialect.1

2. About Adur Niesu

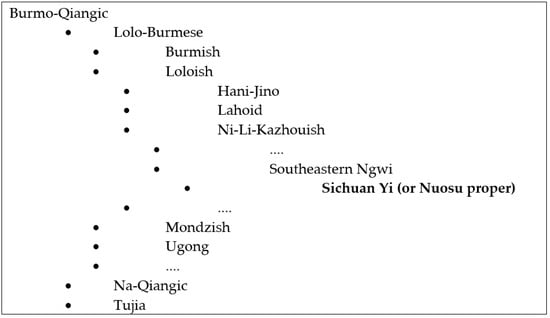

Based on the subgrouping in Hammarström et al. (2022), Adur Niesu is a verb–final syllable–tone Burmo–Qiangic language; see Figure 2 and Figure 3. Its morphology is largely isolating. A large number of phonemic consonants in Adur Niesu are generated by voicing, aspiration and prenasalization. The grammatical function of Adur Niesu is mainly conveyed by using clitics and postpositions. Property-denoting modifiers follow the head noun. However, noun and genitive modifiers precede the head noun. Tense is not a grammatical category in Adur Niesu. The relation of the event time to some temporal reference point is expressed by lexical means, such as a21ŋu33 ‘now’, a21ȵi55 ‘the past’ and i21sɛ21ʂɿ44a33ɬo44 ‘the ancient past’. Its aspectual classes are expressed strictly analytically, by verbal enclitics, TAM auxiliaries, and periphrastic constructions. Adur Niesu forms its yes/no questions by reduplicating the last syllable of the verb or auxiliary. It is topic-prominent, frequently employing topic–comment constructions.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic position of Nuosu proper.

Figure 3.

Internal subgroupings of Nuosu proper.

A close dialect of Adur Niesu is Nuosu. Nuosu, also meaning ‘black people’, is a relatively well-studied variety of Nuosu proper (Chen et al. 1985; Bradley 1990; Chen and Wu 1998; Lama 1998; Hu 2001, 2010; Gerner 2013). Both Niesu and Nuosu are classified under Nuosu proper (Lama 2012); see Figure 3. People using the autonym of Nuosu include Shynra, Yynuo, and Qumusu speakers, whose population is estimated to be about 1.9 million (Bradley 2001).

The mutual intelligibility between Adur Niesu and Nuosu is relatively low (Bradley 2001), which is mainly due to phonological differences (see Table 1, and also Pan 2001; Matisoff 2006; Hajek 2006; Lama 2012).

Table 1.

Exemplifying the phonological differences between Niesu and Nuosu.

While Adur shares many words with Suondi Niesu, it is phonologically different from Nuosu. If their geographic distribution is considered, Suondi Niesu is sandwiched between Adur Niesu and Nuosu. According to Lama (2022), there are two shared phonological innovations in Adur Niesu and Suondi Niesu, making them different from Nuosu. The first one is the lenition of the voiceless nasals, namely, making the voiceless nasals m̥ and n̥ voiced; see Table 2. The second innovation is that the *o sound in Proto-Nuosu proper is fronted and raised to i in Adur and Suondi Niesu; see Table 2.

Table 2.

Niesu phonological innovations (Lama 2022).

There are additional innovations to subgroup Adur Niesu and Suondi Niesu under one node, and support Lama’s (2022) claim that they should be the first group to branch off from Proto-Nuosu proper. For example, the Proto-Loloish (PL) stops in Table 3 change to affricates in Adur and Suondi Niesu. It is also interesting to observe an intermediate stage towards affrication in the Jiaojihe (literally ‘intercourse river’ or 交际河) variety of Adur Niesu, which is to the south of Butuo and adjacent to the northeastern border of Yunnan. In Jiaojihe variety, the velar plosive is kept and the fricative is epenthesized. This could be considered as a shift of place of articulation from velar plosive to retroflex affricate, and is probably a feature of Proto-Adur Niesu.

Table 3.

Examples of affrication in Niesu.

Another innovation is the insertion of a medial /w/ to form diphthongs after velars (see Matisoff 2006; Bradley 2008). See examples in Table 4. The diphthongization is still stable in Adur Niesu. According to Lama (2022), the diphthongization, however, is being lost among young Suondi Niesu speakers, while this feature has still been kept among the elder Suondi speakers.

Table 4.

Examples of diphthongization in Niesu (Lama 2022, with revision).

Moreover, velars in Nuosu are more palatalized in Suondi Niesu and Adur Niesu, if followed by the front vowel /i/ (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Examples of palatalization in Adur Niesu.

There are also phonological features which make Adur Niesu distinctive from Suondi Niesu. Table 3 shows that Adur Niesu retroflexizes the alveolar affricates in Suondi Niesu. The retroflexization, as a typical feature of Adur Niesu, is the reflex of PL or PTB *r and PL *ʃ or *s; see Table 6.

Table 6.

Examples of retroflexes in Adur Niesu.

Vowel-wise, the front vowel /i/ in Suondi Niesu, as well as Nuosu, corresponds to back vowel /ɯ/ in Adur Niesu if they are preceded by alveolo–palatal sounds (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Examples of correspondence to back vowel /ɯ/ in Adur Niesu.

3. Segmental Phonology

This section starts with Adur Niesu consonants and then moves on to vowels. After introducing the syllable and the phonotactics, segmental changes in both vowels and consonants will be covered.

3.1. Consonants

Table 8 demonstrates the 41 phonemic consonants of Adur Niesu: nine plain plosives, three prenasalized plosives, eleven fricatives, four nasals, two laterals, nine affricates and three prenasalized affricates. Suondi Niesu has the same consonant inventory as Adur Niesu (Lama 2012; Mise 2020). Compared with Nuosu, Adur Niesu lacks voiceless nasals /m̥/ and /n̥/ (see Section 2). Depending on whether a consonant can precede either the unrounded palatal [j] or the rounded labiovelar [w], Adur Niesu consonants can be divided into two groups: the J-group, marked in the solid box, and the W-group, marked in the dotted box. The other consonants cannot be followed by the glides.

Table 8.

Adur Niesu consonants.

3.1.1. Plain Plosives

The plain plosives are differentiated from the prenasalized plosives (see Section 3.1.5). They are produced through three places of articulation: bilabial, dental, and velar, as shown in Table 9, respectively. The three-way contrast among the plain plosives is achieved with voiced vs. voiceless unaspirated vs. voiceless aspirated. While the velar group cannot go with the J-glide, the bilabial and dental groups cannot go with the W-glide. It should be noted that the diphthongs [jɛ] and [wɛ] are two allophones of /ɛ/ and [wi] is an allophone of /i/ (see Section 3.2.1).

| 1 | a | bi55 | ‘to emerge, come out’ | bɛ33 [bjɛ33] | ‘male penis’ |

| pi55 | ‘to take out, make appear’ | pɛ33 [pjɛ33] | ‘to jump’ | ||

| phi55 | ‘classifier (e.g., of limbs, legs)’ | phɛ33 [phjɛ33] | ‘to foster the domestic animals in another family’ | ||

| b | di33 | ‘be wicked’ | dɛ33 [djɛ33] | ‘to make, manufacture’ | |

| ti33 | ‘only’ | tɛ33 [tjɛ33] | ‘to hold, to embrace’ | ||

| thi33 | ‘to mean, to refer to’ | thɛ33 [thjɛ33] | ‘to exchange’ | ||

| c | ga33 | ‘road’ | gi33 [gwi33] | ‘to leave’ | |

| ka33 | ‘to take, hold’ | kɛ33 [kwɛ33] | ‘to estimate’ | ||

| kha33 | ‘to want’ | khi33 [khwi33] | ‘to share’ |

Table 9.

Adur Niesu plosives.

3.1.2. Fricatives

The eleven fricatives are articulated at six places: bilabial, dental, retroflex, alveolo–palatal, velar and glottal (see Table 10).

Table 10.

Adur Niesu fricatives.

At each place, except glottal, the fricative pair contrasts in terms of voicing. The five pairs of fricatives are exemplified in the following minimal pairs. No fricatives can go with a glide, neither the J-glide nor the W-glide.

| 2 | a | vi55 | ‘pig’ | fi55 | ‘cliff, stomach’ |

| b | zi55 | ‘to pay off, to unload’ | si55 | ‘to kill’ | |

| c | ʑo33 | ‘sheep’ | ɕo33 | ‘to grow, to raise’ | |

| c | ʐa33 | ‘to shout’ | ʂɯ33 | ‘be toilsome’ | |

| d | ɣo33 | ‘blue, green’ | xo33 | ‘a ring (for keeping animals or for crematorium)’ | |

| e | - | ho33 | ‘to marry’ |

3.1.3. Nasals and Laterals

The nasals have four places of articulation: bilabial, dental, alveolo–palatal and velar, and the laterals have just one: dental (see Table 11).

Table 11.

Adur Niesu nasals and laterals.

Unlike Nuosu, the Niesu bilabial and dental nasals do not have a voicing contrast. They can go with the J-glide. The velar nasal can go with the W-glide.

| 3 | a | mi33 | ‘name’ | b | ma55 | ‘to teach’ | c | mɛ33 [mjɛ33] | ‘to lift with feet (as in wrestling)’ |

| ni33 | ‘female’ | na55 | ‘to coax’ | nɛ33 [njɛ33] | ‘black’ | ||||

| - | ŋa55 | ‘to install’ | ŋi33 [ŋwi33] | ‘front’ | |||||

| ȵi33 | ‘also’ | ȵa55 | ‘be late’ |

There is a contrast between voiced /l/ and voiceless /ɬ/. When the laterals precede the front vowel /ɛ/, they may be palatalized, showing free variation.

| 4 | a | li55 | ‘to lick’ | b | lɛ33 | ‘a verbal classifier (e.g., amount of the effort)’ | [lɛ33] | or | [ljɛ33] |

| ɬi55 | ‘be young’ | ɬɛ33 | ‘to extract’ | [ɬɛ33] | or | [ɬjɛ33] |

3.1.4. Affricates

Niesu, both Adur and Suondi, has three sets of affricates, produced at dental, retroflex and alveolo–palatal, respectively. Each set shows a three-way contrast in terms of voicing and aspiration, as exemplified below (see Table 12).

| 5 | a | dzi33 | ‘be left over’ | tsi33 | ‘to leave something behind’ | tshi33 | ‘to fall quickly’ |

| b | ɖʐɯ33 | ‘money’ | ʈʂɯ33 | ‘to feed, make eat’ | ʈʂhɯ33 | ‘rice, crop’ | |

| c | dʑi33 | ‘to fall down’ | tɕi33 | ‘a classifier (e.g., clothes)’ | tɕhi33 | ‘to arrive’ |

Table 12.

Adur Niesu affricates.

3.1.5. Prenasalized Consonants

Voiced plosives and affricates are prenasalized in Adur Niesu (see Table 13). The prenasalized consonants are treated here as unitary segments, not consonant clusters, on the ground that (1) they are contrastive with other consonants, such as ndo21 ‘to fall down’ vs. do21 ‘speech, word’, ŋga33 ‘be clever’ vs. ga33 ‘road’, and nɖʐa33 ‘to sprinkle water for cooking the corn rice’ vs. ɖʐa33 ‘sparrow’; (2) the nasal is always homorganic with the following plosives or affricates; and (3) the nasal–obstruent onsets only appear in the syllable-initial position. Lama (1998) also considers prenasalized obstruents in Nuosu, a close dialect of Adur Niesu, unitary segments, not consonant clusters, after acoustic analysis.

Table 13.

Adur Niesu prenasalized consonants.

The prenasalized plosives can also be followed by the glides.

| 6 | a | mbi33 | ‘to divide’ | mbɛ33 [mbjɛ33] | ‘to shoot’ |

| b | ndo33 | ‘to drink’ | ndɛ33 [ndjɛ33] | ‘a kind of black bowl painted with lacquer tree liquid’ | |

| c | ŋga33 | ‘be clever’ | ŋgi33 [ŋgwi33] | ‘to chew’ | |

| d | ndza55 | ‘adjacency’ | |||

| e | nɖʐa55 | ‘be good’ | |||

| f | ndʑi55 | ‘to catch’ |

3.1.6. Glides

Adur Niesu distinguishes between two glides: the unrounded palatal j and the rounded labiovelar w. The former is non-phonemic and the latter is phonemic. The glides are treated as part of the rhyme of a syllable, but not an element in a complex consonant. The reason is based on economy. By doing this, the sum of the diphthongs formed by the two glides is only four, including three allophonic diphthongs, [wɛ], [wi] and [jɛ] (see Section 3.2.1), and one phonemic diphthong, /wa/ (see Section 3.2.4), exemplified below. Bradley (2008) treated the glide /w/ as an element in complex consonants, or labialized velars. However, if similar treatment is made to the glide j, there would be as many as 17 complex consonants, including 13 allophonic complex consonants, such as [bj], [pj], [phj], [dj], [mj], and [lj] and four phonemic ones: gw, kw, khw and ŋw. This greatly exceeds the sum of the diphthongs formed by the two glides.

| 7 | a | pɛ33 [pjɛ33] | ‘to jump’ | thɛ33 [thjɛ33] | ‘to exchange’ |

| b | gɛ33 [gwɛ33] | ‘to compete with speaking skills’ | khɛ33 [khwɛ33] | ‘to chop’ | |

| c | gwa33 | ‘be of high capacity’ | khwa33 | ‘to share excessive important livestock, e.g., female pig, cattle (but need to pay back)’ | |

| ga33 | ‘road’ | kha33 | ‘to want’ | ||

| d | gi33 [gwi33] | ‘to leave, to go’ | khi33 [khwi33] | ‘to share’ |

3.2. Vowels

There are 10 monophthongs and one diphthong in Adur Niesu: /i/, /ɨ/, /ɯ/, /o/, /u/, /ɛ/, /ɨ̠/, /a/, /ɔ/, /u̠/, and /wa/. Lama (2012), Mahai (2015, 2019) and Mise (2020) reported similar monophthongs in Suondi Niesu. But different symbols are used, namely, the /ɿ ɿ̠/ set in Mise (2020) is represented as /ɨ ɨ̠/ in the present study, and /e/ in Lama (2012) as /ɛ/ in the present study. All Adur vowels are oral. The monophthongs are organized by height (high, mid, low) and backness (front, central, back). A feature of Adur Niesu vowels is high vowel fricativization, occurring with the two high central vowels, /ɨ/ and /ɨ̠/, and the two high back vowels /u/ and /u̠/.

It should be noted that the Adur vowel /ɯ/ is more advanced and lower than the cardinal IPA [ɯ]. Due to this deviation, it is not impossible to transcribe this vowel as /ə/, such as in the Nuosu vowel inventory in Lama (2002). In the present study, /ɯ/ is used, mainly because the Adur Niesu /ɯ/ is categorically closer to the cardinal IPA [ɯ] in terms of vowel height and backness. This symbol /ɯ/ is also adopted in describing Nuosu vowels (Lama 1998; Edmondson et al. 2017).

Another way of organizing Niesu vowels is to categorize them into tense and lax vowels (Chen et al. 1985; Lama 2002) (see Table 14). This is useful for the description of vowel assimilation (see Section 3.4.2). It should be noted that the tense/lax contrast in the tradition of Southeast Asian languages have been applied in reversed fashion to the terms that are used in talking about Germanic languages (Maddieson and Ladefoged 1985). The principal component of the tense/lax distinction in Adur Niesu, as well as other Yi languages, is a difference in the laryngeal setting, namely, the tense vowels are more laryngealized than the lax ones (Lama 2002; Esling and Edmondson 2002). Therefore, the lax vowels are closer in the vowel space and, thus, higher, while the tense vowels are more open and, thus, lower (Edmondson et al. 2017). Therefore, Adur Niesu monophthongs can be paired as below. This pairing also displays frequent assimilation results discussed in Section 3.4.

Table 14.

Tense/lax pairs of monophthongs in the Adur dialect.

3.2.1. Front Vowels

The Adur Niesu front vowels are distinguished by height. The minimal pairs are below.

| 8 | a | fi33 | ‘to throw’ | fɛ33 | ‘mouse’ | fa33 | ‘golden pheasant’ |

| b | dzi33 | ‘be left over’ | dzɛ33 | ‘to carve’ | dza33 | ‘rice, food’ | |

| c | tshi33 | ‘ten’ | tshɛ33 | ‘deer’ | tsha33 | ‘be hot’ | |

| d | tɕhi33 | ‘to arrive’ | tɕhɛ33 | ‘to jump’ | tɕha33 | ‘to caw (e.g., crow)’ |

The vowel /i/ cannot follow the retroflexes and the velar fricatives. It has an allophone [wi] when it occurs with velar stops.

| 9 | a | ŋgi33 | [ŋgwi33] | ‘to chew’ |

| b | gi33 | [gwi33] | ‘to leave’ | |

| c | ki33 | [kwi33] | ‘to dare’ | |

| d | khi33 | [khwi33] | ‘to share’ | |

| e | ŋi33 | [ŋwi33] | ‘front’ |

The vowel /ɛ/ has two diphthong allophones, [jɛ] and [wɛ]. The diphthong [jɛ] occurs when it follows the J-group consonants and the diphthong [wɛ] occurs when it follows the W-group consonants of velar.

| 10 | a | mbɛ33 | [mbjɛ33] | ‘to shoot’ | gɛ33 | [gwɛ33] | ‘to compete with speaking skills’ |

| b | mɛ33 | [mjɛ33] | ‘to lift with feet’ | khɛ33 | [khwɛ33] | ‘to chop’ | |

| c | ɬɛ33 | [ɬjɛ33] | ‘to extract’ | (o55)ŋɛ33 | [ŋwɛ33] | ‘be hungry’ | |

| d | nɛ33 | [njɛ33] | ‘black’ | kɛ33 | [kwɛ33] | ‘to estimate’ |

3.2.2. Central Vowels

Adur central vowels contrast one another in terms of height. The contrast between ɨ and ɨ̠, regarding the retractedness or tenseness, also exists in Nuosu (Edmondson et al. 2017).

| 11 | a | pɨ33 | ‘to exhibit speaking skills’ | pɨ̠33 | ‘be not generous’ |

| b | phɨ33 | ‘be painful, be spicy’ | phɨ̠33 | clf (for farmland) | |

| c | zɨ33 | ‘to buy’ | zɨ̠33 | ‘to press’ | |

| d | ʂɨ33 | ‘to die’ | ʂɨ̠33 | ‘to roar’ |

Vowels ɨ and ɨ̠ only occur with 17 consonants: the three plain bilabial plosives, the six dental fricatives and affricates, the six retroflex fricatives and affricates, and the two dental laterals. Both of them are subject to high vowel fricativization, each having two allophones in the form of fricative vowels, namely, [z̩] and [z̩̠], when they follow the plosives and the dentals, and [ʐ̍] and [ʐ̠̍] when they follow the retroflex sounds. Therefore, the phonetic realizations of the examples in (11) are (12a) to (12d). See more examples in (12e) to (12m). According to Edmondson et al. (2017, p. 89), Nuosu expresses ‘dragon’ with the fricative vowel [v] as an allophone of /u/, thus transcribed phonetically with labialization: l˞ʷː33 ‘dragon’ (cf. lu33 as the phonemic form). However, in Adur Niesu, lip rounding is not observed in the pronunciation of ‘dragon’ (see 12l) or in the other examples transcribed with labialization in Edmondson et al. (2017). Therefore, the laterals are incompatible with /u/ and /u̠/ in Adur Niesu. Similar to Nuosu, the laterals in Adur Niesu will end up being rhoticized after the high vowel fricativization. Similar rhoticization is reported in Ersu, a Na–Qiangic language spoken in Liangshan (Chirkova and Handel 2013).

| 12 | a | pɨ | [pz̩33] | ‘to exhibit speaking skills’ | pɨ̠33 | [pz̩̠33] | ‘be not generous’ |

| b | phɨ33 | [phz̩33] | ‘be painful, spicy’ | phɨ̠33 | [phz̩̠33] | clf (for farmland) | |

| c | zɨ33 | [zz̩33] | ‘to buy’ | zɨ̠33 | [zz̩̠33] | ‘to press’ | |

| d | ʂɨ33 | [ʂʐ̍33] | ‘to die’ | ʂɨ̠33 | [ʂʐ̠̍33] | ‘to roar’ | |

| e | bɨ | [bz̩33] | ‘to give’ | (ʐɨ̠33)bɨ̠33 | [bz̩̠33] | ‘a bamboo trap’ | |

| f | sɨ33 | [sz̩33] | ‘again, still’ | sɨ̠33 | [sz̩̠33] | ‘tree’ | |

| g | dzɨ33 | [dzz̩33] | ‘to ride (horse)’ | dzɨ̠33 | [dzz̩̠33] | clf (for vehicles) | |

| h | tshɨ33 | [tshz̩33] | ‘he, she, it’ | tshɨ̠33 | [tshz̩̠33] | ‘generation’ | |

| i | ʐɨ33 | [ʐʐ̍33] | ‘be big’ | ʐɨ̠33 | [ʐʐ̠̍33] | ‘soul’ | |

| j | ɖʐɨ33 | [ɖʐʐ̍33] | ‘teeth’ | ɖʐɨ̠33 | [ɖʐʐ̠̍33] | ‘to exist’ | |

| k | ʈʂɨ33 | [ʈʂʐ̍33] | ‘to squeeze oil’ | ʈʂɨ̠33 | [ʈʂʐ̠̍33] | ‘to pull’ | |

| l | lɨ33 | [lz̩33] | ‘dragon’ | lɨ̠33 | [lz̩̠33] | ‘to shake’ | |

| m | ɬɨ33 | [ɬz̩33] | ‘wind’ | ɬɨ̠33 | [ɬz̩̠33] | ‘to escape’ |

The rounded vowel /o/ may be reduced to [ə] by some Adur Niesu speakers. Other than this, large-scale patterned vowel centralization is not found in Adur Niesu.

| 13 | a44ȵo33 | ‘many’ | [a44ȵo33] | or | [a44ȵə33] |

3.2.3. Back Vowels

Similar to /ɨ/ and /ɨ̠/, the vowel /u/ contrasts with /u̠/ in terms of retractedness. Although the Adur vowel /ɯ/ is more advanced and lower than the cardinal IPA [ɯ], it is discussed with other back vowels.

| 14 | a | phu33 | ‘price, value’ | phu̠33 | ‘to dig’ | - | |

| b | ʂu33 | ‘to do’ | - | ʂɯ33 | ‘to find’ | ||

| c | ŋgu33 | ‘to boast’ | ŋgu̠33 | ‘to rub with hands’ | ŋgɯ33 | ‘buckwheat’ |

The phonemic contrast between /u/ and /u̠/ is not symmetric. Consonants that can occur with /u/ may not have a contrast with /u̠/. For instance, zu33 ‘to irritate’ has no contrastive pair as *zu̠33, and khu33 ‘to steal’ lacks a contrast as *khu̠33. It is, therefore, observed that /u/ and /u̠/ start to merge as one phoneme. According to the main consultants, the following pairs are interchangeable, showing free variations.

| 15 | a | su̠33ga55 | ‘be rich’ | su̠33ga55 | or | su33ga55 |

| b | bu̠55 | ‘grass’ | bu̠55 | or | bu55 | |

| c | gu̠55 | ‘to sew the clothes’ | gu̠55 | or | gu55 | |

| d | ku̠55 | ‘to know how’ | ku̠55 | or | ku55 | |

| e | vu̠55 | ‘to run over’ | vu̠55 | or | vu55 | |

| f | fu̠55 | ‘to work hard’ | fu̠55 | or | fu55 | |

| g | mu̠55 | ‘to sip’ | mu̠55 | or | mu55 | |

| h | ŋgu̠55 | ‘to stab’ | ŋgu̠55 | or | ŋgu55 |

Another observation is that the retracted /u̠/ is forming a complementary distribution with /u/ by occurring with the high-level tone 55 only. While the lax /u/ bears tone 33, the tense /u̠/ bears tone 55 in (16). Mise (2020) also indicates that tone 55 causes vowel tenseness in Suondi Niesu. Therefore, it is possible for the two phonemes to merge or become allophonic in the future.

| 16 | a | du33 | ‘wing’ | *du̠33 | du̠55 | ‘be stealthy’ |

| b | ŋu33 | ‘be’ | *ŋu̠33 | (kɔ33lɔ33)ŋu̠55 | ‘be angry’ | |

| c | tu33 | ‘to lift’ | *tu̠33 | tu̠55(m̩33) | ‘be promising’ |

Both /u/ and /u̠/ are noteworthy in that they lead to syllabic consonants if they are preceded by /m/. It was clearly observed from the consultants that the two syllables below were not produced with any rounding of the lips.

| 17 | mu33 | [m̩33] | ‘to do’ | mu̠33 | [m̩̠33] | ‘to blow up’ |

Due to high vowel fricativization, like /ɨ/ and /ɨ̠/, /u/ and /u̠/ have an allophone of their own in the form of the fricative vowel [v̩] and [v̩̠] when they are preceded by velar consonants. It was observed from the consultants that the upper teeth touched the inner side of the lower lip when they pronounced these syllables, without any rounding of the lips.

| 18 | a | ŋgu33 | [ŋgv̩33] | ‘to boast’ | ŋgu̠33 | [ŋgv̩̠33] | ‘to rub with hands’ |

| b | gu33 | [gv̩33] | ‘be firm’ | gu̠33 | [gv̩̠33] | ‘to protect (food, cubs)’ | |

| c | ku33 | [kv̩33] | ‘to call’ | ku̠55 | [kv̩̠55] | ‘to know how’ | |

| d | khu33 | [khv̩33] | ‘to steal’ | - |

A final feature of /u/ and /u̠/ is that they may be substituted with a syllabic bilabial trill [ʙ̩] after labial and dental plosives. The trill substitution is subject to personal habit, thus forming free variation. But the trill substitution is more preferred after voiced labial and dental plosives, and less preferred after voiceless ones.

| /u/ | /u̠/ | ||||

| 19 | a | [bu21] or [bʙ̩21] | ‘a clan’ | [bu̠33] or [bʙ̩̠33] | ‘to write’ |

| b | [pu21] or [pʙ̩21] | ‘to carry’ | - | ||

| c | [phu33] or [phʙ̩33] | ‘value’ | [phu̠33] or [phʙ̩̠33] | ‘to dig’ | |

| d | [du33] or [dʙ̩33] | ‘wing’ | [du̠55] or [dʙ̩̠55] | ‘be stealthy’ | |

| e | [tu33] or [tʙ̩33] | ‘to lift’ | - | ||

| f | [thu33] or [thʙ̩33] | ‘silver’ | [thu̠33 (or thʙ̩̠33) ʂa33] | ’a kind of evil spirit’ | |

| g | [mbu33] or [mbʙ̩33] | ‘be trapped’ | [mbu̠33] or [mbʙ̩̠33] | ‘to squint’ | |

| h | [ndu21] or [ndʙ̩21] | ‘to beat’ | [tjɛ33ndu̠33 (or ndʙ̩̠33)] | ‘be fat’ |

The mid-high oral vowel /o/ forms a phonemic contrast with the mid-low one /ɔ/ in terms of the openness of the mouth.

| 20 | a | bo33 | ‘mountain’ | bɔ33 | ‘to demand’ |

| b | pho33 | ‘to run’ | phɔ33 | ‘to reverse’ | |

| c | ko33 | ‘side, location’ | kɔ33 | ‘be capable’ |

3.2.4. Diphthong

While no diphthong is reported in the Nuosu vowel inventory (Lama 1998, 2002; Gerner 2013; Edmondson et al. 2017), different numbers of diphthongs in Suondi Niesu are reported: /ie ui ue/ in Lama (2012), /uɑ ue ui/ in Mahai (2015) and /ua ui/ in Mise (2020). Due to the close relation between Suondi and Adur Niesu, it is suspected that not all reported diphthongs in Suondi Niesu are phonemic.

In Adur Niesu, phonetically, there are four diphthongs, [jɛ], [wɛ], [wi] and [wa]. But the only phonemic diphthong in Adur Niesu is /wa/. It can only occur with velar consonants, or the W-group. Minimal pairs are as shown below.

| 21 | a | gwa33 | ‘be of large capacity’ | ga33 | ‘to wear’ |

| b | kwa33 | ‘fire pit’ | ka33 | ‘to take’ | |

| c | khwa33 | ‘to share excessive important livestock, e.g., female pig, cattle (but need to pay back)’ | kha33 | ‘to want’ | |

| d | ŋwa55 | ‘to break apart’ | ŋa55 | ‘to install’ |

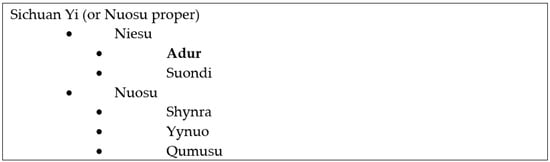

3.3. The Syllable and Phonotactics

Adur Niesu syllable structure is relatively simple. All are open syllables. Adur Niesu segments are organized into syllables as below (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Syllable structure of Adur Niesu.

The onset can be any of the 41 consonants. The on-glides are either j or w. The vowel slot can be filled by any of the 10 monophthongs or the syllabic consonants if there is no glide in the syllable. The J-glide only occurs with /ɛ/, and the W-glide occurs with all front vowels, namely, /i/, /ɛ/ and /a/. But syllables involving a glide must be preceded by an onset, such as (22a) to (22f). In this case, all slots are filled. The onset and on-glide slots can be optional; see (22g) to (22h). The following are examples of all possible syllables in Adur Niesu. Most Adur Niesu syllables are made up of a consonant and a vowel.

| 22 | a | ŋgwi33 | ‘to chew’ |

| b | kwi33 | ‘to dare’ | |

| c | mbjɛ33 | ‘to shoot’ | |

| d | gwɛ33 | ‘to break’ | |

| e | khwa55 | ‘be happy’ | |

| f | ŋwa55 | ‘to break apart’ | |

| g | a44mo33 | ‘mother’ | |

| h | o33 | ‘head’ |

Without considering the three basic tones of Adur Niesu, there are 308 attested syllables. Allophonic realizations are indicated in Table 15.

Table 15.

Adur Niesu phonotactics.

3.4. Segmental Changes in Vowels

In the previous sections, some vowel changes were discussed: allophones of the front vowels in Section 3.2.1, occasional vowel reduction in Section 3.2.2, and high vowel fricativization in Section 3.2.2 and Section 3.2.3. In the present section, another four vowel changes are presented: vowel lowering, vowel centralization, vowel assimilation and vowel fusion.

3.4.1. Vowel Lowering and Centralization

The high vowel /u/ may be lowered to /o/, forming a free variation. The reason why the change is considered a lowering, rather than a raising, is that the high vowel /u/ is more common in the speech of both the elder and young population.

| 23 | a | su44ʐɨ33 | ‘the elder’ | [su44]~[so44] |

| b | ʑu33 | ‘to catch’ | [ʑu33]~[ʑo33] |

It is common for the Adur Niesu back vowel /u/ to be centralized as /ɨ/ if it follows the sibilant fricatives.

| 24 | nɛ33 | ‘black’ | + | su33 | ‘people’ | → | nɛ33su33 | or | nɛ33sɨ33 | ‘Niesu people or Niesu language’ |

| a21 | + | su55 | → | a21su55 | or | a21sɨ55 | ‘we (inclusive)’ | |||

| zo33 | ‘study’ | + | ʂu33 | nominalizer | → | zo33ʂu33 | or | zo33ʂɨ33 | ‘those (who are) studying’ |

3.4.2. Vowel Assimilation

Vowel assimilation is another case of vowel lowering in Adur Niesu. Nearly all assimilations in Adur Niesu are regressive, and most occur between tense and lax vowels (see Section 3.2), namely, the preceding lax vowel will be lowered to a tense vowel, or become more laryngealized; see Table 14. Recall in Section 3.2 that the tense vowels are treated as those which are more laryngealized than the lax ones, and thus have a lower position than the lax ones (Maddieson and Ladefoged 1985; Lama 2002; Edmondson et al. 2017). Therefore, the rhyme of the first syllable is assimilated in terms of the tenseness of the following rhyme. Compare the examples in (25a) to (25d). /ɛ/, /a/ and /ɨ̠/, belonging to the tense group, lower the vowel of the first syllable from the lax one to its tense counterpart, namely, from [o] to [ɔ] and from [i] to [ɛ], respectively. But if the following rhymes do not belong to the tense group, assimilation does not occur.

| 25 | a | o33 | ‘head’ | + | ȵɛ33 | ‘hair’ | → | ɔ33ȵɛ33 | ‘hair’ |

| o33 | ‘head’ | + | ʨhɯ33 | → | o33ʨhɯ33 | ‘head’ | |||

| b | o33 | ‘related to mother’s brother’ | + | ka55 | ‘middle’ | → | ɔ33ka55 | ‘mother’s middle brother’ | |

| o33 | ‘related to mother’s brother’ | + | ɖʐɨ̠55 | ‘young’ | → | ɔ33ɖʐɨ̠55 | ‘mother’s younger brother’ | ||

| o33 | ‘related to mother’s brother’ | + | ʐɨ33 | ‘big’ | → | o44ʐɨ33 | ‘mother’s elder brother’ | ||

| c | ȵi21 | ‘two’ | + | ma33 | clf | → | ȵɛ21ma33 | ‘two pieces’ | |

| ȵi21 | ‘two’ | + | bu21 | ‘clan’ | → | ȵi21bu21 | ‘two clans’ | ||

| d | ŋi33 | ‘mouth’ | + | lɛ33 | → | ŋɛ33lɛ33 | ‘mouth’ | ||

| ŋi33 | ‘mouth’ | + | tɕo33 | ‘direction’ | → | ŋi33tɕo33 | ‘front’ |

More examples are as below.

| 26 | a | ʐɨ33 | ‘water’ | + | tsɨ̠33 | ‘to get drenched’ | → | ʐɨ̠33tsɨ̠33 | ‘to get drenched by rain’ |

| b | mu33 | ‘ground’ | + | lɨ̠33 | ‘to shake’ | → | mu̠44lɨ̠33 | ‘earthquake’ | |

| c | o33 | ‘head’ | + | ma33 | general classifier | → | ɔ33ma33 | ‘head, mind’ | |

| d | ni33 | ‘female’ | + | nɖʐa55 | ‘be good, pretty’ | → | nɛ33nɖʐa55 | ‘beautiful woman’ | |

| e | do21 | ‘speech’ | + | ma33 | general classifier | → | dɔ21ma33 | ‘speech, word’ | |

| f | zɯ33 | ‘son, man’ | + | khɔ33 | ‘be capable’ | → | za33khɔ33 | ‘hero, brave man’ | |

| g | ʑo33 | ‘sheep’ | + | la33 | ‘breeding’ | → | ʑɔ33la33 | ‘ram that is not castrated’ | |

| h | zɯ33 | ‘son, man’ | + | tɕhɛ33 | ‘hard’ | → | za33tɕhɛ33 | ‘tough man’ | |

| i | ni33 | ‘red’ | + | ʈʂɨ̠33ʈʂɨ̠33 | ‘ide’ | → | nɛ44ʈʂɨ̠33ʈʂɨ̠33 | ‘bright red’ | |

| j | ni33 | nɖʐa55 | + | ni33 | vɛ33 | → | nɛ33nɖʐa55nɛ33vɛ33 | ‘beautiful woman’ |

Some of the assimilations are more phonetic in nature, since they can be restored to the original vowel in slow and careful speech; but some are more morpholexical in nature, since they cannot be restored to the original vowel, even using slow and careful speech. If restoration is forced in the latter case, new meanings will be produced. All examples in (27) are phonetic assimilations and those in (28) are morpholexical assimilations.

| 27 | casual speech | careful speech | |||

| ‘tough man’ | za33khɔ33 | zɯ33khɔ33 | |||

| ‘brightly red’ | nɛ44ʈʂɨ̠33ʈʂɨ̠33 | ni44ʈʂɨ̠33ʈʂɨ̠33 | |||

| ‘see’ | ɣo21ŋo33 | ɣɯ21ŋo33 | |||

| 28 | With assimilation | Without assimilation | ||

| dɔ21ma33 | ‘speech, language’ | do21ma33 | ‘one piece of speech’ | |

| ʑɔ33la33 | ‘ram’ | ʑo33la33 | ‘the sheep come’ | |

| za33tɕhɛ33 | ‘capable man’ | zɯ33tɕhɛ33 | ‘the man is capable’ | |

| nɛ33ndʐa55 | ‘beautiful woman’ | ni33ndʐa55 | ‘the woman is beautiful’ | |

| ɔ³³ʈʂɨ̠55 | ‘plait’ | o³³ʈʂɨ̠55 | ‘to plait’ | |

| ɔ33ma33 | ‘head, mind’ | o33ma33 | ‘a head’ |

The tenseness/laxness-induced assimilation can also be relative. As long as the following vowel is tenser, or lower, than the preceding vowel, regressive assimilation can be triggered. For example, although /o/ is laxer than /ɔ/, it is tenser and lower than /ɯ/; therefore, assimilation occurs in (29). Since /u/ is not tenser than /i/, assimilation is not triggered in ȵi21bu21 ‘two households’ in (25c) (cf. ȵɛ21ma33 ‘two pieces’).

| 29 | ɣɯ21 | ‘to obtain’ | + | ŋo33 | ‘to see’ | → | ɣo21ŋo33 | ‘see’ |

3.4.3. Vowel Fusion

Vowel fusion in Adur Niesu results in vowel substitution of the rhyme of the preceding syllable, such as ʑa33 (ʑi33 ‘to go’ + a33 ‘attitudinal marker’) ‘let’s go’. Although it is also possible for vowel fusion to occur intraclausally, it is more common at the clause end. In (30) and (31), the rhyme of the first syllable is replaced by the following vowel at the clause’s final position, and in (32), the vowel fusion occurs in the clause.

| 30 | la33=sɨ33 o44 | → | la33=so44 |

| come=rep pfv | come=rep.pfv | ||

| ‘(He) came again.’ | |||

| 31 | ʂu33 + o44 → ʂɔ44 | |||||||

| lɯ33 | tshɨ33 | tɕi33 | ʂa33mu33ȵi33 | a33tshi33~tshi33 | mu33 | ndu21 | ʂɨ21=ʂɔ44. | |

| cow | this | clf | toilsome:do:exst | extreme~redpl | do | beat | die=nmlz.att | |

| ‘This cow was beaten to death pathetically.’ | ||||||||

| 32 | tshɨ33 + a21=sɨ21 → tsha21=sɨ21 | |||||||

| ŋo33 | tsha21=sɨ21 | |||||||

| 1pl | 3sg.neg=know | |||||||

| ‘We do not know it.’ | ||||||||

3.5. Segmental Changes in Consonants

Segmental changes in Adur Niesu consonants are not widely observed. Lenition and clanlects are presented.

3.5.1. Lenition of the Velar Consonants

Briefly, the velar stops can be lenited in spontaneous speech as velar fricatives; see (33).

| 33 | lenition | ŋo33 ‘we’ | → | ɣo33 |

| lenition | ko33 ‘when, if’ | → | xo33 | |

| lenition | ga44ɖʐɨ33 ‘absolutely’ | → | ɣa44ɖʐɨ33 |

3.5.2. Aspiration of the Clanlects

Variations in aspiration change between different clans are found, or ‘clanlects’. One of the main consultants is a descendant of the dʑɛ21nɛ33 clan, and another one is of the su̠33ga55 clan. Both of them live in the same village since they were born. The following two words are not aspirated in the speech of the dʑɛ21nɛ33 descendant, while they are aspirated in the speech of the su̠33ga55 descendant. But the aspirated affricate in the three words has wider usage among Adur Niesu speakers. Other than the two words, both consultants share similar phonological system of Adur Niesu.

| dʑɛ21nɛ33 clan | su̠33ga55 clan | |||

| 34 | a | ‘he, she, it’ | tsɨ33 | tshɨ33 |

| b | ‘this’ | tsɨ33 | tshɨ33 |

3.6. Syllable Reduction

It is common for Adur Niesu syllables to be reduced in continuous speech. There are three types of syllable reduction being observed in the field: complete reduction including the segment and tone, partial reduction with a floating tone left, and partial reduction with the initial consonant left.

The syllable is so reduced that a particle is left to signal the existence of a clause; see (35b) where tshɨ21mu33 ‘doing so’ is reduced.

| 35 | a. | tshɨ21 | mu33 | ta33, | hɛ33ŋga55 | lɯ33o33=sa44 | lɯ33ʂɨ33 | ŋgɔ33 | la33. | |

| this | do | nf | Han Chinese | cow:head=com | cow:foot | collect | come | |||

| ‘By doing so, the Han Chinese come to collect the head and feet of the (killed) cow.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | ta33, | he33ŋga55 | lɯ33o33=sa44 | lɯ33ʂɨ33 | ŋgɔ33 | la33. | ||||

| nf | Han Chinese | cow:head=com | cow:foot | collect | come | |||||

| ‘By doing so, the Han Chinese come to collect the head and feet of the (killed) cow.’ | ||||||||||

It is often the segments of the whole syllable being deleted. After the reduction, the tone becomes a floating tone and reassociates itself onto the preceding syllable. For example, in (36a) to (36c), the second syllable is reduced, namely, ʂɨ in a33ʂɨ55 ‘what’, sɨ in a21sɨ21thɯ33 ‘when’ and hi in a21hi33 ‘cannot’. But the tone is left. The tonal trace can be observed on the remaining preceding syllable. Namely, the original tone of the preceding syllable is overridden by the floating tone, where a33 changes to a55 in (36a) and a21 changes to a33 in (36c). Since the first syllable a21 bears the same 21 tone with the deleted syllable in (36b), the overriding is not evident. In (36a) and (36b), other than the syllable reduction, the fricative glottal /h/ can often be epenthesized, namely, ha55 and ha21.

| 36 | a | a33ʂɨ55 | tsɨ55 | → | a55 / ha55 | tsɨ55 | |

| what | do | what | do | ||||

| ‘to do what’ | |||||||

| b | a21sɨ21thɯ33 | → | a21thɯ33 / ha21thɯ33 | ||||

| ‘which:time’ | ‘which:time’ | ||||||

| ‘when’ | |||||||

| c | a21hi33 mu33 (neg=can do) ‘cannot’ → a33mu33 | ||||||

| tɯ21 | ʑi33 | a33 | mu33 | thɯ33 | dʐɨ̠33 | ||

| rise | go | neg.can | do | place | exst | ||

| ‘(Someone) cannot stand up, but keep staying there.’ | |||||||

In a polar interrogative, on the surface, there seems to be a tone change: 55 > 21 / 55 _. However, the tone lowering from 55 to 21 is not a tone change (cf. tone sandhi in Section 4.2 and Section 4.3), but in fact the result of the floating tone associated with the interrogative particle a21 after syllable reduction, which is exemplified below. The floating tone of the interrogative particle overrides the tone of the preceding syllable. Meanwhile, the preceding high front vowel [i] is assimilated by the interrogative particle a21 and lowered to [ɛ] (see Section 3.4). If the lowered vowel [ɛ] occurs with the J-group consonants, it will subsequently change to the phonetic diphthong allophone [jɛ], namely, pɛ21 [pjɛ21] in (37b) and ndɛ21 [ndjɛ21] in (37d).

| basic form | meaning | reduplicated form + interrogative particle | result | meaning | ||

| 37 | a | si55 | ‘to kill’ | si55~si55 + a21 | si55~sɛ21 | ‘to kill or not’ |

| b | pi55 | ‘to dig’ | pi55~pi55 + a21 | pi55~pɛ21 | ‘to dig or not’ | |

| c | vi55 | ‘to shoulder’ | vi55~vi55 + a21 | vi55~vɛ21 | ‘to shoulder or not’ | |

| d | ma21ma21 ndi55 | ‘to bear fruit’ | ma21ma21 ndi55~ndi55 + a21 | ma21ma21 ndi55~ndɛ21 | ‘to bear fruit or not’ | |

| e | ndʐɨ33 ʑi55 | ‘to be drunk’ | ndʐɨ33 ʑi55~ʑi55 + a21 | ndʐɨ33 ʑi55~ʑɛ21 | ‘to be drunk or not’ |

It is particularly useful to contrast the above syllable reduction with reduplication for intensification in Adur Niesu. Without the effect of the interrogative particle, when two high-level tones are adjacent to each other, there is no change of the tone and of the vowel.

| basic form | meaning | reduplicated form | meaning | ||

| 38 | a | si55 | ‘to kill’ | si55~si55 | ‘to kill fiercely’ |

| b | ma21ma21 ndi55 | ‘to bear fruit’ | ma21ma21 ndi55~ndi55 | ‘to bear a lot of fruits’ | |

| c | ndʐɨ33 ʑi55 | ‘to be drunk’ | ndʐɨ33 ʑi55~ʑi55 | ‘to be quite drunk’ |

Moreover, the syllable reduction also occurs to other vowels bearing the high-level tone 55; see (39a) to (39c), accompanied by vowel assimilation. However, the syllable reduction does not occur to syllables bearing other non-high-level tones; see (39d) and (39e). Likewise, the vowel assimilation will not occur.

| basic form | meaning | reduplicated form | |||

| 39 | a | tʂɨ55 | ‘be correct’ | tʂɨ55~tʂɨ55 + a21 or tʂɨ55~tʂɨ̠21 | ‘be correct or not’ |

| b | sa55 | ‘to finish’ | sa55~sa55 + a21 or sa55~sa21 | ‘to finish or not’ | |

| c | pho55 | ‘to dig the earth’ | pho55~pho55 + a21 or pho55~phɔ21 | ‘to dig the earth or not’ | |

| d | phi33 | ‘be polite’ | phi44~phi33 + a21 | ‘be polite or not’ | |

| e | fi33 | ‘to throw’ | fi44~fi33 + a21 | ‘to throw or not’ |

Sometimes, the syllable may not be completely reduced, leaving not only the tone, but also the onset. The leftover will go with the preceding syllable; see (40). Mahai (2019) reports another kind of partial reduction, namely, the initial consonant is deleted, with only the rhyme left, such as ʑa21o55 for ʑa21ʑo55 ‘potato’ and ŋo21i55 for ŋo21ȵi55 ‘the two of us (exclusive)’. However, we did not have a similar observation about this reduction in Adur Niesu in the field.

| 40 | a21ŋu33 ‘now’ → aŋ33 | |||||||

| aŋ33 | tshi44~tshi33=ko44=na33, | li55sa33 | tshɨ21 | ma33 | ka33 | |||

| present | neat~neat=moment=dsc | official seal | one | clf | take | |||

| a33tu̠33 | ɔ21la33mu33hi55 | bɨ33 | xa33 | ʑi33 | o33 | di44. | ||

| Adur | name | give | away | go down | pfv | quot | ||

| ‘(Someone) said that at this exact moment, (you) took an official seal and went to give (it) to Uolamuhi who is from the Adur region.’ | ||||||||

Syllable reduction can also create the environment for vowel assimilation. For example, tshɨ21 mu33 ɔ44nɔ33 (this do if) ‘if it is like this’ changes to tshɔ33ɔ44nɔ33, with the syllable mu33 being deleted, namely, tshɨ33 ɔ44nɔ33, and tone 33 being reassociated to the preceding syllable and the rhyme then being assimilated by the following tenser vowel ɔ.

| 41 | a | o21, | tshɨ21 | mu33 | ɔ44nɔ33, | ŋo33 | tshɨ33 | a21=sɨ21. |

| intj | this | do | if | 1pl.excl | 3sg | neg=know | ||

| ‘Oh, if it is something like this, we do not know it.’ | ||||||||

| b | o21, | tshɔ33ɔ44nɔ33, | ŋo33 | tshɨ33 | a21=sɨ21. | |||

| intj | this | 1pl.excl | 3sg | neg=know | ||||

| ‘Oh, if it is something like this, we do not know it.’ | ||||||||

4. The Suprasegmentals

Adur Niesu employs suprasegmentals as an important means for lexical contrast, like many other syllable–tone languages of East and Southeast Asia. In Adur Niesu, two types of tonal alternation should be distinguished: tone sandhi and tone change. Similar distinction is made in Prinmi (Ding 2014) and in Yongning Na (or Narua) (Michaud 2017).

Tone sandhi refers to the phonologically conditioned tonal alternation by adjacent tones, regardless of the morphosyntactic factors. The most productive sandhi rule of Adur Niesu is 33 > 44 / _ 33, such as su33 ‘people’ + ʐɨ33 ‘big’ > su44ʐɨ33 ‘the elder’.

Tone change is governed by rules that are confined to specific morphosyntactic environments. It is the dominant form of tonal alternation in Adur Niesu. The tone change appears in the following morphosyntactic contexts: (1) compound words, (2) prefixed words, (3) patient marking, and (4) yes–no interrogation generated by reduplication.

Finally, floating tones in Adur Niesu can generate a surface kind of tonal alternation, although, in fact, it is the result of syllable reduction. After the syllable reduction, the tone becomes a floating tone and reassociates itself onto the preceding syllable, such as the so-called tonal change regarding the possessive pronouns, where the tone of the reduced genitive marker *ni21 of Proto-Nuosu proper was retained by the plain personal pronouns in Adur Niesu.

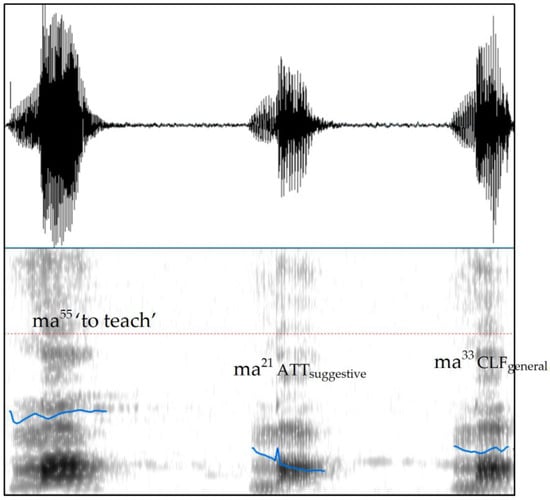

4.1. The Three Basic Tones

Identical to Suondi Niesu, Adur Niesu has three basic tones: high-level tone 55, mid-level tone 33, and low-falling tone 21. The minimal contrast between these three tonal categories is exemplified below (see Figure 5).

| 42 | a | di21 | ‘to say’ | di33 | ‘be not good’ | di55 | ‘to wear (shoes)’ |

| b | ti21 | ‘to bury’ | ti33 | ‘be only’ | ti55 | ‘to make wear (shoes)’ | |

| c | vi21 | ‘guest’ | vi33 | possessive pronominal enclitic | vi55 | ‘pig’ | |

| d | hi21 | ‘to say’ | hi33 | ‘house’ | hi55 | ‘eight’ | |

| e | tshɨ21 | ‘his, her, its’ | tshɨ33 | ‘he, she, it’ | tshɨ55 | ‘family line’ | |

| f | to21 | ‘can’ | to33 | ‘to respond’ | to55 | ‘to light up’ |

Figure 5.

Adur Niesu tones exemplified by syllable [ma].

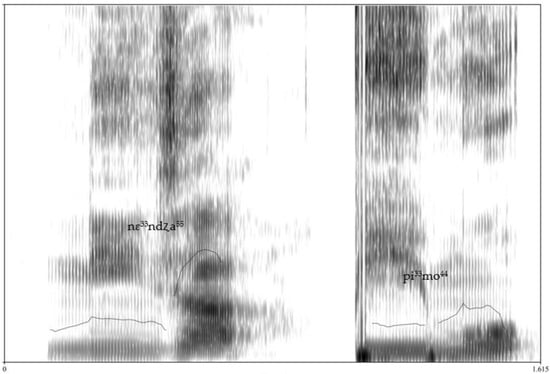

There is a 44 (high-mid level) tone in Adur Niesu. See Bradley (1990) for the discussion of tone 44 in Nuosu. However, it is seen largely in cases of tone sandhi, which often results from either tone 33 or tone 21 in syllable combination. There is no co-occurrence of tone 44 with tone 55 at the lexical level. In Figure 6, tone 44 is slightly higher than tone 33 in the word pi33mo44 ‘priest’, but tone 55 is much higher than tone 33 in the word nɛ33ndʐa55 ‘pretty woman’.

Figure 6.

Compare Adur Niesu tone 44 with tone 33 and tone 55.

Tone 44 often appears in particles at the clause boundary, such as the sequential clitic ɕi44 and change of state clitic o44 in (43), and clause linker lɯ44 in (44). If the clause boundary is occupied by content words, tone 44 is not used, such as lɨ̠33 ‘to trap’ in (44). If not used at the clause boundary, tone 44 only appears in a few morphemes in Adur Niesu as citation forms, namely, mo44 as a hesitator, sa44 the comitative, di44 the quotative, and ȵo44 the experiential clitic.

| 43 | no21 | a21mu33 | tshɨ33 | ȵɛ21 | ma33 |

| 2pl.poss | daughter | this | two | clf | |

| tʂhɨ55=ɕi44, | o33no33 | xa33 | a44nɛ33, | ||

| tie=seq | distance | release | after | ||

| no21 | zɯ33 | ma44 | sa33 | o44. | |

| 2pl.poss | son | clf.def | comfortable | csm | |

| ‘After (you) tie up your two daughters and abandon them in the wilderness, your son will recover.’ | |||||

| 44 | to55 | pa21nɛ21=ko33 | lɨ̠33, | ga21mo21=ko33 | tsi44 | tɯ33 | lɯ44, | |

| stamp | mud=loc | trap | road:big=loc | place inside | cont | clnk | ||

| bi55la33 | a33=to21 mu33 | thɯ33 | i55 | dʐɨ̠33 | ta33, …. | |||

| exit:come | neg=can do | t/here | lie | cont | nf | |||

| ‘(The horse, the bull and all the big beasts) stamped on (the frog) into the mud, (who was) being stuck firmly in the road2, and (the frog) could not come out, staying there,….’ | ||||||||

4.2. Tone Sandhi: 33 > 44 / _ 33

The most productive tone sandhi in Adur Niesu is 33 > 44 / _ 33, regardless of the morphosyntactic environment. Other phonological processes may also occur, such as vowel assimilation in (45f) and (45g). The fundamental function of this tone sandhi is to dissimilate two adjacent same tone.

| 45 | a | su33 ‘people’ | + | ʐɨ33 ‘big’ | → | su44ʐɨ33 | ‘the elder’ |

| b | a33 | + | nɛ33 | → | a44nɛ33 | ‘after’ | |

| c | bu33 | + | dzɯ33 | → | bu44dzɯ33 | ‘mate’ | |

| d | ɔ33 | + | nɔ33 | → | ɔ44nɔ33 | ‘if’ | |

| e | pu33 | + | thɯ33 | → | pu44thɯ33 | ‘Butuo (place name)’ | |

| f | ti33 ‘cloud’ | + | nɛ33 ‘black’ | → | tɛ44nɛ33 | ‘dark cloud, nimbostratus’ | |

| g | tʂhɯ33 ‘rice, oryza sativa’ | + | dza33 ‘grain’ | → | tʂha44dza33 | ‘rice’ |

This sandhi rule can also mark the compounding of the verbs. The rise to tone 44 suggests that it is a compound word and the interpretation is from left to right; see (46). But if the tone is not raised, namely, xɯ33dzɯ33 and ŋɯ33dzɯ33, the interpretation of xɯ33 and ŋɯ33 changes to ‘meat’ and ‘fish’, respectively. The expressions are thus understood as phrases, not words, meaning ‘to eat the meat’ and ‘to eat the fish’.

| 46 | a | xɯ33 ‘to cut off’ or ‘meat’ | + | dzɯ33 ‘eat’ | → | xɯ44dzɯ33 | ‘to cut and eat’ |

| b | ŋɯ33 ‘to borrow’ or ‘fish’ | + | dzɯ33 ‘eat’ | → | ŋɯ44dzɯ33 | ‘to borrow and eat’ |

However, exceptions about this lexical tone sandhi can easily be found in Adur Niesu, such as nɛ33su33 ‘the Niesu people’, ʐɨ33lo33 ‘well, sink’, ŋgɯ33fu33 ‘buckwheat pie’, and ȵɛ33ɖʐɨ33 ‘sun’. This sandhi pattern is also found in Nuosu (see Lama 1998 and Bradley 1990 for sandhi rules of Nuosu), but with higher productivity than in Adur Niesu. For example, this sandhi rule applies to bo44fu33 ‘cheekbone’ in Nuosu, but not to bo33fu33 ‘cheekbone’ in Adur Niesu.

This tone sandhi seldom occurs in phrases in Adur Niesu. In (47), where all expressions can be understood as phrases, this sandhi rule does not apply. For example, (47d) does not refer to a particular kind of snake, but a generic term to cover all snakes living or happening to be found in the water. However, this restriction seems less rigid in Nuosu. Gerner (2013) reported that the demonstrative would rise to tone 44 in Nuosu if there was a following classifier of tone 33, such as tshɨ44ma33 (this clf) ‘this one’ and tshɨ44bo33 (this clf.pl) ‘these ones’. In contrast, the tone of the demonstrative is not raised in Adur Niesu, namely, tshɨ33ma33 ‘this one’. According to the Adur consultants, if the demonstrative is raised in tone, it means emphasis. It is more natural to keep the original tone 33 in this combination.

| 47 | a | ʐɨ33 | ‘water, river’ | + | dʑi33 | ‘clean’ | → | ʐɨ33dʑi33 | ‘clean water’ |

| b | lɯ33 | ‘cow’ | + | tʂhɨ33 | ‘manure’ | → | lɯ33tʂhɨ33 | ‘cow’s manure’ | |

| c | ɣo33 | ‘bear’ | + | ʈʂɨ33 | ‘bile’ | → | ɣo33ʈʂɨ33 | ‘bile of the bear’ | |

| d | ʐɨ33 | ‘water, river’ | + | ʂɨ33 | ‘snake’ | → | ʐɨ33ʂɨ33 | ‘snake(s) in the water (not a kind of snake)’ |

4.3. Tone Sandhi: 21 > 44 / 21 _

This is another relatively productive sandhi rule in Adur Niesu. Similar to the sandhi rule 33 > 44 / _ 33, this rule is again a case of tone dissimilation. Unlike 33 > 44 / _ 33, the sandhi rule 21 > 44 / 21 _ mainly occurs at the phrasal level, such as the auxiliary verb constructions from (48a) to (48c) and the noun phrases from (48d) to (48e). Its effect at the word level is not commonly found in Adur Niesu, for example, sɨ21 ‘to curse’ + tɕhɯ21 ‘to revile’ → sɨ21tɕhɯ21 ‘to curse’. If the adjacent tones are different, this sandhi rule does not apply, for example, dzɯ33 ‘to eat’ + do21 ‘can’ → dzɯ33do21 ‘can eat’.

| 48 | a | ndu21 | ‘hit’ | + | to21 | ‘can’ | → | ndu21to44 | ‘can hit’ |

| b | sɨ21 | ‘know’ | + | to21 | ‘can’ | → | sɨ21to44 | ‘can understand’ | |

| c | pu21 | ‘carry’ | + | to21 | ‘can’ | → | pu21to44 | ‘can carry’ | |

| d | tshɨ21 | ‘his, her, its’ | + | ɖʐɨ21 | ‘lower part’ | → | tshɨ21ɖʐɨ44 | ‘beneath him/her/it (lit. the part below him/her/it)’ | |

| e | ŋa21 | ‘my’ | + | tɕo21 | ‘direction’ | → | ŋa21tɕo44 | ‘to me (lit. my direction)’ |

4.4. Tone Change in Compounds

Compounding is a productive means of word formation in Adur Niesu. Tone change can serve as a phonological criterion to distinguish compound words from phrases.

4.4.1. Tone 33 > 21/_ zɯ33

33 > 21 / _ zɯ33 occurs in compound words of animacy marked with the diminutive marker zɯ33, grammaticalized from the noun meaning ‘son’.

| 49 | a | tʂhɨ33 | ‘dog’ | + | zɯ33 | → | tʂhɨ21zɯ33 | ‘puppy’ |

| b | mu33 | ‘horse’ | + | zɯ33 | → | mu21zɯ33 | ‘pony’ | |

| c | ŋɯ33 | ‘fish’ | + | zɯ33 | → | ŋɯ21zɯ33 | ‘young fish’ | |

| d | ʂu33 | ‘pheasant’ | + | zɯ33 | → | ʂu21zɯ33 | ‘young pheasant’ |

If the tone change does not occur, the meaning is also changed, namely, it becomes a nominal–nominal genitive phrase meaning ‘the offspring of the animal′.2 Compare (50) with (49).

| 50 | a | tʂhɨ33 | ‘dog’ | + | zɯ33 | → | tʂhɨ33zɯ33 | ‘dog’s offspring’ |

| b | mu33 | ‘horse’ | + | zɯ33 | → | mu33zɯ33 | ‘horse’s offspring’ | |

| c | ŋɯ33 | ‘fish’ | + | zɯ33 | → | ŋɯ33zɯ33 | ‘fish’s offspring’ | |

| d | ʂu33 | ‘pheasant’ | + | zɯ33 | → | ʂu33zɯ33 | ‘pheasant’s offspring’ |

Moreover, if the compound words with the diminutive marker refer to inanimate beings, such as mountains, the tone change does not occur.

| 51 | a | bo33 | ‘mountain’ | + | zɯ33 | → | bo33zɯ33 | ‘small mountain’ |

| b | ʐɨ33 | ‘water, river’ | + | zɯ33 | → | ʐɨ33zɯ33 | ‘small river, creek’ | |

| c | sɨ̠33 | ‘tree’ | + | zɯ33 | → | sɨ̠33zɯ33 | ‘small tree’ | |

| d | tha33 | ‘jar’ | + | zɯ33 | → | tha33zɯ33 | ‘small jar’ |

This tone change does not happen to all animate beings if there is a ready expression for their offspring. For example, since there is an expression for ‘calf’, namely, ko33li33zɯ33, lɯ33zɯ33 is, therefore, a phrase, meaning ‘offspring of the cow’, without the tone change. Other examples are:

| Meaning | Terminology for offspring | ||||||||

| 52 | a | ʑo33 | ‘sheep’ | + | zɯ33 | → | ʑo33zɯ33 | ‘offspring of the sheep’ | ʑɔ33la33zɯ33 ‘lamb’ |

| b | lɯ33 | ‘cow’ | + | zɯ33 | → | lɯ33zɯ33 | ‘offspring of the cow’ | ko33li33zɯ33 ‘calf’ | |

| c | ʑɛ33 | ‘chicken’ | + | zɯ33 | → | ʑɛ33zɯ33 | ‘offspring of the chicken’ | ʑɛ33tsɨ55zɯ33 ‘chick’ |

4.4.2. Tones 33 > 21/_ pa55 and 33 > 21/_ pu33

The two rules of tone change are discussed together since both of them occur in similar semantic environment, namely, about the masculine gender of animate beings. The words are compounded with an animal formative and the masculine morpheme pa55 and pu33. Morpheme pa55 is a reflex of PTB *p/ba ‘male, father, 3rd pronoun’ and pu33 is of PTB *pu ‘male, masculine suffix’ (see Matisoff 2003). Adur Niesu uses the former to refer to ‘parents’, namely, pha55mo55, with additional aspiration. Both pa55 and pu33 will cause the preceding 33 tone to be lowered. The dog word tʂhɨ33 can go with either masculine morpheme, and its tone is lowered in both compounding; see (53a) and (53g). Bearing the male morpheme pa55, the word ‘horse’ mu21pa55 has extended its meaning to cover both male and female horses. As a consequence, another gender morpheme is needed to specify whether it is a male or female horse in modern Adur Niesu, namely, mu21pu33 ‘male horse’ and mu21mo21 ‘female horse’. In some cases, the masculine marker pu33 is voiced, such as in lɛ21bu33 ‘ox’, but the tone change rule still holds.

| 53 | 33 > 21/ _ pa55 | |||||||

| a | tʂhɨ33 | ‘dog’ | + | pa55 | → | tʂhɨ21pa55 | ‘male dog’ | |

| b | mu33 | ‘horse’ | + | pa55 | → | mu21pa55 | ‘male horse, horse’ | |

| 33 > 21/ _ pu33 | ||||||||

| c | fɛ33 | ‘mouse’ | + | pu33 | → | fɛ21pu33 | ‘male mouse’ | |

| d | mu33 | ‘horse’ | + | pu33 | → | mu21pu33 | ‘male horse’ | |

| e | ʂu33 | ‘pheasant’ | + | pu33 | → | ʂu21pu33 | ‘male pheasant’ | |

| f | fa33 | ‘golden pheasant’ | + | pu33 | → | fa21pu33 | ‘male golden pheasant’ | |

| g | tʂhɨ33 | ‘dog’ | + | pu33 | → | tʂhɨ21pu33(tʂhɨ21mo21) | ‘male dog (and female dog)’ | |

However, if the preceding syllable bears the 55 tone, it will not be lowered due to the masculine syllable, for example, tʂhɨ55bu33 ‘male goat’ and vi55pa55 ‘female pig’.

4.4.3. Tone 33 > 21/_ mo21

This tone change occurs if the preceding syllable bearing tone 33 is followed by the feminine morpheme mo21, a reflex of Proto-Loloish *ʔəC-ma³ ‘mother’ (Bradley 1979). Like many Tibeto–Burman languages, Adur Niesu mo21 can also function as an augmentative morpheme (see Matisoff 1992). This rule of tone change is effective if mo21 is used for two functions, i.e., a feminine marker and an augmentative marker, regardless of the animacy of the word. If the preceding syllable does not bear tone 33, this tone change does not apply, such as vi55mo21 (pig:female) ‘female pig’ and tɕi55mo21 (eagle:female) ‘female eagle’.

| 54 | a | mu33 | ‘horse’ | + | mo21 | → | mu21mo21 | ‘female horse’ |

| b | ʑo33 | ‘sheep’ | + | mo21 | → | ʑo21mo21 | ‘female sheep’ | |

| c | lɯ33 | ‘cow’ | + | mo21 | → | lɯ21mo21 | ‘female cow’ | |

| d | ɣo33 | ‘bear’ | + | mo21 | → | ɣo21mo21 | ‘female bear’ | |

| e | tha33 | ‘jar’ | + | mo21 | → | tha21mo21 | ‘big jar’ | |

| f | ʐɨ33 | ‘water’ | + | mo21 | → | ʐɨ21mo21 | ‘big river’ | |

| g | bo33 | ‘mountain’ | + | mo21 | → | bo21mo21 | ‘big mountain’ | |

| h | pi33 | ‘priest’ | + | mo21 | → | pi21mo21 | ‘big (highly experienced) priest’ |

Similar to the masculine marker pa55 in mu21pa55 which covers both male and female horse as a general term, mo21 can also be lexicalized with its feminine meaning being implicit, such as dʑɯ²¹mo²¹ ‘bee, queen bee’. But this rule of tone change still holds because of the feminine marker.

However, this tone change does not apply to other meanings derived from mo²¹. In Adur Niesu, besides ‘female’ and ‘big’, mo²¹ can also function as a nominal meaning ‘woman’ and ‘master’, such as nɛ33mo21 (black Yi:woman) ‘the women of the Black Yi (the historical noble class)’, ma55mo21 (teach:master) ‘teacher’, and a postposed modifier meaning ‘old’, such as tsho33mo44 (people:old) ‘old people’ and ɣo33mo44 (bear:old) ‘(old) bear’. This tone change does not apply to the above three meanings. Note the contrast between pi33mo44 ‘priest’ and pi21mo21 ‘big (highly experienced) priest’. The former is a general term and also the title to refer to a Yi priest, and the latter is only used for priests with experiences and achievements. For example, while dʑɯ33khɯ33pi33mo44 means simply ‘Priest Jike’, pi21mo21dʑɯ33khɯ33 is a nominal–nominal phrase, meaning ‘Jike, the highly experienced and accomplished priest’. Additionally, this rule of tone change serves as a criterion to distinguish two confusing meanings in Adur Niesu, namely, ‘old’ and ‘big’. In many languages of the world, ‘old’ and ‘big’ can be colexified (Rzymski et al. 2019). If this tone change occurs in compound words, the meaning is not ‘old’, but ‘big’, for example, sɨ̠21mo21 ‘big tree’. To express ‘old tree’, a phrase is needed, namely, sɨ̠33 a33mo21 (tree old) ‘old tree’.

4.4.4. Tone 33 > 21/_ ȵi55

This rule of tone change occurs in the semantic environment of dual marking, with the plural pronouns compounded with the dual morpheme ȵi55.

| 55 | a | thu33 | ‘they’ | + | ȵi55 | → | thu21ȵi55 | ‘the two of them’ |

| b | no33 | ‘you (pl)’ | + | ȵi55 | → | no21ȵi55 | ‘the two of you’ | |

| c | ŋo33 | ‘we (exclusive)’ | + | ȵi55 | → | ŋo21ȵi55 | ‘the two of us (exclusive)’ |

It should be noted that the dual marker ȵi55 is derived from, but different from, the cardinal word ȵi21 ‘two’. This can be proved by the evidence from a33sɨ55ȵi55 (1pl.inclusive dual) ‘the two of us (inclusive)’ where, without tone 33 on the preceding syllable, the dual marker still bears tone 55, not tone 21. Otherwise, ȵi21 will be considered to colexify ‘dual’ and ‘two’, which is an unlikely proposal for Adur Niesu.

4.4.5. Tone 33 > 44/ ha21 _

This tone change occurs in interrogatives of quantity, such as ‘how many’ and ‘how long’. The interrogative words are compounds, formed by the interrogative morpheme ha21 and the adjectival roots; see Table 16. Both ha21 and the adjectival roots are bound morphemes, and cannot be used as full words. This tone change is also found in Nuosu; see Table 16.

Table 16.

Adur Niesu and Nuosu interrogatives of quantity.

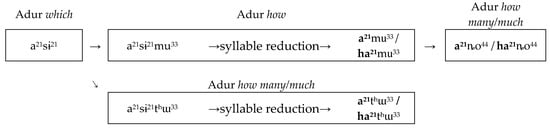

Adur Niesu ha21 should follow the derivational chain from the category of selection a21sɨ21 ‘which’ to the category of manner ha21mu33 (how:do) ‘how’.

First, typologically, the derivational direction from the interrogative category of selection to that of manner is attested, not the other way around (see Hölzl 2018, p. 83). Second, Adur Niesu ha21 ‘how’ and a21sɨ21 ‘which’ are closely related; the former should be a form after syllable reduction of the latter. After the syllable reduction of sɨ from a21sɨ21, a fricative glottal /h/ can often be epenthesized, such as ha21ʐɨ44 / a21ʐɨ44 ‘how big?’ and ha21ȵo44 / a21ȵo44 ‘how many?’. The epenthesized form now becomes the dominant form of this morpheme. A similar epenthesis is shown in (36).

Adur Niesu ha21 can be interchangeably pronounced as a21sɨ21 as in a21sɨ21mu33 / ha21mu33 (how:do) ‘how’ and as a21sɨ21thɯ33 / ha21thɯ33 (which:time) ‘when’. Therefore, a21sɨ21 means both ‘which’ and ‘how’ in Adur Niesu. Treating a21sɨ21 as the how form in Adur Niesu is attested by PL *ʔəs (Bradley 1979, p. 334). The Nuosu khɯ21 should be a reflex of the Proto-TB *ka (Matisoff 2003). Unlike Adur Niesu, Nuosu khɯ21 has lost its etymological connection with its modern which word ɕi44 (Shynra) and ɕa42 (Yynuo). The possible reason is that, at a certain historical moment, there used to be two which words in Nuosu: the canonical which lexeme, cognate of the Proto-TB *ka, and an innovation derived from other interrogatives (e.g., where and what). Gradually, the innovative form replaced the old which lexeme (Ding 2022).

Functioning as the interrogative category of selection, or ‘which’, a21sɨ21 is an adjective, placed after the head noun, such as tsho33 a21sɨ21 ma33 (people, which clf) ‘which person’. Due to its being used for another function, namely, the interrogative of manner, the which word a21sɨ21 has changed its adjectival word class, and is used as an adverb in the how word, placed before verbs, namely, a21sɨ21mu33 (how:do) or ha21mu33 (how:do) ‘how’. As a consequence, after the functional change, it is no longer acceptable to pronounce ha21ȵo44 ‘how many/much’ as *a21sɨ21ȵo44 or a21sɨ21 ma33 ‘which one’ as *ha21 ma33 in Adur Niesu. The irreversibility between ha21 and a21sɨ21 in the selection interrogative and the quantity interrogative suggests that ha21 has become a different morpheme with different word class and different function from a21sɨ21 ‘which’, although it is derived from the which morpheme. The derivational path in Adur Niesu is proposed as below (see Figure 7 and also Ding 2022).

Figure 7.

The derivation of Adur Niesu which, how, and related categories.

4.5. Tone Change in Prefixed Words

Tone change occurs to the prefixes a33- and i33-, which are used in the formation of property-denoting words, kinship terms, and animal words.

4.5.1. Tone 33 > 44/ _ 33 in Dimensional Words

This tone change is most popular in a33-/i33- prefixed property-denoting words in Adur Niesu.

The words in Table 17 are called stative verbs of dimensional extentives in Bradley (1995). In modern Adur Niesu, the positive dimensional words are prefixed by a33-, and the negative ones are prefixed by i33-, both sharing the same root. This derivational pattern is not productive in modern Nuosu and Niesu. However, historically, the positive and negative forms may have different roots, such as Nuosu a44lɨ33 ‘heavy’ and ʑo44so33 ‘light’, and Adur Niesu a44ʐɨ33 ‘big’ and ɛ55ʦɨ33 ‘small’. According to Bradley (1995), the historical development is that the original negative dimensional words were replaced by forms that have the prefix i33- plus the positive dimensional words. The negative dimensional word ‘small’ in the big/small pair has persisted and has not been replaced by the i33-prefixed positive form in Nuosu and Niesu in Table 17. In the cases of ‘heavy/light’, while the replacement of the negative extentive forms by the positive forms occurs in Adur Niesu, the negative forms ʑo44so33 (Shynra Nuosu), or i33so33 (Yynuo Nuosu) ‘light’, have survived. But a different prefix ʑo33-, rather than i33-, is added to so33 ‘light’ in Shynra Nuosu (see Ding 2022).

Table 17.

Adur Niesu dimensional words.

It can be observed that this tone change spreads to all dimensional extentives in Adur Niesu, but not in Nuosu.

4.5.2. Tone 33 > 44/ _ 33 in Kinship and Animal Words

This tone change is also related to the prefix a33- in other word formations besides the dimensional words. Although many of them have lost productivity, historically, it has several other semantic functions in Adur Niesu, including kinship terms, color words, and animal words. See Matisoff (2018) for a cross-linguistic study of Proto-Tibet–-Burman *a-prefix.

In modern Adur Niesu, this tone change only has certain productivity in kinship terms and animal names, besides the dimensional words. Given names of Adur Niesu are mostly bisyllabic, such as ga33ko33, a given name often for female. One of the syllables of the given name can be taken and prefixed by a33- to express endearment with this tone change, such as a44ko33.

| 56 | a | a-prefixed kinship terms | |

| a44bo33 | ‘father’s sister’ | ||

| a44ta33 | ‘father’ | ||

| a44phu33 | ‘grandfather’ | ||

| a44mo33 | ‘mother’ | ||

| b | a-prefixed endearment addresses | ||

| a44ko33 | often for female | ||

| a44si33 | often for female | ||

| a44ga33 | often for male | ||

| a44thi33 | often for male | ||

| a44ndza33 | both for female and male | ||

This rule of tone change still applies to a large number of animal words, with some exceptions (e.g., a33ɣo44 ‘bear’ and a21ɖʐa33 ‘sparrow’).

| 57 | a | a44ȵɛ 33 | ‘cat’ |

| b | a44fɛ33 | ‘mouse’ | |

| c | a44lɛ33 | ‘goat’ | |

| d | a44du33 | ‘fox’ | |

| e | a44ɬɨ33 | ‘pigeon’ | |

| f | a44dʑɯ33 | ‘raven’ | |

| g | a44ɣo33 | ‘hoopoe bird’ |

The a-prefix in color terms are lexicalized without any tone change, such as a33ni33 ‘red, be red’, a33thu33 ‘white, be white’, a33nɛ33 ‘black, be black’, and a33ʂɨ33 ‘yellow, be yellow’. If the tone change rules apply, the meanings will be changed. For example, the consultants indicate that a44thu33, with the tone of the prefix raised to 44, means ‘thick (e.g., book)’ (see Table 17), but not ‘white, be white’ anymore.

4.6. Tone Change in Patient Marking

There are three rules of tone change about patient marking, which are discussed together: patient33 > 44 / _ 33; patient33 > 21 / _ ko33; 21 > 44 / patient33_.

Since Adur Niesu is SOV, if there is only one argument in the clause, it could be agent or patient. In some cases, the default context is clear to tell the meaning, such as xɯ33dzɯ33 (meat eat) ‘to eat the meat’ as a non-reversible event. However, in many cases, ambiguity emerges. To disambiguate, other than the contexts, there are two main means to mark the patient of the clause.

First, the tone change of patient33 > 44 / _ 33 is addressed. This tone change is on the patient. The argument is mostly monosyllabic personal pronouns before the main verb. The patient will change from tone 33 to tone 44. This strategy is often used when the main verb bears tone 33.

| 58 | nɯ33 | hi21 | ŋo44 | kɯ33. |

| 2sg | say | 1pl | make listen | |

| ‘You tell us (of it).’ | ||||

| 59 | i33 | ŋa44 | ɣɯ33=a21=da33. |

| sg.log | 1sg | win=neg=sp | |

| ‘He/she cannot win over me.’ | |||

Compare (60a) and (60b). With the tone change, the ambiguity in (60a) can be eliminated in (60b). Despite the ambiguity in (60a), it will often be understood, without the tone change, as a resultative construction ‘someone stole his (belongings)’ in Adur Niesu, where the patient is placed sentence initially as the topic and the rest the comment.3 Due to the analytic morphology of Adur Niesu, there is the possibility that this tone change is caused by some floating tone marking patient. However, since we do not have any supporting evidence, it is synchronically an issue of tone change.

| 60 | a | tshɨ33 | tsho33 | khu33. |

| 3sg | people | steal | ||

| ‘Someone stole his (belongings).’ or ‘he stole someone’s (belongings).’ | ||||

| b | tshɨ33 | tsho44 | khu33. | |

| 3sg | people.p | steal | ||

| ‘He stole someone’s (belongings).’ | ||||

| c | tshɨ33 | tsho21=ko33 | khu33. | |

| 3sg | people=dom | steal | ||

| ‘He stole someone’s (belongings).’ | ||||

If the monosyllabic arguments are replaced by polysyllabic ones, the tone change cannot apply. To disambiguate (61a), an analytic means by differential object marker ko33 is used to mark the patient; see (61b). Similarly, since there is the way to disambiguate, (61a), without the marking, it will often be understood as ‘dʑɛ21nɛ33 stole su̠33ga55′s (belongings)’.

| 61 | a | su̠33ga55 | dʑɛ21nɛ33 | khu33. |

| surname | surname | steal | ||

| ‘dʑɛ21nɛ33 stole su̠33ga55′s (belongings).’ or ‘su̠33ga55 stole dʑɛ21nɛ33′s (belongings).’ | ||||

| b | su̠33ga55 | dʑɛ21nɛ33=ko33 | khu33. | |

| surname | surname=dom | steal | ||

| ‘su̠33ga55 stole dʑɛ21nɛ33′s (belongings).’ | ||||

The differential object marker (DOM) can also be used with monosyllabic patients for disambiguation; see (60c). In this case, the tone change rule of patient33 > 21 / _ ko33 is applied. The citation tone 33 of the person pronoun will be lowered to tone 21; see (62). The tone lowering or dissimilation before the DOM occurs regardless of the tonal value of the main verb.

| 62 | a | tshɨ33 | tsho33 | si55. | |

| 3sg | people | kill | |||

| ‘Someone killed him.’ or ‘He killed someone’ | |||||

| b | tshɨ33 | tsho21=ko33 | si55. | ||

| 3sg | people=dom | kill | |||

| ‘He killed someone.’ | |||||

| c | tshɨ33 | tsho33 | vi55. | ||

| 3sg | people | carry on shoulder | |||

| ‘Someone shouldered him.’ or ‘He shouldered someone’ | |||||

| d | tshɨ33 | tsho21=ko33 | vi55. | ||

| 3sg | people=dom | carry on shoulder | |||

| ‘He shouldered someone.’ | |||||

| e | xo33thi55ɬa21ba33 | ʦhɨ21=ko33 | a21=hi21. | ||

| name | 3sg=dom | neg=say | |||

| ‘Hotihlabba ignored him.’ | |||||

| f | nɯ33 | ŋa21=ko33 | phu44 | la33. | |

| 2sg | 1sg=dom | save | come | ||

| ‘You come to save me.’ | |||||

While the above two rules of tone change apply to the argument, the tone change 21 > 44 / patient33_ applies to the main verb; see Table 18.

Table 18.

Adur Niesu argument marking through tone.

Specifically, if the main verb bears tone 21, to mark the patient, the original tone 21 of the main verb will be raised to tone 44, suggesting the preceding argument is the patient of the verb, no longer the agent. In (63a), the citation form ‘to find, search’ in Adur Niesu is ʂɯ21. If it is changed to tone 44, the preceding pronoun becomes the patient; see (63b). It is also acceptable to use the DOM in (63c) with the patient changing its tone to 21. Please note that tonal rising for patient marking does not occur to the main verb bearing tone 33, such as ku33 ‘to steal’, and such a sentence is not acceptable, i.e., *tshɨ33 tsho33 khu44 (3sg people steal, intended meaning: ‘he stole someone’s belongings’).

| 63 | a | ŋa33 | ʂɯ21 | o44. |

| 1sg | find | pfv | ||

| ‘I searched (, but in vain).’ | ||||

| b | tshɨ33 | ŋa33 | ʂɯ44. | |

| 3sg | 1sg | find | ||

| ‘He (is) looking for me.’ | ||||

| c | tshɨ33 | ŋa21=ko33 | ʂɯ44. | |

| 3sg | 1sg=dom | find | ||

| ‘He (is) looking for me.’ | ||||

The following pairs are only contrastive in the tone of the verb. If the original tone 21 is changed to 44, the meaning is also changed; see (64) to (66).

| 64 | a | tsho33 | ndu21=ʂɨ33 | ŋu33. |

| people | beat=nmlz | cop | ||

| ‘(This wound) is (caused) by (someone’s) beating.’ | ||||

| b | tsho33 | ndu44=ʂɨ33 | ŋu33. | |

| people | beat=nmlz | cop | ||

| ‘(This is) something (used) to beat people’ | ||||

| 65 | a | a44ta33 | pu21=nɯ44=ɕi44 | ʐɨ33 | kɯ33 | la33. |

| father | carry=impf=seq | water | throw | come | ||

| ‘Father carried (something) and threw into the water.’ | ||||||

| b | a44ta33 | pu44=nɯ44=ɕi44 | ʐɨ33 | kɯ33 | la33. | |

| father | carry=impf=seq | water | throw | come | ||

| ‘(Someone) carried the father and threw (him) into the water.’ | ||||||

| 66 | a | ŋa33 | bɨ21 | o44. |

| 1sg | give | pfv | ||

| ‘I gave (it to someone).’ | ||||

| b | ŋa33 | bɨ44 | o44. | |

| 1sg | give | pfv | ||

| ‘Something (was) given to me.’ | ||||

4.7. Tone Change in Reduplication for Interrogation

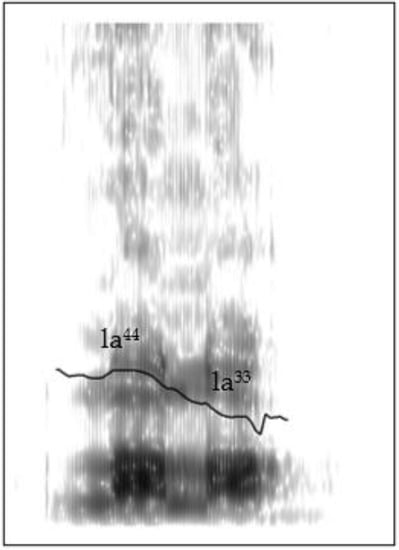

There are two rules for tone change to generate reduplication for yes–no interrogations: 33 > 44 / _ 33 and 21 > 33 / 21 _. It is clear that the two rules are consistently tone dissimilation, namely, adjacent same tones trigger dissimilation.

The first tone change, namely, 33 > 44 / _ 33, is productive in reduplicating monosyllabic verbs for yes–no questions; see (67). The first monosyllabic verb with tone 33 will rise to tone 44. See Figure 8 for the tone change.

| 67 | a | zɨ33 | + | zɨ33 | → | zɨ44~zɨ33 | ‘to buy or not’ |

| b | ndo33 | + | ndo33 | → | ndo44~ndo33 | ‘to drink or not’ | |

| c | la33 | + | la33 | → | la44~la33 | ‘to come or not’ | |

| d | tɕo33 | + | tɕo33 | → | tɕo44~tɕo33 | ‘to turn or not’ |

Figure 8.

The tone change with monosyllabic verb la33 ‘come’.

The tone change rule is not applicable to disyllabic or multisyllabic verbs for interrogative. Therefore, it serves as a criterion to distinguish words and phrases in Adur Niesu. While (68a) and (68b) are verbs without the tone change, (68c) and (68d) are verb phrases with the tone change.

| 68 | a | ɬɛ33phɔ33 | ‘to fight back’ | + | phɔ33 | → | ɬɛ33phɔ33~phɔ33 | ‘to fight back or not’ |

| b | hi33tɕhi33 | ‘to fall down’ | + | tɕhi33 | → | hi33tɕhi33~tɕhi33 | ‘to fall down or not’ | |

| c | ʐɨ33ndo33 | ‘to drink water’ | + | ndo33 | → | ʐɨ33ndo44~ndo33 | ‘to drink water or not’ | |

| d | dzɯ33tɕhi33 | ‘want eat (something)’ | + | tɕhi33 | → | dzɯ33tɕhi44~tɕhi33 | ‘to want or not want to eat’ |

Another rule of tone change found in interrogations, namely, 21 > 33 / 21 _, differs from 33 > 44 / _ 33 in that it occurs in both word and phrase. For example, (69h) and (69i) are words and (69j) is a phrase; the tone change 21 > 33 / 21 _ is still applicable.

| 69 | a | hi21 ‘to say’ | + | hi21 | → | hi21~ hi33 | ‘to say or not’ |

| b | ʂɯ21 ‘to find’ | + | ʂɯ21 | → | ʂɯ21~ʂɯ33 | ‘to find or not’ | |

| c | vu21 ‘to sell’ | + | vu21 | → | vu21~vu33 | ‘to sell or not’ | |

| d | gɯ21 ‘to play’ | + | gɯ21 | → | gɯ21~gɯ33 | ‘to play or not’ | |

| e | su21 ‘to resemble’ | + | su21 | → | su21~su33 | ‘to resemble or not’ | |

| f | ndu21 ‘to hit’ | + | ndu21 | → | ndu21~ndu33 | ‘to hit or not’ | |

| g | ŋo21 ‘to think’ | + | ŋo21 | → | ŋo21~ŋo33 | ‘to think or not’ | |

| h | a33go21 ‘empty’ | + | go21 | → | a33go21~go33 | ‘be empty or not’ | |

| i | mo33ŋgo21 ‘to undo the curse’ | + | ŋgo21 | → | mo33ŋgo21~ŋgo33 | ‘to undo the curse or not’ | |

| j | xɯ33vu21 ‘to sell the meat’ | + | vu21 | → | xɯ33vu21~vu33 | ‘to sell the meat or not’ |

As was discussed in Section 3.6, on the surface, there seems to be a third rule of tone change regarding reduplication for interrogation: 55 > 21 / 55 _. However, the tone lowering from 55 to 21 is not a tone change, but the result of the floating tone associated with the interrogative particle a21 after syllable reduction.

4.8. Effect of Floating Tone

Finally, the effect of the floating tone is discussed. On the surface, it appears to be a kind of tonal alternation. However, different from tone sandhi and tone change, it is the effect of the tone of an additional syllable after syllable reduction, such as tone 21 left after the reduced interrogative particle a21 in Section 3.6.

Another case of floating tone is about tone 21 in Adur Niesu possessive pronouns. Tone 21 was originally borne by the Proto-Nuosu proper genitive marker *ni21. This genitive marker is reduced in Adur Niesu and Nuosu, but still kept in Yynuo Nuosu as ni42, such as a33phu33=ni42 thɯ42ʑɨ33 (grandfather=gen book) ‘grandfather’s book’. Lama (2022) reports the tonal change from Proto-Nuosu proper 21 to modern Yynuo Nuosu 42.

Therefore, the genitive marker overrides its floating tone to Adur Niesu plain personal pronouns, e.g., ŋa33 + *ni21 → ŋa21 ‘my’. Take the noun phrases of locational description for example, modified by the possessive pronouns. Adur Niesu locational concepts are mainly expressed through nouns, such as ɖʐɨ21 ‘lower part’ and ŋi33 ‘front’. Most examples in (70) also experience tone dissimilation, namely, 21 > 44 / 21 _ in Section 4.3.

| 70 | a | tshɨ21 ‘his, her, its’ | + | ɖʐɨ21 ‘lower part’ | → | tshɨ21ɖʐɨ44 | ‘beneath him/her/it (lit. the part below him/her/it)’ |

| tshɨ21 ‘his, her, its’ | + | tɕo21 ‘direction’ | → | tshɨ21tɕo44 | ‘to him/her/it (lit. his/her/its direction)’ | ||

| tshɨ21 ‘his, her, its’ | + | ŋi33 ‘front’ | → | tshɨ21ŋi33 | ‘in front of him/her/it (lit. his/her/its front)’ | ||

| b | ŋa21 ‘my’ | + | ɖʐɨ21 ‘lower part’ | → | ŋa21ɖʐɨ44 | ‘beneath me (lit. the part below me)’ | |

| ŋa21 ‘my’ | + | tɕo21 ‘direction’ | → | ŋa21tɕo44 | ‘to me (lit. my direction)’ | ||