Abstract

Our purpose is to trace and explain theoretical and practical developments in foreign/world language teaching over the last decade or more. Language teaching in its modern form, from the Reform Movement of the late 19th century, has focused upon the need for learners to learn or acquire a foreign language in order to use it for communication. Other purposes involve language learning as an intellectual exercise, the development of a language faculty, and opening (young) people’s eyes to new worlds by introducing them to other countries. Here, we argue that these purposes are reasonable and enriching, but only if they are combined. We suggest that, by taking a humanistic perspective, language teaching can go beyond communication as a dominant purpose. This humanistic perspective is realised through two complementary developments. One is to emphasise that learners are members of various communities, including their local community, their national community, and a world community. The second is to pay attention to the fact that learners bring to the classroom their concerns and fears, especially in times of crisis. Language teachers, who are not only instructors in skills but educators of the whole person, should respond to their learners’ needs both as denizens of their society and as unique individuals. We first explain the theoretical framework and how it has evolved and then describe two experimental projects, one which focuses on the societal needs and one which adds to this a response to the affective needs of learners. We finally discuss how a recent controversy might be addressed in the language teaching class.

1. Introduction

Our starting point in this article is the premise that language teachers have responsibilities as educators that extend beyond the teaching of linguistic competence and communication skills—the usual goals of language teaching in many contexts in schools and universities. These responsibilities emerge from a humanist philosophy of education that fosters not only the development of students as individuals but also the development of societies as peaceful, democratic, sustainable, and just. This position was formulated through intercultural citizenship theory and pedagogy (Byram 2008; Byram et al. 2017), which suggest that language teaching for linguistic and intercultural development can be complemented with citizenship goals, for instance, by encouraging students to address issues of social significance as they are learning a language.

A further and more recent step in the argument is that language teachers can deal with ‘controversial’ and ‘cognitively and emotionally unsettling’ issues, as illustrated, for example, by the sensitive Qatar World Cup in 2022 and the controversy surrounding LGBTQ+ rights and human rights violations with migrant workers, among others. We suggest that language teachers can bring novel perspectives to the curriculum, since in foreign/world language education, the languages taught introduce a number of ‘other’ perspectives because they give access to other standpoints not available through the mother tongue: worldviews, cultural matters, sociocultural contexts, legal frameworks, and so on. Intercultural citizenship theory can contribute to the theoretical framework that justifies the tackling of such sensitive issues in language teaching, and intercultural citizenship pedagogy can contribute ways in which this goal can be productively addressed in the language classroom.

In the following, we describe intercultural citizenship theory and its articulation with controversial and sensitive themes in the language classroom. We demonstrate how this theory works in practice by using the example of the 1978 World Cup virtual project carried out in 2013 between Argentinian and British language students who addressed the topic of the last military dictatorship in Argentina in the context of the 1978 Football World Cup. Through specific stages, the project guided the students into exploring how the World Cup was used to cover over human rights violations involving the torture, kidnapping, and killing of civilians suspected of being against the military regime. In this project, the students were encouraged to learn from a historical event (the dictatorship) and a sporting event (the 1978 World Cup) in their foreign language classrooms to inform and transform their present and the future. The students created artwork (leaflets, posters, videos) intended to raise awareness in their society about human rights violations during the 1978 World Cup, and they acted in their community with this aim in mind, for instance, by delivering talks, contributing material from the project to a local museum, interviewing a parent whose son had been made to ‘disappear’ during the dictatorship, and so on. In a second example, we show how a further dimension was added to the theory: the inclusion of attention to students’ emotional responses to a theme they would pursue, i.e., a project about the COVID-19 pandemic they were experiencing at the time. After describing the theory and the pedagogic projects that enact the theory, we draw implications and connections with the 2022 Qatar World Cup as a unique opportunity for language teachers to realise their responsibilities as educators beyond their instrumental role of teachers of language.

2. Theoretical Framework

With the benefit of hindsight and for the sake of clarity, we can present the development of the framework in a number of stages, although these were not clear-cut at the time (Byram et al. 2020).

The first stage was related to the purposes of communication in language teaching. The development, over a period of ten years during the 1990s, of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (Council of Europe 2001) included attention to the fact that learners need not only linguistic competences but also ‘social competences’ if they are to interact with people of other countries and cultures. Initially this was understood as a matter of acquiring social competences which are comparable with those of a native speaker of the language being learned. The argument was then made that this is neither appropriate nor feasible and that it is more important that learners be able to see and understand relationships between countries and between cultures—whether in other countries or their own—as this is the context in which they might interact with native speakers. They needed to become ‘intercultural speakers’, people who have linguistic competence and ‘intercultural competence’ (Byram and Zarate 1996).

In further developing the notion of intercultural competence as one of the purposes of language teaching within general education—with attention to learners as human beings and not just masters of skills—it was argued that intercultural competence should also include the ability to reflect upon and critique the cultures of social groups, large or small, including not only other people’s groups but also learners’ own groups (Byram 1997). Intercultural competence taught in foreign language classrooms tends to focus upon social groups in other countries and their cultures but can also be complemented by teaching across the curriculum which focuses upon social groups in learners’ own countries, who may or may not speak a different language (Wagner et al. 2019). The notion of ‘critical cultural awareness’ was coined in order to emphasise the significance of critical thinking and draw upon work on politische Bildung (literally ‘political education’) in Germany (Byram 1997).

The second significant stage was also influenced by the theory of politische Bildung and took the notion that politische Bildung can and should encourage young people to be active in their community more seriously. They are members of a community, even before they have voting and similar rights, and should participate in the life of a community, whether local, national, or international (Byram 2008). It is the third level of community activity which can be, so it was argued, particularly appropriate when encouraged and developed in foreign language teaching. Foreign language teaching looks outwards beyond learners’ own countries and nationalities, whereas much education for citizenship in other parts of the curriculum emphasises the evolution of young people as members of a national community, their national citizenship. This second stage of work thus combined insights from teaching intercultural competence and teaching citizenship, taking it beyond national citizenship. The term ‘intercultural citizenship’ was coined in order to highlight the origins and evolution of the theory.

There have been critiques of this term, because ‘intercultural’ may be interpreted as a matter of interaction only between people of two different cultures, although this is not necessarily the case. Examples, such as the ones we give below, where people from two countries and cultures are involved, are simply examples; projects involving more than two groups of learners might also develop intercultural citizenship. A second critique, especially present in debates in Germany, argues that the notion of interculturality suggests that there are hard borders between countries and cultures and does not reflect the reality of the contemporary world (Guntersdorfer 2019). The projects which we describe below emphasise the evolution of new transcultural identifications with international/transnational groups working together to solve issues which are beyond the national scope.

In the last decade or more, there have been a number of projects which have implemented the notion of intercultural citizenship in language classrooms (Byram et al. 2017). They have brought together learners in different countries working on issues of common concern and which they consider to be not just a local matter, not just a national matter, but international/transnational. They have dealt inter alia with environmental issues, where there seems to be no controversy about the need for young people to be involved in action in their communities, local or transnational. These projects have also proved that language classrooms are particularly well-placed environments to address controversial issues, as foreign languages can provide access to a multitude of perspectives on contentious and debatable topics, which are not readily available through the mother tongue. Foreign languages provide learners with a powerful tool to engage in intercultural dialogue for the promotion of multiperspectivity, the respect for opposing views and tolerance of ambiguity (Kubota 2014; Hess 2009; Hess and McAvoy 2015; Pace 2021).

As to what may be considered controversial, Yacek (2018, p. 73) stated that ‘one of the greatest challenges of teaching controversial issues is deciding which controversies one should teach in the first place. What counts as a controversy is itself controversial’. Yacek further postulated that we should simply ‘let society decide. That is, if there is controversy over an issue in the public sphere, then the teacher should consider the issue controversial’ (ibid.). One such controversial issue was the COVID-19 pandemic. The decision to work on this controversy led to a third stage in the development of the theoretical framework.

What made this different from earlier projects dealing with controversial issues was that learners were contemporaneously involved—earlier projects dealt with historical events—and subject to the traumatic effects which they could also observe in their local communities. Bringing learners from two countries and cultures together with the aim that they should be active in their own communities had to be combined with further aims of helping them to deal with their trauma.

In a way similar to when the theoretical framework drew on work from German political education, this third stage of development turned to ‘pedagogies of discomfort’. Pedagogies of discomfort—in the plural because there are more than one—help teachers to deal with the emotional responses of their learners to events in the world beyond the classroom, such as apartheid, genocide, and human rights abuses. It is argued that there is a role for pedagogy as well as therapy and that pedagogy can include arts-based approaches and—in continuation of intercultural citizenship projects—interactions with learners from other countries and cultures. This is illustrated below by a brief description of a project which took place during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Each of the stages of evolution of this framework embody a view of education as both instrumental and humanistic, i.e., education which draws out the potential of the individual and education which leads (young) people towards a better understanding of themselves and society. What is sometimes seen as a dichotomy is for us a complementarity, although we have sometimes seen the need to stress the humanistic element because of the way in which the instrumental element dominates in much of contemporary education policy-making, in language teaching and beyond.

The 1978 Football World Cup in Argentina during a Dictatorship Period

In this section, we illustrate intercultural citizenship theory and pedagogy work in practice with two projects. One is a pedagogical intervention with university language students on the topic of the 1978 Football World Cup, hosted in Argentina. The sporting event was used to hide human rights abuses at the time of a military dictatorship (1976–1983) and to mask the crimes committed by the Military Junta to eliminate political dissent. These crimes included abductions, killings, torture, and ‘disappearances’. Zembylas (2013, p. 177) referred to knowledge of this kind as ‘troubled’, i.e., knowledge that often leads to trauma due to feelings of loss, shame, anger, pain, and grief. The pedagogical intervention was a Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) project involving language students from two universities—one from Argentina and the other one from the UK—who addressed this theme in their classrooms and dealt with this troubled knowledge. The students were all doing their first degree, studying English and Spanish as foreign languages (for details of this virtual intercultural citizenship project, see Porto and Byram 2015; Porto 2019; Porto and Yulita 2019; Yulita and Porto 2017). Informed written consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study to use their work anonymously and is described below.

In addition to the usual linguistic and intercultural aims that characterise intercultural language teaching, there were citizenship goals, associated with the second and third stages of development of the theory as described above, i.e., students were involved in action in the community and controversial themes were addressed. We aimed to address pedagogically students’ ‘troubled knowledge’ about the dictatorship and their discomforting feelings, such as grief, pain, resentment, revenge or despair, in order to create openings for individual and social transformation. This transformation allowed students to make small contributions to the development of peaceful, just, and democratic societies. This is the essence of pedagogies of discomfort (Boler 1999; Boler and Zembylas 2003; Zembylas and McGlynn 2012) in which emotions play a central role.

The project was carried out in 2013 and had four stages: introductory, awareness-raising, dialogue, and citizenship. All stages had a reflection element. The students were told to use English and Spanish, the foreign languages they were learning in Argentina and the UK respectively, on alternate days. In the introductory stage, the students researched the dictatorship and the World Cup in their respective foreign language classrooms, without interacting with each other yet. They used a variety of sources, such as documentaries, magazines, films, songs, and newspapers. In the awareness-raising stage, they analysed the media representations of the dictatorship and the World Cup and reflected on how these influenced their feelings about, and perceptions of, people, places, and events. They also found other examples around the globe in which a sports event was used to hide human rights abuse, such as the 1934 World Cup in Italy, the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing, the 2012 Olympics in London, and the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi. In the dialogue stage, the students interacted in mixed nationality groups using Skype to discuss their opinions and discoveries. They designed a collaborative leaflet in English and Spanish intended to raise awareness in society today of human rights violations during the 1978 World Cup. In the final citizenship stage, they acted in their communities. Owing to restrictions at the British university, only the Argentinian students participated in this phase. In newly formed groups, they spread information gained during the project to family, friends, and passers-by in a local square; delivered talks in the university and in language schools; interviewed a 95-year-old man whose son had disappeared; and conducted other similar actions.

The students were challenged cognitively and emotionally. Cognitively, they made attempts to understand the historical period, becoming familiar with unknown facts and victims’ stories. For instance, a British student said, drawing our attention to their cognitive development: ‘I know some stuff [now] and I know there was a dictatorship and people under control…and people disappearing, people being killed’ (Skype conversation, emphasis added). Understanding the dictatorship was an intellectual challenge for all students. One Argentinian student said: ‘I’ve learned it [the dictatorship] had civilian support, which is a thing that you can’t really understand’ (Skype conversation, emphasis added). At the same time, learning about the dictatorship intellectually led to emotional engagement. The students expressed their horror of the period and described it as ‘creepy’, ‘scary’, ‘bloody’, ‘awful’, ‘terrible’, ‘creepiest’, ‘evil’, ‘perverse’, ‘fearful’, ‘tragic’, ‘violent’, ‘ugly’, and ‘horrifying’, words which are an indication that they were emotionally disturbed. On occasion, this engagement manifested itself physically: some students cried, others shivered, and others experienced goosebumps. One Argentinian student expressed, ‘Everything about this period usually really moves me and gives me goosebumps’ (Skype extract). These were the bodily experiences of the discomforting emotions triggered by their troubled knowledge of the dictatorship.

The leaflets that the Argentinian and British students created collaboratively in Spanish and English were intended to raise consciousness about the atrocities of the dictatorship in society in present times. One group created the following one (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Awareness-raising leaflet created by Argentinian and British students in collaboration.

With a critical perspective—based on the notion of ‘critical cultural awareness’ (Byram 1997) and Barnett’s analysis of the critical business of a university (Barnett 1997)—–this group introduced the two faces of Argentina at the time: happiness at winning the World Cup and murder and blood during the dictatorship. They used artistic means, for instance, pictures (the ball and the skull; the logo), colours (those of the Argentinian flag against a white background at the top and a black background at the bottom), and puns such as ‘Argentina 78’ and ‘Asesina [murderer] 78’.

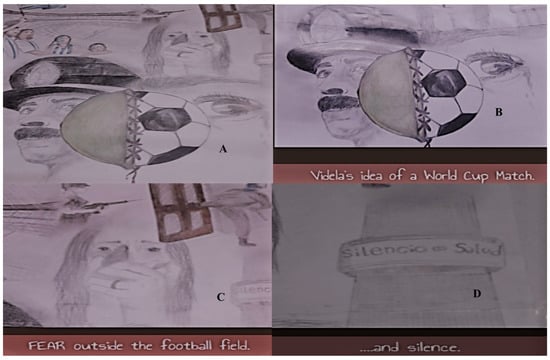

The students also engaged in community action. For example, one group of Argentinian students made a drawing addressing different aspects of the dictatorship (Figure 2A), such as the dictator Videla’s idea of a World Cup match (Figure 2B), the fear outside the football pitch (Figure 2C), and the idea of silence (Figure 2D). They donated their artistic creation to a local museum, and the museum later displayed it to visitors. In this way, the students re-signified the traumatic past as a way of dealing with the still-open wound and never-ending grief of society as a whole, manifested every March 24th on the Remembrance Day of the dictatorship. Their drawing became a cultural artefact that opened up possibilities for understanding the bleeding and grief of those times and transforming them to build a new future.

Figure 2.

Artistic creation to channel discomforting emotions.

Overall, we can say this project illustrates the second stage of development of the theory in that the teachers encouraged the students to engage in action in their community during their language learning. In retrospect, the project was also an opportunity for the students to channel the discomforting feelings they experienced in connection with the dictatorship, and this was then theorised in the third stage of the development of the framework (see Porto and Yulita 2019).

3. The COVID-19 Case

Our second example is a project on COVID-19 carried out in May 2020 at the onset of the pandemic between university students in Argentina and in the USA. The former were all Argentinian, Spanish-speaking, and preservice teachers of English taking an English language course. The latter were enrolled in an ‘Introduction to Intercultural Communication’ course, came from various disciplines (biological sciences, business technology administration, health administration and policy, information systems, media and communication studies, and psychology), and had diverse linguistic, cultural, and religious backgrounds.

This project also had four phases that also included elements of reflection. In the introductory stage, the students collected examples of artistic representations of COVID-19 from their country of origin (for instance, graffiti, drawings, photos, video clips) and analysed them. In the awareness-raising stage, they shared in their own group the examples they had collected and reflected on them, paying attention to the emotional effects of the pandemic. In the dialogue stage, working in mixed transnational groups and using English as a lingua franca, they collaboratively created artistic works intended not only to raise awareness in society about the dangers of the pandemic (second stage of the theory) but also to channel their discomforting feelings and emotions (third stage based on pedagogies of discomfort, Boler 1999; Boler and Zembylas 2003). Diverse languages (English, Farsi, Hindi, Italian, and Spanish) were used by the students to create various artistic artefacts as project outputs. For instance, there was a dramatisation of the pandemic on video, a collage of their drawings, and a photograph taken by a student who was an amateur photographer. In the citizenship stage, also called the action stage, they sought an outlet for their artwork beyond the virtual classroom, such as the launching of an awareness-raising campaign about the emotional dangers of the pandemic, a survey, a blog, and more (see Porto et al. 2021). They also wrote a ‘civic statement’ in which they reflected on the whole experience and described the aims and steps of their community action.

Here too, the students were cognitively and emotionally challenged, as in the dictatorship project. Cognitively, one group of students was, for instance, intrigued by how people in different roles felt and acted in the pandemic. They researched this perspective and created a TikTok video in which they impersonated a health worker, a person with COVID-19, an unemployed person, a student, and an old person. Emotionally, by impersonating these roles, they became increasingly aware of the harsh realities of these people.

Pedagogies of discomfort focused on students engaging with troubling knowledge but also transforming (channelling) their discomforting emotions (Zembylas and McGlynn 2012). One group created a collage (Figure 3A) intended to portray and channel their emotions about COVID-19. In their civic statement, they expressed, ‘the purpose of the artefact was to show how normal life has changed’. One student in the group designed a checklist of things one could not forget in May 2020, such as a mask (Figure 3B). Another drew a box with a door and a window (Figure 3C). This is how she interpreted her drawing:

Figure 3.

Emotional engagement through artistic work for transformation.

Door: ‘I tried to use a very ordinary object to communicate what I think the pandemic has affected our old lifestyle. The COVID-19 forced us to be indoors. Three months of social isolation have gone, and we are not sure when we will be able to leave our houses and remake our lives (…) In the frames of this door, which I metaphorically associated with the things that surround us, I included the negative feelings that are the ones that surface the most. When going down in the frame, what emerges is “HOPE”. This positive feeling that we all have, as we all want this pandemic to come to an end, is surpassed by the negative emotions. The window is the place from where we look to the outside; that place that seems to be very far away from our isolation perspective. Whenever we are ready to cross that door, we will for sure, need to be very much responsible (emphasis added)’.

The italicised expressions show the contrasting feelings triggered by the pandemic, negative (isolation, uncertainty) and positive (hope), and the need for individual and collective responsibility.

Another student in the same group expressed, ‘we have felt the same way so far (exhausted and overwhelmed)’ and drew a lotus flower (Figure 3D) which ‘represents rebirth and self-regeneration that people from all over the world will experience after the pandemic Covid, even ourselves (…) I included the lotus flower as a representation of us; we’ll be reborn and see the world from another point of view when the pandemic is over’. Her artistic expression (drawing) was a means through which she was hoping to transform exhaustion and discomfort into hope: ‘we can notice the Sun rising as a sign of hope and the beginning of a new era (without the virus) (…) there’s a representation of the COVID-19, which is hiding behind the sea, as it is finally leaving the Earth’ (extracts from civic statement).

Overall, this group acknowledged the centrality of emotions in their artistic artefact, as the italicised expressions indicate: ‘This [artistic] approach is not meant to convey a message that our audience has to understand, but to have others relate to the feelings it portrays and connect to it from an emotional perspective rather than a logical one’ (civic statement).

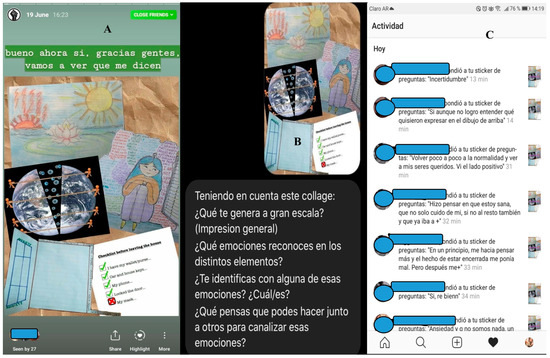

Finally, this group also took action. They used their collage in an Instagram story (Figure 4A,B) to foster the collective channelling of negative emotions and gather people’s reactions (Figure 4C) to some triggers they posed: ‘What does this collage provoke in you (general impression)? What emotions do you recognise in the different elements? Do you identify with any of these emotions? Which one(s)? What do you think you can do with others so as to channel these emotions?’ (Figure 4B, our translation).

Figure 4.

Action in the community to channel discomforting emotions (identifying information is covered to protect anonymity).

The project illustrates the second and third stages of development of the theoretical framework. The students not only engaged in community action; they were also guided to consciously pay attention to their emotions, usually discomforting feelings arising from a controversial theme such as COVID-19, and were encouraged to transform their negative feelings in order to make a contribution to society, in this case, help people (and themselves) to combat the dangers of the pandemic (see Porto et al. 2021).

4. Football World Cup in Qatar, 2022

We now turn to a recent event to illustrate our point of the value in selecting ‘troubled knowledge’ (Zembylas 2013, p. 177) in intercultural language teaching. The event is the Qatar World Cup. Our argument is based on the controversy surrounding LGBTQ+ rights and human rights violations against migrant workers, amongst others. We see the 2022 Qatar World Cup as a unique opportunity for language teachers to realise their responsibilities as educators beyond their instrumental role of teachers of language. What we propose here is an overview of the issues which could be the basis for a project by following the steps outlined in the descriptions of projects above.

The choice of the 2022 World Cup in Qatar as a suitable topic is two-fold: (i) it addresses human rights issues and (ii) deals with controversies which may potentially lead to contrary views and differing opinions. Based on these criteria, this topic is appropriate for discussion and debate in language learning and teaching for the development of intercultural competences necessary to realise the aims of democratic education (Barrett et al. 2018; Kauppi and Drerup 2021; Hess 2009; Hess and McAvoy 2015).

From the time that Qatar was awarded hosting rights in 2010, controversy and human rights violations dominated the media (Duval 2021; Kirschner 2019; The Guardian 2021; Amnesty International 2018, 2020, 2021). This was the first World Cup held in the Middle East, and from the moment of the award, Qatar, one of the richest countries in the world, embarked on an unprecedented building programme, including seven new stadiums, a new airport, roads, public transport systems, hotels, and a new city, which hosted the 2022 World Cup. Initial concerns as to how Qatar, with little footballing tradition, had managed to secure enough votes from the FIFA (Fédération Internationale de Football Association) executive, who decides such matters, led to accusations of bribery and corruption. These were widely investigated, even involving the FBI from the United States (The US Department of Justice 2015). Many members of the executive at the time have subsequently fallen foul of the authorities and no longer hold positions of power within FIFA. Nevertheless, the 2022 World Cup remained with Qatar.

As the tournament grew closer, many observers became more interested in other factors, such as the country’s human rights violations of migrant workers, homosexuality as a criminal act, xenophobic attitudes, and anti-Islamic bigotry. For example, The Guardian’s coverage of the Qatar 2022 World Cup regularly highlighted a wide range of abuses against migrant workers, from low wages to hazardous, inhuman conditions at World Cup construction sites. Repeated accusations of exploitation and deaths of these workers led to international football team demonstrations (BBC 2021; The Guardian 2022a) and academic research (Renkiewicz 2016; Amis 2017; Heerdt 2018). Reports claiming that more than 6500 migrant workers from India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka died in Qatar after 2010 (The Guardian 2021) led to public outrage. Government sources in those countries claimed that the total death toll was significantly higher, as the usually cited figures excluded deaths from countries which sent large numbers of workers to Qatar even before the World Cup, including the Philippines and Kenya. Deaths that occurred in the final months of 2020 were not included either. Amnesty International (2021) also claimed that thousands of young migrant workers died suddenly and unexpectedly in Qatar, with workers’ bereaved families being denied any compensation from their employers, as the Qatari authorities failed to properly investigate their deaths in a way that would make it possible to determine the underlying causes, which might have been work-related.

Systemic issues included power imbalances between employees and employers and extreme inequalities between a small Qatari local citizenry and a large majority of migrant workers who crossed national borders and entered the international public sphere due to the 2022 World Cup. Qatar’s ‘Sponsorship Law’, known as the kafala system, prevented migrant workers from leaving the country or switching employers without the consent of their sponsor. This system, often referred to as ‘modern slavery’, increased the risk of exploitation and abuse (Duval 2021; Heerdt 2018).

In addition to matters of employment, a further issue was raised. Under Qatari laws, sexual acts between people of the same sex are illegal and LGBTQ+ people may suffer from imprisonment and violence, facing the death penalty in some cases (Stonewall 2019). Both FIFA and Qatari officials made repeated pledges that the World Cup would be free of discrimination. However, The Guardian (2022c) reported that the safety of gay Qataris from physical torture was promised in exchange for information on other LGBTQ+ people in the country. Qatari officials complained that some of the accusations were racially motivated and said that there were double standards, especially from ‘countries in Europe that call themselves liberal democracies’ (Preussen 2022). In response to LGBTQ+ people’s reports of feeling unsafe travelling to the tournament, Qatari officials clarified that ‘everyone is welcome in Qatar’ and that ‘we simply ask for people to respect our culture’, explaining that any open display of affection, regardless of sexual orientation, is ‘frowned upon’ in their country (The Guardian 2022a). A former Qatar international footballer described homosexuality as ‘damage in the mind’, adding that visitors ’have to accept our rules here’ (La Nación 2022; The Guardian 2022a).

A different perspective to the general clamour in the western world was articulated by France’s goalkeeping captain Hugo Lloris, who hinted he disagreed with wearing a rainbow-coloured armband representing a campaign against discrimination during World Cup games in Qatar. ‘When we are in France, when we welcome foreigners, we often want them to follow our rules, to respect our culture, and I will do the same when I go to Qatar, quite simply,’ Lloris said. ‘I can agree or disagree with their ideas, but I have to show respect’ (The Guardian 2022b).

These, amongst other cognitively and emotionally challenging sensitive issues surrounding the 2022 World Cup, can afford opportunities for engaging students in democratic discussions and intercultural interactions with a view to realising the aims of intercultural citizenship theory. A project based on these events would follow the stages described earlier from awareness raising to students taking action in the ‘here and now’.

5. Conclusions

The inclusion of ‘troubled knowledge’ in teaching can affect learners’ emotional well-being, leading to discomforting feelings of loss, resentment, anger, grief, revenge, and despair. These emotions can be addressed pedagogically in ways that create openings for self and social transformation (Boler 1999, 2004; Boler and Zembylas 2003; Zembylas and McGlynn 2012; Zembylas 2015, 2017). Our empirical research contributes to an existing body of work that demonstrates that this approach can result in learners developing higher levels of care, compassion, respect, and solidarity, leading to social and civic engagement (Zembylas 2017; Zembylas and Bozalek 2017; Porto and Yulita 2019). The development and growth of learners as human beings and the belief that they have agency within the world is at the heart of intercultural citizenship education, and this article shows the importance of including controversial topics that address human rights issues in the language curriculum. As can be gleaned from the student-generated arts-based outputs in the 1978 World Cup and COVID-19 projects, the humanistic perspectives and practices presented in this article provide opportunities for learners to transform their discomforting emotions into positive actions in their communities. The theory of intercultural citizenship can thus be effectively combined with pedagogies of discomfort to offer learners a sense of repair, healing, and humanity in the face of trauma, whilst providing language teachers with a pedagogical framework for the integration of controversial issues in the curriculum.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B., M.P. and L.Y.; methodology, M.B., M.P. and L.Y.; software, M.B., M.P. and L.Y.; validation, M.B., M.P. and L.Y.; formal analysis, M.B., M.P. and L.Y.; investigation, M.B., M.P. and L.Y.X; resources, M.B., M.P. and L.Y.; data curation, M.B., M.P. and L.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B., M.P. and L.Y.; writing—review and editing, M.B., M.P. and L.Y.; visualization, M.B., M.P. and L.Y.; supervision, M.B., M.P. and L.Y.; project administration, M.B., M.P. and L.Y.; funding acquisition, M.B., M.P. and L.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Porto’s contribution to this study was funded by Project H922, Universidad Nacional de La Plata; and Grant PIP 11220210100512, National Research Council (CONICET), Argentina. Byram’s contribution to this study was financed by the European Union’s NextGenerationEU, through the National Recovery and Resilience Plan of the Republic of Bulgaria, project No BG-RRP-2.004-0008.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of East Anglia (dictatorship project) and the University of Maryland Baltimore County (COVID-19 project), and followed the ethical guidelines provided by Universidad Nacional de La Plata.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Due to restrictions at the participating universities, data are not available for disclosure.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Amis, Lucy. 2017. Mega-Sporting Events and Human Rights—A Time for More Teamwork? Business and Human Rights Journal 2: 135–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amnesty International. 2018. Qatar: Migrant Workers Unpaid for Months of Work by Company Linked to World Cup Host City. Available online: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2018/09/qatar-migrant-workers-unpaid-for-months-of-work-by-company-linked-to-world-cup/ (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Amnesty International. 2020. Qatar World Cup: The Ugly Side of the Beautiful Game. Available online: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/mde22/3548/2016/en/ (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Amnesty International. 2021. Qatar: “In the Prime of Their Lives”: Qatar’s Failure to Investigate, Remedy and Prevent Migrant Workers’ Deaths. Index Number: MDE 22/4614/2021. Available online: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/mde22/4614/2021/en/#:~:text=Qatar%3A%20%E2%80%9CIn%20the%20prime%20of,and%20prevent%20migrant%20workers’%20deaths&text=Over%20the%20last%20decade%2C%20thousands,before%20travelling%20to%20the%20country.l (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Barnett, Ronald. 1997. Higher Education: A Critical Business. London: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, Martyn, Luisa de Bivar Black, Micahel Byram, Jaroslav Faltýn, ars Gudmundson, Hilligje van’t Land, Claudia Lenz, Pascale Mompoint-Gaillard, Milica Popović, Călin Rus, and et al. 2018. Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing, vol. 3, Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/reference-framework-of-competences-for-democratic-culture/rfcdc-volumes (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- BBC. 2021. Germany Players Wear T-Shirts in Protest Against Qatar’s Human Rights Record. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/sport/football/56534835 (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Boler, Megan, and Michalinos Zembylas. 2003. Discomforting truths: The emotional terrain of understanding difference. In Pedagogies of Difference: Rethinking Education for Social Change. Edited by Peter Pericles Trifonas. New York: Routledge Falmer, pp. 110–36. [Google Scholar]

- Boler, Megan. 1999. Feeling Power: Emotions & Education. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Boler, Megan. 2004. Teaching for hope: The ethics of shattering world views. In Teaching, Learning and Loving: Reclaiming Passion in Educational Practice. Edited by Daniel P. Liston and James W. Garrison. New York: Routledge, pp. 117–31. [Google Scholar]

- Byram, Michael, and Genevieve Zarate. 1996. Defining and assessing intercultural competence: Some principles and proposals for the European context. Language Teaching 29: 239–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byram, Michael, Irina Golubeva, Han Hui, and Manuela Wagner, eds. 2017. From Principles to Practice in Education for Intercultural Citizenship. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Byram, Michael, Melina Porto, and Leticia Yulita. 2020. Education for intercultural citizenship. In The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Education. Edited by Sara Laviosa and Maria González-Davies. New York: Routledge, pp. 46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Byram, Michael. 1997. Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Communicative Competence. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Byram, Michael. 2008. From Foreign Language Education to Education for Intercultural Citizenship: Essays and Reflections. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. 2001. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Duval, Antoine. 2021. How Qatar’s migrant workers became FIFA’s Problem: A transnational struggle for responsibility. Transnational Legal Theory 12: 473–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guntersdorfer, Ivett Rita. 2019. From the multilingual to the intercultural in the current German political, academic and pedagogical discourse. Journal of Multicultural Discourses 14: 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerdt, Daniela. 2018. Winning at the World Cup: A matter of protecting human rights and sharing responsibilities. Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 36: 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, Diana E. 2009. Controversy in the Classroom: The Democratic Power of Discussion. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, Diana E., and Paula McAvoy. 2015. The Political Classroom. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kauppi, Veli-Mikko, and Johannes Drerup. 2021. Discussion and inquiry: A Deweyan perspective on teaching controversial issues. Theory and Research in Education 19: 213–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschner, Florian. 2019. Breakthrough or much ado about nothing? FIFA’s new bidding process in the light of best practice examples of human rights assessments under UNGP Framework. The International Sports Law Journal 19: 133–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, Ryuko. 2014. “We must look at both sides”—But a denial of genocide too? Difficult moments on controversial issues in the classroom. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies 11: 225–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Nación. 2022. Un Embajador de Qatar 2022 Provocó Escándalo al Hablar de la Homosexualidad. Available online: https://www.lanacion.com.ar/deportes/futbol/qatar-2022-hablo-un-embajador-del-mundial-y-dijo-que-la-homosexualidad-es-un-dano-mental-nid08112022/ (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Pace, Judith L. 2021. Hard Questions: Learning to Teach Controversial Issues. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Porto, Melina, and Leticia Yulita. 2019. Is there a place for forgiveness and discomforting pedagogies in the foreign language classroom in higher education? Cambridge Journal of Education 49: 477–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, Melina, and Michael Byram. 2015. A curriculum for action in the community and intercultural citizenship in higher education. Language, Culture and Curriculum 28: 226–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, Melina, Irina Golubeva, and Michael Byram. 2021. Channelling discomfort through the arts: A Covid-19 case study through an intercultural telecollaboration project. Language Teaching Research 27: 276–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, Melina. 2019. Does education for intercultural citizenship lead to language learning? Language, Culture and Curriculum 32: 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preussen, Wilhelmine. 2022. Qatar to Europe: You Sound Arrogant and Racist. Politico. November 7. Available online: https://www.politico.eu/article/sheikh-mohammed-bin-abdulrahman-qatar-foreign-minister-to-europe-you-are-arrogant-and-racist (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Renkiewicz, Paula. 2016. Sweat Makes the Green Grass Grow: The Precarious Future of Quatar’s Migrant Workers in the Run up to the 2022 FIFA World Cup Under the Kafala System and Recommendations for Effective Reform. American University Law Review 65: 721–61. Available online: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr/vol65/iss3/8 (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Stonewall. 2019. Stonewall Global Workplace Briefings: Qatar. Available online: https://www.stonewall.org.uk/system/files/global_workplace_briefing_qatar_final.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- The Guardian. 2021. Revealed: 6,500 Migrant Workers Have Died in Qatar Since World Cup Awarded. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/football/2022/nov/27/qatar-deaths-how-many-migrant-workers-died-world-cup-number-toll#:~:text=A%20Guardian%20analysis%20in%20February,occupation%20or%20place%20of%20work (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- The Guardian. 2022a. Qatar World Cup Ambassador Criticised for ‘Harmful’ Homosexuality Comments. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/football/2022/nov/08/qatar-world-cup-ambassador-homosexuality (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- The Guardian. 2022b. France Captain Lloris Suggests He Will Not Wear Rainbow Armband at World Cup. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/football/2022/nov/14/france-captain-hugo-lloris-suggests-he-will-not-wear-rainbow-armband-world-cup (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- The Guardian. 2022c. Gay Qataris Physically Abused Then Recruited as agents, Campaigner Says. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/football/2022/nov/15/gay-qataris-physically-abused-then-recruited-as-agents-campaigner-says (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- The US Department of Justice. 2015. Nine FIFA Officials and Five Corporate Executives Indicted for Racketeering Conspiracy and Corruption. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/nine-fifa-officials-and-five-corporate-executives-indicted-racketeering-conspiracy-and (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Wagner, Manuela, Fabiana Cardetti, and Michael Byram. 2019. Teaching Intercultural Citizenship Across the Curriculum. The Role of Language Education. Alexandria: ACTFL. [Google Scholar]

- Yacek, Douglas. 2018. Thinking controversially: The psychological condition for teaching controversial issues. Journal of Philosophy of Education 52: 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yulita, Leticia, and Melina Porto. 2017. Human Rights Education in Language Teaching. In From Principles to Practice in Education for Intercultural Citizenship. Edited by Michael Byram, Irina Golubeva, Han Hui and Manuela Wagner. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 225–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zembylas, Michalinos, and Claire McGlynn. 2012. Discomforting pedagogies: Emotional tensions, ethical dilemmas and transformative possibilities. British Educational Research Journal 38: 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zembylas, Michalinos, and Vivienne Bozalek. 2017. Re-imagining socially just pedagogies in higher education: The contribution of contemporary theoretical perspectives. Education as Change 21: 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zembylas, Michalinos. 2013. Critical pedagogy and emotion: Working through ‘troubled knowledge’ in posttraumatic contexts. Critical Studies in Education 54: 176–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zembylas, Michalinos. 2015. ‘Pedagogy of discomfort’ and its ethical implications: The tensions of ethical violence in social justice education. Ethics and Education 10: 163–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zembylas, Michalinos. 2017. Re-contextualising human rights education: Some decolonial strategies and pedagogical/curricular possibilities. Pedagogy, Culture & Society 25: 487–99. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).