Abstract

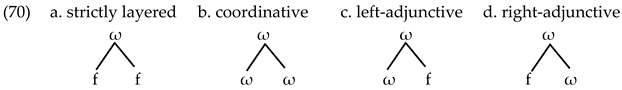

This paper investigates the role recursive structures play in prosody. In current understanding, phonological phrasing is computed by a general syntax–prosody mapping algorithm. Here, we are interested in recursive structure that arises in response to morphosyntactic structure that needs to be mapped. We investigate the types of recursive structures found in prosody, specifically: For a prosodic category κ, besides the adjunctive type of recursion κ[κ x], κ[x κ], is there also the coordinative type κ[κ κ]? Focusing on the prosodic forms of compounds in two typologically rather different languages, Danish and Japanese, we encounter three types of recursive word structures: coordinative ω[ω ω], left-adjunctive ω[f ω], right-adjunctive ω[ω f] and the strictly layered compound structure ω[f f]. In addition, two kinds of coordinative φ-compounds are found in Japanese, one with a non-recursive (strictly layered) structure φ[ω ω], a mono-phrasal compound consisting of two words, and one with coordinative recursion φ[φ φ], a bi-phrasal compound. A cross-linguistically rare type of post-syntactic compound has this biphrasal structure, a fact to be explained by its sentential origin.

1. Prosodic Recursion and the Nature of Recursive Subcategories

Under what conditions do recursive structures arise in prosody? “Recursion”, or “unbounded nesting”—refers to “a procedure that calls itself, or […] a constituent that contains a constituent of the same kind” (Pinker and Jackendoff 2005, p. 203). The first characterization concerns recursive procedures, where one of the steps of the procedure is an invocation of the procedure itself, which is irrelevant for prosody since there are no autonomous procedures of phonological word or phrase building that would simply call themselves. It is the second characterization that is relevant: Phonological constituency from the word up originates through a general syntax–prosody mapping procedure, and recursive structures arise as part of this mapping, in two specific situations: (i) under the pressure of phonological wellformedness constraints—for example, (maximal) binarity can force a constituent to be reorganized into smaller subconstituents of the same category, as shown, for example, in Kubozono (1988, 1989) for Japanese; (ii) in response to syntactic structure that needs to be mapped, as shown in Ladd (1986, 1988) for English. Both cases of prosodic recursion have withstood the test of time very well, and we are here interested in the second one. Such strictly interface-based recursive prosodic structure is intrinsically limited to constituents that are involved in the mapping procedure—i.e., the word and beyond.1

In Match Theory (Selkirk 2011; Elfner 2012; Ito and Mester 2015, among others), mapping of recursive syntactic structure usually results in recursive prosodic φ- and ι-structure, unless counteracted by higher-ranking phonological wellformedness constraints, within a system of Optimality Theoretic (OT) constraints (Prince and Smolensky 2004). However, at the word level, mapping from morphological words (and/or syntactic X0 terminals) usually results in single and non-recursive prosodic ω-structure, except when functional elements (e.g., clitics, affixes, function words) that do not map to full prosodic words are involved (Selkirk 1996; Bennett 2018), and when counteracted by higher-ranking phonological wellformedness constraints.2 In this paper, we first address a few fundamental issues connected with recursion in prosody (Section 1.1 and Section 1.2), and then turn to the kinds of recursive structures found in prosody, using compounds in Danish and Japanese as an empirical basis (Section 2). Section 3 concludes, and Appendix A assembles all constraints posited in this paper.3

1.1. Fundamental Issues

Syntactic structure is intrinsically recursive, and the syntax–prosody mapping brings out prosodic recursivity in a potentially unbounded way at the φ- and ι-level—but how about the word level? Here, unambiguous evidence for truly unbounded morphosyntactic recursion is harder to find, and we mostly encounter a single level of embedding, or maximally two. One can reasonably question whether this state of affairs justifies the unbounded representational power that comes with recursion.

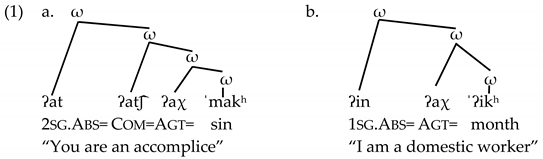

It is therefore of some importance that, while rare, unbounded morphosyntactic recursion at the word level does exist. A relevant case appears in Bennett (2018), who shows that recursion of the prosodic word is indispensable for an adequate analysis of the prefixal phonology of Kaqchikel. Two processes widespread in Mayan languages, glottal stop insertion and degemination, receive a simple treatment only if unbounded, iterative ω-recursion is permitted. Here, we illustrate the first case. Underlyingly, vowel-initial words receive an epenthetic glottal stop at the surface. A certain class of prefixes forms recursive ω-structures, such that after every prefix a new ω is initiated, phonetically manifested in iterative insertion of [ʔ] (1).4

To account for the multiple loci of epenthesis in such examples without prosodic recursion, we would need to assume four distinct prosodic categories, which would all have to be co-present in the same morphological word. Bennett (2018, pp. 11–13, 16–22) shows in detail that level ordering and output–output faithfulness are no way out, and that parsing the prefixes as separate prosodic words would wrongly predict stress on each prefix (since every prosodic word in Kaqchikel receives stress on its final syllable). Recursively adjoined structure as in (1) correctly predicts stress on the final (minimal) ω.

In a prosodic structure with multiple instances of a recursive category, are all instances of the recursive category predicted to have strictly identical phonological properties? Analyses making use of recursive categories often find good reason to assign different properties. According to one line of criticism, this is a contradiction (Vogel 2009b, p. 71; see also Vogel 2009a; Vigário 2010): “A constituent is understood to be a particular type of string, and all constituents of a given type exhibit the same properties, regardless of the size or internal structure of the constituent”.

This criticism fails to appreciate the distinction between grammatical categories (such as “noun phrase” and “prepositional phrase”) and grammatical relations or functions (such as “subject” or “object”) made since the beginnings of generative grammar (see Chomsky 1965, pp. 63–74). All instances of a recursive category are of course of the same category, and as such share a set of properties. However, the different instances of the recursive category stand in different relations to the overall structure, and in this respect can have different properties. This is no more of a contradiction than to say that subjects and objects have different properties in virtue of their different relations to the rest of the sentence, while being of the same category “noun phrase”. As Chomsky (1965, p. 69) points out, translating relational distinctions into categorial distinctions is not only redundant—since the distinctions are already manifest in the structure—but also a category mistake since it “confuses categorial and functional notions by assigning categorial status to both, and thus fails to express the relational character of the functional notions”.

1.2. Minimal and Maximal Subcategories

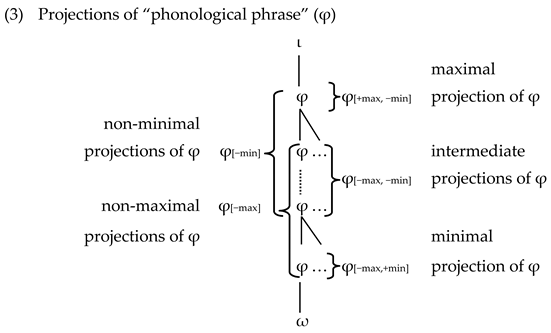

An important relational distinction in prosody is that between minimal and maximal instances of a recursive category (Ito and Mester 2007, p. 103; 2012, pp. 287–89; 2013, pp. 22–23), which we will for the sake of brevity refer to as “subcategories” (see also Elfner 2012, p. 117; Selkirk and Lee 2015, p. 14). “Minimal” and “maximal” are relational notions, like “head” or “specifier”. On the other hand, “phrase” and “word” are categorial notions, like “preposition”, “syllable”, “labial”, or “tense”. In recursive prosodic structures, the standard tree-structural notions apply, such as head vs. non-head and maximal projection vs. minimal projection. In [α α β] and [β α α], the internal α is the (structural) head of the containing α; the topmost projection of α—i.e., α not dominated by α—is the maximal α; the lowest projection—i.e., α not dominating α—is the minimal α.

| (2) | max | min | def. | subcategories of φ |

| + | − | φ not dominated by φ | maximal φ | |

| − | − | φ dominated by and dominating φ | intermediate φ | |

| − | + | φ not dominating φ | minimal φ | |

| + | + | φ not dominated by and not dominating φ | non-recursive φ |

Haider (1993, p. 40) defines the binary projection features [±maximal] and [±minimal] in exactly this way, as a way to represent, for any given category, natural classes of recursive subcategories. We illustrate this in (3), using the phonological phrase as an example.

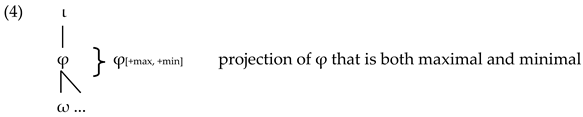

The natural class [+max, +min] picks out non-recursive categories (4). In strictly layered prosodic structures, for example, all categories have this specification.

With separate non-recursive categories instead of recursive subcategories, many language-specific categories would need to be created that are difficult to motivate cross-linguistically, but have in fact been proposed in previous work: We encounter not only the “minor phrase” and the “major phrase” (introduced in McCawley 1968), but also the “superordinate minor phrase” (Shinya et al. 2004), as well as the “accentual phrase”, the “intermediate phrase” (both in Pierrehumbert and Beckman 1988) and the “clitic/composite group” (Hayes 1989; Vogel 2009b). However, are minimal/maximal subcategories just notational variants, in a relational guise, of separate categories with different names? Besides Chomsky’s general arguments against this kind of identification summarized above, earlier work on Japanese has shown that the categories named “minor phrase” and “major phrase” are by no means equivalent to “minimal φ” and “maximal φ” (see Ito and Mester 2012, pp. 289–94 and Ishihara 2015 for details). One recursive φ category captures all the relevant domains for downstep (φ), initial rise (φ), and pitch accent (φ[+min]).

However, what about the evidence cited for additional categories, such as the clitic/composite group? To take a concrete example from Italian, in lexical words, we find intervocalically a contrast between the palatal lateral/ʎ/5 and dental/l/, as shown by the well-known minimal pair in (5a). At the beginning of lexical words,/ʎ/does not occur (5b). However, function words are not subject to this restriction (5c).6

| (5) | a. paglia [ˈpaʎːa] “straw” vs. palla [ˈpalːa] “ball” |

| b. libro [ˈlibro] “book”, *glibro [ˈʎibro] | |

| c. gli [ʎi] “to him” (also one allomorph of the masculine plural determiner) |

Vogel (2009a, pp. 78–79), who also notes the additional fact that the proclitics of standard Italian, such as gli, stand outside the domain of word stress assignment, takes this as evidence for a prosodic structure as in (6a): ω, the prosodic word, is the domain of word stress, not the clitic/composite group CG, and [ʎ] is banned ω-initially (6b), not cg-initially. These two facts justify a categorial distinction between ω and cg.

| (6) | a. [CG gli [ω perdono]] ‘(I) forgive him’ |

| b. *ʎ/[ω _ …] |

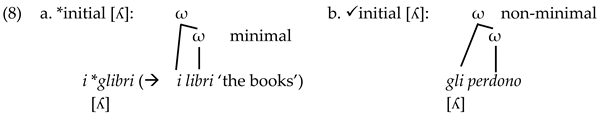

There is, however, reason to doubt the force of this argument for two different prosodic domains, and (Bennett 2018, p. 23) suggests that preverbal clitics in Italian are incorporated in a recursive prosodic word structure, so we are dealing with different projection levels of ω (this kind of approach goes back to Inkelas 1989). The palatal lateral [ʎ] is ruled out at the beginning of ω[+min] (7), which is also the domain for word stress.

| (7) | * ʎ/[ω[+min] _ …] |

This yields the correct results (8) without a need for a separate clitic/composite group category.

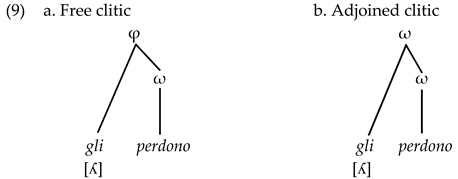

Taking a slightly different line, Peperkamp (1997, chp. 5) argues that clitics in Standard Italian directly attach to the φ-phrase (9a), rather than forming a recursive prosodic unit with the verb (9b).

If so, we have a contrast between ω and φ, and not between ω[+min] and ω[−min]: [ʎ] is ruled out at the beginning of a ω, and permitted at the beginning of a φ (where it can occur only if φ does not begin with a ω). Only a fuller investigation can determine the merits of each analysis, the important point being that, either way, there is no evidence here for a separate clitic group category.

2. Types of Prosodic Recursion

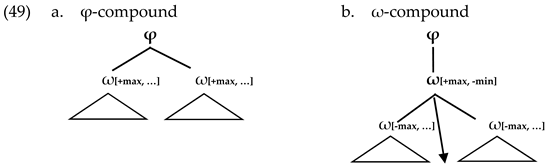

The type of recursive structure just seen is what we refer to as “adjunctive”: α → α + x or x + α, with x ≠ α (“unbalanced”, in the terminology of Hulst 2010). An important question is whether, besides adjunctive recursion, there is also a coordinative type α → α + α (“balanced”)? The two are clearly distinct, and it has been argued (see Vigário 2010, p. 524) that only the adjunctive type exists. Pinker and Jackendoff (2005, p. 211) regard only the coordinative type as true recursion: “Syllables can sometimes be expanded by limited addition of non-syllabic material; the word lengths, for example, is in some theories analyzed as having syllabic structure along the line of [Syl [Syl length] s] […]. However, there are no syllables built out of the combination of two or more full syllables, which is the crucial case for true recursion”. There is little doubt that there are no monster syllables built out of two syllables in natural languages, the only question is whether this ban on coordinative recursion holds for all of prosodic structure. From our perspective, this issue is not settled. Compounds are an obvious place to look for evidence, and we present several cases where the coordinative type of recursion seems to be instantiated, leading to the conclusion that coordinative recursion exists in prosody and laying to rest any doubts as to whether there is “true” recursion in prosody.

2.1. Prosodic Recursion in Compounds

Match constraints (Selkirk 2011; Elfner 2012; Ito and Mester 2015, among others) require syntactic phrase structure to map to prosodic structure. Of relevance here is Match (X0, ω), defined in (10), which maps morphological/syntactic words to prosodic word.

| (10) | Match X0: Match (X0, ω) | Assign one violation for every terminal node X0 in the syntax such that the segments belonging to X0 are not all dominated by the same prosodic word ω in the output. |

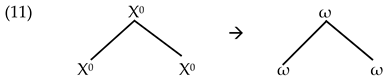

Given this interface constraint, a faithfulness constraint in a broad sense, the morphosyntactic structure of compounds should be mirrored, in the default case, in a coordinative type of ω-recursion (11).

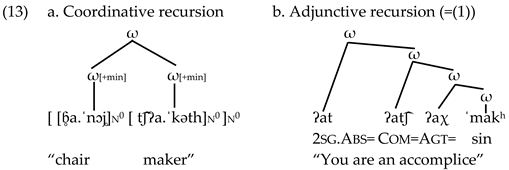

We begin by briefly returning to the case of Kaqchikel examined above in Section 1.1. Bennett (2018) is careful to note that the argument from stacked prefixes only offers support for adjunctive and not for coordinative recursion. On the other hand, compounds in Kaqchikel seems to call for a prosodic structure with coordinative recursion. Each compound member has word stress (12), so the whole compound must consist of two ω’s.

| (12) | b’anöy ch’akät | [ɓ̥a.ˈnɔj̥ # t͡ʃʔa.ˈkəth] | “chair maker” |

| meqeb’äl ya’ | [me.qe.ˈɓ̥əl̥#ˈjaʔ] | “water heater” |

Since the entire compound word is itself an X0, (10) also dictates that the entire compound word be matched by a prosodic ω, resulting in the coordinative recursion structure in (13a). Here, each member, as a minimal prosodic word, receives stress, which is a property of minimal prosodic words in Kaqchikel.

By the same token, the adjunctive recursion structure assigned to prefixed forms (13b) correctly predicts that they receive a single stress on their last (minimal) word.

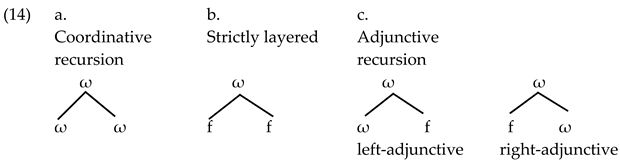

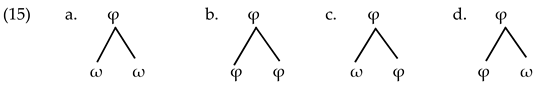

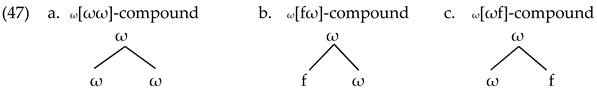

Given MatchX0 (10), it is not surprising, but rather expected, that compounds would show evidence of coordinate ω-recursion (11). More revealing is that when MatchX0 is dominated by certain prosodic wellformedness constraints, the resulting structure does not always conform to this default expectation of coordinative recursion, resulting in syntax–prosody mismatches. In our investigation, we have found a range of types of prosodic compounds, including the four structures in (14).

In (14), the top node of the compound X0 corresponds to a ω, but the compound members (also X0 in the syntax) are not necessarily matched with a ω and can be a sub-ω prosodic unit like the foot (f) (or perhaps even the syllable (σ)). Further investigation has revealed that even the top X0 is in certain situations matched not with ω, but with φ, resulting in structures such as those in (15a–d).

The emergence of such prosodic structures turns out to solve some of the puzzles associated with the complex patterns of glottal (stød) accentuation and deaccentuation in Danish compounds (Section 2.2), and an explanatory account may be within reach for the even more complex array of patterns of accentuation in Japanese compounds (Section 2.3).

2.2. Danish Compound Structures

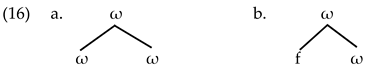

From the available possibilities of prosodic compounds in (14), we will show that there are two possibilities for Danish compounds, the coordinative (default) structure in (16a), and the adjunctive structure in (16b), where the initial compound member does not project a ω.

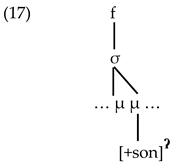

The phonological analysis of the Danish stød, a glottal accent (ʔ), follows Ito and Mester (2015) and Bellik and Kalivoda (2018). Here, we give a brief recap of the core elements of the analysis. For further details and justification, see the works cited. The glottal accent (ʔ) is realized on a sonorous second mora of a heavy syllable (=a monosyllabic foot) as schematically shown in (17).

In words with more than one monosyllabic foot, the glottal accent appears only on the last one in the word, as a consequence of the constraint RightmostGlottalAccent (18).

| (18) | RightmostGlottalAccent: | Glottal accent falls on the rightmost foot in the prosodic word. |

Important to note here is that the glottal accent should not be equated with stress. It is most akin to the behavior of pitch accent (in other Scandinavian languages), whose tonal association is correlated to, but independent of, stress. Here, the glottal accent (though segmental) behaves in a similar way. It is associated with a stressed syllable, but only in final position (rightmost in the word). We see the glottal accent associated with a stressed syllable in final position, with primary stress (19a) or with secondary stress (19b).7

| (19) | a. With primary stress: | b. With secondary stress: | ||

| ω[(ˌpar)(ˈtiːʔ)] | “party” | ω[(ˈmar)(ˌtyːrʔ)] | “martyr” | |

| ω[(ˌmedi)(ˈciːʔn)] | “medicine” | ω[(ˈpara)(ˌdiːʔs)] | “paradise” | |

| ω[(ˌbage)(ˈriːʔ)] | “bakery” | ω[(ˈgud)(ˌdomʔ)] | “divinity” | |

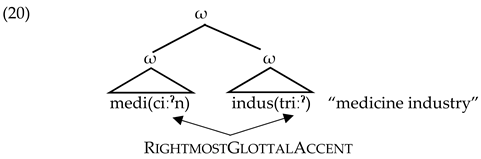

Turning now to compounds, given RighmostGlottalAccent and Match (X0, ω), each compound member should receive a glottal accent, as in (20). Relevant foot structures are indicated with “(…)”.8

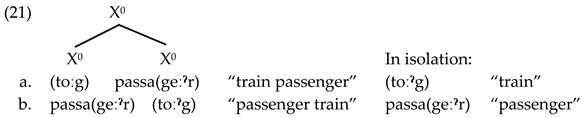

However, some initial compound members unexpectedly do not show a glottal accent. As shown in (21), even though their isolation forms appear with the glottal accent, [toːʔg] “train” only shows the glottal accent as second member (21b), not as initial member (21a).9 On the other hand, [passageːʔr] “passenger” always shows glottal accent, whether as initial or as second member of the compound.

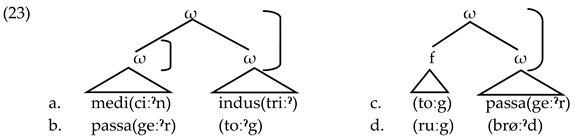

Ito and Mester (2015) hypothesize that the distinction in accent loss and accent retention arises from a distinction in prosodic structure. The crucial factor is the prosodic length of the initial member of the compound X0: when short (=one foot) (22cd), without glottal accent10; when long (longer than one foot) (22ab), with glottal accent. The second (head) member of the compound X0 carries glottal accent regardless of prosodic length.

| (22) | In isolation: | |||

| a. | medi(ciːʔn) indus(triːʔ) | “medicine industry” | medi(ciːʔn) | indus(triːʔ) |

| b. | passa(geːʔr) (toːʔg) | “passenger train” | passa(geːʔr) | (toːʔg) |

| c. | (toːg) passa(geːʔr) | “train passenger” | (toːʔg) | passa(geːʔr) |

| d. | (ruːg) (brøːʔd) | “rye bread” | (ruːʔg) | (brøːʔd) |

The glottal accent distribution in compounds would follow straightforwardly if the prosodic structure is coordinative for (22ab) and adjunctive for (22cd), as illustrated in (23). The terms “coordinative” and “adjunctive” here refer strictly to the type of recursion defined in the previous section, not to a semantic classification of compounds, where “coordinative compounds are those whose elements can be interpreted as being joined by and”, in the words of Bauer (2011, p. 552).

Glottal accent falls rightmost in all ω’s. In (23ab), both members are ωs, hence there are two stød locations (indicated by long right brackets). On the other hand, in (23cd), there is only one accent because the right edges of the larger ω and the smaller ω coincide.11 There are two related questions to be answered here. First, why are the short initial compound members in (23cd) only a foot (and not a ω)? Second, why are the short second compound members in (23bd) a ω (and not just a foot)?

The first question finds an answer in the constraint WordBinarity, ranked above the interface constraint Match (X0, ω).

| (24) | WordBinarity: | Prosodic words must be binary. Violated by words measuring no more than a single foot. |

This kind of binarity constraint was argued for on the basis of Japanese truncation data in Ito and Mester (1992). In terms of Bellik and Kalivoda (2018), it is branch-counting, not word-counting: ω must have more than one branch, i.e., have more than one immediate daughter. Branchingness conditions of this kind play a pervasive role in phrasal phonology, as shown by Nespor and Vogel (1986) with many examples where non-branching phonological phrases get restructured in order to avoid a binarity violation.

Short words such as to:g consist of a single foot, and if mapped onto their own ω, would violate WordBin (25ai). Since the prosodic constraint WordBin ranks above the interface constraint Match (X0, ω), the fully matched structure will only arise when neither word violates WordBin, as in (25bi) (candidates violating higher ranking Rightmost are not considered here).

| (25) | [X0 [X0] [X0] ] | WdBin | MatchX0 | |||

| a. | i. | [ω[ω(toːʔg)][ω(passa)(geːʔr)]] | *! | |||

| ► | ii. | [ω f(toːg) [ω(passa)(geːʔr)]] | * | |||

| b. | ► | i. | [ω[ω (medi)(ciːʔn)][ω(indus)(triːʔ)]] | |||

| ii. | [ω f(medi)f(ciːn) [ω(indus)(triːʔ)]] | *! |

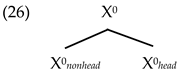

Turning to the second question, why do the short second compound members in (23bd) surface as ω’s, violating WordBin? We propose that these structures are obtained by a higher-ranked interface constraint, namely, one which imposes word-hood on heads of compounds. Assuming syntactic right-headedness, the head X0 is easily identified (26).

| (27) | MatchHead: Match (X0head, ω) | Assign one violation for every terminal node X0 in the syntax that is a head such that the segments belonging to X0 are not all dominated by the same prosodic word ω in the output. |

Any X0 that is a head is subject to a special Match constraint (27), ranked as in (28).

(28) MatchHead ≫ WdBin ≫ MatchX0

This has the desired consequences, as shown in (29) (see (22) for glosses). For perspicuity, only the winners are annotated in the leftmost column with their prosodic profiles, and we can confirm that compounds with members of various sizes (short–short, long–short, short–long, long–long) all converge on the two prosodic profiles ω[fω] and ω[ωω].

Even though (29aiii) violates WdBin, its competitor (29ai), with no WdBin violations, violates the higher-ranking MatchHead. In (29b), on the other hand, both (29biii) and its competitor (29biv) have the same violation profile for MatchHead and WdBin, so the decision is handed down to the lower-ranking general MatchX0, which favors (29biv), where each compound member is parsed as a word. The examples from (25) are repeated in (29cd) to confirm that the addition of MatchHead does not lead to wrong outcomes.

| (29) | [X0 [X0 …] [X0hd …]] | Match Head | Wd Bin | Match X0 | |||

| a. | i. | [ω (ruːg) (brøːʔd)] | *! | ** | |||

| ii. | [ω[ω(ruːʔg)] (brøːʔd)] | *! | * | * | |||

| ► | iii. | ω[fω] | [ω (ruːg) [ω(brøːʔd)]] | * | * | ||

| iv. | [ω[ω(ruːʔg)][ω(brøːʔd)]] | **! | |||||

| b. | i. | [ω (passa)(geːr) (toːʔg)] | *! | ** | |||

| ii. | [ω[ωpassa(geːʔr)] (toːʔg)] | *! | * | ||||

| iii. | [ω (passa)(geːr) [ω(toːʔg)]] | * | *! | ||||

| ► | iv. | ω[ωω] | [ω[ω(passa)(geːʔr)][ω(toːʔg)]] | * | |||

| c. | i. | [ω (toːg) (passa)(geːʔr) ] | *! | ** | |||

| ii. | [ω[ω(toːʔg)] (passa)(geːʔr) ] | *! | * | * | |||

| ► | iii. | ω[fω] | [ω (toːg) [ω(passa)(geːʔr)]] | * | |||

| iv. | [ω[ω(toːʔg)][ω(passa)(geːʔr)]] | *! | |||||

| d. | i. | [ω (medi)(ciːn) (indus)(triːʔ)] | *! | ** | |||

| ii. | [ω[ω (medi)(ciːʔn)] (indus)(triːʔ)] | *! | * | ||||

| iii. | [ω (medi)(ciːn) [ω(indus)(triːʔ)]] | *! | |||||

| ► | iv. | ω[ωω] | [ω[ω (medi)(ciːʔn)][ω(indus)(triːʔ)]] |

Simplex words are their own heads, so MatchHead applies to them, and MatchHead » WdBin ensures that they are always mapped onto their own ω (30),12 which is both minimal and maximal (4).

| (30) | [x0 brøːd] “bread” | MatchHead | WdBin | MatchX0 | |

| ► | [ω(brøːʔd)] | * | |||

| (brøːʔd) | *! | * |

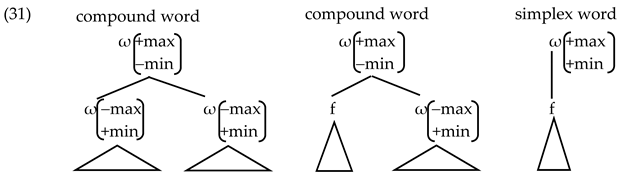

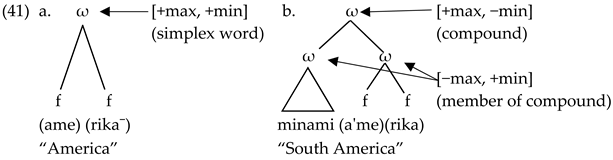

All compounds, whatever the length composition of their members, receive compound stress on their leftmost word, whereas simplex words in general receive word stress towards the end of the word following a Latin-like stress rule, as in many related stress systems including Dutch, English, German, and other Scandinavian stress systems.13 In terms of the prosodic subcategory theory outlined in Section 1.2, this means that compound stress refers to ω[+max, −min], whereas word stress refers to ω[+min], as illustrated below.

Overall, we have a distinction between simplex words [+max, +min], compounds [+max, −min], members of compounds [−max, +min], and in addition, members of compounds that are themselves compounds [−max, −min] (not illustrated here). We state the compound stress constraint as in (32).

(32) Compound stress: Main stress is leftmost in [+max, −min] words.

In conclusion to this section, to the extent that this overall analysis crucially depends on coordinative recursion, the doubts sometimes expressed regarding its existence—for example, in (Vigário 2010, p. 524)—appear ill-founded.

2.3. Japanese Compound Structures

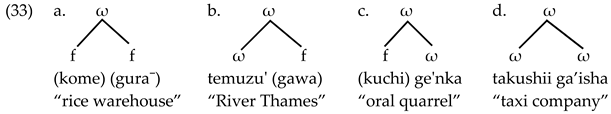

Moving on to Japanese compounds, we find both adjunctive and coordinative structures similar to Danish, but with interesting differences. Besides the two types of prosodic compound structures, ωω and fω, seen in Danish ((23) above), we find, in addition, ωf and ff-compounds (Kubozono et al. 1997; Ito and Mester 2007, 2018), as illustrated in (33). Following standard practice, accent location is marked by [‘] after the accented vowel, indicating the location of the tonal fall; unaccentedness is shown by a final [ˉ].14

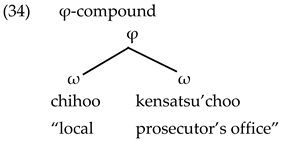

The OT system responsible for these structures and their accentual properties will be presented in Section 2.3.1. We will see in Section 2.3.2 that Japanese also exhibits a compounding type φ[ωω], where the topmost X0 node of the compound corresponds not to ω, as in (33), but to φ (34).

A single Composite Group category to represent all compounds, as seems to be the suggestion in Vogel (2009a, p. 66) and Guzzo (2018), would not be able to handle this kind of distinction between different compound structures.

2.3.1. ω-Compounds

Turning first to the full range of ω-compounds in Japanese in (33), we see that (33a) and (33b), which were not part of the Danish prosodic compound typology are indeed found in Japanese, with somewhat unexpected but far-reaching consequences. For Danish, high-ranking MatchHead (27) prevents the structures [ff] (33a) and [ωf] (33b) from emerging as winners, because the head of the compound (=second compound member) must be mapped to a prosodic ω (see (29) above).

(35) Danish ranking: MatchHead ≫ WdBin ≫ MatchX0

What then is different in Japanese so that all four possible structures rooted in ω with daughters chosen from {ω, f} are available, and wordhood is no longer enforced on heads of compounds? It arises from the simple reranking of WordBinarity (24) and MatchHead (27).

(36) Japanese ranking: WdBin ≫ MatchHead, MatchX0

High-ranking WordBinarity means that a compound member whose size is a single foot cannot be parsed as a ω. This is why ω[ff] (37ai), with two foot-sized members, wins over the other candidates (37aii-iv)) that violate the WdBin in one way or another, even though they have less violations of the Match constraints (we again annotate the winners with their prosodic profiles).

When one of the compound members is foot-sized, as in (37b) and (37c), the Match constraints determine the winner. When both compound members are larger than a foot (37d), the fully matching candidate ω[ωω] (37biv) wins with no violations. The reader can confirm that the Danish ranking (29) leads to either ω[ωω] or ω[ωf], whereas for Japanese (37) all four possibilities ω[ff], ω[ωf], ω[fω], ω[ωω] arise.

| (37) | [X0 [X0 …] [X0hd …]] | Wd Bin | MatchHead | Match X0 | |||

| a. | ► | i. | ω[ff] | [ω (kome) (gura)ˉ] | * | ** | |

| ii. | [ω[ω(kome)] (gura)ˉ] | *! | * | * | |||

| iii. | [ω (kome) [ω(gura)ˉ]] | *! | * | ||||

| iv. | [ω[ω(kome)][ω(gura)ˉ]] | *!* | |||||

| b. | i. | [ω (temu)zu’(gawa)] | * | **! | |||

| ► | ii. | ω[ωf] | [ω [ω(temu)zu]’ (gawa)] | * | * | ||

| iii. | [ω (temu)zu’ [ω(gawa)]] | *! | * | ||||

| iv. | [ω [ω(temu)zu]’ [ω(gawa)]] | *! | * | ||||

| c. | i. | [ω(kuchi) (ge’n)ka] | * | **! | |||

| ii. | [ω[ω(kuchi)](ge’n)ka] | *! | * | * | |||

| ► | iii. | ω[fω] | [ω (kuchi) [ω(ge’n)ka]] | * | |||

| iv. | [ω [ω(kuchi)] [ω(ge’n)ka]] | *! | |||||

| d. | i. | [ω(taku)(shii) (ga’i)sha] | * | **! | |||

| ii. | [ω (taku)(shii)](ga’i)sha] | * | *! | ||||

| ii. | [ω (taku)(shii) [ω (ga’i)sha]] | *! | |||||

| ► | iv. | ω[ωω] | [ω [ω (taku)(shii)] [ω(ga’i)sha]] |

With these differing prosodic structures arising from high-ranking WordBinarity and the interface Match constraints, several questions regarding the location of compound accent need to be explored: When the compound accent falls at the beginning of the second member—so-called junctural accent, as in (33c) and (33d)—how exactly is its location determined? Why is the accent assigned in this position in (33c) and (33d), but at the end of the first member in (33b)? Additionally, why is (33a) unaccented, i.e., does not show any accent?

The unaccentedness question for ω[ff]-compounds (33a) receives the most straightforward answer. The default accent location in Japanese simplex words is antepenultimate (similar to English/Dutch/German/Latin, etc.), except that 4μ words like amerikaˉ are overwhelmingly unaccented. The gist of the accent analysis in Ito and Mester (2016)—interested readers should consult this paper for details—is that the optimal footing of 4μ words is a parse into two feet (μμ)(μμ) because of high-ranking InitialFoot and NonFinality(Ft’), where Ft’ refers to the accent-bearing head foot of the word. The low-ranking position of WordAccent in Japanese, the constraint requiring a prominence peak in prosodic words, leads to unaccentedness as the optimal solution for ff-words (38a): [(ame)(rika)ˉ].

| (38) | /amerika/ “America” | InitFt | Non Fin(Ft’) | Right most | Wd Acc | Parse Syll | ||

| ► | a. | [(ame)(rika)ˉ] | * | |||||

| b. | [(a’me)(rika)] | *! | ||||||

| c. | [(ame)(ri’ka)] | *! | ||||||

| d. | [ a(me’ri)ka ] | *! | ** |

However, low-ranking WordAccent does not mean that all words become unaccented. Whenever the dominant constraints, NonFin(Ft’), Rightmost, and InitialFt, can all be fulfilled without violating WordAccent, the latter exerts its force, ensuring antepenultimate prominence for 3-, 5-, and 6-syllable cases (and many others). We illustrate with the 5-syllable word baruse’rona in (39).

| (39) | /baruserona/ “Barcelona” | InitFt | Non Fin(Ft’) | Right most | Wd Acc | Parse Syll | ||

| ► | a. | [(baru)(se’ro)na] | * | |||||

| b. | [(baru)(sero)naˉ] | *! | * | |||||

| c. | [(ba’ru)(sero)na] | *! | * | |||||

| d. | [(baru)se(ro’na)] | *! | * | |||||

| e. | [ ba(ru’se)(rona)] | *! | * | * |

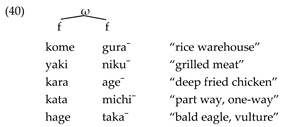

For a ω[ff]-compound, there is no recursion of ω since WordBinarity is high-ranking (see (36) above), forestalling a ω-parse of its f-sized members. As a result, the compound is prosodically indistinguishable from a simplex (non-compound) ff-word such as amerikaˉ in (38). The analysis in (38) predicts correctly that for ω[ff]-compounds unaccentedness should be the default, as illustrated in (40) with some examples.

The unaccentedness of (33a) thus follows straightforwardly from the simplex ω-structure assigned to ff-compounds.15 All other types of compound types in (33) are accented, and the main question is how the accent location is determined. A related puzzle is why simplex words such as (41a) [ω(ame)(rika)ˉ] “America”, unaccented in isolation, become accented in compounds such as (41b) [ω[ωminami][ω(a’me)(rika)]] “South America”. A closer look at the prosodic subcategories, as annotated in (41), reveals that our theory already makes the required threefold distinction between simplex words [+max, +min], compounds [+max,−min], and members of compounds [−max,+min] (and in addition, members of compounds that are themselves compounds [−max, −min]).

Recall that low-ranking WordAccent (42a) leads to unaccentedness in (non-recursive) ff-words (38). Given higher-ranking WordMaxAccent (42b), a constraint requiring accent in compounds, formally ω[+max, −min], an accent is ensured in coordinative compound structures (41b), as well as in the adjunctive structures (33b–c) with recursive ω’s.

| (42) | WordAccent | A prosodic word contains a prominence peak.16 Violated by prosodic words not having a prominence peak. |

| WordMaxAccent | A [+max, −min] prosodic word contains a prominence peak. Violated by [+max, −min] prosodic words not having a prominence peak. |

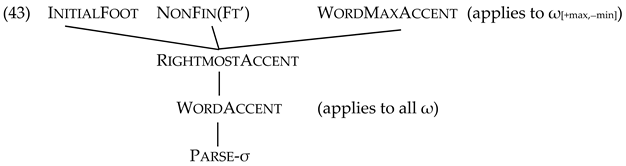

It may seem that an additional constraint is still needed in order to designate the location of the assigned accent, which falls in general at the beginning of the second member, as in (33d), the so-called junctural accent (see Kubozono 1995). However, this is no more than a descriptive term, not an analysis, and an awkward and stipulatory reference to the juncture between the compound members will not count as an explanation. It comes therefore as a pleasant surprise that the location of junctural accent already follows from the default accent analysis for simplex words—with the single addition of WordMaxAccent, as shown in the Hasse diagram (43) below.

Since the unaccented candidate (44a), the winner in simplex word cases, violates WordMaxAccent, the next-harmonic candidate (44b) is selected, which assigns initial accent on the second compound member (since NonFinality(Ft’) ≫Rightmost (43).

| (44) | /minamiˉ+amerikaˉ/ “South America” | InitFt | NonFin (Ft’) | Word MaxAcc | Right most | Wd Acc | Parse -σ | ||

| a. | [ω [ω (mina)miˉ] [ω(ame)(rikaˉ)]] | *! | *** | * | |||||

| ► | b. | [ω [ω(mina)miˉ] [ω(a’me)(rika)]] | * | * | * | ||||

| c. | [ω [ω (mina)miˉ] [ω(ame)(ri’ka)]] | *! | * | * | |||||

| d. | [ω [ω (mina)miˉ] [ω a(me’ri)ka]] | *! | * | *** |

Note that no specific reference to the location of compound accent is necessary here since it falls out from the already established constraint ranking. For the simplex ω, repeated from (38), for ease of comparison, the unaccented form (45a) continues to emerge as the winner because WordMaxAccent is without force here.

| (45) | /amerika/ | InitFt | NonFin(Ft’) | WordMaxAcc | Rightmost | WdAcc | Parse-σ | ||

| ► | a. | [ω(ame)(rikaˉ)] | * | ||||||

| b. | [ω(a’me)(rika)] | *! | |||||||

| c. | [ω(ame)(ri’ka)] | *! | |||||||

| d. | [ω a(me’ri)ka] | *! | ** |

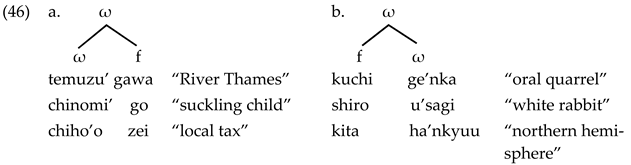

How about ω-compounds with unequal sisters, composed of ω and f in either order, as in (33bc), repeated here in (46) with additional examples?

For ω[fω]-compounds (46b), the constraint ranking in (43) selects the correct candidate with initial accent on the second member ω[(ge’n)ka], just as in ω[ωω]-compounds such as (44). ω[ωf]-compounds (46a) behave differently: Here, the second member is a sub-word constituent, and the result is a suffixation-like structure, leading to preaccentuation behavior (for details, see Ito and Mester 2018)17 Given these three types of recursive (coordinative and adjunctive) ω-structures recapitulated in (47), a large part of junctural accentuation follows from independently motivated constraints and rankings, needing no separate stipulation.

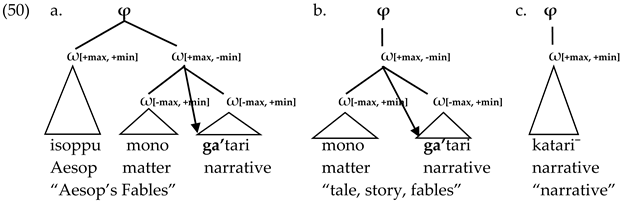

2.3.2. φ-Compounds

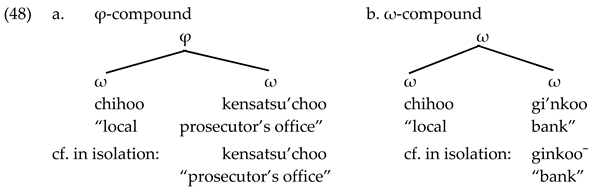

We began our investigation of Japanese compound typology by pointing out that besides the variety of ω-compound types (33), we also find φ-compounds (34), where the topmost X0 node of the compound corresponds not to ω, but to φ. As exemplified in (48) with prototypical examples, the main accentual difference between these two types of compounds is the following: In ω-compounds (48b), as seen in the last section, a new accent arises at the juncture of the compound members, irrespective of the original accent of the word in isolation, i.e., [ginkoo−] in isolation and […+ gi’nkoo] as second member. On the other hand, in φ-compounds (48a), the second member retains its original accent (or lack thereof), i.e., [kensatsu’choo] in isolation remains […+ kensatsu’choo] as second member.

This accentuation difference follows from our ω-compound analysis above, which makes crucial use of recursive ω-structure. Given the constraint ranking in (43), with high-ranking WordMaxAccent (42b), a (new) accent is assigned in (49b) indicated by the downwards arrow, where the top ω-node is ω[+max, −min]. For clarity, we add the φ-node immediately dominating the top ω-node, which identifies it as a maximal ω.

On the other hand, the constraints in (43) are not applicable to the φ-compound (49a), since the top node of the compound is a φ that dominates two maximal ω’s. If the members of (49a) are themselves compounds, then they would also be ω[+max, -min],and WordMaxAccent (42b) would be enforced in the individual members. A case in point is a right-branching compound structure as in (50a), where the second member is itself a ω-compound, and hence subject to WordMaxAccent. When the second member is a ω-compound by itself (50), WordMaxAccent is also enforced.

Given the distinction between ω-compounds and φ-compounds, we have already accounted for why there is no new accent introduced in φ-compounds. The question now is how to determine whether the top node of a compound is a ω or a φ. According to previous work (Kubozono et al. 1997; Ito and Mester 2007), this is determined by prosodic length factors: If the head (here, the second member) exceeds two bimoraic feet (4μ), the whole form is parsed as a φ-compound (51a), otherwise it is parsed as a ω-compound (51b).

| (51) | a. head > 2f: φ-compound | |

| φ[chihoo + (ken)(satsu’)(choo)] | ”local prosecutor’s office” | |

| φ[chiho’o + (kin)(yuu)ki’(kou)] | “local financial institutions” | |

| φ[chiho’o + (koo)(kyoo)(da’n)(tai)] | “local public organization” | |

| b. head ≤ 2f: ω-compound | ||

| ω[chihoo + (gi’n)(koo)] | “local bank” | |

| ω[chihoo + (ke’e)ba] | “local horse racing” | |

| ω[chihoo + (ma’wa)ri] | “local rounds” |

This distinction follows from a head binarity restriction (52) (Ito and Mester 2007: 105), ranked above the matching constraint.

| (52) | BinMaxHead (ω[+max, −min]): | Heads of [+max, −min] prosodic words are maximally binary. Violated if the head has more than two immediate daughters.18 |

As BinMaxHead(ω) is ranked above MatchX0, the top node of the compound must be φ (53ai) and not ω (53aii). For (53b), the fully matched candidate (53bii) wins because it fulfills the MatchX0 constraint for every X0, including the topmost one.

| (53) | [X0 [X0 …] [X0 …] ] | BinMax Head(ω) | MatchX0 | |||

| a. | =(48a) | ► | i. | [φ [ω chihoo][ω (ken)(satsu’)(choo)]] | * | |

| ii. | [ω [ω chihoo][ω (ken)(satsu’)(choo)]] | *! | ||||

| b. | =(48b) | i. | [φ [ω chihoo][ω (gi’n)(koo)]] | *! | ||

| ► | ii. | [ω [ω chihoo][ω (gi’n)(koo)]] |

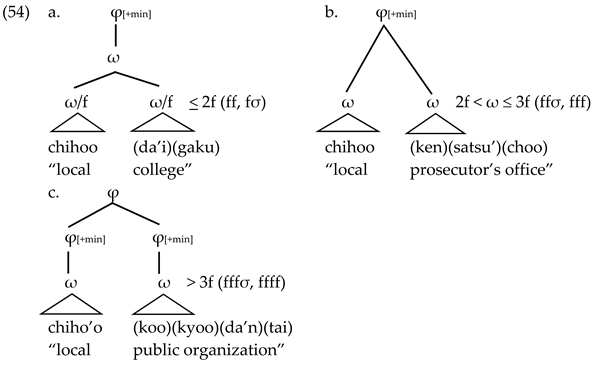

In (53) above, the overall prosodic level of a compound—ω[ωω] (53b) or φ[ωω] (53a)—is determined by whether or not the (righthand) head member satisfies the head binarity constraint (52). A further distinction within the φ-compound structures has been argued to exist in previous work (Kubozono et al. 1997; Ito and Mester 2007, 2018), namely, where the head-ω is larger than 3f. As shown in (54), the minimal φ is the domain of accent cumulativity (only one accent), so the monophrasal (54ab), but not the biphrasal (54c), show deaccentuation of their non-head member chiho’o “local”.

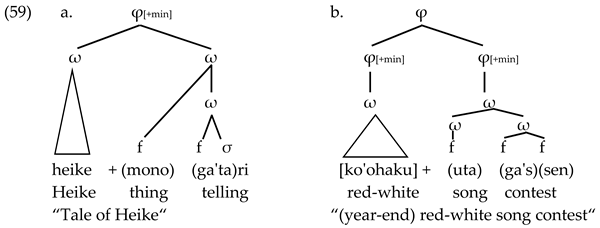

As for the prosodic length factor, the canonical compounds with binary heads (54a) are always monophrasal, and those with superlong heads (>3f) are always biphrasal (54c), but the intermediate (2f < ω ≤ 3f) cases (54b) can be either monophrasal (55a) or biphrasal (55b), including cases of variation (55c).

| (55) | a. [φ[ωheike] [ω(mono)(ga’ta)ri]] | “Tale of Heike” he’ike in isolation |

| b.[φ[φ[ωko’ohaku]][φ[ω(uta)(ga’s)(sen)]]] | “(year-end) red-white song contest” | |

| c. [φ[φ[ωse’kai]] φ[[ω(shin)(ki’ro)ku]]] ~ [φ[ωsekai] [ω(shin)(ki’ro)ku]] | “world new-record” |

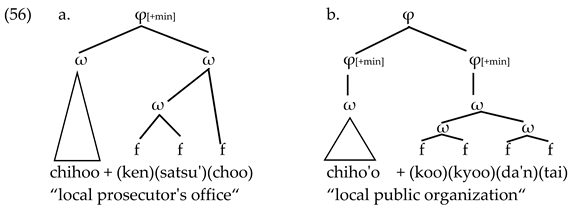

There are various criteria, some of them non-phonological (see Kubozono et al. 1997), that come into play when some φ-compounds become monophrasal (54b) and others biphrasal (54c). Although a fuller investigation is necessary, we speculate that the phonological criterion may involve another head binarity constraint. Long compound members tend to be compounds themselves, and viewing the full prosodic structure of the typical long (3-feet) and superlong (4-feet) cases reveals that while the former has only one ω in its right (head) member (56a), the latter has two ω’s (56b).

This is very reminiscent of the head binarity constraint on maximal ω, but at one level higher in the prosodic hierarchy. We can state the relevant binarity constraint as in (57).

| (57) | BinMax-φ[+min]: | Minimal φ’s are maximally binary. Violated if minimal φ dominates more than two (minimal) ω’s. |

Together with the prosody–syntax mapping constraint Match(φ, XP), which militates against parsing a string that is not a syntactic XP as a φ and plays a role similar to NoRecursivity-φ, BinMax-φ[+min] ensures the desired distinction for the two examples (56ab), as seen in (58ab).

| (58) | [X0 [X0 …] [X0 …] ] | BinMax -φ[+min] | Match (φ, XP) | ||

| a. | ► | i. | [φ [ω chihoo] [ω [ω(ken)(satsu’)](choo)]] | * | |

| =(56a) | ii. | [φ [φ [ω chiho’o]] [φ[ω[ω(ken)(satsu’)](choo)]]]] | **!* | ||

| b. | i. | [φ [ω chihoo] [ω[ω(koo)(kyoo)][ω(da’n)(tai)]]] | *! | * | |

| =(56b) | ► | ii. | [φ[φ[ωchiho’o]][φ[ω[ω(koo)(kyoo)][ω(da’n)(tai)]]]] | ** |

For the variable intermediate length cases (55), factors of a semantic and pragmatic nature that are not our topic probably also play a role. For example, whereas uta-ga’ssen (59b) is fully compositional, the contribution of mono’ in (59a) is not evident synchronically. This may favor promoting uta’ “song” in (59b) but not mono’ “thing” in (59a) to a full ω.

2.3.3. Other φ-Compounds

We here take up two other cases that result in φ-compound structures: one involving phrasal prefixation, and the other involving post-syntactic compounding. For both cases, different from the cases discussed above, there is no length restriction on the second member.

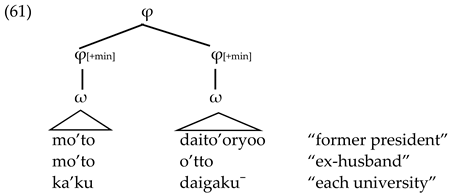

Phrasal prefixation is taken up in Poser (1990a) (see also Aoyagi 1969; Kageyama 1982, who introduced the term) as a case where a (minor) phrase boundary is found word-internally.

| (60) | mo’to | dai-to’oryoo | “former president” |

| mo’to | o’tto | “ex-husband” | |

| hi’ | gooritekiˉ | “non-realistic” | |

| ho’n | ka’igi | “this/present/current meeting” | |

| ka’ku | daigakuˉ | “each university” |

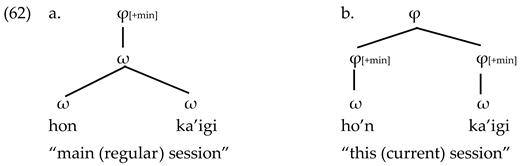

The term “phrasal” refers to the characteristic prosody induced by these prefixes: They form phonological φ-compounds, with the prefix and the stem each forming their own φ, as shown in (61). All the prosodic characteristics of φ are manifested in the second member—initial rise and, if accented, a tonal fall immediately following the accent.19

A revealing case is ho’n “the present”, homophonous with another morpheme meaning “main, regular”. With the meaning “regular”, it forms a normal ω-compound such as [ω[ωhon][ωka’igi]] “regular (main) session” (62a) and undergoes regular deaccentuation as first member. However, with the determiner-like meaning “this, the present”, it forms a φ-compound (62b) [φ[φho’n] [φka’igi]] “this (present) session” and preserves its accent as first member.

Such phrasal prefixes do not attach to syntactic phrases, but to lexical words (X0). As carefully shown by Poser 1990b (see also Kageyama 1982), these words exhibit the usual morphosyntactic characteristics of a compound word (separability, semantic scope, and lexical combinatorial restrictions), and not of a syntactic phrase.

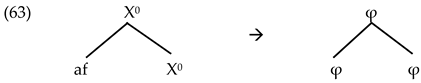

The mapping from morphosyntax to the prosodic structure must then be as in (63), which raises several questions.

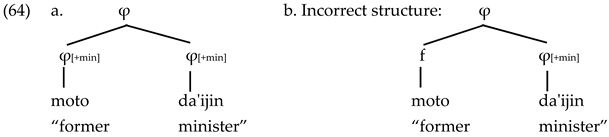

Given the prefixal morphological structure, why do we end up with a biphrasal prosody? Part of the answer comes directly from Poser’s proposal (following Inkelas 1989) that these phrasal prefixes have both a prosodic and morphosyntactic subcategorization: “Like other affixes, [they] morphologically subcategorize a stem [=X0]. Unlike other affixes, they prosodically subcategorize a minor phrase [=φ, JI/AM]” (Poser 1990b, p. 7). So, prosodic subcategorization maps the stem X0 to a φ, but why does the prefix itself also become a φ? This would be expected under Strict Layering (Selkirk 1984; Nespor and Vogel 1986), the dominant theory of the 1980s and 1990s, but given Weak Layering (Ito and Mester 1992) and current understanding of OT prosodic hierarchy theory as espoused in this paper, we now need a separate explanation for why phrasal affixes, such as/mo’to/, surface themselves as a full (minimal) φ (64a), and not just as a foot (64b).

Specific constraints such as EqualSisters (Myrberg 2013) or StrongStart (Selkirk 2011) could be appealed to for these cases, but would not be viable in the overall analysis of Japanese compounds. What seems to be required, then, is that such phrasal prefixes, in addition to prosodically subcategorizing a φ on its right, are also themselves subcategorized to project a φ (somewhat reminiscent of proposals in Bennett et al. 2018). Horizontal prosodic subcategorization overrides the regular length requirement on second member observed by biphrasal compounds (see (54)), and vertical subcategorization ensures that the accented prefix is itself a φ[+min].

Another case of biphrasal compounds that does not arise from prosodic (length) factors is found in a cross-linguistically rare type of post-syntactic compounding in Japanese first explored by Shibatani and Kageyama (1988). They involve verbal nouns (VNs), a class of words combining properties of both nouns and verbs most often seen with the semantically empty verb -suru “to do” carrying tense, as in benkyooˉ-suru “to study”, lit. “studying-do” or dora’ibu-suru “drive”, lit. “driving-do” (see Grimshaw and Mester 1988 for examples and analysis). VNs are mostly Sino-Japanese, but native items and western loans are also found,20 and can form compounds with one of its argument nouns (akin to noun incorporation).

What is noteworthy about compounds headed by a verbal noun (+V, +N) is the fact that there are typically two possible phonological mappings. First, as a noun (+N), it gives rise to the by now familiar ω-compound (65), with initial accent on the second member, and loss of accent on the initial member.

| (65) | ω-compounds | |||

| a. [ω [ωyooroppa][ωryo’koo]] | as simplex ω’s: | [ωyooro’ppa] | [ωryokooˉ] | |

| “European tour” | “Europe” | “trip” | ||

| b. [ω [ωamerika] [ωho’omon]] | [ωamerika ˉ] | [ωhoomonˉ] | ||

| “visit to America” | “America” | “visit” |

Secondly, as a verb (+V) and when followed by elements denoting various notions of time relations (such as -chuu “while”, -go “after”, -no sai “on the occasion of”), it results in a (biphrasal) φ-compound with independent tonal phrasal profiles on each member (66), inherited from the simplex ω profile. Each compound member forms a minimal phonological phrase with an initial rise and, if accented, with an accentual fall. The boundary between the compound members is typically marked by a phonetic break (indicated by “:”).

| (66) | φ-compounds |

| a. [φ [φyooro’ppa]:[φryokoo(-chuu)ˉ ] ] | |

| Europe trip-middle | |

| “in the middle of/while traveling in Europe” | |

| b. [φ [φamerikaˉ ]:[φhoomon(-chuu)ˉ ] ] | |

| America visit-middle | |

| “in the middle of/while visiting America” |

Only the φ-compounds have a syntactic source, with the time elements cliticized to the second member. Illustrative examples are shown in (67)–(69), with their syntactic sources showing full case markings.

| (67) | a. [yooro’ppa: ryokooˉ]-chuu |

| Europe trip middle | |

| “while traveling Europe” | |

| b. NP[yooro’ppa-o] [ryokooˉ] -chuu | |

| Europe-acc trip middle | |

| “while traveling Europe” | |

| (68) | a. [daigakuˉ: nyuugakuˉ] -go |

| university entrance -post | |

| “after entering the university” | |

| b. NP[daigaku-niˉ] [nyuugakuˉ] -go | |

| university-dat entrance -post | |

| “after entering the university” | |

| (69) | a. [ka’zan: bakuhatsuˉ] -no sai |

| volcano eruption -gen occasion | |

| “in case the volcano erupts” | |

| b. NP[kazan-gaˉ] [bakuhatsuˉ] -no sai | |

| volcano -nom eruption -gen occasion | |

| “in case the volcano erupts” |

Shibatani and Kageyama (1988, pp. 460–67) show in detail that, while undeniably derived from a sentential source, postsyntactic compounds (67)–(69) are syntactically words and not phrases, and share many syntactic properties with ordinary lexical compounds: Exclusion of case particles and tense, morphological integrity (e.g., no parentheticals), restriction to binary branching, complement selection governed by the First Sister Principle (Roeper and Siegel 1978), and lexical idiosyncrasies due to lexical stratification (such as native/non-native). These are similar to the criteria for phrasal affixes discussed above (60), and prosodically, they also have a biphrasal structure (without any length restrictions seen in the more phonologically motivated formation of φ-compounds in Section 2.3.2. How these (postsyntactic) φ-compounds exactly arise is beyond the scope of this investigation, but one might surmise that the syntax–prosody constraint mapping XP to φ is also crucially involved in this case. Descriptively, just as for the case for phrasal affixes above, we can stipulate that in these constructions the verbal noun subcategorizes for a phonological phrase, and is in addition lexically specified to project a phonological phrase itself: ryokkooˉ (VN, …, [φ][φ_]). Like all appeals to subcategorization, this is of course no more than a description of the observation, not an explanation. We hypothesize that a more principled approach will derive the characteristic prosodic frame of postsyntactic compounds from the syntactic origin of the construction, perhaps marked in the input to the phonology proper by means of syntactic phrasing that is visible to Match-constraints. Needless to say, a much more thorough investigation is necessary, building on the seminal work by Shibatani and Kageyama (1988).21

3. Conclusions

Taking stock of our main findings, we have encountered both adjunctive and coordinative ω-compounds in Danish and Japanese (70a–d).

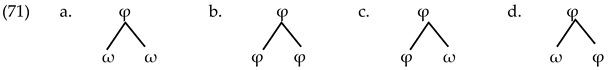

In addition, two kinds of coordinative φ-compounds are found in Japanese, one with a non-recursive (strictly layered) structure (71a), and one with coordinative recursion (71b). The question naturally arises whether there are also adjunctive types of φ-compounds (71cd), analogous to the ω-compounds in (70cd).

Further investigation of Japanese—and cross-linguistically—is clearly warranted, but a likely case of φ[ωφ]-compounds exists in Kyoto Japanese, which is characterized not only by accent (such as Tokyo Japanese), but also by an additional tonal register distinction. Angeles (2020) argues that what Nakai (2002) calls hukanzen hukugoogo “incomplete compounds” are instantiations of φ[ωφ]-compounds: The first compound member retains its register but loses its accent, and should hence be analyzed as ω; the second member retains both register and accent, testifying to its status as a φ.

In conclusion, admitting recursive prosodic structures in our theory makes it possible to give a unified account of the prosodic typology of Japanese compounds, encompassing junctural accent in ω[ωω] and ω[fω]-compounds (44), preaccentuation in ω[ωf]-compounds (46a), and unaccentedness in ω[ff]-compounds (40), which emerges here in the same way, and for the same reasons, as in simplex 4μ-words (38). Reference to head yields the MatchHead constraint, the BinMaxHead constraint (52) limiting the size of a ω-compound head. Reference to maximal and minimal projections provides the distinction between WordMaxAccent (42b), the traditional “compound accent”, and WordAccent (42a), the accent on φ[+min]. We also find, besides the WordBinarity constraint (24), other types of binarity constraints on different projections, BinMax-φ[+min] (57) and BinMaxHead(ω[+max, −min]) (52). Stipulating a host of separate prosodic categories to represent this typology of prosodic structures would only serve to obscure this unified picture.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, J.I. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation Grant No. 1749368.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article and in published references cited therein.

Acknowledgments

Earlier versions of this research were presented at RecPhon 2019: Recursivity in phonology, below and above the word, November 2019, in Barcelona, at NINJAL ICPP6 (National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics) International Conference on Phonetics and Phonology, December 2019, in Tokyo, and at the SOTA IV workshop (Society for Typological Analysis), January 2020, in St. Petersburg, Florida. We would like to thank the organizers for administrative support and the participants for insightful comments and questions. Finally, we are grateful to the editors and two anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Constraints Used in this Paper

| Syntax–prosody mapping | Match (X0, ω): Assign one violation for every terminal node X0 in the syntax such that the segments belonging to X0 are not all dominated by the same prosodic word ω in the output. (10), Section 2.3. |

| MatchHead: Match (X0head, ω). Assign one violation for every terminal node X0 in the syntax that is a head such that the segments belonging to X0 are not all dominated by the same prosodic word ω in the output. (27), Section 2.3.1. | |

| Accent | WordAccent: A prosodic word contains a prominence peak. Violated by prosodic words not having a prominence peak. (42a), Section 2.3.1. |

| WordMaxAccent: A maximal prosodic word [+max, -min] contains a prominence peak. Violated by maximal prosodic words not having a prominence peak. (42b), Section 2.3.1. | |

| RightmostGlottalAccent: The accented foot is the rightmost foot in the prosodic word. Violated when a foot intervenes between the accented foot and the end of the prosodic word. (18), Section 2.2. | |

| NonFinality(Ft’): * Ft’]ω Violated by any head foot that is final in its PrWd […]—”final” in the sense that the right edge of Ft’ coincides with the right edge of PrWd (Ito and Mester 2016, p. 485). | |

| Binarity | WordBinarity: Prosodic words must be binary. Violated by words measuring no more than a single foot. (24), Section 2.2. |

| BinMaxHead(ω[+max, −min]): Heads of prosodic words that are maximal and non-minimal are maximally binary. Violated if the head has more than two immediate daughters. (52), Section 2.3.2. | |

| BinMax-φ[+min]: Minimal φ are maximally binary. Violated if minimal φ dominates more than two (minimal) ω’s. (57), Section 2.3.2. | |

| Foot parsing | InitialFoot: A prosodic word begins with a foot […]. Violated by any prosodic word whose left edge is aligned not with the left edge of a foot, but of an unfooted syllable (Ito and Mester 2016, p. 485). |

| ParseSyllable: All syllables are parsed into feet […]. One violation for every unfooted syllable (Ito and Mester 2016, p. 485). |

References

- Ackema, Peter, and Ad Neeleman. 2004. Beyond Morphology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Angeles, Andrew. 2020. Word and Phrase Projections in Kyoto Japanese Compounds. Santa Cruz: UC Santa Cruz. [Google Scholar]

- Aoyagi, Seizô. 1969. A demarkative pitch of some prefix-stem sequences in Japanese. Onsei no kenkyû, 241–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Laurie. 2011. Typology of compounds. In The Oxford Handbook of Compounding. Edited by Rochelle Lieber and Pavol Štekauer. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 540–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellik, Jennifer, and Nick Kalivoda. 2018. Prosodic recursion and pseudo-cyclicity in Danish compound stød. In Hana-bana (花々): A Festschrift for Junko Ito and Armin Mester. Edited by Ryan Bennett, Andrew Angeles, Adrian Brasoveanu, Dhyana Buckley, Nick Kalivoda, Shigeto Kawahara, Grant McGuire and Jaye Padgett. Santa Cruz: eScholarship, Linguistics Research Center, University of California, pp. 71–85. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/09m654fp (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- Bennett, Ryan. 2018. Recursive prosodic words in Kaqchikel (Mayan). Glossa 3: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Ryan, Boris Harizanov, and Robert Henderson. 2018. Prosodic smothering in Macedonian and Kaqchikel. Linguistic Inquiry 49: 195–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canepàri, Luciano. 1999. Il Di Pi—Dizionario di pronuncia italiana. Bologna: Zanichelli. Available online: http://www.dipionline.it/dizionario/ (accessed on 15 February 2020).

- Chomsky, Noam. 1965. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dardano, Maurizio, and Pietro Trifone. 1995. Grammatica Italiana. Bologna: Zanichelli. [Google Scholar]

- Elfner, Emily. 2012. Syntax-Prosody Interactions in Irish. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw, Jane, and Armin Mester. 1988. Light verbs and theta-marking. Linguistic Inquiry 19: 205–32. [Google Scholar]

- Guekguezian, Peter Ara. 2017. Templates as the interaction of recursive word structure and prosodic well-formedness. Phonology 34: 81–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzo, Natália Brambatti. 2018. The prosodic representation of composite structures in Brazilian Portuguese. Journal of Linguistics 54: 683–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, Hubert. 1993. Deutsche Syntax—Generativ. Vorstudien zur Theorie einer projektiven Grammatik. Tübingen: Gunter Narr. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Bruce. 1989. The prosodic hierarchy in meter. In Rhythm and Meter. Edited by Paul Kiparsky and Gilbert Youmans. Orlando: Academic Press, pp. 201–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hulst, Harry van der. 2010. A note on recursion in phonology. In Recursion and Human Language. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 301–42. [Google Scholar]

- Inkelas, Sharon. 1989. Prosodic Constituency in the Lexicon. Ph.D. dissertation, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara, Shinichiro. 2015. Syntax-phonology interface. In Handbook of Japanese Phonetics and Phonology. Edited by Haruo Kubozono. Berlin: De Gruyter, Mouton, pp. 569–618. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, Junko, and Armin Mester. 1992. Weak layering and word binarity. In A New Century of Phonology and Phonological Theory. Edited by Honma Takeru, Masao Okazaki, Toshiyuki Tabata and Shin-ichi Tanaka. Tokyo: Kaitakusha, pp. 26–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2007. Prosodic adjunction in Japanese compounds. In Formal Approaches to Japanese Linguistics: Proceedings of FAJL 4. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 55. Edited by Yoichi Miyamoto and Masao Ochi. Cambridge: MIT Department of Linguistics and Philosophy, pp. 97–111. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2012. Recursive prosodic phrasing in Japanese. In Prosody Matters. Essays in Honor of Elisabeth Selkirk. Edited by Toni Borowsky, Shigeto Kawahara, Mariko Sugahara and Takahito Shinya. Sheffield and Bristol: Equinox, pp. 280–303. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2013. Prosodic subcategories in Japanese. Lingua 124: 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2015. The perfect prosodic word in Danish. Nordic Journal of Linguistics 38: 5–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2016. Unaccentedness in Japanese. Linguistic Inquiry 47: 471–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2018. Tonal alignment and preaccentuation. Journal of Japanese Linguistics 34: 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, Taro. 1982. Word formation in Japanese. Lingua 57: 215–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, Taro. 2016. Noun compounding and noun incorporation. In Handbook of Japanese Lexicon and Word Formation (Handbooks of Japanese Language and Linguistics). Edited by Taro Kageyama and Hideki Kishimoto. Boston and Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, vol. 3, pp. 237–72. [Google Scholar]

- Krämer, Martin. 2009. The Phonology of Italian. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kubozono, Haruo. 1988. The Organization of Japanese Prosody. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Edinburgh, Department of Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Kubozono, Haruo. 1989. Syntactic and rhythmic effects on downstep in Japanese. Phonology 6: 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubozono, Haruo. 1995. Constraint interaction in Japanese phonology: Evidence from compound accent. In Phonology at Santa Cruz [PASC]. Edited by Rachel Walker, Ove Lorentz and Haruo Kubozono. Santa Cruz: Linguistics Research Center, UC Santa Cruz, pp. 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kubozono, Haruo, Junko Ito, and Armin Mester. 1997. On’inkōzō-kara mita go-to ku-no kyōkai: Fukugō-meishi akusento-no bunseki [The word/phrase boundary from the perspective of phonological structure: The analysis of nominal compound accent]. In Bunpō-to onsei. Speech and Gramma. Edited by Spoken Language Research Group. Tokyo: Kurosio Publications, pp. 147–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd, D. Robert. 1986. Intonational phrasing: The case for recursive prosodic structure. Phonology 3: 311–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, D. Robert. 1988. Declination “reset” and the hierarchical organization of utterances. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 84: 530–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Paricio, Violeta, and René Kager. 2015. The binary-to-ternary rhythmic continuum in stress typology: Layered feet and non-intervention constraints. Phonology 32: 459–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCawley, James D. 1968. The Phonological Component of a Grammar of Japanese. The Hague: Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Lübke, Wilhelm. 1890. Italienische Grammatik. Leipzig: O. R. Reisland. [Google Scholar]

- Myrberg, Sara. 2013. Sisterhood in prosodic branching. Phonology 30: 73–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, Yukihiko. 2002. 京阪系アクセント辞典 [keihan-kei akusento jiten; Keihan-type Accent Dictionary]. Tokyo: Bensei Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Nespor, Marina, and Irene Vogel. 1986. Prosodic Phonology. Dordrecht: Foris. [Google Scholar]

- Peperkamp, Sharon. 1997. Prosodic Words. The Hague: Holland Academic Graphics. [Google Scholar]

- Pierrehumbert, Janet, and Mary Beckman. 1988. Japanese Tone Structure (LI Monograph Series No. 15). Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pinker, Steven, and Ray Jackendoff. 2005. The nature of the language faculty and its implications for evolution of language (reply to Fitch, Hauser, & Chomsky). Cognition 97: 211–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poser, William J. 1990a. Evidence for foot structure in Japanese. Language 66: 78–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poser, William J. 1990b. Word-internal phrase boundary in Japanese. In The Phonology-Syntax Connection. Edited by Sharon Inkelas and Draga Zec. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, pp. 279–87. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, Alan S., and Paul Smolensky. 2004. Optimality Theory: Constraint Interaction in Generative Grammar. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Recasens, Daniel. 2013. On the articulatory classification of (alveolo)palatal consonants. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 43: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeper, Thomas, and Muffy E. A. Siegel. 1978. A lexical transformation for verbal compounds. Linguistic Inquiry 9: 199–260. [Google Scholar]

- Selkirk, Elisabeth. 1984. Phonology and Syntax: The Relation between Sound and Structure. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Selkirk, Elisabeth. 1996. The prosodic structure of function words. In Signal to Syntax. Edited by James L. Morgan and Katherine Demuth. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 187–213. [Google Scholar]

- Selkirk, Elisabeth. 2011. The syntax-phonology interface. In The Handbook of Phonological Theory, 2nd ed. Edited by John Goldsmith, Jason Riggle and Alan Yu. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 435–85. [Google Scholar]

- Selkirk, Elisabeth, and Seunghun J. Lee. 2015. Constituency in sentence phonology: An introduction. Phonology 32: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibatani, Masayoshi, and Taro Kageyama. 1988. Word Formation in a Modular Theory of Grammar: Postsyntactic Compounds in Japanese. Language 64: 451–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinya, Takahito, Elisabeth Selkirk, and Shigeto Kawahara. 2004. Rhythmic boost and recursive minor phrase in Japanese. In Speech Prosody 2004. Edited by Bernard Bel and Isabelle Marlien. Nara, Japan: ISCA Archive, pp. 345–48. [Google Scholar]

- Trips, Carola, and Jaklin Kornfilt. 2015. Typological aspects of phrasal compounds in English, German, Turkish and Turkic. In Phrasal Compounds from a Typological and Theoretical Perspective. Special issue of STUF. Edited by Carola Trips and Jaklin Kornfilt. Berlin: Language Science Press, pp. 281–321. [Google Scholar]

- Vigário, Marina Claudia. 2010. Prosodic structure between the prosodic word and the phonological phrase: Recursive nodes or an independent domain? The Linguistic Review 27: 485–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, Irene. 2009a. Universals of prosodic structure. In Universals of Language Today. Edited by Sergio Scalise, Elisabetta Magni and Antonietta Bisetto. New York: Springer, pp. 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, Irene. 2009b. The status of the Clitic Group. In Phonological Domains: Universals and Deviations. Edited by Janet Grijzenhout and Barış Kabak. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 15–46. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | If recursion exists at lower levels of prosody that are not strictly interface-grounded (see Martínez-Paricio and Kager 2015), such as feet, syllables, or even segments, this is probably different. |

| 2 | Recursive ω-prosody triggered by syntactic cyclicity, as proposed by Guekguezian (2017, p. 82), is promising as a sufficient condition for recursive ω-structure, but it is unlikely to be a necessary condition. For example, Bennett (2018, pp. 13–16) shows in detail that the prefixes in Kaqchikel (Mayan) that give rise to recursive ω-structure have the same morphosyntax as the prefixes that do not. |

| 3 | The first author is a native speaker of Japanese. The Danish examples first appeared in an earlier publication (Ito and Mester 2015) and were checked by native speakers and by reviewers of the journal. All Kaqchikel examples are taken from Bennett (2018). They go back to descriptive grammars and dictionaries of Kaqchikel written by native-speaker linguists and to Bennett’s own fieldwork. |

| 4 | Our glosses follow the Leipzig glossing rules (https://www.eva.mpg.de/lingua/resources/glossing-rules.php, accessed on 16 March 2021), in particular: ABS = “absolutive”, COM = “comitative”, AGT = “agentive”. |

| 5 | Orthographically, gl preceding the vowel i. Italian [ʎ] is actually alveolo-palatal (Recasens 2013) and intervocalically always long (“in posizione intervocalica, soltanto articulazione intensa” (Dardano and Trifone 1995, p. 675)). |

| 6 | From Latin illī (“[i]n der Proklise ist die tonlose erste Silbe verloren gegangen” according to Meyer-Lübke 1890, p. 210). Krämer (2009, pp. 46–47) points out that, together with its variant glie found in the combinations glielo, gliela, glieli, gliele, and gliene, gli is in fact the only clitic with initial [ʎ] in standard Italian, weakening the probative force of this case. Krämer also notes that all other occurrences of word-initial [ʎ] found in Canepàri’s (1999) exhaustive dictionary are either loans, personal names, such as Glielmo (a shortening of Guglielmo = Wilhelm, William), or dialect words, such as the Neapolitan dialect poem gliommero. |

| 7 | We use IPA diacritics for stress, length, and stød, but present the words otherwise in Danish orthography since details of pronunciation are not relevant here. |

| 8 | We are assuming that there is a (violable) constraint requiring words to carry a glottal accent, see Ito and Mester (2015, pp. 14–15) for details and justification. Since the glottal accent can only appear on sonorous second moras of heavy syllables (the so-called “stød-basis”) and not every word has such a syllable in the right position, the word accent constraint is dominated by the constraints enforcing the stød-basis, with the result that the glottal accent often goes unrealized. |

| 9 | It is important to be clear about the difference between glottal accent and compound stress: The latter is always on the first word, even when the glottal accent only appears on the last foot of the second word. The two therefore do not coincide in cases like (21a) ˈtoːg passaˌgeːʔr. |

| 10 | There are exceptions to stød-loss, such as the stereotypical example of stød in the phrase rødgrød med fløde “red porridge with cream” used as a shibboleth in World War II, according to legend. These cases are lexicalized as two prosodic words: [ω [ω(ˈrøʔd)] [ω(ˌgrøʔd)] ]. A number of monosyllabic words behave in this way as first compound members. |

| 11 | The analysis in Ito and Mester (2015) posits four possible combinations, long–long, short–short, short–long, long–short (where short = one foot, long ˃ one foot), with different prosodic representations. The analysis proposed here is simpler while taking compound stress accent into account, as discussed below. |

| 12 | Besides MatchHead, high-ranking Exhaustivity (Parse-f-into-ω) also ensures ω-hood for these non-compound simplex word cases. We will see this constraint interaction at work in Japanese, where MatchHead is lower ranked. |

| 13 | We are grateful to the audience at the RecPhon workshop in Barcelona in November 2019, in particular, Heather Newell, for pointing out the relevance of the compound stress facts for our analysis. |

| 14 | We adopt the modified Hepburn romanization used by the Kenkyusha dictionary, except for long vowels indicated by double vowels rather than a macron. |

| 15 | This is not to say that ff-compounds have exactly the same properties as simplex words: They differ in morphosyntactic structure, and there are morphophonemic processes such as compound voicing (rendaku) that apply to ff-compounds (as to other compounds) but not to simplex words. |

| 16 | “Peak” here means primary stress or pitch accent, in Japanese: High*͡ Low. |

| 17 | Accent falls on the first mora of the last syllable in chiho’o zei because of the AccentToSyllableHead constraint (see Ito and Mester 2018, p. 202). |

| 18 | The reference to [+max, −min] means that the restriction applies to compound words and does not apply to simplex prosodic words. |

| 19 | Two recent coinages with moto truncate their second members down to two moras and become unaccented: moto kareˉ (from mo’to ka’reshi “ex-boyfriend”) and moto kanoˉ (from [mo’to ka’nojo] “ex-girlfriend”). This is the expected pattern for two-foot ω-compounds, as in (40). |

| 20 | For further analysis and references to more recent work, see Kageyama (2016), who also notes that there are similar postsyntactic compounds headed by adjectival nouns such as huju’ubun “inadequate”: [shi’ngi: fuju’ubun] ni tsuki [discussion inadequate] DAT due to “due to the fact that the discussion is inadequate”. |

| 21 | A reviewer points out that similar compound formations exist in Turkic languages, as discussed in Ackema and Neeleman (2004), Trips and Kornfilt (2015), among others. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).