Abstract

Despite the extensive body of research on the social aspects of humor, relatively few studies consider humor as an active element in the formation of linguistic structure (in the structuralist sense). In this regard, the present paper explores the role of humor in the diachronic evolution of qué…ni que-insubordinate structures in Contemporary Spanish and outlines a possible integration of humor into an interactive construction grammar (Croft, 2001).

1. Introduction

In 1922, German linguist Leo Spitzer published Italienische Umgangssprache (Italian Spoken Language) (), which described the structure of spoken Italian. Seven years later, his pupil Werner Beinhauer wrote a follow-up, Spanische Umgangssprache (Spanish Spoken Language) (). Given the similarity of the research focus, Beinhauer questioned the necessity of a second publication. He concluded that some mechanisms were strikingly more active in spoken Spanish than in Italian, and he pointed to humor as one of these mechanisms.

This observation might at first seem curious. After all, Italian and Spanish are neighboring languages, share a common culture, and in both societies humor is an active element in everyday life. Although humor has been acknowledged as an active device for lexical creation, Beinhauer’s remark poses an interesting research question: Does humor play an active role in creating, propagating, and disseminating linguistic constructions? Otherwise said, is humor an active mechanism in constructionalization processes?1

To illustrate, let us begin with an illustrating example. The first lunch in an international conference was especially disappointing: a sandwich containing only some green leaves and nothing else inside. Waving the sandwich, an Italian friend approached me with a grin on her face and asked me, “Well, my friend, what do you think about the sandwich?” My answer was: Pues que en peores plazas hemos toreado (lit.: Well, in worse arenas we have fought). To make her understand the irony in my reply, I had to activate some scripts, including bullfighting, post-war Spain, a context of misery, third-class arenas in small villages, overcoming poor expectations and the comparison between present and past states of affairs. This not being enough, some contexts of use were necessary to make her understand when and how this expression was used; for example, if two friends are talking about a one-night stand and one asks how that guy was like, the friend might answer “en peores plazas hemos toreado”. When my friend started laughing, I realized that old Beinhauer might be right in suggesting that there was something special about the role of humor in Spanish.

The role of humor in this example lies closer to what () referred to as a speaker’s dictionary. This paper intends to go one step further by considering the role of humor in a speaker’s grammar, with a focus on a very specific set of constructions: Spanish qué…ni qué constructions (henceforth, Q/NQ.Cxn). The perspective adopted is diachronic, focusing on the development of these constructions—that is, on constructionalization processes ().

2. Setting the Problem: Goals and Theoretical Background

2.1. Goals

This paper analyzes the diachronic development of a set of interrogative and insubordinate constructions, grouped together under the umbrella term Q/NQ Cxns. These include the following:

| 1. ¡Qué X ni qué ocho cuartos! |

| (Lit. What-X-nor-what-sixteen-shillings! ‘What X, what nonsense’) |

| 2. ¡Qué X ni qué niño muerto! |

| Lit. What X-nor-what-dead-child! ‘What X, what nonsense’) |

Examples (3) and (4) illustrate their usage as follows:

| 3.—[…] Pues señor, bien… ¿Y qué va uno ganando con ser Mecenas? |

| — La gloria… |

| — Como quien dice, el beneplácito… |

| — ¿Qué beneplácito, ni qué niño muerto? La gloria, hombre. (CORDE [29/12/2024] Galdós, 1894). |

| — […] Well, sir, quite so… And what does one gain, pray, by being a Patron? |

| — Glory… |

| — Glory, is it? As they say, mere approbation, perhaps? |

| — Approbation! What approbation, or what childish nonsense is this? Glory, man!” |

| 4. “¡La merienda! ¡La merienda!” esta es la voz general, incesante, atronadora. |

| — ¡Callad, enemigos, callad, que ya voy! dice la pobre Dolores apartando de sí la sábana que estaba dobladillando, y sacando del aparador una compotera, pan, platos y cucharillas. |

| Así que cada cual despachó su racion, no escasa por cierto, la gritería volvió á repetirse. |

| — ¡Ahora el cuento! ¡Ahora el cuento!… |

| — ¡Qué cuento ni qué ocho cuartos!.. (CORDE [29/12/2024] Coello, 1872). |

| “‘Tea-time! Tea-time!’—such was the universal, incessant, deafening cry. |

| ‘Be quiet, you wretches, be quiet, I am coming!’ exclaimed poor Dolores, as she hastily set aside the piece of linen she was hemming, and began to take down from the cupboard a compote dish, bread, plates, and spoons. |

| And so, when each had dispatched their portion—by no means a scant one, to be sure—the clamour once more began to rise. |

| ‘Now, the story! Now, the story!’ |

| ‘What story, what nonsense!’” |

The historical evolution of (1) and (2) cannot be properly accounted for without taking into account a broader context. Indeed, Q/NQ.Cxns do not stand alone as an isolated family in the constructicon but are part of a deeply intertwined set of related insubordinate constructions. To properly account for Q/NQ.Cxns it is necessary also to consider higher-level constructions (like QUE.Cxns or NI. Cxns) and neighboring constructions (like NI+INF.Cxns). The following is a non-exhaustive list of such constructions:

| 5. ¡Qué X ni (qué) X’! | 9. ¡Como X! |

| (What X or X’!) | (How X!) |

| 6. ¡Qué IR a +V! | 10. ¡Como si X! |

| (What- V-ing!) | (Like-if-X!) |

| 7. ¡Ni que X! | 11. ¡Con la de X! |

| (Nor-that-X!) | (With-so-many -X!) |

| 8. ¡Ni X ni Y! | 12. ¡Si X! |

| (Not-X-nor-Y!) | (If X!) |

This complex, blurred-border set of constructions inhabits a broad domain, where all members are linked together by family resemblance. Five general linguistic features are at play in this domain, with different weights for each case: insubordination, construction, humor, constructionalization processes and interaction. The following section will delve deeper into each of them.

2.2. Theoretical Background

2.2.1. Insubordination

Constructions (1) and (2) are instances of insubordination (; ; ; ; ). Ni is a coordination conjunction, and qué is the stressed counterpart of the unmarked complementizer que, the par excellence complementizer in Spanish (; ). In the above examples, ni and que are freed from a main clause and stand alone in very specific contexts, associated with meanings that cannot be explained as instances of their grammatical counterparts (, ; ). Specifically, these constructions express disagreement, which can be included in ’ () second macro-function of insubordination, that of modal qualification. In the broad vs. narrow approaches to insubordination (), the constructions studied in this paper are better accounted for within a broad approach, as their interactional features are key to understanding why and how they are used.2

Diachronically, the question arises as to whether the rise in insubordination is due to the loss of the main clause () or is the result of incremental contributions in interactive environments ().

Insubordination studies shed light on the special character of these constructions and on the formal, semantic and pragmatic features they convey. Insubordination provides a template for the constructions under study to emerge and spread.

2.2.2. Construction Grammar

Construction grammar (CxG) provides the most comprehensive explanation for (1) and (2), as CxG offers the possibility to merging the prosodic, syntactic, pragmatic and even positional features of any construction into two poles, form and meaning, while prompting the researcher to establish as many links as possible among them. What in other approaches is seen as different, unrelated features, here is seen as part of a broader, unified picture—precisely what is needed to turn the constructions in Table 1 below into a meaningful structure.

Table 1.

vertical and horizontal relationships among constructions.

Among the different construction grammars available3 in the linguistic domain, this paper adopts an interactive construction grammar (henceforth, ICG), in its synchronic (; ) and diachronic versions (). ICG is more pragmatically oriented and especially well-suited to the study of spontaneous conversations. It has also previously been applied to diachronic studies.

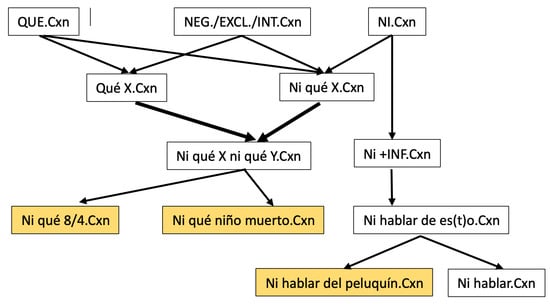

An important feature of CxG is the possibility of establishing links among constructions. In this sense, (1) and (2) are complex constructions, conceived as the merger of simpler constructions. To properly understand (1) and (2), vertical and horizontal relationships have to be established. Along the vertical axis, higher-level (EXCL.CNX, INT.CXN, NEG.CXN, or INSUB.CXN),medium-level (NI.CXN, QUÉ.CXN) and lower-level constructions (ni qué historias, ni qué cojones—) are taken into account (See Section 5.1 for a discussion on the types of relationship linking these different levels).

This vertical axis is necessary, but not sufficient, to provide a complete constructional account. Horizontal relationships must also be studied: for instance, on a lower level, nearby constructions (ni que le debiera dinero, ni hablar del peluquín) show similar—and, most probably, related—features to the ones studied in this paper. Paradigmatic relationships among them could lead to joint diffusion, transfer of traits, or shared contexts of use.

Table 1 provides a non-exhaustive representation of the vertical and horizontal relationships among related constructions:

2.2.3. Humor Studies

Moving to the meaning pole of the constructions studied, humor is found as a core ingredient in both examples; therefore, (1) and (2)can be said to be, in a greater or lesser degree, instances of a more general HUMOR.CXN. A comprehensive account of humor studies far exceeds the limits of this paper. The most widespread theory of humor is the General Theory of Humor (; ), although there are alternative explanations within Relevance Theory (; ). CxG, in turn, accounts for humor in Construction Discourse (; ; ).

Although humor studies have focused primarily on certain discourse types, such as jokes, monologues or stand-up comedy, there is a growing interest in interactional—or situated—humor (; ; ; ), where the interactional cues surrounding humorous texts contextualize, determine and enhance or prevent further humor. Of particular interest is the study of spontaneous conversations conducted by the GRIALE group (, , ; ; ; ; ; ). () has studied interactional humorous expressions as instances of mock impoliteness (). In mock impoliteness, a construction showing an aggressive humorous style is perceived as non-impolite and, as a result, produces in-group bonding. The ni qué niño muerto construction, described synchronically by (), would be one such example.

Thinking diachronically about the ni qué niño muerto construction, it is hard to imagine how references to a dead child could become conventionalized in Spanish; it is even harder to imagine routinization starting from its literal meaning (i.e., a reference to an actual dead child). However, if this image is evoked ironically, routinization becomes possible, as the dramatic nuances of this linguistic expression are erased (see Section 6.1).

(1) and (2) are not the only examples where humor is conventionalized. The following Ni- constructions cannot be understood as serious uses of language, either:4

| 13. ¡Ni es que ni es ca! |

| (Nor-it-is-that-MASC-nor-it-is-that-FEM) |

| 14. ¡Ni que lo regalaran! |

| (Nor-would-them-give-it-away!) |

(13) is a father’s typical reaction against a child excuse (prefaced by es que—lit. It-is-that), as in example (15):

| 15. Father: ¿Por qué no has hecho los deberes? |

| Why didn’t you do your homework? |

| Daughter: Es que… |

| Well… |

| Father: ¡Ni es que ni es ca! |

| No well, young lady, no well |

(14) is a counterfactual construction evoking an unlikely circumstance as an unrealistic cause to explain an unexplainable fact, as in (16)5:

| 16. A: Menuda cola para el pan. ¡Ni que lo regalaran! |

| What a line to buy bread. As if they were giving it away! |

In (16), speaker A considers it exaggerated that so many people stand in line to buy bread. This could only be explained by the counterfactual state of affairs in which bread was given for free, something that is obviously false.

In sum, humor is a powerful reason for a construction to stay alive. (See Section 6.2 for a discussion of the role of humor in the development of (1) and (2)).

2.2.4. Constructionalization Studies

This paper adopts a diachronic perspective as a necessary approach to understand the constructions studied in this paper. While synchronic descriptions provide answers to what constructions are, how are their constituents put together, and where they can be used, the most basic question, why they became a construction, is not addressed. For the goals of this paper, a diachronic approach is not just a heuristic choice, but a descriptive necessity.

In line with the work by Elizabeth Traugott (; ; ; ), a diachronic study of Q/NQ.Cxns must take into account pre- and post-constructionalization changes, as well as the intersubjective processes whereby conversational implicatures are conventionalized and expand across a linguistic community () (see Section 4.2 and Section 4.3). A proper diachronic account of these constructions must also include the role of humor in the routinization, dissemination and replication of Q/NQ.Cxns (see Section 6.2). Few studies have addressed the link between Humor and diachrony, with () or () among the few exceptions.

2.2.5. Interaction Studies

A fifth and final feature of this set of constructions is their interactive nature (; ; ). In fact, these constructions are used exclusively in spontaneous conversations (or in written samples mimicking orality—; ) under strict conditions of use:

First, (1) and (2) are refutative; that is, are used exclusively to show disagreement with what a previous speaker has said.

As refutative structures, they are reactive (that is, they occur as second-parts in a turn constructional unit –TCU–).

This means that a speaker cannot start a conversation with Q/NQ.Cxns; in other words, these constructions cannot occur in absolute initial position ().

Not only are they reactive, but they are also linked to its immediate context, namely to the preceding speaker’s utterance6. In this sense, the minimal discourse unit needed to understand (1) and (2) is the adjacency pair or, in Val.Es.Co terms, the exchange ().

The five domains addressed in this section partially overlap (humor-Cxn; humor-interaction; Cxn-constructionalization, and so on). Each intersection provides insight into the complex nature of the constructions studied in this paper.

From the description above, the study of Q/NQ.Cxns emerges as a fascinating crossroads of structures, theories and levels of analysis. This paper aims to explore the following synchronic and diachronic hypotheses:

- There is a degree of entrenchment among the constructions (1) to (12)

- This entrenchment can only be properly accounted for through a diachronic approach

- The spread of some lower-level constructions was fostered by the vitality of sister constructions

- The driving force behind the diffusion of the oldest constructions was humor

- The vitality of lower-level constructions had an impact on higher-level constructions.

- The diachronic process of spread spans contemporary to Present Day Spanish.

This paper explores these issues by analyzing the historical development of Q/NQ.Cxns and neighboring insubordinate constructions.

3. Materials and Methods

To study Q/N.Cxns, examples from two different corpora have been retrieved: the Corpus del Diccionario Histórico (CDH), compiled by the Spanish Academy of Language (RAE) (https://www.rae.es/banco-de-datos/cdh [accessed on 1 January 2025]), and the Biblioteca Virtual de Prensa Histórica (BVPH), compiled by the Spanish Ministry of Culture (https://prensahistorica.mcu.es/es/inicio/inicio.do [accessed on 7 January 2025]).

These corpora complement each other: the CDH is a broad-spectrum, monitor corpus (ca. 300 million words), while the BVPH specializes in press and newspapers (ca. one billion words). The CDH is more oriented towards literature and to formal examples, the BVPH is more adequate for identifying reflections of orality ().

To extract the results, different search strings were used: niño muerto and ocho cuartos, ni hablar, ni hablar de eso, and ni hablar del peluquín, and collocations with open places (ni qué X ni qué). To prevent the accidental inclusion of literal expressions in the study, all searches were manually revised.

In the case of the most abstract structure ni qué…ni qué, data from the BVPH could not be retrieved due to restrictions in the BVPH search engine.

Table 2 summarizes the search results in both corpora: although the focus of research are the ni qué niño muerto and the ni qué ocho cuartos constructions, they can only be properly explained within a broader constructional environment, where other NI QUÉ.Cxn or NI.Cxn are studied: in this paper, the ni hablar del peluquín construction and the more general qué…ni qué construction will be included in the analysis.

Table 2.

NI and NI QUÉ.Cxn in the corpora.

For every construction, two types of data are retrieved: the earliest attestation (both in the CDH and in the BVPH corpora) and the number of occurrences thereafter. The earliest attestation helps reconstruct the diachronic development and the lineage of parent-to-sibling constructions. The latter informs us of their vitality.

4. A Diachronic Study of Q/NQ.Constructions

From the data above, it seems that lower-level constructions could derive from the longest, high-level QUÉ…NI QUÉ.Cxn (niño muerto/ocho cuartos/ni hablar). This hypothesis will be tested in Section 4.1, Section 4.2, Section 4.3 and Section 4.4, where a more detailed analysis of the QUÉ…NI QUÉ.Cxn is provided in (Section 4.1), along with the analysis of two lower-level constructions derived from it: ni qué ocho cuartos (Section 4.2), and ni qué niño muerto (Section 4.3). Finally, the ni hablar del peluquín construction will be analyzed in (Section 4.4) to explore the impact of indirect inheritance relationships among constructions.

For a more comprehensive account, further constructions should be studied, such as ni hablar (de eso), ni loco, or ni que Vimp.subj.Cxn (ni que fuera X, ni que hubiera X, etc.). Due to time and space restrictions, the explanation is limited to the most deeply entrenched constructions. Future research will provide a more complex view of the extended family of constructions.

4.1. (Ni) qué…ni qué > Ni qué…7

The Ni qué…ni qué.Cxn is first documented in the 16th century and seems to have evolved, in turn, from an earlier no…ni que… construction. Its first occurrences remain under the scope of a negative trigger (Sp. no), creating a negative agreement relationship () with the ni qué…ni que.Cxn, as shown in (17):

| 17. Ni qué diga ni qué ‘scriva/ ya no sé, ni qué me quiera/ no me da mi suerte esquiva /ni más mal, porque no muera/ ni menos, porque no biva. |

| Nor what to say, nor what to write/ I know not, nor what to will/ Fickle fate grants me no spite/ To let me die, nor yet goodwill/ To let me live and suffer still. |

| (CDH. 1514–1542. Boscán, Juan. Poesías) |

Simultaneously, a second, alternate construction is documented in the same time span, where ni, though next to a negative trigger, is not under its scope and functions as a negative trigger itself (within a rhetorical question). This is evident from the different modalities in the sentence hosting no (declarative) and in the sentence hosting ni (interrogative) in example (18). The ni qué…ni qué construction retains its distributive meaning:

| 18. ¿Y vosotros pensáis que os quiere más algún santo que Dios?, no por çierto; ¿ni que es más misericordioso, ni que ha más compasión de vos que Dios?, no por çierto. Pero pedíslo a los santos porque nunca estáis para hablar con Dios |

| And do you think that any saint loves you more than God? Certainly not. Or that they are more merciful or have more compassion for you than God? Certainly not. But you pray to the saints because you are never ready to speak with God (CDH. 1553–1556. Villalón, Cristóbal de. El Crótalon de Cristóforo Gnofoso) |

Finally, in a third construction (19), ni qué is no longer a distributive, but a copulative negative conjunction, having lost its second part (ni qué… ni qué > ni qué). Additionally, the preceding context (the question before ni que) is no longer negative but a rhetorical question implying a negative answer; this implied answer licenses ni in the immediate surrounding context. Therefore, the loss of the second ni and the implicit, contextual negative meaning, characterize this insubordinate NI QUÉ construction

| (19) Fulminato: ¿Y qué te he llevado yo? ¿Ni qué has hecho por mí? Cata que tus |

| pecados nuevos te traen a que pagues tus viejos vicios a mis manos |

| Fulminato: And what have I brought you? Or what have you done for me? Know that |

| your new sins are bringing you to pay for your old vices into my hands (CDH. 1554. |

| Rodríguez Florián, Juan. Comedia llamada Florinea) |

During the 17th century, the interrogative ni qué construction loses its link with a negative environment. In turn, it strengthens bounds with the preceding interrogative question, thus creating a complex construction: ¿CÓMO/QUÉ…? ¿NI QUÉ …?

| 20. ¿Cómo podré vivir sin comer? ¿Ni qué me dará quien me quita el pan cotidiano y el agua de mis refrigerios? ¿Qué vida será la mía si me privan de todo lo que me daba gusto en ella? |

| How shall I live without eating? Nor what shall he give me who taketh away my daily bread and the water of my refreshments? What life shall be mine if they deprive me of all that gave me joy therein? (CDH. 1598. Fray Alonso de Cabrera. De las consideraciones sobre todos los evangelios de la Cuaresma) |

This complex construction is profusely used during the late Baroque (1600–1650) and the first half of the 18th century. Around 1730, minor pre-constructional changes in modality arise, as this construction is documented in exclamative sentences. Notwithstanding this, the semantic relationship with the preceding sentence is maintained:

| 21. ¡Qué injuria más atroz que esta sospecha! Ni, ¡qué agravio más público que el discurso |

| de cuatro amigos en una celda del convento! |

| What outrage more heinous than this suspicion! Nay, what insult more public than the |

| talk of four friends in a convent cell! (CDH. 1758. Isla, José. Fray Gerundio Campazas) |

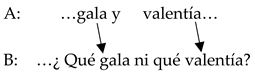

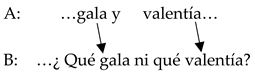

While all previous examples are clearly monologic, example (22) below is dialogic. Note that this change of scope encompasses that the former ¿Qué…? ¿Ni qué…? construction has turned into a new ¿Qué…ni qué…! construction:

| 22. —Lo dicho, dicho, padre maestro -respondió el predicador-: le alabo y le alabaré; porque si todos los sermones se hubieran de examinar con esa prolijidad, y si en ellos se hubiera de reparar en esas menudencias, allá iba a rodar toda la gala y toda la valentía del púlpito. |

| -¡Qué gala ni qué valentía de mis pecados! -exclamó el maestro Prudencio-. ¿Es gala el decir tantos disparates como palabras? |

| “What’s said is said, Father Master,” replied the preacher. “I praise you and will continue to do so; for if every sermon had to be examined with such meticulousness, and if one had to take note of such trifles, all the splendor and boldness of the pulpit would be lost.” |

| “Splendor and boldness, my sins be damned!” exclaimed Master Prudencio. “Is it splendor to utter as many absurdities as words?” (CDH. 1758. Isla, José. Fray Gerundio Campazas) |

Formally, the ¿Qué…? ¿Ni qué …? construction transforms into a ¡Qué X ni qué Y!Cxn The former two sentences amalgamate into one, exhibiting a common exclamative modality and a single prosodic contour. Semantically, the new construction shows an emphatic contrast between a first sentence (toda la gala y toda la valentía) and the negative evaluation of that first sentence (¡qué gala ni qué valentía!) by a second speaker. The clausal negative concord in the earliest examples has turned now into a refutative, dialogical meaning.8

Additionally, the open slots in the ni que.Cxn are filled in with words from the previous turn (uttered by Speaker A), explicitly negated in the construction (uttered by Speaker B):

One hundred years later, in monological examples, post-constructional changes arise, such as shifts in modality: exclamative-declarative (23), and declarative-exclamative (24). Although punctuation might not accurately reflect the actual prosody of these constructions, the exclusion of interrogatives and the varied solutions adopted by different writers suggest changes in the prosodic structure of this construction, occurring in dialogical and monological yet polyphonic constructions ():

| 23. —Yo asistí a la batalla de Bailén, y allí por casualidad singular, vinieron a mis |

| manos unas cartas… |

| Amaranta ni se inmutó. |

| — Señora, si he sabido casualmente alguna cosa que no debía saber, yo juro a usía |

| que el secreto no ha salido de mis labios ni saldrá mientras viva. |

| La condesa pareció poseída de nerviosa exaltación. |

| — ¡Estás loco! —exclamó. |

| — ¡Qué majaderías me cuentas! Ni qué tengo yo que ver con esas cartas ni con ese |

| hombre… |

| — I was present at the Battle of Bailén, and there, by a most singular chance, some |

| letters came into my hands… |

| Amaranta did not flinch. |

| — Madam, if by chance I have learned something I should not have, I swear to you |

| that the secret has not passed my lips, nor shall it while I live. |

| The Countess seemed possessed by a nervous agitation. |

| — You are mad!—she exclaimed. What nonsense you tell me! What do I have to do with those letters or that man… (CDH. 1874. Galdós. Napoleón en Chamartín) |

| 24. Si Gracia manifestó esperanzas, Demetria no, afirmándose en la seguridad de que Dios les mandaba apurar hasta el fin las amargas heces del cáliz. Fernando no les decía nada. ¡Ni qué había de decirles! Aseguró Gainza, cuando ya estaban cerca, que los habitantes de las ruinas abandonaban sus madrigueras antes del día para ir al trabajo. |

| If Gracia entertained hopes, Demetria did not, relying on the certainty that God had commanded them to endure to the end the bitter dregs of the cup. Fernando said nothing to them. What could he say to them? Gainza assured them, when they were already near, that the inhabitants of the ruins left their burrows before daybreak to go to their labor. (CDH. 1876. Galdós. De Oñate a la Granja.) |

Note that, in (24) the narrator’s voice (Fernado no les decía nada), contrasts with a character’s evaluation on that statement (¡Ni qué había de decirles!) in a clear polyphonic schema.

In the 20th century, ni qué becomes specialized as a dialogical construction, where speaker B strongly disagrees with speaker A’s preceding words, as in example (25):

| 25.—De paso. Salgo esta tarde en el Mazagán para Marruecos. Le voy a curar unas cataratas al Majzen, y llevo seis vagones de bellotas para hacer café. |

| — ¡Demonio! |

| — Lo que oyes. |

| — Pero, tú ¿eres médico?… ¿Desde cuándo?… ¿Ni qué bellotas?… |

| — ¡Negocios, hijo! Café para Marruecos: he montado en Fez un tostadero. Curo también la vista, con nitro y excremento de elefante. Vente a almorzar. ¡Tenemos que hablar mucho!… Me encontrarás rehabilitado, potentado, poderoso… |

| — By the way, I depart this afternoon on the Mazagán for Morocco. I am going to cure some cataracts for the Majzen, and I’m bringing six wagons of acorns to make coffee. |

| — Devil! |

| — What you hear. |

| — But tell me, are you a doctor?… Since when?… And what acorns? |

| — Business, my boy! Coffee for Morocco: I’ve set up a roastery in Fez. I also cure sight, with nitro and elephant dung. Come to lunch. We have much to discuss!… You’ll find me rehabilitated, prosperous, powerful… (CDH.1908. Felipe Trigo. A prueba) |

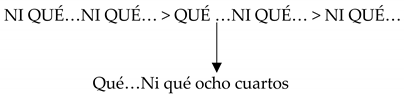

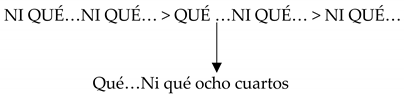

In conclusion, the complex NI QUÉ…NI QUÉ.Cxn evolves over time into a simpler ¡(QUÉ)…NI QUÉ!Cxn. This evolution exhibits the form-and-meaning features of a standard constructionalization: routinization and constituent loss, association with specific prosodic schemata (exclamative and interrogative), and specialization in dialogic environments and in pragmatic meanings (refutative, intensification). This complex, broad-spectrum construction licenses other derived constructions such as those studied in (Section 4.2 and Section 4.3): ni qué ocho cuartos and ni qué niño muerto. The development of this low-level constructions may be responsible for the activation of the “cousin” (See Section 5.2) construction ¡ni hablar del peluquín! (Section 4.4), driven by the vitality of sister (and cousin) constructions.

4.2. Qué…ni qué ocho cuartos

The Qué…ni qué ocho cuartos.Cxn (henceforth, 8/4.Cxn) is first attested in the corpus in 1761:

| 26. Todos: ¿Ayala amigo? |

| Ayala: ¿Qué amigo, qué Ayala, ni qué ocho cuartos? Ya es otro tiempo, señores. (Aparte.) ¡Que hasta aquí me han atisbado! |

| All: Ayala, my friend! |

| Ayala: What friend, what Ayala, what nonsense! Times have changed, gentlemen. (Aside.) They’ve been spying on me all this time! (CDH. 1761. Ramón de la Cruz. La avaricia castigada. Entremés nuevo). |

Example (26) is from a theater play where Ayala reacts to a previous interventio, in which the chorus addresses him with the vocative “Ayala, my friend”. The rejection takes the form of a refutative three-part construction, where the terms “friend”, “Ayala” and 8/4 are negated, highlighting the total inadequacy of the chorus’s remark to the situation. In this series, 8/4 functions as a generalized extender.

(26) is contemporaneous in time with example (22) above. In fact, the 8/4.Cxn is a subtype of the QUÉ…NI QUE.Cxn; the only difference lies in the fact that all constituents in the second part are fixed and can be interpreted as an idiom:

| A: | …x… | |

| B: | ¿Qué x ni qué ocho cuartos? | |

A plausible hypothesis for this development is that, once a semi-schematic construction, with a degree of generalization n is created, then n − 1, lower-level constructions are licensed (See Section 5.2). In this case, the relationship would be as follows:

The 8/4.Cxn in example (26) can be described as the conjunction of six conversational features recurrently found in the corpus: oral, dialogical, colloquial, echoic, refutative, and context-bound.9

As an oral construction, it is used in text types mimicking orality, such as theater plays and novels. It is found in the voice of the characters, not in narrator’s descriptions, making it typically dialogical or polyphonic.

Oral does not necessarily mean colloquial. Orality refers to the mode, while colloquial refers to the register (). Oral excerpts can be highly formal (e.g., a parliamentary session) and written texts can be highly informal (e.g., a Whatsapp chat). However, the prototype of oral texts is spontaneous conversation ().

The 8/4.Cxn is tightly context-bound, specifically to the previous turn: Speaker A says something (in most cases, a NP) rejected (refuted) by Speaker B in the next turn10:

- –

- …x…

- –

- ¿Qué x ni qué niño muerto?

This construction is echoic (interpretive) by nature. Since the open slot in the 8/4.Cxn is filled in by a constituent from the previous intervention, a narrow dependency between speaker A’s and speaker B’s interventions is established. Hence, the discourse unit over which the 8/4.Cxn operates is not Speaker B’s intervention, but a two-part, broader-scope unit called exchange (; ).

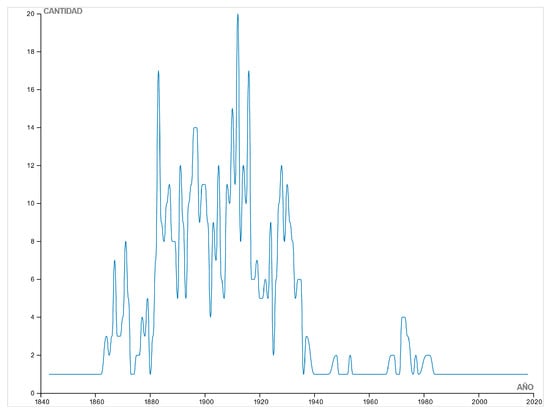

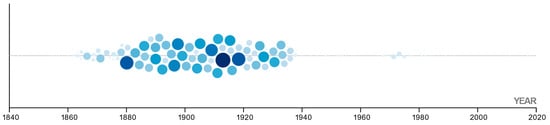

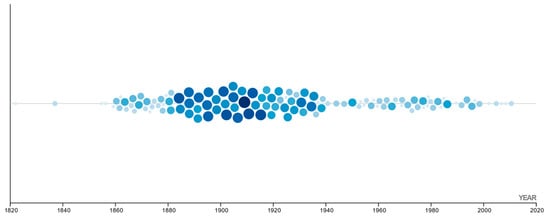

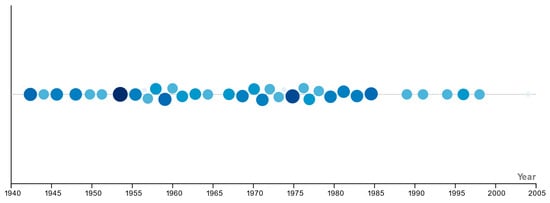

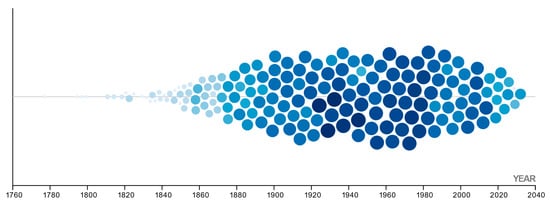

Although first documented in the 18th century, the 8/4.Cxn was most prolific in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2 (data extracted from BVPH). Note that Figure 1 plots the absolute frequencies between 1840 and 2020 whereas Figure 2 normalizes frequencies using a beeswarm plot. In this plot, the data cluster around the period 1880–1920, as indicated by the size and color of the dots (the darker the color, the more frequent the data):

Figure 1.

8/4 (absolute frequency).

Figure 2.

8/4 beeswarm plot (log scaling).

After the peak in 1900–1930 there is a sudden decay in the corpus, as evident in both absolute and normalized frequency graphs.

4.3. Qué…ni qué niño muerto…

The Qué…ni qué niño muerto.Cxn (henceforth, NM.Cxn) derives from an earlier construction, “qué niño envuelto” (lit. what-wrapped-child), as explicitly indicated in the Diccionario General etimológico, where both constructions are considered alternates:

¿Qué niño envuelto ó muerto? Expresión familiar con que alguno desprecia ó rechaza lo que se le propone ó se le pide ()

Niño envuelto is documented earlier in the Diccionario de Autoridades ():

Qué niño envuelto. Expresión familiar con que alguno desprecia ó rechaza lo que se le propone ó se le pide. Lat. Res inutilis vel inopportuna ().

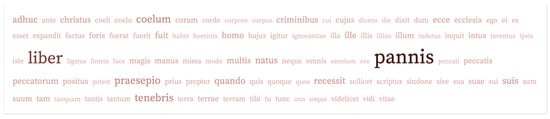

This expression, in turn, derives ultimately from the Latin phrase puer involutus (in pannis), which describes the baby Jesus in the manger. Puer involutus was a common shortcut to refer to the Holy Child, as evidenced in Figure 3 by a word-cloud analysis in the Patrologia Latina database (), where involutus strongly associates with pannis, but also with praesepio:

Figure 3.

Word cloud for involutus in the Patrologia Latina database.

The preconstructional change niño envuelto > niño muerto could be attributed to the formal similarity between the words muerto and envuelto, as well as to the visual analogy between an infant wrapped in swadding clothes and a shrouded corpse.

The modern form is first attested in 1822, sharing all the features described for the 8/4.Cxn: oral, dialogical, echoic, colloquial, refutative, and context-bound:

| 27. ¿Ves qué rosa tan bonita? acércatela á la nariz; qué huele ?—Qué oler, ni que niño muerto! Si es hortiga |

| Do you see how pretty this plant is? Bring it close to your nose; what does it smell like?”—“Smell? Nonsense, as if it were something rotten! It’s just nettle! (La tercerola. 1822. BVPH) |

Example (27) appears in a satirical publication where a character makes an interrogative statement, whose relevance is rejected by a second character by using the NM.Cxn

In the subsequent years, it is used in exactly the same contexts as in example (27). Most of the samples come from two sources: novels (reproducing dialogs as in example 28) and the press (especially in satirical publications or in sections where humor prevails, such as varia, anecdotes, etc.), again reproducing dialogs between fictional characters:

| 28. — Quita, quita. Pobres pero honrados. Yo no puedo aceder a sus deseos -dijo Charito acentuando esta frase que era de las que más presentes tenía, por haberla leído repetidas veces en una novela. |

| — Qué deseos ni qué niño muerto. Si no se trata de eso. Deja tú que yo me arregle con él para eso de la elección. Como es ministerial, figúrate. |

| No, no. Poor but honest. I cannot comply with their wishes—said Charito, emphasizing this phrase, which was one she often recalled, having read it repeatedly in a novel. |

| — What wishes, and what nonsense! It’s not about that. Leave it to me to handle the matter with him regarding the election. Since it’s ministerial, just imagine. (CDH. 1872. Pérez Galdós, Benito. Rosalía.) |

Around 1880, the immediate context needed for the NM.Cxn becomes more flexible. In some examples, long-distance dependencies are needed to identify the antecedent:

| 29. Declaro que Un paisano de Ramón falta a la verdad a sabiendas cuando me acusa de haber llamado sublime a la Pretel y genial a Loreto Prado. |

| De la Pretel dije: […] |

| Y de la Loreto hablé así: […] |

| Y en otra parte añadí, refiriéndome también a Loreto: […] |

| ¡Qué sublime, ni qué genial, ni qué niño muerto!”. |

| I declare that Un paisano de Ramón is knowingly lying when he accuses me of having called Pretel sublime and Loreto Prado a genius. |

| Of Pretel, I said: […] |

| And of Loreto, I spoke like this: […] |

| And elsewhere I added, also referring to Loreto: […] |

| “What sublime, what genius, or what nonsense!” (BVPH. 1900. La Correspondencia de España, 8 October 1900) |

Also, vague contextual references license the refutative meaning of NM.Cxn:

| 30. Cuando entró el Provisor, disminuyó el ruido; los más se volvieron a él, pero el jefe se contentó con poner una mano delante de la cara como rechazando a todos los importunos y se fue a una mesa a preguntar por un expediente de mansos. “Lo que él decía; en las oficinas de Hacienda pública no daban razón; los expedientes de mansos dormían el sueño eterno, cubiertos de polvo.” |

| El señor Carraspique daba pataditas en el suelo. |

| — ¡Estos liberales! -murmuraba cerca del Magistral-. ¡Qué Restauración ni qué niño muerto! son los mismos perros con distintos collares… |

| When the Provisor entered, the noise diminished; most turned towards him, but the chief was content merely to place a hand before his face, as though rejecting all the importunate, and went to a table to inquire about a file of the mansos. “What he said was true; in the offices of the Treasury, no one could provide an answer; the files of the mansos lay in eternal slumber, covered in dust.” |

| Mr. Carraspique was tapping his feet on the floor. |

| — These liberals!—he murmured near the Magistral.—What Restoration, what nonsense! They’re the same dogs with different collars…(CDH. 1884. Leopoldo Alas, “Clarín”. La Regenta). |

In (30), Carraspique’s negative assessment of the current government (These liberals!) opens a framework enabling a refutation of this hypernym—the political system itself (that is, the Restoration).

Examples (29) and (30) show that the tight contextual dependency in early examples of this construction is relaxed, though reference to a first part must still be kept or at least evoked.

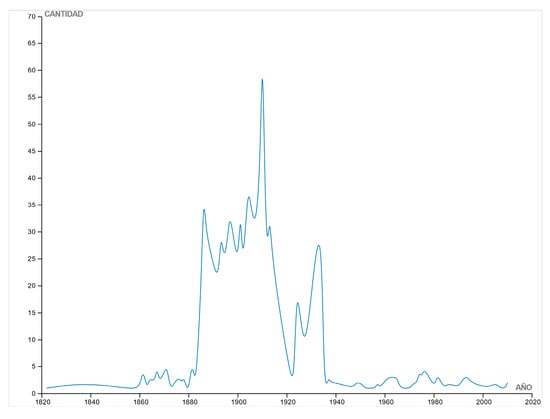

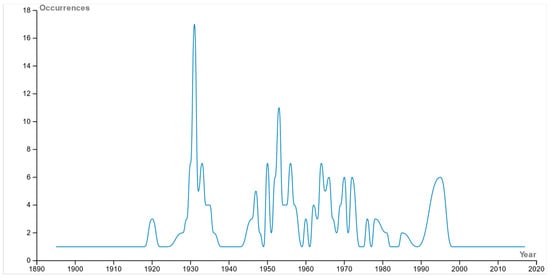

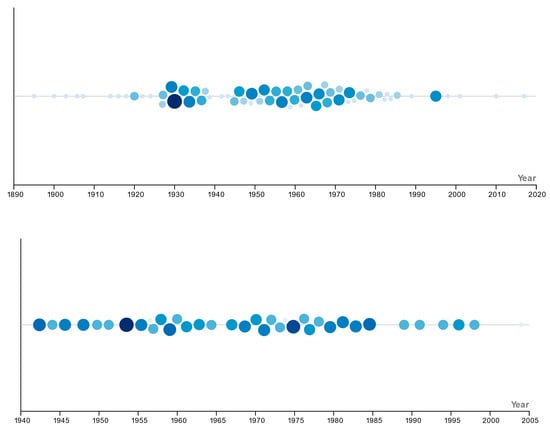

The NM.Cxn was a low frequency construction until 1880–1910, when most of its occurrences are concentrated in the corpus. Figure 4 and Figure 5 show the absolute and the normalized frequencies of the NM.Cxn, interpreted similarly to Figure 1 and Figure 2 above:

Figure 4.

NM.Cxn (absolute frequency).

Figure 5.

NM.Cxn (log scaling).

The peak productivity of the NM:Cxn coincides in time with that of the 8/4.Cxn, suggesting some kind of mutual influence between both sister constructions. Its vitality, though, appears stronger in subsequent decades. As the NM.Cxn is more humorous than the 8/4.Cxn, the temporal precedence of the former over the latter makes sense, since a “shift from humorous to more humorous mode” seems plausible once an initial construction has paved the way.

4.4. Ni hablar del peluquín

Ni hablar del peluquín (henceforth, NHDP.Cxn), (lit., do not even speak about the periwig), not being a sister construction of the (NI) QUÉ…NI.Cxn family, is deeply entrenched with it. Table 3 presents a tentative genealogic tree of the three constructions examined in this study11: higher-level constructions (Level 1) develop into middle-level constructions (Levels 2 and 3) leading to lexicalized constructions (Level 4).

Table 3.

The road to NHDP.Cxn (and neighbour constructions).

While the 8/4.Cxn and the NM.Cxn ultimately derive from a higher-level QUÉ.Cxn, NHDP.Cxn derives from a higher-level NI.Cxn However, between these two levels, intermediate constructions are found. Ni.Cxn develops into Ni (+que/+inf).Cxns. The first combines with the Qué+O.Cxn to give rise to the 8/4 and NM constructions. The second develops into the fully fledged Ni hablar del peluquín.Cxn through the intermediate low-level construction Ni hablar de es(t)o.Cxn The third serves as the basis for ¡Ni es que ni es ca! (not described in this paper). NM, 8/4 and NHDP are, in a sense, cousins (See Section 5 for a discussion on the types of relationships linking the constructions considered here).

Historically, NHDP.Cxn became possible due to the preexisting Ni hablar de es(t)o.Cxn This root construction shares with the 8/4 and the NM.Cxns their insubordinate, dialogic, context-bound character, but in different key ways: Ni hablar de esto.Cxn is related to the semantic field of saying, a productive source in Spanish, for idioms (ni qué decir tiene, es un decir, dicho esto, etc.) or for discourse markers (es decir). As the act of saying is negated, a refutative meaning arises, but this meaning is not polyphonic and closer to a literal interpretation (that is, more descriptive than interpretive—).

Ni hablar de esto.Cxn is first documented in 1895:

| 31. LAS ELECCIONES |

| — Ni hablar de eso por ahora. |

| El Gobierno tiene otras preocupaciones más perentorias |

| THE ELECTIONS |

| — Don’t even bring that up for now. |

| The Government has more urgent matters to attend to. (BVPH. 1895. La Opinión: periódico político y de intereses generales) |

Example (31) is from an interview where the answers are grouped by theme. Ni hablar de eso functions as a refutative, elaborated response to a previous question.

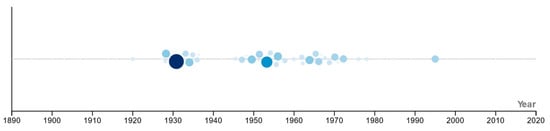

Ni hablar de eso is documented 203 times in the BVPH, peaking around 1930, with most occurrences between 1950 and 1980, as shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7:

Figure 6.

Ni hablar de eso (absolute frequency).

Figure 7.

Ni hablar de eso (log scaling).

It seems plausible to conclude that NHDP evolved from this preexisting construction, as did the shorter ni hablar. Ni hablar de esto.Cxn likely served as the template for expansion and reduction, yielding these younger related constructions.

NHDP is associated with the title of popular song (tanguillo) in a music show in 1942 (https://cvc.cervantes.es/foros/leer_asunto1.asp?vCodigo=37152 and 1de3.com [accessed on 26 February 2025]). It is unclear whether NHDP.Cxn was an individual creation or if reflects rather a longer-lasting idiom. Otherwise said: the dilemma of whether this construction is an individual creation or a popular saying picked up by the author admits two reasonable explanations. While individual creations are rare and difficult to trace, they are not uncommon in language history (see for the rise of It. Ma vieni!). It is challenging to reach a definitive conclusion; however, the second example retrieved in the BVPH is dated 1943 and explicitly mentions this music show:

| 32. El espectáculo resulta, sin embargo, entretenido y el público lo recibió muy bien y aplaudió mucho, especialmente “Tabaco y seda”, “Callejuela sin salida”, “La señorita del acueducto, “Solera vieja”, “Ni hablar del peluquín” y “Que se acaba el mundo”. |

| The show, nevertheless, proves quite entertaining and was very well received by the audience, who applauded heartily—especially for ‘Tobacco and Silk,’ ‘Dead-End Alley,’ ‘The Lady of the Aqueduct,’ ‘Old Vintage,’ ‘Don’t Mention the Periwig,’ and ‘The End of the World (BVPH, 1943. Pueblo, 23 de noviembre [accessed on 27 February 2025]). |

The NHDP.Cxn, associated with orality, is poorly reflected in the corpus (see Figure 8 and Figure 9), with marginal recurrence throughout the 20th century:

Figure 8.

NHDP.Cxn (absolute frequency).

Figure 9.

NHDP.Cxn (log scaling).

As the time span considered concerns the author’s linguistic competence, the corpus quantification may not fully capture the speakers’ mental availability of NHDP.Cxn in their mind. This could be due to its informal character, associated with oral discourse, and the historical exclusion of informal constructions from formal written texts. When Spanish underwent colloquialization in the early 1970s (; , , ; ) and barriers to reflect orality relaxed, the NHDP.Cxn was probably perceived as out-of-date and syrupy, a relic of a bygone society (post-war and Franco’s times). Hence, the frequency of NHDP.Cxn in the corpus could have been affected by a double constraint: when it was an active construction, it was banned by the rhetorical norms at the time; in turn, when the normative veto was released, the speaker’s sensitivity had shifted to other domains.

Turning back to the origins of this construction, let us examine the contexts where peluquín (‘periwig’) is used. Peluquín is first documented in 1725 and is defined in the Diccionario de Autoridades as “short wig”. Though this definition is quite neutral, analysis of the contexts where peluquín is found between 1700 and 1770 reveals its use in comedies, characterizing ridiculous characters, and also in satirical press descriptions. Associated with the new French dynasty ruling Spain since 1713, the periwig was seen as a foreign and unnecessary complement, worn by nobles or gentry, scoffed at by the lower classes. Popular characters complain about this adornment being a compulsory element in uniforms:

| 33. ¡Hola! ¡Pardiez que me está major la cofia encarnada que el peluquín, y no pesa un adarme! ¡Fiera carga es para un mísero paje peluquín por la mañana, peluquín al medio día, la tarde y la noche larga peluquín y peluquín tal vez á media noche cuando se levanta porque le ha dado un soponcio el ama! ¡San Isidro de mi vida! |

| Hail! By gad, the red coif suits me better than the periwig, and it weighs not a dram! A fierce burden it is for a wretched page—periwig in the morning, periwig at midday, periwig in the evening and the long night, and mayhap periwig even at midnight when he rises, for his mistress has taken a fainting fit! Saint Isidore, my life! (1766. La pradera de San Isidro. Ramón de la Cruz, CDH) |

This humorous context of use is inherited by the NHDP.Cxn. In the 20th century, periwigs did not exist anymore but wigs did. Especially for men, wigs were seen as ridiculous (), owing to their primitive manufacture and sense of artificiality. In fact, in classical comedies—like Billy Wilder’s The party—a gag arises when an accidental action involves wig removal. In this sense, (1de3.com) points out that NHDP could have probably been associated to a politeness rule forbidding mention of someone’s covered baldness—even, or especially, if obvious. True or not, we may conclude that

- (a)

- Peluquín is associated with ironic contexts and speakers in humorous mode ();

- (b)

- in the 20th century, baldness was a source for mockery, as were attempts to hide it;

- (c)

- NHDP.Cxn can only be understood in a humorous, but not in a literal, sense (i.e., it never refers to the actual need to avoid mentioning a real periwig).

5. Discussion

5.1. About Entrenchment

Joining together the data scattered in Section 4, a partial evolution of this deeply entrenched set of constructions can be outlined. When the data from Table 3 are schematized, a diachronic development can be appreciated. A global representation of this set of constructions is provided in Figure 10:

Figure 10.

Constructional network including the 8/4, NM and NHDP constructions.

The starting point consists of higher-level constructions QUE.Cxn, NI.Cxn, along with NEG.Cxn, EXCL.Cxn and INT.Cxn12. They belong to the Spanish linguistic system since its earliest stages and, in this sense, can be considered constructional primitives.

The combination of form and meaning features of these primitive constructions gives rise to medium-high level constructions (¡QUÉ X!.Cxn, NI QUÉ X.Cxn). Here, the clausal or phrasal scope of the constituents increases the range of variation and the frequency of the constructions within the system. This goes together with the specialization in interrogative or exclamative modalities and the associated meanings (expressive or interpersonal).

When such medium-level constructions are mediated by restrictions imposed by the different discourse traditions of scripturality (), further more elaborated constructions emerge, such as the medium-low level Ni qué X ni qué Y.Cxn (ca. 1520), with posconstructional alternates No X. ¿Ni qué Y?, and INT ¿Ni qué Y? (ca. 1550).

During the 17th century, the link with NEG.Cxn is replaced by INT.Cxn. In the 18th century, the relationship with the EXCL.CXN is strengthened and, alongside its use in dialogical and polyphonic contexts, a refutative meaning arises.

As an expansion of this refutative meaning, in the context of spontaneous conversations, and reinforced by humor, the 8/4.Cxn and the NM.Cxn appear in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Activated by humor—an active, distinct mechanism in spoken Spanish if () is correct—NHDP.Cxn (1943) is coined as an expansion of the preexisting Ni hablar de eso.Cxn (1895). Note that, without humor, the natural step of this construction would be to shrink into a more neutral Ni hablar.Cxn (1931).

From the point of view of the formal constituents inside each construction, two movements are detected: first, expansion (the tendency to increase construction length, driven by underlying mechanisms such as humor,) and second, reduction (loss of words compared to previous stages as a result of merging formal, semantic and contextual features into one single construction).

Although at first sight it might seem that the lower the level in the construction, the longer its form, a more realistic view is that expansion and reduction can occur at any stage (see, for instance, the evolution ni hablar de eso > [NHDP/ni hablar], where expansion and reduction occur simultaneously).

5.2. A Vertical Depiction of the Constructicon (or How Many Floors?)

The (partial) constructional network described in Section 5.1 poses the question of the kind(s) of relationships linking the (at least) twelve medium-low and low level constructions related in the description of the NM.Cxn, 8/4.Cxn and NHDP.Cxn Their place in a constructicon, the levels needed for their description, and the relationships connecting them are nontrivial issues; indeed, the structure of the constructicon is a debated topic in Construction Grammar.

() distinguishes two different organizations: families and neighborhoods. Family is defined as “a group (or pair) of similar constructions that are categorized as subtypes of the same schema”. Alternatively, neighborhood “describes a group (or pair) of similar constructions that are licensed by different schemas”. In Diessel’s account, family seems to be a simpler concept than is needed here, whereas neighborhood seems a productive term for metaphoric or metonymic expansions. However, the constructions studied here seem to form a case of “extended family”. This seems coherent with the productivity of language and the entrenchment of vertical (inheritance) and horizontal relationships (constructional contamination, according to ).

The data in this study indicate that higher productivity at any node in a constructional network can potentially impact related nodes. Thus, a plausible hypothesis stemming from the data is that productivity can activate neighboring nodes in various directions:

Top-down productivity: This is the most obvious frequency activation (e.g., ). An active higher NI.Cxn enables a schematic structure (NI QUE…NI QUE.Cxn). This, in turn serves as the basis for deriving new lower-level, semi-schematic constructions (NI +O.Cxn, NI+INF.Cxn, NI X NI Y.Cxn). These constructions inherit features from the original construction up to the point where they become filled idioms ().

Bottom-up productivity: increased frequency in a low-level construction enhances the possibilities of higher nodes (e.g., the productivity in the NM.Cxn strengthens the constructional possibilities of NI.Cxns). At this lower-level, a taxonomical relationship () can emerge where a more abstract schema is inferred through schematization (). For instance, the humorous nature of 8/4.Cxn becomes attached to NI.Cxns, what explains the humorous nature of NM.Cxn and NHDP.Cxns. To what extent this bottom-up spread is possible, remains an open question for future research.

Sister-to-sister productivity: an active construction (8/4.Cxn) enhances productivity in sister constructions (NM.Cxn), especially when mechanisms like humor are involved. Humor boosts spread via conversational success, and is likely to contaminate nearby constructions, particularly in societies and social groups where humor is a highly valued social feature.

Sister-to-cousin productivity: We propose the term cousin relationship for a horizontal relationship between two or more constructions that do not share (are not governed by,) the nearest upper node. This is the case of NHDP.Cxn, whose rise may have been fostered by the spread of the cousins 8/4.Cxn and NM.Cxn. Their conversational nature, refutative character and humor-driven origin are to some extent integrated into the higher-level, semi-schematic NI QUÉ. and NI.Cxns. A key factor here is simultaneity, as the peak period for all three constructions coincides (1900–1940), likely activating these features in speakers’ minds.

Constructional network productivity: the entire system of insubordinate constructions is enhanced as a result of the different developments in lower levels, this leading to the prevalence of a constructional network (in this case, insubordinate constructions) in the historical development of a language (the type of the language, according to Coseriu, 1978).

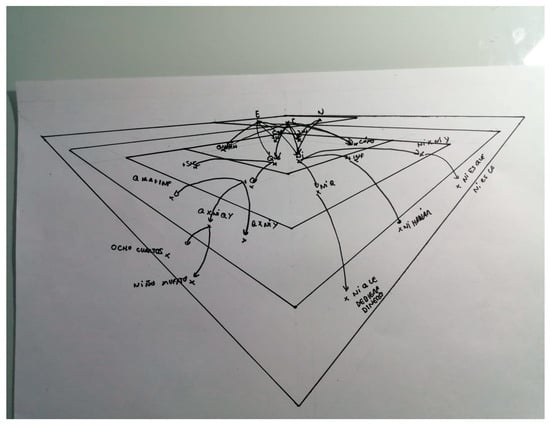

Figure 11 tentatively illustrates a five-level picture of the insubordinate construction family in Contemporary Spanish:

Figure 11.

The Contemporary Spanish insubordination family (and beyond).

6. Conclusions

6.1. The Role of Humor in Constructionalization Processes

From the case studies presented in this paper, it stems that humor plays an active role in the creation of new constructions. The relationship between humor and CxG has been explicitly addressed by (). However, their approach studies the contribution of CxG to humor by analyzing how semi-schematic constructions foreground certain patterns and give rise to incongruities that license humor by coercion. In this paper, however, the focus is on the role humor plays in boosting the vitality of constructions within a constructional network. And this from two different, complementary perspectives: top-down and bottom-up. The first explains the place of humorous constructions in a constructicon; the second, the role of humor in the dissemination—in the conversational success—of newly coined constructions.

For humor to emerge, a precondition seems necessary: a preexisting schema must exist upon which a humorous construction can be built. Figure 10 above shows that humorous constructions are at the bottom of the constructional network, indicating their dependence on semi-schematic, medium-low constructions. This vertical dependence is supported by diachronic data.

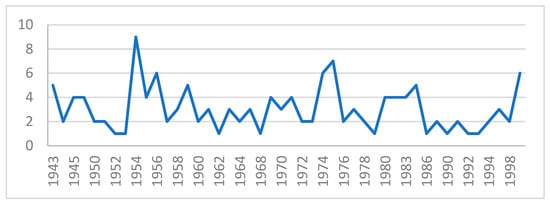

For instance, the NM.Cxn and the 8/4.Cxn (See Section 4.1, Section 4.2 and Section 4.3), rely on the more general NI QUÉ…Cxn The case of NHDP.Cxn (1943) is even clearer, as it was created from the older ni hablar de eso.Cxn (1895), and contemporaneous with the shorter ni hablar.Cxn (1931), as shown in Figure 12. The accumulation of cases is indicative of how active the parent construction was at the time daughter constructions arose:

Figure 12.

Ni hablar de eso vs. NHDP vs. Ni hablar.Cxns (log scaling).

The force of humor—an active, distinct mechanism in spoken Spanish if () is right—enabled the coining of NHDP.Cxn (1943) as an expansion of a preexisting ni hablar de eso.Cxn (1895). Thus, in line with the discussion on coertion (; ), humor seems to operate through elaboration, expanding preexisting constructions into more complex, more baroque constructions, and opening new slots through nuanced word choices within the constructional schema. Two forces seem at play, each contributing to shape the constructicon in different ways: a systemic coertion, driven by structural constraints, and a pragmatic escape, shaped by norms, discourse traditions and conventions of use.

This kind of coertion/expansion can be exemplified by a highly productive schema in spoken Spanish: the comparative [SER/ESTAR/TENER] MÁS X QUE Y.Cxn (lit. ‘to be/have more X than Y’). The open places in this construction allow for various types of relationship: estar más perdido que un pulpo en un garaje, ser más peligroso que un tiroteo en un ascensor (lit. “loster than an octopus in a garage”, “more dangerous than a shooting in a lift”), and so on (). Consider the following constructions:

| 34. Ser más feo que Picio (lit. “Uglier as the devil”) |

| 35. Ser más feo que pegarle a un padre (lit. “Uglier than hitting a father”; “so ugly it should be illegal”) |

In (34), feo means “physically unpleasant”. But feo can also mean “morally unpleasant” (e.g., showing disrespect to elders can be considered feo). This allows for the expansion in (35), where the incongruity between the interpretation of feo in the first part of the comparative construction (with the physical interpretation foregrounded on the moral interpretation, backgrounded) is resolved in the second part of the structure with the moral interpretation overriding the physical one. This clash of schemes generates humor.

Once the humorous construction (35) is active, further elaboration can create second-degree, low-level constructions, such as ser más feo que pegarle a un padre [con un calcetín sudado] (lit. “uglier than hitting a father with a sweated sock”). Here humor does not arise from a clash of frames, but from the metonymic search of a deviant follow-up consistent with (34). This second-degree humorous interpretation is challenging because speakers already recognize (34) as humorous, and building humor upon humor requires a high degree of elaboration.

From the bottom-up perspective, the key question here is: What makes humor a winning strategy in conversation? CA and politeness studies (; ; ), aligning with (), highlighted the collaborative nature of spontaneous conversations and the pursuit of agreement between speaker and hearer as key interactional goals. In this framework, Humor is a powerful ally: laughter is a positive feeling strengthening bonds between speakers and audiences. As a highly valued conversational prize, achieving humor is a reasonable cause for the iteration and diffusion of successful constructions to new contexts. Humor thrives where normative requirements on what and how to say are relaxed; namely, in spontaneous conversations, which are the by default locus of change ().

Social norms add a second layer of elaboration, as tolerance to change and deviation may foster or hinder humor. We tentatively hypothesize that Mediterranean, catholic societies value humor as a form of wit and stravaganza, whereas Protestant societies, priorizing literality, may impose limits on humoristic creations—a hypothesis worth testing but also in need of evidence…

6.2. Present-Day Spanish (and Beyond) as a Privileged Observatory for Diachronic Research

The imperfect reflection of real usage in Historical Linguistics is a common observation, encapsulated in Labov’s adage of making good use of bad data. However, diachronic research on the 20th century offers a less imperfect reflection ().

As the century goes on, Western societies achieved full literacy, this meaning that virtually the entire population could understand and produce texts. And not only is literacy achieved; in the last third of the century, the proportion of people with higher education degrees increased, enabling a growing portion of the citizens in developed countries to understand and produce complex texts (). This led to an exponential increase in text production, presenting researchers with the problem of data excess—not lack of.

Also, linguists can leverage their intuitions, as the language studied is (almost) their own. For example, the intuition (; ) that the corpus reflection of NHDP.Cxn does not match its activation in speakers’ constructicons can only be explored diachronically within this time span.

What the study of the 20th century offers to historical linguists is a detailed zoom into the processes that led to innovation, dissemination and decline of linguistic constructions; the social factors entrenched with innovations (); the role of individuals in linguistic change (); and the pace of innovation spread across decades, years or even months (; ).

Historical linguists can benefit from this crossroad between synchrony and diachrony by examining data with a degree of granularity impossible to achieve for earlier periods. Synchronic linguists, in turn find it this field the most immediate historical explanations for why present-day languages are as they are.

Funding

This paper was made possible thanks to the following research projects: Project CIPROM/2021/038 Hacia la caracterización diacrónica del siglo XX (DIA20), Generalitat Valenciana, and I+D+I Project PID2021-125222NB-I00 Aportaciones para una caracterizacion diacronica del siglo XX, sponsored by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/, and FEDER Una manera de hacer Europa.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author wants to thank the comments made by Ricardo Maldonado, Álvaro Octavio de Toledo, Leonor Ruiz Gurillo and three anonymous reviewers, whose remarks have improved substantially the final version of this paper. All short backs belong to the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | As this paper adopts CxG as the by default paradigm, references to grammar may appear inaccurate. By ‘grammar’, I mean ‘structure’ in a post-Saussurean sense, or ‘grammar’ as opposed to ‘lexicon’, in a formalist sense. |

| 2 | Thank you to one of the anonymous reviewers for highlighting the need to address this issue. |

| 3 | See Traugott and Trousdale 2013 for a comprehensive account on the different approaches to Construction Grammar. |

| 4 | The constructions discused in this paper are very different from each other. For example, (13) and (14) are grouped together due to their shared humorous nature. However, this does not mean that they behave similarly (13 is metadiscursive and 14 is consecutive)–Ricardo Maldonado, personal communication –. |

| 5 | Leonor Ruiz (personal communication) suggests that the irony may stem from the refutative nature of A’s intervention, given that stating the opposite of a certain state of affairs is the traditional source for irony. |

| 6 | () consider this a case of high contextual dependency. (), on the other hand, differentiate between discourse markers in reactive interventions and discourse markers in initiative interventions. The former are context-bound and, therefore, linked to the previous intervention, whereas the latter are not. |

| 7 | Álvaro Octavio de Toledo (personal communication) suggest that the construction ¿Qué X o qué Y? could be ther source of the Ni qué…ni qué.Cxn This contamination would have occurred due to their common use in rhetorical questions. The implications of this remark are relevant for a wider constructional account, but they go beyond the scope of this paper. |

| 8 | Ricardo Maldonado (personal communication) suggests that the starting point for this construction may lay in the anaphoric character of ni qué, with reduplication being a secondary effect driven by expressivity. This explanation would also apply to example (24) below. |

| 9 | () describes the same features in her synchronic description of the 8/4.Cxn This coincidence suggests that all values were abruptly acquired and have remained unchanged since that moment. |

| 10 | For a similar analysis of refutative expressions in audiovisual recordings, see (). |

| 11 | This is a simplified version of the full picture, in which the higher level NEG.Cxn, EXCL.Cxn and INSUBORDINATE.Cxns also need to be considered. |

| 12 | The explanation provided here has been simplified for clarity. A full account of the entire set must also consider insubordinate constructions such as CON.Cxn (¡Con lo buena que ha sido!) or SI.Cxn (–No bebas—¡Si tengo sed!). |

References

- Amara, L. (2015). Historia descabellada de la peluca. Anagrama. [Google Scholar]

- Antonopoulou, E., & Nikiforidou, K. (2009). Deconstructing verbal humor with construction grammar. In G. Brône, & J. Vandaele (Eds.), Cognitive poetics: Goals, gains and gaps (pp. 289–314). Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Attardo, S., & Raskin, V. (1991). Script theory revis(it)ed: Joke similarity and joke representation model. HUMOR: International Journal of Humor Research, 4(3–4), 293–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcia, R. (1887). Primer diccionario general etimológico de la lengua española. Seix editor. [Google Scholar]

- Beijering, K., Kaltenböck, G., & Sansiñena, M. S. (Eds.). (2019). Insubordination: Theoretical and empirical issues [Trends in linguistics. Studies and monographs 326]. De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Beinhauer, W. (1929). El español coloquial. Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- Beinhauer, W. (1973). El humorismo en el español hablado. Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, A. (1847). Gramática de la lengua castellana destinada al uso de los americanos. Imprenta del Progreso. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield, L. (1933). Language. Allen and Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Brinton, L. J., & Traugott, E. C. (2008). Lexicalization and language change. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Briz, A., & Grupo Val.Es.Co. (2002). Corpus de conversaciones coloquiales. Anejo II de la revista Oralia, 1, 1–383. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1989). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chovanec, J., & Tsakona, V. (Eds.). (2018). The dynamics of interactional humor: Creating and negotiating humor in everyday encounters [Topics in Humor Research 7]. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Coseriu, E. (1978). Principios de semántica estructural. Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- Croft, W. (2001). Radical construction grammar: Syntactic theory in typological perspective. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Diessel, H. (2024). The Constructicon. Cambridge; CUP. [Google Scholar]

- Ducrot, O. (1984). Le dire et le dit. Les Éditions de Minuit. [Google Scholar]

- Dynel, M. (2021). Humor in interaction: Pragmatic and cognitive approaches. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Enghels, R., & Sansiseña, M. S. (2021). Insubordination in Romance: A cross-linguistic analysis. De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Estellés, M., & Pons Bordería, S. (2014). Absolute initial position. In S. Pons Bordería (Ed.), Discourse segmentation in romance languages (pp. 121–155). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, N. (2007). Insubordination and its uses. In I. Nikolaeva (Ed.), Finiteness: Theoretical and empirical foundations. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fedriani, C., & Molinelli, P. (2024). Cultural products, passing fashions and linguistic changes. A view from the Italian pragmatic marker ma vieni. In S. Pons Bordería, & S. Salameh (Eds.), Language change in the 20th century: Exploring micro-diachronic evolutions in Romance languages (pp. 95–119). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, A. E. (1995). Constructions: A construction grammar approach to argument structure. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, A. E. (2006). Constructions at work: The nature of generalization in language. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gras, P. (2011). Gramática de Construcciones en Interacción. Propuesta de un modelo y aplicación al análisis de estructuras independientes con marcas de subordinación en español [Ph.D. thesis, Universidad de Barcelona]. [Google Scholar]

- Gras, P. (2013). Entre la gramática y el discurso: Valores conectivos de que inicial átono en español. In D. Jacob, & K. Ploog (Eds.), Autour de que (pp. 89–112). Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Gras, P. (2016). Revisiting the functional typology of insubordination: Insubordinate que-constructions in Spanish. In N. Evans, & H. Watanabe (Eds.), Insubordination [Typological Studies in Language 115] (pp. 113–144). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Gras, P., & Sansiseña, M. S. (2017). Broad vs. narrow approaches to insubordination. In K. Beijering, G. Kaltenböck, & M. S. Sansiñena (Eds.), Insubordination: Theoretical and empirical issues (Vol. 41, pp. 573–598). [Google Scholar]

- Gras, P., & Sansiseña, M. S. (2020). Un caso de variación pragmático-discursiva: Que inicial en tres variedades dialectales del español. Romanistisches Jahrbuch, 71(1), 271–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grice, H. P. (1975). Logic and conversation. In P. Cole, & J. L. Morgan (Eds.), Syntax and semantics 3: Speech acts (pp. 41–58). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi, Y., & Ishida, T. (2019). A construction discourse approach to humorous incongruity: Script opposition revisited. Tsukuba English Studies, 38, 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Itkonen, E. (2008). Qué es el lenguaje. Biblioteca Nueva. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, P., & Oesterreicher, W. (1990). Gesprochene sprache in der romania: Französisch, Italienisch, Spanisch. Max Niemeyer Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Laineste, L. (2016). Laughing matters: The dynamics of humor in political contexts. University of Tartu Press. [Google Scholar]

- Langacker, R. W. (2008). Cognitive grammar: A basic introduction. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Linares, E. (2021). Pragmática de la ironía en español. Iberoamericana Vervuert. [Google Scholar]

- Llopis, A., & Pons Bordería, S. (2020). La gramaticalización de ‘macho’ y ‘tío/a’ como ciclo semántico-pragmático. CLAC, 82, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Serena, A. (2007). Oralidad y escrituralidad en la recreación literaria del español coloquial. Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- López Serena, A. (2014). Historia de la lengua e intuición: Presentación. RILCE, 30(3), 691–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Serena, A., & Leal, M. U. (2024). Marcadores del discurso y esquemas construccionales. Los patrones discursivos de bueno en La lucha por la vida de Pío Baroja. Anuari de Filologia, 14, 454–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manero, A., & Olza, I. (2023). Fraseología del desacuerdo en un corpus multimodal de televisión: Un estudio multinivel. CLAC, 95, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michigan, A. A. (2013). Patrologia Latina database. Available online: https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/efts/PLD/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Millán, J. A. (2002). “El mundo entero le saldrá al encuentro”: Las comparaciones en sus repertorios. In P. Á. de Miranda, & J. Polo (Eds.), Lengua y diccionarios, Estudios ofrecidos a manuel seco. Arco/Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Mura, G. A. (2019). La fraseología del desacuerdo: Los esquemas fraseológicos en español. Sevilla, Universidad. [Google Scholar]

- Östmann, J.-O. (2005). Construction Discourse: A prolegomenon. In J.-O. Östman, & M. Fried (Eds.), Construction grammars: Cognitive grounding and theoretical extensions (pp. 121–144). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Pijpops, D., & Van de Velde, F. (2016). Constructional contamination: How does it work and how do we measure it? Cognitive Linguistics, 27(4), 527–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons Bordería, S. (2014). El siglo XX como diacronía: Intuición y comprobación en el caso de “o sea”. RILCE, 30(3), 985–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons Bordería, S. (2022). Creación y análisis de corpus orales: Reflexiones teóricas y saberes prácticos. Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Pons Bordería, S. (2024). How are linguistic changes in the 20th century to be studied?: Sp. VOC- tío or merging sociolinguistic and philological explanations. In S. Pons Bordería, & S. Salameh Jiménez (Eds.), Language change in the 20th century (pp. 188–217). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Pons Bordería, S., Pardo Llibrer, A., & Alemany Martínez, A. (2024). La marcación discursiva en español: Descripción y análisis estadístico desde el DPDE. University of Sevilla. [Google Scholar]

- Priego Valverde, B. (2024). L’analyse de l’Humor par la linguistique des interactions: Vers une approche intégrative de l’humor conversationnel. HAL Open Science. [Google Scholar]

- Raskin, V. (1985). Semantic mechanisms of humor. Reidel. [Google Scholar]

- Real Academia Española. (1726–1739). Diccionario de autoridades. Available online: https://webfrl.rae.es/DA.html (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Real Academia Española. (2009). Nueva gramática de la lengua española. Espasa-Calpe. [Google Scholar]

- Real Academia Española. (2013). Diccionario histórico de la lengua española (DHLE) [en línea]. Consulta: 17/06/2024. Real Academia Española. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Rosique, S. (2009). Una propuesta neogriceana. In L. R. Gurillo, & X. P. García (Eds.), Dime cómo ironizas y te diré quién eres. Una aproximación pragmática a la ironía en español (pp. 109–132). Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Roulet, E., Auchlin, A., Moeschler, J., Rubattel, C., & Schelling, M. (1985). L’articulation du discours en français contemporain. Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Gurillo, L. (2012). La lingüística del humor en español. Arco/Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Gurillo, L. (2018). ¿Cómo se gestiona la ironía en la conversación? Rilce. Revista de Filología Hispánica, 25(2), 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Gurillo, L. (2022). Interactividad en modo humorístico: Géneros orales, escritos y tecnológicos. Vervuert. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Gurillo, L. (2024). Mock impoliteness in Spanish: Evidence from the VALESCO.HUMOR corpus. Humor, 37(1), 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Gurillo, L., & Alvarado, B. (Eds.). (2013). Irony and humor: From pragmatics to discourse. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks, H., Schegloff, E., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language, 50(4), 696–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salameh, S. (2024). Coloquialización, microdiacronías y consolidación de géneros orales en el siglo XX: El léxico como parámetro de cambio en la retransmisión futbolística. In A. Hernández, & C. León (Eds.), Partido a partido: La lengua del fútbol (pp. 89–117). Venezia, Ca’Foscari, Colección VenPalabras. [Google Scholar]

- Salameh, S. (2025). Colloquialization Processes in the 20th Century: The Role of Discourse Markers in the Evolution of Sports Announcer Talk in Peninsular Spanish. Languages, 10(7), 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salameh, S. (2026). Primeras huellas del humor oral en el siglo XX: Análisis de la colección de registros sonoros de la BNE. ELUA. [Google Scholar]

- Sansiñena, M. S. (2015). The multiple functional load of que. An interactional approach to insubordinate complement clauses in Spanish [Ph.D. thesis, KU Leuven]. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, C. (1999). Los cuantificadores: Clases de cuantificadores y estructuras cuantificativas. In Gramática descriptiva de la lengua española (pp. 1025–1198). Espasa-Calpe. [Google Scholar]

- Sinkeviciute, V. (2019). Conversational humor and (im)politeness: A pragmatic analysis of social interaction. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Sperber, D., & Wilson, D. (1981). Irony and the use-mention distinction. In P. Cole (Ed.), Radical pragmatics (pp. 295–318). New York Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sperber, D., & Wilson, D. (1986). Relevance. Communication and Cognition. Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, L. (1922). Italienische umgangssprache. Kurt Schroeder Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Timofeeva, L. (2017). Metapragmática del humor infantil. CLAC, 70, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traugott, E. C. (2002). From etymology to historical pragmatics. In D. Minkova, & R. Stockwell (Eds.), Studies in the history of the English language (pp. 19–49). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Traugott, E. C. (2012). Pragmatics and language change. In K. Allan, & K. Jaszczolt (Eds.), The Cambridge book on pragmatics (pp. 549–566). University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Traugott, E. C. (2017). Intersubjectification and clause periphery. English Language and Linguistics, 21(3), 533–556. [Google Scholar]

- Traugott, E. C., & Trousdale, G. (2013). Constructionalization and constructional changes. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Val.Es.Co. Group. (1995). La conversación coloquial. Materiales para su estudio. University of Valencia. [Google Scholar]

- Yus, F. (2016). Humour and relevance. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H., & Lei, L. (2018). Is modern English becoming less inflectionally diversified? Evidence from entropy-based algorithm. Lingua, 216, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H., Liu, X., & Pang, N. (2022). Investigating diachronic change in dependency distance of modern English: A genre-specific perspective. Lingua, 272, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |