Abstract

Coaxial co-rotating (CCR) propeller systems provide structural simplicity, compactness, and high disk loading, making them attractive for an Electric Distributed Propulsion System (EDPS). However, aerodynamic interactions between the upper and lower propellers can lead to efficiency losses, and the effects of key design parameters on overall performance remain insufficiently understood. This study employs Reynolds Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS)-based Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations to examine the effects of axial offset distance, index angle, and differential rotational speeds on the aerodynamic performance of an 18-inch two-blade coaxial co-rotating propeller. Maximum thrust is typically obtained at an index angle of around 60°, while the maximum Figure of Merit (FoM) is achieved at 90°. Increasing the offset distance from 0.05R to 0.20R improves the FoM by approximately 17.3% and reduces its sensitivity to index angle. When different rotating speeds are applied, assigning the higher rpm to the lower propeller increases thrust by 9.4% and the FoM by roughly 9.2%. These results offer practical guidelines for enhancing aerodynamic performance of a CCR propeller in unmanned aerial vehicle and urban air mobility platforms.

1. Introduction

The rapid development of urban air mobility (UAM) has created an urgent demand for eco-friendly, compact and high-efficient propulsion systems. In response, Electric Distributed Propulsion Systems (EDPSs) have emerged as a promising solution, offering advantages such as redundancy, enhanced control authority, and improved aerodynamic integration. In EDPS architectures, propeller-based propulsion is commonly employed due to its high efficiency and scalability [1,2,3]. However, UAM platforms are subject to strict geometric constraints, particularly in rotor diameter, which limits the applicability of large single rotors. To overcome this limitation, coaxial rotor configurations—in which two rotors are aligned along a common axis—have been recognized as an effective alternative for increasing lift within a limited footprint [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12].

Traditionally, Coaxial Counter-Rotating (CCtR) systems, in which the upper and lower rotors rotate in opposite directions, have been widely investigated. Their primary advantage lies in the inherent self-torque cancellation, thereby eliminating the need for a tail rotor or other auxiliary anti-torque mechanisms [5,8,9,10]. Nevertheless, CCtR systems can generate considerable BVI (Blade-Vortex Interaction) noise [11,12], thereby complicating their application in noise-sensitive UAM operations. Early experimental studies on CCtR configurations, including those by Harrington [8], Coleman [9], McCloud [10], outlined the foundational thrust and torque characteristics under varying rotor geometries.

Opazo et al. investigated methods to reduce power consumption in fixed-pitch CCtR systems operating in a hover by combining both an analytical approach based on blade element momentum theory and experimental tests [13]. Xu et al. performed a CFD-based analysis to examine the aerodynamic performance of a CCtR system. Their results showed that the downwash produced by the upper propeller caused a significant reduction in the thrust of the lower propeller, and that the total system torque was decreased by approximately 93.8%, though not entirely eliminated [14]. The hovering performance of a 5-inch-diameter contra-rotating ducted rotor (CRDR) for MAVs was analyzed using CFD [15]. The results showed that the CRDR produced 170% of the thrust of a single rotor, with approximately 30% of the total thrust generated by the duct, thereby achieving the highest power-loading efficiency.

In contrast, Coaxial Co-Rotating (CCR) configurations, where both rotors rotate in the same direction, offer a simpler mechanical layout. The absence of complex counter-rotation mechanism reduces weight and improves system reliability [6,11,12]. Additionally, CCR systems can benefit from reduced tonal noise generation under certain configurations, making them more suitable for UAM environments where acoustic footprint is a critical consideration [11,12]. Furthermore, the increased disk loading achievable with CCR arrangements enables higher thrust generation per unit disk area, which is advantageous in meeting the compact design requirements of UAM vehicles [11,16,17].

Recent work has clarified the primary drivers of thrust and torque in CCR rotor systems. Across hover conditions, performance depends sensitively on the azimuthal index angle between disks, the axial spacing, and blade pitch, and so on. Lee et al. performed RANS-based parametric study and showed that maximum 3% increase in Figure of Merit (FoM) at specific index angle and offset distance [3]. Johnson et al. experimentally analyzed the effects of azimuthal spacing and different collective pitch on the individual and total thrust and power, and found that aerodynamic performance could be improved when the lower propeller led [18]. High-fidelity simulations and rig tests consistently show that certain azimuthal and offset distance combinations increase total thrust and stabilizing rotor loading [19,20].

While previous researches on CCR rotors have advanced our understanding—particularly in acoustics and qualitative flow features—quantitative evidence on thrust, torque, and efficiency remains comparatively limited. Many studies assume equal rotational speeds or vary axial spacing and azimuthal index angle separately, leaving their combined influences only partially characterized, especially at compact separations relevant to UAM. To complement and extend prior work, the present study systematically examines offset distance, index angle, and unequal rotating speeds within a CCR system based on Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) techniques, providing consistent performance trends and practical guidance based on thrust, torque, and FoM. Unlike earlier investigations, this study quantitatively maps the coupled effects of these parameters within a unified CFD framework and identifies design-relevant correlations that provide data-driven insights for optimizing CCR propellers under UAM-scale constraints.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the geometry of the CCR propeller as well as the simulation domain. It also describes the numerical methods employed, computational mesh generation, and mesh sensitivity analysis. Section 3 discusses the aerodynamic performance of the CCR for various index angle, offset distance and rotating speed difference. A comparative analysis of the results is provided. Finally, Section 4 concludes this paper with a summary of our key findings and final remarks.

2. Methodology

2.1. Geometry and Computational Domain

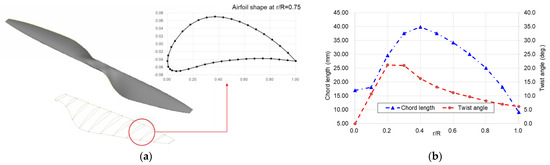

The propeller used in the simulation is a two-blade configuration with a diameter of 18 inches (457.2 mm) and a pitch of 6.5 inches (165.1 mm). The blade has a tapered planform, with a maximum chord length of 39.8 mm located at r/R = 0.4 and a tip chord length of 9.1 mm where R is propeller radius and r denotes the radial position along the blade. The blade twist angle is designed to be 21° in the r/R = 0.2~0.3 region, gradually decreasing to 6.2° at the tip as shown in Figure 1a,b. The airfoil section at r/R = 0.75 has a maximum camber of 5% at 40% of the chord and a thickness-to-chord ratio of 12% as shown in Figure 1a. The solidity of the propeller is 0.07764 where the solidity is defined as Equation (1).

Figure 1.

Geometry of the 18-inch, 6.5-inch pitch two-blade propeller: (a) overall shape, and (b) chord length and twist angle distribution.

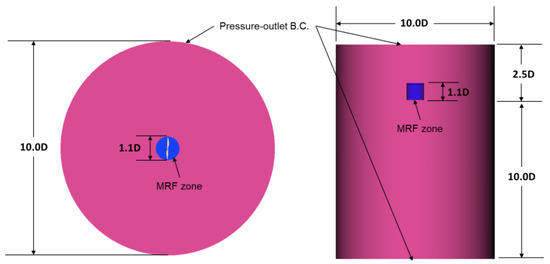

Figure 2 presents the configuration of the simulation domain. The far-field boundaries in the radial, and vertical directions were positioned at distances of 10.0D, and 12.5D, respectively, where D denotes the propeller diameter. A downstream distance of more than 10.0D was ensured to satisfy the pressure outlet boundary condition, allowing for adequate development of the wake region and minimizing reverse flow effects.

Figure 2.

Schematic presentation of the simulation domain.

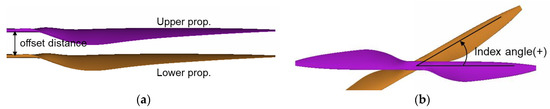

Figure 3 presents the key parameters considered in this study. The offset distance denotes the axial spacing between the upper and lower propellers, and five cases were analyzed with increments of 0.05R from 0.00R to 0.20R. The index angle represents the azimuthal angular displacement between the two propellers, defined as positive when the lower propeller leads. Simulations were conducted for index angles of 0°, ±30°, ±60°, and ±90°.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the CCR propeller configuration: (a) definition of offset distance, and (b) definition of index angle.

2.2. Numerical Method

In this study, CFD simulations were performed to investigate the aerodynamic performance of both single and CCR propellers. For this purpose, commercial CFD software, ANSYS Fluent V2023R1 [21], was used to conduct aerodynamic simulations.

The propellers were operated at rotational speeds ranging from 1000 to 4000 rpm. Within this range, the tip Mach number remained below 0.2 (Vtip ≈ 71.82 m/s at 3000 rpm), indicating incompressible flow conditions. Although minor local compressibility effects may occur near the blade leading edge, their influence on the overall flow field is considered negligible, thereby justifying the assumption of incompressible flow. Accordingly, the incompressible Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equations were solved under steady-state conditions, coupled with the Shear Stress Transport (SST) k–ω turbulence model due to its superior performance under the influence of strong adverse pressure gradients and flow separation phenomena frequently encountered in rotating systems [14,15,16,22].

A second-order upwind scheme combined with the Green-Gauss node-based gradient method was applied for spatial discretization to improve numerical accuracy. The fully coupled algorithm was used to couple velocity and pressure fields.

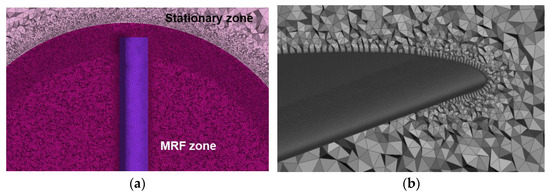

The rotational effects of the propeller were modeled using the Multiple Reference Frame (MRF) technique. In this approach, the rotating domain containing the propeller blades is treated as a steady rotating frame, allowing the centrifugal and Coriolis forces to be incorporated as source terms. This methodology enables efficient and accurate evaluation of steady-state propeller aerodynamics without the computational expense associated with fully transient sliding mesh method [14,15,22]. The size of the MRF domain was set to 1.1D in both the radial and axial directions as shown in Figure 2.

All simulations were performed on a parallel computing system with 64 Intel Xeon cores operating at 2.9 GHz, connected via a Gigabit Ethernet network.

Details regarding the validation of the numerical methodology employed in this study are provided in the Appendix A.

2.3. Mesh Generation and Mesh Sensitivity Analysis

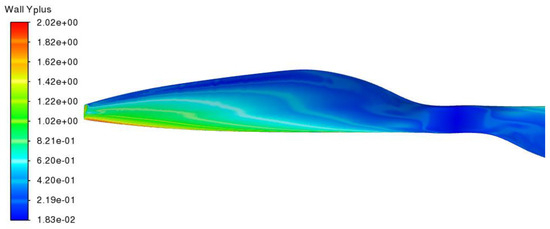

A viscous layer mesh was generated to ensure precise near-wall resolution. The first cell height was determined to achieve at 75% of the propeller radius (r/R = 0.75) under a rotational speed of 3000 rpm, yielding a value of 0.007 mm. A total of 25 viscous layers were generated to ensure a smooth transition from the near-wall boundary layer mesh to the isotropic volume mesh as shown in Figure 4a,b.

Figure 4.

Partial view of surface and volume meshes: (a) surface mesh, and (b) volume mesh.

Figure 5 presents y+ distribution over the propeller surface at the rotating velocity of 3000 rpm. It is observed that the y+ < 1 criterion is maintained across the propeller surface, except in localized regions near the leading edge and blade tip, confirming that the suitability of the mesh for accurate SST k–w turbulence modeling.

Figure 5.

Surface y+ distribution at the rotating velocity of 3000 rpm.

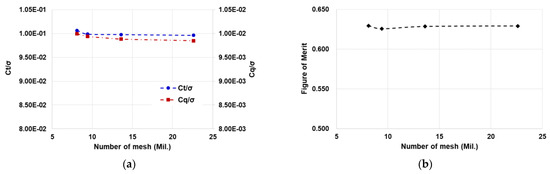

To ensure mesh independence, a sensitivity study was performed using four mesh densities ranging from approximately 7.5 to 22.5 million cells. During the mesh sensitivity study, the surface and boundary layer meshes were kept constant, while the size and distribution of the isotropic cells in the flow domain were varied. Figure 6a presents thrust (), torque coefficient () normalized by solidity () and Figure 6b shows the Figure of Merit (FoM) obtained with different mesh densities.

Figure 6.

Mesh sensitivity analysis: (a) Convergence of , and (b) Convergence of Figure of Merit (FoM) with respect to various mesh resolutions.

Here, , , and FoM are defined as in Equations (2), (3) and (4), respectively, where denotes air density, R is propeller radius, and represents propeller tip velocity.

The ratio represent the thrust and torque coefficients normalized by rotor solidity, providing insight into the aerodynamic efficiency of each propeller configuration irrespective of total blade area.

As the number of mesh increases, the thrust and torque coefficients and the Figure of Merit all converge to constant values, indicating a mesh independence. The increase in computational time with respect to the number of cells was nearly linear; specifically, simulations with approximately 13.6 million cells required 7.5 h of wall clock, while those with 22.5 million cells took approximately 12.0 h. However, the difference in solution accuracy between these two cases were limited to approximately 0.16%, 0.34%, and 0.09% for , , and FoM, respectively. Therefore, considering both computational cost and solution accuracy, the mesh with approximately 13.6 million cells was deemed the most reasonable choice and was subsequently adopted for all further simulations.

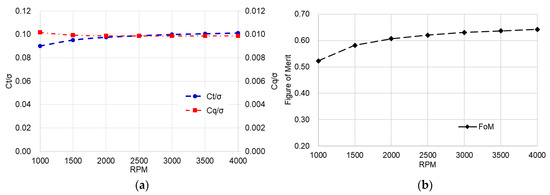

2.4. Single Propeller Performance Analysis

To establish a reference value for evaluating the aerodynamic performance of the CCR propeller system, the aerodynamic characteristics of a single propeller were analyzed. Simulations were performed by varying the rotational speed from 2000 to 4000 rpm in increments of 500 rpm, and the corresponding values of , , and FoM are presented in Figure 7. The value of increased slightly from 0.09 at 1000 rpm to 0.101 at 4000 rpm, indicating a slow upward trend. In contrast, exhibited a gradual decrease from to over the same rpm range. As a result, the FoM increased from 0.523 to 0.641 with increasing rotational speed. Although the FoM is theoretically independent of the rotational speed because and are nondimensionalized with the square of rotating velocity, in practice it can vary with rpm due to Reynolds number effects, viscous losses, tip loss effect, and so on [22].

Figure 7.

Single propeller aerodynamic performance: (a) , and (b) Figure of Merit (FoM) with respect to various rotating velocities.

At 3000 rpm, which corresponds to the normal operating condition of the propeller, the normalized coefficients were approximately and FoM = 0.63.

3. Results and Discussion

The key parameters of a CCR system were defined as the offset distance, index angle, and the rotational speed difference between the upper and lower propellers. To evaluate their effects, the analysis was conducted in two stages: first, the influence of offset distance and index angle was examined; and second, the impact of rotational speed differences between the upper and lower propellers was assessed.

3.1. Effect of Offset Distance and Index Angle

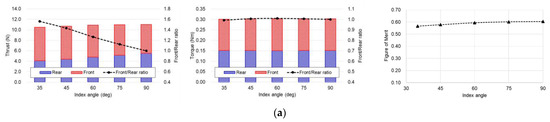

To investigate the aerodynamic characteristics of the CCR system under variation on offset and index angle, simulations were performed for five axial offset distances, ranging from 0.00R to 0.20R in increments of 0.05R along with various index angles of 0°, ±30°, ±60°, and ±90°. In the 0.00R offset case, where both propellers lie on the same plane, the configuration is geometrically equivalent to a four-bladed propeller. In this case, due to blade interference at index angles below 30°, simulations were performed for index angles of 35°, 45°, 60°, 75°, and 90°. In all cases, propellers were operated at an identical rotational speed of 3000 rpm.

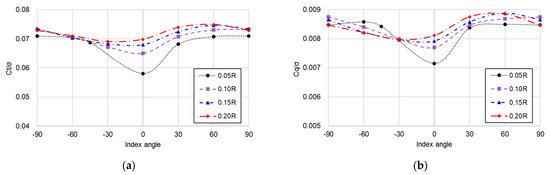

Figure 8 presents the thrust, torque, and FoM under various offset distances and index angles. The FoM of each propeller FoM_up, FoM_low was calculated using Equation (4), while the FoM of the CCR system (FoM_CCR) was evaluated using Equation (5), as proposed by Leishman [23], where the subscripts l and u denote the lower and upper propellers, respectively. The corresponding values of and are presented in Figure 9.

Figure 8.

Thrust, torque, and Figure of Merit with respect to various offset distances and index angles: (a) Offset distance of 0.00R, (b) Offset distance of 0.05R, (c) Offset distance of 0.10R, (d) Offset distance of 0.15R, (e) Offset distance of 0.20R.

Figure 9.

Aerodynamic coefficients normalized by solidity with respect to various offset distances and index angles: (a) , and (b) .

3.1.1. Offset Distance of 0.00R

In case of offset distance of 0.00R case, the front propeller produces greater thrust than the rear propeller as shown in Figure 8a. Notably, at an index angle of 35°, the thrust generated by the front blade is approximately 156% of that produced by the rear blade. This difference gradually decreases as the index angle increases. This trend can be attributed to the interference effects between the wake of the front propeller and the rear propeller as shown in Figure 10. At smaller index angles, the front blade (green colored) experiences less interference from the wake generated by the rear blade (black colored), allowing it to produce greater thrust. However, as the index angle increases, the front blade becomes increasingly affected by the rear blade’s wake, which diminishes its aerodynamic performance and reduces its thrust. As a result, at an index angle of 90°, the thrusts of both propellers become nearly equal, leading to the highest total thrust output. At this condition, the total thrust is approximately 137% of that generated by a single two-bladed propeller, with a corresponding blade loading () of approximately 0.067, representing a 30.2% reduction compared to the single-propeller value of 0.096.

Figure 10.

Tip vortex trajectory by iso-surface of Q-criterion at a value of 5000 for the 0.00R offset case, colored by vorticity magnitude: (a) index angle of 35°; (b) index angle of 90°.

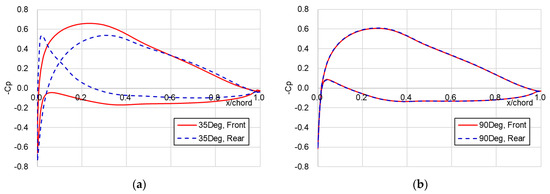

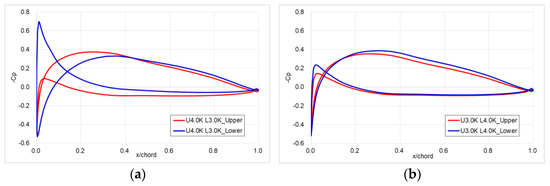

This trend is also evident in the sectional pressure coefficient (Cp) distributions at r/R = 0.9 along the blade radius, as shown in Figure 11. At an index angle of 35°, the pressure distribution on the rear blade produces lower thrust compared with that on the front one. In contrast, at an index angle of 90°, the pressure distribution on the rear blade generates greater thrust compared with that at 35°. Moreover, the pressure distributions of the front and rear blades are nearly identical.

Figure 11.

Comparison of sectional Cp distributions of the front and rear blades at the radial location of 0.9 (r/R = 0.9) at an offset distance of 0.00R: (a) index angle of 35°; (b) index angle of 90°.

The torque values of the front and rear propellers remain nearly identical across all index angles. The propeller efficiency, represented by the FoM, increases with the index angle and reaches its maximum value of 0.605 at 90°, which is slightly lower than that of single-propeller.

3.1.2. Offset Distance of 0.05R ~ 0.20R

For an offset distance of 0.05R and an index angle of 0°, where the upper and lower propellers rotate in the same azimuthal position, a pronounced decrease in thrust is observed. As shown in Figure 8b, the upper propeller produces only approximately 65.1% of the thrust generated by the lower propeller. Furthermore, the total thrust of the CCR system is the lowest among all tested configurations. In contrast, as shown in Figure 8c–e, increasing the offset distance leads to a gradual recovery of the total thrust, with the upper propeller generating approximately 136.2% of the thrust produced by the lower propeller at the offset distance of 0.20R. The thrust difference between the upper and lower propellers with varying offset distances can be explained by the sectional pressure coefficient distributions at r/R = 0.75, as shown in Figure 12. At an offset distance of 0.05R, the local offset-to-chord ratio is 0.42. In this case, the accelerated flow over the upper surface of the lower airfoil reduces the pressure on the lower surface of the upper airfoil, resulting in a decrease in the lift generated by the upper airfoil. Therefore, the FoM of the upper propeller is FoM_UP = 0.355, whereas that of the lower propeller is FoM_LOW = 0.419, indicating that the lower propeller exhibits higher efficiency. In contrast, at an offset distance of 0.20R, where the local offset-to-chord ratio increases to 1.68, the lower airfoil is affected by the wake of the upper airfoil, leading to a decrease in the lift. These characteristics are further corroborated by the results shown in Figure 8e, where the FoM of the upper propeller (FoM_UP = 0.535) is substantially higher than that of the lower propeller (FoM_LOW = 0.367) at an offset distance of 0.20R.

Figure 12.

Pressure coefficient distribution at r/R = 0.75 for an index angle of 0°: (a) offset distance 0.05R, and (b) offset distance 0.20R.

For offset distances between 0.05R and 0.20R, the thrust variation with respect to index angle exhibits a similar trend; the total thrust of the CCR system increases when the lower propeller leads (i.e., at positive index angles), as illustrated in Figure 8b–e. In this case, the thrust ratio between the upper and lower propellers ranges from approximately 65.4% (offset distance 0.05R, index angle 30°) to 121.1% (offset distance 0.20R, index angle 90°), indicating relatively balanced thrust generation between the two. The overall blade loading of CCR system reaches its maximum near an index angle of 60°. In contrast, at negative index angles—where the upper propeller leads—the imbalance in blade loading becomes more pronounced. Notably, at an index angle of –30° and an offset distance of 0.15R, the thrust produced by the upper propeller is predicted to be approximately 171.2% of that generated by the lower propeller.

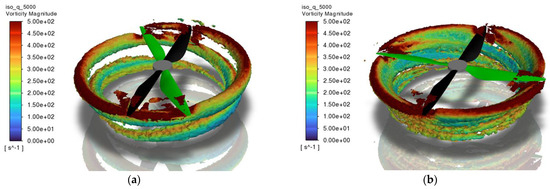

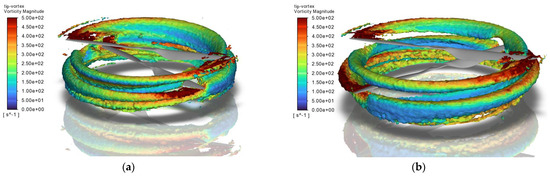

This thrust imbalance can also be observed in Figure 13, which presents iso-surfaces of the Q-criterion at 5000 for an offset distance of 0.20R under index angles of –30° and 60°. As shown in Figure 13a, when the upper propeller leads (index angle –30°), the tip vortices generated at the blade tips of the upper propeller directly interact with the lower propeller, resulting in strong blade–vortex interaction (BVI). Consequently, the FoM of the lower propeller drops to only 0.308 while that of the upper propeller is 0.597. In contrast, when the lower propeller leads (index angle 60°), the tip vortices from the upper propeller interact more weakly with the lower propeller, leading to relatively milder BVI as shown in Figure 13b. As a result, the FoMs of the upper and lower propellers are 0.468 and 0.450, respectively, indicating a more balanced aerodynamic efficiency.

Figure 13.

Tip vortex trajectory by iso-surfaces of Q-criterion at a value of 5000 for an offset distance of 0.20R colored by vorticity magnitude: (a) index angle of –30°; (b) index angle of 60°.

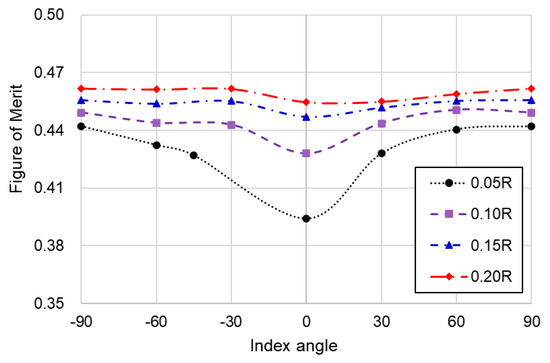

Figure 14 compares the FoM of the CCR system across various offset distances and index angles. While the maximum thrust of the CCR system occurs near an index angle of 60° as shown in Figure 9, the maximum FoM is observed at an index angle of 90°. Overall, the FoM increases with increasing offset distance with positive index angle, showing an approximate 17.3% improvement, from 0.394 (offset distance of 0.05R, index angle of 0°) to 0.462 (offset distance of 0.20R, index angle of 90°). The sensitivity of the FoM to the index angle tends to decrease as the offset distance increases. Specifically, when the offset distance is 0.05R, the FoM varies by approximately 12.2%, increasing from 0.394 at an index angle of 0° to 0.442 at an index angle of 90°. In contrast, with an offset distance of 0.20R, the FoM changes by only about 1.5%, from 0.455 at an index angle of 0° to 0.462 at 90°. Therefore, it is advantageous to maximize the offset distance within the allowable structural rigidity and layout constraints of the CCR system, while the optimal index angle can be selected based on the specific design objectives for thrust and FoM.

Figure 14.

Comparison of Figure of Merit for various offset distances and index angles at a rotating velocity of 3000 rpm.

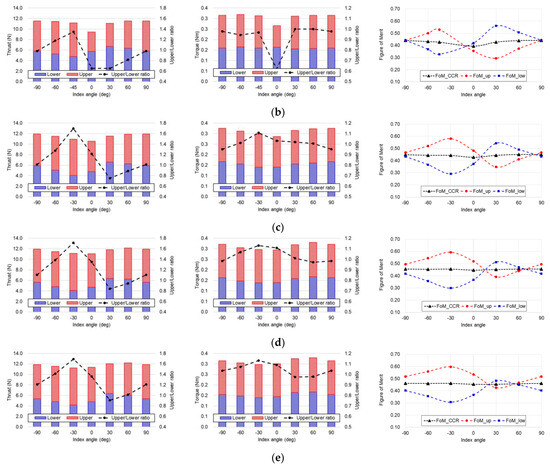

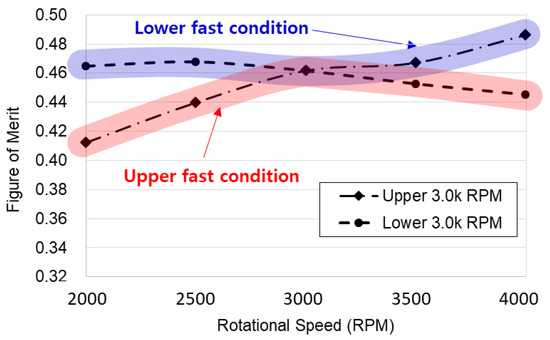

3.2. Effect of Different Rotating Speed

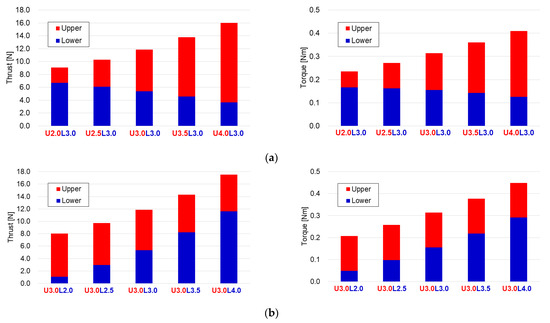

In CCR systems, the rotational speeds of the upper and lower propellers are also a critical design parameter. Accordingly, aerodynamic analyses were conducted to evaluate their influence on overall system performance by varying the rotational speeds. The simulations were conducted at an offset distance of 0.20R, where the highest Figure of Merit (FoM) was consistently achieved across all index angles, showing little sensitivity to their variation. In these cases, the rotational speed of the upper propeller was fixed at 3000 rpm, while the lower propeller speed was varied from 2000 to 4000 rpm in increments of 500 rpm, and vice versa. The results are presented in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Comparison of thrust and torque for various rotating speeds at an offset distance of 0.20R: (a) lower 3000 rpm, (b) upper 3000 rpm.

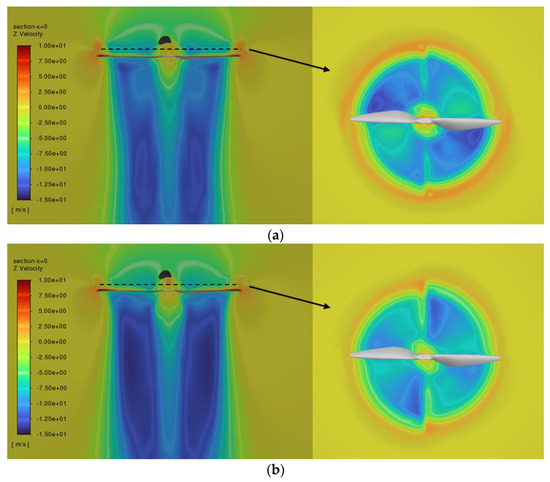

Since the thrust and torque of a propeller are proportional to the square of its rotational speed, propellers operating at higher rpms generate greater thrust and torque. Interestingly, the CCR system produces higher total thrust when the lower propeller operates at a higher rotational speed than the upper propeller. For instance, the U4.0L3.0 configuration (upper propeller at 4000 rpm and lower propeller at 3000 rpm) yields a total thrust of approximately 16.03 N, whereas the U3.0L4.0 (upper propeller at 3000 rpm and lower propeller at 4000 rpm) configuration produces 17.54 N—an increase of about 9.4%—as shown in Figure 15a,b. This can be explained by the fact that when the upper propeller operates at a higher rotational speed, the induced velocity generated by the upper propeller increases, thereby reducing the effective angle of attack of the lower propeller and significantly decreasing its thrust. The increase in induced velocity with rotational speed is also evident in the Z-direction velocity distributions shown in Figure 16a, which represents the Y = 0 plane and Figure 16b, corresponding to Z = 0.10R plane, which represents the center plane of the upper and lower propellers.

Figure 16.

Comparison of Z-direction velocity distributions for different rotating speed combinations: (a) upper propeller at 4000 rpm and lower propeller at 3000 rpm, (b) upper propeller at 3000 rpm and lower propeller at 4000 rpm.

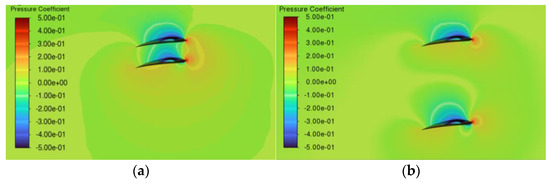

Figure 17 compares the pressure coefficient (Cp) distributions of the upper and lower propellers at the radial location of r/R = 0.75. As shown in Figure 17a, when the upper propeller rotates faster than the lower one, the pressure distribution near the leading edge of the lower propeller exhibits typical characteristics of a negative angle of attack. This is attributed to a strong downwash flow induced by the upper propeller, which reduces the effective angle of attack for the lower propeller. In contrast, as shown in Figure 17b, when the lower propeller rotates faster, this effect is significantly mitigated, and both propellers exhibit relatively similar pressure distributions.

Figure 17.

Comparison of sectional Cp distributions for different rotating speed combinations: (a) upper propeller at 4000 rpm and lower propeller at 3000 rpm, (b) upper propeller at 3000 rpm and lower propeller at 4000 rpm.

Figure 18 presents the FoM as a function of rotational speed. Under the conditions of upper 3000 rpm with lower 4000 rpm, and upper 4000 rpm with lower 3000 rpm, the FoM values are 0.445 and 0.486, respectively, indicating an increase of approximately 9.2% when the lower propeller operates at a higher rotational speed. These results suggest that a higher rotational speed of the lower propeller can provide superior aerodynamic performance in terms of both thrust and FoM.

Figure 18.

Comparison of the Figure of Merit (FoM) for various combinations of upper and lower propeller rotational speeds.

4. Conclusions

This study used CFD simulations to analyze the aerodynamic performance of a coaxial co-rotating propeller system, focusing on the effects of axial offset distance, index angle, and differential rotational speeds.

In the coaxial configuration, offset distance and index angle strongly influenced aerodynamic performance. At zero offset (0.00 R), the front rotor produced more thrust than the rear, especially at small index angles. Thrust balance was achieved at 90°, where total thrust peaked at about 137% of the single-propeller value. Increasing offset from 0.05R to 0.20R improved FoM by approximately 17.3% and reduced sensitivity to index angle. Maximum thrust generally occurred near 60°, while maximum FoM was at 90°, indicating a trade-off between thrust and efficiency. Index angle asymmetry showed that when the lower propeller led (positive angles), thrust was more balanced but when the upper rotor led (negative angles), stronger BVI reduced lower-rotor performance, particularly at –30°, where its FoM was nearly halved. When operating at different rpms, total thrust and FoM were consistently higher when the lower rotor rotates faster than the upper. For example, with one rotor at 3000 rpm and the other at 4000 rpm, placing the higher speed on the lower rotor yielded 9.4% more thrust and 9.2% higher FoM. Overall, aerodynamic performance of the coaxial co-rotating configuration can be optimized by maximizing the offset distance within structural limits and selecting an index angle of 60°~90°. If differential rotating speeds are permissible, assigning a higher rpm to the lower propeller yields superior aerodynamic characteristics. These strategies reduce wake interference, mitigate BVI, and enhance both thrust and efficiency for distributed propulsion applications.

The findings of this study provide useful guidelines for the design of distributed propulsion systems, particularly in Urban Air Mobility (UAM) and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), where compact and efficient propeller arrangements are essential.

Future research will focus on unsteady CFD simulations to capture transient wake interactions and blade–vortex dynamics with higher fidelity. In addition, experimental validation through lab-scale rotor tests will be conducted to verify numerical predictions and provide deeper insights into aerodynamic performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W.J. and S.W.L.; methodology, S.W.L.; software, S.W.J.; validation, S.W.L.; formal analysis, S.W.J.; investigation, S.W.J.; resources, S.W.L.; data curation, S.W.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.W.J.; writing—review and editing, S.W.L.; visualization, S.W.J.; supervision, S.W.L.; project administration, S.W.L.; funding acquisition, S.W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Wonkwang University 2024.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented herein cannot be shared openly but are available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCR | Coaxial Co-Rotating |

| CCtR | Coaxial Counter Rotating |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| Pressure coefficient | |

| Torque coefficient | |

| Thrust coefficient | |

| D | Propeller Diameter |

| FoM | Figure of Merit |

| FoM_CCR | Figure of Merit of coaxial co-rotating propeller |

| FoM_LOW | Figure of Merit of lower propeller |

| FoM_UP | Figure of Merit of upper propeller |

| MRF | Multiple Reference Frame |

| r | Position on the radial direction |

| R | Propeller Radius |

| RANS | Reynolds Averaged Navier–Stokes |

| Propeller tip velocity | |

| y1 | First cell size of the viscous layer mesh |

| y+ | Nondimensional wall distance |

| Propeller solidity | |

| density | |

| ccr | Subscript for coaxial co-rotating |

| l | Subscript for lower |

| u | Subscript for upper |

Appendix A

To validate the accuracy of the numerical methodology employed in this study, additional simulations were conducted using the well-known Caradonna-Tung’s model rotor configuration [24], for which both wind tunnel data and numerical results are available. The rotor consists of two blades with a constant chord length of 0.1905 m and an aspect ratio of 6.0. Since the root cutout was not specified, it was assumed as 1.0R for the present analysis. Both the twist and taper ratios are zero, and the blade cross-section is based on the NACA0012 airfoil. Figure A1 shows the geometry of the Caradonna-Tung’s model rotor and Figure A2 shows the partial view of computational meshes.

Figure A1.

Configuration of Caradonna-Tung’s model rotor.

Figure A2.

Partial view of computational meshes: (a) volume meshes of MRF and stationary zones, and (b) zoom-up view of surface and viscous layer meshes.

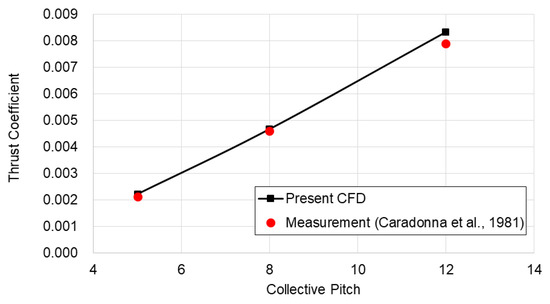

Numerical simulations were performed for three collective pitch angles (5°, 8°, and 12°) at a fixed rotational speed of 1250 rpm, consistent with the available experimental data [24], using the same numerical methodology described in the main text.

Figure A3 compares the thrust coefficients for different collective pitch angles. At a relatively high collective pitch angle of 12°, the predicted thrust coefficient () deviates by approximately 4%, likely due to flow separation effects that are not fully captured in the simulation. In contrast, at pitch angles of 5° and 8°, the discrepancy remains below 1%, confirming the overall reliability of the numerical predictions.

Figure A3.

Comparison of thrust coefficient for various collective pitch angles [24].

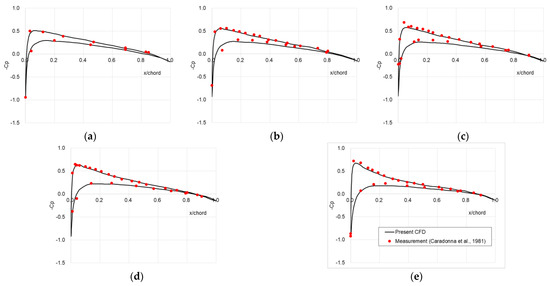

Figure A4 compares the pressure coefficient () distributions at five radial positions of the blade for a collective pitch angle of 5°, showing good correlation between the numerical and experimental results [24].

Figure A4.

Comparison of sectional Cp distributions at a rotating velocity of 1250 rpm and a collective pitch angle of 5°: (a) r/R = 0.50, (b) r/R = 0.68, (c) r/R = 0.80, (d) r/R= 0.89, (e) r/R = 0.96 [24].

References

- Cornelius, J.; Schmitz, S.; Palacios, J.; Juliano, B.; Heisler, R. Rotor Performance Predictions for Urban Air Mobility: Single vs. Coaxial Rigid Rotors. Aerospace 2024, 11, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.C.; Scanavino, M.; D’Ambrosio, D.; Guglieri, G. Experimental and Numerical Analysis of Hovering Multicopter Performance in Low-Reynolds Number Conditions. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 128, 107777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-B.; Park, J.-S. Hover Performance Analyses of Coaxial Co-Rotating Rotors for eVTOL Aircraft. Aerospace 2022, 9, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Lee, H.; Pulliam, T.P. Computational Study of Flow Interactions in Coaxial Rotors. In Proceedings of the AHS Technical Meeting on Aeromechanics Design for Vertical Lift, San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–22 January 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Uehara, D.; Sirohi, J.; Bhagwat, M.J. Hover Performance of Corotating and Counterrotating Coaxial Rotors. J. Am. Helicopter Soc. 2020, 65, 012006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobellis, G.; Singh, R.; Johnson, C.; Sirohi, J.; McDonald, R. Experimental and computational investigation of stacked rotor performance in hover. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 106847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbely, N.L.; Komerath, N.M.; Novak, L.A. A Study of Coaxial Rotor Performance and Flow Field Characteristics. In Proceedings of the AHS Technical Meeting on Aeromechanics Design for Vertical Lift, San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–22 January 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, R.D. Full Scale Tunnel Investigation of the Static-Thrust Performance of a Coaxial Helicopter Rotor; NACA TN 2318; NTRS: Chicago, IL, USA, 1951.

- Coleman, C.P. A Survey of Theoretical and Experimental Coaxial Rotor Aerodynamic Research; NASA Technical Paper 3675; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1997.

- McCloud, J.; Stroub, R.H. An Investigation of Full-Scale Helicopter Rotors at High Advance Ratios and Advancing Tip Mach Numbers; NASA TN D-4632; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1968.

- Whiteside, S.K.S.; Zawodny, N.S.; Fei, X.; Pettingill, N.A.; Patterson, M.D.; Rothhaar, P.M. An Exploration of the Performance and Acoustic Characteristics of UAV-Scale Stacked Rotor Configurations. In Proceedings of the AIAA 2019-1071, AIAA SciTech 2019 Forum, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–11 January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Turhan, B.; Kamliya, J.; Hasan, G.A.; Rezgui, D.; Azarpeyvand, M. Acoustic Performance of Co- and Counter-Rotating Synchronized Propellers. In Proceedings of the AIAA 2024-3236, 30th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference, Rome, Italy, 4–7 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Opazo, T.; Raja, Z.; Raja, A.; Palacios, J.; Schmitz, S.; Langelaan, J. Analytical and Experimental Power Minimization for Fixed-Pitch Coaxial Rotors in Hover. J. Aircr. 2022, 60, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yu, J.; Lu, X.; Long, Z.; Xu, Y.; Sun, H. Aerodynamic Performance and Numerical Analysis of the Coaxial Contra-Rotating Propeller Lift System in eVTOL Vehicles. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Kim, J.K. Numerical Implementation on the Hovering Performance of Contra-Rotating Ducted Rotor for Micro Air Vehicle. Microsys Technol. 2020, 26, 3569–3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhuang, J. Aerodynamic Investigation on a Coaxial-Rotors Unmanned Aerial Vehicle of Bionic Chinese Parasol Seed. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, B.; Zhang, H.; Xiang, C.; Fan, W.; Zhao, Z. Analysis of Aerodynamic Characteristics of Propeller Systems Based on Martian Atmospheric Environment. Drones 2023, 7, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.; Sirohi, J.; Jacobellis, G.; Singh, R. Performance and Acoustics of a Stacked Rotor with Differential Collective Pitch. J. Am. Helicopter Soc. 2024, 69, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Lee, D.; Yang, S.; Kook, H.; Yee, K. Exploration of stacked rotor designs for aerodynamics in hover. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2023, 141, 108557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, J.A.; Tinney, C.E. The unsteady wake produced by a coaxial co-rotating rotor in hover. In Proceedings of the AIAA SciTech 2022 Forum, San Diego, CA, USA, 3–7 January 2022. [Google Scholar]

- ANSYS Inc. ANSYS Fluent User’s Guide; ANSYS Inc.: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Arystanbekov, C.; Zhakatayev, A.; Elhadidi, B. Passive Rotor Noise Reduction Through Axial and Angular Blade Spacing Modulation. Aerospace 2025, 12, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leishman, J.G.; Syal, M. Figure of Merit Definition for Coaxial Rotors. J. Am. Helicopter Soc. 2008, 53, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caradonna, F.X.; Tung, C. Experimental and Analytical Studies of a Model Helicopter Rotor in Hover; NASA Technical Memorandum 81232; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1981.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).