Abstract

The majority of the Earth’s surface is covered by water, with oceans holding approximately 97% of this water and serving as the lifeblood of our planet. These oceans are essential for various purposes, including transportation, sustenance, and communication. However, establishing effective communication networks between the numerous sub-islands present in many parts of the world poses significant challenges. Underwater optical wireless communication, or UWOC, can indeed be an excellent solution to provide seamless connectivity underwater. UWOC holds immense significance due to its ability to transmit data at high rates, low latency, and enhanced security. In this work, we propose polarization division multiplexing-based UWOC system under the impact of salinity with an on–off keying (OOK) modulation format. The proposed system aims to establish high-speed network connectivity between underwater divers/submarines in oceans at different salinity levels. The numerical simulation results demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposed system with a 2 Gbps data rate up to 10.5 m range in freshwater and up to 1.8 m in oceanic waters with salinity up to 35 ppt. Successful transmission of high-speed data is reported in underwater optical wireless communication, especially where salinity impact is higher.

1. Introduction

The transmission of data in the presence of water, particularly saline water, presents a widely recognized challenge that significantly impacts the adoption of wirelessly connected devices in a variety of applications [1]. The effects of saline water not only restrict the deployment of underwater devices but also impose stringent limitations on the positioning of data transmission tools in areas with high water salinity [2,3]. This scenario is particularly relevant for floating structures where successful transmissions necessitate antennas to be elevated at specific heights above saline water to overcome its attenuating effects and ensure reliable communication [4]. However, the challenges become even more pronounced when data transmission needs to occur underwater in environments with high salinity. The combination of water and high salinity levels introduces additional complexities and attenuating effects, significantly impacting the range and quality of wireless communication [5]. The presence of high-salinity water further limits the effective deployment of communication systems and necessitates the development of specialized techniques and equipment to mitigate the detrimental effects and ensure reliable data transmission in these challenging underwater environments [6]. Underwater communication can be enhanced by utilizing optical signals instead of sound-based communication methods [7,8]. Underwater optical wireless communication (UWOC) in water offers several advantages over acoustic communication, including higher data rates, increased bandwidth, and reduced signal attenuation [9].

Figure 1 shows the general scenario of the UWOC link. It shows that the UWOC link serves as a crucial means of connecting divers, submarines, and autonomous underwater vehicles in underwater environments. This advanced communication technology uses modulated light signals to establish real-time, high-speed data exchange between divers and submerged submarines. Consequently, the high transmission rate characteristic of UWOC systems has garnered considerable attention in recent years. The rapid advancements in UWOC systems have resulted in increasing demands for long-range and high-speed underwater links. Achieving these requirements poses a challenge for system designers. Establishing such links is crucial for various applications, including oceanography, environmental monitoring, and underwater surveillance. Furthermore, UWOC has emerged as an attractive alternative to traditional RF and acoustic systems for underwater communication [10,11]. With its advantages of high data rates, low latency, short-range wireless links, and low power consumption, UOWC provides a compelling solution to meet communication needs in underwater environments. UWOC technology finds utility in challenging and remote locations, including deep-sea environments, where it enables communication for remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) [12,13]. This is especially important as these vehicles often face limitations in range and maneuverability.

Figure 1.

Underwater optical wireless communication link.

2. Related Works

In recent years, there has been a growing body of research focused on advancing the field of UWOC, aiming to overcome the challenges of underwater connectivity and harness the potential of optical communication for seamless data transmission below the water’s surface. Authors in 2021 [14] explored three schemes for achieving large-capacity underwater optical transmission systems: OFDM with LD, WDM transmission, and OAM transmission. These technologies offer advantages such as high-speed communication, resistance to interference, and increased transmission capacity. They hold promise for underwater inspection and exploration due to their sufficient bandwidth, reliability, and cost-effectiveness. In 2022 [15], authors proposed a quasi-cyclic low-density parity-checked (QC-LDPC) code with multiple-pulse-position modulation (MPPM) to address turbulence-induced fading in UWOC systems. MPPM offers a balance between power and bandwidth efficiency. Simplified LLR decoding is used, and closed-form expressions for BER are derived. The reported results validate the efficacy of the proposed LDPC code in improving the performance of BER for different MPPM formats over fading channels. Another study in 2022 [16] analyzes the BER performance of UWOC systems with OOK modulation and APD detector with various oceanic turbulence distributions. A mathematical model is developed considering absorption, scattering, and turbulence effects. Closed-form expressions for BER are derived for different turbulence distributions, considering both high- and low-ISI scenarios. Theoretical analysis and simulations confirm the accuracy of the derived expressions, aiding the design and evaluation of UWOC systems. Authors [17] addresses the complexity issue of lookup table (LUT) predistortion in underwater wireless optical communication (UWOC) systems. A multi-modulus weighted strategy is proposed to reduce the size of the LUT while maintaining performance. Experimental results demonstrate significant reduction in LUT size, with the proposed MMW-RLUT accounting for a fraction of the full-size LUT across various QAM modulations without performance degradation. In 2023 [18], authors investigated the self-interference problem in NOMA-based underwater wireless optical communication systems. Their work proposes an ACPS coding scheme to eliminate decoding errors caused by self-interference within NOMA paired groups. Additionally, a GSPA algorithm was designed to optimize power allocation and reduce the bit error rate (BER) in turbulent environments. Simulation results show significant BER reduction in the ACPS-based UWOC-NOMA system compared to conventional systems, considering light-intensity scintillation. Another study in 2023 [19] demonstrates the effectiveness of a modified CNN model in addressing attenuation challenges in underwater optical wireless communication. The proposed CNN decoder significantly improves BER, SNR, and effective channel length compared to a conventional decoder. It achieves a decrease in BER by several orders of magnitude, increased channel length, and decreased SNR. The results make the CNN decoder an ideal substitute for ordinary underwater optical communication decoders.

On the other hand, various multiplexing schemes, such as wavelength division multiplexing (WDM) [20,21], polarization division multiplexing (PDM) [22,23,24], and mode division multiplexing (MDM) [25,26], have been proposed to enhance channel capacity in optical wireless communication. Among these, PDM has emerged as a valuable technique for optical communication systems, offering several advantages [27]. It enhances capacity, robustness, and signal quality by leveraging polarization diversity. PDM improves communication in turbid waters, enhances beam alignment and stability, addresses underwater geographical variations, and offers energy efficiency. In 2022 [28], authors established a high-capacity wireless millimeter-wave (mm-wave) signal delivery system at the W-band using photonics-aided mm-wave generation and polarization division multiplexing (PDM). The authors successfully transmitted PDM-QPSK, PDM-16QAM, and PDM-PS-64QAM mm-wave signals at 10 Gbaud over distances up to 4.6 km. The proposed system achieved a record-breaking data rate of 91.6 Gb/s for single-carrier PDM-PS-64QAM over the wireless distance, surpassing the soft-decision forward error correction (SD-FEC) threshold. This is a significant advancement in wireless mm-wave signal delivery at the W-band. A study in 2023 [29] presented free-space optical communication systems and their challenges. A hybridized model called SS-WDM-PDM is proposed to maximize link capacity and spectral efficiency. The effects of atmospheric attenuations, such as rain and fog, are evaluated. The performance of the SS-WDM-PDM-FSO system is analyzed using parameters like OSNR, BER, and Q factor. Although PDM has been widely used in optical wireless communication, it is still unexploited in UWOC systems. In this work, we propose a PDM-based UWOC system in the turbulent underwater environment. Two channels, each carrying 1 Gbps of NRZ/RZ encoded data, were transmitted over a distance of 10.5 m in the fresh river water environment where salinity is 0.2 ppt. Further, the system was tested in the ocean environment with salinity up to 35 ppt. The numerical simulation results verify that the scheme can effectively suppress the high attenuation caused by the salinity of the oceans. The main contributions of our work lie in the utilization of two polarization states for underwater optical wireless communication (UWOC) systems. By employing two orthogonal polarization states, our proposed PDM-UWOC system offers three significant advantages:

- (a)

- Increased Transmission Capacity: The use of PDM allows for the simultaneous transmission of multiple data streams over the same optical channel. As a result, the data rate of our proposed PDM-UWOC system is significantly higher than existing UWOC systems that rely on single-polarization transmission. This enhancement in transmission capacity opens up new possibilities for high-data-rate underwater communication applications.

- (b)

- Improved Spectral Efficiency: With the simultaneous transmission of data in two polarization states, our PDM-UWOC system achieves improved spectral efficiency. By efficiently utilizing the available optical spectrum, our system can transmit more data within the same bandwidth, making it a promising solution for increasing the efficiency of underwater communication links.

- (c)

- Mitigation of Polarization-Induced Fading: The implementation of PDM helps mitigate the adverse effects of polarization-induced fading, which is a common issue in underwater communication. By transmitting data in two orthogonal polarization states, we enhance the robustness and reliability of the communication link, leading to improved overall system performance.

The rest of the paper is divides as follows: Section 3 defines the UWOC Channel modeling, and Section 4 defines the system architecture of the proposed PDM-based UWOC link, followed by results and discussion in Section 5. Section 6 describes the contribution of our work to sensor and actuator networks. Finally, the conclusion is presented in Section 7.

3. UWOC Channel Modeling

UWOC offers numerous advantages such as high data rates, larger bandwidth, lower time delay, low latency, and reduced power consumption when compared to acoustic and RF technologies. However, the establishment of a wireless optical link underwater poses significant challenges. The main challenge arises from the fact that the optical signal is heavily impacted by the optical characteristics of the medium and disturbances caused by turbulence [30]. The optical properties of water that significantly impact the propagation of optical signals underwater are absorption and scattering. These properties are associated with absorption and scattering coefficients, represented as a(λ) and b(λ), respectively, and depend on the wavelength of the signal. The combined effect of absorption and scattering coefficients is referred to as the beam extinction coefficient, denoted as c(λ). This coefficient, c(λ), quantifies the overall attenuation experienced by the optical signal in water, encompassing both absorption and scattering phenomena as in Equation (1) [31]:

Absorption coefficient a(λ) measures light absorption in water, influenced by water properties and signal wavelength. Scattering coefficient b(λ) indicates light scattering by particles in water, occurring when the particle size is comparable to the light’s wavelength. The beam extinction coefficient, represented by c(λ), accounts for both the absorption and scattering coefficients, providing a comprehensive measure of the overall attenuation experienced by optical signals in underwater conditions. The overall absorption a(λ) in underwater optical communication is influenced by several factors given as in Equation (2) [32]:

where aw is the absorption due to pure water, aphy is the absorption due to phytoplankton, ag is the absorption due to dissolved organic matter, and an is the absorption due to non-algal suspended particles. Each of these components contributes to the overall attenuation of optical signals in underwater environments. Cw, Cphy, Cg, and Cn are the absorption coefficients of pure water, phytoplankton, dissolved organic matter, and non-algal suspended particles, respectively. Scattering primarily relies on the dimensions of the particles suspended within a water channel. When the suspended particles are smaller than the wavelength of the optical wave employed for propagation, Rayleigh scattering is observed. Conversely, Mie scattering occurs when the particle size surpasses the wavelength of the optical wave. Various regions of ocean water encompass suspended particles of distinct sizes. In the case of pure ocean water, the predominant presence consists of salts and ions, which possess a size on the same scale as the wavelength of the optical wave used. Consequently, Rayleigh scattering aptly describes the scattering phenomenon in this scenario [33]. The mathematical equation for the Rayleigh scattering coefficient for pure ocean water is given by [31]:

The equation provided calculates the Rayleigh scattering coefficient based on the wavelength in nm. While scattering has a significant impact on shorter wavelengths, the overall attenuation in pure ocean water primarily occurs through absorption. When ocean water is located near land, it contains particulate and organic matter, leading to scattering as the primary cause of attenuation for optical waves. The scattering phenomenon in ocean water is significantly influenced by the presence of both organic and inorganic particles. Additionally, salinity, pressure, and temperature are factors that affect the refractive index of sea water, creating an optical boundary that alters the original propagation path of the optical wave. In this scenario, Mie scattering accurately describes the scattering behavior. The scattering coefficients for small and large particles in sea water can be expressed as follows [31]:

In the given context, bl represents the scattering coefficient for large particles, while bs represents the scattering coefficient for small particles.

Apart from absorption and scattering, turbulence plays a crucial role in influencing underwater optical wireless communication (UWOC). The underwater environment experiences variations in temperature, density, and salinity, which lead to fluctuations in the refractive index of the underwater channel. Consequently, these fluctuations cause variations in the intensity of the received signal, commonly known as turbulence [34,35]. Furthermore, air bubbles present in the water channel contribute to random fluctuations in the refractive index. Turbulence has a detrimental effect on the performance of UWOC, and therefore its impact needs to be thoroughly analyzed. The salinity of water, which is determined by the concentration of dissolved salts, is typically expressed in parts per thousand (ppt) or kilograms of salt in 1000 kg of water. Another commonly used unit for salinity is the practical salinity unit (psu), which is almost equivalent to ppt [36]. In ocean water, the average salinity ranges from 31 to 37 ppt. However, polar regions tend to have salinity levels below 30 ppt, while Antarctic regions typically have salinity levels around 34 ppt. Salinity can be measured using two main methods. The first method involves measuring electrical conductivity (EC), expressed in micro-siemens per centimeter. The second method measures the quantity of salt particles present in the solution, known as total dissolved salts. Sea water typically contains dissolved salts such as chlorides, sulphates, sodium carbonate, potassium carbonate, calcium carbonate, and magnesium carbonate. The average salinity of ocean water is approximately 35 ppt [37], indicating that 35 g of material is dissolved in every 1000 g of ocean water. In CGS units, where the density of water is 1, this can be equivalently expressed as 35 g per liter (gm/L).

4. Proposed PDM-Based UWOC Link Description

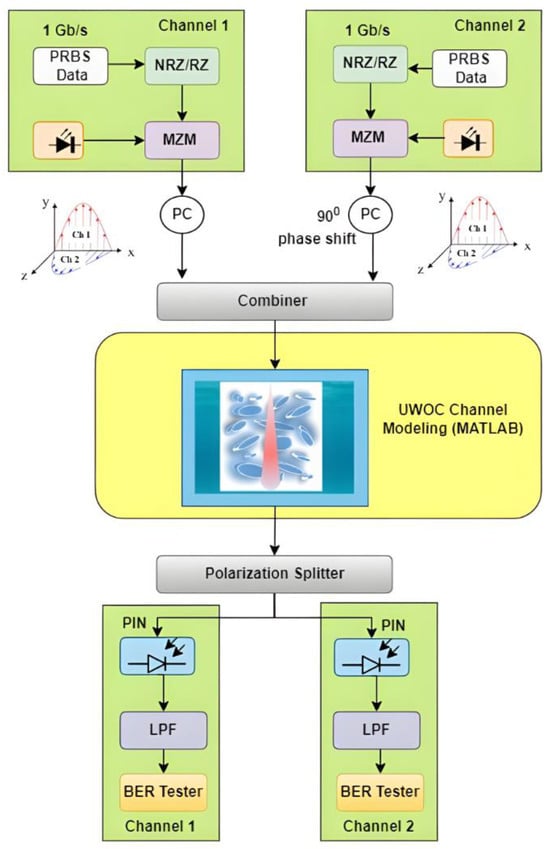

Figure 2 illustrates the proposed PDM-based UWOC link, which carries data from two independent channels, designed by using OptiSystemTM and MATLABTM software. The UWOC channel modeling was performed in MATLABTM, while the transmitters and receivers were designed in OptiSystemTM.

Figure 2.

Proposed 2 × 1 Gbps PDM-based high-speed UWOC model.

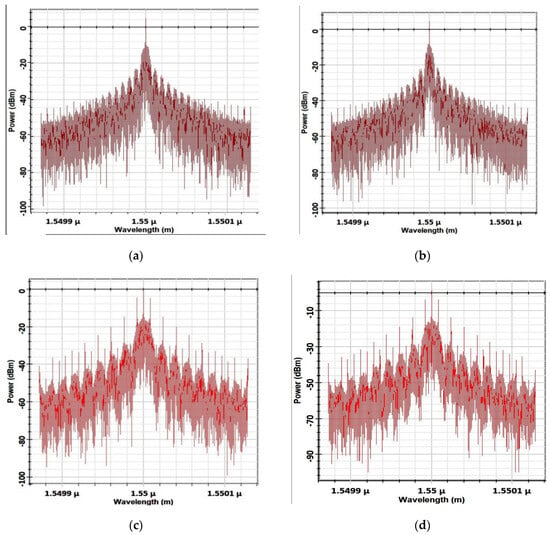

Figure 2 depicts two channels in the UWOC link, each transmitting high-speed 1 Gbps NRZ/RZ encoded data. In each channel, a continuous wave laser operating at a wavelength of 1550 nm and a power of 100 mW is used to modulate the 1 Gbps NRZ/RZ encoded data using a Mach–Zehnder modulator (MZM). The output of each channel is connected to a polarization controller, which applies a phase shift of 0° and 90° to each respective output. Figure 3 displays the optical spectrum for each polarization state, illustrating the RZ and NRZ encoding schemes.

Figure 3.

Measured optical power spectra: (a) X polarization with NRZ encoding; (b) Y polarization with NRZ encoding; (c) X Polarization with RZ encoding; (d) Y polarization with RZ encoding.

The outputs of the polarization controllers are combined and transmitted through the UWOC link. To model the UWOC link, Beer–Lambert’s law is used. Beer–Lambert’s law is commonly applicable to optical signals in any medium [38]. Two assumptions were made to validate the use of Beer–Lambert’s law in this analysis. Firstly, it was assumed that the transmitter and receiver are perfectly aligned. Furthermore, although scattered photons are theoretically considered lost, in real-time scenarios, some of these scattered photons can still be detected by the receiver due to multiple scattering. Since the numerical simulations were conducted within a limited range of communication, the alignment between the transmitter and receiver was considered to be perfect. With an increase in the link length, a noticeable decrease in the received power was observed, indicating the occurrence of either photon scattering or absorption phenomena. Based on the numerical simulations, a simplified mathematical expression is proposed by fitting the data. This mathematical expression serves as an approximation for the received power pr in the UWOC channel and is given as follows:

where c1 and c2 are constants and d is the range of the UWOC channel.

In the receiver stage of our proposed PDM-UWOC system, a polarization splitter is used to separate the received optical signal into its respective polarization states. Since our system employs polarization division multiplexing (PDM), where data are transmitted simultaneously in two orthogonal polarization states, this component plays a crucial role. By using a polarization splitter, we can effectively isolate the individual polarization components and independently process them for further signal analysis and decoding. For the optical detection of the received signals, an Avalanche Photo-Detector (APD) is employed in the receiver section. The selection of an APD is motivated by its ability to provide high sensitivity and gain. This is particularly advantageous in underwater optical communication, where received optical power levels can be relatively low due to attenuation and scattering in the underwater medium. The APD’s responsivity of 1 A/W indicates that for every watt of incident optical power, it generates an electrical current of 1 ampere, which enables efficient signal detection. To enhance the signal-to-noise ratio and suppress high-frequency noise components, a low-pass filter with a cut-off frequency of 750 MHz is employed. Underwater communication channels are susceptible to various sources of noise, including background noise and ambient light fluctuations. The low-pass filter effectively attenuates frequencies above 750 MHz, ensuring that the receiver primarily processes the desired low-frequency signal components and mitigates the impact of noise on the system’s performance. The BER tester is a critical instrument used to measure the bit error rate for each channel. In our proposed PDM-UWOC system, since we are utilizing two polarization states, we measure the BER separately for each polarization channel. The BER tester compares the received data to the transmitted data and determines the ratio of erroneous bits to the total number of bits transmitted. This measurement allows us to quantitatively evaluate the system’s performance and assess its error-correcting capabilities. The additional simulation parameters are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Numerical simulation parameters.

5. Results and Discussion

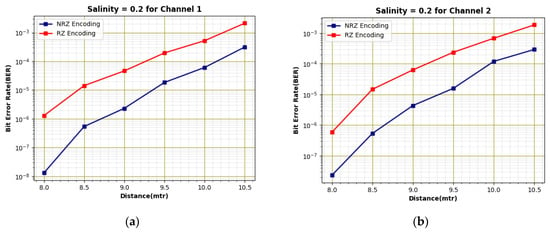

This section presents and discusses the results obtained from the numerical simulation of polarization division multiplexing (PDM)-enabled underwater optical wireless communication (UWOC) using the on–off keying (OOK) modulation scheme. First, the proposed system is tested under freshwater conditions, assuming a salinity level of 0.2 ppt. Figure 4 shows the measurement of bit error rate (BER) at different distance of UWOC link for both channels by evaluating the performance of NRZ and RZ encoding schemes. It clearly demonstrates that the NRZ modulation scheme outperforms the RZ scheme in terms of BER. As shown in Figure 3a, at a distance of 8 m, the NRZ scheme achieves an impressively low BER of approximately . However, as the distance extends to 10.5 m, the BER rises to approximately . On the other hand, the RZ curve follows a similar trend but with generally higher BER values compared to NRZ. At a distance of 8 m, the RZ scheme demonstrates a BER of around which increases to approximately at a distance of 10.5 m. Similarly, for channel 2, for NRZ and RZ encoding scheme, the BER is also reported as and , respectively, at the distance of 10.5 m.

Figure 4.

Measurement of BER under freshwater conditions: (a) channel 1; (b) channel 2.

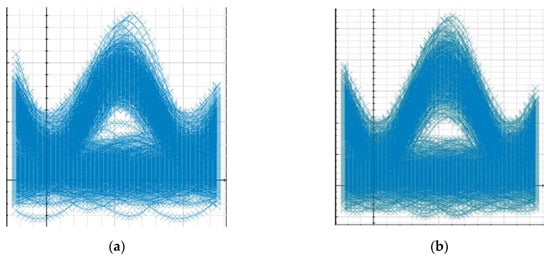

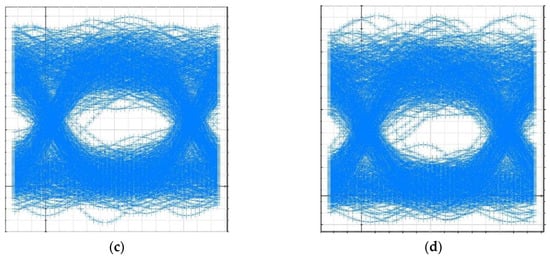

This indicates that the NRZ modulation scheme provides better communication performance, with lower errors, over longer distances. Figure 5 demonstrates that for both the RZ and NRZ encoding schemes, the eye diagrams show clear openings. This further indicates successful transmission of high-speed data at the distance of 9.5 m underwater.

Figure 5.

Measured eye diagrams at 9.5 m distance: (a) channel 1 with RZ encoding; (b) channel 2 with RZ encoding; (c) channel 1 with NRZ encoding; (d) channel 2 with NRZ encoding.

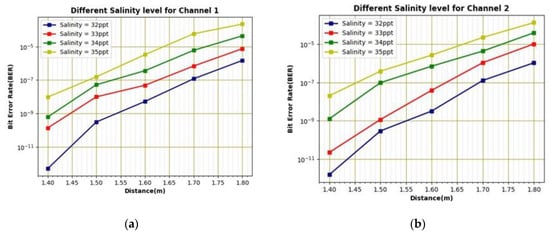

Moreover, as discussed earlier, attenuation increases with the salinity of the water in different oceans. We have tested the proposed system for salinity levels ranging from 32 ppt to 35 ppt.

Figure 6 presents the results of testing the proposed system using NRZ encoding at different salinity levels in UWOC links. As shown in Figure 6a, at a salinity level of 32 ppt, the BER for channel 1 remains relatively low across the distances tested. At a distance of 1.4 m, the BER is approximately , and it gradually increases to around at a distance of 1.8 m, whereas at a salinity level of 33 ppt the BER values are slightly higher compared to the previous salinity level. At a distance of 1.4 m, the BER is approximately increasing to around at a distance of 1.8 m. When the salinity level is 34 ppt, we observe a further increase in the BER values. The BER starts at approximately at a distance of 1.4 m and rises to about at a distance of 1.8 m. Lastly, the salinity level of 35 ppt exhibits the highest BER values among all the curves. Starting at approximately at a distance of 1.4 m, the BER increases to around at a distance of 1.8 m. Similarly for channel 2, data are successfully transmitted up to a salinity level of 35 ppt with the acceptable BER of at the distance of 1.80 m.

Figure 6.

Measurement of BER at different salinity levels: (a) channel 1; (b) channel 2.

Thus, Figure 6 shows that as the salinity level of the water increases, the BER values also increase, indicating a degradation in the communication performance of the UWOC system. Higher salinity levels introduce additional signal impairments, leading to a higher likelihood of errors in the transmitted data.

Table 2 presents the comparison of our proposed UWOC with previous works.

Table 2.

Comparison with the previous works.

6. Contribution to Sensor and Actuator Networks

The field of sensor and actuator networks plays a pivotal role in modern technological advancements, enabling real-time data collection and remote control across various domains. In this section, we explore how our research on polarization division multiplexing-based underwater optical wireless communication (UWOC) with on–off keying (OOK) modulation format can contribute to the enhancement of sensor and actuator networks.

- (I)

- Integration with Sensor and Actuator NetworksOur proposed UWOC system offers several features that align with the requirements of sensor and actuator networks. One of the primary strengths of our system is its ability to transmit data at high rates with low latency, making it particularly suitable for real-time data collection and control applications. By seamlessly integrating our UWOC system into sensor networks, we can achieve faster and more efficient data transmission, enabling enhanced decision-making processes and real-time monitoring of remote environments.

- (II)

- Use Cases and Applications

- (a)

- Remote Environmental MonitoringIn sensor and actuator networks for environmental monitoring, the timely collection of data from remote sensors is critical. Our UWOC system can enable high-speed data transmission from underwater sensors to central monitoring stations, facilitating the rapid assessment of environmental conditions. This can have applications in monitoring oceanographic data, assessing water quality, and tracking marine life.

- (b)

- Underwater Robotics and ActuationIn underwater robotics and actuation systems, real-time communication is vital for remote vehicle control and data retrieval. By employing our UWOC technology, underwater robots can benefit from improved data rates and reduced communication delays, leading to more precise control and efficient exploration of aquatic environments.

- (III)

- Potential ImpactThe integration of our proposed UWOC system into sensor and actuator networks can yield significant benefits. It can enhance the capabilities of remote monitoring system:

- (a)

- Expand the scope of underwater data collection and analysis.

- (b)

- Improve the reliability of underwater communication networks.

- (c)

- Enhance real-time control and actuation in aquatic environments.

Thus, our research on polarization division multiplexing-based UWOC with OOK modulation format holds promise for advancing sensor and actuator networks, particularly in underwater and aquatic environments. The high-speed data transmission, low latency, and enhanced security aspects of our system can contribute significantly to the efficiency and effectiveness of sensor and actuator-based applications in challenging underwater settings.

7. Conclusions

In this work, the proposed PDM-UWOC system utilizing the on–off keying (OOK) modulation scheme demonstrates promising results for achieving high-speed network connectivity underwater. The modeling of the UWOC link was carried out in MATLABTM, and the PDM-based transmitter and receiver were designed in OptiSystemTM software. The numerical simulation results indicate that the NRZ modulation scheme outperforms the RZ scheme in terms of BER at varying distances. The NRZ scheme exhibits lower BER values, providing better communication performance over longer distances compared to the RZ scheme. Additionally, the eye diagrams of both encoding schemes show clear openings, confirming the successful transmission of high-speed data at 9.5 m underwater. Furthermore, the investigations conducted at different salinity levels highlight the impact of water salinity on communication performance. As salinity increases, the BER values also increase, indicating a degradation in the system’s performance. Higher salinity levels introduce additional signal impairments, leading to a higher likelihood of errors in transmitted data. These findings emphasize the importance of considering salinity levels in designing and optimizing UWOC systems. Overall, the proposed PDM-enabled UWOC system with NRZ encoding demonstrates its potential for providing seamless and reliable communication in underwater environments, considering both freshwater and varying salinity conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C.; methodology, S.C. and A.S.; software, S.C. and A.S.; validation, S.K. and S.S.; formal analysis, S.C. and L.W.; investigation, A.S. and R.U.; resources, A.P.; data curation, R.U. and A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C.; writing—review and editing, L.W.; visualization, S.K.; supervision, L.W.; project administration, S.C. and L.W.; funding acquisition, S.C. and L.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This research project is supported by the Second Century Fund (C2F), Chulalongkorn University, Thailand.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bello, O.; Zeadally, S. Internet of underwater things communication: Architecture, technologies, research challenges and future opportunities. Ad Hoc Netw. 2022, 135, 102933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menaka, D.; Gauni, S.; Manimegalai, C.T.; Kalimuthu, K. Challenges and vision of wireless optical and acoustic communication in underwater environment. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2022, 35, e5227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsan, S.A.H.; Mazinani, A.; Othman, N.Q.H.; Amjad, H. Towards the internet of underwater things: A comprehensive survey. Earth Sci. Inform. 2022, 15, 735–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzebon, A.; Cappelli, I.; Campagnaro, F.; Francescon, R.; Zorzi, M. LoRaWAN Transmissions in Salt Water for Superficial Marine Sensor Networking: Laboratory and Field Tests. Sensors 2023, 23, 4726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojanovic, M.; Preisig, J. Underwater acoustic communication channels: Propagation models and statistical characterization. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2009, 47, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuna, G.; Gungor, V.C. A survey on deployment techniques, localization algorithms, and research challenges for underwater acoustic sensor networks. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2017, 30, e3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, M.C. An overview of the internet of underwater things. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2012, 35, 1879–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codd-Downey, R.; Jenkin, M. LightByte: Communicating Wirelessly with an Underwater Robot using Light. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Informatics in Control, Automation and Robotics—ICINCO (2), Porto, Portugal, 29–31 July 2018; pp. 309–316. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, C.; Alkhazragi, O.; Sun, X.; Guo, Y.; Ng, T.K.; Ooi, B.S. Laser-based visible light communications and underwater wireless optical communications: A device perspective. In Novel in-Plane Semiconductor Lasers XVIII; SPIE: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2019; Volume 10939, pp. 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Qasem, Z.A.; Ali, A.; Deng, B.; Li, Q.; Fu, H. Unipolar X-Transform OFDM with Index Modulation for Underwater Optical Wireless Communications. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2023, 35, 581–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasem, Z.A.; Ali, A.; Deng, B.; Li, Q.; Fu, H. Index modulation-based efficient technique for underwater wireless optical communications. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 167, 109683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.F.; Jayakody, D.N.K.; Chursin, Y.A.; Affes, S.; Dmitry, S. Recent advances and future directions on underwater wireless communications. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2020, 27, 1379–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.F.; Jayakody, D.N.K.; Li, Y. Recent trends in underwater visible light communication (UVLC) systems. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 22169–22225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. An investigation on large capacity transmission technologies for UWOC systems. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1920, 012018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; He, N.; Liao, X.; Popoola, W.; Rajbhandari, S. The BER Performance of the LDPC-Coded MPPM over Turbulence UWOC Channels. Photonics 2022, 9, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Li, Y.; Huang, P.; Ju, M.; Tan, G. BER Performance of UWOC with APD Receiver in Wide Range Oceanic Turbulence. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 25203–25218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Niu, W.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhang, J.; He, Z.; Chi, N. Low-Complexity Multi-Symbol Multi-Modulus Weighted Lookup Table Predistortion in UWOC System. J. Light. Technol. 2022, 40, 4224–4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Yin, H.; Jing, L.; Ji, X.; Wang, J. Solution for Self-Interference of NOMA-Based Wireless Optical Communication System in Underwater Turbulence Environment. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 30223–30236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, O.N.M.; Adnan, S.A.; Mutlag, A.H. Underwater optical wireless communication system performance improvement using convolutional neural networks. AIP Adv. 2023, 13, 045302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Chaudhary, S.; Thakur, D.; Dhasratan, V. A cost-effective high-speed radio over fibre system for millimeter wave applications. J. Opt. Commun. 2020, 41, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kaur, S.; Chaudhary, S. Performance analysis of 320 Gbps DWDM—FSO system under the effect of different atmospheric conditions. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2021, 53, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, B.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Qasem, Z.A.H.; Li, Q.; Tang, X.; Chen, C.; Fu, H.Y. Polarization Multiplexing Based UOWC Systems Under Bubble Turbulence. J. Light. Technol. 2023, 41, 5588–5598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Choudhary, S.; Tang, X.; Wei, X. Empirical evaluation of high-speed cost-effective Ro-FSO system by incorporating OCDMA-PDM scheme under the presence of fog. J. Opt. Commun. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Chaudhary, N.; Sharma, S.; Choudhary, B. High speed inter-satellite communication system by incorporating hybrid polarization-wavelength division multiplexing scheme. J. Opt. Commun. 2017, 39, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Malhotra, J.; Chaudhary, S.; Thappa, V. Analysis of 2 × 10 Gbps MDM enabled inter satellite optical wireless communication under the impact of pointing errors. Optik 2021, 227, 165250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, K.K.; Shukla, N.K.; Chaudhary, S. A high speed 100 Gbps MDM-SAC-OCDMA multimode transmission system for short haul communication. Optik 2020, 202, 163665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choyon, A.S.J.; Chowdhury, R. Nonlinearity compensation and link margin analysis of 112-Gbps circular-polarization division multiplexed fiber optic communication system using a digital coherent receiver over 800-km SSMF link. J. Opt. 2021, 50, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yu, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhu, B.; Ding, J.; Wang, K.; Liu, C.; Wang, C.; Kong, M.; et al. Delivery of Polarization-Division-Multiplexing Wireless Millimeter-Wave Signal Over 4.6-km at W-Band. J. Light. Technol. 2022, 40, 6339–6346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasani, E.; Shah, V. An Effective Design of Hybrid Spectrum Slicing WDM–PDM in FSO Communication System Under Different Weather Conditions. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2023, 130, 777–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosu, R.; Prince, S. Perturbation methods to track wireless optical wave propagation in a random medium. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2016, 33, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, H.; Kaddoum, G. Underwater optical wireless communication. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 1518–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerlov, N.G. Marine Optics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Hulburt, E. Optics of distilled and natural water. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1945, 35, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotkova, O.; Farwell, N.; Shchepakina, E. Light scintillation in oceanic turbulence. Waves Random Complex Media 2012, 22, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, M.V.; Nabavi, P.; Salehi, J.A. MIMO Underwater Visible Light Communications: Comprehensive Channel Study, Performance Analysis, and Multiple-Symbol Detection. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2018, 67, 8223–8237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski, B. Characterization of a very shallow water acoustic communication channel. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2009, Biloxi, MS, USA, 26–29 October 2009; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, C.E. Water Quality: An Introduction; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Z.; Fu, S.; Zhang, H.; Dong, Y.; Cheng, J. A Survey of Underwater Optical Wireless Communications. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2017, 19, 204–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravind, J.V.; Prince, S. Localizing an underwater sensor node using sonar and establishing underwater wireless optical communication for data transfer applications. Mar. Georesources Geotechnol. 2023, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.A.A.; Shaker, F.K. Performance of an underwater non-line-of-sight (NLOS) wireless optical communications system utilizing LED. J. Opt. 2023, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gao, Y.; Tong, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Xu, J. Omnidirectional optical communication system designed for underwater swarm robotics. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 18630–18644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Y.; Zhu, M.; Cui, K.; Li, L.; Wang, S. Simulation analysis of underwater wireless optical communication based on Monte Carlo method and experimental research in complex hydrological environment. AIP Adv. 2023, 13, 055226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).